ABSTRACT

This article focuses on representation and government formation in the Italian regions in the electoral cycle from 2018 to 2020. By relying on a large number of data collected in the 18 regions and 2 autonomous provinces that went to the polls in this period, it looks at how votes translated into seats and assesses the disproportionality and fragmentation of the newly elected councils. It also considers the composition of winning coalitions and how divided they are vis-à-vis the opposition. Additionally, this study explores some key characteristics of regional representatives such as gender, age and political experience, stressing the existence of significant variation across regions and parties. In an unprecedented effort to provide a comprehensive map of policy-making elites at the sub-national level, the analysis also includes members of the regional executives (assessori). Overall, while some regions stand out more than others, it is not possible to identify a general model of democracy defining Italian sub-national politics.

When analysing regional elections, much attention is (rightly) devoted to how votes are distributed and how these votes translate into victory or defeat for parties and coalitions. Fragmentation, disproportionality and specific characteristics of the elected representatives are additional details, which tend to be overshadowed by the overall election outcome. Yet in multiparty democracies the formation, decision-making and survival of governments depend not only on who gets more votes and seats but also on how these seats are assigned among different parties and who occupies them. This article seeks to explore these aspects of representative politics in the Italian regions during the electoral cycle going from 2018 to 2020. In three years, 18 regions and 2 autonomous provinces went to the polls. Only Sicily, which voted in 2017, lies outside this period starting from the ‘tsunami’ general election of 2018 (Calossi and Cicchi Citation2018).

Italian politics has undergone profound transformations over the last decade, in the aftermath of the financial crisis and Great Recession (Karremans, Malet, and Morisi Citation2019). Its party system, which had already been significantly altered by the political crisis of the 1990s, underwent a new process of restructuring. It saw the collapse of a ‘bipolar system’, based on the alternation between centre-left and centre-right coalitions, and the emergence of new political dynamics and electoral realignments. Regions were not immune to this. The shift in political equilibria at the regional level accelerated in the electoral cycle of 2013–2015, which followed the ‘earthquake’ 2013 general election (Chiaramonte and De Sio Citation2014). As highlighted by various studies, regional party politics became more fragmented and volatile (Vampa Citation2015; Bolgherini and Grimaldi Citation2017).

Building on previous research on Italian sub-national democracy, the aim of this article is to understand whether the instability and fracturing of political representation detected in the 2013–2015 cycle have persisted or even increased in more recent years. Additionally, the analysis seeks to address a question, which has not been fully answered by the existing literature: what are the key characteristics of the political personnel that have emerged from a decade of significant political change?

This article first provides a general framework, which can be used for the analysis of politics at both representative/legislative and executive institutional levels. Then it empirically shows that the Italian regional councils elected between 2018 and 2020 have generally become more fragmented thanks to the rise of local and personal lists. The composition of governing coalitions in the Italian regions has also been affected by growing fragmentation. This does not necessarily suggest that regional executives have become weaker. In fact, the declining role of political parties as territorially integrated organizations has resulted in the strengthening and increasing autonomy of regional leaders, particularly in the aftermath of the Covid-19 pandemic. The second part of the article looks at the characteristics of the new representatives and members of the regional executives. It shows that there is significant cross-party and cross-regional variation in some key variables, such as age, gender and the political experience of the political personnel. This reinforces the picture of a regional political system that is too internally diverse and divergent – beyond left-right orientations and the traditional north-south divide – to be captured by general definitions.

Assessing regional representative democracy after an election: councils, governments and political personnel

What happens after an election? Most observers, particularly those addressing broad audiences and readerships, often focus on who wins and has the right to form a new government. From a zero-sum, ‘winner-takes-it-all’ political perspective, this is certainly the most consequential outcome of the vote count. Yet the way votes are converted into seats, which, in turn, influences the allocation of executive offices, may evolve over time, not only due to actions and reactions of political competitors but also to broader structural changes: new electoral systems, changes in political supply, socio-economic transformations. Here it would be too ambitious to uncover the causal factors influencing the way sub-national representative democracy works. In the case of Italian regions, there is a rich literature on how representation and policy making have been affected by changing electoral mechanisms since the mid-1990s (Wilson Citation2015), intra-party dynamics and inter-party political competition (Hopkin Citation2009; Basile Citation2015), and socio-economic factors (Vassallo Citation2013).

This contribution has a narrower scope, since it aims to understand:

whether there is an increasing discrepancy (disproportionality) between distribution of votes and seats in Italian regional councils;

whether the recent electoral cycle in Italy has led to more political fragmentation;

whether fragmentation has increased more for winning or losing coalitions.

Yet we should not limit our analysis to the time dimension and just consider change between the previous election cycle and the current one. Here we also make a cross-sectional comparison: can we identify a common pattern across all regions? Do they diverge significantly? These are important questions because clear differences across regions would indicate the existence of multiple ‘patterns’ of sub-national representative democracy in Italy. Any attempt to place them under the same definitional umbrella would therefore risk overlooking a complex and heterogeneous reality.

