ABSTRACT

Since time immemorial Alaska Natives (AN) lived and aged well, yet today they experience high rates of illness and lower access to care because of colonisation. Aand this research explores successful ageing from an AN perspective or what it means to achieve “Eldership” in the rural Northwest Alaska. A community-based participatory research approach was used to engage participants at every stage of the research process. Semi-structured interviews were conducted with 16 AN men and 25 women and the interviews were professionally transcribed. Kleinman’s explanatory model served as the foundation of the questionnaire to gain a sense of the beliefs about ageing and guide the thematic analysis to establish an AN understanding of successful ageing. The foundation of the Norton Sound southern sub-region Model of Successful Ageing is the reciprocal relationship between Elders and family which enables Elders to access meaningful activities, including Native ways of life, physical health, spirituality, and emotional well-being. Community-based interventions should foster opportunities for Elders to share their Native way of life alongside family and community members, which will enable them to remain physically active, maintain healthy emotional well-being, continue engaging in spiritual practices, and contribute to the health and well-being of families.

Introduction

Ageing is a universal experience, and “older adult” is the only minority group everyone will potentially be a part of; to be alive is to experience ageing. While we have many similar experiences that unite us in the ageing process, how we age – including our beliefs and views about ageing – is grounded in our different lived experiences and is, therefore, unique [Citation1,Citation2]. As the worldwide population, including Indigenous communities, increases in age with longer life expectancy and, consequently, a growingly diverse proportion of older adults [Citation3,Citation4], the cultural nuances of successful ageing become more salient [Citation2]. In response to the many calls to recognise the diversity of successful ageing [Citation5–8], our research offers the first academic data on how Yup’ik and Inupiaq Elders understand and describe successful ageing in the southern sub-region of Norton Sound, Alaska. It is well known that family plays an important role in older Indigenous adults in North America achieving their version of successful ageing [Citation7]. This study contributes to the literature by (a) presenting the findings of the first study of Yup’ik and Inupiaq successful ageing in this region, centring family as the mechanism that enables Yup’ik and Inupiaq Elders to access meaningful activities that support their cultural vision of successful ageing and b) the Elders contribution to promoting successful ageing within their communities (bidirectional contributions).

The term elder takes on much greater significance within Indigenous communities and families. [Citation9],referred to Alaska Native (AN) Elders as Wisdom Keepers, explaining that they are “the repositories of ancient ways and sacred knowledge going back millenniums. They don’t preserve it. They live it” (p. 8]. Similarly, AN Elders are revered and acknowledged as knowledge keepers, community leaders and teachers within their communities [Citation10]. Native people across the state hold their Elders in high regard as the bearers of ceremonial and traditional knowledge that maintains balance [Citation11]. As times change, and traditional cultures give way to the integration of traditional and non-traditional ways, the Elders will continue to bridge the old and new ways of being [Citation12]. This study focuses specifically on those Elders recognised by their community as wisdom and knowledge keepers, and for this reason, the term “elder” is capitalised to differentiate between the AN Elders of Alaska and those who are just considered elderly or older adults [Citation13–15] [Citation12], suggests that the term Elder and the concept of Eldership may continue to hold cultural themes despite the massive changes to traditional cultures by colonisation and acculturation.

Norton sound region of Alaska

The term “Alaska Native” (AN) is an umbrella term that encompasses eleven distinct cultural groups and 229 federally recognised tribes [Bureau of Indian Affairs, n.d.) Mohatt et al. (2005) [Citation16]., noted, “Within each of the groups there is a wide variation in language dialects, acculturation, history of contact with “outsiders”, subsistence practices, migration patterns, religion, and cultural traditions. Thus, any brief description is but a simplification of a very complex and heterogeneous population (p. 265].”

The Norton Sound southern sub-region is located in Northwest Alaska on the coast of the Bering Sea. Approximately the size of West Virginia, the sub-region population was recorded at just 2,304 people between five communities [Citation17], all of which we visited to conduct this study. Over 80% of the five communities are AN, made up primarily of Inupiaq and Central Yup’ik cultural and linguistic groups with unique and partially overlapping cultural practices and traditions [Citation18–20]. Approximately 160 years ago, a group of Inupiat migrated south into the traditionally Yup’ik territory to escape famine and epidemic [Citation21,Citation22]. Today, all the villages in the southern sub-region are mixed Yup’ik and Inupiaq, but Yup’ik make up the majority in the southern half, while Inupiat are the majority in the northern half [Citation21]. The village economies use a hybrid of cash and subsistence with very few formal employment opportunities available. Many residents live traditional lifestyles and rely on bountiful natural resources (i.e. hunting, fishing, greens, and berry picking) as their main source of food (State of Alaska, n. d.).

Literature review

The concept of successful ageing first emerged in the literature more than 60 years ago Rowe and Kahn’s [Citation23,Citation24], but did not gain popularity until [Citation25], Rowe and Kahn’s article in Science. In their article, Rowe and Kahn differentiated between usual ageing, which emphasises typical deficits of ageing, and successful ageing, which highlights exceptional, above-average ageing [Citation25]. Rowe and Kahn presented a model of successful ageing that is the intersection of three components: disease and disability-free, high cognitive and physical functioning, and active engagement with life (1987, 1998). They explain that to age successfully, an older adult must go beyond acceptance of usual ageing by taking an active role in the prevention of typical age-related declines in each of the three component areas. The shortcoming of Rowe and Kahn’s model is the focus on biomedical and individually deterministic factors of ageing, disregarding the importance of holistic factors that impact health as one ages.

To account for the shortcoming of the Rowe and Kahn model [Citation26], some researchers have proposed an expansion of the existing model criteria [Citation14,Citation27–35] to enhance the cultural breadth of this literature. Other researchers have gone further and developed alternative models that expand Rowe and Kahn’s [Citation36], model by including additional elements of successful ageing based on lived experiences of older adults and their subjective experiences. Successful ageing researchers have noted that the inclusion of the older adult perspective in researchers’ definition of successful ageing allows for more meaningful research on successful ageing, as well as improving providers’ ability to offer patient- or elder-centred care [Citation8,Citation37,Citation38]. Furthermore, many cultural differences exist in the way older adults conceptualise successful ageing [Citation5,Citation39,Citation40]** rendering the predominant model of successful ageing ineffective and in some cases contradictory [Citation2] in cross-cultural contexts.

The successful ageing literature has predominantly focused on non-Indigenous populations, emphasising independence and functionality [Citation12,Citation41,Citation42]. As this field continues to expand and become more prevalent with the growing older adult population worldwide, it will be important to include the perspectives of the Elders to have a better understanding of the ageing process and how Elders live their later years in optimal health and well-being.

