ABSTRACT

Leading to Australia’s 2019 Federal election, then-Prime Minister, Scott Morrison, drew attention for posting images of him making family dinners on Facebook. These ‘curry night’ posts became the subject of media banter as he publicly cultivated his ‘daggy-dad’ persona. Assuming this behaviour was strategic, questions arise as to why. This paper considers theories of irrational appeals in political communication to interpret this behaviour. In doing so, it clarifies and operationalises ‘politics of the gut’, a nexus between populist politics and mediated authenticity. This paper tracks authenticity and populist appeals from Australian politicians on Facebook and gauges their efficacy by contrasting randomised and high-engagement samples. Results show these appeals were widespread but differed in configuration between candidates. Furthermore, during the sampled period, authenticity demonstrated increased engagement from users while populist appeals received decreased engagement, offering new perspectives on the efficacy of these communication styles on Facebook.

Introduction

In the lead-up to the 2019 Australian federal election, then Prime Minister, Scott Morrison developed a reputation for posting banal captioned images of himself on Facebook making dinner for his family. These ‘curry night’ posts became the subject of humour and political banter in the Australian media ahead of the impending election. Morrison himself would come to embrace the notoriety, posting photos of his family life on a regular basis with an assumed ‘nod and wink’ to his audience. This isn’t the only time Morrison would embrace being publicly lampooned either. The Liberal party leader also adopted his media nickname of ‘ScoMo’, as he cultivated a ‘daggy-dad’Footnote1persona in the press and online (Delaney, Citation2018; Matthewson, Citation2018). Likewise, Clive Palmer, a competing party leader, was known for posting memes and humorous content – such as splicing the faces of other politicians into movie trailers, or memes referencing nostalgic Australian foodstuffs – a stark contrast to the photo ops and live press conferences typically shared by his peers. If we are to assume this behaviour was deliberate and strategic, the question then arises as to why? Abroad, politicians such as Boris Johnson and Donald Trump also became known for their unrefined communication style or unusual aesthetic choices. This paper examines what, if any, value there is in politicians presenting themselves in a strange and unusual manner; and where such practices fit within our understanding of communicative practice.

We might look to contemporary understandings of rhetorically irrational appeals in politics and social media to identify and interpret this behaviour. In doing so this paper seeks to clarify and operationalise an observed nexus between populist politics and authenticity, something Catherine Fieschi (Citation2019) refers to as ‘politics of the gut’. Fieschi writes, ‘ … there is a key idea at the heart of populism that never quite gets the attention it deserves, and that is the idea of authenticity. Yet, arguably, authenticity might be (the) idea that holds it all together … If democracy promises access and voice, authenticity promises genuine relationships’ (Fieschi, Citation2019, p. 36). This relational politics, as Fieschi suggests, promotes a politics that is motivated by instinct rather than reason, and is part and parcel with contemporary populism. This notion is further affirmed by empirical research of Norwegian voters, suggesting that ‘populist politicians might come across as more “real” and “authentic” than traditional or moderate politicians’ (Enli & Rosenberg, Citation2018, p. 7). More recent studies have also sought to operationalise this intersection, analysing Twitter/X posts from Donald Trump and Boris Johnson (Lacatus & Meibauer, Citation2022) and identifying the prevalence of authenticity appeals. Lacatus and Meibauer also address the conceptual intersection between populism and authenticity, being that of discursive performance. While populism remains a highly contested idea among scholars of politics, recent proponents of the discursive-performative school of populism identify it as something that is ‘communicated and done’ (Kefford, Moffitt, & Werner, Citation2021). In furthering this conceptual nexus, it is worth clarifying that the performance of authenticity and populism are not mutually exclusive. Instead, Fieschi (Citation2019) describes authenticity as a form of ‘social currency’ which is drawn upon by populist actors. It is the position of this paper that within the conceptual sphere of ‘politics of the gut’, authenticity and populism are complementary communicative acts that seek to appeal to voters.

This paper seeks to observe the prevalence of ‘politics of the gut’ in the context of Australian politics on social media to understand how authenticity and populist appeals were used ahead of the 2019 federal election. Indeed, only a few studies have operationalised authenticity in the context of populism and political communication to date (Fuller, Jolly, & Fisher, Citation2018; Lacatus & Meibauer, Citation2022; Luebke, Citation2021). Using quantitative content analysis, I use sampling indicative of both supply-side and demand-side communication to approximate the interest these appeals generate on the Facebook platform. The aim is to demonstrate not only the prevalence of these appeals but also to measure their success online. The results show how frequently authenticity and populist appeals occur, which political actors use them the most, and how the frequency of these appeals varies between supply-side and demand-side sample groups.