There is a set of indicators that can be used to analyse the three aspects listed above (). In order to assess the way votes are translated into seats and measure the gap between the electoral and representative arenas, we can resort to the index of disproportionality developed by Gallagher (Citation1991). Italian regions rely on a mix of proportional and majoritarian systems, which, over time, have changed and, to a certain extent, diverged. Since 1999, with the reform of article 122 of the Italian constitution, regional Presidents have been directly elected in all but two regions: Valle d’Aosta and the Autonomous Province of Bolzano (Mariucci Citation1999; Wilson Citation2015). Yet, contrary to what happens in pure presidential systems, the legislative body (i.e. the regional council) and the head of the executive are not elected separately. Each presidential candidate is supported by one or more electoral lists. Seats in the council are then allocated among these lists based on which presidential candidate obtains a plurality of the vote (Massetti Citation2018, 330–331). While directly elected, a regional president can still be removed by a no-confidence motion supported by an absolute majority of the councillors, as stated by article 126 of the Constitution. Control of the legislature is therefore essential for the well-functioning and survival of the executive and a ‘majority’ bonus is assigned to the winning coalition to cement its stability. The size of the majority bonus varies across regions and also depends on the margin of victory – i.e. a coalition winning a very large share of the vote, well above 50%, will be more self-sufficient and, consequently, will be allocated only part or none of the extra seats granted by the bonus. It follows that the level of disproportionality has varied over time and across regions.

Table 1. Assessing representative democracy in Italian regions: a framework

The electoral systems also partly affect the fragmentation of representation in the regional councils. Yet other factors, such as the multiplication of political actors, the disintegration of traditional parties and a more mobile electorate, may contribute to this. The 2013–2015 electoral cycle already marked a critical point in the history of Italian regional democracy, with the effective number of parties (ENP) reaching a record point (Bolgherini and Grimaldi Citation2017; Vampa Citation2015). By using the Laakso and Taagepera (Citation1979) index, it is possible to calculate the ENP in the electoral arena (ENPV), which considers how vote shares are distributed. Calculations are instead based on seat shares to assess fragmentation in regional councils (ENPS). The correlation between the two measures tends to be quite strong but it may be weakened by the disproportionality of the electoral system.

However, just looking at the fragmentation of the entire party system does not tell us the whole story. An aspect that is rarely considered by comparative studies is whether the ENP differs between the two main camps of a democratic system: government and opposition. Maeda (Citation2010) has adapted the Laakso-Taagepera index to assess the fragmentation of opposition parties in order to see how this impacts on the fortunes of governing parties. The rationale of the index is the same as that of the general ENP, with a score of 1 meaning that the opposition is formed by just one party, 2 meaning that there are two opposition parties of exactly the same size, and so on. In this article the same index is also applied to the ruling coalition to determine whether it is more or less fragmented than its opposition. In an anomalous presidential system like the one existing in Italian regions, government formation is still linked to parliamentary dynamics (i.e. the composition of regional councils). Therefore, rather than focusing on vote shares, this time we only consider how seats are distributed within the government and opposition camps (ENPSM; ENPSO). In a two-party system ENPSM and ENPSO would both be 1. If, instead, we have a one-party government and an opposition controlled for two thirds by a party and one third by another, ENPSM would still be 1 but ENPSO would be 1.8, and so on.

Fragmentation of governing and opposition parties can be combined with a measure of competitiveness. In studies on government formation, the difference in seats between the largest and second-largest parties has been used to assess the advantage of the former over the latter (Krook and O’Brien Citation2012). This simple formula is adapted to multi-party democracy in Italian regions. Rather than looking at the largest vs second-largest party, here the focus is on the difference in the percentage of the seats held by all parties included in a governing coalition and those excluded from it.

The indicators presented above give us a general, macro-level picture of how elections are linked to the partisan composition of representative institutions and the process of government formation. They do not tell us much about the characteristics of the political personnel populating regional institutions in the aftermath of an electoral cycle. The most recent, comprehensive description of the profiles of Italian regional councillors dates back to 2013 and refers to data available up to 2005 (Cerruto Citation2013). No study in English has provided detailed information on who currently sits in Italian regional councils and regional governments. This is surprising given the political turmoil that has shaken Italian democracy over the last decade and has reshaped political elites at all levels.

This article aims to partially bridge this gap by focusing on councillors and members of regional governments (giunte regionali). The following characteristics are considered for both sets of policy makers: age, gender, political experience at the regional and local levels. The analysis is mostly cross-sectional, looking at differences among regions and among political parties/coalitions.Footnote1 In the case of members of the executive, an additional indicator is considered: whether they have been selected among the pool of elected councillors or, instead, have been directly nominated by the regional President. This latter aspect would give us an idea of the level of ‘autonomy’ of regional governments vis-à-vis councils. summarizes the indicators that will be used for the empirical analysis. All data were collected before 31 December 2020 from an official database of the Italian Interior Ministry, which provides extensive details of elected officials in municipalities, provinces and regions.Footnote2 The analysis relies on the profiles of more than 1,000 policy makers: 817 councillors and 186 regional ministers (assessori) and Presidents. Only Sicily is not included in the analysis since it held its last regional elections before the period considered here (2018–2020).

