ABSTRACT

In this article we explore the role of linguistic landscapes, which refers to language on display in public spaces, in the teaching of languages and enhancing language awareness. Signage can be useful for language learners as a pedagogical tool for language acquisition and to explore issues of multilingualism.

We focus in particular on the multilingual education context in the Basque Country in Spain, where the three languages of instruction are Basque, Spanish and English. Our analysis is based on data collected in public spaces, from students in primary schools and masters-level students at university. Our data include signage in a local covered market, and on the walls of schools as well as that collected among students who carried out learning tasks investigating the signage that surrounds them. We conclude that the languages on display in public spaces are an important resource for language learning and teaching, and they can also be used for raising language awareness.

RESUMEN

En este artículo exploramos el papel de los paisajes lingüísticos, que se refiere al lenguaje que se exhibe en los espacios públicos, en la enseñanza de lenguas y en la mejora de la conciencia lingüística. La señalización puede ser útil para los estudiantes de lenguas como herramienta pedagógica para la adquisición de lenguas y para explorar cuestiones relacionadas con el multilingüismo. Nos centramos en particular en el contexto de la educación multilingüe en el País Vasco en España, donde los tres idiomas de instrucción son el euskera, el español y el inglés. La base de nuestro análisis son los datos que hemos recopilado en ubicaciones en espacios públicos, dentro de las escuelas y con alumnos de primaria y estudiantes de máster en la universidad. Nuestros datos incluyen la señalización de un edificio que contiene un mercado local, paredes de escuelas, así como los datos recogidos entre los alumnos que realizaron tareas de aprendizaje investigando la señalización que los rodea. Concluimos que las lenguas que se exhiben en los espacios públicos son un recurso importante para el aprendizaje y la enseñanza de idiomas y también pueden usarse para desarrollar la conciencia lingüística.

1. Introduction

The written languages visible in public spaces can be referred to as the linguistic landscape (Gorter Citation2006, 2). Linguistic landscape studies has emerged in the last few decades a blooming field around the globe, including countries where Spanish is spoken. In their introduction to a special issue on studies of linguistic landscapes in the Hispanic world, Castillo Lluch and Sáez Rivera (Citation2013, 9) refer to “a new sociolinguistic discipline.” For Ma (Citation2018), the linguistic landscape is a new tool for teaching Spanish as a Foreign Language (E/LE). There is an increasing interest among researchers which can be clearly demonstrated by the recent publication of three edited collections on the theme of linguistic landscapes and language learning and teaching beyond the classroom (Malinowski, Maxim, and Dubreil Citation2020; Krompák, Fernández, and Meyer Citation2021; Niedt and Seals Citation2020). Collectively, these books show the pedagogical potential of public signage for language acquisition and learning about languages.

In this contribution we focus on our own linguistic landscape work in the multilingual context of the Autonomous Community Basque Country in Spain. In this community Basque and Spanish are co-official languages which are widely taught at all levels of education, though English is also taught from an early age. Also, due to migration, an increasing number of pupils bring different home languages to the classroom, including Arabic, Berber, Bulgarian, Chinese, Rumanian and Turkish as well as different varieties of Spanish, especially from Latin American countries.

2. The multilingual context of the Basque Country

The Basque Country refers to the region situated along the Bay of Biscay on both sides of the state border between Spain and France. The region consists of three provinces on the French side of the border (Nafaroa Beherea, Lapurdi and Zuberoa) and four provinces on the Spanish side. The first is Navarre (Basque: Nafarroako Foru Komunitatea; Spanish: Comunidad Foral de Navarra). The other three provinces (Araba, Bizkaia, Gipuzkoa) together form the Autonomous Community of the Basque Country (Basque: Euskal Autonomia Erkidegoa, EAE; Spanish: Comunidad Autónoma Vasca, CAV), which is often referred to as the Basque Country in English and we will do so in this article.

The Autonomous Community of the Basque Country has a population of some 2.2 million inhabitants. Most of our research has taken place in the city of Donostia-San Sebastián, the administrative capital of the province of Gipuzkoa. The city has a population of 187,000 inhabitants but serves a metropolitan area of 436,000 people (Instituto Nacional de Estadística Citation2021). In the context of our research, it is important to mention that the city claims a cosmopolitan identity and is a popular resort due to its beaches, international cultural festivals and high level of gastronomy. It attracts a relatively large number of tourists and visitors (over 1 million in 2019), about half from Spain with others from France, Germany, the UK, the US, and many other countries (IBILTUR Citation2020).

According to sociolinguistic survey data, 35.4% of the city’s inhabitants are bilingual in Basque and Spanish, 21.5% are passive bilinguals, i.e. they understand Basque but cannot speak it, and 43.1% are Spanish monolingual speakers (Basque Government Citation2019). The figures demonstrate that Basque is a minority language in the city, a fact reflected across the whole Basque Country; however, it should be noted that there are important regional differences and in many smaller towns the majority of the inhabitants are Basque-speaking. Basque and Spanish are both established as official languages by the Ley 10/1982, de 24 de noviembre, básica de normalización del uso del Euskera (Basic Law on the Normalisation of Basque Language Use; Basic Law Citation1982). The law is based on the principle that citizens can freely choose to live through Basque, Spanish or both, although in practice this is not always easy. Over the years a robust language policy has supported Basque as a minority language in all social domains. The revitalization of Basque, especially in education, has been successful in comparison to other European minority languages (Gorter, Zenotz, Etxague and Cenoz, Citation2014). Knowledge of Basque among the population has gradually increased, yet the use of Basque in daily life has not increased at the same rate. Spanish continues to be the dominant language in society and Basque has been characterised as a “vulnerable” endangered language (Moseley Citation2010).

In 1982, Basque and Spanish became compulsory subjects in all schools. Furthermore, parents are able to decide whether Basque or Spanish is the medium of instruction, as students have the right to receive it in either language. In the regional education system, there are three models of language schooling: A, B and D. The models differ according to the language of instruction and student profile (see ).

Table 1. Three models of education in the Basque Autonomous Community.

Over the years, the use of Basque as the medium of instruction (Model D) has increased steadily, and at present 76.7% of primary schoolchildren and 71% of secondary schoolchildren received their education through Basque. About 20% of all schoolchildren are enrolled in Model B and around 5% in Model A (Basque Government Citation2020). Parents have increasingly chosen model D, even if they do not speak Basque at home. Their choice can be motivated by the idea that speaking Basque is part of their identity and that it can be easier to find a job as a Basque speaker.

