ABSTRACT

The present study arose from a recognition among service providers that Nunavut patients and families could be better supported during their care journeys by improved understanding of people’s experiences of the health-care system. Using a summative approach to content analysis informed by the Piliriqatigiinniq Model for Community Health Research, we conducted in-depth interviews with 10 patients and family members living in Nunavut communities who experienced cancer or end of life care. Results included the following themes: difficulties associated with extensive medical travel; preference for care within the community and for family involvement in care; challenges with communication; challenges with culturally appropriate care; and the value of service providers with strong ties to the community. These themes emphasise the importance of health service capacity building in Nunavut with emphasis on Inuit language and cultural knowledge. They also underscore efforts to improve the quality and consistency of communication among health service providers working in both community and southern referral settings and between service providers and the patients and families they serve.

Introduction

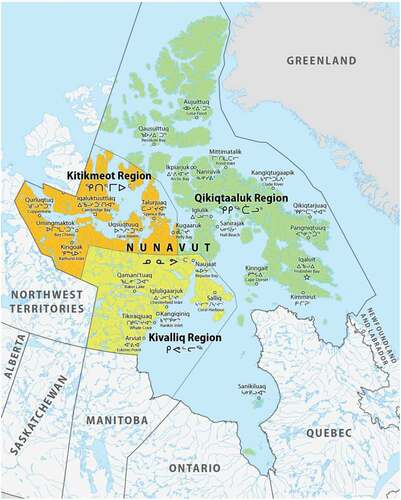

The landscape of healthcare Nunavut reflects the need to provide services across a territory with vast geography and relatively small population size. While Nunavut occupies 21% of Canada’s land mass, its population of about 36,000 live in 25 communities across three geographic regions () [Citation1]. The majority of the population (86%) are Inuit [Citation1] and this proportion is greater in smaller communities [Citation2]. Footnote1

In 2014, the Government of Nunavut published a 12-year retrospective analysis that identified cancer as the leading cause of death in the territory [Citation3]. While all-cause, age-standardised cancer incidence is lower than that of the Canadian population as a whole (362 vs. 406 per 100,000), incidence is disproportionately higher among women living in Nunavut (481.4 versus 369.0 per 100,000) and lower among men (239.4 versus 456.0 per 100,000). The leading site-specific causes of cancer in the territory are lung, digestive tract, and oral-nasopharyngeal cancers. Lung cancers accounted for 32% of all cancers reported 1999–2011 with incidence three times higher than in Canada as a whole and among the highest in the world [Citation4–Citation6]. Limited cancer screening and challenging diagnostic and treatment pathways for patients [Citation7] combine to produce high cancer mortality, particularly among women living in Nunavut, in whom malignant neoplasms are the largest contributor to the difference in life expectancy (8.5 years, on average) compared with women in the rest of Canada [Citation8] ().

These facts have prompted efforts to improve the journeys of cancer patients and their families as they navigate complex and often challenging courses of care. Particularly useful have been the efforts of Pauktuutit Inuit Women of Canada which has developed the Kaggutiq Inuit Cancer Glossary [Citation10] and the Inuusinni Aqqusaaqtara – My Journey toolkits [Citation11] to improve cancer literacy and support patients, families, caregivers and health service providers.

Along with these efforts, an emerging body of literature is documenting the capacity of existing systems to manage both the active treatment and palliative phases of care for residents of remote, northern communities. A recent ten-year analysis of Inuit patients diagnosed with Stage III or IV lung cancers revealed that fewer than half were able to travel to their home communities in Nunavut during the course of their treatment [Citation12]. An analysis of Inuit patients who received palliative radiotherapy at The Ottawa Hospital 2005–2014 indicated patients spent, on average, 65 days in Ottawa during the course of their first experience with referral care [Citation13]. Over that time period, patients received a median total of only seven calendar days of treatment, with fewer than one-third of patients able to travel back to their home communities during that period.

The present study emerged from a recognition that Nunavut families could be better supported during their cancer journeys through more knowledgeable efforts on the part of health service providers, both within the territory and in southern referral centres. Our goal in the present study was to gather perspectives from patients and families about the challenges they faced during their care journeys, and to explore how existing services might be shaped or enhanced to better support their needs. Our initial conversations with collaborators from the Department of Health and Nunavut Tunngavik Incorporated elicited concern that by focusing solely on cancer care we might miss aspects of care such as pain management and palliation that were of considerable concern to community members. As a result, we broadened our focus to discuss care of patients receiving active treatment for cancer and care of those who, regardless of diagnosis, were experiencing the dying process. The present study is the first step in a larger research effort to better understand the experiences of patients, families and care providers with experience of health service delivery in Nunavut communities.

