ABSTRACT

Comprehensive evaluation of cancer screening activities based on individual experiences is urgently needed to address the burden of cancer among Métis people. In this co-designed and co-led study, a cancer screening questionnaire developed for Métis people to evaluate their cancer screening histories and to explore barriers and facilitators to cancer screening was used. Adult Métis Albertans were invited to participate in the anonymous survey through a multi-modal strategy used for community consultations. Descriptive analyses compared responses between regions, age groups and geographic locations. In total, 370 participants who identified as Métis consented and contributed responses between 12 September and 2 December 2022. Female respondents reported higher rates of cervical and breast cancer screening (>94%) and lower rates of colorectal cancer screening (67–78%). Most of the barriers and facilitators were rated as very important, especially access to reliable and accurate information on screening, risks and benefits of cancer screening, explanation of the test results or procedures, trust in their health care provider(s) and health care system and access to a primary health care provider. This study fills a crucial gap that can inform targeted interventions to increase cancer screening awareness and rates among Métis Albertans and reduce their cancer burden.

Introduction

Cancer continues to be the leading cause of death in Canada and accounts for 26.6% of all deaths [Citation1]. Cancer screening programmes can detect cancer early at the most treatable stage or precancerous lesions to prevent cancer, contributing to better cancer outcomes and decreased cancer mortality, incidence and morbidity [Citation2]. In Alberta, cancer screening programmes are available for breast, cervical and colorectal cancer through Alberta Health Services (AHS) and are publicly funded under Canada’s Universal Health Care System. Despite the availability of screening programmes, disparities in cancer screening service utilisation and outcomes continue to exist across Canada [Citation3]. Indigenous peoples in Canada experience reduced rates of cancer screening [Citation4] due to barriers such as geography, a lack of awareness of screening guidelines, colonisation, intergenerational trauma, a lack of cultural safety training for health care professionals and racism and discrimination [Citation5]. These barriers can be addressed by leveraging the experiences of Indigenous peoples to inform the development of meaningful interventions that increase access to quality and safe cancer screening services and reduce these disparities.

Métis people are one of the three constitutionally recognised Indigenous peoples of Canada, emerging pre-confederation from the unions between First Nations women and European fur traders. According to the 2016 Canadian Census, 587,545 people self-identified as Métis [Citation6], making up approximately 35% of the Indigenous population in Canada. Métis people have their own unique culture, language and way of life that is distinct from other Indigenous peoples of Canada (First Nations, Inuit). The Otipemisiwak (Those Who Govern Themselves) Métis Government of the Métis Nation within Alberta (MNA) is the governing body for Métis people in Alberta. Comprised of more than 63,000 Citizens, the MNA strives to advocate for and protect Métis peoples’ rights and self-determination. The MNA’s Department of Health provides culturally appropriate health and wellness opportunities that address the unique health profile of Métis Albertans, including cancer prevention. This project was completed before the swearing-in of the Otipemisiwak Métis Government in 2023. It uses the previous MNA Regions Map (1972–2023) to report participant residence (Supplementary Figure S1).

A recent Canada-wide report showed that Métis people experience lower rates of cancer screening compared to the general Canadian population [Citation7]. Additionally, Métis people experience higher cancer incidence and mortality rates; the same study also showed that Métis adults had higher rates of female breast, cervical and lung cancer and higher prostate cancer mortality [Citation7]. The higher incidence and mortality rates coupled with lower rates of cancer screening in the Métis population suggest that these two factors may be related. However, there is a paucity of Métis-specific health research [Citation8], and the limited research that exists reports on pan-Indigenous data, failing to capture the distinct lived experiences and realities of Métis people [Citation4]. It is imperative that health research utilises distinctions-based approaches to account for and contextualise the experiences and perspectives that exist within different Indigenous populations.

Cancer screening has been identified as a priority within the Métis community in Alberta and is a critical priority in the Alberta Métis Cancer Strategy [Citation9]. The Strategy outlines specific actions for the MNA to facilitate improved cancer journey experiences for Métis Albertans. Specifically, the Strategy calls on the MNA to collect Métis-specific data on cancer screening to understand screening behaviours, barriers and facilitators, the utilisation of cancer screening services and cancer screening rates among Métis Albertans [Citation9].

To address these priorities and fill the gap in Métis-specific health research, the MNA, in partnership with Alberta Health Services Screening Programs, sought to investigate cancer screening rates, behaviours and the various barriers to and facilitators of cancer screening for breast, cervical and colorectal cancer among the Métis population in Alberta. A Métis-specific cancer screening questionnaire (previously described in The Journal of Current Oncology) [Citation10] was developed to capture this information. The information gathered from the questionnaire will inform interventions to address barriers to cancer screening that Métis Albertans experience, ultimately improving access to cancer screening programmes and providing opportunities to detect cancer early.

