Speech-language pathologists (SLPs) have professional responsibilities, including to engage in ethical and evidence-based practices to optimise communication and swallowing amongst individuals and communities. For SLPs in Australia, the CitationSpeech Pathology Australia (SPA) Code of Ethics (2020) emphasises the need for “awareness of the broader context of human rights of the individual” (p. 2) in speech-language pathology practice, as well as “relevant legislation … policies and professional standards” (p. 2). More specifically, SLPs “have an ethical obligation to support people to exercise their human rights” (CitationSPA, 2020, p. 5). Children, as well as adults, have human rights and are afforded additional protections. The skill set and scope of practice of SLPs span many contexts including health, disability, justice, and education contexts, which present opportunities and important obligations for supporting children to realise and enjoy their rights.

Australia has ratified the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC), which is the main international agreement to protect children’s rights (CitationUnited Nations, 1989). One of the articles included in the Convention, Article 12, states as follows:

States Parties shall assure to the child who is capable of forming his or her own views the right to express those views freely in all matters affecting the child, the views of the child being given due weight in accordance with the age and maturity of the child.

For this purpose, the child shall in particular be provided the opportunity to be heard in any judicial and administrative proceedings affecting the child, the views of the child being given due weight in accordance with the age and maturity of the child.

Article 12 places obligations on people who provide education, health care, and other human services, including SLPs, to ensure the rights of children to express their views about matters affecting them.

How much do SLPs know about Article 12 and how to address it? How effective are we as SLPs in fulfilling our obligations with respect to Article 12? How can we be more effective?

This article comprises two parts. Part 1 contains extracts of an interview conducted by Speech Pathology Australia (SPA) with a leading legal scholar about Article 12 and its implementation. Part 2 consists of commentary from two scholars (an educator and an SLP) considering applications of Article 12 in practice.

Part 1: interview with Prof. Laura Lundy

Laura Lundy is a professor in the School of Social Sciences, Education and Social Work at Queen’s University Belfast and the School of Law in University College Cork. She is a lawyer with expertise in international children’s rights with a particular focus on the implementation of the UNCRC in law and policy, education rights, and children’s right to participate in decision-making. Prof. Lundy has written about barriers to fulfilling obligations under Article 12 and developed a model (the Lundy Model) to assist professionals to understand and more effectively meet their obligations (CitationLundy, 2007).

In our interview with Prof. Lundy, we asked her about her concerns with implementation of Article 12, her model, and how SLPs can implement it to more effectively assure the views of children are obtained and listened to when decisions are being made about them. This first section of the paper contains lengthy quotes from Prof. Lundy’s interview, shown in italics, edited by omission of some nonessential content (indicated by the use of ellipses …) and glossed to make her points clearer where needed (indicated by words in square brackets [xxx]).

Perceived challenges and barriers

We started by asking Prof. Lundy why she believes adults are not already fulfilling obligations to truly listen to the voice of children and ensure their right to be heard in decision-making about them.

For some … it’s just a lack of awareness that this is an obligation … it’s [not] really optional. You have to change [your] mindset [to] “I always have to do this, how can I do this best?” … Even if people do know about [Article 12] there still can be some resistance … I’m not sure the extent to which it applies for speech and language therapists … a sense of … it undermining the adults’ professional authority … There can be a sense of “Why would I ask children, when I have the professional training?” I think that relates to a misunderstanding about what it’s [Article 12] about. … It’s just to make sure that the professional is able to do theirjob in a way that they fully understand what’s happening with the child, and what their views and perspectives are.

… For others, I think it’s not fully understanding that it’s an entitlement [of the child] [under the Convention]. … They think that it’s something that is unnecessary … a waste of time … something they just don’t have time for.

… That again I think takes us back to the idea that if you see it as an entitlement, it’s not something that is … extra. It’s something you have to factor in time for.

Sometimes … in relation to participation, [a perception]—that it’s something intensely complex that you have to be specially trained for, and actually speech and language therapists are a really good example of why we shouldn’t think like that, because it’s at the heart of what this group of professionals do—communicate and communicate well with people, including children, and that is something that actually should just be a natural, inherent part of the job.

