ABSTRACT

The rise in research, policy and news on climate change-induced migration has grown exponentially over the last two decades. Migration related to global warming is increasingly portrayed as inevitable and used to mobilise people to act immediately against climate change. By analysing the discourse of two Flemish news media journals (De Standaard and Het Laatste Nieuws) and the Belgian national news agency (Belga), indexed by the GoPress database (1985–2022), this paper aims to present how migration and climate change are linked to each other in the media, how this differs across media outlets, and reflects on potential outcomes of this framing. Results indicate that climate-induced migration is often portrayed in an apocalyptic way and seen as an inevitable threat that needs to be avoided. The used terminology and the portrayals of climate change-induced migration are not in line with the scientific evidence on this topic.

Introduction

Apocalyptic and alarming climate change-induced migration (CCIM) discourses and images have been dominant in research, policies, and media (Bettini Citation2013; Hartmann Citation2010). Only over the last two decades, research on CCIM has risen on the agenda of academics, policy makers and politics (e.g. IPCC Citation2022; McLeman and Gemenne Citation2018; Van Praag and Timmerman Citation2019). This rise of research on CCIM coincided with the urgent call for action to raise awareness on climate change and increasing interest in environmental sociology. Dystopian CCIM views often stemmed from humanitarian and national security discourses that pretended to aim to protect the livelihoods of many people and nations (Bettini Citation2013). Simultaneously, NGOs and all sorts of media stressed the adverse effects of climate change and depict climate mobility as a catastrophe (Roosvall, Tegelberg, and Enghel Citation2020; Sakellari Citation2021; Citation2022; Randall Citation2017). Underlying the need for climate action, media channels often point to the impact it could have on ‘millions of lives’. Hence, migration is depicted as ‘something to avoid’, which further stigmatises migrants, and portrays communities affected by and vulnerable to climate change as ‘victims’ (e.g. Dreher and Voyer Citation2015; Farbotko Citation2005). This paves the way for increasing xenophobic reactions towards migrant populations (Bettini Citation2013; Sakellari Citation2021) and hinders integration of migrants into the immigrant country (Hartmann Citation2010).

Several scholars have criticised the apocalyptic nature of policy and media discourses and the depoliticizing impact it has (e.g. Bettini Citation2013; Giuliani Citation2021). Across the globe, some media discourse analysis on CCIM have been made (Sakellari Citation2021, Citation2022), focusing on one particular group of migrants, such as the low-lying islands in the Pacific (Randall, Citation2017; Roosvall, Tegelberg, and Enghel Citation2020), or on one media location, such as the UK (Sakellari Citation2021). These media discourses do not highlight the complex and interrelated nature of how environmental changes and mobilities are interrelated, nor how they relate to broader conceptualisations of mobility flows, immobilities and mobility of ideas (Boas et al. Citation2019) nor capture the ways in which human mobilities and transportation systems interact with the environment during the Anthropocene epoch (Baldwin, Fröhlich, and Rothe Citation2019).

This paper contributes in two ways to wider debates on the role of media and communication on climate change and migration (Sakellari Citation2021). First, media portrayals are relevant to study as they have long-lasting effects on public opinion and policy making, and future immigration decision-making (Bettini Citation2013; Farbotko Citation2005; Van Praag and Timmerman Citation2019). Comparing articles and media representations across newspapers with different audiences concerning two polarising topics, climate change and migration, could gain insight in media coverage and discourses that are put on or off the political agenda (cf. Bettini Citation2013). In line with this, we will pay additional attention to how the use of specific terminologies – in Dutch – shapes the imaginaries on this topic. In contrast to other settings (Dreher and Voyer Citation2015; Farbotko Citation2005; Jönsson Citation2011; Merkley and Stecula Citation2019), research in Flanders on media coverage and images of migrants and refugees hardly mentioned climate change (d’Haenens, Joris, and Heinderyckx Citation2019). Second, building further on critical approaches to environmental sociology (Carrera Citation2023) and the relationship between human movements and the broader environment (Baldwin Citation2013; Citation2017a; Citation2022), this paper critically looks at how media discourses strengthen societal tendencies and views on how both are related. Our study aims to understand how media discourses represent underlying imaginaries, futures and understandings of the relationship between humans, regions and the broader natural environment, with an eye for exclusion and prevailing power relations in society (see Baldwin Citation2017, Citation2022).

