ABSTRACT

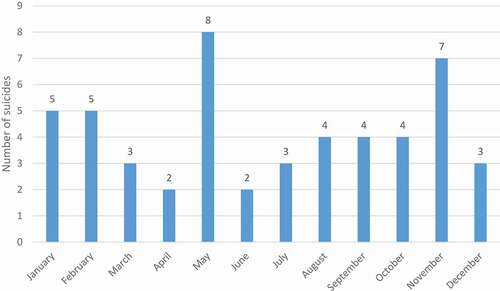

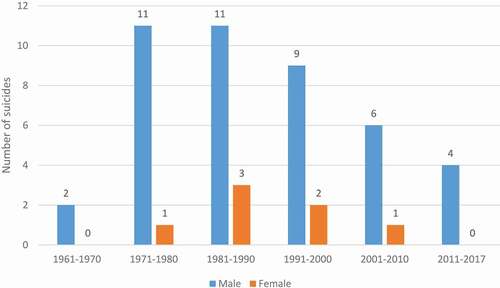

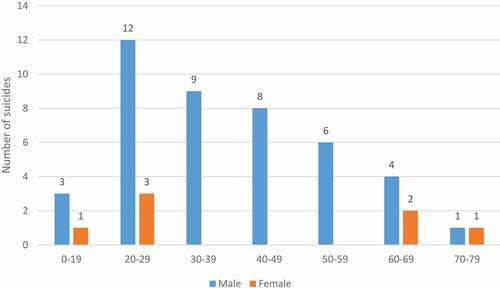

This study analyses suicides amongst reindeer herding Sámi in Sweden using information from the database of the National Board of Forensic Medicine. Suicides were identified using registers (39 suicides from 1961–2000) and key informants (11 suicides from 2001–2017). A great majority of cases were males (43 males, 7 females), and 50% occurred in the northernmost region. The mean age was 37.4 years with a peak in the group 20–29 years of age. Shooting was the most common (56%) method, followed by hanging. Blood alcohol concentration measures available from 1993 were above 0.2 g/l in 76% of the cases. There was a maximum incidence of suicides between 1981 and 1990. An accumulation of suicides in the months of May (N = 8) and November (N = 7) was seen. The annual suicide rate was estimated to be between 17.5 and 43.9 per 100 000 population. There was a clear gradient in suicide incidence with the highest being in the southernmost region (Jämtland/Härjedalen) and the lowest in the northernmost county (Norrbotten). For strengthened suicide prevention in this group, future research should address sex differences, the role of alcohol use and the general conditions for reindeer herding.

KEYWORDS:

Introduction

Suicide rates among indigenous peoples around the world are often, but not always, higher than among the majority population [Citation1] and have risen dramatically in the latter part of the 20th century in some parts of the Arctic [Citation2]. Today, young indigenous men living in the circumpolar Arctic account for some of the highest reported suicide rates worldwide [Citation3]. However, the suicide rates vary both within and across indigenous populations, in different territories and contexts. In Sápmi, the traditional Sámi homelands in Norway, Sweden, Finland and the Kola peninsula in northwestern Russia, the rates seem to differ from rates among other indigenous groups in the Arctic, as rates among Sámi are only moderately increased as compared to the majority populations in the same area [Citation2].

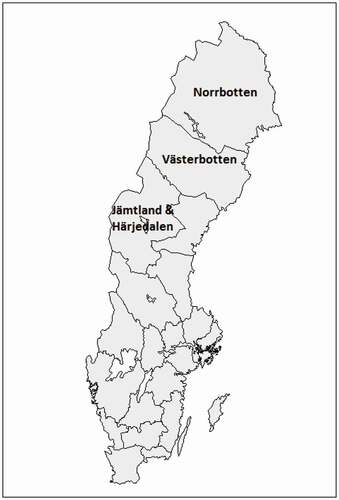

Figure 1. Map of Swedish regions with primary reindeer herding and Sámi settlement regions of Norrbotten, Västerbotten and Jämtland & Härjedalen marked. Map created with tool provided by Statistics Sweden