Fulfilling our obligations to children: the Lundy Model

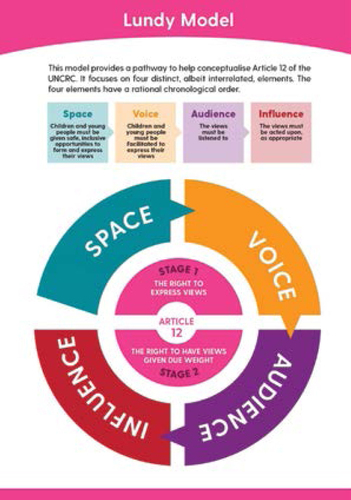

To assist people to better understand and fulfil their obligations, Prof. Lundy created what has become known as “the Lundy Model” (CitationLundy, 2007).

Prof. Lundy explained the model: I came up with the idea that if we want to fully implement [Article 12], we need four things, and they have a rational chronological order: space, creating safe and inclusive opportunities for children to be heard; voice … and a choice of ways of expressing themselves. … I think speech and language therapists are very good at … and also that they understand the issues. That really is the first part of Article 12. The right to express your view.

And then we have the second part, which is the obligation on the adults to give children’s views due weight in accordance with the age and maturity [of the child], and for that I felt the appropriate concepts were audience and influence. An audience is obviously about good listening, but it’s also about making sure the children’s views get to the right person, and so that might be the individual speech and language therapist, but it might be somebody else. It might be the teacher; it might be the parent. It might be someone in the broader system of support for the child, because the audience is the person who has the power to bring about the change that is needed, that the child wants to see.

Finally, the whole degree of influence, and that is where we give children’s views due weight. I think often we’ve become very good at thinking we’re listening to children because it is part of professional training. You know that you’re good at asking questions … really good at listening, [but] are we really good at then actually taking what children say seriously? … So when a child comes in, there’s probably a whole set of assumptions about what the child needs [from our professional perspective]. … Sometimes children will want things that are not good for them, maybe that they just don’t want the therapy, and they don’t want to do it. … And I think you’ve got to be respectful of that by still understanding and explaining why this is a good thing for now and for the future and not to force [the child]. So it’s to what extent can you accommodate and … not going with [an attitude of ] “I’m the professional [and I know best]”.

Feedback and accountability

Prof. Lundy believes that feedback to children about their input is critical, and in her paper (CitationLundy, 2018), she discusses the importance of four “Fs” in adults’ feedback to children:

full—adults should provide details about what was considered, what will happen, and explanations for why;

friendly—children should receive feedback on their views presented in a child-friendly manner;

fast—children should receive a “speedy initial response … that acknowledges their involvement, any initial progress and next steps” (p. 350);

followed up—feedback should not be a one-off event but rather the “beginning of some sort of ongoing

conversation … that lasts for the duration of the policy and decision-making process” (p. 350).

In the interview, Prof. Lundy explained,

“From a human rights perspective, it’s ultimately about accountability. And in the feedback process, that’s where we are accountable. That’s where we say “You know you told us X, and this is what we heard, and this is what we’re going to do, and this is what we can do. And this is why … and this is what’s going to happen next”. [So] those four concepts [in the Lundy Model]: space, voice, audience, influence, supplemented by really good feedback.”

Engaging with families: considering the views of parents and children

Prof. Lundy believes we need to work closely with parents in ensuring children’s rights to express views.

In the broader children’s rights domain, sometimes parents’ rights and children’s rights are pitched against each other, and that’s deeply unhelpful, and it’s not the way the Convention itself is written. In fact, it’s a provision in the Convention that their parents and guardians have a right and a duty to provide guidance to the child in the exercise of their rights. … It’s really important we engage with parents themselves. I want to say that first and foremost. But what’s also really important, and that’s why [children] have independent rights and an independent convention, [is] that the child is heard independently, because sometimes parents have perspectives or wishes that may not sit with exactly what the child needs and it’s really important to hear both. … I think it could be a skill set—understanding and enabling, even with the presence of a parent, to create the space [for the child to express their views].

