ABSTRACT

Etuaptmumk or Two-Eyed Seeing (E/TES) is foundational in ensuring that Indigenous ways of knowing are respected, honoured, and acknowledged in health research practices with Indigenous Peoples of Canada. This paper will outline new knowledge gleaned from the Canadian Institute of Health Research and Chronic Pain Network funded Aboriginal Children’s Hurt & Healing (ACHH) Initiative that embraces E/TES for respectful research. We share the ACHH exemplar to show how Indigenous community partners take the lead to address their health priorities by integrating cultural values of kinship and interconnectedness as essential components to enhance the process of community-led research. E/TES is conceptualised into eight essential considerations to know in conducting Indigenous health research shared from a L’nuwey (Mi’kmaw) perspective. L’nu knowledge underscores the importance of working from an Indigenous perspective or specifically from a L’nuwey perspective. L’nuwey perspectives are a strength of E/TES. The ACHH Initiative grew from one community and evolved into collective community knowledge about pain perspectives and the process of understanding community-led practices, health perspectives, and research protocols that can only be understood through the Two-Eyed Seeing approach.

Introduction & Context

The terms Indigenous and First Nations are used interchangeably in this paper. In reference to the Mi’kmaq(w) the word L’nu is used. It is the original word of identity that roughly translates to people that speak the same tongue. L’nuwey is the original word to describe anything that derives from being and living L’nu, or L’nuk, its plural form. The perspective that derives from L’nu knowledge that encapsulates the way of thinking and being is L’nuwita’simk [Citation1].S

Etuaptmumk/Two-Eyed Seeing (E/TES) originates and mirrors how L’nuk in Mi’kma’ki have evolved within a constant state of flux as a Nation in their way of living and being within that eco-space of Mi’kma’ki, ancestral territory of L’nuk. Elder Albert Marshall shares that our Nation has had to adapt to the evolving circumstances of our ancestors by innovating our ways of thinking because of the impacts of colonialism as well as the natural progress of time (A. Marshall, personal communication, 4 November 2020). Elder Marshall coined the term E/TES in 2003 and it was first published in 2004 [Citation2], yet it has been a part of L’nu tribal consciousness since the early colonial period. This paper does not provide a historical account of the progress of E/TES; however, it is critical to understand that the evolution of E/TES has been a deliberate and gradual process because L’nuk had to coexist with the rapidly changing landscape of their ecosystem with which they had to now share with settlers. Their co-existence ebbed between conflict and peace, which eventually benefited the settler enfranchisement as a dominant society. E/TES has a long history, which has only been documented and utilised from a western perspective since the Marshalls coined the term. Nevertheless, trained western-based academics and researchers have difficulty grappling with E/TES by categorising it within epistemic boundaries in order to comprehend it within comparative philosophies of western science. Dr Battiste, L’nu scholar, reminds us that “Indigenous knowledge … defies categorization” [Citation3, p. 11] and more importantly, L’nuwita’simk is fluid, adaptable, and continuously evolving to address contemporary issues within present time and space. Questioning the empirical nature of E/TES is questioning the integrity of L’nuwita’simk and the whole cultural knowledge of a Nation. In this paper, we show how E/TES is applied into various research contexts. We honour the nature of that knowledge continuum as a deliberate process of being and living L’nu, while addressing health through E/TES without purposely defining it within western-based empirical concepts.

It is often surprising to non-Indigenous people that First Nations have their own traditional knowledge regarding health and wellness and most Nations, like L’nuk, rely on this knowledge as their primary source of health information. It is a sophisticated network of knowledge-holders, Elders and healers guided by epistemological and scientific practices based on a worldview of experiences and logical validation [Citation4] who implement traditional knowledge and western-based science to seek solutions in health.

Indigenous Peoples are the original gatherers and interpreters of knowledge meant to benefit their people. Over time, their right to have control of their knowledge, people’s health and culture has been taken away, and disrespectful treatment from external research teams has led to an atmosphere of caution, uncertainty, and distrust among many Indigenous communities. The Mi’kmaq Nation (L’nuk) are not exempt from harmful colonial systemic practices in research, so the best way to prevent ethics breaches, or to avoid colonial research practice, is for Indigenous-led research to share the knowledge of current and evolving practices from their perspectives. In order to change the future state of wellness, Indigenous Peoples need to implement their knowledge that will directly impact health outcomes. Being involved in research is a gateway to validating traditional knowledge so it can be used more widely to improve health, generate new knowledge and control the narrative that will inform better health policy and appropriate resource allocation.

There are several moving parts to this conversation: first, recognising the rightful owners of the knowledge, and second, understanding who is most invested in how the knowledge is gathered and used to benefit and support Indigenous people. This paper will discuss the experience of the E/TES “relational” way of conducting research, with and by Indigenous People. Researchers, predominantly white settlers, have not had/taken the opportunity to learn Indigenous Peoples’ histories and the tragic past that has led to distrust and unhealthy, imbalanced unions between researchers and Indigenous Peoples. Indigenous People want to gather their specific health knowledge and want to participate in studies that will advance their health and wellness.