Politics of the gut

Populism on social media has been a popular topic for political science and mass communication scholars. Populism’s rise in Western democracies has been attributed in part to the shock voting results of 2016 which were the UK’s Brexit and the US presidential election of Trump (Freeden, Citation2017; Norris & Inglehart, Citation2019). Populism has been observed across conservative and progressive political lines and in various Western democracies like the United Kingdom, United States, Greece, Spain, France, Germany, the Netherlands and Australia (Flew & Iosifidis, Citation2019; Moffitt, Citation2018). The appeal of populism across political lines has led some to label it a ‘thin ideology’ (Mudde & Kaltwasser, Citation2017), while others have questioned whether it is even an ideology at all (Ostiguy & Moffitt, Citation2020). As politicians embrace populist rhetoric, political discourse shifts from key issues to sensationalist notions like ‘the people’ versus ‘elites’ (Bang & Marsh, Citation2018; Liddiard, Citation2019). Problematically it ‘fundamentally rejects the notions of pluralism and, therefore, minority rights as well as the “institutional guarantees” that should protect them’ (Mudde & Kaltwasser, Citation2017).

Recent increases in populist rhetoric across Western democracies have been attributed to insecurities among the populace in response to immigration and globalisation, financial downturns and diminishing trust in democratic institutions. Alongside changing global economic and social conditions, social media has also been noted for its relationship to the shifting political paradigm (Flew & Iosifidis, Citation2019; Gerbaudo, Citation2018). Platforms such as Facebook, Twitter/X and YouTube allow populist actors to side-step traditional media gatekeepers and establish a direct line to their publics. These technologies also afford easier spread of propaganda, disinformation, and fake news. Therein populism’s role in political discourse has evolved due to shifting conditions in Western democracies with its expansion backed by technological advancements that facilitate its spread and weaken institutional resistance.

This article adopts Fieschi’s ‘politics of the gut’ as an umbrella term for these appeals in political communication. We can consider authenticity alongside populism based upon a shared nexus wherein scholars have theorised each as a form of performative and mediated practice observed in political communication. While authenticity appeals generate trust and relatability with audiences, populist rhetoric appeals to insecurity or distrust among voters. What distinguishes authenticity and populism from other irrational appeals is their standardised use in Western politics to distinguish their adopters from mainstream, over-rehearsed or tired politics. Political actors may adopt either as a form of irrational political rhetoric, preferencing impulsivity and emotions over logic and reason. Both are relational and require shared meaning-making between political actors and their audiences. While one can be used independently of the other, Fieschi suggests that contemporary populist actors use authenticity as a form of social currency, whereby one works to strengthen the other (Fieschi, Citation2019). Furthermore, it has been suggested that authenticity may be weaponised against elites, as populist actors may attempt to expose competitors as inauthentic while bolstering their own credibility (Sorensen, Citation2018).

In examining authenticity, two key theorisations are prevalent among current social science literature: Enli’s (Citation2014) framework of ‘mediated authenticity’ and Banet-Weiser’s (Citation2012) brand culture critique of authenticity. Through Enli’s theorisation, authenticity can be understood as a form of shared meaning-making between audiences, and media producers like politicians on social media. Gunn Enli suggests politicians use the performance of authenticity to establish trust between them and voters (Enli, Citation2014). Appeals to ambivalence, confessions, and imperfection constitute this meaning-making, which speaks to broader frameworks of political persuasion and mediatisation. These illusions of authenticity, in Enli’s words, ‘take place in mainstream media through various degrees of scripting of the performances of ordinary people’ and although a mere construction, make claims of ‘legitimacy as a representation of raw and unscripted reality’ (Enli, Citation2015, p. 121). As a communicative practice, authenticity might be understood as something we do, as opposed to something we are. Authenticity is valuable for politicians as it helps to establish trust with voters, but it can also obscure the difference in power relations between elected officials and citizens (Enli, Citation2015, p. 133). In comparison, Banet-Weiser’s definition is less prescriptive and instead emphasises authenticity as a form of symbolic power, focusing on its cultural affect rather than its construction (Banet-Weiser, Citation2012). These definitions don’t appear to be incompatible with each other, but instead emphasise different aspects of authenticity and its meaning making.

Authenticity appeals, like populist ideation, lend themselves to the affordances of digital platforms. In the context of social media and authenticity, Gaden and Dumitrica (Citation2015) argue that ‘politicians adapt to the logic of the dominant medium of communication in order to reach large numbers of voters’. Furthermore, Serazio (Citation2017) argues that ‘the increasing centrality of branding logic, authenticity schemes, and emotional angles within strategic communication is occurring at a time of significant change as new models of networked, digital politics emerge’ and that political consultants ‘maintain a logic or sensibility that emphasizes simplistic differentiation amidst semiotic clutter’ (Serazio, Citation2017, p. 228 & 238). Given the restricted social media attention spans and message limitations, populism and authenticity might gain more traction than other political appeals.