Silviken et al found a moderately increased risk of suicide among indigenous Sámi (Standardised Mortality Ratio, SMR, 1.27) in comparison with the rural majority population of northern Norway [Citation4]. These authors also found similarities between the suicidal behaviour of Sámi in Norway and among other indigenous peoples in the Arctic, including violent methods (firearms and hanging) being more common than in the majority population. Characteristics also found in other indigenous Arctic contexts included that the highest risk was found among young men, and suicide clusters contributed to the elevated suicide rate for Sámi in Norway. A study on mortality among Sámi in Sweden from 1961 to 2000 did not find an increased suicide risk for the general Sámi population, but a significantly increased risk among male Sámi reindeer herders (SMR 1.50) [Citation5]. However, in a study comparing the reindeer herders with non-Sámi living in the interior of northern Sweden, closer to Sámi reindeer herding communities, the higher suicide risk among male reindeer herders was reduced and non-significant (SMR 1.38) [Citation6].

Non-lethal suicidal behaviour, and being bereaved by suicide, has been found to be more common among reindeer herding Sámi than among non-indigenous majority populations in northern Sweden [Citation7]. Among young adult Sámi, being a reindeer herder, experiencing ethnic discrimination and living in South Sámi areas was related to elevated suicidality [Citation8]. Qualitative studies among Sámi in Norway and Sweden point to Sámi understanding suicide among them in a political context. Suicides are perceived as related to issues of indigenous rights, colonial history, discrimination and loss of reindeer grazing lands. Also, sociocultural dynamics such as traditional “hardening” up-bringing styles, lateral violence and multiplex relations among Sámi are being discussed in the Sámi discourse on suicide. The small, tight-knit Sámi community may result in many bereaved by each case of suicide [Citation9,Citation10].

Two small clusters of suicide among young male reindeer herders during the last decades made suicide a matter of great concern in the Sámi community. The authors have been engaged in a number of projects over time to study and contribute to prevent further suicides [Citation7–Citation10]. There is an urgent need for more data on the nature of reindeer herder suicide in Sweden [Citation11,Citation12]. Such knowledge could also contribute to our common knowledge about indigenous suicide.

In Sweden, reindeer herding is reserved for Sámi, and the right to own reindeer is exclusive to members of reindeer herding communities (RHCs), of which most are Sámi. The herders are semi-nomadic, following the seasonal migration paths of the reindeers over vast territories covering the majority of Sweden, most intensely in the three northernmost regions (). The industry is very important for Sámi in Sweden as an expression of culture, as a carrier of traditional knowledge and language, as well as to protect and uphold Sámi rights to land and water. There are 51 RHCs in Sweden, approximately 3500 reindeer owners and 220 000 reindeers.

The aim of this study was to analyse suicides among reindeer herding Sámi in Sweden with respect to age, sex, suicide methods, region and time of the year.

Material and methods

Almost all unnatural deaths, including suicides, in northern Sweden, are subjected to an investigation at the National Board of Forensic Medicine in Umeå. Aside from the information from the medico-legal autopsy, police reports and healthcare records are extracted, all of which are documented in a national database. The database entries hence include information on sex, age and blood alcohol levels as well as time, place and method of suicide.

A cohort of 7 482 members of reindeer herding Sámi families (4 451 men and 3 031 women) was constructed in a previous study [Citation5]. Cohort inclusion was operationalised in two steps. Reindeer herders were identified in the national occupation registers from 1960 to 1990, as well as the national register for reindeer herding enterprises. Family members of identified reindeer herders were included through the national kinship register. Through the Swedish National Cause-of-Death Registry, 39 cases of suicide were identified within the cohort for the period from 1 January 1961 through 31 December 2000. As the cohort register was destroyed in 2010, suicides amongst reindeer herding families in the period from 2001 to 2017 were identified through key informants within the Sámi reindeer herding context, adding another 11 suicides. Thus, altogether 50 suicides among Sámi reindeer herding family members were identified. Information from the database of the National Board of Forensic Medicine regarding these 50 suicides was collected.

