ABSTRACT

This scoping review examined research publications related to health and/or wellness along with gender among Canadian Indigenous populations. The intent was to explore the range of articles on this topic and to identify methods for improving gender-related health and wellness research among Indigenous peoples. Six research databases were searched up to 1 February 2021. The final selection of 155 publications represented empirical research conducted in Canada, included Indigenous populations, investigated health and/or wellness topics and focused on gender. Among the diverse range of health and wellness topics, most publications focused on physical health issues, primarily regarding perinatal care and HIV- and HPV-related issues. Gender diverse people were seldom included in the reviewed publications. Sex and gender were typically used interchangeably. Most authors recommended that Indigenous knowledge and culture be integrated into health programmes and further research. More health research with Indigenous peoples must be conducted in ways that discern sex from gender, uplift the strengths of Indigenous peoples and communities, privilege community perspectives, and attend to gender diversity; using methods that avoid replicating colonialism, promote action, change stories of deficit, and build on what we already know about gender as a critical social determinant of health.

Introduction

Health disparities between Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples in Canada are well-documented [Citation1–3]. There is growing awareness that the causes of such disparities have deep roots in complex historical, political, geographic, and social factors linked to the ongoing impacts of colonialism [Citation4]. Correspondingly, social determinants of health frameworks are increasingly being applied to emerging understandings of Indigenous health inequities, in recognition that such factors as income level, education, and gender have profound impacts on health status [Citation5]. Recognised as distinct from sex, which can be defined as a person’s biological and physiological features typically characterised as male/female, gender includes socially and culturally attributed roles, behaviours, and expectations that can be characterised on a complex continuum of changing expressions and identities [Citation6,Citation7]. Gender diversity references the degree to which a person’s gender identity, role, or expression is different from the cultural norms stipulated for people of a certain sex [Citation8]. As a social determinant, gender impacts health through the differential power that men, women, and gender diverse people hold in the various spaces they occupy; differential access to resources such as health care; different prevalence of risk-taking behaviour between and among genders; as well as different occupational and behavioural roles, constrained by social norms, that can impact exposures to various health risks and illness [Citation9,Citation10].

The impacts of gender on health and wellness are particularly relevant for Indigenous peoples, although there is limited understanding about the ways that gender impacts the health of Indigenous peoples. Research can be used as a tool for elucidating more robust understandings of Indigenous gender and health/wellness, and represents a promising means for resolving the persistent health disparities between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Canadians [Citation11]. Importantly, research must be carried out with Indigenous peoples using community-grounded methods to improve Indigenous health status. The landscape of research addressing the impacts of gender on Indigenous peoples’ health and wellness is largely uncharted. Although studies have been conducted and research is ongoing, there are no published reviews of the literature on Indigenous gender and health/wellness. This is important given the multiple intersecting ways that gender influences the health of Indigenous peoples, as well as the ways that gender diverse Indigenous peoples have largely been ignored by researchers [Citation12].

Thus, the goal of the current scoping review was to identify research that investigated the topic of gender in combination with the topic of health/wellness among Indigenous populations in Canada. Our intent was to identify understudied topics, define areas requiring additional scrutiny, and illuminate paths forward for further improving gender-related health and wellness research among Indigenous peoples. For the purpose of the current paper, we conceptualise health and wellness broadly, as a state that, from many Indigenous perspectives, includes an explicit focus on strengths, as well as connections to culture, community, family, and balance in spiritual, emotional, mental, and physical arenas [Citation13].

Background

By way of background, two of the authors (SR, LL), who were already working together, met author MT in the summer of 2019 when they travelled to Montreal, Quebec, to attend an Idea Fair and Learning Circle hosted by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR). The gathering was part of CIHR’s Indigenous Gender and Wellness Initiative, and provided opportunities for Indigenous researchers, community members, and allies to meet and exchange ideas around gender and wellness. As a follow-up to the event, SR, LL, and MT decided to apply for funding from CIHR to investigate, in partnership with the Cree communities of Maskwacîs in Alberta, research topics related to gender and health that were important to community members. We invited other researchers and community members doing research with Maskwacîs to be co-applicants on our grant application (BS, RTO, RL, CR). With the exception of one author who is being newly mentored in this work (ZK), as well as a librarian who we engaged for her systematic searching expertise (JK), each of the authors on this paper are either Maskwacîs community members (LL, CR, RL), Indigenous researchers (LL, MT), and/or have been co-designing and conducting research in partnership with the Maskwacîs community for several years (BS, RO, SR, MT), with a strong focus on relational and participatory methods. Our work has involved such topics as family and perinatal health [e.g. Citation14], menopause and mature women’s health [e.g. Citation15], as well as prevention-focused work with children and youth [e.g. Citation16], all of which cut across gender-related health and laid a foundation for the current work.

