ABSTRACT

In a project aiming to develop community-led resources for families in northern Quebec, Canada, members (Inuit and non-Inuit) of the project decided to meet with Inuit parents to hear their experiences and needs, and to better understand how family dynamics might be related to ways of using resources within communities. In this article, we present secondary analyses of interviews conducted in 2015 with 14 parents living in a community of Nunavik, northern Quebec, accompanied by participatory analysis sessions. A dual data analysis strategy was adopted. Non-Inuit researchers and research assistants with significant lived experience in Nunavik explored what they learned from the stories that Inuit parents shared with them through the interviews and through informal exchanges. Inuit partners then discussed the large themes identified by the research team to guide non-Inuit researchers in their analysis. The aim was to better inform non-Inuit service providers and people whose mandate it is to support community mobilisation in relation to the heterogeneous realities of Inuit families, and the ways in which they can be of support to families based on their specific realities and needs.

Introduction

In this article we were interested in developing a better understanding of the ways in which Inuit parents of northern Canada interact with existing local resources, and how both the family dynamics, and the community social determinants of health influence the use of existing resources. Resources may include more structured services such as daycares, health services, community programmes for families, church activities or more informal and flexible resources such as kin that offer help, or spontaneous community activities. Parents navigate these resources and assess the impact of the resources on themselves, their family, and their environment, and then adjust their actions in relation to these resources according to their comprehensive assessment [Citation1–4]. Parents have agency with regard to the decisions and actions that they take, including which resources they might use or not use. However, their agency is influenced by the social and historical contexts in which they live [Citation1,Citation2,Citation5].

The social determinants model of health and wellness emphasises the importance of considering the complex inter-relationships between social policies, community environments, family life, and individual wellness when attempting to understand a phenomenon [Citation6] such as the one we explore in this study: use of local resources. Existing literature explores how community level social determinants of health influence the manner in which parents interact with resources in their community [Citation7–10]. For example, parents who live in socio-economically deprived environments might try to isolate from their community as a way of protecting themselves and their family members (or family dynamic) from difficult social environments [Citation11]. The way in which families navigate resources in their environment is not homogenous and may depend on their family dynamics and needs. Understanding these heterogeneities allows for a better adaptation of resources to meet the specific needs.

In this study, we conducted a secondary analysis of fourteen interviews and held various brainstorming sessions with community partners. The goal is to better understand how people who work for and design local resources can support families in their use and participation of resources based on their distinct realities and needs.

Social determinants of health

Social determinants of health are defined as the circumstances in which individuals are born, grow up, live, work, and grow old [Citation12–15]. Social determinants include all the resources put in place around the individual and collectivity that influence their health and wellbeing [Citation14–16]. They directly influence behaviours such as use of resources. The literature highlights a variety of factors that hinder both the pro-active reaching-out to resources and the ongoing contribution to resource design among Indigenous peoples [Citation17–21]. Lack of trust in existing services, language barriers, and other communication difficulties among professionals working for the resources, as well as a lack of cultural fit between perceived needs and resource mandates, and experiences of discrimination are but a few of the factors that influence use of services [Citation22–24].

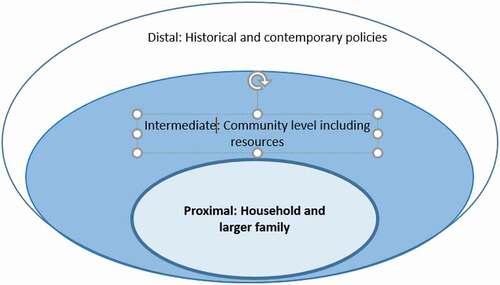

Indigenous peoples’ health and wellbeing, and the way in which they interact with resources is influenced by distal determinants (historical, political, social, and economical), intermediate determinants (community infrastructure, resources, systems) and proximal determinants (health behaviours, immediate physical and social environments such as household and family) [Citation6, Citation25–28].

Diagram 1: Simplified Social Determinants of Health model

These various determinants are inter-related. In this section we describe certain determinants that may influence families of Nunavik in a variety of ways [Citation29–32].

Brief historical background of existing resources

Nunavik is the Northernmost region of the province of Québec and home to approximately 13,000 Inuit. Nunavik covers a third of Quebec’s territory. Ninety percent of the population is Inuit. The region includes 14 villages with populations varying between 300 and 3000 individuals.

Traditionally, Inuit lived nomadic lives. They lived with their kin, generally in groups of approximately 20 people [Citation33, Citation34]. In the early 20th Century, these kinship networks were threatened by famine, as well as epidemics of smallpox and tuberculosis brought by settlers [Citation35–37]. In the 1950s, school became mandatory in the region and many children were removed from their families to be placed within residential schools [Citation38–42] or federal day schools Within the same historical period, individuals presenting symptoms of tuberculosis were sent for treatment for months or years to urban centres where they had little, if any, contact with family [Citation35]. Between the 1950’s and 70’s the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) undertook an extensive slaughter of sled-dogs, significantly reducing people’s ability to go on the land and independently feed their families [Citation43,Citation44]. Indeed, until then, men were often active hunters providing for their families with nutritious foods from the land. Hunting was an intricate component of personal and social identity. Being on the land was a source of health and healing. These policies, compounded by the experienced famine significantly threatened peoples livelihoods and so, families slowly started transitioning to more sedentary community lives close to schools, government facilities, and housing [Citation34,Citation45].