Ethical considerations

According to Swedish legislation, there is no need for ethics board approval as regards using data on dead persons. However, well aware of the special ethical demands as regards research on suicide in minority populations and the special ethical demands as regards research involving Sámi, considering the historical unethical studies being done on Sámi, this study has been conducted informed by the ongoing discourse on Sámi health research principles [Citation13,Citation14]. The study was carried out in close collaboration with the Sámi community. The Sámi parliament in Sweden has approved the use of their register data on reindeer owners (Dnr 6.2.5-2017-812). The Sámiid Riikkasearvi (The National Union of the Sámi People in Sweden) contributed data on memberships in the RHCs. Respected and well-informed reindeer herders have been helpful as key informants on suicide in the reindeer herding milieu 2001–2017.

Results

The great majority of cases were males (43 males, 7 females), and 50% occurred in the northernmost region, Norrbotten, followed by the southernmost area Jämtland/Härjedalen (). The mean age was 37.4 years with a peak in the group 20–29 years of age. There were four young women aged 19–23, and three elderly women aged 64–76. Most suicides occurred between 1981 and 1990 (N = 14), after which the incidence decreased. Shooting was the most common suicide method, followed by hanging (). Women were represented in all categories of methods. Available data on alcohol concentration in blood from 1993 are shown in . Of all 21 cases 16 (76%) had blood alcohol concentration above 0.2 g/l (mean conc. 1.4 g/l) (). All cases (100%) after 2000 tested positive in this regard. With regard to the season of suicide, there was an accumulation in the months of May (N = 8) and November (N = 7) ().

Table 1. Number of suicides by sex, age and region

Table 2. Number and percentage of suicides method by sex

Table 3. Blood alcohol concentration 1993–2017 (g/l)

Based on a conservative estimate of the reindeer herders and their family members (2000 individuals) based on two population and housing censuses [Citation15] the crude rate of suicide was 43,9 pr 100 000 person years for the whole period 1961–2017. A liberal estimation of the members to 5 000 individuals based on data from National Union of the Sami people in Sweden will give a crude annual suicide rate of 17,5 per 100 000 person years.

Discussion

This is a descriptive case finding study on the occurrence of suicide amongst Swedish reindeer herding Sami. During the study period, 1961–2017 at least 50 suicides occurred. The majority of the cases were males (43 males and 7 females) and 50% occurred in the northernmost region of Swedish Sapmi. Shooting was the most common method (56%) followed by hanging. The mean age was 37.4 years with a peak in the group 20–29 years of age.

Time trends

We found that suicides in this study peaked in 1981–1990 (N = 14), after which it declined (1991–2000, N = 11) and seems to have stabilised at about half the incidence of the 1980 s (2001–2017, N = 11) (). However, because the methodology used for identification of cases changed from a register-based identification to use of key informants, this observed change might in part be a product of different inclusion criteria. On the other hand, this suicide incidence trajectory is similar to the annual suicide rate trajectory in the general Swedish population, which has decreased continuously since 1980 [Citation16].

Age groups

For men, we found the suicide incidence was highest among young adult men (20–29 years of age, N = 12), with a continuous decline in older age groups (). Among women, there was an accumulation of suicides among young adult women (20–29 years of age, N = 3), with the main finding being that no suicides were observed for middle-aged women, 30–59 years of age. Since we lacked demographic information, the calculation of suicide rates was not possible, and therefore comparisons with other populations should be done cautiously. However, the sex-age patterns found in this study were not similar to the patterns of sex-age suicide rates among the Swedish general population, at least not from 1980 to 2016 [Citation16], nor to the current situation in high-income countries in general [Citation17]. Instead, there are similarities with indigenous populations in the Arctic in general, and in Norway in particular. The general pattern of young indigenous persons, and especially young men, being most vulnerable to suicide is well known from other contexts in the Arctic [Citation2], including Sámi in Norway [Citation4]. Furthermore, the sex-age suicide rate pattern found in the Norwegian study is strikingly similar to what we found for incidences, including the relative peak among young males, followed by decreasing incidences during middle age and very few suicides in the eldest groups, regardless of sex.