With restrictions on in-person work due to the COVID-19 pandemic, it was not possible for us to mobilise our original plans for conducting community workshops to identify research priorities related to gender and wellness. Therefore, we decided to carry out a literature review to expand our understanding of topics that other researchers have investigated, with the intention of using topics and ideas identified through our review as a springboard for conversations around community research priorities once health restrictions were relaxed and we could conduct our in-person work. Although the impetus for this review was based on a local need, this review has relevance for researchers, community members, and practitioners more broadly.

Methods

The scoping review method allows for examining the range and extent of literature with respect to a broad topic [Citation17,Citation18]. Thus, we chose to conduct a scoping review to draw together literature that examined Indigenous health and/or wellness along with gender.

Literature search

A medical librarian (JK) developed keyword terms in collaboration with the research team and executed comprehensive searches in Ovid MEDLINE, Ovid Embase, Ovid PsycINFO, CINAHL, Scopus, and Bibliography of Native North Americans. The latter database was added given its specific focus on research covering Indigenous culture, history, and life in North America. Literature from database inception up to and including 1 February 2021 was searched. Relevant keywords were carefully selected, including a search filter for Indigenous populations [Citation19], refer to Appendix 1 for full-text search terms]. A total of 1256 results were retrieved. After duplicates were removed, 945 unique results remained; these articles were screened by title and abstract in a web-based tool called Covidence (Covidence, n. d.). Bibliographies from included studies were also reviewed.

Inclusion/exclusion criteria

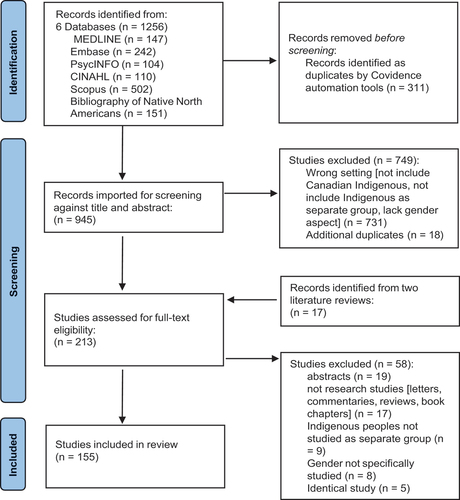

Publications were deemed eligible for inclusion if they (1) included Indigenous populations in their sample; (2) represented empirical research; (3) were conducted in Canada; (4) investigated topics relevant to health and/or wellness (broadly conceptualised as a state of wellbeing, and not simply the absence of disease); and (5) included an explicit focus on gender as the object of inquiry or included gender more peripherally (as a variable in the study’s analyses, for example). Articles that did not meet any one of these criteria were excluded. In addition, non-empirical grey literature such as conference proceedings and commentaries were excluded. Abstracts were also excluded because they provided limited information relevant to our selection criteria. Systematic reviews were excluded but were examined for relevant citations. Articles screened by title and abstract as well as article added from systematic reviews were read in full by four investigators (SR, MT, LL, BS), with two investigators reading each article; a third investigator was consulted to resolve disagreements that arose. The final selection consisted of 155 articles, including nine theses (refer to Appendix 2 for the full list of 155 references). Our search strategy is outlined in a PRISMA diagram ().

Data extraction and analysis

Data were extracted into an Excel spreadsheet and organised according to author and publication year. We extracted data from each study relevant to participant characteristics and study characteristics.

Participant characteristics

We extracted data regarding participants’ Indigenous group, sex and gender, and age. We extracted data by classifying information from each study according to predetermined categories (e.g. for participant gender, categories consisted of women, men, gender diverse participants, and unspecified). Data analysis consisted of calculating the number and relative percentage of studies that fell into the predetermined categories.

Study characteristics

We extracted data regarding each study’s description of the methodological design, data collection method, community involvement, setting, health/wellness topics, objectives, recommendations, and knowledge mobilisation strategies. With respect to methodological design, data collection method, community involvement, and setting, and health/wellness topics, data were extracted according to the ways that authors specified this information in each article. In other words, we did not determine these study characteristics ourselves, but rather relied on authors’ descriptions. We then classified information from each study according to predetermined categories. Our categories were adjusted throughout the data extraction process as we became increasingly familiar with the data.

