?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

Brazil plays a central role in Western depictions of and narratives on tropical deforestation. In this contribution, we gather a large text corpus from Western media outlets with articles on deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon and Cerrado biomes. The sources include outlets from Europe, the US, Canada and Australia and span a time period from the late 1980s to 2020. Leveraging several text-mining approaches, such as topic modeling and automated narrative network analysis, we disentangle the way that Western media have tried to make sense of deforestation in the Amazon and the Cerrado biomes. We show that the former has received disproportionately more news coverage, specifically in times of international concern over the Brazilian government’s commitment to tackle deforestation. Further, Western media frequently report on the struggles of indigenous populations in the Amazon, often following an essentialist depiction of these communities, while in the case of the Cerrado, traditional populations are hardly mentioned at all. Our findings provide a methodologically innovative and empirically grounded case for the often raised concern over a relative invisibility of the Cerrado biome and its traditional populations, which may help explain observed disparities in governance interventions.

1. Introduction

Brazil plays a central role in Western depictions of and narratives on tropical deforestation. It is among the countries with the largest share of remaining native vegetation, but simultaneously has emerged as one of the planet’s leading deforesters. Since the 1970s, the country turned from a net food importer to a modern agricultural powerhouse and a leading exporter of products such as soybeans, beef and coffee (Stabile et al. Citation2020).

This has been enabled by policies of targeted settlement in frontier regions, readily available rural credit, large infrastructural projects, dedicated agricultural research and successive commodity booms, most recently triggered by strong demand from East Asia (Oliveira and Schneider Citation2016). Agricultural expansion has encroached into various biomes, such as the Amazon rainforest and the Cerrado, a tropical Savannah biome with exceptionally high endemic biodiversity, which has already lost more than 50% of its native vegetation (Lahsen, Mercedes M.C., and Dalla-Nora Citation2016).

While different commodity booms in the Amazon go back at least to the first rubber boom in the late 19th century and regional economic development has been pushed for by the Brazilian military since the 1930s (Hecht and Cockburn Citation2011), in the Cerrado this process started later, when targeted government programs inserted the region into the realm of capitalist production in the 1970s. This transformed the image of the Cerrado, which had previously been rendered invisible due to its reputation as barren land without economic value (da Silva and Chaveiro Citation2010). What appears to remain invisible though, is the cultural and socio-environmental diversity of traditional populations occupying the Cerrado, who have often found themselves in conflict with large development projects and agribusiness (Russo Lopes, Bastos Lima, and dos Reis Citation2021; Gualdani and Fernando Luiz Citation2018; Silva and Eduardo Citation2009).

Federal legal protection, international agreements and corporate commitments have sought to address environmental impacts associated with the recent commodity booms. This resulted in a significant decline of deforestation rates in the Amazon biome after 2004 (Heilmayr et al. Citation2020). However, the strong political advocacy of large landowners, corporate agribusiness and the changes of political leadership following the ouster of former president Dilma Rousseff challenge this development. Further, the Cerrado biome has not received the same legal protection, and is not covered by most zero-deforestation commitments, leading to rapid landuse change and conversion of native vegetation (Lahsen, Mercedes M.C., and Dalla-Nora Citation2016; Rausch et al. Citation2019; Green et al. Citation2019). Between 2002 and 2011, deforestation rates in the Cerrado were more than twice as high than in the Amazon, putting pressure on an ecosystem, which is vital for the regional hydrological cycle, a biodiversity hotspot, a source of livelihood for local populations and leading to the decimation of large carbon stocks (Strassburg et al. Citation2017).

The perceived asymmetry in attention towards different biomes is not limited to the Amazon and Cerrado. Recently, scholars introduced the concept of Biome Awareness Disparity (BAD), to describe a general failure to appreciate the significance of diverse biomes in terms of conservation (Silveira et al. Citation2021). BAD generally appears to favor tropical forests over open biomes, such as grasslands, savannas, and shrublands, which have been shown to receive significantly less attention compared to the area they occupy (Silveira et al. Citation2021) and are less often the focus of conservation and restoration practice (Temperton et al. Citation2019; Qin et al. Citation2022). Further, even as the expansion of soybean monocultures is associated with larger deforestation risks in the Cerrado, discourse in Western media and political institutions appears to have focused on the Amazon (Mempel and Corbera Citation2021).

This contribution analyses the asymmetry in attention between these biomes and the construction and framing of the problem of deforestation in Western media outlets. Starting from the assumption that social problems do not manifest themselves directly, but through processes of claims-making between different actors and mediated though different channels (Hannigan Citation2006; Hansen Citation2015), in this contribution we ask:

(1) How much coverage has deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon and Cerrado biomes received in Western media outlets at different time periods in the past decades?

(2) What drivers, impacts and responses are dominating media narratives on deforestation in these biomes at different time periods?

(3) What actors receive most attention and what actions are these commonly associated with in narratives on deforestation in the different biomes?

(4) In how far does the amount of coverage and the framing of deforestation in the two biomes correspond to asymmetries in governance initiatives to halt forest loss?

To address these questions, we gathered a text corpus consisting of 9,113 news articles from Western news outlets as well as global news agencies and used a text mining approach to select relevant articles, classify topics, extract named entities and identify relevant actors and the associated actions they are portrayed to perform. The following section locates our research in ongoing debates on global environmental governance and the role of Western media therein. Section 3 details the methods used in our analysis, section 4 presents the findings, section 5 discusses the results and section 6 ends with our conclusions.

2. Linking Western media to environmental governance of tropical deforestation

The role of communication and discourse in the realm of environmental issues has interested scholars since the 1970s, not least due to the rapid rise of attention toward a domain, which only began to be fitted with its own vocabulary and themes in the postwar era and emerged as a ground of political contestation with dedicated social movements and advocacy groups (Downs Citation1972; Hansen Citation2015). Here, we are interested in the role of Western media in the ‘politics of signification’ (Hall Citation1982) in the context of global environmental governance of tropical deforestation. In other words, we start from the assumption that mass media play a role in defining and giving meaning to issues of deforestation both for stakeholders and the wider public and thereby influence the formulation and legitimization of governance interventions.