Materials and methods

MNA engagement and research team

Métis researchers and health leaders from the MNA co-designed and co-led this research project, which incorporated Métis perspectives and traditional knowledge. This approach ensured that Métis communities will benefit from this research and the resulting knowledge of their data. The non-Métis members of the research team were trained in and adhered to the ethical principles and practices in alignment with the Tri-Council Policy Statement: 2 (2022) – Chapter 9: Research Involving the First Nations, Inuit and Métis Peoples of Canada; the Principles of Ethical Métis Research; and First Nations principles of ownership, control, access, and possession (OCAP®) in carrying out this research project [Citation11]. Members of the research team had knowledge and research expertise in Métis traditional knowledge, cancer screening, cancer prevention, epidemiology, population health and biostatistics. The project leaders had collaborated on previous projects where trusting and respectful relationships had developed that led to the co-creation of this project. More details on specific contributions by each author are listed in the Author Contributions.

Participant recruitment and eligibility

The survey was targeted to Métis Albertans (MNA Citizens or self-identifying Métis people in Alberta) who were 18 years of age and older. Participants were recruited through a multimodal strategy used by the MNA for community engagement, including advertising the survey on MNA social media platforms (X, formerly known as Twitter, Facebook and Instagram) and biweekly newsletters/Citizen email lists. Active recruitment began on 12 September 2022 and ended on 2 December 2022. Eligibility for each cancer screening programme was based on Alberta’s cancer screening guidelines in 2022. In Alberta, cancer screening guidelines recommended mammograms, Pap smears and Faecal Immunochemical Tests (FIT) or stool tests for people at average risk to be done every 2 years, every 3 years and every 1–2 years, respectively. Guidelines for breast cancer screening eligibility include females and those who were assigned male at birth and have been on feminising therapy for 5+ years in total who are aged 45–74 years. Females and people with a cervix who have ever been sexually active are eligible for cervical cancer screening beginning at age 25 or 3 years after becoming sexually active. Cervical cancer screening continues to age 69 [Citation12,Citation13]. For colorectal cancer screening, eligibility criteria included males or females aged 50–74 years [Citation14]. FIT tests were adopted in 2013 as an entry-level test for colorectal cancer screening; however, colonoscopy continued to be offered to some average risk adults, although this practice is becoming less common. The results for the time since last colorectal cancer screening test are only based on FIT tests as the time since the last colonoscopy is unknown. Based on the option to describe their gender, males could only answer questions about colon cancer screening.

Questionnaire implementation, and data capture/storage

The Métis-specific cancer screening questionnaire that was created in collaboration with the MNA has been previously described [Citation10]. Consent and access to the electronic questionnaire were provided through a link to interested individuals from the MNA Health Research and Advocacy website [Citation15]. The questionnaire was programmed in Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap, v.13.1.37) at the University of Calgary and used for conducting this survey [Citation16,Citation17]. REDCap was selected because participants could easily access the web-based questionnaire, and because of its secure data collection and storage and branching logic options to restrict eligibility for each screening programme [Citation18]. The MNA facilitated telephone completion of the questionnaire in English or in Cree for Métis Albertans who experienced barriers to survey completion related to an ability to read or write English or to access the website. Consent was required prior to being able to answer questions in the Métis-specific cancer-screening questionnaire although all responses were anonymous. The collected data were stored in the secure, REDCap project database at the University of Calgary. Access to anonymous data was limited to two members of the research team who were responsible for the creation and management of the REDCap version of the questionnaire and related data. Ethics approval for this study (HREBA.CC-21-0145) was granted by the Health Research Ethics Board of Alberta – Cancer Committee and was conducted in accordance with the principles stated in the Declaration of Helsinki.

Statistical analysis and interpretation

Descriptive analyses of the survey responses were summarised in tables of the frequencies or counts and/or the percentages for each questionnaire section. Sections included questions on demographics, breast, cervical and colorectal cancer screening programmes, as well as barriers and facilitators to cancer screening. The results for when the last cancer screening test was performed included only participants who had reported having a specific screening test. For a few questions, data from different categories were combined to ensure at least 10 data values were in every category, and if this was not possible, then just the percentages are shown.

