ABSTRACT

Inuit youth face challenges in maintaining their wellbeing, stemming from continued impacts of colonisation. Recent work documented that urban centres, such as Winnipeg Canada, have large Inuit populations comprised of a high proportion of youth. However, youth lack culturally appropriate health and wellbeing services. This review aimed to scan peer-reviewed and grey literature on Inuit youth health and wellbeing programming in Canada. This review is to serve as an initial phase in the development of Inuit-centric youth programming for the Qanuinngitsiarutiksait program of research. Findings will support further work of this program of research, including the development of culturally congruent Inuit-youth centric programming in Winnipeg. We conducted an environmental scan and used an assessment criteria to assess the effectiveness of the identified programs. Results showed that identified programs had Inuit involvement in creation framing programming through Inuit knowledge and mostly informed by the culture as treatment approach. Evaluation of programs was diffcult to locate, and it was hard to discren between programming, pilots or explorative studies. Despite the growing urban population, more non-urban programming was found. Overall, research contributes to the development of effective strategies to enhance the health and wellbeing of Inuit youth living in Canada.

Trans-Abstract

Inuktitut Translationᑐᓄᐊᐃᓐᓄᐃᑦ ᐅᕕᑲᐃᑦ ᓄᑭᓴᖅᓂᒋᑦ ᓇᒪᑐᒻᒥ. ᐊᕿᓯᒪᓐᓂᖓ.ᐃᖃᓐᓇᐄᔭᒍᓕᕋᑕᖅᑐ ᐊᓪᓚᑳᐅᒻᒪᔪ ᐊᖏᓕᕙᓕᐊᓂᓐᖓᑕᒻᒫᓐᓂ ᐅᐊᓐᓇᐲᒻᒥ ᑳᓐᓇᑕᒻᒥ.ᐊᒻᒪᓪᓗᑕᐅ ᐃᓐᓄᐃᑦ ᐊᒻᒦᓱᓕᖅᓱᑎᑦ ᐊᒻᒪᓪᓗ ᐅᕝᕕᑲᐃᑦ ᐊᒻᒥᓲᓕᖅᒥᓱᑎᑦᐊᒻᒪᓪᓗ ᐅᕝᕕᑲᐃᑦ ᐊᒻᒦᓱᓪᓕᕐᒥᓱᑦᑎᑦᐊᒻᒪᓗᑕᐅᒃᖃᐅᔨᔭᐅᓯᒻᒪᒻᓕᕐᓱᓂ ᐃᓐᓄᓯᐅᑉ ᐃᓪᓗᐊᓐᓂ ᐊᕐᑭᓯᐊᖅᓯᒪᖏᓂᖓᓂ, ᐊᕿᑕᓯᒪᓂᖓᓂ ᐊᒥᓱᓂᖏᑦ.ᓯᕝᕗᒻᒧᐊᖅᑎᒃᓯᔨᐅᒻᒧᖓ ᑐᕌᑎᑕᐅᓯᒻᒪᔪ ᑎᖁᐊᒃᑎᕈᑎ ᕿᒻᒥᕈᐊᔭᐅᒃᑲᓂᖅᐳ ᐊᒻᒪᓪᓗ ᑎᒻᒥᐅᑉ ᐱᖁᓯᖓᑕᐃᓐᓄᐃᑦ ᐅᕝᕕᑲᐃᑦ ᐊᓐᓂᐊᖃᑕᐃᓕᒪᓐᓂᖅᒧᑦ ᐊᕿᓱᐃᖓᓱᐊᓂᖅᒧᑦ ᑲᓐᓇᑕᒥ,ᑕᓐᓇ ᓯᕝᕗᒻᒧᐊᑎᑦᓯᔪ ᑕᖁᓇᖅᑕᐅᖃᓐᓂᒃᑐᖅ ᐅᕝᕙᑎᓐᓂ ᐃᑲᔪᑲᓐᓂᖅᐳᐱᖏᐊᖕᒐᓂᖓ ᓯᕝᕗᓪᓕᖅ ᐊᕿᓱᒃᑐᖅ ᐊᕿᓯᒻᒪᒌᒃᑐ ᐃᓐᓄᐃᑦ ᓄᑕᕋᓄᑦ ᐅᑉᓗᒻᒥᐃᓪᓕᑕᒃᓯᓐᓂᖅ ᓯᕝᕗᓐᓂᑎᓐᓂ ᐊᑑ ᑎᖃᓐᓂᐊᒃᐳ, ᐊᒻᒪᓪᓗ ᐊᑐᑎᖃᒃᓯᒻᒪᔪᓐᓄᑦᓱᕈᓯᒃᓄᑦ ᐅᐊᓐᓇᐲᒻᒥ.ᐃᓱᒻᒪᒃᓴᒃᓯᐅᖅᓂᕿᓐᓂᒃᑕᕗᑦ 2000 ᒥᓐᓂᒃ 2024ᒧᓐᓄᑦ ᖃᕆᑕᐅᔭᑯᑦ ᐅᖃᓕᒻᒫᕕᐅᕙᑐᒥ, ᑎᑎᖃᐅᓯᐊᐳᒍᑦ ᓄᓐᓇᓪᓕᓐᓂᐅᖃᐅᓯᒃᓂ ᑐᓴᒃᑎᑕᐅᒪᕗᒍᑦ ᐃᒃᐱᒍᓱᒃᓯᐊᖅᐳᒍᑦ ᖃᕆᑕᐅᔭᒃᒥᒃ ᐅᖃᓪᓕᒫᒃᕕᐅᕙᑦᑐᒻᒥᐃᓐᓄᐃᑦ ᐊᖏᖃᑎᒌᐳᑦᓇᓪᓕᖃᐃᑦᓇᓐᓂᕙᕝᕗᑦ 26 ᐃᓪᓕᓐᓂᐊᒐᒃᓴᐃᑦ. 18 ᐃᓐᓄᐃᑦ ᓄᓇᒐᓐᓂ. 7 ᓄᓐᓇᓪᓕᓐᓂ. 1 ᑕᒻᒪᕿᓐᓂᑕᖁᐊ ᐃᓪᓗᓐᓇᑎᑦ ᐃᓄᓐᓄᑦ ᑎᑎᕋᒃᑕᐅᓯᒻᒪᔪᑦ ᑕᐃᑯᐊ ᐊᕿᑕᐅᓯᒻᒪᔪ ᐊᕿᒃᓱᕐᑕᐅᔪᖅᐃᓐᓄᐃᑦ ᐃᓐᓄᒃᑎᑐᑦ ᐃᓪᓕᒃᐸᓪᓕᐊᔪᑦ ᐊᒃᓱᕈᓐᓈᓚᐅᒃᐳᒃ ᑐᕿᓯᓪᓗᒍᒪᓪᓕᒐᒃᓴᐃᑦ ᐃᓪᓕᒐᓱᐊᕆᐊᒃᓴᖅᐃᓱᓪᓕᓐᓂᐊᒪᓪᓕᒐᒃᓴᖃᓐᓇᒃᓴᐅᕗᖅ ᑕᐹᓐᓂ ᐃᓐᓄᐃᑦ ᓄᓇᖓᓐᓂ ᐊᒻᒪᓪᓗ ᒫᓐᓂ ᐃᓐᓄᓴᓐᓂᖅᓴᐅᑕᖁᑦᐅᓐᓈ ᐸᐃᐹᖅ ᐃᖃᔪᑎᖃᒃᐳᑦ ᐃᓐᓄᐃᑦ ᐅᕝᕕᑲᐃᑦ ᑲᓐᓇᑕᒻᒥ

Introduction

Inuit youth mental health has received considerable attention in the literature, compared to First Nations or Métis [Citation1], yet the provision of Inuit youth-centric culturally-safe programming to promote well-being has received far less attention. We use Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami’s (ITK) definition for Inuit in Canada, which states “Inuit are an Indigenous people living primarily in Inuit Nunangat … [but] our population is also increasingly urban … Canadian Inuit are young with a median age of just 23” [Citation2] no pagination. There are four regions in Canada, which together are known as Inuit Nunangat: Inuvialuit Settlement Region (Northwest Territories), Nunatsiavut (Labrador), Nunavik (Quebec) and Nunavut [Citation2]. In this review, we include youth programming for Inuit living in Nunangat and elsewhere. Here, a distinction is made between urban and Nunangat programming as it allows for regional differences to be made and for trends and gaps in programming to be made apparent. In our review, all programming identified as Nunangat refers to programming in Inuit Nunangat, whereas urban programming includes those in outside of Nunangat.