The increase in Basque as a language of schooling has had an effect on the number of speakers. According to the VI Inkesta Soziolinguistikoa 2016/ VI Encuesta Sociolinguistica 2016 (the 6th Sociolinguistic Survey published by the Basque Government), there were 212,000 more Basque speakers than in 1991, and the percentage of speakers increased on average from 24.1% to 33.9% in 25 years (among those aged 16 or older). The same survey reports that 71.4% of people aged between 16 and 24 can speak Basque. The Basque government also estimates that even higher figures are evident under the age of 16 (Basque Government Citation2019). English is also taught as a subject in all Basque schools starting at the age of four; in some preschool education settings it can be even earlier. In primary and secondary education, English is used as an additional language of instruction for one or two other subjects. Being proficient in English is considered a social necessity by many people in the Basque Country. Extensive testing by the Basque Institute for Research and Evaluation in Education (ISEI/IVEI) has shown that competence in Spanish and English is similar across the three models and that the level of Basque is highest in Model D. Nonetheless, despite the increased provision for Basque in education, the use of Basque language across society is still weak, and Spanish continues to dominate. Many speakers who learned Basque at school use mainly Spanish in their daily life because often there is no requirement or need to use Basque (Gorter, Zenotz, Etxague, and Cenoz Citation2014).

3. Earlier work on linguistic landscapes

3.1. Linguistic landscapes in Donostia-San Sebastián and their role in language learning

Almost 20 years ago we began our research into the linguistic landscapes of Donostia-San Sebastián with a small inventory of the signs in one street in a residential neighbourhood (Cenoz and Gorter Citation2003). In a second study, we compared the linguistic landscapes of one of the main shopping streets in Donostia-San Sebastián to a similar street in Leeuwarden-Ljouwert, the capital of the province of Friesland in The Netherlands (Cenoz and Gorter Citation2006). The two cities share the fact that both are located in a region where part of the population speaks a historical minority language, Basque and Frisian, together with the majority language of the country, Spanish and Dutch, respectively. Language policies of the regional government support these minority languages, which are also taught in school, have a presence in the media and in cultural outputs.

In our study of the signage in public spaces in both cities, we could empirically confirm that the majority language is most frequently used in the linguistic landscape. The results demonstrated that Spanish and Dutch are also the most prominent in terms of size of fonts, position of the text and the amount of information given. In the Basque Country, Basque comes in second place and English is the third language. In Friesland, Dutch is followed by English, with only a marginal place for Frisian. We attributed these differences to the effect the Basque Country’s more robust language policy, concluding that the linguistic landscape “can provide a different perspective when analyzing a sociolinguistic situation” (Cenoz and Gorter Citation2006, 79).

After our initial studies about how different languages are distributed and reflected in urban linguistic landscapes, our attention turned to the possible role that textual signs could have as material for language learners. These elements of the linguistic landscape are examples of authentic input that can support second language acquisition (SLA), the different dimensions of which we explored previously in our discussion regarding the potential of public space texts to support the learning additional languages (Cenoz and Gorter Citation2008). We argued that the signs can be useful for acquiring or promoting pragmatic competence, multimodal literacy skills and multilingual competence, and can also increase language awareness. We analyzed examples of multilingual signs as authentic input that can lead to incidental learning. Of course, people in general do not walk along a street with the idea of learning a new language from the signs, not even the learners of an additional language; however, this does not mean that learners are unaware of the signage surrounding them. Nonetheless, how much attention people pay to texts in public spaces will differ between individuals. Obviously, public signs are not designed for teaching a language and most of the time signs contain single words (often names), a short utterance and only sometimes full sentences or longer texts. Not all signs include useful vocabulary, but other dimensions are also important for language learners.

One of the dimensions we investigated in the article is the development of pragmatic competence. Texts on signs in public spaces do include different speech acts, and often use indirect language and metaphors, thus some signs can be suitable input for pragmatic competence. We present the example of a vending machine located at the beach in Donostia-San Sebastian (see ).

The vending machine has some operating instructions in small print displayed in Spanish and a larger text in Basque and Spanish that reads: Egarri al zara? ¿Tienes sed? (Are you thirsty?). The speech act performed in pragmatic terms is a request, aimed at people passing by. The request can be understood as a hint to buy a drink from the machine because of the context. Most passers-by will know the brand name, and also recognize a vending machine, which makes the request almost unnecessary. At the same time, a learner of Basque or Spanish is confronted with a request as an indirect strategy in an authentic communicative context which can raise learners’ awareness about different speech acts.

The written texts in the linguistic landscape can also be related to literacy skills in a second language. Moreover, the linguistic landscape is obviously multimodal by combining the visual and the textual. In particular, signs as material objects, like stickers, posters, shop windows or vending machines, have specific characteristics which can enhance multimodal literacy.

For example, looking again at the vending machine, a reader recognizes not only the object’s function due to its shape or its material form, but also because of the logo, the bottle, and its specific characteristics such as the shape of the bottle or the red colour. The process of recognizing and reading will include the texts in Basque and Spanish because isolating the texts from the colours, the logo, or the vending machine as a whole is near impossible. Of course, there are many other ways to develop literacy skills, but signage provides an additional opportunity in public spaces.

In 2010 we carried out a study of the linguistic landscape in education, or the schoolscape, in several schools in the Basque Country (Gorter and Cenoz Citation2015a). Our data collection included over 500 photographs of signs in classrooms, corridors, the library and the schoolyard. The teachers and students were not directly involved in the study. We analyzed the distribution of languages in these schools with Basque as a medium of instruction. It is unsurprising that Basque is the most common language used in 70% of monolingual and bi/multilingual signs. Spanish is used on 25% of signs and English appears in 16%. Obviously, the schoolscape does not reflect the language background of students. In the analysis of the signs, we distinguish nine different functions; however, we acknowledge that this list is not exhaustive and later studies can add other functions. The four most important functions for language learning are the following.

