ABSTRACT

Indigenous clients in need of residential care for substance use disorders (SUD) often present with the diagnosis of substance use disorder (SUD) combined with intergenerational trauma (IGT) or both. SUD is exceedingly prevalent amongst Indigenous peoples due to the health impacts of colonisation, residential school trauma, and IGT on this population’s health. We evaluated the effectiveness of a Two-Eyed Seeing approach in a four-week harm reduction residential treatment programme for clients with a history of SUD and IGT. This treatment approach blended Indigenous Healing practices with Seeking Safety based on Dr. Teresa Marsh’s research work known as Indigenous Healing and Seeking Safety (IHSS). The data presented in this study was drawn from a larger trial. This qualitative study was undertaken in collaboration with the Benbowopka Treatment Centre in Blind River, Northern Ontario, Canada. Patient characteristic data were collected from records for 157 patients who had enrolled in the study from April 2018 to February 2020. Data was collected from the Client Quality Assurance Survey tool. We used the qualitative thematic analysis method to analyse participants’ descriptive feedback about the study. Four themes were identified: (1) Motivation to attend treatment; (2) Understanding Benbowopka’s treatment programme and needs to be met; (3) Satisfaction with all interventions; and (4) Moving forward. We utilised a conceptualised descriptive framework for the four core themes depicted in the medicine wheel. This qualitative study affirmed that cultural elements and the SS Western model were highly valued by all participants. The impact of the harm reduction approach, coupled with traditional healing methods, further enhanced the outcome. This study was registered with clinicaltrials.gov (identifier number NCT0464574).

Background

It is well established that Indigenous populations have disproportionately high rates of SUD and mental illness (i.e. PTSD, depression, and intergenerational trauma), which are associated with increased severity of SUD [Citation1–3]. It is not uncommon for SUD to be a secondary condition caused by trauma, where the substance use provides relief from psychological pain [Citation4,Citation5]. The assimilation policies and practices in Canada have had widespread impacts including IGT and must be considered when addressing the current mental health and coping strategies (e.g. SUD) of Indigenous people [Citation6]. In Canada, higher rates of prescription substance use, non-prescription substance use, cannabis use, and binge drinking are reported by Indigenous adults with a parent or grandparent who attended a residential school [Citation7]. Treatment of Indigenous patients with dual disorders starts by respecting that SUD is both a symptom of distress and a coping mechanism in response to the collective oppression of Indigenous persons [Citation8].

The term “historical trauma” is also referred to as cumulative trauma [Citation9], soul wound [Citation10], and IGT [Citation11,Citation12]. The term historical trauma emerged from the psychoanalytic literature and from the work and experiences of Holocaust survivors and their families by several researchers such as: Danieli [Citation13], Erikson [Citation14], Fogelman [Citation15], Krystal [Citation16], and van der Kolk [Citation17]. Today IGT is the most common term used to describe the systematic trauma suffered by Indigenous peoples in Canada [Citation18–20]. IGT was caused by more than 500 years of systematic marginalisation [Citation21]. IGT is the transmission of historical oppression and its negative consequences across generations [Citation22].

The diagnosis of substance use disorder (SUD) combined with intergenerational trauma (IGT) is disconcertingly prevalent within Indigenous communities because of the ongoing impacts of residential schools, colonialism, and systemic racism. The mechanisms driving SUD are individual, specific, and multifactorial; Indigenous patients seeking treatment for a combination of SUD and IGT have unique considerations, and treatment programmes should be tailored to the needs of this population. Within this patient group, symptom severity and treatment needs fluctuate across the treatment spectrum. Treatment often requires a range of holistic care practices and intensive treatment services [Citation2, Citation23–25]. Residential addiction treatment programmes are appropriate for individuals with dual disorders due to their highly structured, 24-hour level of care that focuses on a variety of recovery activities (e.g. group sessions, exercise, mindfulness, education about SUD and trauma). The intent of this structured environment is to support patients with SUD to have better control over the SUD [Citation2].

There is demand for treatment models which can meet the needs of Indigenous patients, and there is emerging evidence that non-Indigenous treatment models for SUD are less effective and lead to poorer outcomes for Indigenous patients than for their non-Indigenous counterparts [Citation6, Citation26–29]. Many different non-Indigenous residential treatment models for SUD currently exist, yet few have been created or modified to meet the unique needs of Indigenous patients with SUD and IGT [Citation28, Citation30–32]. Currently, there is a treatment gap, and many Indigenous communities report a shortage of services, culturally safe treatment, and culturally informed staff [Citation31,Citation33,Citation34]. The disparity in treatment outcomes combined with the overrepresentation of SUD among Indigenous populations highlights a need for substantial improvements to residential addiction treatment programmes for Indigenous patients with SUD.

Treatment in context for Indigenous patients includes the use of residential addiction treatment programmes which welcome and emphasise the importance of Indigenous culture within an Indigenous patient’s healing journey. In doing so, SUD residential addiction treatment programmes connect individuals to their culture, which emphasises healing and helps to strengthen their Indigenous self-identity. Indigenous communities across Canada consistently emphasise culture as an integral component to maintaining mental and physical health [Citation28,Citation31–33,Citation35]. Non-Indigenous residential treatment models often fail to incorporate Indigenous cultures into their recovery programme; however, treatment programmes that integrate Indigenous culture and healing practices within their programme have been shown to be effective [Citation36–38].

The Benbowopka Treatment Centre initiated this study because of the lack of culturally sensitive evidence-based Indigenous-focused treatment options and the growing need for effective interventions due to the opioid crisis. Benbowopka’s previous abstinence model of service (pre-IHSS) excluded all individuals who were seeking residential addiction treatment for prescription drug use, opioids, or cocaine. In 2014, Mamaweswen North Shore Tribal Council directed that Benbowopka Treatment Centre should move forward with a plan for the realignment of its services to a harm reduction model that would follow the best practice strategies recommended for addressing SUD. The study proposes a treatment approach which blends Indigenous Healing practices with Seeking Safety based on Dr. Teresa Marsh’s research work known as Indigenous Healing and Seeking Safety (IHSS) [Citation39–43]. In these previous studies Dr. Marsh explored, using a mixed methods design, whether the blending of Indigenous healing practices and a mainstream treatment model, Seeking Safety, resulted in a reduction of intergenerational trauma (IGT) symptoms and SUD. Her work was supported by an Indigenous committee, Indigenous Elders, and Indigenous communities [Citation39–43].

