ABSTRACT

This paper proposes a model for an ethical ‘death knock’, the practice by which a journalist approaches a bereaved family to write a story following a newsworthy death. The practice can cause journalists harm, sometimes as moral injury, which results from an ethical breach. Through a literature review and study of Australian journalists, a model of an ethical death knock has emerged that may mitigate moral injury. Elements were developed through analysis of journalists’ expression of how they could be better prepared (training, knowledge, advice, support), and what they perceived as the necessary precursors (conditions) for an ethical death knock (the capacity to act honestly, with respect and empathy, and make a personal approach in circumstances that are justified). The model creates conditions for an ethical death knock through alignment with, and valorisation of, the journalist’s sense of professional identity, which bolsters their resilience to moral injury. The model is underpinned by Bourdieusian field theory.

Introduction

This paper proposes a model for an ethical ‘death knock’, the newsroom term for the practice by which a journalist approaches a bereaved family to write a story following a newsworthy death (Harcup, Citation2014). Paradoxically, the death knock is as routine as it is controversial and has been show to harm bereaved people and the journalists who interview them. At least some of the harm to journalists can be conceptualised as moral injury, which results when journalists believe they may have breached their ethical standards (Watson, Citation2024). Therefore, an ethical death knock model must be premised on understanding why journalists feel moral injury and how it can be mitigated. Through a review of international research and the author’s 2021–22 study of Australian print and digital journalists, comprised of a survey and interviews (see Watson, Citation2022 for further detail of study methods), a model of an ethical death knock informed by elements of Bourdieu’s field theory has emerged that can be used to minimise moral injury to journalists.

Bourdieu’s theoretical toolkit has been widely used to understand the logics of journalism and newsrooms. Here, it helps to account for the way a journalist’s professional standing and experience shapes their behaviour, and further, how the habitus of the journalist (their ‘feel for the game’) is both an outcome of the structure (newsroom) and a contributor to it (Wacquant, Citation1993). As a journalist accumulates capital and increases their agency, they can change their own death knock practice and influence the death knock practice of the newsroom. It is important to note that, in this way, the model can boost the professionalism of the journalistic field, leading to better outcomes for practitioners and interviewees, and a better perception of the field and its practices more broadly.

Although the development of a model for an ethical death knock may have impacts outside the field, the researcher’s interest in developing a model is primarily to support practitioners inside the field. An understanding of what is meant by an ethical death knock can have two interpretations. The first it that it is an ethical practice in and of itself and perceived to be so by those inside and outside the field. However, the author’s interpretation is the alternative: the death knock is not an ethical practice per se, but that it can be an ethical practice within particular contexts and with particular conditions. The model defines those contexts and conditions.

Development of the model is timely, as there has been a dramatic shift in death knock practice towards journalists using social media instead of, or in addition to, personal approaches to families, even when they may not want to (Watson, Citation2022). The ‘digital death knock’ raises new ethical issues for journalists who scrape social media accounts of deceased people and their family for photographs and ‘tributes’, which may occur without the family’s consent or knowledge, or even against their express wishes.

The paper first justifies the need for an ethical death knock model, then offers a working through of its three dimensions – Preparations, Precursors, and Professional Identity. For each dimension and its elements, evidence from the literature and the Australian study and a Bourdieusian analysis is provided. Key themes revealed are the challenge of the death knock, the harms journalists experience, their lack of preparedness, their coping strategies, and the ethical standards they try, and sometimes fail, to follow. The paper will then show how the model can mitigate moral injury, and how field theory informs this knowledge, with reference to key concepts of habitus, nomos, doxa, agency and capital. Finally, the model’s limitations and further research opportunities will be noted. A crucial consideration here is whether the model alone can be successful, or whether other actions are needed.

Why is an ethical death knock model needed?

Australian and international literature provides evidence-based insights that highlight the need for an ethical model for what is a common yet controversial practice that can affect journalists and bereaved interviewees (Duncan, Citation2012; Duncan & Newton, Citation2010; McMahon, Citation2016; Simpson & Cote, Citation2006). Death knocks are routine work for reporters, who are generally young and inexperienced when they first perform them, with little or no training, guidance, or support. Journalists are at risk of physical, emotional, and psychological injury from death knock practice (Barnes, Citation2016; Keats, Citation2012; Keats & Buchanan, Citation2009; McMahon, Citation2016; Rees, Citation2007) as they feel they must remain stoic (Belch, Citation2015) without showing feelings of trauma, which they see as weakness (Novak & Davidson, Citation2013). Awareness of emotional trauma is growing within newsrooms (Osmann, Dvorkin, Inbar, Page-Gould, & Feinstein, Citation2021), but moral injury is overlooked and poorly understood (Smith, Wake, & Ricketson, Citation2023). Importantly, journalists risk moral injury if they feel they have breached their own ethical standards, including through newsroom directives. While it must be noted that positive and negative experiences are reported by journalists and interviewees (Duncan & Newton, Citation2010; McMahon, Citation2016), and some journalists describe post-traumatic growth (McMahon, Citation2016), most think of the death knock negatively, feel stressed, and worry about intruding on privacy and retraumatising people.