Regional variations in suicide rates

Given that it is well known that most reindeer herding Sámi live in Norrbotten county and much fewer live in Västerbotten and Jämtland/Härjedalen, there seems to be a geographical gradient, with highest rate in the south. However, establishing such a geographical gradient is easier said than done as regionalised numbers of persons belonging to reindeer herding families are not available. If, however, the Reindeer Owners Registry is used as a proxy for the number of reindeer herding families, approximately 10% live in Jämtland/Härjedalen, another 10% in Västerbotten and around 80% in Norrbotten, furthest to the north. Based on these figures, there seem to be large differences in the suicide rates with the highest annual rate in the southernmost Jämtland/Härjedalen (56.1 per 100 000 persons), followed by 31.1 in Västerbotten and 11.0 in Norrbotten. However, to complicate this exercise even more, one should keep in mind that there are differences in suicide rates also within and between the majority populations in these regions. In a national Swedish comparison of the general population, Jämtland/Härjedalen had the highest suicide rate and Västerbotten had the lowest. Hence, the high rate in Jämtland/Härjedalen might in part reflect underlying factors that also affect the majority population. Furthermore, at least for the period from 2008 to 2017, the mean suicide rate in the municipalities where reindeer herding is most intense (i.e. in the sparsely populated mountainous and forest areas) were significantly higher (19.7) than in the eastern and coastal municipalities (15.3), where reindeer herding is less intense. Hence, rurality and other underlying factors are also likely to influence the suicide rate among reindeer herding Sámi.

The roles of sex and gender

We found a large sex difference, with a male:female ratio of 6:1 (43/7). Based on the liberal estimation of a total population of 5 000 reindeer herders, the annual crude suicide rate for males was 30.2 per 100 000 persons and 4.9 per 100 000 persons for females. Several factors could possibly contribute to this situation. Firstly, the skewed sex ratio is found all across the globe (with some exceptions) [Citation17]. In Sweden, the male:female suicide ratio varied between 2–3:1 between 1980 and 2016 [Citation16]. Hence, it is likely that whatever accounts for this skewness this also contributes to the situation among Sámi reindeer herders. Secondly, among Sámi reindeer herders, specifically women, might be protected by their higher education level [Citation18] and that they often have a full-time job outside the herding business, leading them to live more of their life outside the reindeer herding industry. Thirdly, Sámi reindeer herding women often fulfil many roles within their families, which even though highly burdensome [Citation19], might protect them from suicide. This might explain why suicides were found only among young and old women, but no cases among those aged 30–59. Fourthly, men might run a higher risk, as they are more often directly responsible for the herding business in the family. Fifthly, the focus on independence and autonomy in male gender roles is perhaps leading males into a gender trap, where they cannot ask for help or solve their personal problems [Citation9,Citation10,Citation20]. This is especially worrisome as the only study on mental health in the reindeer herding population in Sweden found that almost 40% of reindeer herding men reported clinically relevant (mild to severe) levels of anxiety symptoms, as measured with the Hospital Anxiety Depression Scale (HADS) [Citation21]. Sixthly, even though neither reindeer herders [Citation22] nor young adult Sámi [Citation23] in general have reported more problematic alcohol consumption patterns than other northern Swedes, a small proportion of male reindeer herders have indicated more problematic patterns (binge drinking) possibly connected to the seasonality of reindeer herding activities [Citation22]. Indeed, our finding that all cases after the year 2000 had a high blood alcohol concentration is an indication that the drinking culture in the (male) reindeer herding community should be addressed. Seventhly, the use of more lethal methods increases the risk of dying in a suicide attempt. This study found shooting, arguably the most violent method, to be very common among men (63%, N = 27), with shooting and hanging being the method in the great majority of cases among men (88%, N = 38). A study among Swedish men, followed from their enrolment as conscripts in 1969–1970 and for 37 years, found that use of firearms accounted for 11.2% and hanging/suffocation for 24.3% of suicides in that cohort [Citation24], suggesting a substantial difference in commonness for shooting, but not hanging, as methods between Swedish men in general and reindeer herding Sámi men. However, even though a study found no difference in proportion of the firearm method among men in Västerbotten and in Sweden as a whole in 1978–1980 [Citation25], firearms still accounted for 23% of male suicides from 1952 to 1993 in the same county [Citation26]. Furthermore, according to the Public Health Agency of Sweden, firearms accounted for 32% in Jämtland/Härjedalen, 22% in Västerbotten and 24% in Norrbotten of male suicides between 1997 and 2015. The relatively high proportions of suicide with firearms reported from northern Sweden are analogous with shooting as the method being more common in rural areas, as has also been shown in Västerbotten, where this method was 2.5 times more likely among those living outside the urban town of Umeå from 1952–1993 [Citation26].