The broader Qanuinngitsiarutiksait program of research is focused on mobilising Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit (knowledge Inuit have always known to be true), and Inuit maligait or natural laws to aid the development of Inuit-centric health and wellbeing programing. As a first step, the team focused on documenting patterns of health and social utilisation of Inuit in Manitoba, and Inuit from the Kivalliq region who came to Manitoba to receive services. Given growing Inuit communities outside of Nunangat, there is a need to inform the development of Inuit-centric programming in southern urban contexts. The team documented that there was no Inuit-centric health services or programming in Winnipeg until 2018, despite over five decades of Inuit accessing services in Winnipeg, and a growing Inuit community living in this city [Citation3–8]. However, it should be noted that Winnipeg in not unique, other cities in Canada, including St Johns in the province of Newfoundland, Montreal Quebec, Ottawa Ontario and Edmonton Alberta, have strong and growing Inuit communities.

“Health and wellbeing” was used rather than the more fitting Inuktitut term “qanuinngitsiarutiksait” as this is not yet commonly used in the literature as of yet, apart from Clark and colleagues [Citation3]. Qanuinngitsiarutiksait refers to an all-encompassing idea of wellbeing, which occurs at individual, family and community levels; it is a relational term denoting harmony and physical, emotional, mental and spiritual balance – ideas of good health which are dissimilar to biomedical models (Inuit Elder Tagaaq Evaluardjuk-Palmer, personal communication) [Citation9]. We follow MacLeod’s convention for citing personal communications from Elders [Citation10]. In this review, programming refers to “a treatment, prevention, rehabilitation, or educational service offered by a community health centre or other entity for the purpose of maintaining or improving the mental health of an individual or community [Citation11], no pagination”. In a number of instances, we found the literature to be unclear on whether authors were reporting on an intervention study (pilot) with no sustainability plan, a project or an on-going program.

This paper begins by providing context to health-related issues Inuit face, followed by a detailed methodology for identified youth programming. A summary of identified programs implemented in Canada is provided showcasing their objectives, target populations and methodologies. Lastly, a comprehensive discussion is presented assessing strengths and limitations of programs with gaps identified and recommendations given.

Background

Inuit has always known trauma. Inuit life pre-contact was rewarding, yet periodically resulted in trauma from premature and accidental death, and hunger [Citation12]. Inuit had sophisticated approaches to restoring balance after trauma, which might involve a one-to-one intervention by a loved one or an Elder, an intervention on the family unit, or include the extended family. The objective was never to focus on denouncing, shaming or punishing, but rather to re-establish harmony [Citation13]. All members of the camp were integrated into the task of living well with the land, all had a role commensurate to skills and abilities. Transgressions were healed through taking responsibility, working to rebuild the injured relationship, and restoring harmony. Elder Joe Karetak distinguishes between everyday trauma and colonial trauma. Colonial trauma is insidious, multigenerational and relentless (Inuit Elder Joe Karetak, personal communication) [Citation14].

Colonialism has impacted Inuit health, physically, mentally and structurally. Experiences of residential school have been linked to suicide ideation [Citation1]. Sedentarization had profound impacts on physical health; with this shift in lifestyle, and arguably culture, came sustained long-term contacts with relatives and community members, with little opportunity to step back. Conflicts have been seen to be more frequent and more difficult to dissipate. When families lived in camps, they were active but also autonomous, when camps got together it was seen to be a time of celebration and catching up (Inuit Elder Joe Karetak, personal communication) [Citation14]. Further, the medicalisation of birth and associated displacement of Inuit midwifery knowledge has resulted in two generations of Inuit women delivering in urban centres away from family. While advances in public health, medicine and the social welfare in Canada now deliver preferential quality of life to Canadians compared to many countries, the health and wellbeing of Inuit are considered a public health emergency among Inuit: youth suicide rates are 10 times higher than among non-Indigenous youth [Citation15] with rates highest among young men [Citation16]. The Aboriginal People’s Survey identified suicide ideation risk was increased by 57% for Inuit [Citation17]. Note that data sets from Statistics Canada contain inaccuracies especially for those populations with smaller sample size such as Inuit, and that there is a general dearth of regional and country-wide data on Indigenous people in Canada.

Poor health and wellbeing grew in the 1970s among the first generation of Inuit to grow up in settlements and has continued since [Citation18]. Currently, Inuit report high rates of poverty, unemployment, household crowding, food insecurity, poor mental and physical health. This is compounded by poor access to culturally appropriate health services and multiple barriers to access specialised health care [Citation19]. The literature proposes that inequitable access to social determinants of health is at the root of contemporary Inuit experiences of poor health and wellbeing [Citation18], e.g. poor housing or education, impacting social and economic opportunities which are rooted decisions made by and for Canadian settlers. In comparison with other Indigenous groups in Canada, many Inuit personally witnessed and experienced the pruning of their political autonomy, and the destruction of their economic and food systems [Citation20–22].

According to the literature, protective factors of health and wellbeing for Indigenous youth include a strong sense of cultural affiliation and identity, with the opportunity to be able to explore one’s cultural identity, community cohesion, spending time on the land and environmental stability; these aspects inform best practices for Inuit youth program delivery [Citation23–28]. The literature has begun to explore Inuit conceptualisations of wellness [Citation29] and notes that the main risk factor to health and wellbeing is a lack of opportunity to engage in cultural activities or traditions [Citation25,Citation30]. Further, the literature notes a needed shift in programming terminology, where the focus is not on existing deficits, but rather a strengths-based approach to promote cultural resilience. For example, health and wellbeing programming should not be specifically termed “suicide prevention programming” as this can give the wrong message to youth: it was noted that youth may think that participating in a program termed “suicide prevention” might imply a requirement to have suicide ideation [Citation27,Citation31,Citation32]. This shift in terminology is reflected in the literature searches used, as strengths-based terms were used to find programming as well as terms such as “suicide programming”.

Changes to weather, based in global climatic changes, are impacting the integrity of the ice, delaying snow falls. For Inuit, the land, nuna, includes sea ice; when snow covers the land, Inuit can travel between communities, to cabins and carry out hunting/harvesting activities. In this sense, the land and sea ice are highways. If the snow cover is insufficient, or the ice undependable, Inuit are essentially captive to the community and more susceptible to food insecurity. Literature has highlighted how this captivity has impacted negatively mental health, with Inuit highlighting that they feel like a “caged animal” or “feeling trapped” which again increased conflict due to being confined [Citation33,Citation34]. This can greatly impact health and wellbeing particularly when traditions are heavily based on land activities, particularly for those living in Northern Canada [Citation35,Citation36]. Exploration of climatic impacts on Inuit health has unpicked these adverse effects, which are broadly related to: mental health, food security, disease, water insecurity and ice-related incidents [Citation37]. Although, as shown above, it should be noted that these categories are interconnect. Being on the land is a protective factor of youth health and wellbeing as it is a direct tie to an Inuit concept of identity and authenticity. This connection has not been widely explored in an urban setting, beyond “climate doom” discourses suggesting that there will be no Arctic to go back to, and therefore no way to recover or develop a sense of an “authentic Inuit identity” [Citation38].

Overall, these contextual factors are necessary to understand the current landscape for Inuit youth, to highlight the timeline for change in Inuit wellbeing has been impacted relatively recently and to show the urgency of youth health and wellbeing supports. This contextualisation emphasises that best practices for maintaining Inuit health and wellbeing are through community-based supports that build and expand on traditional ways to restoring balance and harmony. This will be seen to inform the criteria used for assessment of identified programs. The current actors in Inuit health and wellbeing programming are mainly university-based research teams, non-governmental organisations, and the Canadian (federal, provincial territorial) governments. Arguably, the Canadian government has the largest influence in long-term change in this space in terms of sway and allocation of funding towards the fostering of such programming. However, due to the lack of attention Inuit youth receive in supporting their health and wellbeing, research and short-term funding appears to play a major role in the creation of innovative, and usually short lived, programming for Inuit youth especially in urban centres. We note a definite misalignment between this state of affairs, and Canada’s commitment to the implementation of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada’s calls to action, the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples and the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child, which hold government accountable towards these Inuit youth health and wellbeing supports are highlighted.