While the term ‘global environmental governance’ has different connotations and uses (Biermann and Pattberg Citation2008), these still share a set of defining characteristics, all of which can be observed in the context of commodity-driven tropical deforestation. Like other environmental arenas, over the past decades forest politics has seen experiments with novel forms of interventions characterized by new configurations of actors, including nation states, subnational governments, intergovernmental organizations, international courts, private actors and civil society. Among these interventions are market-based certification programs, such as the Forest Stewardship Council (FSC), commodity-specific multi-stakeholder roundtables (e.g., Round Table on Responsible Soy), corporate zero-deforestation commitments and public-private voluntary declarations (e.g., New York Declaration on Forests). Further, international funding has become increasingly important for conservation efforts, particularly for projects in the Global South (Waldron et al. Citation2013; Qin et al. Citation2022). In Brazil, this new forest politics can be traced back to the Pilot Program for the Protection of Tropical Forests (PPG7), which was launched during the UN’s Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro, following international pressure in the aftermath of the assassination of Chico Mendez and public growing concern over deforestation in the Amazon (Bidone and Kovacic Citation2018). The program was largely funded by European countries, resources administered by the World Bank and the projects included efforts from the Brazlian government, as well as NGOs, the United Nations Development Program (UNDP) and donor agencies.

These ‘post-sovereign’ (Pattberg Citation2007) approaches to forest politics are also envisioned as solutions to increasingly distant and globally entangled drivers of forest loss, strongly influenced by international demand for commodities sourced from deforestation frontiers. However, questions remain concerning the effectiveness and legitimacy of these interventions. For example, even though the relevance of individual corporate actors, who have consolidated significant shares of forest risk commodities in their supply chains, is clear (Folke et al. Citation2019), it remains disputed what part they can and should play in resolving environmental problems (Dauvergne and Lister Citation2012; Zu Ermgassen et al. Citation2022). For our purposes, the important observation is that these new forms of forest politics involve processes of signification, deliberation and legitimization in public spheres distant from the deforestation frontiers themselves. Given the importance of Western actors in corporate control over forest risk commodity value chains, conservation funding and international environmental advocacy, we will focus on Western media discourse.

In this context, we are interested in when (Mangani Citation2021) and where (Silveira et al. Citation2021) deforestation becomes a matter of concern and how it is framed (Ladle et al. Citation2010; Park and Kleinschmit Citation2016). By frame, we mean a ‘schema of interpretation’ (Goffman Citation1974) or ‘central organizing idea or story line that provides meaning’ (Gamson and Modigliani Citation1987) and communicates ‘why an issue or decision matters, who or what might be responsible, and which political options or actions should be considered over others’ (Nisbet and Newman Citation2015). Problem framing is value-laden, carries presuppositions or assumptions from particular contexts and can remain silent on some aspects while emphasizing others (Bacchi Citation2009). Following Snow and Benford (Citation1988) we broadly distinguish three types of frames: diagnostic frames, which identify problems and attribute responsibility; prognostic frames, which suggest solutions and strategies; and motivational frames, which provide the rationale for action by stressing moral considerations or urgency of impacts.

When, where and how deforestation receives media coverage matters rather independent on the specific conceptualization of mass media and their role in the broader socio-political context. Mass media have been characterized as an important arena for rational debate in a form of deliberative democracy (Habermas Citation1996) or rather as a political actor largely reflecting elite views in a ‘capitalist information production’ (Mosco and Herman Citation1981). We agree with Kleinschmit (Citation2012) that while it appears that mass media do not fully comply with the functions of democratic deliberation due to inherent constraints, these functions still provide useful normative expectations to evaluate empirical findings against. This is true particularly in the age of post-sovereign politics, where the public arena plays a role in the regulation of transnational corporations (TNCs) and other private actors with large leverage in environmental affairs (Newell Citation2001).

Finally, news media framing on tropical deforestation does not occur in a historical void. These frames engage with broader evolving discourses on environmental affairs (Herndl and Brown Citation1996; Dryzek Citation2013). Further, they are fed by socially accepted narratives and imagery on particular places, for example through the proliferation of travel narratives and fictional literature about the Amazon, which has been linked to its fetishizing as a symbol of wild nature (Vieira Citation2016).

3. Methods

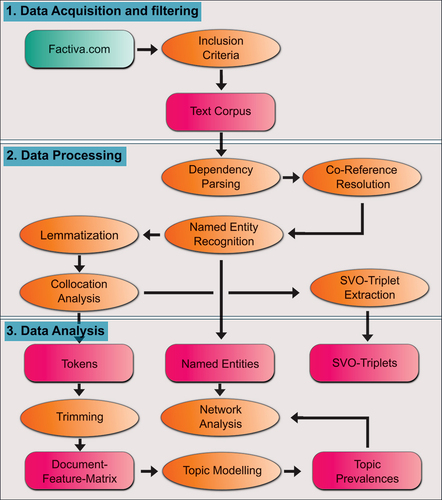

We use a text mining approach to analyze the occurrence and nature of Western media coverage on deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon and Cerrado biomes. The process of data acquisition, data processing and data analysis is illustrated in .

We sourced news articles from factiva.com (Dow Jones & Company Citation2020). Two separate searches were performed for the Amazon and Cerrado biomes to gather articles dealing with deforestation in each (see search strings in supplementary material). We included all available news outlets from Europe, the United States, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand, as well as news wires from all available international news agencies. The study period was defined from 1980 to 2020. Only articles in English language were selected. The process of data collection ensured a relatively large number of relevant news articles through the study period and further a broad spectrum of different publication types. However, it also means that the composition of news outlets changes over the time period, as not all news sources are available for the entire study period, giving a much more sparse selection especially for the 1980s. To correct for this, when calculating corpus statistics, we calculate prevalence as the number of articles in a given year divided by all articles that are available for all included news outlets on factiva.com for the same year. In total, 485 different news outlets are included in the sample.

To ensure that the selected articles in fact focus on deforestation in the respective biomes, we further defined a set of inclusion criteria. Full documents were only included if the respective biome was mentioned in the headline, the lead paragraph or if the following condition is satisfied:

where N denotes the number of mentions and n the total number of paragraphs in the document. For all other documents, only those paragraphs mentioning the respective biome were included.

Included documents were pre-processed with the natural language processing library SpaCy (Honnibal and Johnson Citation2015) for the Python programming language (Guido and Drake Citation2009). Texts were parsed to identify grammatical dependency structures and resolved for co-references. Named entities were identified and collected separately. Compound words were detected using collocation analysis. Tokens (words and compound words) for the topic model were trimmed to include only nouns, verbs, adjectives, and adverbs and to exclude named entities, which were collected separately. We extracted Subject-Verb-Object (SVO) triplets from all documents, loosely following the approach outlined by Sudhahar et al. (Citation2015) and Sudhahar, Veltri, and Cristianini (Citation2015). This allows to identify key actors and objects as well as their mutual relations (through actions), in order to approach an automated analysis of narrative content (Sudhahar et al. Citation2015), thereby going beyond merely identifying topics and themes.