The IHSS model is based on Seeking Safety, a conventional treatment model which is an evidence-based, present-focused, coping skills counselling model for the treatment of patients with trauma and SUD [Citation44]. The Seeking Safety manualized programme also provides information about topics through handouts that aim to teach participants a variety of skills. The majority of topics address the cognitive, behavioural, interpersonal, and case-management needs of persons with substance abuse and PTSD [Citation44]. Some examples of SS topics include: Honesty, Taking Good Care of Yourself, Recovery Thinking, Compassion, Healthy Relationships, and Asking for Help. Thus, the perspective of Seeking Safety is convergent with traditional Indigenous methods because traditional methods include the values and concepts of holism, relational connection, spirituality, cultural presence, honesty, respect, and connection to land and all of creation [Citation22,Citation28,Citation41].

This new model, IHSS, strives to treat Indigenous patients in context by incorporating traditional healing practices and ceremonies within the foundational Seeking Safety model. Therefore, we utilised a Two-Eyed Seeing approach to strengthen this research and treatment model. Two-Eyed Seeing is an Indigenous decolonising methodology that provided this project with an inclusive philosophical, theoretical, and methodological approach. Two-Eyed Seeing was first discussed in the literature in 2004 by Elder Albert Marshall from the Eskasoni Mi’kmaw Nation in Nova Scotia [Citation45]. Two-Eyed Seeing honours the strengths of both Indigenous and Western knowledge, research techniques, knowledge translation, and programme development [Citation46].

IHSS has shown to be effective at helping clients cope with IGT and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in addition to their SUD and addiction symptoms [Citation39–43]. This study evaluates the effectiveness of an approach to treating patients with IGT and SUD in a four-week residential treatment centre which replaced an abstinence-based treatment model. This novel approach is based on the validated treatment model Indigenous Healing and Seeking Safety (IHSS).

Methods

Study design

Ethics

Detailed methodology has previously been published (suppressed for review). We respected the Tri-Council Policy Statement, Chapter 9, highlighting the importance of engaging with First Nations throughout all phases of the research process. The study received approval from Laurentian University’s Ethics Board in May 2017. The authors used a decolonising approach to ensure that the process was ethically and culturally acceptable in conducting research with Indigenous peoples Menzies Citation47, Citation48, Citation49]. All parties involved in the study respected the First Nations principles of OCAP® [Citation50] by ensuring that the Mamaweswen Council maintained ownership of the data and control of the analysis and dissemination process. This study was registered with clinicaltrials.gov on 26 October 2020 (identifier number NCT0464574). All participants provided informed consent.

Study context

Most of the study context and a detailed description of the methodology has previously been published[Citation27]. Briefly, the changes implemented aimed to ensure that Benbowopka services are better able to address the SUD needs of Indigenous communities. The previous abstinence model of service (pre-IHSS) excluded all individuals who were seeking residential addiction treatment for prescription drug use, opioids, or cocaine. Hence, individuals who were prescribed medication by their physician to address SUD or mental health challenges (such as methadone and buprenorphine/naloxone) were not previously eligible for admission to Benbowopka Treatment Centre. In 2014, Mamaweswen North Shore Tribal Council directed that Benbowopka Treatment Centre should move forward with a plan for the realignment of its services to a harm reduction model that would follow the best practice strategies recommended for addressing substance use disorders. Thus, the training of Indigenous Healing and Seeking Safety (IHSS) treatment for Indigenous patients with a history of IGT and SUD was initiated in 2016.

Data collection and methods of assessment

Benbowopka Residential Treatment Programme accepts clients of all gender identities at age 18 years or older. The programme accepts Indigenous and non-Indigenous clients from all over Canada. The data for this study was collected prospectively from records for all 157 patients who had enrolled in the Benbowopka Residential Treatment Programme from April 2018 to February 2020. Enrolment in the study was terminated when the facility closed in March 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic. The data were divided by fiscal year and intake period at the request of Benbowopka. We used the Drug Use Screening Inventory (DUSI) to collect data on type of primary and secondary substances patients used. The DUSI and a revised version (DUSI-R) were developed by the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health (CAMH) to identify the consequences of alcohol and drug involvement [Citation51].

The following variables were collected and analysed descriptively: name, health card number, date of birth, postal code, status card number, gender, date of admission to the programme, date of discharge, programme completion (Y/N), Indigenous (Y/N), status First Nation (Y/N), on reserve (Y/N), primary substance, and secondary substance(s). Drug classes from primary and secondary substances were further divided into a sub-substance category. Any pertinent notes were also included in the data.

The original data included drug classes used by Benbowopka (i.e. alcohol, narcotics, prescription drugs, solvents/inhalants, and other substance). The revised data has been organised by the drug class preference of the research team (i.e. alcohol, cannabis, stimulants, opioids, depressants, hallucinogens, inhalants/solvents). Some drug names were changed to ensure clarity (e.g. brand to generic names, acid to LSD, etc.).

Data analysis

We evaluated the results of the IHSS harm reduction intervention against three distinct primary outcomes:

Patient perspective: we used the Client Quality Assurance Survey tool to assess the appropriateness and satisfaction of the abstinent-based model intervention.

Programme perspective: we used programme completion as the primary outcome (programme completion) to evaluate the effectiveness of the abstinent-based treatment model.

Community perspective: does the revised programme serve a broader range of community members requiring treatment for SUD and IGT? Does the impact of residential addiction treatment on reducing broader healthcare utilisation (through reduced substance use-related emergency room presentations and hospital admissions in the year following treatment completion) increase following IHSS implementation? This paper only focuses on the qualitative aspect, meaning the participants and programme perspective. The healthcare utilisation data analysis will be reported in a separate publication [Citation52].

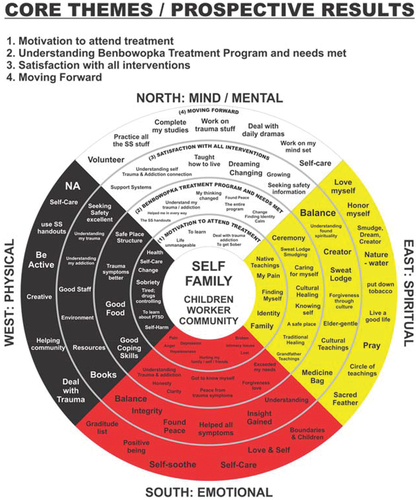

All discussions and feedback from the Client Quality Assurance Survey tool was analysed using a qualitative thematic analysis method [Citation45]. The co-principal investigator (T.M.) and one of the Indigenous researchers (D.G-F) analysed the data. This method was selected to be consistent with cultural data analysis models that require more involvement and interpretation from the researcher [Citation53,Citation54]. In step one, the text was read and re-read to identify and describe implicit and explicit ideas within the data [Citation45]. The Codes were then developed to represent the identified themes and link the raw data as summary markers. The codes arise from the researcher’s interaction with the data. Code frequencies and code occurrences were then compared, and the emerging relationships between the codes were graphically displayed. Finally, in step four, emerging themes were identified [Citation45,Citation53,Citation55] (see the Medicine Wheel in ). These themes were shared with the authors, the director, and staff of Benbowopka for validation. During data analysis, the Elders who guided this research process explored the four core themes and confirmed that these themes connected with the teachings and four quadrants of the medicine wheel. The Elders recommended that the results be depicted through the lens of the medicine wheel to authenticate the Two-Eyed-Seeing methodology (J. Ozawagosh & F. Ozawagosh, personal conversation, 20 July 2020 [Citation56]).

