ABSTRACT

This paper is based on research with environmentally engaged trade unionists in India. It follows their trajectories into the trade union and explores their environmental engagements. A short presentation of the history of Indian trade unionism, aims to understand its ‘multi-unionism’. Analysing three exemplary life-histories of unionists, their motivations to engage in unions and their relationships to workers and to poor people, three models of perceiving the labour-nature relationship are offered: the container model, nature as a mediator of survival, and the nature-labour alliance. I show that the way in which unionists perceive the labour-nature relationship is shaped by their practices and influences their environmental policies. Furthermore, trade unions who seek alliances with other social movements on equal terms, develop a more comprehensive perception of the labour-nature relationship and thereby the development of more wide-ranging environmental policies. I conclude suggesting that the conditions enabling a more comprehensive perception of the labour-nature relationship could become possible if workers along the value chain could collaborate to learn from each other about their working conditions and the natures they transform.

Introduction

The question I ask in this paper is how environmentally engaged unionists perceive the labour-nature relationship and how this might influence their environmental policies. The reason this is a relevant question has to do with the fact that the destruction of the life support system of the earth through production processes (climate crisis, loss of biodiversity, acidification of oceans, soil degradation, water scarcity, etc.) are not experienced as direct effects of a specific production process. While the effects of the climate crisis are now also increasingly experienced in countries of the Global North, they cannot easily be related to specific production processes -or to the climate crisis in general. Unions have traditionally fought against health and safety threats at the workplace and its surrounding communities. In order to design effective environmental policies towards the global threats of environmental destruction the labour-nature relationship needs to be understood in a way that transcends everyday work experiences. Therefore, the question how unionists perceive this relationship is relevant for the formulation of environmental union policies.

Especially since the Paris agreement (2015), which in its preamble stated that a solution of the climate crisis needs to include a ‘just transition’ for workers, this concept has shifted into the centre of trade union policies and academic debates. The latter discuss just transition in terms of its breadth and depth (Stevis, Uzzell, and Räthzel Citation2018), its proactive or reactive (Stevis and Felli Citation2015), protective, or transformative (Sweeney and Treat Citation2018) character.

Trade union action develops through exogenous processes like the destruction of the environment itself or political pressures as well as endogenous processes like pressures from their members, the ways in which decisions are taken, their organisational structures, the history of their creation. A range of such processes and conditions of environmental union policies – or the lack of them – have been analysed. They include the economic sector in which unions operate, the societal, political and economic pressures they experience, the histories, which define their political ambitions (Felli Citation2014; Farnhill Citation2016; Snell and Fairbrother Citation2010; Vachon and Brecher Citation2016; Morena, Krause, and Stevis Citation2020). What has not been researched is whether, given the globalisation of environmental destruction, unionists’ perceptions of the labour-nature relationship influence just transition policies.

In the following section I will present a theoretical framework to analyse perceptions of the labour-nature relationship. This will be followed by a description of our research project, an analysis of our material discussing three models of perceiving the labour-nature relationship and a conclusion summarising the way in which different perceptions emerge and what we can learn from this for environmental labour policies.

The inextricable Society-Nature, Labour-Nature Relationship

The crisis of human and extra human life, indicated by the climate crisis, the loss of biodiversity, the acidification of oceans, the dwindling of water supplies can act as a reminder that nature is not something out there, but, as Moore aptly puts it, ‘Humans simultaneously create and destroy environments (as do all species), and our relations are therefore simultaneously – if differentially through time and across space – being created and destroyed with and by the rest of nature.’ (Moore Citation2015, 152). Like Moore a number of authors have sought to overcome the binary between humans and nature, speaking about ‘social nature’ (Castree and Braun Citation2001) or natureculture (Haraway Citation2008). These concepts do not account for the labour-nature relationship. We find this in Marx’ definition of labour as: ‘ … in the first place, a process in which both, the human beingFootnote1 and nature participate, and in which human beings of their own accord start, regulate, and control the material re-actions between themselves and nature. (…) By thus acting on the external world and changing it, they at the same time change their own nature.’ (Marx Citation1998). Since nature is at the same time the opposite of and part of ‘human’s own forces’ and since both, internal and external nature transform each other in the process, the opposition between human nature and external nature is transcended. It is through the labour process that the internal nature of humans, and the external nature are inextricably connected.

This insight and experience has been all but lost in the course of industrialisation. This does not mean that unions are not and have not been unparalleled defenders of their members’ health and safety at the workplace and within their communities (Rector Citation2014; Barca and Leonardi Citation2018; Pellow Citation2007). In their beginnings unions have also been active defending nature as a place of enjoyment and recreation (Räthzel and Uzzell Citation2013). Through struggles against health hazards of production and defending nature as a place of recreation nature becomes labour’s ‘Other’. It is either the threatened object of production or the healing place beyond the realm of work. The globalisation of environmental destruction poses the question of the labour-nature relationship urgently. To stop the destructive processes of production it is necessary to see that every production process consists of transformed nature. With nature perceived to be outside of work, there develops the dilemma of having to protect either work or nature (Räthzel and Uzzell Citation2011). The spatial disconnection and the asynchronism between extracting materials from nature, creating the means of production and the effect of these processes on the societal relations with nature, requires a holistic perspective of the labour nature-relationship that transcends its perception as the object of production or the place of recreation. Such a holistic perspective can serve as a basis for the development of transformative environmental policies – that is the hypothesis. This is why we analysed our data for the way in which union environmentalists perceived the labour-nature relationship.

The Research Project and its Methodology

This paper is based on a research project that investigated the role of individuals in transforming organisations, using trade unions and their environmental policies as a case in point. To understand why and how unionists became environmentally engaged we conducted 120 life-history interviews in Brazil, India, South Africa, Spain, Sweden, and the UK. In order to conduct an in-depth analysis accounting for the socio-historical contexts of life-stories we need to present each country separately.Footnote2

The usage of life-histories

Life history interviews enable us to see the social, economic and historical influences on individuals over their lifespan. Interviews are a co-construction between the interviewer and the interviewee (Holstein and Gubrium Citation2003). This does not mean that life-stories are inventions but rather that different aspects of a respondent’s life will be told differently in different contexts. Life-histories provide the opportunity to learn something about the ways in which people experience themselves as actors and act upon what they see as limitations, success or failure.

