ABSTRACT

There is high prevalence of the genetic SI variant c.273_274delAG in the sucrase-isomaltase-encoding gene in Greenland, resulting in congenital sucrase-isomaltase deficiency and thereby an inability to digest sucrose, the most common dietary sugar. There are no studies of Greenlanders’ everyday experiences of sucrose intolerance related to this genetic variant. This study therefore explored, how Greenlandic people experience sucrose intolerance influences life and their attitudes towards research in health and genetics. The study is qualitative, using semi-structured focus groups and/or individual telephone interviews. The analysis was based on the phenomenological-hermeneutic approach of Paul Ricoeur, consisting naïve reading, structural analysis, interpretation and discussion. We identified two themes; “Sucrose intolerance impacts daily living”, dealt with physical and emotional reactions and coping with social adaption to activities. And “openness to participate in genetic and health research” were caused by participants wanting more knowledge to improve their people and family’s life. The study concluded that most of the participants with symptoms of sucrose intolerance experienced the impact in their daily life, both physically, emotionally, and socially. Further, they expressed openness to participate in health and genetic research. There is a need for more accessible health knowledge and support from health care to manage sucrose intolerance.

Introduction and background

The genetic variant c.273_274delAG in the sucrase-isomaltase-encoding gene SI has a high prevalence in Greenland [Citation1]. The variant results in a lack of enzymatic activity making homozygous carriers unable to digest and absorb sucrose, the most common dietary sugar in the intestine [Citation2]. We refer to this condition as sucrose intolerance in this paper. Some people living with this genetic variant are found to have everyday challenges, when eating foods containing sucrose, including physical problems such as gastrointestinal pain [Citation2–5]. The intake of imported Western food has increased in Greenland during recent decades; this contains high amounts of carbohydrates and sucrose resulting in the mentioned symptoms of the homozygous carriers, unlike the traditional Arctic foods high in protein and fat, which likely did not cause any symptoms [Citation6,Citation7]. Today, the intake of food containing sucrose is generally high in Greenland [Citation8]. However, the impact of the unique genetic variant in adults is assumed to be unknown in the Arctic population [Citation1] The allele frequency of this variant is very low around the globe, except from in the Arctic, where the frequency has been estimated to 3–20% in Arctic Inuit, and 14.2% in Greenland, with 2.1% of the population being homozygous carriers. In the Inuit ancestry population of Greenland, the prevalence is 20% [Citation1,Citation5]. The sucrase-isomaltase variant has been associated with metabolic health in adult homozygous carriers, including lower BMI, better lipid profile, and reduced risk of cardiovascular disease [Citation1,Citation9]. Meanwhile, individuals with congenital sucrase-isomaltase deficiency experience gastrointestinal problems including diarrhoea and pain when eating sucrose, i.e. symptoms similar to irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) [Citation10]. This is most likely explaining, why Greenlandic homozygous SI carriers have more gastrointestinal-related health-care contacts and diagnostic procedures compared to other individuals in Greenland [Citation1,Citation3,Citation4,Citation10]. Further, international research has identified that of people with IBS, sucrose intolerance was present in 35% of patients, and 64% had diarrhoea, and 45% had abdominal pain [Citation10]. This result might indicate that some Greenlanders having the sucrase-isomaltase variant become misdiagnosed with IBS [Citation10,Citation11].

Although it is likely that carriers of the variant have gastrointestinal symptoms and pain affecting their lives when they eat foods containing sucrose, there are no studies of how Greenlander’s experience sucrose intolerance themselves. However, knowledge of the effects of the variant is very relevant today as the intake of carbohydrates and sucrose is increasing in Greenland [Citation5,Citation8]. This user study therefore investigated; how Greenlandic people experience sucrose intolerance influences their life. The study also explored attitudes towards research in health and genetics. The results will inform a larger study with knowledge of factors that may influence the feasibility of a planned study on metabolic effects of two short-term dietary interventions (traditional vs. Western diet) in carriers and non-carriers of the genetic variant [Citation5,Citation12].

Study design and methods

Methodologically, this qualitative interview study is inspired by the French philosopher Paul Ricoeur’s phenomenological-hermeneutical approach [Citation13–16] to explore Greenlanders’ experiences of sucrose intolerance and attitudes to genetic health research. We planned to use focus group interviews, as this method offers the participants an opportunity of discussing their life experiences with each other [Citation17]. However, because of the COVID-19 pandemic, we had to be flexible in collecting the data, and we both did semi-structured focus group interviews, individual semi-structured interviews, and individual telephone interviews to investigate the topics [Citation17,Citation18].