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada’s final report [Citation39] calls the nation to move towards reconciliatory actions by addressing the social inequalities that face Indigenous communities. More specifically, it calls the federal government to “close the gaps in health outcomes between Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal communities” (p. 2–3), which includes both mental and physical health-related issues. The call to action 66 specifically applies to the federal funding of multi-year youth community-based organisations [Citation39], p.8. something which, as discussed below, is lacking in practice, although the Canada Health Act 1984 states that it should “protect promote and restore the physical and mental well-being of residents … to facilitate reasonable access to health services without financial or other barriers” [Citation40], p.5. Also, the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples states that Indigenous peoples have the right to self-determination and adequate resources in their territories [Citation41]. Furthermore, the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child states that youth have the right to enjoy the highest standard of health, which includes mental health [Citation42]. Thus, these provisions reinforce the importance of youth mental Indigenous health and the responsibility which the federal government incurs for this. Recommendations of best practices in programming towards the end of the review highlight the ways in which governmental actors can support this area.

Methods

The objective of this environmental scan was to identify Inuit health and wellbeing programming. An environmental scan was chosen because it provides the flexibility to include peer-reviewed and grey literature [Citation43,Citation44]. Environmental scans are useful in health settings as they are a “needs-assessment tool that can be utilized to collect program development data”: it is an action-orientated approach that facilitates the use of findings for the implementation of change in health programming [Citation45] p.528. Further, an environmental scan was chosen to allow the inclusion of grey literature, as it was thought that programming from community based organistions is often not represented in academic journals. It is noted that there is a lack of consensus in the literature of the definition and methodology of an environmental scan [Citation45,Citation46]. To mitigate confusion, a comprehensive methodological process for the environmental scan is outlined in this section.

Research aim

As the aim of this review is to identify and then synthesise the findings from Inuit youth health and wellbeing programming in Canada, a suicide specific programming search was also used. This was chosen given the high rates of youth suicide in this population, to ensure that these programs were not missed given that they may use different language that might not get picked up in a “health and/or wellbeing” search.

Search strategy and data extraction

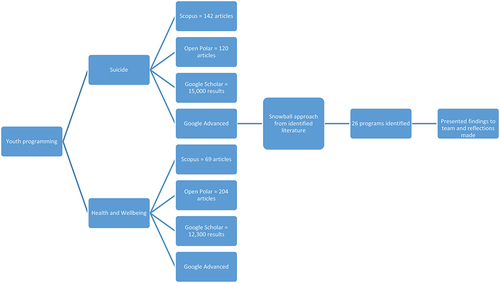

Searches relating to suicide and general health and wellbeing from Scopus, Open Polar, Google Scholar and Google Advanced were used to identify Inuit youth programming. The Google Advanced search was used to identify grey literature. Searches were conducted an Indigenous health librarian. The search terms are outlined below and visually demonstrated by .

Suicide Prevention Programming

The terms Suicide* OR parasuicide* AND Inuit* OR Nunavut OR Iqaluit OR Nunavummiut OR Kitikmeot OR Kivalliq OR Qikiqtani OR Baffin OR Kuujjuaq OR Inuvialuit OR Nunavik OR Nunatsiavut OR Nunangat OR Inupiaq OR Inuk OR Inuktitut were put into Scopus yielding 142 articles

Open Polar was used with a filter applied to “Canada” and years 2000–2024 with search terms: Suicide AND Inuit, yielding 120 articles

Google Scholar search with the terms: Inuit Canada, Suicide parasuicide, with publication date limit 2000–2024. This yielded 15,000 results, as articles are sorted by relevance, first five pages were looked at.

Google Advanced was used to find grey literature and reports from community-based organisations. Search terms: Inuit Canada suicide prevention Nunavut, with region set to Canada and file type to Adobe Acrobat PDF, again first five pages of results were looked at.

Health and wellbeing programming

Terms Inuit* OR Nunavut OR Iqaluit OR Nunavummiut OR Kitikmeot OR Kivalliq OR Qikiqtani OR Baffin OR Kuujjuaq OR Inuvialuit OR Nunavik OR Nunatsiavut OR Nunangat OR Inupiaq OR Inuk OR Inuktitut AND OR wellbeing OR “well being” OR resilience* were put into Scopus yielding 39 articles

Second Scopus search using terms: AND Youth* OR adolescence* OR child* yielding 30 articles

Open Polar was used with a filter applied to “Canada” and years 2000–2024 with search terms: Inuit, youth wellness OR resiliency OR resilience OR wellbeing, yielding 204 articles

Google Scholar search with the terms: Inuit Canada youth and Wellness wellbeing resiliency, with publication date limit 2000–2024. This yielded 12,300 results, as articles are sorted by relevance, first five pages were looked at.

Google Advanced was used to find grey literature and reports from community-based organisations. Search terms: Inuit youth Canada program AND wellness wellbeing resiliency, with region set to Canada and file type to Adobe Acrobat PDF, again the first five pages were looked at.

A snowball approach was also used to find further programming that was cited or mentioned from those that came up in the above searches. This additional method was used as it was found that there was a higher proportion of Inuit youth health and wellbeing found from grey literature. For example, three programs included in this review were identified from peer-reviewed literature, supplemented with online platforms for these programs, e.g. a website for the program or the community-based organisation running the program sharing further information.

Inclusion criteria for programs

The following criteria were used for inclusion: programming pertaining to Inuit youth from 2000 to 2024 that helped to foster health and wellbeing. We included some programs that are Indigenous-centric (meaning that might include Inuit as well as First Nations and Métis), if they had facets of programming that were Inuit-specific, or they included Inuit youth in their programming. At times, it was unclear what specifically was a program, as some are more like “studies” that created short-term programming or pilot programming with little follow through.

In total, 26 programs were included. Following a preliminary analysis, the findings were presented back to the team (Elders, Inuit and university-based researchers who are part of the Qanuinngitsiarutiksait study) for feedback, reflection and discussion and integrated in this paper.

Programming assessment

Articles identified through the outlined search process and meeting the inclusion criteria were assessed through the following additional criteria:

Location of the program (urban or Nunangat)

Initiative format (program, study, pilot, peer-reviewed or grey literature)

Inuit engagement in creation

Culture as treatment versus culture in treatment

Inuit knowledge informed

Community-led/based programming

Program Evaluation

Identified Programming Strengths

This criterion was informed by best practices for working with Indigenous communities [Citation47,Citation48]. Culture was included as an assessment category, mainly because access to programming that is culturally congruent has been shown by the literature to be a protective factor of wellbeing [Citation26,Citation29,Citation49]. In this review, we divide interventions into two broad categories. Culture as treatment programs refer to programs that are grounded in the culture of those to benefit from the programming [Citation50] stemming from the particular culture, i.e. in this context, this could refer to land-based treatment and working with Inuit Elders to identify knowledge and approaches. Culture as treatment is widely accepted as yielding positive outcomes [Citation51–53]. In contrast, culture in treatment programs refer to programs where cultural elements are added to a Western informed program, to adapt it and make it more culturally appropriate. These approaches can be helpful (e.g. providing translation in a Western informed treatment, room decorated with posters or art reflecting the culture of the population served), but risk being tokenistic, e.g. a psychologist adding a smudge to make the work more culturally appropriate. The premise of the approach, however, remains grounded in Western thinking and cultural assumptions, thereby reproducing assumptions about individual versus collective identity and responsibilities that might be culturally inappropriate.

The list of included programs, along with a short description, and their assessment through the outlined criteria can be seen in Table S1 of the additional material.

Results

Detailed results of this literature review are shown in Table S1, in the additional material. Some general observations are firstly made: Table S1 shows less urban programming (seven programs), in comparison with Nunangat programming (18 programs); further, only one program covers both urban and Nunangat Inuit youth. Despite Inuit-specific search terms, many more First Nations-centric youth programming was found. The suicide-related Scopus search conducted showed that there was more Yupik youth-related programming [Citation54–59]. Also, for the wider health and wellbeing Scopus search, a large number of programming were related to sexual health (eight programs), suggesting that this is an area of wanted focus for, or perhaps by, Indigenous youth, although it was not clear from the review who set this as a priority. The rest of the results section is organised via the programming assessment criteria as shown in Table S1 and outlined in the methods section.

Location-specific observations

Programming outside of Nunangat

Program format

Our search identified fewer urban programming, in comparison with Nunangat programming; and, of the seven urban programs located (Tunngasugit, [Citation51]Tungasuvvingat Inuit, [Citation60] Aboriginal Health and Wellness Centre of Winnipeg [Citation61], Two Years of Relationship-Focused Mentoring, [Citation27] Sexy Health Carnival, [Citation52] Nimkee Nupigawagan Healing Centre, [Citation62] BluePrintForLife [Citation63], four were found from grey literature, (Tunngasugit, [Citation51] Tungasuvvingat Inuit, [Citation60] Nimkee Nupigawagan Healing Centre, [Citation62] BluePrintForLife [Citation63], two were in grey and academic literature (Sexy Health Carnival, [Citation52] Nimkee Nupigawagan Healing Centre [Citation62], and one just from academic literature (Two Years of Relationship-Focused Mentoring [Citation27]. Only two urban programs which offered land-based treatment, Tunngasugit [Citation51] and Nimkee Nupigawagan Healing Centre [Citation62]. Four of these programs were not Inuit-centric, focusing rather on First Nations and Inuit populations. Despite this, Sexy Health Carnival [Citation52] and BluePrintForLife [Citation63] provided adaptations (such as being informed by Inuit knowledge and cultural understandings) to allow programming to be Inuit-specific. Further, Tungasuvvingat Inuit [Citation60] and BluePrintForLife [Citation63] had specific initiatives to engage with youth that had encountered the justice system, and Sexy Health Carnival [Citation52] had programming specifically for two-spirit individuals.

