ABSTRACT

The first living condition-survey among people with intellectual disability in Sami areas in Norway was conducted in 2017. The purpose of this article is to present and discuss results from the living-condition study, with a focus on the results related to mental health and bullying as a risk factor for poor mental health among people with intellectual disability and a Sami background. We have conducted a questionnaire survey among people with intellectual disability in Sami areas, with and without a Sami background (N = 93). People with intellectual disability have poorer mental health compared to the population in general and those with Sami background have the poorest mental health. Bullying is one of several factors that increase the risk of poor mental health among people with intellectual disability and Sami background. Having a Sami background makes people with intellectual disability more disposed to poor mental health.

Background

This article aims to provide new knowledge about mental health among people with intellectual disabilities in Sami areas in Norway. There is a lack of knowledge about this, although we know that both people with intellectual disabilities and the Sami people have poorer living conditions in several areas compared to the general population. The article is based on a survey of living conditions among people with intellectual disabilities in Sami areas in Norway [Citation1]. This is the first living-condition study in Norway in which people with intellectual disabilities could answer the survey themselves. It is also the first survey of living conditions among this group of people that focuses on the meaning of a Sami background.

The Sami are the indigenous ethnic population of northern Scandinavia, named as Sápmi. The size of the Sami population in Norway today is estimated to be approximately 60,000 [Citation2]. The Sami people have their own culture and traditional way of living, although most Sami people today are a part of Norwegian society and their way of living. Only a small group are living the traditional ways of life, based on reindeer herding and fishing. The Sami have their own language, but most of them speak Norwegian fluently. Only about 25,000 Sami speak a Sami language [Citation3]. Over a period of several decades, the Sami were exposed to comprehensive discrimination and assimilation [Citation3]. Since the 1980s, the situation has changed, and in recent decades there has been an ethnic and cultural revival. The Sami people are now generally treated as equals. Still, the Sami people experience discrimination.

Intellectual disabilities is a common term for different kinds of diagnoses and health states that cause reduced cognitive capacity. This group often have reduced capacity to manage everyday life situations and require some level of support for daily functioning. About 1%–3% of the population has this disabilities [Citation4]. In Norway, all citizens, including those with an intellectual disabilities, have a legal right to home healthcare services, organised by the municipalities. A large proportion of this group live in a group home [Citation5]. Self-determination is about the ability to make a decision for oneself without influence from outside. Research shows that many of those living in a group home experience lack of self-determination when it comes to were to live, what they shall do during the day, and who should assist them [Citation5,Citation6]. In general, adults with intellectual disabilities are less self-determined than the general population. They have fewer opportunities to make choices and express preferences across their daily lives.

Mental health problems are about mental illness, but also about challenges in everyday life and coping with different situations [Citation7]. People with intellectual disabilities have a higher risk of mental illness and have poorer mental health than the general population [Citation6,Citation7]. The white paper nr. 45, 2012–2013 [Citation8] points out that this group experience fear and depression more often than the rest of the population. Research addressing the mental health of people with intellectual disabilities focus on how the intellectual disability causes a congenital vulnerability to mental health problems [Citation9]. The Norwegian Directorate for Children, Youth and Family Affairs [Citation4] also points to the fact that these people are more vulnerable when it comes to mental health problems because of a reduced capability to cope with their problems or seek help. Mental health problems cause a lot of pain. It also often manifests in other ways for people with intellectual disabilities. Increased serious behaviour problems, self-harm and loss of skills are common symptoms [Citation7]. These symptoms can easily be misunderstood or overlooked [Citation9]. When it comes to the Sami people, some studies find that they have poorer mental health than the population in general [Citation10], while others do not find any difference [Citation11] or have revealed differences within the Sami population, taking such characteristics as age, gender and geography into consideration. For example, those living in Sami-dominated areas report better mental health than Sami living in marginal Sami area [Citation2,Citation12].

One known reason for mental health problems is bullying [Citation13]. Research shows that people with intellectual disabilities are more exposed to bullying and hate speech than the general population [Citation14,Citation15]. In this article, we examine how the exposure to bullying affects the mental health of people with intellectual disabilities in Sami areas.

There is a lack of knowledge when it comes to Sami people with intellectual disabilities and mental health compared both with Sami people in general and other people with intellectual disabilities in Norway. In other words, current research on living conditions and mental health among Sami people with intellectual disabilities is scarce. National surveys do not include ethnicity issues. They also exclude people with intellectual disabilities. Special living-condition surveys among people with intellectual disabilities have previously been answered by service providers [Citation16]. Also, these surveys have not included questions about ethnicity.