Being a Respectful Partner & Champion

Non-Indigenous researchers have an ethical duty to educate themselves about Indigenous health research processes and to build more inclusive partnerships with the Indigenous people whom they wish to serve. Non-Indigenous researchers should not assume a stance of being experts on Indigenous health issues; however, they play a critical role as allies [Citation5]. We recognise that non-Indigenous researchers go beyond the role of allies when they become advocates of decolonisation in research and healthcare practices – we refer to them as champions. We adopted the term champion as Indigenous partners to recognise non-Indigenous researchers who go above and beyond the role of ally. There is no rubric as to who a champion is because the process is not necessarily quantifiable, yet our community understands when one is a champion, in a similar sense when we know a person as an Elder. They have accumulated a set of skills, knowledge and conscience, and they have demonstrated a high level of reciprocity and advocacy on behalf of our community. Dr Marcia Anderson, a Cree-Anishinaabe scholar, physician, and activist, shares that “research will be transformative at the structural level to benefit Indigenous Peoples only if it is explicitly antiracist and anticolonial” [Citation6, p. E931]. Non-Indigenous researchers who are champions have acquired this consciousness by listening, observing and working closely with their Indigenous colleagues over time.

Research respecting a balanced approach and involving community members, Elders, patients, clinicians and researchers will facilitate strong Indigenous health partnerships with Indigenous communities using an E/TES approach [Citation7, Citation8: Citation9]. This paper will outline eight specific considerations gleaned from the work of the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) and Chronic Pain Network (CPN) funded Aboriginal Children’s Hurt & Healing (ACHH) Initiative that embraces respectful research with Indigenous People from an E/TES perspective.

Enhancing our Understanding around Indigenous Health Research

There has been a groundswell of support and heightened interest in conducting Indigenous health research in response to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission Calls to Action [Citation10,Citation11]. Nevertheless, communities and universities struggle to keep up with the interest and demand to operationalise E/TES in research with few champions and Indigenous researchers.

As mentioned above, Etuaptmumk is a co-learning approach based on the respectful and meaningful integration of Indigenous knowledge with western knowledge coined by Elder Albert Marshall [Citation2,Citation12–14]. Its foundation is implementing an agreed-upon process of research that reflects communities’ beliefs, values and ways of knowing and doing. This paper advances the understanding that E/TES can be used as a methodology because it justifies the ways research can be conducted using L’nuwey knowledge to pave the way in choosing appropriate methods. The implementation of E/TES recognises that research is based on L’nuwey knowledge in congruence with community skills, talents, and resources [Citation5] throughout the entire process to purposely shift decision-making, leadership, and control to L’nuk and Indigenous partners. The aim is to apply trauma-informed approaches during the patient-engagement process and integrate the community’s recommendations regarding best practices to engage Indigenous People.

The other key component of E/TES in ACHH’s research was to avoid “deficit-discourses” [Citation5, p. E619] especially knowing the historical trauma Indigenous Peoples suffered from colonial paradigms of research and racism. Many well-meaning non-Indigenous researchers wade into Indigenous health research wanting to make a difference. However, they may not have the benefit of knowing the history of Indigenous people, systemic racism in healthcare, the impact of that history on trust and health or even Indigenous health beliefs and interaction with the health system, let alone research protocols.

Elders guide the way forward by reminding us that within the Seven Sacred L’nuwey teachings, love, honesty, humility, respect, truth, patience and wisdom, humility comes before wisdom [Citation15]. This is an essential foundational lesson to learn. These cultural teachings are embedded as L’nuwey perspectives or principles in humanising Indigenous Peoples’ engagement in healthcare using E/TES [Citation16,Citation17]. Researchers are trained in a western, colonial system that typically places the researcher in control of the knowledge they gather through their research, gaining benefit via grant awards, publications and presentations. There is often not a sound understanding of how to develop, interpret or be accountable for the knowledge having an impact or benefit to Indigenous People. Relational and beneficial research needs to be a priority at the outset simply because Indigenous knowledge derives and evolves from relationships [Citation12, p. 144]. Research projects that are grounded in a relationship that is reciprocal and trusting are more likely to have better outcomes for all parties involved [Citation18]. Despite this, practical resources to guide communities and researchers through the logistics of the engagement process are limited. The authors emphasise that there is no one-size-fits-all for Indigenous health research. ACHH is an exemplar of how this knowledge evolved through an E/TES approach and partnership. The ACHH Initiative uses E/TES to gather and share Indigenous knowledge with the goal of improving Indigenous health outcomes and health care experiences in the area of pain and hurt.

Eight Guiding Considerations Emerging from the ACHH Initiative

The ACHH (pronounced “ache”) Initiative is research emerging from a partnership between Dr. Margot Latimer of Dalhousie University/IWK Health and L’nu Eskasoni First Nation Health Director, Sharon Rudderham. The overarching vision of ACHH is to gather and mobilise Indigenous knowledge that will improve the health care experience and health outcomes, especially in the area of pain care. Together, with a team of Indigenous and non-Indigenous health researchers, community members and clinicians, they delved into why the numbers of referrals for paediatric pain treatment were so low when rates of painful conditions were so much higher when compared to non-Indigenous children [Citation19]. Early discoveries included the notion that there was no translatable word in L’nuisuti (Mi’kmaw language) for “pain” [Citation20], logically impacting pain assessments and secondly, that L’nu children and youth were not seeing pain-related specialists at the same rate as non-Indigenous children even though their pain-related diagnoses were significantly higher than their non-Indigenous comparative group [Citation19].