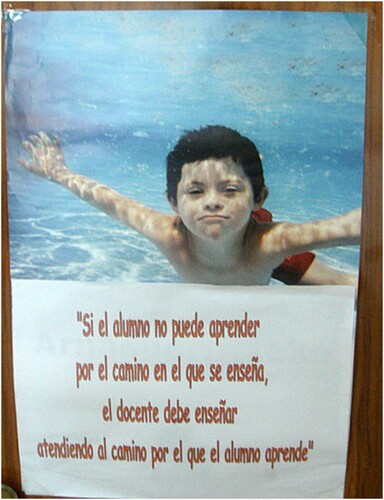

Teaching subject content or language. An obvious function of signs on classroom walls is to be instructional. The teacher can refer to them explicitly as the need arises or even include them in their planning and preparation for a lesson. An example of instructional use is given in (“If the student cannot learn by the way in which he is taught, the teacher must teach by attending to the way in which the student learns”). The sign contains not only a message about teaching, but the same phrase could also be employed in a Spanish language class.

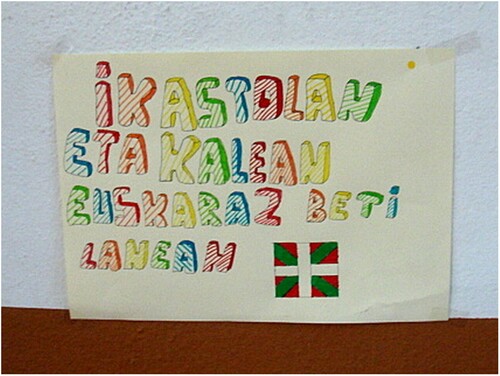

Promoting the Basque language. Schools in the Basque Country ascribe special relevance to Basque as the minority language. Our sample includes several signs that refer to efforts to revitalize Basque and its culture. A clear example is the colourful expression “ikastolan eta kalean, euskaraz beti lanean” [at school and on the street, always working in Basque]. This type of sign raises awareness about the value of the minority language for the students and, in this case, serves as a constant reminder that Basque is an endangered language.

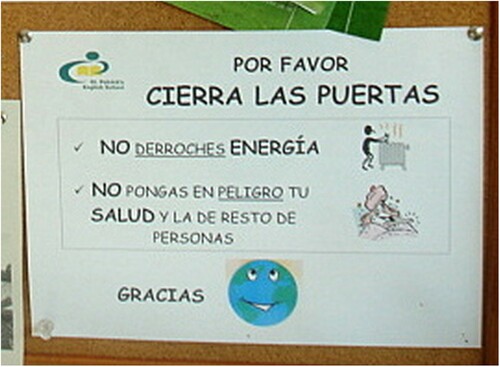

Teaching values. Some signs convey a pedagogical message about values. A prime example is the poster “Cierra las puertas.” Signs with such slogans are a constant reminder to the students of their behaviour, in this case relating to energy conservation and health.

Developing intercultural awareness. Other signs reflect the diversity of student populations. One example is in . The sign includes Ongi etorri [Welcome] in Basque as well as the word for welcome in different languages (surrounded by the flags of the countries where the children are originally from, in this case Ecuador and Romania). The idea behind the sign is probably to increase intercultural awareness among students and teachers. Several other signs also have this function, for example, signs that reported on a field trip to another country, or student work about different cultural celebrations.

3.2. Linguistic landscapes, translanguaging and education

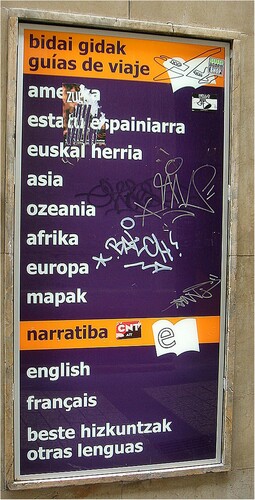

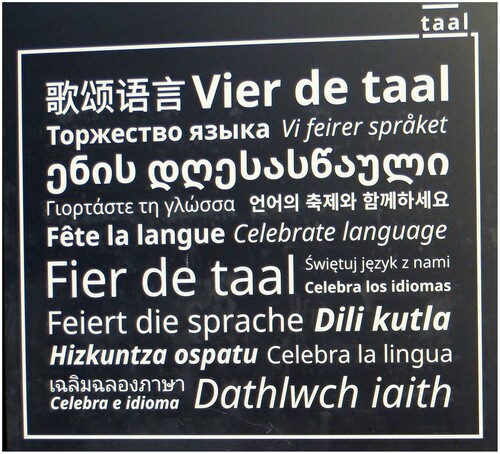

The concept of translanguaging has become a widely used term in research on multilingual education (Cenoz and Gorter Citation2017, Citation2021). In the literature on translanguaging, languages as bounded, separate codes are problematized and conceived of as flexible and dynamic multilingual practices. In Gorter and Cenoz (Citation2015b) we explored the application of the concept of translanguaging to linguistic landscapes. We examined a limited number of multilingual texts and conceptualized those as an assemblage of linguistic resources. The linguistic features on the multilingual signs are organized in specific ways in one particular local context. First, some signs were analyzed from one point of view by closely reading all the texts (see ). The next step was to take a more distanced perspective at the level of a neighbourhood in order to see how the signs combine, alternate and mix in the linguistic landscape as a whole.

Translingual practices vary between neighbourhoods, cities and also regional contexts, depending on factors such as historical developments and variation in social and linguistic diversity. Through observations of these practices we can gain insights into changes occurring in highly diverse neighbourhoods. Multilingualism is an important point of departure, and, in the physical linguistic landscape, our research focus shifts to fluid and fuzzy borders between languages, with less emphasis on languages as separate systems. The co-occurrence of linguistic features can be highlighted by translanguaging. We concluded that investigations should depart from multilingual signs as well as multilingual neighbourhoods (Gorter and Cenoz Citation2015b). Our ideas on translanguaging were adopted in an educational context by Bradley (Citation2017, 20), who suggested they can be “a lens for children and young people to develop critical and analytical skills.”

For an extensive overview of studies of linguistic landscapes in Spanish-speaking contexts, we can refer to the detailed publication by Calvi (Citation2018), which includes only a few references to studies about linguistic landscape activities in education, which is an area of which we have recently provided a summary (Gorter and Cenoz Citation2021). Her conclusion is that the linguistic landscape approach opens up new perspectives for Spanish sociolinguistics, and she identifies research about Latin-American linguistic landscapes as an area awaiting studies. However, based on work in Oaxaca, Mexico, Sayer (Citation2010) has previously documented the use of linguistic landscapes as a pedagogical resource. Calvís call has been fulfilled in some recent studies, for example, in Ecuador (Lavender Citation2020; Litzenberg Citation2018; Wobrelski Citation2020), Colombia (Weyers Citation2016; Correa and Shohamy Citation2018), Cuba (Gallina Citation2018) or Peru (Smith Citation2016).