Table 2. Identifying the political personnel of Italian regions (2018–2020)

Making votes count: regional councils, government and opposition after the elections

Before moving to a discussion of the various indicators presented in the previous section, we should consider the overall partisan composition of regional councils after the 2018–2020 electoral cycle and compare it to the previous one. summarizes the share of the vote won by the main parties. looks at how it translated into seats across all regional councils. It is interesting to see that the centre-left Partito Democratico (Democratic Party, PD) experienced the sharpest drop in electoral support and was replaced by the right-wing populist Lega (League) as the largest party. Yet the general picture is one of increasing fragmentation, confirming the developments already observed in 2013–2015. Unlike 2010, when each of the two largest parties obtained more than 25% of the vote (Tronconi Citation2010), today their combined share remains well below 50%. This is also reflected in their share of seats (). Again, the PD seems to be the big loser and the League the big winner but neither of them obtains more than 25% of the seats in regional councils. In 2013–2015, the PD still played the role of dominant party in a political context that, outside the centre-left camp, was already highly fragmented. Now the party has lost its primacy and this has resulted in an even more ‘fluid’ political environment. The group ‘other’, including many local lists, remains the largest one.

Figure 1. Vote shares of main Italian parties in regional elections: 2013–2015 and 2018–2020 cycles

Figure 2. Shares of seats won by main Italian parties in regional elections: 2013–2015 and 2018–2020 cycles

suggest the existence of some discrepancies between votes and seats. In 2013–2015 the PD’s share of seats was 6 percentage points greater than its share of the vote, thanks to the party’s victory in most regions (it was defeated only in Lombardy, Veneto and Liguria) and the consequently positive effect of majority bonuses on its representation. The same occurred on the right in 2018–2020. The League won most regional contests as the leading force of centre-right coalitions and, consequently, benefitted more from majority bonuses than in 2013–2015. The Movimento Cinque Stelle (Five-star Movement, M5s) is consistently underrepresented since, by running outside the main coalitions, it has never won a regional election.

shows that disproportionality (Gallagher index) remains relatively high across the Italian regions. Overall, they are closer to the more disproportional democratic systems of Europe, such as France, Greece, Portugal and the UK, than to state-wide Italy, which in the 2018 general election only had a disproportionality of 4 – not to mention ‘super-proportional systems’ such as the Netherlands, Belgium and the Scandinavian countries (Casal Bértoa Citation2021). Yet in 2018–2020 the discrepancy between votes and seats seems to have generally decreased (−1), although this has not occurred homogeneously. Thus, for instance, Bolzano, Campania, Friuli-Venezia Giulia (FVG) and Veneto are now very close to being purely proportional systems. In the case of Bolzano this is due to the absence of a majority bonus in its electoral system. In the case of Campania, FVG and Veneto, this is instead due to the fact that their winning coalitions captured more than 60% of the vote and majority bonuses were not activated. In other regions disproportionality dropped much less significantly. In some cases, it even increased, not only because coalitions won by small margins and relied on majority bonuses to gain control of the councils but also due to the existence of thresholds, often damaging outsiders. Toscana is the most disproportional region. The ‘dominance’ of the PD and the left in that region (Vampa Citation2020) is not only a sign of a surviving political subculture (Ramella Citation2005) but it is also partly ‘constructed’ by the mechanisms of the voting system.

Table 3. Disproportionality in Italian regions (Gallagher index)

While, generally, disproportionality has slightly decreased, fragmentation, measured in terms of ENP, has remained at very high levels, both in terms of votes (ENPV) and seats (ENPS), as shown in . On average, we observe an ENPV of 7.1, a slight increase compared to the previous round. Looking at democratic nations in Western Europe, only highly fragmented systems such as Belgium and the Netherlands score higher on this indicator (Casal Bértoa Citation2021). Clearly, the proliferation of local and ‘personal’ lists already observed in the previous electoral cycle (Vampa Citation2015) continues to have an important impact on the dispersion of votes in regional elections. At the same time, when focusing on the composition of councils, it is not surprising that the ENPS (5.4 on average) is lower than the ENPV. Some smaller parties may have been unable to win representation due to thresholds, territorial distribution of votes/constituencies and the distorting effects of majority bonuses, which reward some parties, while punishing others. Still, we have instances of highly fragmented councils, particularly in the South – Campania and Sardinia being the two extreme cases.

Table 4. Fragmentation of votes (ENPV) and seats (ENPS) in Italian regions

Fragmentation may be assessed at the party-system level but also by considering ruling parties and opposition parties separately. Here, the application of the Laakso-Taagepera index is not limited to parties that are excluded from government (Maeda Citation2010) but it is extended to the political forces forming winning coalitions. In this way, it is possible to see whether fragmentation is symmetrically distributed between the two camps and whether this varies across regions and over time.

provides an overview of the level of ‘pluralism’ within ruling coalitions and oppositions in each region. It also shows how the situation has changed compared to the previous election cycle. Additionally, the third set of data gives us an idea of how large the gap between government and opposition is in terms of percentage of seats (competitiveness). Generally, it seems that, while the average advantage of regional majorities over oppositions has slightly increased (+2.4%), fragmentation affected the former more than it did the latter in the most recent election cycle.