A Likert scale plot summarised the responses for the 28 questions on distinct barriers to and facilitators of cancer screening. We carried out a factor analysis to determine if few factors or constructs were underlying these responses on barriers and facilitators to cancer screening. The resulting factors were then labelled based on questions that were grouped through the response patterns. These factors could aid in simplifying our understanding of the underlying reasons driving similar responses among participants. All the analyses were conducted using RStudio v3.5.2 [Citation19] and Stata 17.0 [Citation20] statistical software programmes.

Validity and reliability

Staff from the MNA and Alberta Health Services Screening Programs pilot-tested the questionnaire to ensure face and content validity and to identify any issues with comprehension. Missing values for the barriers and facilitators’ questions were imputed using the MICE package in R (RStudio v3.5.2) [Citation21] to generate a complete data set. Cronbach’s alpha was calculated for the dataset with and without any imputation of missing values to determine the internal consistency or reliability of the barriers and facilitators’ items in the questionnaire.

Interpretation of results

Interpretation of the results was carried out by Métis researchers, including A. Letendre, and by the MNA, R. Bartel, A. James, A. Andrew, and J. Kima. As such, the interpretation of the results incorporated Métis perspectives and traditional knowledge to deepen the understanding of them for Métis population and the rest of the research team. MNA review and approval of the manuscript was received prior to publication.

Results

Comparing summary statistics between the 2021 Canadian Census data for Métis people in Alberta and our survey data, the gender ratio was 94.0 men to 100 women (2021 Census), which is substantially higher than the 16:100 ratio of the survey respondents [Citation22]. However, the age distributions are very similar: the proportion of people aged 25–44 years in the Census data was 48.4% while in the survey data it was 48.4%; for people aged 45–64 years, the proportion based on the Census data was 38.1% while in the survey data it was 40.8%; and for people aged 65 and up the proportion based on the Census data was 13.5% while it was 8.1% for the survey data. Most Métis people lived in Edmonton, and then Calgary based on the 2021 Census, which is similar to our survey data. Thus, the age distribution and geographic locations of respondents were similar to those from the 2021 Canadian Census, making our study population comparable to the Albertan Métis population.

Participant characteristics are presented in . In total, 370 participants who identified as Métis consented and contributed responses to the cancer screening questionnaire between 12 September 2022, and 2 December 2022. Most participants self-described as female at birth (85.1%), were primarily between the ages of 35 and 64 years old (73.8%) and were married or living together (57.0%). Nearly half (44.6%) of the participants had a college or university degree and most of them owned their residence (80.0%). Fewer than a quarter of participants had an income under $49 000 CAD or an income above $100 000 CAD. Most participants were living in Region 4 (47.0%) although all Regions were represented (Supplementary Figure S2). While selected occupation options were diverse, a third of participants worked in a professional job setting (33.2%). Similarly, 41.4% of participants were employed full time while the employment status of the rest varied substantially.

Table 1. Métis participant characteristics (n = 370).

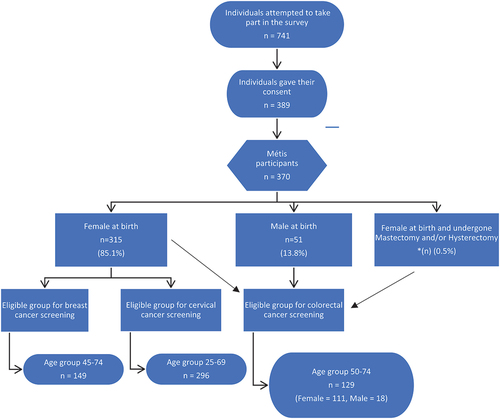

is a flow diagram showing the number of attempts at completing the questionnaire, the number of participants who did consent, the number of people who subsequently self-identified as Métis and the number of people eligible for each cancer screening programme. Many of the attempts were followed very closely in time based on the time stamp with completion of the survey. Although it cannot be verified, participants might have re-attempted to complete the survey after it closed if consent was not given. Overall, 149 and 296 female participants were eligible for breast and cervical cancer screening, respectively, while 111 female participants and 18 male participants were eligible for colorectal cancer screening. Due to the small number of eligible male participants for colorectal cancer screening, only females were included in these analyses and results.