Prof. Lundy went on to recount:

One of my children attended a speech and language therapist and they were intensely skilled at making sure that … they found out what it was that my child really wanted and needed. … I was watching that particular process with great admiration. … It’d be perfectly appropriate at times to say, “let’s just talk to you, and then I’ll talk to mum or dad” … With a younger child, you’re going to have a parent there. … [We can] say to the parent, “now we’re just talking to [the child]”. It’s all about creating the conditions where the child is comfortable enough to say what they really think, because it may be that the parent has a particular perspective on what the child needs and has told the child that “we’re in here to get you X” … Then putting options in front of the child and the parent, so they can work through if X is an option. But actually, “here are other options that might be better for you right at the minute”.

Applying the Lundy Model in speechlanguage pathology

We asked Prof. Lundy how SLPs could use her model to improve our effectiveness in meeting our obligations under Article 12. Prof. Lundy said her model is versatile in its application:

[It] is successful [because] people are able to colour themselves into it. … people read themselves into the concepts. So what, for instance, creating a safe space looks like for a speech and language therapist is very different to, for example, perhaps an early childhood teacher, or maybe a police officer, or some other professional who has direct contact with children. … You need to say, in my practice … whether I’m in the school or I’m in a clinical or a therapy setting, “what would that [safe and inclusive space] look like?” … That’s up to the professional to think about. … “Who could be the audience for the child in the context? … Who else am I communicating with?”

That’s what’s going to make the culture shift; it’s people owning it within context and working with children to make sure it is as pertinent and relevant to those children in that space as it can be.

We asked Prof. Lundy about ways of ensuring children’s access to information. She said:

the Convention talks about the child’s right to seek, receive, and impart information in a medium of choice … different media, including art. That’s why it’s in the model, because I specifically connected to Article 13 [of the Convention]. But in my own work in the past couple of years I have done a lot of work on child-friendly documents and child-friendly information as I feel it’s a missing … a sometimes neglected component of delivering meaningful participation [for children].

Prof. Lundy went on to give an example of a school involving children’s voices in rewriting documentation for the school:

They’re very tuned in to different communication needs, you know … they have 15 languages in the school … They’re also getting it translated … . So there is a lot that could be done, in different contexts to ensure that children get information that they can understand, and that’s crucial for Article 12, because if [children] don’t understand the issues, they can’t come to a clarified position.

Towards the end of the interview, Prof. Lundy commented:

To me, speech and language therapists … are so important for Article 12. … You know the reality of what you do is absolutely fundamental because it is about enabling the child to express themselves, which is “voice”. So you’ve got this profession who are critical … to everything that might happen to that child. … And I think [you also have] the ability to model really good practice because of your skill set.

Part 2: commentary from Dr. Clare Carroll and A/Prof. Jenna Gillett-Swan

We sought to further explore SLPs’ practices in supporting children’s rights to express their views about matters that affect them, following Prof. Lundy’s comments regarding the important role of Article 12 for SLPs. The second part of this article comprises commentary from two scholars, Dr. Clare Carroll and Associate Professor Jenna Gillett-Swan, who have thought deeply about observing our obligations under Article 12 of the Convention in their daily practice.

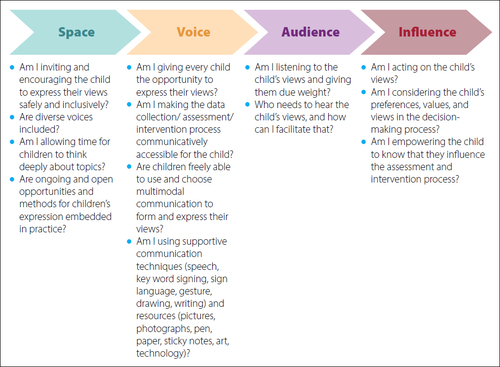

As practitioners, we need to reflect on our daily practice and consider the four quadrants of the Lundy Model (CitationLundy, 2007). What this means is that before, during, and after interactions with children, we need to consider space, voice, audience, and influence. In , we provide some questions to prompt reflection on these considerations.

