ABSTRACT

PAX Good Behaviour Game (PAX-GBG) is an evidence-based approach to co-create a nurturing environment where all children can thrive. This school-based approach was identified as a promising intervention for suicide prevention by First Nations communities in Manitoba, Canada. To enhance this mental health promotion approach, PAX Dream Makers was developed. It is a youth-led addition to PAX-GBG for middle and high school students. This study’s aim was to examine, from the communities’ perspectives, the influence of PAX Dream Makers on youth as well as its strengths, challenges and suggestions for future improvements. A case study method was conducted using interviews and focus groups with 30 youth and 17 adult mentors and elders. Participants reported that PAX Dream Makers provided support and encouragement to the youth, increased their resilience and provided an opportunity to be positive role models. It strengthened PAX-GBG implementation in schools. Challenges included: adult mentors availability, frequent teacher turn-over and community mental distress. Suggestions expressed were: being mindful of cultural and community contexts, increasing community leadership’s understanding of PAX-GBG and better recruitment of mentors and youth. PAX Dream Makers approach was well-received by communities and holds great promise for promoting the well-being of First Nations youth.

Introduction

Suicide rates vary across Indigenous nations but are disproportionately higher in comparison to their non-Indigenous counterparts in Canada [Citation1,Citation2]. The highest rates of suicide among Indigenous peoples are seen in youth and young adults between the ages of 15 and 24 years old [Citation3,Citation4]. Indigenous peoples in many countries continue to confront social, economic and health inequities emanating from colonialism, the legacy of residential schools and systemic racism [Citation5]. In Canada, First Nations, Métis and Inuit people Footnote1 are subjected to substandard diets, housing, education and health services. They often contend with racism, discrimination and disproportionately experience high unemployment, intergenerational welfare dependency, child apprehensions by child welfare agencies, and incarceration. These community and societal factors have a profound impact on the health and well-being of youth [Citation6]. Indigenous youth face the loss of culture and identity through intergenerational trauma, which has manifested into a range of mental health issues including suicide. These ongoing multiple challenges as well as cultural and contextual factors indicate that general, conventional approaches of mental health promotion may not be well-suited in meeting the needs of Indigenous youth.

Cultural considerations in mental health interventions

Culturally safe programmes and services are fundamental to improving overall health outcomes and to strengthen Indigenous people’s sense of culture, ownership, and identity – all of which are protective against suicide and self-harm behaviours [Citation7].The concept of health in many First Nations communities is a holistic one and includes cultural and spiritual components [Citation8]. Indigenous self-determination in health is the ability for Indigenous peoples to maintain and use their understandings of health. This self-determination is essential to the success of health promotion programmes and the provision of health services that aim to deliver trauma-informed culturally safe care [Citation9]. Indigenous-initiated and led mental health promotion programmes for youth are therefore quintessential in meeting the health needs of Indigenous youth. For example, an exploratory mixed method study reported a school-based relationship-based mentoring programme called the Fourth R was associated with better mental health and higher cultural identity scores [Citation10].

Importance of implementation research

While there have been previous programmes aimed at improving the mental health of Indigenous youth and at preventing suicides [Citation10,Citation11], few have examined their programme implementation. This is important because if programmes are not deemed acceptable or useful for Indigenous communities, they will likely not be implemented. Implementation research, as the name suggests, provides valuable information on how a programme is working to inform decisions about health policies, programmes, and practices [Citation12]. In examining school-based mental health promotion in a Canadian jurisdiction [Citation13], reported that focussing on implementation infrastructure and processes was deemed critical in supporting high quality mental health promotion programming. However, a review by [Citation14],noted that many studies examining mental health promotion programmes for children and youth lacked process evaluations, youth viewpoints or clarity on who implemented interventions.

This type of research is particularly useful to northern and remote First Nations communities as it aims to identify and solve implementation issues unique to these communities [Citation15]. Implementation research is therefore crucial in understanding programmes within real world conditions of First Nations in Canada and is notably concerned with how communities can fully benefit from programmes.

To address this gap, this study aims to examine a newly developed mental health promotion approach for First Nations youth. This study was led by a research team comprised of academic researchers, Swampy Cree Tribal Council (SCTC) communities, Cree Nation Tribal Health Centre (CNTHC), Healthy Child Manitoba Office (HCMO), the Manitoba First Nations Education Resource Centre (MFNERC), the First Nations Inuit Health Branch (FNIHB) and the developers, the PAXIS Institute. Over the course of the current study, over 100 SCTC community members participated in annual meetings, youth gatherings or informal meetings and at least one representative from each organisation was present at the monthly implementation meetings. Since 2007, members of this team conducted a series of investigations designed to understand the risk and protective factors for suicide among Indigenous people and to develop culturally grounded suicide intervention strategies [Citation16–18]. The research process and approach taken in this aforementioned research laid the groundwork for the present study and has been previously described [Citation19].