The study of successful ageing with Indigenous populations in North America is early in its development with approximately 21 papers focused on the topic among North American Indigenous populations [see Citation7, for review]. The studies available have employed qualitative methodology including a single case study, focus group discussions, and individual interviews. The qualitative approach is an appropriate start for studying a little-known phenomenon; however, the small sample sizes severely limit the generalisability of the findings. Pace and Grenier (2017) [Citation7], attempted to consolidate the findings of 12 identified Indigenous ageing studies to suggest a unifying model of successful ageing. While this is an excellent start to a foundation of successful ageing literature with Indigenous populations, there are still many areas to explore and understand within each of North America’s unique Indigenous cultural groups. Similarly, a recent review of Indigenous successful ageing literature revealed the limited availability of studies and initial evidence of existing differences between Indigenous and Western understandings of successful ageing [Citation4], yet the extant literature still lacks comprehensive inquiries to generalise findings or outline specific factors that may vary between different Indigenous understandings of ageing well. The results of Collings [Citation12], study suggest a possible gender difference in views of ageing. Baskin and Davey’s [Citation43] findings illuminate possible differences in rural and urban Indigenous peoples’ attitudes towards and beliefs about ageing as well as the contribution of independent, group, and institutional living environments to ageing.

Initial AN successful ageing research in the Bristol Bay region of Alaska identified four characteristics of successfully ageing Elders, including spirituality, emotional well-being, physical health, and community engagement, which are intertwined with an optimistic perspective and the spirit of generativity [Citation44,Citation45]**. Elders enjoy staying active and participating in traditional cultural activities, eating Native foods, and engaging with family and community. These findings are specific to this culturally-distinct region of Alaska and it is currently unclear whether additional factors influence successful ageing in other regions of Alaska or if the factors interact differently with one another. Despite a tendency to lump AN people into one category combining Northern Indigenous people into Alaska Native and American Indians with no distinctions or identifying AN people as one homogenous group, Indigenous scholars have pointed to the necessity to be more culture specific. Each cultural group consists of a distinct geographical location, culture, governance, and history [Citation46], which contributes to the unique circumstances within each group. Our understanding of what it means to age successfully as an AN Elder is growing; however, only a small sample of the diverse AN population is represented in the literature so far. As evidenced in this brief discussion on AN successful ageing, there is a need for further scholarship in other regions of Alaska to investigate successful ageing within the distinct cultural groups to expand upon [Citation14],successful ageing model [see Citation14] and Lewis’s 2014 reciprocal relationship model [see Citation47 Citation48].

This study used a qualitative approach to explore the depth of the construct as understood and experienced by the Elders of this region providing a first and comprehensive picture of the characteristics of successful ageing or having achieved Eldership. More specifically, this article highlights the experiences of Yup’ik and Inupiaq Elders who have attained “Eldership” in the five participating communities of the Norton Sound southern sub-region and the experiences of ageing in rural Alaska. The findings of this study add to the Indigenous successful ageing literature, contribute to the developing model of AN successful ageing for the Norton Sound region of Alaska, highlight the importance of family engagement in Elders’ ability to age successfully, and most importantly, call attention to the unexpected positive outcomes on family members who support their Elders to age successfully. Our reciprocal relationship model uniquely demonstrates how Elders rely on family to access healthy ageing activities (emotional wellbeing, Native ways of life, physical health, and spirituality), and in doing so, Elders contribute knowledge, time, and support to their family. This reciprocal relationship between Elders and family supports the health of Elders, families, and larger communities, and has implications for informing healthcare best practice.

Design and methods

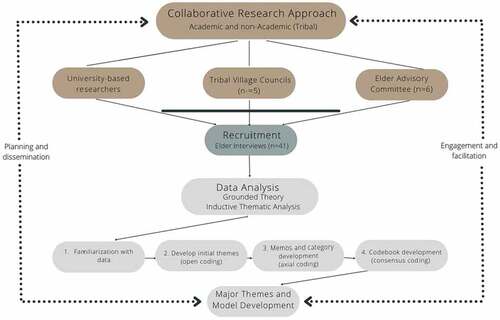

A long-term relationship between the researchers and people of this region has led to their interest in successful ageing and the participation of several communities in this study. Gaining the perspective of AN Elders and working collaboratively with each participating community represents a CBPR approach. outlines the Elder-driven CBPR approach used within this study including the research team collaborators and data analysis. There are eight key principles of CBPR: (a) recognises community as a unit of identity; (b) builds on strengths and resources within the community; (c) facilitates collaborative partnerships in all phases of the research; (d) integrates knowledge and action for the mutual benefit of all partners; (e) promotes co-learning and empowering processes that attend to social inequalities; (f) involves a cyclical and iterative process; (g) addresses holistic well-being and the social determinants of health; and (h) disseminates findings and knowledge gained to all partners [Citation49, Citation50**, Citation51, Citation52]. These principles can be reviewed in other publications by Lewis and colleagues [e.g. Lewis & Boyd, [Citation53]] as well as work by Fisher and Ball (2003) [Citation54].

The CBPR approach has served as the foundation of this research since Lewis conducted his dissertation research in the Bristol Bay region of Alaska that explored successful ageing with Alaska Native Elders [Citation14, Citation47]. Using this methodology, in 2018 we established an Elder Advisory Committee (EAC) consisting of Elders who reside within this region to assist us with gaining permission and creating culturally compatible methods of collecting, analysing, and disseminating research findings to participating communities [Citation54]. This process involved establishing trust with community leaders and Elders to involve them in the research process as equal partners, sharing preliminary findings, and asking for input during community presentations [Citation55]. Data collection occurred from spring 2018 to fall 2019.

This study was a three-year National Science Foundation-funded qualitative investigation of successful ageing in the Norton Sound southern sub-region of Alaska. This project was approved by the University of Alaska Anchorage and the Alaska Area IRB Review Boards, the regional Norton Sound Health Corporation Research Review Board, and tribal village councils. Tribal councils, Elder Care coordinators, and the EAC from the Norton Sound southern sub-region guided community connections and relationship building between the villages and the research team. Before disseminating data to communities, Elders, Norton Sound Health Corporation, and the public we received tribal approvals.

Participant recruitment and participant’s characteristics

Participants for this study self-identified as an AN resident of one of the five remote communities in the Norton Sound southern sub-region participating and were identified and nominated by their respective community members as an Elder. The names of the rural communities are not shared for participant confidentiality requested by the communities. For this study, no age minimum was specified to preserve the local understanding and conceptualisation of Elder. The President of the Tribal Council (or someone designated the President) served as a representative for the community to provide nominations. The community representative navigated first contact with the Elders, summarised the study and its goals, and indicated which places were appropriate for meeting the Elder.

