ABSTRACT

What happens to newly built resilience capabilities when the pandemic is over? Using the concept of exaptation, we investigate how supply chain organizations have repurposed supply chain resilience capabilities post-pandemic. In particular, we examine the degree of ambidexterity capabilities to identify the exaptation potential from the newly acquired supply chain resilience capabilities during a disruptive event. In this paper, we (1) adopt a framework that depicts four types of different exaptation potential for supply resilience based on the management constructs of exploitation and exploration capabilities and (2) use the results from a related survey among 447 supply chain managers in Australia to subsequently analyse the exaptation potentials post COVID-19. The integration of the exaptation potential into supply chain literature opens a new chapter on how resilience capabilities are utilized, and we found that the majority of supply chains are able to simultaneously pursue and develop exploitative and exploratory capabilities.

1. Introduction

Supply chain resilience research has increased significantly since the beginning of COVID-19 and scholars have investigated the cause and the implications of supply chain resilience from various perspectives (e.g. Beer et al., Citation2022; Carissimi et al., Citation2023; Ivanov & Das, Citation2020; Ivanov & Dolgui, Citation2020; C.-L. Liu & Lee, Citation2018; Pettit et al., Citation2019; Sabahi & Parast, Citation2020). In particular, scholars have examined how organizations can build relevant dynamic capabilities (Teece, Citation2007; Teece et al., Citation1997) to respond to the supply chain disruptions caused by an external shock of high impact and low probability (see e.g. Eltantawy, Citation2016; Gu & Huo, Citation2017; Mandal et al., Citation2017; Sabahi & Parast, Citation2020; Yu et al., Citation2019). However, the majority of the studies focus on how these resilience capabilities can be built during the pandemic to ‘return to its original state’ (Coutu, Citation2002), ‘maintain continuity of operations’ (Gölgeci & Ponomarov, Citation2015) or ‘transform to another configuration’ (Christopher & Peck, Citation2004), thereby neglecting how organizations use or apply these dynamic capabilities in a post COVID-19 pandemic world. In other words, literature so far has paid little attention to how organizations may apply or repurpose newly acquired capabilities when supply chain operations return a post-disruptive environment.

Scholars link the repurposing of acquired capabilities during a crisis or disruption to the concept of exaptation (W. Liu et al., Citation2022; Rake & Hanisch, Citation2023). Exaptation was originally used by in the field of biology to illustrate features that originally have been developed for one function, but were later used for an alternative function (Gould & Vrba, Citation1982). As Andriani et al. (Citation2017) argues, exaptation is a source of innovation, as it ‘constitutes a mechanism through which unexpected solutions “push” the emergence of novel problems’ (p. 320). In other words, one crucial component of exaptation is to ‘pivot’ from one function to another (Dooley & Som, Citation2018), i.e. without having to start a innovation project from the beginning as the original work has been completed and needs ‘only’ redirection to new domains (Savino et al., Citation2017). A classic example of exaptation is the repurposing of the radar component magnetron that eventually led to the basis of the microwave oven (Andriani & Carignani, Citation2014). A striking example of exaptation in supply chains resilience management during COVID-19 was the ability of the company Dyson, a manufacturer of hand-dryers, vacuum cleaners and air-purifiers, to repurpose their supply chains, manufacturing and product designs to rapidly switch and build urgently needed ventilators for hospital patients (W. Liu et al., Citation2021).

Studies about the exaptation and its potential are rather limited, in particular regarding supply chain resilience. As a response, this article attempts to shed light on how the newly acquired resilience capabilities are utilized or repurposed after a disruptive event. We argue that the exaptation potential of supply chain resilience capabilities depends on both exploitative capabilities, i.e. to what extent companies could exploit their capabilities during the COVID-19 pandemic, as well as exploratory capabilities, i.e. to what extent companies have explored, learned and utilized new skills to transform and repurpose their resources after the COVID-19 pandemic. In other words, the exaptation potential is strongly linked to the relative degree of ambidextrous capabilities, represented by the interplay and the trade-offs between exploitative and exploratory capabilities. Exploitation capabilities rely on existing knowledge and on an existing customer base and represents a firm’s ability to ‘improve quality and lower cost continuously, improve the reliability of products and services, increase the levels of automation, constantly survey existing customers’ satisfaction [and] fine-tune what is offered’ (Gayed & El Ebrashi, Citation2022, p. 92), while exploration capabilities build and new knowledge and target new markets and represents the ability to ‘look for novel technological ideas, create innovative products or services, look for creative ways to satisfy customers’ needs, aggressively […] target new customer groups’ (Gayed & El Ebrashi, Citation2022, p. 92).

Given the scarcity of literature regarding the exaptation potential of capabilities, in particular in a supply chain resilience context, the key issue of how the dynamic interplay between exploitation and exploration supply chain resilience capabilities may lead to exaptation potential remains unanswered. Therefore, this study addresses this gap by asking the following questions:

RQ1.

How do exploitative and exploratory supply chain resilience capabilities influence the exaptation potential after COVID-19?

To answer this question and to understand the exaptation potential, this study builds on an integrative model to distinguish between exploitative and exploratory resilience capabilities. However, in order to categorize the exaptation potential, a more detailed investigation of exploitative and exploratory resilience practices is required. Therefore, the following sub-questions are addressed:

RQ1a.

To what extent do exploitative and exploratory supply chain resilience practices influence the exaptation potential?

RQ1b.

What is the exaptation potential of supply chains resilience capabilities after COVID-19?

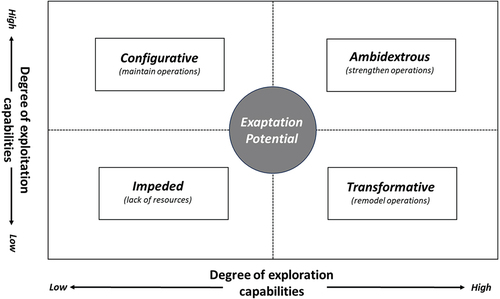

Our main theoretical focus is the distinction between exploitative and exploratory resilience capabilities and how the interaction between them influences the exaptation potential of supply chain capabilities. In particular, to categorize the exploitative and exploratory resilience capabilities, we adopt the integrative model from Herold et al. (Citation2024) which is based on the underlying construct of ambidexterity. More specifically, the model suggests that exploitation capabilities are influenced by the extent how supply chain organizations are able to continuously improve their operations through its existing set of resources and processes, while exploration capabilities are influenced by the extent how supply chain organizations are able to seek, discover and adopt new products, service and process that are unique from those used in the past. Based on the relative degree of the combined exploitative and exploratory resilience capabilities, the model proposes four types of exaptation potentials: Impeded, Configurative, Transformative, and Ambidextrous.

In order to measure the exploitative and exploratory supply chain resilience capabilities and its exaptation potential, we conducted a survey among supply chain senior managers in Australia in June 2023, i.e. what can considered post COVID-19 (WHO, Citation2023). Following Mandal et al. (Citation2016), the questions focused on specific supply chain resilience capabilities and its practices, namely supply chain resilience, supply chain collaboration, supply chain visibility, supply chain flexibility and supply chain velocity. Questions specifically asked to what extent supply chain resilience capabilities have been a) exploited in the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, and b) explored to transform the supply chain for future and long-term resilience. Our sample comprises survey responses from 447 senior managers in Australia from various supply chain industries.

The contribution of this article is threefold: First, we use and integrate the concept of exaptation into the current discourse around supply chain resilience to illustrate how newly acquired capabilities during a crisis are utilized or repurposed after supply chains have returned to the ‘new normal’. Second, we apply an established exploitative and exploratory capabilities model that depicts four different types of exaptation potential for supply chain resilience in supply chain organizations, thereby providing conceptual clarity regarding the varied implications and outcomes linked to the exaptation of resilience capabilities in supply chains. Third, we empirically categorise the exaptation potential in and for supply chains, thereby advancing the literature on supply chain resilience and providing a tool to assess how innovation can be captured in an organisation. Thus, this study presents a more nuanced empirical, as well as theoretical, understanding of the mechanisms through which exploitative and exploratory resilience capabilities influence exaptation potential.