4. Three case studies: language learning and raising language awareness

In the three different cases studies we have collected data on (1) primary school pupils as part of a project on translanguaging, (2) master-level students who carried out an assignment on textual signs in public spaces and (3) a selection of the signage in a local market.

4.1. The linguistic landscape as a learning tool in a primary school

To develop language awareness and metalinguistic awareness, we carried out a translanguaging project that included an intervention in which students executed various activities based on the principles of pedagogical translanguaging (Cenoz and Gorter Citation2021). The intervention was implemented in Basque, Spanish and English language arts classes in the 5th and 6th grades (11- and 12-year-olds) in one public primary school. The intervention took place over two academic years and a total of 104 students took part. The first languages of the participating students were Spanish (51.9%), Basque (21.2%) or both (26.9%). All subjects were taught in Basque because this was a Basque-medium school (model D).

The three language arts classes were different in terms of aims, teachers, learning activities and materials. Specifically for our project, we developed translanguaging materials which combined two or three languages in the same lesson. The aim was to highlight similarities and differences between the languages to develop language awareness about multilingualism, the use of the Basque language in society and to enhance metalinguistic awareness by making use of the students’ resources from their whole linguistic repertoire (for further details on the project see Leonet, Cenoz, and Gorter Citation2017, Citation2020).

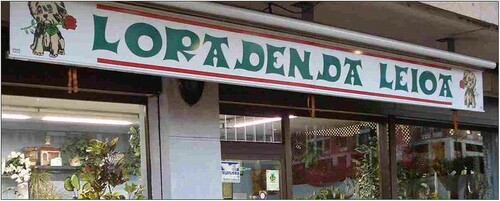

The Spanish language class includes a unit on the theme of “Linguistic landscape in your town.” The activities aim at developing language awareness on the use of different languages in the linguistic landscape of the town where the school is located. Students also learn about language hierarchy and language diversity. Firstly, students were working with a set of pictures from the linguistic landscape and, secondly, as a follow-up task, they were asked to take pictures of similar signs in their town to bring to a subsequent lesson. The pictures were then used as part of activities that aimed to enhance metalinguistic awareness about the use of compounds and derivatives as they appear on signs. One task required students to analyze shop signs and compare them in the three languages. For example, there is a shop sign with the word loradenda, which in Basque is a compound of lora + denda. They compared it to English flower + shop, which has the same elements and word order, as well as to the Spanish floristería, to make them aware of the linguistic differences (see ).

Another sign shows the Basque word liburudenda, which can be compared to the English word bookshop but is different from the Spanish librería. Simultaneously, the students learn that librería is a false friend of library in English (see also Cenoz, Leonet, and Saragueta Citation2019).

At the end of the module, students were asked to reflect on what they had learned. Here we can give a few examples of fairly typical answers. The question “What did you learn about the linguistic landscape?” was answered by one 6th grader as follows: “I have learned to divide the words; you have to know if they are composite or derived; I have learned to do it in Spanish and English; I have also learned more English.” (Original answers written in Basque or in Spanish; translation is ours). Another 5th-grade student wrote: “The day I went to take the photos of the signs I was impressed. I never looked at the signs and in almost all of them there are two languages, and you can learn words if they mean the same thing.” In a final example we observe that this student was able to analyze the linguistic landscape because she wrote: “Spanish is predominant in commercial signs. There are also many foreign languages on commercial signs: Berber, Chinese, English … I learned a lot of things, and I didn't know what a linguistic landscape was.”

We felt that the answers given by these young participants were insightful. They convinced us that, in general, students had obtained greater language awareness through the exercise. This particular linguistic landscape activity was only one part of the teaching materials developed for this translanguaging project. Also other exercises on, among others, compounds, derivatives and cognates, lead to an overall increase in metalinguistic awareness (Leonet, Cenoz, and Gorter Citation2017).

4.2. Master students as investigators of the linguistic landscape

The second case study concerns a group of students enrolled in the one-year European Master in Multilingualism and Education (EMME) at the University of the Basque Country. These students carried out an assignment focusing on linguistic landscapes. Here we report on two variants of the assignment in two different academic years and we provide excerpts of some of the students’ reflections. In the first year there were 18 students in the class and in the next year 16. Of the 34 students, just over half (18) are from the Basque Country, and just under half have Basque as their first language. About 25% (8) of the students come from other parts of Spain and about 25% (8) are from other countries, mainly from Europe, but also North America and Asia. About two-thirds have undergraduate studies in pedagogy, social work or linguistics, the others come from a variety of other backgrounds. Most of them come directly from undergraduate studies and the median age is around 23, some are a few years older. The assignment on linguistic landscapes is one of ten assignments included in a one semester course on European minority languages in education.

In the first year, 2018-2019, the assignment was to prepare a short presentation about the linguistic landscape in the format of a Pecha Kucha (a presentation style where a total of 20 slides are used, each for 20 seconds). The teacher demonstrated this format as part of an introductory lecture about common methodologies and core topics in linguistic landscape research. Thereafter, students were randomly divided into six groups of three people. The first step was to take pictures of signs in a public space that were chosen freely, for example, one street or neighbourhood or the surroundings of the university. Pictures could be of any sign, but the instruction was to try to include examples of code-switching or blending. The next step was to deliver the presentation, aiming at telling a coherent story based on the signs. Finally, each group had to write up the analysis of the signs included in the presentation, based on the following five questions.

Location: in which context is the sign placed? How does it fit there?

What meaning will passers-by (readers of the sign) derive from the signs?

Is the reader assumed to be bilingual or can he/she also be monolingual?

What is the relative status of the languages? Is there a hierarchy or power difference? How can you tell?

What about multimodal dimensions? (e.g. does the use of type or size of font or colours add to the meaning of the sign? Is its placement in the context important?)

The groups were also asked to present the research questions and a short script of the video presentation with the result of their investigation. The final videos produced by the students attested highly creative approaches to presenting the linguistic landscape (see ).

At the end of the assignment the students were asked to reflect on their experiences of exploring the linguistic landscape. All evaluations without exception were positive, and the students seemed to enjoy carrying out the assignment as a group task. The linguistic landscape was not something they had paid much attention to prior to this activity. Some of their comments were Student A:“It was totally different to see my same everyday environment with different lenses. I really enjoyed taking this class.” And student B stated: “Going to the streets and having real pictures was crucial for me, and I am very conscious of the linguistic landscape that surrounds me right now.”). They also enjoyed the practical side of working with the real-life materials of multilingual signage in public spaces in their own surroundings (Student C: “I have never heard about this before and it was very interesting how this can vary. What is more, the activity of linguistic landscapes was very practical and I had a very nice time carrying it out.”) Those signs are, in principle, familiar to them, but now they look at them through a different lens.