Participants

For this study, 41 Inupiaq and Yup’ik Elders were interviewed. Participants ranged in age from 60 to 92 years and the mean age was 76 years old. Fifteen Elders in this study are widowed (13 women, 2 men), 17 are currently married, three reported being single and two were separated. Of the 41 Elders in this study, eleven participants listed Inupiaq as their first language, and 12 listed Yup’ik as their first language. Regarding education, seven participants completed some elementary or junior high school, 17 participants had some high-school education, 12 Elders graduated from high school, three Elders received their high school Graduate Equivalency Degree (GED), eight participants completed some college, and two graduated from college. Four Elders received their GED later in their lives and two Elders had taken some college courses but had not completed a college degree. The Elders’ household size ranged from living alone to 13 people living in their home, the average household size being seven, reflective of increased household density within Indigenous communities [Citation4,Citation56–58]

Data collection

Semi-structured interviews lasted approximately 60 to 90 minutes involving written informed consent, informing Elders about the goals, risks, benefits, and implications of the study. The locations of each interview depended on the communities’ preferences, with some communities offering available community spaces and others identifying the Elder’s home as appropriate meeting place. Researchers emphasised the Elder’s ability to withdraw or decline answering questions they would like to skip or not answer. None of the Elders refused to have the interview recorded, discontinue the interview, or skip any questions. Interviews were recorded once consent was provided. A demographic questionnaire inquired about cultural background, household size, the time lived in the community, and where participants would like to grow old. After the consent and demographic questionnaire were complete, the researchers followed the interview guide to conduct the interview (Appendix B). Participants received a $60 Amazon gift card in appreciation of their time and effort.

Instrument

An explanatory model [Citation59] served as the foundation of the data collection instrument to better understand the phenomenon of successful ageing. Arthur Kleinman used the term explanatory model (EM) to theorise and investigate that the patient and healer may have very different understandings of the nature of the illness, its cause, and its treatment. EM contain explanations of any or all of five issues: aetiology, the onset of symptoms, pathophysiology, course of sickness, and treatment [Citation59]. Kleinman’s, original approach to EM involved asking questions through an exploratory process of qualitative enquiry. He believed that obtaining the patient’s view of the world and of his or her illness within that world gives rise to a better understanding of the illness, including its perceived meaning within a certain culture or society.

Kleinman’s original concepts, which examined health and sickness from an anthropological perspective, formed the basis of the semi-structured interview guide developed to investigate successful ageing. Kleinman explains one approach to understanding health and illness is to learn about Indigenous systems of healing and EM, which are often distinct within cultural groups. This understanding of the person’s experience can be achieved before attempts are made to connect diagnostic categories to related care pathways [Citation60]. The subjects are encouraged to talk openly about their attitudes and experiences with the aim of eliciting concepts held and their relationships to current situations and culture [Citation26]. EM can be defined as cultural knowledge, beliefs, and attitudes with respect to a particular illness or other aspect of health; they also contribute to research with emic perspectives of illness and elicit local cultural perspectives on sickness episodes [Citation26].

Fifteen questions covered topics such as how AN Elders would define successful ageing, how their ageing process affects their physical, spiritual, and emotional well-being, as well as whether they believe their community is supportive of them ageing successfully (Appendix B). To tailor our interview questions to the unique culture of the region, we worked closely with our Elder Advisory Council to edit the interview guide used by our team on other AN studies (Appendix A) to create a new interview guide (Appendix B) that is culturally specific and collects the type of data requested by the communities.

Data analysis

All recorded interviews were professionally transcribed verbatim by VerbaLink resulting in approximately 800 pages of interview transcripts. Once de-identified and checked for accuracy by the research team, transcripts were uploaded to the qualitative data analysis software NVivo (https://www. qsrinternational.com/nvivo/home) and then analysed using thematic analysis [Citation61,Citation62]. To identify, analyse, and report themes in the data, the three authors used six phases of thematic analysis as shown in [Citation61,Citation62].

Table 1: Community-based Thematic Analysis Process

For the first phase, the first two authors and a graduate research assistant read through each of the transcripts to create memos with initial thoughts and summaries. Second, the first two authors and the graduate research assistant coded every 5th transcript based on the adapted EM questions to establish the first draft of the codebook. Codes were derived inductively and deductively [Citation62] and when they occurred in the majority of transcripts. Third, after reviewing and discussing the codes and definitions, Lewis and Kim and the graduate research assistant coded all the transcripts and consulted with one another when any questions or inconsistencies arose in code definition and application, resulting in the final codebook with 19 codes. Examples of initial codes consisted of “becoming an Elder”, “knowing how to age”, “housing challenges”, “observed changes in lifestyle”, “Native way of life”, and “the impact of education”. Throughout the process, team members practiced reflexivity [Citation61], and one team member, who is an Alaska Native researcher, checked in regularly to discuss theme development. Fourth, the team refined the themes at two levels: data within the themes and themes within the entire data set. This process involved the use of tables aiding the visualisation of conceptual relationships and resulted in the establishment of four major themes, determined by frequency and relevance to the research question. Fifth, the team, in conjunction with the senior author, an experienced qualitative researcher and gerontologist, generated subthemes and produced definitions and analyses for each theme. We shared the preliminary findings with the Elder Advisory Committee that included each theme, the definition, examples of the theme within the data, and a summary of our overall analyses. We solicited their input and recommendations and ensured appropriate representation of the Elders’ perspectives, which included confirmation of our findings and recommendations on how to effectively disseminate the findings to be accessible to all ages. In this process of analysis, credibility was enhanced through the review process among the research team members and presenting preliminary findings to the Elder Advisory Committee that included each theme, the corresponding definition, and examples of the themes within the data; we welcomed their input and recommendations and further refined the themes based on their feedback [also considered member checking [Citation63].

Findings

Five major themes emerged that define successful ageing in Northwest Alaska, each of which highlighted important aspects of successful ageing or ageing in a good way. These themes define Eldership in the Norton Sound southern sub-region: (a) family, (b) emotional well-being, (c) Native way of life, (d) physical health, and (e) spirituality. Family emerged as a theme that was woven throughout the other four themes and enabled the Elders to ensure their emotional well-being, continue to live the Native way of life, maintain their physical health, and have spirituality in their lives. The following paragraphs describe each theme.

Family

The foundation of the Norton Sound southern sub-region Model of Successful Ageing is Family. Family members, immediate, extended, and fictive (non-blood related) kin, play a critical role in Elders’ ability to age successfully. Through this circular process, older family members initially contribute to a young child’s knowledge of what it means to be an Elder until the person’s experiences, observations, and knowledge gathered over a lifetime lead to the process of becoming an Elder themselves.

Within their own families, Elders referred to their grandparents and older family members as resources and role models from which they learned to be an Elder, including roles, stories, traditional lifestyle, survival skills, and history. Their parents were often remembered as ‘hard-working” with great endurance. An Elder remembered, his mother teaching him about “camping and fishing, berry picking, sewing baskets, and sewing parkas for the kids, cut fish and put food away for the winter, cooking”, while he recalled his father as a “reindeer herder, [who] traveled through the flats all winter long, taught us hunting and carving, [and] told stories about his parents”. Similarly, another Elder describes his parents, “In the past, I used to see my dad and mom do a lot of crafts with their hands and they traded whatever was needed for at home, mainly nets and a little bit of grub like flour, sugar, items that are needed”.

Many participants voiced actively supporting their families by watching over the children, providing parenting support, or adopting grandchildren. Most Elders identified these relationships as mutual, involving children and grandchildren helping financially, sending groceries, sharing the hunt, or assisting with household chores. Having family support contributes to the Elders’ emotional well-being, their ability to be involved in community activities, opportunities to pass on their teachings, as well as keep them active in subsistence activities (berry picking, fishing, arts and crafts). All these activities provide the Elders ways to pass on cultural values and practices learned from their Elders and teach the Native way of life to youth so they can become healthy Native people.