The tokens were converted to a document feature matrix (DFM) using the quanteda text mining library (Benoit et al. Citation2018) in the statistical programming environment R (R Core Team Citation2020). A DFM is a statistical representation of a text corpus, indicating the frequency of all occurring terms for each document. Word order is not relevant in this representation. The DFM was supplied to the STM package (Roberts, Stewart, and Tingley Citation2019) to compute a structural topic model (STM) (Roberts et al. Citation2014). Topic models are a statistical framework used to identify topics in a text corpus (Wesslen Citation2018). They belong to the group of unsupervised machine learning algorithms and do not depend on training datasets, but provide classifications based on patterns identified within the data itself (Grimmer and Stewart Citation2013). Compared to other topic modeling algorithms, the STM allows for the inclusion of document metadata as covariates. Here, we included publication year and the biome (Amazonia or Cerrado) as covariates. After evaluating several tests statistics, we decided on using a model with 40 topics (the model parameter K).

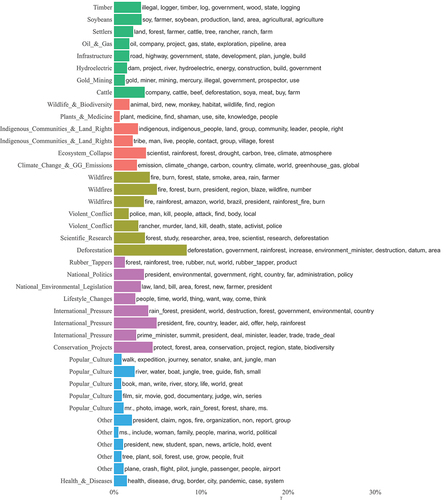

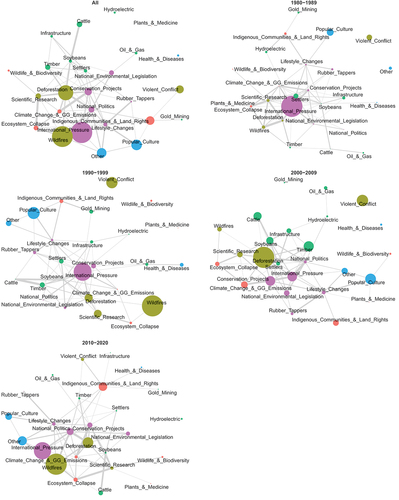

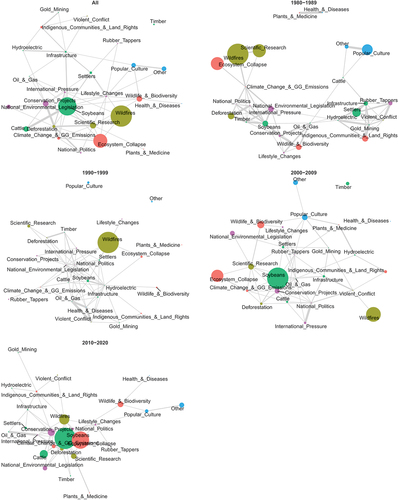

We labeled and aggregated the resulting topics and grouped them into the following categories: Drivers, for those related to processes that drive deforestation in the respective biomes, Processes, for topics related to other processes accompanying deforestation or otherwise linked to it, Impacts, for those related to impacts resulting from deforestation, Responses, for those referring to measures or reactions responding to deforestation, and Other, for topics not associated with any of these categories. We then compared the topics’ prevalence for different time periods and calculated cosine similarities between the vectors indicating the prevalence of each topic within each document. The similarity matrix was then converted into a network representation with node size illustrating topic prevalence and edge width indicating the degree of co-occurrence between topics. The same was done with topics and extracted named entities referring to organizations and institutions.

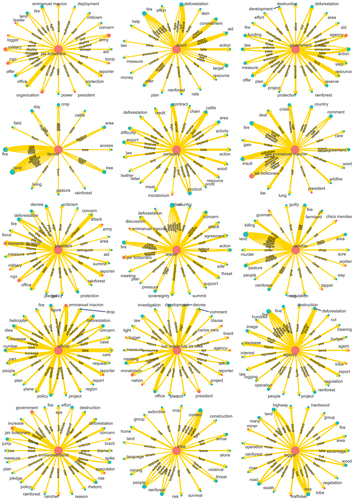

SVO triplets were filtered to include only those, in which the subject can be identified as a relevant actor (a subject, which is sufficiently defined to represent a social group, profession, economic sector, institution, etc.). We selected the 25 most frequently occurring subjects for each biome and study period and plotted each of these subjects with its respective 25 most common SVO structures as network diagrams, in which nodes represent subjects and objects and edges represent verbs. These semantic graphs illustrate the main actors, objects and actions that constitute the narration contained in the news articles on deforestation in the respective biomes (Sudhahar et al. Citation2015).

Finally, a sample for manual coding was selected from the text corpus in order to enhance and validate the automated text analysis with human coding. The sample consists of 222 texts, which were selected to represent the distribution of topics found by the topic model for each time period. We randomly selected 30 articles for each time period and biome in 10,000 iterations. For each time period and biome the iteration which most closely resembled the topic prevalence distribution found by the topic model (cosine similarity) was selected. Due to lack of articles for the Cerrado biome in the earliest time period, the selection falls short of the expected number of articles (240).

The selected articles were manually coded according to three questions, loosely based on the identification of diagnostic, prognostic and motivational frames:

(1) What actors are portrayed as being responsible for deforestation or for enabling it (diagnostic frames)?

(2) What responses and solutions are identified, which are being implemented or should be implemented to address the problems (prognostic frames)?

(3) What urgent consequences and problems associated with deforestation are identified (motivational frames)?

Coding was performed in the free application QCAMap (Mayring Citation2014; Fenzl and Mayring Citation2017), consecutively exporting all results into the R programming environment for analysis.

4. Results

4.1. Uneven and fluctuating attention to deforestation

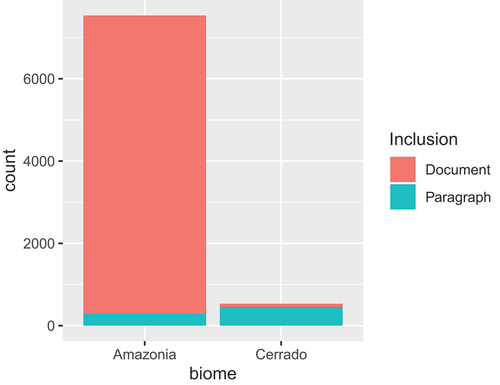

After applying all selection criteria and removing duplicates, the text corpus consists of a total of 8,072 documents of which 7,330 are full news articles and 742 are selected paragraphs. The total number of documents dealing with deforestation in the Amazon biome (7,538 documents) is more than 14 times greater than the number of documents found for the Cerrado biome (534 documents). Further, most texts on the Amazon are full news articles, while most texts on the Cerrado are paragraphs extracted from texts, which may have differing main topics (see ).