Inuit engagement or collaboration in programming

All programs had Indigenous engagement in creation and collaboration. If the program was not Inuit-centric, (Aboriginal Health and Wellness Centre of Winnipeg [Citation61], Two Years of Relationship-Focused Mentoring [Citation27] and Nimkee Nupigawagan Healing Centre [Citation62]), there was still Indigenous engagement in creation and collaboration, and those that were Inuit-centric had Inuit engagement in creation and collaboration, e.g. from the community or Elders.

Culture as treatment versus culture in treatment

All programs, but one (Two Years of Relationship-Focused Mentoring [Citation27]), were informed by a culture as treatment, rather than a culture in treatment framework. Often this was in the form of culturally based activities for youth, such as celebrating Nunavut Day, music workshops (including throat singing and traditional song writing), language classes, craft activities (e.g. making amautis, pualuk, beading work) and culturally based recreational trips such as skating. One program, BluePrintForLife [Citation63], was very innovative in their approach to engage youth as they took hip hop dance but modified it so that it was culturally relevant for Inuit youth to use as a toolkit to engage with contemporary issues in the community; even combining Inuit throat singing with beatboxing, “throat boxing”. Counselling services were offered by four programs adapted for an Indigenous audience. The Aboriginal Health and Wellness Centre of Winnipeg [Citation61] also worked in collaboration with other healthcare professionals to provide care.

Inuit knowledge-informed

All Inuit-centric programming was informed by Inuit knowledge, and those that were not Inuit-centric were informed by First Nation knowledge, e.g. Medicine Wheel teachings. Most of these programs were found from grey literature.

Program evaluation

Although evaluation reports for programs could not be located, Nimkee Nupigawagan Healing Centre [Citation62] and BluePrintForLife [Citation63] specifically pointed out that they continually monitor and evaluate programming, with Nimkee Nupigawagan Healing Centre stating that they provide ongoing training to staff where appropriate.

Nunangat-based programming

Program format

Eight Nunangat-based programs were found in the grey literature, (Embrace Life Council, [Citation64] Pulaarvik Kablu Friendship Centre, [Citation65] Inuusirvik Community Wellness Hub [Citation66], Aqqiumavvik, [Citation53] lisaqsivik, [Citation67] Project Creates, [Citation68] Inuvialuit, [Citation69] Camp Eclipse [Citation70] six in academic journals (Building on Strengths in Naujaat, [Citation71] Adolescence and identity in Inuit territory, [Citation72] In the Black Box of Igloolik, [Citation73] The Eight Ujarait, [Citation74] Learning from the Land, [Citation75] Using Photovoice to understand Inuit Intergenerational Interaction [Citation76] and three were found on both platforms (Going Off Growing Strong [Citation77], Spaces and Places, [Citation78] Qanuilirpitaa? [Citation79]. At times, it was hard to distinguish whether the programming found only in academic journals was intervention research, a pilot program or programming with long-term plans. Five of these programs used arts-based methods to engage youth (Spaces and Places, [Citation78] Aqqiumavvik, [Citation53] Project Creates, [Citation68] Using Photovoice to understand Inuit Intergenerational Interaction, [Citation76] In the Black Box of Igloolik [Citation73] often this took the form of youth taking videos or photographs (photovoice) or creating murals/culturally based crafts or films on aspects of qanuinngitsiarutiksait. Often, these programs also disseminated their projects or findings back to the community using these approaches. Justification for arts-based methodology in this field was given due to the alignment with Inuit culture, e.g. being based on an oral culture that uses storytelling as a way of teaching [Citation66,Citation72,Citation73,Citation80,Citation81]. One organisation, Pulaarvik Kablu Friendship Centre [Citation65], offered male-centric programming and another, Camp Eclipse [Citation70], offered programming specifically for 2SLGBTQIA+.

Inuit engagement or collaboration in programming

All programs reviewed involved Inuit engagement in their creation, mainly through being co-created with the community or being Inuit designed and led. One program, Adolescence and Identity in Inuit Territory [Citation72], was entirely led by youth.

Inuit knowledge informed

Further, all programming was informed by Inuit knowledge, e.g. through cultural values or being based in Inuit research methodologies. Additionally, all programming was done in collaboration firstly with the community where appropriate relationships were made, e.g. Nunatsiavut government, local councils or local health and social services.

Culture as treatment versus culture in treatment

Further, all programming used culture as treatment. This was done through using arts-based methodologies and engaging youth in culturally relevant activities (e.g. sewing circles, creation of jappas, sealskin and beaded earrings workshops, cultural nursery rhymes and introduction of cultural foods for infant programming and prenatal programming based in cultural nutrition and teachings), connecting youth to the community and land-based activities (e.g. hunting, fishing, gathering wild plants and cabin building). Counselling services were offered by six programs. lisaqsivik [Citation67] offers a counsellor training course in Inuktitut: this is the only one we could find.

Program evaluation

Again, it was difficult to determine the extent to which programs were evaluated. A Board of Directors existed for six programs and fourteen mentioned that they reflected on prior stages of programming through their own evaluation, participant evaluation and evaluation in the form of discussion with the community.

Urban and Nunangat programming

Only programming offered by the Mental Health Commission of Canada [Citation82] pertained to urban and Nunangat youth health and wellbeing. The program Mental Health First Aid was created by Inuit for Inuit and those that work with Inuit; it is a course that aims to help with understanding and dealing with issues of wellbeing. While this course includes the importance of cultural knowledge, it does seem to have a more Western approach to programming. The Commission also offers another program, Roots of Hope, which describes itself as “a multi-site, community-led project that aims to reduce the impacts of suicide within communities across Canada … project builds upon community expertise to implement suicide prevention interventions that are tailored to the local context” (no pagination). Currently, this program has been implemented in some Indigenous communities in Newfoundland and Labrador, New Brunswick, Saskatchewan, Alberta, Ontario and Nunavut; with the expectation that more provinces will join. From this, it seems as though this program takes more of a pan-Indigenous approach and does not outline how local knowledges are engaged with, and how collaboration takes place. It is unclear whether these programs offered by the Commission have been evaluated.

Identified programming strengths

Programming seems to have the most scope when it takes a life course approach and focuses on health and wellbeing. This allowed infants (and parents), teenagers (parent engagement did not seem to exist in the programs were reviewed), adults and Elders to be involved in the maintenance of their qanuinngitsiarutiksait. For example, Tunngasugit [Citation51], the Pulaarvik Kablu Friendship Centre [Citation65] and the Aboriginal Health and Wellness Centre of Winnipeg [Citation61] offer prenatal programming and specific cultural classes for young infants while providing other age-specific programming across the life course. The Nimkee Nupigawagan Healing Centre [Citation62], Tunngasugit [Citation51], Tungasuvvingat Inuit [Citation60], Going Off Growing Strong [Citation83] and lisaqsivik [Citation67] have campaigns that assist with accessing health and social services, employment readiness support, e.g. writing resumes, and help with applying for social assistance and support systems for, and issues relating to lasting impacts of residential schools. Additionally, Embrace Life Council [Citation64] and Going Off Growing Strong [Citation83] provided drop-sessions for youth after school, offering them a space to spend time or to have help with homework.