The eight guiding considerations emerged over a period of ten years through a series of research projects and continuous leadership by the Indigenous community. Starting with the ACHH Maritimes project from 2008 to 2014 [Citation19,Citation20] and consolidated during the Chronic Pain Network expansion, ACHH National, in 2015–2020 which included projects in Winnipeg, Hamilton and Halifax. The E/TES approach was the research framework, in theory and methodology, for all the projects, which Elder Marshall would also consider as part of “knowledge gardening” [Citation14, p 5]. Through this process and vigorous and intricate communication between Co-Principal Investigators, Indigenous community leaders, researchers, collaborators, clinicians, and Elders, the ACHH team has conceptualised eight guiding considerations that are recognised as key steps in developing and maintaining meaningful research alliances with Indigenous partners.

1. Community Engagement is All About Relationship Building

2. Community Protocols and Ethics

3. Capacity Development is About Reciprocity

4. Indigenous Research by Design

5. Data Considerations, Protection & Pathways

6. Data Interpretation & Analysis

7. Community Knowledge Validation

8. Gardening, Dissemination & Benefit of Interpretations

1. Community Engagement is All About Relationship Building: The L’nu experience

Kinship in Research Development

ACHH’s relationship-building and community engagement is based on the L’nuwey value of kinship, whereby strong relationships must exist before any research can take place. This concept is identified through similar Indigenous-focused research articles [Citation21–23]. In order to overcome generations of mistreatment and trauma, non-Indigenous people must take the time to establish a genuine and meaningful reciprocal relationship with their Indigenous partners. This process will allow community members, Elders and leaders to determine researchers’ true intentions and also allow researchers to learn about the particular people they are partnering with, their knowledge and values. These values will assist in understanding the community priorities and the benefit of the research to the community.

Community engagement is a core process in building partnerships with Indigenous communities, yet western-based research often overlooks it as a building block of meaningful and respectful research that permits the maximum reciprocity level [Citation24, p. 44]. Dr Margaret Robinson, a L’nu scholar, goes further and explains that “reciprocal obligation” [Citation25, p. 63] is embedded in kinship’s cultural values. The moral responsibility is to honour that kinship between people and people with animals, by respecting the holistic nature of reciprocity whereby one sacrifices itself for the other’s benefit. Robinson refers to oral traditions about hunting and using the entire animal with minimum waste. It honours and respects the animal’s sacrifice for human use by using every part for tools, food, and clothing. The nature of reciprocity is to use the knowledge allotted through kinship to maximise the benefits for humans without waste or disregard. In this research, it is the use of L’nu knowledge that is used to maximise the benefits. It ensures holistic reciprocity to improve the lives of Indigenous people.

The majority of research-based funding does not necessarily support research staff having the time to foster meaningful relationships without producing traditional “deliverables” in a time-constrained manner. The ACHH Initiative received funding which allowed the first year of the project to be a kinship year to establish meaningful research partnerships that may lead to Indigenous-led health and innovative services [Citation7, p. E208]. This process required a significant budget allocation towards travel, community engagement (catering, honorariums, etc.) and personnel support and benefited greatly from ACHH’s long-standing relationship with First Nations in the Atlantic region and nationally through the CPN and the CIHR's Strategy for Patient-Oriented Research . Researchers who do not have established relations with a community or an Indigenous group would greatly benefit by including this component into their research design and funders, acknowledging it in their review criteria. Successful community engagement consolidates, apart from trust-building and communication protocols, the Indigenous methods that best suit the partner’s perspectives and needs. All of ACHH’s project components integrated quantitative and qualitative methods aligned with Indigenous ways of knowing and community-based participatory research within the E/TES approach.

ACHH’s research work is part of a continuum of reciprocity that transcends a typical research timeline that is usually linear in time and trajectory. There were no written rules about the engagement process; it was learned by trial and error and became a key learning piece directed by the specific community. The journey of establishing relationships is as important as the “destination” (Hatcher et al., p. 145).

2. Community Protocols and Ethics: Approvals, community presentation, researchers

“Protocols are a means to ensure that activities are carried out in a manner that reflects community teachings and are done in a good way. The same principle ought to apply to research” (Kovach, Citation26, p. 124).

Throughout the kinship process, a partnership begins to develop through an understanding of community protocols and perspectives on culture and health and their conceptualisation of ethical research. Indigenous communities have developed processes to protect their sovereign and inherent rights that involve their way of life. Therefore, Indigenous groups have developed various protocols for community engagement, consultation and research. The latter is continuously evolving due to the increasing demands to address health and environmental impacts on Indigenous Peoples’ well-being in Canada. The disparities in healthcare and barriers in accessing health, including the debilitating nature of systemic racism and disrespectful research based on the colonial paradigms, only further alienate Indigenous people. The only logical response is for Indigenous people to implement what they have done for thousands of years and use their knowledge to address their health needs.