The risk of harm to journalists

Death knocks can be personally challenging (Duncan, Citation2012; Simpson & Cote, Citation2006) and potentially harmful (Duncan & Newton, Citation2010; McMahon, Citation2016) to journalists and the bereaved, and the Australian study presented here confirms that reporters are worried about, and impacted by, doing death knocks. For example, while survey participants reported the bereaved are willing to talk to them, and two-thirds can justify the death knock if it is done ethically, most journalists still think of it negatively, find it stressful, feel guilty, and worry about being insensitive, retraumatising people and invading privacy. Four in five survey respondents say they have, at least possibly, been impacted psychologically by doing death knocks, with one in 10 reporting a health condition they believe is related, such as anxiety, vicarious trauma, PTSD, complex PTSD, nervous breakdown, and depression. Nearly nine in 10 journalists say some death knocks affect them more than others, and three-quarters have one that has stayed with them. Journalists recount threats of violence and actual violence. In addition to harm to themselves, journalists worry about causing harm to the bereaved, saying they feel intrusive, abusive, exploitative, and voyeuristic. These feelings suggest moral injury, which underscores that an ethical death knock model must minimise moral injury by minimising ethical breaches.

The risk of moral injury to journalists

Analysis of the literature and the Australian study reveals that journalists hint at moral injury in their framing of the death knock. In the literature, the practice is characterised as a rite of passage (Duncan & Newton, Citation2012; Johnson, Citation1999) and a ‘blooding’ process (Castle, Citation2002, p. 47). The Australian study confirms it is a part of the job ‘you just have to grin and bear’, an initiation that is dreaded, difficult but endured, necessary and transformative. The literature identifies a paradox in that the death knock is seen as both intrusion on grief and privacy, and inclusion of families in stories that may be written even without their participation or permission. Journalists in the Australian study recognise this paradox, and, despite their best intentions, the theme of ‘feeling wrong’ (intrusion) is pervasive. Two-thirds say they must persuade interviewees, at least some of the time, with lines such as ‘it will pay tribute’, ‘it will prevent tragedy’, and ‘it will speak for your loved one’. Many are worried about retraumatising families, and several seek to remind critics ‘we are human’.

Directives from superiors can lead to moral injury

Directives from superiors can set journalists up for moral injury. In the literature, moral injury caused by the directives of superiors is said to disrupt individuals’ confidence in, and expectations about, their own and others’ motivations and their capacity to behave in a just and ethical manner (Drescher et al., Citation2011). Feelings of guilt and shame, but predominantly anger linked to betrayal, are associated with moral injury in journalists (Osmann et al., Citation2021; Yates, Citation2023). Surveyed journalists relate the ‘enormous pressure’ they feel from superiors to get the story. They have little agency in deciding whether to do a death knock (refusal would be ‘career-damaging’) and feel pressure from competitors as well as editors. Some study participants said they had ‘pushed back’ against editors’ unreasonable demands but most felt there was no capacity to refuse outright, admitting to ‘knocking on the grass’ (pretending to knock on a door) instead. However, it must be said that three in five journalists said their death knock experience had been professionally positive, two in five said it had been personally positive, and two in three said it had, at least possibly, advanced their career. A vast majority believe, on balance, that their stories have been more positive than negative, and most believe their stories have helped the bereaved and their communities at least some of the time.

Developing the model

The approach to developing the model combines the literature, Australian study participants’ reflections, and elements of Bourdieu’s field theory used to generate insights into those reflections. Crucial to developing a model that can mitigate moral injury is understanding how, why, and when journalists might experience moral injury. Further, understanding how they are prepared for death knocks, how they could be better prepared, what they find challenging and how they cope are all important factors. Finally, their views about why they do death knocks (motivations) and how they define an ethical death knock reveal key considerations that are relevant in designing an ethical death knock model.

Establishing the conceptual framework

Bourdieu’s field theory provides the conceptual tools used to construct the ethical death knock model. These concepts have been used widely in Journalism Studies to understand the logics of journalism and of newsrooms, and how change can come about (Benson & Neveu, Citation2005; Ryfe, Citation2018; Vos, Citation2019). Field theory allows journalists’ patterns of behaviour to be examined considering their natural dispositions in their field, the kinds of capital they seek to acquire and valorise, and the way they reflect on their practice. Bourdieu holds that a field (the journalistic field) is a ‘microcosm, which has its own rules [and] which is constituted autonomously’ (Citation1998, p. 44). Fields allow the mapping of actors’ (journalists’) social positions and the relative power dynamics between them according to possession of forms of capital, including economic, cultural, social, and symbolic (Bourdieu, Citation1983, Citation1986). The most powerful actors (journalists) have more capital (standing) and define the nomos (culture), which distinguishes and legitimises a field (journalism). Actors (journalists) unquestioningly inherit, at least initially, the rules (doxa) that organise the field, but they compete within the field to influence those rules (Bourdieu, Citation1990). The interaction between individual level (agency of the journalist) and the societal level (newsroom and wider society) occurs through habitus or having a ‘feel for the game’ (Bourdieu & Wacquant, Citation1992). Habitus functions like instinct, allowing action before and beyond conscious deliberation (Bourdieu, Citation1994).

Habitus as a key concept

Importantly, habitus is both an outcome of the structure and a contributor to it (Wacquant, Citation1993). Just as habitus structures and is structured by an individual’s dispositions, by their behaviour and by their position in the social structure, the social structure itself is maintained and changed by the habitus of individuals. Journalists engaging in reflective practice and using their reflection to inform their practice (Schon, Citation1983, Citation1986) are acting on, and modifying, their habitus. Initially shaped by the newsroom doxa, their death knock practice is, over time, increasingly shaped by their own experience. Depending on the degree of capital they have acquired, they may be able to push back against editors’ demands and even influence the way death knocks are done (doxa).