Programs suggested that taking a life-course approach is a way to impact qanuinngitsiarutiksait at all levels of society. However, the evidence for reaching this conclusion was not stated. For example, this way of working is mentioned by Tunngasugit [Citation51], Aboriginal Health and Wellness Centre of Winnipeg [Citation61] and Brighter Futures (part of the Inuvialuit Regional Corporation) [Citation69], with the Aboriginal Health and Wellness Centre specifically stating “an individual member’s wellness reflects community’s wellness and that wellbeing as individuals and as a community is connected to all people and things” (no pagination). Other factors which seemed to be of value in programming include Elders leading youth programming, mostly seen in relation to leading segments of land-based programming or leading language classes (e.g. Nunami iliharniq [Citation75] and Tunngasugit [Citation51], and engagement with the justice system, e.g. Tungasuvvingat Inuit [Citation60] and BluePrintForLife [Citation63]) work specifically with incarcerated youth. Further, school-based programming seems a good way to connect with youth in a meaningful way and boost engagement, as seen in Spaces and Places [Citation80] and Inuusirvik Community Wellness Hub [Citation66]. In some cases, programming did not directly involve youth, but instead partnered with local high schools to make youth know of programming available, as seen in Nunami iliharni [Citation75] and Adolescence and identity in Inuit territory [Citation72]. Of the seven urban programs, it was noted that only two offered land-based programming, namely, Tunngasugit [Citation51] and Nimkee Nupigawagan Healing Centre [Citation62], while all Nunangat programming offers this.

A number of organisations (Tunngasugit [Citation51], Embrace Life Council [Citation64] and Aqqiumavvik Arviat Wellness Society [Citation53], Embrace Life Council [Citation64]) reflected that the increase in use of technology for youth engagement, at least in an urban environment, could facilitate greater engagement with programming if organisations had accessible websites with social media platforms, e.g. Instagram and blogs. This was noted primarily in the grey literature. Existing websites included resources and handouts for individuals and organisations to download, e.g. wellbeing toolkits or culturally specific colouring pages for children. This was seen with Tunngasugit [Citation51], Embrace Life Council [Citation64] and Aqqiumavvik Arviat Wellness Society [Citation53], with Aqqiumavvik offering culturally specific cooking video tutorials. The Embrace Life Council [Citation64] had competitions with youth could engage through social media platforms, e.g. snow making sculptures.

All programming, apart from Aboriginal Health and Wellness Centre of Winnipeg [Citation61], Two Years of Relationship-Focused Mentoring [Citation27] and Nimkee Nupigawagan Healing Centre [Citation62], were specifically Inuit knowledge-informed. These programs that were not Inuit knowledge-informed still included Inuit in the remit of their reach, while explicitly mentioning that programming was informed by First Nation knowledge. While being informed by Inuit knowledge, through Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit, some programs specifically mentioned the use of specific models: Piliriqatigiinniq Partnership Model (Inuusirvik Community Wellness Hub), Eight Ujarait model (Eight Ujarait), IQI Model (Qanuilirpitaa?) and the Qaggiq model (Nunami iliharniq).

Other studies

In addition to programs already discussed, other useful studies came up in the Scopus searches; although not pertaining to youth health and wellbeing programming, they have useful material which should be considered in youth programming. One study explored gastrointestinal illness in Rigolet (Nunatsiavut) using a whiteboard video methodology, a form of arts-based method, to engage participants [Citation84]. In an urban First Nation setting, the inclusion of Elders in programming was found to have positive impacts on participants’ health and wellbeing [Citation85]. Lastly, it should be noted that programs that are adapted from a Western context to an Indigenous setting may not always be effective; for example, an anxiety prevention program took this approach, and while it was successful in a Western setting with the World Health Organisation recognising it to be an “effective toolset to prevent anxiety for children”, [Citation86] no pagination it was found to be unsuccessful when implemented in a pan-Indigenous setting [Citation87].

Discussion

Overall, the results show that there are few Inuit-centric youth programming outside of Inuit Nunangat; this was somewhat expected given the historical invisibility of Inuit populations in urban settings [Citation3]. Our review highlights that impactful programming tends to take a life-course approach, while assisting with health and social services, allowing for all levels of society to be reached: individual, family and community. Inuit cultural specifies also allow for impactful programming, such as Elders leading programming, land-based activities (although this does not happen readily in an urban setting), language classes, cultural-orientated activities for youth, and engagement with incarcerated youth. Partnering with local schools, with Inuit populations, allows engagement/partnerships to be built between those on the research side of programming interventions, allowing for fruitful insights. From our perspective, we see tremendous value in programming being described on an online platform as there tends to be a lack of published academic literature on Inuit-centric programs despite needs.

Despite attempts, it was consistently difficult to distinguish between studies and programs, due to the lack of consistency in the literature around the meaning of programming in a healthcare setting in this context, i.e. discerning the difference between a pilot, long-term programming or just a study. Studies were included because they yield valuable information, although they do not always lead to the implementation of long-term programming, e.g. Two Years of Relationship-Focused Mentoring [Citation27], Growing Off Growing Strong [Citation83], or Spaces and Places [Citation80]. Some publications provided an analysis of already published quantitative or qualitative data, at times in the form of a meta-analyses, exploring: risk factors, protective factors or what is needed for the implementation of programming (these are not included in Table S1) [Citation26,Citation88,Citation89]. For Nunangat programming, the literature suggests that effective programming includes land-based programming, and programming fostering community connections, e.g. Building on Strengths in Naujaat [Citation15], Growing Off Growing Strong [Citation83], Spaces and Places [Citation80]. It is noted that the discontinuity of youth programming in a Nunangat context is mainly due to issues of funding as well as youth engagement and local leadership [Citation75]. Presumably, these issues would also exist in an urban context; however, this was not documented in the studies and programing we reviewed.

There needs to be more transparency in the literature about what is being reported on: is it a study, a pilot program, or does the intervention need to be established for some years before it can be called a program? In an urban context, often there was a lack of specific information needed for program assessment, e.g. community focus, who it was informed by. It was noted from “successful” programming that although the intervention had fruitful outcomes, it could not continue due to funding issues. This, taken along with call to action 66 from the Truth and Reconciliation Commission report, suggests that the target of multi-year funding for projects has not been met. The Mental Health Commission of Canada offered what seemed as relevant programming [Citation82], but there was lack of clarity on information surrounding the programming. This lack of signposting was also an issue for Inuit-centric programming on the Nunavut Department Health Website; information found here only pertained to medical intervention.

The most informative combination of material we reviewed included a published paper that is written about an existing program, accompanied with an online platform, e.g. Sexy Health Carnival [Citation52,Citation90], Nimkee Nupigawagan Healing Centre [Citation62,Citation91] and In the Black Box of Igloolik [Citation73,Citation92]; allowing for a wealth of knowledge and insights on the program. We identified an even more effective model for the transfer of knowledge about a specific program included a statement of the rationale for the program, followed by literature review with summary of results, a detailed discussion of the program created (preferably co-created with community and/or Elders) with this resulting in a tangible program. For example, Eight Ujarait [Citation74] almost does this; however, this program appears to have been limited to a pilot project, despite the program having existed for a few years. A program evaluation took place, with findings synthesised into a report, informed by participants, parents and the project co-ordinator. It notes that sustainable funding for a project such as this is needed; recommending schools in Nunavut taking up this activity with implementation supported by the Government of Nunavut [Citation93].

The grey literature, publicised on organisations’ websites, seemed to be more fruitful for identifying relevant content, i.e. those pertaining to Inuit youth health and wellbeing programming. One could assume that programming which is online would have more engagement from youth. Only two studies, Eight Ujarait [Citation74] and Sexy Health Carnival [Citation52], had journal articles published by those who also were involved in the running of the programming. One, Nimkee Nupigawagan Healing Centre [Citation91], had a journal article and a website, but it was not clear if the author of the article was involved with the programming or whether this publication was produced by a third party. This suggests that organisations which are running programming may not see publishing in academic journals as a priority or have the resources to do so.

Some programs picked up from academic searches just use the terms “Indigenous” or “Aboriginal” and did not clarify what this means in their contexts. This is often followed with further lack of specifics, making it hard to make judgement on Inuit engagement in creation or if programming is Inuit-knowledge informed. Further, some publications which seem a blend of program versus study use measures that have not been evaluated among Inuit, or even Indigenous contexts. For example, Two Years of Relationship-Focused Mentoring [Citation27] uses measures such as the Mental Health Continuum-short form and the Likert scale among others. Determination of whether a program has been evaluated that was difficult especially when information was found in the grey literature, e.g. an organisation’s website, whereas often journal publications make this clearer.