PAX Dream makers approach

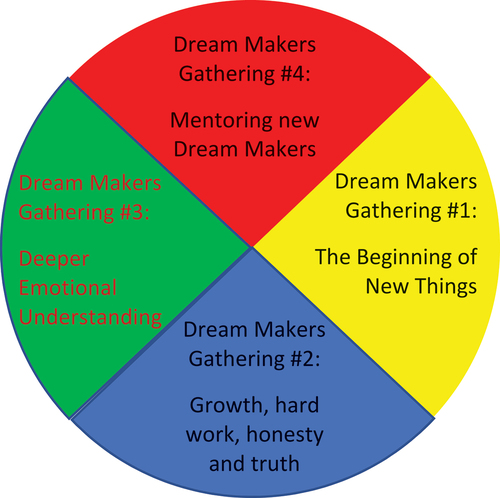

This current study therefore builds on this previous work to examine the PAX Dream Makers approach, which was supported by the SCTC to enhance an existing school based mental health promotion programme. PAX Dream Makers is a youth-led, project-based learning approach that is designed to engage middle and high school students to create peace, productivity, health and happiness in their schools and communities. It applies the evidence-based strategies of PAX-GBG to support and empower Indigenous youth (12–18 years). The Dream Makers approach addressed the expressed need for First Nations youth involvement and provided support of PAX-GBG in the schools and communities. This approach included special training through a 2-day youth gatherings and ongoing support for youth and adult mentors to develop leaderships skills and enhance their understanding of the PAX-GBG programme. shows the focus for each of the four Dream Makers Gathering. At Dream Makers Gathering #1, youth and adult mentors learn about PAX-GBG, Dream Makers youth, guided by their adult mentors, created a vision for their schools and communities. At #2, youth share their school and community visions and accomplishments with each other. They develop confidence and trust in each other and in their abilities. At #3, the youth deepen their skills and confidence and expand their visions. By #4, they learn to mentor new Dream Makers – with guidance from the PAX-GBG trainers.

The PAX Dream Makers approach is an enhancement to PAX Good Behaviour Game (PAX-GBG), an evidence-based programme designed to co-create a nurturing environment where all children can thrive [Citation20]. PAX-GBG is a school-based mental health promotion strategy found to be associated with better mental, emotional, behavioural, and academic outcomes in children and youth [Citation21–26]. It is one of the few programmes that have been shown to decrease suicidal ideation and attempts [Citation27–29]. The PAX-GBG Strategies are listed in Appendix 1.

PAX-GBG was identified as a promising intervention that the SCTC communities in northern Manitoba chose to examine further. Over the last decade, PAX-GBG had been implemented in Grade 1 classes in many First Nations schools in the Canadian province of Manitoba. Through earlier focus groups and interviews, First Nations people from the SCTC communities revealed that although PAX-GBG was viewed as a positive programme, it was challenging to implement without enhancements [Citation30]. A series of meetings were held with SCTC community members and the research team to determine how best to address these challenges. Two enhancements were suggested, developed, and introduced to improve the implementation of PAX-GBG in remote and northern Manitoba First Nations schools: PAX Whole School approach and PAX Dream Makers approach. The PAX Whole School Approach, examined in a previous paper, consisted of bringing the PAX-GBG training to the northern community and providing training to all school personnel rather than sending a few grade 1 teachers for training in the south [Citation31].

At an annual meeting between SCTC and researchers, community members identified that PAX-GBG implementation would be enhanced if youth were involved. After hearing about Indigenous youth in the US who supported PAX-GBG implementation in their schools and called themselves Dream Makers, community members decided that this approach was promising for their communities. They tasked the programme developers to create training sessions for adolescents in their communities to support PAX-GBG implementation. The First Nations community liaison, hired early on as a team member, worked closely with the programme developers to provide guidance on traditional and cultural protocols and connections with community Elders and leaders. For example, each Dream Makers Gatherings started with a grand entrance with the eagle staff, an opening prayer, a feast and cultural entertainment. Although the idea came from the youth in the US, formalising youth involvement through skill development at the Dream Makers Gatherings was a novel approach.

Study rationale and objectives

Given that the Dream Makers approach was a newly added enhancement to PAX-GBG, it was essential to increase our understanding of how this approach was working in First Nations schools and communities. This perspective had not been previously documented. To this end, the objective of this study was to examine the perspectives of youth, adult mentors and Elders on the PAX Dream Makers approach. Specifically, this study examined the following:

How has the PAX Dream Makers approach influenced the youth, their schools and communities?

What has worked well and what has not worked well with the Dream Makers approach?

What are some suggestions that could improve the Dream Makers approach?

Methods

This qualitative research used a case study design with one-on-one interviews and focus groups to address the research questions of interest to the SCTC community members. The case, being the PAX Dream Makers Approach, is bounded by time during the first implementation of the approach and by specific people who were involved in this early approach. The choice of a case study design was made because our intent was to understand the perspectives of those who participated in this first implementation of the PAX Dream Makers within a real-life contemporary context [Citation32]. These semi-structured interviews and focus groups encouraged participants to express their views about the PAX Dream Makers approach. Specifically, youth, adult mentors and Elders were asked about their impressions of the Dream Makers approach, how the approach has influenced the youth, what worked well and what did not, and any suggestions they had to improve the approach. The interview guide is provided in Appendix 2. We used the COREQ (COnsolidated criteria for REporting Qualitative research) Checklist to report our study methods.

The study sample included teen-age youth, adult mentors and Elders from the Dream Makers pilot sites in six northern and remote First Nations communities in Manitoba. The majority of the participants were Cree and some were from a Dene community. Six youth and five Dream Makers adult mentors and Elders were interviewed individually. Three Dream Makers youth focus groups (24 youth) and one Dream Makers mentors focus group (12 adults) were held. There were more female than male participants: 6 boys, 24 girls, 6 men and 11 women. The interviews and focus groups were conducted during the Dream Makers Gathering (February 2018 and November 2018), in Opaskwayak Cree Nation in Northern Manitoba. They lasted between a half hour to an hour with the exception of the adult Dream Makers mentors focus group that lasted one and a half hours. With permission and consent from participants, the interviews were audio recorded and transcribed to capture the discussions.

The study participants were contacted prior to the Dream Makers Gathering through emails and phone calls and provided with written study information and consent forms. Parental consent was obtained for the youth prior to the Gathering and assent was obtained from the youth prior to the interview or focus group. At the Gathering, the youth, adult mentors and Elders were approached individually and discreetly to participate in the study. The decision to hold a focus group or an individual interview depended on the flow of the Dream Makers Gatherings. All the adult mentors accepted to participate, however one quarter of the youth who were invited refused stating that they felt shy or uncomfortable being interviewed.