As for the study objectives, implications, and knowledge mobilisation strategies, we extracted data by copying text directly from each article and pasting into a spreadsheet. Data were then imported into NVIVO data analysis software and each of these three areas (objectives, knowledge mobilisation, recommendations) were analysed separately using content analysis [Citation20]. More specifically, information from each of the three areas was first read through thoroughly to establish familiarity. Next, data were assigned descriptive labels (termed “nodes” in NVIVO), and subsequently sorted into categories to reflect the breadth of the data. Categories were discussed and agreed on before being finalised.

Findings

Participant characteristics

In the subsections that follow, we summarise the data extracted from each article relevant to participants’ Indigenous group, sex, gender, and age. We summarise these data by reporting the percentage of studies that fell into various categories within each participant characteristic.

Indigenous group

The majority of studies described the inclusion of First Nations peoples as research participants (n = 61; 39%). The inclusion of Inuit peoples was described in 8% of studies (n = 13), whereas Métis peoples made up the study sample in 2% of studies (n = 3). Study samples consisting of a combination of these three Indigenous groups were specified in 19% of studies (n = 30). Thirty-one percent of studies (n = 48) used the more general terms “Indigenous” or “Aboriginal” to describe study participants.

Sex and gender

In , we summarise the number of articles that used various descriptions of participant sex and gender categories in the methods sections of the 155 articles included in our review. The majority of articles used gender language in describing participants (i.e. women, men), with women alone being the most common participants (n = 60; 39%). Only seven articles included gender diverse participants alone, and an additional 11 articles included gender diverse participants along with other genders. Moreover, 19 articles used sex and gender language interchangeably in their methods sections. Although the table only reports on descriptions as provided in the methods sections of articles included in our review, we also note that, when examining articles in their entirety (i.e. beyond methods sections), 118 articles (76%) used sex and gender language interchangeably.

Table 1. Participant sex and gender as described in included articles.

Age

With respect to participant age, we extracted data as to whether articles included participants who were adults, adolescents/youth, or children. Where articles did not explicitly use this language, we counted adults as being age 18+, adolescents/youth as being age 13–17, and children as being ages 0–12. The majority of articles included adult participants, either alone (n = 108; 69.7%) or in combination with children (n = 1; 0.6%), adolescents (n = 19; 12.2%), or both (n = 1; 0.6%). A smaller proportion of article included child participants alone (n = 4; 2.6%), adolescents alone (n = 17; 11.0%), or both children and adolescents (n = 2; 1.3%). Participant age was not specified in three (1.9%) articles.

Study characteristics

In the subsections below, we summarise the design characteristics of the studies included. For example, the five health/wellness categories emerged directly from the data we collected from the published papers, and the methdological design and data collection methods of each study were identified directly from each paper’s text.

Health/wellness topic

Research topics were characterised according to five categories of health/wellness which emerged from the data: mental, social, global, physical, and health policies and perceptions (). Some studies focused on more than one topic. The majority (n = 69; 44.5%) focused on physical health issues, primarily with regard to perinatal care and HIV- and HPV-related issues. Social issues were discussed in 48 articles (31.0%) including intergenerational and historic trauma and loss of traditional way of life due to colonialism. Of particular interest to the focus of our review, four articles focused on gender identity; three of these specifically researched health/wellness issues among sexual minority and gender diverse people. Forty-one (26.5%) articles investigated mental health issues, with approximately half of these focusing on gender-related substance abuse, gambling, and addiction, and the other half examining mental disorders and suicide. Health promotion, policies, and perceptions were the focus of 26 articles (16.8%). These dealt with such topics as health literacy, health promotion programmes, and perceptions of health and wellness in gender diverse people. Global health/wellness issues were explored in 10 articles (6.5%) and included such topics as the impact of climate, food resources, water and land use on Indigenous health and wellness.

Table 2. Topics of included articles.

Methodological design and data collection methods

The majority of studies included in our review used a qualitative methodological approach (n = 82; 53%). Fifty-seven studies (37%) used a quantitative approach, and 16 studies (10%) used a mixed or multiple method approach. Of the articles that utilised a qualitative approach, the majority (n = 43; 52%) did not further specify a particular qualitative design; the remainder of articles were roughly split between case study (n = 8), phenomenology (n = 7), qualitative or interpretive description (n = 7), grounded theory (n = 6), and ethnography (n = 6), followed by narrative design (n = 4). Of the articles that utilised a quantitative approach, the majority (n = 39; 68%) used a cross-sectional design followed by longitudinal (n = 11), quasi-experimental (n = 5), case study (n = 1), and randomised controlled trial (n = 1).

Articles described a variety of data collection methods. Those methods described by authors as aligning with Indigenous research approaches included sharing or talking circles (n = 11), storytelling (n = 5), and symbol-based reflection (n = 1). Interviews (n = 89) and surveys (n = 53) were used most often, followed by focus groups (n = 23), health record reviews (n = 18), participant observations (n = 11), visual methods (n = 11), and document reviews (n = 9).