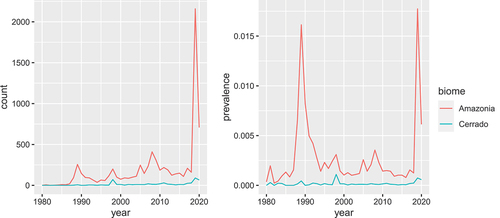

When examining the distribution of sourced texts over time (see ) we see several distinct peaks in years, in which deforestation in the selected biomes appears to have attracted more attention, most notably for 2019 in the case of the Amazon biome. Since the availability of the selected outlets in factiva.com changes over time and is generally much lower for years before 2000, we calculated the prevalence of texts dealing with deforestation in the two biomes, by dividing the number of sourced texts by all articles available from all selected outlets in the same year. Another distinct peak of attention towards deforestation in the Amazon becomes visible for the year 1989.

Further, of the 485 different news outlets included, only 46 (9.5%) featured at least one full length article on deforestation in the Cerrado biome in the entire study period, compared to 470 (96.9%) for the Amazon biome. When including individual paragraphs, 139 news sources (28.7%) mentioned deforestation in the Cerrado, compared to 474 for the Amazon (97.7%).

4.2. Framing deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon and Cerrado

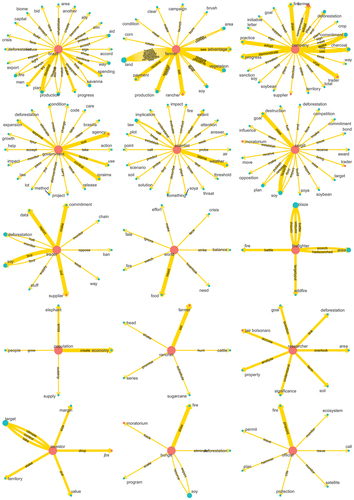

In the following sections, we present our results from the topic model, extracted named entities, SVO-triplets and manual coding to analyze how Western media have framed deforestation for the Amazon and Cerrado biomes. illustrates the eight top terms associated with each of the 40 resulting topics, their assigned labels as well as the topics’ total prevalence within the entire text corpus. As illustrated, we aggregated topics into 27 distinct themes in our analysis, each either a unique topic from the model or a combination of several topics. Prevalence values for composite topics are sums. These themes are further classified into the categories Drivers, Processes, Impacts, Responses and Other.

Figure 4. Topics with absolute prevalence and top 8 contributing terms. categorized as drivers (green), impacts (red), processes (olive), responses (purple), other (blue).

are network representations of the results from the topic model for the two biomes and all time periods. A given topic’s prevalence is indicated by node size. Co-occurrence of two given topics (cosine similarity) is illustrated by edge thickness with only the upper 25 percentile of edges being plotted to enhance readability. are the semantic graphs from the extracted SVO-triplets for the two biomes. Each network indicates the 20 actions and objects a given subject is most associated with in the text corpus and the order of subjects reflects their frequency of occurrence. Here, we plotted the 15 most frequently occurring subjects for each biome. More detailed semantic graphs for each time period, the network graphs from extracted names entities and the results from our manual coding are found in the supplementary materials.

Figure 5. Topic co-occurrence networks for articles on the amazon biome. Nodes are colored according to topic category. Only the upper 25 percentile of edges is plotted.

Figure 6. Topic co-occurrence networks for articles on the cerrado biome. Nodes are colored according to topic category. Only the upper 25 percentile of edges is plotted.

Local conflicts and international pressure: Western media and deforestation in the Amazon

Corresponding to the larger abundance of articles on deforestation in the Amazon biome, we also find more variety and dynamics in occurring themes. As revealed in the topic networks and confirmed through our manual coding, articles tend to explicitly reference various drivers throughout the study period. These diagnostic frames attribute responsibility to both, national actors, such as the national government, gold miners, cattle ranger or farmers, and to transnational corporations or international demand. The periods with highest media attention (1980s and 2010s) tend to emphasize Brazilian politics and the responsibility of the national government, while the expansion of various commodities (e.g. timber, cattle, soybeans) dominates in the 2000s. Next to wildfires, violent conflicts are mentioned as processes accompanying deforestation. This is confirmed in the semantic networks, which reveal narratives of conflict in which local stakeholders are portrayed in a very contrasting manner. Farmers, ranchers and loggers are often framed as responsible for deforestation and for violent threats towards indigenous communities (e.g., ‘farmer – cut – tree’, ‘logger – threaten – tribe’). In stark contrast to that, indigenous communities are portrayed as environmental defenders (e.g., ‘tribe – save – rainforest’, ‘tribe – oppose – mining’), armed with primitive weapons (e.g., ‘tribe – fire/aim – arrow’) and receiving support from international environmentalists. Companies appear as subjects of phrases that either characterize them as drivers of deforestation (e.g., ‘company – continue – deforestation’), or as signatories of important agreements and good-will actors (e.g., ‘company – accept – moratorium’, ‘company – take – action’).

We also observe a high prevalence of topics related to various responses, particularly international pressure and conservation projects. This is confirmed by our manual coding, which identified prognostic frames related to international pressure, international funding and even calls for an internationalization of the Amazon region (in the form of a United Nations controlled global patrimony) occurring in the time periods with highest media attention. The importance given to international pressure is confirmed by the semantic networks. These are dominated by phrases of international political figures (e.g., Emmanuel Macron) in rhetorical exchanges with Brazilian politicians (e.g., Jair Bolsonaro). National legislation as well as monitoring and enforcement are more dominant in the 2000s. The semantic networks for this period are also clearly dominated by Brazilian state actors (e.g., government, police, official, state; see supplementary material). Responses through supply chain management or corporate governance appear more frequently over the past decades. While the semantic networks reveal companies as being portrayed in tension between local development (e.g., ‘company – create – job’) and environmental destruction (e.g., ‘company – wreak – havoc’) in the 1980s and 1990s, since the 2000s they also appear as part of the solution (e.g., ‘company – adopt – commitment’; see supplementary material).