Results

Patient characteristics and treatment completion

The following describes participants’ demographics from the treatment programme at Benbowopka from April 2018 to February 2020 included in the prospective evaluation of IHSS. Participants: n = 157 lived throughout Ontario, Quebec, and Nunavut. Participants from Northern Ontario were 79.6%, 17.2% from southern Ontario, 2.6% from Quebec, and <1% from Nunavut. The average participant was age 34 years old, with the largest age group being 25–34 years old (44.6%) followed by 35–44 years old (23.6%), 18–24 years old (14.7%), 45–54 (8.9%), and the smallest group being 55+ years old (8.3%). 52.9% of participants were male, while 47.1% were female. Participants with poly substance use, meaning they used more than one type of substance, was 80.3%. Half, 51.6% of participants, had alcohol as their primary substance, followed by stimulants at 26.8%, opioids at 17.2%, and cannabis at 4.5%. Of the people who used poly-substances, cannabis was the most common secondary substance, with 66.7% of people who used poly-substances also used cannabis. Stimulants followed in second with 47.6%, then alcohol at 41.3%, opioids at 27.8%, hallucinogens at 14.3%, depressants at 4.8%, and inhalants at 1.6%. 72% of the cohort completed the treatment programme, while 28% did not complete the programme.

Qualitative results

We utilised feedback from the Client Quality Assurance Survey that posed 11 in-depth questions about every aspect of the treatment experience. Briefly, the 11 questions included why they entered treatment, how they understood the programme, were their needs met, helpfulness of culture and programming, helpfulness of counsellors and night staff, also to comment on the kitchen staff and food, overall satisfaction, future changes, drop-out reasons, and how the programme could improve. The four core themes that emerged in the IHSS prospective qualitative results were: (1) Motivation to attend treatment; (2) Understanding the Benbowopka treatment programme and needs met; (3) Satisfaction with all interventions; and (4) Moving forward. The 11 questions from the Quality Assurance Survey helped participants to report their experiences through a holistic view – incorporating mind, body, spirit, and physical [Citation33]. Most of the participants discussed experiences under headings such as self, family, children, worker, and community. The descriptive framework for the four core themes conceptualised in this paper is based on Rod Vickers’ interpretation of the medicine wheel and is based on the work of Duran [Citation10], Martin-Hill [Citation23], Nabigon et al., [Citation57], Nabigon [Citation58], and Vickers [Citation59]. The centre of the medicine wheel represented headings (self, family, children, worker, and community) or a lens, which participants used to frame their experiences (see ).

Core theme one: motivation to attend treatment

The Eastern quadrant of the medicine wheel represents the spiritual aspect of the individual, and for the Anishinaabe, the colour is yellow [Citation57,Citation58,Citation60]. In this quadrant, the motivation for coming to treatment included subthemes such as Indigenous teachings and pain. Other themes included finding myself, identity, and family. As one participant described, “A death in the family made me look at my own life, and I became desperate for help to stop my drinking. I was stuck, and my life was unmanageable”.

Similarly, another participant described, “Honestly, my children and especially for myself. I needed a safe place to start my healing journey and grow spiritually, mentally, physically, and emotionally as a happy and sober mom”.

The red, Southern quadrant represents the emotional aspect of the person. In the IHSS prospective analysis, rich subthemes emerged, including anger, pain, depression, hopelessness, intimacy issues, loss, hurting my family, myself, and friends. As a participant explained, “I am so confused, I don’t know how to make friends and relate to people or get a girl to like me because I am a man. I am confused because of my childhood, and I do not know intimacy”. Most of the participants said that they came to treatment because they needed to learn about their addiction and the impact of trauma. Several participants mentioned that they heard the programme now included trauma treatment, and most of them needed help for both disorders. Participants also identified feelings of profound loss and grief.

The black, Western quadrant represents the physical aspect of the person. Subthemes that emerged included health, self-care, change, and sobriety. What stood out were subthemes such as being tired, drugs controlling their lives, learning about PTSD, and self-harm. Most participants recognised experiencing suffering while using. Only a few participants were under mandatory treatment orders, but most individuals were motivated to seek treatment at a deep internal level. As one participant eloquently stated, “My influence for my decision to come to treatment was Children’s Aid Society (CAS) and my wanting to stay sober for the rest of my life to set a better example for my children”. Another participant mentioned, “How unmanageable and uncontrolled my drug and alcohol habits were. It was affecting my life and I wanted to be better and learn how to cope”.

The white, Northern quadrant represents the mental/mind of the person. Some subthemes were an unmanageable life, to get sober, education/to learn, dealing with trauma and addiction. Participants consistently described chaos in their lives and resulting loss of happiness and life. One participant described, “I needed help. I felt that I was drowning in unhappiness and experienced so many flashbacks that I found it difficult to function. Drinking alcohol was the only way for me to numb the pain”. And another lamented, “I saw my boys needed help. I tried helping them, but I got nowhere. This was my turning point. In order for me to help them, I needed to help myself”.

Core theme two: understanding the benbowopka treatment program and needs met

Most participants understood that Benbowopka was a safe, structured place where they could get help for both trauma and substance use.

In the Eastern quadrant of the medicine wheel, subthemes included cultural healing, ceremony, smudging and traditional healing. Most participants reported that their needs were met through traditional healing practices and the presence of Elders. Some participants also talked about the staff as a source of spiritual wisdom. The impact of Ceremonies on healing were frequently mentioned and many expressed their gratitude about the Sweat Lodge ceremony and Sacred Fire. Most participants expressed that the Benbowopka Treatment Centre offered a holistic approach; for example, “To discover myself. A guidance to letting go and seeking solace and peace within oneself”.

In the Southern quadrant of the medicine wheel, the subthemes that emerged were consistent across many participants and included: the programme exceeded my needs; forgiveness; understanding my trauma and addiction and love; got to know myself; honesty; clarity and peace from the trauma symptoms. Interestingly, most participants applauded the fact that they were taught and began to understand the connection between their trauma, symptoms, and addiction. Most participants consistently talked about the Western Model, the Seeking Safety content, and how it helped them connect with their feelings and emotions. For example, one participant said, “A safe place to manage emotional turmoil with the end goal of having tools and resources to live a healthy and happy lifestyle”. And yet another participant stated, “For me, Seeking Safety was double information for me. I never had this in any other program. I came here to find my Spirit and what a beautiful place to learn”. Many of the participants also reported that they had received all they needed from this treatment. For example, one participant said, “My understanding of this treatment is to love yourself again first and start loving life again. That it shows respect for yourself”.