Five members of the research team were involved in conducting the study by interviewing (MC, GL, SM, ST) and analysis (MC, AP, GL, SM). All five members, with the exception of the student, had experience in qualitative research. The remaining authors (JW, LB, NM, FT, AM, GM, JS) contributed to the concept, design, result interpretation and review of the study. Within the research team, four were Indigenous and all other members were not. Among team members who were most involved in conducting the study: the female principal investigator (MC) has a PhD, three research associates have a MSc (2 females, AP and GL, and 1 male, SM) and a MSc female graduate student (ST). Because this study was part of a larger project that examined PAX-GBG in First Nations communities and explored ways to culturally and contextually enhance or adapt it, the research team had already met about half of the participants prior to the interviews and focus groups. Given this relationship, the research team made it clear at the beginning of each interview or focus group that they were genuinely interested in obtaining their perspectives whether they be positive or negative. While the interviewers and analysts remained open to these perspectives, they may have been influenced by prior testimonials heard at meetings and gatherings and the scientific literature that painted a positive impression of PAX-GBG and the Dream Makers approach. Some field notes were taken noting the context in which the data was collected.

A line by line thematic analysis was conducted of the individual transcripts by three members of the research team (MC, GL, SM). Using the initial transcripts, text segments of participant’s perspectives of the PAX Dream Makers Approach, as well of text segments that were indirectly related to the approach, were used to develop an agreed upon coding scheme by the researchers. As data from additional interviews were analysed, these codes were then grouped into themes and subthemes. Some refinement of the themes and subthemes occurred as new data were analysed. Data saturation was reached with the addition of the data collected at the second Dream Makers Gathering [Citation33].

Transcripts were not returned to participants because of geographical and internet issues, however, these themes and subthemes were presented at an annual meeting with the community members to a subsample of adult mentors and youth to ensure their validity. These results were used to refine the Dream Makers approach. To ensure consistency with the initial findings, the transcripts were reviewed and cross-checked using NVivo software by two members of the research team (MC, AP), one of which was not involved in the development of the PAX Dream Makers approach, the interview process or the initial analyses [Citation34]. Some refinements were made to the themes and subthemes and once again presented to a subsample of mentors and youth to ensure validity.

This research was approved by the University of Manitoba Health Research Ethics Board (HS 19857/ H2016:248) and the First Nations Health and Social Secretariat of Manitoba Health Information Research Governance Committee. Informed consent was obtained from each participant. This project was guided and overseen by SCTC communities and based on OCAP (Ownership, Control, Access, Possession) principles which are founded on ethical standards to ensure that First Nations have governance over the research in which their people are involved.

Results

Several themes and sub-themes emerged from the interviews and focus groups with the Dream Maker youth, adult mentors and Elders. Many of the themes were determined in advance based on our interview guide and others were derived from the data. We felt confident that these themes and sub-themes, as summarised in , represented the voices of those who participated in the interviews and focus groups. The first major themes listed followed from the interview guide: positive influence of Dream Makers approach on youth; strengths of and suggestions for holding Dream Makers Gatherings; qualities of good adult mentors; challenges and recommendations in implementation of the Dream Makers approach. The last themes listed emerged from the data: empowerment through culture; community context; and positive effects and challenges in implementing PAX-GBG in schools. We will report the findings by these major themes.

Table 1. Summary of major themes and sub-themes.

Positive influence of PAX Dream makers approach on youth

When asked about their general impression of the PAX Dream Makers approach and its possible impact on the youth, all participants voiced that it had a positive influence on the youth and in turn in their schools and communities. shows the subthemes and quotes from community members to illustrate the impact of Dream Makers. Some pointed out that being part of Dream Makers provided support and encouragement to the youth. This support came from other Dream Makers youth whereby youth helped one another and also from the adult mentors guiding them. Many participants related how being part of Dream Makers made them more resilient, gave them a voice, increased their confidence, gave them a sense of belonging and a chance to develop skills. The youth, guided by their adult mentors, developed a vision for their schools and communities. Almost every interview or focus group provided concrete examples of initiatives they led including anti-bullying activities, anti-littering activities, community tours, advocating for musical instruments, fashion shows, involvement in PAX-GBG and other school programmes, the seven teachings, lunch sales for fundraising, skits to present in classes and Dream Makers meetings. A large proportion of participants pointed out that the Dream Makers youth were role models for the younger children and that their participation strengthened the PAX-GBG programme in the school.

Table 2. Positive influence of PAX dream makers approach on youth.

Dream makers gatherings: strengths and suggestions

Dream Makers Gatherings were held in northern Manitoba among the Swampy Cree Tribal Council communities. Many participants expressed that the gatherings were viewed positively by the youth and adult mentors. They found the Gatherings to be “fun”, “enjoyable” and “good”. However, there were also suggestions to improve them. Quotes supporting the strengths of and suggestions for the Dream Makers Gatherings are shown in . A critical strength expressed by many respondents was how beneficial it was for the youth and adult mentors to connect with people from other First Nations communities. It was good for both youth and adults to learn from each other and to share what they had accomplished with others. Regarding the actual content of the Gatherings, some adults felt that the role playing was an important component and one youth explained how she enjoyed sharing their community action plan with others. The Blanket Exercise was often mentioned as a powerful experiential exercise for the youth and mentors to learn and understand their history. They felt that the PAX-GBG trainers were skilled at addressing the subject of suicide and were wise to involve the attending Elder in these difficult discussions. A few of the adult mentors expressed their appreciation of trainers “keeping with the script” and being punctual, although some felt that they could have been more so. One adult mentor commented on how caring the trainers and the organising staff were and how this set a positive tone to the Gatherings.