Table 5. Ruling parties vs opposition: fragmentation and competitiveness

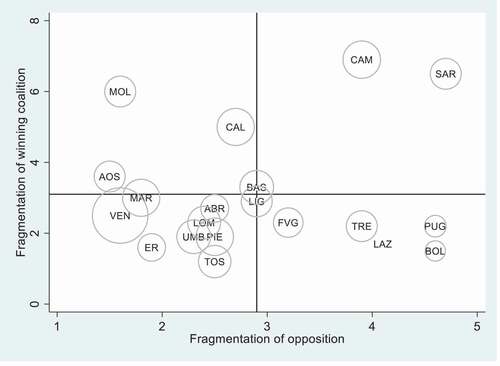

maps the regions based on the two fragmentation measures, and their markers are weighted by the size of the difference in seats between governing parties and opposition. Two reference lines divide the scatterplot into four quadrants based on the average values of fragmentation of the two political camps. Veneto has a particularly cohesive majority (more than in the previous cycle), which also faces a relatively unitary opposition. Yet the seat gap between majority and opposition is huge: almost 65 percentage points. The Venetian executive is virtually invulnerable to any external challenge in the legislative process and this partly derives from the popularity of the regional President, Luca Zaia. In the last election, Zaia Presidente, his ‘personal list’, was almost self-sufficient in the council and the seats of other centre-right parties, including the League, contributed to the formation of an ‘oversized’ cabinet (Lijphart Citation2012, 79–80).

Figure 3. Locating Italian regions on the map of party fragmentation: government vs opposition

Emilia-Romagna and Toscana are also characterized by homogeneous majorities, dominated by the centre-left PD, although their governments are less strong than the Venetian one in terms of share of seats controlled in the council. Among the regions considered here, Lazio is the only case of ‘minority’ government, with a negative difference between majority and opposition seats. Yet in this region, a relatively cohesive government, again dominated by the PD, faces a much more fragmented opposition. This has guaranteed the survival of the executive, thanks to ad hoc, partial agreements (Favale and Vitale Citation2018). It should also be highlighted that the data presented here refer to the situation on 31 December 2020. In March 2021, the centre-left coalition ruling Lazio established a formal alliance with one opposition party, the M5s, which joined the executive (Ghantuz Cubbe Citation2021). In Puglia and in the Autonomous province of Bolzano, majorities enjoy a smaller advantage in terms of seats but they are also less fragmented than the opposition. In Bolzano this is due to the strength of the regionalist Südtiroler Volkspartei (South Tyrolean People’s Party, SVP), which, despite gradually losing its political dominance, still remains by far the largest party of the region (Vampa and Scantamburlo Citation2020).

Molise and Calabria, two southern regions, are ruled by majorities that have a considerable advantage over the opposition in terms of seats, although not nearly as considerable as the one observed in Veneto. Yet these majorities, both on the right of the political spectrum, are much more fragmented than their oppositions. This is mainly due to the fact that, while in northern Italy the League has emerged as the clearly dominant party of the centre-right coalition, in the South its electoral growth has been accompanied – and, to a certain extent, constrained – by the resilience of Berlusconi’s Forza Italia (FI) and the rise of another right-wing populist party, Fratelli d’Italia (Brothers of Italy, FdI). Valle d’Aosta, a small alpine region with special autonomy, is also clearly in this sector of the map. This is mainly an effect of the electoral decline of the Union Valdôtaine (Valdostan Union, UV), a regionalist party which used to play a dominant role in building government coalitions (Massetti and Sandri Citation2012; Vampa Citation2020) but has recently suffered various splits.

In Sardinia and Campania both ruling coalition and opposition are more fragmented than the average. The impact of unstable and candidate-driven politics – characterized by so-called trasformismo – which is typical of most southern Italian regions, is further amplified by factors specific to these two contexts. In Sardinia – an island enjoying special autonomy – multiple regionalist parties and pro-autonomy (and even pro-independence) movements have crowded the whole political spectrum. In Campania, the incumbent leader of the executive, Vincenzo De Luca, a member of the PD, relied on an electoral strategy that was strongly centred on his personal charisma. Yet, rather than a Venetian-style minimalist coalition dominated by a ‘president’s list’, De Luca promoted the construction of an alliance between 15 different partners, of which a minority were recognizable as nationally relevant political parties. Each list acted instead as a separate link between the President and a loose and territorially dispersed system of prominent local leaders channelling votes to the coalition – what is generally defined as local notabilato (Floridia Citation2014). Additionally, De Luca’s centre-left majority confronted a divided opposition, with no dominant party on the centre-right (FdI, the League and FI obtained a similar number of votes and seats) and a declining, but still electorally relevant, M5s.

In sum, once again, it is difficult to identify patterns and trends that invest all Italian regions or a clear majority of them. The picture is one of extreme pluralism, which does not allow for any meaningful generalization. Electoral systems, despite almost unanimously rewarding winning coalitions with majority bonuses, rely on different thresholds and methods of seat allocation. By interacting with the increasingly disconnected strategies pursued by regional elites, electoral mechanisms have in turn resulted in multiple and highly distinctive patterns of democratic competition, none of which seems to stand out as particularly representative of the entire group or a sub-group of regions.

