ABSTRACT

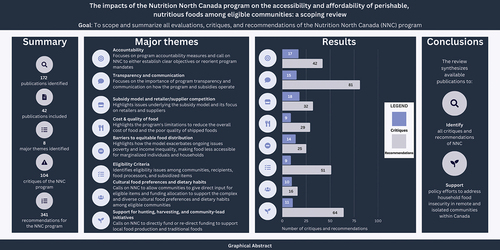

The Nutrition North Canada (NNC) program, introduced in April 2011 is a federal strategy to improve access to perishable, nutritious foods for remote and isolated communities in northern Canada by subsidising retailers to provide price reductions at the point of purchase. As of March 2023, 123 communities are eligible for the program. To evaluate existing evidence and research on the NNC program to inform policy decisions to improve the effectiveness of NNC. A scoping review of peer-reviewed articles was conducted in ten databases along with a supplemental grey literature search of government and non-government reports published between 2011 and 2022. The search yielded 172 publications for screening, of which 42 were included in the analysis. Narrative thematic evidence synthesis yielded 104 critiques and 341 recommendations of the NNC program across eight themes. The most-identified recommendations focus on transparency, communication, and support for harvesting, hunting, and community food initiatives. This review highlights recommendations informed by the literature to address critiques of the NNC program to improve food security, increase access to perishable and non-perishable items, and support community-based food initiatives among eligible communities. The review also identifies priority areas for future policy directions such as additional support for education initiatives, communication and transparency amidst program changes, and food price regulations.

Introduction

Food security is a multidimensional concept that refers to a state in which people have physical, economic, and social access to sufficient, safe, and nutritious food to meet their dietary needs and food preferences for an active and healthy life. The general concept is characterised by four dimensions: availability (supply and production), access (economic and physical), utilisation (nutritional status), and stability (of the three dimensions) [Citation1]. Household food insecurity (HFI) is not the opposite of food security. Rather, it is characterised as inadequate or insecure access to enough food, or the fear that one will run out of food, due to financial constraints [Citation2]. Household food insecurity is an important public health problem in Canada with heightened vulnerability in Northern remote regions of Canada, which are predominantly occupied by Indigenous communities. In 2017–2018, off-reserve estimates of HFI in Nunavut (57.1%), Northwest Territories (21.6%), and Yukon (16.9%) greatly surpassed the national average of 12.7% [].Footnote1 HFI prevalence is also substantially elevated among Inuit living in Inuit Nunangat (76.3%) and among First Nations households in remote communities (32.4% moderately food insecure, 9.3% severely food insecure) and special access communities (45.2% moderately food insecure, 20.1% severely food insecure) [Citation3–5].Footnote2

A comprehensive approach to food security among remote Indigenous communities considers traditional food systems, which are intimately tied to identity and culture but otherwise overlooked by traditional food security measures [Citation6,Citation7]. For example, sufficient access in an Indigenous food security framework includes access to country or traditional food fished, gathered, or hunted from water, land, or sky, in addition to market food purchased from a retailer [Citation1,Citation6,Citation8]. Consequently, interventions or evaluations made to address the dimension of availability must consider the impact of climate change and environmental contaminants on traditional food sources [Citation8,Citation9]. These considerations form a key component of the concept of food sovereignty, a transformative framework that extends beyond the concept of food security by emphasising the individual right to define one’s own food systems and policies, ultimately putting more control into the hands of those who have been systematically excluded from the formulation of food policy [Citation10–12]. Food sovereignty looks to ensure food security by strengthening self-sufficiency, social equity, and livelihood [Citation13]. Despite the importance of the concept of food sovereignty, most work in this area in the north has continued to primarily use a food security lens [Citation14].

The Government of Canada launched the Nutrition North Canada (NNC) program in April 2011 to replace the longstanding Food Mail Program (1960s-2011). The program aims to increase accessibility and affordability of perishable, nutritious food and eligible non-food items for residents of isolated northern communities by providing market subsidies to local registered retailers, distributors, and suppliers who pass the subsidy to consumers through price reductions on eligible items [Citation15–18]. To be eligible for the market subsidy, communities must meet the following requirements: 1) lack year-round surface transportation (no permanent road, rail, or marine access), excluding isolation caused by freeze-up and break-up that lasts less than four weeks at a time; 2) meet the territorial or provincial definition of a northern community; 3) have an airport, post office, or grocery store and; 4) have a year-round population according to the national census [Citation4].

Although NNC has been modified several times in response to critiques from communities and experts, no comprehensive synthesis of NNC evaluations, recommendations, or critiques currently exists. The purpose of this scoping review is to identify such publications, summarise the reported outcomes, and thematically synthesise the results, criticisms, and recommendations in order to yield a comprehensive overview of program impact, strengths, and weaknesses, which can be used to inform evidence-based decision-making.

Methods

Objectives and protocol

A scoping review of peer-reviewed and grey literature (e.g. government reports) was conducted in accordance with a review protocol published a priori (OSF.IO/A9B8V) [Citation19]. Four objectives were defined [Citation1]: to identify all publications relating to the NCC program, and to summarise [Citation2] all evaluations of the program at the outcome level [], all critiques of, and [Citation3] all recommendations for the program.

Literature search

A search strategy to identify all publications evaluating, critiquing, or providing recommendations for NNC since its inception in 2011 was created in consultation with information specialists at the Health Canada Library (Box 1, supplementary material). The search, carried out in June 2022 and limited to publications in English or French, covered ten databases (Embase, Medline, Global Health, APA PsycInfo, SCOPUS, Econlit, Business source elite, Food Science and Technology Abstracts, Pubmed, and CAB Abstracts). These databases were chosen to cover the main topics related to NNC such as food security, food policy, and health. Given the scarcity of research-based literature on NNC, the database search was complemented by a hand-search of English and French grey literature provided by a health librarian that suggested search strings and a list of databases to help identify relevant publications. Two reviewers independently searched the resources and collected every publication that mentioned NNC [Citation20]. Three subject matter experts were consulted to identify any additional publications.

Eligibility criteria

All published peer-reviewed studies, theses, or commentaries that evaluated or provided critiques and/or recommendations for NNC were included regardless of design. Published reports by government agencies, Indigenous organisations, and other non-government organisations (e.g. Food Secure Canada) were also included. Where publications were available in both French and English, the English version was assessed. Materials prepared for political campaigns, pre-prints, educational materials (e.g. brochures), and publications that did not include an evaluation, critique, or recommendation relating to NNC were excluded. A full list of inclusion and exclusion criteria is available in the review protocol (OSF.IO/A9B8V).