Adherence to the Tri-Council Policy Statement on Research with Indigenous People (Chapter 9) [Citation27] as well as an understanding of the OCAP (Ownership, Control, Access, Possession) principles [Citation28] is essential before any first step in the research process. The ACHH Initiative submitted to both the IWK Health Research Ethics Board and the Mi’kmaw Ethics Watch (MEW)board for approval to research with the L’nu Nation. IWK Health is the institution where the research funds are held. The institutional Research Ethics Board respects the Indigenous ethics processes and requested that the work be approved by an Indigenous ethics board first out of respect for process. MEW ensures that the L’nu individual and collective interests are protected, including their knowledge and heritage, their implementation in research methods and dissemination of findings [Citation29]. Indigenous and treaty rights protect MEW as principles of self-determination and self-governance. Internationally, the rights of Indigenous people, including L’nuk, are protected by the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples as stated:

Article 31 1. Indigenous peoples have the right to maintain, control, protect and develop their cultural heritage, traditional knowledge and traditional cultural expressions, as well as the manifestations of their sciences, technologies and cultures, including human and genetic resources, seeds, medicines, knowledge of the properties of fauna and flora, oral traditions, literatures, designs, sports and traditional games and visual and performing arts. (UN General Assembly, 2007, p. 22)

Nationally, the OCAP principles [Citation28] and the Tri-Council Policy Statement: Chapter Nine: Research Involving the First Nations, Inuit, and Metis Peoples of Canada [Citation27] offer frameworks for Indigenous health research that are essential points of departure for researchers to begin planning their research design. However, researchers must consider more layers of protocols before “research” can happen with Indigenous people and the community. Researchers are also subject to the community, cultural and tribal or territorial protocols that may further guide research based on specific Nations’ interests. For example, the ACHH Initiative had to go through a vigorous community engagement process, including Elders and community health boards, before submitting the proposal to a tribal ethics process. Time, resources to travel, and Elder engagement protocols need to be considered.

As part of the CPN relationship, ACHH team members established the Indigenous Health Research Advisory Committee to allow stakeholder groups (researchers, trainees, community members and leaders) to explore established protocols and practices in this area. This committee is comprised of community members, Elders, patients, clinicians, and health researchers from across Canada, and the committee has created an online repository of information available to researchers interested in knowing more about Indigenous health research practices (https://achh.ca/knowledge-research/ihrac/; https://vimeo.com/472699187).

3. Capacity Development is about Reciprocity

The ACHH knowledge-building process with its partners in Mi’kma’ki slowly evolved from a level of trust-building to a mutual-trust level. This relational approach includes building capacity development for research so that the community can lead their research addressing their health priorities.

One of the main principles in partnering with First Nations is understanding their knowledge systems and what capacity development is from a community perspective. Western-based capacity development often involves students as trainees in research mentorships, assistantships, and a hybrid of either capacity, which the ACHH Initiative aims to develop through partnerships. However, community partners have expanded the scope of capacity development from a community perspective. Indigenous community partners are often perceived to have less “capacity” for research than their partners from health centres and universities. However, Dr Marie Battiste, L’nu scholar, confirms that Indigenous foundations of knowledge are scientific and practice logical validation [Citation3, pp. 7–8], which are essential in any research process. Willie Ermine shares that the frustration for Indigenous People is the notion of “western universality” that dictates a monocultural view of life from the west. Ermine states that the Canadian society is ingrained with that societal “undercurrent” of western consciousness [Citation30] that projects western perspectives as dominant, which has evolved into negotiating ethical spaces. It seems that the undercurrent is to take from the Indigenous to build up the West, or just as damaging, to ignore Indigenous consciousness as part of the fabric of the Canadian foundation. In a relatable way, Dr Battiste et al. [Citation31, pp. 86–87) describes “cognitive imperialism” as the western way of knowing that it systemically maintains its dominance in the academe. Indigenous scholars have had to advocate through action, scholarship, and sheer persistence to centre Indigenous knowledge in research, including Indigenous perspectives and practices, especially in addressing Indigenous health issues.

The whole concept of research capacity results from the dominant western consciousness and cognitive imperialism that continue to question the Indigenous community’s capacity in research. Therefore, Indigenous communities in the Atlantic region, especially communities like Eskasoni First Nation, are innovating ways to do research that address the needs of the community and the expectations of capacity development. Capacity building, from an E/TES perspective, captures the circle of learning, in that researchers learn from community members, community members learn from Elders, and community members learn from researchers. This concept is an expanded definition of the typical western notion of “training” or capacity building. This reciprocal relational approach has allowed the partnership to create ways to address the gaps by hiring community people to conduct the research while building their capacity for interviewing, data gathering and transcribing. The ACHH project created synergy between community members who wanted to learn about research as health leaders and others, to advance their knowledge in graduate education. There was a truly reciprocal relationship with this experience. Care had to be taken with Indigenous trainees in western training programmes to be reminded to honour their knowledge systems and not feel pressured to view only western practices as the gold standard.

Creating Safe Hiring Practices

There are existing barriers in hiring Indigenous people to conduct research outside of the Indigenous community. While existing protocols for hiring research assistants for community-based research require in-depth screening to protect both researchers and human subjects, some of the requirements may not be seen as equally relevant from the community perspective. Indigenous community members have deep traditions of keeping their people and knowledge safeguarded; therefore, they prefer to hire Indigenous researchers who have personal and social connections and trust in the community. This type of trust in community members goes beyond the level of education and years of experience because families, parents, leadership, and Elders can vet their own people – not a third-party agency who may dismiss potential candidates because of stringent western-based screening processes or academic credentialing. The hiring of community people embeds a sense of community accountability or “shared liability” [Citation1, p. 26], in which the community, through cultural practice and collective consciousness, respects the codes of ethics and professionalism. This translates into a sense of pride that is expected of students and young people as a member of the community. It goes beyond the monetary value of the position as a researcher because that person will be a part of a community project that helps the community address health needs, and this is an example of “collectivism.”