Data Collection

Since the people we interviewed where public personalities and used to give interviews the project was exempt from applying for formal ethical approval from the Swedish Ethical Committee (Etikprövningsmyndigheten). We followed the ethical regulations for research in Sweden by explaining the aims of the project to the interviewees in written form. The document also stated that the interviewee could end the interview at any time and only needed to answer the questions they wanted to. It was agreed that every effort would be made to keep the interviewee anonymous. Only project members and the transcriber would read the interviews, which is why our data cannot be shared.

Interviewees were asked to relate their life story beginning from the date of their birth and including the familial, spatial and political contexts in which they grew up. They were also asked about their way into the trade union movement and their environmental engagement. We conducted 30 informative and life-history interviews with trade unionists, representatives of small-scale fisherfolk and environmentalists.Footnote3 They lasted between 1½ – 3 hours, were recorded with the interviewees’ agreement and transcribed. 30 interviews do not seem many given the size of the country and the number of its unions. However, we made sure to include not only the main national unions but also associations organising informal and small independent workers. The interviewees were leading members of their respective organisations and therefore represent a significant perspective within them.

Data Analysis

To find the ways in which our interviewees perceived the labour-nature relationship I selected all the instances in which unionists talked about nature or the environment using the MAXQDA system. On the basis of the coded utterances and using the concept of the labour-nature relationship discussed above I constructed ‘models’ representing the degree to which nature is seen as an integral part of the labour process. I then went back to the interviews to understand how the life-histories of unionists, their practices and worldviews might have influenced their perceptions.

I found predominantly three perceptions of the labour-nature relationship in our Indian material: the environment as container, as a mediator of life, and a holistic view which I call, in reference to Bloch (Citation1973), the nature-labour alliance. Each of the unionists I discuss represents one of these perceptions and can therefore be regarded as exemplary (Flyvbjerg Citation2006). Case studies are often misunderstood because they are not a basis for statistical generalisations. As Flyvbjerg argued, they aim to understand the complexities and multifaceted details of real-life situations: ‘ … for the development of a nuanced view of reality, including the view that human behavior cannot be meaningfully understood as simply the rule governed acts found at the lowest levels of the learning process and in much theory.’ (ibid. pp 223) Case studies can give us an insight into the range of human capabilities (Portelli Citation1997). By understanding people’s potentials and the conditions under which they develop we can imagine how desirable practices could be generalised, re-created under different conditions. Thus, we shift the question of whether a certain practice occurs generally to the question whether and under which conditions it might become generalisable.

Three Perceptions of the Labour-Nature Relationship

I begin with a summary of labour relations in India to understand the individual histories of our protagonists. I then present and discuss the three perceptions of the labour-nature relationship explaining how they began to take notice of environmental and ecological issues.

Labour and Industrial Relations in India

One specificity of the industrial relations in India is the proportion of workers in informal employment which was 83% in 2009/2010. This includes informal employment in the informal as well as in the formal sector (ILO, 2018). Traditional trade unions organise mostly workers in the formal sector, though some have tried to reach out to informally employed workers during the past 10 years (Agarwala Citation2013).

The industrial working class in India emerged after 1919 as a result of an industrial development which was hampered because of India’s colonial history. Goods produced by artisans and craftsmen in India were exported to Britain with high profits. However, the industrial development in Britain destroyed handcraft industries in India, which became a market for machine-made imported goods and an exporter of raw materials. Millions of artisans and craftsmen were left jobless due to the influx of cheap industrial goods. The destruction of the handicrafts was not paralleled by jobs in industries. Artisans were forced to move to the villages, becoming mostly landless labourers.

In the 1830s British rulers began the construction of railways reducing India to a supplier of raw materials and a market for British goods. Some auxiliary processing industries were developed. Because of the agricultural crisis, peasants and handicraftsmen were forced to migrate back to the cities as suppliers of cheap labour for those industries. Under British rule the plantation industry was developed (tea, coffee and jute industries) and by 1860–1870, these industries began to grow. Every effort was made not to allow any independent development of Indian industry. Therefore, the trade union movement in India only took shape after the first world war.

Another reason for the delayed formation of trade unions was the lack of cohesiveness among the workers who were divided by religion, caste, and region. Social reformers and political leaders became involved in developing an industrial culture that proved essential for the development of trade unions. It was through the Swadeshi (indigenous goods) Movement, part of the Indian independent movement and the largest pre-Gandhian movement in India, that the working class was first brought together. Its major strategy was to boycott British products to raise the demands for goods produced in India (Trivedi Citation2003).

The first recorded move towards a trade union was made by N.M. Lokhanday in 1890 organising ‘The Bombay Mill Hands Association’. It brought public attention to the grievances of the textile workers aiming to modify the Factories Act of 1881 for the benefit of the workers. Similar associations were formed elsewhere, mostly led by social reformers (Raveendran, Citation1992).

The immediate post World War I period (1918–1922) saw the birth of a national Indian Trade Union Movement favoured by expectations of a new social order, industrial and economic unrest, the Russian revolution in 1917, the formation of the International Labour Organisation (ILO) in 1919 and the Swaraj (self-determination, self-rule) Movement between 1920–22.

The number of industrial workers increased from 959,000 in 1914 to over 1,300,000 in 1920 (Chattopadhyay, Citation1995). British run textile mills in Bombay made enormous profits (Dutt, Citation1949) while prices went up and wages lagged behind and the workload increased. This led to strikes in different parts of India, where workers demanded higher wages and a reduction of working hours. Nation-wide strikes of textile workers, workers in the dock areas, railways and other areas of transportation took place (Chattopadhyay, 1995). Inspired by their success, some strike committees became trade unions. The first organized trade union in India, ‘The Madras Labour Union’ was formed by B.P.Wadia in 1918 (Rao, Citation1939).