Study selection, data extraction, and synthesis

DistillerSR [Citation21], a web-based systematic review management software, was used to facilitate screening and data extraction via standardised forms (supplementary material) developed a priori (JP, AZ) and piloted by the review team. Any publication that did not formally evaluate NNC were screened with questions adapted from the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) critical appraisal tool with publications that required to meet all checklist criteria for inclusion. This was to ensure that included publications contained critiques, recommendations of NNC and was the result of an analytic process, from a standing of expertise, and based on the interests of eligible communities. References were independently screened for inclusion by two reviewers. Following relevance assessment of title and abstract (JP, LI), references were moved to full-text evaluation, unless both reviewers indicated exclusion was warranted. Full-text eligibility assessment (JP, CL, EV, LI) required consensus between reviewers. Conflicts were resolved by discussion or by arbitration by a third reviewer. Data extraction (JP, CL, EV, LI) was performed according to Cochrane and JBI guidance [Citation22,Citation23]. Using a sequential dual-reviewer approach, citation details, study information (objectives, study design, time period, outcomes), a description of the methods, critiques, and recommendations were extracted by one reviewer and validated by a second. Inconsistencies in extracted data were resolved as above.

The included studies were separated into two categories [Citation1]: studies that evaluated the NNC program, and [Citation2] studies that assessed critiques and recommendations provided for the NNC program. Studies could be included in both categories. Evaluations were synthesised based on method and outcomes. Given the wide range in the quality of studies providing critiques and recommendations, an adapted version of the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) critical appraisal tool [Citation24] for systematic reviews of text and opinion was used to ensure that the included studies met a minimum standard for quality. i.e. studies had to meet all checklist criteria for inclusion (available in the study protocol). The recommendations and critiques were then categorised via open coding wherein the identified keywords were grouped into key themes [Citation22,Citation25,Citation26].

Post data analysis, it was deemed necessary to consult NNC officials in order to contextualise the findings as well as identify any recommendations or critiques previously addressed with changes to the program.

Results

Literature identification

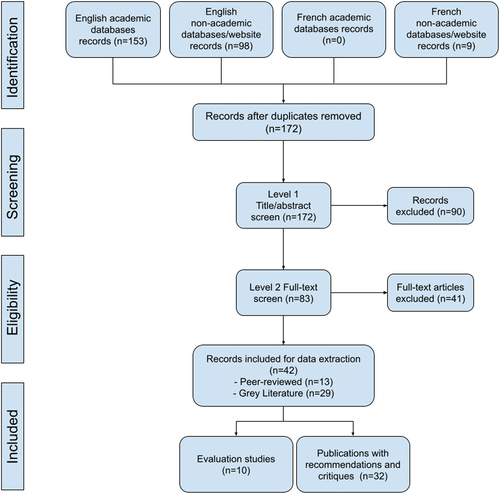

Of 172 unique publications identified, 42 met inclusion criteria, most (n = 29, 69%) of which were not peer reviewed (). Ten studies (22%) evaluated NNC and 32 (78%) publications provided critiques of and/or recommendations for the program.

NNC evaluations

Ten publications evaluated the NNC program () [Citation16,Citation27–35]. Two used stakeholder consultation to develop critiques and recommendations [Citation27,Citation29], three publications relied on data analysis [Citation16,Citation33,Citation35], and three publications employed both methods [Citation30,Citation32,Citation34]. One incorporated stakeholder consultation, data analysis, and expert opinion [Citation28]. Evaluations broadly focused on one of three NNC aspects: outcomes related to food, program structure, and priorities of community members.

Table 1. Publication description of program evaluations (*Independent research group commissioned by government department).

Evaluation of outcomes related to food

Studies evaluating the impact of NNC on food outcomes reported mixed effects. St-Germain et al. found that food insecurity in Nunavut increased by 13.2% (95% CI: 1.7–24.7) 1 year after the implementation of the program, suggesting that this effect may have been due to a shift in program focus from non-perishable to perishable food [Citation33]. Evidence regarding price reductions was mixed. In assessing subsidy pass-through rates, Naylor et al. reported that NNC was effective in reducing food prices in Nunavut, with this effect more pronounced in larger communities [Citation35]. Similarly, the National Research Group, in their 2014 review of retail operations, found demographics of markets, and competitions in food markets of all 104 communities served by NNC, that the program led to lower food costs and improvements to food quality but that prices were higher in communities with only one retailer [Citation29]. An evaluation by the department implementing the program, CIRNAC,Footnote3 found that NNC had reduced food prices and increased access to nutritious food, but that the latter aspect required additional improvements [Citation28]. Further to this, an independent evaluation by Galloway highlighted inequities in pricing and food delivery between regions and communities [Citation16]. Duhaime et al., interviewing Nunavik store owners to determine changes in food prices, found no change to the comparative food price index between April 2011 and April 2013 [Citation32]. However, detailed analysis found that, while perishable food prices decreased, prices for frozen perishable products and non-perishable products increased during this time. In addition, food remained more than 50% more expensive in Nunavik than in the rest of Quebec. A 2020 evaluation co-conducted by CIRNAC also found that, while NNC reduced prices for some food items, “Level 2” products were subsidised at lower rates and therefore resulted in minimal savings for the purchaser [Citation34]. Certain items in “Level 2” are considered staples and are reportedly in high demand. The same report noted that larger subsidies are associated with greater consumption of healthy foods and that NNC had limited impact on processing and shipping of traditional food.

Evaluation of program structure

The government department responsible for this program, CIRNAC, carried out an extensive evaluation of NNC in 2013 focusing on program relevance, design, performance, and cost effectiveness [Citation28]. The report found that NNC was aligned with the priorities, roles, and responsibilities of the federal government, made use of a well-established supply chain model, had facilitated engagement with communities (though further educational initiatives were needed), and was overall reaching a large subset of the eligible population. However, several shortcomings remained to be addressed. These included issues in inter-departmental communication, the role of the advisory board and oversight committee, and budgetary concerns, chiefly the susceptibility of the program to fluctuations in weather and associated infrastructure costs, insufficient funds for community-led initiatives, and incomplete implementation of cost containment strategies. Concerns around eligibility criteria, lack of support for country foods, and data collection were echoed by Galloway, who noted the inherent limitations of the subsidy approach in their evaluation of the program, a lack of program responsiveness, as well as needed improvements in measurement and reporting [Citation16]. Finally, the initial CIRNAC evaluation identified a need for more educational campaigns, an issue also noted the 2020 evaluation which integrated key-informant interviews, focus groups, literature review, and data analysis and found that communication efforts had not resulted in higher awareness or understanding of NNC, but that community nutrition education initiatives continue to grow.

Community priorities identified in the evaluations

The First Report of the Advisory Board for NNC, summarising the input received from communities and retailers after the first year of program implementation, identified several areas for improvement: communication, issues around education and accessibility (subsidised food lists, personal/direct ordering), issues around funds (transition funds, subsidy rates, retail prices and cost of living), issues related to program structure (the model itself, alignment with other northern subsidies), and traditional food [Citation27]. The engagement report by Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada, based on data from 16 town hall sessions held across all NNC-eligible provinces and territories, found many of the same topics of concern with communication (including transparency) and program structure (sustainability and long-term management, cost-effectiveness, capacity/efficiency including lack of inter-departmental government cooperation), as well as concerns around NNC fairness and consistency [Citation30]. The importance of the traditional food, as well as a higher demand for traditional food knowledge, was identified as a priority for NNC-eligible communities in all evaluations in this category [Citation29,Citation30,Citation34]. Finally, the 2020 CIRNAC/Prairie Research Associates evaluation additionally reported a higher demand for retail-based nutrition knowledge including selection and preparation of healthy and traditional food, in-store demonstrations, and cooking classes [Citation34].