Campaigning online

For politicians and parties, much has changed when it comes to campaigning and communication in the social media era. Key drivers for evolving political communication practice include new media logics (Chadwick, Citation2013; Klinger & Svensson, Citation2015; Van Dijck & Poell, Citation2013), lowered thresholds for political engagement (Highfield, Citation2017), fragmentation and increased access to information (Bright, Citation2018; Engesser, Ernst, Esser, & Büchel, Citation2017; Karlsen, Citation2011; Mancini, Citation2013). According to Johnson and Perlmutter (Citation2011), diminished control over campaign messages has also been a defining feature of the social era for political campaigns. Candidates must now compete with the voices of everyday users who are creating their own content and directly engaging with campaigns in online spaces (Highfield, Citation2013; Johnson & Perlmutter, Citation2011). Social platforms also establish lower barriers for entry into political activity with easier access to information sharing and network capabilities (Gustafsson, Citation2012).

The content of political communication has also undergone a transformation in the era of social media. Scholars have noted shifting dynamics in electoral politics, particularly in countries like the UK, Australia, and the US, which have led to a departure from traditional class-based appeals. Instead, there is a growing reliance on authenticity appeals to connect with a broader spectrum of voters (Manning, Penfold-Mounce, Loader, Vromen, & Xenos, Citation2017). It has also been suggested that political communication on social media is characterised by increased interactivity and conversational elements compared to legacy media (Chen, Citation2013, p. 74). This shift is facilitated, in part, by the affordances of social media for more relational communication such as conveying authenticity (Duncombe, Citation2019; Manning, Penfold-Mounce, Loader, Vromen, & Xenos, Citation2017). There may also be a push and pull relationship to authenticity and social media, with surveys of young voters showing a desire for more authentic and accessible politicians on social media platforms (Manning, Penfold-Mounce, Loader, Vromen, & Xenos, Citation2017). Emotional authenticity has been described as a ‘commodity of power’ on social platforms (Duncombe, Citation2019, p. 420), serving to counterbalance the limitations of rational appeals on the medium. In addition to authenticity appeals, the prevalence of self-informing through social media has made voting populations more susceptible to populist communication strategies (Hendrix, Citation2019). Populist politicians can create a direct line to their publics on social media, allowing them to circumvent scrutiny and mediation from traditional gatekeepers like producers, editors, and journalists (Engesser, Ernst, Esser, & Büchel, Citation2017). A study of European politicians who used Facebook and Twitter/X found that populist rhetoric was present along both sides of the political spectrum and often in a fragmented form (Engesser, Ernst, Esser, & Büchel, Citation2017), with similar results affirmed in an Italian context (Mazzoleni & Bracciale, Citation2018).Thus we can see a shift towards more relational styles of communication from politicians online that is made possible by the affordances of social media platforms.

Methodology

In this study I seek to observe the prevalence of both authenticity and populist appeals on posts from Facebook pages of Australian politicians and gauge their efficacy by contrasting supply-side and demand-side samples. In addressing this question, I use a novel comparative method of content analysis that includes samples indicative of both supply and demand side communication using randomised and high engagement sampling.

Data collection and sampling

Meta’s CrowdTangle platform was used to collect publicly available Facebook page posts from Australian politicians. The posts were gathered from six Australian party leaders during the 2019 federal election, as set out in . Each representative selected came from parties that secured more than 1% of the vote on election day (Muller, Citation2020). These were selected with the intent to use political actors who were not only high profile and well followed, but also likely to embody the ethos of their respective parties.

Table 1. Total posts collected for each party leader from 1 January 2018 until 31 May 2019.

CrowdTangle is an official data resource from Meta which directly interfaces with Facebook’s API; allowing for tracking of pages, groups, and posts. It has been used as a data collection tool for content analysis of European elections (Haßler, Wurst, & Schlosser, Citation2021) and populist rhetoric during the 2020 Italian constitutional referendum (Punziano, Marrazzo, & Acampa, Citation2021). For this study the metadata and content of posts were extracted from CrowdTangle into comma-separated values files. The resulting dataset included post text, account names, Facebook ID numbers, share status, number of page likes at posting, timestamps, URLs for the post, and engagement metrics.

Posts were collected with publication dates from 1 January 2018 until 31 May 2019. While the election was first announced on 10 April 2019 and then held on 18 May 2019, a broader date range was selected based on the notion of the always-on election and to help capture discourse surrounding several high-profile political events from that period. A total of n = 5933 posts were captured from this timeframe.