In this article, after presenting the theoretical perspective and the study’s method, we first present results regarding mental health problems among people with intellectual disabilities. Secondly, we present results showing that exposure to bullying is a risk factor for poorer mental health among those with a Sami background. Thirdly, we discuss the findings in relation to existing knowledge and by using an intersectional perspective. Finally, we look at implications for practice and further research.

The perspective of intersectionality

If we are interested in understanding the differences in living conditions between groups, we must look at the influence of belonging to different categories. The concept of intersectionality focuses on how belonging to two or several social categories, for example ethnicity, gender, social class and disabilities coexist and affect our living conditions and identity [Citation17]. The meaning of these categories and how they interact, are not static, but varies from one situation to another. Different categories can, in some situations reinforce each other, and in others weaken each other. Originally, the word intersection meant crossroad [Citation17]. Intersectionality occurs when a person who belong to two or more social categories experiences their crossing one another. The concept wants to capture and explain what is happening when different categories cross each other, in this case to have intellectual disabilities and be a Sami.

The concept of intersectionality can be used and understood in different ways. We can differ between a structure-oriented and a post-structured perspective on intersectionality [Citation18,Citation19]. The post structure perspective is interested in how belonging to different social categories influences our identity [Citation18]. To have intellectual disabilities and be Sami, is something qualitatively different, something more, than being both disabled and Sami. The meaning of the categories you belong to is also contextual [Citation18]. The structure-oriented perspective, on the other hand, illuminates how power relations occur by the mutual impact of categories like gender, social class and ethnicity [Citation19]. This perspective focuses on the situation for marginalised groups in the society, and how belonging to different underprivileged groups reinforces the marginalised position. Considering this perspective, we can look at how being a Sami and having an intellectual disabilities can reinforce the risk of poor mental health and bullying.

This article focuses on the dimensions of disability and ethnicity, though not much research about disabilities and ethnicity has been done. Both belonging to an ethnic minority and having an impairment can cause marginalisation and increased risk for poor mental health. By using an intersectional perspective in the analysis, we want to discuss how the meeting between intellectual disability and a Sami background interact and result in poorer mental health by among, other factors, being more exposed to bullying.

Method

In 2017 the Institute of Social Education at UiT, the Arctic University of Norway, conducted a study of the living conditions among people with intellectual disabilities in the 10 Sami administrative municipalities, including 19 other municipalities with a Sami population in Northern Norway [Citation1]. The study examined whether there are differences in the living conditions of people with intellectual disabilities with and without a Sami background. We also compared their living conditions with the living conditions of people with intellectual disabilities in Norway in general, as well as with the living conditions of the Norwegian and Sami population in general.

Inclusion criteria and sample

The inclusion criteria for participating in the study were age (over 16 years of age) and intellectual disabilities, in addition to living in one of the selected municipalities. Both persons with and without a Sami background were included. It was also important to recruit both genders. A total of 93 persons between 16 and 76 years of age answered the questionnaire. Of those, 29% were in the age group 16–30 years, 44% were in the age group 31–50 years and 27% were in the age group 51–76 years. Men comprised 57% of the respondents, 43% were women. Most of the participants had a mild or moderate intellectual disabilities, while a few had a severe or profound intellectual disabilities. A third of the sample had a Sami background (33%). Those without a Sami background were, on average, a bit younger than those with a Sami background [Citation1].

The questionnaire

We used a structured questionnaire with mainly fixed response categories, including some open answer questions where we could write text. There were in total 76 questions. There were fewer answer alternatives compared to the standard living-conditions surveys. It also included questions regarding ethnicity. The questionnaire was designed in an easy-to-read language. It was written in Norwegian, and then translated into Northern Sami by professional translators.

Operationalising of theoretical concepts

The theoretical term “mental health” must be operationalised in living-condition studies. The term includes everything from serious mental illness to more common mental health problems like mild depression and anxiety. Our operationalisation focuses mostly on the last mentioned, by asking four questions about mental health issues. We asked the respondents if they often struggle with sadness/loneliness/anger/feeling afraid. The answer categories were yes or no. In the survey, we define bullying by asking four questions: “Have you during the last year experienced that someone has said unpleasant things to you/teased you/threatened to hurt you/hurt you”. Here too the answer categories were yes or no.