Critiques and recommendations

Reports of critiques and recommendations were assessed according to a modified JBI critical appraisal tool for systematic reviews of text and opinion to ensure that only critiques and recommendations from reputable sources were included. A total of 42 publications were included with 34/42 (81%) publications providing critiques of NNC in which 104 critiques were identified. Additionally, 38/42 (90.5%) publications provided recommendations for NNC for a total of 341 recommendations (). Among publications authored by Indigenous organisations, 51/341 (15%) of recommendations were identified (Supplementary table 1).

Table 2. Overview of critiques and recommendations by theme.

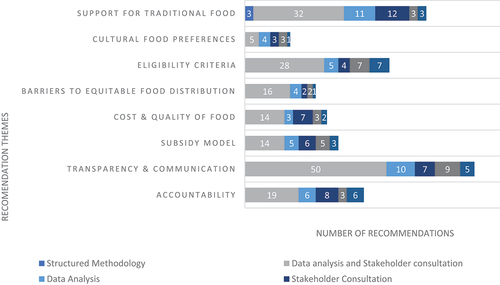

A variety of methods were used to generate critiques and recommendations (As seen in ). One publication used a structured methodology, eight publications used data analysis and stakeholder consultation, 16 used only data analysis, five used stakeholder consultation, six were based on expert opinion, and six used other methodologies (such as literature review, performance audit report, Northern Food Basket methodology, or if details were not provided). A breakdown of the 341 recommendations by theme and methodology type can be seen in .

Figure 2. Bubble plot of NNC recommendations by year, theme, and number of publications. The size of a bubble is proportional to the number of recommendations identified in the year and theme corresponding to the bubble coordinates.

Critiques and recommendations were organised by eight major themes: i) Accountability, ii) Transparency and communication, ii) Subsidy model and retailer/supplier competition, iv) Cost and quality of food, v) Barriers to equitable food distribution, vi) Eligibility criteria, vii) Support for hunting, harvesting, and community-food initiatives, and viii) Cultural food preferences and dietary habits. Recommendations were organised into further sub-themes. The distribution of recommendations by sub-themes can be found in .

Overall, the three most identified themes for the critiques are subsidy model and retailer/supplier competition (17.3%), accountability (16.3%), and transparency and communication (14.4%). Among recommendations, transparency and communication (24.5%), support for harvesters, hunting, and community food initiatives (19.3%), and eligibility (15.4%) make up more than half of the total recommendations. Most recommendations made by Indigenous organisations (Supplementary Table 1) are cost and quality of food (17.6%), eligibility (15.7%), and support for harvesters, hunting, and community food initiatives (15.7%).

Accountability

Accountability critiques highlight the shortcomings of the NNC program, such as its ability to achieve program objectives. For example, some critics noted that the program may not have the data or measurement strategies to show it achieves its intended outcomes [Citation34,Citation36–42]. Furthermore, others argued that although NNC reduced the cost of food, it is not considered a long-term solution to reduce food insecurity nor its root causes [Citation34,Citation37,Citation39,Citation43–46].

A number of recommendations were identified to address accountability issues such as revising or increasing program scope to address household food insecurity, or flexibility to support community initiatives such as school meal programs or food banks [Citation30,Citation37,Citation39,Citation45,Citation47–49]. Others suggest a re-allocation of funding such as subsidising food production, transportation of traditional foods, or increasing funding for nutrition education initiatives [Citation30,Citation39,Citation45,Citation50,Citation51]. Finally, improvements to support program goals were identified such as in-depth comprehensive reviews of NNC, exploring alternate energy sources and transportation routes, and establishing pricing benchmarks [Citation30,Citation31,Citation39,Citation44,Citation47,Citation52–55].

Transparency and communication

Based on critiques identified in the literature, it was found that there was confusion about how the program operates and what measures were used to demonstrate its effectiveness. For example, it is unclear how subsidies were being passed onto consumers based on available metrics [Citation36,Citation38–40,Citation56–58]. Furthermore, the lack of communication regarding the NNC program led to a misunderstanding of how the program works among recipients [Citation47,Citation52]. Finally, the distribution of funding for NNC education initiatives was unclear, suggesting that funds may not be not equally distributed in northern regions [Citation49].

Among the recommendations identified to improve NNC’s transparency and communication, a majority suggest improvements to the NNC program’s transparency, for example, establishing new evaluation measures and analytical tools to determine the effectiveness of the program, and disclosure of subsidy-level calculations [Citation28,Citation30,Citation31,Citation37,Citation39,Citation40,Citation44,Citation47,Citation53,Citation56,Citation57,Citation59]. Additionally, recommendations identified suggest NNC increase communication efforts such as public engagement meetings, a revision of communication strategies, and for NNC to provide information in regional dialects [Citation27,Citation29,Citation30,Citation39,Citation53,Citation57]. Lastly, additional support for outreach activities such as funding allocation and distribution, promotion of NNC, and food preparation courses [Citation27,Citation29,Citation30,Citation34,Citation49].

Subsidy model and retailer/supplier competition

Critiques of NNC’s subsidy model note that the subsidy model’s reliance on retailers and suppliers – who often operate with limited competition – conflict with the program’s goal of affordability [Citation34,Citation39,Citation46,Citation48,Citation51,Citation60]. Additionally, several critiques questioned the extent to which retailers pass on the subsidy to consumers, whether prices should be regulated, and lack of retailer accountability [Citation16,Citation39,Citation40,Citation45,Citation53,Citation61]. One critique also stated that the process for retailers to register with NNC can be time-consuming [Citation55]. Finally, the weight-based system incentivises suppliers to make heavier items more available than highly perishable items [Citation60].

A number of recommendations provide possible solutions to issues with the subsidy model and retailer/supplier competition. Some recommendations focus on retailer improvement and supplier compliance. For example, NNC can ensure that retailers provide indication that the subsidy is being applied at the point of sale [Citation27,Citation30,Citation57,Citation62]. Others suggest that NNC collect and clarify with retailers the information needed to determine whether the subsidy is being passed onto consumers and make all compliance evaluations of all retailers and suppliers available to the public [Citation29,Citation39,Citation40].

Additional recommendations were identified to improve or revise the subsidy. These include alternative models to address the lack of retail competition, such as adjusting subsidy rates to the number of retailers in a community, establishing community co-operatives, or supporting band-owned stores [Citation16,Citation30,Citation31,Citation49,Citation51,Citation57]. NNC could also reduce administrative burdens for retailers to attract smaller retailers into the program [Citation30,Citation57]. Retailer improvements such as supporting food demonstrations in stores and nutritional education, training for retailers to improve product ordering, and increasing storage capacity to alleviate underlying issues faced by retailers [Citation29,Citation30,Citation39,Citation54].