This study incorporates a comparative sampling method using both normative and purposive samples derived from the original dataset (n = 5933). The normative sample took 100 randomised posts from each leader’s page (n = 600). The posts were randomised in Excel by assigning each a unique number and then selecting the first 100. The randomised sample, amounting to 10.1% of the dataset, functions as a control group to establish the frequency of content categories and a normative baseline by which to compare the top engagement sample. This normative sample is indicative of the supply-side communication from party leaders during the period. The purposive sample consists of the top 100 most engaged with posts from each page (n = 600). Engagement is calculated by combining the total reactions, shares and comments of a post. This group is used to identify which content categories received the most engagement and is indicative of demand side interest. Combined, both samples amounted to 1109 posts with a 14% overlap between sample groups. This was considered acceptable duplication, with no exclusions made to maintain the veracity of each sampling method.

Content analysis

Party leaders’ posts were analysed using quantitative content analysis with predefined content categories. Content analysis is a common method of empirical analysis in the field of political communication having been used for similar studies examining campaign strategies on Facebook (Borah, Citation2016), political memes (Chagas, Freire, Rios, & Magalh, Citation2019), diplomatic efforts on social media (Spry, Citation2018, Citation2019) and political Facebook groups (Woolley, Limperos, & Oliver, Citation2010).

Content analysis may operationalise conceptual and theoretical frameworks as content categories and codes to apply to discrete pieces of media content. This study operationalises frameworks of mediated authenticity (Enli, Citation2014) and populism (Engesser, Ernst, Esser, & Büchel, Citation2017). Combined, these frameworks are used to identify themes and styles present in the Facebook posts of politicians. Enli offers 7 characteristics or markers of authenticity in the media that I use as content categories in this study: predictability, spontaneity, immediacy, confessions, ordinariness, ambivalence, and imperfection (Enli, Citation2014, pp. 136–137). For populism I adopt 5 traits defined by Engesser, Ernst, Esser, and Büchel (Citation2017): emphasising the sovereignty of the people, advocating for the people, attacking the elite, ostracising others, and invoking the heartland. These codes are further described and operationalised in the findings.

Findings

The results of this study indicate that both authenticity and populist appeals were apparent among party leaders, but the distribution of these appeals differed between leader’s pages and between samples. The following sections identify the prevalence of these appeals, including the comparisons of their supply side engagement, and discuss the implications of the results.

Authenticity appeals

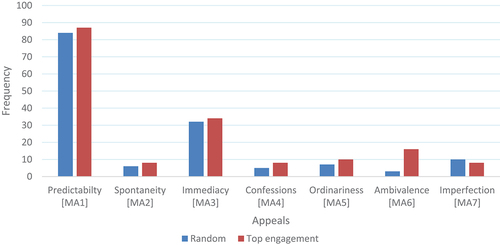

shows the frequency of authenticity appeals between party leaders. This data shows how often particular authenticity appeals were demonstrated by each party leader, across both the randomised and high engagement sample groups as well as their averages. A number of inferences can be drawn from this data including how commonplace certain appeals were, how they varied between candidates and whether those specific appeals were more prevalent among posts that received high engagement.

Table 2. Frequency of authenticity appeals between party leaders (100 randomised and top engagement posts per politician).

Of the seven appeals, predictability was the most commonplace. Predictability is defined by Enli (Citation2014, p. 136) as the ‘consistent use of genre features and conventions for mediated communication’. These broad genre conventions were evident in the posts’ formatting styles and subject matter. Examples include the sharing of press conference footage, live footage of speeches on the floor of Parliament, and selfies and photos with constituents at events. Each politician had their individually predictable formatting trends too. For example, McCormack and Palmer would post media releases on their pages. Morrison would feature high-production interviews with himself and his family discussing aspects of his life at home. For Palmer, predictability was also observed through frequent posting of memes and other web humour. Hanson would frequently post videos from morning shows, featuring her debates with hosts or fellow politicians. Predictability was one of the immediate outliers among both samples. From the randomised sample the results showed that posts made by each politician consistently adhered to genre conventions. Among the high-engagement posts, predictability was notably lower for Morrison (n = 76), Di Natale (n = 90) and McCormack (n = 90) than their randomised posts, but for Shorten (n = 86), Hanson (n = 88) and Palmer (n = 94) predictability was higher. The mean average across randomised pages was 84.3 for predictability while average for the high engagement sample was 87.3. The significantly higher frequency of predictability compared to other appeals also suggests that the leaders have a set of conventions to which they consistently adhere and on average predictability was more likely to be observed in the high engagement posts.

