ABSTRACT

Entertainment-Education interventions can be influential communication strategies to help facilitate audiences to live more sustainable lifestyles. Understanding the process of influencing viewers’ behaviour is essential to further design and enhance Entertainment-Education interventions. This current research uses focus groups to explore the role the first season of the Australian Broadcasting Corporation’s television series, War on Waste, played in encouraging an uptake in reusable coffee cup behaviour in Melbourne’s millennial generation (people born between 1982 and 2000). The results indicate the investigative style, local context and joint-learning experience were all elements that promoted reusable coffee cup behaviour. Millennials described this behaviour as being more widely adopted – compared to other behaviours shown in War on Waste – because it aligned with their lifestyles, was considered ‘easy’ and projected their environmental values. This case study aims to provide practitioners with a useful framework that can be applied to broader Anthropogenic issues to generate behaviour change at scale.

Introduction

Globally, there is a large range of significant environmental and sustainability crises that need urgently addressing in the Anthropocene (DESA, Citation2022). There are several root causes of the triple planetary crises of climate change, biodiversity loss and pollution, one of which is the unsustainable pattern of consumption and production (DESA, Citation2022, p. 50). A key element of this is due to consumption behaviour in the industrialised world reaching an unsustainable point, largely due to the number of materials and energy products demand (Cooper, Citation2016). One key way to overcome this is by developing waste reduction behaviours (DESA, Citation2022). Waste disposed in landfills leads to significant environmental issues such as the contamination of soil, water and air which can have disastrous consequences on human health (Ferdous et al., Citation2021).

Many consumer products are increasingly sold in ‘disposable’ forms driven by convenience and hygiene, including disposable pens, razors and nappies (Cooper, Citation2016). This increased dramatically during COVID-19, where in the first year it is estimated that 3.5 million tonnes of masks might have been sent to landfill (Silva, Prata, Duarte, Barcelò, & Rocha-Santos, Citation2021). It is predicted that global solid-waste generation will almost double to more than 6 million tonnes per day in 2025, compared to 3.5 million tonnes per day in 2010 (United Nations Environment Programme & International Waste Management Association, Citation2015).

In trying to find a solution to this issue, one school of thought is ‘technophilic optimism’, which is the belief that technology will save us from the repercussions of overconsumption of waste (Mitchell, Citation2012). In particular, science and technology are expected to make products smaller, lighter and more resource efficient in order to decrease waste (Hoornweg, Bhada-Tata, & Kennedy, Citation2013). However, this belief allows the everyday consumer to feel less responsible and accountable for their actions, leading to no change in behaviour and thus continued overconsumption of waste. The technology-centred approach is insufficient to address environmental problems on its own because it does not enact and implement the policies and behaviours required to address the human-centred challenges such as population, affluence, and consumption (Mitchell, Citation2012). Therefore, advances in science and technology must be combined with other schools of thought such as broader societal changes across public policy, marketing strategies, and socio-cultural norms to drive behaviour change and encourage sustainable consumption (Bujold, Williamson, & Thulin, Citation2020; Cooper, Citation2016; Gwozdz, Reisch, & Thøgersen, Citation2020; Klöckner, Citation2015; Mitchell, Citation2012). Sustainable consumption is defined as:

the use of goods and services that respond to basic needs and bring a better quality of life, while minimising the use of natural resources, toxic materials and emissions from waste and pollutants over the life cycle, so as not to jeopardise the needs of future generations. (UNCSD, Citation1994, p. 1)

Part of sustainable consumption involves actively engaging members of society, to help them to not only minimise material consumption, but to also create public discussion that can lead to changes in behaviour (Reinermann, Lubjuhn, Bouman, & Singhal, Citation2014).

Entertainment-Education interventions

One way to create public discussion is through Entertainment-Education interventions; a communications strategy that has been used all over the world to change attitudes, behaviours, and social norms (Singhal, Michael, Rogers, & Sabido, Citation2003). Wang and Singhal (Citation2021) define Entertainment-Education as a ‘social and behavioural change communication (SBCC) strategy that leverages the power of storytelling in entertainment and wisdom from theories in different disciplines – with deliberate intention and collaborative efforts throughout the process of content production, program implementation, monitoring, and evaluation – to address critical issues in the real world and create enabling conditions for desirable and sustainable change across micro-, meso-, and macro-levels’.

Entertainment-Education is rooted in social change communication theory and has been used to disseminate messages and ideas that lead to behavioural and social change, particularly around health issues (Green, Citation2021; Singhal & Rogers, Citation2002; Singhal, Wang, & Rogers, Citation2013). For instance, the Entertainment-Education strategy which originated in campaigns in Tanzania, South Africa and India (Khalid & Ahmed, Citation2014; Reinermann, Lubjuhn, Bouman, & Singhal, Citation2014) initially focused on reproductive health issues, family planning, and HIV prevention (Singhal & Rogers, Citation2002). This has now been expanded into other areas such as COVID-19 public health information campaigns for children (Keys, Citation2021), domestic violence (Peirce, Citation2011; Singhal, Wang, & Rogers, Citation2013; Yue, Wang, & Singhal, Citation2019), wildlife conservation (Baker, Jah, & Connolly, Citation2018), agricultural development practices (Singhal, Wang, & Rogers, Citation2013), environmentally-sound farming methods (Heong et al., Citation2008) and sustainable waste management activities (Reinermann, Lubjuhn, Bouman, & Singhal, Citation2014).

Entertainment-Education interventions are a popular form of mass-media communication, and have been disseminated through television, radio, film, print, theatre and music (Singhal, Michael, Rogers, & Sabido, Citation2003; Singhal, Wang, & Rogers, Citation2013). Due to its success in addressing an array of social issues (Singhal & Rogers, Citation2002), Entertainment-Education strategies have potential to promote sustainable lifestyles (Reinermann & Lubjuhn, Citation2012; Reinermann, Lubjuhn, Bouman, & Singhal, Citation2014; Singhal & Rogers, Citation1999).

The need for behaviour change in sustainable consumption

Sustainable waste management can be reduced to a set of human behaviours, however currently there is a disconnect between peoples’ sustainability values and their aligned actions. Whilst it has been found that consumers are increasingly concerned about the pollution and health effects of product consumption (OECD, Citation2008), numerous studies highlight that consumers lack an understanding of how their actions contribute to major environmental issues (Klöckner, Citation2015; Reinermann, Lubjuhn, Bouman, & Singhal, Citation2014). This dichotomy is also seen within Australia: 76% of Australians are motivated to minimise waste going to landfill (Cleanaway Waste Management Limited, Alt/Shift., & Empirica Research, Citation2022), yet as a nation Australia has been found to generate more waste than the average Western economy (Pickin, Randell, Trinh, & Grant, Citation2018). This gap between concern and action is further demonstrated in 86% of Australians believing that, as a nation, waste production needs to be reduced, yet only 50% of households are trying to personally reduce waste (Barnfield & Marks, Citation2018). Therefore, whilst the concern for environmental issues exists, there is a strong need to focus on facilitating individual and societal level behaviour change.