2. Ambidexterity in supply chains: exploitation and exploration capabilities

As the pandemic introduced huge uncertainties in both supply and demand, it highlighted the importance for companies to properly design and manage capabilities to cope with supply chains risk and (Herold & Marzantowicz, Citation2024; Prataviera et al., Citation2022). Due to the COVID-19 related supply chain disruptions, organizations were forced to enhance the resilience of their supply chains in order secure the continuity of their operations, thereby building up and utilizing their intra-organizational dynamic capabilities to address, e.g. mismatches between supply and demand, labour shortages and lack of transport capacities (Dovbischuk, Citation2022; Gebhardt et al., Citation2022; Gultekin et al., Citation2022; Herold & Marzantowicz, Citation2023; Hohenstein, Citation2022). Dynamic capabilities, which can be defined as the firm’s ability to integrate, build, and reconfigure internal and external competences to address rapidly changing environments” (Teece et al., Citation1997, p. 516) can be seen as the result of experience accumulation, knowledge articulation, knowledge codifications and knowledge sharing (Sabahi & Parast, Citation2020) as means to achieve strategic change in a patterned, repeatable and reliable way (Helfat & Peteraf, Citation2003; Helfat & Raubitschek, Citation2018; Teece, Citation2007; Winter, Citation2003). As the actions during the pandemic were rather reactive than proactive (Belhadi et al., Citation2021; Dwaikat et al., Citation2022; Ozdemir et al., Citation2022), the dynamic capabilities perspective can help address how firms respond to changing business environments and specifically how these newly acquired capabilities are utilized or repurposed after COVID-19, i.e. post-crisis (Napoleone & Prataviera, Citation2020).

In an attempt to go beyond the present discourse about supply chain resilience, this article uses the concept of exaptation to examine how these resilience capabilities are utilized after the ‘system [has returned] to its original state or [moved] to a new desirable state after being disturbed’ (Christopher & Peck, Citation2004, p. 8). Exaptation can be defined as ‘the repurposing of artifacts, technologies, processes, skills, organizations, and resources for emergent uses that they were not (initially) designed for’ (Dew & Sarasvathy, Citation2016, p. 167) with scholars claiming that several important inventions, some of which radical, have been exaptive in nature (Gould & Vrba, Citation1982; W. Liu et al., Citation2021; Nayak et al., Citation2020). In a supply chain management context, exaptation offers a route to innovation by allowing capabilities to be co-opted for a new function or a new context and thus can help to explain how newly acquired capabilities during a crisis are utilized or can be repurposed to produce novel reconfiguration of resources after supply chains ‘have returned to their original state’ (Andriani et al., Citation2017; Ardito et al., Citation2021; Nayak et al., Citation2020).

Previous research has indicated that dynamic capabilities depend on exploiting existing technologies and resources to safeguard efficiency as well as the creation of product and service variations through exploration (Brady & Davies, Citation2004; Yalcinkaya et al., Citation2007). In an innovation and exaptation context, exploitation and exploration capabilities are considered dynamic capabilities, as both capabilities are utilized to transform a company’s current resources into different competencies for the new environment (Nayak et al., Citation2020). Scholars agree, however, that despite the substantial differences between the concepts of exploration and exploitation, organizations have to engage in the development and adopt both types of capabilities to succeed in the long-term (March, Citation1991; Wei et al., Citation2021; Yalcinkaya et al., Citation2007). Duncan (Citation1976) used the term ‘ambidexterity’ to illustrate the trade-off between exploiting existing systems and exploring new opportunities and found that developing both exploitative and exploratory capabilities can enhance a company’s position by adapting to an uncertain environment more quickly through integrating resources, leading to competitive advantage.

The relationship between exploitative and exploratory capabilities and supply chain resilience in a COVID-19 context has attracted a lot of scholarly research (Belhadi et al., Citation2022; Gu et al., Citation2021; Pereira et al., Citation2021; Robb et al., Citation2022; Sheng & Saide, Citation2021), but existing literature lacks still frameworks that help to illustrate the interaction between these concepts and, in particular, how these capabilities can be utilized or repurposed post-crisis. In the following sections, we elaborate on each of the concepts and discuss implications of the exploitative and exploratory capabilities in and for the exaptation potential of supply chain resilience.

2.1 Exploitation capabilities in and for the exaptation potential of supply chain resilience

During COVID-19, supply chain managers mainly exploited their capabilities to build supply chain resilience (Han et al., Citation2020; Herold, Nowicka, et al., Citation2021). According to March (Citation1991), exploitation can be defined as ‘the refinement and extension of existing competencies, technologies, and paradigms exhibiting returns that are positive, proximate, and predictable’, thus it corresponds in dynamic capabilities context with what Teece (Citation2007) calls ‘seizing’, i.e. the ‘mobilization of resources to address needs and opportunities, and to capture value from doing so’ (p. 332). For example, in the beginning of the pandemic, supply chain managers were confronted with volatile transport demands when global production halted and trucks were grounded, leading to a drastic cut of transport capacity (Herold, Nowicka, et al., Citation2021). During the recovery phase, however, supply chain managers were confronted with a both a lack of aircraft belly capacity when customers, governments and other related stakeholders put in urgent requests for PPE equipment and asked for transport capacity which was not available on the market (Birshan et al., Citation2020). As a response, some supply chain managers were able to exploit their resources to provide additional capacity. For example, the logistics provider DB Schenker used passenger airlines to increase their transport capacity and removed the seats from three Iceland Air 767s for regular cargo shipments from Asia to Europe and the US (DVZ, Citation2020).

From a theoretical point of view, the degree of exploitation capabilities depend on the supply chain’s ability to continuously adapt the supply chain network through its existing set of resources and processes (March, Citation1991; Prataviera et al., Citation2021). In other words, the degree of exploitation capabilities is linked to how supply chain managers are able to improve, select or maintain relationships with existing suppliers and finding solutions for a more using efficient implementation and execution of existing supply chain resources technologies to drive resilience (Y. Wang et al., Citation2021). As such, the greater the degree of exploitation capabilities, the higher the harvesting and the incorporation of existing operational knowledge that drives resilience. The lesser the degree of exploitation capabilities, the lower the processing capabilities for developing supply chain resilience, thus there is a lack to turn knowledge into action (Roh et al., Citation2022).

Links between exaptation and the exploitation of capabilities can also be found in the literature. As Beltagui et al. (Citation2020) argues, ‘exaptation-driven innovation involves exploiting unintended latent functions of pre-existing technologies’ (p. 1). In other words, while exploitation capabilities rely on existing resources and technologies, the need to innovate in combination with a firm’s flexibility can also lead to previously unintended innovations. Drawing from the DB Schenker example above, we would argue that the increase in transport capacity is not only a result of the exploitation of the existing ecosystem surrounding DB Schenker, but that the flexibility of the organization ‘to apply their knowledge and experience to an unfamiliar challenge’ (W. Liu et al., Citation2022, p. 90) lead an exaptation of their original capabilities, thereby enhancing the resilience of the supply chain.

2.2 Exploration capabilities in and for the exaptation potential of supply chain resilience

Supply chain managers were also exploring new capabilities during the pandemic, in particular the development of new IT solutions and how to digitize certain processes in order to maintain business critical functions (Herold, Nowicka, et al., Citation2021). Exploration can be defined as ‘experimentation with new alternatives having returns that are uncertain, distant, and often negative’ (March, Citation1991, p. 85) and in a dynamic capabilities content, corresponds with the Teece’s (Citation2007) definition to attempt to ‘transform’, that is, the ‘continued renewal’ (p. 332) of the firm as its resources are reconfigured to strategically seize opportunities and respond to threats. For instance, due the pandemic restrictions, supply chain managers had to innovate and drive digitalization to tackle the challenges stemming from the disruptions. A striking example, logistics providers quickly developed solutions for digital freight documents for cross-border checks and also transformed the handwritten POD [Proof of Delivery] to a digital POD (Birshan et al., Citation2020).

From a theoretical point of view, the degree of exploration capabilities depend on the supply chain’s ability to seek, discover and adopt new skills and processes that are unique from those used in the past (March, Citation1991). In other words, the degree of exploration capabilities is linked to the exploratory activities along the supply chain that involve creative and unique solutions based on new approaches and seeking to meet customers’ various needs (Roh et al., Citation2022). As such, the greater the degree of exploration capabilities, the higher the supply chain management’s engagement with novel technological ideas, create innovative products or services and aggressive ventures into new market segments to actively target new customer groups (Gayed & El Ebrashi, Citation2022; Herold et al., Citation2023; Yalcinkaya et al., Citation2007).

