ABSTRACT

This paper examines news media coverage on autism, a public health issue in Vietnam. Computational corpus analysis and framing analysis of Vietnamese digital news media of over 580,000 words are deemed useful methods for big data analysis. The language patterns, extracted by WordSmith software, suggest autism is framed primarily as a medical problem and a family issue, not a matter of social policy or an aspect of human diversity. Noticeably, individuals with autism are expected to integrate to fit in with the community, not the other way around, where the society acts as an agent to accommodate autism diversity within an inclusive environment. The study finds the under-represented voices of individuals with autism and family actors, and the dominant voices of healthcare, education, and other professionals, along with the absence of government authorities in the media corpus.

Introduction

To be able to systematically subtract language patterns that suggest broad frames in a big digitalised database is important for media and communication studies, especially when they focus on critical and sometimes urgent social, political, or public health issues. Using computational corpus analysis in the conceptual framework of framing theory, this study examines how the digital news media in Vietnam frame autism and embed problematic ideologies.

The existing literature on the media representation of autism is anchored mainly in the United States, United Kingdom, and Australia and a couple of studies from China, dominantly with manual content and framing analysis. This research is the first to use a computational corpus analysis to extract frames from digital media coverage in this subject matter. It adds a specific Vietnamese perspective to the Western-centric scholarly literature on this critical public health topic.

Given that Vietnam remains an authoritarian political structure, monopolistically ruled by the Communist Party, media practice is politically regulated in an economic system that selectively adopts neoliberal logics (Thiem, Citation2016). The Party State takes advantage of the capitalist rationality but holds on to the ownership of media and other critical means of production and infrastructure (Thiem, Citation2016), in a longstanding Confucianism social and cultural context. Media outlets are, on the one hand, politically controlled but, on the other hand, increasingly commercialised with reduced or zero financial subsidy from the state (McKinley, Citation2008). Due to commercialisation or the ruthless logic of a neoliberalised economic system that constantly pushed for profits (Fenton, Citation2011), journalists were driven to seek out sensational news and viewership, rather than working with a strong normative sense of public interest (Nguyen, Citation2013). Media coverage in Vietnam can be paid for by public relation practitioners or service providers (Doan & Bilowol, Citation2014), enabling those who have the access and resources to reach out to the media to dominate the representation of any given topic (Hall, Clarke, Critcher, Jefferson, & Roberts, Citation1978).

This paper will start by reviewing the global literature on media representation of autism to set the background for the contribution of the study at hand. It then explains the theoretical and methodological approach to be used in the research. The computational corpus analysis and framing analysis will point out from the empirical data the patterns of meanings and representations in the corpus of media text within 11 years from 2006 to 2016 in 11 media outlets. Finally, the study will seek to explain the findings and argue their implications and significance in the discussion.

Framing is important in media practice. A news frame is a central organising thread that shapes the meaning of a series of events, forging a connection between them (Nelson, Oxley, & Clawson, Citation1997). Framing directs the dimension of the arguments and illuminates the core of the issue (Gamson & Modigliani, Citation1989, p. 143). Media scholars have pointed out how coverage of health issues often mobilises episodic and thematic frames (Holton, Farrell, & Fudge, Citation2014; Kang, Citation2013; McKeever, Citation2012), which are created with the focus on either the individual or societal factors and actors, respectively. Iyengar (Citation1991) argues that framing shapes how people view different issues and the public has a tendency to simplify political issues by assigning responsibility to particular actors. He suggests that when the media present an issue as an individual story, instead of presenting an issue as a social matter, the media are less likely to hold government officials and institutions accountable for dealing with the problems.

As mentioned, the existing literature is Western-centric and driven by conventional content and framing analysis. Kang’s study of United States’ television news about autism from four television news networks (ABC, CBS, NBC, and CNN) between 1990 and 2010 found autism was more frequently framed as an episodic rather than a thematic issue (Kang, Citation2013). Similarly, the most popular frames in news stories of autism published in the New York Times and the Washington Post from 1996 to 2006 were predominantly the human interest frame (63% or 189 articles), followed by the policy frame (47% or 143 articles) and the science frame (44% or 132 articles) (McKeever, Citation2012). Even though the policy frame was not the most prominent, it is a significant frame from McKeever’s study. Embedded in the policy frame was an ideology to embrace neurodiversity under the social model, which aims to accommodate individuals’ differences or disabilities to enable them to realise their rights and live a full life with equity and inclusive opportunities (Baker, Citation2011; Blume, Citation1998). Neurodiversity has been described as an innate biological aspect of the humankind in an effort to depathologise neurodivergence (Chapman, Citation2020; Walker, Citation2020). As best practice, intervention and support are increasingly based on individuals’ strength, instead of aiming for normalisation (Den Houting, Citation2019).

Sources play a critical role in media’s framing. Impartiality, balance, and objectivity as journalists’ professional rules promote the practice of reporters endeavouring to seek statements from ‘accredited’ sources (Hall, Clarke, Critcher, Jefferson, & Roberts, Citation1978, p. 254). In this process, experts guided by the presumedly disinterested pursuit of knowledge are expected to confer ‘objectivity’ and ‘authority’ on news stories. But the authors also point out that ironically, the very principles invoked to uphold the impartiality and neutrality of the media, by relying on experts’ perspectives, also give accredited sources the power to define social reality. This, in turn, leads to ‘a systematically structured over-accessing to the media of those in powerful and privileged institutional positions’, making them the primary definers of topics (p. 254). Accredited sources set the scene to frame what the problem is, who are responsible and what the solutions might be.

The media can frame a topic by giving voices to certain sources and silencing others (Bie & Tang, Citation2015). There are about 14 million Chinese people on the autism spectrum; however, autistic people were mostly silenced in Chinese media, if they were not depicted as savants with special gifts. A noticeable difference in news source patterns between the Chinese and Western news media is that only 9% of the news coverage on autism in leading newspapers in China cited government officials (Bie & Tang, Citation2015, p. 891), compared to 41% in the New York Times and the Washington Post (McKeever, Citation2012). The absence of governmental voices in Chinese news coverage suggested that the Chinese media did not hold government officials accountable to assist this ‘marginalised population’, instead locating the challenges of autism care and teaching back to the privatised domain of families (Bie & Tang, Citation2015, p. 891). This made the public even less likely to see the need to support people living with autism by means of social policy (p. 892).

By firstly inquiring into who was referred to and who was quoted the most in Vietnamese news media coverage, this research will establish who had more voice or agency in the discourse. Phelps, Graham, Tuyet, and Geeves (Citation2014) hold that voice should be interpreted as ‘activities that encourage reflection, discussion, dialogue and action’ (p. 34), thus, having a voice is a prerequisite to having power and agency. As being talked about and having a voice in the media discourse are two different things, the study asks the following question:

RQ1:

What individual and institutional stakeholders were talked about and/or given an opportunity to talk as news sources in the Vietnamese online news media between 2006 and 2016?

In their framing, journalists use a certain set of keywords more regularly than others, and when they contextualise autism with particular word choices and combinations, there are implications for how they orient the audience towards certain meanings and messages. The second research question concerns framing practice:

RQ2:

What frames were dominant or absent in the Vietnamese online news media discourse about autism from 2006 to 2016?

Materials and methods

This study builds on the definition of Entman (Citation1993): ‘to frame is to select some aspects of a perceived reality and make them more salient in a communicating text, in such a way as to promote a particular problem definition, causal interpretation, moral evaluation, and/or treatment recommendation’ (p. 52). Frames manifest by the presence or absence of certain keywords that ‘appear consistently in the text to convey thematically consonate meanings across media and time’ (Entman as cited in Miller, Citation1997, p. 368). Most frames are made up of what they include and also what they omit (Entman, Citation1993, p. 54).

Framing analysis based on the operational method of corpus linguistics analysis, computational text mining, natural language processing, or lexicometric analysis has been used and validated by a number of authors (Matthes, Citation2009; Miller, Citation1997; Wiedemann, Citation2013). Touri and Koteyko (Citation2014) suggested that with a textual analysis software, ‘the central ideas or emphasis words [may] be extracted empirically rather than personally or experientially, removing some of the subjectivity that human judgment entails’ (p. 605). They argued that extracting keywords, phrases, and clusters enables the analyst to systematically and efficiently identify the central thematic contents in the text (pp. 601, 605). Corpus analysis and framing analysis with computer assisted tools have pragmatic advantages over manual content and framing analysis. Methodologically, the researcher does not have to manually break the data into units and code them into a codebook-like conventional content and framing analysis.

In computational corpus analysis, the referral to individual and institutional stakeholders, as well as the semantics of keywords, collocations, and concordances can suggest which frames are dominant. As Edelman (Citation1993) stated, ‘the character, causes, and consequences of any phenomenon become radically different as changes are made in what is prominently displayed, what is repressed and especially in how observations are classified’ (p. 232).

To construct the corpus for this study, the most popular digital news websites in Vietnam were selected based on the global website ranking up until 31 December 2016 on Alexa.com (Alexa, Citation2016). An advanced Google search on each of these top popular news websites was conducted with the keyword tự kỷ [autism/autistic] to select 11 news websites with the most Google search results for tự kỷ [autism/autistic] up to 31 December 2016. Among them, 24 h.com.vn, Afamily.vn, Eva.vn and Kenh14.vn are news aggregation websites and sit more on the tabloid end of the spectrum, while other outlets in the list are electronic newspapers. VnExpress.net, Vietnamnet.vn, Dantri.vn and News.zing.vn are online-only media outlets, while Thanhnien.vn, Tuoitre.vn, and Nld.com.vn publish both print and electronic versions. Taken together, these media outlets fairly represent the Vietnamese online media landscape.

The corpus contained the relevant articles published in 11 outlets, over 11 years, comprising a total of over 580,000 words. This was a big enough data set for computational corpus and framing analysis, when this study examined a very targeted discourse. Kennedy (Citation2014) concurred that when the study examines many syntactic processes and high-frequency vocabulary, a corpus of between half a million and one million words is desirable (p. 68).

In English, the threshold for keyness is set at an extremely low value of a probability of one in a hundred trillion words, and such threshold of statistical significance often renders over 1,500 keywords in a certain corpus (Gabrielatos & Baker, Citation2008, p. 10). Lower frequency suggests lower significance of the semantic meaning of the words, phrases, or clusters in the corpus. This study mostly examines words, phrases, or clusters which stand from the 1st to the 200th in the word and cluster frequency lists, with a frequency threshold higher than one in ten thousand. It is worth noting that clusters with two or three single words can be compound words in Vietnamese. Thus, this study uses the word cluster for compound words as well.

Findings

In regard to RQ1, family members were found to be the most visible, but professionals were given more voice in the corpus. In response to RQ2, the analysis identified two major frames, namely family stories and medical issues, while public health or social policy frame was relatively absent in this corpus. The findings are presented in detail below.

Family members were most visible, but professionals were most vocal

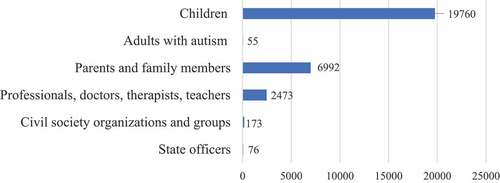

When the media mention or quote someone, they are highlighting their visibility and/or voice. Vietnamese online news media related autism primarily to children. The word trẻ [child] appeared 7,430 times, accounting for 1.27% of the whole text and standing as the 4th most frequent word in the corpus. In addition, con [child/offspring] was seen 6,278 times as the 8th most frequent word, as well as other words for children such as bé [child], em [child/younger person] and cháu [child]. In total, 19,760 single words and variations for children appeared in the corpus, accounting for 3.39% of the whole text, making children collectively the most frequently talked about in the corpus, as demonstrated in .

While it is not necessarily surprising that autism and childhood were frequently discussed together, the relative dearth of mentions of adults with autism was an interesting finding. With a deductive search, the words người lớn [adult], người trưởng thành [grown-up], and thanh niên [youth/youngster] with autism were mentioned only 32, 12 and 11 times, respectively, in the entire corpus, whose total is lower than the 0.0001 threshold. represents mentions of children, adults with autism, parents, and family members in three different groups to demonstrate the distinctive level of their visibility in the corpus, in comparison to other groups.

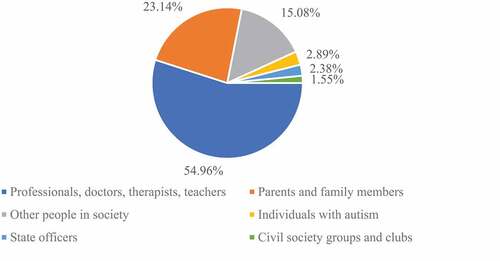

To narrow down the quoting sample and examine who was quoted the most often in the corpus, the study examined the concordance list of popular quoting verbs, namely, nói [say/talk/speak] and cho biết [state/say/reveal]. There were 605 instances of cho biết [state/say/reveal]. There were actually 2,185 instances of nói [say/talk/speak] in the corpus, but most of them referred to speech disorders such as chậm nói [delayed speech], nói lắp [stuttering], nói lặp lại/nói nhại [echoing] and other acts of speaking. Only 358 instances of nói [say/talk/speak] were used as quoting verbs. The combination of these two quoting verbs made up a sample of 963 instances of quoting someone. All the instances of nói [say/talk/speak] and cho biết [state/say/reveal] were categorised into six groups, including quotes by parents, professionals, individuals with autism, civil society groups, government officers, and others.

Despite the frequency with which children with autism were mentioned, the voice of both children and adults with autism was hardly heard in Vietnamese media accounts. Between the two quoting verbs, nói [say/talk/speak] was a neutral quoting verb, while cho biết [state/say/reveal] was often used for mature speakers, with a more authoritative connotation. Out of 358 instances of nói [say/talk/speak], individuals with autism were quoted 28 times, mostly with basic utterances. Overall, out of the whole 963 instances of quotings with both nói [say/talk/speak] and cho biết [state/say/reveal], individuals with autism had their voice reported in just under 3% of the full sample of voices/sources as demonstrated in . When individuals with autism were only occasionally asked to talk or reported as talking in the media stories, their voices were seldom heard, and they were portrayed more like passive objects than active agents.

The prominence of parents as actors in the media discourse was also evident. Mẹ [mother] appeared 3,329 times, as the 21st most frequent word in the corpus, while cha/ba/bố [father] appeared 1,877 times, either as standing alone, but mostly in the combined word cha mẹ/ba mẹ/bố mẹ [father and mother/parents]. The comparative reference to mothers and fathers indicated the disparity in the reporting of child caring roles in the families.

The frequency of references to all professional identities like experts, researchers, doctors, therapists, teachers, and other support staff (2,473 times) was much less than the frequency of reference to parents and families (6,992 times), as demonstrated in . However, professionals were quoted in over 55% of instances (or 532 times) of direct and indirect quoting, while parents and families were quoted in only 23% (or 224 times) of the same sample, as demonstrated in .

References to self-help and advocacy groups were not often seen in the corpus. There were only 103 mentions of câu lạc bộ [club] and CLB [club] of families living with autism or community groups supporting autism, 43 entries of dự án [project] relate to autism or disability, and 27 entries of Mạng lưới Người tự kỷ Việt Nam [Vietnam Autism Network]. Only 1.5% of all the quoting instances quoted someone from those civil society groups, as demonstrated in .

State bodies and their officers at national, ministerial, and local levels, generally called state authorities, appeared only 76 times in the corpus. Most of the mentions of authorities were invocations on the part of parents/professionals calling for policy responses. They were also mentioned in relation to the incident of child abuse at an autism centre in Ho Chi Minh City in 2014. State officers spoke in 2.4% of the quoting instances. This suggested that the media did not attempt or manage to interview state officers and hold them accountable with regard to framing autism as a public health and social policy issue.

Autism framed as a medical problem

Autism is usually framed as a medical problem in Vietnamese digital news media, illustrated by the fact that many words high up in the word frequency and cluster frequency lists are medical and scientific terms. Many of the most frequent clusters in were compound words. Words or phrases related to the medical frame were mainly to indicate psychiatric symptoms, medical processes, treatments, and scientific terms which were used to describe a health condition in the medical frame and highlighted in italics. Obviously, tự kỷ [autism] was the number one frequent word in the corpus with 6,999 entries, at 1.02% frequency. Similarly, trẻ tự kỷ [autistic child] and bệnh tự kỷ [autism disease] stood as the third and sixth most frequent phrases. Some random clusters without a clear referential meaning were removed for reasons of space efficiency and clarity.

Table 1. The most frequent words/clusters, with medical and scientific terms in italics.

Medical terms such as dấu hiệu [sign/symptom], biểu hiện [sign/symptom], nguy cơ [risk], chẩn đoán [diagnosis], hội chứng [syndrome], rối loạn [disorder], can thiệp [intervention], and điều trị [treat] were amongst the most frequent compound words. The high frequency of medical terms in the corpus suggested that the media framed autism mainly as a medical issue.

Bệnh [disease] was the 22nd most frequent single word in the corpus, appearing 3,316 times, accounting for 0.57% of the whole text. Similarly, there were 2,388 instances of bị [subject to/suffering], equivalent to 0.41% of the whole text, and it stood 35th in the word frequency list. The word bị can either be a component of a forceful passive voice like subject to, or it can negatively mean suffering.

Autism was also often associated with behavioural challenges in the media discourse. For example, 492 incidences of hành vi [behaviour] and 492 incidences of khó khăn [difficulty/challenge] were seen in the corpus, ranking, respectively, 42nd and 43rd in the cluster frequency list and each accounting for 0.08% of the text. Unsurprisingly, hành vi [behaviour] often appeared in negative lexical clusters such as rối loạn hành vi [behaviour disorder] or hành vi lặp đi lặp lại/rập khuôn [repetitive/rigid behaviour]. Khó khăn [difficulty/challenge] was often seen together with học tập [learning] and giao tiếp [interpersonal communication].

When identifying a person with autism, Vietnamese language mostly used tự kỷ [autistic] as an adjective, for example, trẻ tự kỷ/người tự kỷ/con tự kỷ/bạn tự kỷ [autistic child/autistic person/autistic offspring/autistic friend], as if tự kỷ [autistic] was the only defining character of that person. Even though in the Vietnamese language, the adjective always stands after the noun that it modifies, the Vietnamese linguistic convention makes the adjective an integral part of the noun that it modifies, shaping autism as an inseparable part of the individuals’ identity.

‘Person first’ or ‘disability first’ language is a subject of debate internationally among academics, advocates, and individuals with autism. Proponents of ‘Person first’ language argue that it is preferable to avoid using the diagnosis to label and identify a person (Blaska, Citation1993; Dunn & Andrews, Citation2015; Titchkosky, Citation2001). For example, ‘a person with autism’ or ‘a person living with autism’ indicates autism is just part of that individual’s identity, not the sole defining characteristic. Most advocacy organisations in the United Kingdom, United States, and Australia favour this language as a way to emphasise ‘people’s humanity’ (Fernald as cited in Wilkinson & McGill, Citation2009). However, those who prefer to use ‘autistic person/individual’, including people on the spectrum, hold that it is not necessary to separate autism from the person as if autism is a bad thing (Sinclair, Citation2013). Additionally, there is a middle ground position that suggests language use should depend on the context and that it is up to communication participants to decide to use person-first or disability first language (Kenny et al., Citation2016). While the word tự kỷ [autism/autistic] was still used to ridicule lonely, weird, or depressing behaviour of anyone in the population, the subtleties of the debates about person first or disability first elsewhere were not likely to register in the Vietnamese context.

In addition, the stereotyping of individuals with autism and their families was exacerbated with such words as một mình [on one’s own/alone] (222 times), bất thường [unusual] (199 times), hạn chế [limited] (132 times), la [scream] (126 times), hét [scream] (92 times), giận [angry] (79 times), thờ ơ [indifferent] (62 times), không quan tâm [does not care/does not pay attention] (58 times), cô độc [lonely/alone] (51 times), thu mình [withdraw] (40 times), cáu [angry] (32 times), and hung hăng [violent] (14 times). Collectively, these words stereotyped people by ‘their category and not as individuals’ (Smart & Smart, Citation2006, p. 30), with ‘their disability (first or alone) rather than their personhood’ (Wilkinson & McGill, Citation2009, p. 74).

Those individuals with autism who got the most attention in the Vietnamese online news media were the ones with special abilities, which reconfirmed what has been observed elsewhere in the world (Bie & Tang, Citation2015; Murray, Citation2008). Đặc biệt [special] stood as the 19th most frequent compound word with 671 appearances, accounting for 0.12% of the words in the corpus. The word đặc biệt [special] most often collocated with special education, care and needs, or with talents, gifts, abilities, and skills.

In summary, the findings in this section have illustrated that the medical frame in the Vietnamese media positioned autism as a disease, a disorder, or an acquired form of suffering, which needed to be fixed with intervention and treatment.

Autism framed as family stories

As discussed above, children, mothers, fathers, parents, and families were talked about the most frequently in the corpus, which suggested that autism stories were regularly framed as family stories. The concordance lists of mẹ [mother], bố/ba/cha [father], bố mẹ/ba mẹ/cha mẹ [parents] and gia đình [family] revealed that when they were talked about, family members were usually mentioned in relation to their roles, hopes, and challenges in caring for their children with autism. Family life with autism was related to nước mắt [tears] (179 times), lo lắng [worry/anxiety] (167 times), căng thẳng [stress] (109 times), áp lực [pressure] (80 times), sợ hãi [fear] (69 times), hoang mang [puzzling/confusion] (42 times), tuyệt vọng [despair] (32 times), and bi kịch [tragedy] (12 times). Parents’ care for and support of children with autism were described with war-like terms such as cuộc chiến [battles] (24 times), chiến đấu [to fight against] (27 times), đối mặt [to confront] (58 times) and chống lại [to combat] (19 times). Collectively, autism was often described with negative stereotypes, making family life with autism a fearful prospect that the families alone had to deal with.

Autism barely framed as a social policy matter

Even though social policy is recognised as one of the frames in existing literature about autism representation (Holton, Farrell, & Fudge, Citation2014; Kang, Citation2013; McKeever, Citation2012), it appeared insignificant in the Vietnamese media corpus. Thus, both inductive and deductive procedures were undertaken to look for patterns hypothetically used to construct the particular frame in the word and cluster frequency lists.

In the top cluster frequency list, there were 495 incidents of hòa nhập [integrate/integration/integrative], accounting for 0.08% of the text, making it the 41st most common compound words in the corpus. Hoà nhập is a compound word in Vietnamese, where hoà literally means to mix and nhập means to fit in/enter/merge/integrate. The Vietnamese language does not really have an equivalence for inclusion, even though official documents sometimes use hoà nhập interchangeably to indicate both integration and inclusion. Linguistically, the words include, inclusive, and inclusion in English put more focus on the institutional agency and environment, where schools, communities, and society play active agented roles in offering inclusive and enabling conditions for everyone, taking into account individuals’ diverse needs. The word hoà nhập [integrate/integrative/integration] in Vietnamese puts more focus on the individuals’ capacity to fit in, making individuals the active agents of integration.

Besides, a deductive search was conducted with such keywords as chính sách [policy], quyền [right], bình đẳng [equity], and công bằng [equal/equality/fair/fairness/justice]. There were only 40 entries of chính sách [policy] in the corpus, of which 25 entries talked about the absence of policy, or call for a policy for people living and working with individuals on the autism spectrum, and the rest discussed policies in other countries. Similarly, quyền [right] in relation to people living with autism only appeared 21 times out of 88 entries of quyền. There were only 15 instances of bình đẳng [equal/equality/fair/fairness/justice] and 15 instances of công bằng [equity] in the whole corpus of 11 years’ media coverage. The words chính sách [policy], bình đẳng [equal/equality/fair/fairness/justice], and công bằng [equity] accounted for less than 0.01% of the text, so it was insignificant that WordSmith did not even count their frequency.

There were 134 entries of chấp nhận [accept/embrace/admit/agree/acknowledge], but the word connected to the theme of accepting and embracing the challenges of autism in only two articles; the rest of the time, the word only meant admitting, acknowledging and agreeing about autism diagnoses, or admitting children with autism to schools or not. Indeed, chấp nhận [accept/embrace/admit/agree/acknowledge] collocated with không [no/not] to make the negative form 62 times, or nearly half of the incidences.

As observed before, authorities were not significantly referred to or quoted in the corpus, which suggested that the media did not hold them accountable for autism issues. Both the presence and absence of semantic elements significantly suggested the influence of popular ideologies in the corpus. So autism was barely represented in terms of the social policy frame as the above low keyword frequency and collocations suggested. There might be other specific frames from the data, but this study focuses on these three major frames to highlight their implications.

Discussion

It has been found that children with autism were the most frequently talked about; however, they were rarely given the opportunity to speak for themselves. This demonstrated their high visibility but minimal voice in the corpus. Traditionally, within the Confucius hierarchical structuring of family and social relationships, Vietnamese children are expected to obey adults and not always treated with the belief that they have important opinions in matters relating to themselves. The practice of formulating child-related policies and laws from an adult perspective originates from the traditional and deep-rooted moral values in Vietnam (Phelps, Nhung, Graham, & Geeves, Citation2012). Three necessary factors for individuals with autism to participate in civic activities include space (or the opportunity to convey one’s view), audience, and influence (Lundy, Citation2007), but in Vietnam, the very first factor, the opportunity for children and individuals with autism to raise their voice in the media, was missing. The motto ‘nothing about us without us’ is not upheld in Vietnamese news media.

The lack of acceptance and voice of children with autism in Vietnamese everyday life and in online news media originated from social pressure. Various authors have suggested that Confucianism places a big emphasis on ‘hiếu’ [filial piety] (Canda, Citation2013), in which children uphold the family name, carry on the family tree, and build further reputation by means of their success, which is judged by their achievements in education and social life. An adult child who cannot return grace to his or her parents is considered as not fulfilling one of the most fundamental Confucius values of piety in Vietnamese society: the obligation of children to return to their parents the love and labour that has been expended on them (Gammeltoft, Citation2008). In this Confucius culture and authoritarian political economy, when individuals with autism disabilities cannot fulfil these virtues of filial piety, they are even more stigmatised and marginalised.

When framed as exhibiting a medical disease, individuals with autism in Vietnam were regularly stereotyped with abnormality, behavioural problems, and challenges. When too much focus was put on problematic behaviours and challenges, the media constructed an ideology that exclusion was justifiable. When Vietnamese media used the word bệnh [disease] intensively in the corpus, they did not see the condition as a disability or an aspect of human diversity that need facilitation. The news media did not take the role of promoting progressive social model of disabilities and neurodiversity with a right-based ideology that has been incorporated in various Vietnamese laws so that individuals are enabled to materialise their rights, regardless of their disabilities. Some right-based and neoliberal ideology is present in the laws, thanks to the pressure from international organisations and donors (Painter, Citation2005), but has not been internalised in real life or in the media.

Another finding from the corpus analysis was that mothers were the second most frequently talked about actors in the corpus, and fathers’ role in caring and supporting children with autism was less frequently reported, which reinforced the perception that it was mainly the responsibility of mothers to care for and support their children. Research commissioned by Oxfam finds that journalists in Vietnam hold stereotypical perceptions of gender roles and reproduce these perceptions in their reports (Vu, Lee, Duong, & Barnett, Citation2017). According to another Oxfam report, females account for 48.4% of the country’s workforce, making Vietnam one of the countries with the highest rate of women in the labour force (Vietnam Law and Legal Forum, Citation2018), but housework and childcare are still considered the job of women. Similarly, the finding in this analysis suggested that by featuring mostly women in the caretaking role for children with autism, the media further burdened the mothers with heavier childcare duty.

Collectively, parents were referred to much more frequently than professionals in healthcare, education, and social affairs in the Vietnamese media coverage about autism; however, professionals’ voices were quoted much more often in the corpus. Apart from reporters’ preference for quoting professionals, some professionals had a strong motivation to promote their commercial services or expertise. Given the low level of expertise, capacity, practice, and research in autism in Vietnam (Ha, Whittaker, Whittaker, & Rodger, Citation2014), the professionals’ access and voice in the media put them in the position to shape the representation of autism from their service providers’ perspectives and interests in this high power distance culture.

When children, parents, and families were the most frequently talked about, and the autism condition was described with stigmatised and sensationalised language, the media reports framed autism as a personal medical problem and a family issue, rather than a social policy matter. Various studies (Bie & Tang, Citation2015; Kang, Citation2013) have pointed out that if autism is articulated as a family or personal medical problem within the episodic frame, this makes the public less likely to hold government agencies or public officials accountable for the improvement of problems, thereby lowering the expectation that the public can take part in the political process of determining solutions and outcomes. The analysis in this article has strikingly revealed that Vietnamese authorities rarely appeared in the corpus. Thus, Vietnamese media were similar to their Chinese colleagues in not holding the authorities accountable for realising an inclusion policy for people with autism (Bie & Tang, Citation2015).

The use of particular language, namely the use of hòa nhập with the connotation of integrate/integrative/integration, rather than include/inclusive/inclusion, constructed and reflected the ideology that individuals had to be normalised to fit in and be accepted in social life, rather than expecting the community to facilitate those individuals’ citizenship rights in relation to legally guaranteed access to education, healthcare, and other social engagements. Thus, the ideology of integration in Vietnamese media was not yet in step with what inclusion meant elsewhere in the world. The concept of neurodiversity is certainly foreign to this collective culture, which puts emphasis on conformity and belonging.

In addition, the official discourse in Vietnam often emphasises the Party-State’s expectation of citizens to be capable and healthy as an indicator of their patriotism and responsibility (Gammeltoft, Citation2014b). In the words of the national cult and leader Minh (Citation1946): ‘Each weak citizen causes the country to be weak; each healthy and strong citizen makes the entire country healthy and strong’. This official narrative impacted the way citizens viewed themselves and others, with pressure to optimise individual capabilities to fit in with the expectation of the national economy and belong to the society. The way the media framed autism as a family and medical problem, not a social policy issue, was influenced by long-standing and widely circulated official narratives on health, capability, and patriotic responsibility.

Conclusion

This is the first study to combine corpus analysis with framing analysis by computer-assisted method to examine a media discourse about autism in an authoritarian political economy. The approach rendered an objective insight on how media have been heavily influenced by the normalisation ideology in a hybrid authoritarian and neoliberalised political economy. The approach is demonstrated to be an advantage in big data analysis by enabling the researcher to identify the prominent language patterns and broad frames based on the frequency and distribution of the keywords’ collection, collocations, and concordances (Touri & Koteyko, Citation2014, p. 611).

The method might be useful to researchers, practitioners, advocates, and policy-makers who need to work with a big volume of digital data so as to grasp an objective broad overview in ongoing, periodical, or urgent media monitoring. This method does more than pointing out positive or negative social sentiments about a subject matter, it instead suggests the frames and facilitates the interpretation of embedded ideologies and hidden insights. Thus, this understanding will enable the concerned stakeholders in adjusting communication strategy, setting agenda, and advocating for policy and social changes.

This study contributed specific Vietnamese perspectives to the literature on representation of a public health issue and the affected population in the news media. This study has invoked different local evidence, views, and arguments. It highlighted the silence of people with autism as well as the disparity in the role of mothers and fathers in caring for children with autism. It pointed to the absence of state authorities in the media corpus, which was similar to the situation in its Communist counterpart in China. It once again reconfirmed the access and dominance of the doctors, teachers, and other professionals’ role in shaping the representation of autism in the media discourse. The study has put into perspective the collectivistic and high power distance of family and social relations in the context of the persistence of the orthodox authoritarianism regime, the legacy of the centrally planned economy, and the new wave of neoliberalism in Vietnam. The arguments in this study can be translated into other social injustices reported by the news media about other marginalised communities in Vietnam and other countries with a similar cultural political economy.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Alexa. (2016 December 31). Top sites in Vietnam. Retrieved from https://www.alexa.com/topsites/countries/VN

- Baker, D. L. (2011). The politics of neurodiversity: Why public policy matters. Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner Publishers.

- Bie, B., & Tang, L. (2015). Representation of autism in leading newspapers in China: A content analysis. Health Communication, 30(9), 884–893. doi:10.1080/10410236.2014.889063

- Blaska, J. (1993). The power of language: Speak and write using “person first”. Perspectives on Disability, 2, 25–32.

- Blume, H. (1998, September 2). Neurodiversity: On the neurological underpinnings of geekdom. The Atlantic. Retrieved from https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/1998/09/neurodiversity/305909/

- Canda, E. R. (2013). Filial piety and care for elders: A contested Confucian virtue reexamined. Journal of Ethnic & Cultural Diversity in Social Work, 22(3–4), 213–234. doi:10.1080/15313204.2013.843134

- Chapman, R. (2020). Defining neurodiversity for research and practice. In H. Bertilsdotter Rosqvist, N. Chown & A. Stenning(Eds.), Neurodiversity Studies, A New Critical Paradigm (Vol. 285, pp. 218–220). New York: Routledge.

- Den Houting, J. (2019). Neurodiversity: An insider’s perspective (Vol. 23, pp. 271–273). London, England: SAGE Publications Sage UK.

- Doan, M. -A., & Bilowol, J. (2014). Vietnamese public relations practitioners: Perceptions of an emerging field. Public Relations Review, 40(3), 483–491. doi:10.1016/j.pubrev.2014.02.022

- Dunn, D. S., & Andrews, E. E. (2015). Person-first and identity-first language: Developing psychologists’ cultural competence using disability language. The American Psychologist, 70(3), 255–264. doi:10.1037/a0038636

- Edelman, M. (1993). Contestable categories and public opinion. Political Communication, 10(3), 231–242. doi:10.1080/10584609.1993.9962981

- Entman, R. M. (1993). Framing: Toward clarification of a fractured paradigm [Article]. The Journal of Communication, 43(4), 51–58. doi:10.1111/j.1460-2466.1993.tb01304.x

- Fenton, N. (2011). Deregulation or democracy? New media, news, neoliberalism and the public interest. Continuum, 25(1), 63–72. doi:10.1080/10304312.2011.539159

- Gabrielatos, C., & Baker, P. (2008). Fleeing, sneaking, flooding: A corpus analysis of discursive constructions of refugees and asylum seekers in the UK press, 1996-2005. Journal of English Linguistics, 36(1), 5–38. doi:10.1177/0075424207311247

- Gammeltoft, T. (2008). Childhood disability and parental moral responsibility in northern Vietnam: Towards ethnographies of intercorporeality [research article]. The Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute, 14(4), 825–842. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9655.2008.00533.x

- Gammeltoft, T. (2014b). Toward an anthropology of the imaginary: Specters of disability in Vietnam. Ethos, 42(2), 153–174. doi:10.1111/etho.12046

- Gamson, W. A., & Modigliani, A. (1989). Media discourse and public opinion on nuclear power: A constructionist approach [research-article]. The American Journal of Sociology, 95(1), 1. doi:10.1086/229213

- Hall, S., Clarke, J., Critcher, C., Jefferson, T., & Roberts, B. (1978). Policing the crisis: Mugging, law and order and the state. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Ha, V. S., Whittaker, A., Whittaker, M., & Rodger, S. (2014). Living with autism spectrum disorder in Hanoi, Vietnam. Social science & medicine, 120, 278–285. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.09.038

- Holton, A. E., Farrell, L. C., & Fudge, J. L. (2014). A threatening space? Stigmatization and the framing of autism in the news. Communication Studies, 65(2), 189–207. doi:10.1080/10510974.2013.855642

- Iyengar, S. (1991). Is anyone responsible?: How television frames political issues. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Kang, S. (2013). Coverage of autism spectrum disorder in the US television news: An analysis of framing. Disability & Society, 28(2), 245–259. doi:10.1080/09687599.2012.705056

- Kennedy, G. (2014). An introduction to corpus linguistics. London: Routledge.