Climate change-induced migration and the media

Following media agenda setting theory, the ways in which the media reports on particular topics shapes people’s attitudes on these matters (Merkley and Stecula Citation2019). The media has a crucial role in defining risks and putting topics on the political agenda (Hansen Citation2010). CCIM lies at the intersection of environmental change and migration; both hot and polarising topics. Therefore, media discourses on CCIM presumably use different framings. CCIM has gained importance as a concept on its own with established definitions and increasing attention in policy and academia, nevertheless, research on media discourses on CCIM remains limited. When looking closer at media discourses, it is important to take the wider context and (inter)national events into account because events enter the media. Additionally, event characteristics and socio-political context influence discourses (Roxburgh et al. Citation2019) which makes it relevant to consider for the analysis. represents a timeline with significant moments in environmental history, such as the first UN conference on the environment and the Paris agreement, alongside natural disasters, such as hurricane Katrina.

This figure highlights the increasing attention paid to climate change in general and CCIM in particular.

Words matter: terminologies to link climate change and migration

Lester Brown’s statement (Worldwatch Institute) in the 1970s is generally seen as the start of the debate on ‘environmental refugees’ which took off in 1985 when El-Hinnawi published a paper titled ‘environmental refugees’. He gave, in contrast to Brown, a definition: ‘those people who have been forced to leave their traditional habitat, temporarily or permanently, because of a marked environmental disruption (natural and/or triggered by people) that jeopardise their existence and/or seriously affects the quality of their life’ (El-Hinnawi Citation1985). Later, scholars, such as Bates (Citation2002), tried to distinguish between migrants and refugees, based on the cause of weather events or trends (e.g. human-made; natural disaster; etc.) and the voluntary nature to migrate. To avoid falling into epistemological discussions, all-encompassing definitions were made to better map out the consequences for people’s livelihoods and how mobility patterns evoked by climate change really look like. The definition of the International Organisation for Migration (IOM Citation2011) of ‘environmental migrants’ is very influential and widely used:

Environmental migrants are persons or groups of persons who, for reasons of sudden or progressive changes in the environment that adversely affect their lives or living conditions, are obliged to have to leave their habitual homes, or choose to do so, either temporarily or permanently, and who move either within their territory or abroad.

This definition was set up to include all migrants affected by environmental change – including climate change. When referring to ‘environmental refugees’, one could avoid terms that are misleading and ‘undermine the international legal regime for the protection of refugees.’ This is especially the case since the concept ‘refugee’ refers to a legally protected group, as defined by the Convention of Genève in 1951 (IOM, 2022Footnote1; Zetter and Morrissey Citation2014). Similarly, displaced persons refer to people that are obliged/forced to move, to further avoid consequences of conflicts, human rights violations or disasters. The use of this term could shape imaginaries on risk and vulnerabilities (Askland et al. Citation2022). Persons affected or categorised as such, have reflected on the used categorizations, as was the case for Pacific ambassadors at the United Nations (McNamara and Gibson Citation2009) or people affected by Hurricane Katrina (Gemenne Citation2010) and did not embrace the existing terminologies used.

