?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

This research investigated the intertwined nature of university students’ communication in learning settings and their satisfaction/frustration of basic psychological needs. To do so, it collected data from 307 university students and explored the communication patterns defined by interrelationships among achieving communication goals, feeling confident about communicating in learning settings, and being satisfied in communicating with instructors. In addition, it assessed the degree to which groups of students who had different patterns with regard to these communication factors significantly differed in terms of the satisfaction and frustration of their basic psychological needs for autonomy, competence, and relatedness. To examine these aspects latent profile analyses were conducted. Findings show that three groups (that is, three classes or profiles) parsimoniously represented students’ patterns of communication. Notably, profiles that illustrated more adaptive communication patterns were associated with both stronger basic needs satisfaction and weaker needs frustration than profiles that reflected less adaptive communication patterns.

Understanding how motivation and communication factors interact helps build a strong foundation for student success (Higgins, Citation2019; Hodis & Hodis, Citation2015). For example, students who are confident they can communicate effectively are also likely to have satisfying communication with teachers and expect to do well in school (Hodis & Hodis, Citation2012, Citation2013, Citation2015). To advance knowledge of the interrelationships among university students’ communication in learning settings and key factors shaping their motivation, this research first examined whether latent (i.e. unobserved) groups of students are identified by different patterns (i.e. profiles/configurations) of three key communication factors: the extent to which students achieve their communication goals, have strong self-efficacy beliefs about communicating in learning settings, and are satisfied in communicating with their teachers/instructors. This approach which, to our knowledge, has yet to be used in conjunction with these communication factors, facilitates a fresh look at how important determinants of effective communication in learning settings coalesce within persons. In turn, this new information helps map (again for the first time) the specific typologies that can be uncovered by considering information on these three communication factors.

Subsequently, this research analysed whether these groups (i.e. latent classes/typologies) differed with regard to students’ satisfaction and frustration of basic psychological needs for autonomy, competence, and relatedness (Ryan & Deci, Citation2017, Citation2020; Vansteenkiste, Ryan, & Soenens, Citation2020). Satisfaction and frustration of basic psychological needs are critical factors that influence how people function, the type and strength of their motivation, as well as their wellbeing (Ryan & Deci, Citation2017). Hence, the second stage of our research enabled a (much needed and) more finely grained understanding of the associations between students’ communication profiles and key determinants of their motivation; this is discussed in the next sections.

Uncovering the combinations of communication factors that characterise different groups of students and the psychological underpinnings of each type of communication configuration facilitates a fuller understanding of the complex aspects supporting the effectiveness of communication instruction. For example, this enhanced understanding could lead to the development of (group-level) customised instructional strategies (or interventions) that take into consideration both students’ standing on key communication factors and the extent to which their basic psychological needs are satisfied/frustrated. In turn, this targeted and relatively more individualised approach is likely to be more effective than a ‘one size fits all’ alternative that assumes that students generally achieve their communication goals and provides undifferentiated instruction. We further elaborate on the benefits of identifying different configurations of communication factors and examining their relationships with satisfaction/frustration of basic needs in the discussion section.

Theoretical framework

We begin this section with a discussion of the communication factors examined in this research. Following this, we provide information regarding basic psychological needs satisfaction and frustration.

Achieving communication goals

People’s motivation is an important factor underpinning their communication interactions (Higgins, Citation2019). In turn, the goals people set when communicating (e.g. providing or obtaining information) shape their motivation to communicate (Berger, Citation2002; Berger & Palomares, Citation2011; Dillard, Citation1997, Citation2004; Palomares, Citation2014; Wilson, Citation2002). Notably, whether or not people achieve their communication goals influences how they perceive their communication encounters (e.g. how they evaluate the communication competence of their communication partners; Palomares, Citation2013). Therefore, examining the interrelationships among the attainment of communication goals and key antecedents of motivated behaviours and cognitions (i.e. frustration/satisfaction of basic psychological needs) – as we do in this research – may provide new information on how to facilitate/support effective communication in learning settings and beyond.

Self-efficacy regarding communicating in learning environments

Bandura (Citation1997) conceptualised self-efficacy as referring to ‘beliefs in one’s capabilities to organise and execute the courses of action required to produce given attainments’ (p. 3). Consistent with this theorising, self-efficacy pertaining to communication has been defined as encompassing people’s confidence in their capability to communicate effectively (Hodis & Hodis, Citation2012, Citation2013, Citation2015; Koesten, Miller, & Hummert, Citation2002). In turn, self-efficacy with regard to communicating in school (i.e. school-related communicative self-efficacy; Hodis & Hodis, Citation2012) comprises feelings of confidence about the ability to communicate in learning settings.

When students have strong self-efficacy beliefs about communicating in learning environments, they are confident they can ask questions in their courses, participate productively in group activities, and communicate effectively with their peers/instructors/university staff (e.g. advisers, counsellors; Hodis & Hodis, Citation2012, Citation2013, Citation2015). In addition, self-efficacy with regard to communicating in school influences how students engage in learning tasks/activities (Frisby & Martin, Citation2010; Teven & McCroskey, Citation1997; Voelkl, Citation1995) and supports beliefs that they can do well in school and attain valuable goals (Hodis & Hodis, Citation2012, Citation2015; Martin, Myers, & Mottet, Citation1999; Mottet, Martin, & Myers, Citation2004; Myers, Martin, & Mottet, Citation2002a, Citation2002b).

Satisfaction in communicating with a teacher/instructor

Communication satisfaction is the valenced evaluation (i.e. positive-satisfied; negative-dissatisfied) of the degree to which individuals meet their goals and expectations regarding communication (Hecht, Citation1978a, Citation1978b). Relatedly, satisfaction in communicating with a teacher (SCT) is the specific instantiation of communication satisfaction in educational contexts (Goodboy, Martin, & Bolkan, Citation2009). The conceptualisation of SCT reflects the fact that communication encounters between students and teachers (i) revolve around aspects that are relevant to learning/teaching; (ii) are restricted in time (e.g. typical conversations between students and instructors are short); and (iii) are influenced by a power differential (Frymier & Houser, Citation1999; Goodboy, Martin, & Bolkan, Citation2009; Martin, Mottet, & Myers, Citation2000; Martin, Myers, & Mottet, Citation1999).

Past research findings suggest that there are strong associations between important communication factors and satisfaction/frustration of basic psychological needs. We review relevant research about these associations below, after we define needs satisfaction and frustration.

Satisfaction and frustration of basic psychological needs

Motivation is conceptualised as the key factor that ‘both energises and gives direction to behaviour’ (Ryan & Deci, Citation2017, p. 13; emphases in original). Notably, Self-Determination Theory (SDT) has proposed that motivation differs not only in strength (i.e. stronger vs. weaker motivation) but also in type (Ryan & Deci, Citation2017). With regard to the latter, two commonly studied types of motivation proposed by SDT are (i) autonomous motivation, which is facilitated by high levels of basic psychological needs satisfaction and low levels of needs frustration; and (ii) controlled motivation, which is brought about by low needs satisfaction and high needs frustration (Ryan & Deci, Citation2017).

Basic psychological needs (BPNs) are ‘universal necessities for healthy development and psychological wellness’ (Ryan & Deci, Citation2016, p. 97). Satisfaction of BPNs is critical for appropriate functioning in any context/environment whereas frustration (or thwarting) of BPNs leads to maladaptive functioning (Ryan & Deci, Citation2016, Citation2017; Vansteenkiste, Ryan, & Soenens, Citation2020). Importantly, the same person may experience some degree of both satisfaction and frustration of BPNs (Li, Chen, Liu, & Yao, Citation2020; Warburton, Wang, Bartholomew, Tuff, & Bishop, Citation2020). In learning settings, ‘instructors play an important role in facilitating or thwarting the psychological need fulfilment of students’ (Baker & Goodboy, Citation2018; for a similar point of view see, p. 69; Goldman & Brann, Citation2016). Below, we define the three BPNs.

Autonomy reflects individuals’ need to experience volition and initiative with regard to their actions (Ryan & Deci, Citation2020). In contexts that support their autonomy, people’s thoughts and behaviours reflect their interests and values (Ryan & Deci, Citation2017; Vansteenkiste, Ryan, & Soenens, Citation2020). On the contrary, in environments/settings where people’s need for autonomy is thwarted (e.g. when they feel pressured to do an activity), their engagement in activities is likely to be inconsistent with their enduring priorities and values (Ryan & Deci, Citation2017).

Competence comprises people’s need to feel effective in key aspects of their lives (Ryan & Deci, Citation2017, Citation2020; Warburton, Wang, Bartholomew, Tuff, & Bishop, Citation2020). In environments that support their competence (e.g. by providing appropriate scaffolding for new tasks), individuals are likely to take advantage of opportunities to learn new skills and extend existing abilities (Ryan & Deci, Citation2017; Vansteenkiste, Ryan, & Soenens, Citation2020). The need for competence is thwarted in contexts where challenges markedly exceed individuals’ abilities or when people receive harsh criticism or overwhelmingly negative feedback (Ryan & Deci, Citation2017; Vansteenkiste, Ryan, & Soenens, Citation2020). In these situations, people are more likely to feel helpless and lack motivation.

Relatedness reflects people’s need to bond with others, care for them, and be cared for (Ryan & Deci, Citation2017, Citation2020; Vansteenkiste, Ryan, & Soenens, Citation2020). In addition, relatedness includes individuals’ need to connect with entities or groups they value. When social or organisational contexts support their relatedness, individuals have a sense of connectedness and security (Ryan & Deci, Citation2017; Vansteenkiste, Ryan, & Soenens, Citation2020). When their need for relatedness is thwarted, people experience exclusion and social isolation (Vansteenkiste, Ryan, & Soenens, Citation2020).

When engagement in an activity helps individuals satisfy their BPNs and generates low/no frustration of them, people are likely to be intrinsically motivated to do this activity (i.e. to do it simply because they enjoy it). In contrast, when people have low levels of satisfaction and high levels of frustration of BPNs, they are likely to perceive tasks/activities as a means to an end and to be extrinsically motivated to engage in them (Ryan & Deci, Citation2017). Hence, satisfaction and frustration of BPNs significantly influence people’s behaviours, thoughts, and affective reactions (Ryan & Deci, Citation2017; Warburton, Wang, Bartholomew, Tuff, & Bishop, Citation2020). Consequently, satisfaction/frustration of basic needs might be related to the extent to which individuals perceive they accomplish their goals (including communication goals), feel confident about their abilities (e.g. to communicate effectively), and are satisfied (versus dissatisfied) with social encounters (e.g. with their communication with instructors).

Associations between communication factors and satisfaction/frustration of BPNs

Communication and motivation processes are tightly intertwined (Higgins, Citation2019; Hodis & Hodis, Citation2021). Nonetheless, not many studies have examined the associations between the communication factors we investigated and basic needs satisfaction/frustration. Below, we review the key findings of the relevant studies we identified.

Cronin et al. (Citation2019) reported medium to strong positive associations between an interpersonal communication skill factor (e.g. speaking clearly to others) and students’ satisfaction of all three basic needs. In this study, the three needs frustration dimensions were not significantly related to the interpersonal communication skill factor. Baker and Goodboy (Citation2019) found that students who received (versus did not receive) autonomy-supportive instruction had higher levels of oral participation (e.g. asking questions and follow-up questions in class).

Hodis and Hodis (Citation2021) investigated the interrelationships of three communication constructs with needs satisfaction/frustration. The communication constructs examined by these authors were self-perceived communication competence (SPCC), which is a measure of self-efficacy with regard to general communication, willingness to communicate (WTC), and communication apprehension (CA). Results from this research indicated that all three dimensions of needs satisfaction were inversely related to CA, which is a measure of anxiety/fear about oral communication (McCroskey, Citation1997). In addition, both autonomy and competence satisfaction had positive associations with WTC, which gauges a person’s tendency to initiate communication (McCroskey, Citation1997); the correlation between competence satisfaction and SPCC was also positive. Consistent results were unearthed with regard to needs frustration, where all three dimensions had positive correlations with CA. Moreover, both competence frustration and relatedness frustration had negative associations with SPCC; the magnitudes of all associations highlighted above were small to medium.

Taken together, findings from these studies suggest that satisfaction of BPNs is positively related to participating in communication encounters and feeling confident about how effectively one communicates. In contrast, frustration of BPNs is likely to be associated with elevated communication apprehension and low self-efficacy beliefs regarding communication.

Aims and research questions

A key strength of this research is that it investigates configurations of communication factors that are situated at different levels of generality. Specifically, students reported on the extent to which they achieve their communication goals; this is a measure that focuses on a specific domain of functioning, namely communication. The second factor, communication self-efficacy in school settings, is narrower than the first, as it centres on a single facet of the communicative domain, namely communication encounters that occur in school settings. The final factor, satisfaction in communicating with teachers, is even more narrow than the second, as it encompasses specific aspects of communication in learning settings (i.e. those with the instructor). Taken together, these three communication factors provide important information mapping the multiple interacting levels at which students communicate and appraise their corresponding goals, perceptions of ability, and satisfaction.

Uncovering latent groups associated with different combinations of these communication factors facilitates access to new information on both (a) the types of interrelationships among these factors; and (b) whether different subgroups – representing different configurations of communication factors – differ on the degree to which their psychological needs are satisfied/frustrated. For example, this approach could identify whether there exists a group of at-risk students for whom all three communication factors have (relatively) low values. If this is the case, the study could then ascertain whether, on average, students in this group have significantly higher (lower) levels of needs frustration (satisfaction) than students who exhibit different communication configurations.

The first aim of this study, was pursued by examining the first research question (RQ1): Is it possible to identify unobserved groups of students characterised by different configurations (patterns/profiles) of (i) achieving their communication goals, (ii) having confidence in their ability to communicate effectively in learning settings, and (iii) being satisfied in communicating with their course instructors? The second goal involved answering the second research question (RQ2): Do these latent groups significantly differ with regard to satisfaction and frustration of autonomy, competence, and relatedness?

Method

Participants

The research was approved by the Human Ethics committee of the university of the third author (Protocol Number 19175). Three hundred and seven students, who were enrolled in several sections of communication and kinesiology courses at a mid-size public university in the United States, participated in the research. These sections were taught face-to-face by several instructors. Students provided data by completing paper questionnaires during class time. They received no monetary compensation for their participation. Of the total number of respondents, 129 self-identified as female, 175 as male, two as other, and one participant did not provide this information. Seventy-eight students were in their first year, 58 were sophomores, 81 were juniors, and 90 were seniors. We did not collect any other demographic data.

Measures

The items were measured on a 1 (Strongly disagree) − 7 (Strongly agree) Likert scale. They were taken/adapted from measures that have showed appropriate validity and reliability in past research. Specifically, self-efficacy with regard to communicating in school settings (SCS, was gauged with four items from Barry and Finney (Citation2009) (see also Solberg, O’Brien, Villareal, Kennel, & Davis, Citation1993); an example item is ‘I am confident that I can talk to my professors’. To measure satisfaction in communication with teachers (SCT,

we used six items from Goodboy, Martin, and Bolkan (Citation2009); an example item is ‘My communication with my teacher feels satisfying’. Achievement of communication goals (ACG) was measured with one item (i.e. ‘I accomplish my communication goals’) from Rubin and Martin (Citation1994). Satisfaction and frustration of BPNs were measured with the subscales from Chen et al. (Citation2015); each subscale had four items. The reliabilities of these measures were as follows: autonomy satisfaction (ASA, e.g. ‘I feel my choices express who I really am’):

autonomy frustration (AFR, e.g. ‘My daily activities feel like a chain of obligations’):

competence satisfaction (CSA, e.g. ‘I feel capable at what I do’):

competence frustration (CFR, e.g. ‘I feel insecure about my abilities’):

relatedness satisfaction (RSA, e.g. ‘I feel that the people that I care about also care about me’):

relatedness frustration (RFR, e.g. ‘I feel the relationships I have are just superficial’):

Procedure

To answer RQ1 and RQ2, we conducted latent profile analysis (LPA). LPA is a statistical technique that enabled us to identify the unobserved groups characterised by different configurations/profiles with regard to the three communication factors (i.e. ACG, SCS, and SCT). In the LPA terminology, these groups are called (latent) classes. To determine the number of classes, we considered findings of methodological research and, thus, examined information from the statistical indexes listed in . Specifically, for AIC, BIC, and SABIC, lower values indicate a better model fit than higher values (Hodis, Hattie, & Hodis, Citation2017). ALRT and BLRT evaluate whether a model that has c-classes fits better than a simpler model, (i.e. a model that includes c−1 classes). When ALRT or BLRT has a significant p-value, this result provides support for retaining the more complex alternative. Entropy, which is measured on a 0–1 scale, suggests a smaller overlap (i.e. better separation) of classes when its value is closer to 1.

Table 1. Statistical information to determine the number of classes.

After we identified these latent classes (groups), we examined whether they significantly differed with respect to both satisfaction and frustration of BPNs. We conducted the LPAs in Mplus, version 8.2 (Muthén & Muthén, Citation2010), and employed full information maximum likelihood estimation with a robust estimator (i.e. FIML with MLR; Arbuckle, Citation1996; Muthén & Muthén, Citation2010). This enabled using all data, including incomplete data. We selected LPA over alternative methods for clustering data because it takes into account the uncertainty of classifying people into latent classes (Muthén & Muthén, Citation2010), which, in turn, leads to unbiased evaluations of the mean differences among classes with regard to the six BPNs satisfaction and frustration factors.

Results

In the first step of LPA we identified the number of latent classes (profiles) that underpin the associations among the three profile indicators (i.e. ACG, SCS, and SCT). Each profile indicator was calculated as the average value of the item(s) measuring the given communication factor. The descriptive statistics for the profile indicators are included in the bottom panel of .

Table 2. Descriptive statistics for each class and the total sample.

In line with current methodological recommendations and research practice (e.g. Harring & Hodis, Citation2016), the models we examined in this research included one through five latent classes, fixed at zero the covariances among the three indicators in each class and were otherwise unconstrained. A key goal of this research was to compare the latent classes identified with regard to the six basic psychological need satisfaction and frustration factors. However, extracting classes that have a small number of respondents classified to them makes such comparisons problematic (Hodis, Hattie, & Hodis, Citation2017). Therefore, we decided a priori that we will not consider solutions that involved classes having less than 15 participants. As the 5-class model had a very small class (i.e. n = 4; see ), we considered plausible only models that had between one and four classes.

As indicated in , AIC and SABIC values decreased whenever an additional class was extracted; thus, they were not useful in identifying the number of classes. BIC and BLRT supported a 3-class model, whereas ALRT supported the 2-class solution; entropy was also higher in this 2-class model than in the models with three or four classes.

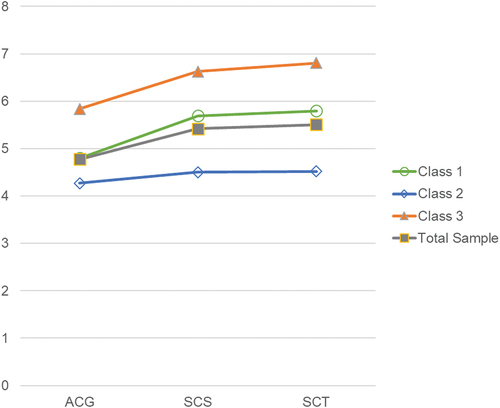

Examining the mean profiles of latent class indicators suggests that the 2-class model provides a coarse approximation of the data, as it misses a class whose profile mirrors the average patterns of the indicators (see Class 1 in ). Importantly, this ‘average class’ had the largest number of respondents of all classes enumerated in the 3-class solution. A comparison of the models with three and four classes reveals that the profile of indicators for one class in the 4-class model was very similar to that of a profile already enumerated in the 3-class model (i.e. Class 2 in ). Taking these aspects into consideration (and noting that BIC and BLRT supported this model), we concluded that three classes provide an optimal balance between appropriate modelling and parsimony. Importantly, for the 3-class model, the average (across respondents) probabilities of correct classification in latent classes were high or very high (i.e. .90 for Class 1 and Class 3; .80 for Class 2). These results, which suggest that the average probability of misclassifying participants was low or very low, further support retaining the 3-class model.

Figure 1. Latent profiles.

In the second step of LPA, we examined whether these three classes significantly differed with regard to the satisfaction/frustration of basic psychological needs. To do so, we used the three-step method (Vermunt, Citation2010) with the BCH setting of the AUXILIARY option of the VARIABLE command as implemented in Mplus (e.g. Asparouhov & Muthén, Citation2014, Citation2020; Bakk, Tekle, & Vermunt, Citation2013). Findings from several simulation studies (Asparouhov & Muthén, Citation2020; Bakk, Tekle, & Vermunt, Citation2013) support the appropriateness of this choice.

The mean indicator profiles corresponding to these three classes are included in ; the descriptive statistics of indicators in each class are reported in . Of the three classes, Class 1 had the largest number of participants, followed by Class 2 and Class 3 (see ). The pattern of indicators in Class 1 mirrored the configuration of their values in the total sample. In contrast, Class 2 had smaller values than Class 1 on all indicators (i.e. on ACG, SCS, and SCT). In Class 3, the mean values of all indicators were large or very large. The profiles for Class 1 and Class 3 had similar shapes, with mean values for SCT and SCS being comparable in strength and larger than the mean value of ACG. In Class 2, mean values of SCT and SCS were nearly indistinguishable, whereas the mean value of ACG was only slightly smaller.

In the next part of the analysis, we examined whether the three latent classes significantly differed with regard to the six basic psychological need satisfaction/frustration factors. The results of these analyses are reported in . For all three dimensions of need satisfaction, Class 3 had the largest mean value, followed by Class 1 and Class 2; all the differences among the three classes were statistically significant. The results for the three need frustration dimensions mirrored those for need satisfaction in that Class 3 had the lowest mean value, followed by Class 1 and Class 2. All the differences among classes were statistically significant for relatedness frustration. However, only Class 2 and Class 3 were significantly different for autonomy frustration, whereas both Class 1 and Class 2 were significantly different from Class 3 (but not from each other) for competence frustration.

Table 3. Mean, standard errors, and tests of significance for differences among classes in the self-determination factors.

Discussion

This research identified that three unobserved classes summarised well the patterns of association among attainment of communication goals, confidence about communicating in school settings, and satisfaction in communicating with course instructors. Of these groups, Class 3 reflected the most adaptive pattern of communication. Specifically, students in this class evaluated positively the extent to which they accomplished their communication goals, had strong self-efficacy beliefs with regard to communicating in learning settings, and reported very high levels of satisfaction with their course instructors. In contrast, students classified in Class 2 had much lower average values on all communication factors; this raised some questions about the extent to which they achieved their communication goals and communicated effectively. Class 1 mirrored the sample’s average pattern on these communication factors. Subsequent analyses revealed significant differences among these classes with regard to satisfaction and frustration of students’ autonomy, competence, and relatedness. The implications of these findings are discussed next.

Satisfaction of autonomy, competence, and relatedness supports appropriate functioning and goal attainment, whereas needs frustration leads to suboptimal functioning and ineffective pursuit of goals (Ryan & Deci, Citation2017). Results from this research are consistent with these tenets. Specifically, the communication profile that was associated with the strongest needs satisfaction and the weakest needs frustration (i.e. Class 3) exhibited very high levels of achievement of communication goals (see ). Notably, the communication literature suggests that there are strong links between communication goals people set and their communicative behaviours (Berger, Citation2002; Berger & Palomares, Citation2011; Dillard, Citation1997, Citation2004; Palomares, Citation2014; Wilson, Citation2002). Therefore, findings from this research suggest that settings and contexts that ensure satisfaction of basic psychological needs and minimize/eliminate their frustration might also help people achieve their communication goals. These results are consistent with findings reported by Cronin et al. (Citation2019), Baker and Goodboy (Citation2019), and Hodis and Hodis (Citation2021).

Self-efficacy with regard to communicating in school settings belongs to the conceptual family of self-efficacy constructs (Hodis & Hodis, Citation2012, Citation2013, Citation2015). Both self-efficacy and competence need satisfaction have effectiveness at their respective conceptual cores. That is, high values of both self-efficacy and competence need satisfaction reflect that an individual perceives herself/himself as being effective in interacting with her/his environment. Given this conceptual overlap, it is likely that strong satisfaction and weak frustration of the need for competence are associated with elevated self-efficacy beliefs. This is what we found in this research. Specifically, students classified in Class 3, who had the strongest self-efficacy with regard to communicating in school settings of the three classes uncovered, also reported the highest levels of autonomy, competence, and relatedness satisfaction as well as the lowest levels of need frustration of all classes. Moreover, and again consistent with both recent empirical research (e.g. Hodis & Hodis, Citation2021) and the needs satisfaction-frustration literature (Ryan & Deci, Citation2017), the findings illustrate that low satisfaction and high frustration of basic needs are associated with less adaptive communication patterns. In particular, students classified in Class 2, which had the lowest self-efficacy with regard to communicating in school settings, also had the smallest levels of needs satisfaction and the highest levels of needs frustration. These results suggest that the adaptiveness of communication patterns is supported by needs satisfaction and undermined by needs frustration.

What teachers do in learning settings significantly affects students’ satisfaction and frustration of BPNs (Baker & Goodboy, Citation2018; Goldman & Brann, Citation2016; Ryan & Deci, Citation2017). Importantly, past research findings (e.g. Baker & Goodboy, Citation2018; Goldman & Brann, Citation2016) suggest that teacher behaviour is related to all three dimensions of students’ BPNs (i.e. autonomy, competence, and relatedness). Moreover, in learning settings, SCT is an indicator of the extent to which students are satisfied with their interactions with instructors (e.g. Myers, Goodboy, & Members of COMM 600, Citation2014). Consistent with this past research, we found that SCT reflects the extent to which students’ BPNs are satisfied/frustrated. Specifically, students in Class 3, who had the strongest SCT of all classes, also reported the highest levels of autonomy, competence, and relatedness satisfaction and the lowest levels of need frustration. In contrast, students in Class 2, which had the weakest SCT of all classes, reported the lowest levels of need satisfaction and the highest levels of need frustration.

Mean differences between Class 3 (which illustrated effective patterns of communication) and Class 2 (which encapsulated less-than-optimal communication patterns) were large for all dimensions of needs satisfaction. These differences were of medium to large magnitude for the needs frustration dimensions. These results indicate that the distinct patterns of communication associated with Class 2 and Class 3 map onto meaningful differences in both satisfaction and frustration of basic psychological needs. These findings, which are consistent with results reported by Baker and Goodboy (Citation2019), Cronin et al. (Citation2019), and Hodis and Hodis (Citation2021), offer strong empirical support for arguing that communication and motivation processes are intertwined in meaningful and predictable ways (Higgins, Citation2019).

Implications for educational practice

Findings from this research have important implications for educational practice. Specifically, uncovering different communication profiles facilitates identifying distinct groups (typologies) of students who would benefit from different strategic approaches to communication instruction. For example, students in Class 2, whose profiles included low levels of achieving their communication goals, low confidence about communicating in learning settings, and low satisfaction in communicating with their teacher/instructor might require help with translating the course’s learning objectives into personal goals (e.g. to deliver strong oral presentations). In addition, these students may benefit from support to identify and set focused and feasible sub-goals that support the attainment of a loftier aim (e.g. appropriately modulate the tone of one’s voice and making consistent eye contact with the audience during an oral presentation). In addition, the teacher may have to ensure that carefully targeted and ample scaffolding is provided at each juncture point so that these students attain their sub-goals. This strategy is likely to be helpful for these students because when they make progress towards achieving their sub-goals, their confidence that they can achieve their main goal increases, along with their communication self-efficacy and sense of competence. In addition, achievement of sub-goals raises these students’ perceptions that their efforts are beneficial and, subsequently, their autonomous engagement with learning. Moreover, if students consider that the teacher’s help was instrumental in setting and achieving these sub-goals, their sense of relatedness might be strengthened as well. Thus, this instructional approach is likely to address not only these students’ suboptimal communication profile but also their underlying motivational vulnerabilities that are mediated by the low satisfaction and high frustration of their basic needs.

In contrast, students in Class 3, who had high levels of achievement of communication goals, strong self-efficacy regarding communication in learning settings, and were satisfied in communicating with their instructor, might be better served by communication instruction settings that provide much less scaffolding and, instead, offer them significant autonomy on how they achieve the learning objectives of the course. In addition, these students may benefit from being encouraged to adopt a broader lens when engaging with the course and enhancing their competence levels. To keep with the previous example, these students may be encouraged to identify which techniques of emotion management (both prior to and during the presentation) are most likely to help them raise the standard of their oral presentations. In turn, success in this endeavour is likely to lead to increased intrinsic motivation vis-à-vis the course (via low frustration and high satisfaction of their autonomy, competence, and relatedness).

Future directions of research

Consistent with the need satisfaction/frustration literature (Ryan & Deci, Citation2017, Citation2020; Vansteenkiste, Ryan, & Soenens, Citation2020), findings from this research suggest that communication instruction that (a) provides students with meaningful choices and is free of pressure (i.e. strengthens autonomy satisfaction and reduces autonomy frustration), (b) ensures a careful and well-balanced scaffolding and calibration of learning tasks (i.e. supports competence satisfaction and diminishes competence frustration), and (c) makes students feel understood, accepted, and valued in the learning community of the class/course (i.e. leads to relatedness satisfaction and prevents relatedness frustration) is likely to help students attain their communication goals, strengthen their communication skills and corresponding self-efficacy beliefs, and enhance their satisfaction in communicating with their teachers/instructors. Future research could profitably examine these hypotheses. Importantly, future studies could also work to identify key mechanisms and factors that mediate the relationships among need-supportive instruction, students’ needs satisfaction/frustration, and achievement of key communication outcomes (e.g. effective communication).

Limitations

This study bridges important gaps in current knowledge regarding the interplay of communication factors and basic needs; nonetheless, it has several limitations. First, although the sample size available for this research provided sufficient information to conduct the LPAs, we do not know whether larger sample sizes would uncover some additional latent classes. Second, the data analysed in this study do not allow us to make causal inferences. Finally, although we explored the associations between communication and motivation by examining constructs linked to a pivotal motivation theory (i.e. Self-Determination Theory; Ryan & Deci, Citation2017), our study did not capture the multifaceted nature of motivation. Hence, results reported here do not shed light on whether the groups underpinning the communication profiles uncovered in this research significantly differ with regard to constructs proposed by other influential motivation paradigms (e.g. prevention, promotion in Regulatory Focus Theory; Higgins, Citation2012; assessment and locomotion in Regulatory Mode Theory; Pierro, Chernikova, Lo Destro, Higgins, & Kruglanski, Citation2018).

Conclusion

This research found that three latent classes underpin the extent to which students achieve communication goals, feel confident about their communication in learning settings, and are satisfied in communicating with their instructors. Subsequent analyses revealed that students who had high levels of attaining communication goals, self-efficacy regarding communication in learning settings, and satisfaction in communicating with teachers also had the highest levels of all dimensions of needs satisfaction and the lowest levels of needs frustration. In contrast, students who exhibited a less optimal communication profile (i.e. had much lower levels on these communication factors), had the weakest needs satisfaction and the strongest needs frustration. These findings provide important new information on how communication and motivation interact in meaningful ways (Higgins, Citation2019).

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful for the very useful feedback received from the editor and two anonymous reviewers on an earlier version of this article.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Arbuckle, J. L. (1996). Full information in the presence of incomplete data. In G. A. Marcoulides & R. E. Schumacker (Eds.), Advanced structural equation modeling: Issues and techniques (pp. 243–277). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Asparouhov, T., & Muthén, B. O. (2014). Auxiliary variables in mixture modeling: Three-step approaches using Mplus. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 21(3), 329–341. doi:10.1080/10705511.2014.915181

- Asparouhov, T., & Muthén, B. O. (2020). Auxiliary variables in mixture modeling: Using the BCH method in Mplus to estimate a distal outcome model and an arbitrary second model. Mplus Web Notes: No. 21. 2014, May 14. Revised 2020, April 27.

- Baker, J. P., & Goodboy, A. K. (2018). Students’ self-determination as a consequence of instructor misbehaviors. Communication Research Reports, 35(1), 68–73. doi:10.1080/08824096.2017.1366305

- Baker, J. P., & Goodboy, A. K. (2019). The choice is yours: The effects of autonomy-supportive instruction on students’ learning and communication. Communication Education, 68(1), 80–102. doi:10.1080/03634523.2018.1536793

- Bakk, Z., Tekle, F. B., & Vermunt, J. K. (2013). Estimating the association between latent class membership and external variables using bias-adjusted three-step approaches. Sociological Methodology, 43(1), 272–311. doi:10.1177/0081175012470644

- Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. Freeman.

- Barry, C. L., & Finney, S. J. (2009). Can we feel confident in how we measure college confidence? A psychometric investigation of the college self-efficacy inventory. Measurement and Evaluation in Counseling and Development, 42(3), 197–222. doi:10.1177/0748175609344095

- Berger, C. R. (2002). Goals and knowledge structures and social interaction. In M. L. Knapp & J. A. Dally (Eds.), Handbook of interpersonal communication (3rd ed., pp. 181–212). Sage.

- Berger, C. R., & Palomares, N. A. (2011). Knowledge structures and social interaction. In M. L. Knapp & J. A. Dally (Eds.), The Sage handbook of interpersonal communication (4th ed., pp. 169–200). Sage.

- Chen, B., Vansteenkiste, M., Beyers, W., Boone, L., Deci, E. L. … Verstuyf, J. (2015). Basic psychological need satisfaction, need frustration, and need strength across four cultures. Motivation and Emotion, 39(2), 216–236. doi:10.1007/s11031-014-9450-1

- Cronin, L., Marchant, D., Allen, J., Mulvenna, C., Cullen, D., Williams, G., & Ellison, P. (2019). Students’ perceptions of autonomy-supportive versus controlling teaching and basic need satisfaction versus frustration in relation to life skills development in PE. Psychology of Sport & Exercise, 44, 79–89. doi:10.1016/j.psychsport.2019.05.003

- Dillard, J. P. (1997). Explicating the goal construct: Tools for theorists. In J. O. Greene (Ed.), Message production: Advances in communication theory (pp. 47–70). Erlbaum.

- Dillard, J. P. (2004). The goals-plans-action model of interpersonal influence. In J. S. Seiter & R. H. Gass (Eds.), Perspectives on persuasion, social influence, and compliance gaining (pp. 185–206). Allyn & Bacon.

- Frisby, B. N., & Martin, M. M. (2010). Instructor-student and student-student rapport in the classroom. Communication Education, 59(2), 146–164. doi:10.1080/03634520903564362

- Frymier, A. B., & Houser, M. L. (1999). The revised learning indicators scale. Communication Studies, 50(1), 1–12. doi:10.1080/10510979909388466

- Goldman, Z. W., & Brann, M. (2016). Motivating college students: An exploration of psychological needs from a communication perspective. Qualitative Research Reports in Communication, 17(1), 7–14. doi:10.1080/17459435.2015.1088890

- Goodboy, A. K., Martin, M., & Bolkan, S. (2009). The development and validation of the student communication satisfaction scale. Communication Education, 58(3), 372–396. doi:10.1080/03634520902755441

- Harring, J. R., & Hodis, F. A. (2016). Mixture modeling: Applications in educational psychology. Educational Psychologist, 51(3–4), 354–367. doi:10.1080/00461520.2016.1207176

- Hecht, M. L. (1978a). The conceptualization and measurement of interpersonal communication satisfaction. Human Communication Research, 4(3), 253–264. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2958.1978.tb00614.x

- Hecht, M. L. (1978b). Measures of communication satisfaction. Human Communication Research, 4(4), 350–368. doi:10.1111/j.1468–2958.1978.tb00721.x

- Higgins, E. T. (2012). Beyond pleasure and pain: How motivation works. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199765829.001.0001

- Higgins, E. T. (2019). Shared reality: What makes us stronger and tears us apart. Oxford University Press.

- Hodis, F. A., Hattie, J. A. C., & Hodis, G. M. (2017). Investigating student motivation at the confluence of multiple effectiveness strivings: A study of promotion, prevention, locomotion, assessment, and their interrelationships. Personality and Individual Differences, 109, 181–191. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2017.01.009

- Hodis, F. A., & Hodis, G. M. (2015). Expectancy, value, promotion, and prevention: An integrative account of regulatory fit vs. non-fit with student satisfaction in communicating with teachers. Annals of the International Communication Association, 39(1), 339–370. doi:10.1080/23808985.2015.11679180

- Hodis, G. M., & Hodis, F. A. (2012). Trends in communicative self-efficacy: A comparative analysis. Basic Communication Course Annual, 24, 40–80.

- Hodis, G. M., & Hodis, F. A. (2013). Static and dynamic interplay among communication apprehension, communicative self-efficacy, and willingness to communicate in the basic communication course. Basic Communication Course Annual, 25, 70–125.

- Hodis, G. M., & Hodis, F. A. (2021). Examining motivation predictors of key communication constructs: An investigation of regulatory focus, need satisfaction, and need frustration. Personality and Individual Differences, 180, Article 110985. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2021.110985

- Koesten, J., Miller, K. I., & Hummert, M. L. (2002). Family communication, self- efficacy, and white female adolescents’ risk behavior. Journal of Family Communication, 2(1), 7–27. doi:10.1207/S15327698JFC0201_3

- Li, R., Chen, Y., Liu, H., & Yao, M. (2020). Need satisfaction and frustration profiles: Who benefits more on social networking sites? Personality and Individual Differences, 158, Article 109854. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2020.109854

- Martin, M. M., Mottet, T. P., & Myers, S. A. (2000). Students’ motives for communicating with their instructors and affective and cognitive learning. Psychological Reports, 87(3), 830–834. doi:10.2466/pr0.2000.87.3.830

- Martin, M. M., Myers, S. A., & Mottet, T. P. (1999). Students’ motives for communicating with their instructors. Communication Education, 48(2), 155–164. doi:10.1080/03634529909379163

- McCroskey, J. C. (1997). Willingness to communicate, communication apprehension, and self-perceived communication competence. In J. A. Daly, J. C. McCroskey, J. Ayres, T. Hopf, & D. M. Ayres (Eds.), Avoiding communication: Shyness, reticence, and communication apprehension (2nd ed., pp. 75–108). Hampton Press.

- Mottet, T. P., Martin, M. M., & Myers, S. A. (2004). Relationships among perceived instructor verbal approach and avoidance relational strategies and students’ motives for communicating with their instructors. Communication Education, 53(1), 116–122. doi:10.1080/0363452032000135814

- Muthén, L. K., & Muthén, B. O. (2010). Mplus user’s guide (6th ed.). Los Angeles: Muthén & Muthén.

- Myers, S. A., Goodboy, A. K., & Members of COMM 600. (2014). College student learning, motivation, and satisfaction as a function of effective instructor communication behaviors. Southern Communication Journal, 79(1), 14–26.

- Myers, S. A., Martin, M. M., & Mottet, T. P. (2002a). The relationship between student communication motives and information seeking. Communication Research Reports, 19(2), 352–361. doi:10.1080/08824090209384863

- Myers, S. A., Martin, M. M., & Mottet, T. P. (2002b). Students’ motives for communicating with their instructors: Considering instructor socio-communicative style, student socio-communicative orientation, and student gender. Communication Education, 51(2), 121–133. doi:10.1080/03634520216511

- Palomares, N. A. (2013). When and how goals are contagious in social interaction. Human Communication Research, 39(1), 74–100. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2958.2012.01439.x

- Palomares, N. A. (2014). The goal construct in interpersonal communication. In C. R. Berger (Ed.), Interpersonal communication (pp. 77–99). De Gruyter.

- Pierro, A., Chernikova, M., Lo Destro, C., Higgins, E. T., & Kruglanski, A. W. (2018). Assessment and locomotion conjunction: How looking complements leaping … but not always. In J. M. Olson (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 58, pp. 243–299). Academic Press. doi:10.1016/bs.aesp.2018.02.001

- Rubin, R. B., & Martin, M. M. (1994). Development of a measure of interpersonal communication competence. Communication Research Reports, 11(1), 33–44. doi:10.1080/08824099409359938

- Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2016). Facilitating and hindering motivation, learning, and well-being in schools: Research and observations from self-determination theory. In K. R. Wentzel & D. B. Miele (Eds.), Handbook of motivation of school (2nd ed., pp. 96–119). Routledge.

- Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2017). Self-determination theory: Basic psychological needs in motivation, development, and wellness. Guilford. doi:10.1521/978.14625/28806

- Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2020). Intrinsic and extrinsic motivation from a self-determination theory perspective: Definitions, theory, practices, and future directions. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 61, Article 101860. doi:10.1016/j.cedpsych.2020.101860

- Solberg, V. S., O’Brien, K., Villareal, P., Kennel, R., & Davis, B. (1993). Self-efficacy and Hispanic college students: Validation of the College self-efficacyinstrument. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 15(1), 80–95. doi:10.1177/07399863930151004

- Teven, J. J., & McCroskey, J. C. (1997). The relationship of perceived teacher caring with student learning and teacher evaluation. Communication Education, 46(1), 1–9. doi:10.1080/03634529709379069

- Vansteenkiste, M., Ryan, R. M., & Soenens, B. (2020). Basic psychological need theory: Advancements, critical themes, and future directions. Motivation and Emotion, 44(2), 1–31. doi:10.1007/s11031-019-09818-1

- Vermunt, J. K. (2010). Latent class modeling with covariates: Two improved three-step approaches. Political Analysis, 18(4), 450–469. doi:10.1093/pan/mpq025

- Voelkl, K. E. (1995). School warmth, student participation, and achievement. Journal of Experimental Education, 63(2), 127–139. doi:10.1080/00220973.1995.9943817

- Warburton, V. E., Wang, J. C., Bartholomew, K. J., Tuff, R. L., & Bishop, K. C. M. (2020). Need satisfaction and need frustration as distinct and potentially co-occurring constructs: Need profiles examined in physical education and sport. Motivation and Emotion, 44(1), 54–66. doi:10.1007/s11031-019-09798-2

- Wilson, S. R. (2002). Seeking and resisting compliance: Why people say what they do when trying to influence others. SAGE Publications, Inc. doi:10.4135/9781452233185