Cost and quality of food

Critiques under this theme focus on NNC program’s inability to reduce the overall cost of food and the poor quality of shipped foods. For example, these critiques mentioned that NNC does not provide enough of a subsidy since the cost of food remains high [Citation31,Citation43,Citation46,Citation52,Citation58,Citation61,Citation63]. Some also note that NNC has not improved the quality of shipped food [Citation43,Citation64].

Recommendations to address the cost and quality of food include increased regulation and monitoring of the quality and storage of food and additional program assessment to address its emphasis on “fresh” foods, since some foods may be too perishable to be transported [Citation30,Citation39,Citation49]. Other recommendations propose increasing the program budget by indexing it to inflation, or through monitoring population growth, and regulating food prices [Citation29,Citation30,Citation35,Citation39,Citation49,Citation57,Citation59,Citation65]. For example, NNC can institute a price cap on food items, or explore food price regulations such as fixed pricing, target costs, and other cost containment strategies to increase affordability [Citation30,Citation36,Citation39,Citation54,Citation59].

Barriers to equitable food distribution

Barriers to equitable food distribution emphasises how the subsidy model exacerbates ongoing issues of poverty and income inequality, making food less accessible for marginalised individuals and households. Critiques noted that the subsidy disproportionately benefited affluent households since high- and low-income households end up paying the same price on the high cost of food [Citation16,Citation33,Citation34,Citation37,Citation42,Citation52,Citation54]. Others also observed that the personal orders portion of the subsidy model is inaccessible for low-income families without access to a credit card, internet, or financial institution [Citation34,Citation39,Citation45–47,Citation57].

Recommendations were proposed to address the social inequities exacerbated by NNC’s subsidy model. For example, NNC could explore evidence-based poverty reductions measures and other similar approaches to increase the affordability of foods among low-income families [Citation29,Citation34,Citation37,Citation45,Citation47–49,Citation57,Citation65]. Other recommendations advocate for basic income and other similar social assistance programs to address issues related to cost of living or to link NNC to existing income support programs [Citation30,Citation31,Citation51,Citation59]. Changes to how subsidy rates are applied have also been suggested such as adjusting rates according to income levels, food preferences, measures of isolation, or comparable subsidy rates within similar regions [Citation30,Citation35]. Finally, increased access to health promotion activities among all vulnerable communities [Citation49].

Eligibility criteria

Critiques that highlight issues with NNC’s eligibility criteria are grouped into three categories. First, NNC’s inconsistent and unclear community eligibility criteria [Citation38,Citation40,Citation44]. Second, NNC’s recipient eligibility (i.e. types of businesses that can apply such as retailers, suppliers, distributors), leading to risks that possible recipients of the subsidy are improperly excluded [Citation36]. Third, non-food items such as household items and hygiene products that were previously available under the food mail program were removed from the list of eligible items [Citation40,Citation44,Citation57].

Recommendations identified proposed improvements to address eligibility issues. These recommendations were organised into four groups: Transportation rates, items, community, and retailers.

Recommendations for subsidy rates and transportation suggest modifications to how subsidy rates are applied by mode of transportation, for example, transport via sealift, commercial flights, land transportation, or community-based freights [Citation30,Citation39,Citation49,Citation57,Citation59]. Further suggestions include subsidising inter-community trade for meat and fish, and additional support for transportation companies such as reducing or eliminating fees associated with air carrier costs [Citation30].

Recommendations to address issues with item eligibility include reinstating non-food items such as basic hygiene products, infant products, household cleaning products, and hunting and harvesting products [Citation29,Citation30,Citation37,Citation39,Citation50,Citation51,Citation54,Citation57,Citation61,Citation62]. Furthermore, other recommendations suggest that NNC subsidise dried or non-perishable options in all food groups, cooking oils, and flour [Citation27,Citation54,Citation57,Citation61]. Recommendations such as eliminating the subsidy levels, subsidising food stored in community freezers, subsidising in-season food, or providing a greater subsidy on seasonal products to increase program impact were also suggested [Citation27,Citation54,Citation57,Citation61].

Recommendations to address issues related to community eligibility such as including communities that experience high rates of food insecurity were suggested [Citation28,Citation31,Citation37,Citation40,Citation44,Citation54,Citation59,Citation65,Citation66]. Yearly adjustments to subsidies by community, and subsidising based on community size were also identified [Citation30]. Finally, NNC can implement the full subsidy among communities that receive partial subsidies [Citation54].

Lastly, recommendations were advised to change the subsidy eligibility among retailers such as providing the subsidy to multiple stores per community where possible, and that NNC collaborate with retailers to determine item eligibility based on purchasing patterns [Citation29,Citation37].

Cultural food preferences and dietary habits

Cultural food and dietary preferences calls attention to the lack of opportunities for communities to provide direct input for eligible items and funding allocation. These critiques noted that the model does not account for food sharing networks, which better accurately reflects sociocultural community dynamics among Indigenous communities [Citation46,Citation52,Citation60]. Furthermore, several critiques mentioned that communities were not consulted to determine item eligibility and therefore do not reflect the dietary habits and preferences of eligible communities [Citation37–39,Citation43,Citation57,Citation63].

Recommendations identified urge NNC to support the diverse cultural food preferences and dietary habits among eligible communities. For example, NNC could integrate a system that supports food sharing [Citation30,Citation52,Citation62]. NNC could also improve its research data to include cultural determinants of food security and increase support for Inuit-specific nutritional knowledge and literacy via educational opportunities [Citation44,Citation47].

Finally, several recommendations proposed that NNC increase opportunities for community input and collaboration. These recommendations include community collaboration to review and revise the list of eligible items, collaboration with researchers and Indigenous organisations to revise program delivery, and inclusive representation on NNC’s advisory and administrative team [Citation30,Citation34,Citation37–39,Citation57,Citation59].

Support for hunting, harvesting, and community-food initiatives

Critiques identified NNC’s lack of support for hunting, harvesting, or community-based food initiatives. These critiques show that that NNC does not support local food production, regional food systems in the north, and neglects the importance and role of traditional food among Indigenous communities for food sharing [Citation39,Citation47,Citation51,Citation52,Citation55,Citation60,Citation62,Citation67].

Lastly, critiques emphasised the shortcomings of the ways in which commercial food is regulated and processed. For example, CIRNAC highlighted how food processing facilities in the north are constrained by the Canadian Food Inspection Agency’s eligibility requirements [Citation34].

A number of recommendations urge NNC to support hunting, harvesting, and community-based food initiatives. Some propose that NNC fund and support hunters through subsidising necessary equipment, Hunters and Trappers Organizations (HTO), and food preparation courses for traditional foods [Citation30,Citation39,Citation46,Citation51,Citation53,Citation55,Citation59,Citation61,Citation63]. In addition, recommendations advocate for infrastructure supports such as community freezers, gardens, warehouses, and processing plants, which will increase local access to traditional foods [Citation27,Citation30,Citation37,Citation39,Citation45,Citation47,Citation49,Citation51,Citation55,Citation60–62].