Methods

Study setting and approach

The Nunavut Department of Health operates 25 community health centres and Qikiqtani General Hospital, a 35-bed acute-care facility in the capital city of Iqaluit, equipped and staffed for general anaesthesia, X-ray and ultrasound services. While general surgery and some specialist care are available, oncology services are provided at referral hospitalsFootnote2 in Edmonton, Winnipeg, Ottawa and to a limited extent at Stanton Territorial Hospital in Yellowknife, Northwest Territories.Footnote3 The Nunavut Medical Travel office coordinates travel for patients and accompanying family members whose costs are covered by the territory’s Healthcare Extended Health Benefits plans and by Health Canada’s Non-Insured Health Benefits program. Nunavut’s Department of Health manages a network of boarding homes in southern cities to support patients and family members travelling for acute or palliative care. The Home and Community Care office also manages a team of home care providers that work with community health centres to provide culturally appropriate care to people living in remote communities.

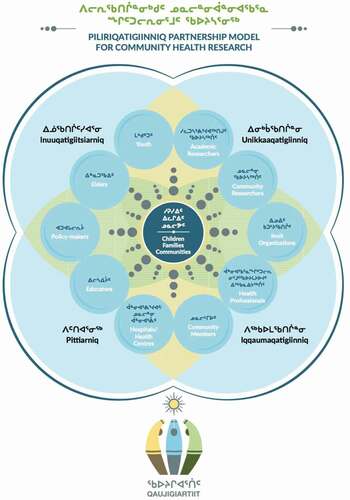

The Piliriqatigiinniq Model for Community Health Research [Citation14] guided the research activities from the study’s inception to delivery of results. Developed by Qaujigiartiit Health Research Centre, this research paradigm was created in response to a community-identified need for a health research process that is culturally consonant with values of Nunavummiut [people of Nunavut], with particular emphasis on producing knowledge in a holistic and collaborative way. The model highlights five Inuit concepts that inform the research approach (): Piliriqatigiinniq, the concept of working together for the common good; Pittiarniq, the concept of being good or kind; Inuuqatigiittiarniq, the concept of being respectful of others; Unikkaaqatigiinniq, the philosophy of storytelling and the power and meaning of story; and Iqqaumaqatigiinniq, the concept that ideas or thoughts may come into “one”. These concepts were employed throughout the research process.

The research protocol was developed collaboratively with partners from the Nunavut Department of Health and Nunavut Tunngavik Incorporated. The protocol was approved by the University of Toronto Research Ethics Board (Protocol 32,371) and licenced by the Nunavut Research Institute (Licence 06 007 17 N-M).

Recruitment and data collection

Participants were identified through referral sampling among our network of community partnerships which included representative, health, education and community support organisations in the Kitikmeot, Kivalliq and Qikiqtani Regions of Nunavut. Adult respondents (ages 18 years and older) self-identified as either having received cancer and/or end of life care; or having been closely involved in the care of a first degree relative (partner, parent, sibling or child).Footnote4 For the purposes of this manuscript, patient and family member participants will be referred to collectively as “community members”.

Semi-structured, open-ended interviews lasting 1–2 hours were conducted over a 15-month period by three trained Research Assistants (two Nunavut-based community researchers and one a southern-based graduate student) in community members’ homes using a series of 19 questions focusing on the patient’s care journeys. While we provided Inuktitut translations of all recruitment, information and consent materials and offered to provide translation where necessary, all respondents elected to be interviewed in English. An honorarium was provided to each participant in the form of a grocery store gift card.

Analysis

The interviews were recorded and transcribed by the interviewers. Text was imported into HyperRESEARCH software (©ResearchWare Incorporated) and a summative content analysis was undertaken [Citation17]. Text was coded according to units of meaning (words and phrases), first within data for each participant and subsequently across participant categories. We located consistent words and forms of expression that conveyed both meaning in and of themselves and larger themes identified as important to the interview subjects through their repetition or emphasis within the data as a whole. To strengthen the rigour of the analysis, coding and content analysis were undertaken first by two trained research assistants who analysed three transcripts concurrently, compared findings, then aligned their approaches to ensure consistency across the entire dataset. The analysis was then independently replicated by a senior investigator (TG), to ensure faithfulness to the participants’ perspectives and to reduce the potential for bias, and a preliminary set of results was compiled.

In accordance with the Inuit principle of Piliriqatigiinniq, preliminary results were shared with the entire study team through two rounds of intensive discussion, separated by a two-month time period. Through this process, interpretations were shaped by discussion and debate amongst researchers and community stakeholders until consensus was reached on all points of interpretation. This iterative process reflects the Inuit relational principle of Iqqaumaqatigiinniq, whereby knowledge is produced collectively through a “coming-together” of meaning after a cyclical process of dialogue and periods of reflection amongst knowledge makers [Citation16].

