ABSTRACT

Background: To improve the quality of care for Indigenous patients, local Indigenous leaders in the Northwest Territories, Canada have called for more culturally responsive models for Indigenous and biomedical healthcare collaboration at Stanton Territorial Hospital.

Objective: This study examined how Indigenous patients and biomedical healthcare providers envision Indigenous healing practices working successfully with biomedical hospital care at Stanton Territorial Hospital.

Methods: We carried out a qualitative study from May 2018 – June 2022. The study was overseen by an Indigenous Community Advisory Committee and was made up of two methods: (1) interviews (n = 41) with Indigenous Elders, patient advocates, and healthcare providers, and (2) sharing circles with four Indigenous Elders.

Results: Participants’ responses revealed three conceptual models for Indigenous and biomedical healthcare collaboration: the (1) integration; (2) independence; and (2) revisioning relationship models. In this article, we describe participants’ proposed models and examine the extent to which each model is likely to improve care for Indigenous patients at Stanton Territorial Hospital. By surfacing new models for Indigenous and biomedical healthcare collaboration, the study findings deepen and extend understandings of hospital-based Indigenous wellness services and illuminate directions for future research.

Introduction

Reports, studies, and new sources have documented the pervasive and devastating impacts of anti-Indigenous racism in Canada’s healthcare system [Citation1–7]. Out of Sight, the interim report from the Brian Sinclair Working Group in Winnipeg, Canada, describes how Brian Sinclair, a 45-year-old man from Sagkeeng First Nation died in September 2008 from complications of a treatable bladder infection after being ignored for 34 hours in the emergency department of a Winnipeg hospital. The few healthcare providers who noticed Mr. Sinclair in the waiting room assumed that he was homeless or drunk, and even when Mr. Sinclair vomited multiple times, no staff offered medical support [Citation6]. Likewise, the In Plain Sight report investigated anti-Indigenous racism in British Columbia’s healthcare system in response to allegations that hospital emergency staff were playing a “game” where they would guess Indigenous patients’ blood-alcohol levels [Citation8]. While the report was unable to substantiate allegations of the racist guessing “game”, it found widespread stereotyping, systemic racism, and discrimination against First Nations, Inuit, and Métis patients [Citation8]. The report also documented the impact of institutional and structural racism on Indigenous patient outcomes. It illustrated that Indigenous patients are less likely to have access to crucial medical services, such as cancer screening and prenatal care, and that Indigenous patients experience longer wait times, fewer referrals, and disrespectful treatment [Citation8].

Studies throughout Canada, including a study from the Northwest Territories (NWT), have found that Indigenous peoples’ experiences with mainstream healthcare are often characterised by stereotyping, indifference, and judgement from healthcare providers. Indigenous participants from various Indigenous Nations described situations where they were not listened to, not believed, or actively ignored by healthcare providers [Citation9–13]. Additionally, research demonstrates that Indigenous peoples are often negatively impacted when biomedical healing practices are prioritised over Indigenous healing practices [Citation1,Citation4,Citation6,Citation7]. Many Indigenous patients report feeling judged and alienated by healthcare providers, and they recount experiences of systemic racism when trying to access care [Citation1,Citation4,Citation6,Citation7]. Alternatively, when there is an option to access Indigenous healing in biomedical healthcare environments, Indigenous patients have described more positive healthcare experiences and increased ownership over their health and healthcare decisions [Citation14,Citation15].

National and international reports such as the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC), the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples (RCAP), and the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP) have called for Indigenous healing to be valued within the mainstream healthcare system and for greater collaboration between Indigenous and biomedical healing practices [Citation7,Citation16,Citation17]. The TRC’s Call to Action #22 states:

We call upon those who can affect change within the Canadian healthcare system to recognize the value of Aboriginal healing practices and use them in the treatment of Aboriginal patients in collaboration with Aboriginal healers and Elders where requested by Aboriginal patients.

To improve the quality of care for Indigenous peoples, hospitals in Canada have started to provide Indigenous wellness services, which include services such as patient navigation, medical translation and interpretation, and access to Indigenous healing practices and medicines [Citation18–22].

The few research studies that examine hospital-based Indigenous wellness services in Canada have identified two existing models: (1) Indigenous wellness services offered in Indigenous-governed and operated hospitals; and (2) Indigenous wellness services offered in mainstream hospitals [Citation18,Citation21]. There are no published research articles to date that provide an in-depth analysis of the few Indigenous-governed and operated hospitals in Canada. Nevertheless, there are some articles that compare health service models across Canada, and discuss Indigenous-governed and operated hospitals as part of their larger reviews [Citation4,Citation18,Citation21,Citation23]. The authors of these articles assert that when Indigenous peoples have greater control over health services (i.e. in Indigenous-governed and operated hospitals), this can result in better population health outcomes and improved access to Indigenous wellness services and healing practices for Indigenous peoples[Citation18,Citation21,Citation23].

Outside of Canada, the Alaska Native Medical Centre in Anchorage, Alaska, is often cited by Indigenous communities and health policy makers as an aspirational model for an Indigenous-governed and operated hospital [Citation24]. The Alaska Native Medical Centre is owned and operated by Alaska Natives and grounded in the “Nuka System of Care”, which “is a relationship-based, customer-owned approach to transforming healthcare, improving outcomes, and reducing costs” [Citation25]. In the Nuka model, healthcare is provided to clients (i.e. “customer-owners”) through small integrated teams that focus on each customer-owner’s unique stories and values. The Nuka System of Care incorporates Indigenous knowledges and cultural services into the delivery of healthcare. Tribal doctors hold the same status as medical doctors and primary care physicians provide referrals for Indigenous healing just as they would any other kind of specialised care [Citation26]. A 2013 review of the Nuka System of Care measured the successes of this model over a 10-year period. Among other indicators, emergency department use decreased by 42%, staff turnover decreased by 75%, and 94% of patients and clients reported that they felt their cultures were respected [Citation27].