In the Western quadrant of the medicine wheel, the subthemes that emerged were a safe place, structure, and good food. Other subthemes included improved trauma symptoms and good coping skills. As one client noted, “Yes, I feel that the program has met my needs. I have learned so much and gained so many tools. I feel so much lighter”. And yet another said, “They were all great at what they do here. I feel really great because of them (the staff), they gave me what I needed to improve self-care”. Yet another participant echoed, “[Here I learn] about trauma and substance use and all the behaviours, where I came from and why I acted the way I acted was from my PTSD and using. Using was to freeze my pain from the traumas”.

In the Northern quadrant of the medicine wheel, the subthemes that emerged were: understanding my trauma and addiction and change. The subthemes were rich in describing the Seeking Safety model. Some of the subthemes included: my thinking changed, it helped me in every way, calm, found peace, the Seeking Safety handouts, and the entire programme. Many participants expressed that it was a safe environment, a place to learn more skills and begin to understand both trauma and addiction. As one participant so eloquently stated, “This was a safe place where I could learn about my addiction and trauma and how to overcome my problem”. Another said, “Yes, this is the first program that connected substance abuse with PTSD. It makes perfect sense and provides clarity as to why I needed the substances”. Most participants appreciated the sense of safety and support they felt from the staff.

Core theme three: satisfaction with all interventions

In the Eastern quadrant of the medicine wheel, the subthemes included: found my culture, spirituality, balance, understanding, Creator, Sweat Lodge, forgiveness through culture, gentle Elders and cultural teachings. Many of the participants found that the cultural interventions, the programming, and Alcoholics Anonymous (AA) information were all equally helpful. Coming from another participant: “It helped me realise that there were much more of the cultural teachings that I needed to learn. The morning Smudge, the water, the Seven Grandfather teachings, I never knew what these teachings were all about and now I know what to do”. Another said, “I needed to connect with my Creator and all the Spiritual aspects, and this program did it for me”.

In the Southern quadrant of the medicine wheel, the themes that came forth in the IHSS prospective cohort included: found peace, balance, understanding, insight, and helped all symptoms. Many participants reflected on their satisfaction with all the interventions and reported that all the staff worked together. Most complaints were associated with the one-on-one sessions which were eventually eliminated from the treatment programme. In general, most of the participants appreciated the Seeking Safety programme and the information. For example, one participant commented, “Both parts of the program were equal, but the structure of the program helped me with my PTSD. The cultural [aspect] gave me direction and understanding of spirituality. One without the other would have been half measure”.

In the Western quadrant of the medicine wheel the subthemes that emerged were: Seeking Safety was excellent, understanding my trauma and addiction, great books to read, good staff, environment, and good resources. Most of the participants reported feeling safe and supported by staff and night attendants. As one participant explained, “Seeking Safety was the most helpful for me as I dug deep into my soul and my trauma”. Most of the participants reported that the kitchen staff, night attendants, and counsellors helped substantially. General perspectives on counsellors were positive; however, a few participants did complain about a lack of knowledge by some counsellors. Many identified self-growth and health improvements during the treatment. For example, one participant said, “The treatment made me realise that I had more issues than just alcoholism and it helped me understand where my disease stems from”. Another said, “Seeking Safety made me realise the way I think and how to change my thinking to live a good life”. Importantly, most participants valued both the Western and Traditional teachings.

In the Northern quadrant of the medicine wheel the subthemes that emerged between the pre-IHSS retrospective and IHSS prospective cohorts were: taught how to live, Seeking Safety information, help with understanding PTSD, and changing and growing. In this quadrant, most of the participants as in one voice talked about the insight they gained from the Seeking Safety topics, and they would specifically mention some of the topics. They could clearly explain sometimes in detail how their growth and understanding came. As one participant explained, “I learned the safe coping strategies, Seeking Safety and what I always wanted was learning the way of my ancestors”. Another stated, “Both components were extremely helpful for me because both helped me to understand who I really am”.

Core theme four: moving forward

Participants expressed how much they learned and benefitted from this IHSS approach and detailed what they would take away from the programme and implement to continue their healing journeys.

In the Eastern quadrant of the medicine wheel the subthemes that emerged were: self-love, honour self, active spirituality, live in ceremony, smudge, drum, Creator, nature, water, tobacco, circle, Grandfather Teachings, sacred feather, and live a good life. Many of the participants, as in one voice, talked about their wellness plan and incorporating all that they have learned about their culture and traditional healing methods. As one participant said, “The cultural and spiritual components helped me to identify who I am and gave me belonging”. Another echoed, “I always wanted to learn about my culture, and I learned a lot. This will help to keep me on the path of a true good life, through spiritual culture and self-love”.

In the Southern quadrant of the medicine wheel the subthemes included: positive being, gratitude, boundaries, self-love, and self-care. Participants clearly learned throughout the treatment to take good care of themselves, to love themselves as well as to self-sooth. Most of the topics in Seeking Safety are about safety and self-care, which is consistent with participant perspectives. For example, one participant said: “I felt like a sponge soaking up all the Seeking Safety handouts, I feel that I dealt with a lot of my trauma”. Others claimed: “The lifestyle at Benbowopka gave me the tools to change my life. I look at myself differently and I also want more out of life than just being a drunk. I want to be a good mom and I want to be good to myself”.

In the Western quadrant of the medicine wheel, subthemes that emerged were: AA and Narcotics Anonymous (NA). Other subthemes included self-care, exercise, using the Seeking Safety handouts, active and creative, helping the community, and dealing with trauma. As in the other two quadrants, most participants reported the same activities, goals, and plans. Some quotes included: “My lifestyle will change, and it will change for the better. I will be healthy, positive, and sober”. Another stated, “I intend to use the tools given here, maintain a sober, supportive network and stay sober”. These comments and feedback continued throughout the data.

In the Northern quadrant of the medicine wheel the subthemes that emerged were: to practice all the Seeking Safety stuff, self-care, work on my mindset, deal with daily dramas, complete my studies, volunteer, and work on trauma stuff. The changes that participants will implement all referred to what they were taught and what they learned during the treatment. Some of the comments that came forth included: “Since I have had time to really look and think about my life and how I have been living, I have come to see how I have been hurting both myself and those I love and those that love me”. Another stated, “Maintain sobriety one day at a time. Use coping methods that I have learned here. Be active with other suffering/recovering addicts. Maintain balance, especially the Spiritual part of my life”.