Immediacy was the second most frequently occurring authenticity appeal. Immediacy manifests as posts that are either explicitly or implicitly live (Enli, Citation2014). Facebook facilitates the recording of live video content which is then archived as a post. Liveness was also characterised by posts responding to matters of the day or produced ‘in the now’ such as a status update reacting to television events. It was also common to see the candidates upload videos of themselves speaking on the floor of parliament, at press conferences or as candid moments speaking directly to their audience. An example of the latter can be seen by Morrison making a handheld video on election day and espousing his political philosophy. McCormack and Hanson would also record live videos using standing cameras, often on location at regional centres. Palmer would post videos from his rally speeches or humorous handheld footage from his office. The mean frequency of immediacy appeals across all posts was 31 (see ). This is significantly higher than the average seen for all other appeals except predictability. Of the leaders, Morrison (n = 44) and McCormack (n = 41) had the most immediacy appeals while Palmer had the lowest (n = 14). Like predictability, immediacy was more prevalent on average among the high engagement sample. For Morrison (n = 53), Shorten (n = 40), Hanson (n = 43) and McCormack (n = 43), immediacy was more prevalent among their high engagement posts than from the randomised samples. While for Di Natale (n = 18) and Palmer (n = 8), immediacy was less prevalent among their high engagement posts. These results suggest that approximately one third of the content was being produced live and unedited, or at least appears as such. The higher average among the high engagement sample also suggests that this appeal was effective in so far that it was more common among popular posts.

All but one of the remaining appeals were more prevalent among the high engagement samples. Spontaneity, confession, ordinariness, and ambivalence were more likely to be observed among popular posts. Imperfection was the only appeal to have a lower average frequency from the high engagement sample. Closer inspection of the differences between candidates shows that this inverted trend was skewed by an overrepresentation of appeals from Palmer. For Morrison, McCormack, Shorten and Hanson these appeals were more common among high engagement posts. For Di Natale the frequency of these appeals was the same in both samples. This also demonstrates a trend among posts from Palmer’s authenticity appeals, as often the frequency of his appeals are outliers. This can be seen with his top engagement posts where ambivalence (n = 72) was 56 points higher than the average. His frequency of predictability among the randomised sample was also 18 points below average. Palmer’s brand of authenticity is markedly different from his peers: typically, less predictable but more ambivalent and imperfect.

These results make for interesting comparisons to the results of a prior study of mediated authenticity using Malcolm Turnbull’s Twitter/X posts which found predictability, spontaneity, and immediacy as commonly occurring appeals from the former Prime Minister (Fuller, Jolly, & Fisher, Citation2018). While the results of this paper did not find spontaneity to be much of an outlier, predictability and immediacy were significantly more frequent in their occurrence than other appeals. Since Fuller, Jolly, and Fisher (Citation2018), p. did not publish their tabulation, it is not possible to make complete comparisons, but this does raise questions about emerging platform logics among Australian politicians. Future research might examine whether there are shared affordances between Twitter/X and Facebook that would encourage these specific appeals, or whether they are a reflection of a common communication practice by party leaders.

Populist appeals

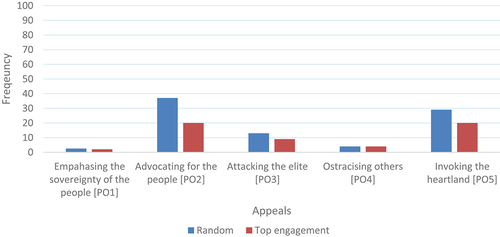

It is evident from this content analysis (see below) that populist appeals were also present in the posts made by party leaders, but the qualities and distribution of those appeals varied from politician to politician. Advocating for the people and invoking the heartland were, on average, the most used appeals in both the randomised and high engagement samples. These were also the only appeals that never featured a zero count between candidates. The least frequently used appeals were emphasising the sovereignty of the people and ostracising others, although there was some variation on the latter with respect to Hanson.

Table 3. Frequency of authenticity and populist appeals between party leaders (100 randomised and top engagement posts per politician).

The fragmented distribution of populist appeals observed by Engesser, Ernst, Esser, and Büchel (Citation2017) in European general elections is observed within this study. Distinctions between the left-leaning and right-leaning parties are evident in the distribution of appeals. For Morrison and McCormack, attacking the elites was absent from their palette of appeals. Likewise, for Shorten and Di Natale, ostracising others was absent. While both types of appeals were generally low among sample groups, this distribution might demarcate a point of difference between political alignments and their populist appeals. These results suggest that populist appeals from party leaders were presented alongside a range of political ideologies and in a fragmented manner ahead of the election.

Advocating for the people was the most common appeal made among the randomised sample. As a representation of the supply-side communication, this could indicate that advocating for the people was an appeal that politicians thought resonated best with users. Prevalence among the randomised sample was consistently higher than that of the top engagement sample, with the exception of posts from McCormack. Unlike ostracising others, advocating for the people might be a less divisive appeal for politicians to make.

Invoking the heartland was another frequent appeal from candidates. Even the least frequent user of this appeal, Di Natale, used it more often than emphasising the sovereignty of the people and ostracising others. Like advocating for the people, its frequency among the randomised sample was consistently higher than that of the top engagement sample, except McCormack. While this appeal was widespread, invoking the heartland was not met with the same interest from users as its supply. Other studies have noted, similar to invoking the heartland, the role of everyday people and ‘townsfolk’ in the construction of Australian political narratives on Facebook (Hendriks, Duus, & Ercan, Citation2016). This reaffirms a supply-side interest in using this approach to political communication in both an Australian context and on Facebook. Whereas the demand-side data suggests this approach is not met with equivalent user interest.