In Canada, Indigenous wellness services in mainstream hospitals are more commonly described in the literature [Citation19,Citation22,Citation23,Citation27–32]. In this model, the wellness services often look similar to those in Indigenous-governed and operated hospitals (i.e. patient navigation, interpretation services, and access to Indigenous medicines); however, given that each hospital has a distinct geographical service area, political environment, governance and funding structure, and relationship with Indigenous Nations, the range of services and the ways they operate vary greatly [Citation19,Citation22,Citation23,Citation27–32]. Scholars have asserted that one of the key differences between Indigenous wellness services in mainstream hospitals and those in Indigenous-governed and operated hospitals is that in mainstream hospitals, biomedical medicines and knowledge systems “often remain the standard for comparison, for ethical guidelines, and for making claims of efficacy, and therefore retain power” [Citation18]. As a result, rather than starting with a foundation of Indigenous knowledges and integrating biomedical healthcare when appropriate (as is the case in Indigenous-governed and operated hospitals), in this model, biomedical knowledge systems often set the standard for care and Indigenous wellness services are expected to fit into or align themselves with the biomedical model [Citation18].

The limited research that examines Indigenous wellness services in mainstream Canadian hospitals highlights opportunities and challenges for integrative care. For example, researchers have shown that having Indigenous governance at the hospital and providing education for biomedical healthcare providers in Indigenous cultural safety and Indigenous healing and medicines can help to improve care for Indigenous patients and better support the integration of Indigenous healing through a mainstream hospital’s Indigenous wellness services [Citation19,Citation20,Citation22,Citation33]. Nevertheless, scholars also warn that when Indigenous healing practices are brought into pre-defined biomedical structures, there is a risk that Indigenous knowledges and practices may be appropriated, misused, or watered down [Citation18,Citation34]. Additionally, Indigenous Elders, community members, and researchers caution that when Indigenous healing is brought into mainstream hospitals, Indigenous healing is at greater risk of being regulated and controlled by non-Indigenous peoples and policies [Citation20,Citation33,Citation34]. To mitigate these concerns, Elders and researchers have suggested that Indigenous peoples and communities need to be the ones to determine whether and how integration takes place [Citation19,Citation22,Citation33,Citation34].

It is important to note that the studies in Canada that examine Indigenous wellness services in mainstream hospitals are largely based in Ontario [Citation15,Citation19,Citation20,Citation22,Citation31]. As a result, their findings do not necessarily translate to other regions. Instead of trying to copy and paste from one model to another, it is important for Indigenous leaders and Knowledge Holders in each community to determine how and to what extent Indigenous healing and models of care could or should be brought into their local healthcare settings.

Research questions and objectives

In the NWT, Canada, the need to bring Indigenous healing practices into hospital care is especially great. Stanton Territorial Hospital, the largest hospital in the NWT, provides care to both residents of the NWT, where 51% of the population identifies as First Nations, Métis, or Inuit, and residents of the Kitikmeot Region of Western Nunavut, where over 85% of the population identifies as Inuit [Citation35,Citation36].

In 2015, SR and SC partnered with Stanton Territorial Hospital’s former Elders’ Advisory Council on a review of hospital-based Indigenous wellness centres in Canada and Alaska [Citation23]. During our collaboration, the Elders emphasised the need to better understand how Indigenous patients and biomedical healthcare providers experience Indigenous wellness and healing at Stanton Territorial Hospital. Building on the Elders’ questions, we carried out a research study with two overarching objectives:

To describe Indigenous patients’ and biomedical healthcare providers’ experiences with the Indigenous wellness services at Stanton Territorial Hospital; and

To explore how patients and providers envision Indigenous healing successfully working with biomedical hospital care.

An in-depth analysis of the first objective is reported elsewhere [publication under review]. In this article, we report the findings from the second aim. That is, we describe the different models that participants proposed for Indigenous and biomedical healthcare collaboration and consider whether the models are likely to improve care for Indigenous patients who access care at Stanton Territorial Hospital.

Study context

Two initiatives featured greatly in the context for this study. First is the Indigenous Wellness Program at Stanton Territorial Hospital, which provides cultural supports to Indigenous patients within the physical walls of the hospital. The Indigenous Wellness Program is composed of eight full-time staff members, including an Elder-in-Residence, an Indigenous Wellness Program Manager, a Traditional Foods Coordinator, and five Indigenous Patient Liaisons. The Indigenous Wellness Program staff members work weekdays from 8:30am-4:30pm. As a group, they provide interpretation in seven of the nine official Indigenous languages of the NWT; offer cultural crafts, sewing, and kinship visits; and provide tea, bannock, and a traditional lunch to patients once a week. Additionally, the Elder-in-Residence attends rounds with doctors, visits patients, holds talking circles, and carries out smudging ceremonies.Smudging ceremonies are ceremonies where sacred medicines such as tobacco or sweetgrass are burned and the smoke is used to cleanse the mind, body, spirit, and emotions [Citation37,Citation38]. The Indigenous Wellness Program is central to this research because participants’ experiences with and perceptions of the current Indigenous wellness services at the hospital shaped their visions for how Indigenous healing could successfully work with biomedical hospital care.

Second is the Arctic Indigenous Wellness Foundation (AIWF), an Indigenous-led and self-determined non-profit organisation that offers Indigenous healing and medicines at an on-the-land wellness camp in Yellowknife. The AIWF’s camp is located about a 30-min walk from Stanton Territorial Hospital. The AIWF is important to this study because it was created by former Stanton Territorial Hospital and Government of the Northwest Territories Elders’ Advisory Council members in response to the need for Indigenous wellness services. The AIWF is currently in discussions with the Government of the Northwest Territories about building an Indigenous wellness centre beside Stanton Territorial Hospital and thus featured greatly in some of the proposed models.

Methods

This study received ethics approval from the University of Toronto’s Research Ethics Board (protocol #16705), a northern research licence from Aurora Research Institute (licence #38649), and a research agreement with the Northwest Territories Health and Social Services Authority. It was carried out from May 2018 – June 2022 and was overseen throughout by a territorial Indigenous Community Advisory Committee, which was made up of two Dene Elders and an Inuk health researcher. Collaboration with the Community Advisory Committee was grounded in community-based participatory research (CBPR) principles [Citation39,Citation40], which recognise and value the community as a partner throughout the research process [Citation39,Citation41,Citation42]. In CBPR, the research objectives and methods often stem directly from the interests and needs of the community and seek to build on and contribute to community strengths and resources [Citation43–47]. A research design was co-created with the Community Advisory Committee, which included: (1) 41 semi-structured interviews with Indigenous Elders, patient advocates, healthcare providers, hospital administrators, and policy makers; and (2) sharing circles with the same four Elders at three different points in the study. Interviews and sharing circles were chosen because they are a culturally respectful way of generating knowledge [Citation48].