Considering the aforementioned events and the impact on Inuit communities, it is clear that the communities are a creation of colonisation and can not be understood outside of this specific context [Citation46]. The concept of community was once synonymous to family. Today the relationship between family and community is complex. Communities generally include multiple large families that are all inter-connected by blood, marriage, adoption, and other kinship relations (RCAP, 1996) [Citation41]. The multiplicity of relations creates `high social ties`: social relationships that are high in proximity and intensity [Citation47]. This can be particularly difficult in small communities. Families can become highly dependent on one another, which can create tensions and complex dynamics, especially when social determinants of health and wellbeing within the community are precarious. Contemporary inequities also impact the social contexts within which households, families, and communities must live. Major health inequalities in Northern Canada include lack of housing, unhealthy living conditions within homes, high cost of food, lack of stimulating employment, lack of educational opportunities and lack of culturally-based health and social services. Approximately 85–90% of the population now lives in social housing units attributed according to a point system [Citation48]. The amount of housing units has chronically been insufficient to respond to the demand. In 2014, Kativik Municipal Housing Bureau reported that Nunavik needed 899 more housing units in order to meet population needs [Citation48]. According to Statistics Canada [Citation49], half of Inuit living in the Inuit Nunangat live in overcrowded homes as compared to 5% within the general Canadian population [Citation50] based on the Canadian National Occupancy Standard. With high rates of placements of youth, yearly evictions of people who have not paid rent, return of community members from urban centres to their Nunavik community, and general lack of housing, people may choose to offer housing to children, guests, extended family members or other community members for days, weeks or months. This can exacerbate overcrowding and complex household dynamics. Households may include individuals who are not considered as being part of the family, and certain family members may not live within the household. Where community and family were traditionally one and the same, today the ways in which community, family and households are understood and defined may differ from person to person.

In a context where many resources made available within communities are created by colonial forces that are embedded within this colonial history; in a context where communities are still relatively small but where people hold multiple and complex relationships with one another; we wondered how parents choose to use, and participate in, the resources that are available to them within their community. Knowledge concerning relationships between household dynamics and use of available services would allow community members, service providers and policy makers to reflect on ways of contextually adapting services and practices based on the specific experiences and needs of a given family.

Methodology

Data collection

This secondary data analysis is part of a large action research on community mobilisation for family wellbeing requested by Nunavimmiut (people of the land) leaders [Citation51]. In the initial stages of the project, a regional Inuit project coordinator from Nunavik was selected by regional leaders, and asked to work with the principal investigator (first author). Together they conducted informal interviews with key informants to identify potential community representatives to lead the community project. A five-member local advisory board was then formed. Their initial role was to act as local decision-makers for the project, to initiate community mobilisation with the support of partners, and to ensure that the research process was sensitive to community needs and realities. Meetings were held between the regional coordinator, the PI (first author) and the advisory board members (including third author) both in person and by phone. The advisory board members suggested that individual interviews take place with families with diverse socio-economic profiles to better understand the wide array of needs and experiences.

Once the principal investigator proposed a draft of interview questions, the advisory board refined these questions and chose recruitment methods. Questions focused on family and community needs and resources, as well as turning points in family lives. The research protocol was submitted and approved by the Université de Montréal ethics committee.

Recruitment

The first phase of recruitment for interviews took place by radio, an essential and ubiquitous communication method in each village in Nunavik. Over community radio, Inuit partners and the principal researcher explained the nature of the study and invited those who were interested to call a local research coordinator to set up a meeting. The invitation was made to anyone who identified as parents, no matter their age. Nine parents responded to the radio announcement. In a second phase, and to ensure a diversity of participants, the local coordinator then personally invited five individuals who would represent different family realities than those presented by the 9 families initially interviewed. A total of 14 parents participated in the interviews: Two grandmothers (aged 55 to 70, one of whom had young children in her care, the other living with her children who were now adults), eleven mothers (aged 20–45) and one father in his thirties. One third of participants had stable full-time middle-to-high income positions within the community, one third had part-time contracts in low-income positions such as janitor or cashier, and the other third had no employment at the time of the interview.

Interviews were conducted in English or Inuktitut (with an interpreter), lasted approximately 45 minutes, and took place in a private room in the local government municipal building. Verbal consent was obtained. Participants were invited to respond only to questions they felt comfortable answering and were told they could end the interview at any time. Participants were offered 50 dollars for their contributions to the study.

During the interviews, participants were introduced to the study and its purpose: To better understand the needs and wishes of families within the community to support a community advisory board in the development of a community organisation for families. The participants were then reminded about confidentiality and the possibility of ending the interview at any time. Participants were asked if they had heard about the initiative of the advisory board and how they felt about it. They were asked to describe some of the challenges families in the community were experiencing, and how they felt these issues could be addressed. After a more general discussion on families within the community, we asked participants to describe their own families. They were then asked to specify who lived in their household (whether it be family or not). They were asked to describe a typical day at their home, and some of the stressors they might experience in their household. They were asked how they dealt with stress, who they might reach out to, and what resources they used in their community. Finally, they were asked to describe their experience with these resources, and what they would like to see improved to better support their household and their family.

It is important to note that for the interviews and analyses, the concept of `family` and of `community` were not pre-defined for participants. This was done to ensure that participants be able to share their knowledge and experience based on their own conceptualisation and experience of family and community.