One of the many great things about the Lundy Model is not only its attention to ensuring the opportunity and platform from which views can be provided, but in articulating the obligation of those seeking voice to ensure who needs to hear it is among those listening and for these listenings to be acted upon. Noticing the disconnect in practice between the elicitation of perspectives and listening, truly listening, hearing, and acting upon what is said makes this aspect one of the drivers of our work with children and young people and the educators, schools, and communities working with them. A brief description follows of three of the angles we (Clare and Jenna) take to support the implementation of children’s Article 12 rights in practice in different contexts, addressing different aspects of the Lundy Model.

Space and voice: understanding and overcoming challenges along the journey

First, let’s consider working with individuals and organisations where they are at. People working within child- and youth-connected contexts (e.g., schools) generally fall within one of four groupings:

new to student voice/children and young people’s perspectives but receptive;

dabbling/ad hoc (e.g., student input is sought sporadically or for specific purposes);

looking to extend/grow/build upon what they are doing; or

resistant to student voice/children and young people’s perspectives.

Within organisations, and sometimes even among children and young people themselves, there are often several combinations of these positions on voice. For example, in Jenna’s work, recognising that everyone may not hold the same underlying philosophy when it comes to the reasons for, and purpose of, voice-inclusive practices aids in meeting people where they are at. For example, for children and young people, past experiences of tokenism, silencing, or exclusion may contribute to their feelings of mistrust or scepticism about voice-seeking practices. Similarly, children and young people can feel significant pressure if tasked with “representing” the voices and perspectives of a wider cohort (e.g., representing the views of “students living with disability”) or representing the entire student body.

For adults, some may feel silenced—for example, by decisions being made about them or the work they do without the opportunity to provide their input, expertise, or insights. This may contribute to being reluctant or resistant to offering voice opportunities to others until they feel heard. Others resistant to student voice may question how worthwhile student contributions may be or may be fundamentally against involving children and young people due to perceptions about a lack of maturity, insight, or experience. Some adults may genuinely believe that they know best and that their decisions are in children’s best interests despite not involving children and young people themselves in determining what their interests and perspectives may be.

We know that for children with speech, language, and communication needs, sharing their views can be challenging. CitationLyons and colleagues (2022) advocate that we need to really listen to children with speech, language, and communication needs (SLCN) and tune in to what they are telling us. They argue that the use of qualitative research can create the space to explore children’s lived experiences, and their preferences and values, and can promote public patient involvement (CitationLyons et al., 2022). Qualitative research also encourages reflexivity. In clinical practice, reflective practice is also encouraged. Being reflective means that we must go beyond the use of assessment and intervention methods and challenge our beliefs, assumptions, attitudes, and biases about how the child is invited and encouraged to be involved and about how we view the child’s capacity. Critically reflecting on our use of space in research and/or in clinical practice is the starting point for making changes to embed safety and inclusion at the heart of what we do. This critical reflection is an ongoing journey within our authentic dialogue with each child.

Regardless of what personal positions adults hold about children’s and young people’s capacity, agency, power, and autonomy (see CitationGillett-Swan & Sargeant, 2019), there remains an international legal obligation on states’ parties and their representatives, such as teachers and those working with children and young people, for children and young people to express their views and have these views heard and taken seriously in all matters affecting them, not just those views that are attractive or convenient for adults. This is one of the ways that the Lundy Model aids in providing that practical guidance towards fulfilling these obligations regardless of where you, or those you work with, are on the journey.

Space, voice, and audience: respecting diversity and creating opportunities for every child

Second, we must ensure that, regardless of intention or motivation, there is recognition that “voice” does not only refer to the written or spoken word. Body language, visual depictions, artefact curation, or alteration (e.g., gathering and/or altering a collection of objects or images to show an experience), sounds, and gestures are all valid and important ways of communicating voice. Similarly, the choice to remain silent can be an incredibly powerful expression of a young person’s views (e.g., see CitationHanna, 2022).

SLPs are uniquely placed to advocate for the use of multimodal communication to amplify the voice of children with SLCN and to ensure their communicative participation. The child can use drawing, talking, photographs, videos, text, nonverbal communication, signing, communication apps, vocal signals, and/or verbal signals. Using participatory methods (CitationMerrick et al., 2019) promotes equality of relationships and aims to reduce power differentials in the research process such that researchers share responsibility and knowledge with participants. SLPs must continually consider and advocate for augmentative and alternative communication (AAC) for the children that we work with in order to ensure that their voices are shared and views considered. McCormack et al. (2018) argued that it is the “lack of voice” (p. 142) for some children that excludes them. We know that there are multiple ways for children to express themselves, and we need to do more to ensure that all children can share their voice (CitationMcCormack et al., 2022; CitationMerrick et al., 2019; CitationTwomey & Carroll, 2018).

