ABSTRACT

This nationwide cross-sectional study of the lifetime prevalence and determinants of suicide attempts includes 90% of Greenlandic forensic psychiatric patients. Retrospective data were collected from electronic patient files, court documents, and forensic psychiatric assessments using a coding form from a similar study. We used unpaired t-tests and chi2 or Fisher’s exact test. The lifetime prevalence of suicide attempts was 36% (n = 32), and no difference in prevalence was found between male and female patients (p = 0.95). Patients having attempted suicide had a higher rate of physical abuse in childhood (p = 0.04), family history of substance misuse (p = 0.007), and criminal convictions among family members (p = 0.03) than patients who had never attempted suicide. Women primarily used self-poisoning in their latest suicide attempts (67%), whereas men more often used sharp objects or a firearm (42%). Over a third of Greenlandic forensic patients have attempted suicide at some point in their life, and patients with traumatic childhood experiences are at higher risk of suicidal behaviour. It is not possible to conclude whether the lifetime prevalence of suicide attempts among Greenlandic forensic patients is comparable to that of other high-risk groups in other Arctic regions due to methodological differences among the very few other comparable studies.

Introduction

Worldwide, nearly 800,000 people die from suicide annually [Citation1], and Arctic communities experience some of the world’s highest suicide rates [Citation2]. In Greenland, around 10% of all deaths between 2000–2009 were caused by suicide [Citation3] and young men, in particular, are at an increased risk of dying by suicide. In fact, suicide rates in Greenland are over 4 times higher among men than women. Unlike suicide rates in Denmark, which increase with age for both sexes, the rate peaks among young Inuit men aged 15–24 [Citation4].

Suicidal behaviour, meaning any action that could cause a person to die, is a multifactorial phenomenon that occurs in interactions between sociological, psychological, and cultural factors [Citation5], and with different expressions depending on gender and age [Citation6]. Among Alaskan Native men, the suicide rate is lower in less remote settlements, as well in communities with higher median income, number of married couples, and traditional elders [Citation7].

A study on fatal and non-fatal suicide cases among Alaskan Natives found an over-representation of single men with cannabis misuse and little education [Citation8]. Substance use disorders are widely recognised as a predictor for mortality [Citation9]. Similarly, alcohol intoxication is present in around half of all attempted suicides and suicide deaths in the Arctic [Citation10,Citation11].

A Canadian study examining all Inuit suicides between 2003–2006 in the territory of Nunavut (N = 120) found that while the individual clinical risk factors for suicide were similar among Inuit and the general population in Canada, the Inuit experience a much higher suicide rate [Citation12].

Several studies have documented that a previous suicide attempt is the single strongest risk factor for death by suicide [Citation5,Citation6,Citation8,Citation13] and that the risk of death by suicide is up to 25 times higher among people who have previously exhibited suicidal behaviour [Citation14]. This has recently been confirmed in a review of all suicides in Greenland between 2012–2015 (N = 160). The study found that both previous suicide ideation and attempts were strong risk factors for suicide, followed by the presence of mental illness and alcohol abuse [Citation15]. Nevertheless, suicide attempts have only been sparsely investigated in Greenland [Citation16].

People with a mental illness constitute a high-risk group for suicide and suicide attempts, both while hospitalised and after discharge [Citation14,Citation17]. Although there is limited international research on suicidal behaviour in forensic patient populations, studies from prisons show a strong connection between mental illness and increased risk of suicidal behaviour [Citation18,Citation19]. As seen in other Arctic areas as well as internationally [Citation20,Citation21], the number of forensic patients in Greenland has almost doubled from 2009–2019 [Citation22], and currently, almost a third of all Greenlandic patients with schizophrenia have a criminal sentence to psychiatric treatment [Citation23].

The current study

Greenland has initiated several campaigns and preventative interventions to raise awareness about and prevent suicidal behaviour. The National Strategy for Suicide Prevention 2013–2019 focused on preventing suicide attempts by improving cross-sectoral coordination and inter-professional cooperation [Citation24]. A new national strategy is currently underway, this time guided by citizen participation. However, there is a paucity of research concerning suicide attempts in psychiatric populations in the Arctic, including the Greenlandic forensic psychiatry population. The current study aims to describe the prevalence and determinants of suicide attempts among Greenlandic forensic patients.