Figure 1. Flow diagram of participant eligibility for cancer screening programs. Reproduced with permission from community report “Nishtohtamihk li kaansyr — understanding cancer: Cancer screening survey report among the Métis population of Alberta” (in production).

presents participation frequencies and/or percentages for breast, cervical and colorectal cancer screening for age-eligible females. Of participants who have had a mammogram (n = 138), 23.9% were aged 45–49 (n = 33) and 76.1% were aged 50–74 (n = 105). Among 315 individuals who were assigned female at birth, for the age group 25–69, there were 296 eligible participants for cervical cancer screening, of which 277 said “yes” to having received this screening. For colorectal cancer screening survey questions, eligible participants included males and females ages 50–74 years old; male participants were removed from the analysis of colorectal cancer screening due to a lack of data. As a result, only age-eligible women (n = 111) were considered of which 77 had a FIT and 54 said they had a colonoscopy test. Overall, there were more than 90.0% participants in both mammogram and Pap smear testing from this survey group. Furthermore, there seems to be high participation within each category when stratifying by municipality and some MNA Regions. The data for Regions 2 and 3 are not presented due to fewer than 10 responses for each. In comparison, 73.3% and 51.4% of eligible responders had a FIT and colonoscopy for colorectal screening, respectively. While colonoscopy had equal amounts of participation in either “City” or “Other” municipalities, there is a 10.7% difference in participation in individuals residing in “Other” municipalities (78.0%) than “City” (67.3%) for FIT or stool tests. It is important to note that colonoscopy tests may have been done for different indications, including for diagnostic follow up after a positive FIT, diagnostic work up after certain symptoms, for surveillance or for screening purposes.

Table 2. Percentage of participation (responded yes) by females in breast, cervical and colorectal cancer screening by municipality and MNA region.

presents the reasons participants received their last cancer screening test if they responded “Yes” to having a screening test. For all cancer screening types, the most frequent reason for having a cancer screening test was because it was part of their regular check-up or routine screening. For mammograms, 41.3% and 40.6% stated their reasons being family history and age, respectively. A doctor’s recommendation (28.9%) was the second most common reason for cervical cancer screening while for FIT or stool test, it was age (32.5%). Family history (20.4%) was the next most common reason for a colonoscopy for participants in this study.

Table 3. Reasons* for the last cancer screening exam in percentages by females for those who responded “yes” to having each type of examination.

For mammograms, more than 80% of the participants in both age groups have had their mammograms performed less than 2 years ago. Pap smears were most likely to have been done 1–3 years ago (45.5%) (). The majority of the FIT tests were done either less than 1 year ago (31.2%) or 1–2 years (32.5%) prior to the survey date. Similar participation percentages were observed for both time intervals since the last screening by municipality and MNA region for all cancer screening types.

Table 4. Time since last cancer screening test was conducted for female participants by age group, municipality and MNA region in percentages.

Among the 54 female participants who ever had a previous colonoscopy, 44.4% (24/54) of participants aged 50–74 years had one colonoscopy in their lifetime, while 55.6% had two or more (data not shown). The percentages for women ever having a colonoscopy were similar regardless of their municipality (51.9% in the city and 50.0% in other areas) but were higher for women living in Region 4 (50.0%) than those living in Regions 1, 5 and 6 combined (39.1%).

The knowledge about vaccination status and attitude towards the HPV vaccine (Gardasil ®) is shown in for those women who had heard about this vaccine. While 87.5% of eligible women have heard about the vaccine, only 13.9% have received it (). However, among those who have not received the vaccine, half of the participants would take the HPV vaccine if they were eligible. Based on the results, there was a 73.6% increase in the receipt of vaccine participation in Region “4” compared to Regions “1, 5 and 6” ().

Table 5. Knowledge of HPV vaccine, vaccination status and attitude by women eligible for cervical cancer screening, in percentages.

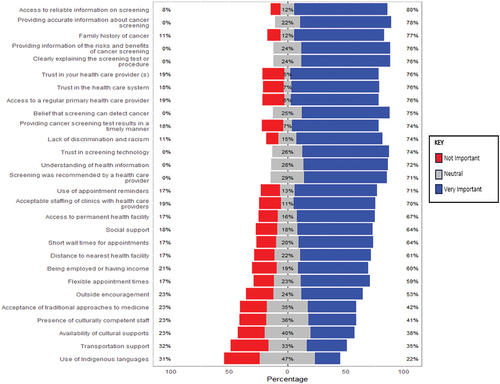

presents the Likert scale plot analysis performed on the barriers and facilitators to cancer screening derived from the corresponding section of the questionnaire. Overall, the majority of the barriers and facilitators listed were considered to be very important (blue bars). Towards the bottom of the Likert scale plot, the importance of the last five questions diminished compared to the previous questions. Based on this analysis, the eight most important factors (Very Important ≥ 76%) included: access to reliable information on screening; providing accurate information about screening; family history of cancer; providing information of the risks and benefits of cancer screening; clearly explaining the test results or procedures; trust in your health care provider(s); trust in the health care system and access to a regular primary health care provider. The least important factors (red bars) included: use of Indigenous languages; transportation support; availability of cultural supports; presence of culturally competent staff and acceptance of traditional approaches to medicine. However, about half of the respondents had neutral feelings (grey bars) on the importance of the use of Indigenous language (47%) and on the availability of cultural supports (40%) ().