Spending time with family is seen as encouraging the younger generation to age well by offering opportunities for observing “what we are doing or what we are teaching them through our actions or work, they’re able to see what we do [… }”. Throughout those times, Elders will pass on their knowledge, offer advice, and offer unconditional love. Seeing family members do well improves the Elder’s well-being as indicated by this Elder’s statement, “When your children do well … it makes you happy”. By contributing to the family in the described ways the Elders close the cycle of learning by being role models for the next generation (generativity).

For Elders in this region, the role of family members enables them to maintain emotional well-being, participate in Indigenous cultural generative activities and maintain a spiritual presence in their lives. When Elders participate in these activities they are seen as respected “Elders”, or having achieved “Eldership”.

The following sections discuss the four additional themes and how family contributes to these themes.

Emotional well-being

Alaska Native Elders designated three main areas contributing to emotional well-being: positive family relationships, physical and mental health, and community engagement.

A vital factor of emotional well-being is family relationships and the support provided by family members. Being able to age surrounded by their family in the home and community where Elders were raised is associated with positive emotions and longer life. The importance of family involvement was a key factor spanning spending time together with family, engaging in subsistence activities, and spending time on the land with family. An Elder shared with us, “I have a lot of nieces, grandnephews, grandnieces that hunt and they come to share their food, yeah, and we bake for them, or I knit a lot too and sew, so we try to repay them. Yeah, it’s … It makes me feel special”.

The emotional well-being of Elders was seen because of mental health, which was supported and facilitated through optimism, happiness, acceptance, enjoyment, feeling good, or gratitude. Elders voiced, “Think young and stay active as much as you can. Don’t follow how you feel. Another Elder shared, “You need to think positive. Try to enjoy life every day. Take each day as it comes, as a blessing, and try to be happy every day. Even when we have a death in the family, they encourage us to try to be positive and happy, not to focus too much on grief”. Elders highlighted the importance of keeping their bodies and minds healthy, including having a positive outlook on life, being reflective on life experiences and lessons learned, as well as maintaining positive relationships with family. An Elder noted, “Just do things that keep you healthier. If your body is healthy and your mind is healthy, you can generally age much better”. An Elder in a neighbouring community shared how successful ageing is a state of mind and that your mind can impact how your body feels. They advised, “To me, aging well is a state of mind. When you’re happy in here and in your heart when you know that people care about you, that I consider that you have aged well”.

In the presence of physical limitations, several Elders emphasised the importance of family, a healthy mind, and positive thought. As an Elder shared “You can’t think old, I think. You have to think young. I think our adopted son made a lot of difference for us, too. He keeps us moving, exercising”. Another Elder shared the following, “Just use your mind to go somewhere else where you used to go ’cause you can’t go out there anymore”. A positive attitude was emphasised as a critical factor in coping with past and current struggles as well as supporting ageing well.

Family, positive relations, and mutual support were necessary for the Elder’s emotional well-being and mental health. Family provides the main structure to support the Elder in purposefully and meaningfully ways needed to age successfully, including socialising, opportunities to share and teach the next generation of Alaska Native Elders, being provided the opportunity to engage intergenerationally. Most of the shared time involve learning, teaching, and engaging in Native ways of life that have been shared for generations.

Native ways of life (generativity)

Traditional Native ways are vital to an Elder’s life. These traditional ways were being passed down by Elders to family and the community, centring Elders between their ancestors and future generations. One Elder shared, “They pass down things to you and you’ve got to pass it on down to your kids, everything you learned. You could have a college degree, but where you learn is your home. That’s where you first start, from you, your parents, grandparents, and elders. You pass that on”. Another Elder shared, “An Elder spoke to me about the beliefs that we have, the meaning of it. So, each different Elder gave me some knowledge that I used in my lifetime. There are guidelines I share with others on how to be Elders”. In addition to sharing their knowledge, they emphasised the importance of teaching their Native ways of life, which included subsistence activities.

Harvesting, gathering, and preparing traditional foods was one of the most common things shared by the Elders with their children and other youth. Elders not only discussed the positive feelings they experienced through gathering, sharing, and eating traditional foods, but they also emphasised the importance of passing this knowledge to youth to ensure they continue harvesting and having pride in these practices. One Elder noted, “I feel happy and proud because we have the subsisting life as a part of our culture. Be proud of it so the youth can be proud of it”. Subsistence-related activities involve staying at fish or berry camps, hunting, fishing, and harvesting greens and berries. Subsistence not only provides people with healthy foods, but also promotes successful ageing through the engagement of mind, body, and spirit. This active lifestyle spans activities from walking, hiking, climbing, gardening, and camping to community involvement, visiting, and sharing foods. Traditional values include avoiding waste and sharing foods, especially with Elders.

When Elders described sharing knowledge about Native ways of life, they often described sharing with children and grandchildren, centralising family. One Elder shared the reciprocal relationship of teaching their children how to hunt and gather and reaping the benefits of those teachings as an Elder. They stated, “When my children were younger and we’d go out hunting, I’d show them what to do. Now, they do all the hard work and I give them pointers and advice. The thing is my children try to make sure I have an easy time with them out there in the country. That’s one of the benefits of my family”. Not only were subsistence activities important for their diet and bringing family together but kept Elders and others physically active.

Physical health

The understanding of physical health is intricately interwoven into the adherence to traditional practices and the role of family in achieving good health. Elders underlined the role of family by saying “The family life you have” impacts how you age. Many Elders expressed how vital it is for the Elder to teach their children and grandchildren about healthy ways of living. One Elder shared, “And my kids, we try to show them, especially the grandkids, to take care of your body, to eat the right subsistent food”. The involvement with family was mentioned frequently as one of the health-promoting factors, for example, “I’d say just eat well, exercise, help with the family”.

The importance of taking a holistic approach to health was expressed by many Elders, voicing, “So aging well, you take care of yourself and your family and your surroundings Elders agreed the Native ways of life (walking, subsistence activities, and arts and crafts), subsistence foods, and access to health care services were beneficial for good health”. An Elder outlined, “I would tell them to keep moving and not just stay still. I want to encourage them to continue to do subsisting and eating subsistence foods as much as they can and not to rely on store-bought stuff all the time”. While physical health is important to Elders, it is not essential to successful ageing.