Participants

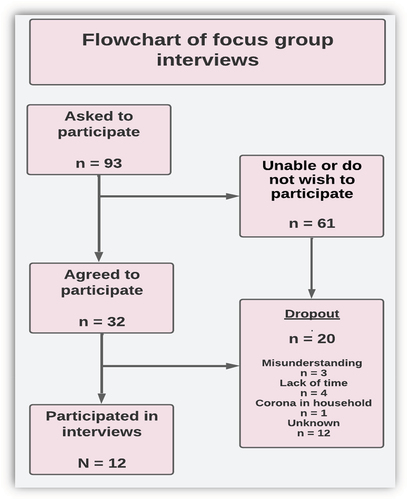

A number of 93 carriers and non-carriers of the SI variant, who had participated in public health surveys, were invited to participate by telephone. Of these, 32 participants agreed to be interviewed in focus groups or by phone. However, due to the pandemic situation, we had to conduct individual online or phone interviews and online focus group interviews. This circumstance resulted in further 20 dropouts, of which 12 did not explain why they did not participate [Citation19]. The focus group interviews were supplemented by five telephone interviews (see ). The interviewers of the focus group interview were blinded as to which participants were carriers of the genetic variant, while all the telephone interviews were with carriers.

Data collection

The interviews were performed during 2021–22. On the day of the interview, the participants received a reminder as a phone text message and if possible, an email along with the Zoom link for the interview. One participant went to an agreed place for her interview and borrowed a laptop. The interviews were facilitated by the first and last author, using a semi-structured interview guide. presents the research questions with examples of interview questions [Citation18].

Table 1. Examples of research and interview questions from the interview guide.

During the interviews, the participants were given additional information such as: “Food with sugar can be soda, yogurt, cereals, certain fruits and cakes” or “some people describe symptoms such as pain in the stomach or diarrhea, have you experienced that?” We used the term sugar instead of sucrose, to strengthen the general linguistic understanding to the participants. The interviews started with a repetition of the aim of the study. The researchers worked in Greenland and Denmark and the primary interviewer spoke both Greenlandic and Danish. The interviews were conducted in the participants’ preferred language, while telephone interviews were conducted in Danish by two research assistants. The interviews were audiotaped, transcribed, and stored according to ethical guidelines [Citation14].

Ethics

The Ethics Committee for Scientific Research in Greenland approved the study (KVUG 2021–21). The study adhered to the Helsinki Declaration [Citation20]. Besides the time the participants spent, participation was not viewed as harmful [Citation21,Citation22]. The participants gave their informed consent after being informed of their right to withdraw from the study.

Data analysis

The phenomenological-hermeneutic approach inspired the analysing process consisting of: Naïve reading, structural analysis, interpretation, and discussion [Citation13,Citation23]. The first and last authors did the naïve reading and identified a holistic view of the results. Then a structural analysis was performed by the research team focusing on “what is said” (units of meaning) and “what the text speaks about” (units of significance) [Citation23]. Along with the research questions, this analysis generated the themes. Finally, the findings, including the significant meanings of the quotes and themes, were discussed with all the authors (). The qualitative software program NVivo was used to structure the analysis, resulting in a coding book including all quotes and themes [Citation24,Citation25].

Results

Twelve persons participated in the study, of which 10 were homozygous carriers of the Arctic SI variant. Seven were men (58%) and five women (42%) and median age was 55 years (range 44 to 60) (). Four of the participants had co-morbidity besides symptoms of sucrose intolerance. Most of the participants had a vocational education, education ranged between none to master’s degree. The participants lived in six different towns in Greenland.

Table 2. Demographic characteristics of participants (N = 12).

The structural analysis of the data identified two main themes, including units of significance (sub-themes). The first theme “Effects of sucrose intolerance” presents its impact on people’s daily lives. The second “Opinions on participation in health research” identified the participants openness to participate in genetic and health research. In the following sections, the themes will be described and analysed with the inclusion of perspectives from the units of significance (see ).

Table 3. Examples from the structured analysis including themes 1 and 2.

Sucrose intolerance impacts daily living

The first theme identified the impact that sucrose intolerance can have on Greenlanders’ lives in areas, such as physical symptoms, emotional perspectives, and social adaptation ().

Physical symptoms

The bodily impact of sucrose intolerance was identified through physical symptoms influencing the participants’ everyday lives. The participants reported that the most common symptoms were flatulence or bloating, stomach ache, diarrhoea, and fatigue. The symptoms varied depending on intake; some just felt bloated and experienced flatulence if they ate a small amount of sugar (P9W, P11M), but the same participants had diarrhoea and nausea when they ate large amounts of sugar. P7W said that she did not develop symptoms when she ate strawberries, but when she ate chocolate, she felt discomfort. Other participants described how they could eat chocolate without problems, but they did have problems when eating cakes (P11M). One of the women explained: “I get a bloated stomach and I get very thirsty. Then, I become tired and sleepy. I have also noticed that I get bad skin” (P4W).