The remaining populist appeals, emphasising the sovereignty of the people, attacking the elites and ostracising others were considerably less present among both sample groups. This reaffirms the fragmentation thesis presented by Engesser, Ernst, Esser, and Büchel (Citation2017), who found that it was rare for politicians to use all populist appeals simultaneously and instead are spread out among posts with occasional groupings of appeals. Possible explanations provided by Engesser (Citation2017, p. 1122) include a need to reduce communication complexity due to platform constraints or attempting to keep the ideology malleable, i.e. ‘flying under the radar’.

The most significant finding of this study is a consistently lower representation of populist appeals among the high engagement sample. Four out of the five appeals were less prevalent on average among the engagement sample. While some scholars have suggested that populism might be facilitated by social media (Hendrix, Citation2019) the result of the analysis offers an additional perspective to this notion. Populist appeals are apparent in posts from Australian politicians, but the lower frequency of appeals among the top engagement sample compared to the random sample suggests that there is a misalignment between the supply of these appeals and user interest. Populist appeals do receive some engagement, so are not repellent, but among the sample of posts with which users were most engaged they had less representation. This suggests that there are issues that users are more interested in than populist appeals.

Comparing appeals

and below compare the mean averages for appeals between the randomised and high engagement samples. These figures demonstrate one of the key findings of this study: higher representation of authenticity appeals in the high engagement sample than the randomised sample. The prevalence of populist appeals showed an inverted pattern, with higher representation among the randomised sample. This shows that authenticity appeals perform better on Facebook. The figures also collectively demonstrate which appeals were the most commonplace during this period. Predictability, immediacy, advocating for the people and invoking the heartland were the common and widespread themes of the appeals during the posting period.

Conclusion

The primary contribution of this study is the operationalisation of authenticity-populism nexus, or ‘politics of the gut’. Comparisons made from this content analysis show the prevalence of this nexus in the 18 months leading up to the 2019 Australian federal election. A number of appeals, specific to the frameworks of authenticity (Enli, Citation2014) and populism (Engesser, Ernst, Esser, & Büchel, Citation2017) were prominent during that time: predictability and immediacy (authenticity); and ‘advocating for the people’ and ‘invoking the heartland’ (populism). Comparisons between supply and demand -side communication suggest these appeals differed substantially in user interest during that period. Demand side engagement for authenticity exceeded supply for the majority of the content categories, while the inverse was true of the more typical populist appeals. These results are noteworthy for a number of reasons. Firstly, this study suggests that research on the ‘thin’ quality of populism, might be expanded to account for the ‘thin-ness’ of authenticity in political communication (Engesser, Ernst, Esser, & Büchel, Citation2017; Mudde & Kaltwasser, Citation2017). Taking a politics of the gut approach (Fieschi, Citation2019) to analysing content from politicians affords the researcher an opportunity to study a broader range of appeals that are deployed by political actors. Second, politics of the gut helps contextualise the daggy-dad persona adopted by Morrison or the outlandish communication practices of Palmer. These performances make actors appear more authentic, and the data in this study supports claims to their efficacy on Facebook.

The secondary contribution of this study is a macro level study of Australia’s political leaders’ prolific use of Facebook during that period. Content produced emphasised live video and handheld footage and for the most part conformed to established genre conventions for social media use. Outliers were present with the prolific use of memes and imperfection by Palmer, but users engaged more with content that demonstrated ambivalence appeals. Appeals associated with populist discourse were present across the board, but anti-elitist elements were not produced by members of the governing party at the time. Instead, advocating for the people and invoking the heartland were the most prevalent populist appeals used by politicians. Future studies could replicate this approach for other elections, either at a state level or across a broader time period to identify whether these patterns are particular to the 2019 Federal election, or broadly typical of the Australian political communication environment.

Populist attitudes have been on the rise abroad (Flew & Iosifidis, Citation2019; Moffitt, Citation2018), but the prevalence of authenticity appeals has previously been unaccounted for. The widespread use of appeals to authenticity may be indicative of politicians adapting to platform logic (Duncombe, Citation2019; Manning, Penfold-Mounce, Loader, Vromen, & Xenos, Citation2017), but the proliferation of celebrity culture and offline social and economic factors could still be at play. We should consider whether these broader dimensions of ‘politics of the gut’ presents the same threat to pluralism that populist rhetoric does (Mudde & Kaltwasser, Citation2017). Populist rhetoric tends to be outward-facing as it invokes the heartland, ostracises others, and attacks elites, whereas the appeals of authenticity are more inward-facing and lack an explicit worldview. Future studies should interrogate these aspects further including their relationships to formats and platforms, and how they might be reflected in voter sentiments. From there we might see whether authenticity appeals are a mask for power relations (Enli, Citation2015), a new face of populism, or perhaps another feature of everyday politics.