Table 3. Strengths and suggestions to the dream makers gathering.

In terms of suggestions, the adults would have liked more skill building for the mentors, for example, learning how to inspire and motivate the youth and how to use technology. Many also thought the youth could learn more public speaking skills. Some mentors cautioned that it was important to carefully plan the supervision of youth for their safety – particularly during the night. While the youth attending the Gatherings are generally responsible, some may be tempted to venture out on their own. A few adults thought that the Gathering could be three days long rather than two days given the quantity of the material covered. One adult mentor voiced the importance of a closing exercise as many difficult subjects were discussed during the course of the Gathering. Finally, the organisers should remember that travelling in Northern Manitoba is challenging: distances are great, airplane connections are complicated, many roads are in poor condition, some roads only available on frozen waterways, and hazardous winter driving conditions. It is important to allow enough time for participants to travel to and from the Gathering safely.

Qualities of a good mentor

Adult mentors were asked about some of the qualities they believed were critical to being a good mentor for the youth. Most related the importance of dedicating time and being committed to guiding the youth. Some mentors expressed that they must be willing to build strong relationships with the youth. Good mentors also encourage the youth to be empowered and autonomous, rather than doing things for them.

“It takes dedication and you’re wanting to empower the youth. Dedication is first and then empowering the youth that they can bring out the special gifts that they have within themselves because they’re always second guessing themselves”. (adult I10)

“Then when I listened to them and then I watched them and I take them to the front (of the class) and just ditch them there, because they’re growing and, I’m growing too because I can’t do it for them, they have to do it, it’s like being a parent, you can’t do everything for your kids or they’re never going to do it themselves”. (adult FG14-1)

“And often they’ll confide in you and it gives you that opportunity to often save a life. It might sound extreme but its not, its an everyday reality in the north, the few words that you tell them and all the encouragement it can be as silly as I love the new socks you have today, you know things like that”. (adult I4)

Challenges and suggestions to the PAX dream makers approach

While the PAX Dream Makers approach appeared to have a positive influence on the youth, respondents also described challenges to its implementation as shown by the quotes in . Accordingly, they provided some suggestions to address these challenges. A challenge often expressed was that the adult mentors have many other responsibilities, making it difficult for adults to accept and fill the mentor role. Similarly, youth are involved in many activities such as sports and other school activities, making it difficult for them to participate in Dream Makers. Both youth and adult mentors recognised the importance of meeting but found it difficult to hold them. The most cited reason was time, but other challenges included cold weather and the commute between the school and the community – some schools are a considerable distance from the community. Another important challenge is that in a few communities, youth and adult mentors do not feel they have the support from the community leadership or the school leadership. One adult mentor felt that some adults were not comfortable with youth leading an initiative. Increasing awareness of the Dream Makers approach was seen as a possible way of addressing these challenges. In doing so, it was crucial to be aware of the language used. Community members do not always understand what a programme is about because of language barriers. Ideas to make school personnel more aware of the Dream Makers approach is to provide hallway passes to the Dream Makers youth and to update the school staff on the Dream Makers’ initiatives. The adult mentors expressed the wish to have more youth benefit from the approach. The mentors noted that older youth had graduated and that actively recruiting younger Dream Makers was an important strategy for sustaining this approach.

Table 4. Challenges and suggestions to the dream makers approach.

Empowerment through culture

Many participants expressed the importance of incorporating culture in the Dream Makers approach. They felt that the youth became empowered from learning about their identity, culture and language. One Elder articulated it this way,

“I know a lot of the young adults want to know about, about our culture and all that and, and the seven teachings and so on and they wanted to know the rights of passage and so on. So those kind of things ‘cause they were not taught at home, they don’t know, they don’t know their identity, they want to know their identity I guess ‘cause like I said all we are to the government is just a number and we’re a commodity”. (adult I15)

An Elder was present at every Dream Makers Gathering where they spoke to the youth and offered them teachings. The interviewers noted how the youth at the Gatherings took turns checking in on the Elder and offering to bring them their lunch or their tea. The Elders talked to them about making good choices and the importance of perseverance and of listening. Another Elder restated his teaching during an interview,

“That’s why I said that and that’s one thing I noticed was missing, you got to learn to listen. I, I’ve done that all my life, I sat around with the elders and I sat there not saying a word but I listened, I listened, that’s how I took my training from elders, they taught me that, they taught me a lot of things”. (adult I1).

Community context

Although the interview guided did not specifically ask about community context, some participants talked about their context. Community ties were a source of strength for the youth. One youth related with affection that her grandmother is always there for her. The adult mentors and Elders talked about how community events bring people together and these bring joy. They also acknowledged that the youth must contend with difficult circumstances in their families and communities. They talked about the effects on youth of alcohol, drug abuse, suicide, and difficulty finding employment. As one youth expressed, “there was a lot of people passing away from suicide”. (youth I8). At the Dream Makers Gathering, the youth depicted some of these challenges through role playing and it saddened the adults.

“I kind of felt sad though some of the stuff they were portraying was like daily … and I just thought I grew up in a rough place as well and I don’t think I have that, it in me to go and put it on a stage the way they did … ” (adult FG14-1)

Strengths and challenges to PAX-GBG implementation

Although the focus of the interview guide was on the Dream Makers Approach, some participants naturally drew connections between Dream Makers and the implementation of PAX-GBG in their schools. As shown by the quotes in , they felt that PAX-GBG was improving the school environment, that the hallways were quieter and that the PAX strategies were being used in classrooms and at school assemblies. The Dream Makers youth were supporting PAX-GBG by presenting the strategies in the classrooms, supporting hallway rules, and using tootles notes. However, a few adult mentors named some challenges that remained in implementing PAX-GBG including staff turnover and inconsistent use of the PAX strategies. Some expressed that connecting with other communities who were using PAX-GBG would provide support and encouragement to keep using it. The influence from outside the community can act as a catalyst for action.