An ethical death knock model: three dimensions

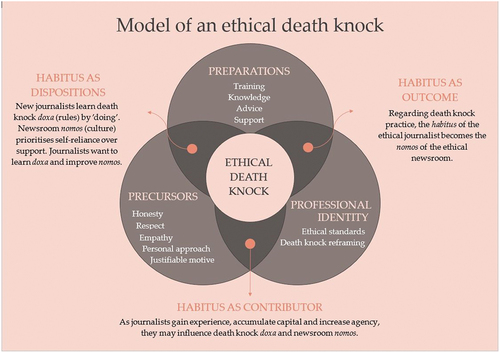

The ethical death knock model is constructed with three dimensions: Preparations, Precursors, and Professional Identity (see ). These dimensions and their components have been developed through a Bourdieusian analysis of the Australian study and the literature discussed earlier to account for how a journalist’s professional standing and experience shapes their behaviour and, ultimately, influences their newsroom, through acquired capital and increased agency.

The first dimension, Preparations, includes four elements that journalists identify can better prepare them for the death knock: training in interviewing bereaved people, knowledge of the grieving process, advice from colleagues and supervisors on death knock practice, and support from colleagues and supervisors before and after death knocks.

The second dimension, Precursors, includes five elements that journalists consider are necessary for an ethical death knock: the capacity to act with honesty, respect, and empathy; to make a personal approach to the bereaved; and to have a good reason (justifiable motive) for doing so, such as strong news value or public interest.

The third dimension, Professional Identity, recognises the connection between how journalists think of themselves and how they behave: their professional identity is enmeshed with ethical standards. Valorisation of their professional identity (ethical standards) and a positive reframing of the death knock as a valid journalistic practice are key elements of the final dimension. Taken together, the three dimensions converge in an ethical death knock that can bolster journalists’ resilience to harm from moral injury.

This section works through the model’s dimensions, highlighting literature, study findings, and aspects of Bourdieu’s field theory that are relevant.

Preparations

Preparations is the first dimension in the model, as the literature and Australian study show that journalists are ill-prepared for doing death knocks. Preparations has the key components of Training, Knowledge, Advice, and Support.

Journalists are not prepared for the death knock

Journalists are generally young and inexperienced when they do their first death knock (Duncan & Newton, Citation2012). They learn by ‘doing’ (Duncan & Newton, Citation2010), with little or no training (Castle, Citation1999) guidance (Barnes, Tupou, & Harrison, Citation2019), or support (Novak & Davidson, Citation2013), and feel the need to remain stoic (Belch, Citation2015) and not show weakness (Novak & Davidson, Citation2013). The Australian study confirms journalists’ lack of preparedness for death knocks. Most survey respondents (70%) said they ‘just did it’. Some relied on advice from supervisors or colleagues or observing newsroom practice, but few had any training. Some demonstrated self-reliance, citing life experience, empathy, family history of mental illness, and local knowledge as helpful. Several said, ‘nothing prepared me’.

Early career journalists are going into an unfamiliar, difficult, and emotionally charged experience without preparations. In Bourdieusian terms, they have not attained the necessary habitus. The newsroom culture (nomos) they experience is one of self-reliance, yet they are without the knowledge, skills, or resilience for the task. They nevertheless do the death knock and change their habitus because of their experience, in time building knowledge, skills and resilience. A more professional and safer approach would be to adequately prepare journalists beforehand and support them afterwards.

Journalists want training, knowledge, and advice

Journalists in the Australian study were asked what would have better prepared them for their first death knock and they highlighted three factors: workplace training, knowledge of the grieving process, and supervisor’s or colleague’s advice. Some also noted that ‘emotional support’ from their managers would have helped, while others said, ‘only doing them can enable you to understand’, and ‘nothing prepares you’. The prioritising of workplace training, knowledge about grieving, and advice from colleagues and supervisors, leads to the inclusion of these elements in the Preparations dimension. In asking for these elements, journalists recognise, in Bourdieusian terms, that they have not attained the necessary habitus. They are seeking clearer rules (doxa) and a more supportive culture (nomos).

Journalists need support

Getting support is identified in the literature and the study as a coping strategy for people experiencing trauma. In the literature, ‘peer support’ is highlighted as a crucial ‘adaptive’ or constructive behaviour, alongside sleep, diet, exercise, relaxation, and socialising (Lee, Ha, & Pae, Citation2018). Study participants confirm they use these coping strategies, alongside ‘maladaptive’ or destructive behaviour, such as alcohol and drug use, self-criticism, and self-blame (Lee, Ha, & Pae, Citation2018). Three quarters of surveyed journalists say they cope with death knocks by talking about their experiences. Most talk to supervisors and colleagues, or family and friends. A small number seek counselling. ‘Buddying up’ with experienced police reporters and photographers is the main advice they give to new colleagues. These findings justify the inclusion of ‘support’ in the Preparations dimension.