The ILO came into existence with the Peace Treaty of Versailles in 1919, recognising that peace was only possible if it was based on social justice. It aimed to regulate working time and labour supply, prevent unemployment, provide a living wage and social protection for workers, children, young persons and women. (https://www.ilo.org/global/about-the-ilo/history/lang–en/index.htm). It has influenced India’s labour movement, labour legislation and labour policy (Raveendran, 1992) supporting the trade union movement by providing training, literature and resources. When the first ILO conference was held in 1919 in Washington, there was no central association of Indian trade unions and hence the government nominated a delegate without consulting any trade unions. Unionists saw this as an affront and organised a conference of representatives of 64 trade unions (claiming a membership of 1,408,500) in Bombay where the All India Trade Union Congress under the chairmanship of Lala Lajpat Rai (AITUC, 1973) was founded.

Rai’s presidential address emphasized the need for class consciousness, for international proletarian brotherhood and for a place of nationalism in the class outlook, thus connection the trade union movement to the national liberation movement (Dange, Citation1973). Mahatma Gandhi’s involvement in the trade union movement, which began with a strike in Ahmedabad in 1918, (Nanda Citation2004) inspired many young trade union leaders.

AITUC secured the representation of Indian workers at the ILO conference of Geneva in 1920. It provided a centre of coordination and representation for the trade unions scattered over India and mobilized labour for the Swaraj movement. Prominent Indian National Congress leaders became activists within AITUC. However, conflicts between unionists supporting national liberation and communist and socialist unionists led to subsequent splits and mergers during the thirties and forties. The result was that multi-unionism came to characterize the Indian trade union movement, splitting it along party lines until today. The main national unions are AITUC, affiliated to the Communist Party of India, Indian National Trade Union Congress (INTUC), affiliated to the Indian National Congress Party, the Bharatiya Mazdoor Sangh (BMS, Indian Labour Union), affiliated to the right-wing Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP, Indian People’s Party), currently in power, the Centre of Indian Trade Unions (CITU), affiliated to the Indian Communist Party (Marxists), the Hindu Mazdoor Sabha (HMS, Hindi Workers’ Assembly) defining itself as socialist. There are twelve recognised national trade unions in India. Not all of them are affiliated to political parties. Examples are the Association of Self Employed Women (SEWA), and the New Trade Union Initiative (NTUI), a small union intent on bringing workers of the formal and informal sectors together. The landscape of Indian trade unionism is further complicated by the fact that there are countless unions which operate on factory level only. Multi Unionism weakens the trade union movement by creating inter- and intra-union rivalries, deteriorating the effectiveness of collective bargaining (Raveendran, 1992).

A substantial number of workers in Indian Industries are women who have historically been involved in trade union activism (Chattopadhyay, 1995). Women in mines, textiles, fisheries, bedi, tobacco, tanneries, and construction are not only paid much less compared to their male counterparts, but they face serious health hazards which remain unaddressed. In fisheries they stand 10–12 hours at a stretch in water without gloves or shoes. Women working in mines have no protection from dust and often suffer from tuberculosis. There is a huge neglect of issues concerning women and health in trade unions and the lack of women’s leadership at the national level is testimony to the lack of gender parity in the trade union movement. Therefore, we find new unions, which specifically address the needs of women workers, like the union of construction workers, which is one of our cases below.

As Indian political parties fail to address basic issues of employment, living wages, food security etc., trade unions feel often unable to address environmental issues. Some unionists we interviewed argued they could not deal with climate change because of the more urgent issues of poverty, others considered climate change to be an invention of the West aimed at hampering economic development of countries in the Global South.

The three unionists I present here belong to unions which are politically independent and have developed environmental policies: Manoj from the New Trade Union Initiative, Gini from the construction workers union: Nirman Mazdoor Panchayat Sangam, and Pedru from the Kerala Independent Fish Workers Federation, Thiruvananthapuram. Due to the promise of anonymity we cannot detail these persons’ positions in the unions. All names are pseudonyms.

Entries into Environmental Practices

In a first step I present the ways in which the environment became a relevant concern in the life histories of our interviewees. I then explicate the perceptions of the labour-nature relationship that are implicit in their accounts, creating three models of this relationship. I will be talking about the environment as opposed to nature because that is the language used by our interviewees. Under this term unionists speak about water pollution, health risks at work, deteriorating natural conditions, and other forms of environmental degradation. Seldomly do they talk explicitly about the climate crisis.

Manoj, New Trade Union Initiative

Asked about the beginning of his engagement for environmental issues, Manoj answers:

By the late 80s or early 90s, if you had the kind of political roots that I had, you would reject the environment (…) Whether it is the big dam or the small dam, the nuclear plants (…) or the small battles against the large hydro-projects, I was, if you wanted to say it, on the wrong side.

The last ten years, the left-wing scientists started to unbundle and educate us. We need to pay tribute to them rather than the generation of unipolar environmentalists. (…) I think that is really what inspired me to begin addressing these issues. (…) I think the environmentalists need to win us over by convincing us and not steamroll on us.

Knowledge about ecological issues has not led Manoj to aim for an understanding with environmental movements. Learning about ecological issues theoretically it was also through theoretical reflections that Manoj decided to enter the trade union movement:

What took me to the trade union was really the collapse (…) of the Soviet Union. So, if I look at defining moments, I grew up in the nationalist India, the failure of the left, the shadow of the emergency. What I learned from the collapse of the Soviet Union was that we need to rebuild the left. (…) Lenin’s metaphor that trade unions are the school of learning politics is what told me that what I ought to be doing is not becoming a political economist but to work with the trade unions. So, I finished my degree and came back [from studies in the UK and Europe] and that is how I got into trade unionism.

