ABSTRACT

Background: Among Indigenous people in Canada the incidence of HIV is 3.5 times higher than other ethnicities. In Manitoba First Nations, Metis and Inuit people are disproportionately represented (40%) among people who are new to HIV care. Northlands Denesuline First Nation (NDFN) identified the need to revisit their level of knowledge and preparedness for responding to the increasing rates of HIV. NDFN piloted a community readiness assessment (CRA) tool to assess its appropriateness for use in northern Manitoba.

Methods: A First Nation and non-First Nation research team trained to administer the CRA tool at NDFN in Manitoba. Five informants were interviewed using the CRA tool and the responses were scored, analysed and reviewed at community workshops and with stakeholders to develop a 1-year action plan.

Results: CRA training was best conducted in the community. Using the readiness score of 2.4 along with feedback from two workshops, community members, the research team and stakeholders, we identified priorities for adult education and youth involvement in programmes and planning.

Conclusions: In response to the increasing incidence of HIV, a northern First Nation community successfully modified and implemented a CRA tool to develop an action plan for culturally appropriate interventions and programmes.

Introduction

HIV incidence among Indigenous people is 3.5 times higher than among other ethnic groups in Canada and between 2008 and 2011, there was a 17.3% increase (5,440–6,380) in the number of Indigenous people living with HIV/AIDS [Citation1]. The Canadian province of Manitoba has one of the largest populations of Indigenous (First Nations, Inuit and Metis) peoples in Canada, second only to Saskatchewan (SK) [Citation2]. In Manitoba, Indigenous peoples are disproportionately represented (40%) among people who are new to care [Citation3]. First Nation individuals present with much more advanced HIV disease: they have higher viral loads [Citation4], and in 2010, 35% of all new First Nations cases presented late to care with CD4 counts<200 cells/mm3 [Citation4,Citation5]. The majority of First Nations individuals presenting with advanced HIV occurs live in the northern regions of the province [Citation6]. Individuals at this late stage of HIV have an increased risk of opportunistic infection, experience delays in starting antiretroviral therapy, worse outcomes and decreased life expectancy [Citation7,Citation8].

Manitoba First NationFootnote1 communities are aware that the rates of HIV are rising among First Nations through media coverage and from personal experience through the loss of a community relative to AIDS (Samuel, personal communication) [Citation9]. However, implementing HIV/AIDS testing and care programmes for First Nation people in Manitoba’s northern communities is a challenge for a number of reasons, which include but are not limited to the following: (a) the remote location of many communities, (b) lack of access to health services and supports [Citation10], (c) limited understanding of the variety of barriers and enablers to implementation of current best practice of HIV/AIDS testing and care, (d) lack of integration of First Nation cultural ways of knowing and healing practices with western medicine practices, (e) our current lack of multi-sectoral partnerships to coordinate strategies to understand and effectively address HIV/AIDS among First Nations populations, (f) stigma associated with HIV/AIDS and concerns about confidentiality, (g) complex rules regarding federal–provincial responsibility for Indigenous health care.

Northlands Denesuline First Nation (NDFN) is a small Dene community in northern Manitoba that has been engaged in a longstanding research partnership with the University of Manitoba [Citation11–Citation15]. NDFN is located in northern Manitoba and is accessible only by air year-round and by winter road for a few months in the winter. The population is 728, of whom approximately 40% are under the age of 30 [Citation16,Citation17]. The Dene are part of the larger Athabaskan language family which also includes the Navajo in the southern USA [Citation16,Citation18,Citation19]. People living on the Reserve travel to the northern Manitoba city of Thompson and to a lesser extent to Winnipeg for medical services, work, visiting and shopping and also into the nearby province of Saskatchewan to visit friends and family and for employment opportunities.

At a research meeting in 2016, community representatives identified a gap in knowledge regarding sexually transmitted blood-borne infections (STBBIs). In 1994, the community hosted a forum on HIV/AIDS to provide information about the disease. Since that time educational programmes had been limited except as part of the junior and senior high school health curriculum [Citation20]. The advances in HIV/AIDS testing as a standalone test or in combination with other STBBI tests such as syphilis and HCV, the complexity of HIV treatment in terms of both the medications and navigating care in a remote location and the continuing issues of stigma were all discussed at the research meeting.