Elders manage challenges presented by physical decline through positive mindsets, family support, and emotional well-being. In the words of one Elder, “I have medical issues that prevent me from doing stuff, but I work through it and do the best I can of trying to live every day as happy as possible”. Concomitantly, Elders utilise the local healthcare system to address physical age-related changes to engage in regular health check-ups. This Elder recognised the necessity for medical care by sharing, “To stay healthy, and if they’re sick, go to clinic and tell the health aide or PA and follow whatever they tell them … to follow their rule … ”

Spirituality

Religious or spiritual beliefs were helpful for Elders in accepting and managing health challenges. One Elder shared, “you’ve got to believe, whether it’s God or a higher power or in other people”. Prayer is also a source of strength, power, and acceptance. Through the strength of prayer, Elders overcame physical challenges and stayed positive. One Elder shared, “The other thing is religion, to have God in your life, to be able to – because you need someone you can turn to when you’re having a difficult time”. Another Elder shared, “Despite tragedies life goes on. I think the prayers and best wishes of other people impact each individually big time. And to age well – you don’t dwell on the hurt and pray”. In addition to offering support, guidance, and reflection, spirituality connects Elders with their community through church activities, social engagement, and contributions.

Prayer, spiritual beliefs, and traditional spiritual practices were practiced by older family members and shared with children and grandchildren. Seeing their family benefit from and participate in spiritual activities helped Elders to feel good. Prayer was often used to help overcome tragedies within families. This Elder described, “I used to feel really bad for my daughter when she becomes a widow and she was two months pregnant and I used to – I pray for her – and I used to say to myself, it must be – her husband died before my husband – I used to say it must be so hard to be a widow when you’re so young, you know?” Being involved in spiritual practices, such as singing and drumming, with the community provides strength and positivity, as well as the opportunity for generative engagement. This Elder explained the role of spirituality in ageing, “For him and I, I think we’re strong and we’re aging well. It’s because we still have our values and beliefs that were taught to us by our elders and our parents when we were growing up, and having a belief in God, having chosen our religion and it not being forced on us”.

Spiritual practices and beliefs are an important part of families that is being taught from one generation to the next providing strength, support, emotional balance, and the ability to accept and overcome hardships.

Discussion of Findings

The foundation of the Norton Sound southern sub-region Model of Successful Ageing is Family. The family contributes to Elders’ abilities to engage in the four other components described in the results section: emotional well-being, Native ways of life, physical health, and spirituality. Family supports these four components in interconnected and multifaceted ways.

At the core, Elders have a reciprocal relationship with their families [Citation47]. On one hand, family provides physical, social, and emotional support. Support from family enables Elders to access spirituality, physical health, and Native ways of life such as subsistence activities and traditional arts. On the other hand, Elders provide family with traditional teachings through generative acts and behaviours [Citation44]. Sharing knowledge gives Elders a culturally significant role, centralising them between the ancestors of the past and generations of the future, enabling Elders to age in Indigenous cultural generative acts [Citation64]. It also provides younger generations with essential cultural and spiritual knowledge. These generative acts support family well-being and largescale family well-being for generations to come. At the core of all the factors that support successful ageing – Native ways, physical health, spirituality, and emotional well-being – is the reciprocal relationship between Elders and their family.

The reciprocal relationship of Elders and family exists within the context of meaningful engagement: spiritual activities and Native ways of living. These activities span crafts, gathering food, and being on the land. At some point, most older Elders rely on family to help them access these activities. At the same time, these activities provide opportunities for Elders to pass on cultural values and practices they learned from their Elders, teach the Native way of life, and model how to be healthy Native people for their family and others. These activities support Elders’ emotional well-being and physical health, leading to Eldership, or ageing in a good way. The activities also support the well-being of the entire family for generations to come.

Much of the successful ageing literature emphasises the individual’s control over their ability to age successfully through decision-making and behavioural changes [Citation25], in which older adults are believed to age successfully due to their individual choices and actions [Citation65], and less focus on the contributing factors of other factors to our ability to age successfully, such as family and societal supports [Citation8,Citation66]. The unique findings of our study on the centralisation of family contribute to the larger discourse on individualism versus familism in non-Western ageing. In Singapore, where the “East meets West”, Feng and Straughen [2016) found that elderly women emphasise familism as contributing to successful ageing despite the dominant Western narrative of individualism and independent ageing. In Korea, [Citation67], found a similar persistence of family roles in successful ageing that is distinct from the Western narrative. Among Indigenous older adults of North America, Citation7,found that older Indigenous adults understand successful ageing to be supported by family, community, and culture more than it is supported by exercise and diet. The emphasis on family within the AN concept of successful ageing is distinct from the dominant Western settler-colonial conceptualisation of healthy ageing.

The more recent inclusion of the voices and lived experiences of older adults from diverse backgrounds into the study of successful ageing demonstrates the heterogeneity of older adults based on gender, health status, and culture [Citation4, Citation68–71] [Citation72]**. Studies within Eastern cultures established that family support plays a unique role in one’s ability to age successfully [Citation66]. Likewise, Indigenous successful ageing studies outline the holistic concept of health and the interconnection of land, spirituality, environment, ideological, political, social, economic, mental, and physical factors as contributors to good health [Citation14,Citation22,Citation73]. Quigley and colleagues [Citation4] emphasise the role of family in the health of older Indigenous adults by demonstrating the significance of those two aspects in the Indigenous concept of ageing within each domain as a promoting factor for ageing well. Similarly, our study highlights how family contributes to the health and well-being of Inupiat and Yupik Elders. While family supports ageing well within AN people of all ages [Citation74] this study provides additional support and details the continued importance of family in the Elders’ ability to age successfully and remain in their homes within this arctic region of Alaska. Family support enabled Elders in this study to maintain their physical health, emotional well-being, be engaged in their community, and participate in their Native ways of life, including participating in cultural and spiritual activities, engaging in hunting and gathering activities, sharing their knowledge and stories, and spending time with family.

Lewis’s earlier AN model of successful ageing outlined four main themes of successful ageing, emotional well-being, physical health, spirituality, and community engagement based on Elder’s lived experiences in the Bristol Bay region of Alaska [Citation14]. This study reinforces the relevance of those four themes to successful ageing within AN communities broadly and the unique region of the Norton Sound southern sub-region. Our study introduces a new centralisation of family facilitating and supporting Elders in their well-being through community engagement, generative activities, and varying levels and types of support. While the family is always considered a vital component within AN ageing [Citation74], the central role of the family in enabling Elders to age well within their home community was highlighted in the interviews with the Elders of this region [Citation22,Citation73]. Specifically, family plays a vital role in ensuring survival within the arctic harsh climate. Augmented by the remoteness of communities, limited access to modern amenities, and high reliance on subsistence foods, Elders reported on the necessity of their family’s support to age well and the Elder’s role to share their knowledge with their families. These findings contribute to the growing importance of family domains as leading factors to successful ageing than biomedical perspectives [Citation65,Citation66].