Using the linguistic landscape as a tool in this university master about multilingualism and education is one way to connect the theory to the content of the signs. Moreover, the answers of the students demonstrated that doing the assignment has a positive learning effect and similar impact. The final products of the groups were different, but, no correlation could be established between quality and background variables such as first language, nationality or specialization.

4.3. The market of San Martin as language learning environment

The market of San Martin is in the city centre of Donostia-San Sebastián. The building combines a traditional food market with a modern shopping mall and a parking garage. Large numbers of locals from the city and the region as well as foreign visitors shop in this complex. The ground floor and the basement house a traditional market with 40 stalls where fruit, vegetables, meat, fish and other products are sold. The basement also holds a large supermarket and a few small shops. The building further contains two large, global retail chains, Zara (clothing) and Fnac (cultural and electronic products), which both extend via escalators to three higher floors. This building is the setting for our data collection. In this case study, which is part of a larger project about language use in the market by customers and staff in the linguistic landscape (Gorter, Cenoz, and Van der Worp Citation2022), we conceive the linguistic landscape of the market as a space for language learning and for raising language awareness and we present a short analysis of a selection of signs from a database of photographs of the signs (n=850). Our aim is to reflect on opportunities for learning Spanish as a first or second language, and similarly to look at opportunities for learning Basque and other additional or foreign languages. As alluded to above, almost any sign can have a function as an additional source of authentic input (Cenoz and Gorter Citation2008).

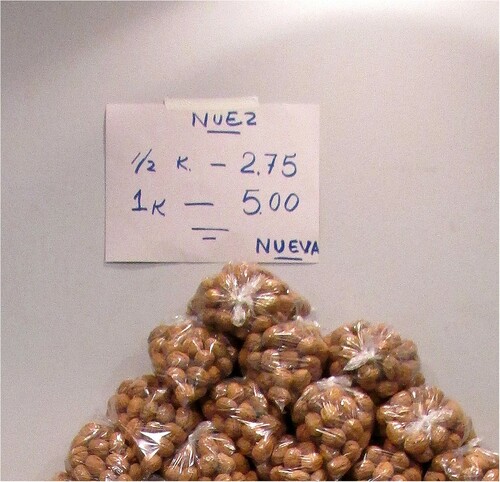

In the market we observed that some vegetable stalls do not display signs with the names of the products on sale, but simply the price in Euros. However, the more common type of sign has a tag mentioning the product´s name and price. Quantitatively, most signs are in one language only (58.2%) and Spanish appears most frequently, as in the following example (see ).

The handwritten monolingual sign with the words nuez and nueva is similar to pictures in learning methods to develop vocabulary with a direct link between the image and the new word. Of course, it was not intended as such by the salesperson and probably customers can recognize walnuts and so do not require the written information. The sign could still offer an opportunity for a young child who as a beginning reader can practice their reading skills. This form of emergent literacy development has been studied in the tradition of environmental print (Giles and Tunks Citation2010). For Spanish language beginners, a moment of spontaneous language learning could take place, and it could even be a way to increase their vocabulary. An English speaker might even learn that nut is not completely equivalent to nuez. This is a rather simple example, but there are also signs in the market with exotic foods like cherimoya, (also spelled chirimoya), that can help to learn the names of lesser-known fruits. Of course, signs in Spanish can be more complex, as shows.

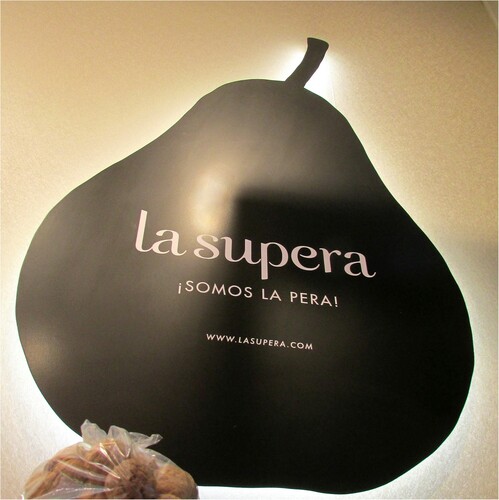

The name of a fruit and vegetable stand is La Supera, and their slogan states, ¡Somos la pera!, similar to the English expression the bee’s knees, which means to be of an extremely high standard. The sign offers a nice example of wordplay with the word pera (pear), which presupposes a relatively high level of Spanish. The name blends super and pera, which suggests being ‘more than super’, and it can also be associated with the Spanish verb superar (to exceed or to surpass). The colloquial expression ¡Somos la pera! (literally ‘we are the pear’) likewise refers to the quality of products sold on the stall, but only skilled second language learners of Spanish would probably know this meaning; otherwise, the pun would be missed. The sign shows that monolingual signs can be important for language acquisition or for reflecting on language structures, to which one could add the multimodal aspects of the shape of the sign and its colour. Visitors to the San Martin market cannot avoid observing the Basque language, which has a presence on 33.6% of all signs, on its own or in combination with Spanish or other languages. shows a monolingual sign similar to the first one in Spanish is.

The sign with the word intxaurrak (walnuts) could function in the same way as the Spanish version at the other stall. We mentioned above that many children from Spanish speaking homes go to Basque medium schools, so reading this sign could either introduce them to a new word or reinforce a less frequent word. The same could be true for adult learners of Basque as a second language (of which there are many). A learner might even notice the plural k in contrast to the Spanish sign. For tourists with little knowledge of either Spanish or Basque, it might create some awareness about the differences between both languages, and perhaps they would become able to distinguish between the two. In order to contrast the languages, it might be better to look at bilingual Basque-Spanish signs, which are rather common in this market (18.6% of all signs). presents an example.