Debates concerning CCIM have centred around the correct terminology to denote the mobility impacts of climate change – and by extension environmental change. This resulted in an amalgam of terms, including ‘environmental migrant’, ‘climate change-induced migrant’, ‘climate refugee’, ‘ecological refugee’, ‘environmental refugee’, ‘forced environmental migrant’, ‘environmentally motivated migrant’, ‘environmentally displaced person’, ‘disaster refugee’, ‘environmental displacee’, ‘eco-refugee’, ‘ecologically displaced person’, or ‘environmental-refugee-to-be’ (IOM, Citation2011). Although the concept ‘migrant’ often includes all subterms, for this discourse analysis, we are interested in understanding how these different terms are used in media discourses. Terminology use can lead to racialisation and othering, therefore some argue in favour of alternative terminology usage, which is needed to ‘rehumanise those carrying the heaviest social and climate burdens on a burning planet’ (Hiraide Citation2023, 267).

While the use of such terminology is carefully reflected upon in academia and policy (e.g. McLeman and Gemenne Citation2018), the outcomes of these debates are not necessarily reflected in media discourses. Anglophonic academic discourses do not always find an easy translation into local languages, such as Dutch, which results in easier to use terms, such as ‘climate migrant(s)’ [klimaatmigrant(en)] and ‘climate refugee(s)’ [klimaatvluchteling(en)]. ‘Environmental migrant(s)’ [omgevingsmigrant(en) or milieumigrant(en)] would be considered vague in Dutch. Besides, the differentiation between ‘natural environment’ and ‘climate’ is not commonly used in Dutch. ‘Climate change’ [klimaatveranderingen] or ‘climate-induced’ [klimaatgeïnduceerd] are terms hardly connected to migration in everyday usage given the longitude of the expression. Therefore, it is relevant to understand how these terminologies and discourses find their entry in non-English speaking, popular and media discourses and debates, such as the Flemish press, which are bound to local, everyday language use.

Perspectives and framings of climate-change induced migration

CCIM has sparked a lot of debates ever since the concept of ‘environmental refugee’ was used for the first time. Myers (Citation1997) has published various influential articles warning for vast numbers of environmental refugees, stating already in 1997 that there are ‘at least 25 million environmental refugees today’. These alarmist numbers have been criticised by various authors who don’t find evidence for such numbers and call them ‘guesstimates’ (Durand-Delacre et al. Citation2021; Kolmannskog Citation2008). Additionally, several scholars argue that various factors – economic, political, environmental etc. - push people to migrate, which makes it hard to put a number on environmental refugees (Bates Citation2002). The mixed evidence can be the result of a vast range of case studies and geographic regions (Obokata, Veronis, and McLeman Citation2014). Nevertheless, there seems to be a consensus that CCIM mostly results in internal displacement rather than international migration (McLeman and Gemenne Citation2018).

To continue, most CCIM research has been conducted in countries in the Global SouthFootnote2 (GS), Sub-Saharan Africa in particular. Similarly, media discourses on CCIM focus mostly on specific geographic regions in the GS, such as low-lying islands in the Pacific Ocean (Dreher and Voyer Citation2015; Farbotko Citation2005). Europe on the contrary is not studied at all (Obokata, Veronis, and McLeman Citation2014), yet also Europe experiences adverse effects of climate change. This could lead to the racialised othering of environmental refugees (Baldwin Citation2022; Giuliani Citation2021). By assigning environmental factors, which are so-called ‘neutral’, as the cause of migration, socio-political origins are ignored or simply denied (Hiraide Citation2023). Often framed as passive victims, regions at risk’s agency to determine their own fate gets undermined (Dreher and Voyer Citation2015; McNamara and Gibson Citation2009). This conclusion arises also from various media discourse analyses on CCIM. For instance, Farbotko (Citation2005) analysed the discourses on communities living in Tuvalu in the Sydney Morning Herald and found that they are mainly portrayed as ‘victims’, leaving less space for resilience and their own identity constitutions. Sekallari (Citation2021) focuses on how discourses in online news in the UK approach climate change and migration. Her findings indicate that UK media mainly focuses on catastrophes and crises that will result from mass migration related to climate change. The authors argue that such media coverage stimulates securitisation concerning CCIM and presumes that migration automatically results in conflicts and instability. Last, Methmann (Citation2014) did a visual analysis of environmental refugees and concluded, based on 135 images from newspapers, websites and publications, that environmental refugees are portrayed as the racialized ‘Other’ and climate change is presented as an all-encompassing threat that gets depoliticized. In these discourses, environmental refugees are represented as security threats, passive victims, abstractions and hardly as activists (see also Giuliani Citation2021).