Who sits in regional councils and governments?

The question of how many parties and lists get access to representation and contribute to government formation is mainly addressed by referring to the data presented above. While the latter are relatively easy to gather, much less is known about the identity of regional policy makers. Yet, in order to have a comprehensive picture of how democracy works at the sub-national level, it is important to identify the key characteristics of the political personnel that are selected for public office.

The most recent study about regional political elites in Italy is the one by Cerruto (Citation2013), which mainly focuses on the 1990–2005 period and considers key variables such as the gender and age of the elected councillors. Interestingly, their average age has not changed significantly over the last fifteen years. It was 49 in 2005; it is 48 today. Therefore, the rise of the M5s, a new, young, anti-establishment political movement, does not seem to have led to a ‘rejuvenation’ of representation in Italian regions. What has changed, however, is the balance between men and women among the elected candidates. As shown in , there was a very slow increase in the share of women sitting in regional councils until 2005. We do not have comprehensive data for 2010 and 2015 but it can be noted that in 2020 this figure more than doubled, although it remains well below the share of women in the national parliament (36%).Footnote3

Figure 4. Women elected in regional councils from 1990 to 2020

Yet a look at the individual cases clearly suggests that there are significant differences across regions (). This is far from surprising given the region-specific dynamics already highlighted in the previous section. So, for instance, Emilia-Romagna and Veneto are the ‘youngest’ and most gender-balanced regions in Italy. Emilia-Romagna, in particular, has seen its share of female councillors grow by 32 percentage points since 2005, reaching 42% of the total. Veneto has also experienced a similar substantial growth. Toscana, Lazio, Umbria and Marche, all located in central Italy, also perform better than the average on this indicator. In northern Italy, Piedmont is particularly disappointing. Unlike most Italian regions, it actually saw a decrease in its share of female councillors and, together with Valle d’Aosta, it lags behind its northern Italian neighbours. In the South, the picture is also quite negative for women. With the exception of Molise, all southern Italian regions have less than one fifth of their council seats occupied by women. Basilicata has even seen a slight decline in their presence. Liguria is the region with the oldest political personnel, which is not surprising, given its demographics.Footnote4

Table 6. Age and gender of regional councillors (2018–2020)

There is also considerable territorial variation in terms of the political experience of regional representatives. includes three key indicators: 1) the share of councillors that have previous political experience at the regional level; 2) the average length of such experience (in years), and 3) the share of councillors that were in local (municipal or provincial) government before becoming regional representatives. The last column of the table aggregates the standardized scores of these three variables to obtain a general measure of councillors’ ‘sub-national political experience’. Emilia-Romagna has the highest aggregate score, meaning that its regional representatives are among the most politically experienced. More than half of them have already occupied positions in the regional administration and, on average, this experience has lasted 3.6 years. Also, almost all of them (88%) have previously held elective positions in local government.

Table 7. Political experience of regional representatives (2018–2020)

Interestingly, Lombardy has the lowest political-experience score. Looking at the specific scores, the region seems to have a particularly low percentage of councillors with previous regional experience. Although this region has been uninterruptedly ruled by a centre-right coalition for more than 25 years, the relatively recent collapse of Berlusconi’s FI and the rise of the League seem to have contributed to a new intake of less experienced councillors. Yet, generally, it is difficult to detect clear patterns that can be explained by political traditions, alternation in power and the usual north-south divide. For instance, in the South, councillors seem to have relatively high scores for political experience in Puglia and Calabria. However, while the case of Puglia can be explained by the level of political continuity in this region – governed by a centre-left coalition since 2005 – the same argument cannot be applied to Calabria, which has changed government at every election since 1995.

Moving from regions to parties and groups, several interesting results can be observed (). Councillors elected with the M5s are the youngest. This is not particularly surprising, given their very recent and reluctant transition from movement to party (Ceccarini and Bordignon Citation2018). They are also the most gender-balanced among the various groups, with more than one third of female elected officials. The PD also scores relatively well in terms of gender balance, although its representatives are, on average, older. Interestingly, on the right there is a clear difference between the League, on the one hand, and FI and FdI, on the other. The former has a sizable share of female representatives and is below the overall average age. The other two parties, in contrast, are much more male-dominated and older. FI in particular, which has experienced significant electoral decline and has been replaced by Matteo Salvini’s League as the largest party on the right, seems to rely on a core of old, male politicians. They also seem much more experienced than the representatives of the other two right-wing parties, as suggested by the political experience score in the last column in . The League is particularly weak when we consider councillors’ previous political experience at the regional level. In fact it is consistently outperformed by FdI, its populist radical-right ally/competitor. The latter, despite its more recent electoral breakthrough, relies heavily on post-fascist and conservative political traditions, which have never completely disappeared, particularly in southern Italy, and are still sources of recruitment for political personnel.