Other recommendations suggest improvements to support food sharing networks. These recommendations include subsidies to ship traditional food to communities and relatives, increased distribution networks within and across regions, and alternative food delivery options [Citation30,Citation34,Citation42,Citation55]. NNC could also create incentives to purchase traditional foods such as hosting marketplaces and inter-community trade [Citation30].

Finally, policy and structural changes were identified to support community-based initiatives. Such recommendations call for NNC to explore community-driven initiatives that are more sustainable and less reliant on a corporate food distribution model to inevitably phase out subsidies [Citation31,Citation42,Citation44,Citation51,Citation61]. Other recommendations include school food programs, food banks, or alternative policy structures such as the “Greenland model”, or harvester support programs [Citation29,Citation37,Citation44,Citation47,Citation61].

Discussion

The aim of this scoping review was to summarise and interpret the available evidence on the NNC program in terms of program evaluation data, critiques of the program, and recommendations for improvement. This scoping review was undertaken to inform decision-makers in future efforts to improve the NNC program. The review highlights inadequate evaluation data, several key themes of concern with the program, and subsequent recommendations for improvement.

Critiques of the subsidy model, accountability, and transparency were the most commonly identified areas of concern. These themes highlight problems with the subsidy model, lack of clear objectives, and ability to communicate its effectiveness. For example, there was a substantial lack of evidence on the overall impact of NNC, particularly measured against household food security. St-Germain et al. found that household food insecurity increased after the introduction of NNC, despite Naylor et al.’s findings that most, if not all, subsidies were passed on to consumers [Citation33,Citation35]. These findings indicate that the retail subsidy alone may not be enough to address the underlying causes of food insecurity among eligible communities. However, such findings are limited to available data, especially among people living on reserves or Indigenous settlements that may be excluded from population-based surveys. St-Germain’s study for example only included the largest communities in Nunavut eligible for NNC, thus more data is needed to examine NNC’s effect on food security among eligible communities that are smaller and remote and those in the provincial north [Citation33] Additionally, the results of evaluations using site visits and community engagement also found mixed results of the NNC program. Though NNC has increased the amount of food items to eligible communities, recipients still experience high costs, a lack of support for locally produced food, and confusion about how the subsidy works [Citation27,Citation29,Citation30,Citation32,Citation34]. While NNC reports standardised measures such as weight of food shipped and overall cost reduction, reports of inequitable food distribution have made it unclear if NNC is achieving its desired outcomes [Citation16,Citation34]. More robust data is thus needed to evaluate NNC’s effect on food security, food costs (in addition to cost reduction) and food distribution, particularly among remote communities that are not reflected in population-based surveys. Access to this data would provide insight to subsidy allocation and its effects on food outcomes. This research has thematically synthesised the results, criticisms, and recommendations for the NNC program. However, it is important to provide an overview and contextualisation of the changes to the NNC program that have been put in place in response to many of these criticisms and recommendations. This will help inform the identification of areas where work is still needed to inform policy.

In response to critiques, NNC introduced several changes to the program, which are outlined below(). First, NNC created the Northern Audit Committee in 2019 to improve program transparency and ensure that the program is audited by community members. All audits and action plans are made available to the public via the NNC website [Citation68].

Table 3. Timeline overview of changes made to the NNC program (2011–2022).

Second, NNC revised its mandate, in collaboration with communities, from northern economic development to include food security in 2021. This allows NNC to explore and fund alternative strategies or initiatives to support sustainable, local food production at the community level beyond the retail subsidy [Citation4,Citation69]. Since NNC serves 123 communities as of 2023, the extent to which it can respond to community-specific needs is unclear. A review of programs to address food security for First Nations people in Australia, Aotearoa/New Zealand, Canada, and the United States of America, noted that effective programming involved community-based participatory design, community governance, and cultural knowledge among other key features [Citation70]. Modifications that value community-based programming and culturally appropriate knowledge could help attend to the diverse needs and increase uptake among eligible communities [Citation71].

Third, NNC announced the Food Security Research Grant to support Indigenous-led research projects that address food security and access among eligible communities (). Introduced in 2022, this grant is intended to support the collection of socioeconomic data, food security, or gender-based plus analysis (an equity-based framework) of the NNC retail subsidy. Projects must be directed by Indigenous stakeholders or in collaboration between academics and Indigenous communities [Citation72]. The introduction of the grant reflects recommendations to increase available data to better understand the reach and efficacy of the program, especially when considering the importance of traditional food challenges of scale at which to monitor the prevalence of food security [Citation4]. Overall, these changes reflect recommendations to increase the accountability and scope of the program.

Another common critique is barriers to equitable food distribution. This critique highlights issues of equity and underlying poverty that exacerbate food insecurity among remote, and isolated communities in the north. NNC has introduced a few changes that may address these issues. In 2018, 37 communities were added for full-time eligibility, mostly from northern provinces. Full-time eligibility refers to communities that only received the subsidy when surface transportation became unavailable. These changes reflect recommendations to clarify community eligibility and include communities that were eligible for the subsidy, but were either not receiving it or were seasonally eligible [Citation44].

In 2020, NNC introduced a few changes to the program to support local food systems, reduce food costs, and increase item eligibility. For example, NNC partnered with Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami (ITK), a national organisation that represents the Inuit across the Inuit Nunangat and the Inuit Food Security Working group, developed the Harvesters Support Grant which aims to improve access to traditional foods through reducing the cost of hunting, harvesting, and food sharing in isolated communities [Citation73]. In 2022, NNC also made additions to the Harvesters Support Grant via the Community Food Program, which aim to support community-led food initiatives [Citation73]. The Community Food Program enables recipient organisations to decide how best to support their own communities such as through local food programs (community kitchens or school food programs), food-related infrastructure, or buying clubs. According to NNC, the Harvesters Support Grant and the Community Food Program reduces reliance on store-bought food, encourages traditional harvesting culture and practice, and supports local food production and food sharing [Citation73]. These changes reflect recommendations to diversify the scope and distribution of NNC funding by supporting food-related infrastructure and food sharing.

Furthermore, in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, NNC increased subsidy rates among products with a high and medium subsidy and added non-food items such as cleaning and hygiene products in 2020 [Citation74]. Surface transportation for staple items such as flour were also added to the list of subsidised items. These changes reflect recommendations urging NNC to re-introduce non-food items to the subsidy and to ease the high costs of food items among eligible communities.

Lastly, NNC has added three new categories of recipients to receive the retail subsidy on eligible items in order to strengthen distribution networks and support local economies [Citation75]. The first new category is food banks and charitable organisations who operate without profit. The second category provides subsidies for local food growers that operate greenhouses or other growing facilities who produce food for local sale or distribution. Finally, small, locally owned retailers were added as a category recipient. These changes reflect recommendations to address the lack of retailer competition and reliance on store-bought foods, target vulnerable and marginalised populations that are disproportionately affected by poverty, support smaller retailers and local growers that did not previously have access to the subsidy.