As CCIM combines climate change and migration, it is relevant to look closer into media discourse on climate change on the one hand, and migration on the other hand. Over the last decades, increasing attention has been given on how climate change is communicated. For instance, Jönsson (Citation2011) concluded that the Swedish newspaper Dagens Nyheter in their framing of environmental risks in the Baltic Sea mainly focuses on the largest threats. Merkley and Stecula (Citation2019) analysed American news media content from 1988 to 2014 and observed that economic benefits of climate action are increasingly highlighted. Similarly, risks and dangers associated with environmental change are stressed, and present tense is used more. Other discourse analyses find that the ‘climate change frame’ or ‘IPCC frame’ - humans cause climate change and we need to reduce emissions – are mostly prevalent in media (Shehata and Hopmann Citation2012), although interpretive climate journalism, which ‘puts the denial of anthropogenic climate change into context’ is becoming more common (Bruggeman and Engesser Citation2017).

To continue, refugees and/or migrants have been subject of various media discourse analyses. The issue is referred to in terms of ‘crisis’ (De Cock et al. Citation2018), ‘victimhood’ (Smets et al. Citation2019) or framed by using specific images (d’Haenens, Joris, and Heinderyckx Citation2019). Most of these articles focus on one particular aspect or topic (e.g. Syrian migration situation, De Cock et al. Citation2018). Important differences are found across media outlets, countries and settings. For instance, De Cock and colleagues (Citation2018) studied refugee representations in Belgian and Swedish Newspapers during the European refugee situation during summer 2015. They found considerable regional variation in news coverage within Belgium. Both in Sweden and in francophone Belgium, journalists tend to write in a more tolerant way about refugees, compared to Flanders. Again, in this media discourse analysis, the voices of refugees were hardly taken into account nor represented in the media.

Methods

This paper explores the discourses and usage of CCIM in Flemish (Dutch-speaking) print media by analysing media coverage of three cases between 1985 and 2022: Belga, the national Belgian Press Agency, and two different Flemish newspapers, De Standaard (DS) and Het Laatste Nieuws (HLN). Written press has more power to be selective in their reporting and reflect about their wording (Gabrielatos and Baker Citation2008) which is more suitable for this analysis. DS, HLN and Belga were selected based on the variation in type of newspaper (‘popular’ vs ‘quality’; De Cock et al. Citation2018; Joris, d’Haenens, and Van Gorp Citation2014) and press group. First, quality newspapers tend to have longer and more detailed articles adopting straightforward language, while popular press uses emotive and sensational language in shorter stories (Loisen and Joye Citation2016). DS is considered a ‘quality’ newspaper, HLN is ‘popular’ media and Belga is the main provider of news to Belgian media. Both newspapers are the most read in their genre. Between June 2019-May 2020, DS had 308,542 surfers to their website 35,917 daily surfers to their app and a print run of 78,099 between January and October 2019. HLN (+ Nieuwe Gazet) had in the same periods 1,127,148 daily surfers to their website, 442,966 daily app users and a print run of 241,727Footnote3 (CIM Citation2022). Second, HLN is part of DPG Media and the DS of Mediahuis; different press groups ensure less overlapping content (e.g. Hendrickx and Van Remoortere Citation2021). Both a comparison between media outlets and over time was made. All articles from 1985 until 31 May 2022 were searched; however, the first time one of the indicated terms was used was in DS on 25 June 1999.