The analysis presented above suggests the following programming gaps. There was a lack of Inuit two-spirit-specific programming. The term “two-spirit” originated in 1990s at a time when Western understandings of binary groupings of sex and gender were being challenged [Citation94]. For Inuit, this flexibility in gender has always existed; however, with colonial impacts (namely, indoctrination into Christianity), this fluidity is now seen by some as a Western construct, and Inuit youth can have difficulty engaging with this side of their identity [Citation89]. Now, due to a shift in Western understandings of gender, current understandings of Inuit conceptualisations of gender are moving towards a decolonised understanding [Citation94]. However, it is thought that it will take time for these opposing beliefs to be reconciled due to the relative recent history of colonisation for Inuit. Given this, from the outset of the review, it would have been thought that programming would have engaged with non-binary notions of genders. Further, there was a lack of programming specific to boys and/or young men. Again, it was thought that this would have been a focus of intervention, it is known that in this community, suicide rates are higher among boys/young men [Citation95]. The literature has suggested that young men have difficulty navigating the shift in their gender role. Roles have shifted after colonial impacts, for example a traditional role would relate to being the “provider” for the family or community through activities such as hunting [Citation89]. While a general lack of urban programming exists, this programming tends not to engage with land-based activities for youth when the literature confirms that going onto the land and taking part in associated cultural activities, e.g. hunting or fishing, are established protective factors for wellbeing [Citation36]. Further work should engage with Inuit perspectives of ways to engage with the land in an urban setting. Sexual health was a focus for many programs, but it was unclear where this direction came from; further research should clarify this focus.

Recommendations

From this review, our team recommend that the following issues should be taken into consideration by those engaged with programming implementation across the board, relevant government departments, those already running programming and wanting to engage with programming in the future.

Inuit perspectives must be included in decisions around the focus of programming, and community input should be reported on (e.g. the repeated emphasis on and origin of sexual health in the programming we reviewed).

Sustainable funding is made available for Inuit youth health and wellbeing programming that have been shown to have positive impact.

There needs to be more urban Inuit youth-centric programming with a shift towards long-term programming that includes land-based activities. It could be useful to collaborate between urban and Nunangat settings to share best practices from Nunangat to see if approaches could be adopted and adapted to an urban setting.

The definition of what “programming” means in this context needs to be established, along with greater clarity of if/how programs are evaluated. The internet should be used to disseminate programming, including the details of the program and any evaluation conducted. Young men/boys-centric programming and two-spirit-centric programming were lacking and remain an important gap.

Some programs mentioned the specific Inuit-centric models which informed their programming practice, e.g. Piliriqatigiinniq Partnership Model or the IQI Model. These should be considered by those doing further work in this field and could provide as a springboard for further programming to be taken up and adapted in different geographical locations with similar issues and contexts to where these models were created. If an approach such as this is taken up, community engagement along with adaptation to specific contextual realities of the community are needed to be taken into consideration. This approach would allow for programming that is known to have positive outcomes to be implemented where it is needed without “reinventing the wheel” for programming implementation.

The best practices identified should continue in future programming: Inuit engagement in creation of programming that is community-based or led, and Inuit knowledge informed. Notable examples of these best practices include Elders and/or youth-led programming, land-based programming, language classes, cultural-orientated activities for youth, engagement with incarcerated youth, programming partnering with schools and programming showcased on an online platform. Overall, implementation of youth programming allows in turn for a life-course approach to be taken in assisting health and wellbeing across individual, family and community levels of wellbeing to be fostered.

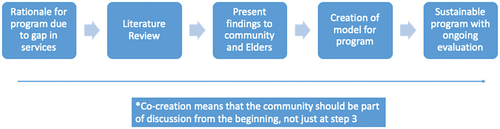

Based on our analysis, we see a recurrent process emerging as a promising practice in program creation. This is visually explained in , and explained below (the Qanuinngitsiarutiksait program of research follows this methodology):

Rationale for program due to gap in services

Literature Review

Present findings to youth, community and Elders – process should be guided by Elders and community who should be kept in the loop throughout via discussions or workshops

Co-creation of model for program, preferably with youth

Implementation of sustainable program which has ongoing evaluation

Limitations

It should be noted that there are various limitations to this review. Evaluations of programming were not located in many instances; it could be that they do not exist or that they were not found. If the former is true, then this needs to be taken into consideration and if the latter is true, then this needs to be made clearer. Along with this issue, many programs mentioned that they had a Board of Directors, but in all cases, it was not defined what this meant, e.g. if the Board evaluated programs. Programs were only found using the methods stated, and due to the high frequency of programming found in grey literature, implying use of the internet, it is possible that some programming may have been missed. Also, our review could not assess the uptake of Inuit youth having access to these programs. In this review, we did not look closely at the team who developed and implemented the programs. We recognise that this could have been informative and believe that inter-disciplinary teams might be better positioned to implement more successful approaches. This type of analysis remains to be pursued.

Conclusion

The results of this review, placed in a comprehensive contextual understanding of the issues that Inuit face, form a foundation for assessing the effectiveness of existing programming for Inuit youth health and wellbeing “qanuinngitsiarutiksait” and will be an invaluable resource to serve as the starting point for future youth culturally appropriate programming. Results show the various initiatives, intervention and projects that have been implemented for Inuit in Canada and are assessed through relevant categories to show their effectiveness and to serve as a baseline of information of working in this context. Analysis of results suggests that there are various gaps in programming that need to be addressed, and the review has provided recommendations for ways to move forward. Attention should be paid towards the “promising practices” approach for future work in this field. Overall, concerted effort is needed to promote culturally relevant and safe programming, as well as more training of local staff and enhanced partnerships at governmental and regional and community levels.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (34.6 KB)Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the assistance of the university of Manitoba’s Faculty of Health Sciences Indigenous health librarian, Janice Linton, who led the development of the searches for this review. We would also like to acknowledge the translation services provided by the Manitoba Inuit Association.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/22423982.2024.2376799

Additional information

Funding

References

- Nelson SE, Wilson K. The mental health of Indigenous peoples in Canada: a critical review of research. Soc Sci Med. 2017 Mar;176:93–15. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.01.021

- Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami. About Canadian Inuit. [cited 2023 Jul 11]. Available from: https://www.itk.ca/about-canadian-inuit/

- Clark W, Lavoie JG, McDonnell L, et al. Trends in Inuit health services utilisation in Manitoba: findings from the Qanuinngitsiarutiksait study. Int J Circumpolar Health. 2022 Dec;81(1):2073069. doi: 10.1080/22423982.2022.2073069

- Lavoie J, McDonnell L, Nickel N, et al. Inuit mental health service utilization in Manitoba: Results from the Qanuinngitsiarutiksait study. Int J Circumpolar Health. Under Review.

- Zulich C, Lui S, Perez S, et al. Qanuinngitsiarutiksait – exploring Inuit youth experiences in an urban setting through photovoice. Int J Circumpolar Health. Under Review.

- Lavoie J, Clark W, McDonnell L, et al. Kivalliq Inuit women travelling to Manitoba for birthing: findings from the Qanuinngitsiarutiksait study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2022;22(1):870. doi: 10.1186/s12884-022-05214-9

- McDonnell L, Lavoie J, Clark W, et al. Unforeseen benefits: outcomes of the Qanuinngitsiarutiksait study. Int J Circumpolar Health. 2022;81(1):2008614. doi: 10.1080/22423982.2021.2008614

- Lavoie J, McDonnell L, Nickel N, et al. Understanding Manitoba Inuit’s social programs utilization and needs: methodological innovations. Int Indigenous Policy J. 2021;12(4). doi: 10.18584/iipj.2021.12.4.13690

- Evaluardjuk-Palmer TN. Lives in Brandon. Oral Teaching. 2023.

- MacLeod L. More than personal communication: templates for citing Indigenous elders and knowledge keepers. KULA. 2021;5(1):1–5. doi: 10.18357/kula.135

- American Psychological Association. Mental health program. [cited 2023 14]. Available from: https://dictionary.apa.org/mental-health-program

- Waldram JB, Herring A, Young TK. Health and disease prior to European contact. In: Waldram J, Herring A, and Young T, editors. Aboriginal health in Canada: historical, cultural, and epidemiological perspectives. Toronto: University of Toronto Press; 2006. p. 24–47.

- Karetak J, Tester F, Tagalik S. Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit: what inuit have always known to be true. Winnipeg: Fernwood Publishing; 2017.

- Karetak JN. Lives in Arviat. Oral teaching to the Qanuinngitsiarutiksait team; 2022.