A holistic approach to Entertainment-Education interventions

Entertainment-Education interventions have evolved to be a powerful tool to facilitate this behavioural and social change. In the past, Entertainment-Education interventions have been over-simplified by focusing on the individual in isolation from their broader context (Singhal, Citation2008). However, the new approach has shifted towards understanding the multiple levels of context in which an Entertainment-Education intervention sits. This includes understanding and incorporating political structures, cultural and social norms, linguistic diversity, attitudes, and lifestyles of audiences, in order to achieve the desired social change (Chirinos-Espin, Citation2021; Reinermann, Lubjuhn, Bouman, & Singhal, Citation2014; Singhal, Citation2008).

The more tailored an intervention is to its audience, the more engagement and therefore impact it is likely to have. Conducting background research can create further impact by addressing the target audiences’ specific barriers to change (Sweeney, Citation2009). Another way to tailor interventions is to embed familiar artefacts that serve as reminders of the audiences’ own lifestyles (Peirce, Citation2011). This idea is reinforced by the cultural proximity concept (Straubhaar, Citation1991) which highlights the tendency to prefer media products from an individual’s own culture, or the culture that is most similar. However, further research is needed to understand the path to impact in more detail and across more contexts.

The current study

The current study seeks to further knowledge in this field by investigating the role that Entertainment-Education interventions can play in promoting sustainable behaviours using a case study of reusable coffee cups in Melbourne’s millennial generation. While Australians are motivated to minimise waste going to landfill (Cleanaway et al., Citation2022), like other industrialised countries in more recent decades, there has been an increase in the amount of waste produced by the nation due to consumerism, supermarket policies and apathy (ABC, Citation2018b).

To address unsustainable consumption in Australia, the Australian Broadcasting Corporation (ABC) (Australia’s major public broadcaster), aired a four-part television series about Australia’s consumer culture, War on Waste, with season one airing 16, 23 and 30 May 2017, with a follow-up episode 3 December 2017. Each episode was an hour long. The first season reached 3.7 million viewers in Australia and was hosted by Craig Reucassel, as he took a critical and first-hand look at household, retail and farming waste in Australia (Kentera, Citation2017). The episodes followed Reucassel as he visited supermarkets, spoke to Australians about living waste-free, and investigated Australia’s recycling industry (Kentera, Citation2017). It used a multi-faceted digital approach across many ABC media platforms, including podcasts, the ABC app, an online program landing page, the ABC website, linked educational resources and social media. A second season was produced and aired in July 2018 with an audience of 3.3 million viewers. The broader impact of season one and two was evaluated by Downes, Williams, Calder, and Dominish (Citation2019) focusing on the system level impacts across public, private and community sectors.

Individual attitudes and behaviours relating to waste, however, were specifically evaluated in season one by the ABC through a three-month survey. The survey was launched on 19 April 2017 (four weeks before War on Waste aired) and ended on 31 July 2017 (eight weeks after War on Waste aired). A comparison of those who responded before and after season one was used to inform how respondents changed their behaviour in response to specific issues presented in the program (Barnfield & Marks, Citation2018). A total of 36,722 Australians completed the survey, making it one of Australia’s largest studies on waste (Barnfield & Marks, Citation2018). The survey asked respondents to self-assess their environmental behaviours over the previous three months and found that millennials (defined as 18- to 34-year-olds) produce more waste and partake in more unsustainable behaviours in their households compared to other generations. However, there was one behaviour that showed millennials outperforming all other age groups after viewing season one: purchasing a takeaway coffee in a bring-your-own (BYO) reusable coffee cup instead of a disposable coffee cup. Of the 18 to 34-year-old respondents, 36.5% purchased coffee in a BYO reusable coffee cup after the show aired, compared to 26% of respondents in all age groups above 35 years.

Research suggests that War on Waste may have played a significant role in millennials’ adoption and maintenance of the BYO reusable cup for two main reasons (Barnfield & Marks, Citation2018). Firstly, before War on Waste aired, 46% of millennials thought that disposable coffee cups could be recycled in Australia’s current recycling system – however, they cannot be recycled because of the layer of thin plastic lining inside. The survey results indicate a decrease to 34% after viewing War on Waste, suggesting that audience learning occurred as a result. Secondly, there was a 400% increase in KeepCup sales, (a brand of BYO reusable coffee cup promoted in War on Waste) within a week after the third episode aired (Powell, Citation2017). These two findings suggest War on Waste may have clarified the facts about disposable coffee cups and raised awareness about a potential solution to the problem: buy and use BYO coffee cups.

War on Waste was designed to influence these specific behaviours. The aim of this current research was to understand the principles and strategies that led to the behavioural impacts found within the audience in season one to provide future recommendations when designing Entertainment-Education interventions.

Method

The first author conducted two one-hour semi-structured focus groups, which aimed to examine the role that War on Waste played in the adoption and maintenance of BYO coffee cup use in Melbourne’s millennial generation. Ethics approval was obtained from College Human Ethics Advisory Network at RMIT University (Project number: CHEAN A 0000020300–06/16), which meets the requirements of the National statement on ethical conduct in human research. There were four participants in the first focus group and three participants in the second. A search among Melbourne’s millennial generation was conducted through various Facebook groups and pages: Zero Waste, universities in Melbourne, community groups, sustainability-focused cafés, and farmer’s market groups. The participants were asked to contact the researcher via email or Facebook Messenger to participate in the study. Participants needed to be born between 1982 and 2000, must have watched the first season of ABC’s War on Waste, and must have been available to participate in a one-hour face-to-face focus group session at RMIT University’s Melbourne city campus (and subsequently all participants lived in the Greater Melbourne area). The gender ratio was heavily skewed towards females (n = 6) compared with males (n = 1). This could be due partly to the recruitment channels, for instance, a Facebook page called Responsible Cafes which was used to recruit participants, confirmed the demographic of their page was skewed to 80% females out of their 17,839 followers (Responsible Cafes, Citation2018, pers. comm.)

Women were also over-represented in both the War on Waste survey respondents (70%, n = 36,792) and War on Waste viewers (55%); when women make up 51% of the Australian population (Barnfield & Marks, Citation2018). This over-representation of women is consistent with research that has shown that women are more likely to partake in behaviours that relate to using green products (like a reusable coffee cup) (Fisher, Bashyal, & Bachman, Citation2012), including showing greater positive intention for green consumption and more frequent purchase of green products (Zhao, Gong, Li, Zhang, & Sun, Citation2021). Therefore, it is not surprising that female participants were over-represented in this study focused on sustainable consumption.