Seasonality of suicides

Even though no statistical testing of the seasonality in suicides was performed in this study, there were some seasonal variations. The highest number of suicides was found in May (N = 8) and November (N = 7) (). Also, the mean incidence of suicides during the dark winter months of November through February (m = 5) was higher than during the rest of the year (m = 3.75). Interestingly, a study on the seasonality of male suicides in different occupational groups from 1988 to 1999 was conducted in Oulu region, Finland [Citation27]. These authors found that suicides among farmers (including reindeer herders) in the region happened more often during the spring months (March through May), and suicide among forest workers more often took place during the winter months. Possible explanations for the finding regarding farmers included the crucial importance of the spring months for the rest of the farming year. Analogous to this is that the outdoor nature of the forest workers’ everyday life means higher exposure to a harsh climate, as well as of lack of sunlight in mid-winter. The seasonality of reindeer herding suicides shows a similar pattern within both these occupational groups. Herders continue to work outdoors year round and are exposed to the harsh winter climate and lack of sunlight. In addition, this period of the year is characterised by much time spent alone, often in a herder’s cottage far away from the rest of the family. Hence, it is possible that the higher observed mean incidence during the winter months found in this study is related to the seasonality of reindeer herding. Furthermore, for reindeer herders, the crucial time period is concentrated in the month of May, when the reindeers give birth to their calves. In fact, the significance of this month for herding is illustrated by a number of Sámi names for the month of “May” (e.g. miessemánnu (“month of the reindeer calf”) in northern sámi and moarmesmánnu (“month of the reindeer foetus”) and guottetmánno ("month of the calving") in lule sámi). For reindeer herders, May should be the month when new life starts and the reindeer herding cycle renews, as well as when you get a sense of how last year was and how the new year is likely to continue.

Limitations of the study

Crude suicide rates are of interest and can be calculated from the presented dataset. However, the different inclusion methods in this study give rise to some problems. For the period from 1961 to 2000, inclusion was based on occupation and enterprise registers, as well as kinship registers. However, it might be argued that these inclusion criteria do not necessarily fit, as reindeer herding is more than an occupation and may be better described as a “way of life” [Citation28]. Also, in most reindeer herding families, the economy is reliant upon other (stabilising) sources of income (e.g. the woman in the family has a job in another sector, and the herder also takes up smaller jobs during periods of less intensive herding). Some of these inclusion issues might have been solved for cases after 2000, as inclusion then was based on “perceived belongingness to Sámi reindeer herding families” as judged by other reindeer herding Sámi (key informants). This latter approach certainly strengthened the ecological validity, but it also had drawbacks including that cases might have been missed due to key informants not knowing about them. Hence, cases identified after the year 2000 represent a minimum. Furthermore, the total population of reindeer herders is not well defined and different estimates could be used.