Community involvement

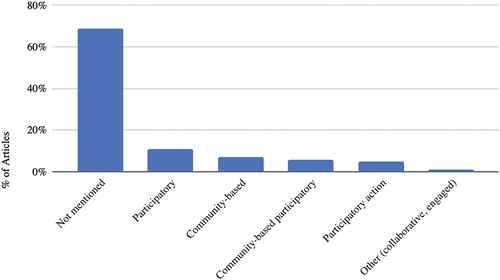

We also collected data regarding the extent of reported community involvement. First, we examined each article to determine whether authors labelled their approach in line with approaches denoting community involvement (i.e. community-based or participatory methods). Seventy percent of studies (n = 108) did not label their approach in line with community-based or participatory methods; the remainder indicated using either participatory, community-based, community-based participatory, participatory action, or other research approaches (see below).

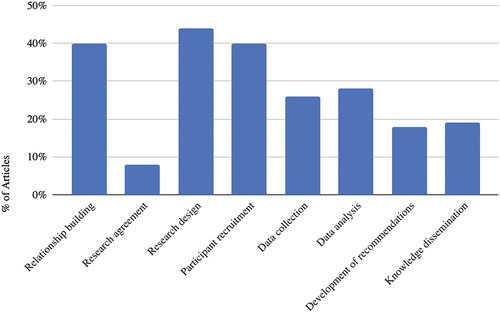

In addition, we drew from methods used by [Citation21], to examine whether studies reported the involvement of communities in key stages of the research process. These included developing a research agreement, research design, participant recruitment, data collection, data analysis, developing recommendations, and knowledge dissemination; we also extracted information as to whether authors reported relationship building with communities. As depicted in , involvement of communities in any given research stage was reported in less than half of the articles included in our review. The lowest proportion of articles (8%, n = 12) reported developing a research agreement with communities. The highest proportion of articles (44%, n = 68) reported involving communities in designing their research study.

Study setting

The majority of participants in the studies selected for our review were from rural settings (n = 54; 34.8%), followed by urban (n = 41; 26.5%), or both (n = 24; 15.5%). For the purpose of this review, we included Indigenous communities, villages, and reserves in the “rural setting” category. Thirty-six articles (23.2%) did not report their research setting.

Objectives

With respect to study objectives, data were organised into seven categories. depicts these categories along with selected representative examples of objectives that fell under each category.

Table 3. Objectives described in included articles.

Recommendations

Primary recommendations suggested by study authors are summarised in . The largest proportion of articles (n = 32; 20%) recommended that Indigenous knowledge and culture should be integrated into health programmes as well as further research to solidify findings.

Table 4. Recommendations described in included articles.

Knowledge mobilisation strategies

We defined “knowledge mobilization strategies” as any activities, other than academic publications, aimed at disseminating the findings beyond the research team, such as to communities or policymakers. Of the 155 articles reviewed, only 23 (15%) described knowledge mobilisation activities. depicts the knowledge mobilisation activities described, the number of articles that mentioned these activities, and examples of knowledge mobilisation activities. Of the articles that did not describe knowledge mobilisation activities, many recommended that knowledge mobilisation take place without describing how the knowledge from their own study had been shared; for example, “increasing awareness amongst the healthcare profession needs to be supported by the appropriate changes in the relevant system … to ensure that knowledge is translated to practice” [Citation29]. Others stressed that practitioners should be aware of their study’s findings without indicating that they were taking steps to generate this awareness; for example, “Health care providers should be aware that Aboriginal women are at greater risk for not initiating breastfeeding” [Citation30].

Table 5. Knowledge mobilisation activities described in included articles.

Discussion

Through the current literature review, we sought to identify the scope of existing literature on the topic of Indigenous gender and health/wellness in Canada. Using 155 studies selected for inclusion in our scoping review, we framed our findings in terms of participant characteristics and study characteristics. We found that the literature incorporated a wide range of methods, covered diverse health and wellness topics, and involved Indigenous communities across Canada. Throughout the following discussion, we expand and reflect on our findings in the three areas relevant to our scoping review objectives; namely, research focusing on (1) Indigenous populations, (2) gender and sex and (3) health/wellness.