Manoj sees the trade unions as an instrument for creating a larger movement that will transform society. His interpretation of what constitutes the rebuilding of the left is based on an understanding of the working class as a central change agent. Immersing himself in trade union practices, he began to experience the importance of environmental degradation for workers:

Just getting into urban areas, getting into working class shanty towns and also addressing their questions … from original shop floor struggles I cut my teeth originally in the old factory sector dealing with issues of industrial waste, safety and hazardous issues, then dealing with the informal sector.

Manoj remains within the realm of workers’ issues at the workplace level and as a consequence, his views are shaped by the ‘job vs. environment’ dilemma.

But if you present it as a black and white (…), ‘the plant has to be shut’, then obviously there’s going to be resistance and then, you can interpret that resistance in the most negative, obstructive, obdurate way as if workers are just obstructionist, only interested in their livelihood. Yes, they’re interested in their livelihood. They are also parenting the next generation! We are protecting the environment for whom? For the next generation. And for coming generations. These people (…) beget the next generation. Are we going to leave the next generation hungry? So, then we have people with low mental capacities because their parents were starved and have a wonderful environment (…) we’re talking poppycock there.

Manoj is turning one of the main arguments of environmentalists around, namely that the climate has to be protected for the next generations, arguing that the next generations will suffer if the environment is protected. Researching the chain of causes for safety and hazardous issues, Manoj could have arrived at understanding the larger picture connection nature, people and work. So why does he think that caring for the environment would leave people hungry? This conflict that Manoj is presenting is the central conflict still haunting the labour movement globally, particularly in poor countries like India. No campaigns for climate jobs or predictions that ‘green’ jobs will outnumber the jobs being lost by environmental measures have so far convinced a significant number of workers that the climate crisis should take pride of place on their agendas.

… many of them [people, with whom he prepared for a COP meeting] were rooted in rural areas and they would say to us that they felt that the transformation must begin and (…) they would say we need to address the water issue. Now, a construction worker in Delhi city, who probably travels 20 or 25 kilometres to a site, gets water for an hour in the morning and an hour in the evening (…) and has to fill up for the rest of the day … You’re not going (…) to convince him or her to worry about what’s happening to the water resources in the countryside.

Manoj identifies with the urban workers he represents. In a conflict with them and other workers he chooses to associate himself with them as opposed to seeking solidarity with the related water issues of country and urban workers. We call Manoj’s perception of the labour-nature relationship which also guides many environmental unionists in the global North the container model.

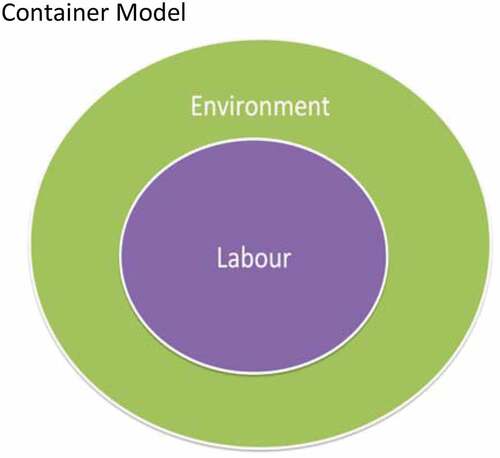

The Container Model

I arrive at the ‘container model’ explicating the labour – nature relationship implicit in Manoj’s account. The environment is seen as a container within which labour is situated. There are no intrinsic relationships between the container and its content. If workers would care for the container, this perception suggests, they will lose sight of their own needs and damage themselves. Manoj transfers this image of labour being independent from nature to the relationship between urban and rural, reproducing a policy that pitches urban against rural workers .

Gini, Nirman Mazdoor Panchayat Sangam

Asked about how her interest in environmental issues arose, Gini replies:

In the 90’s (…) there were a number of issues relating to pollution (…) to water ways (…) because at one level we got involved with the fishermen issues, then it’s very closely connected with the ecological question (…) you can’t ignore it. (…) even with the construction workers, even from the beginning, 79 −80, I got actively involved in occupational health issues. Just one kind of environmental issue.

Gini began to work with environmental issues when they became relevant to the people whom she was helping to organize. In retrospect, she defines their health issues as a ‘kind of environmental issue’. At the time they belonged to the context of working conditions. Other environmental issues become part of Gini’s work through the needs of organisations her union connects with.

We branched out in many ways. The women’s movements were also there, and we could involve the women in the slum issues, (…) unorganized workers from various categories were brought together and then the slum issues were basically causing riots and then certain environmental issues, the water issues (…) cropped up. Drinking water, waterways all these issues were brought up in the 80’s to 90’s. That was another parallel activity that we did. And then we founded another union for other unorganized workers: contract labour and many other categories of workers.

Things ‘cropped up’ or ‘were brought up’, is Gini’s expression to explain how her work began to include environmental issues. It was less a conscious decision, or the result of theoretical insights, but derived from the needs of workers. Wherever people voiced their needs, they were included into the union’s struggles:

In 84, we moved from the slum dwellers to the fishermen, because that was the time the slums were getting demolished. They removed the catamarans from the beach, in the name of beautification. (…) there are a lot of fisher settlements (…) they keep their fishing equipment on the beach. But all that was wiped out because the government probably wanted a five-star hotel to be put on the Marina, so there was a huge agitation by the fishermen. We were part of the agitation, and there was firing, 5 people were killed. (…) we (…) combined the slum issues with the fish workers, so we had joint rallies. But that was a very important experience, which helped me to understand the fisher people’s issues, which are (…) connected with the ecological issues.

Our research with European unionists (see references) showed that while some created alliances with environmentalists, they would rarely take actively part in other struggles or see it as their task to found new unions. Yet, it is the broadening of alliances and struggles that opened Gini’s eyes for environmental issues.