Journalists’ experience of nomos and doxa

Journalists’ unpreparedness for death knocks is understood here through Bourdieu’s concepts of nomos (culture) and doxa (rules). New actors (journalists) enter the field and most learn the death knock by ‘doing’ it. Some get advice from supervisors and colleagues and observe newsroom practice, but essentially journalists are socialised into a culture (nomos) that prioritises self-reliance over support from others. Self-reliance becomes inculcated in the journalists’ habitus (Bourdieu & Wacquant, Citation1992). There are rules (doxa) around the death knock, but the individual journalist learns those rules mostly by doing and observing. When surveyed journalists identify workplace training, knowledge of grieving, and advice from supervisors and colleagues as what they needed to prepare for the death knock, they are highlighting failures in nomos (culture) and doxa (rules). They recognise the culture of self-reliance is inadequate to prepare them for the death knock and want better support and help to learn death knock doxa (rules).

Journalists’ framing of the death knock

The death knock is framed by beginning and experienced journalists as an initiation into the journalistic field (Castle, Citation2002; Duncan & Newton, Citation2012; Johnson, Citation1999). Initiation is perpetuated through hierarchy, which Bourdieu explains through the acquisition of capital, as actors (journalists) who have acquired capital set the doxa. Another frame, ‘death knock as commercial imperative’, which journalists highlight through their recognition that death ‘stories sell and attract readers’, can set journalists up for moral injury. The death knock must be reframed as legitimate journalistic practice within an ethical framework, as will be explained in relation to the third dimension, Professional Identity.

Precursors

The second dimension, Precursors, lays out the conditions necessary for journalists to feel they are doing an ethical death knock. Conditions arise from intrinsic motivation (journalists’ behaviour and preferred death knock methodology) and extrinsic motivation (newsroom justifications for the death knock and imposed death knock methodology).

The challenge of approaching the bereaved

The literature reveals that one of the most challenging aspects of the journalist’s work in reporting trauma is approaching survivors, victims and the bereaved (Duncan & Newton, Citation2014; Dworznik-Hoak, Citation2020; Moreham & Tinsley, Citation2019; Muller, Citation2010) and what differentiates the death knock from other interviews is its ‘intense atmosphere’ (Duncan & Newton, Citation2010, p. 448). The Australian study findings support this observation, therefore, in outlining precursors for an ethical death knock, attention must focus on the journalist’s approach to the bereaved, and this is relevant to intrinsic and extrinsic motivations.

Australian study participants identified ‘making initial contact with interviewees’ and ‘justifying the request for interview’ as far more challenging than the interview itself and writing the story, including what material to include and exclude. In defining an ethical death knock, many drew attention to the approach to the bereaved, highlighting the need for honesty (also openness, transparency, and integrity) with comments such as ‘be clear about your intentions’ and ‘the idea is that when they open the paper there are no surprises’. Honesty, therefore, forms an important first element of the Precursors dimension.

Honesty, respect, and empathy

Surveyed journalists also identify ‘respect’ and ‘empathy’ as crucial to ethical approaches to the bereaved. Respect is linked to notions of seeking permission, allowing time for grieving, and giving the family ‘some control’, with comments such as ‘no means no’ and ‘don’t badger them’. However, there is recognition that ‘you might need to explain the benefits’ or ‘it can be good to use an intermediary’, such as ‘police or funeral director or family friend’. Empathy for the bereaved is described as recognising their situation, often shock, loss and mourning, with comments such as ‘put yourself in their shoes’ and ‘give them time to think’. Journalists describe empathy as compassion, care, sensitivity, understanding, patience, ‘go softly’ and ‘go slowly’, ‘be gentle’ and ‘be guided by them’. Therefore, respect and empathy are also key elements of the Precursors dimension.

A personal approach

In defining the circumstances of an ethical death knock, half of survey respondents drew attention to decision-making and behaviour, and two-thirds referred to a specific method of making contact, and some did both. In discussing their methods, some highlight affordances they believe are necessary for an ethical death knock, such as bending usually inflexible work practices to allow families to read stories before publication or ‘email quotes, rather than give a full-on interview’. Responses that focus on methodology are imbued with the theme of ‘personal contact’, and this becomes a key element to the Precursors dimension.

Almost a third mentioned face-to-face interviewing as ethical best practice, followed by involvement of an intermediary such as police or extended family, and using the telephone. Fewer than one in five thought use of social media was best practice. These results can be contextualised with other findings that show while nine in 10 journalists use social media in their death knocks, their preference is to use it to locate and contact interviewees, and, once contact is made, a vast majority then prefer to interview face to face or over the phone. Most journalists in the study also say they would prefer families to provide them with photos directly, but two-thirds will download them from social media with permission, one in five will do it without permission, and one in four will do it if permission has not been explicitly given (request not answered). Only a few journalists said they would use photos if permission was denied. These findings highlight a tension between what journalists say they want to do and what they feel compelled to do because of the immediacy of access of social media.

A justifiable motive

Some surveyed journalists say that for a death knock to be ‘ethical’, there must be a good reason (justifiable motive) to do it, such as ‘strong news value’ or ‘legitimate public benefit’. Some say an event’s ‘scale’ and ‘importance’ should factor more prominently in decision-making, with comments such as ‘don’t do them unless absolutely necessary’ and ‘grieving families should not be bothered at such a time’. The need to ‘moderate the pack’ was highlighted by several, particularly in high-profile and high news value cases where ‘harassing and hounding’ people could occur. Several respondents urge journalists to ‘apply the [MEAA] Code of Ethics’, which states that reporters have a right not to intrude. However, as noted, most journalists feel they have little agency to refuse the task. Therefore, ‘a justifiable motive’ becomes a key element of the Precursors dimension.