Participants were recruited for interviews via purposive and snowball sampling (i.e. a method where participants who are already involved in the study share information about the opportunity to participate in the research with individuals whom they think may be interested). Because of COVID-19 pandemic restrictions on face-to-face gatherings, all interviews took place via telephone or videoconference – whichever was preferred by participants, and they ranged from 25 min − 2 hours, depending on participants’ preferences and availabilities. The interviews were carried out by a non-Indigenous researcher (SR) who had been living and working at a community-based research institute in Yellowknife for three and a half years. Though the researcher was not Indigenous, she had worked with the former Elders’ Advisory Council at Stanton Territorial Hospital and had extensive training and experience carrying out ethical, relational, and reciprocal research. In the interviews, participants were asked about their experiences with the current Indigenous wellness services and how they might envision Indigenous healing working successfully with biomedical hospital care in the future. Participants were recruited until saturation had been reached (i.e. no new concepts or ideas had been surfaced).

Altogether, 41 individuals participated in interviews (13 Elders and patient advocates, 16 healthcare providers at the hospital, 6 Indigenous Wellness Program staff, and 6 policy makers and hospital administrators). Of the 41 participants, 19 self-identified in the interviews as First Nations, Métis, or Inuit. The 19 Indigenous participants came from 14 communities, which represent eight Indigenous language groups in the NWT (Tłicho Yatì, Dëne Sułiné Yatié (Chipewyan), Cree, Dinjii Zhu’ Ginjik (Gwich’in), Sahtûot’inę (North Slavey), Dene Zhatié (South Slavey), Inuvialuktun, and Inuktitut).

Sharing circles were also a critical part of the research design because they helped to ensure that the substantive findings were attentive to Indigenous patients’ diverse perspectives. Sharing circles are similar to focus groups, where a group of individuals discuss a topic that has been identified by the researcher; however, they differ from focus groups because they can have a sacred meaning for many Indigenous peoples and communities. They involve “sharing all aspects of the individual – heart, mind, body and spirit – and permission is given to the facilitator to report on the discussions” [Citation49]p. 29). In our project, we called the circles “sharing circles” because this was the term used by the Elders who participated in them. The sharing circles comprised the same four Elders for the duration of the study. Two other Elders were members of the Community Advisory Committee. The sharing circle Elders were recruited using purposive sampling and were invited to participate because of their knowledge of and experiences with Indigenous healing and hospital care. Each sharing circle was about 1–2 hours in length. The same non-Indigenous researcher who carried out the interviews participated in the sharing circles. The first sharing circle took place before the interviews began and shaped the interview questions; the second took place after a preliminary analysis of the interview data and deepened interpretation; and the third took place near the end of the project and informed knowledge translation.

The data from the interviews and first sharing circle were analysed using thematic narrative analysis [Citation50–53]. A set of topical codes was generated based on key themes from the interviews and first sharing circle and these were categorised into three overarching conceptual models for Indigenous and biomedical healthcare collaboration. The draft models were then presented to the Elders in a second sharing circle, and the non-Indigenous researcher and Elders engaged in rich dialogue and discussion.

Results

Objective 1: Brief summary of participants’ experiences with the current Indigenous wellness services at Stanton Territorial Hospital

We first provide a brief summary of our findings about how Indigenous patients and biomedical healthcare providers experience the current Indigenous wellness services at Stanton Territorial Hospital because they help to contextualise the three models (i.e. Objective 2). An in-depth description of these findings has been reported elsewhere [publication under review]. Elders and patient advocates underscored that the current Indigenous wellness services play a crucial role at the hospital connecting patients with access to cultural supports, such as traditional foods. Participants perceived these services to be foundational to hospital care because they help many Indigenous patients feel connected to their culture, which supports healing. Participants also asserted the hospital was not effectively bringing Indigenous healing into hospital care. Organisational barriers, such as a lack of Indigenous governance at the hospital and restrictive hospital policies; and deep-seated forces, such as systemic racism, colonialism, and biomedical dominance, underlie the way that care is delivered at Stanton Territorial Hospital and impede Indigenous and biomedical healthcare collaboration.

Objective 2: Models of Indigenous and biomedical healthcare collaboration

When participants were asked how they envisioned Indigenous healing successfully working with biomedical hospital care, they proposed three models: the (1) integration; (2) independence; and (3) revisioning relationship models.

(1) Integration model

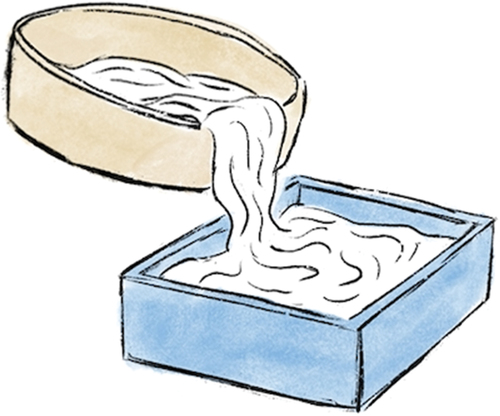

The integration model is visually portrayed with Indigenous healing practices (represented by a circle) being poured into a biomedical “square” because within this model, Indigenous healing practices are expected to “fit” within pre-existing biomedical healthcare policies and processes (see ). All the images in this paper © 2021 Rebecca Roher, published with permission.