The bilingual sign in is one more example of authentic input for language learners. The text on the sign is limited, offering simply the product name in both languages. At the same time, it can be instructive for a learner of Spanish or Basque (or both) because the words manzana and sagar are completely different, which would be expected for two linguistically unrelated languages. The photograph of apples on the lid of the pot supports the text. There are, however, also similarities in the words puré and purea, evidence of a loanword in Basque. Other differences are related to syntax; in this case word order (puré goes first in Spanish, but purea second in Basque) and prepositions (de in Spanish versus absence of a preposition in Basque). Further observations could be made about this sign, such as the lack of an accent on puré which, according to the official established language norm, should be there (also on capital letters). It is also telling that the sign has the phrase sin gluten (without gluten) only in Spanish, and a learner of Basque might want to find the word for without gluten in Basque. In terms of enhancing language awareness, the fact that an important piece of information is only in Spanish could be interpreted as an indicator of the stronger and hierarchically more important position of Spanish, which is confirmed by its top-position. From this relatively simple bilingual sign, we can conclude that apart from providing visibility to the two local languages, it offers various features relevant for language learning and reflection.

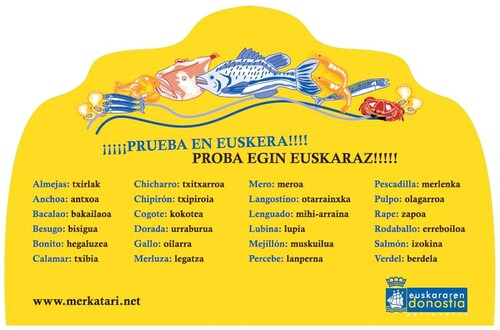

A more direct effort to influence customers’ language use can be found in a sign on the wall of a fish stall in . The sign is part of a campaign to promote the use of the Basque language.

The title of the sign displayed both in Spanish and in Basque means Taste in Basque. It is crowned by an illustration of different types of colourful fish. The main body of the sign displays a parallel list of 24 Spanish and Basque names of fish and seafood. At the bottom is a reference to a website and a logo of the Basque language department of the city council. In many ways, the sign’s design is similar to a vocabulary list that can be found in a textbook. The aim is to encourage local customers to use the Basque names of products as part of a local campaign to support Basque that ran some years ago. If customers only know a specific name in Spanish, they can use the sign as a cheat sheet for Basque. They can use Basque during interactions with the fishmonger and, if they are regular customers, the idea is that they will pick up the Basque word. Obviously the sign has the purpose of raising awareness about the importance of using the Basque language, as well as offering an opportunity for learning specialised terminology in what is a second language for a large proportion of the population.

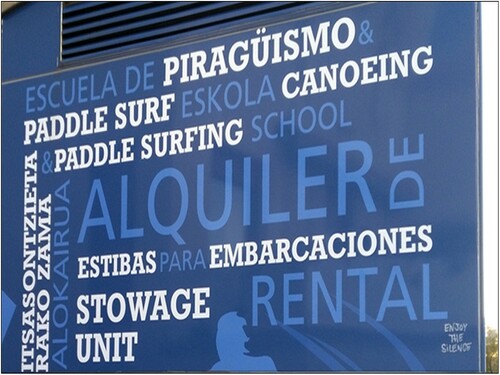

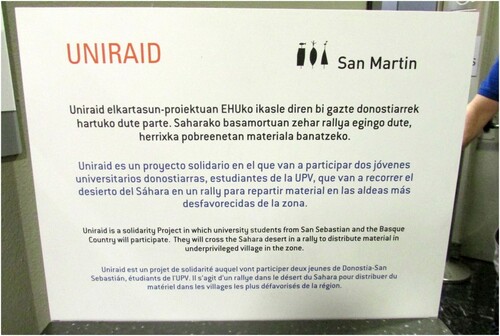

Additional or foreign languages are visible in the market building almost always in combination with the local languages Basque and Spanish, although three or more languages on a multilingual sign are less common (10%). The example in shows a sign in four languages (Basque, Spanish, English and French).

This multilingual sign is primarily aimed at readers of the four different languages based on a monolingual understanding that each reader needs its own language version. This sign can also serve as a brief moment of language learning with authentic language input for visitors who try to understand the Basque or the Spanish text. Readers of this type of sign expect that the messages are literal translations in the four languages, a phenomenon known as “duplicating” (Reh Citation2004). Close reading of the four texts shows, however, that the translation is not word for word, and a reader could try to figure out the differences. The text is much longer than that on most other signs but similar to the bilingual price tag, and again it can be used for comparisons of vocabulary, syntax, pragmatics and multimodal characteristics. Further, a reader could reflect on why these four languages were chosen and not others and on the hierarchy of the vertical arrangement with the minority language Basque on top. The differences in size and colour could be interpreted as having meaning because the font of Basque and Spanish is a little larger than that of English and French. The sign explains that the proceeds will go to the cause of Uniraid. The word Uniraid is in red and in a larger font without translation. It is obviously a proper noun that does not clearly belong to any of the four languages. The word itself is a Spanish blend of uni (for universidad) and raid, which is an English loanword in Spanish: “Prueba deportiva en la que los participantes miden su resistencia y la de los vehículos o animales con los que participan recorriendo largas distancias” (English: “Sports test in which the participants measure their resistance against that of the vehicles or animals with which they participate, traveling long distances” (Real Academia Española Citation2021; translation is ours).

The explanation of the raid is given in the sign: “Uniraid is a solidarity project in which university students from San Sebastian and the Basque Country will participate. They will cross the Sahara Desert in a rally to distribute material in under-priviliged villages in the zone.” This word Uniraid can link the local market to globalisation and the sign demonstrates global, long-distance links to remote villages in Africa. In other words, multilingual signs may help to raise awareness regarding the languages that have a presence in a certain context.