The selected news articles stress the importance and urgency of several problems associated with deforestation in the Amazon. These motivational frames include references to climate change, biodiversity loss, the collapse of ecosystems and related services, public health issues and the incursion on indigenous lands. All of these appear since the early 1980s, while a number of recent news articles also mention the loss of endemic species and associated consequences for developing new pharmaceuticals. The importance of indigenous communities and human rights is further highlighted by the fact that several named entities relating to organizations in the realm of human rights and indigenous affairs occur frequently and are strongly associated with topics on indigenous groups and land rights. These include FUNAI, a Brazilian governmental agency for indigenous rights and Survival International, a human rights charity organization. The entanglement of deforestation and human rights is also clearly discernible in the semantic graphs, in which indigenous communities are linked to threats such as ‘extinction’ and ‘violence’.

The articles also include significant references to topics around popular culture. These news stories tend to cite travel accounts, documentaries or fictional writing, which combine appreciation of the biome’s biodiversity and culture with depictions of processes and impacts of deforestation, particularly wildfires, biodiversity loss and incursions on indigenous lands.

Wildfires and biodiversity: framing forest loss in the Cerrado

In general, articles on the Cerrado biome are less diverse in terms of prevailing topics. Regarding diagnostic frames, wildfires and soybean expansion are dominant across all time periods. This is confirmed by the results from our manual coding, which indicate that farmers and agribusiness are most often attributed responsibility for deforestation where explicitly identified. The dominance of agricultural expansion and wildfires in framing the processes behind deforestation in the Cerrado is further highlighted by the semantic networks. These indicate frequent mentions of large grain traders (e.g., ‘cargill – fuel – destruction’) and farmers (‘farmer – burn – brush’) driving conversion of native vegetation, as well as different actors engaging in monitoring and fire suppression (e.g., ‘firefighter – battle – fire’). However, as for the other categories, articles on the Cerrado, which are often single paragraphs, do not engage as often with question around drivers or responsibility when compared to the Amazon biome. In fact, these paragraphs are often mere footnotes to the entire news article, which often share the same main topic: deforestation in the adjacent tropical forest.

References to responses or solutions are even less prevalent than drivers. National legislation, monitoring (e.g., real-time satellite imagery for fires) and enforcement as well as conservation projects dominate. For the 2010s, supply chain management becomes the most important response referenced. The importance of corporate actors in these prognostic frames is highlighted further by the extracted named entities. Most of these correspond to corporate actors, including retailers (e.g., Tesco, Walmart), foodchains (e.g., McDonald’s), food processing companies (e.g., Unilever) and investors (e.g., Norges Bank, which manages the Norwegian Government Pension Fund Global). The semantic networks also reveal a focus on monitoring and enforcement on the one hand (e.g., ‘scientist – evaluate – impact’, ‘government – monitor – impact’) and corporate actors engaging in supply chain solutions on the other (e.g., ‘cargill – end – deforestation’, ‘bunge – back – moratorium’).

Mentions of impacts and consequences are mainly restricted to biodiversity loss and ecosystem collapse for most time periods. In the past decade, climate change appears as the most significant concern. Indigenous or traditional populations are hardly referenced at all in the selected articles. Accordingly, the semantic networks do not reveal the same framing of deforestation as social conflict. The dominant subjects are mostly stakeholders in commodity chains (e.g. ‘company’, ‘cargill’, ‘bunge’), researchers, and government institutions. Deforestation appears to be portrayed as a problem objectively raised by researchers, monitored by officials, and addressed to varying levels of success through commitments by private stakeholders.

5. Discussion

Western mass media play a role in the networked setting of post-sovereign forest politics. Whether conceptualized as an important forum for deliberation or as political actors performing selective gatekeeping, their reporting reflects, interacts with and has a legitimizing function in the processes of global environmental governance. In the context of commodity-driven tropical deforestation in Brazil, researchers have pointed to an asymmetry in the efforts to halt the loss of native vegetation in the Cerrado biome when compared to the Amazonian rainforest. These accounts characterize the Cerrado and its traditional populations as a blindspot in conservation funding, corporate commitments or protected areas. Our findings provide empirical evidence that indeed there is a strong difference between the two biomes in terms of how much attention they receive and how deforestation is framed in Western mass media.

Our results indicate that the Amazon biome not only receives significantly more attention but also that concerns for human rights, particularly linked to indigenous people, are much more dominant, while in the case of the Cerrado references to local populations are sparse. This confirms accounts of the Cerrado being portrayed as empty space (Sauer and Oliveira Citation2021; da Silva and Chaveiro Citation2010), a narrative which has also been key in different Brazilian administrations’ efforts to turn the region into an agribusiness hotspot since the mid-20th century. The increasing appearance in full-length articles on deforestation in the Cerrado in the past decade, with more direct references to drivers and responses, appears to be due to the recent recognition of the biome’s relevance in the context of global climate change and biodiversity loss.

It would be pointless to argue that media should essentially cover deforestation in the two biomes identically. After all, they do represent separate entities, bio-physically and socioeconomically. However, our findings corroborate and, to certain extent, help to explain that the Cerrado, as other open biomes, receives less attention in conservation efforts than tropical forests, as suggested by Silveira et al. (Citation2021). Asymmetries in media attention and framing may also be linked to what Qin et al. (Citation2022) find to be a ‘major bias towards rainforests’ in funding from international donors for conservation-related projects in South America. The authors also find that the expressed objectives of this funding towards the Amazon biome are more often related to development and human rights, while those for the Cerrado mostly center around conservation and ecosystem services. Further, in the Cerrado protected areas cover significantly less surface area, obligations under the Brazilian Forest Code are weaker and major corporate commitments, such as the Soy Moratorium do not apply (Strassburg et al. Citation2017).

As previously argued, media discourse does not emerge from a historical void. Rather, Western media’s representations and discourses are built upon constructs of reality drawn from historical processes (Dryzek Citation2013). This includes the particular place the Amazon basin holds in Western imaginaries, or, in the words of Susanna Hecht and Alexander Cockburn: ‘What imbues the case of the Amazon with such passion is the symbolic content of the dreams it ignites’ (Hecht and Cockburn Citation2011, p.1). Particularly since the 1980s (the beginning of our study period), following the release of imagery from Space Shuttle Colombia, which revealed clearly visible patterns of deforestation in the Amazon basin, the fate of Amazonia, which had thus far been seen as a remote, pristine wilderness, started to raise widespread concern and anxiety among Western publics (Miller Citation2007).

This global concern with deforestation in Amazonia has gone hand in hand with rather binary and essentialist characterizations of different actors. Indeed, current framings on the Amazon region hold historical roots to seminal, colonial Eurocentric imagery, which began influencing the modern perception about the region. Such fables were readily adopted by Western colonizers, intellectuals, and later politicians of Amazonian nations, as a response to their ‘inability or even lack of interest to come to terms with the complexity of Amazonian life’ (Vieira Citation2016, 123). Our findings show that media coverage on deforestation in the Amazon biome often references travel accounts, documentaries and literature. This highlights the importance of what Herndl and Brown (Citation1996) refer to as ‘poetic discourse’, narratives that assign an intrinsic emotional or spiritual value to nature and which can be tapped into by media frames, perhaps making these stories more attractive and newsworthy for media organizations.