This study defined millennials as people born between 1982 and 2000 for two reasons. Firstly, to align as closely as possible with the War on Waste survey millennial respondents which were 18 to 35-year-olds in 2017; and secondly to align with academic literature about millennials which generally accepts this age group as being born between these years. Focus group sessions were recorded with an audio device, and later transcribed.

The research aimed to investigate the following:

What elements of War on Waste (i.e. tone, style or medium) resonated with Melbourne’s millennial generation?

Why did Melbourne millennials adopt using KeepCups at higher rates than other environmental behaviours shown in War on Waste?

What is motivating Melbourne’s millennial generation to keep using the KeepCup?

These research questions provided a guide for the semi-structured interview questions. A full list of the interview questions is listed in Appendix 1. The interviews explored which elements of War on Waste resonated with Melbourne’s millennial generation, their motivation for watching the show, flow-on behavioural effects after watching War on Waste, and questions about the adoption and maintenance of reusable coffee cups, particularly around decision-making processes, and cost-benefit analyses. The questions became more complex throughout the focus group and aimed to uncover why millennials adopted reusable coffee cups more than other pro-environmental behaviours. A key part of this question was around the perceived barriers of using a reusable coffee cup, to understand whether this audience was likely to continue use.

Using NVivo software, a content and thematic analysis was conducted to identify, analyse and report patterns (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006) within focus group data, guided by the three research questions. The analysis began with importing transcribed data from the focus groups into NVivo, which drew out early insights into emerging themes via the word frequency tool. Careful analysis was taken to ensure that evidence of these emerging themes was found in various participants’ (not just one) who articulated the theme across the entire data set, as described as an important practice in thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006). From there, the word search query was used to review key terms in NVivo that were specific to the three research questions. When reviewing these key terms, the relevant data was then ‘coded’, which involved assigning categorical codes to aid in the qualitative data analysis process (Miles & Huberman, Citation1994). During the word search query, the level or specificity of coding was adjusted by modifying the variance of synonyms to increase or decrease scope to encompass and refine all relevant data. Through this iterative process, key terms or codes were finessed and grouped via research question, then analysed based on relevant theories.

Results

Through analysing the interview data, we identified a range of strategies and processes that appeared to shift the participant and viewer sample towards adopting use of the KeepCup, which we discuss in greater detail below using participant quotes as examples. These findings have been summarised and synthesised into as key lessons that can be applied more broadly by Entertainment-Education practitioners to help facilitate impact in viewer behaviour.

Style and tone of War on Waste

What elements of War on Waste resonated most with Melbourne’s millennial generation? Focus group results suggested that the host of the series, Craig Reucassel, played an important part in initially motivating participants to watch War on Waste. Reucassel is an Australian television personality known for his provocative and engaging style from The Chaser, a satirical comedy group known for their television series on the ABC (Citation2018a). Three participants felt that Reucassel made the issue of waste engaging, by engaging in memorable and unexpected stunts, like in The Chaser:

My favourite thing about the show was all the stunts that Craig pulled—it’s classic Chaser stuff. Like the big rolling ball of plastic bags and the tram full of coffee cups. I thought that aspect of it was the most hard hitting and interesting.

When asked about the tone of War on Waste, focus group participants felt as though season one had adopted a similar tone to The Chaser, which had a good balance of being entertaining, yet educational, but also not too dull or depressing. The first season unveiled Australia’s issue of waste in a simple way and provided solutions for the Australian public that could be tackled at the individual level. One participant could not recall whether there was ‘much science’ in season one, demonstrating that if there was, it was either very simple, or woven into the entertaining elements:

I think he [Craig Reucassel] takes a very simple everyday task and he basically debunks it in a very lay and easy way to understand. I am trying to think if there was much science in it. I don’t think there was, it was all pretty simple. It’s just unveiling, that’s it.

In addition to the provocative style of War on Waste, participants agreed that the first season did well to shine light on a topic that Australians may not have previously understood. Two participants described this as gaining insight ‘behind the scenes’ of Australia’s waste problem, and demonstrated how our everyday actions contribute to bigger environmental issues:

I really liked the stunts as well because you got to see the effects of your behaviour. When I’m throwing out a coffee cup, I don’t see what happens to it – out of sight out of mind, kind of thing.

I think it really unveiled all the layers behind the waste industry and sheds light on something that ideally a garbage man just whisks away from us without us having to know or understand why, and where it goes.

On numerous occasions, and in both focus groups, participants described the stunts in War on Waste as visually-provoking and confronting. The stunts involved rolling a big ball of plastic bags onto the steps of Parliament House in Melbourne, standing on a mound of wasted misshapen bananas, filling a tram with disposable coffee cups, and creating a mound of clothes in Sydney’s Martin Place. One participant felt as though the show’s confronting visuals were enough on their own to inspire people who would not normally care about the environment to take action:

It was just horrifying enough I think a lot of people changed, they got KeepCups after watching it [War on Waste], and I thought even people you wouldn’t usually expect to care about environmental things. Just the visual component of it was horrifying.

All focus group participants agreed that the local geographical context of Australia, and more specifically Melbourne, was exciting to see in a television series. One participant thought it was refreshing to see a series that highlighted local rules and policies that were relevant to Australia, instead of overseas content related to Europe or the USA. All participants agreed that the local context and ‘close to home’ factor of the first season generated an initial interest in watching the show:

I think what was really great about War on Waste is it showed Melbourne and it had the tram, and Parliament. They had the plastic bags at Parliament, and they had the coffee cups in the tram… I thought that was quite well done.

When asked about the tone in season one, participants felt like they were not being preached at, or told what do to in War on Waste. Two participants attributed this to the fact that, as a viewer, you felt like you had an equal footing with the host and were learning with him. Similarities were drawn between Louis Theroux's documentary style – a British documentary filmmaker and broadcaster – and War on Waste because of their similarity in the joint learning experience between the host and viewer. One participant felt that War on Waste was very relatable to the everyday Australian, because Reucassel did not position himself as an expert on the topic, but instead as someone simply trying to unpack Australia’s issue of waste:

A lot of films, they’ve been good, and they’ve been eye opening, but they feel very preachy. It’s often either an expert, or just a narrator, who clearly didn’t know anything about the topic beforehand, who has now researched things, who is telling you things. Whereas in the case of the War on Waste, it felt more like he [Craig] was learning it with you, at the same time.