It is well known that family plays an important role in older Indigenous adults in North America achieving their version of successful ageing [Citation7], but our study is unique because it centralises family as the mechanism that enables Elders to participate in other meaningful activities which together promote the Elders’ version of successful ageing. Therefore, this study contributes to the literature by (a) presenting the findings of the first study of AN successful ageing in the Norton Sound region, and (b) developing a model that uniquely centres on family exemplifying regional, geographical, and cultural differences [Citation75]. Family contributes to successful ageing for AN Elders and when we think about biomedical models of health, and health research in the Arctic, there is a paucity of research focused on family impacts on health outcomes. With the social, cultural, environmental, and political changes in the Arctic and climate refugees due to climate change, if family is a critical part of successful ageing in the Arctic, we need to think of innovative solutions to keep families engaged for the health of the Elders, but also the health of the families and their future healthy ageing. The unique findings also contribute to scholarly efforts to decentralise physical health within the dominant successful ageing model. This decentralisation of physical health was found in other studies on the subjective views of successful ageing of both Indigenous Elders [Author, 2019; Citation7, Citation12] and non-Indigenous older adults [Citation76]. In our study, Elders adapted to physical changes by relying on family support, accessing healthcare, adopting positive mindsets [Citation77,Citation78], and pursuing activities like gathering traditional foods and spending time on the land. However, they also associated these adaptive techniques with more than just physical health, crediting them with also creating emotional well-being through family, community, and cultural connections. Emotional well-being is also supported by involvement with the Church and spirituality rooted in a connection to land and place.

The themes highlighted in our study are like other determinants of successful ageing proposed in extant theories of successful ageing, specifically those developed through lay perspectives of successful ageing [Citation79]. For example, physical and emotional health represent two of the three components of Rowe and Kahn’s [Citation36] model, and the Native way of life could be like the third component, engagement with life. However, our participants understand successful ageing to be more than health and activity, and that culture, spirituality, and family engagement are critical aspects of successful ageing.

As we think about successful ageing and growing old in a good way, the findings of the study encourage health care workers, Tribal and community leaders, and policymakers to place more focus on supporting families who care for the Elders. This can be done through establishing programmes and services that enable families to support Elder’s physical and emotional well-being, engaging in the Native ways of life [engaging in Indigenous cultural generative acts, see Citation64] and subsistence activities, and participating in spiritual or religious practices. The AN Elders in this study highlighted the importance of their family providing them with a feeling of being needed, engaging in meaningful activities, being generative, and having a sense of purpose beyond themselves.

Based on our findings, family support is vital for an older adult’s ability to age successfully and enables Elders to be actively engaged in community activities. Within the Yup’ik and Inupiat cultures, as well as in other Indigenous groups [Citation4], Elders are revered and acknowledged for their knowledge of past generations, helping sustain future generations [Citation14], and contributing to their family, community, and society. When families support their Elders to age successfully, they are also indirectly benefitting from their engagement with the Elders; they are learning what it means to be an Elder, the history of their family and community, harvesting and gathering subsistence foods, and how to be a healthy Native person. This bidirectional contribution to community and family establishes a society that values ageing and limits ageism, shifting the Western paradigm that ageing is associated with loss and a stage of life to fear to a view of Elder as a stage in life to be embraced and honoured. Centering contributions of older adults within the Western culture may also lead to positive views related to ageing, improving the health and well-being of older adults [Citation80] The initial successful ageing model [Citation14] identified elements of Eldership (successfully ageing Elders) based on lived experiences of Elders in the Bristol Bay region of Alaska as emotional well-being, community engagement, spirituality, and physical health. The findings of this study build upon the 2011 model, resulting in a new model of successful ageing that emphasises the social components of ageing, specifically the important role of family engagement at the foundation of this model of successful ageing. The findings of this study emphasise the importance of both individual and social influences on successful ageing. The Elders in our study often relied on family to engage in social, cultural, and environmental activities that were important in their subjective understanding of successful ageing. Community interventions should foster opportunities for Elders to share their Native way of life alongside their family and community members, which will enable them to remain physically active, have healthy emotional well-being, opportunities to engage in spiritual practices, and contribute to the health and well-being of their family and community. These interventions may focus on elder care programmes that can support families and communities in the care for their Elders and explore how to weave together both subjective and biomedical models of successful ageing to support Elders to age successfully [Citation81]. Intergenerational gatherings within communities can deliver opportunities for sharing between the generations. This study also contributes to regional and cultural differences within the study of successful ageing outlining similarities and differences that need to be acknowledged when local interventions and policy changes are considered.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Tam M. Understanding and theorizing the role of culture in the conceptualizations of successful aging and lifelong learning. Educat Gerontol. 2014;40(12):1–14.

- Torres S. A culturally-relevant theoretical framework for the study of successful ageing. Ageing Soc. 1999;19(1):33–51.

- Howell D. Alaska population projections 2012 to 2042. Alaska Econ Trends. 2014;34(6):4–9. 07/30/2022. Retrieved fromhttp://labor.alaska.gov/trends/jun14.pdf

- Quigley R, Russell SG, Larkins S, et al. Aging well for indigenous peoples: a scoping review. Front Public Health. 2022;10:780898.

- Laditka SB, Corwin SJ, Laditka JN, et al. Attitudes about aging well among a diverse group of older Americans: implications for promoting cognitive health. Gerontologist. 2009;49(S1):S30–S39.

- Martinson M, Berridge C. Successful aging and its discontents: a systematic review of the social gerontology literature. Gerontologist. 2015;55(1):58–69.

- Pace JE, Grenier A. Expanding the circle of knowledge: reconceptualizing successful aging among North American older indigenous peoples. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2017;72(2):248–258.

- Teater B, Chonody J. How do older adults define successful aging? A scoping review. Int J Aging Hum Dev. 2020;91(4):599–625.

- Arden H, Wall S. Wisdomkeepers: meetings with native American spiritual elders. Hillsboro OR: Beyond Words Publishing, Inc; 1990.

- Graves K, Rosich R, Jeste DV, et al. Association between older age and more successful aging: critical role of resilience and depression. Am J Psychiatry. 2013;170(2):188–196.

- Kawagley AO. 2006 . A Yupiaq worldview: apathway to ecology and spirit, 2 (Long Grove, IL: Waveland Press), 92.

- Collings P. “If you got everything, it’s good enough”: perspectives on successful aging in a Canadian Inuit community. J Cross Cult Gerontol. 2001;16(2):127–155.

- Grandbois DM, Sanders GF. The resilience of Native American elders. Issues Ment Health Nurs. 2009;30(9):569–580.

- Lewis JP. Successful aging through the eyes of Alaska native elders. What it means to be an elder in Bristol Bay, AK. Gerontologist. 2011;51(4):540–549.

- Stiegelbauer SM. What is an Elder? What do Elders do?: first Nation Elders as teachers in culture-based urban organizations. Can J Native Stud. 1996;14:37–66.

- Mohatt GV, Hazel KL, Allen J, et al. Unheard Alaska: culturally anchored participatory action research on sobriety with Alaska Natives. Am J Community Psychol. 2004;33(3–4):263–273.

- U.S. Census Bureau (2020). American community survey 5-year estimates. Accessed May 2022.

- Rivkin I, Lopez EDS, Trimble JE, et al. Cultural values, coping, and hope in Yup’ik communities facing rapid cultural change. J Community Psychol. 2019;47(3):611–627.

- Sakakibara C. “Our home is drowning”: Inupiat storytelling and climate change in Point Hope, Alaska. Geog Rev. 2008;98(4):456475.