A typical frame in this context is that of the ecological noble savage, depicting indigenous communities as primitive forest dwellers, armed with bows and arrows and mainly concerned with protecting pristine nature from economic development and occupation by cattle ranchers, gold miners or farmers (Murphy Citation2017). This has made these communities natural allies for Western environmental NGOs and celebrity advocates, who have championed a myth of indigenous people as authentic, natural conservationist within a discourse characterized by a strong dichotomy between economic development and nature conservation, often referred to as Green Radicalism (Dryzek Citation2013; Murphy Citation2017). Media accounts tap into these depictions to construct relatively simplistic ‘injustice frames’ (Gamson, Fireman, and Rytina Citation1982), which amplify the victimization of indigenous groups. These frames have allowed indigenous communities to strategically insert their own concerns into wider public discourse and gain visibility on the global political stage. However, this narrow framing has also at times restricted their messages to those parts in line with the agenda of international environmentalists and its implicit image of indigenous populations (Murphy Citation2017).

Despite widespread global attention to deforestation in the Amazon biome, distinct peaks in coverage are visible, indicating rather event-focused coverage. These occur particularly at times, when the Brazilian national government is attributed with responsibility for deforestation, as during the administrations of José Sarney (1985–1990) and Jair Bolsonaro (2018 – present). In these periods international pressure, foreign financial aid and at times even calls for an internationalization of the region feature prominent among the responses mentioned. Disputes between international political figures are also referred to commonly. Less coverage is attracted by periods of relative progress in legislative measures to tackle deforestation (e.g., during the Lula administration, particularly with Marina Silva as Minister of the Environment).

Such pressure has proved at times to be effective and shown to drive Brazilian environmental governance steps further towards an agenda of sustainable development (Bidone and Kovacic Citation2018), as through the Pilot Program for the Protection of Tropical Forests (PPG7) in the 1990s. It aimed at protection and sustainable use of the Amazon Forest and the Mata Atlântica, with improvements in the quality of life of local populations and was established after a certain international clamor from developed nations to assist in Brazil’s troubles in dealing with Amazonian deforestation. This indicates that attention towards and framing of deforestation in Brazil across western media influences or at least reflects new approaches to governance interventions.

With increasing attention towards commodity expansion as a driver for deforestation, topics around consumer responsibility and corporate supply chain management become more dominant. This trend is in line with a turn towards a more pragmatic approach towards sustainability in environmental discourses or what Dryzek (Citation2013) refers to as the ‘Ecological Modernization’ discourse. Particularly, news articles on deforestation in the Cerrado seem to be dominated by this framing, which highlights the tackling of problems by involving corporate stakeholders, intensifying land-use to release pressure on forest and by increasing monitoring efforts for wildfires. Local communities and their struggles are hardly referred to at all in articles on deforestation in the Cerrado biome.

The inherent technocratic character of ecological modernism perhaps influences this lack of mention towards specific groups of stakeholders, which are marginalized subjects from the process of capitalist expansion in Latin American commodity frontiers. The focus on wildfires and associated monitoring and enforcement measures in the Cerrado may in some cases even frame traditional smallholders, who rely on fires for soil management, rather as part of the problem than as victims of expulsion and marginalization (Eloy et al. Citation2016). The invisibility of local communities other than indigenous groups is also reflected in the fact that hardly any of the news articles distinguishes between smallholders and large agribusiness, commonly using the ambiguous term ‘farmer’ to refer to both groups and thereby erasing stark differences in ways of producing and living as well as associated economic returns and environmental impacts.

In sum, our findings show that asymmetries in efforts to halt forest loss between the two biomes are reflected in stark differences how much attention these have received and how processes of deforestation are framed in Western media. In the case of the Amazon, widespread media coverage, particularly in the 1980s and 2010s, references to poetic discourse in the form of popular depictions of pristine nature, and the use of injustice frames associated with the plight of indigenous groups may have contributed to increased public awareness, international pressure and new governance interventions. However, these frames also proliferate essentialist depictions of local actors, particularly indigenous groups, and may thereby narrow their role in natural resource management to that of protecting native vegetation against any form of local development. Deforestation in the Cerrado biome has largely been met by silence in Western media, mirroring its depiction as empty, barren land prior to agribusiness development. It appears to gain more attention in the past decade through the acknowledgment of its role for biodiversity and climate change. The issue of deforestation here is framed mainly along lines of ecological modernization and corporate governance, which does not leave much room for those traditional populations, who have been marginalized by agribusiness expansion.

6. Conclusions

In this contribution, we have leveraged a text-mining approach combined with qualitative content analysis to analyze the news coverage deforestation in the Amazon and Cerrado biomes has received in Western media. We have shown that the Amazon biome has received disproportionately more attention, particularly in times of international concern about the Brazilian government’s commitment to tackle the issue of deforestation. While Western media frequently report on the struggles of indigenous populations in Amazonia, these narratives mostly follow a rather essentialist depiction of these communities in conflict with other local actors. In the case of the Cerrado, traditional populations are hardly mentioned at all.

Our findings provide an empirically grounded case for the often raised concern over a relative invisibility of the Cerrado biome and its traditional populations when it comes to environmental problems, particularly when compared to the Amazon biome. We highlight that mass mediated public discourse plays a role in the context of disparities in governance interventions. Our findings thereby underline and help explain recent findings on Biome Awareness Disparity, which appears to favor tropical forests over open biomes, and asymmetries in international conservation funding both in terms of geographical preferences and states objectives.

Governance initiatives aiming at reducing deforestation have to be carefully scrutinized in terms of the emphasis they put on specific regions and stakeholders. This is particularly the case when corporate governance initiatives or conservation donors respond to public pressure in Western countries, as a result of increased media attention to deforestation and associated impacts occurring in regions of the Global South.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (1.3 MB)Acknowledgements

The authors wish to express their gratitude to Esteve Corbera for reviewing the manuscript. We would also like to thank the community of open-source package developers for R and Python.

Disclosure statement

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this article.

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/23251042.2022.2106087

Additional information

Funding

References

- Bacchi, C. 2009. Analysing Policy: what’s the Problem Represented to Be? Frenchs Forest: Pearson Education.

- Benoit, K., K. Watanabe, H. Wang, P. Nulty, A. Obeng, S. Müller, and A. Matsuo. 2018. “Quanteda: an R Package for the Quantitative Analysis of Textual Data.” Journal of Open Source Software 3 (30): 774. doi:10.21105/joss.00774.