Alongside this recognition of voice as more than written or spoken words is the recognition that children and young people also do not need to express themselves in a way that corresponds to adult comprehensibility and preferences. This can sometimes create some tension in what could be termed as the convenience of voice, whether that convenience relates to selective perspectives chosen only for their likelihood of aligning with or confirming the decision that those initiating want, or perhaps the seeking and sharing of views only from those considered to have sufficient “maturity” or linguistic acumen to offer what some may consider a “comprehensible” view, or something else.

The inclusion of child voice is very important and central to the work both of us have done as researchers and practitioners. For example, I (Clare) am an Irish registered speech and language therapist and educator on a preregistration speech and language therapy program, and I located the Lundy Model as a cornerstone for including neurodiverse preschool children in my doctoral research. I wanted to understand the processes that underpinned early intervention practice and strongly believed that this could only be achieved if professional voice, parent voice, and child voice were included in the research. Citing the Lundy Model and the UNCRC supported the lengthy ethical approval process. I wanted to create the space for child voice. I successfully included neurodiverse children using a wearable camera (Microsoft SenseCam), as a participatory visual method, so that the children’s views could be expressed and included (CitationCarroll, 2018; CitationCarroll & Sixsmith, 2016). At the time, this was a novel approach in giving the children voice in research. The camera took pictures automatically, and I gained a visual representation of the child’s world. I then used these visuals in subsequent interactions with the children and their parents. This tool promoted equality of relationships and reduced power differentials in the research process as I shared responsibility and knowledge with the children. The inclusion of child voice complemented and added to the views of parents and professionals.

When adults are reluctant or resistant to student perspectives, there can be a tendency to seek only those perspectives that are considered accessible, convenient, or “palatable”—if children’s and young people’s perspectives are even sought at all. The Lundy Model aids in reminding those working with children and young people that diversity in views and representations of those views is also central to supporting children’s and young people’s Article 12 and Article 13 rights in practice. It is important to remember that it is not just those views that are easy to access or from those who communicate in a particular way that should be sought. It is up to adults to meet children and young people where they are at and through their preferred ways of communicating rather than the other way around.

Audience and influence: the responsibility of all

Third, there is a need to build in intentionality in developing sustainable practices that are not just the responsibility of those interested in doing it, but the responsibility of all. Supporting each child’s right to have their views sought and taken seriously needs to be embedded authentically within the everyday practices and interactions of adults and children within each of the environments in which they inhabit and interact. When you have created space, voice, and audience for the child to share their hopes and priorities, what is next? As a researcher, we have a responsibility to disseminate the research process, findings, and implications to others. As a practitioner, we have a responsibility to use the preferences, views, and priorities shared by the child “to create new priorities for everyone involved and allow their [the child’s] intervention to be both functional and inclusive” (Carroll, in press).

These practices should be seen as integral to day-to-day experiences as well as part of an underlying philosophy of participatory voice inclusion. There may be disciplinary nuances associated with how this plays out. For example, the ways that classroom teachers may embed practices in daily classroom routines may be different to how school guidance officers/school counsellors embed participatory practices alongside and within their interactions with children and young people. Participatory rights practices can also be embedded within technologically enhanced environments in practical ways such as through reciprocal knowledge and skill transmission (see CitationGillett-Swan & Sargeant, 2018).

Conclusion

SLPs have important skills and a fundamental role to play in supporting children to understand issues that affect them and express their views, as well as building capacity among other adults to advocate for and amplify children’s voices. SLPs are urged to consider the Lundy Model and reflective questions in in relation to their own contexts, current practices, and aspirations for practice and consider their professional and ethical responsibilities when working with children. Creating safe and inclusive spaces, allowing for flexibility in individual preferences and adaptation of mode and means of communication, and sufficient time for this to occur, all contribute to embedding voice-inclusive and voice-respecting practices in everyday experiences and interactions between children and adults. Doing so also contributes to ensuring attention is paid, and progress made, towards the duties and obligations required of those working with children and young people under the UNCRC in addressing Article 12, as well as adherence to the professional ethical responsibilities of SLPs.