Discussing the relationship between exaptation and exploration capabilities in a supply chain resilience context, W. Liu et al. (Citation2022) found that exaptation played a critical role to address the shortage of ventilators during COVID-19 by the ‘repurposing of design, manufacturing, 3D printing, AI, VI, supply chain coordination, and mass-production technologies from […] logistics industries’ (p.86). They also found that the success of technology exaptation depends on the agility of people and their openness to novel ideas, unfamiliar technologies, and unorthodox processes. Studies also show that exaptation usually involves collaborations outside of the ecosystem (Carignani et al., Citation2019). The case of the digital POD from above illustrates the role of exploratory capabilities not only to ‘jump’ to a new strategic state (Fischer et al., Citation2010), but also to experiment, test and implement novel technologies for a resilient operations (Mandal et al., Citation2016; Ponomarov & Holcomb, Citation2009).

3. The implications of exploitative and exploratory resilience capabilities on exaptation potential

Adopting the integrative model from Herold et al. (Citation2024), we use the dimensions of exploitative and exploratory resilience capabilities to understand their interaction and their influence on exaptation strategies. Exploitative capabilities reflect the degree of a supply chain organization’s ability to continuously improve their operations through its existing set of resources and processes, while exploratory capabilities reflect the degree of a supply chain organization’s ability to seek, discover and adopt new products, service and process that are unique from those used in the past. More importantly, for the purpose of this study, we argue that the exaptation potential of supply chain resilience capabilities depends on both exploitative capabilities, i.e. to what extent companies could exploit their capabilities in the beginning or during the COVID-19 pandemic, as well as exploratory capabilities, i.e. to what extent companies have explored, learned and utilized new skills to transform and repurpose their resources post COVID-19 pandemic. Supply chain organizations, however, are confronted with the inherent trade-offs between exploration and exploitation activities and thus the allocation of the company’s resources, leading to varied strategies between ‘serving existing work versus searching for new work’ (Rogan & Mors, Citation2014, 1864). These trade-offs and the associated interplay thus determine the relative degree of exploitative and exploratory capabilities and the exaptation potential. Thereby, this model provides a conceptual foundation to answer RQ1 (‘How do exploitative and exploratory supply chain resilience capabilities influence the exaptation potential after COVID-19?’) and provides subsequently a framework to analyse and categorize carbon management practices and strategies to answer RQ1a (‘To what extent do exploitative and exploratory supply chain resilience practices influence the exaptation potential?’) and RQ1b (‘What is the exaptation potential of supply chains resilience capabilities after COVID-19?’).

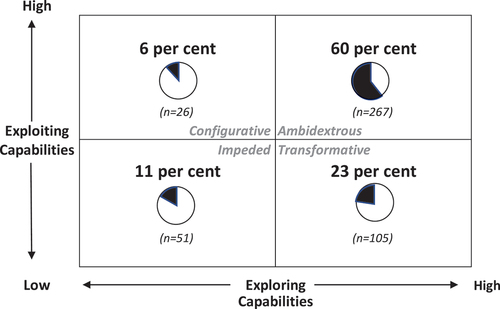

Based on the assumption of potential variation between exploitative and exploratory capabilities, the model proposes four types of exaptation potentials: Impeded, Configurative, Transformative, and Ambidextrous. depicts the four types of exaptation potentials. Below, we describe each type and explain how it implies a distinct level of exaptation potential.

Figure 1. Types of exaptation potential for supply chain resilience capabilities, adapted from Herold et al. (Citation2024).

3.1 Impeded exaptation potential

Impeded exaptation potential is the outcome when supply chains, according to Bode et al. (Citation2011), are ‘exposed to disruptions that impede their supply chain relationships and associated operations’ (p. 833). Mainly due to lack of resources, supply chain management in this quadrant are neither able to effectively react to disruptive, nor can they accommodate latent problems or adjust operations, thereby posing a threat to both competitiveness and its long-term success (Lengnick-Hall, Citation1992). Because these supply chains have a low degree of exploitation capabilities, the flexibility to adapt or redesign the supply chain as well the plan demand or to adjust inventory as a response to the rapidly changing environment stemming from the disruption is rather limited (Banerjee et al., Citation2022; Rajesh, Citation2017). Furthermore, the supply chain operations of this type are characterized by limited innovation capabilities and a low level of digitalization (Busse & Wallenburg, Citation2011; Herold et al., Citation2023). Studies show that in particular sea-, rail- and airfreight supply chains operations are not digitalized and therefore impede the built up of capabilities to quickly react to disruptions (Fruth & Teuteberg, Citation2017; Herold, Ćwiklicki, et al., Citation2021).

Similarly, a low degree of exploration capabilities indicates that supply chain management fails to collaborate with their supply chain partners (Fawcett & Waller, Citation2014), thereby not only fail in buffering activities to enhance residence by implementing safeguards in partnership, but also fail in bridging activities to manage disruption through actions with partners outside of the supply chain ecosystem (Bode et al., Citation2011; Magliocca et al., Citation2023; Meznar & Nigh, Citation1995). Ultimately, the lack of resources or management skills to leads to low exploitation and a low exploration capabilities, thereby not only increasing the chance for organizational inertia (Moradi et al., Citation2021; Singh & Lumsden, Citation1990), but also limiting the exaptation potential to build resilience for short- and long-term success.

3.2 Configurative exaptation potential

A configurative exaptation potential reflect the supply chain’s focus to configure the integrated supply chain network of ‘key supply units, operating throughout the length of the supply chain, be they predominantly internal to a firm where there is a degree of vertical integration, or largely external supply partners where there is significant outsourcing of components, parts, technology or general supply’ (Singh Srai & Gregory, Citation2008, p. 392). Because these supply chains have a high degree of exploitation capabilities, they are in a position to collaborate strategically with their supply chain partners and adapt intra- and inter-organizational processes to maximize the effectiveness and efficiency of material, service and information flows (Flynn et al., Citation2010). However, the high degree of exploitation capabilities in combination with a low degree of exploration capabilities indicates that supply chain management mainly focuses on ‘surviving’ the disruption, i.e. they use their capabilities mainly for short-time adjustment of the network structure or time-limited arrangements with subcontractors to bridge the time until the disruption is over.

As such, supply chains in these quadrant are threatened by what Gayed and El Ebrashi (Citation2022) call ‘success traps’ (p. 6682). Studies found that combination of a high degree of exploitation capabilities with a low degree of exploration capabilities prevent companies from further exploring new resources in a dynamic environment (Gupta et al., Citation2006; Tian et al., Citation2021). In addition, Shi et al. (Citation2020) found that companies in these quadrant can usually rely on sufficient resources, which allows them to ‘focus more on the benefits of exploiting existing markets, products, technologies, customers and processes rather than exploring new markets, products, technologies, customers and processes’(p. 98). This claim is backed up by Singh and Lumsden (Citation1990) who argue that when supply chains ‘enjoy current resources’, managers are more reluctant to explore to avoid putting their current resources in jeopardy. Ultimately, using existing knowledge to configure the current network and processes to maintain the operations during a crisis leads to short-term resilience activities, thereby neglecting the exaptation potential to build long-term resilience building blocks for the supply chain.

3.3 Transformative exaptation potential

Supply chains with a transformative exaptation potential are using the exploration capabilities to expand their existing supply chain scope and to position themselves for the future disruption challenges. One key aspect of the transformational approach is the focus on IT solutions and the digitalization of supply chains (Stank et al., Citation2019; Weisz et al., Citation2023). Herold, Nowicka, et al. (Citation2021) found supply chains were under pressure during COVID-19 to digitize critical processes, thereby raising awareness and accelerating the digital transformation. Supply chains in this quadrant, for example, see investments in digitalization for (big) data management not to be an ‘if’ anymore, but increasingly a ‘when’ question (Cichosz et al., Citation2020; Mikl et al., Citation2021). On an operational level, managers implement data management to further consolidate shipments and better plan last-mile deliveries (Mikl et al., Citation2020). On a strategic level, these supply chains use data for accurate tracking processes that can help to adapt shipping transportation speed (e.g. slow steaming), so that the ‘floating storage’ arrives in warehouses when needed (Lee, Citation2017).