Several participants reported being aware that they had symptoms similar to sucrose intolerance, while others replied that they had no symptoms, but when asked about their daily living, some of them did talk about physical reactions like symptoms of sucrose intolerance or stated that they would avoid eating sugar. The experiences of sucrose intolerance symptoms varied. Some only experienced a few symptoms, mostly reporting gastrointestinal challenges, while one participant described how his whole body was affected, including bad skin, thirst, sleepiness, and pain (P6M).

The physical symptoms were described from a lifespan perspective; often they had experienced physical symptoms since childhood. One stated: “I have not been able to tolerate sugar since I was born” (P4W). Another confirmed this: “I remember having stronger symptoms when I was a kid. When I was in the transition to my teens, I found that I got diarrhoea more often, when I had eaten sugar at that time … ” (P7W). P9W said: “My father, big brother, and my aunt´s daughter had symptoms very similar to mine and five other brothers and sisters have no symptoms”. These lifespan stories showed that many participants who had developed symptoms or intolerance in their childhood were not necessarily aware that their physical symptoms were due to sucrose intolerance. This was a family phenomenon and therefore considered normal in childhood. Some of the participants reported that when they grew up, some of them had fewer symptoms, presumably because they had adapted to food or sucrose restrictions. One of the participants, however, developed symptoms of sugar intolerance in his thirties (P11M). Although one participant did not know of family members with symptoms (P10M), the genetic aspect of sucrose intolerance was identified through several stories about sugar intolerance that ran in the family.

Some of the participants had even become so familiar with their condition that they knew when to be home or close to a restroom after eating sugar, identifying a time factor of 45 minutes to 2 hours before physical symptoms arose. One said: “Sometimes when I need something, such as a small candy, I calculate that I need to be home in 45 minutes … When I only eat one sugar cube, I can have diarrhoea for many hours” (P3W). P4W said: “Yes, when I really want to taste something sweet, I must be home in one to two hours”. Symptoms of sugar intolerance often appeared in a short time but could continue for many hours, affecting the participants’ everyday life. Thus, sugar intolerance affected the physical health and well-being of most of those with the condition, while the strength of their symptoms varied.

Emotional perspectives

Sugar intolerance had a great impact on emotional life, including worries, anxiety, and a need to feel secure, thus identifying the impact on mental health of carriers of the genetic variant. One participant connected the symptoms to her worries about her health, saying, “I get a stomach ache and have a lot of diarrhoeas … I feel a lot from eating chocolate, I get the most discomfort from it … I’m sometimes worried about the way I’m in pain” (P7W). Another explained: “When you’re allergic to sugar, when you’ve had diarrhoea for a long time, then you think a lot about your health” (P4W). The participants worried about the possible consequences of their food and sugar intake, such as whether they could lead to cancer or otherwise affect their body.

Some participants needed to feel secure; one said that she would return to her home if she got symptoms because it was the safest place for her to be: “When I think back, I sometimes think of when I was a young teenager … I was very reluctant to take part in, for example, sports and youth clubs, or when I had a boyfriend. I was very shy and reluctant if I had a slight upset stomach. It affected my way of being with other people … ” (P4W). Another described the impacts of the pain caused by sweet bread on her feeling of insecurity if she was away from home, travelling or having dinner with friends (P7W).

Although one of the participants (probably a non-carrier) did not experience symptoms herself, she reflected in general terms on the emotional challenges of having a taboo health issue like sugar intolerance and the need to be more open about illness in general:

“I know that if you talk about it, then it’s easier for you afterwards. It always is … We Greenlanders only discover it when a person is gone. At first, you’re sad and then you can … Just when it’s too late, then you can talk about it. I think it’s good to talk about it now. Suddenly, we’ll all be gone at some point. Greenlanders are very spoiled people, but still, when it comes down to where it hurts, then you don’t talk about it. At least that is what I think … That’s my experience. You must be more open about it”. (P1W)

This point of view that Greenlanders could benefit from sharing their feelings and emotions was repeated in several of the interviews; participants thought that it would be very useful to share positive or negative experiences, it would make them feel better, and they could learn from each other about sucrose intolerance.