This model was put forward by biomedical healthcare providers, all of whom were non-Indigenous. Participants who proposed the integration model envisioned an obvious presence for Indigenous healing practices within the hospital and a seamless way for Indigenous patients to access Indigenous approaches to healing. In the integration model, Indigenous healing practices would be incorporated within the hospital’s pre-existing programmes and processes and there would be a straightforward and simple way for Indigenous patients to navigate between the two healing modalities. For example, one healthcare provider described:

“I think [an improved collaborative model at the hospital] would probably exist as a referral system … some sort of streamlined process so that you can send patients along to the Wellness advisor and the Wellness advisor can get back to you and say, like, this is what we talked about, I will see them and follow-up at so-and-so time or in a certain amount of time. And they could probably just exist as one of the interprofessional team members and attend the meetings to talk about patient needs, logistics needs, social emotional needs, because I think all those things are really intertwined, like, they shouldn’t be in their silos. And if we have mostly Indigenous patients, Indigenous Wellness advisors should be brought into the fold about everything else that’s going on with their care”. (TThełjus, healthcare provider)

The proponents of the integration model asserted that Indigenous healing and medicines should be “integrated” into the hospital’s systems – sometimes through the hospital’s existing Indigenous Wellness Program and sometimes through the AIWF’s future Indigenous wellness centre. Some suggested that “Indigenous providers”, either from the hospital’s Indigenous Wellness Program or from the AIWF, should attend meetings with healthcare providers at the hospital (Túét’ané,Footnote1 healthcare provider). Others indicated that healthcare providers should refer patients to Elders (TThełjus, healthcare provider) or do rounds with Elders at the hospital (Ɂurádzı, healthcare provider). Supporters of the model explained that there are currently no formal processes in place for Indigenous and biomedical healthcare providers to work together at the hospital. As a result, even though healthcare providers may believe in Indigenous wellness services and want to work with Elders and Indigenous healing practitioners, they do not have the time, capability, or institutional support to do so (Sas delgaı, Túét’ané, Ɂurádzı, and TThełjus, healthcare providers). This model differs from the status quo because it establishes a clearer process for biomedical healthcare providers to access and work with Indigenous Wellness Program staff members and/or the AIWF’s staff members. Healthcare providers described that Indigenous healing will not work effectively at the hospital if it remains outside of the system and its existing processes. If Indigenous healing practices are too “independent”, then there is a risk that they will be overlooked, bypassed, and not improve patient care.

(2) Independence model

The independence model is depicted visually with Indigenous healing practices (represented as a circle) and biomedical healing practices (represented as a square) being offered to patients as two independent healing approaches. It is important in this model that there is space between Indigenous healing practices and biomedical healing practices to demonstrate that each healing approach operates separately (see ).

The independence model was proposed by two Elders. One Elder mentioned it briefly; the other discussed it in greater detail. The Elders believed that the best option for making Indigenous healing available to Indigenous patients at the hospital is to have Indigenous healing practices and medicines located outside of the hospital in a separate and independent Indigenous-led organisation. Indigenous patients could then choose which form of medicine they would access. One Elder asserted that the AIWF’s on-the-land wellness camp is the “best approach” and the “best way to go” because it is outside of Western policies (Det’anchogh, Elder). The Elder underlined that with non-Indigenous peoples holding leadership and decision-making roles at Stanton Territorial Hospital, Indigenous healing would not be understood or valued. The Elder noted: “it’s an uphill battle … in many ways we are up against everything. We are up against policies … If [Indigenous medicines and healing approaches] don’t follow … bylaws and regulation, well that’s it, you can’t do anything” (Det’anchogh, Elder). Whereas Indigenous healing would be expected to fit into pre-set hospital policies and ways of operating if delivered in a hospital setting, the AIWF’s soon-to-be-built wellness centre would offer a parallel healing track with independent Indigenous governance. This would help to ensure that the integrity of Indigenous healing practices is maintained. Although the Elders advocated for the independence of Indigenous healing offered through the AIWF, they believed that the Indigenous Wellness Program should remain to provide important cultural supports (such as traditional foods and interpretation services) to Indigenous patients receiving biomedical care at the hospital. The independence model envisioned the co-existence of the AIWF’s wellness centre and the Indigenous Wellness Program at Stanton Territorial Hospital.

(3) Revisioning relationship model

The revisioning relationship model is depicted visually with Indigenous healing practices (i.e. the circular door) and biomedical healing practices (i.e. the square door) offering two entry points into health and healing. In this model, individuals from each healing modality shake hands to demonstrate collaboration between Indigenous and biomedical healthcare practices and an openness and willingness to reimagine a new way of working together (see ).

Some Elders and patient advocates proposed the revisioning relationship model, where there would be a formal partnership agreement between the hospital and the AIWF so that Indigenous healing would be provided as an option to patients while they are receiving hospital care. A patient advocate shared that even though the AIWF currently offers Indigenous healing at its on-the-land wellness camp, its services are separate from those at the hospital because there are no processes in place for Indigenous and biomedical healthcare practitioners to work together. As a result, there are still individuals in the hospital who are not able to access Indigenous healing. The patient advocate explained:

There’s no thought or no opportunity or no looking at different ways of dealing with [health at the hospital outside of the Western biomedical perspective]. But that’s not to say that’s the medical profession’s fault. Because there is no place for a doctor to say: “well just wait. I’m going to go phone one of these traditional [Indigenous] healers”. You see what I mean? There’s no process in place for that anyways. I can’t say that it’s there because it isn’t there … So I don’t think too much that it’s not that people don’t want to or don’t care [to access Indigenous healing practices]. There just isn’t the opportunity or the means to have different therapy. (Yutthé́ ɂejéré, patient advocate)

The patient advocate suggested that to improve care for Indigenous patients at the hospital, there needs to be processes and policies in place for the AIWF staff and healthcare providers at the hospital to work with one another. On first glance, one might think that the patient advocate’s comments align with the healthcare providers who supported the integration model. However, it is important to note that this patient advocate expressed great concern that the health system is run by non-Indigenous peoples and emphasised how important it is for Indigenous healing practices to remain separate from the hospital. Indeed, the patient advocate suggested a new vision of partnership from the integration and independence models. They advocated for a middle-ground between the two other models proposed where the AIWF would offer Indigenous healing that is independent of hospital policies and where there is collaboration between Indigenous and biomedical health systems. Importantly, in this model, the AIWF is not intended to replace the current hospital-based Indigenous Wellness Program but instead to provide Indigenous healing in ways that the current Indigenous Wellness Program cannot.

Participants who advocated for the revisioning relationship model shared that for Indigenous and biomedical healthcare to work collaboratively, a new vision of healthcare would be needed where the AIWF Indigenous traditional care providers and biomedical healthcare providers work together within a collaborative model to provide culturally responsive health services to patients. This collaborative model involves imagining a new and different way of relating to one another – one that is based in co-existence, mutual respect, and equality. Rather than concentrate on what is not working, it calls for individuals to work towards the health system that they want to see. To engage in this kind imagination requires courage, hope, and trust.