However, supply chains in these quadrant are threatened by so-called ‘failure traps’ (Gayed & El Ebrashi, Citation2022, p. 6682). Supply chains combing a low degree of exploitation capabilities with a high degree of exploration capabilities may be confronted with uncertain results of experiments with novel and untested structures and technologies, leading to ‘failure’ and a reduction of efficiency levels (Anzenbacher & Wagner, Citation2020; Kafetzopoulos, Citation2021). Moreover, Nohria and Gulati (Citation1996) argue that the LSPs in these quadrant usually face a lack of resources, driving supply chain managers to more risk-taking and innovations, and consequently, a focus on their exploration capabilities for adaption. On the one hand, supply chains with a focus on exploration capabilities drive the transformation of the supply chain for more resilience by investing in lasting structural and network changes mainly through digitalization. On the other hand, the neglect of exploitation capabilities may reduce the response time to an immediate disruptive event, thereby utilizing or repurposing the capabilities to build resilience post-crisis.

3.4 Ambidextrous exaptation potential

Supply chains with an ambidextrous exaptation have the capability to exploit existing competences and explore new opportunities with equal dexterity (Lubatkin et al., Citation2006). Scholars argue that an ambidextrous ability also leads to enhanced efficiency, flexibility, alignment and adaptability in an organization (Gibson & Birkinshaw, Citation2004). Because the supply chains of this type have a high degree of exploitation capabilities, they focus on maintaining a relationship with current suppliers, search for supply chain solutions using existing resources and leverage current supply chain technologies, which increase the supply chain’s flexibility to solve problems quickly and efficiently during e.g. new service or product development as a response to a disruption (Kristal et al., Citation2010; Sheremata, Citation2000). But due to the high degree of exploration capabilities, supply chains in this quadrant are also seeking for supply chain solutions based on novel approaches and creative ways to provide a better customer experience, which can lead to market and technological leadership in the long term because supply chains are able to utilize their capabilities to deal with environmental shift stemming from the disruption.

Ultimately, the combination of the high degree of both concepts indicate that the supply chain managers have the ‘ability to orchestrate the complex trade-offs that the simultaneous pursuit of exploration and exploitation requires’ (O’Reilly & Tushman, Citation2004, p. 6), thereby laying the foundation to utilize the exaptation potential to respond quickly to new and unexpected demands from customers during a disruption as well as the invest in new markets and technologies to build a more competitive and resilient supply chain long term.

4. Research Design

To address the research aim of understanding how resilience capabilities influence exaptation strategies, and the subsequent categorization according to the model (), the exploitative and exploratory resilience capabilities in supply chain organizations needs to be examined. We adopt a quantitative survey approach that focuses a) on five specific supply chain resilience capabilities and its practices, and b) how these resilience capabilities and practices have changed between pre-COVID-19 and post-COVID-19. The analysis follows a two step-approach: First, we examine to what extent exploitative and exploratory resilience capabilities have been utilized before and after the pandemic. An analysis of the five resilience capabilities and its practices will allow us to understand the interaction between exploitative and exploratory resilience capabilities and provides the foundation for the second step: the categorization of the supply chain capabilities according to the exaptation potential model.

4.1 Sample

Data was gathered through the online research panel provider Dynata. Dynata is subscription data platform that allows researchers to create surveys that are sent in a in double-blind process to a potential respondent panel. The selection process of potential participants is based on knowledge of the survey topic and specific characteristics of the participants. Our target population were senior managers and senior professionals in Australia with global supply chain responsibilities, as our research required expert company assessments. To ensure participant and data quality, a robust screening process based a list of criteria around demographics, behavioural and attitudinal in line with the study’s research aims was applied by Dynata. Particular attention was paid to the verification of respondents and their familiarity with supply chain capabilities as a qualification for participation. More specifically, participants were only considered as qualified if they have been in their role over the last four years, i.e. they were part of company before, during and after COVID-19 and if they have held a senior managerial or senior operational position to manage the company’s supply chain. This was followed by a rigorous validation process to prevent false identities and double entries. Confirmed participants were routed to the online survey questionnaire. The final sample comprised responses of 447 senior managers from a range of Australian industries, thereby large enough sample to sufficiently describe the phenomenon of interest and address the research question.

4.2 Measuring supply chain resilience capabilities and its exaptation potential

To measure the supply chain capabilities, we used 15 resilience management practices (RMPs) from Mandal et al. (Citation2016) that indicates the extent to these have been applied, utilized or repurposed in the supply chain. In order to examine the RMPs, we grouped the questions into five sections to measure the ‘the intensity of concern with each category’ (Weber, Citation1990, p. 39) covering supply chain resilience, supply chain collaboration, supply chain visibility, supply chain flexibility and supply chain velocity. describes the RMPs in detail and distinguishes between the supply chain capabilities. The measurement instrument was included twice to measure a) resilience capabilities at the beginning of Covid-19, and b) after Covid-19, and thus, to allow for a direct comparison between the periods. Respondents were asked to rate each of the RMPs retrospectively on a 6-point Likert scale, ranging from ‘Disagree very strongly’ (1) to ‘Agree very strongly’(6).

Table 1. Resilience Management Practices (RMPs), adapted from Mandal et al. (Citation2016).

To categorize the four types of exaptation potential based on the extent to which exploitative and exploratory RMPs are utilized, we distinguish whether the exploitative and exploratory RMPs are utilized to a ‘greater extent’ or to a ‘lesser extent’. The measure the extent of each RMP, we use the aggregated scores from the exploitative and exploratory RMPs distinguishing between ‘Agree’ and ‘Disagree’ scores. This allowed us to calculate exploitative and exploratory scores from the RMPs and the five capabilities sections to identify and categorize the exaptation potential type and answer sub-question RQ1a (‘To what extent do exploitative and exploratory supply chain resilience practices influence the exaptation potential’) and RQ1b (What is the exaptation potential of supply chains resilience capabilities after COVID-19?).

For instance, to categorize the extent of exploitative RMPs (i.e. to what extent capabilities are exploited), every participant that responded with ‘Agree’ is considered to have utilized exploitative capabilities to a greater extent, placing it either in the Configurative or Ambidextrous type, depending on the exploratory RMP scores. In contrast, every response involving ‘Disagree’ is considered to have utilized exploitative RMPs to a lesser extent, placing them in the Impeded or Transformative type. To categorize the extent of exploratory RMPs (i.e. to what extent capabilities are explored), every participant that responded with ‘Agree’ is considered to have utilized exploratory capabilities to a greater extent, placing it either in the Transformative or Ambidextrous type, depending on the exploratory RMP scores. Every response involving ‘Disagree’ is considered to have utilized exploratory RMPs to a lesser extent, placing them in the Impeded or Configurative type. As the calculation is based on multiple criteria, the cumulative scores place each response in a different quadrant. For example, if a participant responds to have utilized exploitative RMPs to a lesser extent and exploratory RMPs to a lesser extent, it is placed in the Impeded type. If a participant responds to have utilized exploitative RMPs to a greater extent and exploratory RMPs to a greater extent, the response is placed in the Ambidextrous type.

5. Results

The exploitative and exploratory RMPs research design allows for a categorization of the exaptation potential according to the extent of the utilized 15 RMPs. Following our exaptation potential model (see ), we allocated the supply chain resilience responses according to the specific exploitative and exploratory RMPs and capabilities into the four types Impeded, Configurative, Transformative, and Ambidextrous. The results are shown in , where we placed each supply chain based on their respective exploitative and exploratory RMPs score. Out of the 447 responses, 60 per cent (n = 267) of the sample were allocated into the Ambidextrous type, 23 per cent (n = 105) were allocated into the Transformative type, 11 per cent (n = 51) were allocated into the Impeded type, while the remaining 6 per cent (n = 26) were allocated into the Configurative type.

The result show that 83 per cent of supply chains have Transformative and Ambidextrous exaptation potential of their respective resilience capabilities, emphasizing the greater role of exploratory RMPs when building supply chain resilience after COVID-19. However, 66 per cent of supply chains show Configurative and Ambidextrous exaptation potential of their respective resilience capabilities, highlighting the greater role of exploitative RMPs when building supply chain resilience. In contrast, only 11 per cent of supply chains show an Impeded exaptation potential, having utilized both exploitative and exploratory RMPs and capabilities to a lesser extent.