Coping

Coping by social adaptation was associated with different ways of participating in social activities, contact with health care providers, and coping with sucrose intolerance. Some of the participants showed positive coping resources by adapting to the circumstances in their social life. Still, symptoms of sucrose intolerance affected socialising in different ways. One participant thought that sugar did not affect her but described how she would cope by adapting her intake of sugar to the circumstances: “I can eat anything if it’s small pieces in the weekend or on days off. When I need sugar, I eat it on Fridays. I don’t go out then” (P3W). Another mentioned that if she had trouble with her stomach, she would stay at home: “When I feel this, it’s safer to be home … ” (P4W). Others found it difficult to travel, because of the risk of sucrose intolerance symptoms: “For example, when I’m going to a course, when the food is different from what I’m used to, it can be uncomfortable. I often have pain there, as my digestion works in a slightly different way” (P7W). For P4W, the symptoms had also affected her socialising with other people when she was younger. She said:

My dad and I sit on the toilet every Christmas and when we have a coffee party. I thought it was everyone who felt that way … . I could not understand why, for example as a young girl, when all my classmates drank Kondi [soda] or Cola. When I did, I always got a bloated stomach, and I used a lot of force to stop going to the toilet. (P4W)

Several described having challenges with coffee parties (in Greenlandic “kaffemik”). Kaffemik is a tradition where Greenlanders celebrate birthdays and other events with a great deal of social activity and various cakes, sweets, and other foods. Although the coffee parties could cause physical problems, the participants would still attend, as the kaffemik was important to them for a sense of social inclusion [Citation26].

Coping with health care system dealt with the participants’ contact with the health care system, such as participating in health research or seeing a doctor. One described her experiences:

I might just mention that by participating in another study, I found out that I had elevated cholesterol … Also, the other thing, going to the doctor because you are in pain or something else. Because they [doctors] don’t come to town that often. That’s why many people are diagnosed too late. (P7W)

This participant appreciated having the opportunity to be involved in research, because then she could find out about her diseases and were treated in time. Another participant reported having asked her doctor to investigate her sucrose intolerance problems: “I did make an appointment with the doctor, but he did not explain anything to me” (P3W).

The participants had different coping strategies. Some of the participants with symptoms ate very little or no sugar when they were in social activities. One said, “I get diarrhoea more often when I drink soda. That’s why I keep off soda and sugar” (P6M).

P4W and her family (who also had sucrose intolerance problems) coped by simply helping each other. She said: “When we are at family gatherings or coffee parties and sit together at a table, we (for example, my father, my cousin, and I) might taste a cake, and when we put it in our mouth, we can just say … like we simply understand each other” (P4W). P4W’s family knew about sucrose intolerance:

Now I feel like I can live with it, now I know when I shouldn’t have eaten it and … and fortunately most of my family also now know what we can’t eat … I’ve also started doing that, when I bake, so it’s dates or Sukrin I use to bake pastry. We also help each other, for example if we have a kaffemik, we always ask if we can make a gluten-free, sugar-free, and lactose-free cake … (P4W)

Others found sucrose intolerance more difficult to cope with. P7W had difficulties in self-managing the condition, while P4W, as seen above, felt that she could live with it, maybe because her closest family members would support each other, since several of them had the same problems. P3W would cope by not eating sugar: “When I have to invite people or go somewhere else (…), I stay away from sugar, then I don’t have the problem”. Overall, the participants would join social events such as a kaffemik and adapt to them, and they seemed to participate in these social activities despite suffering from the physical problems of sucrose intolerance afterwards.

Openness to participate in genetic – and health research

This theme revealed participants’ openness to be involved in genetic research about food, and common attitudes towards participating in research in general ().

Participation in genetic research about food

The participants showed openness to participate in genetic research about food, due to a desire to feel understood by the health care system and a need for more visible research for the public, including applying a family approach.

Most wished that more Greenlanders would be open and take part in genetic research in general, including participating in this specific genetic research about food to help both themselves and others to enhance their health (P1W, P2M, P3W, P4W, P7M). One said:

“I don’t think it’s a problem (to participate in genetic research), it’s just a good thing that we can help other Greenlanders. I tried a few years ago where they had to examine some DNA. That was also good. I’m not much into healthy food, but you must try to be careful. I’m not worried … I’m all in”. (P2M)

Others were motivated by a need of being understood, or simply wanted health professionals and researchers to understand their health challenges: “I’m joining the study. I will be very grateful. I would like to feel understood by others because I am sometimes worried … ” (P7W). Subsequently, she added that the infrastructure could make it difficult for her to attend in research, but she also felt that technology would probably remove that obstacle.

The participants found that there was only little research visible to the public, including studies of sucrose-intolerance, and they described “a need to reveal the possibilities” such as providing knowledge about illness: “To me, it is like finding ten names and pulling out five of them. You could advertise a little more in the weekly newspaper, for example … or on Facebook [about the possibility of being included in the research]. It is very closed, your study. No one knows anything about it. I’ve read a bit about it, but I would like to get it out in the open for Greenland” (P2M). P3W and P7W shared similar concerns about research being more open and available to the public.