- Wu F. Modern economic growth, culture, and subjective well-being: evidence from Arctic Alaska. J Happiness Stud. 2020;22(6):2621–2651.

- Bering Straits Native Corporation. About BSNC: history & region. Bering Straits Native Corporation; n.d. https://beringstraits.com/history-region/ 08/16/2022

- Boyd KM (2018 07/20/2022). “We did listen”. Successful aging from the perspective of Alaska Native Elders in Northwest Alaska [ Doctoral dissertation, University of Alaska Fairbanks and Anchorage]. ScholarWorks@UA. https://scholarworks.alaska.edu/handle/11122/8647

- Baker JL. The unsuccessful aged. Journal of American Geriatrics Society. 1958;7:570–572.

- Pressey SL, Simcoe E. Case study comparisons of successful and problem old people. J Gerontol. 1950;5:168–175.

- Rowe JW, Kahn RW. Human aging: usual and successful. Science. 1987;237(4811):143–149.

- Lloyd KR, Jacob KS, Patel V, et al. The development of the short explanatory model interview (SEMI) and its use among primary-care attendees with common mental disorders. Psychol Med. 1998;28:1231–1237.

- Bellingtier JA, Neupert SD. Negative aging attitudes predict greater reactivity to daily stressors in older adults. J Gerontol Ser B. 2016;(1):1–5.

- Blazer DG. Successful aging. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2006;14(1):2–5.

- Bowling A, Iliffe S. Which model of successful aging should be used? Baseline findings from a British longitudinal survey of ageing. Age Ageing. 2006;35(6):607–614.

- Crowther MR, Parker MW, Achenbaum WA, et al. Rowe and Kahn’s model of successful aging revisited: positive spirituality—The forgotten factor. Gerontologist. 2002;42(5):613–620.

- Hill PL, Turiano NA. Purpose in life as a predictor of mortality across adulthood. Psychol Sci. 2014;25(7):1482–1486.

- Jeste DV, Savla GN, Thompson WK, et al. Association between older age and more successful aging: critical role of resilience and depression. Am J Psychiatry. 2013;170(2):188–196.

- Ouwehand C, De Ridder DT, Bensing JM. A review of successful aging models: proposing proactive coping as an important additional strategy. Clin Psychol Rev. 2007;27(8):873–884.

- Parker MW, Bellis JM, Bishop P, et al. A multidisciplinary model of health promotion incorporating spirituality into a successful aging intervention with African American and white elderly groups. Gerontologist. 2002;42(3):406–415.

- Tovel H, Carmel S. Maintaining successful aging: the role of coping patterns and resources. J Happiness Stud. 2014;15(2):255–270.

- Rowe JW, Kahn RW. Successful aging. New York NY: Dell Publishing; 1998.

- Phelan EA, Anderson LA, Lacroix AZ, et al. Older adults’ views of “successful aging”—how do they compare with researchers’ definitions? J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52(2):211–216.

- Rossen EK, Knafl KA, Flood M. Older women’s perceptions of successful aging. Activities Adapt Aging. 2008;32(2):73–88.

- Dillaway HE, Byrnes M. Reconsidering successful aging: a call for renewed and expanded academic critiques and conceptualizations. J Appl Gerontol. 2009;28(6):702–722.

- Levy BR, Slade MD, Kunkel SR, et al. Longevity increased by positive self-perceptions of aging. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2002;83(2):261.

- Lowry KA, Vallejo AN, Studenski SA, Successful aging as a continuum of functional independence: lessons from physical disability models of aging. Aging Dis. 2012 ;3(1):5.

- Reich AJ, Claunch KD, Verdeja MA, et al. What does “successful aging” mean to you? A systematic review and cross-cultural comparison of lay perspectives of older adults in 13 countries, 2010–2020. J Cross Cult Gerontol. 2020;35(4):455–478.

- Baskin C, Davey CJ. Grannies, elders, and friends: aging Aboriginal women in Toronto. J Gerontol Soc Work. 2015;58(1):46–65.

- Lewis JP Reclaiming our identity through indigenous cultural generative acts to improve mental health of all generations. In: Indigenous Knowledge and Mental Health, edition 1. Springer, Cham: Springer Publisher; 2022. p. 181–194.

- Lewis JP. Indigenous cultural generativity: teaching future generations to improve our quality of life. Encycl Gerontol Popul Aging. 2019;1: 1–5.

- Caldwell JY, Davis JD, Du Bois B, et al. Culturally competent research with American Indians and Alaska natives: findings and recommendations of the first symposium of the work group on American Indian research and program evaluation methodology. Am Indian Alaska Native Mental Health Res. 2005;12(1):1–21.

- Lewis JP. What successful aging means to Alaska Natives: exploring the reciprocal relationship between the health and well-being of Alaska Native Elders. Int J Aging Society. 2014;3(1):77–88.

- Brush BL, Mentz G, Jensen M, et al. Success in long-standing community-based participatory research (CBPR) partnerships: a scoping literature review. Health Educ Behav. 2020;47(4):556–568.

- Bureau of Indians Affairs (n.d. 06/20/2022) Alaska region overview. Retrieved from https://www.bia.gov/WhoWeAre/RegionalOffices/Alaska/index.html

- Chilisa B. Indigenous research methodologies. Second ed. New York, NY: SAGE Publications; 2020.

- Collins SE, Clifasefi SL, Stanton J, et al. Community-based participatory research (CBPR): towards equitable involve-ment of community in psychology research. Am Psychol. 2018;73(7):884–898.

- Minkler M, Wallerstein N. Community-based participatory research for health: from process to outcomes. 2nd ed. San Francisco, CA: John Wiley & Sons; 2008.

- Lewis JP, Boyd K (2012). Determined by the Community: CBPR in Alaska Native Communities Building Local Control and Self-Determination. Journal of Indigenous Research: Vol. 1(2), Article 6. Available at: http://digitalcommons.usu.edu/kicjir/vol1/iss2/6

- Fisher PA, Ball TJ. Tribal participatory research: mechanisms of a collaborative model. Am J Community Psychol. 2003;32(3–4):207–216.

- Kovach M. Indigenous methodologies: characteristics, conversations, and contexts. Toronto, Canada: University of Toronto Press; 2009.

- Habibis D, Phillips R, Phibbs P. Housing policy in remote indigenous communities: how politics obstructs good policy. Hous Stud. 2019;34(2):252–271.

- Pindus N. 2017. Urban Institute. USA. Department of Housing and Urban Development. Office of Policy Development and Research. Housing needs of American Indians and Alaska natives in tribal areas: a report from the assessment of American Indian, Alaska native, and native Hawaiian housing needs. Washington D.C;U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, Office of Policy Development and Research

- Riva M, Larsen CVL, Bjerregaard P. Household crowding and psychosocialhealth among Inuit in Greenland. Int J Public Health. 2014;59(5):739–748.

- Kleinman A. Patients and healers in the context of culture. London, England: University of California Press; 1980.