Some participants who supported this model asserted that Indigenous and biomedical healthcare collaboration could happen if only the territorial government was interested and willing. For example, one Elder explained: “I think [collaboration between the AIWF and hospital] could be done if the government would go for it” (Mułtsagh, Elder). They continued:

I see that if we meet modern [biomedical] and traditional [Indigenous healing], merge them together, I know it could be done. It’s not simple. It’s very, very hard to try to convince everyone [at the hospital], okay, we’re going to work with the [Arctic Indigenous] Wellness Foundation … When [the Arctic Indigenous Wellness Foundation] build[s] [its] centre, I think there’s going to be a lot of rooms for teachings, and for both sites [to] start working together.

For this Elder, having the AIWF’s wellness centre beside the hospital would provide an opportunity for the AIWF staff and healthcare providers at the hospital to learn from one another and establish a new and positive relationship.

Discussion

While the literature in Canada to date outlines two overarching models for hospital-based Indigenous wellness services: (1) Indigenous wellness services in Indigenous-owned and operated hospitals and (2) Indigenous wellness services in mainstream hospitals, our study surfaced three distinct conceptual models for Indigenous and biomedical healthcare collaboration in mainstream hospitals. In this discussion, we consider the strengths and challenges of the conceptual models and consider key learnings that can be brought forward from the models to improve care for Indigenous patients.

The integration model was largely proposed by non-Indigenous biomedical healthcare providers. In this model, healthcare providers asserted that Indigenous healing practices and medicines should be further “integrated” into the hospital’s systems and incorporated within the hospital’s pre-existing programmes and processes. We understand this model as trying to “fit” Indigenous healing practices into the already established biomedical policies and practices. This model was seen by healthcare provider participants to improve care for Indigenous patients by ensuring that Indigenous healing is not overlooked in a hospital setting.

In previously reported studies from Canada and Alaska, a version of the integration model – one that is grounded in collaboration, respect, and equality – is considered an aspirational model for Indigenous and biomedical healthcare collaboration [Citation19,Citation22,Citation27,Citation54]. These studies suggest that the integration model could be successful and improve care for Indigenous peoples so long as there are meaningful Indigenous governance and strong relationships and trust formed between Indigenous healers and biomedical healthcare providers [Citation19,Citation22,Citation27,Citation54,Citation55].

However, the Canadian literature on Indigenous and biomedical healthcare collaboration also warns that when Indigenous and biomedical healing practices are brought together in a biomedical healthcare environment, there is a risk that the biomedical model will dominate and that Indigenous forms of healing will be subsumed and interpreted through a biomedical lens [Citation34,Citation56]. The risk of biomedical dominance was of particular concern for Indigenous participants in this study who felt that the current Indigenous wellness services were already expected to conform to biomedical policies and were determined by non-Indigenous peoples (see Objective #1). Additionally, while the literature suggests that Indigenous governance in mainstream hospitals could help to protect against the risk of Indigenous healing being defined by biomedical standards and perspectives [Citation19,Citation20,Citation22], participants’ visions for the integration model in this study did not include any form of Indigenous governance. As a result, we would argue that the integration model, as it was presented by participants – with no Indigenous governance – may be limited in its ability to improve access to Indigenous medicines at Stanton Territorial Hospital.

Alternatively, two Elders proposed the independence model where Indigenous healing practices and medicines would be located outside of Stanton Territorial Hospital and offered by the AIWF, an independent Indigenous-led organisation that is not beholden to Stanton Territorial Hospital’s policies. Proponents of the independence model asserted that having Indigenous healing and medicines available outside of the mainstream biomedical healthcare system would help to maintain the integrity of Indigenous healing practices. Importantly, the independence model is not merely a reaction to the integration model; it is a positive affirmation of the legitimate value of Indigenous healing practices – this value bears no relationship to and is entirely independent of non-Indigenous epistemology, ontology, and axiology as expressed in mainstream biomedical healthcare. The independence model is consistent with research in Canada which has shown that Indigenous patients often seek community-based Indigenous healing options and mainstream biomedical treatments as two distinct healing approaches [Citation20,Citation57].

While community-based Indigenous healing practices are common and widely used by many Indigenous peoples, they are oftentimes not recognised or respected by biomedical healthcare practitioners [Citation20,Citation58]. Several studies have demonstrated that healthcare providers may be hesitant to work with Indigenous healers because they do not understand or are distrustful of Indigenous medicines and healing practices [Citation8,Citation18–20,Citation34,Citation58], and Indigenous peoples may be hesitant to talk about Indigenous healing practices and medicines with biomedical healthcare providers [Citation19,Citation34]. This wariness has been attributed to a history of colonial policies where Indigenous healing practices were prohibited and outlawed [Citation34]. Indigenous participants in our study were greatly concerned that there was little respect for Indigenous healing practices and medicines at the hospital (Objective #1). Therefore, while the independence model has great potential to preserve, protect, and promote Indigenous healing practices, it may be less likely to improve care for Indigenous patients within the walls of the hospital if trust has not been built and maintained between Indigenous healers and biomedical healthcare providers.

Finally, the revisioning relationship model holds that Indigenous healing practices would be offered by the AIWF. In this model, the AIWF would still be connected to the hospital and provide Indigenous healing as part of hospital care, however, it would also be independent of hospital policies and processes. Proponents of this model called for the strengths of both Indigenous healing and biomedical hospital care to be recognised and valued without one way of knowing subsuming another. Additionally, supporters of this model asserted that, for Indigenous healing to work successfully with hospital care, a new vision for healthcare would be needed where the AIWF and biomedical healthcare providers at Stanton Territorial Hospital work together as equals to provide health services to patients. In this way, the revisioning relationship model is grounded in the principles of Indigenous self-determination and respect for Indigenous healing practices – both of which are presented as best practices in the literature for Indigenous and biomedical healthcare collaboration [Citation20,Citation27,Citation34,Citation54,Citation55]. While this model seems promising, one might ask: how can one revision hospital care, which is so deeply rooted in racism and colonialism and the dominance of the biomedical paradigm? We turn to the ethical space of engagement to help think about the principles and values that Stanton Territorial Hospital leadership and the AIWF might consider in forming a new relationship with one another.