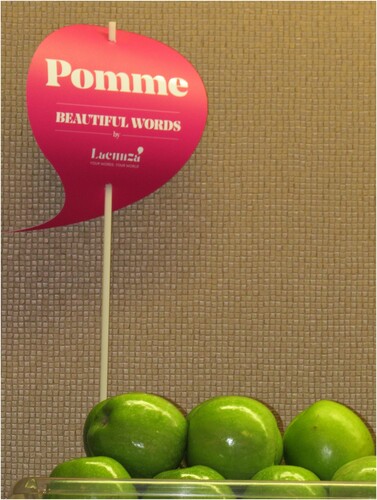

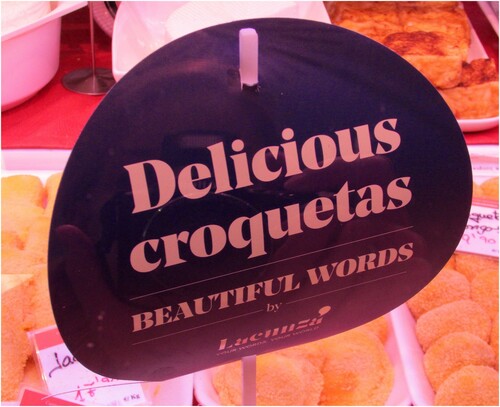

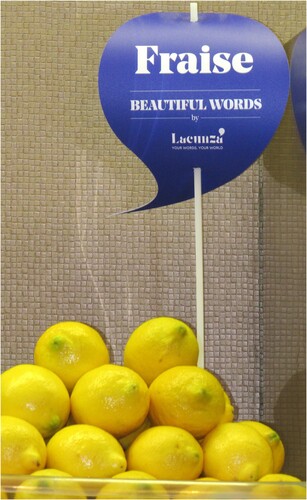

During our fieldwork at the market, we found several signs placed by a local language academy as part of their campaign called beautiful words. These signs are basically advertisements for courses in English and French offered by this business, but at the same time they aim at raising language awareness and produce an interest in learning languages, which is reinforced by their slogan your words, your world in small unreadable letters (, and ).

In one sign, the word pomme is put next to a bowl of green apples, suggesting the link between the word in French and the product, similar to the previous example of the walnut in Spanish and Basque. This sign could be seen as a method for learning some basic vocabulary in French and pragmatically an invitation to learn more when enrolling in a course. Although being able to exploit this sign in such a way would require some pre-existing knowledge on the part of the viewer. In the next example in , a word in English is used combined with a Spanish product name.

However, in this sign the word croquetas is not translated into English, but from the context it is clear what it refers to. Someone who is not proficient in English might wonder what delicious means, although most would understand because it is a cognate with Spanish (deliciosas). In this case the method of linking the word to the product next to it works only partially. Tourists, however, could use it as input to become familiar with Spanish food vocabulary. A lack of correspondence between a word and a product can lead to an awkward situation, as is the case in .

Here the French word fraise (strawberry) does not match the bowl of lemons next to it. If someone was serious about learning the meaning of these French words for different types of fruit from these signs, it would be counterproductive. However, a visitor who is not able to distinguish between English and French might not notice; some persons might even think it is Spanish or Basque. For us as researchers, it was not clear if the person who placed the sign (perhaps the salesperson) understood its meaning. It is, of course, also notable that each sign has the name of the campaign only in English and not in French.

All in all, these examples from the market as a multilingual environment demonstrate their potential for language learning, although their primary aim is not educational. Moreover, the signs make languages visible and can enhance awareness about the status of different languages in society both to local and non-local visitors of the market.

5. Conclusion

In this article we have summarized some of our earlier work related to linguistic landscapes, and have briefly presented three case studies that demonstrate the possibilities that the linguistic landscape can provide for language learning. In each case we can conclude that the languages on display in public spaces can be an important resource for language learning and teaching, as well as being a useful tool for raising language awareness. Also, we want to reiterate the links that exist between the three studies. For example, in the first two case studies, both show that students in primary school and at university, become more aware of the linguistic landscape after practical exercises in which they interact with items from the landscape. The third study shows clear opportunities for input into language learning for the general public, which are at the same time examples that could also be used as learning materials in the first two cases.

Our findings are in line with studies reported in recent edited collections about language teaching in the linguistic landscape (Malinowski, Maxim, and Dubreil Citation2020), educational spaces (Krompák, Fernandez, and Meyer Citation2021) and beyond the classroom educational settings (Niedt and Seals Citation2020). These publications and others all deal with the great potential that the display of languages in public spaces holds for language teaching both inside and outside the classroom (Gorter and Cenoz Citation2021). The linguistic landscape offers a chance to link the classroom with real language use in society. What is learned inside the classroom can be reinforced in the context of natural language use. At the same time the linguistic landscape provides numerous opportunities for language acquisition and learning about languages that can be taken into the classroom. Even in contexts where Spanish has little or no presence in public spaces, opportunities for using language on signage can be created through the internet, for example, through Streetview (Gómez-Pavón Durán, and Quilis Merín Citation2021). In the case of Ma (Citation2018, 162-163), it is fundamental that teachers and students become aware that incidental learning of Spanish can happen in any corner of the city because this is also “a classroom of Spanish.” Of course, the linguistic landscape has its limitations, but for teachers and for researchers there is still a lot to be discovered about this rich pedagogical tool. In a holistic approach to linguistic landscape studies (Gorter Citation2021), there is a need to incorporate research about the schoolscape as well as the application of linguistic landscapes as a pedagogical tool.

References

- Basic Law. 1982. Basic Law on the Normalisation of Basque Language Use (Law 10/1982, BOPV 16 December 1982). Vitoria-Gasteiz: Basque Government.

- Basque Government. 2020. Información matrícula 2020-2021. s.l.: s.i. www.euskadi.eus/contenidos/informacion/matricula_graficos_evolutivos/es_def/adjuntos/EAE_eredua_OBLI.pdf.

- Basque Government. 2019. Sixth Sociolinguistic Survey 2016. Vitoria-Gasteiz: Servicio Central de Publicaciones del Gobierno Vasco. https://www.euskadi.eus/contenidos/noticia/eas_mas_noticias/en_def/adjuntos/inkesta_EN.pdf.

- Bradley, J. 2017. “Translanguaging Engagement: Dynamic Multilingualism and University Language Engagement Programmes.” Bellaterra Journal of Teaching & Learning Language & Literature 10 (4): 9-31.

- Calvi, M. V. 2018. “Paisajes lingüísticos hispánicos: panorama de estudios y nuevas perspectivas.” LynX Panorámica de Estudios Lingüísticos 17: 5-58.

- Castillo Lluch, M. and D. Sáez Rivera 2013. “Introducción.” Revista Internacional de Lingüística Iberoamericana 21: 9-22.

- Cenoz, J. and D. Gorter. 2021. Pedagogical Translanguaging. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Cenoz, J. and D. Gorter. 2017. “Minority Languages and Sustainable Translanguaging: Threat or Opportunity?” Journal on Multilingual and Multicultural Development 38 (10): 901-912. https://doi.org/http://doi.org/10.1080/01434632.2017.1284855.

- Cenoz, J. and D. Gorter. 2008. “Linguistic Landscape as an Additional Source of Input in Second Language Acquisition.” International Review of Applied Linguistics in Language Teaching 46 (3): 257-276.

- Cenoz, J. and D. Gorter. 2006. “Linguistic Landscape and Minority Languages.” International Journal of Multilingualism 3 (1): 67-80. Doi: https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14790710608668386.