Table 5. Strengths and challenges to PAX implementations.

Discussion

This qualitative study found that the PAX Dream Makers approach was well-received by First Nations communities and holds great promise for promoting the well-being of youth. This approach builds on youth’s knowledge and understanding of PAX-GBG in elementary schools, giving them the tools to create a safe and nurturing school environment. Respondents reported that the approach provided support and encouragement to the youth, increased their resilience and gave them an opportunity to be positive role models in their schools and community. Choosing good adult mentors to guide and support the youth was noted as important to the success of the Dream Makers. However, there were challenges to the approach and suggestions to improve it. In implementing the PAX Dream Makers, it is imperative to consider culture and the community context. An example is that the presence of an Elder, opening the Gathering with a prayer and closing with a sharing circle and involving local artists showcasing Indigenous culture were valued. Challenges such as travel, limited availability of mentors and community stressors influenced how the Dream Makers approach was implemented.

Consistent with previous research, the findings of this study support the use and effectiveness of youth-led programmes in promoting the mental health of Indigenous youth. [Citation35],reported success in involving young people in changing school environments. As with the PAX Dream Makers approach, they found that the mentor role and the recruitment of youth to be critical factors to the success of school-based interventions. They noted that continually assessing the school’s assets and needs helped clarify appropriate actions. This was highlighted in the present study as well where youth expressed the benefit of revisiting their visions and actions plans with others at the Dream Makers Gatherings. Other programmes such as Alive and Kicking Goals! and Indigenous Hip Hop Projects (IHHP) in Australia have a focus on youth suicide prevention and aim to reduce the high suicide rate among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander youth [Citation36,Citation37]. These peer-led programmes use creativity and social innovation strategies while centring on Indigenous values and addressing certain social determinants of health that have led Indigenous communities to negative health outcomes.

Collaborating and co-learning with First Nations communities is critical in implementing mental health promotion in a sustainable way as is being aware of and respecting cultural and historical contexts. At the request of the Swampy Cree Tribal Council communities, the PAX Dream Makers approach was developed to involve youth in creating nurturing and safe school and community environments. The study protocol to evaluate the approach was developed with the SCTC communities. The findings were discussed with the community members to ensure their interviews and focus groups were interpreted correctly, but the findings also served to refine the Dream Makers approach for the future. When an intervention aligns with the community’s values and beliefs, there is a greater chance of successful implementation and better outcomes [Citation38,Citation39]. All too often, initiatives are implemented in First Nations communities without discussions with the community members, leaving them with programmes and policies that do not fit culturally or contextually in their communities.

This study adds to the scant literature on implementing culturally informed mental health promotion in Indigenous communities. [Citation40],notes the importance of evaluating mental health promotion interventions to increase our understanding of implementation process, impacts, outcomes, equity and costs in more uncontrolled “real world” conditions. A strength of this study is that it reflects the perceptions of First Nations community members about a newly developed enhancement to an existing evidence-based programme. It clarified what was working and where improvements were needed. A limitation of this study is the potential positive bias of the respondents and the researchers. This bias may have resulted by the study respondents providing more positive feedback on the Dream Makers approach and limiting criticism of this approach. Given the participatory action nature of this research, some of the researchers were involved in the development of the Dream Makers approach. We partially addressed this limitation by reviewing and crosschecking of the transcripts by a researcher who had not been involved in the development of the approach or the interview process. Another potential limitation of this study is in the reliance on respondents’ recall on reporting their impressions and experiences with the Dream Makers. Obtaining multiple points of view from adult mentors, youth and Elders may have helped to mitigate this limitation.

The research team learned some important lessons over the course of this research, most notably, that the research process was as important as the research findings. We recognised that both Indigenous and Western ways of knowing were valuable, where one worldview does not dominate the other and we strived to respect the Ownership, Control, Access, and Possession (OCAP) principles that ensure self-determination of First Nations communities over research involving their people. We can affirm that this required time and space for relationship building and community engagement. SCTC community members were involved at every stage of the research, beginning with the research proposal stage through annual research meetings organised by the Cree Nation Tribal Health Centre and academic researchers. Funds were allocated for travel and accommodation to facilitate their participation. An Indigenous community liaison was hired early on as a research team member and played a vital role in ensuring that traditional and cultural protocols were adhered to and connections to community members facilitated and sustained. The team met monthly to oversee implementation and annually with SCTC community members for guidance and for sharing and interpreting results. We spent time mentoring Indigenous students, but in the future would like to dedicate more resources to doing so. These research process considerations led not only to this study, but to the development of the PAX Dream Makers and other enhancements as well.