Discussion

Prior to the implementation of IHSS, the Benbowopka residential treatment programme was an abstinence-based programme termed pre-IHSS. This new Two-Eyed Seeing treatment approach, which blends Indigenous Healing practices with Seeking Safety, is based on Teresa Marsh’s research work known as IHSS [Citation39–42]. These results demonstrate that clients benefitted from both the Seeking Safety programme activities and the traditional healing practices. The atrocities and deep losses Indigenous peoples have experienced due to historical and systemic institutionalised racism in Canada have impacted many communities. We have observed that communities are now utilising their strength, resilience, and ceremonies to reclaim and express their cultural beliefs, values, and healing practices [Citation2,Citation23,Citation41–43].

The medicine wheel and the first quadrant (East and Spirituality)

The four core themes identified confirmed in current literature that in order for people with SUDS and IGT to heal, they need both educational resources and traditional healing practices [Citation6,Citation26,Citation27,Citation29]. It was affirmed through the voices and viewpoints that participants found their motivation to heal and wanted to find their identity and reconnect with themselves, their culture, and their family. This was present in both the pre-IHSS and IHSS. It is confirmed by Elders, helpers, and healers as well as Indigenous researchers that the cultural aspect and/or traditional healing practices in treatment have been reported as a successful element in SUD programmes designed for Indigenous peoples [Citation12,Citation42,Citation43,Citation61,Citation62]. It was clear that participants in both the retrospective pre-IHSS and prospective IHSS groups applauded the impact of ceremonies, such as the Sacred Fire and Sweat Lodge ceremonies, on them finding their identity and connection to their embodiment and self. Many Elders and traditional healers teach about the connection to spirit, family, and friends cultivated in a Sweat Lodge ceremony [Citation41,Citation60]. Furthermore, Rolling Thunder spoke of the healing properties of laughing and enjoying one another’s company in the Sweat Lodge [Citation63]. Elders teach that the Sweat Lodge ceremony serves as a place to go back and find our truth and our identity through the ritual healing or cleansing of body, mind, and spirit while bringing people together to honour the energy of life (personal conversation with Elders Julie and Frank Ozawagosh, 5 January 2017). In the IHSS cohort, participants reported that they felt more motivated to connect with their culture and teaching as the Seeking Safety sessions helped them to understand why they were using substances and hurting themselves. It was clear from the participants’ voices that they gained much from the Seeking Safety content while continuing to experience the benefits of Indigenous Healing described in the pre-IHSS retrospective cohort. The Seeking Safety model includes spiritual discussions through the offering of a philosophical quote at the beginning of the group sessions [Citation64,Citation65], as well as discussions about safety, cultural continuity, gentle language, and teachings about the genesis of intergenerational trauma and SUD [Citation44,Citation65]. Also, the presence of the Elders in the sharing circles was an important healing practice in using a Two-Eyed Seeing approach and helping participants to understand that both trauma and SUD were no-fault diseases, that it was not their fault. Indigenous Peoples have long recognised the role of the Elders as integral in the healing process. Elders’ skills, knowledge, and their ability to help individuals restore balance in their lives have earned them significant roles within Indigenous communities [Citation18,Citation66–68]. The Elders’ presence at Benbowopka had a huge impact on the health, healing, and wellness of the participants. The Elders also taught about Two-Eyed Seeing, which had a profound impact on participants, while also focusing on the positive identity of each person in the circle.

The medicine wheel and the second quadrant (South and Emotional)

In this quadrant, most of the IHSS participants affirmed that the IHSS programme exceeded their needs as they learned how to forgive and how to love. Participants applauded all the information they received from the Seeking Safety handouts. Many clinicians, researchers, and Elders believe that forgiveness and reconciliation help heal memories, help people to reconnect and restore present trust [Citation10,Citation57,Citation58,Citation60,Citation69–71] (personal conversation with Elder Julie and Frank Ozawagosh 20 December 2015). Previous studies identified that forgiveness and connection help to pave the way for breaking future cycles of trauma and SUD [Citation28,Citation72].

Additionally, in a recent literature review, Rowan et al. Citation37, agreed with other researchers [Citation10,Citation61,Citation73,Citation74] that incorporating Two-Eyed Seeing in treatment and research was a valuable approach to facilitate healing IGT and SUD in treatment facilities. Two-Eyed Seeing guided this work and is an example of the application of an Indigenous decolonising lens. Therefore, Two-Eyed Seeing provided valuable guidance in the blending of Seeking Safety with Indigenous healing practices [Citation46].

The medicine wheel and the third quadrant (West and Physical Body)

Central to this quadrant was the reports of doing the same thing repeatedly and getting the same result. As in the retrospective pre-IHSS cohort, participants also focussed on the impact of SUD on their wellbeing. Nardella et al. Citation75,evaluated how childhood trauma influences the relationship between suicidal behaviour and substance and alcohol addiction and the development of the self-conception of hopelessness. Their results show that suicidal and self-destructive behaviour are influenced indirectly by a traumatic childhood experience that conditions the level of hopelessness. Childhood trauma directly affected the development of drug abuse and alcoholism (Citation75].

The IHSS participants began to understand this relationship between trauma and SUD, as they expressed in unison throughout the transcripts the insight and wisdom they had gained through learning about the topics in Seeking Safety such as Honesty, Taking Good Care of Yourself, Recovery Thinking, Compassion, Healthy Relationships, and Asking for Help. These topics directly addressed trauma and addiction, but without requiring clients to delve into the trauma narrative (the detailed account of disturbing trauma memories) [Citation44,Citation64]. Thus, the treatment is easy to implement and relevant to a broad range of even the most vulnerable clients. Research shows that all forms of this model have been effective when delivered in a group or with individuals, with individuals from marginalised populations, or via inpatient or outpatient services [Citation76,Citation77]. Previous studies included a range of participant groups including adolescents, the homeless, veterans, prisoners, and others [Citation76–82].

The medicine wheel and the fourth quadrant (North and Mind/Mental)

As in the pre-IHSS retrospective cohort, participants wanted to learn and needed to understand their self-destructive behaviour. Again, participants expressed that the Seeking Safety material and teachings helped them understand that both their trauma and addiction were no-fault diseases, that it was not their fault. This realisation helped them with their shame and guilt and encouraged them to heal and have compassion for both disorders and themselves. Hien and colleagues [Citation83) compared the effectiveness of Seeking Safety and relapse prevention with non-standardised community-care treatment for 107 urban, low-income, treatment-seeking women. Participants’ SUD and PTSD symptoms improved during the Seeking Safety and relapse prevention programme but did not in the community-care treatment. Seeking Safety has also been assessed in two pilot studies as an intervention for women in correctional settings [Citation82,Citation84]. Although Hien and colleagues [Citation83) found the recidivism rate was 33% at three-month follow-up, a rate typical of this population, a significant decrease in drug and alcohol use and legal problems was found from pre-treatment to both six weeks after release and three months after release.