Recruitment

There is no register in Norway of who has an intellectual disabilities or who is Sami. The recruitment of participants to the study was therefore strategic and snowball characterised. Snowball sampling is often used to find and recruit a hidden population, a group not easily accessible to researchers through other sampling strategies. The sampling was purposive since we wanted to recruit persons with intellectual disabilities in the selected municipalities. To recruit participants, we were dependent on help from gatekeepers in sheltered workshops, day centres, group homes and high schools. We gave both written and oral information to the participants and gatekeepers. The recruiting process was nevertheless challenging. Firstly, we had to get past the gatekeepers, who sometimes thought this group should not or could not participate in studies. Secondly, it is challenging to be accepted in the Sami community. As written by Melbøe et al. [Citation20], to gain access to the Sami population, there were some contextual aspects we especially had to take into consideration. The Sami people´s experience with Norwegian researchers has been bad [Citation21]. The assimilation process in which the Sami people were given limited access to their language and culture, remains a factor that results in a dismissive attitude towards research among the Sami people [Citation22]. We tried to address such recruiting challenges by including Sami people in the research group. This was aided by the fact that several of the researchers have a Sami background. We also presented the study at the Sami Parliament to solicit its collective approval in advance. Melbøe et al. [Citation20] stress that to avoid pitfalls throughout the research process among the Sami, researchers need to have knowledge of Sami culture and history.

The data collection

The data were collected mainly by structured interviews. We met the participants face-to-face in their municipalities, read the questions in the survey aloud and recorded the replies on a PC as the respondents answered. People with intellectual disabilities answered the questions themselves in 88% of the cases. The respondents could ask someone to be with them as support during the interview. This happened in 25% of the cases. The data collection, during which we sat with the respondents, lasted approximately 1 h. We stressed the importance of letting the respondents have enough time to think before they answered. It was also possible to take a coffee break during the interview. Most of the interviews were conducted at sheltered workshops (58%), at home (25%) or other places (18%) such as high schools, day centres or group homes. If the respondents were not able to answer themselves, a parent or a service provider answered instead. They could also fill out the questionnaire at home by using a paper version and return it by post, or use a web-based questionnaire.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were conducted according to three background variables: ethnicity (Sami background or not), age and gender. To determine correlation between variables bivariate analysis was done [Citation23]. SPSS version 23 was the software package used for the statistical analysis. In the report, we present the findings in tables and figures, in percent and absolute number (N). We did not calculate percent where the absolute number was under five. Some of the figures are included in the article. In the analysis, the group of people with a Sami background includes those self-reporting having a Sami background (speaking or understanding a Sami language) and/or having an identity as Sami. This corresponds how Lund et al. [Citation24] and Langås-Larsen et al. [Citation25] identified ethnicity and defined who is Sami in their studies. It is also in line with the proposal for ethical guidelines of Sami health research [Citation26].

Ethical aspects

People with intellectual disabilities have previously been seen as a vulnerable group and have, therefore, been excluded from participating in research concerning themselves [Citation27]. In recent years, this view is changing. Several researchers claim that it is important to let the voices of so-called weak groups be heard [Citation28–Citation31]. At the same time, it is obvious that this group needs special ethical consideration when participating in research. The study was approved by the Norwegian Centre for Research Data (NSD). All participants were informed orally and in written information letters (in Norwegian and Northern Sami) about their right to withdraw from the study without stating a reason and were assured that confidentially would be maintained. We also obtained written informed consent from all participants.

Results

Our study shows that people with intellectual disabilities have, in most areas, both different and poorer living conditions compared to the population in general [Citation1,Citation32]. This concerns housing, education, employment, income, health, social relations, leisure and self-determination. When it comes to mental health, we find that people with intellectual disability and a Sami background have the poorest mental health. Mental health problems among people with intellectual disabilities can have different reasons. We examined some variables in the statistical analysis and found that several corresponded with poor mental health. Those living in a group home reported more often (30%) usually being afraid or worried than those not living in a group home (21%) [Citation1]. Other living-condition variables corresponding to poor mental health were physical health, lack of self-determination, and bullying [Citation1]. However, this article focuses solely on bullying as a condition that increases the risk for poor mental health among people with intellectual disabilities and a Sami background. Below, we first present findings related to mental health. Then we look at bullying as one important risk factor for poor mental health.