Figure 2. Likert plot analysis on barriers and facilitators to cancer screening.

Factor analysis

Based on the factor analysis of the 28 questions in the “Barriers and Facilitators” section, four distinct factors/constructs arose: understanding cancer screening information and trusting in health care providers and system (7 questions about screening information; 9 questions about trusting in health care providers and system, Factor 1); cultural sensitivity and appointment options (6 questions, Factor 2); health care access (2 questions, Factor 3) and socioeconomic factors (4 questions, Factor 4); The mapping of questions to each factor as well as the factor loadings are shown in Supplementary Figure S2, while Supplementary Table S1 shows the questions associated for each construct. The variance explained by each specific factor is presented in Supplementary Table S2. The proportion of variance explained by Factor 1 is the highest at 31.7%, while the cumulative proportion of variance explained for all four factors is 68.4%

The first construct “Understanding cancer and screening information and trusting in health care providers and system” included the most barriers and facilitators at 16 with 8 of these rated with the highest percentages as “Very Important”. Furthermore, 9 of these 16 barriers and facilitators (providing information of the risks and benefits of cancer screening; providing accurate information about screening; clearly explaining the test results or procedures; trust in your health care provider(s); trust in the health care system; trust in screening technology; screening was recommended by a health care provider; understanding of health information and lack of discrimination and racism) have a factor loading at or above 0.7 which means that these barriers or facilitators are highly correlated with this construct. In contrast to Factor 1, the ratings for the six factors comprising Factor 2 (Cultural sensitivity and appointment options) had the lowest percentages for “Very Important”. The factor loadings for four of the six questions were at or above 0.7, so they are strongly related to this construct as were the loadings for the two questions for Factor 3 (Health care access). The four questions loading on Factor 4 (socioeconomic factors) had correlations at or below 0.7, indicating lower correlation.

Reliability

Cronbach’s alpha was first calculated using the original data set (389 observations with missing observations: minimum = 84, median = 117, maximum = 155 numbers of responses) and produced a Cronbach’s alpha test value of 0.951, representing excellent internal consistency of the data (). Subsequently, the MICE package in R (RStudio v3.5.2) was used to generate a complete data set by imputing missing observations. The Cronbach’s alpha for the resulting imputed data set was 0.963, showing excellent internal consistency.

Table 6. Cronbach’s alpha for barriers and facilitators to screening.

Discussion

The survey results indicate that while the majority of eligible Métis Albertans who responded to the questionnaire have undergone breast, cervical and/or colorectal cancer screening, barriers could still exist to meeting the recommended cancer screening guidelines. Approximately one out of five Métis female participants had a mammogram more than 2 years ago and a Pap smear test more than 3 years ago. These results fall outside of the recommended guidelines for breast and cervical cancer screening in Alberta [Citation23,Citation24] which provides an opportunity to develop interventions that increase access to breast and cervical cancer screening programmes, such as providing culturally appropriate information and support. Similarly, the survey results show modest rates of participation for the FIT, with almost one out of three eligible participants having a FIT more than 2 years ago. This suggests that many female Métis Albertans are not accessing Alberta’s routine colorectal cancer screening programme as recommended [Citation25]. In addition, some reasons given for having a FIT, such as “Signs or symptoms of possible problem” and “Follow-up of previous problem” are not appropriate indications for FIT. Collectively, these survey results underscore the need for targeted interventions for the Métis population in Alberta to increase access to appropriate cancer screening and information.

When comparing cancer screening participation, breast and cervical cancer screening did not vary significantly according to participant location. However, there are notable differences between those who live in a city and those who live in a small town, rural or remote area for colorectal cancer screening participation. The survey results show that participants who lived in a small town, rural or remote area were more likely to take a FIT compared to those who lived in the city. This is a unique finding, since people who live in small towns, rural or remote areas generally have less access to cancer screening programmes due to geographical barriers [Citation26]. The survey results also show a high rate of colonoscopies among survey respondents; two-thirds of participants living in MNA Regions 1, 5 and 6 and two-thirds of those who lived in a city had more than one colonoscopy. Further research needs to be completed to investigate this unusually high rate of colonoscopies as these were not generally entry-level tests for average risk adults.