The commercial imperative

The idea that a justifiable motive is a key component of an ethical death knock must be contextualised with another survey finding in which journalists highlight the death knock’s ‘commercial imperative’, further exposing a tension between what journalists say they want to do and what they feel compelled to do, or perhaps highlighting how journalists can hold, at once, seemingly competing frames for the death knock as ‘commercial imperative’ and ‘public interest journalism’. When asked why journalists do death knocks, survey respondents ranked ‘stories sell and attract readers’ well ahead of benefits to communities, bereaved people, or themselves. This finding is important in the model as it directly relates to the journalist’s agency.

The journalist’s agency

Agency is a key part of field theory, and Bourdieu highlights how habitus provides the link between individual level (journalist) and societal level (newsroom, journalism, and wider society) (Bourdieu & Wacquant, Citation1992). Early career journalists recognise their lack of agency, but through their observation of newsroom nomos (culture), death knock doxa (rules), and their own death knock experience, their habitus may change. Importantly, their habitus, understood as their instinct, ‘second sense’ or second nature (Johnson, Citation1993, p. 5) evolves with socialisation. They recognise, through their own practice, the conditions and context in which they want to do death knocks, including their approach, their methods, and their justifications. As they acquire capital (status) in the newsroom, they may seek to influence the nomos and the doxa, that is, not just their own death knock practice but the newsroom’s death knock practice.

Professional identity

The third dimension, Professional Identity, has two essential elements: journalists’ ethical standards, and death knock reframing. The literature shows that remembering the ‘higher purpose’ of the job is an adaptive coping strategy used by journalists who experience trauma (Seely, Citation2019), and the study confirms that journalists doing death knocks find solace in their professionalism. One commented: ‘The way I cope with the whole process is to make sure the family or loved ones are comfortable and at ease and then I write a story that accurately reflects and celebrates the person they have lost’.

The journalist’s moral compass

Crucial to the journalist’s sense of professional identity is their ‘moral compass’ (Pearson, McMahon, & O’Donovan, Citation2018). The literature shows that valorisation of professional identity, and, with it, ethical standards, can strengthen a journalist’s resilience in traumatic situations and minimise the likelihood of moral injury (Drevo, Citation2016) and post-traumatic harm (Muller, Citation2010). Therefore, a model for an ethical death knock hinges on mitigation of moral injury to journalists through valorisation of their professional identity. Journalists mostly recognise their duty to perform the death knock sensitively (Duncan, Citation2020), generally wanting to see themselves as decent and honest rather than exploitative, but according to Duncan and Newton (Citation2017) the nature of bad news necessitates their engaging in intrusive practices. This is part of the tension at the heart of the death knock, identified in the paradox of intrusion/inclusion that exemplifies this complex journalistic practice.

Reframing the death knock

A second element in the Professional Identity dimension is death knock reframing, which is called for in the literature (Barnes, Citation2016). Logically, a death knock cannot be ethical to journalism practitioners if it is deemed illegitimate by those practitioners. Researchers have argued for a better explanation of the role of the journalist in the death knock, including to practitioners themselves, as it is neither clearly defined or socially accepted (Browne, Evangeli, & Greenberg, Citation2012) and journalists’ distress arises not just from intruding on grief but ‘in their perception of their role at this time’ (Duncan & Newton, Citation2010, p. 444). An ethical death knock requires a moral justification, according to the literature (Duncan & Newton, Citation2017) and the Australian study. However, the research acknowledges there are multiple frames for the death knock that offer multiple justifications. It may be the case that journalists can, simultaneously, believe that the death knock is ‘initiation/rite of passage’, ‘commercial imperative’ and ‘public service journalism’. There is a role for journalism educators to reframe the death knock as a legitimate journalistic practice within an ethical framework, and there is a role for practitioners, particularly at senior levels, to engage in this reframing activity genuinely and without cynicism, through critical reflection of practices in their field that impact journalists and the reasons for those impacts. Valorisation of professional identity and death knock reframing are activities that shape, and are shaped by, the habitus of individual actors and of the field.

Habitus as professional identity

Bourdieu’s habitus accounts for how a journalist’s professional standing and experience shapes their behaviour and can, ultimately, influence their newsroom, through acquired capital and increased agency. Different frames employed by journalists valorise different forms of capital. In championing ethical behaviour, journalists valorise ‘cultural’ capital. In prioritising the commercial imperative, they valorise economic capital (news as business). Further, the ‘initiation’ frame valorises the nomos (culture) of self-reliance and the idea that journalists must learn the doxa (rules) independently. In the context of habitus influencing fields, Bourdieu says that actors are generally initially unquestioning of the doxa that organise the field, but that fields are sites of contestation and ‘arenas for struggle’ (Bourdieu & Wacquant, Citation1992, p. 97) and that, with acquired capital and increased agency, journalists as strategic actors playing a game may influence their field (Bunce, Citation2019). Bourdieu also recognises, as do journalists in the Australian study, that there are limits to the capacity of actors to bring about change if that change runs counter to the needs of the field.