Community readiness assessment (CRA)

Subsequent to the 2016 community meeting, research partners considered options for evaluating community preparedness for HIV testing and treatment programmes. The “community readiness model” was developed by the Tri-Ethnic Centre for Prevention Research at Colorado State University and is based on theoretical concepts of psychological readiness and community-based diffusion of innovations [Citation21–Citation24]. The model was originally created for use with alcohol and drug abuse prevention programmes and has been used or proposed for use to respond to alcohol abuse, child abuse, reducing head injuries on farms, for developing plans for highways and bridges, HIV/AIDS, childhood obesity cultural competency, animal control issues, suicide and even responding to change as a result of environmental and weather conditions [Citation22,Citation25–Citation27]. The assessment tool is based on a model for community engagement that integrates the community’s culture, resources and level of readiness to create change. The relative success or failure of prevention and intervention programmes may not be a matter of the quality of planning or evidence-base of the programmes themselves, but an issue of those interventions being appropriately matched to a community’s level of readiness. Evidence-based interventions may fail if a community is not interested or invested in supporting them or if they are not culturally sensitive or appropriate. Prevention and/or education programmes will only be successful if a community is prepared and ready to receive information and if it is provided in a way that is culturally appropriate. With Colorado State University’s permission, CAAN adapted and piloted the model for use by Indigenous individuals and groups in Canada to assess readiness to address HIV/AIDS risk reduction [Citation22,Citation23,,Citation28]. CAAN developed a manual and workbook to guide and teach trainers how to assess a community’s readiness for creating change [Citation29].

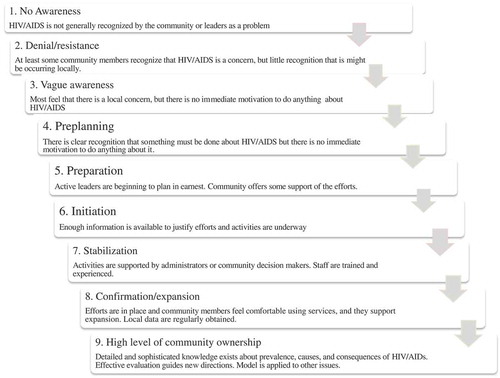

The CRA is a method to train and engage community members to reflect on a particular issue through a process of asking key informants (4–6 people) 22 questions, summarising and evaluating the results and then developing an action plan to create change [Citation28]. The interview questions cover six themes (dimensions) (see ) that assess the respondent’s knowledge about HIV and the resources, programmes and community-based initiatives. Interview responses are scored using a Likert-type scale from 1 to 10 where “1” is no knowledge or awareness of the issue through to a “10” where the respondent can identify a high level of community ownership and action with regard to the issue (). Notes were also kept to record the qualitative responses to the interview questions.

Table 1. Six themes (dimensions) addressed in the CRA and the Likert-type scale for responses

As a result of our existing research partnership and in collaboration with the Manitoba HIV Collective Impact NetworkFootnote2 , it was decided that NDFN would pilot the use and administration of CAAN’s CRA Tool to assess its appropriateness in a northern remote First Nation community. Although CAAN piloted CRAs with Aboriginal organisations and First Nation communities, there is no literature that explores its utility or documents the processes [Citation28]. The objectives were therefore to (1) pilot the process for understanding the level of community readiness around HIV issues and preparedness in a northern Manitoba First Nation community; (2) involve partnership building in the context of CRA through the training and assessment processes and develop an action plan to move forward to support risk reduction for HIV in a way that is appropriate for their community; and (3) provide evidence as to whether or not the CRA tool is best practice as a first step for identifying and planning culturally appropriate programmes and interventions.

Ethics

The project was community-led and participatory in nature and followed the principals of ownership, control, access and possession (OCAP) [Citation30]. Approvals for this project were obtained from the Chief and Councillors. The University of Manitoba Health Ethics Review Board reviewed the project plan. The Board considered that this project did not require their approval since no participants were being enrolled nor was any personal health information collected.

Piloting the CRA tool

Identifying the issue

High rates of HIV have been associated with determinants of health that increase vulnerability to infection including poverty, unstable housing/homelessness, mental health, addictions, racism and the multi-generational effects of colonialism and residential schools [Citation31–Citation37]. In the broader context, vulnerability to HIV among First Nations is rooted in the social determinants that are linked to the unjust circumstances resulting from European colonisation [Citation38]. While anecdotal evidence indicates that Manitoba and Saskatchewan First Nations people interact socially particularly between border First Nation communities [Citation39], in Manitoba, the two most reported risk of exposures for HIV in 2015 were men who have sex with men (MSM 33%) and heterosexual sex (25%) [Citation40].