Mental health among people with intellectual disabilities and a Sami background

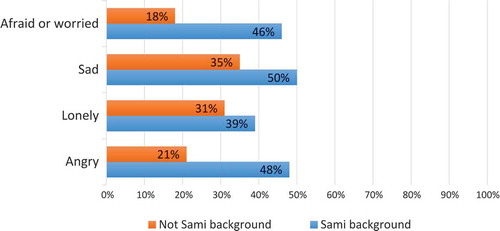

We find that people with intellectual disabilities have poorer mental health compared to the population in general. In the Norwegian population, almost 11% report having mental health problems [Citation32]. illustrates that approximately one-third of the respondents in our study report poor mental health. Thirty-one percent report that they usually feel lonely, 26% are usually afraid or worried, 40% are usually sad and 28% usually feel angry. This corresponds to what previous studies have shown about this group having poorer mental health than the population in general [Citation14].

Figure 1. Percentage that answered “yes” at the question: “Are you usually afraid or worried/sad/lonely/angry?” Total and by gender. N = 83–86

As shows, there are only minor gender differences when it comes to mental health. We still find that women with intellectual disabilities report poorer mental health compared to men with intellectual disabilities (with and without a Sami background), except when it comes to usually being afraid or worried. Which age group is reporting the poorest mental health varies. Not surprisingly, those reporting usually being afraid and worried increases with increasing age [Citation1].

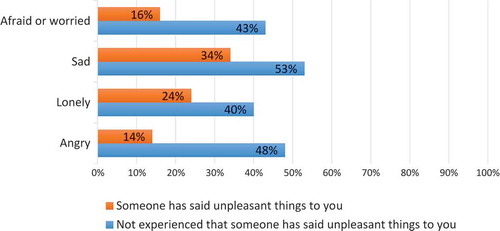

Further, the findings show that people with intellectual disability and a Sami background have poorer mental health than those without a Sami Background. illustrates that while almost half of those with a Sami background (46%) usually are afraid or worried, only 18% of those without Sami background report the same. We also find that while half of those with a Sami background usually feel sad, just 35% of those without a Sami background report the same.

Bullying is a risk factor for poorer mental health

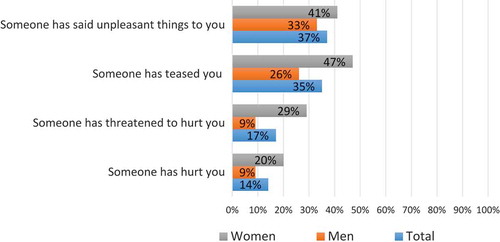

The findings show that people with intellectual disabilities are more exposed to bullying and violence than the general population, and women are more exposed than men [Citation1]. More than one-third of the respondents have experienced that others have said unpleasant things to them, and almost half have been teased (). We find that 17% report that someone has threatened to hurt them, and 14% have been hurt by others. In the national living-condition survey in Norway from 2015, 3.5% of the adult population (16 years +) reported being threatened or hurt in the last year [Citation32]. This is a considerably lower proportion than in our study. Our findings correspond to what Olsen et al. [Citation15] have revealed in their study of hate speech against disabled people. They also pointed to the fact that though this group of people is more exposed to hate speech and bullying, they seldom report this or notify the police [Citation15].

Figure 3. Percentage that answered “yes” at the question: “Have you during the last year experienced that someone has said unpleasant things to you/teased you/threatened to hurt you/hurt you?” Total and by gender. N = 81–83

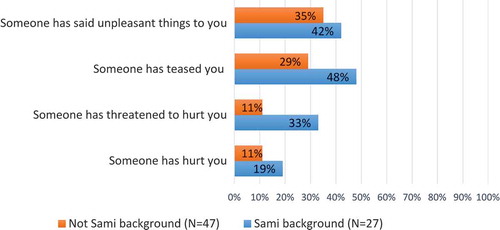

Furthermore, the respondents with intellectual disabilities and a Sami background are even more exposed to bullying and violence than those without a Sami background (). A considerably higher percentage of the respondents with a Sami background have experienced the different types of bullying mentioned in the survey, compared to those without a Sami background.

Figure 4. Percentage that answered “yes” at the question: “Have you during the last year experienced that someone has said unpleasant things to you/teased you/threatened to hurt you/hurt you?” By ethnicity (Sami background or not). N = 47 (Sami background) and N = 27 (not Sami background)

The study shows that 33% with a Sami background have lately been afraid of being beaten when going outside alone close to their homes, while only 17% of those without a Sami background report the same [Citation1].