Methods

Greenland

Around 90% of the 57.000 inhabitants in Greenlandic are of Inuit origin with the rest being predominantly Danish, due to Greenland’s status as a former Danish colony [Citation25]. A third of the population lives in the capital Nuuk, while the majority live in smaller towns or villages [Citation26]. All health care services in Greenland are universal and free of charge. The national hospital in Nuuk coordinates and supervises the delivery of mental health care in the regional district hospitals and village health clinics. Of the total health care budget, close to 3% is spent on the forensic psychiatric patients treated in Denmark [Citation25].

Forensic psychiatry in Greenland

The Greenlandic Criminal Code dates back to 1954 and does not include a traditional Penal Code [Citation27]. Instead, it contains a list of possible legal sanctions and describes, how the personal circumstances of the offender must be taken into account [Citation28]. The Criminal Code intends to encourage the resocialization of offenders in a country with small communities and a perceived tradition of not expelling offenders from their community [Citation29]. As a result, Greenland did not have a closed section in any of its open institutions until 2019 [Citation30]. Offenders that require psychiatric treatment are transferred to mental health care services.

Mentally healthy and mentally ill offenders are prosecuted identically in Greenland, as the criminal code does not include concepts such as unfit to stand trial. If mental illness is suspected, or the alleged crime is of a certain severity, a pretrial forensic psychiatric examination is performed to assess whether the accused suffers from a mental illness [Citation31]. The forensic psychiatric assessment (FPA) is performed by a psychiatrist, often in cooperation with a psychologist and a translator. The FPA contains information about social background, education, criminal history, diagnosis, and is used by the court in their decision making [Citation32].

The criminal code § 156 states that, at the time of the offence, if the offender was psychotic or in a comparable condition, or was mentally disabled, measures under this chapter may be imposed when necessary to prevent the offender from committing further offences. According to the second paragraph, the same applies if the offender after the time of the offence but before the verdict has become mentally disabled or has entered a not merely transient state of insanity.

Following the criminal code § 157, the court may decide that if it is considered expedient to prevent further offences that the convicted person must be placed in a hospital or other institution in Greenland or Denmark. The second paragraph states that the court may impose less intrusive measures if these are deemed sufficient.

The majority of Greenlandic forensic psychiatric patients are treated as outpatients, and as the Department of Psychiatry in Nuuk only offers room for 3 patients in their secure screened section, patients in need of secure settings are routinely transferred to Denmark. Here, they may be admitted to a high-secure unit in Slagelse or a medium-secure 16-bed ward at the Department of Forensic Psychiatry, Aarhus University Hospital Psychiatry through an agreement between the former home rule and the Central Denmark Region [Citation33].

Study population

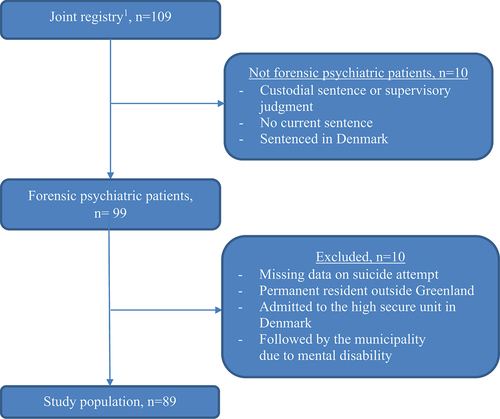

The study population was identified from a joint registry between the Greenland Prison and Probation Service (KIF) and the Psychiatric Area, Queen Ingrid’s Hospital. The registry contains names and personal identification numbers of all mentally ill offenders under Greenlandic jurisdiction. In addition, the 16 Greenlandic patients admitted to the forensic medium secure ward in Denmark were included. Only patients sentenced to treatment or placement in a psychiatric hospital per the Greenlandic Criminal Code § 157 paras 1 or 2 were included in the study. Of the 109 people in the joint registry, 10 were excluded, as they had not been sentenced to treatment or placement. We excluded 6 patients who were either sentenced to municipal care due to intellectual disability, admitted to the high secure unit in Denmark, or permanently residing outside of Greenland. After excluding 4 patients with missing information about suicide attempts, the study population comprised 89 (90%) of all Greenlandic forensic psychiatric patients ().