Research focusing on indigenous populations

Our review identified a wide range of health and wellness research among Indigenous peoples in Canada. The studies we reviewed tended to describe research among a single Indigenous Nation or community. While this might be considered a limitation with respect to generalisability, we take the position that the community-specific nature of this work is a strength given that it may reflect the grounding of these studies in community, with the potential to produce research of local relevance. Some of the research we reviewed was less grounded in community or simply did not involve communities as contributors to the project; for example, database studies that generally reported no or limited community involvement. It is now widely recognised that it is ethically imperative to involve Indigenous peoples in research that impacts them [Citation31,Citation32]. Many studies made this point, given that study recommendations were made to increase the impact of research with Indigenous peoples by involving Indigenous peoples in research planning and conduct, addressing questions important to communities, and taking a strengths-based approach [Citation33]. However, a notable limitation is the apparent lack of knowledge mobilisation taking place by researchers studying Indigenous gender and health/wellness. We found that very few studies reported on knowledge mobilisation activities. To be fair, authors may have engaged in knowledge mobilisation activities without reporting them in their articles; however, we take the position that knowledge mobilisation should be a key aspect of Indigenous health research and we call upon researchers in this area to routinely include knowledge mobilisation aimed at audiences outside of academia.

Gender

As mentioned above in our methods section, this review included articles that focused explicitly on gender as the object of inquiry [Citation34], articles that examined a health issue in relation to one specific gender [Citation35], and articles that looked at gender more peripherally, as one of several variables being analysed [Citation36]. One of the most striking limitations of the articles we reviewed was that gender and sex were infrequently differentiated. Sex was frequently reported; however, gender, the social construct, was seldom discussed specifically, and it was common for authors to conflate sex and gender altogether. Although this finding in part may reflect the age of some of the studies we reviewed, we found a continued lack of differentiation of sex and gender even in more recent articles. Importantly, however, some of the articles we reviewed did account for differences between sex and gender [Citation37]. Typically, these were more restricted studies concentrating on gender issues specifically and highlighted strengths in Indigenous communities. In addition, those authors who differentiated between sex and gender also tended to use participatory methods (e.g. community-led and community-driven research questions).

Another important finding was that gender diverse people were seldom included in the articles we reviewed. Several causes may be responsible for this lack of attention: while research on the development and implementation of interventions for gender diverse people is slowly increasing [Citation38], it is often difficult for researchers to access individuals who do not self-report as men or women, making research on the less prevalent genders difficult to conduct. This difficulty may stem from the systemic and individual stigma that sexual minority and gender diverse people continue to be subjected to in Canada and elsewhere based on their identities [Citation39], as well as a lack of understanding on the part of researchers as to how to structure sex and gender questions in a way that effectively engages sexual minority and gender diverse people [Citation40]. In addition, the definitions and terminology around gender diversity vary widely and continue to evolve. Regardless of the reasons for the lack of attention to gender diverse people in the field of research on Indigenous gender and health/wellness, there is a clear need to better understand the health needs of this diverse population. It is also imperative that research addresses the intersecting, structural barriers that Indigenous gender diverse people face, resulting in unacceptable, compounding health disparities. This critical gap regarding researchers’ lack of attention to intersectionality has been identified by several other authors exploring questions relevant to sexual minority and gender diverse people [e.g. Citation38–40]. Relatedly, researchers must fundamentally recognise the complexity of gender identity and expression; for example, respecting that terms such as “two-spirit” are contested and variably adopted by Indigenous gender diverse peoples, and working from an understanding that different Indigenous Nations and communities approach and understand gender in unique ways. Ultimately, there must be an acknowledgement that the social construct of gender is heavily influenced by colonialism, and that fluid, multi-dimensional, and affirmative conceptualisations of gender have long been part of the history of Indigenous cultures in Canada and elsewhere [Citation41–43]. In short, gender is far more complex than much of the academic literature currently reflects, although Indigenous cultures reflect a long-standing historical awareness of gender as a complex construct.

Health and wellness

The published research included in our review related to a wide variety of health concerns and solutions. We were intentional in focusing on the concepts of health and wellness, recognising that, while health is an important part of wellness, these terms are not synonymous. Wellness, a more wholistic term, is important from many Indigenous perspectives; as Elder Jim [Citation44], has stated, “Wellness from an Indigenous perspective is a whole and healthy person expressed through a sense of balance of spirit, emotion, mind and body. Central to wellness is belief in one’s connection to language, land, beings of creation, and ancestry, supported by a caring family and environment” (p. 2). Thus, we worked from the awareness that health and wellness involve more than the absence of illness, and this awareness was variably reflected in the articles we reviewed. Many articles read as expressly deficit-oriented, focusing on health and wellness challenges rather than the promotion of health. Accordingly, our review highlights the need for health researchers to centre Indigenous strengths and assets. Although challenges and deficits undoubtedly exist, there is a need to present a balanced picture of both limitations and strengths in order to avoid contributing to the deficit-based narrative that has typically characterised Indigenous health research [Citation45].

Many of the articles we reviewed addressed important health issues that researchers and society more generally often associate with Indigenous people such as addiction, abuse, and trauma. Importantly, any discussion of Indigenous health challenges must be framed appropriately within the context of social determinants of health, including colonialism. To neglect a contextualisation of Indigenous health issues is to risk contributing to ongoing stereotypes and misunderstandings about the root causes of health disparities. In this vein, a promising finding from our review was that many articles focused on understanding the perspectives of Indigenous peoples with respect to health and wellness issues. This created the opportunity for a focus on achieving wellness through cultural and traditional ways [e.g. Citation46]. Researchers need to be reminded that cultural and traditional beliefs and practices are important in promoting health and wellness, and privileging the perspectives of Indigenous peoples in health research represents a way forward in this respect [Citation47].

Limitations of our review

We restricted our search to Canadian research so that our findings would be applicable to the specific goal of understanding the scope of Indigenous gender and wellness research in the Canadian context. This could be seen as a limitation of our study given that our findings may have varied if we had opened our search to other countries; however, it should be noted that generalisability was not a goal of our review. In addition, we specifically looked at published peer-reviewed articles, and we acknowledge that this restricts the forms of knowledge being examined in this paper. We chose to leave out grey literature from our review in order to provide parameters on our search and to align with our purpose. However, this may have resulted in the exclusion of work being conducted outside of a research context, and we acknowledge that this is a limitation of our scoping review. Similarly, we recognise that scoping reviews represent only one form of knowledge. Therefore, we also acknowledge the community accountability that we have, as Indigenous and non-Indigenous researchers, to gather community-grounded perspectives on the field of Indigenous gender and health/wellness research. Although authors of this paper represent a complement of Indigenous and non-Indigenous researchers, as well as Indigenous community members, the COVID-19 pandemic limited the participation of Indigenous community members in the current scoping review. As a result, we plan to next move forward with our original plan of conducting community workshops in order to more fully centre community perspectives in our work related to Indigenous gender and wellness.

Intersectionality

During our group’s detailed discussions about gender, health and wellness among Indigenous people, we found that the concept of intersectionality helped to shed light on the complex interactions between these factors and why it is important to consider them concurrently. Kimberle [Citation48], coined the term intersectionality to describe how markers of identity could be understood as mutually constituted to produce structural inequity over time and in different contexts. Working from an intersectional lens, understandings of health disparities can be grounded in consideration of the ways that age, sex, gender, race, ethnicity, poverty, class, and sexuality collide to influence the experiences of Indigenous peoples in complex ways. Moreover, the concept of intersectionality brings to light how identity, social position, oppression, and privilege, as well as policies and institutional practices, interrelate to critically influence the health and wellness of Indigenous peoples [Citation49,Citation50]. For example, a First Nations woman living on reserve will experience multiple forms of oppression differently than a two-spirit Métis person living in an urban setting. However, both will experience unique oppressive systems in simultaneous ways that can make these forms of oppression indistinguishable from one another. In our group’s future research with Indigenous people, the intersection of gender, health and wellness will be an important feature when attempting to interpret any research findings. We encourage other researchers working with Indigenous people to consider the concept of intersectionality as an integral feature of their research.

Conclusions

Through the current review, we set out to examine the scope of literature in the field of Indigenous gender and health/wellness research. We found that the literature in this area focuses on diverse health and wellness topics, involves Indigenous peoples and communities to varying degrees, inconsistently differentiates between sex and gender, and generally lacks a focus on gender diverse people. Importantly, we found several articles that were exemplary in terms of discerning sex from gender, uplifting the strengths of Indigenous peoples and communities, privileging community perspectives, and attending to gender diversity. Based on the findings of our review, we advocate that more research must be conducted in this way; using methods that avoid replicating colonialism, promote action, change stories of deficit, and build on what we already know about gender, including identification as gender diverse, as a critical social determinant of health.

Supplemental Material

Download Zip (60.3 KB)Acknowledgments

We are grateful for the support of the Canadian Institutes of Health Research for their generous support of this work. We also extend our deepest gratitude to the Maskwacîs community for several years of partnership and for co-generating knowledge that continues to guide and inspire our work together. Finally, we acknowledge the support of Claudine Louis, Bonita Graham, and Lola Baydala in this work.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Supplementary data

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/22423982.2023.2177240.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Adelson N. The embodiment of inequity: health disparities in Aboriginal Canada. Can J Public Health. 2005;96:5.

- Gracey M, King M. Indigenous health part 1: determinants and disease patterns. Lancet. 2009;374:65–13.

- Smylie J, Firestone M. Back to the basics: identifying and addressing under- lying challenges in achieving high quality and relevant health statistics for Indigenous populations in Canada. Stat J IAOS. 2015;31(1):67–87.

- Mitchell T, Arseneau C, Thomas D. Colonial trauma: complex, continuous, collective, cumulative and compounding effects on the health of Indigenous peoples in Canada and beyond. Int J Indigenous Health. 2019;14:74–94.

- Nesdole R, Voigts D, Lepnurm R, et al. Reconceptualizing determinants of health: barriers to improving the health status of First Nations peoples. Can J Public Health. 2014;105(3):255.

- Canadian Institutes of Health Research. (2020). What is gender? What is sex?. [cited 2022 Jun 1]. Retrieved from https://cihr-irsc.gc.ca/e/48642.html

- Covidence systematic review software, Veritas Health Innovation, Melbourne Australia. [cited 2022 Jun 1]. Available at www.covidence.org

- American Psychological Association. (2015). Key terms and concepts in understanding gender diversity and sexual orientation among students. [cited 2022 Jun 1]. Retrieved from www.apa.org

- Heise L, Greene ME, Opper N, et al. Gender inequality and restrictive gender norms: framing the challenges to health. Lancet. 2019;393(10189):2440–2454.

- Phillips SP. Defining and measuring gender: a social determinant of health whose time has come. Int J Equity Health. 2005;4(11):15.

- Lafontaine A. Indigenous health disparities: a challenge and an opportunity. Canadian Journal of Surgery. 2018;61(5):300–301.

- Soldatic K, Briskman L, Trewlynn W, et al., Social and emotional wellbeing of Indigenous gender and sexuality diverse youth: mapping the evidence. Culture Health Sex. 2021;2021:5

- Thiessen K, Haworth-Brockman MR, Stout R, et al. Indigenous perspectives on wellness and health in Canada: study protocol for a scoping review. Syst Rev. 2020;9:177.

- Oster R, Bruno G, Mayan M, et al. Peyakohewamak—needs of involved Nehiyaw (Cree) fathers supporting their partners during pregnancy: findings from the ENRICH study. Qual Health Res. 2018;28(14):2208–2219.

- Sydora B, Graham B, Oster R, et al. Menopause experience in First Nations women and initiatives for menopause symptom awareness: a community-based participatory research approach. BMC Women’s Health. 2021;21(1). DOI:10.1186/s12905-021-01303-7

- Tremblay M, Baydala L, Rabbit N, et al., Cultural adaptation of a substance abuse prevention program as a catalyst for community change. J Commun Engage Scholr. 2016;9(1):10.

- Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Method. 2005;8:19–32.

- Levac D, Colquhoun H, O’Brien KK. Scoping studies: advancing the methodology. Implement Sci. 2010;5(1):1.

- Campbell S, Dorgan M, Tjosvold L. Filter to Retrieve Studies Related to Indigenous People of Canada the OVID Medline Database. John W. Scott Health Sciences Library, University of Alberta; 2016. https://guides.library.ualberta.ca/health-sciences-search-filters/indigenous-peoples

- Krippendorff K. Content analysis: an introduction to its methodology. 2nd ed. ed. Thousand Oaks CA: Sage; 2004.

- Murphy K, Branje K, White T, et al. Are we walking the talk of participatory Indigenous health research? A scoping review of the literature in Atlantic Canada. PLoS One. 2021. Jul 27;16(7):e0255265. PMID: 34314455; PMCID: PMC8315539.

- Cidro J, Zahayko L, Lawrence HP, et al. Breast feeding practices as cultural interventions for early childhood caries in Cree communities. BMC Oral Health. 2015;15(49):

- Bennett R, Cerigo H, Francois C, et al. Incidence, persistence, and determinants of human papillomavirus infection in a population of Inuit women in northern Quebec. Sex Transm Dis. 2015;42(5):272–278.

- Moffitt P and Dickinson R. (2016). Creating exclusive breastfeeding knowledge translation tools with First Nations mothers in Northwest Territories, Canada. Int J Circumpolar Health, 75(1), 32989 10.3402/ijch.v75.32989

- Sheppard AJ, Chiarelli AM, Hanley AJG, et al. Influence of preexisting diabetes on survival after a breast cancer diagnosis in first nations women in Ontario, Canada. JCO Glob Oncol. 2020;6:99–107.

- Ziabakhsh S, Pederson A, Prodan-Bhalla N et al, Women-centered and culturally responsive heart health promotion among Indigenous women in Canada. Health Promotion Practice. 2016;17(6):814–826.