There are a number of priority areas where further research and action in addressing the critiques and recommendations of the NNC program could inform future policy decisions. Additional support for education initiatives such as food preparation courses for store-bought and traditional foods, budgeting, and health promotion are among a few areas that would improve social programming and transparency [Citation27,Citation29,Citation30,Citation34,Citation49]. NNC can continue improve public knowledge of the program and address criticism around communication via outreach programs to mitigate potential confusion regarding changes to eligibility criteria, new programs and grants, or education initiatives [Citation28–30,Citation34,Citation39,Citation59]. A paper published after this review was conducted investigated the implementation of an NNC funded education initiative – a cooking circle (food preparation) program – in a remote community in the Inuvialuit Settlement Region of the Northwest Territories [Citation76]. Findings indicated that the long-standing sustainability of the cooking circle program in the community was related to the consistency of program funding, engaging facilitation practices, and creative use of a multi-purpose space for program activities. The barriers described as limiting program sustainability were funding amounts and funding distribution, space and equipment limitations, and human resources challenges [Citation72]. Food price regulations (i.e. target costs, cost containment strategies) were also identified to address the high cost of food, which continues to be a barrier to equitable food distribution [Citation39,Citation47,Citation54]. Improvements to the quality and freshness of food are also an area in which food spoilage, waste, and lower quality shipped items are barriers to availability and diet variety [Citation30,Citation39]. Changes to transportation costs were also an area for improvement that would improve accessibility such as subsidising transportation costs to support inter-community trading of traditional food, items shipped by sealift, and exploring the impact of climate change on future subsidy levels [Citation30,Citation39,Citation45,Citation57,Citation59]. Finally, though beyond the scope of the program, a number of recommendations identified advocacy for social programming to address the underlying causes of food insecurity in remote and isolated communities such as exploring income support programs, decreasing administrative burdens for retailers, and implementing measures to ensure affordable and accessible food among vulnerable populations [Citation30,Citation37,Citation45,Citation47,Citation48,Citation51,Citation56,Citation57,Citation59,Citation65].

The results of this review are critical, particularly given that total food insecurity in Canada has increased among households that are more vulnerable during the COVID-19 pandemic [Citation77]. Additionally, the impacts of climate change on northern food systems continue to worsen, illustrating the fragility of such food systems [Citation78]. Coupled with the rising cost of food and shelter costs, the existing vulnerabilities of northern food systems are important factors to address food insecurity [Citation79,Citation80].

Study limitations

First, a limitation of this review is the scoping methodology itself, which uses Western methods of screening, sorting, and summarising knowledge. This may be antithetical to Indigenous ways of knowing [Citation81]. Since available literature and evidence are limited to published and/or written accounts, inclusion of oral histories, lived experiences, and other perspectives would provide a more comprehensive picture of NNC’s impact on food security. Second, given that food security among NNC-eligible communities may be idiosyncratic and complex, Western-derived conceptualisations of food security may not accurately assess dietary habits and cultural preferences of eligible communities. Future researchers could develop a community-led framework to measure food security that accurately reflects Indigenous experiences [Citation44,Citation47]. Third, evidence on the impact of NNC are limited and thus may not accurately capture the wide range of complex experiences among eligible communities. It is important to acknowledge that eligible communities not included in this review may face unique circumstances and barriers and may therefore be less comparable to those included in this review. Lastly, since scoping reviews do not appraise the quality of evidence, the certainty in the recommendations summarised cannot be presented [Citation82]. Therefore, bias in the critiques and recommendations identified may also be translated into biases in the results of this review.

Conclusion and implications

This scoping review highlights substantial gaps in knowledge and limitations of available data on the effectiveness of NNC to reduce food insecurity, the importance of traditional food, and the limitations of a retail-subsidy to support the diet and cultural preferences among NNC-eligible communities. In the context of the rising cost of food and shelter in Canada, this scoping review calls attention to the shortcomings of NNC to address household food insecurity in remote and isolated communities. The collection and synthesis of available evidence yields a comprehensive overview of program impact, strengths, and shortcomings. Recommendations to address critiques identified in this review have been synthesised here and are available as supplementary material. These recommendations range from macro-level, structural policy changes to modify NNC’s core objectives, to re-allocating funding to support local food production, traditional food, and food sharing. Though changes to the program aim to address food security, it remains to be seen how these changes affect food outcomes without addressing the need for more robust, comparable data. Barriers to equitable food distribution that stem from broader systemic issues such as poverty and infrastructure (i.e. distribution centres, storage, transportation costs) also need to be considered as these factors are inextricably linked to household food insecurity. The findings of this review highlight a multi-level approach to improve food security among NNC-eligible communities.

Supplementary 1.xlsx

Download MS Excel (96.5 KB)GraphicalAbstract1.png

Download PNG Image (455.6 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/22423982.2024.2313255

Notes

1 These estimates do not include data from on-reserve populations and therefore likely represent an underestimate of true prevalence.

2 Remote communities are more than 350 km away from the nearest service centre with year round road access, whereas special access communities have no year-round road access to a service centre.

3 At the time still referred to as Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada, but here referred to with its current name for ease of understanding.

References

- EC-FAO. Food Security Programme: Agriculture and Economic Development Analysis Division. . An introduction to the basic concepts of food security: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. 2008.

- Tarasuk V, Mitchell, A. Household food insecurity in Canada, 2017–18. Toronto: research to identify policy options to reduce food insecurity (PROOF). 2020. Retrieved from: https://proof.utoronto.ca/

- Chan L, Batal M, Sadik T, et al. FNFNES first nations food, nutrition & environment study: final report for eight assembly of first nations regions. University of Ottawa, Université de Montréal: Assembly of First Nations; 2019.

- Naylor AW, Kenny TA, Beale D, et al. Proceedings from ArcticNet workshop: Moving from understanding to action on food security in Inuit Nunangat. Victoria, British Columbia: University of Victoria; 2023.

- First Nations Information Governance Centre. The First Nations Regional Health survey phase 3: volume two. Ottawa; July 2018.

- Power EM. Conceptualizing food security for aboriginal people in Canada. Can J Public Health. 2008;99(2):95–16. doi: 10.1007/BF03405452

- Blanchet C, Dewailly E, Ayotte P, et al. Contribution of selected traditional and market foods to the diet of nunavik inuit women. Can J Diet Pract Res. 2000;61(2):50–9.

- Lambden J, Receveur O, Marshall J, et al. Traditional and market food access in Arctic Canada is affected by economic factors. International Journal Of Circumpolar Health. 2006;65(4):331–40. doi: 10.3402/ijch.v65i4.18117

- Kuhnlein HV, Chan HM. Environment and contaminants in traditional food systems of northern indigenous peoples. Annu Rev Nutr. 2000;20(1):595–626. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nutr.20.1.595

- Wittman H. Food sovereignty: a new rights framework for food and nature? Environ Soc. 2011;2(1):87–105.