Materials

We collected data from the national electronic patient file (EPF), FPA’s, and legal documents concerning Greenlandic forensic patients who met the inclusion criteria on February 29th, 2020. The nationwide EPF contains data on all contacts to the somatic as well as the psychiatric health care system for both admissions and outpatient contact. All citizens are identifiable through a unique personal identification number assigned at birth. The Greenlandic health care system utilises the ICD-10 classification system.

Data Collection

We used a data collection form and coding manual developed for a large population-based study of forensic psychiatry patients in Ontario, Canada [Citation34]. We translated the data collection form and coding manual into Danish for the current study. We defined suicide attempts by use of the WHO definition, which does not take intent into account.

“An act with nonfatal outcome, in which an individual deliberately initiates a non-habitual behaviour that, without intervention from others, will cause self-harm, or deliberately ingests a substance in excess of the prescribed or generally recognized therapeutic dosage, and which is aimed at realizing changes which the subject desired via the actual or expected physical consequences”. [Citation35]

We only collected data on suicide attempts that resulted in contact with the health care system and were registered in the EPF. The methods used in the most recent suicide attempt in the EPF were recoded according to the ICD-10 codes concerning intentional self-harm (X60-84) and categorised based on methods described elsewhere [Citation36]. Marital status was based on the most recent information in the EPF. The highest level of education obtained was recorded by comparing information in the FPA with the latest EPF entry on education. In the analysis, education was dichotomised to schooling up to 11 years or higher (primary school versus A levels/gymnasium). Index offence was recorded from judgement clauses in court documents and patient files. The categorisation of violent, sexual, and non-violent offences was performed following the Canadian coding manual [Citation34]. Mental illness recorded in the EPF or FPA was dichotomised into a diagnosis within ICD-10-chapter F2 (schizophrenia and psychosis) versus all other diagnoses. Similarly, substance use disorder was based on diagnoses within ICD-10-chapter F1. Family history of alcohol or substance misuse, mental illness, or criminal convictions was collected from the FPA and EPF and included cases within biological and foster parents, grandparents, and siblings. Only diagnosed cases of mental illness and family members convicted of an offence were considered cases. Descriptions of childhood traumas were collected from the FPA and EPF and defined as events occurring before the age of 16 years.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed with Stata version 15.1 [Citation37]. Associations with a two-sided p-value below 0.05 were considered statistically significant. We did not impute missing data. We analysed continuous data with unpaired t-tests and contingency tables with either χ2 or Fisher’s exact test depending on the size of n.

Inter-rater reliability between the 2 data collectors was examined for 2 items on a random subsample of 19 patients; a F2 (ICD-10) diagnosis (yes/no) and “any intoxication at the time of the index offense” (yes/no). Cohen’s Kappa was calculated to assess inter-rater agreement and McNemar’s test was used to test marginal homogeneity. Inter-rater reliability showed moderate agreement for F2 diagnosis (kappa = 0.72). The difference in the proportion of identified cases was not statistically significant (p = 0.56). For “any intoxication at the time of the index offense”, the agreement between the raters was strong (kappa = 0.89) and no statistically significant difference in the proportion of identified cases (p = 0.32).

Ethics

The study is approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Greenland and the Health Management (Nanoq-ID 13089266/12729056) and the management for Psychiatric Area, Queen Ingrid’s Hospital.

The study has been notified to the Central Denmark Region’s internal list of research projects (Case number 1–16-02-341-19) and is approved by the Danish Agency for Patient Safety (Case No. 3–3013-3253/1). To uphold patient anonymity, small patient groups (n < 2) were not included in this study.

Results

Demographic and clinical characteristics

The study population (N = 89) had a mean age of 40.8 years (range 20–66) and 81% were men (n = 72). A total of 87% (n = 77) had a primary diagnosis of psychosis (F2, ICD-10) and 70% (n = 62) had a diagnosis of substance use disorder (F1, ICD-10) ().

Table 1. Determinants of suicide attempts among 89 Greenlandic forensic psychiatric patients. A cross-sectional study, 29 February 2020

Thirty-six percent (n = 32) had attempted suicide during their lifetime. Those who had attempted suicide had a significantly higher prevalence of substance misuse among family members compared to those who had not attempted suicide (75% versus 45% p = 0.007) as well as higher history of criminal convictions among family members (28% versus 9% p = 0.03). Furthermore, physical abuse in childhood was more prevalent among those who had attempted suicide (34% versus 16% p = 0.04). An equal proportion of women and men had attempted suicide (p = 0.95) and no type of index offence was identified as a predictor of suicide attempt (p = 0.77) ().