The participants stated that the health care system was responsible for providing knowledge about research. P2M, P4W and P7W requested public availability of research and communication in a lay language and P4W added:

“I am very interested in it; I think it’s good that someone is finally doing research about it, because there has been a lot of talk about it for many years that Greenlanders, i.e., Inuit people, are allergic to many things”. (P4W)

Several highlighted the importance of a family-based approach in genetic research: P4W also expressed her concerns about physical consequences of sucrose intolerance such as malnutrition caused by food allergies, and she worried about possible reactions to food if families do not know about their sucrose intolerances. One participant provided an example of someone with symptoms of sucrose intolerance, where health professionals had talked about it, which did help the family to realise the problem: “If there could be more information about it, then Greenlanders could find out about it … Different people have the same problem, I think” (P3W).

Common attitudes about participation in research

The participants all felt that the Greenlandic people as such needed more knowledge. One was surprised of the poor knowledge of sucrose intolerance and diabetes in the general population. She herself found information on the Internet or television and expected the availability and need of health-related knowledge to develop rapidly in the future (P1W). Another (P7W) believed that the need for knowledge of sucrose intolerance would increase in the future, because young Greenlanders are more likely to search for knowledge. Some participants (P4W, P5M, P6M and P7W) hoped that Greenlanders would be open to participating in research in general to gain knowledge; one said: “I hope the population will receive it well, to feel safe … secure about things like that” (P6M).

Another stressed that there are many areas of health that have not been studied, such as the impact of the intake of Western food:

“I believe that we as a people stand out from others in terms of food intake. We still lack knowledge about what food can do to our bodies, as far as eating Greenlandic or Western food is concerned”. (P7W)

The analyses identified a general need of more openness about disease or illness: “There are not that many of us Greenlanders anyway. I think it’s a shame you’re not more open about it” (P2M). However, several participants (P5M, P6M and P7W) also mentioned difficulties in talking about their disease, especially when the conditions were invisible: “You don’t talk about it that much, I think. It’s not so visible, I mean the disease” (P6M). Most participants were of the opinion, that Greenlanders generally do not easily share their knowledge about diseases and food intolerance (P1W, P2M, P3W, P4W and P7W), and called for more sharing of experiences and feelings: “I know that if you talk about it, then you get a load off your mind. It’s always like that” (P1W). P2M added that illness does not disappear because you are silent about it. Referring to another participant’s perspective, he stated: “ … What she says is also true. Greenland is very closed; they keep saying it’s far too expensive to do campaigns. But it isn’t, if just one person can get better” (P2M). The participants did unfold a need in society for more openness about how to cope with sucrose intolerance.

Discussion

We investigated Greenlanders’ experience of sucrose intolerance including how symptoms influenced their daily living, and attitudes towards participating in research in genetics and health. The findings confirmed that sucrose intolerance affected the participants' daily lives negatively, and that they found it difficult to receive support aimed at their condition. The findings also showed that health knowledge plays an important role and motivates Greenlanders to take part in genetic and health research. This will be discussed in the following sections.

The impact of sucrose intolerance on health and daily living

The participants found that sucrose intolerance had a considerable impact on their daily living and health, primarily in terms of physical symptoms; however, it also influenced their mental health and social life.

The physical symptoms appeared shortly after intake of food containing sucrose, lasting mostly for a couple of days. The symptoms were mainly gastrointestinal symptoms, such as bloating, flatulence, diarrhoea, and nausea, often after eating only a small amount of sucrose. Similar results have been found in other studies, which have identified gastrointestinal problems, diarrhoea, and pain, cramping or bloating [Citation10] Some became very tired or had pain after intake of sucrose. Thus, the symptoms associated with sucrase-isomaltase were found to be similar to those of IBS [Citation10,Citation27]. Chey et al. (2020) identified that sucrase-isomaltase deficiency could affect children´s growth and result in weight loss in adulthood [Citation27]. We also found that some participants had strong symptoms in childhood, which is consistent with other studies finding that children may be more susceptible, and have more symptoms, because they have a shorter small intestine and reduced reserve capacity of the colon to absorb excess luminal fluid [Citation10,Citation27]. The genetic variant may influence Greenlandic children´s growth; hence, health care providers in Arctic countries should be aware, that children’s physical and mental health are at risk due to untreated sucrose intolerance, with the relatively high prevalence of the variant in Arctic populations [Citation27]. However, although the symptoms have a great impact on the carriers daily living, research has also identified that the genetic variant is associated with a healthier phenotype, as homozygous carriers in Greenland have a lower BMI and body fat % and a better lipid profile [Citation1]. Nevertheless, there is a lack of knowledge in research about what the long-term physical, emotional and social consequences of sucrose-intolerance are in the population. However, in current study we did observe that in the participants’ own perspective the sucrose intolerance affected them emotionally, with anxiety and a sense of insecurity having a negative impact on everyday life and social activity. The experienced gastrointestinal symptoms caused by the condition sometimes resulted in isolation and mental health problems. A study of IBS found that 47% had developed anxiety [Citation28], indicating a negative impact of gastrointestinal symptoms on quality of life, such as increased isolation [Citation27,Citation29]. Although these findings were related to IBS, our study indicated the importance of identifying people with the sucrase-isomaltase variant to improve their quality of life and well-being [Citation30,Citation31]. we therefore suggest that awareness of the condition/disease should be increased to achieve the correct diagnosis, proper advice, and health promoting support [Citation29,Citation32].