Additionally, the survey results showed that participants who lived in MNA Region 4 or in a city are much more likely to have heard of the HPV vaccine (Gardasil ®), have taken the vaccine and have the willingness to take the vaccine. Consistent with previous findings, this suggests regional disparities in access to health information and services throughout Alberta may exist. It is also important to note that HPV vaccination became publicly available in 2008 through public health vaccine programmes offered at schools with parental consent [Citation27]. Because this programme only began in 2008, the vaccine would not have been accessible to many survey respondents, contributing to lower vaccination rates. However, in Alberta, the HPV vaccine is currently available free of cost to Albertans aged 26 years and younger [Citation28].

The barriers and facilitators identified in this survey are crucial in providing a baseline understanding of the gaps in accessing cancer screening programmes in Alberta. They also offer clear direction on what is needed to promote safety, quality and culturally appropriate cancer screening services. This includes providing access to reliable and accurate information about cancer screening, explaining the risks and benefits of cancer screening and building trust in health care providers, among other factors that influence access to cancer screening services. The results obtained in this survey align with a study conducted by the Métis Nation of Ontario, which found that the top barriers to cancer screening for the Métis population in Ontario included limited access to health care providers, a lack of cultural competency among health care providers and a lack of information regarding cancer screening [Citation29]. There may be an opportunity to leverage the facilitators identified in this survey to inform the development of meaningful and targeted interventions to increase cancer screening rates among Métis Albertans. For example, by developing Métis-specific cancer screening resources to increase awareness, provide reliable and accurate information including the risks and benefits of cancer screening tests and describe the recommended guidelines for cancer screening in Alberta.

There is an urgent need to develop and implement cultural safety training for health care providers to ensure that Métis Albertans accessing cancer screening services feel comfortable and safe and create an environment that fosters trust between Métis Albertans and the health care system. Additionally, the survey revealed that the most common reason for accessing screening programmes was through routine health care. However, Métis Albertans who do not have access to a primary care provider may experience significant barriers in accessing screening services due to a lack of referral to and awareness of available cancer screening programs and information. This underscores the need for concerted efforts to improve access to primary care services in Alberta, consequently facilitating increased access to and participation in cancer screening among Métis Albertans.

Strengths and limitations

The questionnaire used in this study was developed in collaboration with the MNA to ensure relevance to the Métis population in Alberta. Although no Métis-specific questionnaire related to cancer screening existed before the creation of this survey tool, existing survey questions were adapted with MNA input. The MNA also led the survey promotion and recruitment of survey participants. Adherence to the Principles of Ethical Métis Research was prioritised throughout to ensure the study was grounded in the voices and perspectives of Métis Albertans. The development of this Métis-specific cancer screening survey and publication will fill a significant gap in Métis-specific health research, providing an opportunity to develop interventions that increase cancer screening for Métis people. The four underlying constructs of the barriers and facilitators based on the factor analysis provide important information for other researchers who might consider using this questionnaire developed for Métis adults. The high internal consistency of these barriers and facilitator questions is also a strength of this study.

However, some limitations to this study exist. One of the limitations of this study was not having access to medical record data to confirm the self-reported screening visits. As a result, there may be misclassifications and inaccuracies in the true screening completion rates and time since the last screening test was performed. For colorectal cancer screening, the reasons for having a colonoscopy were also unknown, so the results for being up-to-date could be higher if the colonoscopy test was done for screening and not diagnostic purposes. Additionally, since the survey was promoted through the MNA social media platforms and the bi-weekly newsletter, participants who are already signed up to receive updates from these platforms, including those proactive about their health, might be more likely to participate in the survey compared to other Métis Albertans, resulting in potential bias in the sample.

The reported very high cancer screening rates in this study compared to other Indigenous studies might not be a true reflection of cancer screening rates in all Métis people. Other studies used registries and medical databases, while we implemented a survey which, as a result, introduces a limitation on sample size [Citation8]. For example, the most recent study cited in the review by Decker et al. [Citation30] had nearly 60,000 Manitoban First Nations women included in their screening study using six provincial and federal data sources. Our study is additionally limited due to the overall low response rate, especially from participants in MNA Regions 2 and 3, as well as from participants who were self-described as being male at birth. The number of respondents is, however, consistent with previous surveys by the MNA using similar recruitment strategies but still represents about 1–2% of Métis adults who would be eligible for cancer screening programmes. Strategies to increase participation by males in future surveys include an activity that men would normally participate in, such as a guided construction workshop, drum making and a sharing circle with traditional music and dance; inviting couples or families or providing incentives such as gift cards for fishing or harvesting equipment. Hence, the survey results are potentially not representative of all Métis Albertans. Additionally, very few open-ended questions were included in the survey questionnaire, limiting Métis Albertans’ ability to share their cancer screening experiences fully. However, the MNA will build on this research by holding qualitative gatherings with Métis Albertans to share their experiences and perspectives regarding cancer screening. The qualitative data from these gatherings will facilitate a better understanding of the barriers and facilitators described in this report, and inform the development of interventions to improve cancer screening for Métis people in Alberta.