An involvement of unions beyond the immediate interests of their members has been discussed as social movement unionism. It is defined by its internal democracy, its inclusion of members into the decision making process, alliances with other community organisations and a concern for broader societal issues (Moody Citation1997). It is hoped that social movement unionism could become a strategy for union renewal overcoming the blows that neoliberalism, precarious labour and the shift of jobs from sectors with high trade union representation to sectors in which they played a more marginal role (Fairbrother and Yates Citation2003).

There has also been criticism of how trade unions reached out to other social movements: ‘labour approaches social movements as “others” with whom to ally politically, rather than recognizing them as often representing (…) parts of the working class’ (Gindin Citation2015: 112; Tait, Tzintzun, and Recorded Books Citation2016). In Gini’s account the social movements she brings together are seen as equal and strengthening each other: we found that the workers had so many things to share.

It is not only this belief that guides Gini’s practices but also the peculiarity of her union, organising informal workers, 30% of them being woman, which facilitates broader alliances: since the employers of informal workers keep changing, they address their demands predominantly to the state and this joins different groups together.

Whether the union aims to secure decent wages and working conditions, or whether they ally with slum dwellers or fish workers, in all these struggles the demands are directed towards the regional or central state:

… Indian informal workers are using their power as voters to demand state responsibility for their social consumption or reproductive needs (such as education, housing, and health care). They have operationalized this strategy through tripartite welfare boards that are implemented at the state level. In contrast to traditional labor struggles, informal workers’ movements today include the mass of illiterate men and women and employees in public and private enterprises. They organize by neighborhoods, register as NGOs and trade unions, and use nonviolent tactics (Agarwala Citation2013, 67).

Bringing different movements together means bringing a greater mass of people together, whose voting power attracts political parties. These alliances provide also a learning space for all to understand how their respective needs are connected. For informal workers, there are no pre-given definitions of workers’ interests. This is also in part because, as in the case of Gini’s union, women constitute a significant part of informal workers:

Informal workers are also addressing issues arising from the intersection of class and gender. Women workers have long fought to expose the interdependence between reproductive and productive work, as well as between the private and public spheres. Informal work, which has until recently been considered ‘feminine,’ sits at these very intersections. (Agarwala Citation2013, 16)

This inclusive approach can also be understood as originating in Gini’s individual trajectory. Her mother was a surgeon and her father, she says, a ‘freedom fighter’ in the independence movement, first as Marxist, later becoming a Gandhian. Gini doesn’t recall being interested when her father took her meetings. She preferred science and studied physics. After she had completed her M.Sc. and registered for a PhD, an event influenced her trajectory:

That was the time Jaya Prakash NarayanaFootnote4 came to the university, so there was a big meeting on the campus. JP came and addressed the students. He can inspire the students in a big way. (…) He would call upon us to go to the villages and factories and slums and work with the people. That I think, somewhere, it had made an impact on me, which I didn’t realise at that time.

Gini eventually left university and started to work in the slums, then became a teacher, took part in organising a women’s organisation of teachers, and through a research on construction workers became involved in founding the union of construction workers. The historically significant engagement of middle-class individuals for ‘the poor’, which included founding and joining unions, is reflected in our material, where unionists explained their engagement as their wish to ‘help the disadvantaged’. In Gini’s account workers, slum dwellers, and fish workers, initiated their campaigns and Gini’s union connected them. Environmental issues enter into the union agenda through existing struggles and thereby define workers’ interests. Gini’s life trajectory led her to become an activist in support of ‘the people’ an engagement which has to be understood against the structure of the Indian workforce, where the vast majority is composed of informal workers, who do not fit into the conventional definition of the working class as it has been developed in industrialised countries.Footnote5

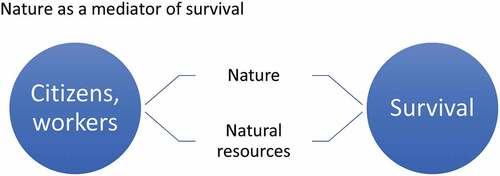

Having become and activist to support ‘the people’, engaging in the women’s movement, in the slums, and founding a trade union are for Gini elements of a broader struggle. I called her perception of the labour-nature relationship, nature as a mediator of survival.

Nature as a Mediator of Survival

For Gini nature becomes a mediator of survival, since waterways and sea wealth are fundamental conditions for the survival of the people whose interests are included in the union’s struggle. This perception is developed through practices that connect a range of social groups as opposed to pitching them against each other as in Manoj’s case .

Pedru – Fisherfolk organisation

Pedru’s father was a fisher and his mother sold fish. He and his parents decided that he should not step into their footsteps, but study. He studied engineering but came back to his village and became one of the leaders of the fisherfolk association. Asked why he came back he answers: I don’t know. Because (…) from my childhood on I needed to help others. (…) Some influence from the Bible. Pedru leads the fisherfolk organisation, with which Gini cooperates. For him, the fish workers’ struggles are by definition struggles for the environment. He relates how his trade union fought against a law that allowed big fishing companies to use the method of ‘trawling’ by which large nets are used to swipe the seabed. This has mainly two environmentally damaging effects: the by-catch, catching fish that can either not be marketed or is protected, and the destruction of the seabed killing the breading fish:

we need to fight against (…) trawling. This is the protection of (…) the environment, this is the protection of the fish level.

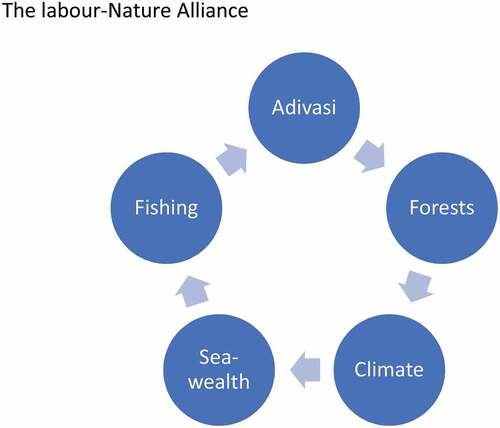

(…) we need to realize, what is the environment? What is our earth? What is our surrounding? (…). We need to protect the fish wealth, that is the food chain. We need to protect the environment, that is our livelihood. (…) that is why we are collaborating with other organisations, we need to protect the tribals, the Adivasis. We need to protect the forests, otherwise you will not get rain timely and then you will not get sea wealth. (…) So, this is the chain, we are part of this environment.