- Anang P, Gottlieb N, Putulik S, et al. Learning to fail better: reflections on the challenges and risks of community-based participatory mental health research with Inuit Youth in Nunavut. Community case study. Front Public Health. 2021 Mar 12;9. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2021.604668

- Kumar M, Tjepkema M. Suicide among first nations people, Métis and Inuit (2011-2016): findings from the 2011 Canadian Census Health and Environment Cohort (CanCHEC). Statistics Canada; [cited 2023 Jul 27]. Available from: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/99-011-x/99-011-x2019001-eng.htm

- Stack S, Cao L. Social Integration and Indigenous Suicidality. Arch Suicide Res. 2020;24(sup1):86–101. doi: 10.1080/13811118.2019.1572556

- Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami. National inuit suicide prevention strategy. [cited 2023 Jul 27]. Available from: https://www.itk.ca/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/ITK-National-Inuit-Suicide-Prevention-Strategy-2016.pdf

- Smylie J, Firestone M, Spiller MW, et al. Our health counts: population-based measures of urban Inuit health determinants, health status, and health care access. Can J Public Health. 2018 Dec;109(5–6):662–670. doi: 10.17269/s41997-018-0111-0

- Pollock NJ, Naicker K, Loro A, et al. Global incidence of suicide among Indigenous peoples: a systematic review. BMC Med. 2018 Aug 20;16(1):145. doi: 10.1186/s12916-018-1115-6

- Kral MJ. Suicide and suicide prevention among Inuit in Canada. Can J Psychiatry. 2016 Nov;61(11):688–695. doi: 10.1177/0706743716661329

- Morris M, Crooks C. Structural and cultural factors in suicide prevention: the contrast between mainstream and Inuit approaches to understanding and preventing suicide. J Soc Work Pract. 2015;29(3):321–338. doi: 10.1080/02650533.2015.1050655

- Poliakova N, Riva M, Fletcher C, et al. Sociocultural factors in relation to mental health within the Inuit population of Nunavik. Can J Public Health = Revue Canadienne de Sante Publique. 2022 Nov 7;115(S1):83–95. doi: 10.17269/s41997-022-00705-w

- Kral MJ. “The weight on our shoulders is too much, and we are falling”: Suicide among Inuit male youth in Nunavut, Canada. Med Anthropol Q. 2013 Mar;27(1):63–83. doi: 10.1111/maq.12016

- Haggarty JM, Cernovsky Z, Bedard M, et al. Suicidality in a sample of Arctic households. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2008 Dec;38(6):699–707. doi: 10.1521/suli.2008.38.6.699

- Beaudoin V, Séguin M, Chawky N, et al. Protective factors in the inuit population of nunavut: a comparative study of people who died by suicide, people who attempted suicide, and people who never attempted suicide. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018 Jan 16;15(1):144. doi: 10.3390/ijerph15010144

- Crooks CV, Exner-Cortens D, Burm S, et al. Two years of relationship-focused mentoring for first nations, Métis, and inuit adolescents: promoting positive mental health. J Prim Prev. 2017 Apr;38(1–2):87–104. doi: 10.1007/s10935-016-0457-0

- Phinney JS. Stages of ethnic identity development in minority group adolescents. The J Early Adolescence. 1989;9(1–2):34–49. doi: 10.1177/0272431689091004

- Newell SL, Dion ML, Doubleday NC. Cultural continuity and Inuit health in Arctic Canada. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2020 Jan;74(1):64–70. doi: 10.1136/jech-2018-211856

- Gray AP, Richer F, Harper S. Individual- and community-level determinants of Inuit youth mental wellness. Can J Public Health. 2016 Oct 20;107(3):e251–e257. doi: 10.17269/cjph.107.5342

- Silversides A. Inuit health system must move past suicide prevention to “unlock a better reality,” conference told. CMAJ. 2010 Jan 12;182(1):E46. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.109-3117

- Tuck E. Suspending damage: a letter to communities. Harvard Educ Rev. 2009;79(3):409–427. doi: 10.17763/haer.79.3.n0016675661t3n15

- Durkalec A, Furgal C, Skinner MW, et al. Climate change influences on environment as a determinant of Indigenous health: Relationships to place, sea ice, and health in an Inuit community. Soc Sci Med. 2015 Jul;136-137:17–26. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.04.026

- Cunsolo A, Harper S, Edge V, et al. The land enriches the soul: on climatic and environmental change, affect, and emotional health and well-being in Rigolet, Nunatsiavut, Canada. Emotion Space Soc. 2013 Feb 01;6:14–24. doi: 10.1016/j.emospa.2011.08.005

- Bourque F, Cunsolo Willox A. Climate change: The next challenge for public mental health? Int Rev Psychiatry. 2014 Aug 01;26(4):415–422. doi: 10.3109/09540261.2014.925851

- Cunsolo Willox A, Harper SL, Ford JD, et al. Climate change and mental health: an exploratory case study from Rigolet, Nunatsiavut, Canada. Climatic Change. 2013 Nov 01;121(2):255–270. doi: 10.1007/s10584-013-0875-4

- Toor J, Evaluardjuk-Palmer T, Lavoie J. No land, no health: exploration of the impact of historical environment on inuit qanuinngitsiarutiksait in the context of climate change. Arctic Yearbook. 1–22. https://arcticyearbook.com/images/yearbook/2023/Scholarly_Papers/2_Toor_AY2023.pdf

- Hulme M. The conquering of climate: discourses of fear and their dissolution. Geographical J. 2008;174(1):5–16. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-4959.2008.00266.x

- Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. Truth and reconciliation commission of Canada: calls to action. [cited 2023 Jul 27]. Available from: https://www2.gov.bc.ca/assets/gov/british-columbians-our-governments/indigenous-people/aboriginal-peoples-documents/calls_to_action_english2.pdf

- Government of Canada. Canada health act. [cited 2023 Jul 27]. Available from: https://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/PDF/C-6.pdf

- European Center for Constitutional and Human Rights. UN declaration on the rights of indigenous peoples. [cited 2023 Mar 28]. Available from: https://www.ecchr.eu/en/glossary/un-declaration-on-the-rights-of-indigenous-peoples/#:~:text=The%20declaration%20acknowledges%20indigenous%20peoples,stolen%20lands%2C%20territories%20and%20resources

- United Nations. The United Nations convention on the rights of the child. [cited 2023 Jul 27]. Available from: https://www.unicef.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2010/05/UNCRC_united_nations_convention_on_the_rights_of_the_child.pdf

- Porterfield DS, Hinnant LW, Kane H, et al. Linkages between clinical practices and community organizations for prevention: a literature review and environmental scan. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(S3):S375–S382. doi: 10.2105/ajph.2012.300692

- Charlton P, Doucet S, Azar R, et al. The use of the environmental scan in health services delivery research: a scoping review protocol. BMJ Open. 2019;9(9):e029805. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-029805

- Rowel R, Moore ND, Nowrojee S, et al. The utility of the environmental scan for public health practice: lessons from an urban program to increase cancer screening. J Natl Med Assoc. 2005 Apr;97(4):527–534.

- Charlton P, Kean T, Liu RH, et al. Use of environmental scans in health services delivery research: a scoping review. BMJ Open. 2021;11(11):e050284. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2021-050284

- Putt J. Conducting research with Indigenous people and communities. Indigenous Justice Clearinghouse; 2013. https://www.indigenousjustice.gov.au/wp-content/uploads/mp/files/publications/files/brief015.v1.pdf

- Chino M, DeBruyn L. Building true capacity: Indigenous models for indigenous communities. Am J Public Health. 2006;96(4):596–599. doi: 10.2105/ajph.2004.053801

- Petrasek MacDonald J, Cunsolo Willox A, Ford JD, et al. Protective factors for mental health and well-being in a changing climate: perspectives from Inuit youth in Nunatsiavut, Labrador. Soc Sciamp Med. 2015 Sep 01;141:133–141. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.07.017

- Brady M. Culture in treatment, culture as treatment. A critical appraisal of developments in addictions programs for indigenous North Americans and Australians. Soc Sciamp Med. 1995 Dec 01;41(11):1487–1498. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(95)00055-C

- Tunngasugit. About Tunngasugit. [cited 2023 Apr 5]. Available from: https://www.tunngasugit.ca/about/about-tunngasugit/

- Lesperance A, Kendrick CT, Flicker S. ‘This is what’s going to heal our kids’: bringing the sexy health carnival into Indigenous cultural gatherings. Cult Health Sex. 2022 Oct 22:1–16. doi: 10.1080/13691058.2022.2105402

- Aqqiumavvik. The Programs. [cited 2023 Apr 5]. Available from: https://www.aqqiumavvik.com/

- Rasmus SM, Allen J, Ford T. “Where I have to learn the ways how to live:” youth resilience in a Yup’ik village in Alaska. Transcult Psychiatry. 2014 Oct;51(5):713–734. doi: 10.1177/1363461514532512

- Mohatt GV, Fok CC, Henry D, et al. Feasibility of a community intervention for the prevention of suicide and alcohol abuse with Yup’ik Alaska Native youth: the Elluam Tungiinun and Yupiucimta Asvairtuumallerkaa studies. Am J Community Psychol. 2014 Sep;54(1–2):153–169. doi: 10.1007/s10464-014-9646-2