- Cenoz, J. and D. Gorter. 2003. The Linguistic Landscape of Erregezainen / Escolta Real. Paper presented at the Third Conference on Third Language Acquisition and Trilingualism, September 2003, Tralee, Ireland.

- Cenoz, J., O. Leonet, and E. Saragueta. 2019. “Cruzando fronteras entre lenguas.” Textos Didáctica de la Lengua y de la Literatura 84: 33-39.

- Correa, D. and E. Shohamy. 2018. “Commodification of Women’s Breasts: Internet Sites as Modes of Delivery to Local and Transnational Audiences.” Linguistic Landscape 4 (3): 298-319.

- Gallina, F. 2018. “El paisaje lingüístico de un país revolucionario: el caso de Cuba.” Cultura Latinoamericana. 28 (2): 46-74. Doi: https://doi.org/http://doi.org/10.14718/CulturaLatinoam.2018.28.2.3.

- Giles, R. M. and K. W. Tunks. 2010. “Children Write Their World: Environmental Print as a Teaching Tool.” Dimensions of Early Childhood 38 (3): 23-29.

- Gómez-Pavón Durán, A. and M. Quilis Merín. 2021. “El paisaje lingüístico de la migración en el Barrio de Ruzafa en Valencia: una mirada a través del tiempo.” Cultura, Lenguaje y Representación 25: 135–154.

- Gorter, D. 2021. “Multilingual Inequality in Public Spaces: Towards an Inclusive Model of Linguistic Landscapes.” In Multilingualism in Public Spaces: Empowering and Transforming Communities, eds. R. Blackwood and D. A. Dunlevy, 13-30. London: Bloomsbury.

- Gorter, D. 2006. “Introduction: The Study of the Linguistic Landscape as a New Approach to Multilingualism.” International Journal of Multilingualism 3 (1): 1-6.

- Gorter, D., J. Cenoz, and K. Van der Worp. 2022. “Global and Local Forces in the Multilingual Landscape: A Study of a Market.” In Trajectories of Language: Policies, Spaces, and Interactions, eds. R. Blackwood and U. Røyneland, 188-212. London and New York: Routledge.

- Gorter, D. and J. Cenoz. 2021. “Linguistic Landscapes in Educational Contexts: An Afterword.” In Linguistic Landscape and Educational Spaces, eds. E. Krompák, V. Fernández, and S. Meyer, 277-290. Bristol: Multilingual Matters.

- Gorter, D. and J. Cenoz. 2015a. “The Linguistic Landscapes inside Multilingual Schools.” In Challenges for Language Education and Policy: Making Space for People, eds. B. Spolsky, M. Tannenbaum, and O. Inbar, 151-169. London and New York: Routledge.

- Gorter, D. and J. Cenoz. 2015b. “Translanguaging and Linguistic Landscapes.” Linguistic Landscape 1 (1): 54-74.

- Gorter, D., V. Zenotz, X. Etxague, and J. Cenoz. 2014. “Multilingualism and European Minority Languages: The Case of Basque.” In Minority Languages and Multilingual Education: Bridging the Local and the Global, eds. D. Gorter, V. Zenotz, and J. Cenoz, 278-301. Berlin: Springer.

- IBILTUR. 2020. Estudio del perfil y comportamiento del turista que visita la C.A. de Euskadi. s.l.: s.i. https://www.euskadi.eus/web01-s2tumerk/es/contenidos/informacion/tur_estatis_ibiltur_port/es_def/index.shtml.

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística. 2021. Cifras oficiales de población resultantes de la revisión del Padrón municipal a 1 de enero. Resumen por comunidades autónomas. Madrid: Instituto Nacional de Estadística. https://www.ine.es/jaxiT3/Datos.htm?t=2853#!tabs-tabla.

- Krompák, E., V. Fernández, and S. Meyer, eds. 2021. Linguistic Landscape and Educational Spaces. Bristol: Multilingual Matters.

- Lavender, J. 2020. “English in Ecuador: A Look into the Linguistic Landscape of Azogues.” Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development 41 (5): 383-405. Doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/01434632.2019.1667362.

- Leonet, O., J. Cenoz, and D. Gorter. 2020. “Developing Morphological Awareness across Languages: Translanguaging Pedagogies in Third Language Acquisition.” Language Awareness 29 (1): 41-59.

- Leonet, O., J. Cenoz, and D. Gorter. 2017. “Challenging Minority Language Isolation: Translanguaging in a Trilingual School in the Basque Country.” Journal of Language, Identity & Education 16 (4): 216-227.

- Litzenberg, J. 2018. “‘Official Language for Intercultural Ties’: Cultural Concessions and Strategic Roles of Ecuadorian Kichwa in Developing Institutional Identities.” Linguistic Landscape 4 (2): 153-177.

- Ma, Y. 2018. “El paisaje lingüístico: una nueva herramienta para la enseñanza de E/LE.” Foro de profesores de E/LE 14: 153-163.

- Malinowski, D., H. H. Maximand, and S. Dubreil, eds. 2020. Language Teaching in the Linguistic Landscape: Mobilizing Pedagogy in Public Space. Berlin: Springer.

- Moseley, C., ed. 2010. Unesco Atlas of the World’s Languages in Danger. 3rd ed. Paris: UNESCO Publishing.

- Niedt, G. and C. A. Seals, eds. 2020. Linguistic Landscapes Beyond the Language Classroom. London: Bloomsbury.

- Real Academia Española 2021. Diccionario de la lengua española. Madrid: Real Academia Española. https://dle.rae.es/

- Reh, M. 2004. “Multilingual Writing: A Reader-Oriented Typology—with Examples from Lira Municipality (Uganda).” International Journal Sociology of Language 170: 1-41.

- Sayer, P. 2010. “Using the Linguistic Landscape as a Pedagogical Resource.” ELT Journal 64 (2): 143-154.

- Smith, B. 2016. “More Landscape, Less Language: Digital Gaming, Moral Panic, and the Linguistic Landscapes of Southern Peru.” Signs and Society 4 (2): 155-175.

- Weyers, J. R. 2016. “English Shop Names in the Retail Landscape of Medellín, Colombia.” English Today 32 (2): 8.

- Wroblewski, M. 2020. “Inscribing Indigeneity: Ethnolinguistic Authority in the Linguistic Landscape of Amazonian Ecuador.” Multilingua 39 (2): 139-168. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1515/multi-2018-0127.