Acknowledgments

The data collection and analysis from this article derived from X’s MA dissertation that was prepared under the supervision of Dr Jonathon Hutchinson and Dr Mitchell Hobbs from the University of Sydney, and Dr DS from the University of South Australia.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1. Considered by some to be a media performance, the ‘daggy-dad’ persona embodies an Australian version of the relatable family man often seen in film and television.

References

- Banet-Weiser, S. (2012). Authentic™ : The politics of ambivalence in a brand culture/sarah banet-weiser. New York, NY: New York University Press.

- Bang, H., & Marsh, D. (2018). Populism: A major threat to democracy? Policy Studies, 39(3), 352–363. doi:10.1080/01442872.2018.1475640

- Borah, P. (2016). Political facebook use: Campaign strategies used in 2008 and 2012 presidential elections. Journal of Information Technology & Politics, 13(4), 326–338. doi:10.1080/19331681.2016.1163519

- Bright, J. (2018). Explaining the emergence of political fragmentation on social media: The role of ideology and extremism. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 23(1), 17–33. doi:10.1093/jcmc/zmx002

- Chadwick, A. (2013). The hybrid media system: Politics and power. Cary: Oxford University Press USA - OSO.

- Chagas, V., Freire, F., Rios, D., & Magalh, D. (2019). Political memes and the politics of memes: A methodological proposal for content analysis of online political memes. First Monday. doi:10.5210/fm.v24i2.7264

- Chen, P. (2013). Australian Politics in a digital age. Canberra: Canberra: ANU Press.

- Delaney, B. (2018). Scott Morrison’s daggy dad act is a sign of our times. AU politics. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2018/sep/28/scott-morrisons-daggy-dad-act-is-a-sign-of-our-times

- Duncombe, C. (2019). The politics of twitter: Emotions and the power of social media. International Political Sociology, 13(4), 409–429. doi:10.1093/ips/olz013

- Engesser, S., Ernst, N., Esser, F., & Büchel, F. (2017). Populism and social media: How politicians spread a fragmented ideology. Information, Communication & Society, 20(8), 1109–1126. doi:10.1080/1369118X.2016.1207697

- Enli, G. (2014). Mediated authenticity. New York: Peter Lang Incorporated.

- Enli, G. (2015). “Trust me, I Amauthentic!”Authenticity illusions in social media politics. In The Routledge companion to social media and politics. New York: Routledge.

- Enli, G., & Rosenberg, L. T. (2018). Trust in the age of social media: Populist politicians seem more authentic. Social Media + Society, 4(1), 2056305118764430. doi:10.1177/2056305118764430

- Fieschi, C. (2019). Populocracy: The tyranny of authenticity and the rise of populism. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Flew, T., & Iosifidis, P. (2019). Populism, globalisation and social media. The International Communication Gazette, 82(1), 7–25. doi:10.1177/1748048519880721

- Freeden M. (2017). After the Brexit referendum: revisiting populism as an ideology. Journal of Political Ideologies, 22(1), 1–11. doi:10.1080/13569317.2016.1260813

- Fuller, G., Jolly, A., & Fisher, C. (2018). Malcolmturnbull’s conversational career on twitter: The case of the Australian prime minister and the NBN. Media International Australia, 167(1), 88–104. doi:10.1177/1329878x18766081

- Gaden, G., & Dumitrica, D. (2015). The ‘real deal’: Strategic authenticity, politics and social media. First Monday. doi:10.5210/fm.v20i1.4985

- Gerbaudo, P. (2018). Social media and populism: An elective affinity? Media, Culture & Society, 40(5), 745–753. doi:10.1177/0163443718772192

- Gustafsson, N. (2012). The subtle nature of Facebook politics: Swedish social network site users and political participation. New Media & Society, 14(7), 1111–1127. doi:10.1177/1461444812439551

- Haßler, J., Wurst, A.-K., & Schlosser, K. (2021). Analysing European parliament election campaigns across 12 countries: A computer-enhanced content analysis approach. In Campaigning on Facebook in the 2019 European parliament election (pp. 41–52). New York: Springer.

- Hendriks, C. M., Duus, S., & Ercan, S. A. (2016). Performing politics on social media: The dramaturgy of an environmental controversy on Facebook. Environmental Politics, 25(6), 1102–1125. doi:10.1080/09644016.2016.1196967

- Hendrix, G. J. (2019). The roles of social media in 21st century populisms: US presidential campaigns. Revista Teknokultura, 16(1), 1–10. doi:10.5209/TEKN.63098

- Highfield, T. (2013). National and state–level politics on social media: Twitter, Australian political discussions, and the online commentariat. International Journal of Electronic Governance, 6(4), 342–360. doi:10.1504/IJEG.2013.060648

- Highfield, T. (2017). Social media and everyday politics. New York: John Wiley & Sons.