- Rasmus SM, Charles B, Mohatt GV. Creating Qungasvik (A Yup’ik Intervention “Toolbox”): Case examples from a community-developed and culturally-driven intervention. Am J Of Comm Psychol. 2014;54(1–2):140–152. doi: 10.1007/s10464-014-9651-5

- Allen J, Mohatt GV, Beehler S, et al. People awakening: collaborative research to develop cultural strategies for prevention in community intervention. Am J Community Psychol. 2014 Sep;54(1–2):100–111. doi: 10.1007/s10464-014-9647-1

- Allen J, Mohatt GV. Introduction to ecological description of a community intervention: building prevention through collaborative field based research. Am J Community Psychol. 2014 Sep;54(1–2):83–90. doi: 10.1007/s10464-014-9644-4

- Rasmus SM. Indigenizing CBPR: evaluation of a community-based and participatory research process implementation of the Elluam Tungiinun (towards wellness) program in Alaska. Am J Community Psychol. 2014 Sep;54(1–2):170–179. doi: 10.1007/s10464-014-9653-3

- Tungasuvvingat Inuit. About Tungasuvvingat Inuit. [cited 2023 Apr 5]. Available from: https://tiontario.ca/about-ti

- Aboriginal Health and Wellness Centre of Winnipeg. About aboriginal health and wellness centre of winnipeg. [cited 2023 Apr 5]. Available from: https://ahwc.ca/about-ahwc/

- Nimkee Nupigawagan Healing Centre. Goals of the Nimkee NupiGawagan Healing Centre. [cited 2023 Apr 6]. Available from: https://nimkee.org/programs/

- BluePrintForLife. About BluePrintForLife. [cited 2023 Apr 6]. Available from: https://www.blueprintforlife.ca/about/

- Embrace Life Council. What we do. [cited 2023 Apr 5]. Available from: Inuusiq.com/

- Pulaarvik. Our Programs. [cited 2023 Apr 5]. Available from: https://www.pulaarvik.ca/our-programs

- Qaujigiartiit Health Research Centre. Programs. [cited 2023 Apr 5]. Available from: https://www.qhrc.ca/inuusirvik/

- Ilisaqsivik. Health and Wellness Centre. [cited 2023 Apr 5]. Available from: https://ilisaqsivik.ca/en/

- Project Creates. Key Findings. [cited 2023 Apr 6]. Available from: https://www.projectcreates.com/workshops-key-findings

- Inuvialuit Regional Corporation. Mental wellness: brighter futures. [cited 2023 Apr 6]. Available from: https://irc.inuvialuit.com/program/mental-wellness-brighter-futures

- Camp Eclipse. What is camp eclipse? [cited 2023 Apr 6]. Available from: https://www.campeclipse.com/about.html

- Anang P, Naujaat Elder EH, Gordon E, et al. Building on strengths in Naujaat: the process of engaging Inuit youth in suicide prevention. Int J Circumpolar Health. 2019 Jan-Dec;78(2):1508321. doi: 10.1080/22423982.2018.1508321

- Joliet F, Chanteloup L, Herrmann T. Adolescence and identity in Inuit territory: filmed introspections. Arct Spaces And Socities. 2021. doi: 10.4000/eps.10986

- Lemaire A, Sokoloff M, Fraser S, et al. Dans le Black Box d’Igloolik : le cirque comme espace thérapeutique pour de jeunes Inuit? Études/inuit/studies. 2016;40(1):43–62. doi: 10.7202/1040144ar

- Healey GK, Noah J, Mearns C. The Eight Ujarait (Rocks) model: supporting inuit adolescent mental health with an intervention model based on inuit ways of knowing. Int J Indigenous Health. 2016;11(1):92–110. doi: 10.18357/ijih111201614394

- Ljubicic GJ, Mearns R, Okpakok S, et al. Nunami iliharniq (Learning from the land): reflecting on relational accountability in land-based learning and cross-cultural research in Uqšuqtuuq (Gjoa Haven, Nunavut). Arct Sci. 2022;8(1):252–291. doi: 10.1139/as-2020-0059

- Pace J, Gabel C. Using photovoice to understand barriers and enablers to southern labrador Inuit intergenerational interaction. J Intergenerational Relat. 2018 Oct 02;16(4):351–373. doi: 10.1080/15350770.2018.1500506

- Hirsch R, Furgal C, Hackett C, et al. Going off, growing strong: a program to enhance individual youth and community resilience in the face of change in Nain, Nunatsiavut. Études/inuit/studies. 2016;40(1):63–84. doi: 10.7202/1040145ar

- Spaces and Places. About Spaces and Places. [cited 2023 Apr 11]. Available from: http://youthspacesandplaces.org/

- Fletcher C, Riva M, Lyonnais M-C, et al. Epistemic inclusion in the Qanuilirpitaa? Nunavik Inuit health survey: developing an Inuit model and determinants of health and well-being. Can J Public Health. 2022 Dec 22;115(S1):20–30. doi: 10.17269/s41997-022-00719-4

- Liebenberg L, Wall D, Wood M, et al. Spaces & places: understanding sense of belonging and cultural engagement among Indigenous Youth. Int J Qualitative Methods. 2019;18:1609406919840547. doi: 10.1177/1609406919840547

- Project Creates. PROJECT CREATES: circumpolar resilience, engagement, and action through story. [cited 2023 Jul 27]. Available from: https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5ccb4b69840b16fcba32fd2d/t/5d0a9d7cbc8cbc0001f45cf3/1560976772833/Project-CREATeS-final-report-March-22-2019.pdf

- Mental Health Comission of Canada. Advancing the mental health strategy for Canada: a framework for action (2017–2022). Mental Health Commission of Canada. Available from: https://www.mentalhealthcommission.ca/wp-content/uploads/drupal/2016-08/advancing_the_mental_health_strategy_for_canada_a_framework_for_action.pdf

- Hackett C, Furgal C, Angnatok D, et al. Going off, growing strong: building resilience of Indigenous Youth. Can J Community Ment Health. 2016;35(2):79–82. doi: 10.7870/cjcmh-2016-028

- Saini M, Roche S, Papadopoulos A, et al. Promoting Inuit health through a participatory whiteboard video. Can J Public Health. 2020 Feb;111(1):50–59. doi: 10.17269/s41997-019-00189-1

- Hadjipavlou G, Varcoe C, Tu D, et al. “All my relations”: experiences and perceptions of Indigenous patients connecting with Indigenous Elders in an inner city primary care partnership for mental health and well-being. CMAJ. 2018 May 22;190(20):E608–e615. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.171390

- Friends for Life. Children. [cited 2023 18]. Available from: https://friendsresilience.org/friendsforlife

- Miller LD, Laye-Gindhu A, Bennett JL, et al. An effectiveness study of a culturally enriched school-based CBT anxiety prevention program. J Clin Child & Adolesc Phychol. 2011 July 01;40(4):618–629. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2011.581619

- Owais S, Tsai Z, Hill T, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis: first nations, Inuit, and Métis youth mental health. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2022 Oct;61(10):1227–1250. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2022.03.029

- Fraser SL, Geoffroy D, Chachamovich E, et al. Changing rates of suicide ideation and attempts among Inuit youth: a gender-based analysis of risk and protective factors. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2015 Apr;45(2):141–156. doi: 10.1111/sltb.12122

- Native Youth Sexual Health Network. What we do. [cited 2023 Apr 6]. Available from: https://www.nativeyouthsexualhealth.com/what-we-do

- Dell CA, Chalmers D, Bresette N, et al. A healing space: the experiences of first nations and Inuit youth with equine-assisted learning (EAL). Child Youth Care Forum. 2011;40(4):319–336. doi: 10.1007/s10566-011-9140-z

- Artcirq. Our missions and goals. [cited 2023 Apr 12]. Available from: https://www.artcirq.org/en/memoriam

- Mearns C, Healey GK. Makimautiksat youth camp: program evaluation 2010-2015. Qaujigiartiit Health Research Centre; 2015. https://web.archive.org/web/20170825182648/http://www.qhrc.ca/sites/default/files/makimautiksat_evaluation_2010-2015_-_feb_2015.pdf

- Robinson M. Two-spirit identity in a time of gender fluidity. J Homosex. 2020 Oct 14;67(12):1675–1690. doi: 10.1080/00918369.2019.1613853

- Affleck W, Oliffe JL, Inukpuk MM, et al. Suicide amongst young inuit males: the perspectives of Inuit health and wellness workers in Nunavik. SSM - Qualitative Res In Health. Dec 2022 01;2:100069. doi: 10.1016/j.ssmqr.2022.100069