Methods of Suicide Attempts

Among the women who had attempted suicide, 67% had used drug intoxication (not alcohol) in their latest attempt as opposed to 27% of the men. None of the women in the sample had used firearms or sharp objects, compared to 42% of the men. No patients who had attempted suicide had used more than one method in their most recent attempt ().

Table 2. Methods used in latest suicide attempt among Greenlandic forensic psychiatric patients. A cross-sectional study, 29 February 2020

The majority of women (66%) and men (58%) had only attempted suicide once. Among the men, 19% had attempted suicide more than 2 times, for the women, the corresponding number was 17%.

Discussion

Major findings

The lifetime prevalence of suicide attempts among Greenlandic forensic psychiatric patients was 36%, with a nearly identical prevalence for men and women. A significant association was observed between attempted suicide and physical abuse in childhood, a family history of substance misuse, and a family history of criminal convictions. Women had primarily attempted suicide by drug intoxication, whereas men had more often used sharp or blunt objects or firearms.

Prevalence of suicide attempts

The few other studies having examined suicide attempts in Greenland have used different period prevalence outcomes and definitions of suicide attempts, and none have included forensic patients. Because of these differences, comparison with our findings requires considerable caution. A study from 1995 found that 20% of 159 Greenlandic general psychiatric patients, mean age 22 years, had attempted suicide before their first admission [Citation38]. The annual Greenlandic public health survey from 2018 found that 10% of Inuit aged 19–29 had reported a suicide attempt within the past year [Citation39]. Suicide attempt studies from other Arctic regions are equally heterogeneous. In a 2015 survey from Nunavik, 31% of adolescents aged 15–24 reported having attempted suicide in their lifetime [Citation40]. A literature review from 2009 focusing on mental health, substance misuse, and suicidal behaviour in the Arctic found that the lifetime prevalence of suicide attempts among adolescents varied from 9.5% in Norway to 34% in Canada [Citation41]. In our study, we describe the lifetime prevalence of suicide attempts in a patient population with a mean age of 44 years, which could partly explain the higher lifetime prevalence, but due to the described heterogeneity, further comparisons are considered unfeasible.

While the results from the present study are certainly alarming, it is noteworthy that other Arctic at-risk groups also present with high rates of suicide attempts. One reason may be that risk factors for suicide behaviour are broadly present in Arctic communities. A Nunavut psychological autopsy of 120 Inuit suicide cases found a high prevalence of psychiatric disorders (25%) and substance use disorders (36%) in the community-matched control group [Citation12]. This emphasises the need for a population-level approach to mental health initiatives. Although the provision of mental health services is challenging in a vast and sparsely populated country, the Arctic governments and communities collaborate to increase awareness and strengthen prevention efforts. Through initiatives such as Rising Sun, the Arctic Council has recently focused on identifying evaluation outcomes for suicide prevention strategies, enabling knowledge translation between the Arctic regions that share common challenges.

Methods of suicide attempt

The gender differences in methods of suicide attempts described in the present study are consistent with recent studies which found a higher prevalence of intoxication among women and more violent methods among men [Citation14,Citation26,Citation42]. This points to the need for restricting the availability of different means typically used for attempting suicide. Limiting access to weapons and over-the-counter medication is generally considered an effective approach and may play a role in preventing future suicide attempts [Citation13,Citation43].

Determinants

Difficult upbringing conditions are known to be associated with an increased risk of suicidal behaviour in Arctic populations [Citation4,Citation12,Citation16,Citation26,Citation40], and the rest of the world [Citation5]. The described associations between childhood physical abuse and substance or alcohol misuse in the family are consistent with these findings, which emphasises the importance of population-based initiatives focusing on improving childhood conditions.

In contrast to other studies [Citation2,Citation12], we did not find that childhood sexual abuse was a determinant for attempting suicide. This could be explained by the low numbers of female patients in our study, given that Greenlandic women are at a much higher risk of having experienced sexual abuse than men [Citation44]. Surprisingly, we did not find any link between violent offending and suicidal behaviour, although this has been found in several other studies [Citation45]. As the number and characteristics of patients who have died from suicide are unknown, our findings could be attributed to survival bias.