Training to administer the CRA

Training to conduct the CRA occurred at two sessions over 3 months. After each training session, the CRA team completed a questionnaire that collected data about the learning experience and the perceived utility of the training for the participants.

Three NDFN team members, chosen by the community’s Health Team Director, and two Winnipeg-based team members, chosen by the research team, attended the 2.5-day training session in The Pas, MB. Representatives from CAAN delivered CRA training as well as training about harm reduction strategies, supply distribution, opiate overdose response and information on fentanyl and other opiates.

Two First Nation team members completed an evaluation survey of the training session. The participants did not feel that the training had successfully equipped them with the appropriate knowledge about HIV/AIDS or the tools they needed to conduct the CRA. The two Winnipeg-based team members reported that the first half-day of the training was “derailed” by an extended question and answer period about HIV/HCV at the beginning of the training and used up valuable training time. It was also noted that hard copies of the “Community Readiness Manual” [Citation29] were poorly reproduced and difficult to follow during the training session and as reference material. The training was designed to “train the trainer” which made the presentation of the material and the learning complicated for individuals who were new to CRA.

A second training event was arranged and held at the Health Office at NDFN over 2.5 days. The two Winnipeg-based research team members who had completed the CRA training travelled to Lac Brochet, MB and delivered an adapted CRA training to five members of the local NDFN health team. At the end of the two session, five people (N = 4 females, N = 1 male) were fully trained in the CAAN HIV CRA tool. They all agreed that the training helped them understand the issues surrounding HIV/AIDS and equipped them with the tools needed to conduct the CRA. Training in the community was preferred because that it could include more people from the community, it could specifically target their needs, it allowed more time for discussion between all of the participants.

We introduced the concept of “community readiness” asking the research team to recall previous community experiences of identifying problems and enacting solutions. Team members identified how the community had previously dealt with garbage control, resulting in the banning of plastic bags. Recalling how the community identified that issue and was able to act, provided an example for the team of past successes and a concrete model for addressing HIV/AIDS using CAAN’s CRA tool.

Other modifications to the training included using tools that allowed for more interaction and discussion between the team members and more “hands on” practice. There was an intentional decision to not use power point slides in order to create more space for roundtable discussions and participation. Flip charts were used to illustrate more complex activities and also capture key discussion points from the participants. Instead of older and difficult to read copies of CAAN’s “Community Readiness Manual”, participants were provided with up-to-date copies of “Assessing Community Readiness and Implementing Risk Reduction Strategies”. The team members also practiced delivering the interview questions and recording the responses by conducting “mock interviews”, so that they were confident and familiar with the data collection methods.

Interviews and scoring the responses

It was determined through discussion and through the guidance of the CAAN CRA guidelines that five NDFN CRA team members would interview one member from each of the following community groups – youth, Elder, teacher, adult and a parent. Other potential people to interview that were discussed were the local nurse, priest, store manager, and an elected and non-elected person in leadership. These people were not interviewed because they were either not available or it was decided the chosen groups were representative of the community. The 22 questions in the CRA manual were asked at each interview in either English or Dene according to the wishes of the person interviewed.

The responses to the questions were collected qualitatively and quantitatively. For example, the first question was “In your community, how much of a concern is providing services that reduce risk and risky behaviour associated to HIV and HCV infection?” [Citation28]. The quantitative answers were arrived at by comparing the response to a Likert-type scale “anchored scoring sheet guide” found in the CRA manual [Citation28]. The respondent was asked to provide an answer for this question “using a scale from 1 to 10 that represents how aware a people in the community are of these efforts (1 = “being no awareness” and 10 = “being very aware”)? Please explain?” The interviewer kept hand written notes of the score and recorded the qualitative responses.

In accordance with the CAAN CRA tool, the results of the overall assessment are obtained by (1) averaging the numeric responses for the questions in each of the six themes, (2) averaging the score for each interview and (3) averaging that score for the five interviews. The interviewers experienced some uncertainty about some of the questions and scoring the responses. At the request of the NDFN team, therefore, three Winnipeg-based researchers who were not involved in the interviews helped to review the qualitative responses and individual quantitative scores and with the overall scoring. The scoring required some interpretation of the answers to the 22 questions in order to arrive at a numerical value. For example, the question about the leadership which asked “How are the ‘leaders’ involved in efforts regarding providing services that reduce risk and risky behaviours? Please explain” received answers of “I don’t know” or “None”. The team had to interpret these answers against the evaluative scores that did not match these answers. A score of 1 meant that “Leadership has no recognition of the issue” or a higher score of 4 is defined as “Leader(s) is/are trying to get something started” neither of which matched the response. Through discussions about what the respondent might have meant by their answers helped the group arrive at a numerical score.