Conceptual framework

Systems sciences in general conceptualise relationships between a multitude of variables or individuals, to illustrate the `big picture` of how various parts of a system are interrelated [Citation52]. People are part of webs of relations and resources that influence our actions and the meaning these actions will take on [Citation53]. These webs are also constantly changing. However, it is possible to circumscribe sets of networks such as “the family” or “the community” or `local resources` to analyse what they are comprised of, and how they are connected within a given time, as they do tend to present certain stable characteristics in given time frames [Citation53]. Using these levels of analysis we are not interested in identifying social determinants of health as we have done in a previous publication [Citation54]. Here, we explore how family level realities impact upon the interactions with the proximal determinants of health and vice versa, while remaining aware that these relations are also circumscribed within distal determinants of health.

Data analysis

For the primary analysis [Citation54], interviews were transcribed, and a thematic inductive analysis was conducted using QDA miner software [Citation55]. Each interview was read by the PI and a doctoral student. Four non-Inuit research assistants wrote a brief resume of the interviews that they had transcribed and added their thoughts and reflections to this text. These six people then regrouped with two additional non-indigenous observers who had previously worked with Northern communities to discuss the themes that had emerged from the first level of analysis. A major component of our discussion was around the malaise of reading and reflecting about the stories and realities of Indigenous peoples, when we are non-indigenous, and well aware of the long standing power dynamics in research where non-indigenous peoples have studied and extracted knowledge from indigenous communities. This bias was discussed with Inuit partners who felt that as long as it was being done in a space of care and in dialogue with community, it was appropriate and helpful. This remains an ongoing discussion with partners and among non-indigenous students who are invited to reflect on their positioning, roles, and privileges in our research team.

A total of four broad themes were identified, including family constitution, conflict and communication ruptures among family members, family cohesion, and experience with community level social determinants of wellbeing (both community stressors and resources). Seven participants spoke of two distinct time periods marked by a significant change in family structure, (for example a break-up or children who grew-up and left home). For the secondary analysis of this study, a conceptual map [Citation56] was created for each of these family time-periods based on the four broad themes as defined by participants. Then, during an analysis workshop, three researchers (including author 1 and 2) sorted the maps based on observed characteristics to explore emerging patterns of family experiences. A total of four large patterns of family experiences were identified based on four broad emerging characteristics: inter-family relations, family/community boundaries, exposure to stressors, and engagement with resources.

The principal investigator went to the community advisory board and invited feedback. Multiple discussions were held to validate the results and reflect on their pertinence. The discussions allowed us to organise findings around four family portraits that can be placed on two inter-related continuums as described below.

Concerned about knowledge mobilisation and how the information can be understood and used by the readers [Citation57], we discussed modes of data communication. The advisory board chose to use storytelling as a means through which to communicate research findings. They, alongside the principal researcher, engaged in a series of discussions both in person and by phone to choose the key elements of this story. These were compiled in narrative form by the principal researcher. The third and fourth authors, two Inuk partners, were chosen to continue helping the author with the manuscript. Based on these discussions and ethnographic field notes, we then developed short vignettes as a mode of knowledge mobilisation. They have been found to be critical pedagogical tools when working around complex issues, especially in the field of intercultural social worker and education disciplines [Citation58–60][Citation61–62]. Vignettes have also been used previously in Indigenous research. The vignettes are amalgamations of stories and realities that were shared by participants during interviews but they do not represent a specific individual. They are meant to represent the different patterns observed in data analysis. They are not meant as an exhaustive account of possible arrangements, but rather as illustrations of how family dynamics can influence one’s engagement with resources, and vice-versa.

Results

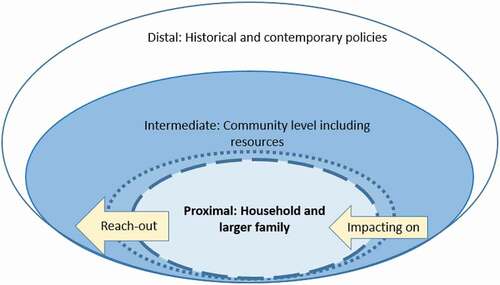

As described above, the family narratives can be organised into four portraits that describe two dynamics: 1) the degree to which community stressors impact the household (or family) 2) the degree to which the household (or family) reaches-out to the available community resources. Each of these dynamics illustrates the permeability of the boundaries between the household and the community. As will be seen below, the permeability of these boundaries between a community and a household, or a household and use of services is influenced both by internal family realities and by social determinants of health.

Diagram 2: Conceptual framework based on the social determinants model where household and families adjust to the household-community boundaries based on community determinants of health, and the degree of reach-out to existing services based on family and community realities.

Diagram 2: Conceptual framework based on the social determinants model where household and families adjust to the household-community boundaries based on community determinants of health, and the degree of reach-out to existing services based on family and community realities

The following offers fictive examples to illustrate four scenarios.

Family portraits

Portrait one

Ani is 55. She lives with her mother (70), nephew Johnny (35) and his child (10). Ani originally accepted to have her nephew stay with her when he returned from jail and did not have a place to stay. At the time of the interview no one in the household has a paying job. They are having difficulty paying for rent and food. Friends of Ani’s nephew have been coming by more and more, often inebriated. Although Johnny had been sober for a few months, the ongoing presence of his friends seems to have made it more difficult for Johnny to stop drinking. Last week when Ani asked Johnny to not enter the home after drinking, he hit Ani’s mother. Ani is worried that if she contacts the police the young child might be taken under youth protection services. She therefore stays at home and does not tell anyone about the difficulties.

In the first family context, participants identified specific individuals that were part of their family system. They explained that these individuals were generally limited to people living within a household at the time of the interview. The participants described their family relationships as being marked by situations of violence or substance abuse. Community level challenges were highly present within the description of their households: Lack of jobs, food insecurity, community bullying, and lack of housing. Relationships within the household were often very strained. They described that certain individuals were quite dependent on one another, and attempted to help each other through very difficult family situations. Other relationships within the same household were described by participants as being ruptured or disconnected, with certain individuals not speaking to each other despite living under the same roof. People who described these family systems only spoke of using resources in times of crises. A reticence for calling upon institutional services, including police and youth protection, was expressed, as there was fear of how these services might step in. Participants described different inhibitors to using resources such as feeling that services would not be able to create the changes they would want to see in their household, fearing the consequences of receiving services, and language barriers. In this family portrait, community stressors enter the family realm, but the family is mostly closed to support from external resources.

Portrait two

Amy (22) and Brian (28) are young parents of three children aged 1, 3 and 5. They live with Brian’s mother as they have not yet been given a home in the community. Amy started working at the Coop (local store), but Brian lost his job a few months ago working at the community garage. Amy and Brian often fight about the children, and money issues. Recently youth protection services got involved after a violent fight between Amy and Brian. Since then, Amy goes to the CLSC sporadically to speak with the local social worker. She also started going to the community kitchen activity with her eldest daughter.

Among parents describing this second family portrait, participants generally described relationships with close family members (partners and children) who mostly lived in the household. Household relations were marked by both hardship and optimism. These participants spoke of reaching out to resources within the community, including institutional services (nurse, psychiatrist, social worker), elders, church, going on the land. They spoke of consciously wanting to create change in their personal and family dynamics. Some participants spoke of meeting with the fly-in psychiatrist for a consultation, going to meet with a community elder for counsel, or going out on the land camping. On the one hand they described a certain hope that they were in a process of healing with the support of available resources. On the other hand, they described fear of rumours, judgment, and potential consequences of talking to service providers, such as having children taken out of home by youth protection services or police getting involved. Thinking about participating in community development was an exciting thought for these participants, however, life stresses were described as too important to engage in ongoing community work at the current moment. In this second family portrait the family attempts to close and protect itself from community stressors and show a certain outreach to resources in the community.

Portrait three

Jordan and Lea have three children and 2 grandchildren. After 10 years of important difficulties within their couple they have found a certain stability. They both have well paying jobs. They are highly invested in the wellbeing of their grandchildren. They do activities with them at home so that their grandchildren do not spend too much time lingering in the community, as they are concerned about community bullying and exposure to drugs. They partake in community activities but limit their involvement. They are highly aware of the difficulties that their neighbours are experiencing and wish to help, however, they also know that if they start supporting the neighbours by offering food or a helping ear, they risk coming in more and more often to eat and talk. This means less time to unwind after long days, less time to talk things over with their spouse, and less time to be with the grandchildren. They are worried of things going back to how they were before and want to protect the stability they have slowly developed as a family.

In this third system, family members as described by participants were specific individuals who almost exclusively represented immediate kinship, generally two parents and two to three children. The relationships between these individuals were generally described positively, and were perceived as manageable family difficulties. These difficulties were experienced as challenges that could help strengthen family bonds. Participants actively engaged in external relationships with formal and informal resources including parents, friends, nursing station, cultural activities. When a certain form of resource was seen as inadequate or insufficient for themselves or a family member, participants described having to take on extra responsibilities to care for oneself and others. However, this “self as support” was generally described as something positive and empowering despite the frustration of not having access to the proper service within the community. The social inequities experienced in the community and generated by colonisation and ongoing policies and practices, were part of participant’s narratives. Participants described mechanisms that they would at times use to reduce the impact of these social determinants on family well-being. Participants describing this reality also spoke of other periods in their family life where they felt they had less control over how these social determinants might affect family life. In this family portrait, techniques include establishing strong boundaries in relationships to others in their community. They actively use resources that are available in the community.

Portrait Four

Evie lives with her husband and whomever from the community might need a place to stay at a given time. This currently includes her son, a friend who recently left her husband, a person who was evicted from his home for not paying rent and her 2 grandchildren. Evie prepares food every day for those who might come visit. This might include neighbours or community members who are going through a difficult period and are looking for a helpful ear, or some food. She enjoys supporting others, however, with the number of people living in her home, and people constantly coming-in and out, she doesn’t feel she has any space to relax when she feels overwhelmed. She generally does not sleep well and has moments when she feels sad and angry. Sometimes leaving town is the only way to take a break.

In the fourth family system, the entities constituting the family were very difficult to establish. Indeed, when asked “who is family”, participants enumerated several individuals, and as the interview continued, new members were added. One participant said: “I guess family is ‘’who you help”. The boundaries between household members, family members and community were highly permeable. Participants who described this family system generally did not speak of engaging in external resources for themselves, however, they engaged heavily in relationships with community members, and community services for other members of the community (ex: the elderly, the bereaved, the incarcerated, the sick). As with many participants, those who described such family arrangements identified themselves as sources of support. However, in these situations, participants described this as being overwhelming. They consistently spoke of community dependency, people being dependent on them and having the feeling of not being able to help people as they wished they could. This was a consequence of the lack of services available within the communities. Participants described multiple social determinants that directly affected family life. They spoke of taking in children under youth protection, guests, and community members in difficult situations. In this family portrait the boundaries between community and family are very porous they do not use the services so much for themselves but look to create connections between services and community members in need. They themselves are important community resources for other families.

Discussion

This qualitative research aimed at exploring the multidirectional association between proximal and intermediate determinants of health, more specifically the household or family dynamics and the available local resources within a community of Nunavik. Households, families, and communities are not necessarily distinct entities. Traditionally, they were one. Today, feelings about kinship and community may be more heterogeneous and complex, and may be influenced by the need to protect oneself from intermediate social determinants of health, exacerbated by the legacy of colonisation and ongoing social inequalities. As can be observed within the vignettes, families cope with a variety of distal, intermediate, and proximal determinants that influence how they feel, how they interact socially and how they reach-out to available resources. We argue that people’s use of and interaction with resources (either as a user, a provider, or a mobiliser) depends on a variety of known factors such as availability, accessibility, cultural safety, trust in the service, experiences of discrimination within the resources but also depends on the walls that families place around themselves as a mode of protection from social determinants [Citation63].

Indeed, the various narratives shared through the interviews and informal exchanges suggest that at a given time, people experience and cope with community level social determinants of health in distinct ways. This household-community pattern can be placed on a continuum of permeability to external stressors (see dotted circle between the household and the community in diagram 2). Two household-community patterns are more permeable to community stressors, the first being those with high household conflicts where community stressors infiltrated the household boundaries, and the second being the families actively offering intensive support to community members.

One household-community pattern showed an attempt to slowly close the household-community boundaries gap by, for example, seeing certain groups of friends less often, or having children stay at home rather than spend time in community spaces. They tended to do so after a crisis, such as a child being signalled to youth protection services.

Finally, one household-community pattern was more impermeable to strenuous community level social determinants and explicitly spoke of strategies to enforce community-household boundaries as a way of living that would reduce exposure to community stressors. Examples of strategies include not committing oneself to community mobilisation efforts, not allowing children to roam in the community, not participating in community events. In these situations, people living in the household were all described as family members and immediate family was limited to those living in the household. That being said, grandparents living outside of the household were described as important family members.

The strategies used to cut oneself off from community stressors are consistent with literature on social networks in small communities, which suggests that although high social capital is related to improved health within the general population (Kawachi & Berkman, Citation47), within smaller communities [Citation64], and specifically northern communities [Citation65–66], being highly connected to others came at a cost for wellbeing (social networks theories and community stressors, Citation64) [2, p.92]. When expectations and social performance are high and the needs are great, people can “therapeutically withdraw” from these social networks as a means of reducing stress.

Knowing that community social determinants influence families in different ways, and knowing that families adopt different strategies over time as to protect family and community, we then explored how these household-community dynamics can influence interactions with resources, either for personal wellbeing or for collective wellbeing. Here, we were interested in interactions with a variety of resources, including institutionalised (formal) services or community (informal) resources. We found that the four household-community patterns differed tremendously in the type and level of engagement with resources, whether it be help-seeking engagement or engaging in the planning and offering of resources. These four patterns could also be placed on a continuum, one that describes level of reach-out or engagement with resources (institutional and community) from low-level to high-level engagement.

The families experiencing the highest and most pervasive household conflicts were those who spoke least of using available resources. Despite being seemingly most in need, households with internal family conflicts seemed to inhibit the use of support systems, creating a clear cut-off between the household and community resources in their narratives. Individuals experiencing these difficulties spoke of concrete actions that could support their use of services, such as ensuring care is available in their mother tongue, having care come directly to their home, or having workers show a high level of pro-activity and empathy in their care [Citation63].

The second household-community pattern showed greater use of and interaction with institutional resources, including psychiatry and social services. They also engaged with community resources such as community elders and extended family. Certain people outside of the household were identified as family. However, reach-out, or engagement with community and family resources was not consistent.

The third household-community pattern engaged with a variety of resources and described the presence of family members and other informal support systems outside of the household. They spoke of eventually wanting to integrate community mobilisation and to be more present for community members, but felt unready to initiate such actions due to the potential threat it could bring to household dynamics. They spoke of an important feeling of guilt that loomed over them as they attempted to limit their interactions with certain community members or community events.

The fourth household-community pattern engaged less with resources for themselves and more for other community members. They were highly engaged in community mobilisation events and in the creation of community led resources. Their openness to community also came at a cost. They felt that their efforts never seemed to be enough to support the community, which led to moments of disempowerment, feeling burnt-out and alone. Their family was difficult to describe, as was their household which could change frequently with new guests staying in the home. A participant explained: Family is who you can help, resonating with the notion that community and family may be one.