The final dimension, Professional Identity, is premised on the connection between the journalist’s view of themselves and their behaviour; this is their habitus. Journalists say they want to behave ethically, and if they are placed in situations that challenge their ethical standards (potentially, the death knock), they can justify it providing they behave ‘professionally’, which is synonymous with ‘ethically’. Journalists, through their changed habitus and with acquired capital and increased agency, may change the field through their impact on nomos and death knock doxa. However, key to the Professional Identity dimension is a clearer frame for the death knock as a legitimate journalistic practice within an ethical framework.

How the model can mitigate moral injury

Mitigating moral injury to journalists can be achieved through bolstering their capacity to do the task and valorising their professional identity overall. Moral injury results from ethical breaches, so minimising moral injury must be concerned with minimising moral breaches. Journalists’ capacity to do death knocks is bolstered by all dimensions of the model: Preparations (as it gives journalists key skills and support), Precursors (as it sets up ideal conditions) and Professional Identity (as it valorises ethical behaviour and reduces the stigma of death knock practice).

Ethical breach and moral injury

Moral injury occurs when an individual feels driven to breach their ethical values (Drescher et al., Citation2011; Litz & Kerig, Citation2019; Litz et al., Citation2009). The literature reveals links between journalists’ ethical breaches, moral injury, and post-traumatic reactions, particularly if breaches were due to newsroom directives (Backholm & Bjorkqvist, Citation2012) and finds that journalists face increased pressure if they are forced to sensationalise an event or pressure distressed people for an interview (Browne et al., Citation2012). Key to mitigating the risk of moral injury in journalists is having a clear sense of purpose, strong connection with peers, and feeling supported by managers (Smith et al., Citation2023). The Australian study confirms journalists’ distress at their ill-preparedness and lack of agency in death knock practice, and these factors exemplify failures of newsroom nomos (the culture of self-reliance) and doxa (rules that must be learned independently).

Habitus as change agent

Bourdieu’s field theory helps inform the knowledge necessary for the model as it allows for the mapping of actors’ dispositions and behaviours (habitus) and their impact, through acquired capital and increased agency, on the structure (newsroom). Importantly, habitus is both an outcome of the structure and a contributor to it (Wacquant, Citation1993). Just as habitus structures and is structured by an individual’s dispositions, their behaviour and their position in the social structure, the social structure itself is maintained and changed by the habitus of individuals. Journalists, at first slavish to the rules (doxa) they inherit, can, through agency and capital, eventually influence those rules. For example, a survey respondent related how, as a young reporter, they felt forced by their chief of staff to repeatedly ‘knock’ a family, and commented, ‘These days, I would have told her to get stuffed’, exemplifying a change in habitus and acquired capital that led to influence in the newsroom.

Knowledge of the way habitus changes and can bring about change informs the ethical death knock model where the behaviour and dispositions of journalists (habitus), through their agency and capital, can bring about change in practice. The model therefore seeks to mitigate moral injury through laying bare the failures of newsroom nomos (a culture of self-reliance instead of support) and valorising the cultural capital that journalists do (professional identity equals ethical behaviour).

Limitations and further research

The model does not account for the influence and intersection of the economic field and the technological field on the journalistic field. While journalists recognise their limited agency if their desires run counter to the desires of the newsroom, the model does not indicate which might dominate when the economic imperative of the death knock (‘stories sell’) comes into conflict with the public service journalism imperative (‘stories do good’). Further, the economic field is the site of the failing business model of journalism, and the technological field intersects with the economic field (in social media). As newsrooms shrink (through convergence and digitisation), journalists must do more with less, and the immediacy and ease of social media could dominate slower, time-consuming face-to-face interviewing. The model’s effectiveness regarding the ‘digital death knock’, or social media as the site of death knock practice, is therefore an area of further analysis.

The model demands training and support but does not address whether the educative aspect of the Preparations dimension (training, knowledge, and advice) should be the responsibility of stretched newsrooms and/or university programmes with crowded curricula, and whether the well-being aspect of that dimension (support) will fall to media companies through formal or informal structures, or to individual journalists accessing peers and professionals.

There is a challenge in genuinely reframing the death knock, and understanding the extent to which a more positive frame such as public service journalism might be widely understood. While researchers and practitioners may understand the ‘value’ of the death knock beyond the commercial imperative, it may be more difficult to convince bereaved families and critics of media intrusion that the practice can do good and is therefore ethically defensible. However, it is not the intention of the researcher to mount an argument that the death knock is ethical per se, and that this argument ought to be persuasive to those outside journalism. Rather, reframing is for the benefit of practitioners themselves, for whom moral injury might be avoided if their professional (ethical) identity is valorised and they are able to practice in an ethical context. While it is likely that ethical journalism will benefit bereaved families and communities more broadly, it is unlikely that journalists will escape criticism for intrusive practices such as the death knock.

There is a broader question about whether the application of the ethical death knock model in newsrooms can achieve meaningful change in practice, or whether more is needed. Will journalists who adhere to the model (and have supervisors who adhere to the model) conduct what they deem to be ethical death knocks and thereby mitigate their own risk of moral injury, or is that failing to account fully for the conflict and contestation within the journalism field, and of the intersection of the journalism, technological and economic fields? An attempt to answer that question will be made through an analysis of comments of interviewees who remain sceptical that meaningful change will occur without ‘a big stick’ in the form of legislative change (to strengthen citizens’ privacy protections) or normative change (whereby journalism’s professional organisations modify guidelines that justify intrusion in the public interest). This analysis will be reported in a forthcoming paper.