4. Indigenous Research by Design: Indigenous perspectives (Cycle of Life), E/TES, community-driven, timeline considerations

In 2014, the CIHR, through its Institute of Aboriginal Peoples’ Health strategic plan, officially recognised the importance of E/TES in Indigenous health research by “Encouraging the use of Indigenous Ways of Knowing and Two-Eyed Seeing as a means of setting research priorities, and determining what interventions are suitable and how they can be implemented at the community level and ultimately scaled up” [Citation32, p.6]. Since 2012, there has been a steady increase in the implementation of E/TES by researchers. ACHH has situated all its research within this framework since its first engagement in the Eskasoni First Nation in 2008.

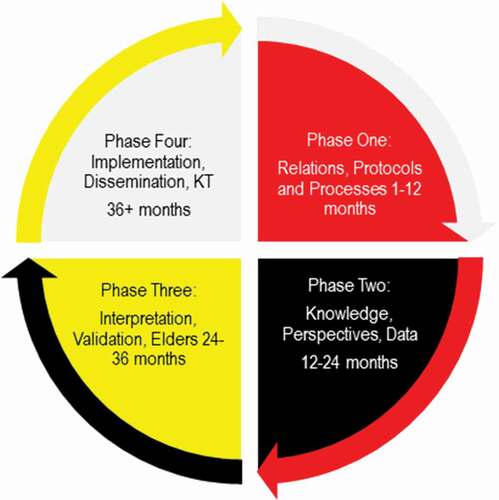

The timeframe of any research with Indigenous communities has to consider the community’s needs and the capacity to research from their perspective and availability. represents the average time each phase of the ACHH research took, conceptualised in a Four Directions Model representing the cycle span of research within our Indigenous communities.

Figure 2. Kloqowej (star): Courtesy of the Nova Scotia Museum, Ethnology Collection

The circular visual is reflective of the L’nuwey worldview of the circle of life that is embedded in L’nuwey cultural knowledge. For example, the Kloqowej (L’nuwey Star; ) “symbolizes the inter-relatedness of everything and everyone in the land of the Wapana’ki and the great circle of friendship” [Citation1, p. 99]. Young shares that the directions of the star represent the following principles: East for Peace that is foundational in guiding the actions of L’nuk (people) and with others (non-Indigenous and non-human); South is the principle of Kindness that evolves into alliances and friendships within the community and with others within the space; West is the Sharing principle that integrates the sense of social behaviours that borders both individual and collective actions within guided values; finally, North is the Trust principle that acknowledges the importance of the renewal of relations and ritual process of trust development through a series of protocols and relationships. Young shares these principles in a legal framework of the L’nuwey justice system; however, the framework of L’nuwey knowledge is applicable to areas like health and education because it is derived from a L’nuwey worldview that oversees all other areas of the life of L’nuk.

The L’nu perspective applied to research is the guiding principle that we follow when conducting any research in the Wabanaki region. Based on that protocol, we were able to establish relations with the Wabanaki Health Centre in Bangor, Maine. Since we are part of the Wabanaki region, it is customary to follow similar principles in that area. The learning needs of the Wabanaki team were tailored to share information about research ethics and designed to support where this team was in their learning journey.

The important visualisation of a circular model in both images represents how time is of a continuum that coincides with the direction of knowledge produced and reciprocated into the community.

5. Data Considerations, Protection and Pathways: Two-steps forward, one-step back, repeat

Western science refers to scientific data as a collection of information that is objective and quantifiable [Citation33, p. 1], but for Indigenous people that knowledge being collected is sacred because it derives from a collective consciousness based on a person’s story. Sacred is applied in a non-secular way; it knows that the information collected about an individual is animate because it is derived from lived experiences.

Through the collection of these experiences, it is essential that researchers respect that “data” is sacred, not merely collectable statistics. The data, or stories and art, represent individual and collective experiences of people of a community with a collective memory around pain and hurt. It is critical that those experiences imprinted in the data be protected, respected, acknowledged and understood to be an integral part of a nationhood’s knowledge development system that continuously evolves into the collective consciousness.

The lived experiences, whether they are stories, data utilisation, or self-reported pain experiences, are treated as they are sacred experiences and translated using an E/TES approach so that they are understood by western-trained clinicians. It is a careful process respecting the heightened risk for a potentially traumatising experience that it creates for Indigenous team members collecting and interpreting the information and those participants sharing their experiences, especially when Indigenous youth are among the most vulnerable in Canadian society. ACHH shared these perspectives with the Art Gallery of Nova Scotia (AGNS) when they curated the Indigenous youth’s collected art. The AGNS was a partner in knowledge translation and dissemination of the art and its narratives. There was a noticeable treatment of the art as living pieces because of the Gallery’s intrinsic value placed on the spirituality of the youth who made them. We believe that if researchers view the data, and the entire research project, in the same light, it would make a huge difference in how the research is perceived.