Table 8. Characteristics of regional councillors by party (2018–2020)

The PD is the most ‘experienced’ among the groups considered in . This is explained by the fact that this centre-left party has traditionally played a strong role particularly in central Italian regions. Of course, things have changed and even traditionally ‘red’ regions, such as Umbria and Marche, have moved to the right. Yet the PD still seems to retain its leadership in political professionalism at the sub-national level. The opposite can be said about the M5s, which has the lowest political experience score. However, when considering individual indicators, it is striking that 44% of M5s councillors – more than the League, FI and FdI – are not totally new to the institution, since they have been re-elected. Nevertheless, very few of them (15.2%) have a background in local government. Unlike all the other parties, the M5s does not seem to promote significant integration between local and regional political careers. This is because Beppe Grillo’s movement actually rejects, at least officially, the notion of ‘professional politician’, climbing the territorial ladder of public office. Instead, its representatives tend to stick to the level of government of their first election. Of course, the M5s is a relatively new and evolving organization and future convergence with the other political actors should not be excluded and, in fact, is likely to occur.

What is almost completely missing in the literature is a comprehensive description of the political class leading the Italian regions. Very little is known about members of regional governments (giunte). provides a general picture of the key characteristics of regional presidents and ministers (assessori) aggregated by regions. It emerges that they are generally older than councillors but, again, there are some differences among regions. Campania has the oldest government, with an average age above 60, while Calabria, Sardinia and the Autonomous Province of Bolzano have the youngest executives. When considering gender balance, Toscana dominates the ranking, followed by two other centre-left regions: Emilia-Romagna and Lazio. Among the regions governed by the right, Veneto, Umbria and, surprisingly, Sardinia are the ones with the most female ministers. Overall, women are still significantly underrepresented but to a lesser extent than in regional councils.

Table 9. Characteristics of regional governments (2018–2020)

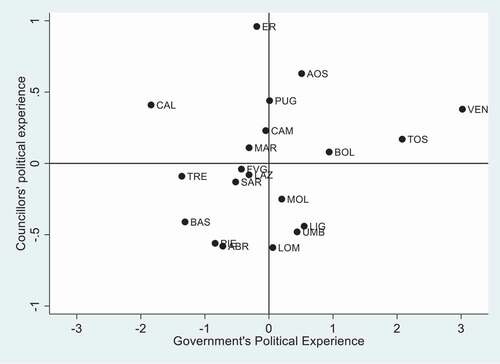

Political experience is captured by three sets of variables, whose standardized values are combined in an overall score (penultimate column, in ). Veneto’s executive is by far the most experienced one. It is followed by Toscana. On the other hand, Calabria has the least experienced government. If we intersect governments’ political experience with that of the councillors, we obtain a general map of ‘political professionalism’ of regional representatives (). The regions in the upper-right quadrant are those with high levels of political experience at both council and government levels. Veneto, Toscana, Bolzano and Valle d’Aosta are in this category. In all these regions, we can observe a high degree of political continuity (only recently disrupted in Valle’Aosta) and this seems to be accompanied by a resilient political class. The strength and politicization of regional identities in Veneto, Bolzano and Valle’Aosta might also have contributed to cementing a regionally-focused set of professional politicians. In the opposite quadrant, the lower left one, we see regions with less politically experienced personnel. In two cases, Basilicata and Trento, the ruling majority has changed for the first time in almost three decades with important effects on the composition of both council and executive. This has paved the way for the replacement of the old political establishment by a new one. Other regions, such as Abruzzo, Piedmont, FVG and Sardinia are classic ‘swing regions’: as the ruling majority has changed after every election, they have been characterized by high turnover of councillors and regional ministers.

Figure 5. Mapping political professionalism in Italian regional administrations (2018–2020)

However, it is still difficult to detect clear patterns. While low levels of political experience may indicate a lack of professional politicians in regional administrations, they do not tell us much about the competence of councillors and, even less so, government members. Indeed, the strengthening of regional executives vis-à-vis councils has also meant that the former tend to include non-partisan, non-political figures, who are directly (and almost exclusively) accountable to the President. These are often ‘experts’, who are expected to act in the public interest – rather than follow narrow political considerations – thus reflecting a ‘technocratic’ vision of policy making. The last column of shows that not all members of regional governments are selected from the pool of elected councillors. Therefore, strictly speaking, they might not have much political experience in regional administration, while still being competent in their assigned area of government. In other cases, non-elected members of government may still be partisan but have not run as candidates in the regional election. While not necessarily being experts, they are still autonomous from the council and remain strongly dependent on the support of the President, who has selected them. Generally, a large share of non-elected members of the government may be an indicator of looser links between executive and legislative branches of the regional administration. Lazio and Campania have the largest shares of non-elected assessori. Veneto and a number of smaller regions are instead representative of a more integrated system, where there seems to be a direct line of political promotion from council to government.

The variation in the composition of regional executives depends not only on cross-regional differences but may also be driven by the left-right orientation of the ruling majorities. divides regional government ministers into two categories – centre-right and centre-left – and compares them across the indicators considered above. The picture is that of older, more gender-balanced and more politically professional centre-left assessori. Interestingly, centre-left governments also seem to have larger shares of non-elected ministers. This may suggest that PD-led ruling majorities tend to combine political professionalism with a certain level of executive autonomy. On the other hand, centre-right governments, while being younger and more male-dominated, often consist of elected representatives who, however, tend to be quite politically inexperienced (i.e. they have only recently been elected).