Results

Community member participants included 10 adults (3 men and 7 women) from three different Nunavut communities in both the Kitikmeot and Kivalliq regions of Nunavut. All participants had in the past provided cancer and/or end-of-life care for multiple family members; one was also a cancer survivor. While their diagnoses and care experiences were wide-ranging, the following themes emerged as being of significant concern for participants. We express them here through excerpts from participants’ transcripts, as representative of Unikkaaqatiginniq [the power of stories to share and build knowledge]:

Limited availability of screening and diagnostic services

Participants expressed a desire to see a greater range of cancer screening and diagnostic services offered within the territory:

I would really like to see more … more cancer um tests done up here or more screenings and I think even having a family history done whenever you go or at least if you haven’t been there in a while. Because now I have two parents who are gone and I … like I made sure to put that in my records just in case I get something. (Participant 6)

… some people, by the time they’ve diagnosed the problem, it’s too late. They’re already in their dying stage. (Participant 10)

Difficulties associated with extensive medical travel

All community member participants described instances of travel for diagnosis and treatment necessitating lengthy stays for patients and accompanying family members in southern referral hospitals.

[They] got [my mother] to the health centre and medivaced her out to Yellowknife. And then they couldn’t do anything in Yellowknife, so we went to Edmonton … we ended up in Yellowknife and then went to Edmonton. And then five hours later we were right back to Yellowknife and I ended up staying in a hostel with her for a week. And then another brother went down for a week after that and then … my little sister went down the third week and then … they moved her back up here when she was a little bit more stable. [Participant 9)

I had to go to Edmonton from Yellowknife. I had to go back to Yellowknife and then they shipped me off to Edmonton for cancer treatment … Me and my daughter. My daughter came with me four times. And my sister came with me twice. (Participant 8)

[Mother] got medivaced to Ottawa … maybe two or three weeks after my mom was down, my mom’s common law went back up North. Like to Iqaluit. And then my sister came down. (Participant 6)

Medical travel imposed significant burdens on families and communities in the forms of childcare, missing paid work, time away from family, and the financial costs of travel, only some of which was recouped through health insurance benefits:

(interviewer) Did you just travel with [your mother] once?”; (respondent) “More than once. I had to pay my way back. Just because I was escorting her not from Northwest Territories. From Nunavut. They don’t cover your travel. I said, ‘Okay, I’ll do it myself then.’ Yeah (Participant 5)

We have family in Ottawa that I was living with at the time, so they did all the driving, providing food for us, um all that out of their pocket …. “And financially … that’s a thing, you don’t know how long you’re going to be down there for and I ended up having to drop out of school because um I just didn’t know how long she … I had with her. (Participant 6)

Preference for care in community

Participants consistently stated a preference for care services to be located in their home communities, whenever possible within their own homes:

… all I want to do is be at home and enjoy the peace and quiet, have your family dinners and enjoy the view (Participant 9)

[My parents] They just wanted to go home and be home and be with the family and die at home. (Participant 10)

[Grandmother] wanted to be with her kids and her grandkids and her great grandkids. (Participant 4)

Participants described multiple instances where patients receiving referral care opted to remain in their homes rather than return for treatment at southern hospitals:

And [Grandmother] only travelled the one time to return? And then she decided to stay home and not seek treatment?” (interviewer); “She wanted to stay home. We kept her home … She did not want to be in the hospital in Yellowknife because that is not where her family is. I have six aunts and uncles in the community. She wanted to be with her kids and her grandkids and – and her great grandkids – we just didn’t want her gone. (Participant 4)

Preference for family involvement in care

Patients expressed a preference for care to be provided by family members, and family members in turn expressed a preference to be involved in the care of their loved ones whenever possible:

… we’d take shifts and my mom really wasn’t comfortable with other family looking after her, like helping her go to the washroom like she knew there were nurses for that, but my mom didn’t feel comfortable with that so. I was … it was either me and my sister help bathe her, help her to the washroom, help bring her back to bed. (Participant 6)

I was with my mom 24/7. If I went out, just outside the door for fresh air, that was as far as I could go. My mom would say, ‘Where are you? Where are you going? (Participant 10)

Challenges with communication

Some respondents related instances when they felt that health service providers failed to listen or respond appropriately to patients’ descriptions of symptoms, resulting in negative outcomes for patients:

For a year prior to [the] accident, she complained every time she went into the health centre. Every single time she went in and they gave her puffers. They gave her medication to help with her breathing. And nothing helped. So, after she fell down, they went and got sent out the x-ray showed that there was a mass in her lung … .My auntie, she was also diagnosed with cancer. She had breast cancer. And she went in you know and said my breast is sore, but they didn’t listen to her. I don’t know if it was the language barrier or they just – they don’t have the resources or they’re just not listening. (Participant 4)

Participants described multiple instances where news about a family member’s diagnosis or treatment was conveyed to them back home over the telephone:

From my dad, he – he told us on the phone. He told me on the phone when he was in Ottawa. (Participant 6)

My sisters phoned me and said, ‘Ah, mom went to Edmonton and she was diagnosed with cancer’. (Participant 5)

Patients and family members described the importance of health-care providers giving accurate information to family members about their loved one’s diagnosis and care:

What I would like to say for different diagnosis, for different types of cancer if the nurses or whoever … whoever knows about the cancer, if they could explain to the whole family what the mother might be experiencing. If she’s allowed to have morphine, what kind of drugs she’s taking, what kind of care is available to them? (Participant 5)