It was evident in the IHSS cohort that the Seeking Safety sessions such as “asking for help, self-care and grounding or detaching from emotional pain” impacted the participants wellbeing. Van der Kolk, the author of numerous articles and studies on how trauma affects the brain, says that traumatised people are “terrified of the sensations in their own bodies”, and it’s imperative that they get some sort of body-based therapy to feel safe again and learn to care for themselves [Citation85,Citation86,Citation87]. The Seeking Safety programme aims to increase the coping skills of participants with the goal of reducing the chance of relapse by emphasising values such as respect, care, integration, and healing of self [Citation64].

The medicine wheel and the centre circle

The centre circle topics affirmed that participants healed and began to understand the impact of both IGT and SUD. This also represented connection and the possibility of healing and letting go. Most participants in both the pre-IHSS cohort and IHSS cohort repeatedly described how powerful it was to experience a programme that integrated both teachings about healing and wellness, as well as traditional Indigenous healing practices. Participants affirmed that the programme helped them understand their behaviours with substances, while traditional healing practices helped them to connect with their inner spiritual self. The traditional practices also helped participants to restore their connection to their identities, their families, communities, their culture, and the Elders [Citation10,Citation61,Citation73,Citation74].

Limitations

Our analysis is based on self-reported and prospectively collected qualitative data, which comes with several limitations. One limitation is the weakness of self-reported data for patient characteristics, such as primary substance use, which may be subject to recall bias. Secondly, this study applies the themes presented in the results sections, which were based on the thematic analysis performed on the data and participants were excluded from the analysis process. The nature of qualitative work affects the generalisability of these findings, and it should be noted that the findings cannot be generalised to all residential treatment facilities in Northern Ontario. A fourth limitation in this study is the smaller sample size in this prospective arm, and the study had to be stopped prematurely due to the COVID pandemic. The next limitation was the changes in staff and new people coming on board with limited experience about the model. We were not able to do video recordings of the sessions that could have been used to validate adherence to the treatment model over time during the study.

Conclusion

During this time of reconciliation with Indigenous Peoples in Canada and beyond, residential treatment programmes, leaders, and providers have an ethical responsibility to understand and learn about the strengths of this nation. As we move forward with the focus on harm reduction, a strength-building approach, traditional healing practices, and simultaneous rehabilitation of both SUD and IGT, let this be done through an Indigenous lens. It was clear to note through the perspectives of the participants that reclamation and connection to culture and traditional healing practices were key to their healing. In this research we identified that SUD Indigenous residential treatment programmes need to include culture, healing practices, activities, and relationships that are part of the treatment process. As in the retrospective pre-IHSS data, we found that the cultural elements and healing practices of the programme were highly valued by clients in a northern Indigenous residential treatment programme. However, the Seeking Safety model and wisdom had a tremendous impact on the lives, insight, and wellbeing of all the participants in the prospective IHSS. This was evident in the themes as participants gained an understanding of both SUD and their IGT. The changes that need to be implemented will inevitably require tremendous reflection, humility, courage, and commitment by stakeholders at all levels, as we work towards harm reduction programmes, truth, reclamation, and reconciliation. Reform, change, and transformation takes wisdom, effort, and time as we work to transform health systems that disproportionately disadvantage Indigenous ways of knowing. However, our results suggest that the Western treatment model and the traditional healing practices both helped, healed, and supported participants with SUD and IGT. Based on this evidence, recommendations have been proposed for future studies that aim to use a Two-Eyed Seeing approach in residential treatment programmes to enhance the health and wellbeing of Indigenous peoples with both SUD and IGT.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge that this study would not have been possible without the involvement, support and active participation of the leadership of the North Shore Tribal Council and the generous participation of the clients and staff of Benbowopka Treatment Centre.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- MacMillan HL, Jamieson E, Walsh CA, et al. First Nations women’s mental health: results from an Ontario survey. Arch Women’s Mental Health. 2008;11(2):109–13.

- Mamakwa S, Kahan M, Kanate D, et al. Evaluation of 6 remote First Nations community-based buprenorphine programs in northwestern Ontario. Retrospective Study Can Family Phys. 2017;63: 137–145.

- Taplin C, Saddichha S, Li K, et al. Family history of alcohol and drug abuse, childhood trauma, and age of first drug injection. Subst Use Misuse. 2014;49(10):1311–1316.

- Mee S, Bunney BG, Fujimoto K, et al. A study of psychological pain in substance use disorder and its relationship to treatment outcome. PLoS One. 2019;14(11):e0216266.

- Poindexter EK, S M, Jahn DR, et al. PTSD symptoms and suicide ideation: testing the conditional indirect effects of thwarted interpersonal needs and using substances to cope. Pers Individ Dif. 2015;77:167–172.

- Dell CA, Seguin M, Hopkins C, et al. From benzos to berries: treatment offered at an aboriginal youth solvent abuse treatment centre relays the importance of culture. Can J Psychiatry. 2011;56(2):75–83.

- First Nations Information Governance Centre. The first nations regional health survey. Ottawa, ON, Canada: First Nations Information Governance Centre; 2018.

- McCormick R. Aboriginal approaches to counselling. In: Kirmayer LJ, Valaskakis GG, editors. Healing traditions: the mental health of aboriginal peoples in Canada. Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press; 2009. p. 337–354.

- Brave Heart MYH. The return to the sacred path: healing the historical trauma and historical unresolved grief response among the Lakota through a psychoeducational group intervention. Smith College Studies in Social Work. 1998;68(3):287–305.

- Duran E. Healing the soul wound: counseling with American Indians and other Native peoples. New York NY: Teacher’s College; 2006.

- Oliver JE. Intergenerational transmission of child abuse: rates, research, and clinical implications. Am J Psychiatry. 1993;150:1315–1324.

- Whitbeck LB, Adams GW, Hoyt DR, et al. Conceptualizing and measuring historical trauma among American Indian people. Am J Community Psychol. 2004;33(3/4):119–130.

- Danieli Y 1989. Mourning in survivors and children of survivors of the Nazi Holocaust: The role of group and community modalities. In: The problem of loss and mourning: Psychoanalytic perspectives, editors. Dietrich DR Shabad PC, p. 427457. Madison, CT: International Universities Press.

- Erikson E. Childhood and society. Rev. ed. New York NY: W.W Norton; 1963.

- Fogelman E. Mourning without graves. In: Medvene A, editor. Storms and rainbows: the many faces of death. Washington DC: Lewis Press; 1991. p. 25–43.

- Krystal H. Integration & self-healing in post-traumatic states. In: Luel SA, Marcus P, editors. Psychoanalytic reflections of the Holocaust: selected essays. New York NY: University of Denver (Colorado) and KTAV; 1984. p. 113–134.