Cree ethicist and legal scholar, Willie Ermine, proposed the ethical space of engagement as a theoretical principle that responds to the historical and ongoing harms committed towards Indigenous peoples in the context of colonialism. Ethical space describes a metaphorical, non-hierarchical meeting space, in which Western and Indigenous knowledge systems and worldviews come together [Citation59–61]. The goal of ethical space is to dialogue “in a cooperative spirit” [Citation59]p. 203); in this space, “allegiances and mental constraints dissipate for the purpose of reconciling differences and hearing each other” [Citation62]p. 49) and “new currents of thought flow in different directions and overrun the old ways of thinking” [Citation59]p. 203).

The ethical space of engagement can offer principles to guide the reimagined relationship between the AIWF and Stanton Territorial Hospital leadership in the revisioning relationship model. To create ethical spaces of engagement, the AIWF and senior hospital leadership could come together authentically and with the intention of respecting multiple worldviews and value systems. Instead of having a relationship that is marked by dominance and subjugation, ethical space calls for relationships to be formed with humility, openness, mutual respect, and equality [Citation63]. Once partnerships are built on these values, then the AIWF and hospital leaders could start to engage in meaningful dialogue about what Indigenous and Western healthcare collaboration could look like and how to build organisational structures that support both Indigenous and Western models of healing.

Participants who espoused the revisioning relationship model advocated for this kind of engagement. They felt that if different groups could come together in a spirit of openness and mutual respect, then the AIWF and senior leaders at Stanton Territorial Hospital could start to form a shared vision and imagine how they might respectfully work together to generate that vision. Instead of focusing on what they cannot do, this kind of transformative engagement calls for individuals to come together to imagine what they could do. In this model, individuals are afforded a kind of radical freedom where they can work together to fundamentally reimagine how to improve care for Indigenous patients at the hospital.

Policy and program directions

The three models for Indigenous and biomedical healthcare collaboration offer important policy and programme directions for Stanton Territorial Hospital. It is beyond the scope of this research to determine which, if any, of the three models proposed by participants should be pursued. Instead, key learnings from the models and an exploration of ethical space can start to frame how the AIWF and hospital leadership might approach conversations. If an ethical space of engagement can be fostered in these discussions – where the AIWF and Stanton Territorial Hospital leaders are able to dialogue in a spirit of openness, mutual respect, and collaboration – then there will be greater opportunity for a new relationship between Indigenous and biomedical healing practices to be formed and fostered.

Future research

Since this project was carried out during the COVID-19 pandemic, the research methods were adapted to online and telephone interviews and sharing circles. As a result, we decided to simplify the project logistics by carrying out interviews and sharing circles with English-language speakers. Conducting the study in English means that the findings do not reflect concepts and terms emanating from Indigenous languages, which would offer further insights. Additionally, since recruitment and data collection for this project took place within the COVID-19 pandemic, there was little opportunity in the project to solicit participation from under-represented populations such as Indigenous peoples who are unhoused in Yellowknife, individuals who do not have access to telephone or videoconference, and individuals who, for various reasons, choose not to access hospital services. Similarly, the research does not include the experiences of younger populations (those less than 18 years old) and residents of the Kitikmeot Region of Nunavut who access care at Stanton Territorial Hospital. It is important for future research to include the experiences of these populations and to meaningfully incorporate Indigenous languages into the research design and analysis.

While the number of Indigenous wellness services in mainstream hospitals continues to rise, there is very limited published research that examines hospital-based Indigenous wellness services in Canada. Future research could explore how Indigenous patients and healthcare providers in other regions imagine Indigenous and biomedical healing practices successfully working together. These responses could then be compared across study regions and provide insights for deeper learning in a Canadian context.

Conclusion

This article reports findings from a community-engaged qualitative study which sought to explore how Indigenous patients and biomedical healthcare providers envision Indigenous healing programmes successfully working with biomedical hospital care at Stanton Territorial Hospital in Yellowknife, NWT. Participants responses illuminated three models for Indigenous and biomedical healthcare collaboration – the integration, independence, and revisioning relationship models. When examined together, the models demonstrate a need for new ways of thinking about and delivering healthcare at Stanton Territorial Hospital. These new ways must be grounded in Indigenous self-determination and recognise the value of Indigenous healing practices.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to express their gratitude to the interview and sharing circle participants who generously shared their knowledge and experiences. Mahsi cho to Community Advisory Committee members Elder Felix Lockhart, Elder Paul Andrew, and Kimberly Fairman for their guidance throughout, and to Sabet Biscaye for providing interpretation support. Images in this paper () © 2021 Rebecca Roher, published with permission.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 The Community Advisory Committee recommended that each participant be assigned a pseudonym in Déne Sułıne that corresponds to an animal, insect, or bird in the NWT.

References

- Allan B, Smylie J. First peoples, Second class Treatment: the role of racism in the health and well-being of indigenous peoples in Canada executive Summary. Toronto; 2015. http://www.wellesleyinstitute.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/Summary-First-Peoples-Second-Class-Treatment-Final.pdf

- Bird H. Inuvialuit woman says uncle’s stroke mistaken for drunkenness. CBC News North. Yellowknife; 2016, August. https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/north/hugh-papik-stroke-racism-1.3719372

- Government of the Northwest Territories. Recommendations from the external investigation. An investigation into the Death, for All Health Care Workers. Yellowknife; 2017. https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/north/hugh-papik-aklavik-stroke-death-review-recommendations-1.4001279#:~:text=

- Health Council of Canada. Empathy, dignity, and respect: creating cultural safety for Aboriginal people in urban health care; 2012. http://cahr.uvic.ca/nearbc/media/docs/cahr50d1611574ca1-aboriginal_report_en_web_final.pdf

- Lowrie M, Malone KG. Joyce echaquan’s death highlights systemic racism in health care, experts say. CTV News; 2020, October 4. https://www.ctvnews.ca/health/joyce-echaquan-s-death-highlights-systemic-racism-in-health-care-experts-say-1.5132146

- The Brian Sinclair Working Group. Out of Sight. A summary of the events leading up to Brian Sinclair’s death and the inquest that examined it and the interim recommendations of the Brian Sinclair working group. Winnipeg; 2017. https://professionals.wrha.mb.ca/old/professionals/files/OutOfSight.pdf

- Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. Honouring the Truth, reconciling for the future: summary of the final report of the truth and reconciliation commission of Canada; 2015. Available from: http://www.trc.ca/websites/trcinstitution/File/2015/Honouring_the_Truth_Reconciling_for_the_Future_July_23_2015.pdf

- Turpel-Lafond ME. In plain sight: addressing indigenous-specific racism and discrimination in B.C. Health Care; 2020. Available from: https://engage.gov.bc.ca/app/uploads/sites/613/2020/11/In-Plain-Sight-Summary-Report.pdf

- Browne AJ, Fiske J. First nations women’s encounters with mainstream health care services. West J Nurs Res. 2001;23(2):126–12. Retrieved from: https://journals-scholarsportal-info.proxy.bib.uottawa.ca/pdf/01939459/v23i0002/126_fnwewmhcs.xml

- Cooper R, Pollock NJ, Affleck Z, et al. Patient healthcare experiences in the Northwest Territories. Canada: an analysis of news media articles; 2021. doi: 10.1080/22423982.2021.1886798

- Goodman A, Fleming K, Markwick N, et al. “They treated me like crap and I know it was because i was native”: the healthcare experiences of aboriginal peoples living in vancouver’s inner city. Soc Sci Med. 2017;178:87–94. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.01.053

- Hole RD, Evans M, Berg LD, et al. Visibility and voice: aboriginal people experience culturally safe and unsafe health care. Qual Health Res. 2015;25(12):1662–1674. doi: 10.1177/1049732314566325

- Jacklin KM, Henderson RI, Green ME, et al. Health care experiences of Indigenous people living with type 2 diabetes in Canada. CanMed Assoc J. 2017;189(3):E106–E112. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.161098

- Auger M, Howell T, Gomes T. Moving toward holistic wellness, empowerment and self-determination for indigenous peoples in Canada: can traditional indigenous health care practices increase ownership over health and health care decisions? Can J Public Health. 2016;107(4–5):e393–e398. doi: 10.17269/CJPH.107.5366

- Maar M, Erskine B, McGregor L, et al. Innovations on a shoestring: a study of a collaborative community-based Aboriginal mental health service model in rural Canada. Int J Ment Health Syst. 2009;3(1):27. doi: 10.1186/1752-4458-3-27

- Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples. Volume 3 Gathering Strength. Ottawa; 1996. Available from: http://data2.archives.ca/e/e448/e011188230-03.pdf

- United Nations General Assembly. United nations declaration on the rights of indigenous peoples. United Nations; 2007. Available from: https://www.un.org/development/desa/indigenouspeoples/wp-content/uploads/sites/19/2018/11/UNDRIP_E_web.pdf

- Allen L, Hatala A, Ijaz S, et al. Indigenous-led health care partnerships in Canada. CanMed Assoc J. 2020;192(9):E208–E216. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.190728

- Maar, Shawande M. Traditional Anishinabe healing in a clinical setting: design of comprehensive hospital model for traditional healing, medicines, foods and supports. J Aborig Health. 2010;6(1):18–27. https://jps.library.utoronto.ca/index.php/ijih/article/view/28993

- Manitowabi D, Shawande M. Negotiating the clinical integration of traditional Aboriginal medicine at Noojmowin Teg. Can J Native Stud. 2013;33(1):97–124.

- Marchildon GP, Lavoie JG, Harrold HJ. Typology of indigenous health system governance in Canada. Can Public Administration. 2021;64(4):561–586. doi: 10.1111/CAPA.12441

- Walker R, Cromarty H, Linkewich B, et al. Achieving cultural integration in Health services: design of comprehensive hospital model for traditional healing, medicines, foods and supports. Int J Indigenous Health. 2010;6(1):58–69. doi: 10.3138/ijih.v6i1.28997

- Institute for Circumpolar Health Research. Report on needs for Aboriginal wellness at Stanton Territorial hospital Authority. Yellowknife; 2016. https://www.hss.gov.nt.ca/sites/hss/files/resources/report-needs-aboriginalwellness-stanton-territorial-hospital.pdf

- Northwest Territories Health and Social Services Authority. NTHSSA leadership Council governance manual. Yellowknife; 2019. Available from: https://moz-extension://47fcd069-1f59-5641-b010-a09b2fb42f8d/enhanced-reader.html?openApp&pdf=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.nthssa.ca%2Fsites%2Fnthssa%2Ffiles%2Fresources%2Fgovernance_manual_-_august_2019_-_final.pdf

- Southcentral Foundation. Nuka system of care. [cited 2021 Nov 23]; 2021. https://www.southcentralfoundation.com/nuka-system-of-care/

- Huhndorf S. Native wisdom is revolutionizing health care. Stanford Social Innovation Review: Informing And Inspiring Leaders Of Social Change; 2017. Available from: https://ssir.org/articles/entry/native_wisdom_is_revolutionizing_health_care#

- Gottlieb K. The Nuka system of care: improving health through ownership and relationships. Int J Circumpolar Health. 2013;72(1):2242–3982. doi: 10.3402/ijch.v72i0.21118

- Campbell MA, Hunter J, Scrimgeour DJ, et al. Contribution of Aboriginal community-controlled health services to improving Aboriginal health: an evidence review. Aust Health Rev. 2017;42(2):218–226. doi: 10.1071/ah16149

- Hiscock EC, Stutz S, Mashford-Pringle A, et al. An environmental scan of Indigenous patient navigator programs in Ontario. Healthc Manage Forum. 2022;084047042110676. doi: 10.1177/08404704211067659

- Link CM. “We are bridging that gap”: insights from indigenous hospital liaisons for improving Health care for Indigenous patients in Alberta. University of Calgary; 2020. https://prism.ucalgary.ca/bitstream/handle/1880/112249/ucalgary_2020_link_claire.pdf?sequence=2&isAllowed=y

- Maar M. Clearing the path for community health empowerment: integrating health care services at an aboriginal health access centre in rural north central Ontario. J Aborig Health. 2004;1:55–64.

- National Collaborating Centre for Aboriginal Health. We are welcome here: changing hospital care in Canada; 2019. https://www.nccah-ccnsa.ca/323/We_are_Welcome_Here__Changing_Hospital_Care_in_Canada.nccah

- Drost JL. Developing the alliances to expand traditional Indigenous healing practices within Alberta Health services. J Altern Complementary Med. 2019;25(S1):S69–S77. doi: 10.1089/acm.2018.0387

- Hill DM. Traditional Medicine In Contemporary Contexts: Protecting And Respecting Indigenous Knowledge And Medicine; 2003. Available from: http://www.naho.ca/documents/naho/english/pdf/research_tradition.pdf

- Government of the Northwest Territories. Population estimates by community; 2018 [cited 2019 July 9]. https://www.statsnwt.ca/population/population-estimates/bycommunity.php

- Statistics Canada. Census profile, 2016 census - Kitikmeot, Region [census division], Nunavut And Nunavut [territory]; 2016. [cited 2023 March 16]. https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2016/dp-pd/prof/details/page.cfm?Lang=E&Geo1=CD&Code1=6208&Geo2=PR&Code2=62&SearchText=Kitikmeot&SearchType=Begins&SearchPR=01&B1=All&GeoLevel=PR&GeoCode=6208&TABID=1&type=0

- Indigenous Inclusion Directorate Manitoba Education and Training. Smudging protocol and guidelines smudging protocol and guidelines for school divisions 2019 indigenous inclusion directorate Manitoba education and Training. Winnipeg; 2019. https://www.edu.gov.mb.ca/iid/publications/pdf/smudging_guidelines.pdf

- Robinson A. Smudging. In The Canadian Encyclopedia; 2018. https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/smudging

- Israel BA, Schulz AJ, Parker EA, et al. Review of community-based research: assessing partnership approaches to improve Public Health. Ann Rev Public Health. 1998;19(1):173–202. doi: https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.publhealth.19.1.173

- Sinclair R. Aboriginal Social work education in Canada: decolonizing pedagogy for the seventh generation. First Peoples Child & Family Rev. 2004;1(1):49. doi: 10.7202/1069584ar

- Stanton CR. Crossing methodological borders: decolonizing community-based participatory research. Qual Inq. 2014;20(5):573–583. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/1077800413505541

- Stewart S, Riecken T, Scott T, et al. Expanding Health Literacy Indigenous Youth Creating Videos. J Health Psychol. 2008;13(2):180–189. doi: 10.1177/1359105307086709

- Castleden HE, Morgan VS, Lamb C. “I spent the first year drinking tea”: exploring Canadian university researchers’ perspectives on community-based participatory research involving Indigenous peoples. Can Geogr. 2012;56(2):160–179. doi: 10.1111/j.1541-0064.2012.00432.x

- Manitowabi D, Marion M. Applying Indigenous Health community-based participatory research. In: McGregor D, Restoule J-P, and Johnston R, editors. Indigenous research: theories, practices, and relationships. Toronto: Canadian Scholars’ Press; 2018. p. 155–171.

- McGregor L. Conducting community-based research in First nation communities. In: Deborah McGregor J-P-R Johnston R, editors Indigenous research: theories, practices, and relationships. Toronto: Canadian Scholars Press; 2018. pp. 129–141.

- Minkler M, Wallerstein N. Introduction to community-based participatory research: new issues and emphases. In: Meredith Minkler, Nina Wallerstein, editors. Participatory research for health: from process to outcomes. 2nd ed. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2008. p. 5–23.

- Wallerstein N, Duran B. Using community-based participatory research to address health disparities. Health Promot Pract. 2006;7(3):312–323. doi: 10.1177/1524839906289376

- McGregory D, Bayha W, Simmons D. “Our responsibility to keep the land alive”: voices of Northern Indigenous researchers. Pimatisiwin. 2010;8(1):101–123.

- Lavallée LF. Practical application of an indigenous research framework and two qualitative indigenous research methods: sharing circles and anishnaabe symbol-based reflection. Int J Qual Methods. 2009;8(1):21–40. doi: 10.1177/160940690900800103

- Frank AW. What is dialogical research, and why should we do it? Qual Health Res. 2005;15(7):964–974. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732305279078

- Frank AW. Letting stories breath: a socio-narratology. In: Literature and medicine. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 2010. doi: 10.7208/chicago/9780226260143.001.0001

- Martin DH. Food stories: A Labrador Inuit-Metis community speaks about global change. Dalhousie University; 2009. https://dalspace.library.dal.ca/bitstream/handle/10222/12354/Martin_Dissertation.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

- Riessman CK. Narrative methods for the human sciences. Sage. London; 2008. Available from: http://opac.rero.ch/get_bib_record.cgi?db=ne&rero_id=R004646140

- Redvers N, Marianayagam J, Blondin B. Improving access to Indigenous medicine for patients in hospital-based settings: a challenge for health systems in northern Canada. Int J Circumpolar Health. 2019;76(2):1589208. doi: 10.1080/22423982.2019.1589208

- National Aboriginal Health Organization (NAHO) = Organisation nationale de la santé autochtone (ONSA). 2008. An overview of traditional knowledge and medicine and public health in Canada. Ottawa.

- Hollenberg D, Muzzin L. Epistemological challenges to integrative medicine: an anti-colonial perspective on the combination of complementary/alternative medicine with biomedicine. Health Sociol Rev. 2010;19(1):34–56. doi: 10.5172/HESR.2010.19.1.034

- Cook SJ. Use of traditional Mi’kmaq medicine among patients at a First Nations community health centre. Can J Rural Med. 2005;10(2):95–99.

- Achan GK, Eni R, Kinew KA, et al. The two great healing traditions: issues, opportunities, and recommendations for an integrated First Nations healthcare system in Canada. Health Syst Reform. 2021;7(1). doi: 10.1080/23288604.2021.1943814

- Ermine W. The ethical space of engagement. Indig Law J. 2007;6(1):193–203. doi: 10.3868/s050-004-015-0003-8

- Ermine W. Willie Ermine: what is ethical space? 2011. [Cited 2018 Feb 13]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=85PPdUE8Mb0

- Nelson SE. “They seem to want to help me”: health, rights, And Indigenous Community Resurgence In Urban Indigenous Health Organizations. University of Toronto; 2018. Available from: https://tspace.library.utoronto.ca/bitstream/1807/95932/3/Nelson_Sarah_E_201906_PhD_thesis.pdf

- Peltier C, Manankil-Rankin L, McCullough K, et al. Self-Location and ethical space in wellness research. Int J Indigenous Health. 2019;14(2):39–53. doi: 10.32799/ijih.v14i2.31914

- Whiting C, Cavers S, Bassendowski S, et al. Using two-eyed seeing to explore interagency collaboration. Can J Nurs Res. 2018;50(3):133–144. doi: 10.1177/0844562118766176