… we weren’t ever instructed as to how to take care of [our mother], what to do if something happened. We were just left on our own … . We didn’t know what kind of foods to give [our mother], what not to give her. What to do if something happened. Not a thing. (Participant 10)

Some participants expressed frustration over staff use of medical jargon in southern hospitals:

… yeah scientific, medical terms that you know oftentimes I’d be like, “What the __ are you saying?” Honestly. You remember you’re talking to humans who don’t understand what you’re saying. Yeah … I just get so upset and there were a couple of times I cried … (Participant 6)

Many patients and family members emphasised the importance of reliable translation services for effective health-care delivery:

It would be good to have like translators who know these medical terms, not only here at the hospital in our community, in Ottawa or Edmonton (Participant 6)

If there’s a language barrier, then that’s when you bring an interpreter in. Um, have them point to where it hurts, you know? If they had done that with my grandmother, I think they would have been able to catch the cancer sooner than they had done. (Participant 4)

Family members frequently described being in the difficult situation of serving as a translator for a family member receiving difficult or complicated information about diagnosis or treatment:

… after the doctor told me the options that I had to – or we had ah I had to tell my brother because he … like he was relying on me to tell him what was happening … And I had to go through that with him you know and, and we talked, you know, and when and finally and I told him you know like should I tell them okay if they had to, if they had to revive you, you know they will probably … and you know you could have broken ribs and they could go through your lungs … and it won’t be good. … and finally, he said okay, don’t revive, if that happens don’t revive me … that was, that was one of the hardest you know um things I had to tell him. (Participant 2)

Family members expressed concern that on occasion southern health-care providers may rely on unqualified translators:

… there are families out there who are unilingual. And the kid or the partner will go down as the escort but does that necessarily mean that they have all the Inuktitut words to translate these medical terms. (Participant 6)

Challenges with culturally appropriate care

Pain was a particular aspect described by a number of respondents, who remarked that care providers mistook failure to request pain medication, or to rate pain highly, as absence of severe pain:

… my mom … I would say she was on um pain of nine, but she would downplay that pain. She would – she would be like crunched up like holding her stomach and she’s like ‘mmm’ and she wouldn’t let me – she wouldn’t let me press the button to get pain medication until she was like – she was crying of pain (Participant 6)

Some respondents described family members maintaining a strong sense of independence throughout their illness:

My mother-in-law was very independent, so she wasn’t required care like fluff up the pillows or anything. She just laid down on the couch. That’s what she wanted to do. People visit because they know she was dying. But she would be up and making tea with them and [laughing] she served them instead [laughing] … She didn’t want to be bedridden or anything like that. She just did what she needed to do. (Participant 5)

And then two years later my mom got sick. And, of course, she didn’t tell us either. It’s just the way Inuit people are. You don’t bring your problems to somebody else to burden them with. (Participant 10)

One participant described examples of Inuit forms of non-verbal communication that might not be properly interpreted by caregivers who lack awareness of local dialect or gestures:

… just you know we scrunch our noses to say ‘no’ or we raise our eyebrows to say other things, like ‘we need more’ (Participant 6)

Participants suggested care could be improved if caregivers asked families about traditional Inuit ways of coping with illness and dying in the community:

Yeah, even like having information like that that’s geared more towards culturally would be nicer … Like asking ‘What did you use to do? What’s the traditional way?’ (Participant 7)

Because we do respect the elders and they are about to journey on to the next life. (Participant 3)

Role of the land in healing

Respondents emphasised the importance of being on the land, and traditional foods harvested from the land, to the well-being of both patients and family members caring for their loved ones:

I had one of my cousins bring me my ATV and we went up … I just love the mountains and everything up there, so I climbed up that mountain halfway and I just sat there for a good hour, soaking it all in. The air. The openness. The view. I could see for miles to the ocean, to the islands. It was up in land from where my grandparents used to camp. (Participant 10)

… the on the land program, it does wonders for people (Participant 3)

Value of service providers with strong ties to the community

According to patients and family members, the most satisfactory interactions with service providers were with individuals who have served for many years in the community and were therefore highly knowledgeable about the language, customs, families and community ways. Many of these positive characterisations of health service workers involved home care providers:

The homecare workers, … they are some of the hardest workers … people in town. And I think that because they’re primarily from [town] they knew the language – they know the language, they know the family history. They tried to make it as comfortable as possible for my [Grandmother] … They were very close to us because they had spent quite a bit of time with our family. (Participant 4)

There was one particular nurse … it was a home care nurse … she was so respectful to me. (Participant 5)

Discussion

Our findings are consistent with recent qualitative research that highlights the importance of effective communication, cultural awareness, and strong relationships between service providers and the communities they serve [Citation18,Citation19]. Unlike southern Canadians, the care experiences of northerners are overwhelmingly characterised by medical travel. The distances involved necessitate complicated flight paths involving multiple transfers and overnight stays en route [Citation20]. There is an urgent need to more fully document the extent and impact of medical travel from patient, family and service provider perspectives [Citation21].