In conclusion, the PAX Dream Makers approach was seen to positively influence the youth and to be an important addition to implementing PAX-GBG in First Nations schools and communities. The development of PAX Dream Makers was possible because of strong partnerships between First Nations communities, organisations, government departments, programme developers and academic researchers. However, to maintain these positive effects, it will be critical to address multiple challenges expressed by First Nations respondents such as leadership support, staff turnover, recruitment of youth and mentors, allowing time for the youth to integrate new knowledge and for the challenging travel to the Dream Makers Gathering. Sustained efforts is required to address these multiple challenges inherent in implementing programme and specifically in remote First Nations communities. Doing so promises to improve the health and well-being of youth in First Nations communities.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to give recognition to the Swampy Cree Tribal Council community members for their contribution in the conception and design of this study, with special thanks to Elders Cornelius Constant and William Lathlin. The authors attended formal and informal meetings with community members throughout the study. Their guidance has been essential in developing the study protocol. We acknowledge the support and involvement of the Cree Nation Tribal Health Centre staff who co-led the PAX project. We recognize the sincerity and generosity of our government partners in Healthy Child Manitoba Office who funded the PAX-GBG in Manitoba and were dedicated to working with communities and with us to ensure the implementation and evaluation of this intervention. We are equally indebted to our government partners in the Department of Education for their continued support. We thank the Manitoba First Nations Education Resource Centre and the First Nations and Inuit Health Branch for their time, effort, direction, and funding. Finally, the authors thank the PAXIS Institute for the ingenuity, generosity, and interest in adapting and developing PAX for the benefit of Indigenous people. This study was funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, Pathways to Health Equity for Aboriginal People – Implementation Research Team Grant.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 In the Canadian context, the term First Nations refers to Indigenous individuals who are registered members of a band. First Nations has replaced the term Indian as used in the Constitution Act of 1982, which specifies that the Aboriginal Peoples of Canada consist of three groups: Indians (now called First Nations), Inuit, and Métis. In the province of Manitoba, there are five major linguistic groups among First Nations: the Anishinaabe, Cree, Anishininew, Dakota, and Dene.

References

- Government of Canada. Aboriginal mental health and well-being in: the human face of mental health and mental illness in Canada (Chapter 12). Ottawa (ON;): Minister of Public Works and Government Services Canada; 2006. https://www.phac-aspc.gc.ca/publicat/human-humain06/pdf/human_face_e.pdf

- Katz A, Kinew KA, Star L, et al. 2019 . The health status of and access to healthcare by registered first nation people in manitoba. Winnipeg: MB. Manitoba Centre for Health Policy. 105–15. Accessed 17 June 2022. http://mchp-appserv.cpe.umanitoba.ca/reference/FN_Report_web.pdf

- Chartier M, Brownell M, Star L, et al. (2020). Our children, our future: the health and well-being of first nations children in manitoba. Winnipeg, MB. Manitoba Centre for Health Policy. Accessed 17 June 2022. http://mchp-appserv.cpe.umanitoba.ca/reference/FNKids_Report_Web.pdf

- Statistics Canada. (2019). Suicide among first nations people, métis, inuit (211-2016): findings from the 2011 Canadian census health and environment cohort (CACHEC) component of statistics Canada catalogue no. 159–176. Accessed 10 June 2022. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/en/daily-quotidien/190628/dq190628c-eng.pdf?st=zglhjJBC

- Whitbeck LB, Adams GW, Hoyt DR, et al. Conceptualizing and measuring historical trauma among American Indian people. Am J Community Psychol. 2004;33(3):119–130.

- Trent M, Dooley DG, Dougé J, et al. The impact of racism on child and adolescent health. Pediatrics (Evanston). 2019;144(2):e20191765

- Kirmayer LJ, Brass GM, Holton T, et al. (2007). Suicide Among Aboriginal People in Canada. Accessed 17 June 2022. http://www.douglas.qc.ca/uploads/File/2007-AHF-suicide.pdf

- Health Canada. (2015). Ministry of Health, Ottawa, Canada. First nations mental wellness continuum framework. Accessed 17 June 2022. https://www.sac-isc.gc.ca/DAM/DAM-ISC-SAC/DAM-HLTH/STAGING/texte-text/mh-health-wellness_continuum-framework-summ-report_1579120679485_eng.pdf

- Robbins JA, Dewar J. Traditional indigenous approaches to healing and the modern welfare of traditional knowledge, spirituality and lands: a critical reflection on practices and policies taken from the Canadian indigenous example. Int Indig Policy J. 2011;2(4):2.

- Crooks CV, Exner-Cortens D, Burm S, et al. Two years of relationship-focused mentoring for first nations, métis, and inuit adolescents: promoting positive mental health. J Prim Prev. 2016;38(1–2):87–104.

- Vujcich D, Thomas J, Crawford K, et al. Indigenous youth peer-led health promotion in Canada, New Zealand, Australia, and the USA: a systematic review of the approaches, study designs, and effectiveness. Front Public Health. 2018;6:31.

- Peters DH, Adam T, Alonge O, et al. Implementation research: what it is and how to do it. BMJ (Online). 2013;347:13–f6753.

- Short KH. Intentional, explicit, systematic: implementation and scale-up of effective practices for supporting student mental well-being in Ontario schools. The International Journal of Mental Health Promotion. 2016;18(1):33–48

- O’Mara L, Lind C. What do we know about school mental health promotion programmes for children and youth? Adv School Mental Health Promotion. 2013;6(3):203–224.

- Meyers DC, Durlak JA, Wandersman A. The quality implementation framework: a synthesis of critical steps in the implementation process. Am J Community Psychol. 2012;50(3–4):462–480.

- Rasic DT, Belik S-L, Elias B, et al. Spirituality, religion and suicidal behavior in a nationally representative sample. J Affect Disord. 2008;114(1):32–40.

- Sareen J, Isaak C, Bolton S-L, et al. Gatekeeper training for suicide prevention in first nations community members: a randomized controlled trial. Depress Anxiety. 2013;30(10):1021–1029.

- Spiwak R, Sareen J, Elias B, et al. Complicated grief in aboriginal populations. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2012;14(2):204–209.

- Isaak CA, Campeau M, Katz LY, et al. Community-based suicide prevention research in remote on-reserve first nations communities. Int J Ment Health Addict. 2009;8(2):258–270.

- Johansson M, Biglan A, Embry D. The PAX good behavior game: one model for evolving a more nurturing society. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev. 2020;23(4):462–482.