Conclusion

The lack of Métis-specific research related to cancer screening impedes the creation of targeted cancer screening interventions and resources. These survey results provide an initial understanding of Métis peoples’ experiences with cancer screening and are a crucial step towards a better understanding of Métis Albertans’ cancer screening behaviours, as well as barriers and facilitators of cancer screening. Providing equitable access to cancer screening programmes and resources will facilitate early detection, improved treatment outcomes and reduced cancer mortality among Métis Albertans. These study results must be explored further to fully capture the thoughts, experiences, insights and stories of Métis people related to cancer screening. The self-determined priorities of Métis Albertans to improve the health and wellness of the Métis population in Alberta through cancer screening will also be realised.

Author contributions

Conceptualisation, A.L., R.B., H.Y. and K.K.; methodology, A.L., R.B., B.C., A.J., J.K., J.N., B.S., A.A., H.Y. and K.K.; software, C.R. and B.S.; formal analysis, C.R. and K.K.; data curation, C.R., B.S. and K.K.; writing – original draft preparation, A.A., J.K., M.K. and K.K.; writing – review and editing, all authors; visualisation, C.R.; supervision, R.B., A.J., H.Y. and K.K.; project administration, K.K.; funding acquisition, A.L., R.B., H.Y. and K.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Consent to participate

Informed consent was obtained for deidentified survey data to be included in the study.

Supplementary Material June 10-clean.docx

Download MS Word (249.2 KB)Acknowledgments

The project leaders are grateful to the Métis Nation of Alberta staff for their support to this project, Amanda Andrew in particular. From AHS Screening Programs, Monica Schwann (Screening Programs Director) and James Newsome (Program Innovation and Integration Lead) contributed substantially to our project, as did Melissa Potestio from the Department of Community Health Services, University of Calgary. The research team thanks the Métis Albertans, who, by sharing their experiences related to cancer screening, actively participated in the collective effort to improve health outcomes and cancer journey experiences among the Métis community. The project team deeply appreciates all Métis Albertans who participated in this survey.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

Due to the nature of the research, including the adoption of the Principles of Ethical Métis Research and the CARE Principles for Indigenous Data Governance, supporting data are not available.

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/22423982.2024.2368766

Additional information

Funding

References

- Statistics Canada. Increase in mortality from 2020 to 2021 entirely attributable to deaths among males 2023. [cited 2024 Feb 29]. Available from: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/daily-quotidien/230828/dq230828b-eng.htm

- Chaput G, Giudice MED, Kucharski E. Cancer screening in Canada. What’s in, what’s out, what’s coming. Can Family Physician. 2021;67(1):27–13. doi: 10.46747/cfp.670127

- Kerner J, Liu J, Wang K, et al. Canadian cancer screening disparities: a recent historical perspective. Curr Oncol. 2015;22(2):156–163. doi: 10.3747/co.22.2539

- Brock T, Chowdhury MA, Carr T, et al. Métis peoples and cancer: a scoping review of literature, programs, policies and educational material in Canada. Curr Oncol. 2021;28(6):5101–5123. doi: 10.3390/curroncol28060429

- Nguyen NH, Subhan FB, Williams K, et al. Barriers and mitigating strategies to healthcare access in indigenous communities of Canada: a narrative review. Healthcare (Basel). 2020;8(2):112. doi: 10.3390/healthcare8020112

- Government of Canada. Crown-indigenous relations and Northern affairs Canada. Indigenous peoples and communities 2024. [cited 2024 Feb 29]. Available from: https://www.rcaanc-cirnac.gc.ca/eng/1100100013785/1529102490303

- Mazereeuw MV, Withrow DR, Nishri ED, et al. Cancer incidence and survival among Métis adults in Canada: results from the Canadian census follow-up cohort (1992–2009). Can Med Assoc J. 2018;190(11):E320–E6. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.170272

- Hutchinson P, Tobin P, Muirhead A, et al. Closing the gaps in cancer screening with first Nations, inuit, and Métis populations: a narrative literature review. J Indigenous Wellbeing. 2018;3(1):3–17.