To understand the driver behind the exaptation potential of supply chain resilience capabilities, we performed an analysis of the exploitative and exploratory RMPs and capabilities per exaptation potential type. The results can be found in . For a better understanding, the converted the scores into percentages, i.e. the table shows to what extent exploitative and exploratory RMPs and capabilities have been utilized.

Table 2. Scores by exaptation potential type.

The results show that similarities and difference between the utilization of exploitative and exploratory RMPs and capabilities in and for supply chains. For example, supply chains with Ambidextrous exaptation potential, supply chain collaborations and supply chain flexibility capabilities are the main drivers (with 67 and 60 per cent, respectively), in particular the ability to work with key suppliers along the supply chain (69 per cent) and the ability to develop strategic objectives jointly with supply chain partners. Supply chains with Transformative exaptation potential are driven mainly by the supply chain resilience, supply chain visibility and supply chain velocity capabilities (with 26 per cent each), in particular with the ability to be prepared for unexpected events (32 per cent) and the ability to rapidly deal with threats in the environment (28. per cent). The main drivers behind supply chains with Impeded exaptation potential are the supply chain flexibility and supply chain velocity capabilities (with 12 per cent each), in particular with the ability to quickly respond to change in the environment (13 per cent) and the ability to quickly address opportunities in the environment (14 per cent). Supply chains with Configurative exaptation potential are driven by the supply chain resilience and supply chain velocity capabilities (with 7 per cent each), in particular with the ability to quickly respond to change in the environment (8 per cent).

The categorization into different model types and the analysis of the RMP drives allows for a discussion and interesting insights into the exaptation potential and the role of exploitative and exploratory capabilities.

6. Discussion

The results provide an interesting insight into the exaptation potential of supply chain resilience capabilities. Overall, the results show that the majority of supply chains have built both exploitative and exploratory capabilities during COVID-19, thus companies seem to be better prepared for upcoming disruptive events. Interestingly, the numbers show rather homogenous results across the exaptation potential types, i.e. the respective types (Impeded, Configurative, Transformative, and Ambidextrous) show similar results across their RMPs and capabilities, indicating that supply chain resilience capabilities are consistently and collectively developed and utilized rather than individually. One of the key findings of this study is that 83 per cent of supply chains show Transformative and Ambidextrous exaptation potential, emphasizing the greater role of exploratory RMPs when building supply chain resilience after COVID-19. In particular, 267 out of 447 supply chains have utilized both exploitative and exploratory capabilities to a greater extent, thus showing Ambidextrous exaptation potential. In other words, these supply chain showed how to exploit existing knowledge and how to build new knowledge to increase the resilience along the supply chain. For example, Ambidextrous exaptation potential could be observed in the rapid adoption of technologies throughout the pandemic to help enforce social distancing in warehouses. The implementation of robotic goods-to-person (G2P) systems that helped not only to move goods from one person to another, but also led to better warehouse efficiency by increased productivity improved storage density (Dhaliwal, Citation2021). This transformed the emergent functionality into a new service function, thereby not only replacing a manual process with a digitized one, but also controlling the adaptive trajectory of the technology (Codini et al., Citation2023).

The results also show that 105 supply chains have utilized exploratory capabilities to a greater extent while utilizing exploitative capabilities to a lesser extent, thus showing Transformative exaptation potential. For example, the logistics provider DB Schenker used passenger airlines to increase their transport capacity and removed the seats from three Iceland Air 767s for regular cargo shipments from Asia to Europe and the US (DVZ, Citation2020). Such a process is markedly different to the usual innovation adoption processes, where innovation is adapted over time to suit a particular purpose. In the case of DB Schenker, exaptation took place by starting and exploring a co-development with key partners (the passenger airline) that operate in businesses other than the DB Schenker core business. In other words, using an existing set of capabilities, the original functionality of the passenger airline was turned into a new product/service with market-driven function to create cargo capacity that contributed to resilience of the operations (Codini et al., Citation2023). The analysis also shows that 51 supply chains have utilized exploitative capabilities to a greater extent while utilizing exploratory capabilities to a lesser extent, thus showing Configurative exaptation potential. For example, during the pandemic, configurative exaptation increased use of parcel lockers for deliveries during COVID-19. In order to keep human contact during the delivery process to a minimum, logistics service provider exploited the use of parcel lockers to optimize internal resources, thereby elevating a rather peripheral service offering to a core business concept (Sułkowski et al., Citation2022; X. Wang et al., Citation2023).

As the majority of supply chains (with 60 per cent) show Ambidextrous exaptation potential, the findings also expand and advance the literature on supply chain resilience in attaining ambidexterity. Supply chain literature frequently discusses the tensions and its associated trade-offs between exploitative and exploratory capabilities, i.e. companies have to decide whether to allocate resources into exploitative or exploratory capabilities, but cannot pursue both simultaneously (Berti & Cunha, Citation2023; Kristal et al., Citation2010; Silvestre et al., Citation2023). In contrast, our results show that the majority of supply chains adopt an ‘attained ambidexterity’ approach (Eltantawy, Citation2016) instead, i.e. ambidexterity is viewed as a ‘higher-order construct’ (March, Citation1991) stemming from the organizational and exploitative and exploratory attainments. Only recently, supply chain literature has taken on that view (Eltantawy, Citation2016; Narasimhan & Narayanan, Citation2013; Roldan Bravo et al., Citation2018), proposing that ambidexterity can be attained by simultaneously pursuing and developing exploitative and exploratory capabilities. Within this approach, exploitative and exploratory attainments are considered ambidextrous, thus it shifts the discussion away from the assumption that trade-offs of resources are necessary to attain ambidexterity.

7. Conclusion

By expanding insight into the concepts and implications of exaptation potential in and for supply chain resilience capabilities post COVID-19, this paper advances and expands existing supply chain literature. First, the integration of the exaptation potential opens a new chapter on how supply chain resilience capabilities are utilized after a disruptive event. By using a conceptual model based on exploitation and exploration capabilities, we not only provide a strong theoretical foundation to examine the exaptation strategies in and for supply chain resilience, but the four types of exaptation potentials lead to a better understanding of the interactions between capabilities utilization during and after a disruptive event. We thereby contribute to the existing supply chain literature by focusing on resilience and identify how organizations can capture innovation from the newly acquired supply chain resilience capabilities.

Second, we categorized supply chain resilience not only into five specific capabilities, but also developed and applied 15 measurable resilience practices to assess to what extent these capabilities and practices are utilized. This categorization and the provision of measurable components contributes to better micro-level understanding of what resilience means in the context of both supply chains and for the concept of dynamic capabilities. Third, in contrast to literature that claims that supply chains are confronted with an inherent trade-off between exploitative and exploratory capabilities, we found that the majority of supply chains is able to simultaneously pursue and develop exploitative and exploratory capabilities. We thereby contribute to the discussion about ambidexterity and provide clear outcomes in the context of supply chain resilience capabilities.

The findings also have managerial implications. Our results indicate that managers need to adapt to changes in the environment by exploitative processes, but also be able to transform their capabilities via explorative processes at the same time. In other words, managers who focus only on one of the two processes are unlikely to capture all innovation and develop full exaptation potential. As such, one implication for managers is to allocate resources to focus on both exploitative and explorative processes and capabilities, thus utilizing internal competencies and engage with the external ecosystem to further drive supply chain collaboration, visibility, flexibility and velocity for resilience.