Pedru answers shortly, when it comes to questions about his life, but it becomes clear that he, like Gini, is driven by a wish to help the poor. The poor of whom he used to be a part. From talking about himself, he quickly comes back to his passion, the relationship between people and the environment, a vision in which he sees all living things connected, Adivasis, forests, fish and fisherfolk. Adivasis are tribal people in India, who live predominantly in forests and whose livelihoods have been severely threatened by deforestation and plantation. Thus, protecting Adivasis implies protecting the forests and through them the climate that secures the wealth of the sea. The workers he represents are directly immersed in the societal relations with nature. The fish wealth they depend on is threatened by large-scale industrialised fishing on the one hand and by environmental destruction like climate change, on the other. To develop effective strategies, they need to start from a comprehensive understanding of humans as part of nature. Pedru draws a complex picture of connections between spaces and peoples. He situates the fisherfolk within the environment together with other working people, the Adivasis. He describes an alliance between workers and the nature that sustains them and which they in turn need to sustain through the way in which they work.

The model that results from this understanding can be called: the nature – labour alliance in reference to Bloch’s concept .

How do different Perceptions of the Labour-Nature Relationship develop?

All three unionists were equally informed about climate change and environmental degradation. Yet, their perceptions of the nature-labour relationship differed decisively. My thesis is that their perceptions were not primarily informed by their theoretical knowledge but by their practices as organisers of workers in different contexts. Manoj’s perception is shaped by the experiences he has made as a trade union representative in the context of urban factory workers. In struggling to protect workers’ jobs he experiences the environmental argument as a weapon used by employers: … employers today use the environment to run down jobs, to shut plants. (…) this is not for the environment. This is to maximize profits. Nature as it presents itself to workers in a capitalist production process, belongs to the employer, it comes into the production process as raw material and transformed into tools and machines. Not only does it belong to the employer in the sense that workers have no control over the way in which it enters the production process, it can also present itself as a threat to workers’ health as dangerous substances or unsafe machines. This is exacerbated by the use of the environment as ‘job blackmail’ (Barca and Leonardi Citation2018). From the standpoint of workers, who are not directly immersed in natural processes through their work, nature is not their, but their employers’ alley. In spite of the knowledge he acquired through scientists, it is therefore difficult for Manoj to develop trade union policies that connect environmental and labour concerns. In that sense the antagonism that existed and largely continues to exist between labour and environmental groups can be seen as an embodiment of the antagonist relationship into which workers are positioned in relation to nature through the appropriation of nature by Capital. This antagonism is described in Manoj’s image of a demented population living in a beautiful environment as if, read the other way around, the destruction of that environment was a necessary condition for the flourishing of workers and their children. In reproducing that antagonism, Manoj unconsciously legitimates the appropriation of nature by Capital.

Gini’s engagement for the poor includes listening to and supporting them in their struggles for survival as workers and as citizens. When these struggles emerge from the way in which environmental destruction threatens people’s lives, Gini acts as an organic intellectual (Gramsci Citation1999), taking up their issues and investigating the chain of causes that need to be addressed to alleviate the plights of workers, women, and slum dwellers. Connecting different struggles overcomes the narrowness of a trade union focus on industrial labour, as well as the narrowness of environmental movements neglecting workers’ needs for a livelihood. Resulting from these struggles is a perception of the labour-nature relationship as instrumental. Nature becomes a necessary mediator of human life that needs to be harnessed for human needs.

In Pedru’s perception nature is also an indispensable condition for human life. However, he also recognises the ways in which humans cannot only use nature to nurture them but need to nurture nature as they themselves are part of it. This includes a vision of how work needs to be undertaken in a way that allows nature to produce and re-produce itself so that humans, as part of nature can produce and re-produce themselves as well. It is this holistic perception of what we can call the labour-nature alliance that includes for Pedru the need to work together with other people, whose way of living and working contributes to protecting the labour-nature relationship.

Pedru’s perception does not only emerge from the character of the fisherfolks’ labour, which immerses them in nature’s reproduction processes. It is also the societal character of their work from which his perceptions derive. They are small-scale fishers, working as artisans, not as employees in an industrialised fishing process. They own and control their means of production and their workplaces are simultaneously their living places. They can be seen as examples of what Ariel Salleh calls meta-industrial workers, ‘sustaining matter/energy exchanges in nature’ (Salleh Citation2009, 7).

The Role of Individual Trajectories

While I have shown that the daily practices of struggle within which our protagonists are engaged inform their perceptions of the labour-nature relationship, their individual trajectories also played a role in shaping them.

It is notable that both Gini and Pedru describe their motivation for engaging in workers’ organisations as ‘wanting to help people’. A feature that we did not find in the accounts of unionists in other countries, where most of our interviewees came from inside the trade union or had been employed by unions due to their qualifications. Gini’s and Pedru’s motivation to help the poor may have allowed them to develop a less divisive, more inclusive concept of workers. In contrast, Manoj’s motivation to recreate the left based on a specific interpretation of the urban working class as the avantgarde makes it difficult for him to see other working people as members of that class whose interests could be brought together. Along with this specific interpretation of the working-class goes a narrower interpretation of workers’ interests, which excludes nature. He follows a specific tradition within the left, which Marx challenged in his critique of the Socialist Gotha Programme: Labor is not the source of all wealth. Nature is just as much the source of use values (…) as labor, which itself is only the manifestation of a force of nature, human labor power (Marx Citation1875)

The critique that Pedru launches against the international discussions about the climate crisis could also be directed towards trade unions restricting their struggles to specific kinds of workers:

(…) the fishermen or Adivasis and other locals, the farmers, are not represented. (…) These are the first affected people. (…) But they are not represented in the climate change discussion. (…) But nobody, even NGOs, will allow them to discuss, allow them to attend these programmes.