The steps to protect the data need to be careful and respectful and acknowledge the animacy and sacredness of that knowledge. These are essential considerations to be taken. Using the knowledge that exists and that is owned by the individual Nation, in this case, L’nuwey knowledge is protected by the MEW as a Nation to ensure the safety and sacredness of the knowledge and experiences gathered.

6. Data Interpretation & Analysis: Respectful, time, meaningful input, true collaboration

The interpretation of information or data that is also contextualised as spiritual by Indigenous people is a complex process of respectful coordination that takes place long before the knowledge is “gathered.” In E/TES, the element of time to develop and nurture relationships with the community is a process that will also nourish the sharing or gardening process later. Using knowledge is like using resources for L’nuk; it is a balance of resource development, management and cultivation, which we refer to as Netukulimk. Netukulimk is a concept mainly used in ecological contexts. Yet, the Elder Albert Marshall states that the concept is transferable into contexts that are relatable to our use of resources (A. Marshall, personal communication, 4 November 2020). The use of knowledge, especially by Elders, is no different. Data interpretation is part of the cultivation, and for continuous respectful data gathering, data interpretation has to be a thoughtful and deliberate process. Our Elders are the source of our knowledge, and they are sensible and sensitive to environmental impacts just like our plant resources. Therefore, data interpretation in its most accurate form has to consider those human factors whereby Elders are protected, respected and honoured for their role in the process. The who, what, where, when and why of data and knowledge is an essential understanding in the E/TES research process.

These considerations have evolved throughout the ACHH Initiative growth to a national level and interaction with several Indigenous communities after core knowledge amassed in the Maritime region. For example, in the site engagement with Winnipeg, Hamilton, Bangor and Halifax, Elders and Knowledge Holders were included from the beginning. In that process of engagement, Indigenous youth were also included in the community engagement discussions because they are the direct participants and the priority focus of the study. The process to include youth was carefully planned to include supports during the discussions in case of triggers, anxiety, or distress that may be experienced by anyone. Elders and a community nurse were present during these discussions. The decision to include the youth was by the community partner with complete knowledge and approval by the Elders on the project. The result is a compelling experience that empowers the entire research as community-led and participatory of many community people who deal with chronic pain and hurt and who have health care experiences that we can learn from. The ACHH results gathered in the Maritime provinces described this process [Citation19,Citation20]

Once project details were finalised, Indigenous methods for collection (talking or sharing circles) and data analysis (four directions or medicine wheel) were applied. Multiple forms of data were collected, including quantitative health data and qualitative talking circles, individual storytelling and artwork. These data sources expand the understanding of what quantitative health data shows by respecting the Indigenous ways of knowing, such as with Indigenous children expressing their knowledge through story and art [Citation19]. The data were also analysed using L’nuwey perspectives within four dimensions of health experiences that are physical, mental, emotional, and spiritual. In the same manner, quantitative data require a deep understanding of community context and non-Indigenous people who do not have this experience should not be independently interpreting Indigenous Peoples information whether it is qualitative or quantitative.

7. Community Knowledge Validation: Findings, fact checks, shareable data, next steps

The community validation process is an opportunity to regroup the research advisory, the community leadership, Elders and collaborators in a meaningful discussion about the findings, data, and asking questions and providing answers about the overall research. It would equate to a thesis defence. The first process of validation is to get the knowledge-holders and Elders to have adequate time and space to capture and provide feedback on every shareable piece of information that may be released to the public. This is when the research project team fact checks all data, language, new findings, and potential outcomes.

The community needs to have an adequate allowance of time to properly comprehend, absorb and digest this knowledge from a community perspective which may require interpretation or translation in the community’s first language, even if the project had originally agreed to use English, French or both.

The Elders and community collaborators are more than an advisory. They are the checks and balances of community consciousness, enabling knowledge to flow from theory to practice during research. It is the Elders and community collaborators who will validate that knowledge to be shared more broadly. The community relies on Indigenous knowledge by Elders and knowledge holders to corroborate, evaluate, and guide the research. They are the “experts” of our knowledge even though Elders may not use that language to describe themselves because they follow the principle of humility before wisdom. They inform the research team and the (co)principal investigators to ensure a balanced approach. In the absence of such a process, the community will be vulnerable to colonial-founded practices like extracting knowledge without any reciprocity or benefit to the community in improving their health outcomes.

Both Indigenous and non-Indigenous team members are involved in decisions related to data gathering, interpretation and sharing methods; however, given the history of the dominant western approach, care is taken to ensure that Indigenous knowledge is the reigning decision-maker in any instance. Sharing methods approaches create awareness and advocacy for others to do the same. Determining what can be shared is also at the discretion of the community. Research messages that use a strength versus a deficit-based approach are preferred to prevent further stigmatisation and create hope in communities and pride that their participation has had a meaningful outcome.