Conclusion

This paper has proposed an ethical death knock model that can minimise moral injury to journalists by strengthening their capacity, valorising their professional identity, and positively reframing the death knock within the profession. It is not argued that an ethical death knock can be achieved without context, and the model seeks to better define the context that journalists find acceptable. Bourdieu’s field theory has aided the mapping of journalists’ dispositions and behaviours (habitus) and their broader impact on the newsroom (structure). Habitus is at the heart of the model. New journalists are beholden to death knock doxa (rules they must learn themselves) and newsroom nomos (a culture in which they must look after themselves) and have not attained the necessary habitus to do the death knock. Their desire for training, knowledge, advice, and support (encapsulated in the Preparations dimension) recognises the failure of doxa and nomos to socialise them into the field. As they gain death knock experience, accumulate capital, and increase their agency, their habitus changes. In highlighting the methods and motivations that they think result in an ethical death knock (encapsulated in the Precursors dimension), journalists are asserting their increased agency and expending their acquired capital. And because habitus is both an outcome of the structure (the journalist’s habitus is shaped by the newsroom) and a contributor to it, the journalist’s habitus can also shape the newsroom. In the third dimension of the model Professional Identity, Bourdieu’s theory envisages experienced and well thought-of journalists championing and valorising professional identity as ethical behaviour and the death knock being reimagined by practitioners as legitimate journalistic practice. The model can mitigate moral injury to journalists by enabling and prioritising ethical conduct, thereby strengthening their resilience in challenging situations and minimising harm from ethical breaches. Regarding death knock practice, the habitus of the ethical journalist can become the nomos of the ethical newsroom.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Backholm, K., & Bjorkqvist, K. (2012). The mediating effect of depression between exposure to potentially traumatic events and PTSD in news journalists. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 3(1). doi:10.3402/ejpt.v3i0.18388

- Barnes, L. (2016). Journalism and everyday trauma: A grounded theory of the impact from death-knocks and court reporting ( Doctoral thesis). Auckland University of Technology. Retrieved from https://openrepository.aut.ac.nz/handle/10292/10228

- Barnes, L., Tupou, J., & Harrison, J. (2019). Rolling with the punches: Why it is ethical to practise ‘Death Knocks’. Asia Pacific Media Educator, 26(1), 51–64. doi:10.1177/1326365X16640345

- Belch, L. (2015). Reporting the death knock: Ethics, social media and the Leveson inquiry ( Master’s thesis). Edinburgh Napier University. Retrieved from https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/74028703.pdf

- Benson, R., & Neveu, E. (2005). Bourdieu and the journalistic field. Cambridge: Polity.

- Bourdieu, P. (1983). The forms of capital. In J. G. Richardson (Ed.), Handbook of theory and research for the sociology of education (pp. 241–258). New York: Greenwood Press.

- Bourdieu, P. (1986). The forms of capital. In J. G. Richardson (Ed.), Handbook of theory and research for the sociology of education (pp. 241–258). New York: Greenwood Press.

- Bourdieu, P. (1990). The logic of practice. California: Stanford University Press.

- Bourdieu, P. (1994). L’Emprise du journalism. Actes de la recherche en sciences sociales, n° 101–102(1), 3–134. doi:10.3917/arss.p1994.101n1.0003

- Bourdieu, P. (1998). Practical reason: On the theory of action. California: Stanford University Press.

- Bourdieu, P., & Wacquant, L. J. (1992). An invitation to reflexive sociology. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Browne, T., Evangeli, M., & Greenberg, N. (2012). Trauma-related guilt and posttraumatic stress among journalists. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 25(2), 207–210. doi:10.1002/jts.21678

- Bunce, M. (2019). Management and resistance in the digital newsroom. Journalism, 20(7), 890–905. doi:10.1177/1464884916688963

- Castle, P. (1999). Journalism and trauma: Proposals for change. Asia Pacific Media Educator, 7, 143–150.

- Castle, P. (2002). Who cares for the wounded journalist? A study of the treatment of journalists suffering from exposure to trauma ( Master’s thesis). Queensland University of Technology. Retrieved from https://eprints.qut.edu.au/36436/

- Drescher, K. D., Foy, D. W., Kelly, C., Leshner, A., Schutz, K., & Litz, B. (2011). An exploration of the viability and usefulness of the construct of moral injury in war veterans. Traumatology, 17(1), 8–13. doi:10.1177/1534765610395615

- Drevo, S. (2016). The war on journalists: Pathways to posttraumatic stress and occupational dysfunction among journalists ( PhD thesis). University of Tulsa.

- Duncan, S. (2012). Sadly missed: The death knock news story as a personal narrative of grief. Journalism, 13(5), 589–603. doi:10.1177/1464884911431542

- Duncan, S. (2020). The ethics. In J. Healey (Ed.), Trauma reporting: A journalist’s guide to covering sensitive stories (pp. 186–198). London: Routledge.

- Duncan, S., & Newton, J. (2010). How do you feel? Preparing novice reporters for the death knock. Journalism Practice, 4(4), 439–453. doi:10.1080/17512780903482059

- Duncan, S., & Newton, J. (2012). Hacking into tragedy: Exploring the ethics of death reporting in the social media age. In R. Keeble & J. Mair (Eds.), The phone hacking scandal: Journalism on trial (pp. 208–220). Suffolk: Abramis.