- Bradshaw CP, Zmuda JH, Kellam SG, et al. Longitudinal impact of two universal preventive interventions in first grade on educational outcomes in high school. J Educ Psychol. 2009;101(4):926–937.

- Dion E, Roux C, Landry D, et al. Improving attention and preventing reading difficulties among low-income first-graders: a randomized study. Prevent Sci. 2011;12(1):70–79.

- Flower A, McKenna JW, Bunuan RL, et al. Effects of the good behavior game on challenging behaviors in school settings. Rev Educ Res. 2014;84(4):546–571.

- Petras H, Kellam SG, Brown CH, et al. Developmental epidemiological courses leading to antisocial personality disorder and violent and criminal behavior: effects by young adulthood of a universal preventive intervention in first- and second-grade classrooms. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2008;95:S45–S59.

- Poduska JM, Kellam SG, Wang W, et al. Impact of the good behavior game, a universal classroom-based behavior intervention, on young adult service use for problems with emotions, behavior, or drugs or alcohol. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2008;95:S29–S44.

- Smith S, Barajas K, Ellis B, et al. A meta-analytic review of randomized controlled trials of the good behavior game. Behav Modif. 2021 Jul;45(4):641–666. Epub 2019 Oct 3.

- Bennett K, Rhodes AE, Duda S, et al. A youth suicide prevention plan for Canada: a systematic review of reviews. Can J Psychiatry. 2015;60(6):245–257.

- Katz C, Bolton S-L, Katz LY, et al. A systematic review of school-based suicide prevention programs. Depress Anxiety. 2013;30(10):1030–1045.

- Wilcox HC, Kellam SG, Brown CH, et al. The impact of two universal randomized first- and second-grade classroom interventions on young adult suicide ideation and attempt. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2008;95(Suppl 1):S60–S73.

- Jack EM, Chartier MJ, Ly G, et al. School personnel and community members’ perspectives in implementing PAX good behaviour game in first nations grade 1 classrooms. Int J Circumpolar Health. 2020;79(1):1735052.

- Wu YQ, Chartier M, Ly G, et al. Qualitative case study investigating PAX-good behaviour game in first nations communities: insight into school personnel’s perspectives in implementing a whole school approach to promote youth mental health. BMJ Open. 2019;9(9):1–10.

- Creswell J.W. 2013. Qualitative inquiry and research design : choosing among five approaches. 3rd ed. Los Angeles, CA: SAGE Publications .

- Liamputtong P. (2013). Research methods in health: foundations for evidence-based practice. 2nd ed. Melbourne: Oxford University Press. p. 375–376.

- Bazeley P. Foundations for thinking and working qualitatively. In: Seaman J, editor. Qualitative data analysis practical strategies. London: Sage Publications Ltd; 2013. p. 3–31.

- Fletcher A, Fitzgerald-Yau N, Wiggins M, et al. Involving young people in changing their school environment to make it safer. Health Educ. 2015;115(3/4):322–338. (Bradford, West Yorkshire, England).

- Hayward C, Monteiro H, McAullay D. Evaluation of Indigenous Hip Hop Projects. Melbourne:Beyondblue; 2009. Accessed 17 June 2022. https://kipdf.com/evaluation-of-indigenous-hip-hop-projects_5ad919697f8b9aec148b45c1.html#

- Tighe J, McKay K. Alive and kicking goals! Preliminary findings from a Kimberley suicide prevention program. Adv Ment Health. 2012;10(3):240–245.

- Domitrovich CE, Pas ET, Bradshaw CP, et al. Individual and school organizational factors that influence implementation of the PAX good behavior game intervention. Prevent Sci. 2015;16(8):1064–1074.

- Han SS, Weiss B. Sustainability of teacher implementation of school-based mental health programs. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2005;33(6):665–679.

- Barry M. Implementing mental health promotion. In: Barry M, Jenkins R, editors. Implementing mental health promotion. 2nd ed. Springer Nature Switzerland AG; 2019. p. 59–89.

Appendix 1:

.PAX-GBG Strategies

Appendix 2:

.Interview Guide for Dream Makers Mentor

Explain why the focus group/interview is being done

How is everyone today? Thank-you for participating in this focus group. Dream Makers are a new group in your school. We are doing a study to find out about how the Dream Makers are doing. This will help the trainers like Nancy, Claire and Tim know how to plan the next Dream Makers Gathering with other youth. It will help youth in other parts of Manitoba and around the world.

We are going to ask you questions about the Dream Makers – it should take about 45 minutes to an hour. We are also talking to youth, teachers, and principals about it.

We are going to tape it – so that we can remember our discussion here today.

As researchers, we will never use your name when we write about what you share with us. We’ll write something like, “The mentors in the DM group thought this or that”.

When we are finished our report, we will share it with you and your school. Is that OK with you?

Before we start, let’s discuss a few ground rules. We look forward to hearing your ideas, thoughts and feelings. We respect and honour all you will say. It would be important that what we share here today is not shared outside this circle. We will be talking about Dream Makers, but it could happen that someone in this group shares some personal stories. As we mentioned before, as researchers, we will never use your name when we share what you share with us.

Using colours instead of names helps keep names private. (Explain the colour system)

We will be using the colour system during the focus group today. Has anyone every used this approach before? I’ll explain why we are using it and how it works. Due to privacy and confidentiality, we want to keep everyone’s identity private. Since everyone will be sharing their personal perspectives, we want to ensure NO NAMES will be recorded. As such, everyone will be assigned a colour. When you would like to refer to a specific person in this group or ask a person questions, we will address this person by their colour. Does that makes sense to everyone? Do you have any questions?