In our ethnographic work, partners have often expressed the feeling that Inuit are losing their culture, not sharing as they used to, not opening their homes to others as they might have before. [Citation67],describes how traditionally, Inuit of northern Canada (more specifically the region of Nunavut) relied heavily on kinship for survival and wellbeing, as is still the case in many ways today. As described above, traditional kinship may have included 10–30 individuals prior to settlement. With colonial practices and policies, Inuit became largely sedentary, living in communities that are now comprised of 300 to 3000 individuals with numerous inter-related families. People must negotiate numerous layers of systems with different needs and dynamics. Families therefore must renegotiate membership as well as their interactions with community in a way that supports household members’ wellbeing, extended family members, neighbours, and community, all in a in a post-colonial context of trauma and healing (distal determinants). Families who experienced trauma are trying to cope with past experiences, contemporary social determinants and are protecting their interpersonal ties. For some, this adaptation and period of healing means making emotionally complex decisions between protecting family or being there for the larger family (community), knowing the impact this can have on notions of kinship. Indeed, in order to be well, some have had to maintain harmony and balance by limiting demanding relationships with some community members.

The complexity of the choices people must make, and the calculations of the impacts of engagement or retraction demonstrate that distal and intermediate social determinants of health directly influence people’s exposure to stressors, the ways they cope with these stressors, and the way in which people define family and experience kinship relationships within communities.

Community members’ decision to engage with resources influences the individuals around them. As social bodies, our decisions impact upon different systems of individuals, creating multiple layers of considerations [Citation68]. Ultimately, one might ask themselves: do my actions have the potential of placing myself, my family members, or my community fellows at risk? As professionals, community workers, community developing agents, these are questions we must consider to respect the current abilities and availabilities of the people we work with.

Study strengths and limitations

First and foremost, the project and article, although collaborative and responding to community needs, was led by a non-Indigenous scholar who carries her own culture, ways of seeing the world, and of organising information. Scientific methods and articles also hold a certain culture. The `translation` of community life as experienced by individuals into data that is manipulated, organised, and written in a scholarly way transforms the lived experience, especially when written by a non-Indigenous scholar. The results were brought back to community members for validation and discussion, and Inuit read through and modified the way in which the article was written. Initially the results were written as a story representing animals with different needs and experiences coming together to learn from each other and transform their community together. This story was used as a promotional and explanatory story for the community mobilisation that was taking place. However, when the elements of the story were integrated within this scientific article, each element described separately, it gave an impression of simplification and dehumanisation of families’ stories. For the purpose of the article, we therefore decided to write vignettes that illustrate different experiences. Despite their input, we are aware that placing the experiences of individuals within an article’s style does not represent Inuit ways of communicating.

This qualitative study was conducted in a single community of Nunavik with a small number of people including one man. This limits the possibility of extrapolating from the data, especially regarding the experiences and needs of men. Interviews were approximately 1-hour long and in a single meeting, thus limiting the possibilities of developing a trusting relationship between the interviewer and the participants. Although the principal investigator had been in the community on four occasions prior to the interviews, the participants did not know her well and they may have limited their description of family experiences due to a lack of trust in the researcher. That having been said, many participants spoke of feeling more comfortable speaking with “an outsider” knowing that the risk of information being shared amongst community members was lower. Moreover, many participants spoke of their desire to share as much information as possible to support the larger process of developing community-based services.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Giddens A 1987. Social theory and modern sociology. Stanford University Press.

- Jack G. Ecological influences on parenting and child development. British J Social Work. Stanford, California. 2000;30(6):703–11.

- La Placa V, Corlyon J. Unpacking the relationship between parenting and poverty : theory, Evidence and Policy. Social Policy and Research. 2015;15(1):11–28.

- Leßmann O (2017). Capability, collectivities and participatory research. https://www.re-invest.eu/images/docs/reports/D4.1_IFZ.pdf

- Parsell C, Eggins E, Marston G. Human agency and social work research: a systematic search and synthesis of social work literature. Br J Soc Work. 2017;47(1):238–255.

- Reading, C. L., & Wien, F. (2009). Health inequalities and social determinants of Aboriginal peoples’ health (pp. 1-47). Prince George, BC: Canada National Collaborating Centre for Aboriginal Health.

- Bowes, L., Arseneault, L., Maughan, B., Taylor, A., Caspi, A., & Moffitt, T. E. (2009). School, neighborhood, and family factors are associated with children’s bullying involvement: A nationally representative longitudinal study. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 48(5), 545-553.

- Burton, L. M., Lichter, D. T., Baker, R. S., & Eason, J. M (2013). Inequality, family processes, and health in the “new” rural America. American Behavioral Scientist, 57, 1128-1151. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764213487348

- Coley, R. L., Kull, M., Leventhal, T., & Lynch, A. D. (2014). Profiles of housing and neighborhood contexts among low-income families: Links with children’s well-being. Cityscape, 16(1):37–60.

- Elgar, F. J., Craig, W., Boyce, W., Morgan, A., & Vella-Zarb, R (2009). Income inequality and school bullying: multilevel study of adolescents in 37 countries. Journal of Adolescent Health. 45(4):351–359.

- Burton, L. M & Jarrett, R.L. (2004). In the mix, yet on the margins: The place of families in urban neighborhood and child development research. Journal of Marriage and Family, 62, 1114–1135. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2000.01114.x

- Jones, C. P., Jones, C. Y., Perry, G. S., Barclay, G., & Jones, C. A. (2009). Addressing the social determinants of children’s health: a cliff analogy. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved, 20(4):1–12.

- Navarro V. (2009). What we mean by social determinants of health. International Journal of Health Services. 39(3):423–441.

- Satcher, D. (2010). Include a social determinants of health approach to reduce health inequities. Public Health Reports. 125(4_suppl):6–7.

- World Health Organization. (2010). A Conceptual Framework For Action On the Social Determinants of Health : Social Determinants of Health Discussion Paper 2. https://www.who.int/sdhconference/resources/ConceptualframeworkforactiononSDH_eng.pdf?ua=1

- Venkatapuram S. (2010). Global justice and the social determinants of health. Ethics & international affairs. 24(2):119–130.

- Horrill, T., McMillan, D. E., Schultz, A. S., & Thompson, G. (2018). Understanding access to healthcare among Indigenous peoples: A comparative analysis of biomedical and postcolonial perspectives. Nursing inquiry, 25(3),e12237.

- Marrone, S. (2007). Understanding barriers to health care: a review of disparities in health care services among indigenous populations. International Journal of Circumpolar Health, 66(3), 188–198

- McConkey, S. (2017). Indigenous access barriers to health care services in London, Ontario. University of Western Ontario Medical Journal. 86(2), 6–9.

- NCCIH. (2019). Access to health service as a social determinants of First Nations, Inuit and Métis health. Accessible at: https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=&ved=2ahUKEwja7t7W57vrAhWvmuAKHcSFANUQFjAAegQIAxAB&url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.nccih.ca%2Fdocs%2Fdeterminants%2FFS-AccessHealthServicesSDOH-2019-EN.pdf&usg=AOvVaw2X2QxAhMSkT-XBPV8iFsbF

- Nelson, S. E., & Wilson, K. (2018). Understanding barriers to health care access through cultural safety and ethical space: Indigenous people’s experiences in Prince George, Canada. Social Science & Medicine, 218, 21–27.

- Isaacs, A. N., Pyett, P., Oakley‐Browne, M. A., Gruis, H., & Waples‐Crowe, P. (2010). Barriers and facilitators to the utilization of adult mental health services by Australia’s Indigenous people: seeking a way forward. International journal of mental health nursing, 19(2):75–82.

- Price, M., & Dalgleish, J. (2013). Help-seeking among indigenous Australian adolescents: exploring attitudes, behaviours and barriers. Youth Studies Australia.32(1), 10.

- Turi, A. L., Bals, M., Skre, I. B., & Kvernmo, S. (2009). Health service use in indigenous Sami and non-indigenous youth in North Norway: a population based survey. BMC Public Health, 9(1):378.

- Gracey, M., & King, M (2009). Indigenous health part 1: determinants and disease patterns, The Lancet, 374(9683), 65–75

- Mabry, P. L., Olster, D. H., Morgan, G. D., & Abrams, D. B (2008). Interdisciplinarity and systems science to improve population health: a view from the NIH Office of Behavioral and Social Sciences Research. American journal of preventive medicine. 35(2):S211–S224.

- Raphael D. (Ed.). (2004). Social determinants of health: Canadian perspectives. Toronto: Canadian Scholars’ Press.

- Wilkinson, R. G., Marmot, M., & World Health Organization. (1998). Social determinants of health: the solid facts. (No. EUR/ICP/CHVD 03 09 01). Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe.

- Healey, G. K (2014). Inuit family understandings of sexual health and relationships in Nunavut. Canadian Journal of Public Health, 105(2), e133-e137.

- Kral, M. J., Idlout, L., Minore, J. B., Dyck, R. J., & Kirmayer, L. J. (2011). Unikkaartuit: meanings of well-being, unhappiness, health, and community change among Inuit in Nunavut, Canada. American journal of community psychology, 48(3-4), 426-438.

- Kirmayer, L., Simpson, C., & Cargo, M. (2003).Healing traditions: Culture, community and mental health promotion with Canadian Aboriginal peoples. Australasian Psychiatry, 11(sup1), S15-S23.

- Wilk, P., Maltby, A., & Cooke, M. (2017). Residential schools and the effects on Indigenous health and well-being in Canada—a scoping review. Public health reviews38(1), 8.

- Briggs, J. L. (1995). Vicissitudes of attachment: Nurturance and dependence in Canadian Inuit family relationships, old and new. Arctic Medical Research. 54,21–32.

- Pauktuutit Inuit Women of Canada. (2006). The Inuit way: A guide to Inuit culture. Pauktuutit Inuit Women of Canada.

- Duhaime, G. (1983). La sédentarisation au Nouveau-Québec inuit. Etudes/Inuit/Studies, 25–52.

- Grygier, P. S. (1997). A long way from home: The tuberculosis epidemic among the Inuit (Vol. 2). McGill-Queen’s Press-MQUP.

- Keenleyside, A. (1990). Euro-American whaling in the Canadian Arctic: Its effects on Eskimo health. Arctic anthropology, 1–19.

- Aboriginal Healing Foundation. (2008). From Truth to Reconciliation: Transforming the Legacy of Residential Schools. http://www.ahf.ca/downloads/from-truth-to-reconciliation-transforming-the-legacy-of-residential-schools.pdf

- McDonough, B. (2013). Le drame des pensionnats autochtones. Relations, (768), 33 35.

- Pauktuutit Inuit Women’s Association. (2007). Sivumuapallianiq (Journey forward): National Inuit Residential Schools Healing Strategy. Ottawa, ON: Pike, G.(2008). Citizenship education in global context. Brock Education Journal. 17(1):38–49.

- Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples. (1996). People to people, nation to nation: Highlights of the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples. Ottawa: Canada Communication Group.

- Tester, F., & Kulchyski, P. (1994). Tammarniit (mistakes): Inuit relocation in the eastern Arctic, 1939-63//Review. Arctic, 47(4), 415.

- Croteau, J-J. (2010). Rapport final de l’Honorable Jean-Jacques Croteau, juge retraité de la Cour supérieure relativement à son mandat d’examen des allégations d’abattage de chiens de traîneau inuits au Nunavik (1950-1970), Société Makivik.

- Lévesque, F. (2010). Le contrôle des chiens dans trois communautés du Nunavik au milieu du 20e siécle. Études/Inuit/Studies, 34(2), 149–166.

- Collings, P. (2005). Housing policy, aging, and life course construction in a Canadian Inuit community. Arctic Anthropology,42(2), 50–65.

- Czyzewski, K. (2011). Colonialism as a broader social determinant of health. International Indigenous Policy Journal, 2(1).

- Kawachi, I., & Berkman, L. F. (2001). Social ties and mental health. Journal of Urban health, 78, 458–467. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/jurban/78.3.458

- Société d’Habitation du Québec. (2014). Housing in Nunavik. http://www.habitation.gouv.qc.ca/fileadmin/internet/documents/English/logement__nunavik_2014.pdf

- Statistics Canada. (2018). The housing conditions of Aboriginal people in Canada. https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2016/as-sa/98-200-x/2016021/98-200-x2016021-eng.cfm

- Statistics Canada. (2016). Census Profile: Canada. https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2016/dp-pd/prof/details/page.cfm?Lang=E&Geo1=PR&Code1=01&Geo2=PR&Code2=01&Data=Count&SearchText=01&SearchType=Begins&SearchPR=01&B1=All&Custom=&TABID=3

- Fraser, S, Vrakas, G, Laliberté, A, Mickpegak, R. Everyday ethics of participation: a case study of a CBPR in Nunavik. Global Health Promotion. 2018; 25(1):82–90.

- Leischow, S. J., & Milstein, B. (2006). Systems thinking and modeling for public health practice. American Journal of Public Health, 96,403–405. doi:https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2005.082842

- Schatzki, T. R. (2002). The site of the social: A philosophical account of the constitution of social life and change. United States of America: Penn State Press.

- Fraser, S. L., Parent, V., & Dupéré, V. (2018). Communities being well for family well-being: Exploring the socio-ecological determinants of well-being in an Inuit community of Northern Quebec. Transcultural Psychiatry, 55, 120–146. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1363461517748814

- Guest, G., MacQueen, K. M., & Namey, E. E. (2011). Applied thematic analysis. United State of America: Sage.

- Wheeldon, J., & Faubert, J. (2009). Framing experience: Concept maps, mind maps, and data collection in qualitative research. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 8. 68–83. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/160940690900800307

- Fraser, S. L. (2017). What stories to tell? A trilogy of methods used for knowledge exchange in a community-based participatory research project. Action Research, 16(2):207–222.

- Hunter, P. (2012). Using Vignettes as self-reflexivity in narrative research of problematized history pedagogy. Policy Futures in Education https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2304/pfie.2012.10.1.90

- Seguin, C.A. & Ambrosio, A.L. (2009). Multicultural vignettes for teacher preparation. Multicultural perspectives. 4 (4) 10–16. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327892MCP0404_3

- Strausman, J.D. (2018). Complexity made simple: The value of brief vignettes as a pedagogical tool in public affairs education. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0144739418769464

- Blodgett, A, T., Schinke, RJ., Smith, B., Peltier, D. & Pheasant, C. (2011). In Indigenous Words: Exploring Vignettes as a Narrative Strategy for Presenting the Research Voices of Aboriginal Community Members. 17:522.

- Parker, R. (2003). The Indigenous Mental Health Work. Australasian Psychiatry.

- Fraser, S. L., & Nadeau, L. (2015). Experience and representations of health and social services in a community of Nunavik. Contemporary Nurse, 51, 286-300. Transcult Psychiatry. 2018;55(1):120–146. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/10376178.2016.1171728

- Belle, D. E. (1983). The impact of poverty on social networks and supports. Marriage & Family Review, 5; 89–103. https://doi.org/http://dx.doi.org/10.1300/J002v05n04_06

- Richmond, C., Elliott, S. J., Matthews, R., & Elliott, B. (2005). The political ecology of health: perceptions of environment, economy, health and well-being among ’Namgis First Nation. Health & place, 11, 349–365. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthplace.2004.04.003

- Richmond, C. A., & Ross, N. A. (2008). Social support, material circumstance and health behaviour: Influences on health in First Nation and Inuit communities of Canada. Social Science & Medicine, 67(9), 1423–1433.

- Tagalik, S. (2010). Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit: The role of Indigenous knowledge in supporting Wellness in Inuit communities in Nunavut. National Collaborating Center for Aboriginal Health. Retrieved from: https://www.ccnsa-nccah.ca/docs/health/FS-InuitQaujimajatuqangitWellnessNunavut-Tagalik-EN.pdf

- Sen, A. (1999). Development as freedom. New York: Oxford University Press, p85.