The overall CRA score was 2.4, which indicated that there might be “denial/resistance” of the issue or that there was little recognition that it might be a local issue (see and ). Four of the six dimensions scored within this “denial/resistance” level, but the community had a “vague awareness” of Dimensions D and F. We further analysed the results of the interviews by comparing the scores of each of the respondents and we found that the adult and youth scored the lowest (1.0 and 1.5, respectively) and the Elder and teacher scored the highest (3.0 and 3.8, respectively). These scores represent only single interviews in each demographic group, but they were useful for demonstrating that information about HIV was not uniform in the community.

Table 2. Scores for dimensions A to F for each of the interviews

Developing an action plan

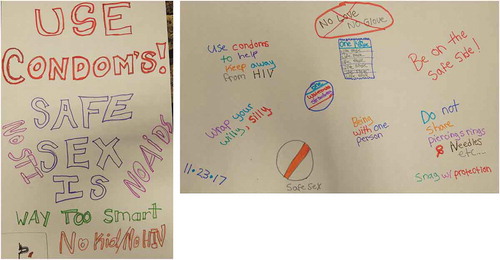

In accordance with the CAAN manual, our team held workshops in both NDFN’s community and in Winnipeg to facilitate the development of an action plan and to enhance knowledge-sharing between the study partners. Our action plan was, therefore, informed by the results of the CRA and two workshops. At NDFN, a feast and workshop were held to present and discuss the results of the assessment to the broader community. Drs. McLeod. MacDonald and Larcombe and Ms. Samuel organised and engaged 46 adults in a discussion about NDFN’s involvement in HIV prevention, testing and supporting individuals living with HIV. We also conducted tutorials at the local school with the junior and senior high school students. The students were engaged in discussions about “HIV facts and myths” and created posters for the school in preparation for National AIDS Awareness Day.

The results indicated that adults were the least well informed about HIV compared to the youth, teacher and the Elder that were interviewed. This was reinforced by the questions about HIV that were raised at the workshop attended by adults. Question such as “what are the symptoms of HIV?”, “how can you prepare yourself to prevent HIV transmission?”, “how long will someone live with HIV?”, “can old ladies get HIV?”, “what’s the difference between HIV and AIDS?” among others suggested to those at the workshop that there is a need for knowledge-sharing sessions for adults. The messages that the youth (junior and senior high school students) used in the posters they created indicated to the group that they understood the important role that condoms have for HIV and pregnancy prevention (). The lack of access to condoms outside of the nursing station was identified as a community-based issue.

The workshop in Winnipeg brought together researchers, Band Council members, the health director, HIV/AIDS clinicians and health care workers from provincial and federal government, hospital and health centres, First Nations NGOs and health care workers from northern Manitoba who are based in Thompson that provide HIV/AIDS services. The purpose of the workshop was to develop an HIV/AIDS action plan based on the strengths and challenges of the participating First Nation community and the participating organisations and to facilitate reciprocal and two-eyed seeing learning. As a group, we analysed the results of the interviews and considered the discussion at the community workshops to develop and action plan for NDFN.

At the 1-day workshop, the participants reviewed the project methods and results. Participants discussed available organisational resources and opportunities that might be relevant for developing an action plan. Participants broke into small groups to brainstorm regarding the strengths, opportunities, weaknesses and barriers for each dimension. For example, for Dimension A (existing community efforts), participants identified that based on the posters the youth created there was strong knowledge about condoms. Opportunities for reinforcing this might be to have condoms available at multiple places in the community apart from the nursing station which is currently the sole source. A weakness for increasing the availability of condoms was that Elders might not want them to be visible in the community and no one was sure how many condoms were being used in the community. The fact that condoms were not available at the local store and that the nursing station is closed in the evenings was identified as a barrier. This type of analysis was performed for each dimension.