Hassler et al estimated, based on two population and housing censuses carried out in 1960 and 1980, that the number of members of reindeer herder families was ~2 000 [Citation15]. The mean number of Sámi reindeer owners in 2014–2017 can be calculated to be ~3 300, based on the reindeer owners registry. The National Union of the Sámi People in Sweden (Sámiid Riikasearvi), which organises the reindeer herding Sámi in Sweden, estimate the number of members in the Sámi reindeer herding communities to 5 000 individuals. However, not all members of reindeer herding communities live in reindeer herding families, as many take part only during intensive work periods, such as helping out during the marking of reindeer calves in the summer. All in all, the true number of members of reindeer herding families can be estimated in the range of 2 000–5 000, which makes the estimation of the suicide rate less reliable. A conservative estimate of the Sámi reindeer herding population in Sweden (2 000 individuals) results in a crude annual suicide rate of 43.9 per 100 000 persons for the whole period from 1961 to 2017, whereas a liberal estimation (5 000 individuals) puts the crude annual suicide rate at 17.5 per 100 000 persons.

Conclusions

There was an observed peak suicide incidence in the reindeer herding group in the period 1980 to 1990, with a possible decrease during the last two decades. Suicides were more common in younger age groups, especially among young men, and there was a great dominance of males, with a sex ratio of 6:1. It is noteworthy that we found no suicides among women aged 30–59 years. Shooting was the most common suicide method. It was also notable that from year 2001 onwards, all suicide victims had a high blood alcohol concentration. We conclude that improved suicide prevention among Sámi reindeer herders will, to a large extent, be dependent upon addressing suicidal behaviour among the male part of this population.

Acknowledgments

We thank Gergö Hadlaczky at the National Centre for Suicide Research and Prevention of Mental Ill-Health, Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden and Joakim Westerlund at the Public Health Agency of Sweden for data on regional suicide rates.

Disclosure statement

The authors report no conflict of interests.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Pollock NJ, Naicker K, Loro A, et al. Global incidence of suicide among Indigenous peoples: a systematic review. BMC Med. 2018;16(1):145.

- Young TK, Revich B, Soininen L. Suicide in circumpolar regions: an introduction and overview. Int J Circumpolar Health. 2015;74:27349.

- Lehti V, Niemela S, Hoven C, et al. Mental health, substance use and suicidal behaviour among young indigenous people in the Arctic: a systematic review. Soc Sci Med. 2009;69(8):1194–8.

- Silviken A, Haldorsen T, Kvernmo S. Suicide among indigenous Sami in Arctic Norway, 1970-1998. Eur J Epidemiol. 2006;21(9):707–713.

- Hassler S, Johansson R, Sjolander P, et al. Causes of death in the Sami population of Sweden, 1961-2000. Int J Epidemiol. 2005;34(3):623–629.

- Hassler S, Sjölander P, Johansson R, et al. Fatal accidents and suicide among reindeer-herding Sami in Sweden. Int J Circumpolar Health. 2004;63(Suppl 2):384–388.

- Kaiser N, Salander Renberg E. Suicidal expressions among the Swedish reindeer-herding Sami population. Suicidol Online. 2012;3:114–123.

- Omma L, Sandlund M, Jacobsson L. Suicidal expressions in young Swedish Sami, a cross-sectional study. Int J Circumpolar Health. 2013;72:19862.

- Stoor JPA, Berntsen G, Hjelmeland H, et al. “If you do not budget [manage] then you don’t belong here”: a qualitative focus group study on the cultural meanings of suicide among Indigenous Sámi in arctic Norway. Int J Circumpolar Health. 2019;78(1):1565861.