8. Gardening, Dissemination and Benefit of Interpretations: Our data or no data, inclusion, return to the community

Dissemination is part of the overall knowledge translation process that is integrated throughout the research. Knowledge development is continuous and fluid throughout the project to align with L’nuwey perspectives, which is accepted as part of the research cycle. It is understood that L’nuwey knowledge building is continuous in the community; there is no start or finish, it is part of a continuum since time immemorial. It is part of the researcher’s responsibility to know that a research project is integrating into an existing process of L’nuwey “knowledging” of that community. The dissemination process of that knowledge is also occurring at varying levels throughout the research project. For example, the knowledge that is shared during the interviews or through storytelling is already transmitting between the Elders and L’nu researchers spoken in the first language – l’nuisuti (in the Mi’kmaw language). It may be agreed that specific knowledge is not to be shared broadly. This was the case in one of the projects whereby the Elder shared their knowledge in our language and instructed us that the knowledge is only for us as L’nu researchers of Indigenous health research. The dissemination of that knowledge was gifted to the next generation and maintained in oral tradition. It will not be published outside of the conversation we had with the Elder, but gardening happened.

Then, there is knowledge shared during the validation process, which may also be in the first language. During either stage, it is determined what will be disseminated to the broader audience. That process is negotiated through ongoing communication between the Elders, Co-PIs, Knowledge Holders, and researchers. It would be dependent on the objectives and goals of the research.

The knowledge dissemination may further enhance the L’nuwey perspective that directly impacts the community, or there may be knowledge from the integration of both perspectives that strengthens either perspective individually or collectively through E/TES. It is a phase of knowledge that converges with western knowledge at a given point in time, bringing a new understanding of a continuous knowledge-building process. Researchers from outside the community would learn from Indigenous Peoples’ lived experiences, rich with perspectives, voices, knowledge, and stories that complement the understanding from a western-perspective. It allows the non-L’nu researcher to learn a full new understanding of how L'nuk perceives a concept such as pain/hurt and its interconnected relation to well-being.

The reciprocity principle is a critical guiding tool as well, as are the protocols above. Dissemination is an accommodation of the knowledge into a western-based format used by the community partner. The dissemination objective is to revisit the goals set out by the research and, primarily, to revisit the community priorities to address their health matters and to come full circle in the E/TES process. Relationships between community, researchers, clinicians and government leaders are responsible for championing knowledge to impact health interactions and outcomes.

Evolving Outcomes and Gardening

The knowledge generated from ACHH’s work continues to surface and evolve. There are several outcomes with considerable importance because communities have identified their health priorities associated with addressing Indigenous children’s pain issues. For example, findings have provided community-based evidence about pain occurrences in First Nations youth [Citation19]. As a result, communities have been able to advocate for resources, such as funding to buy hearing test equipment, which has led to earlier screening and treatment processes for preschool-aged children. Also, an app (www.kidshurtapp.com) to assist youth in conveying their emotional and physical pain and hurt to clinicians has been developed and pilot-tested with Indigenous youth. Knowledge gathered continues to be translated, or “gardened” [Citation14], into training content and curricula for post-secondary health sciences students and online learning modules for Nova Scotia clinicians. Interwoven in this training are the Seven Sacred Teachings, which enhance the patient-engagement process [Citation16] and community recommendations into what non-Indigenous clinicians should know about Indigenous patients. Some of those community recommendations are shared in manuscript currently under review [34] and in the short CPN ACHH documentary titled “Shift Ground through Art: Safe Approaches to Share & Manage Pain ” https://youtu.be/C8KMb_9TNcM. The most important outcome is the mobilisation of key health and wellness information and tools, improving the early health care experiences of Indigenous children and youth. The hope is that early investment in knowledge sharing and resources will reduce adverse health outcomes and improve Indigenous children’s and youth’s overall well-being in pain-related care and quality of life.

Summary

ACHH successfully built concrete research partnerships with First Nations communities initially in the Maritime Provinces and, with CPN support, a national expansion with several other provinces. Since 2009, the partnership between Eskasoni and IWK Health/ACHH has evolved from a partnership into a fellowship, almost kinship-like due to its success in establishing a sustainable relationship through continuous community engagement throughout all research projects. Knowing each other’s limitations and strengths, foundations of mutual respect, and partners as equals has resulted in a meaningful relationship between all the participants involved in the projects. High-quality capacity development for the Principal Investigators and the community-based researchers align with the project’s overall goals of a reciprocal, mutually benefiting relationship and outcome.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the contributions and involvement of the Chronic Pain Network (CPN) Indigenous Health Research Advisory Committee.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Young T. L’nuwita’simk: a Foundational Worldview for a L’nuwey Justice System. Indig Law J. 2016;13(1)

- Bartlett C, Marshall M, Marshall A. Two-Eyed Seeing and other lessons learned within a co-learning journey of bringing together indigenous and mainstream knowledge and ways of knowing. J Environ Stud Sci. 2012;2(4):331–11.

- Battiste M (2002). Indigenous Knowledge and Pedagogy in First Nations Education: a Literature Review with Recommendations. https://www.afn.ca/uploads/files/education/24._2002_oct_marie_battiste_indigenousknowledgeandpedagogy_lit_review_for_min_working_group.pdf

- Battiste M. Maintaining Aboriginal Identity, Language, and Culture in Modern Society. In: Battiste M (Ed.) Reclaiming Indigenous Voice and Vision. Vancouver: UBC Press; 2000. p. 192-208.

- Hyett S, Marjerrison S, Gabel C. Improving health research among Indigenous Peoples in Canada. Can Med Assoc J. 2018;190(20):E616.

- Anderson M. Indigenous health research and reconciliation. Can Med Assoc J. 2019;191(34):E930.