Tell us about how the DM approach is working in your school? In your view, how are things going with the DMs? (general impression- round table)

Thinking about the projects/initiatives the DM are working on, do you think there has been an impact? If so, can you tell us what you’ve seen? If not, can you tell us why you think that is? For example, have you noticed changes with the DM youth, school environment? (mood or feeling in the school), other students that are not DM, school staff, community?

Optional probe: Have any of your colleagues mentioned any changes they saw?

Optional probe: Do you think there has been an impact from the DM projects/initiatives? Can you tell us about that?

(3) Thinking about the role of DM mentors: Can you tell us about what it takes to be a mentor? Can you describe a good DM Mentor? (round table)

Optional probe: What are some characteristics you think are important for mentors to have?

(4) Can you tell us about your experiences as being a DM Mentor? We’d like to hear about what went well and also about what was challenging? And how you tried to overcome these challenges?

Optional probe: What do you think would help you with your work as a DM mentor?

(5) The goal of the first DM Gathering was to increase youths’ understanding about PAX, foster their leadership skills, support them in bringing their ideas on how to improve their school and community.

What do you think went well during the 1st gathering? Is there anything you would change or add to the 1st gathering? When you tell us about what went well and what should be changed, please tell us why do you think was this important?

(6) Did you feel there was enough support/ guidance for the mentors? (During and after the 1st gathering) If so, what stood out to you the most? (What did you find was most helpful?) If not, what do you think needs to be done to help the mentors?

(7) What does being a Dream Maker Mentor mean to you? What is your vision for the DM in your school? (round table)

(8) IF WE HAVE TIME: What do you think is needed to keep the DM sustainable in your school/community? (time permitting)

(9) Is there anything that you would like to share that we haven’t covered? For example, about the DM Mentors, the DM youth, the approach or process? (Round table)

Interview Guide for Dream Makers – Youth

Explain why the focus group is being done

Hey Dream Makers – How is everyone today? Thank-you for participating in this focus group. Dream Makers are a new group in your school and we are doing a study to find out about how the Dream Makers are doing. This will help the trainers like Nancy, Claire and Tim know how to plan the next Dream Makers Gathering with other youth. It will help youth in other parts of Manitoba and around the world.

We are going to ask you questions about the Dream Makers – it should take about 45 minutes to an hour. We are also talking to the mentors, teachers, and principals about it.

We are going to tape it – so that we can remember our discussion here today.

As researchers, we will never use your name when we write about what you share with us. We’ll write something like, “The youth in the DM group thought this or that”.

When we are finished our report, we will share it with you and your school. Is that OK with you?

Before we start, let’s discuss a few ground rules. We look forward to hearing your ideas, thoughts and feelings. We respect and honour all you will say. It would be important that what we share here today is not shared outside this circle. We will be talking about Dream Makers, but it could happen that someone in this group shares some personal stories. As we mentioned before, as researchers, we will never use your name when we share what you share with us.

Using colours instead of names helps keep names private. (Explain the colour system)

We will be using the colour system during the focus group today. Has anyone every used this approach before? I’ll explain why we are using it and how it works. Due to privacy and confidentiality, we want to keep everyone’s identity private. Since everyone will be sharing their personal perspectives, we want to ensure NO NAMES will be recorded. As such, everyone will be assigned a colour. When you would like to refer to a specific person in this group or ask a person questions, we will address this person by their colour. Does that makes sense to everyone? Do you have any questions?

How many of you attended the First Dream Makers Gathering in October? (show of hands) _______

Could you tell us about the Dream Makers in your school? Is there something the DM did that stood out to you? Why did it stand out to you? Can you describe the DM at your school? (round table)

What types of projects have you been planning or have already done? Can you tell me about the projects the DM are working on? Are you planning other projects? Can you tell me a bit about them?

Can you tell us how the DMs are set-up (organised)? Do you meet regularly? Do you always meet with the mentors? Who decides on what activities the DM are doing?

What did you think of the Dream Makers Gathering in October? (for those who attended) What was helpful in preparing you to be a Dream Maker? Was there anything missing – that would have been helpful in preparing you to be a Dream Maker?

What does being a DM mean to you – as a youth? Has being a DM taught you new skills? Or have you developed new talents? (round table)

We would like to know about what would be helpful to the Dream Makers in your school. Thinking about the last few months, as a DM was there anything that you felt could have made things easier for you and your group to do projects? Was there anything that really helped the DM in planning a project/activity?

Optional prompt: If you could choose one thing that would help the DM, what would it be and why?

(8) We’d also like to know what was not helpful. Is there anything that stood in the way of the DM in the last few months? How have you tried to overcome these challenges?

(9) Have you used the PAX strategies in your activities/projects? For example, the Tootles, PAX hands and feet, etc. If so, can you tell us about it? Why did you choose to use that particular strategy? If not, can you tell us why you did not use the strategies? What did you use/do instead?

Optional probe: Can you describe a time when using PAX was helpful to you or your group?

(10) What do you think the Dream Makers has brought to your school? Can you think about a time when you saw a change in your school after the DM planned an activity? Can you tell us about that? For example, changes with the students or teachers. Do you notice a change in the school after the DM came back from the Gathering in October?

Optional probe: What have DM brought to the youth involved? Do you notice any changes in others? Like the other DM or other students? Do you think it has helped other students? How?

(11) Do you think it is important to have DM in your school? Why or why not? (round table)

(12) (Time permitting) Thinking back on the projects that the DMs have done, why did the DM group choose to work on these projects? How did you decide what to work on? We wonder how the idea for this project came about?

(13) (Time permitting) Do you have contact with the DM from another community? Do you think it would be helpful to be talking to other DM from another community? Why?

(14) (Time permitting) As a DM, what do you hope to accomplish by the end of the school year?

(15) Is there anything else that you would like to tell us about the DM?

(round table)