Table 10. Characteristics of regional presidents and ministers by coalition (2018–2020)

Discussion and conclusion

The analysis presented above has considered a wide range of indicators in order to provide a comprehensive assessment of the type of representative democracy that emerged in Italian regions after the 2018–2020 electoral cycle. The picture is one of significant and growing territorial divergence, which seems to reflect marked regional idiosyncrasies. Yet, while it is difficult to draw overarching conclusions on how votes have translated into seats and governments in the most recent electoral cycle, some regions stand out more than others and can be regarded as interesting and clearly distinctive cases.

For instance, Veneto, a northern region governed by the right, has bucked the trend of increasing party fragmentation, while, at the same time, seeing an increase in the proportionality between votes and seats. Its government is among the most cohesive ones and relies on a very large legislative majority, mainly produced by the broad political consensus built around its successful President. The region is also administered by relatively young, gender-balanced and politically experienced personnel both at the council and executive levels. Toscana and Emilia-Romagna, traditionally governed by the left, are close to this model. Yet, majorities in these two regions are narrower and are more reliant on the disproportional effects of the electoral system than in Veneto.

Lombardy, a region that has been continuously ruled by the right and has often been regarded as a distinctive model of governance (Vampa Citation2016), provides a less consistent picture than the three cases mentioned above. To be sure, the fragmentation of its political landscape and ruling coalition remains at relatively low levels. Yet the region lags behind in terms of gender balance and the professionalism of its political personnel.

The two largest regions of the south, Campania and Puglia – despite both being led by strong centre-left presidents, who increased their popularity during the coronavirus pandemic – have not followed the same trajectory. They diverge in terms of proportionality, with the latter being significantly more disproportional than the former. Additionally, while the party system of Campania has reached record levels of fragmentation, that of Puglia is less crowded than in the previous election cycle. When it comes to the characteristics of their political personnel, however, the two regions seem to converge. Women are underrepresented in both contexts. In terms of the experience of their political personnel, they also present a mixed picture, as do most southern Italian regions.

Apart from Bolzano and Valle d’Aosta, which have very peculiar political systems dominated by regionalist parties, all the other regions are very difficult to classify. Some (Piedmont, FVG, Calabria, Sardinia, Liguria, Molise, Lazio) are ‘swing’ regions, characterized by recurring shifts in the political composition of councils and governments. Others (Umbria, Marche, Basilicata, Trento) experienced ‘earthquake’ elections in 2018–2020, which ended long periods of centre-left dominance.

The last point that should be made is that the composition of councils is not only determined by territorial factors but also by political competition, which, despite the proliferation of local and personal lists, is still dominated by state-wide parties. This article has therefore provided an assessment of how these parties have differed in terms of the characteristics of their elected representatives. Clearly, the PD and, more generally, the centre-left camp rely on an older, more politically professional and gender balanced political class. On the right, there seems to be a gap between the League, on the one hand, and FI and FdI, on the other. The former, particularly due to its recent electoral expansion to the South, relies on a relatively young, female-friendly, less politically experienced cohort of elected representatives. FI and FdI display a more traditional conservative outlook: older, male-dominated and with a relatively long political experience in local and regional government. Unsurprisingly, the M5s is the least experienced party, mainly due to the fact that its political personnel have entered regional institutions without previous involvement in local government.

Overall, sub-national representative democracy in Italy does not seem to have reached an equilibrium and is still in flux. What is clear is that Italian regional politics should no longer be analysed through the prism of national competition. The 2018–2020 electoral cycle has marked a further step in the direction of an increasingly fractured multi-level system, in which democratic processes are both vertically and horizontally disconnected. This lack of territorial integration is likely to have important implications, which future research will no doubt seek to uncover.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Davide Vampa

Davide Vampa is Senior Lecturer in Politics and International Relations at Aston University, Birmingham. He has published extensively on sub-national politics and public policy, political parties and populism.

Notes

1 For gender, age and political experience, the article also compares current data with those of previous electoral cycles provided by Cerruto (Citation2013).

2 Anagrafe degli amministratori locali eregionali, https://dait.interno.gov.it/elezioni/anagrafe-amministratori

3 See data provided by the World Bank, https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SG.GEN.PARL.ZS

4 According to the Istituto Nazionale di Statistica (ISTAT, https://www.istat.it/en/), Liguria has the highest share of people aged 65 across all Italian regions.

References

- Basile, L. 2015. “A Dwarf among Giants? Party Competition between Ethno-regionalist and State-wide Parties on the Territorial Dimension: The Case of Italy (1963–2013).” Party Politics 21 (6): 887–889. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1354068815597574.

- Bolgherini, S., and S. Grimaldi. 2017. “Critical Election and a New Party System: Italy after the 2015 Regional Election.” Regional and Federal Studies 27 (4): 483–505. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13597566.2017.1343718.

- Calossi, E., and L. Cicchi. 2018. “The Italian Party System’s Three Functional Arenas after the 2018 Election: The Tsunami after the Earthquake.” Journal of Modern Italian Studies 23 (4): 437–459. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/1354571X.2018.1500215.