- Bidone, F., and Z. Kovacic. 2018. “From Nationalism to Global Climate Change: Analysis of the Historical Evolution of Environmental Governance in the Brazilian Amazon.” International Forestry Review 20 (4): 420–435. doi:10.1505/146554818825240656.

- Biermann, F., and P. Pattberg. 2008. “Global Environmental Governance: taking Stock, Moving Forward.” Annual Review of Environment and Resources 33 (1): 277–294. doi:10.1146/annurev.environ.33.050707.085733.

- Core Team, R. 2020. “R: a Language and Environment for Statistical Computing.” Vienna, Austria. https://www.r-project.org/

- da Silva, L. G., and E. F. Chaveiro. 2010. “Desenhando o cerrado: Da invisibilidade à lucratividade.” Geo Ambiente On-line 14: 1–22.

- Dauvergne, P., and J. Lister. 2012. “Big Brand Sustainability: governance Prospects and Environmental Limits.” Global Environmental Change 22 (1): 36–45. doi:10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2011.10.007.

- Dow Jones & Company. 2020. “Factiva.” http://global.factiva.com

- Downs, A. 1972. “Up and down with Ecology - the issue–attention Cycle.” The Public Interest 28: 38–50.

- Dryzek, J. S. 2013 . The Politics of the Earth: Environmental Discourses 3d ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Eloy, L., C. Aubertin, F. Toni, S. L. B. Lúcio, and M. Bosgiraud. 2016. “On the Margins of Soy Farms: traditional Populations and Selective Environmental Policies in the Brazilian Cerrado.” The Journal of Peasant Studies 43 (2): 494–516. doi:10.1080/03066150.2015.1013099.

- Fenzl, T., and P. Mayring. 2017. “QCAmap: eine interaktive Webapplikation für Qualitative Inhaltsanalyse.” Zse 37: 333–340.

- Folke, C., H. Österblom, J. B. Jouffray, E. F. Lambin, W. Neil Adger, B. I. C. Marten Scheffer, and Crona, B. I., et al. 2019. “Transnational Corporations and the Challenge of Biosphere Stewardship.” Nature Ecology and Evolution 3 (10): 1396–1403. doi:10.1038/s41559-019-0978-z.

- Gamson, W. A., B. Fireman, and S. Rytina. 1982. Encounters with Unjust Authority. Homewood: Dorsey Press.

- Gamson, W. A., and A. Modigliani. 1987. “The Changing Culture of Affirmative Action.” Research in Political Sociology 3 (3): 137–177.

- Goffman, E. 1974. Frame Analysis: an Essay on the Organization of Experience. New York: Harper & Row.

- Green, J. M. H., S. A. Croft, A. P. Durán, A. P. Balmford, N. D. Burgess, S. Fick, and T. A. Gardner, et al. 2019. “Linking Global Drivers of Agricultural Trade to on-the-ground Impacts on Biodiversity.“ Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 116 (46): 23202–23208.

- Grimmer, J., and B. M. Stewart. 2013. “Text as Data: the Promise and Pitfalls of Automatic Content Analysis Methods for Political Texts.” Political Analysis 21 (3): 267–297. doi:10.1093/pan/mps028.

- Gualdani, C., and A. S. Fernando Luiz. 2018. “A invisibilidade dos povos do cerrado nos projetos de desenvolvimento e produção de alimentos.” In Dinâmicas territoriais e políticas sociais no Brasil contemporâneo, edited by C. C. Alencar de Sena, D. Castilho, and J. Soares de Freitasgoiânia, 60–64. Goiânia: Editora Kelps.

- Guido, V. R., and F. L. Drake. 2009. Python 3 Reference Manual. Scotts Valley, CA: CreateSpace.

- Habermas, J. 1996. Between Facts and Norms: Contributions to a Discourse Theory of Law and Democracy. Cambridge: Polity.

- Hall, S. 1982. “The Rediscovery of ‘Ideology’; Return of the Repressed in Media Studies.” In Culture, Society and the Media, edited by M. Gurevitch, T. Bennett, J. Curran, and J. Woollacott, 56–90. London: Methuen & Co.

- Hannigan, J. 2006. Environmental Sociology. 2nd ed. London: Routledge.

- Hansen, A. 2015. “Communication, Media and the Social Construction of the Environment. In The Routledge Handbook of Environmental Communication, edited byHansen, A., and Cox, R., 46–58. New York: Routledge.

- Hecht, S. B., and A. Cockburn. 2011. The Fate of the Forest. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Heilmayr, R., L. L. Rausch, J. Munger, and H. K. Gibbs. 2020. “Brazil’s Amazon Soy Moratorium Reduced Deforestation.” Nature Food 1 (12): 801–810. doi:10.1038/s43016-020-00194-5.

- Herndl, C. G., and S. C. Brown. 1996. “Introduction.” In Green Culture: Environmental Rhetoric in Contemporary America, edited by C. G. Herndl and S. C. Brown, 3–20. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press.

- Honnibal, M., and M. Johnson. 2015. “An Improved Non-monotonic Transition System for Dependency Parsing.” In Proceedings of the 2015 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, Stroudsburg, PA, USA, 1373–1378. Association for Computational Linguistics. http://aclweb.org/anthology/D15-1162

- Kleinschmit, D. 2012. “Confronting the Demands of a Deliberative Public Sphere with Media Constraints.” Forest Policy and Economics 16: 71–80. doi:10.1016/j.forpol.2010.02.013.

- Ladle, R. J., A. C. M. Malhado, P. A. Todd, and A. C. M. Malhado. 2010. “Perceptions of Amazonian Deforestation in the British and Brazilian Media.” Acta Amazonica 40 (2): 319–324. doi:10.1590/S0044-59672010000200010.

- Lahsen, M., B. Mercedes M.C, and E. L. Dalla-Nora. 2016. “Undervaluing and Overexploiting the Brazilian Cerrado at Our Peril.” Environment 58 (6): 4–15.

- Mangani, A. 2021. “When Does Print Media Address Deforestation? A Quantitative Analysis of Major Newspapers from US, UK, and Australia.” Forest Policy and Economics 130 (April): 102537. doi:10.1016/j.forpol.2021.102537.

- Mayring, P. 2014. “Qualitative Content Analysis: theoretical Foundation, Basic Procedures and Software Solution.” Klagenfurt: AUT. https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:0168-ssoar-395173

- Mempel, F., and E. Corbera. 2021. “Framing the Frontier – Tracing Issues Related to Soybean Expansion in Transnational Public Spheres.” Global Environmental Change 69: 102308. doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2021.102308. November 2020.