- Wright AL, Jack SM and Ballantyne M, et al. (2019). How Indigenous mothers experience selecting and using early childhood development services to care for their infants. Int J Qual Stud Health Well-Being, 14(1), 1601486 10.1080/17482631.2019.1601486

- Kenny C. (2006). When the Women Heal. Am Behav Sci, 50(4), 550–561. 10.1177/0002764206294054

- Cleary E, Ludwig S and Riese N, et al. (2006). Educational Strategies to Improve Screening for Gestational Diabetes Mellitus in Aboriginal Women in a Remote Northern Community. Can J Diabetes, 30(3), 264–268. 10.1016/S1499-2671(06)03001-2

- McQueen K, Sieswerda LE and Montelpare W, et al. (2015). Prevalence and Factors Affecting Breastfeeding Among Aboriginal Women in Northwestern Ontario. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic & Neonatal Nursing, 44(1), 51–68. 10.1111/1552-6909.12526

- Fitzpatrick EFM, Martiniuk AL, Antoine H, et al. Seeking consent for research with Indigenous communities: a systematic review. BMC Med Ethics. 2016;17(65):75.

- Willows ND. Ethics and research with Indigenous peoples. In: Liamputtong P, editor Handbook of research methods in health social sciences. Springer; 2019, 1847-1870. doi:10.1007/978-981-10-5251-4_49

- Rand JR. (2016). Inuit women's stories of strength: informing Inuit community-based HIV and STI prevention and sexual health promotion programming. Int J Circumpolar Health, 75(1), 32135 10.3402/ijch.v75.32135

- Prussing E and Gone JP. (2011). Alcohol Treatment in Native North America: Gender in Cultural Context. Alcoholism Treatment Quarterly, 29(4), 379–402. 10.1080/07347324.2011.608593

- Emanuelsen K, Pearce T and Oakes J, et al. (2020). Sewing and Inuit women's health in the Canadian Arctic. Social Science & Medicine, 265 113523 10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.113523

- Filbert KM and Flynn RJ. (2010). Developmental and cultural assets and resilient outcomes in First Nations young people in care: An initial test of an explanatory model. Child Youth Services Rev, 32(4), 560–564. 10.1016/j.childyouth.2009.12.002

- Chazan M. (2019). Unsettling aging futures: Challenging colonial-normativity in social gerontology. Int J Ageing Later Life, 1–29. 10.3384/ijal.1652-8670.19454

- Layland EK, Carter JA, Perry NS, et al. A systematic review of stigma in sexual and gender minority health interventions. Transl Behav Med. 2020;10(5):1200–1210.

- Logie CH, Lys CL, Schott N, et al. ‘In the North you can’t be openly gay’: contextualising sexual practices among sexually and gender diverse persons in Northern Canada. Glob Public Health. 2018;13(12):1865–1877.

- Suen LW, Lunn MR, Katuzny K, et al. What sexual and gender minority people want researchers to know about sexual orientation and gender identity questions: a qualitative study. Arch Sex Behav. 2020;49:2301–2318.

- Lang S. Transformations of gender in Native American cultures. Litteraria Pragensia. 2011;21(42):70–81.

- Picq ML, Tikuna J. Indigenous sexualities: resisting conquest and translation. In: Cottet C, Picq ML, editors. Sexuality and translation in world politics. London, UK: E-International Relations Publishing; 2019. p. 57–71.

- Wilson A. How we find ourselves: identity development and two-spirit people. Harvard Edu Rev. 1996;66(2):303–317.

- Dumont J. Connecting with culture: growing our wellness activity guide. Ottawa, ON, Canada: Canadian Institutes of Health Research; 2014.

- Kennedy A, Senghal A, Szabo J, et al. Indigenous strengths-based approaches to healthcare and health professions education – recognising the value of Elders’ teachings. Health Educ J. 2022;81(4):423–438.

- Waddell CM, de Jager MD, Gobeil J, et al. Healing journeys: indigenous men’s reflections on resources and barriers to mental wellness. Soc sci med. 2021;270:113696.

- Anderson K, Clow B, Haworth-Brockman M. Carriers of water: aboriginal women’s experiences, relationships, and reflections. J Clean Prod. 2013;60:11–17.

- Crenshaw K (1989). Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex: a Black feminist critique of antidiscrimination doctrine, feminist theory and anti- racist politics. University of Chicago Legal Forum, 139–167.

- Bauer G. Incorporating intersectionality into population health research methodology: challenges and the potential to advance health equity. Soc sci med. 2014;110:10–14.

- Kaushik V, Walsh CA. A critical analysis of the use of intersectionality theory to understand the settlement and integration needs of skilled immigrants to Canada. Canadian Ethnic Stud. 2018;50(3):27–47.