Need of support from the health care system and motivation for participating in research

The participants had great concerns about their possibilities of receiving support from the health care system. Some lived in towns without doctors, others felt that they did not get the help they needed, and finally some stated that after attempting contact with health care providers, they just gave up and tried to cope with sucrose intolerance in their own way. Previous studies of service user perspectives in Greenland have shown that the experiences of the health care system were closely linked to the quality of information and dialogue with health care providers [Citation33]. It is therefore a matter of great concern that some have stated that they could not do anything about their illness [Citation9].

In general, we observed that the participants were very open towards research, including genetic research, which supports previous findings of a sharing circle study among Greenlanders in Qasigiannguit [Citation34]. However, in the current study, some of the participants indicated that they would like to be involved in genetic research, because it gave them an opportunity to have a doctor’s perspective on their illness. With regards to genetic research in the arctic, including Greenland, this motivation of participating in research is a concern. It should therefore be emphasised to the participants what health information they will receive from participating in a research study, and what will be collected only for research purpose. Further, researchers should be aware the ethical perspective of whether an individual’s participation in research is motivated by a lack of support from the health care system.

Strengths and limitations

A strength of this study was that we were able to recruit participants across six towns in Greenland, not only in the capital, Nuuk. Meanwhile, it might be a limitation that all of them were former participants of the national survey and therefore they might not represent the general population as such. The greatest methodological challenge was the COVID-19 pandemic with restrictions and isolation, which resulted in a smaller number of participants than originally planned. Meanwhile, as Thirsk describes about qualitative research, the importance is the amount of new information gathered from a variety of sources to get at deeper understanding of the topic, and not the number of participants, which is less relevant in qualitative research and no valid assurance of rigour [Citation17]. We find it fair to argue that this study provided a rich amount of new knowledge about the participants personal experiences and reflections. A limitation regarding the sample was that there were three dropouts caused by the interviews being online, which might be due to the fact that not all Greenlanders have Internet access, which is very expensive in Greenland. Hence, the results may be skewed in that the sample potentially have included people of higher socio-economic status than non-participants [Citation27]. Furthermore, the participants expressed an interest in research knowledge and an interest to participate in genetic and health research, which might be caused by their experienced symptoms. It could have been interesting to compare the participants with those who did not participate to investigate potential participation bias, i.e. if participants had more symptoms than non-participants or to track their hospital contacts as other studies have done [Citation1,Citation4] this was outside the scope of this qualitative study and not possible due to the participants general rights of data protection [Citation35]. It could also be a limitation that all participants were selected from former national health survey, and therefore might have positive attitudes to participating in health research generally.

One participant’s whole family described symptoms related to the genetic variant, and all family members seemed to help each other. This family appeared to have high socio-economic status, and it would have been very interesting and important to be sure about including participants with lower economic or cultural capital, which may have yielded different results.

In Arctic health research, it could be important to consider that participation may also be affected by the weather and how to cope with that. In current study, a storm impacted the electricity supply in Nuuk and the Internet in the whole country delayed a focus group interview for 2 days resulting in at least two participants dropping out after the storm. Unfortunately, none of the other dropouts explained why they did not attend the interview [Citation36,Citation37].

When using semi-structured interviews, the interviewer can mix planned questions with topics that arise during the interview [Citation18] and it was an advantage to have the flexibility to pursue new topics that arose in the focus group. Furthermore, analysing data from interviews as one text, following Ricoeur was found to be an advantage, as it enabled an open-minded approach challenging researchers’ preconceptions [Citation13,Citation16]. During the data analysis, we were able to go back to the transcribed data which allowed for repeated validation of the findings [Citation18,Citation38].