War on Waste and behaviour change

How did watching War on Waste translate to the audience changing their behaviour? One participant felt like season one made it very clear to the viewer about how they could combat Australia’s waste issue, by explicitly outlining a very clear path of adoptable behaviours. In line with the ‘joint learning experience’ described above, the show not only showed Reucassel learning about Australia’s waste issue but showed him taking action in response to what he learnt. The show follows Reucassel’s journey facing challenges and overcoming them, to eventually changing his behaviour:

It kind of follows the full cycle that viewers are to experience – learn the shocking facts, attempt to alter behaviour, hit some barriers along the way. Depending on the person, they may overcome the barrier, or revert to original behaviour. But seeing others experience similar barriers and overcoming them over the course of the show may be just enough motivation for viewers to do the same.

Many participants felt that War on Waste provided a groundswell that inspired (or re-inspired) them to take environmental action. Two participants were unaware of Australia’s waste issue before the show but became inspired to take environmental action for the first time after watching the show. One participant described themselves as environmentally conscious before season one aired and felt re-inspired after watching to take more political action, because the issue of waste had become more mainstream. The same participant explained that because the show targeted supermarkets, as well as the consumer, it felt like more change was occurring:

I really enjoyed how it was a mix of personal actions but more systemic changes that they tried to promote, so things like getting Coles and Woolworths to change cosmetic standards but also the episode with the fast fashion, about getting the teenage girls to consider their own personal choices. It was nice to see both aspects of that from individual moves which are usually the focus, to actually lobbying politicians.

War on Waste shone light on commonly misunderstood environmental behaviours, including the fact that disposable coffee cups are unable to be recycled in Australia’s current recycling system. Two focus group participants thought disposable coffee cups were recyclable before War on Waste aired, but upon finding out that coffee cups could not be recycled, changed their behaviour:

Before the show [War on Waste] I thought coffee cups were recyclable, but they’re not. I’m not a big coffee drinker, occasionally I have hot chocolates, but I thought, because they’re recyclable, it doesn’t really matter what I’m doing. So then after the show I decided to get a KeepCup.

The uptake of reusable coffee cups, over other pro-environmental behaviours

What made the reusable coffee cup behaviour so successfully adopted among Melbourne’s millennial generation, compared to other pro-environmental behaviours? One participant simply summarised the answer as, ‘it’s just so easy. You just buy a Keep Cup’. This statement also sums up the consensus of the group: at an individual level, you can easily solve the disposable coffee cup waste issue by buying a reusable coffee cup. Other pro-environmental behaviours seemed like too much effort, and had too many new steps to learn:

The substitution of having a disposable coffee cup versus a KeepCup, is a very quick learning curve. Whereas people in our [Masters of Environment] bubble would be very willing to do that long term behaviour change and learn how to compost because we think it’s really worthwhile. But for people who aren’t in our bubble, it takes a bit more effort.

Another participant explained that other, more ‘difficult’ environmental behaviours may also be unfeasible for millennials, because of limitations such as living arrangements or lack of space:

I think a lot of millennials are living in share house environments, apartment living, or university accommodation, so the ability to even have a compost or a worm farm, chickens, is limited. My KeepCup is just an easy band-aide approach that is the easiest thing to do.

Three participants agreed that when they see other people holding reusable coffee cups, they associate them as being environmentally conscious. This suggests that the reusable coffee cup has become an expression of identity. Focus group participants thought that using a reusable coffee cup is an easy way – compared to something more time-consuming like composting – to make a person feel like they are doing something good for the environment:

I think it’s just a trendy, convenient way to maybe look and feel like you are doing something that’s in the right step.

In addition to this expression of identity, other participants described using reusable coffee cups as being a very visible pro-environmental behaviour compared to behind-the-scenes behaviours such as buying second-hand clothes or buying misshapen fruit. These behaviours are not as obvious a public projection of environmental values, compared to holding a reusable coffee cup:

It is very hard to say, ‘that’s a lovely top’, but unless you know someone, you wouldn’t know that it is a second-hand top, and that just makes it less visible. And there are no signals out there to go ‘I am reducing my consumption of fast fashion’ or it’s a personal choice buying a wonky banana, no one else is going to see that.

Around half of the focus group participants described enjoying coffee, but not needing to drink it every day. This group attributed the success of using reusable coffee cups to the routine and habit of coffee drinking. One participant explained that millennials enjoy coffee and that if drinking coffee is part of your daily routine, then it is easier to become a habit:

It’s just another thing you have that you carry around with you, you don’t forget to leave your house without your keys, phone or wallet. So, a cup is just an additional thing. And then your bottle of water is just an additional thing. It’s about creating new habits.

The local context of the KeepCup arose during many conversations, and one participant explained that it is a bonus that the KeepCup is a Melbourne invention. The KeepCup was created in 1998 in Collingwood, Melbourne, and comes with the novelty of being able to order your KeepCup online, customise the colours, and then pick it up from the Melbourne warehouse:

I’ve bought one [KeepCup] as a gift, and another reason I got a KeepCup over any of the other reusable cups, is that it’s nice that it’s made in Melbourne. I went and picked them up from the place where they were boxing them and everything. That’s a bonus.

Continued behaviour change of using a reusable coffee cup

What is motivating millennials to continue using reusable coffee cups? One focus group participant felt War on Waste had made the issue of waste more mainstream and that the momentum was continuing. Participants acknowledged that they felt more inspired that change will occur, and one even explained a change in environmental conscientiousness at local music festivals:

I’ve noticed that a lot more festivals are going waste-free that I’ve been to with people my age. I was at Golden Plains Music Festival, and they were offering to wash your plates for you, and I’ve been going to that festival for several years and I feel like it’s only really starting to happen now. I just don’t think it would have been as high profile had it not been for this [War on Waste].

Although it does not seem to be a driving factor for sustained use of reusable coffee cups in the millennial generation, one participant mentioned that some cafés are offering a financial incentive if consumers bring their own coffee cup for takeaway coffee. The participant also mentioned that cafés can print their own logo on reusable coffee cups and then use them as a marketing tool:

There is a coffee shop near my work that was offering a 50% discount if you have a KeepCup, and after they introduced that we did notice a spike in KeepCups in that area, and they provide their own Keep Cups as well, so that helps.

Discussion

This research used War on Waste as a case study to analyse the principles and strategies within Entertainment-Education interventions that can potentially lead to behaviour change. In particular, the research aimed to uncover the reasons why millennial viewers of War on Waste adopted and maintained the use of reusable coffee cups.

Confronting and engaging visuals

Focus group participants liked the surprising visuals in each episode, including the Melbourne tram filled with disposable coffee cups in peak hour – an unexpected and memorable way to demonstrate the 50,000 disposable coffee cups (or tram load) sent to landfill every 30 minutes in Australia. Therefore, Entertainment-Education practitioners should consider using confronting visuals, which are a more engaging way to present data or statistics, instead of the traditional cognitive-oriented strategy by communicating facts and data and expecting people to change (Lubjuhn & Pratt, Citation2009). Powerful and entertaining visuals are a mechanism to prompt empathetic and emotional responses within viewers (Lubjuhn & Pratt, Citation2009) which has been found as a precursor to audience knowledge and willpower (Lichtl, Citation1999).