While patients and family members expressed dissatisfaction with many aspects of the current system, their responses were not characterised by demands for sweeping reforms. People appear well aware of the resource constraints attendant on acute and palliative care provision in remote communities. Overwhelmingly their feedback centres on improving the current system through thoughtful, culturally informed, incremental change.

Both patients and family members expressed a strong preference for care in their home communities whenever and wherever possible. In Nunavut, the preference for community-based care includes a desire for greater availability of screening and diagnostic services, borne out of a perception that many cancers are diagnosed “late”. In limited ways, the territory has expanded screening and diagnostics services, with mixed results to date. An analysis of data from the 2012 Canadian Community Health Survey reveals that while cervical cancer (Pap) screening rates among women in the territories (73.1%) are among the highest in Canada, colorectal screening rates (faecal occult blood testing and colonoscopy) are among the lowest (41.3%) [Citation22,Citation23]. Remote radiology interpretation and diagnostic services are provided by The Ottawa Hospital Cancer Centre [Citation24], though these services reach only a limited proportion of the Nunavut population. A recent pilot of electronic consulting service (eConsult) shows potential for replacing medical travel in some circumstances [Citation14].

The desire for locally based services also reflects a desire for services that are integrated within supportive family and community networks. These networks are viewed as not only necessary to the comfort of patients, but integral to the processes of active treatment and healing. Research has documented the value of family and peer support for Inuit in making decisions about care options such as radiation and chemotherapy [Citation25]. A shared decision-making model developed and implemented in the Qikiqtaaluk Region of Nunavut (its title translated by Inuit as “Not Deciding Alone”) has been shown to improve care efficacy, particularly in the areas of communication and cultural competence [Citation26].

Community-based, family-centred care is extremely important in the context of palliative care. This is not surprising; even in southern contexts, family members rate the quality of end of life care lower when patients die in hospitals, rather than at home [Citation27]. In Indigenous palliative care contexts, spiritual and cultural beliefs about death and dying are built around connection to the land and to family. There is a rich emerging literature on the complexity of Māori dying practices involving inter-generational exchanges of knowledge, roles and responsibilities that must be accommodated [Citation28]. Novel approaches to end of life care for First Nations people in Canada provide spaces and supports for people wishing to die in their home communities, surrounded by extended family members and interacting with the natural environment through ceremony and the use of traditional foods and medicines [Citation29]. Anderson and Woticky provide insights about how this approach can be operationalised in urban contexts to provide end of life care that honours the physical, mental, emotional and spiritual elements of First Nations personhood [Citation30]. Our research indicates the need for greater emphasis in the area of culturally informed care for Inuit, whose remote service landscape and cultural identity are distinct.

A particularly useful precedent is that of a Nunavik project exploring end of life care for Inuit living in Quebec. A qualitative study revealed tensions between traditional Inuit dying practices and the experiences of Inuit within centralised, institutional systems of care [Citation31]. In contrast to people’s descriptions of feeling isolated and exhausted by medical travel, people who experienced the death of a family member in their home community described the final stages of dying as follows:

… homes are filled with family and friends of all ages. Participants described that as adults and children are present, this accompaniment may include conversation, song, silence, prayer, games, storytelling, laughter, sharing of food, and assistance with the activities of daily life. At [end of life], food preparation, housecleaning, mortician services, and funeral preparations are shared among family members, members of faith-based women’s auxiliaries, and others close to the patient or family. Family members may also work alongside of nurses and physicians to provide direct care. In addition, the community-run hunter’s support group and the local co-operative store supply families with food as needed … .participants told us that local stores provide resources such as food baskets to families during and after the death of a family member [Citation29]., pp. 649–650

This description aligns with many preferred aspects of care described by our respondents: care at home with extended family present and the involvement of professional caregivers highly knowledgeable about the Inuit cultural and community context. Other researchers emphasise the need for familiarity and trust among caregivers and families in both palliative and cancer care settings [Citation18,Citation27,Citation32,Citation33]. In our study, community members described personal gestures on the part of health service workers as comforting. Study participants expressed gratitude for caregivers’ skill and gentleness with patients, qualities that align well with the Inuit value of Pittiarniq [being kind]. Intimacy and connection among care providers and families is a highly valued and important part of culturally relevant care.

Challenges with communication are a persistent issue in the literatures of both cancer and end of life care, not only among Indigenous populations but in Canada as a whole. In a recent review of culture and palliative care, researchers found that caregivers’ attitudes, beliefs and lack of knowledge about patients’ cultural backgrounds led to stereotyping practices and misinterpretations about pain and suffering [Citation34]. Hordyk et al. describe how cultural and communication errors can lead to breakdowns in relationships of trust:

Examples of Qallunaat [non-Inuit] social workers arriving uninvited to the home of a grieving family, of an interpreter required to work when a family member had died, of country food not permitted in health center premises, of community members not given space to wash the body of the deceased or, these and other breakdowns in communication were described as avoidable with adequate training [Citation31]., p. 652

Miscommunication in the area of pain management is an aspect of community care requiring action. Studies report misconceptions among health service providers about the severity of pain experienced by patients and fears among patients that service providers may conflate pain reports and addictive behaviours [Citation34]. Patients sometimes express reluctance to request opiates and other pain medication when family members have a history of substance abuse, either from fear of placing their loved ones at risk or of developing reliance themselves. Cancer Care Ontario’s Aboriginal Palliative Care Toolkit contains helpful guides and resources to enhance communication such as its “Guidelines for Working Together” brochure, designed to guide service providers and families encountering issues in patient management such as pain control and decision-making [Citation35].