- Métis Nation of Alberta. Alberta métis cancer strategy: a plan for action Alberta: métis Nation of Alberta. Dept. of health. 2023. Available from: https://albertametis.com/app/uploads/2023/04/Alberta-Metis-Cancer-Strategy.pdf

- Letendre A, Khan M, Bartel R, et al. Creation of a Métis-specific instrument for cancer screening: a scoping review of cancer-screening programs and instruments. Current Oncol. 2023;30(11):9849–9859. doi: 10.3390/curroncol30110715

- The First Nations Information Governance Centre. The First Nations Principles of OCAP®. 2023 [cited 2024 Feb 29]. Available from: https://fnigc.ca/ocap-training/

- Alberta Health Services. Alberta Cervical Cancer Screening Program. n.d [cited 2024 Feb 29]. Available from: https://www.albertahealthservices.ca/findhealth/service.aspx?Id=1016155

- Alberta Breast Cancer Screening Program. Alberta breast cancer screening | clinical Practice Guideline | 2022 Update 2022. [cited 2024 Feb 29]. Available from: https://screeningforlife.ca/wp-content/uploads/Alberta-Breast-Cancer-Screening-Guideline-2022.pdf

- Alberta Health Services. Alberta Colorectal Cancer Screening Program. n.d [cited 2024 Feb 29]. Available from: https://www.albertahealthservices.ca/findhealth/service.aspx?Id=1026405&facilityid=1011654

- Métis Nation of Alberta. Nishtohtamihk li kaansyr (understanding cancer) survey 2022. [cited 2024 Feb 29]. Available from: https://albertametis.com/programs-services/health/health-research-and-advocacy/cancer-research/nishtohtamihk-li-kaansyr-understanding-cancer-survey/

- Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, et al. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—A metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Informat. 2009;42(2):377–381. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010

- Harris PA, Taylor R, Minor BL, et al. The REDCap consortium: building an international community of software platform partners. J Biomed Informat. 2019;95:103208. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2019.103208

- Patridge E, Bardyn T. Research electronic data capture (REDCap). J Med Libr Assoc. 2018;106(1):142–144. doi: 10.5195/jmla.2018.319

- RStudio Team. RStudio: integrated development for R. PBC, Boston (MA): R Studio; 2020 [cited 2024 Feb 29]. Available from: http://www.rstudio.com/

- StataCorp. Stata statistical software: release 18. College Station (TX): StataCorp LLC; 2023.

- van Buuren S, Groothuis-Oudshoorn K. Mice: multivariate imputation by chained equations in R. J Stat Softw. 2011;45(3):1–67. doi: 10.18637/jss.v045.i03

- Government of Alberta. Census of Canada | indigenous people Alberta 2023. 2021 [cited 2024 Jun 7]. Available from: https://open.alberta.ca/dataset/487a7294-06ac-481e-80b7-5566692a6b11/resource/257af6d4-902c-4761-8fee-3971a4480678/download/tbf-2021-census-of-canada-indigenous-people.pd

- Alberta Health Services. Breast | get screened 2021. [cited 2024 Feb 29]. Available from: https://screeningforlife.ca/breast/get-screened/#who_should_get_screened

- Alberta Health Services. Cervical | get screened 2021. [cited 2024 Feb 29]. Available from: https://screeningforlife.ca/cervical/get-screened/#who_should_get_screened

- Alberta Health Services. Colorectal | get screened 2021. [cited 2024 Feb 29]. Available from: https://screeningforlife.ca/colorectal/get-screened/#who_should_get_screened

- Mema SC, Yang H, Elnitsky S, et al. Enhancing access to cervical and colorectal cancer screening for women in rural and remote northern Alberta: a pilot study. CMAJ Open. 2017;5(4):E740–E5. doi: 10.9778/cmajo.20170055

- Alberta Health Services. Alberta to expand access to HPV vaccination 2013. [cited 2024 Feb 29]. Available from: https://www.alberta.ca/release.cfm?xID=35503A3262125-A345-59F9-BCA57FD3EEF7375B

- Provincial Immunization Program, Alberta Health Services. Human papillomavirus (HPV-9) vaccine 2024. [cited 2024 Feb 29]. Available from: https://myhealth.alberta.ca/topic/immunization/pages/hpv-9-vaccine.aspx

- Métis Cancer Screening Research Project Team, Ontario Health, Metis Nation of Ontario. Increasing cancer screening in the Métis Nation of Ontario. (ON): Metis Nation of Ontario; 2021. Available from: https://www.metisnation.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/MetisCancerScreeningResearchProject_CommunityResearchReport_final.pdf

- Decker KM, Demers AA, Kliewer EV, et al. Pap test use and cervical cancer incidence in first Nations women living in Manitoba. Cancer Prev Res. 2015;8(1):49–55. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.Capr-14-0277