Six items were identified as action plan priorities: (1) educational workshops for adults about HIV/AIDS and plan a conference for the community, (2) building youth champions for HIV/AIDS to address local issues (i.e. access to condoms), (3) address overcrowded housing as an issue for sexual health, (4) introduce and build awareness/understanding of the HIV testing options in the community including novel approaches that are culturally appropriate, (5) identify more resources of HIV/AIDS education and have them translated into First Nation languages, (6) investigate the pathway that northern First Nations individual have to navigate through for HIV health care and treatment. In the space of the workshop action, plans with timelines and dedicated personnel were developed for the bolded priorities.

Summary and conclusions

The rates of HIV/AIDS are increasing among First Nations in Canada. The CAAN CRA is a tool to help a community assess their current state of preparedness, knowledge and extent of the resources that they have for taking action against these increased rates. The CRA tool was designed to bring a community together, build cooperation and increase capacity for prevention and intervention for change around any identified community-based issue [Citation22]. NDFN and representatives from academia, clinical practice, non-government and government organisations piloted the CRA tool in the remote northern community at Lac Brochet, MB. CAAN modified and adapted the tool in 2009 specifically for HIV prevention for use by First Nation communities [Citation29] and then refined the manual in 2012 [Citation28]. This pilot project used the CRA tool and we revised some aspects of the training, scoring and action planning protocols during the implementation process

Training to use the tool was best accomplished in the First Nation community rather than having to travel to a training site. More people could attend the training and the discussions could focus on the specific community. The training manuals were difficult to follow and not focused on training individuals to administer the CRA tool. Instead, the 2009 and 2012 manuals have multiple levels of training about the tool itself and about teaching others to use the tool. For individuals who have not yet used the tool and are unfamiliar with method, it was not appropriate to attempt to use this “train the trainer approach”. A training manual should be created that focuses exclusively on training individuals to administer the CRA tool and uses the language used for the interview questions and Likert-type scale responses should be simplified and focus explicitly on HIV/AIDS.

Scoring and developing an action plan were accomplished through a collaborative approach drawing from the people and resources of the research team and their organisations. An important limitation for learning and administering the CRA tool in a remote northern First Nation community is that these communities are inadequately funded and resourced for using the CRA tool. The support of individuals from academia, government and non-government organisations for all aspects of training and administering the CRA tool was a factor that facilitated completing the work. These organisations were instrumental in identifying how they can support the community with specific interventions that are culturally appropriate.

The success and utility of assessing the community using this tool will not be known until additional assessments are conducted in the future to know if the assessment score changes – the ultimate proof of change using this tool. However, the CRA tool proved to be useful for drawing attention to a specific issue and focusing efforts to develop an action plan that was appropriate for the needs of a northern First Nation. Going forward, the community-led First Nation health team has a solid base of training and the practice of implementing the assessment tool, scoring and developing an action plan and they can use this experience to re-evaluate the extent of change in their community in the future. To make the process of administering the tool more user-friendly, a revised manual should provide step-by-step instructions for conducting a CRA after a 1-day training and practice session. This would minimise the amount of resources needed for using the tool and increase the likelihood that a community will re-assess their readiness for change in the future.

Strategies for halting the increasing rates of HIV and other STBBIs among Indigenous people in Canada need the leadership and support of First Nations. Using a modified version of CAAN’s HIV CRA tool, a northern First Nation community planed and implemented culturally appropriate HIV programming. Taking the steps necessary for underserved First Nation communities to lead the discussion regarding HIV testing, treatment and caring for people living with HIV will result in better informed and appropriate strategies for addressing this health crisis.

Acknowledgments

Funding was received from REACH 2.0 and The James Blair Farley Memorial Fund for this project. The research partnership between Dene First Nations in Manitoba and the University of Manitoba made this work possible.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 In this paper, the term Indigenous refers to those who identify as First Nations, Metis and/or Inuit.

2 The Manitoba HIV Collective Impact Network is a group of innovative people working to change the landscape of HIV in Manitoba.

References

- Health Canada. Protecting Canadians from Illness HIV/AIDS Epi updates chapter 8: HIV/AIDS among Aboriginal People in Canada. Ottawa; 2014. Available from www.phac-aspc.gc.ca

- Statistics Canada. Aboriginal Peoples in Canada: First Nations people, Métis and Inuit. Ottawa; 2016. Available from https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/hiv-aids/publications/epi-updates/chapter-8-hiv-aids-among-aboriginal-people-canada.html

- Manitoba HIV Program. 2017 Manitoba HIV program update. Winnipeg; 2018. Available from https://ninecircles.ca/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/2017-HIV-Program-Report-Final.-2.0.pdf

- Becker ML, Thompson LH, Pindera C, et al. Feasibility and success of HIV point-of-care testing in an emergency department in an urban Canadian setting. Can J Infect Dis Med Microbiol. 2013 Spring;24(1):27–9. PubMed PMID: 24421789; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC3630025.