To listen to Dr. Laura Lundy’s interview, head to: https://bit.ly/DrLauraLundyInterview

Acknowledgement

The authors wish to thank Professor Laura Lundy for her valued contributions.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Lindy McAllister

Lindy McAllister, Emeritus Professor, The University of Sydney, Australia.

Clare Carroll

Clare Carroll, Assistant Professor in the Discipline of Speech and Language Therapy, University of Galway, Ireland.

Jenna Gillett-Swan

Jenna Gillett-Swan, Associate Professor and co-lead for the Health and Wellbeing Program in the Centre for Inclusive Education, Queensland University of Technology, Australia.

Nicole McGills

Nicole McGill, Senior Advisor Evidence-Based Practice and Research, Speech Pathology Australia.

References

- Carroll, C. (2018). Let me tell you about my rabbit! Listening to the needs and preferences of the child in early intervention. In M. Twomey & C. Carroll (Eds.), Seen and heard: Participation, engagement and voice for children with disabilities (pp. 191-242). Peter Lang.

- Carroll, C. (in press). Positioning the views of children with developmental disabilities at the centre of early interventions. In A. Callus & A. Beckett (Eds.), Exploring different aspects of the lives of disabled children. Routledge.

- Carroll, C.,& Sixsmith, J. (2016). Exploring the facilitation of young children with disabilities in research about their early intervention service. Child Language Teaching and Therapy, 32(3), 313–325. https://doi.org/10.1177/02656590166383

- Gillett-Swan, J. K.,& Sargeant, J. (2018). Voice inclusive practice, digital literacy, and children’s participatory rights. Children & Society, 32(1), 38–49. https://doi.org/10.1111/chso.12230

- Gillett-Swan, J. K.,& Sargeant, J. (2019). Perils of perspective: Identifying adult confidence in the child’s capacity, autonomy, power and agency (CAPA) in readiness for voice-inclusive practice. Journal of Educational Change, 20(3), 399–421. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10833-019-09344-4

- Hanna, A. (2022). Seen and not heard: Students’ uses and experiences of silence in school relationships at a secondary school. Childhood, 29(1), 2438. https://doi.org/10.1177/09075682211055605

- Lundy, L. (2007). “Voice” is not enough: Conceptualising Article 12 of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child. British Educational Research Journal, 33(6), 927–942. https://doi.org/10.1080/01411920701657033

- Lundy, L. (2018). In defence of tokenism? Implementing children’s right to participate in collective decisionmaking. Childhood, 25(3), 340–354. https://doi.org/10.1177/09075682187772

- Lyons, R., Carroll, C., Gallagher, A., Merrick, R.,&Tancredi, H. (2022). Understanding the perspectives of children and young people with speech, language, and communication needs: How qualitative research can inform practice. International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 24(5), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1080/17549507.2022.2038669

- McCormack, J., Baker, E.,& Crowe, K. (2018). The human right to communicate and our need to listen: Learning from people with a history of childhood communication disorder. International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 20(1), 142–151. https://doi.org/10.1080/17549507.2018.1397747

- McCormack, J., McLeod, S., Harrison, L. J.,& Holliday, E.L. (2022). Drawing talking: Listening to children with speech sound disorders. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 53(3), 713–731. https://doi.org/10.1044/2021_LSHSS-21-00140

- Merrick, R., McLeod, S.,& Carroll, C. (2019). Innovative methods. In R. Lyons & L. McAllister (Eds.), Qualitative research in communication disorders: An introduction for students and clinicians (pp. 387-405). J &R Press.

- Speech Pathology Australia. (2020). Code of ethics. https://bit.ly/SPACOE2020

- Twomey, M.,& Carroll, C. (2018). Seen and heard: Participation, engagement and voice for children with disabilities. Peter Lang.

- United Nations. (1989). Convention on the rights of the child.