The use of family members as interpreters is another area of particular concern. Sixty-three percent of Inuit residents speak an Inuit language [Citation1], and the lack of capacity for translation services – both within-territory and at southern referral hospitals – has long been identified as a gap in the health-care system [Citation36]. Hordyk et al. describe the “moral distress” of family members called upon to serve as interpreters during medical decision-making, outlining the many ways in which persons unused to or unqualified for this task are nevertheless employed by health professionals as conduits and interpreters of complex and often distressing health information [Citation37]. Often these interactions are complicated by layers of cultural significance unknown to health service providers, leading to stressful experiences for both interpreters and patients. The authors conclude that while family member interpretation is a widely used practice, it may at times be “ethically indefensible” [Citation37], p. 2.

The frequent use of family member interpreters in northern contexts arises from the large proportion of non-resident health service providers working in communities. Two avenues to address this challenge include greater emphasis on health service capacity-building within Nunavut, particularly among Inuit language speakers; and the development of training programs for informal translators who may be called upon to support care decisions in community and southern referral care settings.

A final but pressing issue is the challenge of ensuring comprehensive and accurate transmission of information between communities and southern referral hospitals. The Canadian Partnership Against Cancer describes this challenge as one of “poor transitions between communities and care settings” [Citation36] and it is clear the problems are bi-directional. Clear communication about care management decisions is essential to effective service delivery and both patient and family satisfaction [Citation33,Citation39].

The present study is part of a larger research project exploring priorities for cancer and end of life care management in the territory. Limitations include reliance on a sample that lacks representation from Qikiqtaaluk, the most populous region of Nunavut. We did not collect detailed demographic information on respondents, so it is possible that the challenges experienced with care may vary by age or gender or socioeconomic status. The strengths of the research are the use of an Inuit-centred approach and strong connections to key decision-makers who guide health service provision in Nunavut.

Conclusion

Our findings demonstrate that, despite considerable efforts on the part of the Nunavut Department of Health and its staff to provide high-quality, culturally relevant, supportive care to patients and their families, there are areas where improvements are possible, particularly in the areas of community-specific cultural knowledge and effective communication. The overarching message we heard from community members is that the quality of cancer and end of life care is strengthened by strong connections between patients, families and their community-based care providers. Familiarity with the community, knowledge of local people and customs, and openness to Inuit forms of healing and support are essential components of health-care practice in Nunavut. Careful and concerted attention to all aspects of health-care communication will foster and improve the quality of care received by Nunavummiut.

This study is part of a larger effort by Nunavut partners to ground cancer and end of life service delivery within the wishes and priorities of Nunavummiut.Footnote5 A Continuing Care Needs Assessment conducted in 2015 identified home and community care and palliative care as priorities for continued investment [Citation40]. This aligns with national efforts towards systems-based improvements in cancer and end of life care [Citation19,Citation41–Citation43]. In its Canadian Strategy for Cancer Control, the Canadian Partnership Against Cancer lists as priority number one: “culturally appropriate care closer to home” (p. 7) within its section on care relevant to First Nations, Inuit and Métis people [Citation44]. Recently the Nunavut Department of Health announced plans to have northern-based physicians follow patients throughout their care journeys, to eliminate some of the trust and communication issues arising from transfers between communities, Qikiqtani General Hospital, and southern referral hospitals [Citation44]. Additional efforts within the territory include emphasis on colorectal and other screening initiatives to improve care across the spectrum from control to diagnosis to active treatment and, if necessary, palliative care [Citation38].

To date we have shared findings with hospital, home and community care administrators, physicians and nurses in the territory. Future efforts include development of an information package for caregivers undergoing orientation to community settings, and a series of guides for improved practice in the areas of pain assessment, family engagement and use of Inuit language interpreters in healthcare and community settings. As well, findings from a related study of Nunavut health service provider perspectives will shed new light on the challenges attendant on care provision for Nunavut patients and families experiencing transfers between regional and southern care facilities, including consistency in communication of advanced care directives.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (32.5 KB)Acknowledgments

We are grateful for the participation of the many community members who generously shared their stories with us. A number of community-based interviewers and students supported this project; we wish to specifically acknowledge the contributions of Papatsi Kotierk, Lissie Anaviapik, Emilia Nevin, and Lily Amagoalik. We are also grateful for the guidance and support provided by Jennifer Colepaugh and Katie Bellefontaine, of the Nunavut Department of Health; and by Shylah Elliott and Sharon Edmunds-Potvin, of Nunavut Tunngavik Incorporated.