Gender

In contrast to most other studies, we found no association between gender and suicide attempts [Citation14–16]. A review from 2009 about suicidal behaviour among young people below 25 years throughout the Arctic found that men had higher rates of suicidal behaviour overall and that women had higher rates of suicide attempts [Citation41]. However, older studies from Greenland found no gender differences [Citation46,Citation47]. As the present study only included 17 women, our findings must, however, be interpreted with caution.

Strengths and limitations

To the authors’ knowledge, this is one of the first studies examining suicide attempts among forensic patients in the Arctic. The risk of selection bias is low as the study population comprises the absolute majority of Greenlandic forensic patients. All data was obtained from the national EPF and court documents, which removes the risk of recall bias. The validity of data in the Greenlandic EPF has, to the authors’ knowledge, never been examined, although medical files are generally considered valid. As the EPF has only reached full national coverage in 2018, concern over incomplete reporting outside the capital has been raised [Citation23] In this study, we had access to several data sources including older, regional versions of the EPF as well as FPA’s. FPA’s are primarily performed by forensic psychiatric experts, psychologists, and social workers, ensuring standardised, high-quality data. Health care professionals are required by law to document all care in the EPF. Furthermore, the majority of FPPs are treated at the National Hospital in Nuuk by a multidisciplinary team led by a psychiatrist. Consequently, the quality of data used in this study is considered to be high. The reliability study showed a moderate to strong agreement between the two raters which suggests acceptable inter-rater reliability.

The study, however, has several limitations that should be discussed. The use of a cross-sectional design introduces a risk of survival bias, as only forensic patients who were alive at the time of data collection were included. In addition, some suicide attempts could have been misclassified as accidents [Citation48]. Although many attempts have been made to formulate a global definition of a suicide attempt, several definitions still exist today. This hampers research and complicates international comparisons [Citation49]. A much-debated issue is that of intent – whether a person exhibiting suicidal behaviour needs to have had a clear intention to die by suicide for the action to be classified as a suicide attempt, and not deliberate self-harm, for instance [Citation49]. Also, a binary definition may not represent the fluctuating and dynamic reality of suicide intent [Citation6]. The WHO definition used in this study means that we did not consider the question of intent when recording incidents of suicide attempts. We only included incidents that resulted in contact with the health care system, and the majority of suicide attempts do not result in health care contact [Citation50]. Taking all these issues into consideration, the lifetime prevalence is most likely underestimated.

Due to changes in the software provider for the EPF and the organisational challenges of operating a health care system in such a vast area, it cannot be ruled out that some of the data sources were incomplete. This issue is considered to be random and not to have interfered with the study results.

Lastly, as we did not collect information about the patient’s age at the time of the suicide attempt, we were not able to identify high-risk age groups for targeted suicide prevention. This issue should be addressed in future studies concerning this topic.

Implications

As one of the first studies on suicidal attempts to include the majority of the Greenlandic forensic psychiatric population, the novelty and potential of this study are promising. The study is one of several steps towards understanding and encouraging discussions of suicide attempts among Arctic forensic psychiatry patient populations.

Our results emphasise the importance of health professionals considering suicide risk screening when working with high-risk patient groups. Similarly, decision-makers may use these results to focus suicide prevention strategies on population-based initiatives that include efforts to improve childhood conditions. Greenlandic forensic patients are comparable to international forensic psychiatric populations as they primarily comprise men with severe mental disorders and comorbid substance use disorders [Citation51]. The results of this study may provide a basis for comparisons to be made against other forensic psychiatric populations to increase our understanding of this low-volume, but high-cost patient population.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the staff at the psychiatric area of Queen Ingrid’s Hospital and the psychiatric outpatient clinic in Nuuk for supporting the data collection and the study. The authors would also like to acknowledge Francisco Alberdi Olano from the psychiatric area in Nuuk for his comments and suggestions to the final manuscript.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

Due to the nature of this research, participants of this study did not agree for their data to be shared publicly, so supporting data is not available.

Additional information

Funding

References

- WHO. Suicide in the world: global Health Estimates. (Geneva: World Health Organization). 2019. License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

- Bolliger L, Gulis G. The tragedy of becoming tired of living: youth and young adults’ suicide in Greenland and Denmark. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2018;64(4):389–9.

- Young TK, Revich B, Soininen L. Suicide in circumpolar regions: an introduction and overview. Int J Circumpolar Health. 2015;74(1):27349.

- Bjerregaard P, Lynge I. Suicide - A challenge in modern Greenland. Arch Suicide Res. 2006;10(2):209–220.

- Kanchan T. Forensic Psychiatry and Forensic Psychology: suicide Predictors and Statistics. In: Encyclopedia of Forensic and Legal Medicine, Second Edition ed., Vol. 2, Amsterdam: Elsevier Ltd., 2015:688–700.

- Sveticic J, De Leo D. The hypothesis of a continuum in suicidality: a discussion on its validity and practical implications. Ment Illn. 2012;4(2):73–78.

- Berman M. Suicide among young Alaska native men: community risk factors and alcohol control. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(S3):329–335.

- Wexler L, Hill R, Bertone-Johnson E, et al. Correlates of Alaska Native Fatal and Nonfatal Suicidal Behaviors 1990-2001. Suicide Life-Threatening Behav. 2008 Jun;38(3):311–320.

- Uhrskov Sørensen L, Bengtson S, Lund J, et al. Mortality among male forensic and non-forensic psychiatric patients: matched cohort study of rates, predictors and causes-of-death. Nord J Psychiatry. 2020:1–8.

- Nexøe J, Wilche JP, Niclasen B, et al. Violence- and alcohol-related acute healthcare visits in Greenland. Scand J Public Health. 2013;41(2):113–118.

- Perkins R, Sanddal TL, Howell M, et al. Epidemiological and follow-back study of suicides in Alaska. Int J Circumpolar Health. 2009;68(3):212–223.

- Chachamovich E, Kirmayer LJ, Haggarty JM, et al. Suicide among Inuit: results from a large, epidemiologically representative follow-back study in Nunavut. Can J Psychiatry. 2015 Jun 1;60(6):268–275.

- World Health Organization. Preventing suicide: a community engagement toolkit. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2018. Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

- Burón P, Jimenez-Trevino L, Saiz PA, et al. Reasons for Attempted Suicide in Europe: prevalence, Associated Factors and Risk of Repetition. Arch Suicide Res. 2016;20(1):45–58.

- Grundsøe TL, Pedersen ML. Risk factors observed in health care system 6 months prior completed suicide. Int J Circumpolar Health. 2019;78(1):1617019.

- Olano FA, Rasmussen J. Psykiatriske lidelser i Grønland. Ugeskr Læger. 2019;181:V06190345.

- Jones RM, Hales H, Butwell M, et al. Suicide in high security hospital patients. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2011;46(8):723–731.

- Voulgaris A, Kose N, Konrad N, et al. Prison suicide in comparison to suicide events in forensic psychiatric hospitals in Germany. Front Psychiatry. 2018;9:1–7.

- Fazel S, Baillargeon J. The health of prisoners. Lancet. 2011;377(9769):956–965.

- Sundheds- og Ældreministeriet. Mulige årsager til udviklingen i antallet af retspsykiatriske patienter samt viden om indsatser for denne gruppe. København: Sundheds- og Ældreministeriet; 2016.

- Latimer J, Lawrence A. The review board systems in Canada: overview of results from the Mentally Disordered Accused Data Collection Study. Ottawa (ON): Research and Statistics Division / Department of Justice Canada; 2006.

- Kriminalforsorgen. Statistik 2019. Copenhagen: Direktoratet for Kriminalforsorgen; 2019.

- Jakobsen AS, Pedersen ML. Schizophrenia in Greenland. Dan Med J. 2021;68(2):1–7.

- Departementet for Sundhed og Infrastruktur. National strategi for selvmordsforebyggelse i Grønland 2013-2019. Nuuk: Naalakkersuisut; 2013.

- Niclasen B, Mulvad G. Health care and health care delivery in Greenland. Int J Circumpolar Health. 2010;69(5):437–487.

- Bjerregaard P, Larsen CVL. Time trend by region of suicides and suicidal thoughts among Greenland inuit. Int J Circumpolar Health. 2015;74(1):1–8.

- Andersen J. Grønlands Videnskabshistorie - Den Juridiske Ekspedition-et studie i Grønlands retsforhold. Arkt Forskningsjournal. 2010;2:255–272.

- Larsen FB. Greenland criminal justice: the adaptation of western law. Int J Comp Appl Crim Justice. 1996;20(2):277–290.

- Lauritsen AN. Den store grønlandske indespærring. Dansk Sociol. 2014;25(4):35–53.

- Grønland - Kriminalforsorgen [Internet]. [accessed 2022 Feb 01]. Available from: https://www.kriminalforsorgen.dk/om-os/kriminalforsorgens-opgaver/groenland/

- Kramp P. Retspsykiatri. 1. udgave. Kbh: GadJura; 1996. p. 395 sider.

- § 809. The Danish Civil Procedure Code (Retsplejeloven). Denmark: Ministry of Justice; 2001.

- Folketingets Sundhedsudvalg. Sundhedsudvalgets spørgsmål til sundhedsministren 29.03.2000 [Internet]. [accessed 2022 Feb 01]. Available from: http://webarkiv.ft.dk/?/samling/19991/udvbilag/suu/almdel_bilag684.htm

- Chaimowitz G, Moulden H, Upfold C, et al. Ontario forensic mental health system: a population-based review. Can J Psychiatry. 2021 Jun;7067437211023103.

- Bille-Brahe U, Schmidtke A, Kerkhof AJ, et al. Background and introduction to the WHO/EURO Multicentre Study on Parasuicide. Crisis. 1995;16(2):72–79.

- Michel K, Ballinari P, Bille-Brahe U, et al. Methods used for parasuicide: results of the WHO/EURO Multicentre Study on Parasuicide. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2000;35(4):156–163.

- StataCorp. Stata Statistical Software: release 15. College Station, TX: StataCorp LLC; 2017.

- Larsen CVL, Hansen CB, Ingemann C, et al. Befolkningsundersøgelsen i Grønland 2018. Levevilkår, livsstil og helbred. Statens Institut for Folkesundhed, SDU. 2019;30:62.

- Fraser SL, Geoffroy D, Chachamovich E, et al. Changing rates of suicide ideation and attempts among Inuit youth: a gender-based analysis of risk and protective factors. Suicide Life-Threatening Behav. 2015;45(2):141–156.

- Lehti V, Niemelä S, Hoven C, et al. Mental health, substance use and suicidal behaviour among young indigenous people in the Arctic: a systematic review. Soc Sci Med. 2009;69(8):1194–1203.

- Bloch LH, Drachmann GH, Pedersen ML. High prevalence of medicine-induced attempted suicides among females in Nuuk, Greenland, 2008-2009. Int J Circumpolar Health. 2013;72(1):21687.

- Sargeant H, Forsyth R, Pitman A. The Epidemiology of Suicide in Young Men in Greenland: a Systematic Review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018 Nov;15(11):2442.

- Lynge I, Jacobsen J. Schizophrenia in Greenland: a follow‐up study. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1995;91(6):414–422.

- Curtis T, Larsen FB, Helweg-Larsen K, et al. Violence, sexual abuse and health in Greenland. Int J Circumpolar Health. 2002;61(2):110–122.

- Donnell OO, House A, Waterman M. The co-occurrence of aggression and self-harm : systematic literature review. J Affect Disord. 2015;175:325–350.

- Grove O, Lynge J. Suicide and attempted suicide in Greenland: a controlled study in Nuuk (Godthåb). Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1979;60(4):375–391.

- Thorslund J Youth suicide and problems with modernization among Inuit in Greenland (Ungdomsselvmord og moderniseringsproblemer blandt Inuit i Grønland). Thesis. Roskilde Universitetscente, SOCPOL; 1992.

- Leineweber M, Arensman E. Culture change and mental health: the epidemiology of suicide in Greenland. Arch Suicide Res. 2003;7(1):41–50.

- Goodfellow B, Kõlves K, de Leo D. Contemporary Nomenclatures of Suicidal Behaviors: a Systematic Literature Review. Suicide Life-Threatening Behav. 2018;48(3):353–366.

- Larsen CP, Mikkelsen AKT. Methods and rates in relation to age and gender in two regions of Denmark. Center for Selvmordsforskning. 2015.

- Salize HJ, Lepping P, Dressing H. How harmonized are we? Forensic mental health legislation and service provision in the European Union. Crim Behav Ment Heal. 2005;15(3):143–147.