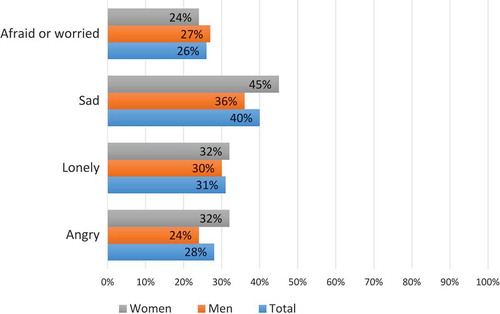

We find a correlation between bullying and poor mental health. People with intellectual disabilities who have been bullied report poorer mental health than those not having experienced bullying. illustrates that 43% of those reporting that someone has said unpleasant things to them are usually afraid or worried. Only 16% of those not having experienced this report similarly. A higher proportion of those who have been bullied also reports usually feeling angry, lonely, and sad than those not have being bullied.

Strengths and limitations

Three main limitations of this study’s methodology can be recognised. Firstly, as mentioned before, there is no register of who is Sami in Norway, nor who has an intellectual disabilities. The number of respondents is also limited, due to challenges in recruiting participants and because we had a strict timetable and limited resources. The study has, therefore, a limitation when it comes to statistical generalisations. Neither can we say anything about the response rate, although we can talk of transferability, by arguing that the findings can be transferred to people in similar situations [Citation33].

Secondly, there is sampling bias, since we chose the sample in a way that made some individuals less likely to be included in the sample than others [Citation23]. We wanted people with intellectual disabilities to answer the questionnaire themselves, and that requires some cognitive capacity to understand our questions and answering. Recruiting participants to the survey was also challenging. It turned out that sheltered workshops were most helpful in recruiting participants from the permanent adopted work measure. Both these circumstances resulted in the fact that we mainly included those with mild or moderate intellectual disabilities.

Thirdly, letting people with reduced cognitive skills answer the questions is methodologically challenging. They often have difficulty understanding concepts and may have difficulty expressing themselves orally and/or in writing. However, the validity of the study is strengthened by the way it was conducted. Researchers sat next to the respondents, read the questions and filled out the form together with them. This gave us the opportunity to explain questions or words that the respondents did not understand. We had prepared an easy-to-read questionnaire in advance. The questionnaire was also pre-tested by two persons with intellectual disabilities.

At the same time, it is a strength that people with intellectual disabilities answered the questions about their living conditions themselves. It also made it possible to add questions about their own assessments. Another strength of the study is the fact that we established a research group in which people with intellectual disabilities and Sami people participated as co-researchers. This is more extensive described in the research report [Citation1]. Involving co-researchers improved the questionnaire when it comes to which questions we asked and in which way.

Discussion

Our study shows that people with intellectual disabilities report poorer mental health than the population in general, and those with a Sami background have even poorer mental health than those without a Sami background. We find that poor mental health, among other factors, corresponds with exposure to bullying. Being Sami puts people with intellectual disabilities in an additionally vulnerable position.

When it comes to mental health, previous research has shown the same as our study; people with intellectual disabilities have considerably poorer mental health compared to the population in general [Citation4,Citation7]. Further, our study shows that people with intellectual disabilities and a Sami background have poorer mental health than those without a Sami background.

Our findings regarding bullying correspond with several studies, which show that both people with intellectual disabilities and Sami people are more exposed to bullying than the population in general [Citation12,Citation15]. Previous research emphasises that Sami people are more exposed to hate speech and violence than the population in general [Citation12,Citation34]. According to Rafoss and Hines [Citation34], Sami people experience bullying 10 times more often than non-Sami Norwegians. The qualitative study of the life situation of Sami people with disabilities, conducted in 2015, also find that bullying and discrimination against Sami people with disabilities are widespread [Citation35]. Hookanen [Citation36] find the same in the Finnish study of Sami people with disabilities. Olsen et al. [Citation15] underline that hate speech against disabled people has been given little attention by research, although they are widely more exposed.

Hansen [Citation12,Citation37] emphasises that ethnic discrimination increases the risk of health problems in the population in northern Norway. According to him, discrimination and bullying can lead to depression and anxiety. Research also shows that Sami people are even more exposed than others to poor mental health because of bullying [Citation10]. At the same time, Hove [Citation7] stresses that people with intellectual disabilities who have been exposed to bullying have a quadrupled risk for developing depression, compared with those not being bullied. Olsen et al. [Citation15] find that the most apparent consequences of offensive speech towards disabled people were often feeling sad and depressed. This corresponds with our findings (). People with intellectual disabilities seems to be additionally vulnerable due to psychosocial strain than the rest of the population. Hove et al. [Citation13] argue that the experience of a lack of involvement and control over one’s situation, together with a premorbid vulnerability, can result in the development of depression when they are bullied.