- Casal Bértoa, F. 2021. “Database on WHO GOVERNS in Europe and Beyond.” PSGo. Available at: whogoverns.eu

- Ceccarini, L., and F. Bordignon. 2018. “Towards the 5 Star Party.” Contemporary Italian Politics 10 (4): 346–362. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/23248823.2018.1544351.

- Cerruto, M. 2013. “La classe politica regionale.” In Il divario incolmabile, edited by S. Vassallo, 89–108. Bologna, Italy: Il Mulino.

- Chiaramonte, A., and L. De Sio, eds. 2014. Terremoto elettorale. Le elezioni politiche del 2013. Bologna: Il Mulino.

- Favale, M., and G. Vitale. 2018. “Regione Lazio, Zingaretti senza maggioranza e Pirozzi apre il giro di avance.” La Repubblica, 7 March. https://roma.repubblica.it/cronaca/2018/03/07/news/regione_lazio_zingaretti_senza_maggioranza_e_pirozzi_apre_il_giro_di_avance-190662331/

- Floridia, A. 2014. “Il voto amministrativo nel Centro-sud: L’apoteosi del micro-notabilato.” In L’Italia e L’Europa al bivio delle riforme: Le elezioni europee e amministrative del 24 maggio 2014, edited by M. Valbruzzi and R. Vignati, 433–447. Bologna: Istituto Carlo Cattaneo.

- Gallagher, M. 1991. “Proportionality, Disproportionality and Electoral Systems.” Electoral Studies 10 (1): 33–51. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/0261-3794(91)90004-C.

- Ghantuz Cubbe, M. 2021. “Lazio via libera del Pd all’accordo coi 5S: “Ma nessun dialogo”.” La Repubblica, 3 March. https://roma.repubblica.it/cronaca/2021/03/03/news/lazio_via_libera_a_larghissima_maggioranza_del_pd_all_alleanza_coi_5s-290082496/

- Hopkin, J. 2009. “Decentralization and Party Organizational Change: The Case of Italy.” In Territorial Party Politics in Western Europe, edited by W. Swenden and B. Maddens, 86–101. Basingstoke and New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Karremans, J., G. Malet, and D. Morisi. 2019. “Italy – The End of Bipolarism: Restructuration in an Unstable Party System.” In European Party Politics in Times of Crisis, edited by S. Hutter and H. Kriesi, 118–138. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Krook, M. L., and D. Z. O’Brien. 2012. “All the President’s Men? the Appointment of Female Cabinet Ministers Worldwide.” The Journal of Politics 74 (3): 840–855. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022381612000382.

- Laakso, M., and R. Taagepera. 1979. ““Effective” Number of Parties.” Comparative Political Studies 12 (1): 3–27. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/001041407901200101.

- Lijphart, A. 2012. Patterns of Democracy. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Maeda, K. 2010. “Divided We Fall: Opposition Fragmentation and the Electoral Fortunes of Governing Parties.” British Journal of Political Science 40 (2): 419–434. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S000712340999041X.

- Mariucci, L. 1999. “L’elezione diretta del Presidente della Regione e la nuova forma di governo regionale.” Istituzioni del federalismo 6: 1149–1164.

- Massetti, E. 2018. “Regional Elections in Italy (2012–15): Low Turnout, Tri-polar Competition and Democratic Party’s (Multi-level) Dominance.” Regional and Federal Studies 28 (3): 325–351. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13597566.2018.1428568.

- Massetti, E., and G. Sandri. 2012. “Francophone Exceptionalism within Alpine Ethno-regionalism? the Cases of the Union Valdôtaine and the Ligue Savoisienne.” Ligue Savoisienne. Regional and Federal Studies 22 (1): 87–106. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13597566.2011.652094.

- Ramella, F. 2005. Cuore rosso? Viaggio politico nell’Italia di mezzo. Rome: Donzelli.

- Tronconi, F. 2010. “The Italian Regional Elections of March 2010. Continuity and a Few Surprises.” Regional and Federal Studies 20 (4–5): 577–586. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13597566.2010.541670.

- Vampa, D. 2015. “The 2015 Regional Election in Italy: Fragmentation and Crisis of Subnational Representative Democracy’.” Regional and Federal Studies 25 (4): 365–378. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13597566.2015.1074073.

- Vampa, D. 2016. The Regional Politics of Welfare in Italy, Spain and Great Britain. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Vampa, D. 2020. “Developing a New Measure of Party Dominance: Definition, Operationalization and Application to 54 European Regions.” Government and Opposition 55 (1): 88–113. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/gov.2018.12.

- Vampa, D., and M. Scantamburlo. 2020. “The ‘Alpine Region’ and Political Change: Lessons from Bavaria and South Tyrol (1946–2018).” Regional and Federal Studies. Latest Articles. https://doi.org/10.1080/13597566.2020.1722946.

- Vassallo, S., ed. 2013. Il divario incolmabile. Bologna: il Mulino.

- Wilson, A. 2015. “Direct Election of Regional Presidents and Party Change in Italy.” Modern Italy 20 (2): 185–198. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13532944.2015.1024213.