Relatable host, investigative tone and joint-learning experience

A respected, credible and engaging host can be a powerful tool in Entertainment-Education interventions. For instance, research has found that people considered to be more credible, are more likely to be persuasive in their messaging (Callaghan & Schnell, Citation2009), as has also been found when celebrities are used as messengers (Fu, Ye, & Xiang, Citation2016). In the case of War on Waste, Craig Reucassel played an important role in some participants’ initial interest to watch season one, and then became easy to follow as he learnt, step-by-step, how to tackle Australia’s issue of waste. This joint learning experience is consistent with Klöckner’s (Citation2015, p. 165) perspective that ‘it is not enough to simply tell information, there must be a degree of showing the user how to change at the behavioural level’. War on Waste showed the audience how to tackle the issue of waste, by breaking it down into bite-sized actions.

This joint learning strategy is consistent with the Sabido methodology (Citation2003), which draws upon many sociological theories, including Bandura’s (Citation1986) social learning theory (Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation, Citation1994; Peirce, Citation2011). According to the methodology, an Entertainment-Education intervention should reward transitional characters who make progress towards the desired behaviour change, and negatively reinforce characters who are resistant to change (Bandura, Citation1977; Peirce, Citation2011). In the context of War on Waste, Reucassel acts as the transitional character who is on a journey towards a more environmentally friendly lifestyle. His actions are positively reinforced because he expresses his satisfaction in taking action against Australia’s waste issue.

Creating relatable content

People have a tendency to prefer media from their own culture because it is more relatable to their own life (Straubhaar, Citation1991). The current case study further validated this theory. All focus group participants enjoyed that season one of War on Waste felt ‘close to home’ with everyday artefacts that reminded them of their own culture and everyday life.

Understanding an audiences’ social norms, lifestyles, attitudes and values is a useful starting point for communication campaigns oriented at changing consumer behaviour (OECD, Citation2008; Reisch & Bietz, Citation2011). This is consistent with Hall’s (Citation1973) theory that new information needs to be tied to a person’s existing thought domain to make sense. To map a new piece of information, it can be embedded into an existing set of meanings, which could be in the form of practices, beliefs, knowledge about social structures and norms, and power (Peirce, Citation2011). A common practice for Melbourne millennials is drinking coffee, especially in the city that claims to be the coffee-capital of Australia. This is a possible explanation for why using reusable coffee cups was adopted at a higher rate than other pro-environmental behaviours, because drinking coffee is a part of millennials’ social norms and lifestyle. If a behaviour is repeated enough times (i.e. drinking coffee) and in a consistent context, it is likely to become a habit (Lally, Van Jaarsveld, Potts, & Wardle, Citation2010; Verplanken & Aarts, Citation1999), which may also explain why focus group participants have so-easily adopted using reusable coffee cups.

From Entertainment-Education intervention to behaviour change, to social change

A common problem with behaviour change initiatives is that a person will only change their behaviour if they feel like others are going to change their behaviour too (Staats, Wit, & Midden, Citation1996). This often leads to ‘the tragedy of the commons’, which occurs when individuals act in their own best interest believing that their action will not make a difference, but results in the collective tragedy of the whole group (Hardin, Citation1968). War on Waste potentially provides two important lessons in overcoming the tragedy of the commons. Firstly, Entertainment-Education interventions that promote an individual behaviour, or ‘call to action’, are much more likely to lead to behaviour change, rather than simply telling the audience facts about an issue and expecting them to change (Staats, Wit, & Midden, Citation1996). This is largely because education alone, has been found repeatedly to be insufficient in changing human behaviour (McKenzie-Mohr, Citation2011). The ABC’s War on Waste provided education but amongst a range of other strategies. For instance, it outlined clear, realistic actions that viewers could adopt to tackle the nation’s issue of waste at an individual level. Secondly, focus group participants felt as though season one had created a groundswell for environmental change, which was achieved through targeting various levels of stakeholders. Participants felt re-inspired, or inspired for the first time to take action because Reucassel targeted the everyday consumer, lobbied politicians, and persuaded café owners to provide a discount for people who brought their own coffee cups. All stakeholders felt jointly accountable and responsible, and this ‘groundswell’ would not have occurred had it not been for collaboration and a multi-pronged approach. To create a ‘groundswell’, Entertainment-Education practitioners should promote a realistic ‘call to action’ for the viewer, as well as making sure the intervention targets various levels of stakeholders and holds them accountable for their actions.

Cognitive processing theories

Focus group participants felt as though using a reusable coffee cup was an easier, low-cost behaviour in terms of effort compared to using a compost bin or having a worm farm. This is consistent with research that shows behaviours that have a quick learning curve and require less effort are more likely to be repeated (Ajzen, Citation1991; Diekmann & Preisendörfer, Citation2003; Stern, Citation2000). Participants also explained that recycling soft plastics was perceived to be an easy behaviour, however one was sceptical that soft plastics were not being appropriately recycled (which was shown in War on Waste), and another explained that there is a lot of confusion and variation in between councils in their collection of soft plastics. This level of distrust and confusion led participants to adopt reusable coffee cups more than recycling soft plastics. This was because they felt like they had more control over the outcome of using a reusable coffee cup – known as internal locus of control – compared to not knowing whether their effort in recycling soft plastics was actually making a difference (Fielding & Head, Citation2012; Hines, Hungerford, & Tomera, Citation1987). Compared to recycling soft plastics, using a reusable coffee cup had a quicker learning curve in terms of understanding how to perform the action, rather than learning about their councils’ individual collection methods, making it more likely to be adopted and maintained (Ajzen, Citation1991; Diekmann & Preisendörfer, Citation2003). One participant described adopting the reusable coffee cup as a ‘directly substitutable behaviour’ because it only required a one-step behaviour change, where the disposable coffee cup was substituted by the reusable cup. Participants could not think of an icon equivalent to the reusable coffee cup that would be a direct substitute for organic waste, other than a bin. As such, focus group participants perceived using a reusable coffee cup as being more convenient than using a compost bin or worm farm. Therefore, for these more difficult behaviours, Entertainment-Education practitioners should focus on promoting pro-environmental behaviours that are perceived to be easy and low-cost, which can then double up as good ‘catalyst behaviours’ (Steg & Vlek, Citation2009; Whitmarsh, Lorenzoni, & Neill, Citation2012). Focus group participants also explained that millennials’ living situations, which are typically in share houses and apartment arrangements, may not be suitable for compost bins or worm farms because of a lack of space. Contextual factors, such as structural or lifestyle barriers, mean that individuals may not be able to translate their pro-environmental values to other behaviours, despite wanting to do so (McKenzie-Mohr, Citation2011).