Conclusion

This study identified unique knowledge about Greenlanders’ personal experiences of sucrose intolerance and personal attitudes towards health research. Sucrose intolerance was found to have impact on participants´ everyday lives, experiencing physical, emotional, and social challenges. Some of the participants developed physical symptoms due to their experience of sucrose intolerance in childhood and others in their adult life. Participants reported various symptoms, such as flatulence, pain, stomach ache, diarrhoea, and fatigue. For some, their whole body became painful and fatigued. Most of the participants with symptoms were challenged emotionally and socially, and developed coping strategies such as staying at home, when they became anxious because of gastrointestinal pain or other problems. However, in some participants’ families, several family members had symptoms related to having the genetic variant and would cope by supporting each other. Despite difficulty in socialising, they identified the “kaffemik” get-together as an important social activity in their life they wanted to take part in. These realisations underscore the importance of incorporating a user perspective in research to highlight ambivalences, as a one-sided perspective on metabolism will primarily focus on the health effects of the sucrose intolerance without acknowledging the consequences for the individual.

The participants had an open attitude towards genetic and health research, hoping that the Greenlandic people would benefit from participating in health research. This also included the present research into sucrase-isomaltase. The participants hoped that other Greenlanders would participate in health research about their unique genetics in the future. However, we also saw that some participated in health research because they felt a need to see a doctor, or because they received little support from health care regarding existing symptoms of sucrose intolerance. Thus, we found a need for more communication of health knowledge and a need of more research on sucrose intolerance, including lived experiences.

Authors’ contributions

Silvia Isidor: First author, design, data collection, investigation, formal analysis, writing -original, draft, visualisation, conceptualisation; Ninna Senftleber: Design, Supervision, writing – original, draft, editing and reviewing; Cecilie Schnoor: Data collection, reviewing; Kristine Skoett Pedersen: Data collection, reviewing; Lene Seibæk: Methodology, supervising, formal analysis, draft, editing and reviewing; Marit Eika Jørgensen: Supervision, draft, editing and reviewing, conceptualisation; Jette Marcussen: Last Author, Design, data collection, investigation, methodology, formal analysis, writing – original, draft, editing and reviewing.

Acknowledgments

Many thanks to the participants

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Andersen MK, Skotte L, Jørsboe E, et al. Loss of sucrase-isomaltase function increases acetate levels and improves metabolic health in Greenlandic Cohorts. Gastroenterology. 2022;162(4):1171. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2021.12.236

- Marcadier JL, Boland M, Scott CR, et al. Congenital sucrase-isomaltase deficiency: identification of a common inuit founder mutation. CMAJ. 2015;187(2):102–11. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.140657

- Treem WR. Congenital sucrase-isomaltase deficiency. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1995;21(1):1–14. doi: 10.1002/j.1536-4801.1995.tb11726.x

- Andersen K, Hansen T, Jørgensen ME, et al. Healthcare burden in Greenland of gastrointestinal symptoms in adults with inherited loss of sucrase-isomaltase function. Appl Clin Genet. 2024;17:15–21. doi: 10.2147/TACG.S437484

- Senftleber NK, Ramne S, Moltke I, et al. Genetic loss of sucrase-isomaltase function: mechanisms, implications, and future perspectives. Appl Clin Genet. 2023;16:31–39. doi: 10.2147/TACG.S401712

- Wielsøe M, Berthelsen D, Mulvad G, et al. Dietary habits among men and women in West Greenland: follow-up on the ACCEPT birth cohort. BMC Public Health. 2021;21(1):1426. doi: 10.1186/s12889-021-11359-7

- Pars T, Osler M, Bjerregaard P. Contemporary use of traditional and imported food among greenlandic inuit. Arct J. 2001;54(1):22. doi: 10.14430/arctic760

- Jeppesen C, Bjerregaard P. Consumption of traditional food and adherence to nutrition recommendations in Greenland. Scand J Public Health. 2012;40(5):475–481. doi: 10.1177/1403494812454467

- Jørgensen ME, Pedersen ML. Diabetes in Greenland. Ugeskr Laeger. 2020;182(V12190696):1–7.

- Kim SB, Calmet FH, Garrido J, et al. Sucrase-isomaltase deficiency as a potential masquerader in irritable bowel syndrome. Digestive Dis & Sci. 2020;65(2):534–540. doi: 10.1007/s10620-019-05780-7

- Spiegel BMR. The burden of IBS: looking at metrics. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2009;11(4):265–269. doi: 10.1007/s11894-009-0039-x

- Senftleber N, Jørgensen ME, Jørsboe E, et al. Genetic study of the Arctic CPT1A variant suggests that its effect on fatty acid levels is modulated by traditional Inuit diet. Eur J Hum Genet. 2020;28(11):1592–1601. doi: 10.1038/s41431-020-0674-0

- Ricoeur P. Interpretation theory: discourse and the surplus of meaning. 4. printing. udg. Fort Worth, Tex: The Texas Christian Univ.- Press; 1976.

- Denzin NK, Lincoln YS. The SAGE handbook of qualitative research. 5 udg. Thousand Oaks, Calif: Sage; 2018.