Conclusions for Environmental Trade Union Policies

Three models of perceiving the labour-nature relationship were found which could be explained as emerging from the political practices of their protagonists and the individual trajectories which led them to become organisers of workers. The container model, nature as a mediator of survival, and the labour-nature alliance model were embedded in different environmental strategies. Manoj was locked into his task of representing urban industrial workers without perceiving that their interests included the protection of nature as the condition for their work. Consequently, he resorted to the ‘jobs vs. environment’ perception and did not create alliances between urban and rural workers, arguing that water issues of rural workers are not related to water issues of urban workers. Gini, who learned about the importance of nature as a mediator of survival through connecting the struggles of workers, slum dwellers and fisherfolks, broadened the issues of her trade union to include the protection of nature as part of workers’ lives. Pedru’s holistic perception of the labour-nature alliance led him to extend his environmental concerns beyond the immediate interests of the fisherfolks his organisations represented. His perception can be explained as deriving from the practices of fishers in control of their working conditions and directly immersed in the development of natural processes. All protagonists have made their choices regarding the struggles they engage in. However, once they have decided, the affordances of the societal structures and their practices create more or less possibilities to transform their perspectives.

Coming back to the uses of case studies as possibilities to reflect how practices might become generalisable, the question arises how unionists who are not directly engaged in broader workers’ alliances or immersed in working processes closely related to nature could develop a labour-nature perception that transcends immediate workplace experiences.

Learning by Doing

John Dewey formulated the educational principle learning by doing: ‘knowing has to do with reorganizing activity, instead of being isolated from all activity’ (2000: 216). In a different context, Salleh (Citation2009:6 f) speaks of a feminist perspective as emerging from praxis, as ‘action learning’. While our case studies show the strength of praxis as a source of ‘action learning’ in Gini’s case, they also show its limitations in Manoj’s case. Not action as such enables a more comprehensive learning process, it depends on the kind of action one is engaged in. Unions working together with other unions and workers along the supply change down to extraction processes could create learning possibilities about the labour-nature relationship but also about their unequal yet connected working conditions. In another project about workers in one transnational corporation in countries of the Global South and North we learned that knowing about each other’s lives and working conditions motivated workers of the Global North to support their colleagues in the South in their struggles for living wage. Organising forms of global collaborations among unions and with other organisations could be a way to develop a perception of the labour-nature alliance as a point of departure to overcome the ‘jobs vs. environment’ dilemma.

Acknowledgements

Mitra Payoshni, Nilajan Pande, and Piya Chakraborty conducted the interviews used in this paper and provided pen portraits of the interviewees. Nilanjan Pande wrote a paper on the history of trade unions in India, which is the basis of the respective section. After the end of the project, they moved on to other jobs and therefore could not contribute to the analyses presented here.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Nora Räthzel

Nora Räthzel is Professor em. at the University of Umeå, Sweden. Her main research areas are environmental labour studies, trade unions and the environment, working conditions in transnational corporations and gender and ethnic relations in the everyday. Latest publications include: Räthzel, N.; Uzzell, D.The future of work defines the future of humanity and all living species. International Journal of Labour Research, Geneva: International Labour Office 2019, Vol. 9, (1-2): 145-171. Transnational Corporations from the Standpoint of Workers. Palgrave 2014. With Diana Mulinari and Aina Tollefsen; Trade unions in the Green Economy. Working for the Environment. Routledge/Earthscan 2013, with David Uzzell (eds.)

Notes

1. The English translation distorts the German original, using the word ‘man’ where Marx speaks of ‘Mensch’. In German ‘Mann’ (man) and ‘Mensch’ (human being) are two different words.

2. Publications analysing other themes and countries include: (Räthzel, Cock, and Uzzell Citation2018; Räthzel et al. Citation2015; Uzzell and Räthzel Citation2019)

3. Interviews were conducted by myself with CITU, IdustriAll, Delhi, INTUC, Delhi, BMS, Delhi, AITUC, Delhi. Thanks to Rob Johnston from IndustriAll and its office in Delhi for facilitating these interviews. The Indian research team interviewed: The National Alliance for People’s movements, NTUI, AITUC, INTUC West Bengal, BMS, INTUC People’s training and Research Centre, Jyoti Karmachari Mandal, Direct Initiative for Social and Health Issues, Ramkrishna Vivekananda Charitable Trust, Kerala Independent Fish Workers Federation, Agricultural Labour Organisation, Self Employed Women Association (SEWA), Nirman Mazdoor Panchayat Sangam.

4. Jaya Prakash Narayana is a liberal politician, engaged in furthering India’s democratisation.

5. The most influential academic endeavour making theoretical sense of Indian’s diverse groups of dispossessed resisting colonial and postcolonial rule has been the Subaltern Studies, whose historians borrowed the term from Gramsci. He defined the subaltern as those excluded from societies’ institutions having no legitimate voice within them. (Guha Citation1997)

References

- Agarwala, R. 2013. Informal Labor and dignified discontent in India. Cambridge University Press.

- Barca, S., and E. Leonardi. 2018. “Working-class Ecology and Union Politics: A Conceptual Topology.” Globalizations 15 (4): 487–503. doi:10.1080/14747731.2018.1454672.

- Bloch, E. 1973. Das Prinzip Hoffnung 3. Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp.

- Chattopadhyay, M. 1996. The Trailblazing Women Trade Unioninsts of India. New Dehli: AITUC Publications.

- Castree, N., and B. Braun. 2001. Social Nature: Theory: Practice and Politics. Wiley-Blackwell: London.

- Dange, S. 1973. Origins of Trade Union Movement in India. New Delhi: AITUC Publications.