The focus group results also further validate Ajzen’s (Citation1991) theory of planned behaviour: participants had a positive attitude towards using reusable coffee cups, it was perceived to be a very easy behaviour to adopt and was seen to be within social norms. By meeting these elements, it is more likely that millennials will hold strong intentions towards using reusable coffee cups, and are likely to maintain this behaviour (Ajzen, Citation1991). Previous research also suggests that pro-environmental behaviours are more likely to be adopted when social pressure is placed on them, such as when people are scrutinised by others for not putting out their recycling bins (Barr, Citation2003). This can be seen in the situation of the KeepCup because it is a visible behaviour. Whereas participants felt as though composting and buying fruit without packaging, are behind-the-scenes behaviours that perhaps do not have such strong social norms.

The reusable coffee cup as an expression of identity

Focus group results indicated that the reusable coffee cup has become a way an individual can express their identity and environmental values. It was also a way to embrace Melbourne’s coffee culture because participants felt as though using a reusable coffee cup projected their environmental values. This finding aligns with Sartre’s (Citation1956) seminal ontology paper about the self, which states that the objects we choose to buy are in line with who we are. This is extended in consumer behaviour theory where Belk (Citation1978, p. 146) states that ‘people seek, express, confirm, and ascertain a sense of being through what they have’. One possible conclusion is that the reusable coffee cup has become an extension of the self, and those who consider themselves to be ‘environmentally-conscious’ can now hold a product that says the same.

This product-consumer relationship shows us there is potential to embed environmental consumer products into Entertainment-Education interventions that can become visible expressions of environmental values. It is naïve, however, to think that every product will be adopted in the same way as intended; and meaning will be attributed differently to every product depending on the consumer. Despite this, with initial social marketing tests and consumer feedback, there may be potential synergies between Entertainment-Education interventions that promote a simple, cost-effective product that can combat over-consumption.

What does this research mean for practitioners?

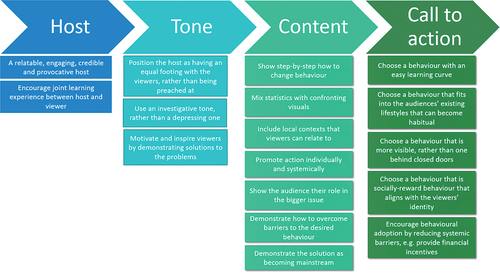

The War on Waste case study has implications for the broader field of communication for social change and shows that Entertainment-Education strategies can be effective in promoting sustainable behaviours. The focus group findings demonstrate consistencies with existing theories about Entertainment-Education interventions and cognitive processing theories. The main findings recommend the need for Entertainment-Education practitioners to understand their target audiences’ cultural backgrounds, attitudes and lifestyles, and potential barriers to change. Gaining an understanding of this will help to narrow down an achievable behaviour that the audience can tackle at an individual level that is perceived to be easy, low-cost (in terms of effort and financially) and within social norms. It is recommended that a respected and credible host or protagonist is used, who can take the audience on a joint-learning experience. Additionally, to aid in behaviour change, it is suggested that the host stumble upon similar barriers that the audience is likely to face, then outline and demonstrate ways to overcome them.

Entertainment-Education in the anthropocene

In the current Anthropocene, the magnitude of global environmental problems requires broad behaviour change not just at the individual level, but also at a systemic level. Whilst the scope of this study involved focusing on one individual waste behaviour, War on Waste has been found to be an ideal case study to also demonstrate the widespread impact Entertainment-Education can achieve at both micro, meso and macro levels. A research study by Downes, Williams, Calder, and Dominish (Citation2019) evaluated the impact of War on Waste after season one and two had aired and found them to trigger both individual level behaviour change as well as systems-wide changes across private, public and community sectors. The evidence suggested that 73% of 452 high impact waste reducing initiatives by 280 different organisations and institutions across Australia were directly influenced by War on Waste. The research alluded to War on Waste generating a ‘new consciousness’ that goes beyond changing individual habits. Behaviours considered to normally be ‘out of sight, out of mind’ were brought to the forefront of viewers via widespread national discussion. This was facilitated by marketing and impact campaigns that utilised ancillary content on radio, television and online platforms. Therefore, it is important to note that whilst the findings and guidance provided from this article focus particularly on understanding how to effectively influence individual behaviour change, this is just one vital component and avenue for Entertainment-Education to generate impact. Generating environmental impact sits within a broader social change landscape, encompassing and requiring both individual and systemic levels of change. The research findings from War on Waste provides a useful Entertainment-Education framework that can be applied to generate impact at scale to address other critical issues in the Anthropocene.

Limitations and future research

In the current study, the sample was limited by its recruitment strategy as participants were recruited through Facebook groups or pages with an environmental focus (i.e. repair cafes, sustainability groups or zero waste groups), as well as easily accessible university circles. Despite attempts to recruit participants more broadly, there was a low success rate, and therefore the sample is possibly biased towards those with higher-education and environmental values. In addition, this sample was heavily skewed towards females, therefore introducing gender bias. While this research uncovers useful findings and is an important line of inquiry, these limitations inhibit the extrapolation and generalisability of these results to the broader population. Future studies with larger and more representative samples, including quotas for diversity in location (i.e. regional versus city), gender and ethnicities, and drawn from various groups (i.e. non-environmental and environmental) would provide greater generalisation of findings for broader application-led Entertainment-Education. Participants may need to be financially incentivised to reach these quotas.

Future research should also investigate further insight from Entertainment-Education practitioners to gain a deeper understanding of the intervention design process. Analysing and providing feedback on this process – including initial development stages, audiences’ perception and changes in audience behaviour – would provide valuable research to help advance the field of Entertainment-Education interventions in Australia, and globally.

Conclusion

This case study demonstrates potential strategies to enhance Entertainment-Education interventions including powerful storytelling, an engaging and relatable host, confrontational and surprising visuals, a local and familiar context, practical solutions, changes in behaviour that are perceived to be ‘easy’ with a gentle learning curve, and a multi-pronged targeted stakeholder approach (i.e. consumer, industry and government). These factors were all instrumental in influencing Melbourne millennials to change their behaviour to adopt reusable coffee cups after viewing War on Waste. This change in behaviour demonstrates a small, but essential step in addressing the critical challenges present in the Anthropocene. Additionally, the framework demonstrated in season one of the War on Waste television series provides practitioners with a useful approach to generate impact at scale more broadly.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr Kim Borg for initial feedback and valuable comments on an early version of the article.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- ABC. (2018a). About the Chaser. Retrieved from https://chaser.com.au/about/

- ABC. (2018b). War on Waste. Retrieved from https://www.abc.net.au/tv/programs/war-on-waste/

- Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 179–211. doi:10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T

- Baker, K., Jah, F., & Connolly, S. (2018). A radio drama for apes? An Entertainment-Education approach to supporting ape conservation through an integrated human behaviour, health, and environment serial drama. Journal of Development Communication, 29(1), 16–24.