- Allen L, Hatala A, Ijaz S, et al. Indigenous-led health care partnerships in Canada. Can Med Assoc J. 2020;192(9):E208–E216.

- Forbes A, Ritchie S, Walker J, et al. Applications of Two-Eyed Seeing in primary research focuses on Indigenous health: a scoping review. Int J Qual Methods. 2020;19:160940692092911.

- Wright A, Gabel C, Ballantyne M, et al. Using Two-Eyed Seeing in research with Indigenous people: an integrative review. Int J Qual Methods. 2019;18. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406919869695.

- Truth & Reconciliation Commission of Canada. (2015). Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada: calls to action. Winnipeg. http://trc.ca/assets/pdf/Calls_to_Action_English2.pdf

- UN General Assembly (2007). United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. https://www.un.org/esa/socdev/unpfii/documents/DRIPS_en.pdf

- Hatcher A, Bartlett C, Marshall A, et al. Two-Eyed Seeing in the classroom environment: concepts, approaches, and challenges. Can. J. Sci. Math. Technol. Educ.. 2009;9(3):141–153.

- Iwama M, Marshall M, Marshall A, et al. Two-Eyed Seeing and the language of healing in community-based research. 2010;32:3–23. Canadian Journal of Native Education.

- Marshall A, Bartlett C (2018) Two-Eyed Seeing for Knowledge Gardening. In: Peters M (editor) Encyclopedia of Educational Philosophy and Theory. Singapore: Springer. p. 1-7. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-287-532-7_638-1

- Atlantic Policy Congress of First Nations Chief Secretariat. (2011). APCFNC Elders Project: honouring traditional knowledge 2009-2011. https://www.apcfnc.ca/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/FinalReport-HonouringTraditionalKnowledge_1.pdf

- Sylliboy JR, Hovey R. Humanizing Indigenous peoples’ engagement in health care. Can Med Assoc J. 2020;192(3):E70–E72.

- Sylliboy JR, Latimer M, Kehoe S (2019). Chronic Pain Network: indigenous health research survey results. https://achh.ca/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/IHRAC-Report-_Sept-23-2020.pdf

- Hovey RB, Delormier T, McComber AM, et al. Enhancing Indigenous health promotion research through Two-Eyed Seeing: a hermeneutic relational process. Qual Health Res. 2017;27(9):1278–1287.

- Latimer M, Rudderham S, Lethbridge L, et al. Occurrence of and referral to specialists for pain-related diagnoses in First Nations and non–First Nations children and youth. Can Med Assoc J. 2018;190(49):49.

- Latimer M, Finley GA, Rudderham S, et al. Expression of pain in Mi’kmaq children from one Atlantic Canadian community: a qualitative study. CMAJ Open. 2014;2(3):E133–E138.

- Castleden H, Morgan VS, Lamb C. “I spent the first year drinking tea”: exploring Canadian university researchers’ perspectives on community-based participatory research involving Indigenous peoples. Can Geogr. 2012;56(2):160–179.

- Kilian A, Fellows TK, Giroux R, et al. Exploring the approaches of non-Indigenous researchers to Indigenous research: a qualitative study. CMAJ Open. 2019;7(3):E504–E509.

- Tilley SA. Doing respectful research: power, privilege and passion. Winnipeg: Fernwood Publishing; 2016.

- Robinson M. Mi’kmaw Stories in Research. In: Battiste DM, editor. Visioning a Mi’kmaw Humanities. Halifax: Cape Breton University Press; 2016. p. 56–68.

- Kovach (2019). Conversational method in Indigenous research. First Peoples Child & Family Review, 14(1): 123–136

- Government of Canada (2018).TCPS 2 (2018) – chapter 9: research involving the First Nations, Inuit and Métis Peoples of Canada. https://ethics.gc.ca/eng/tcps2-eptc2_2018_chapter9-chapitre9.html

- First Nations Information Governance Centre (2020). The First Nations Principles of OCAP®. https://fnigc.ca/ocap

- MEW (2020). Mi’kmaw Ethics Watch. Cape Breton University. https://www.cbu.ca/indigenous-affairs/mikmaw-ethics-watch/

- Ermine W. The ethical space of engagement. Indig Law J. 2007;6(1):193–203.

- Battiste M, Sa’ke’j Y-HJ. Protecting Indigenous Knowledge and Heritage: a Global Challenge. Saskatoon: Purich Publishing Ltd; 2000. ( ISBN: 1-895830-15–X).

- CIHR (2015). Institute of Aboriginal Peoples’ Health Science Plan 2014–2018. Wellness, Strength,Resilience of First Nations, Inuit and Metis Peoples: moving Beyond Health Equity. ISBN: 970-0-660-02257-4. https://cihr-irsc.gc.ca/e/documents/iaph_strat_plan_2014-18-en.pdf

- Nicholas G. It’s taken thousands of years, but Western science is finally catching up to Traditional Knowledge. Conversation. 2018. https://theconversation.com/its-taken-thousands-of-years-but-western-science-is-finally-catching-up-to-traditional-knowledge-90291

- VanEvery R, Latimer M, Naveau A. Strategies for First Nation Youth to Develop Connections, Balance Health and Reduce Pain: LISTEN approach for Clinicians to Support Youth. First Peoples Child & Family Review. [Under Review]. 2021.