People with intellectual disabilities are bullied in places where they should feel safe, such as at home, in school and sheltered workshops [Citation1,Citation15,Citation35,Citation38]. Living in group homes can, for instance, increase the risk of being bullied. A large proportion live in a group home together with other people in need of help, people with different kinds and degrees of intellectual disabilities, but also people with mental illness [Citation6]. They have their own rooms but often share some space with the other residents, for example, the living room or kitchen. Today, most live in large group homes with five residents or more [Citation6]. The respondents living in a group home are also less satisfied with their residence than others. While only 70% of those living in a group home like to live where they live, 87% of those not living in a group home report the same [Citation1]. Our study shows that people living in a group home feel more insecure [Citation1].

People with reduced cognitive ability in Norway rarely have the opportunity to choose where to live. Hove et al. [Citation13] stress that user involvement can counteract the most serious consequences of bullying. People with intellectual disabilities have less self-determination than the population in general [Citation16]. Those with a Sami background feel even more lack of self-determination than those without a Sami background, when it comes to important decisions like where to live [Citation1]. While 52% of people with intellectual disabilities without a Sami background report that they decide most when it comes to their residential, only 44% of those with a Sami background do the same [Citation1]. We find that while 78% of the respondents without a Sami background report that they prefer to live where they live today, if they had the opportunity to choose, only 67% of those with a Sami background report the same [Citation1]. In other words, one-third of those with a Sami background in our study want to live in another place. The study reveals that people with intellectual disabilities reporting satisfaction with where they live report better mental health than those reporting that they want to live another place. We find that while 23% of the respondents who have an influence on where they live report that they usually feel lonely, 40% of those who lack self-determination in this area report feeling lonely [Citation1]. The respondents wanting to live in another place reported poorer mental health at all the four questions we asked. This means the opportunity of self-determination regarding where to live influences on the mental health of people with intellectual disabilities, and especially for those having a Sami background.

An intersectional perspective considers that discrimination may occur on many bases [Citation36]. Sami people with disabilities are bullied both because of being a member of an indigenous group and their disabilities. By using an intersectional perspective, belonging to different categories will have different meanings in different contexts. The meaning of the categories influences each other in different ways. Both disability and ethnicity are social categories that increase the risk for poorer mental health among people with intellectual disabilities in Sami areas in Norway. While answering the questionnaire in our study, the respondents told different stories of bullying. In some situations, they have been bullied because of their disability. In other situations, they have been bullied because of their Sami background, by hearing comments like “stupid as a Sami” or called “Lapp bastard” [Citation35]. In other situations, Sami people with intellectual disabilities have been bullied because of both their disabilities and their ethnicity. The reality is thus complex, just as intersectional theory highlights. It will vary how and to what extent the Sami background and the disability matter when it comes to mental health and bullying. In one context, it will matter, in others it will not. Hokkanen ([Citation36],p.20) also emphasises in a study of Finnish Sami with disabilities that “Discrimination proves to be an intersectional and contextual phenomenon”.

Implications for practice and further research

Further research is needed to examine the reasons for poorer mental health and bullying among people with intellectual disabilities, with a special focus on those with a Sami background. Also, the correspondence between poor mental health and bullying needs to be explored. Nevertheless, our findings have implications for practice when it comes to the mental health among this group, both in general and especially regarding those with a Sami background. As stressed by intersectional theory – the meaning of ethnicity as an important category, in addition to the disability, must be illuminated. One important issue is how the categories interact with each other and cause increased vulnerability.

The findings must also be seen in relation to the Convention Concerning Indigenous and Tribal Peoples in Independent Countries (ILO 169), which Norway ratified in 1990, and the Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP). Article 22 of the UNDRIP requires states´ parties to pay particular attention to the rights of indigenous persons with disabilities. Also, the UN Convention on the Rights of the Persons with Disabilities (CRPD), which Norway ratified in 2013, is important. It underlines that discrimination based on disabilities is prohibited. Considering these conventions, our findings must be taken seriously.

When it comes to mental health, we can first ask to what extent does the health system notice whether people with intellectual disability have mental health problems? This group has a disadvantage ̶ they cannot, due to their cognitive impairment, express themselves verbally as well as others. Also, people with intellectual disabilities and a Sami background can have, due to their culture, problems with talking about their mental health problems. Research shows that Sami people are less likely to seek help for their mental health problems than ethnic Norwegians [Citation12,Citation36]. Bongo [Citation39] finds that the Sami do not speak about their mental health problems outside the family, because the norm about not showing weakness is strong in the Sami culture. Bals et al. [Citation40] also find that it is taboo in the Sami culture to talk about mental health problems. You shall not bother others with your problems. This will necessarily have implications for the relationship with the health services. Second, what kind of help do people with intellectual disability receive when they have mental health problems? Further, do the healthcare personnel possess cultural competence? Previous research has shown that Sami patients are less satisfied with mental health services than Norwegian patients [42]. Bongo [Citation39] stresses that health service providers must have knowledge of the Sami way of understanding mental illness. It is, therefore, necessary that health personnel have knowledge of Sami culture, in addition to knowledge about mental health problems among people with intellectual disabilities. Another issue is the prevention of poor mental health. Knowledge about risk factors may help us see what we must focus on.