- Duncan, S., & Newton, J. (2014). Emotion and trauma in reporting disaster and tragedy. In The future of humanitarian reporting (pp. 69–74). City University London. Retrieved from https://openaccess.city.ac.uk/id/eprint/3647/

- Duncan, S., & Newton, J. (2017). Reporting bad news: Negotiating the boundaries between intrusion and fair representation in media coverage of death. New York: Peter Lang.

- Dworznik-Hoak, G. (2020). Making sense of Harvey: An exploration of how journalists find meaning in disaster. Newspapers Research Journal, 41(2), 160–178. doi:10.1177/0739532920919822

- Harcup, T. (2014). A dictionary of journalism. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Johnson, M. (1999). Aftershock: Journalists and trauma. The Quill, 87(9), 14–18.

- Johnson, R. (ed.). (1993). The field of cultural production: Essays on art and literature. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Keats, P. (2012). Journalism. In C. R. Figley (Ed.), Encyclopedia of trauma: An interdisciplinary guide (pp. 227–340). Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications.

- Keats, P., & Buchanan, M. (2009). Addressing the effects of assignment stress injury. Journalism Practice, 3(2), 162–177. doi:10.1080/17512780802681199

- Lee, M., Ha, H. E., & Pae, J. K. (2018). The exposure to traumatic events and symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder among Korean journalists. Journalism, 19(9–10), 1308–1325. doi:10.1177/1464884917707596

- Litz, B. T., & Kerig, P. K. (2019). Introduction to the special issue on moral injury: Conceptual challenges, methodological issues, and clinical applications. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 32(3), 341–349. doi:10.1002/jts.22405

- Litz, B. T., Stein, N., Delaney, E., Lebowitz, L., Nash, W. P., Silva, C., & Maguen, S. (2009). Moral injury and moral repair in war veterans: A preliminary model and intervention strategy. Clinical Psychology Review, 29(8), 695–706. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2009.07.003

- McMahon, C. (2016). An investigation into posttraumatic stress and posttraumatic growth among trauma reporting Australian journalists ( Doctoral thesis). Swinburne University of Technology. Retrieved from https://researchbank.swinburne.edu.au/file/f81cb686-cbc1-4437-a159-91a210fcf53f/1/Catherine%20McMahon%20Thesis.pdf

- Moreham, N. A., & Tinsley, Y. (2019). The impact of grief journalism on its subjects: Lessons from the Pike River mining disaster. Journal of Media Law, 10(2), 189–218. doi:10.1080/17577632.2019.1592337

- Muller, D. (2010). Ethics and trauma: Lessons from media coverage of black Saturday. The Australian Journal of Rural Health, 18(1), 5–10. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1584.2009.01117.x

- Novak, R., & Davidson, S. (2013). Journalists reporting on hazardous events: Constructing protective factors within the professional role. Traumatology, 19(4), 313–322. doi:10.1177/1534765613481854

- Osmann, J., Dvorkin, J., Inbar, Y., Page-Gould, E., & Feinstein, A. (2021). The emotional well-being of journalists exposed to traumatic events: A mapping review. Media, War & Conflict, 14(4), 476–502. doi:10.1177/1750635219895998

- Pearson, M., McMahon, C., & O’Donovan, A. (2018). Potential benefits of teaching mindfulness to journalism students. Asia Pacific Media Educator, 28(2), 186–204. doi:10.1177/1326365X18800080

- Rees, G. (2007). Weathering the trauma storms. British Journalism Review, 18(2), 65–70. doi:10.1177/0956474807080949

- Ryfe, D. M. (2018). A practice approach to the study of news production. Journalism, 19(2), 217–233. doi:10.1177/1464884917699854

- Schon, D. A. (1983). The reflective practitioner: How professionals think in action. New York: Basic Books.

- Schon, D. A. (1986). Educating the reflective practitioner. New York: Basic Books.

- Seely, N. (2019). Journalists and mental health: The psychological toll of covering everyday trauma. Newspaper Research Journal, 40(2), 239–259. doi:10.1177/0739532919835612

- Simpson, R., & Cote, W. (2006). Covering Violence. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Smith, E., Wake, A., & Ricketson, M. (2023, February 20). Journalists covering the Turkiye-Syria earthquake may face moral injury. Dart Centre for Journalism & Trauma. Accessed on 25.9.23 Journalists covering the Türkiye-Syria earthquake may face moral injury - Dart Center. https://dartcenter.org/resources/journalists-covering-t%C3%BCrkiye-syria-earthquake-may-face-moral-injury

- Vos, T. (2019). Field theory and journalistic capital. In T. Vos & F. Hanusch (Eds.), The international encyclopedia of journalism studies. New Jersey: Wiley.

- Wacquant, L. J. D. (1993). Bourdieu in America. In C. Calhoun, E. LiPuma, & M. Postone (Eds.), Bourdieu: Critical perspectives (pp. 235–262). Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Watson, A. (2022). The ‘digital death knock’: Australian journalists’ use of social media in everyday reporting. Australian Journalism Review, 44(2), 243–260. doi:10.1386/ajr_00106_7

- Watson, A. (2024). The Death Knock as Emotional Labour - Reframing a “Rite of Passage” to Help Journalists Cope. In Journalism as the Fourth Emergency Service Trauma and Resilience (pp. 109–118). New York: Peter Lang.

- Yates, D. (2023). Line in the sand. Sydney: Pan Macmillan.