- Dutt, R. 1949. India Today. Bombay: People’s Publishing House.

- Fairbrother, P., and C. A. B. Yates, Eds. 2003. Trade Unions in Renewal: A Comparative Study, Employment and Work Relations in Context Series. London; New York: Continuum.

- Farnhill, T. 2016. “The Characteristics of UK Unions’ Environmental Activism and the Agenda’s Utility as a Vehicle for Union Renewal.” Global Labour Journal 7 7 (3). doi:10.15173/glj.v7i3.2536.

- Felli, R. 2014. “An Alternative Socio-ecological Strategy? International Trade Unions’ Engagement with Climate Change.” null 21: 372–398. doi:10.1080/09692290.2012.761642.

- Flyvbjerg, B. 2006. “Five Misunderstandings About Case-Study Research.” Qualitative Inquiry 12 (2): 219–245. doi:10.1177/1077800405284363.

- Gindin, S. 2015. “Bringing Class Back In.” Global Labour Journal 6(1).

- Gramsci, A. 1999. Selections from the Prison Notebooks, Essential Classics in Politics: Antonio Gramsci. London: Electric Company.

- Guha, R., Ed. 1997. A Subaltern Studies Reader, 1986-1995. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Haraway, D. J. 2008. When Species Meet, Posthumanities. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Holstein, J. A., and J. F. Gubrium, Eds. 2003. Inside Interviewing: New Lenses, New Concerns. Sage Publications, Thousand Oaks [Calif.].

- International Labour Office, 2018. Women and Men in the Informal Economy: A Statistical Picture.

- Marx, K., 1875. Critique of the Gotha Programme. http://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1875/gotha/ch01.htm, ( accessed 20 March 2012).

- Marx, K. 1998. Capital. A Critique of Political Economy. 1887th ed. ElecBook: London.

- Moody, K. 1997. Workers in a Lean World: Unions in the International Economy, the Haymarket Series. London; New York: Verso.

- Moore, J. W. 2015. Capitalism in the Web of Life: Ecology and the Accumulation of Capital. 1st ed. New York: Verso.

- Morena, E., D. Krause, and D. Stevis. 2020. Just Transitions: Social Justice in the Shift towards a Low-carbon World.

- Nanda, B. R. 2004. “In Search of Gandhi: Essays and Reflections.” Oxford University Press doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195672039.001.0001.

- Pellow, D. N. 2007. Resisting Global Toxics: Transnational Movements for Environmental Justice. In Series: Urban and Industrial Environments. MIT Press. Mass: Cambridge.

- Portelli, A. 1997. The Battle of Valle Giulia: Oral History and the Art of Dialogue. Madison, Wis: University of Wisconsin Press.

- Rao, B. S. 1939. Industrial Worker in India. George Allen & Unwin: London.

- Raveendran, N. 1992. Trade Union Movement: A Social History. Trivandrum, Kerala, India: CBH Publications.

- Räthzel, N., and D. Uzzell. 2011. “Trade Unions and Climate Change: The Jobs versus Environment Dilemma.” Global Environmental Change 21 (4): 1215–1223. doi:10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2011.07.010.

- Räthzel, N., D. Uzzell, R. Lundström, and B. Leandro. 2015. “The Space of Civil Society and the Practices of Resistance and Subordination.” Journal of Civil Society 11 (2): 154–169. doi:10.1080/17448689.2015.1045699.

- Räthzel, N., and D. L. Uzzell. 2013. Trade Unions in the Green Economy: Working for the Environment. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Räthzel, N., J. Cock, and D. Uzzell. 2018. “Beyond the Nature–labour Divide: Trade Union Responses to Climate Change in South Africa.” Globalizations 15 (4): 504–519. doi:10.1080/14747731.2018.1454678.

- Rector, J. 2014. “Environmental Justice at Work: The UAW, the War on Cancer, and the Right to Equal Protection from Toxic Hazards in Postwar America.” Journal of American History 101 (2): 480–502. doi:10.1093/jahist/jau380.

- Salleh, A., edited by. 2009. Eco-sufficiency & Global Justice: Women Write Political Ecology. Pluto Press, London.

- Snell, D., and P. Fairbrother. 2010. “Toward a Theory of Union Environmental Politics: Unions and Climate Action in Australia.” Labor Studies Journal 36 (1): 83–103. doi:10.1177/0160449X10392526.

- Stevis, D., D. Uzzell, and N. Räthzel. 2018. “The Labour–nature Relationship: Varieties of Labour Environmentalism.” Globalizations 15 (4): 439–453. doi:10.1080/14747731.2018.1454675.

- Stevis, D., and R. Felli. 2015. “Global Labour Unions and Just Transition to a Green Economy.” International Environmental Agreements: Politics, Law and Economics 15 (1): 29–43. doi:10.1007/s10784-014-9266-1.

- Sweeney, S., and J. Treat. 2018. “Trade Unions and Just Transition.” The Search for a Transformative Politics. TUED Working Paper 11, New York

- Tait, V., C. Tzintzun, and I. Recorded Books. 2016. Poor Worker’s Unions: Rebuilding Labor From Below (Completely Revised and Updated Edition {Rpara}. Chicago: Haymarket Books.

- Trivedi, L. N. 2003. “Visually Mapping the “Nation”: Swadeshi Politics in Nationalist India, 1920–1930.” The Journal of Asian Studies 62 (1): 11–41. doi:10.2307/3096134.

- Uzzell, D., and N. Räthzel. 2019. “Labour’s Hidden Soul: Religion at the Intersection of Labour and the Environment.” Environmental Values 28 (6): 693–713. doi:10.3197/096327119X15579936382473.

- Vachon, T. E., and J. Brecher. 2016. “Are Union Members More or Less Likely to Be Environmentalists? Some Evidence from Two National Surveys.” Labor Studies Journal 41 (2): 185–203. doi:10.1177/0160449X16643323.