Hate speech and violence against this group must be taken more seriously, and with a special focus on those with a Sami background. This means that bullying must be focused on in different arenas were people with intellectual disabilities live their everyday life. As previous research has stressed [Citation15], it is not enough to try to change the attitudes. Hate speech, bullying and violence against these people must be reported to the juridical system as well and responded to by those agencies.

Conflict of interest

The author declares no conflict of interest. The study was carried out on behalf of the Norwegian Directorate for Children, Youth, and Family Affairs and the Nordic Centre for Welfare and Social Issues.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank the participants and the co-researchers for their valuable contributions to the study.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Gjertsen H, Melbøe L, Fedreheim GE, et al. Kartlegging av levekårene til personer med utviklingshemming i samiske områder. Tromsø (Norway): UiT, the Arctic University of Norway; 2017.

- Sjölander P. What is known about the health and living conditions of the indigenous people of northern Scandinavia, the Sami? Glob Health Action. 2011;4(1):8457.

- Blix BH, Hamran T. «They take care of theire own”: healthcare professionals´constructions of Sami persons with dementia and their families´ reluctance to seek and accept help through attributes to multiple contexts. Int J Circumpolar Health. 2017;76(1):1328962.

- The Norwegian Directorate for Children, Youth and Family Affairs. Slik har jeg det i dag. Rapport om levekår for mennesker med utviklingshemming. Oslo (Norway): Bufdir; 2013.

- Skog Hansen IL, Grødem AS. Samlokaliserte boliger og store bofellesskap. Perspektiver og erfaringer fra kommunene. Oslo (Norway): Fafo; 2012.

- Kittelsaa A, Tøssebro J. Store bofellesskap for personer med utviklingshemming: noen konsekvenser. Trondheim (Norway): NTNU samfunnsforskning; 2011.

- Hove O Mental health disorders in adults with intellectual disabilities – Methods of assessment and prevalence and mental health disorders and problem behaviour [PhD-thesis]. Bergen (Norway): UiB; 2009.

- White paper nr. 45 (2012-2013). Frihet og likeverd – om mennesker med utviklingshemming. . Oslo (Norway): The Norwegian Directorate for Children, Youth, and Family Affairs; 2012

- Bakken T. Utviklingshemming og hverdagsvansker. Faktorer som påvirker psykisk helse. Oslo: Gyldendal Akademiske; 2015.

- Hansen KL, Sorlie T. Ethnic discrimination and psychological distress: a study of Sami and non-Sami populations in Norway. Transcult Psychiatry. 2012;49(1):26–10.

- Kvernmo S. Mental health of Sami youth. Int J Circumpolar Health. 2004;63(3):221–234.

- Hansen KL. Indigenous health and wellbeing. Circumpolar health supplements. Vol. 7. Canada: International Union of Circumpolar Health; 2010. (ISSN 1797-2361)

- Hove O, Lier H, Havik O. Mobbing gir psykiske vansker hos personer med utviklingshemming. Trondheim (Norway): NAKU; 2009.

- Söderström S, Tøssebro J. Innfridde mål eller brutte visjoner?: noen hovedlinjer i utviklingen av levekår og tjenester for utviklingshemmede. Trondheim (Norway): NTNU Samfunnsforskning; 2011.

- Olsen T, Vedeler JS, Eriksen J, et al. Hatytringer. Resultater fra en studie av funksjonshemmedes erfaringer. Bodø (Norway): Nordland Reasearch Institute nr. 6; 2016.

- Kittelsaa A, Wiik S, Tøssebro J. Levekår for personer med nedsatt funksjonsevne: fellestrekk og variasjon. Trondheim: NTNU Samfunnsforskning; 2015.

- Söder M, Grönvik L. Bara funktionshindrad? Funktionshinder och intersektionalitet. Malmö (Sweden): Gleerups forlag;2008 9–24. Chapter 1, Intersektionalitet och funktionshinder.