- Stoor JPA, Kaiser N, Jacobsson L, et al. “We are like lemmings”: making sense of the cultural meaning(s) of suicide among the indigenous Sami in Sweden. Int J Circumpolar Health. 2015;74:27669.

- Sámi Norwegian National Advisory Unit on mental Health and Substance Abuse, Saami Council. Plan for Suicide Prevention among the Sámi People in Norway, Sweden, and Finland. Karasjok, Norway; 2017.

- Stoor JPA. Kunskapssammanställning om psykosocial ohälsa bland samer [Compilation of knowledge on psychosocial health among Sami]. Kiruna, Sweden: Sametinget; 2016.

- Kvernmo S, Strøm Bull K, Broderstad A, et al. Proposal for ethical guidelines for Sámi health research and research on Sámi human biological material. Karasjok, Norway: Sámediggi/Sámi Parliament of Norway; 2017.

- Jacobsson L. Is there a special ethics for Indigenous research? In: Grugge AL, editor. Ethics in Indigenous research, past experiences – future challenges. 7 ed. Umeå, Sweden: Vaartoe – Centre for Sami Research; 2016. p. 45–56.

- Hassler S, Sjölander P, Ericsson A. Construction of a database on health and living conditions of the Swedish Sami population. Befolkning och bosättning i norr: etnicitet, identitet och gränser i historiens sken. Skrifter från Centrum för samisk forskning. Umeå, Sweden: Umeå Universitet; 2004. p. 107–124.

- Jiang G-X, Hadlaczky G, Wasserman D Självmord i Sverige. Data: 1980-2016 [Suicide in Sweden. Data: 1980-2016]. Nationellt centrum för suicidforskning och prevention (NASP), Karolinska Institutet, Stockholms läns landsting; 2016.

- World Health Organization. Preventing suicide: a global imperative. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2014.

- Kaiser N Mental health problems among the Swedish reindeer-herding Sami population: in perspective of intersectionality, organisational culture and acculturation [dissertation]. Umeå: Umeå University; 2011.

- Kaiser N, Näckter S, Karlsson M, et al. Experiences of being a young female Sami reindeer herder: A qualitative study from the perspective of mental health and intersectionality. J North Studie. 2015;9(2):55–72.

- Kaiser N, Ruong T, Salander Renberg E. Experiences of being a young male Sami reindeer herder: a qualitative study in perspective of mental health. Int J Circumpolar Health. 2013;72:20926.

- Kaiser N, Sjolander P, Edin-Liljegren A, et al. Depression and anxiety in the reindeer-herding Sami population of Sweden. Int J Circumpolar Health. 2010;69(4):383–393.

- Kaiser N, Nordström A, Jacobsson L, et al. Hazardous drinking and drinking patterns among the reindeer-herding Sami population in Sweden. Subst Use Misuse. 2011;46(10):1318–1327.

- Omma L, Sandlund M. Alcohol use in young indigenous Sami in Sweden. Nord J Psychiatry. 2015;69(8):621–628.

- Stenbacka M, Jokinen J. Violent and non-violent methods of attempted and completed suicide in Swedish young men: the role of early risk factors. BMC Psychiatry. 2015;15(1):196.

- Jacobsson L, Renberg E. Epidemiology of suicide in a Swedish county (Västerbotten) 1961–1980. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1986;74(5):459–468.

- Chotai J, Renberg ES, Jacobsson L. Method of suicide in relation to some sociodemographic variables in Northern Sweden. Arch Suicide Res. 2002;6(2):111–122.

- Koskinen O, Pukkila K, Hakko H, et al. Is occupation relevant in suicide? J Affect Disord. 2002;70(2):197–203.

- Nordin Å. Renskötseln är mitt liv: analys av den samiska renskötselns ekonomiska anpassning [Reindeer herding is my life: an analysis of the economic adjustments of the Sámi reindeer herding]. Umeå, Sweden: Vaartoe - Centre for Sámi research, Umeå university; 2007.