- Carter SM, Little M. Justifying knowledge, justifying method, taking action: epistemologies, methodologies, and methods in qualitative research. Qual Health Res. 2007;17(10):1316–1328. doi: 10.1177/1049732307306927

- Lindseth A, Norberg A. A phenomenological hermeneutical method for researching lived experience. Scand J Caring Sci. 2004;18(2):145–153. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-6712.2004.00258.x

- Thirsk LM, Clark AM. Using qualitative research for complex interventions. Int J Qualitative Methods. 2017;16(1):1. doi: 10.1177/1609406917721068

- Kvale S, Brinkmann S. Interviews : learning the craft of qualitative research interviewing. 3 udg. Thousand Oaks, Calif: Sage Publications; 2014.

- Møller H. “Double culturedness”: the “capital” of inuit nurses. Circumpolar Health Suppl. 2013;72(1):876–882. doi: 10.3402/ijch.v72i0.21266

- WMA. Declaration of Helsinki - ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. 2019; Tilgængelig via. https://www.wma.net/policies-post/wma-declaration-of-helsinki-ethical-principles-for-medical-research-involving-human-subjects/

- SSN. Ethical guidelines for nursing research in the Nordic countries: etiske retningslinier for sygeplejeforskning i Norden. rev. udg. Oslo: Sykepleiernes Samarbeid i Norden; 2003.

- Ministry of education and research. The Danish code of conduct in research. 2015; ISBN: 978-87-93151-59-8.

- Dreyer PS, Pedersen BD. Distanciation in Ricoeur’s theory of interpretation: narrations in a study of life experiences of living with chronic illness and home mechanical ventilation. Nurs Inq. 2009;16(1):64–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1800.2009.00433.x

- QRS International. NVivo. 2019; Tilgængelig via https://www.qsrinternational.com/

- Bazeley P, Jackson K. Qualitative data analysis with NVivo. 2 udg. London: SAGE Publications Ltd; 2013.

- Schnohr J. Drum dancing and inuit tattoos are also the new Greenland. ARCTIC HUB. 2021;News. https://arctichub.gl/drum-dancing-and-inuit-tattoos-are-also-the-new-greenland/

- Chey WD, Cash B, Lembo A, et al. Congenital sucrase-isomaltase deficiency: what, when, and how? Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;16(10):3–11.

- Drossman DA, Morris CB, Schneck S, et al. International survey of patients with IBS: symptom features and their severity, health status, treatments, and risk taking to achieve clinical benefit. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2009;43(6):541–550. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e318189a7f9

- Hungin APS, Chang L, Locke GR, et al. Irritable bowel syndrome in the United States: prevalence, symptom patterns and impact. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2005;21(11):1365–1375. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2005.02463.x

- Hungin APS, Molloy‐Bland M, Claes R, et al. Systematic review: the perceptions, diagnosis and management of irritable bowel syndrome in primary care - a Rome foundation working team report. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2014;40(10):1133–1145. doi: 10.1111/apt.12957

- Nilholm C, Larsson E, Roth B, et al. Irregular dietary habits with a high intake of cereals and sweets are associated with more severe gastrointestinal symptoms in IBS patients. Nutrients. 2019;11(6):1279. do i: h ttps://1 0.3390/nu11061279

- Chang L. Review article: epidemiology and quality of life in functional gastrointestinal disorders. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;20(s7):31–39. do i: h ttps://1 0.1111/j.1365-2036.2004.02183.x

- Olesen I, Hansen NL, Ingemann C, et al. The national institute of public health (statens institut for folkesundhed). Brugernes oplevelse af det grønlandske sundhedssystem. 2020. Tilgængelig via Hentet. 2022 Mar. https://www.sdu.dk/da/sif/rapporter/2020/brugernes_oplevelse_af_det_groenlandske_sundhedsvaesen_dk

- Olesen I, Hansen NL, Jørgensen ME, et al. Perspektiver på genetiske undersøgelser af diabetes, belyst gennem Sharing Circles. En kvalitativ undersøgelse i Qasigiannguit. 2020;Report. University of Southern Denmark. 978-87-7899-511-7.

- European Union. General data protection regulation - REGULATION (EU) 2016/679 of the EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT and of the COUNCIL of 27 April 2016 on the protection of natural persons with regard to the processing of personal data and on the free movement of such data, and repealing directive 95/46/EC. 2016; European Union.

- Richmond J, Sanderson M, Shrubsole MJ, et al. Psychosocial impact of COVID-19 among adults in the southeastern United States. Prev Med. 2022;163:N.PAG. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2022.107191

- Salanti G, Peter N, Tonia T, et al. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and associated control measures on the mental health of the General population: a systematic review and dose-response Meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2022;175(11):1560–1571. doi: 10.7326/M22-1507

- Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care. 2007;19(6):349–357. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzm042