?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

Taking a chairman’s native place of origin in Northern (Southern) China as a proxy for chairman individualism (collectivism), this paper examines how such individualism affects firms’ cost structure decisions within a sample of Chinese listed firms. The results show that individualistic chairmen tend to choose a rigid cost structure. Further analysis shows that this relationship exists only in non-state-owned enterprises, when the board has a low level of independence, and when the firm has a low level of financial leverage. This paper contributes to the literature on firms' cost structure decisions in response to risk and on the effect of managerial individualism (collectivism) on corporate strategic cost management. Moreover, this paper provides implications for Chinese firms to realise the advantages of strategic cost management through managers' leadership roles and to achieve transformation and sustainable development.

1. Introduction

Purchased materials and services account for an increasingly large proportion of firms’ product costs.Footnote1 Accordingly, managers often make strategic decisions about supply chain management. As supply chain management is becoming increasingly complex, strategic cost management, a form of deliberate decision-making, plays an important role in aligning the cost structure of a firm with the establishment and enactment of strategies and in improving the efficiency and effectiveness of value chain management (Aberdeen Group, Citation2005). Strategic cost management can be divided into two primary categories: structural and executional cost management (Anderson & Dekker, Citation2009a, Citation2009b). Structural cost management is a choice among alternative production functions that use different inputs or combinations thereof to meet a particular market demand (Anderson & Dekker, Citation2009a)Footnote2; here, cost structure is defined as a mix of variable inputs (i.e. variable costs) and fixed inputs (i.e. fixed costs). Hence, a flexible cost structure is characterised by a large proportion of variable costs and a small proportion of fixed costs (Banker et al., Citation2014; Kallapur & Eldenburg, Citation2005).

Generally, a change in the cost structure implies significant and possibly irreversible adjustments in the organisational structure and business activities, which may increase a firm’s operational or financial risk. Accordingly, a growing stream of management accounting research focuses on the relationship between a firm’s risk and its cost structure decisions.Footnote3 For example, Kallapur and Eldenburg (Citation2005) and Holzhacker, Krishnan and Mahlendorf (Citation2015a, Citation2015b) document that hospitals with high demand uncertainty are more likely than other hospitals to increase their cost flexibility to reduce risk. Banker et al. (Citation2014) use a sample of U.S. manufacturing firms to show that firms facing higher customer demand uncertainty tend to adopt a less flexible cost structure to reduce congestion costs. Chang et al. (Citation2017) and Jiang et al. (Citation2018) document an association between customer concentration and cost structure, but their results are not consistent. Using data from U.S. listed companies, Chang et al. (Citation2017) find that customer concentration is positively associated with cost elasticity, whereas Jiang et al. (Citation2018) find the opposite result when analysing data from Chinese listed companies. Overall, the studies mentioned above focus on firms’ cost structure decisions in response to demand-side risk from the perspective of the supply chain. Although Aboody et al. (Citation2018) document the impact of reductions in option-based compensation on managerial risk preferences and, in turn, firms’ cost structure decisions, few studies investigate the effects of managers’ personal traits related to risk or external incentive systems on firms’ cost structure decisions. Therefore, understanding how these personal traits of managers affect firms’ cost structure decisions may have important theoretical and practical implications.

The literature on cross-cultural psychology suggests that culture influences individuals’ beliefs and preferences and thus has economic consequences (Alesina & Giuliano, Citation2015; Guiso et al., Citation2006).Footnote4 Culture is difficult to change and devalue, and it is generally considered a ‘given’ trait that accompanies individuals throughout their lifespan and is embedded in their behaviours (Becker, Citation1996). Inspired by cross-cultural psychology, studies in accounting and finance show that managers’ cultural backgrounds, early experiences and family environments affect their personal traits and behaviours and thus affect their decisions on matters such as corporate finance, stock crashes and earnings forecasts (Bennedsen et al., Citation2007; Bertrand & Schoar, Citation2003; Cronqvist et al., Citation2012; Kim et al., Citation2016; Malmendier et al., Citation2011). However, few management accounting studies provide evidence of the association between managers’ personal traits and firms’ cost management from the perspective of cross-cultural psychology (Abernethy & Wallis, Citation2019).

In this study, we examine the effect of one personal trait of chairmen, individualism, on firms’ cost structure decisions in China. Through their leadership role in a firm (Krause et al., Citation2016; Withers & Fitza, Citation2017), the chairman directly affects corporate strategy and contributes to major business decisions, such as a firm’s operational and financing policies (Jiang & Kim, Citation2015; Zhu et al., Citation2016). The ‘rice theory’ posits that an individualistic culture is more common in Northern than Southern China, whereas a collectivistic culture is more prevalent in Southern China due to historical differences in regional agricultural cultivation and production (Talhelm et al., Citation2014). Accordingly, we adopt a chairman’s native place of origin in Northern China as a proxy for chairman individualism and find that compared with their collectivistic counterparts, individualistic chairmen tend to choose a less flexible cost structure, which is defined as a larger proportion of fixed costs and smaller proportion of variable costs. Moreover, we find that the negative association between chairman individualism and flexibility of cost structure is less pronounced for state-owned enterprises (SOEs) than for non-SOEs, for firms whose boards of directors are more (vs. less) independent, and for firms with higher (vs. lower) financial leverage.

Our study contributes to the literature in two primary ways. First, our study contributes to the growing literature on firms’ cost structure decisions in response to risk. Research in this area focuses primarily on demand-side risk, such as demand uncertainty and customer concentration, from the perspective of the supply chain (Kallapur & Eldenburg, Citation2005; Banker et al., Citation2014; Holzhacker et al., Citation2015a, Citation2015b; Chang et al., Citation2017; Jiang et al., Citation2018). Aboody et al. (Citation2018) demonstrate that managers adjust firms’ cost structures in response to reductions in risk-taking incentives. In contrast, we show empirically that cost structure decisions are shaped by managers’ personal traits rather than by managerial incentives. We thus provide a potential avenue to explore the risk factors influencing firms’ cost management.

Second, our study contributes to cross-cultural studies, especially in the area of consequences of personal individualism (collectivism). Research mainly focuses on the effects of managers’ individualism (collectivism) on financial accounting and corporate finance policies (Brochet et al., Citation2019; Chui et al., Citation2010; Han et al., Citation2010; Kanagaretnam et al., Citation2011, Citation2014). We extend this research to management accounting by examining the association between chairman individualism and firms’ cost structure decisions. Country-level measures of culture (i.e. individualism vs. collectivism) may be subject to the confounding effects of institutional differences across countries in areas such as accounting rules, tax regulations and legal enforcement (Guiso et al., Citation2006). Consequently, researchers exploring culture and finance face the major challenge of measuring culture (i.e. individualism vs. collectivism) at the firm or individual level. Based on the rice theory (Talhelm et al., Citation2014), we use a chairman’s native place of origin in Northern China as the individual-level measure of chairman individualism to overcome the problems associated with a country-level measure of culture (i.e. individualism vs. collectivism), as China is ethnically and politically unified. Although many studies show that managers’ overconfidence can affect firms’ risk-taking and operational decisions (Galasso & Simcoe, Citation2011; Hayward & Hambrick, Citation1997; Malmendier & Tate, Citation2008), we believe that a manager’s individualism (collectivism) is an exogenous trait that affects their tendency towards overconfidence (Hofstede, Citation2001) and thus affects firms’ operational decisions.

2. Literature review and hypothesis development

Research in the field of cross-cultural psychology suggests that the dichotomy of individualism and collectivism is one of the most significant (Hofstede, Citation1980; Hofstede, Citation2001) and fruitful dimensions in the area of cultural differences (Heine, Citation2008). Specifically, individualism is characterised by self-orientation, autonomy and achievement, and people from individualistic cultures are likely to prioritise individual goals (Fiske et al., Citation1998; Singelis et al., Citation1995). In contrast, collectivism emphasises self-sacrifice, harmony and cooperation, and people from collectivistic cultures tend to pursue group goals even at the expense of their individual goals (Carpenter, Citation2000; Kulkarni et al., Citation2010).

Cross-country studies use the country-level individualism–collectivism index developed by Hofstede (Citation1980, Citation2001) and cross-country samples to investigate the effects of individualism and collectivism on investment and accounting decisions. For example, some studies examine the effects of investors’ individualism on stock price momentum and co-movement (Chui et al., Citation2010; Eun et al., Citation2015). Other studies investigate the effects of managers’ individualism on firms’ earnings management and information disclosure attributes (Brochet et al., Citation2019; Han et al., Citation2010). Using a cross-country sample of banks, Kanagaretnam et al. (Citation2011) demonstrate that banks in individualistic countries are more likely than those in collectivistic countries to use earnings management to meet or beat earnings in the prior year and to smooth earnings. In a study of banks, Kanagaretnam et al. (Citation2014) also document that individualistic culture is negatively associated with accounting conservatism but positively associated with risk-taking. Although these studies discussed above partly uncover the relationships between individualism and finance and accounting policies, the findings are vulnerable to the confounding effects of cross-country institutional differences in areas such as accounting rules, tax regulations and legal enforcement. To alleviate this vulnerability,Footnote5 we use individual-level individualism (collectivism) to examine the effect of chairman individualism (collectivism) on firms’ cost structure decisions in a within-country setting.

China provides an ideal within-country setting for an investigation of the effects of individualism and collectivism. Following Hofstede’s individualism–collectivism index (Hofstede, Citation1980, Citation2001), China generally has a collectivistic culture. However, this simple classification method does not consider regional cultural diversity in China, which covers a large geographic area and has a long history. The populations in geographic areas such as the Yellow River Basin and Yangtze River Basin are representatives of the distinctive cultural traits of Northern and Southern China, respectively. Despite acknowledgement of the differences in personal traits caused by cultural discrepancies between these regions of China, the cultural discrepancy between Northern and Southern China was first defined as the difference between collectivism and individualism in 2014, when Talhelm et al. (Citation2014) proposed the rice theory.

Fei (Citation1985) shows that because Chinese traditional culture is rooted in agriculture, Chinese people tend to have a strong sense of affiliation with the land. Similarly, the rice theory proposed by Talhelm et al. (Citation2014) notes that, from the perspective of irrigation, growing rice requires significant amounts of water, and coordination among neighbours is essential during the irrigation stage of rice farming. In contrast, wheat farming can be completed independently with very little help from neighbours because wheat demands minimum amount of water. Furthermore, rice farming is significantly more labour-intensive compared to wheat farming. Finally, harvesting rice requires more group effort than harvesting wheat. Due to these significant agricultural differences, people from the rice-farming regions have gradually developed collectivistic traits, whereas people from the wheat-farming areas have become individualistic over time. Across China, rice and wheat have been farmed primarily in southern and northern regions, respectively, for thousands of years,Footnote6 leading to long-term regional cultural traditions despite the abandonment of farming by most people in modern Chinese society. As Talhelm et al. (Citation2014) base their rice theory on evidence from a survey of 1,162 Han Chinese participants in six regions of China, we think that it is feasible to use the cultural differences between Northern and Southern China as a proxy for individualism vs. collectivism, given China’s ethnic and political unification. We therefore use this proxy to investigate the effect of chairman individualism on firms’ cost structure decisions.Footnote7

We focus on chairman individualism because the chairman plays the most important leadership role in a Chinese firm. Chinese listed companies are usually controlled by large shareholders, who can appoint a chairman of the board of directors to protect their own interests. Accordingly, chairmen of Chinese firms have greater power to set corporate policies than their counterparts in the U.S. and the U.K. As the conveners and moderators of board meetings, chairmen also control the agendas and tone of the meetings and thus influence firms’ major strategic and business decisions (Jiang & Kim, Citation2015; Zhu et al., Citation2016). Therefore, this institutional background (i.e. the chairman’s leadership role in a Chinese firm) enables us to investigate the effect of chairman individualism on firms’ cost structure decisions in China.

Research in the field of cross-cultural psychology suggests that individuals’ behaviours in adulthood are shaped by their cultural backgrounds, early experiences and family environments (Shweder, Citation1991; Triandis, Citation2001). As these influences affect corporate managers’ behaviours (Malmendier et al., Citation2011), we propose that an individualistic (vs. a collectivistic) chairman is more willing to take risk in pursuit of self-orientation, personal achievement and autonomy (Fiske et al., Citation1998; Singelis et al., Citation1995). In such circumstances, an individualistic chairman is likely to underestimate or even ignore the operational risk and possible damage to other relevant stakeholders’ interest caused by an increase in operating leverage; consequently, the chairman is likely to choose a larger proportion of fixed costs in anticipation of a marginal cost reduction due to economies of scale. Furthermore, chairman individualism may also lead to overconfidence (Hofstede, Citation2001), and research shows that an overconfident chairman tends to overestimate the firm’s future cash flow and underestimate the risk associated with operational decisions (Galasso & Simcoe, Citation2011; Hayward & Hambrick, Citation1997; Malmendier & Tate, Citation2008). Therefore, an individualistic chairman may underestimate the operational risk caused by a larger proportion of fixed costs and choose a less flexible cost structure. Based on the above arguments, we posit our first hypothesis as follows:

H1: Chairman individualism is negatively associated with flexibility of cost structure.

China and Chinese SOEs are typical examples of a collectivistic culture. Given the political function of SOEs, the chairmen of these firms are more committed to achieving social goals, such as employee welfare and social stability, than to achieving individual goals (Chen et al., Citation2011; Ke et al., Citation2012). This commitment reduces their incentives to undertake a higher level of operational risk for the sake of self-fulfilment. In addition, the chairmen of SOEs are usually appointed by the government and have implicit political roles (Fan et al., Citation2007; Cao et al., Citation2019). These chairmen are more likely to fulfill their corporate and social duties under the pressure of political promotion and thus maintain their reputations, leading to a higher degree of operational risk aversion. Therefore, we expect the unique characteristics of SOEs to mitigate the effect of chairman individualism on firms’ high-risk operational decisions, such that individualistic chairmen of SOEs tend to choose a more flexible cost structure to decrease their firms’ operational risk. In contrast, non-SOEs are less influenced by the collectivistic tradition; accordingly, chairman individualism should significantly influence these firms’ operational decisions such as choosing a larger proportion of fixed costs. Based on the above arguments, we posit our second hypothesis as follows:

H2: The negative association between chairman individualism and flexibility of cost structure is less pronounced in SOEs than in non-SOEs.

Compared with inside directors, independent outside directors are more alert to decision biases caused by chairmen’s personal traits. Practically, independent directors can correct these biases by proposing adjustments to compensation, personnel appointments or the removal of chairmen (Hayward & Hambrick, Citation1997; Malmendier & Tate, Citation2005). Consistent with these observations, studies based on samples of Chinese listed companies find that independent directors play a positive role in corporate governance through supervision and consulting (Chen & Xiang, Citation2017; Jiang et al., Citation2016; Liu et al., Citation2015; Ye et al., Citation2011). Therefore, individualistic chairmen’s risk-taking behaviours should be more heavily regulated when the firm’s board includes a higher (vs. lower) percentage of independent directors, and this regulation should motivate the chairmen to choose a more flexible cost structure. Based on the above arguments, we posit our third hypothesis as follows:

H3: The negative association between chairman individualism and flexibility of cost structure is less pronounced in firms whose boards of directors are more (vs. less) independent.

According to the fundamental principle of corporate finance, corporate risk primarily include financial risk and operational risk, which are respectively characterised by high financial leverage and high operating leverage. As simultaneously high levels of financial and operating leverage generally cause an exponential increase in overall risk through the multiplier effect, chairmen must balance these two types of leverage to control firms’ overall risk. Therefore, when a firm’s financial leverage is higher, an individualistic chairman is strongly incentivised to choose a more flexible cost structure, i.e. lower operating leverage, to control the firm’s overall risk. Based on the above arguments, we posit our fourth hypothesis as follows:

H4: The negative association between chairman individualism and flexibility of cost structure is less pronounced when a firm’s financial leverage is higher (vs. lower).

3. Research design

3.1. Sample selection

Our sample consists of Chinese listed companies during the 2003–2017 period. Chairmen’s native places of origin data, corporate financial data and corporate government data are obtained from the China Stock Market and Accounting Research (CSMAR) database.Footnote8

To construct our sample, we first exclude firms in the financial sector. Second, we exclude firm–year observations with missing financial data or information about firms’ ownership or chairmen’s native places of origin. Third, we exclude firms whose chairmen’s native places of origin are in Tibet, Inner Mongolia and Xinjiang, as these regions are typically inhabited by people of nomadic cultures, who are different from people of Han ethnicity and culture in many respects, including language and religion. Fourth, we exclude firms whose chairmen’s native places of origin are in Hong Kong, Macao and Taiwan, as these three regions differ from China's Mainland in ethnicity, politics, culture and religion. Finally, we exclude firm-year observations with debt-to-asset ratios greater than 1. The above exclusions result in a final sample of 12,511 firm–year observations. All of the variables are winsorised at the 1% and 99% levels to control for the potential impact of outliers.

3.2. Variable measurement of chairman individualism

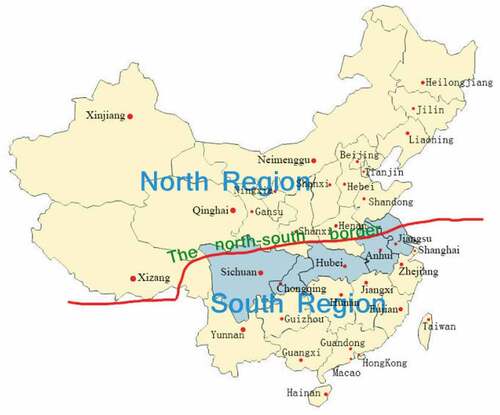

We use a chairman’s native place of origin in Northern (Southern) China as a proxy for personal individualism (collectivism). Individualism is a dummy variable that equals 1 if a chairman is from Northern China and 0 if they are from Southern China.

shows the boundary between Northern and Southern China. In our sample, Northern China includes the provinces of Qinghai, Beijing, Ningxia, Jilin, Gansu, Shandong, Shanxi, Shaanxi, Hebei, Heilongjiang, Liaoning, Henan and Tianjin. Southern China includes the provinces of Shanghai, Jiangxi, Zhejiang, Guangdong, Fujian, Hunan, Hainan, Hubei, Sichuan, Chongqing, Jiangsu, Guangxi, Anhui, Guizhou and Yunnan.

We measure individualism (collectivism) at the individual level using a chairman’s native place of origin for the following reasons.Footnote9 First, compared with previous studies based on country-level cultural characteristics (i.e. individualism vs. collectivism), our approach mitigates the confounding effects of national or regional institutional differences such as accounting rules, tax regulations and legal enforcement (Guiso et al., Citation2006). Second, the distinct north–south discrepancy (i.e. individualism vs. collectivism) that has arisen in China due to historical differences in agricultural cultivation has lasted for thousands of years. These cultural differences have had a steady and persistent influence on Chinese people (Talhelm et al., Citation2014). Third, culture is difficult to change and devalue; accordingly, it is considered a ‘given’ trait held by an individual (Guiso et al., Citation2006).Footnote10

3.3. Model specification

Our main hypothesis (H1) predicts a negative association between chairman individualism and flexibility of cost structure. Following the literature (Anderson et al., Citation2003; Banker et al., Citation2014; Chang et al., Citation2017), we measure flexibility of cost structure using cost elasticity, which we capture using the following log-linear model:

where represents the log-change in the cost of goods sold (COGS) for firm i from year t-1 to year t;

represents the log-change in sales revenue for firm i from year t-1 to year t; Individualismi,t is the chairman individualism measure, as defined above, for firm i in year t. We use the COGS in our main analyses because chairmen are usually involved in firms’ strategic and other major business decisions that affect operating costs, such as investing in fixed assets and hiring employees; these costs are most likely included in the COGS rather than in selling, general and administrative (SG&A) expenses (Anderson & Dekker, Citation2009a, Citation2009b).

The coefficient β1 captures the base cost elasticity when the values of Individualismi,t and other control variables are zero. This coefficient reflects the percentage change in COGS per each 1% change in sales revenue (Anderson et al., Citation2003). A small value of β1 implies a weak association between changes in sales revenue and changes in COGS, indicating a less flexible cost structure. The coefficient β2 on the interaction term *Individualismi,t captures the effect of chairman individualism on cost elasticity. A positive (negative) β2 indicates that chairman individualism increases (decreases) cost elasticity. Therefore, our main hypothesis (H1) predicts a negative β2.

Following the literature (Anderson et al., Citation2003; Banker et al., Citation2014; Chang et al., Citation2017), we include the following control variables in our regression models: firm ownership (Ownership), GDP growth (GDPG), asset intensity (AI), employee intensity (EI), demand uncertainty (Uncertainty), firm size (Size) and liability-to-asset ratio (Leverage). Furthermore, we include the chairman’s age (Age), tenure (Tenure) and gender (Gender), the independence of the board of directors (Independent) and whether a chairman holds the position of CEO (Duality) to account for the associations of chairman individualism with the chairman’s characteristics and corporate governance factors. In addition, we control for firm and year fixed effects to address concern about the endogeneity of chairman individualism (Adams & Ferreira, Citation2009; Firth et al., Citation2015). provides the definitions of all of the variables.

Table 1. Definitions of variables.

4. Empirical results

4.1. Descriptive statistics

presents the descriptive statistics for the variables in our study. The average value of Individualism is 0.38, indicating that chairmen whose native places of origin are in Northern China account for about 38% of our sample observations. The average Ownership value is 0.51, indicating that SOEs account for around 51% of our sample observations. The average Leverage is 0.48. In addition, the average Age in our sample is approximately 52 years, and the average Tenure is 62 months. On average, male chairmen (Gender) account for 96% of our sample observations. Independent directors (Independent) account for 37% of all members of boards of directors, and 19% of chairmen hold CEO positions (Duality).

Table 2. Descriptive statistics.

4.2. Chairman individualism and flexibility of cost structure

4.2.1. Test of H1

reports the estimations for our regression model of the association between chairman individualism and cost elasticity. As shown in column (1), we find that β1 is significantly positive (β = 1.575, t = 10.54), indicating a positive association between the change in COGS and the change in sales revenue in Chinese listed companies. Consistent with H1, we find that β2 is significantly negative (β = −0.023, t = −2.34). The results suggest that an individualistic (vs. a collectivistic) chairman is more likely to take risk or be overconfident and consequently tends to choose a less flexible cost structure (i.e. a larger proportion of fixed costs).

Table 3. Regression results for H1.

Following Talhelm et al. (Citation2014), we create a ranked categorical measure of chairman individualism as follows. First, we use agriculture statistics during 1988, which are published by the National Bureau of Statistics of China,Footnote11 to calculate the ratio of cultivated land in each province used for wheat farming to that used for rice farming. As we intend to assess the crops grown historically in different regions, without the influence of advanced irrigation and mechanisation, we use cultivated land statistics for each province, rather than yield statistics. Second, we rank the ratios of cultivated land for wheat vs. rice farming and sort them into 10 groups: the group with the highest ratio is classified as 1, while the group with the lowest ratio is classified as 0.1, and other groups take values within the range of 0.1 to 1 according to their ranks. Third, we match chairmen in corresponding groups by province, such that more individualistic chairmen are placed in higher ranked groups. The results are presented in column (2) of . After using this alternative measure of chairman individualism, we find that β2 is significantly negative (β = −0.050, t = −2.79), consistent with the results in column (1). We also calculate the ratio of cultivated land in each province used for wheat farming to all land cultivated for crops and create ranked groups as described above. We obtain similar results that support H1, as shown in column (3) of .

An alternative explanation pertaining to the effect of culture at individual level is that a chairman whose native place of origin is in Northern (Southern) China is likely to work in a firm located in Northern (Southern) China, such that the influence of regional-level culture remains steady. To rule out this alternative explanation, we re-examine the regression using a region fixed effect model. The results are presented in column (4) of . We find that β2 is significantly negative (β = −0.024, t = −2.71), consistent with our earlier findings, and thus our results remain unchanged.

We also rerun our main regression model using data on chairmen’s birthplaces from the CSMAR database. Using the definition of Individualism provided in Section 3.2,Footnote12 we find that β2 is significantly negative (β = −0.023, t = −2.30), as shown in column (5) of . Taken together, these results suggest that our H1 is robust to a battery of alternative checks.

4.2.2. Robustness check

Next, we conduct a change analysis. Specifically, we first choose a sample of firms whose chairmen were replaced and construct the variable ΔIndividualism, which equals 1 if a collectivistic chairman is replaced by an individualistic chairman, −1 if the reverse change occurs or 0 if replacement of the chairman does not lead to a change between individualism and collectivism. Second, following Irvine et al. (Citation2016), we measure firm-specific cost elasticity (CE) by and test whether a change in cost elasticity is associated with a change in chairman individualism. Third, we expect that the incoming chairman will take some time to adjust the firm’s cost structure; therefore, we regress the change in cost elasticity (∆CEt+1) on the lagged change in chairman individualism (∆Individualismt). The results are presented in .Footnote13 We find that the coefficient on the lagged change in chairman individualism is significantly negative, suggesting that an increase in individualism due to chairman change leads to a decrease in a firm’s cost elasticity.

Table 4. Change analysis.

We re-examine our H1 using a sample of Chinese listed companies in the manufacturing industry, which account for over 60% of our full sample, as strategic cost management is especially important for manufacturing firms (Chang et al., Citation2017). The results are presented in , which demonstrates that our H1 holds for all of the analyses except that shown in column (5).

Table 5. Regression results for H1-Manufacturing industry sample.

The literature shows that chairmen play an important leadership role in board meetings, where they have the ultimate power to set the tone of meetings and thus directly affect firms’ strategic and major business decisions (Jiang & Kim, Citation2015; Zhu et al., Citation2016). Undeniably, CEOs also strongly influence firms’ strategic and major business decisions. Therefore, we use a CEO’s native place of origin in Northern (Southern) China as a proxy for individualism (collectivism) and examine the effect of CEO individualism on firms’ cost elasticity. Furthermore, we perform the same alternative checks for CEO individualism as described for chairman individualism in Section 4.2.1. The results are shown in .Footnote14 We find that although β2 is still negative, the effect of CEO individualism on cost elasticity is less significantly negative than that of chairman individualism. The results suggest that individualistic CEOs have a smaller impact on firms’ cost structure decisions than individualistic chairmen do.

Table 6. Regression results for H1-CEO Sample.

4.2.3. Tests of H2–H4

H2 predicts that the negative association between chairman individualism and flexibility of cost structure will be less pronounced in SOEs than in non-SOEs. presents the regression results for H2. In the subsample analysis, columns (1) and (2) respectively show that β2 is significantly negative (β = −0.032, t = −1.87) for non-SOEs but nonsignificant (β = 0.001, t = 0.10) for SOEs,Footnote15 which is consistent with H2. We further divide SOEs into those administrated by the central government and by local governments and find that β2 remains nonsignificant (β = 0.015, t = 0.85 and β = 0.000, t = 0.03, respectively), as shown in columns (3) and (4). The results suggest in SOEs, the collectivistic culture and political promotion pressure mitigate the effect of chairman individualism on firms’ cost structure decisions. Therefore, individualistic chairmen of SOEs are likely to choose a more flexible cost structure, whereas individualistic chairmen of non-SOEs are likely to choose a less flexible cost structure because their firms are less influenced by collectivism.

Table 7. Regression results for H2.

H3 predicts that the negative association between chairman individualism and flexibility of cost structure will be less pronounced in firms whose boards of directors are more (vs. less) independent. We divide the full sample into High_Indepen and Low_Indepen subsamples according to the yearly median value of Independent and examine the effect of chairman individualism on firms’ cost elasticity. presents the regression results for H3. The results of the subsample analysis are presented in columns (1) and (2), which respectively show that β2 is nonsignificant (β = −0.012, t = −0.74) for the High_Indepen subsample but significantly negative (β = −0.047, t = −3.62) for the Low_Indepen subsample, which is consistent with H3. The results imply in firms with more independent directors, individualistic chairmen’s risk-taking behaviours attract attention from the independent directors, who can impose restrictions on firms’ cost structure decisions.

Table 8. Regression results for H3.

H4 predicts that the negative association between chairman individualism and flexibility of cost structure will be less pronounced when firms’ financial leverage is higher (vs. lower). We divide the full sample into High_Lev and Low_Lev subsamples according to the yearly median value of Leverage and examine the effect of chairman individualism on firms’ cost elasticity. presents the regression results for H4. Columns (1) and (2) show that β2 is nonsignificant (β = −0.006, t = −0.51) for the High_Lev subsample but significantly negative (β = −0.032, t = −1.85) for the Low_Lev sample, which is consistent with H4. The results suggest in a firm with higher financial leverage, an individualistic chairman is highly incentivised to control the firm’s overall risk by choosing a more flexible cost structure (i.e. lower operating leverage).

Table 9. Regression results for H4.

4.2.4. Additional tests

We perform the following tests to further validate our results. First, we delete firm–year observations wherein chairmen also hold CEO positions.Footnote16 Second, we construct an alternative continuous variable of chairman individualism which is the percentage of cultivated land used for rice farming in the province that corresponds to a chairman’s native place of origin, and rerun our regressions. Third, we exclude firm-year observations wherein the chairmen’s native places of origin are in Sichuan, Chongqing, Anhui, Hubei, Jiangsu and Guizhou because these provinces lie along the boundary between Northern and Southern China. Fourth, we control for the chairman’s education level using the following scores: 1 = associate’s degree, 2 = bachelor’s degree, 3 = master’s degree and 4 = doctor’s degree. As the CSMAR database does not contain complete information on all chairmen’s education levels, we assume chairmen with lower levels of education are less willing to disclose this information; therefore, we set 0 = missing education level. Last, we control for a chairman’s compensation. As not all compensation is paid by the listed company, we control for both the payment of chairman’s compensation by the listed company and the amount of cash compensation. Our results remain robust after conducting these additional tests.

5. Conclusion

The increasing complexity of supply chain management may expose firms to substantial risk. Accordingly, a growing body of literature in the field of management accounting investigates firms’ cost structure decisions in response to risk. However, the literature primarily focuses on demand-side risk such as demand uncertainty and customer concentration. Few studies pay attention to risk related to managers’ personal traits and firms’ incentive systems (Aboody et al., Citation2018). Investigation of firms’ cost structure decisions from the perspective of manager-side risk has important theoretical and practical implications. Accordingly, we examine the effect of chairman individualism on firms’ cost structure decisions in a sample of Chinese listed companies, using a chairman’s native place of origin in Northern (Southern) China as a proxy for individualism (collectivism). Our results show that individualistic chairmen tend to choose a less flexible cost structure. Furthermore, the negative association between chairman individualism and flexibility of cost structure is less pronounced for SOEs (vs. non-SOEs), firms with more (vs. less) independent boards of directors and firms with higher (vs. lower) financial leverage.

Our study presents both theoretical contributions and practical implications. It contributes to the growing literature on firms’ cost structure decisions in response to risk and extends the literature on the effects of individual-level individualism (collectivism) on corporate finance and financial accounting decisions to the study of management accounting decisions, especially strategic cost management. Our study also provides insights into firms’ strategic cost management practices. It changes the paradigm wherein most knowledge on structural cost management comes from fields outside accounting, and it provides practical guidance for firms’ managers, accountants and the government. In particular, our findings may assist the Ministry of Finance in improving and implementing the ‘Fundamental Guidelines for Management Accounting’. Overall, our study provides empirical evidence on the importance of managers’ leadership on Chinese firms’ strategic cost management, which can help firms to achieve transformation and sustainable development.

Our study has two main limitations. First, regarding the challenge of measuring culture (i.e. individualism vs. collectivism) at the firm or individual level, although this paper tries to use a chairman’s native place of origin in Northern (Southern) China as a proxy for chairman individualism (collectivism), we still cannot fully rule out the confounding effects of the discrepancy between Northern and Southern China. Future studies can explore more direct and accurate measures. Second, our paper only examines the effect of chairman individualism on firms’ cost structure decisions from the perspective of structural cost management, future research could also investigate how chairman individualism affects firms’ executional cost management, such as corporate strategy implementation and performance.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Notes

1 Statistics show that in manufacturing industries, the value of purchased materials and services has grown from 20% to 56% of the selling price of finished goods over the past 50 years (Anderson & Dekker, Citation2009a)........

2 Executional cost management is concerned with whether a firm is on an efficient frontier for a given production function (i.e. whether a firm’s performance is profitable).

3 Cost structure and cost stickiness are related but distinct concepts. Both concepts can be classified as cost behaviour, and both represent the association between a firm’s costs and its sales revenue. However, they differ in that cost structure is characterised by a proportion of both variable and fixed costs (e.g. Banker et al., Citation2014), while cost stickiness measures the asymmetrical change in costs in response to increases or decreases in a firm’s sales revenues (e.g. Anderson et al., Citation2003). Several researchers examine the factors affecting cost stickiness in China, including Jiang et al. (Citation2015), Liang et al. (Citation2015), Mao et al. (Citation2015), Jiang et al. (Citation2016), Jiang et al. (Citation2017), Liu et al. (Citation2017), Wang & Gao (Citation2017), Zhang et al. (Citation2019), and Zhou et al. (Citation2019).

4 Culture can be defined as the customary beliefs and values transmitted in fairly unchanged forms between generations within ethnic, religious, and social groups (Guiso et al., Citation2006).

5 To address the concern of institutional differences across countries, studies increasingly examine the effects of cultural differences within a country. For example, Li et al. (Citation2013) investigate the effect of a firm’s country of origin on capital structure in Chinese business evironment, while Nguyen et al. (Citation2018) investigate the effect of CEOs’ cultural heritage on firms’ operational decisions in a U.S. sample.

6 For example, data published by the National Bureau of Statistics of China indicate that in our sample period, the average rice production yield in Southern Chinese provinces was about 65% of the total grain yield, compared with only about 10% in Northern Chinese provinces.

7 In China, people of Han Chinese ethnicity comprise more than 90% of the total population. In the most recent millennium, regions characterised by wheat and rice farming have been governed by the same dynasties, which alleviates concern about the omission of variables related to ethnicity and political factors in most cross-cultural studies of Eastern and Western countries.

8 Only some firms disclose their chairman's native places of origin. Accordingly, the CSMAR database provides this information for around 50% of the chairmen of all Chinese listed companies during our sample period.

9 Jiang et al. (Citation2019) apply a measure of individual-level collectivism (individualism) that indicates whether a chairman’s native place of origin is in Southern (Northern) China to a sample of Chinese listed companies, and they document that the compensation gap in a firm run by a chairman from a collectivistic culture tends to be smaller than that of a firm run by a chairman from an individualistic culture. Fan et al. (Citation2022) use the percentage of cultivated land in each province devoted to rice paddies as a proxy for collectivist culture in an analysis of the founders of Chinese private-sector firms and find that a collectivist culture has a significant effect on the ownership structure of a family firm. In addition, Liu et al. (Citation2019) provide evidence that supports the ‘rice theory’ based on a large-scale survey of Chinese interviewees.

10 We concede that China’s traditional agricultural culture has a weak influence on people in urban areas in modern society, but the measurement noise caused by the phenomenon will bias against finding any results in our analyses.

11 Note that 1988 is the earliest year for which agriculture statistics are available from the National Bureau of Statistics of China.

12 The sample size decreases to 12,494 observations after we delete 17 firm-year observations for chairmen whose birthplaces are in Tibet, Inner Mongolia or Xinjiang.

13 Our sample period includes 4,157 firm-year observations involving changes in chairmen but only 578 observations that disclose complete information about the chairmen’s native places of origin before and after the changes in chairmen. Finally, our sample size for the change model decreases to 499 observations after deleting firm-year observations with missing values for control variables.

14 In the regression model, we also control for CEO age (Age), tenure (Tenure) and gender (Gender).

15 The results of a test of differences in coefficients between subsamples show that β2 is significantly different between SOEs and non-SOEs. In the following subsample difference tests for H3 and H4, which test the moderating effects of board independence and financial leverage, respectively, we obtain similar results, which are not described below.

16 The dual position of chairman and CEO may increase a chairman’s overconfidence and thus substitute for the effect of chairman individualism (collectivism). Nevertheless, we do not find a significantly negative association between chairman individualism and cost elasticity when a chairman holds a CEO position.

References

- Aberdeen Group. (2005). Center-Led procurement-organizing resources and technology for sustained supply value. Boston.

- Abernethy, M.A., & Wallis, M. (2019). Critique on the “manager effects” research and implications for management accounting research. Journal of Management Accounting Research, 31(1), 3–40. https://doi.org/10.2308/jmar-52030

- Aboody, D., Levi, S., & Weiss, D. (2018). Managerial incentives, options, and cost-structure choices. Review of Accounting Studies, 23(2), 422–451. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11142-017-9432-0

- Adams, R.B., & Ferreira, D. (2009). Women in the boardroom and their impact on governance and performance. Journal of Financial Economics, 94(2), 291–309. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfineco.2008.10.007

- Alesina, A., & Giuliano, P. (2015). Culture and institutions. Journal of Economic Literature, 53(4), 898–944. https://doi.org/10.1257/jel.53.4.898

- Anderson, M.C., Banker, R.D., & Janakiraman, S.N. (2003). Are selling, general, and administrative costs “sticky”? Journal of Accounting Research, 41(1), 47–63. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-679X.00095

- Anderson, S.W., & Dekker, H.C. (2009a). Strategic cost management in supply chains, part 1: Structural cost management. Accounting Horizons, 23(2), 201–220. https://doi.org/10.2308/acch.2009.23.2.201

- Anderson, S.W., & Dekker, H.C. (2009b). Strategic cost management in supply chains, part 2: Executional cost management. Accounting Horizons, 23(3), 289–305. https://doi.org/10.2308/acch.2009.23.3.289

- Banker, R.D., Byzalov, D., & Plehn-Dujowich, J.M. (2014). Demand uncertainty and cost behavior. The Accounting Review, 89(3), 839–865. https://doi.org/10.2308/accr-50661

- Becker, G. (1996). Preferences and values. Harvard University Press.

- Bennedsen, M., Nielsen, K.M., Pérez-González, F., & Wolfenzon, D. (2007). Inside the family firm: The role of families in succession decisions and performance. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 122(2), 647–691. https://doi.org/10.1162/qjec.122.2.647

- Bertrand, M., & Schoar, A. (2003). Managing with style: The effect of managers on firm policies. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 118(4), 1169–1208. https://doi.org/10.1162/003355303322552775

- Brochet, F., Miller, G.S., Naranjo, P., & Yu, G. (2019). Managers’ cultural background and disclosure attributes. The Accounting Review, 94(3), 57–86. https://doi.org/10.2308/accr-52290

- Cao, X., Lemmon, M., Pan, X., Qian, M., & Tian, G. (2019). Political promotion, CEO incentives, and the relationship between pay and performance. Management Science, 65(7), 2947–2965. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.2017.2966

- Carpenter, S. (2000). Effects of cultural tightness and collectivism on self-concept and causal attributions. Cross-Cultural Research, 34(1), 38–56. https://doi.org/10.1177/106939710003400103

- Chang, H., Hall, C.M., & Paz, M. (2017). Customer concentration and cost structure. Working paper, https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?Abstract_id=2482777.

- Chen, J., Ezzamel, M., & Cai, Z. (2011). Managerial power theory, tournament theory, and executive pay in China. Journal of Corporate Finance, 17(4), 1176–1199. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcorpfin.2011.04.008

- Chen, D., & Xiang, J. (2017). Is it reasonable for independent directors to be re-elected for only six years? Evidence from Chinese listed companies. Management World, (5), 144–157. (In Chinese). https://doi.org/10.19744/j.cnki.11-1235/f.2017.05.013

- Chui, A.C., Titman, S., & Wei, K.J. (2010). Individualism and momentum around the world. The Journal of Finance, 65(1), 361–392. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6261.2009.01532.x

- Cronqvist, H., Makhija, A.K., & Yonker, S.E. (2012). Behavioral consistency in corporate finance: CEO personal and corporate leverage. Journal of Financial Economics, 103(1), 20–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfineco.2011.08.005

- Eun, C.S., Wang, L., & Xiao, S.C. (2015). Culture and R2. Journal of Financial Economics, 115(2), 283–303. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfineco.2014.09.003

- Fan, J.P., Gu, Q.K., & Yu, X. (2022). Collectivist cultures and the emergence of family firms, The Journal of Law and Economics, 65(S1), S293–S325. forthcoming. https://ssrn.com/abstract=3839978.

- Fan, J.P., Wong, T.J., & Zhang, T. (2007). Politically connected CEOs, corporate governance, and Post-IPO performance of China’s newly partially privatized firms. Journal of Financial Economics, 84(2), 330–357. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfineco.2006.03.008

- Fei, X. (1985). From the Soil - The Foundations of Chinese Society. SDX Joint Publishing Company.

- Firth, M., Leung, T.Y., Rui, O.M., & Na, C. (2015). Relative pay and its effects on firm efficiency in a transitional economy. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 110, 59–77. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jebo.2014.12.001

- Fiske, A.P., Kitayama, S., Markus, H.R., & Nisbett, R.E. (1998). The cultural matrix of social psychology. McGraw-Hill.

- Galasso, A., & Simcoe, T.S. (2011). CEO overconfidence and innovation. Management Science, 57(8), 1469–1484. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.1110.1374

- Guiso, L., Sapienza, P., & Zingales, L. (2006). Does culture affect economic outcomes? Journal of Economic Perspectives, 20(2), 23–48. https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.20.2.23

- Han, S., Kang, T., Salter, S., & Yoo, Y.K. (2010). A cross-country study on the effects of national culture on earnings management. Journal of International Business Studies, 41(1), 123–141. https://doi.org/10.1057/jibs.2008.78

- Hayward, M.L., & Hambrick, D.C. (1997). Explaining the premiums paid for large acquisitions: Evidence of CEO hubris. Administrative Science Quarterly, 42(1), 103–127. https://doi.org/10.2307/2393810

- Heine, S.J. (2008). Cultural psychology. W.W. Norton & Company.

- Hofstede, G. (1980). Culture’s consequences. Sage Publications.

- Hofstede, G. (2001). Culture’s consequences: Comparing values, behaviors, institutions and organizations across nations. Sage Publications.

- Holzhacker, M., Krishnan, R., & Mahlendorf, M.D. (2015a). The impact of changes in regulation on cost behavior. Contemporary Accounting Research, 32(2), 534–566. https://doi.org/10.1111/1911-3846.12082

- Holzhacker, M., Krishnan, R., & Mahlendorf, M.D. (2015b). Unraveling the black box of cost behavior: An empirical investigation of risk drivers, managerial resource procurement, and cost elasticity. The Accounting Review, 90(6), 2305–2335. https://doi.org/10.2308/accr-51092

- Irvine, P.J., Park, S.S., & Yıldızhan, Ç. (2016). Customer-Base Concentration, Profitability, and the Relationship Life Cycle. The Accounting Review, 91(3), 883–906. https://doi.org/10.2308/accr-51246

- Jiang, W., Di, L., & Yao, W. (2017). Customer concentration and firm cost stickiness: Evidence from Chinese listed companies in manufacturing industry. Journal of Financial Research, (9), 192–206. https://kns.cnki.net

- Jiang, W., Hu, Y., & Zeng, Y. (2015). Financial constraints and cost stickiness: Evidence from Chinese industrial firms. Journal of Financial Research, (10), 133–147. https://kns.cnki.net

- Jiang, F., & Kim, K.A. (2015). Corporate governance in China: A modern perspective. Journal of Corporate Finance, 32, 190–216. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcorpfin.2014.10.010

- Jiang, W., Lin, B., Liu, Y., & Xu, Y. (2019). Chairperson collectivism and the compensation gap between managers and employees: Evidence from China. Corporate Governance: An International Review, 27(4), 261–282. https://doi.org/10.1111/corg.12278

- Jiang, W., Sun, Y., & Hu, Y. (2018). Customer concentration and cost structure decisions: Empirical evidence from Chinese Relation-oriented business environment. Accounting Research, (11), 70–76. https://kns.cnki.net

- Jiang, W., Wan, H., & Zhao, S. (2016). Reputation concerns of independent directors: Evidence from individual director voting. The Review of Financial Studies, 29(3), 655–696. https://doi.org/10.1093/rfs/hhv125

- Jiang, W., Yao, W., & Hu, Y. (2016). The enforcement of the Minimum Wage Policy in China and firm cost stickiness. China Journal of Accounting Studies, 4(3), 339–355. https://doi.org/10.1080/21697213.2016.1218631

- Kallapur, S., & Eldenburg, L. (2005). Uncertainty, real options, and cost behavior: Evidence from Washington state hospitals. Journal of Accounting Research, 43(5), 735–752. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-679X.2005.00188.x

- Kanagaretnam, K., Lim, C.Y., & Lobo, G.J. (2011). Effects of national culture on earnings quality of banks. Journal of International Business Studies, 42(6), 853–874. https://doi.org/10.1057/jibs.2011.26

- Kanagaretnam, K., Lim, C.Y., & Lobo, G.J. (2014). Influence of national culture on accounting conservatism and risk-taking in the banking industry. The Accounting Review, 89(3), 1115–1149. https://doi.org/10.2308/accr-50682

- Ke, B., Rui, O., & Yu, W. (2012). Hong Kong stock listing and the sensitivity of managerial compensation to firm performance in state-controlled Chinese firms. Review of Accounting Studies, 17(1), 166–188. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11142-011-9169-0

- Kim, J.B., Wang, Z., & Zhang, L. (2016). CEO overconfidence and stock price crash risk. Contemporary Accounting Research, 33(4), 1720–1749. https://doi.org/10.1111/1911-3846.12217

- Krause, R., Semadeni, M., & Withers, M.C. (2016). That special someone: When the board views its chair as a resource. Strategic Management Journal, 37(9), 1990–2002. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.2444

- Kulkarni, S.P., Hudson, T., Ramamoorthy, N., Marchev, A., Georgieva-Kondakova, P., & Gorskov, V. (2010). Dimensions of individualism-collectivism: A comparative study of five cultures. Current Issues of Business & Law, 5(1), 93–109. https://doi.org/10.5200/1822-9530.2010.03

- Liang, S., Chen, D., & Hu, X. (2015). External auditor types and the cost stickiness of listed companies. Accounting Research, (2), 79–86. https://kns.cnki.net

- Li, K., Griffin, D., Yue, H., & Zhao, L. (2013). How does culture influence corporate risk-taking? Journal of Corporate Finance, 23, 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcorpfin.2013.07.008

- Liu, C., Li, S., & Sun, L. (2015). Do independent directors have the consulting function? An empirical study on the function of independent directors in strange land. Management World, (3), 124–136. (In Chinese). https://doi.org/10.19744/j.cnki.11-1235/f.2015.03.012

- Liu, S.S., Morris, M.W., Talhelm, T., & Yang, Q. (2019). Ingroup vigilance in collectivistic cultures. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 116(29), 14538–14546. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1817588116

- Liu, H., Qi, Y., & Wang, H. (2017). On the cost stickiness difference between companies with different layers in pyramidal business group. Accounting Research, (7), 82–88. https://kns.cnki.net

- Malmendier, U., & Tate, G. (2005). CEO overconfidence and corporate investment. The Journal of Finance, 60(6), 2661–2700. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6261.2011.01685.x

- Malmendier, U., & Tate, G. (2008). Who makes acquisitions? CEO overconfidence and the market’s reaction. Journal of Financial Economics, 89(1), 20–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfineco.2007.07.002

- Malmendier, U., Tate, G., & Yan, J. (2011). Overconfidence and early‐life experiences: The effect of managerial traits on corporate financial policies. The Journal of Finance, 66(5), 1687–1733. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6261.2011.01685.x

- Mao, H., Li, Z., & Cheng, J. (2015). The effect of non-economic factors on asymmetric cost behavior: Evidence from Chinese listed companies. Naikai Management Review, (6), 136–145. https://kns.cnki.net

- Nguyen, D.D., Hagendorff, J., & Eshraghi, A. (2018). Does a CEO’s cultural heritage affect performance under competitive pressure? The Review of Financial Studies, 31(1), 97–141. https://doi.org/10.1093/rfs/hhx046

- Shweder, R.A. (1991). Thinking through cultures: Expeditions in cultural psychology. Harvard University Press.

- Singelis, T.M., Triandis, H.C., Bhawuk, D.P., & Gelfand, M.J. (1995). Horizontal and vertical dimensions of individualism and collectivism: A theoretical and measurement refinement. Cross-Cultural Research, 29(3), 240–275. https://doi.org/10.1177/106939719502900302

- Talhelm, T., Zhang, X., Oishi, S., Shimin, C., Duan, D., Lan, X., & Kitayama, S. (2014). Large-scale psychological differences within China explained by rice versus wheat agriculture. Science, 344(6184), 603–608. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1246850

- Triandis, H.C. (2001). Individualism‐collectivism and personality. Journal of Personality, 69(6), 907–924. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-6494.696169

- Wang, X., & Gao, K. (2017). Customer relationship and cost stickiness: Hold-up or cooperation. Naikai Management Review, (1), 132–142. https://kns.cnki.net

- Withers, M.C., & Fitza, M.A. (2017). Do board chairs matter? The influence of board chairs on firm performance. Strategic Management Journal, 38(6), 1343–1355. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.2587

- Ye, K., Zhu, J., Lu, Z., & Zhang, R. (2011). The Independence of independent directors: Evidence from board voting behavior. Economic Research Journal, (1), 126–139. https://kns.cnki.net

- Zhang, L., Li, J., Zhang, H., & Wang, H. (2019). Can managerial ability restrain company’s cost stickiness? Accounting Research, (3), 71–77. https://kns.cnki.net

- Zhou, L., Liu, H., & Zhang, H. (2019). How do former CEO directors affect corporate resource adjustment? Journal of Financial Research, (2), 169–187. https://kns.cnki.net

- Zhu, J., Ye, K., Tucker, J.W., & Chan, K.J.C. (2016). Board hierarchy, independent directors, and firm value: Evidence from China. Journal of Corporate Finance, 41, 262–279. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcorpfin.2016.09.009