- Lykke N. Nya perspetiv på interseksjonalitet. Problem och möjligeter. Kvinnovetenskapligt tidsskrift. 2005;2–3: 7–17. doi:urn:nbn:se:liu:diva-32132.

- De Los Reyes P, Mulinaris D. Intersektionalitet. Kritiska reflektioner över ojämlikhetens landskap. Lund (Sweden): Liber; 2005.

- Melbøe L, Hansen KL, Johansen BE, et al. Ethical and methodological issues in research with Sami experiencing disability. Int J Circumpolar Health. 2016;75:31656.

- Skorgen T. Rasenes oppfinnelse: rasetenkningens historie. Oslo (Norway): Spartacus; 2002.

- Bull T. Kunnskapspolitikk, forskningsetikk og det samiske samfunnet. Oslo (Norway): Forskningsetiske komiteer; 2002.

- Bohrnstedt GW, Knoke D. Statistics for social data analysis. Michigan: F.E. Peacock Publishers; 1988.

- Lund E, Brustad M, Høgmo A. The Sami – living conditions and health. Int J Circumpolar Health. 2008;67(1):6–8.

- Langås-Larsen A, Salamonsen A, Kristoffersen AE, et al. «We own the illness»: a qualitative study of networks in two communities with mixed ethnicity in Northern Norway. Int J Circumpolar Health. 2018;77(1):1438572.

- Sametinget. Forslag til etiske retningslinjer for samisk helseforskning og forskning på samisk humant biologisk materiale. Karasjok (Norway): Sametinget; 2018.

- Mallander O. De hjälper oss till rätta: normaliseringsarbete, självbestämmande och människor med psykisk utvecklingsstörning. Lund (Sweden): Lunds universitet; 1999.

- Sundet M. Noen metodiske dilemmaer. Om bruk av deltakende observasjon i studier av mennesker med utviklingshemming. In: Gjærum RG, editor. Usedvanlig kvalitativ forskning - metodologiske utfordringer knyttet til forskningsdeltakere med utviklingshemming. Oslo (Norway): Universitetsforlaget; 2010. p. 123–137.

- Aldridge J. Picture this: the use of participatory photographic research methods with people with learning disabilities. Disability Soc. 2007;22(1):1–17.

- Chappell AL. Emergence of participatory methodology in learning difficulty research: understanding the context. Br J Learn Disabil. 2000;28(1):38–43.

- Nind M, Vinha H. Practical considerations in doing research inclusively and doing it well: lessons for inclusive researchers. Southampton (GB): University of Southampton; 2013.

- Statistisk sentralbyrå. Levekårsundersøkelsen SILC. Oslo (Norway): SSB; 2015.

- Thagaard T. Systematikk og innlevelse. Oslo (Norway): Fagbokforlaget; 1998.

- Rafoss K, Hines K. Bruk av fritidsarenaer og deltakelse i fritidsaktiviteter blant samisk- og norsktalende ungdom i Finnmark. Samiske tall forteller. 2016;9:17–40.

- Melbøe L, Johansen BE, Fedreheim GE, et al. Situasjonen til samer med funksjonsnedsettelser. Stockholm (Sweden): Nordic Welfare Centre; 2016.

- Hokkanen L. Experiences of inclusion and welfare services among Finnish Sami with disabilities. Stockholm (Sweden): Nordic Welfare Centre; 2017.

- Hansen KL, Melhus M, Lund E. Ethnicity, self-reported health, discrimination and socio-economic status: a study of Sami and non-Sami Norwegian populations. Int J Circumpolar Health. 2010;69(2):111–128.

- Grøvdal Y. Mellom frihet og beskyttelse? Vold og seksuelle overgrep mot mennesker med psykisk utviklingshemming. En kunnskapsoversikt. Oslo (Norway): Nasjonalt kunnskapssenter om vold og traumatisk stress; 2013.

- Bongo B Samer snakker ikke om helse og sykdom – Samisk forståelseshorisont og kommunikasjon om helse og sykdom. En kvalitativ undersøkelse i samisk kultur [PhD-thesis]. Tromsø (Norway): UiT; 2012.

- Bals M, Turi AL, Skre I, et al. Internalization symptoms, perceived discrimination, and ethnic identity in indigenous Sami and non-Sami youth in Arctic Norway. Ethn Health. 2010;15(2):165–179.

- Sørlie T, Nergård JI. Treatment Satisfaction and Recovery in Saami and Norwegian patients following psychiatric hospital treatment: a comparative study. Transcult Psychiatry. 2005;42(2):295–316.