- van der Kolk B. Psychological trauma. Washington (DC):American Psychiatric Press; 1987

- Evans-Campbell T. Historical trauma in American Indian/Native Alaska communities: a multi-level framework for exploring impacts on individuals, families and communities. J Interpers Violence. 2008;23:316–338.

- Haskell L, Randall M. Disrupted attachments: a social context trauma framework and the lives of Aboriginal people in Canada. J Aborig Health. 2009;5(3):48–99.

- Palacios JF, Portillo CJ. Understanding Native women’s health: historical legacies. J Transcult Nurs. 2009;20(1):15–27.

- Gagne M. The role of dependency and colonialism in generation trauma in First Nations citizens; The James Bay Cree. In: Danieli Y, editor. Intergenerational handbook of multigenerational legacies of trauma. NewYork: Plenum Press; 1998. p. 355–371.

- Gone JP. The pisimweyapiy counselling centre: paving the red road to wellness in Northern Manitoba aboriginal healing in Canada: studies in therapeutic meaning and practice. In: Waldram JB, editor. Aboriginal healing in Canada: studies in therapeutic meaning and practice. Ottawa ON Canada: Aboriginal Healing Foundation; 2008. p. 131–204.

- Martin-Hill D. Traditional medicine in contemporary contexts: protecting and respecting Indigenous knowledge and medicine. Ottawa: National Aboriginal Health Organization; 2003.

- Poonwassie A, Charter A. Aboriginal worldview of healing: inclusion, blending, and bridging. In: Moodley R, West W, editors. Integrating traditional healing practices into counseling and psychotherapy. Thousand Oaks (CA): Sage; 2005. p. 15–25.

- Rojas M, Stubley T. Integrating mainstream mental health approaches and traditional healing practices A literature review. Adv Social Sci Res J. 2014;1(1):22–43.

- Andersen LAK, Munk S, Nielsen AS, et al. What is known about treatment aimed at indigenous people suffering from alcohol use disorder? J Ethn Subst Abuse. 2019;1–35. DOI:10.1080/15332640.2019.1679317

- Li X, Sun H, Marsh DC, et al. Factors associated with pretreatment and treatment dropouts: comparisons between Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal clients admitted to medical withdrawal management. Harm Reduct J. 2013;10(1):38.

- Marsh TN, Eshakakogan C, Eibl JK, et al. A study protocol for a quasi-experimental community trial evaluating the integration of indigenous healing practices and a harm reduction approach with principles of seeking safety in an indigenous residential treatment program in Northern Ontario. Harm Reduct J. 2021a;18:35.

- Matsuzaka S, Knapp M. Anti-racism and substance use treatment: addiction does not discriminate, but do we? J Ethn Subst Abuse. 2020;19(4):567–593. Scopus.

- Dale E, Kelly PJ, Lee KSK, et al. Systematic review of addiction recovery mutual support groups and Indigenous people of Australia, New Zealand, Canada, the USA and Hawaii. Addict Behav. 2019;98:106038.

- George J, Morton Ninomiya M, Graham K, et al. The rationale for developing a programme of services by and for Indigenous men in a First Nations community. Altern. 2019;1–10. DOI:10.1177/1177180119841620

- Marsh TN, Eshkakagon C, Eibl JK, et al. Evaluating Patient Satisfaction and Qualitative Outcomes during an Abstinence-Based Indigenous Residential Treatment Program in Northern Ontario Harm Reduction Journal 2022 submitted.

- Danto D, Walsh R. Mental health perceptions and practices of a Cree community in Northern Ontario: a qualitative study. Int J Ment Health Addict. 2017;15(4):725–737.

- Legha R, Raleigh-Cohn A, Fickenscher A, et al. Challenges to providing quality substance abuse treatment services for American Indian and Alaska Native communities: perspectives of staff from 18 treatment centers. BMC Psychiatry. 2014;14(1):181.

- Hagle HN, Martin M, Winograd R, et al. Dismantling racism against Black, Indigenous, and people of color across the substance use continuum: a position statement of the association for multidisciplinary education and research in substance use and addiction. Subst Abus. 2021;42(1):5–12.

- Munro A, Shakeshaft A, Breen C, et al. Understanding remote Aboriginal drug and alcohol residential rehabilitation clients: who attends, who leaves and who stays? Drug Alcohol Rev. 2018;37(S1):S404–S414.

- Rowan M, Poole N, Shea B, et al. Cultural interventions to treat addictions in Indigenous populations: findings from a scoping study. Subst Abuse Treat Prev Policy. 2014;9(1):34.

- Rowan M, Poole N, Shea B, et al. A scoping study of cultural interventions to treat addictions in Indigenous populations: methods, strategies and insights from a Two-Eyed Seeing approach. Subst Abuse Treat Prev Policy. 2015;10(1):26.

- Marsh TN, Coholic D, Cote-Meek S, et al. Blending Aboriginal and Western healing methods to treat intergenerational trauma with substance use disorder in Aboriginal peoples who live in northeastern Ontario Canada. Harm Reduct J. 2015;12(1):1–12.

- Marsh TN, Young NL, Cote-Meek S, et al., The application of Two-Eyed Seeing decolonizing methodology in qualitative and quantitative research for the treatment of intergenerational trauma and substance use disorders, Int J Qual Methods, 2015;1–13. doi:10.1177/1609406915618046.

- Marsh TN, Young NL, Cote-Meek S, et al. Embracing Minobimaadizi, “living the good life”: healing from intergenerational trauma and substance use through indigenous healing and seeking safety. J Addict Res Ther. 2016;7:3.

- Marsh TN, Marsh DC, Ozawagosh J, et al. 2018 The sweat lodge ceremony: a healing intervention for intergenerational trauma and substance use. Int Indig Policy J 9(2). Available from: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/iipj/vol9/iss2/2

- Marsh TN, Marsh DC, Najavits LM. The impact of training Indigenous facilitators for a Two-Eyed Seeing research treatment intervention for intergenerational trauma and addiction. Int Indig Policy J. 2020;11(4). DOI:10.18584/iipj.2020.11.4.8623

- Najavits LM. Seeking Safety: a treatment manual for PTSD and substance abuse. New York NY: Guilford; 2002a.

- Creswell J. Research design: qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks (CA): Sage; 2009.

- Iwama M, Marshall A, Marshall M, et al. Two-Eyed seeing and the language of healing in community-based research. Can J Native Educ. 2009;32:3–23.

- Menzies P, Bodnar A, Harper V The role of the Elder within a mainstream addiction and mental health hospital: Developing an integrated. Native Social Work Journal. 2010;7:87–107.

- Smith LT. Decolonizing methodologies: research and indigenous peoples. London England: Zed Books; 1999.