Disclosure statement

The authors report no conflict of interest.

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed here.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Inuit are an Indigenous people who reside in Inuit Nunangat, the Inuit homeland, which comprises the northern part of Canada. Nunavut is one of the four sociopolitical regions that make up Inuit Nunangat. (https://www.itk.ca/about-canadian-inuit/).

2 Since 2014, e-consult has been used on a limited basis in some Nunavut communities. A recent analysis indicates e-consult may be a viable alternative to medical travel in some cases [Citation14].

3 Chemotherapy services have been offered by the Northwest Territories Health and Social Services Authority since 1991. In December 2017, chemotherapy services were suspended due to a program review that indicated improvements were needed. The service resumed at Stanton Territorial Hospital in April 2018 [Citation15].

4 We collected only limited demographic information on subjects (gender only) due to the small sample size and high risk that individual subjects could be identified in the data by their age, location, or diagnoss.

5 Collective term for the residents of Nunavut (https://www.gov.nu.ca/culture-and-heritage/information/missionvisionvalues).

References

- Statistics Canada. Focus on geography series, 2016 census. Ottawa, Ontario: Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 98-404-X2016001, Data products, 2016 Census; 2017.

- Statistics Canada. Nunavut [Territory] and Canada [Country] (table). Census profile. 2016 census. Ottawa, Ontario: Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 98-316-X2016001; 2017 Nov 29.

- Government of Nunavut. Cancer in Nunavut, 1999–2011. Iqaluit, Nunavut: Population Health Information. Yellowknife Northwest Territories, Department of Health; 2014 Fall cited 2019 Oct 15. Available at: https://www.gov.nu.ca/health/information/health-statistics

- Asmis TR, Febbraro M, Alvarez GG, et al. A retrospective review of cancer treatments and outcomes among Inuit referred from Nunavut, Canada. Current Oncol. 2015;22(4):246–12.

- Carrière GM, Tjepkema M, Pennock J, et al. Cancer patterns in Inuit Nunangat: 1988–2007. Int J Circumpolar Health. 2012;71(1):18581.

- Circumpolar Inuit Cancer Review Working Group, Kelly J, Lanier A, Santos M, et al. Cancer among the circumpolar Inuit, 1989–2003. II. Patterns and trends. Int J Circumpolar Health. 2008;67(5):408–420.

- Tungasuvvingat Inuit and Cancer Care Ontario. Cancer risk factors and screening among Inuit in Ontario and Other Canadian regions. 2017 cited 2019 Oct 15. Available from: http://www.cancercare.on.ca/InuitRiskFactors

- Peters PA. An age- and cause-decomposition of differences in life expectancy between residents of Inuit Nunangat and residents of the rest of Canada, 1989 to 2008. Ottawa (Ontario): statistics Canada, Catalogue no. 82-003-X. Health Rep. 2013;24(12):3–9.

- Office of the Auditor General of Canada. 2017 March Report of the auditor general of Canada: health Care services – Nunavut. Ottawa (Ontario): Office of the Auditor General of Canada; 2017 Mar. cited 2019 Oct 15 Available from: http://www.oag-bvg.gc.ca/internet/English/nun_201703_e_41998.html

- Pauktuutit Inuit Women of Canada. Kaggutiq Inuit cancer glossary. 2020 cited 2020 Apr 13. Available from: https://www.pauktuutit.ca/health/cancer/kaggutiq-inuit-cancer-glossary/

- Pauktuutit Inuit Women of Canada. Inuusinni aqqusaaqtara - My journey. 2020 cited 2020 Apr 13. Available from: https://www.pauktuutit.ca/health/cancer/inuusinni-aqqusaaqtara-journey/

- Kirk LG, Hammond A, Nwafor A, et al. Improving treatment experience for Nunavut patients with lung cancer. Radiat Oncol. 2019;104(1):247.

- Chan J, Linden K, McGrath C, et al. Time to diagnosis and treatment with palliative radiotherapy among Inuit patients with cancer from the arctic territory of Nunavut. Clin Oncol. 2019;2019. [E-pub ahead of print]. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clon.2019.07.001.

- Healey GK, Tagak SA. Piliriqatigiinniq ‘working in a collaborative way for the common good’: A perspective on the space where health research methodology and Inuit epistemology come together.”. Int J Crit Indigenous Stud. 2014;7(1):1–8.

- Hseih HF, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res. 2005;15:1277.

- Kelley ML, Prince H, Nadin S, et al. Developing palliative care programs in Indigenous communities using participatory action research: a Canadian application of the public health approach to palliative care. Ann Palliat Med. 2018;7(Suppl. 2):S52–S72.

- Koski J, Kelley ML, Nadin S, et al. An analysis of journey mapping to create a palliative care pathway in a Canadian First nations community: implications for service integration and policy development. Palliat Care. 2017;10:1–16.

- McDonnell L, Lavoie JG, Healey G, et al. Non-clinical determinants of Medevacs in Nunavut: perspectives from northern health service providers and decision-makers. Int J Circumpolar Health. 2019;78:1571384.