- Bandura, A. (1977). Social learning theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

- Bandura, A. (1986). Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

- Barnfield, R., & Marks, A. (2018). War on Waste: The survey - understanding Australia’s waste attitudes and behaviours (Vol. 2018). Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved from http://www.abc.net.au/ourfocus/waronwaste/WarOnWasteTheSurveyUnderstandingAustralia’sWasteAttitudesand%20Behaviours.pdf

- Barr, S. (2003). Strategies for sustainability: Citizens and responsible environmental behaviour. Area, 35(3), 227–240. doi:10.1111/1475-4762.00172

- Belk, R. W. (1978). Assessing the effects of visible consumption on impression formation. Urbana-Champaign: ACR North American Advances.

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. doi:10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Bujold, P., Williamson, K., & Thulin, E. (2020). The Science of Changing Behavior for Environmental Outcomes: A Literature Review. Rare Center for Behavior & the Environment and the Scientific and Technical Advisory Panel to the Global Environment Facility.

- Callaghan, K., & Schnell, F. (2009). Who says what to whom: Why messengers and citizen beliefs matter in social policy framing. The Social Science Journal, 46(1), 12–28. doi:10.1016/j.soscij.2008.12.001

- Chirinos-Espin, C. (2021). Music and Culture in Entertainment-Education. In Entertainment-Education Behind the Scenes (pp. 121–135). Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Cleanaway Waste Management Limited, Alt/Shift., & Empirica Research. (2022). Cleanaway recycling behaviours research 2022. Retrieved from Cleanaway website https://cleanaway2stor.blob.core.windows.net/cleanaway2-blob-container/2022/04/13744-AltShift-Cleanaway-Report-V5-10FEB2022-1.pdf

- Cooper, T. (2016). Longer lasting products: Alternatives to the throwaway society. CRC Press. doi:10.4324/9781315592930

- DESA, U. (2022). The sustainable development goals report 2022. New York, NY: UN DESA. Retrieved from https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/report/2022/

- Diekmann, A., & Preisendörfer, P. (2003). Green and greenback: The behavioral effects of environmental attitudes in low-cost and high-cost situations. Rationality and Society, 15(4), 441–472. doi:10.1177/1043463103154002

- Downes, J., Williams, L., Calder, T., & Dominish, E. (2019). The impact of the ABC’s War on Waste. Prepared with the ABC by the Institute for Sustainable Futures, University of Technology Sydney. Retrieved from https://www.abc.net.au/tv/pdf/WoW%20Impact%20Report%2013June19.pdf

- Ferdous, W., Manalo, A., Siddique, R., Mendis, P., Zhuge, Y., Wong, H. S., & Schubel, P. (2021). Recycling of landfill wastes (tyres, plastics and glass) in construction – A review on global waste generation, performance, application and future opportunities. Resources, Conservation and Recycling, 173, 105745. doi:10.1016/j.resconrec.2021.105745

- Fielding, K. S., & Head, B. W. (2012). Determinants of young Australians’ environmental actions: The role of responsibility attributions, locus of control, knowledge and attitudes. Environmental Education Research, 18(2), 171–186. doi:10.1080/13504622.2011.592936

- Fisher, C., Bashyal, S., & Bachman, B. (2012). Demographic impacts on environmentally friendly purchase behaviors. Journal of Targeting Measurement & Analysis for Marketing, 20(3–4), 172–184. doi:10.1057/jt.2012.13

- Fu, H., Ye, B. H., & Xiang, J. (2016). Reality TV, audience travel intentions, and destination image. Tourism Management, 55, 37–48. doi:10.1016/j.tourman.2016.01.009

- Green, D. P. (2021). In search of Entertainment-Education’s effects on attitudes and behaviors. In Entertainment-Education behind the scenes (pp. 195–210). Cham: Palgrave Macmillan. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-63614-2_12

- Gwozdz, W., Reisch, L. A., & Thøgersen, J. (2020). Behaviour change for sustainable consumption. Journal of Consumer Policy, 43(2), 249–253. doi:10.1007/s10603-020-09455-z

- Hall, S. (1973). Encoding and Decoding in the Television Discourse: Paper for the Council of Europe Colloquy on ‘Training in the Critical Reading of Televisual Language.’ Organized by the Council and the Centre for Mass Communication Research, University of Leicester, September 1973.

- Hardin, G. (1968). Science. The Tragedy of the Commons, 13(162), 1243–1248. doi:10.1126/science.162.3859.1243

- Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation. (1994). The use of mainstream media to encourage social responsibility: The international experience. California, USA: Author.

- Heong, K., Escalada, M., Huan, N., Ba, V. K., Quynh, P., Thiet, L., & Chien, H. V. (2008). Entertainment–Education and rice pest management: A radio soap opera in Vietnam. Crop Protection, 27(10), 1392–1397. doi:10.1016/j.cropro.2008.05.010

- Hines, J. M., Hungerford, H. R., & Tomera, A. N. (1987). Analysis and synthesis of research on responsible environmental behavior: A meta-analysis. The Journal of Environmental Education, 18(2), 1–8. doi:10.1080/00958964.1987.9943482

- Hoornweg, D., Bhada-Tata, P., & Kennedy, C. (2013). Environment: Waste production must peak this century. Nature, 502(7473), 615–617. doi:10.1038/502615a

- Kentera, Y. (2017). Get ready Australia… ABC’s War on Waste starts in May. https://about.abc.net.au/press-releases/get-ready-australia-abcs-war-on-waste-starts-in-may/

- Keys, J. (2021). How Nickelodean Framed Entertainment-Education Messages during the COVID-19 Pandemic. In Communication in the Age of the COVID-19 Pandemic (pp. 63–77). Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield.

- Khalid, M. Z., & Ahmed, A. (2014). Entertainment-Education media strategies for social change: Opportunities and emerging trends. Review of Journalism and Mass Communication, 2(1), 69–89.