- Bhui K, Bhugra D. Explanatory models for mental distress: implications for clinical practice and research. Br J Psychiatry. 2002;181(1):6–7.

- Braun V, Clarke V. Conceptual and design thinking for thematic analysis. Qual Psychol. 2021;9(1):3–26.

- Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77–101.

- Chapman AL, Hadfield M, Chapman CJ. Qualitative research in healthcare: an introduction to grounded theory using thematic analysis. J R College Physicians Edinburgh. 2015;45(3):201–205.

- Lewis JP, Allen J. Alaska native elders in recovery: linkages between indigenous cultural generativity and sobriety to promote successful aging. J Cross Cultural Gerontol. 2017;32(2):209–222.

- Rubinstein RL, de Medeiros K. “Successful aging”, gerontological theory and neoliberalism: a qualitative critique. Gerontologist. 2015;55(1):34–42.

- Stowe JD, Cooney TM. Examining Rowe and Kahn’s concept of successful aging: importance of taking a life course perspective. Gerontologist. 2015;15(1):43–50.

- Nakagawa T, Cho J, Yeung DY. Successful aging in East Asia: comparison among China, Korea, and Japan. J Gerontol B. 2021;76(Supplement_1):S17–S26.

- Hung LW, Kempen GIJM, De Vries NK. Cross-cultural comparison between academic and lay views of healthy ageing: a literature review. Ageing Soc. 2010;30(8):1373–1391.

- Martin P, Kelly N, Kahana B, et al. Defining successful aging: a tangible or elusive concept? Gerontologist. 2015;55(1):14–25.

- McCann Mortimer P, Ward L, Winefield H. Successful ageing by whose definition? Views of older, spiritually affiliated women. Australas J Ageing. 2008;27(4):200–204.

- Shooshtari S, Menec V, Swift A, et al. Exploring ethno-cultural variations in how older Canadians define healthy aging: the Canadian Longitudinal Study on Aging (CLSA). J Aging Stud. 2020;52:100834.

- State of Alaska (n.d. 07/20/2022) Department of Commerce, community, and economic development, community and regional affairs. Retrieved from https://www.commerce.alaska.gov/dcra/dcraexternal/xommunity/

- Kim S. We’re an adaptable people:” resilience in the context of successful aging in Urban dwelling Alaska native elders (doctoral dissertation. Anchorage, AK: University of Alaska Anchorage; 2020.

- Crouch MC, Skan J, David EJR, et al. Indigenizing quality of life: the goodness of life for every Alaska native research study. Appl Res Qual Life. 2021;16(3):1123–1143.

- Brooks-Cleator L, Giles A. indigenous older adults’ perspectives on aging well in an urban community in Canada. Innovation Aging. 2018;2(suppl_1):175.

- Tkatch R, Musich S, MacLeod S A qualitative study to examine older adults' perceptions of health: Keys to aging successfully, et al. 2017. Geriatric nursing;38(6); 485–490

- Brooks-Cleator L, Lewis JP. Alaska native elders’ perspectives on physical activity and successful aging. Can J Aging/La Revue Canadienne Due Vieillssement. 2020;39:294–304.

- Lewis JP. the importance of optimism in maintaining healthy aging in rural Alaska. Qual Health Res. 2013;23(11):1521–1527.

- Jopp DS, Wozniak D, Damarin AK, et al. How could lay perspectives on successful aging complement scientific theory? Findings from a U.S. and a German life-span sample. Gerontologist. 2015;55(1):91–106.

- Jung MH, Moon JS. A study on the effect of beauty service of the elderly on successful ageing: focused on mediated effect of self-esteem. J Asian Finance Econ Bus. 2018;5(4):213–223.

- Cosco TD, Prina AM, Perales J, et al. Lay perspectives of successful ageing: a systematic review and meta-ethnography. Br Med J Open. 2013;3:1–9.

Appendix A

Explanatory Model Successful Ageing Questionnaire

Participant ID #: _________________

Date: ___________________________

1. At what age do you think that a person becomes an elder in your community?

2. How do you know if someone is regarded as an elder or not?

3. Is there anything that happens to mark this transition?

4. Do you think things have changed for elders these days, as opposed to say, 20 years ago? If so, in what ways? (Probe different comments by participant).

5. What do you think successful ageing means?

6. Why do some Elders age well and some do not?

7. What are the signs of an Elder who is ageing well? For example, can you think of someone in this community who is ageing really well? (Allow a response, and then follow up with: How can you tell they are ageing well, as opposed to someone who is not?)

8. What are some of the signs, or symptoms, of poor ageing? Or unhealthy ageing?

9. Can poor ageing be prevented?

a. If yes, what can people do to prevent poor ageing?

b. What does a person need to do to age well? (Is doing the same as being?)

10. Do you think there are differences in how people age when it comes to living an urban community versus a rural community? How so?

a. Why do you think this/these difference(s) exist? (if applicable).

11. What role do you think your community plays in whether or not someone grows older in a positive and healthy way?

12. How does getting older affect you as a person? Give example(s)

Probing questions:

a. How does ageing impact your body? Bodily impact

b. How does ageing impact your spiritual wellbeing? Spiritual impact

c. How does ageing impact your emotions? Emotional impact

d. How does ageing impact your thoughts? Cognitive impact

13. Do you think elders in your community are ageing successfully?

14. How does someone in your community learn about ageing successfully? Are there ways that people share this knowledge?

15. Is there anything about ageing or being elder that you want to tell me, that I haven’t asked about yet?

Appendix B

Final Explanatory Model Successful Ageing Questionnaire:

Red Font Indicates Edits Adopted From the Elder Advisory Council

Participant ID #: _________________

Date: ___________________________

1. Would you mind telling me a little about yourself?

Prompt: How did you get to where you are now, an Elder?

2. How does it feel to be viewed as ageing successfully?

Prompt: What does it mean to you?

3. What do you think successful ageing means? What does it mean to you?

4. How did you learn about ageing well? From whom? Example?

5. How does ageing affect your day-to-day life? Examples

6. How has ageing affected your relationships? With Family? With Friends? With community? Examples.

7. How have your relationships affected your understanding of ageing?

8. What supports you in ageing well? How are you able to age successfully?

9. Why do you think some Elders age well and some do not?

10. How can you tell that an Elder is ageing well? Example?

11. How can you tell that an Elder is ageing poorly?

12. What does a person need to do to age well? To prevent poor ageing?

13. What does it mean to be an Elder? What is an Elders role?

14. How do you know if someone is regarded as an Elder or not?

Prompt: Is there anything that happens to mark this transition? A certain age?

15. Do you think elders in your community are ageing successfully? How has this changed, compared to 20 years ago?

16. Why do you think some Elders move away?

17. How do you think ageing is different in rural and urban settings?

18. Do you have any advice for people in your community who want to age successfully?

19. How do you feel about sharing your knowledge with the next generation?

What are the benefits? Challenges?

20. Why do you share your experiences with youth? What motivates you?

21. What is the most important thing you want to share with the youth?

22. Is there anything about ageing or being an Elder that you want to tell me that I haven’t asked about yet?