- Richmond C, Kerr RB, Neufeld H, et al. Supporting food security for indigenous families through the restoration of indigenous foodways. Canadian Geographies/Géographies canadiennes. 2021;65(1):97–109. doi: 10.1111/cag.12677

- Council-Alaska IC Alaskan inuit food security conceptual framework: how to assess the Arctic from an inuit Perspective. Technical Report. Anchorage, Alaska; 2015.

- Delormier T, Marquis K. Building healthy community relationships through food security and food sovereignty. Curr Dev Nutr. 2019;3:25–31. doi: 10.1093/cdn/nzy088

- Morrison D. Indigenous food sovereignty: a Model for social learning. In: Wittman H, Desmarais A, and Wiebe N, editors Food sovereignty in Canada: creating just and sustainable food systems. Canada: Fernwood Publishing; 2011. p. 97–113.

- Crown-indigenous relations and Northern Affairs Canada. Nutrition North Canada 2020 [21-]. Available from: http://www.nutritionnorthcanada.gc.ca/.

- Galloway T. Canada’s northern food subsidy Nutrition North Canada: a comprehensive program evaluation. Int J Circump Health. 2017;76(1):1279451–. doi: 10.1080/22423982.2017.1279451

- Nutrition North Canada. Eligible food and non-food items 2020. Available from: https://www.nutritionnorthcanada.gc.ca/eng/1415548276694/1415548329309.

- Nutrition North Canada. How nutrition north Canada works 2022. Available from: https://www.nutritionnorthcanada.gc.ca/eng/1415538638170/1415538670874.

- Peters MDJ, Godfrey CM, Khalil H, et al. Guidance for conducting systematic scoping reviews. Int J Evid Based Healthc. 2015;13(3):141–6. doi: 10.1097/XEB.0000000000000050

- Benzies KM, Premji S, Hayden KA, et al. State-of-the-evidence reviews: advantages and challenges of including grey literature. Worldviews Evid Based Nurs. 2006;3(2):55–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-6787.2006.00051.x

- DistillerSR. Version 2.35. Evidence partners. DistillerSR Inc; 2023. Accessed from: https://www.distillersr.com/.

- Peters MDJ, Marnie C, Tricco AC, et al. Updated methodological guidance for the conduct of scoping reviews. JBI Evid Synth. 2020;18(10):2119–26. doi: 10.11124/JBIES-20-00167

- Peters MDJ, Godfrey C, McInerney P, et al. Chapter 11: scoping reviews (2020 version). In: Aromataris E M Z, editors JBI manual for evidence synthesis. JBI; 2020.

- McArthur A, Klugarova J, Yan H, et al. Systematic reviews of text and opinion. In: Aromataris E, Munn Z, Editors. JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis. JBI; 2020.

- Harfield SG, Davy C, McArthur A, et al. Characteristics of indigenous primary health care service delivery models: a systematic scoping review. Global Health. 2018;14(1):12. doi: 10.1186/s12992-018-0332-2

- Davy C, Harfield S, McArthur A, et al. Access to primary health care services for indigenous peoples: a framework synthesis. Int J Equity Health. 2016;15(1):163. doi: 10.1186/s12939-016-0450-5

- Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada. First report of the Advisory Board. 2012.

- Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada. Implementation Evaluation of the Nutrition North Canada Program. 2013. Available from: https://www.rcaanc-cirnac.gc.ca/eng/1395347953550/1538053744456.

- ENRG research group. Northern Food Retail Data Collection & Analysis by Enrg research group. 2015. Report No.: 1415647437.

- Interis | BDO. Nutrition north Canada engagement 2016: final report of what we heard. 2016.

- Veeraraghavan G, Burnett K, Skinner K, et al. Paying for nutrition: a report on food costing in the north. Food Secure Canada. 2016; September 2016.

- Duhaime G, Caron A, Levesque S, et al. Le Nouveau Régime: Épisode de la Mise en Oeuvre de Nutrition Nord Canada au Nunavik, 2011–2013. Revue Canadienne de Politique Sociale. 2018;78:52–80.

- St-Germain AAF, Galloway T, Tarasuk V. Food insecurity in Nunavut following the introduction of nutrition North Canada. CMAJ. 2019;191(20):E552–E8. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.181617

- Crown-indigenous relations and Northern Affairs Canada. Horizontal Evaluation Of Nutrition North Canada. 2020. Available from: https://www.rcaanc-cirnac.gc.ca/eng/1583415755307/1583415776936.

- Naylor J, Deaton BJ, Ker A. Assessing the effect of food retail subsidies on the price of food in remote indigenous communities in Canada. Food Policy. 2020;93:101889–. doi: 10.1016/j.foodpol.2020.101889

- Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada. Aboriginal affairs and Northern Development Canada internal audit report: audit of the management control framework for grants and contributions 2012–2013. 2013.

- Bratina B Food security in northern and isolated communities: ensuring equitable access to adequate and healthy food for all: report of the Standing Committee on Indigenous and northern Affairs. House of Commons; 2021.

- De Schutter O Interim report of the special rapporteur on the right to food. 2012.

- Inuit Food Security Working Group. Nutrition North Canada Program Engagement. 2016. Available from: https://www.itk.ca/nutrition-north-canada-program-engagement/.

- Office of the Auditor General of Canada. Report of the Auditor General of Canada - Nutrition North Canada. 2014. Available from: https://publications.gc.ca/collections/collection_2015/bvg-oag/FA1-2014-2-6-eng.pdf.

- Office of the Auditor General of Canada. Reports of the Auditor General of Canada to the Parliament of Canada: report 12 protecting Canada’s food system. 2021. Report No.: 9780660409214.

- Stecyk K. Good governance of food security in Nunavut. Journal Of Food Research. 2018;7(4):7–22. doi: 10.5539/jfr.v7n4p7

- Burnett K, Skinner K, LeBlanc J. From Food Mail to Nutrition North Canada: reconsidering federal food subsidy programs for northern Ontario. Canadian Food Studies/La Revue canadienne des études sur l’alimentation. 2015;2(1):141–156. doi: 10.15353/cfs-rcea.v2i1.62

- Dillabough H Food for thought: access to food in Canada’s remote north. 2016. Report No.: 9781988472676.

- Human Rights Watch. Standing Committee on Indigenous and Northern Affairs Briefing on food security in Northern communities. 2021. Available from: https://www.ourcommons.ca/Content/Committee/432/INAN/Brief/BR11271770/br-external/HumanRightsWatch-e.pdf.

- Stephenson ES. Akaqsarnatik: food, power, and policy in Arctic Canada. McGill University; 2020.

- Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami. Inuit Nunangat Food Security Strategy. Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami; 2021. Report No.: 9781989179604.

- Finnigan P A food policy for Canada: report of the Standing Committee on Agriculture and agri-food. 2017.