- Manitoba HIV Program. Manitoba HIV program report 2010. Winnipeg: Nine Circles Community Health Centre 2011.

- Plitt SS, Mihalicz D, Singh AE, et al. Time to testing and accessing care among a population of newly diagnosed patients with HIV with a high proportion of Canadian Aboriginals, 1998–2003. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2009 Feb;23(2):93–99. 10.1089/apc.2007.0238. PubMed PMID: 19133748.

- Sterne JA, May M, de Wolf F, et al. Timing of initiation of antiretroviral therapy in AIDS-free HIV-1-infected patients: a collaborative analysis of 18 HIV cohort studies. Lancet 2009 Apr 18;373(9672):1352–1363. PubMed PMID: 19361855; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC2670965.

- Kitahata MM, Gange SJ, Abraham AG, et al. Effect of early versus deferred antiretroviral therapy for HIV on survival. N Engl J Med. 2009 Apr 30;360(18):1815–1826. PubMed PMID: 19339714; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC2854555.

- Soloducha A. Saskatchewan’s HIV rate highest in Canada, up 800% in 1 region. CBC News, 2017 [ cited https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/saskatchewan/saskatchewan-hiv-rate-highest-canada-1.4351057

- Allec R. First Nations Health and Wellness in Manitoba. Winnipeg; 2005.

- Larcombe LA, Shafer LA, Nickerson PW, et al. HLA-A, B, DRB1, DQA1, DQB1 alleles and haplotype frequencies in Dene and Cree cohorts in Manitoba, Canada. Hum Immunol. 2017;78(5):401–411.

- Larcombe L, Nickerson P, Singer M, et al. Housing conditions in two Canadian First Nations communities. Int J Circumpolar Health. 2011 Apr;70(2):141–153. PubMed PMID: 21524357; eng.

- Larcombe L, Mookherjee N, Slater J, et al. Vitamin D in a northern Canadian First Nation population: dietary intake, serum concentrations and functional gene polymorphisms [Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t]. PloS One. 2012;7(11):e49872. PubMed PMID: 23185470; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC3503822. eng.

- Larcombe L, Mookherjee N, Slater J, et al. Vitamin D, serum 25(OH)D, LL-37 and polymorphisms in a Canadian First Nation population with endemic tuberculosis. Int J Circumpolar Health. 2015;74:28952. PubMed PMID: 26294193.

- Larcombe L, Coar L, editors. Sekuwe (My House): Dene First Nation’s Perspectives on Healthy Homes. Winnipeg, MB: Friesen’s Press; 2018.

- Helm J. The People of Denendeh. Ethnohistory of the Indians of Canada’s Northwest Territories. Iowa City: University of Iowa Press; 2000.

- Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada. First Nation Profiles 2016 [ updated August 21, 2010]. Available from: http://fnp-ppn.aandc-aadnc.gc.ca/fnp/Main/Index.aspx?lasng=eng

- Lytwyn VP. Muskekowuck Athinuwick Original People of the Great Swampy Land. Winnipeg, MB: University of Manitoba Press; 2002. ( Manitoba Studies in Native History; 12).

- Seymour DJ. From the land of ever winter to the American Southwest: Athapaskan migrations, mobility, and ethnogenesis. Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press; 2012.

- Canadian AIDS Society. Knowledge is Our Best Defence: an HIV/AIDS Education Resource for Canadian Schools. Ottawa, ON; 2010. Available from http://www.cdnaids.ca/wp-content/uploads/Knowledge-is-our-best-defence-HIV-curriculum-2010.pdf

- Oetting ER, Donnermeyer JF, Plested BA, et al. Assessing Community Readiness for Prevention. Int J Addict. 1995;30(6):659–683. PubMed PMID: WOS:A1995RA27300002; English.

- Plested BA, Edwards RW, Jumper-Thurman P. Community Readiness: A Handbook for Successful Change. editor. Tri-Ethnic Center for Prevention Research. Colorado: Colorado State University; 2006. Availble from http://www.ndhealth.gov/injury/nd_prevention_tool_kit/docs/Community_Readiness_Handbook.pdf

- Thurman PJ, Plested BA, Edwards RW, et al. Community readiness: the journey to community healing. J Psychoactive Drugs. 2003;35(1):27–31. PubMed PMID: WOS:000182326300004; English.