- Wilson S. Research is ceremony: indigenous research methods. Winnipeg MB: Fernwood Publishing; 2008.

- Canadian Institutes of Health Research. (2011). Guidelines for research involving Aboriginal people. Available from: http://www.cihr-irsc.gc.ca/e/29134.html

- Ralph ET, Kirisci L. The drug use screening inventory for adults: psychometric structure and discriminative sensitivity. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 1997;23(2):207–219.

- Morin KA, Marsh TN, Eshakakogan C, et al. Community trial evaluating the integration of Indigenous healing practices and a harm reduction approach with principles of Seeking Safety in an Indigenous Residential treatment program in northern Ontario. BMC Health Serv Res. (2022)22:1045. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-022-08406-3

- Bernard HR, Ryan G. Text analysis: qualitative and quantitative methods. In: Bernard HR, editor. Handbook of methods in cultural anthropology. Walnut Creek CA: AltaMira Press; 1998. p. 595–645.

- Denzin N, Lincoln Y. The Sage handbook of qualitative research. 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks (CA): Sage; 2005.

- Boyatzis R. Thematic analysis and code development: transforming qualitative information. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications, Inc; 1998.

- Ozawagosh J. Personal conversations. 2020.

- Nabigon H, Hagey R, Webster S, et al. The learning circle as a research method: the trickster and windigo in research. Native Social Work J. 1999;2(1):113–137.

- Nabigon H. The hollow tree: fighting addiction with traditional native healing. Kingston Canada: McGill Queen’s University Press; 2006.

- Vickers JR. Medicine wheel. Alberta Past. 1992;8(3):6–7.

- Menzies P, Bodnar A, Harper V. The role of the elder within a mainstream addiction and mental health hospital: developing an integrated . Native Social Work J. 2010;7:87–107.

- Menzies P. Intergenerational trauma. In: Menzies P, Lavallee L, editors. Aboriginal people with addiction and mental health issues: what health, social service and justice workers need to know. Toronto: CAMH Publications; 2014. p. 61–72.

- Tousignant M, Sioui N. Resilience and aboriginal communities in crisis: theory and interventions. J Aborig Health. 2009;5(1):43–61.

- Crow F, Mails TE, Means R. Fools crow: wisdom and power. Chicago, IL: Council Oak Books; 2001.

- Najavits LM. Seeking safety: an evidence-based for trauma/PTSD and substance use disorder. In: Witkiewitz K, Marlatt GA, editors. Therapist’s guide to evidence-based relapse prevention. San Diego (CA): Elsevier; 2007. p. 141–167.

- Najavits LM, Hein D. Helping vulnerable populations: a comprehensive review of the treatment outcome literature on substance use disorder and PTSD. J Clin Psychol. 2013;69(5):433–479.

- Kirmayer LJ, Tait CL, Simpson C. The mental health of Aboriginal peoples in Canada: transformations of identity and community. In: Kirmayer LJ, Valaskakis GG, editors. Healing traditions: the mental health of Aboriginal peoples in Canada. Vancouver Canada: University of British Columbia; 2009. p. 3–35.

- Linklater R. Decolonizing our spirits: cultural knowledge and indigenous healing. In: Marcos S, editor. Women and Indigenous religions. Santa Barbara CA: Praeger; 2010. p. 217–232.

- Macaulay AC. Improving Aboriginal health: how can health care professionals contribute? Can Family Physician. 2009;55: 334–336. Available from: http://www.cfp.ca/content/55/4/334.full

- Heart MYHB. Gender differences in the historical trauma response among the Lakota. J Health Social Policy. 1999;10(4):1–21.

- Jane L (2014). Final report urban aboriginal wellbeing, wellness and justice: a Mi’kmaw native friendship centre needs assessment study for creating a collaborative indigenous mental resiliency, addictions and justice strategy.

- Yalom I, Leszcz M. The theory and practice of group psychotherapy. New York: Basic Books; 2005.

- Marsh TN. Enlightenment is letting go! Healing from trauma, addiction, and multiple loss. Bloomington IN: Authorhouse; 2010.

- Hill DM. Traditional medicine and restoration of wellness strategies. J Aborig Health. 2009;5(1):26–42.

- Kovach M. Indigenous methodologies: characteristics, conversations, and contexts. Toronto Canada: University of Toronto Press; 2009.

- Nardella A, Falcone G, Giordano G, et al. Suicide and drug and alcohol addiction: self- destructive behaviours. An observational study on clinic hospital population. Eur Psychiatry. 2017;41S:S400.

- Hien DA, Wells EA, Jiang H, et al. Multi-site randomized trial of behavioral interventions for women with co-occurring PTSD and substance use disorders. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2009;77(4):607–619.

- Hien DA, Levin FR, Ruglass LM, et al. Combining Seeking Safety with Sertraline for PTSD and alcohol use disorders: a randomized controlled trial. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2015; Advance online publication. doi:10.1037/a0038719

- Cook JM, Walser RD, Kane V, et al. Dissemination and feasibility of a cognitive-behavioral treatment for substance use disorders and posttraumatic stress disorder in the Veterans Administration. J Psychoactive Drugs. 2006;38(1):89–92.

- Dell CA, Dell DE, Hopkins C. Resiliency and holistic inhalant abuse treatment. J Aborig Health. 2005;2(1):4–13.

- Najavits LM, Weiss RD, Shaw SR, et al. Seeking Safety:Outcome of a new cognitive–behavioral psychotherapy for women with posttraumatic stress disorder and substance dependence. J Trauma Stress. 1998;11(3):98–104.

- Weller LA. Group therapy to treat substance abuse and traumatic symptoms in female veterans. Fed Pract. 2005;27–38.

- Zlotnick C, Johnson J, Najavits LM. Randomized controlled pilot study of cognitive–behavioral therapy in a sample of incarcerated women with substance use disorder and PTSD. Behav Ther. 2009;40(4):325–336.

- Hien DA, Cohen LR, Miele GM, et al. Promising treatments for women with comorbid PTSD and substance use disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161(8):1426–1432.

- Zlotnick C, Najavits LM, Rohsenow DJ. A cognitive–behavioral treatment for incarcerated women with substance use disorder and post traumatic stress disorder: findings from a pilot study. J Substance Abuse Treatment. 2003;25:99–105.

- van der Kolk B. The body keeps the score: mind, brain and body in the transformation of trauma. London UK: Penguin Books; 2015.

- Bartlett C, Marshall M, Marshall A. Two-Eyed Seeing and other lessons learned within a co-learning journey of bringing together indigenous and mainstream knowledges and ways of knowing. Journal of Environmental Studies and Sciences. 2012;2(4):331–340. doi:10.1007/s13412-012-0086-8.

- Ozawagosh F. Personal conversations. 2020.