- Dietitians of Canada. Recommendations of dietitians of Canada for Nutrition North Canada. Dietitians of Canada; 2016. Available from: https://web.archive.org/web/20180412134458/https://www.dietitians.ca/Downloads/Public/DC-response-to-NNC-consultation-November-2016-(1).aspx.

- Food Secure Canada. The right to food: northern Canada Affordable Accessible food in Northern Canada. 2016.

- National Indigenous Economic Development Board. Recommendations on northern sustainable food systems. 2019. Available from: http://www.naedb-cndea.com/reports/NORTHERN_SUSTAINABLE_FOOD_SYSTEMS_RECOMMENDATIONS%20REPORT.pdf.

- Daborn M. Food (In)security: food policy and vulnerability in Kugaaruk. Nunavut: University of Alberta Libraries; 2017.

- Pegg S. Food Banks Canada. Is Nutrition North Canada On Shifting Ground? 2016.

- Pegg S. Food Banks Canada. What will it take to make real progress on northern Food security? 2016. Available from: https://foodbankscanada.ca/northern-food-security/.

- Wilson A, Levkoe CZ, Andrée P, et al. Strengthening sustainable northern food systems: federal policy constraints and potential opportunities. Arctic. 2020;73(3):292–311. doi: 10.14430/arctic70869

- Galloway T. Is the Nutrition North Canada retail subsidy program meeting the goal of making nutritious and perishable food more accessible and affordable in the North? Can J Public Health = Revue Canadienne de Sante Publique. 2014;105(5):e395–7. doi: 10.17269/cjph.105.4624

- Niqqittiavak Committee. The Nutrition North Canada Program. 2015. Available from: https://www.nunavutfoodsecurity.ca/sites/default/files/files/Resources/TheNutritionNorthCanadaProgram_March2015_EN.pdf.

- Pegg S, Stapleton D, Food Banks Canada. Hunger Count 2016: a comprehensive report on hunger and food bank use in Canada, and recommendations for change. 2016.

- Food Banks Canada. Hungercount: a comprehensive report on hunger and food bank use in Canada, and recommendations for change. 2015.

- Food Secure Canada. Recommendations of Food Secure Canada on Nutrition North Canada. Food Secure Canada. 2016. Available from: https://foodsecurecanada.org/sites/foodsecurecanada.org/files/recommendations_nutrition_north_canada.pdf.

- Stephenson E, Wenzel G. Food politics: finding a place for country food in Canada’s northern food policy. North Public Affairs. 2017;49–51.

- Food Secure Canada. Affordable food in the north. 2019. Available from: https://www.eatthinkvote.ca/sites/www.eatthinkvote.ca/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/Affordable-Food-in-the-North-EN-Revised-Aug-30-.pdf.

- Horlick S The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on food security and food sovereignty in Nunavut communities 2021.

- Burnett K, Skinner K, Hay T, et al. Retail food environments, shopping experiences, First Nations and the provincial norths. Health Promotion Chronic Dis Prev Canada. 2017;37(10):333–41. doi: 10.24095/hpcdp.37.10.03

- Dietitians of Canada. Les diététistes du Canada Présentation au Comité permanent des finances de la Chambre des communes Recommandations prébudgétaires 2017. 2016. Available from: https://www.ourcommons.ca/Content/Committee/421/FINA/Brief/BR8126070/br-external/DietitiansOfCanada-f%209303204.pdf.

- Christopherson D. Chapter 6, Nutrition North Canada — Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada, of the Fall 2014 Report of the Auditor General of Canada: Report of the Standing Committee on Public Accounts. 2015.

- Food Banks Canada. 2021 federal policy recommendations. 2021.

- Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada. Government of Canada announces additional changes to Nutrition North Canada government of Canada2019. [cited 2019 8 22]. Available from: https://www.canada.ca/en/crown-indigenous-relations-northern-affairs/news/2019/08/government-of-canada-announces-additional-changes-to-nutrition-north-canada.html.

- Minister Vandal announces enhancements to food security programs in isolated northern communities, promoting local food sovereignty [press release]. Government of Canada; 2022. Available from: https://www.canada.ca/en/crown-indigenous-relations-northern-affairs/news/2022/08/minister-vandal-announces-enhancements-to-food-security-programs-in-isolated-northern-communities-promoting-local-food-sovereignty.html

- Davies A, Gwynn J, Allman-Farinelli M, et al. Programs addressing food security for first nations peoples: a scoping review. Nutrients. 2023;15(14):3127. doi: 10.3390/nu15143127

- Ramirez Prieto M, Sallans A, Ostertag S, et al. Food programs in Indigenous communities within northern Canada: a scoping review. Canadian Geographies/Géographies canadiennes. 2023. doi: 10.1111/cag.12872

- Nutrition North Canada. Food security research grant 2022. Available from: https://www.nutritionnorthcanada.gc.ca/eng/1659529347875/1659529387998.

- Nutrition North Canada. Support for hunting, harvesting and community-led food programs 2022. Available from: https://www.nutritionnorthcanada.gc.ca/eng/1586274027728/1586274048849.

- Nutrition North Canada. Enhancements to the Nutrition North Canada subsidy program during COVID-19 2020. [cited 2020 09 04]. Available from: https://www.nutritionnorthcanada.gc.ca/eng/1593803686454/1593803714791.

- Nutrition North Canada. Accessing the retail subsidy: government of Canada. [ cited 2022 08 15]. Available from: https://www.nutritionnorthcanada.gc.ca/eng/1415626422397/1415626591979.

- Dedyukina L, Wolki C, Wolki D, et al. Process evaluation of a cooking circle program in the Arctic: developing the mukluk logic Model and identifying key enablers and barriers for program implementation. Canadian Journal Of Program Evaluation. 2023;38(2):219–42. doi: 10.3138/cjpe-2023-0031

- Idzerda L, Gariépy G, Corrin T, et al. What is known about the prevalence of household food insecurity in Canada during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review. Health Promotion Chronic Dis Prev Canada. 2022;42(5):177–87. doi: 10.24095/hpcdp.42.5.01

- Spring A, Skinner K, Wesche S, et al. Building community-university research partnerships to enhance capacity for climate change and food security action in the NWT. North Public Aff. 2020;6:63–67. Available from: https://www.northernpublicaffairs.ca/index/volume-6-special-issue-3-special-issue-on-hotii-tseeda-working-together-for-good-health/building-community-university-research-partnerships-to-enhance-capacity-for-climate-change-and-food-security-action-in-the-nwt/

- Fradella A. Behind the numbers: what’s causing growth in food prices. Statistics Canada: Statistics Canada; 2022 [November 16, 2022].

- Canada S. Consumer price index. April 2022. May 18 2022. Available from: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/daily-quotidien/220518/dq220518a-eng.htm

- Chandna K, Vine MM, Snelling S, et al. Approaches, and methods for evaluation in indigenous contexts: a grey literature scoping review. Can J Program Eval. 2019;34(1):21–47. doi: 10.3138/cjpe.43050

- Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;8(1):19–32. doi: 10.1080/1364557032000119616