However, the study’s findings and implications must be viewed in the light of its research limitations. The applied and developed framework represents a first step to categorize the extent of exploitative and exploratory capabilities to identify the exaptation potential, but exaptation might be influenced by other factors. As the emerging concept of exaptation will likely become increasingly important for managers and academics in a business context, identifying drivers provides an interesting avenue for future research. And although our findings provide a better understanding of the role exaptation in supply chain resilience, our sample size was restricted to Australian senior managers, we are careful to generalize our claims. Moreover, although we are convinced that our findings provide insights and a better understanding of resilience capabilities pre-and post-pandemic, the participants had to answer the questions retrospectively, so responses may have been subject to measurement bias. We also need to highlight that we while we are confident that the results are transferable to other regions, the survey was restricted to Australia, so we need take into account that Australian supply chain may differ from other global supply chains due their geographical and industry-specific position. In addition, we restricted our dynamic capabilities view to exploitation and exploration capabilities, but other concepts that influence both exaptation and supply chain resilience exist in practice. We encourage future researchers to extend our framework by integrating other concepts, beyond the concept of ambidexterity. Overall, it seems that research dealing with exaptation in the supply chain resilience domain is still in its infancy. Future research will help to understand how exaptation impact supply chain resilience and how organizations can capture innovation from the newly acquired capabilities after a disruptive event.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, DMH, upon reasonable request.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Andriani, P., Ali, A., & Mastrogiorgio, M. (2017). Measuring exaptation and its impact on innovation, search, and problem solving. Organization Science, 28(2), 320–24. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.2017.1116

- Andriani, P., & Carignani, G. (2014). Modular exaptation: A missing link in the synthesis of artificial form. Research Policy, 43(9), 1608–1620. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2014.04.009

- Anzenbacher, A., & Wagner, M. (2020). The role of exploration and exploitation for innovation success: Effects of business models on organizational ambidexterity in the semiconductor industry. International Entrepreneurship & Management Journal, 16(2), 571–594. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11365-019-00604-6

- Ardito, L., Coccia, M., & Messeni Petruzzelli, A. (2021). Technological exaptation and crisis management: Evidence from COVID‐19 outbreaks. R&D Management, 51(4), 381–392. https://doi.org/10.1111/radm.12455

- Banerjee, T., Trivedi, A., Sharma, G. M., Gharib, M., & Hameed, S. S. (2022). Analyzing organizational barriers towards building postpandemic supply chain resilience in Indian MSMEs: A grey-DEMATEL approach. Benchmarking: An International Journal, 30(6), 1966–1992. https://doi.org/10.1108/BIJ-11-2021-0677

- Beer, E., Mikl, J., Schramm, H.-J., & Herold, D. M. (2022). Resilience strategies for freight transportation: An overview of the different transport modes responses. In S. Kummer, T. Wakolbinger, L. Novoszel, & A. M. Geske (Eds.), Supply chain resilience: insights from theory and practice (pp. 263–272). Springer Nature.

- Belhadi, A., Kamble, S., Jabbour, C. J. C., Gunasekaran, A., Ndubisi, N. O., & Venkatesh, M. (2021). Manufacturing and service supply chain resilience to the COVID-19 outbreak: Lessons learned from the automobile and airline industries. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 163, 120447. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2020.120447

- Belhadi, A., Kamble, S. S., Venkatesh, M., Jabbour, C. J. C., & Benkhati, I. (2022). Building supply chain resilience and efficiency through additive manufacturing: An ambidextrous perspective on the dynamic capability view. International Journal of Production Economics, 249, 108516. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpe.2022.108516

- Beltagui, A., Rosli, A., & Candi, M. (2020). Exaptation in a digital innovation ecosystem: The disruptive impacts of 3D printing. Research Policy, 49(1), 103833. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2019.103833

- Berti, M., & Cunha, M. P. E. (2023). “Paradox, dialectics or trade‐offs? A double loop model of paradox.” Journal of Management Studies, 60(4), 861–888.

- Birshan, M., Lund, S., Manyika, J., Woetzel, J., Bariball, E., Krishnan, M., Alicke, K., George, K., Smit, S., & Swan, D. (2020). Risk, resilience, and rebalancing in global value chains, McKinsey Global Institute.

- Bode, C., Wagner, S. M., Petersen, K. J., & Ellram, L. M. (2011). Understanding responses to supply chain disruptions: Insights from information processing and resource dependence perspectives. Academy of Management Journal, 54(4), 833–856. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2011.64870145

- Brady, T., & Davies, A. (2004). Building project capabilities: From exploratory to exploitative learning. Organization Studies, 25(9), 1601–1621. https://doi.org/10.1177/0170840604048002

- Busse, C., & Wallenburg, C. M. (2011). Innovation management of logistics service providers. International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics Management, 41(2), 187–218. https://doi.org/10.1108/09600031111118558

- Carignani, G., Cattani, G., & Zaina, G. (2019). Evolutionary chimeras: A Woesian perspective of radical innovation. Industrial and Corporate Change, 28(3), 511–528. https://doi.org/10.1093/icc/dty077

- Carissimi, M. C., Prataviera, L. B., Creazza, A., Melacini, M., & Dallari, F. (2023). Blurred lines: The timeline of supply chain resilience strategies in the grocery industry in the time of covid-19. Operations Management Research, 16(1), 80–98. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12063-022-00278-4

- Christopher, M., & Peck, H. (2004). Building the resilient supply chain. The International Journal of Logistics Management, 15(2), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1108/09574090410700275

- Cichosz, M., Wallenburg, C. M., & Knemeyer, A. M. (2020). Digital transformation at logistics service providers: Barriers, success factors and leading practices. The International Journal of Logistics Management, 31(2), 209–238. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJLM-08-2019-0229

- Codini, A. P., Abbate, T., & Petruzzelli, A. M. (2023). Business Model Innovation and exaptation: A new way of innovating in SMEs. Technovation, 119, 102548. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.technovation.2022.102548

- Coutu, D. L. (2002). How resilience works. Harvard Business Review, 80(5), 46–56.

- Dew, N., & Sarasvathy, S. D. (2016). Exaptation and niche construction: Behavioral insights for an evolutionary theory. Industrial and Corporate Change, 25(1), 167–179. https://doi.org/10.1093/icc/dtv051

- Dhaliwal, A. (2021). Reinventing logistics: Use of AI & Robotics technologies. Business Research and Innovation, 147.

- Dooley, L., & Som, O. (2018). “Process exaptation: The innovation nucleus of non-R&D intensive SME’s?” In ISPIM Innovation Symposium. The International Society for Professional Innovation Management (ISPIM), Stockholm, Sweden (pp. 1–17).

- Dovbischuk, I. (2022). Innovation-oriented dynamic capabilities of logistics service providers, dynamic resilience and firm performance during the COVID-19 pandemic. The International Journal of Logistics Management, 33(2), 499–519. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJLM-01-2021-0059

- Duncan, R. B. (1976). The ambidextrous organization: Designing dual structures for innovation. In The Management of Organization (pp. 167–188). Elsevier.

- DVZ. (2020). China-Shuttle: DB Schenker kooperiert mit Icelandair. Deutsche Verkehrszeitung. https://www.dvz.de/rubriken/land/detail/news/china-shuttle-db-schenker-kooperiert-mit-icelandair.html

- Dwaikat, N. Y., Zighan, S., Abualqumboz, M., & Alkalha, Z. (2022). The 4Rs supply chain resilience framework: A capability perspective. Journal of Contingencies and Crisis Management, 30(3), 281–294. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-5973.12418

- Eltantawy, R. A. (2016). The role of supply management resilience in attaining ambidexterity: A dynamic capabilities approach. Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing, 31(1), 123–134. https://doi.org/10.1108/JBIM-05-2014-0091

- Fawcett, S. E., & Waller, M. A. (2014). Supply chain game changers—mega, nano, and virtual trends—and forces that impede supply chain design (ie, building a winning team). Journal of Business Logistics, 35(3), 157–164.

- Fischer, T., Gebauer, H., Gregory, M., Ren, G., & Fleisch, E. (2010). Exploitation or exploration in service business development? Insights from a dynamic capabilities perspective. Journal of Service Management, 21(5), 591–624.

- Flynn, B. B., Huo, B., & Zhao, X. (2010). The impact of supply chain integration on performance: A contingency and configuration approach. Journal of Operations Management, 28(1), 58–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jom.2009.06.001

- Fruth, M., & Teuteberg, F. (2017). Digitization in maritime logistics—what is there and what is missing? Cogent Business & Management, 4(1), 1411066.

- Gayed, S., & El Ebrashi, R. (2022). Fostering firm resilience through organizational ambidexterity capability and resource availability: Amid the COVID-19 outbreak. International Journal of Organizational Analysis, 31(1), 253–275. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJOA-09-2021-2977

- Gebhardt, M., Spieske, A., Kopyto, M., & Birkel, H. (2022). Increasing global supply chains’ resilience after the COVID-19 pandemic: Empirical results from a Delphi study. Journal of Business Research, 150, 59–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2022.06.008

- Gibson, C. B., & Birkinshaw, J. (2004). The antecedents, consequences, and mediating role of organizational ambidexterity. Academy of Management Journal, 47(2), 209–226. https://doi.org/10.2307/20159573

- Gölgeci, I., & Ponomarov, S. Y. (2015). How does firm innovativeness enable supply chain resilience? The moderating role of supply uncertainty and interdependence. Technology Analysis & Strategic Management, 27(3), 267–282.