- Kenny, L., Hattersley, C., Molins, B., Buckley, C., Povey, C., & Pellicano, E. (2016). Which terms should be used to describe autism? Perspectives from the UK autism community. Autism, 20(4), 442–462. doi:10.1177/1362361315588200

- Lundy, L. (2007). ‘Voice’ is not enough: Conceptualising article 12 of the United Nations convention on the rights of the child. British Educational Research Journal, 33(6), 927–942. doi:10.1080/01411920701657033

- Matthes, J. (2009). What’s in a frame? A content analysis of media framing studies in the world’s leading communication journals, 1990-2005. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly, 86(2), 349–367. doi:10.1177/107769900908600206

- McKeever, B. W. (2012). News framing of autism: Understanding media advocacy and the combating autism act. Science communication, 35(2), 213–240. doi:10.1177/1075547012450951

- McKinley, C. (2008). Can a state-owned media effectively monitor corruption? A study of Vietnam’s printed press. Asian Journal of Public Affairs, 2(1), 12–38.

- Miller, M. M. (1997). Frame mapping and analysis of news coverage of contentious issues. Social science computer review, 15(4), 367–378. doi:10.1177/089443939701500403

- Minh, H. C. (1946, March 27). Sức khỏe và thể dục [Health and exercise] Cứu quốc [Save the nation].

- Murray, S. (2008). Representing autism: Culture, narrative, fascination. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press.

- Nelson, T. E., Oxley, Z. M., & Clawson, R. A. (1997). Toward a psychology of framing effects. Political Behavior, 19(3), 221–246. doi:10.1023/A:1024834831093

- Nguyen, A. (2013). Online news audiences: The challenges of web metrics. In K. Fowler-Watt & S. Allan (Eds.), Journalism: New challenges (pp. 146–161). Bournemouth: Bournemouth University .

- Painter, M. (2005). The politics of state sector reforms in Vietnam: Contested agendas and uncertain trajectories. The Journal of Development Studies, 41(2), 261–283. doi:10.1080/0022038042000309241

- Phelps, R., Graham, A., Tuyet, N. H. T., & Geeves, R. (2014). Exploring Vietnamese children’s experiences of, and views on, learning at primary school in rural and remote communities. International Journal of Educational Development, 36, 33–43. doi:10.1016/j.ijedudev.2013.12.004

- Phelps, R., Nhung, H. T. T., Graham, A., & Geeves, R. (2012). But how do we learn? Talking to Vietnamese children about how they learn in and out of school. International Journal of Educational Research, 53, 289–302. doi:10.1016/j.ijer.2012.04.003

- Sinclair, J. (2013). Why I dislike “person first” language. Autism Network International. Retrieved from http://www.larry-arnold.net/Autonomy/index.php/autonomy/article/view/OP1/html_1

- Smart, J. F., & Smart, D. W. (2006). Models of disability: Implications for the counseling profession. Journal of Counseling & Development, 84(1), 29–40. doi:10.1002/j.1556-6678.2006.tb00377.x

- Thiem, B. H. (2016). The influence of social media in Vietnam’s elite politics. Journal of Current Southeast Asian Affairs, 35(2), 89–111. doi:10.1177/186810341603500204

- Titchkosky, T. (2001). Disability: A rose by any other name? “People-first” language in Canadian society. Canadian Review of Sociology/Revue Canadienne de Sociologie, 38(2), 125–140. doi:10.1111/j.1755-618X.2001.tb00967.x

- Touri, M., & Koteyko, N. (2014). Using corpus linguistic software in the extraction of news frames: Towards a dynamic process of frame analysis in journalistic texts [Article]. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 18(6), 601–616. doi:10.1080/13645579.2014.929878

- Vietnam Law and Legal Forum. (2018). Vietnamese women still face numerous barriers to employment. Retrieved from http://vietnamlawmagazine.vn/vietnamese-women-still-face-numerous-barriers-to-employment-6189.html

- Vu, H. T., Lee, T. -T., Duong, H. T., & Barnett, B. (2017). Gendering leadership in Vietnamese media: A role congruity study on news content and journalists’ perception of female and male leaders. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly, 95(3), 565–587. doi:10.1177/1077699017714224

- Walker, N. (2020). Neurodiversity: Some basic terms and definitions. Neurocosmopoloitanism. 2014. In.

- Wiedemann, G. (2013). Opening up to big data: Computer-assisted analysis of textual data in social sciences. Historical Social Research/Historische Sozialforschung, 14, 332–357.

- Wilkinson, P. P. W. N. C., & McGill, P. (2009). Representation of people with intellectual disabilities in a British newspaper in 1983 and 2001 [Article]. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 22(1), 65–76. doi:10.1111/j.1468-3148.2008.00453.x