- Young TK, Tabish TB, Young SK, et al. Patient transportation in Canada’s northern territories: patterns, costs and providers’ perspectives. Rural Remote Health. 2019;19(2):5113.

- McDonald JT, Trenholm R. Cancer-related health behaviour and health service use among Inuit and other residents of Canada’s north. Soc Sci Med. 2010;70:1396–1403.

- Singh H, Bernstein CN, Samadder JN, et al. Screening rates for colorectal cancer in Canada: a cross-sectional study. Can Med Assoc J. 2015;3(2):E149–157.

- Doering P, DeGrasse C. Enhancing access to cancer care for the Inuit. Current Oncol. 2015;22(4):244–245.

- Jull J, Mazereeuw M, Sheppard A, et al. Tailoring and field-testing the use of a knowledge translation peer support shared decision-making strategy with First nations, Inuit and Métis people making decisions about their cancer care: a study protocol. Res Involv Engagem. 2018;4:6.

- Jull J, Hizaka A, Sheppard AJ, et al. The Inuit medical interpreter team, Rand M, Habash M, Graham ID. An integrated knowledge translation approach to develop a shared decision-making strategy for use by Inuit in cancer care: a qualitative study. Current Oncol. 2019;26(3):192–204.

- Higgins PC, Garrido MM, Prigerson HG. Factors predicting bereaved caregiver perception of quality of care in the final week of life: implications for health care providers. J Palliat Med. 2015;18(10):849–857.

- Moeke-Maxwell T, Wharemate R, Black S, et al. Toku toa, he toa rangatira: a qualitative investigation of New Zealand Māori end-of- life care customs. Death Dying. 2018;13(2):30–46.

- Fruch V, Monture L, Prince H, et al. Coming home to die: six nations of the grand river territory develops community-based palliative care. Int J Indigenous Health. 2016;11(1):50–74.

- Anderson M, Woticky G. The end of life is an auspicious opportunity for healing: decolonizing death and dying for urban Indigenous people. Int J Indigenous Health. 2018;13(2):48–60.

- Hordyk SR, Macdonald ME, Brassard P. End-of-life care in Nunavik, Quebec: Inuit experiences, current realities, and ways forward. J Palliat Med. 2017;20(6):647–655.

- Donnelly S, Prizeman G, Ó Coimín D, et al. Voices that matter: end-of-life care in two acute hospitals from the perspective of bereaved relatives. BMC Palliat Care. 2018;17:117.

- Heyland DK. What matters most in end-of-life care: perceptions of seriously ill patients and their family members. Can Med Assoc J. 2006;174(5):627–633.

- Cain CL, Surbone A, Elk R, et al. Culture and palliative care: preferences, communication, meaning, and mutual decision making. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2018;55(5):1408–1419.

- Cancer Care Ontario. Palliative care toolkit for aboriginal communities.cited 2019 Nov 11 Available from: https://www.cancercareontario.ca/en/guidelines-advice/treatment-modality/palliative-care/toolkit-aboriginal-communities

- Bowen S Language barriers in access to health care. Ottawa: Health Canada; 2001. (Report, Cat. No H39-578/2001E).

- Hordyk SR, Macdonald ME, Brassard P. Inuit interpreters engaged in end-of-life care in Nunavik, Northern Quebec. Int J Circumpolar Health. 2017b;76(1):1291868.

- Beben N, Muirhead A. Improving cancer control in First Nations, Inuit and Métis communities in Canada. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl). 2016;25:219–221.

- Fraser SL, Nadeau L. Experience and representations of health and social services in a community of Nunavik. Contemp Nurse. 2015;2–3:286–300.

- Government of Nunavut. Continuing Care in Nunavut 2015 to 2035. Iqaluit (Nunavut): Department of Health; 2015 Apr.

- Lavoie JG, Kaufert J, Browne AJ, et al. Managing Matajoosh: determinants of First Nations’ cancer care decisions. BMC Health Serv Res. 2016;16:402.

- Aherne M, Pereira J. A generative response to palliative service capacity in Canada. Int J Health Care Qual Assur. 2005;18(1):iii–xxi.

- Carstairs S, MacDonald ML. The PRISMA symposium 2: lessons from beyond Europe. Reflections on the evolution of palliative care research and policy in Canada. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2011;42(4):501–504.

- Canadian Partnership Against Cancer. Canadian strategy for cancer control. Toronto: Canadian Partnership Against Cancer; 2019 cited 2019 Oct 16. Available from: https://www.partnershipagainstcancer.ca/cancer-strategy/

- McKay J Nunavut government hopes to streamline cancer care in the territory. Iqaluit (Nunavut). CBC News Online; 2019 Sept 10 cited 2019 Oct 15. Available at: https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/north/health-nunavut-cancer-1.5276756

- Government of Northwest Territories. Stanton territorial hospital chemotherapy services update. Report, department of health. 2018 Apr cited 2019 Oct 15 Available from: https://www.nthssa.ca/en/stanton-territorial-hospital-chemotherapy-services-update-april-2018