- Gould, S. J., & Vrba, E. S. (1982). Exaptation—a missing term in the science of form. Paleobiology, 8(1), 4–15. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0094837300004310

- Gu, M., & Huo, B. (2017). The impact of supply chain resilience on company performance: A dynamic capability perspective. Paper presented at the Academy of Management Proceedings, Atlanta, GA.

- Gultekin, B., Demir, S., Gunduz, M. A., Cura, F., & Ozer, L. (2022). The logistics service providers during the COVID-19 pandemic: The prominence and the cause-effect structure of uncertainties and risks. Computers & Industrial Engineering, 165, 107950. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cie.2022.107950

- Gupta, A. K., Smith, K. G., & Shalley, C. E. (2006). The interplay between exploration and exploitation. Academy of Management Journal, 49(4), 693–706. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2006.22083026

- Gu, M., Yang, L., & Huo, B. (2021). The impact of information technology usage on supply chain resilience and performance: An ambidexterous view. International Journal of Production Economics, 232, 107956. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpe.2020.107956

- Han, Y., Chong, W. K., & Li, D. (2020). A systematic literature review of the capabilities and performance metrics of supply chain resilience. International Journal of Production Research, 58(15), 4541–4566. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207543.2020.1785034

- Helfat, C. E., & Peteraf, M. A. (2003). The dynamic resource‐based view: Capability lifecycles. Strategic Management Journal, 24(10), 997–1010. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.332

- Helfat, C. E., & Raubitschek, R. S. (2018). Dynamic and integrative capabilities for profiting from innovation in digital platform-based ecosystems. Research Policy, 47(8), 1391–1399. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2018.01.019

- Herold, D. M., Ćwiklicki, M., Pilch, K., & Mikl, J. (2021). The emergence and adoption of digitalization in the logistics and supply chain industry: An institutional perspective. Journal of Enterprise Information Management, 34(6), 1917–1938. https://doi.org/10.1108/JEIM-09-2020-0382

- Herold, D. M., Fahimnia, B., & Breitbarth, T. (2023). The digital freight forwarder and the incumbent: A framework to examine disruptive potentials of digital platforms. Transportation Research Part E: Logistics & Transportation Review, 176, 103214. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tre.2023.103214

- Herold, D. M., & Marzantowicz, Ł. (2023). Supply chain responses to global disruptions and its ripple effects: An institutional complexity perspective. Operations Management Research, 16(4), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12063-023-00404-w

- Herold, D. M., & Marzantowicz, Ł. (2024). Neo-institutionalism in supply chain management: From supply chain susceptibility to supply chain resilience. Management Research Review. https://doi.org/10.1108/MRR-08-2023-0572

- Herold, D. M., Nowicka, K., Pluta-Zaremba, A., & Kummer, S. (2021). COVID-19 and the pursuit of supply chain resilience: Reactions and “lessons learned” from logistics service providers (LSPs). Supply Chain Management: An International Journal, 26(6), 702–714.

- Herold, D. M., Prataviera, L. B., & Nowicka, K. (2024). From exploitation and exploration to exaptation? A logistics service provider (LSP) perspective on building supply chain resilience capabilities during disruptions. The International Journal of Logistics Management. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJLM-02-2023-0077

- Hohenstein, N.-O. (2022). Supply chain risk management in the COVID-19 pandemic: Strategies and empirical lessons for improving global logistics service providers’ performance. The International Journal of Logistics Management, 33(4), 1336–1365. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJLM-02-2021-0109

- Ivanov, D., & Das, A. (2020). Coronavirus (COVID-19/SARS-CoV-2) and supply chain resilience: A research note. International Journal of Integrated Supply Management, 13(1), 90–102.

- Ivanov, D., & Dolgui, A. (2020). Viability of intertwined supply networks: Extending the supply chain resilience angles towards survivability. A position paper motivated by COVID-19 outbreak. International Journal of Production Research, 58(10), 2904–2915.

- Kafetzopoulos, D. (2021). Organizational ambidexterity: Antecedents, performance and environmental uncertainty. Business Process Management Journal, 27(3), 922–940. https://doi.org/10.1108/BPMJ-06-2020-0300

- Kristal, M. M., Huang, X., & Roth, A. V. (2010). The effect of an ambidextrous supply chain strategy on combinative competitive capabilities and business performance. Journal of Operations Management, 28(5), 415–429. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jom.2009.12.002

- Lee, C. (2017). A GA-based optimisation model for big data analytics supporting anticipatory shipping in retail 4.0. International Journal of Production Research, 55(2), 593–605.

- Lengnick-Hall, C. A. (1992). Innovation and competitive advantage: What we know and what we need to learn. Journal of Management, 18(2), 399–429. https://doi.org/10.1177/014920639201800209

- Liu, W., Beltagui, A., & Ye, S. (2021). Accelerated innovation through repurposing: Exaptation of design and manufacturing in response to COVID‐19. R&D Management, 51(4), 410–426. https://doi.org/10.1111/radm.12460

- Liu, W., Beltagui, A., Ye, S., & Williamson, P. (2022). Harnessing exaptation and ecosystem strategy for accelerated innovation: Lessons from the VentilatorChallengeUK. California Management Review, 64(3), 78–98. https://doi.org/10.1177/00081256211056651

- Liu, C.-L., & Lee, M.-Y. (2018). Integration, supply chain resilience, and service performance in third-party logistics providers. The International Journal of Logistics Management, 29(1), 5–21. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJLM-11-2016-0283

- Lubatkin, M. H., Simsek, Z., Ling, Y., & Veiga, J. F. (2006). Ambidexterity and performance in small-to medium-sized firms: The pivotal role of top management team behavioral integration. Journal of Management, 32(5), 646–672. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206306290712

- Magliocca, P., Herold, D. M., Canestrino, R., Temperini, V., & Albino, V. (2023). The role of start-ups as knowledge brokers: A supply chain ecosystem perspective. Journal of Knowledge Management, 27(10), 2625–2641. https://doi.org/10.1108/JKM-07-2022-0593

- Mandal, S., Bhattacharya, S., Korasiga, V. R., & Sarathy, R. (2017). The dominant influence of logistics capabilities on integration: Empirical evidence from supply chain resilience. International Journal of Disaster Resilience in the Built Environment, 8(4), 357–374. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJDRBE-05-2016-0019

- Mandal, S., Sarathy, R., Korasiga, V. R., Bhattacharya, S., & Dastidar, S. G. (2016). Achieving supply chain resilience: The contribution of logistics and supply chain capabilities. International Journal of Disaster Resilience in the Built Environment, 7(5), 544–562. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJDRBE-04-2016-0010

- March, J. G. (1991). Exploration and exploitation in organizational learning. Organization Science, 2(1), 71–87. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.2.1.71

- Meznar, M. B., & Nigh, D. (1995). Buffer or bridge? Environmental and organizational determinants of public affairs activities in American firms. Academy of Management Journal, 38(4), 975–996.

- Mikl, J., Herold, D. M., Ćwiklicki, M., & Kummer, S. (2021). The impact of digital logistics start-ups on incumbent firms: A business model perspective. The International Journal of Logistics Management, 32(4), 1461–1480. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJLM-04-2020-0155

- Mikl, J., Herold, D. M., Pilch, K., Ćwiklicki, M., & Kummer, S. (2020). Understanding disruptive technology transitions in the global logistics industry: The role of ecosystems. Review of International Business & Strategy, 31(1), 62–79. https://doi.org/10.1108/RIBS-07-2020-0078

- Moradi, E., Jafari, S. M., Doorbash, Z. M., & Mirzaei, A. (2021). Impact of organizational inertia on business model innovation, open innovation and corporate performance. Asia Pacific Management Review, 26(4), 171–179. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmrv.2021.01.003

- Napoleone, A., & Prataviera, L. B. (2020)August-September30-3. Reconfigurable manufacturing: Lesson learnt from the COVID-19 outbreak. Paper presented at the Advances in Production Management Systems. The Path to Digital Transformation and Innovation of Production Management Systems: IFIP WG 5.7 International Conference, APMS 2020, Novi Sad, Serbia, Proceedings, Part I.