- Miller, S. W. 2007. An Environmental History of Latin America. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Mosco, V., and A. Herman. 1981. “Critical Theory and Electronic Media.” Theory and Society 10 (6): 869–896. doi:10.1007/BF00208271.

- Murphy, P. D. 2017. The Media Commons: globalization and Environmental Discourses. Champaign: University of illinois Press.

- Newell, P. 2001. “Managing Multinationals: the Governance of Investment for the Environment.” Journal of International Development 13 (7): 907–919. doi:10.1002/jid.832.

- Nisbet, M. C., and T. P. Newman. 2015. “Framing, the Media, and Environmental Communication”. The Routledge Handbook of Environment and Communication, edited by A. Hansen and R. Cox, 325–338. Routledge. https://www.taylorfrancis.com/books/9781315887586

- Oliveira, G.L.T., and M. Schneider. 2016. “The Politics of Flexing Soybeans: China, Brazil and Global Agroindustrial Restructuring.” The Journal of Peasant Studies 43 (1): 167–194. doi:10.1080/03066150.2014.993625.

- Park, M. S., and D. Kleinschmit. 2016. “Framing Forest Conservation in the Global Media: an interest-based Approach.” Forest Policy and Economics 68: 7–15. doi:10.1016/j.forpol.2016.03.010.

- Pattberg, P. H. 2007. Private Institutions and Global Governance. The New Politics of Environmental Sustainability. Northampton: Cheltenham.

- Qin, S., T. Kuemmerle, P. Meyfroidt, M. N. Ferreira, G. I. Gavier Pizarro, M. E. Periago, T. N. P. D. Reis, A. Romero‐Muñoz, and A. Yanosky. 2022. “The Geography of International Conservation Interest in South American Deforestation Frontiers.” Conservation Letters 15 (1): 1–10. doi:10.1111/conl.12859.

- Rausch, L. L., H. K. Gibbs, I. Schelly, A. Brandão, D. C. Morton, A. C. Filho, B. Strassburg, et al. 2019. “Soy expansion in Brazil’s Cerrado.” Conservation Letters 12 (6) https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/conl.12671

- Roberts, M. E., B. M. Stewart, D. Tingley, C. Lucas, J. LederLuis, S. K. Gadarian, B. Albertson, and D. G. Rand. 2014. “Structural Topic Models for open-ended Survey Responses.” American Journal of Political Science 58 (4): 1064–1082. doi:10.1111/ajps.12103.

- Roberts, M. E., B. M. Stewart, and D. Tingley. 2019. “Stm: An R Package for Structural Topic Models.” Journal of Statistical Software 91 (2): 2. doi:10.18637/jss.v091.i02.

- Russo Lopes, G., M. G. Bastos Lima, and T. N. P. dosReis. 2021. “Maldevelopment Revisited: Inclusiveness and Social Impacts of Soy Expansion over Brazil’s Cerrado in Matopiba.” World Development 139: 105316. doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2020.105316.

- Sauer, S., and K. R. A. Oliveira. 2021. “Agrarian Extractivism in the Brazilian Cerrado.“ In Agrarian Extractivism in Latin America, edited byMcKay, B. M., Alonso-Fradejas, A., and Ezquerro-Cañete, A., 64–84. London: Routledge.

- Silva, M., and C. Eduardo. 2009. “Ordenamento Territorial no Cerrado brasileiro: Da fronteira monocultora a modelos baseados na sociobiodiversidade.” Desenvolvimento e Meio Ambiente 19: 89–109.

- Silveira, F. A. O., O.-P. Carlos A, C. Livia, I. B. Moura, A. N. Schmidt, W. B. Andersen, B. Elise, et al. 2021. “Biome Awareness Disparity Is BAD for Tropical Ecosystem Conservation and Restoration.” Journal of Applied Ecology. 3. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/1365-2664.14060

- Snow, D. A., and R. D. Benford. 1988. “Ideology, Frame Resonance, and Participant.” International Social Movement Research 1: 197–217.

- Stabile, M. C. C., A. L. Guimarães, D. S. Silva, V. Vivian Ribeiro, M. N. Macedo, M. T. Coe, E. Pinto, A. P. Moutinho, and A. Alencar. 2020. “Solving Brazil’s Land Use Puzzle: increasing Production and Slowing Amazon Deforestation.” Land Use Policy 91: 104362. doi: 10.1016/j.landusepol.2019.104362. September 2019.

- Strassburg, B. B. N., T. Brooks, R. Feltran-Barbieri, A. Iribarrem, R. Crouzeilles, R. Rafael Loyola, A. E. Latawiec, et al. 2017. “Moment of Truth for the Cerrado Hotspot.” Nature Ecology and Evolution 1 (4): 1–3. doi:10.1038/s41559-017-0099.

- Sudhahar, S., G. A. Veltri, and N. Cristianini. 2015. “Automated Analysis of the US Presidential Elections Using Big Data and Network Analysis.” Big Data and Society 2 (1): 1–28. doi:10.1177/2053951715572916.

- Sudhahar, S., G. De Fazio, R. Franzosi, and N. Cristianini. 2015. “Network Analysis of Narrative Content in Large Corpora.” Natural Language Engineering 21 (1): 81–112. doi:10.1017/S1351324913000247.

- Temperton, V. M., N. Buchmann, E. Buisson, G. Durigan, M. P. Łukasz Kazmierczak, D. Perring Michele de Sá, V. Joseph W, and O. Gerhard E. 2019. “Step Back from the Forest and Step up to the Bonn Challenge: How a Broad Ecological Perspective Can Promote Successful Landscape Restoration.” Restoration Ecology 27 (4): 705–719.

- Vieira, P. 2016. “Phytofables: Tales of the Amazon.” Journal of Lusophone Studies 1 (2): 116–134. doi:10.21471/jls.v1i2.112.

- Waldron, A., A. O. Mooers, D. C. Miller, N. Nibbelink, T. S. David Redding, K. J. Timmons Roberts, and J. L. Gittleman. 2013. “Targeting Global Conservation Funding to Limit Immediate Biodiversity Declines.“ Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 110 (29): 12144–12148.

- Wesslen, R. 2018. “Computer-Assisted Text Analysis for Social Science: topic Models and Beyond.” http://arxiv.org/abs/1803.11045

- Zu Ermgassen, E. K. H. J., G. Bastos Lima, H. Bellfield, A. Dontenville, T. Gardner, J. Godar, R. Heilmayr, et al. 2022. “Addressing Indirect Sourcing in Zero Deforestation Commodity Supply Chains.” Science Advances 8 (17): 1–16. https://agrirxiv.org/search-details/?pan=20210399227