- Oetting ER, Jumper-Thurman P, Plested B, et al. Community readiness and health services. Subst Use Misuse. 2001;36(6–7):825–843. PubMed PMID: WOS:000170034900010; English.

- Kesten JM, Cameron N, Griffiths PL. Assessing community readiness for overweight and obesity prevention in pre-adolescent girls: a case study. BMC Public Health. 2013 Dec 20:13 PubMed PMID: WOS:000329314800002; English. Doi:10.1186/1471-2458-13-1205.

- Plested BA, Edwards RW, Thurman PJ. Disparities in community readiness for HIV/AIDS prevention. PubMed PMID: WOS:000246961400009; English Subst Use Misuse. 2007;424:729–739.

- Edwards RW, Jumper-Thurman P, Plested BA, et al. Community readiness: research to practice. J Community Psychol. 2000 May;28(3):291–307. PubMed PMID: WOS:000086721300005; English.

- Canadian Aboriginal AIDS Network. Assessing community Readiness and Implementing Risk Reduction Strategies. 2012. Available from http://caan.ca/wp-content/uploads/2012/05/CR-manual-eng.pdf

- Plested B, Edwards W, Jumper-Thurman P. Community Readiness Model. For HIV/AIDS Prevention. Vancouver, BC: Canadian Aboriginal AIDS Network; 2009.

- First Nations Information Governance Centre. The First Nations Principles of OCAP. Ottawa Ontario: National Aborignal Health Organization; 2007 updated 2016; Sept 2, 2016 May 11, 2016; Sept 11, 2016; Sept 2. Available from: http://fnigc.ca/ocap.html

- Woodgate RL, Zurba M, Tennent P, et al. A qualitative study on the intersectional social determinants for Indigenous people who become infected with HIV in their youth. Int J Equity Health. 2017 Jul 21;16(1):132. 10.1186/s12939-017-0625-8. PubMed PMID: 28732498.

- Health Canada. HIV/AIDS Epi updates – Chapter 1: national HIV prevalence and incidence estimates for 2011. Ottawa; 2014. Available from www.phac-aspc.gc.ca

- Flicker S, Larkin J, Smilie-Adjarkwa C, et al. “It’s hard to change something when you don’t know where to start”: unpacking HIV vulnerability with Aboriginal youth in Canada. Pimatisiwin: A Journal of Aboriginal and Indigenous Community Health. 2007;5(2).

- Bucharski D, Reutter L, Ogilvie L. “You Need to Know Where We’re Coming From”: Aboriginal Women’s Perspectives on Culturally Appropriate HIV Counseling and Testing. Health Care Women Int. 2006;27(8):723–747.

- Worthington C, Jackson R, Mill J, et al. HIV testing experiences of Aboriginal youth in Canada: service implications. AIDS Care. 2010 Oct;22(10):1269–1276. PubMed PMID: 20635240.

- Mill JE, Jackson RC, Worthington CA, et al. HIV testing and care in Canadian Aboriginal youth: a community based mixed methods study. BMC Infect Dis. 2008 Oct 07;8:132. PubMed PMID: 18840292; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC2573888.

- Bird Y, Lemstra M, Rogers M, et al. Third-world realities in a first-world setting: A study of the HIV/AIDS-related conditions and risk behaviors of sex trade workers in Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, Canada. SAHARA J. 2016 Dec;13(1):152–161. PubMed PMID: 27616600.

- Larkin J, Flicker S, Koleszar-Green R, et al. HIV risk, systemic inequities, and Aboriginal youth: widening the circle for HIV prevention programming. Can J Public Health. 2007;98(3):179–182. PubMed PMID: 17626380.

- Pelly D. The Old Way North: Following the Oberholtzer-Magee Expedition. Winnipeg, MB: Borealis Books; 2008.

- Manitoba Health, Seniors and Active Living. Annual Statistical Update: HIV and AIDS 2015. Manitoba Epidemiology & Surveillance Public Health Branch Public Health and Primary Health Care Division. Winnipeg, MB: EpiReport; 2016. Available from http://www.gov.mb.ca/health/publichealth/surveillance/hivaids/docs/dec2015.pdf