- Narasimhan, R., & Narayanan, S. (2013). Perspectives on supply network–enabled innovations. The Journal of Supply Chain Management, 49(4), 27–42. https://doi.org/10.1111/jscm.12026

- Nayak, A., Chia, R., & Canales, J. I. (2020). Noncognitive microfoundations: Understanding dynamic capabilities as idiosyncractically refined sensitivities and predispositions. Academy of Management Review, 45(2), 280–303. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2016.0253

- Nohria, N., & Gulati, R. (1996). Is slack good or bad for innovation? Academy of Management Journal, 39(5), 1245–1264.

- O’Reilly, C. A., & Tushman, M. L. (2004). The ambidextrous organization. Harvard Business Review, 82(4), 74–83.

- Ozdemir, D., Sharma, M., Dhir, A., & Daim, T. (2022). Supply chain resilience during the COVID-19 pandemic. Technology in Society, 68, 101847. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techsoc.2021.101847

- Pereira, M. M. O., Silva, M. E., & Hendry, L. C. (2021). Supply chain sustainability learning: The COVID-19 impact on emerging economy suppliers. Supply Chain Management: An International Journal, 26(6), 715–736. https://doi.org/10.1108/SCM-08-2020-0407

- Pettit, T. J., Croxton, K. L., & Fiksel, J. (2019). The evolution of resilience in supply chain management: A retrospective on ensuring supply chain resilience. Journal of Business Logistics, 40(1), 56–65. https://doi.org/10.1111/jbl.12202

- Ponomarov, S. Y., & Holcomb, M. C. (2009). Understanding the concept of supply chain resilience. The International Journal of Logistics Management, 20(1), 124–143. https://doi.org/10.1108/09574090910954873

- Prataviera, L. B., Creazza, A., Dallari, F., & Melacini, M. (2021). How can logistics service providers foster supply chain collaboration in logistics triads? Insights from the Italian grocery industry. Supply Chain Management: An International Journal.

- Prataviera, L. B., Creazza, A., Melacini, M., & Dallari, F. (2022). Heading for tomorrow: Resilience strategies for post-Covid-19 grocery supply chains. Sustainability, 14(4), 1942. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14041942

- Rajesh, R. (2017). Technological capabilities and supply chain resilience of firms: A relational analysis using Total Interpretive Structural Modeling (TISM). Technological Forecasting & Social Change, 118, 161–169.

- Rake, B., & Hanisch, M. (2023). Repurposing: A collaborative innovation strategy for the digital age. The PDMA Handbook of Innovation and New Product Development, 103.

- Robb, C. A., Kang, M., & Stephens, A. R. (2022). The effects of dynamism, relational capital, and ambidextrous innovation on the supply chain resilience of US firms amid COVID-19. Operations and Supply Chain Management: An International Journal, 15(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.31387/oscm0480326

- Rogan, M., & Mors, M. L. (2014). A network perspective on individual-level ambidexterity in organizations. Organization Science, 25(6), 1860–1877. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.2014.0901

- Roh, J., Tokar, T., Swink, M., & Williams, B. (2022). Supply chain resilience to low-/high-impact disruptions: The influence of absorptive capacity. The International Journal of Logistics Management, 33(1), 214–238. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJLM-12-2020-0497

- Roldan Bravo, M. I., Ruiz-Moreno, A., & Llorens Montes, F. J. (2018). Examining desorptive capacity in supply chains: The role of organizational ambidexterity. International Journal of Operations & Production Management, 38(2), 534–553. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJOPM-12-2016-0751

- Sabahi, S., & Parast, M. M. (2020). Firm innovation and supply chain resilience: A dynamic capability perspective. International Journal of Logistics: Research & Applications, 23(3), 254–269. https://doi.org/10.1080/13675567.2019.1683522

- Savino, T., Messeni Petruzzelli, A., & Albino, V. (2017). Search and recombination process to innovate: A review of the empirical evidence and a research agenda. International Journal of Management Reviews, 19(1), 54–75. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijmr.12081

- Sheng, M. L., & Saide, S. (2021). Supply chain survivability in crisis times through a viable system perspective: Big data, knowledge ambidexterity, and the mediating role of virtual enterprise. Journal of Business Research, 137, 567–578. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2021.08.041

- Sheremata, W. A. (2000). Centrifugal and centripetal forces in radical new product development under time pressure. The Academy of Management Review, 25(2), 389–408. https://doi.org/10.2307/259020

- Shi, X., Su, L., & Cui, A. P. (2020). A meta-analytic study on exploration and exploitation. Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing, 35(1), 97–115. https://doi.org/10.1108/JBIM-03-2019-0119

- Silvestre, B., Gong, Y., Bessant, J., & Blome, C. (2023). From supply chain learning to the learning supply chain: Drivers, processes, complexity, trade-offs and challenges. International Journal of Operations & Production Management, 43(8), 1177–1194. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJOPM-04-2023-0318

- Singh, J. V., & Lumsden, C. J. (1990). Theory and research in organizational ecology. Annual Review of Sociology, 16(1), 161–195. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.so.16.080190.001113

- Singh Srai, J., & Gregory, M. (2008). A supply network configuration perspective on international supply chain development. International Journal of Operations & Production Management, 28(5), 386–411. https://doi.org/10.1108/01443570810867178

- Stank, T., Esper, T., Goldsby, T. J., Zinn, W., & Autry, C. (2019). Toward a digitally dominant paradigm for twenty-first century supply chain scholarship. International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics Management, 49(10), 956–971. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJPDLM-03-2019-0076

- Sułkowski, Ł., Kolasińska-Morawska, K., Brzozowska, M., Morawski, P., & Schroeder, T. (2022). Last mile logistics innovations in the courier-express-parcel sector due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Sustainability, 14(13), 8207. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14138207

- Teece, D. J. (2007). Explicating dynamic capabilities: The nature and microfoundations of (sustainable) enterprise performance. Strategic Management Journal, 28(13), 1319–1350.

- Teece, D. J., Pisano, G., & Shuen, A. (1997). Dynamic capabilities and strategic management. Strategic Management Journal, 18(7), 509–533. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1097-0266(199708)18:7<509:AID-SMJ882>3.0.CO;2-Z

- Tian, H., Dogbe, C. S. K., Pomegbe, W. W. K., Sarsah, S. A., & Otoo, C. O. A. (2021). Organizational learning ambidexterity and openness, as determinants of SMEs’ innovation performance. European Journal of Innovation Management, 24(2), 414–438. https://doi.org/10.1108/EJIM-05-2019-0140

- Wang, X., Wong, Y. D., Kim, T. Y., & Yuen, K. F. (2023). Does COVID-19 change consumers’ involvement in e-commerce last-mile delivery? An investigation on behavioural change, maintenance and habit formation. Electronic Commerce Research and Applications, 101273.

- Wang, Y., Yan, F., Jia, F., & Chen, L. (2021). Building supply chain resilience through ambidexterity: An information processing perspective. International Journal of Logistics: Research & Applications, 1–18.

- Weber, R. P. (1990). Basic content analysis. Sage.

- Wei, S., Liu, W., Lin, Y., Wang, J., & Liu, T. (2021). Smart supply chain innovation model selection: Exploitative or exploratory innovation? International Journal of Logistics: Research & Applications, 1–20.

- Weisz, E., Herold, D. M., & Kummer, S. (2023). Revisiting the bullwhip effect: How can AI smoothen the bullwhip phenomenon? The International Journal of Logistics Management, 34(7), 98–120.

- WHO. (2023). Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic - overview. https://www.who.int/europe/emergencies/situations/covid-19

- Winter, S. G. (2003). Understanding dynamic capabilities. Strategic Management Journal, 24(10), 991–995. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.318

- Yalcinkaya, G., Calantone, R. J., & Griffith, D. A. (2007). An examination of exploration and exploitation capabilities: Implications for product innovation and market performance. Journal of International Marketing, 15(4), 63–93. https://doi.org/10.1509/jimk.15.4.63

- Yu, W., Jacobs, M. A., Chavez, R., & Yang, J. (2019). Dynamism, disruption orientation, and resilience in the supply chain and the impacts on financial performance: A dynamic capabilities perspective. International Journal of Production Economics, 218, 352–362. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpe.2019.07.013