- Klöckner, C. A. (2015). The psychology of pro-environmental communication: Beyond standard information strategies. Springer. doi:10.1057/9781137348326

- Lally, P., Van Jaarsveld, C. H., Potts, H. W., & Wardle, J. (2010). How are habits formed: Modelling habit formation in the real world. European Journal of Social Psychology, 40(6), 998–1009. doi:10.1002/ejsp.674

- Lichtl, M. (1999). Ecotainment: der neue Weg im Umweltmarketing; [emotionale Werbebotschaften, sustainabilitiy, cross-marketing]. Wirtschaftsverl. Ueberreuter.

- Lubjuhn, S., & Pratt, N. (2009). Media communication strategies for climate-friendly lifestyles–addressing middle and lower class consumers for social-cultural change via Entertainment-Education. Paper presented at the IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, Aarhus, Denmark.

- McKenzie-Mohr, D. (2011). Fostering sustainable behavior: An introduction to community-based social marketing. Gabriola Island, Canada: New Society Publishers.

- Miles, M. B., & Huberman, A. M. (1994). Qualitative data analysis: An expanded sourcebook. California: Sage.

- Mitchell, R. B. (2012). Technology is not enough: Climate change, population, affluence, and consumption. Journal of Environment & Development, 21(1), 24–27. doi:10.1177/1070496511435670

- OECD. (2008). Promoting Sustainable Consumption: Good Practices in OECD Countries. France: OECD Publications. Retrieved from https://www.oecd.org/greengrowth/40317373.pdf

- Peirce, L. M. (2011). Botswana’s Makgabaneng: An audience reception study of an edutainment drama. Ohio: Ohio University ProQuest Dissertations Publishing.

- Pickin, J., Randell, P., Trinh, J., & Grant, B. (2018). National waste report 2018. Retrieved from https://www.dcceew.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/national-waste-report-2018.pdf

- Powell, D. (2017). KeepCup’s co-founder on the “crazy” 400% increase in sales fuelled by ABC’s “War on Waste” program. Retrieved from https://www.smartcompany.com.au/startupsmart/advice/startupsmart-growth/keepcups-founder-crazy-400-increase-sales-fuelled-abcs-war-waste-program/

- Reinermann, J.-L., & Lubjuhn, S. (2012). “Let me sustain you”: die Entertainment-Education Strategie als Werkzeug der Nachhaltigkeitskommunikation, 43–56.

- Reinermann, J.-L., Lubjuhn, S., Bouman, M., & Singhal, A. (2014). Entertainment-Education: Storytelling for the greater, greener good. International Journal of Sustainable Development, 17(2), 176–191. doi:10.1504/IJSD.2014.061781

- Reisch, L. A., & Bietz, S. (2011). Communicating sustainable consumption. In Sustainability communication (pp. 141–150). Springer Netherlands. doi:10.1007/978-94-007-1697-1_13

- Responsible Cafes. (2018). Responsible Cafes Homepage. Retrieved from https://responsiblecafes.org/

- Sabido, M. (2003). The origins of Entertainment-Education. In Entertainment-Education and social change (pp. 61–74). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Publishers.

- Sartre, J.-P. (1956). Being and nothingness: A phenomenological essay on ontology. 1943. (Hazel E. Barnes, Trans.) New York: Washington Square P.

- Silva, A. L. P., Prata, J. C., Duarte, A. C., Barcelò, D., & Rocha-Santos, T. (2021). An urgent call to think globally and act locally on landfill disposable plastics under and after COVID-19 pandemic: Pollution prevention and technological (Bio) remediation solutions. Chemical Engineering Journal, 426, 131201. doi:10.1016/j.cej.2021.131201

- Singhal, A. (2008). Where social change scholarship and practice went wrong? Might Complexity Science provide a way out of this mess? Communication for Development and Social Change, 2(4), 1–6.

- Singhal, A. C., Michael, J., Rogers, E. M., and Sabido, M. (2003). Entertainment-Education and social change: History, research, and practice. Routledge. doi:10.4324/9781410609595

- Singhal, A., & Rogers, E. (1999). Entertainment-Education: A communication strategy for social change. Marwah, NJ: Laurence Erlbaum Associates.

- Singhal, A., & Rogers, E. M. (2002). A theoretical agenda for Entertainment—Education. Communication Theory, 12(2), 117–135. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2885.2002.tb00262.x

- Singhal, A., Wang, H., & Rogers, E. M. (2013). The rising tide of Entertainment–Education in communication campaigns. Public Communication Campaigns, 4, 321–333.

- Staats, H., Wit, A., & Midden, C. (1996). Communicating the greenhouse effect to the public: Evaluation of a mass media campaign from a social dilemma perspective. Journal of Environmental Management, 46(2), 189–203. doi:10.1006/jema.1996.0015

- Steg, L., & Vlek, C. (2009). Encouraging pro-environmental behaviour: An integrative review and research agenda. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 29(3), 309–317. doi:10.1016/j.jenvp.2008.10.004

- Stern, P. C. (2000). New environmental theories: Toward a coherent theory of environmentally significant behavior. Journal of Social Issues, 56(3), 407–424. doi:10.1111/0022-4537.00175

- Straubhaar, J. D. (1991). Beyond media imperialism: Assymetrical interdependence and cultural proximity. Critical Studies in Mass Communication, 8(1), 39–59. doi:10.1080/15295039109366779

- Sweeney, D. (2009). Show me the change. A review of evaluation methods for residential sustainability behavior change projects. Australia: Swinburne University of Technology.

- UNCSD. (1994). General discussion on progress in the implementation of Agenda 21, focusing on the cross-sectoral components of Agenda 21 and the critical elements of sustainability. Paper presented at the The Symposium on Sustainable Consumption (pp. 19–20). January, Oslo.

- United Nations Environment Programme, U., & International Waste Management Association, I. (2015). Global waste management. Outlook. Retrieved from https://wedocs.unep.org/20.500.11822/9672

- Verplanken, B., & Aarts, H. (1999). Habit, attitude, and planned behaviour: Is habit an empty construct or an interesting case of goal-directed automaticity? European Review of Social Psychology, 10(1), 101–134. doi:10.1080/14792779943000035

- Wang, H., & Singhal, A. (2021). Mind the gap! Confronting the challenges of translational communication research in Entertainment-Education. In Entertainment-Education behind the scenes (pp. 223–242). Cham: Palgrave Macmillan. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-63614-2_14

- Whitmarsh, L., Lorenzoni, I., & Neill, S. (2012). Engaging the public with climate change behaviour change and communication. Hoboken: Taylor and Francis. doi:10.4324/9781849775243

- Yue, Z., Wang, H., & Singhal, A. (2019). Using television drama as Entertainment-Education to tackle domestic violence in China. The Journal of Development Communication, 30(1), 30–44.

- Zhao, Z., Gong, Y., Li, Y., Zhang, L., & Sun, Y. (2021). Gender-related beliefs, norms, and the link with green consumption. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 710239. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2021.710239