- Johnson, T., & Perlmutter, D. (2011). New media, campaigning and the 2008 Facebook election. London: Routledge.

- Karlsen, R. (2011). Still broadcasting the campaign: On the internet and the fragmentation of political communication with evidence from Norwegian electoral politics. Journal of Information Technology & Politics, 8(2), 146–162. doi:10.1080/19331681.2011.536419

- Kefford, G., Moffitt, B., & Werner, A. (2021). Populist attitudes: Bringing together ideational and communicative approaches. Political Studies, 70(4), 1006–1027. doi:10.1177/0032321721997741

- Klinger, U., & Svensson, J. (2015). The emergence of network media logic in political communication: A theoretical approach. New Media & Society, 17(8), 1241–1257. doi:10.1177/1461444814522952

- Lacatus, C., & Meibauer, G. (2022). ‘Saying it like it is’: Right-wing populism, international politics, and the performance of authenticity. The British Journal of Politics and International Relations, 24(3), 437–457. doi:10.1177/13691481221089137

- Liddiard, P. (2019). Is populism really a problem for democracy. Washington: Wilson Center.

- Luebke, S. M. (2021). Political authenticity: Conceptualization of a popular term. The International Journal of Press/politics, 26(3), 1940161220948013.

- Mancini, P. (2013). Media fragmentation, party system, and democracy. The International Journal of Press/politics, 18(1), 43–60. doi:10.1177/1940161212458200

- Manning, N., Penfold-Mounce, R., Loader, B. D., Vromen, A., & Xenos, M. (2017). Politicians, celebrities and social media: A case of informalisation? Journal of Youth Studies, 20(2), 127–144. doi:10.1080/13676261.2016.1206867

- Matthewson, P. (2018). Defending the ‘daggy dad’: Why doubting Scott Morrison’s strategy is a mistake. Retrieved from thenewdaily.com.au/news/national/2018/11/09/scott-morrison-daggy-dad/

- Mazzoleni, G., & Bracciale, R. (2018). Socially mediated populism: The communicative strategies of political leaders on Facebook. Palgrave Communications, 4(1), 1–10. doi:10.1057/s41599-018-0104-x

- Moffitt, B. (2018). The populism/anti-populism divide in Western Europe. Democratic Theory, 5(2), 1–16. doi:10.3167/dt.2018.050202

- Mudde, C., & Kaltwasser, C. R. (2017). Populism: A very short introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Muller, D. (2020). The 2019 federal election. Retrieved from Parliamentary Library: https://www.aph.gov.au/About_Parliament/Parliamentary_Departments/Parliamentary_Library/pubs/rp/rp1920/2019FederalElection

- Norris, P., & Inglehart, R. (2019). Cultural backlash: Trump, Brexit, and authoritarian populism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Ostiguy, P., & Moffitt, B. (2020). Who would identify with an “empty signifier”?: The relational, performative approach to populism. In Populism in global perspective (pp. 47–72). Milton Park: Routledge.

- Punziano, G., Marrazzo, F., & Acampa, S. (2021). An application of content analysis to crowdtangle data: The 2020 constitutional referendum campaign on Facebook. Current Politics and Economics of Europe, 32(4), 371–397.

- Serazio, M. (2017). Branding politics: Emotion, authenticity, and the marketing culture of American political communication. Journal of Consumer Culture, 17(2), 225–241. doi:10.1177/1469540515586868

- Sorensen, L. (2018). Populist communication in the new media environment: A cross-regional comparative perspective. Palgrave Communications, 4(1), 1–12. doi:10.1057/s41599-018-0101-0

- Spry, D. (2018). Facebook diplomacy: A data-driven, user-focused approach to Facebook use by diplomatic missions. Media International Australia, 168(1), 62–80. doi:10.1177/1329878x18783029

- Spry, D. (2019). From Delhi to Dili: Facebook diplomacy by ministries of foreign affairs in the Asia-Pacific. The Hague Journal of Diplomacy, 1(aop), 1–33. doi:10.1163/1871191X-15101067

- Van Dijck, J., & Poell, T. (2013). Understanding social media logic. Media and Communication, 1(1), 2–14. doi:10.17645/mac.v1i1.70

- Woolley, J. K., Limperos, A. M., & Oliver, M. B. (2010). The 2008 presidential election, 2.0: A content analysis of user-generated political facebook groups. Mass Communication and Society, 13(5), 631–652. doi:10.1080/15205436.2010.516864