The articles were retrieved by searching the GoPress database (see: Hendrickx and Van Remoortere Citation2021). GoPress is the online press database and press monitoring service of all Belgian newspaper and magazine publishers,Footnote4 containing entire articles but no pictures. The search included the following search terms: ‘klimaatmigrant(en)’ [climate migrant(s)], ‘klimaatmigratie’ [climate migration] (both will be discussed in the text under the heading of CM) and ‘klimaatvluchteling(en)’ [climate refugee(s)] (CR). The search strategy was limited since no (compact) alternative terms for ‘environmental refugees’ or ‘climate induced refugees’ exist in Dutch. We did an explorative search for the terms ‘omgevingsmigrant(en)’ and “milieumigrant(en) [environmental migrant(s)] and ‘omgevingsvluchteling(en)’ and ‘milieuvluchteling(en)’ [environmental refugee(s)] (ER), ‘anthropocene mobility’ as well as a search for ‘klimaat en migrant’ [climate AND migrant] to check terminology used in Dutch. We excluded articles referring to ‘refugees’ in a metaphorical way (e.g. to walruses or historical groups, such as the Maya). Last, we correctly categorised the retained articles using the DS and HLN websites. All articles were screened by the first author to check their eligibility.

Data analysis occurred in a systematic way, starting with the exclusion of articles. All articles were coded in Nvivo. Recurring themes referred to geographic areas/countries/continents (e.g. Global North/South; Australia, Belgium, Europe, Oceania, etc.), gender, climate adaptation/mitigation, alarmist nature of messages; migration-related issues (e.g. refugees; migration flows, etc.), statistics. Each article was coded per newspaper to facilitate comparison per newspaper. During the coding process and analysis, the authors systematically looked at changes over time. Based on an initial coding of recurring themes, a reflexive approach towards the grouping of these articles was applied to further reflect upon prevailing discourses and trends in the data.

Results

Descriptives

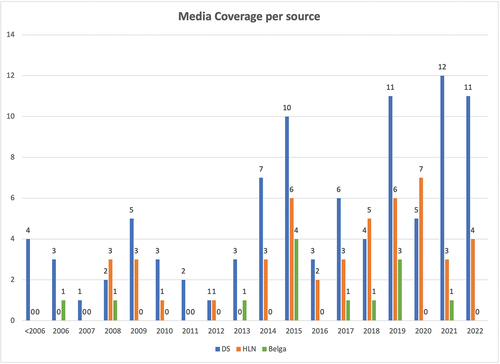

In total, 153 articles were identified (after duplicates and correction articles) of which 47 from HLN, 93 from DS and 13 from Belga. The first identified article (25/06/1999, DS) is a Red Cross report warning of ‘super disasters’: ‘Natural disasters caused more refugees than conflicts last year. Declining soil fertility, drought, floods and deforestation drove 25 million environmental refugees [milieuvluchtelingen] from their lands into the slums of fast-growing cities.’ The term ‘klimaatvluchteling’ [CR] appeared for the first time (17/08/2002) also in DS, in an opinion piece portraying an apocalyptic future scenario: ‘The invasion of climate refugees [klimaatvluchtelingen], who will flood Europe in this summer of 2050 after a devastating series of cyclones in Asia.’ Only four years later, in 2006 after hurricane Katrina, ‘klimaatvluchteling’ appeared again in DS and for the first time in Belga. HLN followed a bit later, with the first media coverage on CCIM in 2008. represents the media coverage over time by DS, HLN and Belga. It is clear from the graph that CCIM terminology is most prominent in DS every year except for 2020. Surprisingly, 2020 was one of the most covered years for HLN, despite limited migration processes due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Furthermore, all three sources saw an increase over time, most noticeable for DS. 2015, 2019 and 2021 were the most covered years with a total of respectively 20, 19 and 16 articles. DS yields the most articles (93) compared to HLN (47) and Belga (13). Different types of articles cover the issue of CCIM. Most of the pieces can be placed within the categories of regular news, opinion pieces, which include columns and reader’s letters, and interviews. Opinion pieces and interviews are not part of Belga’s output.

Terminology use: how and when?

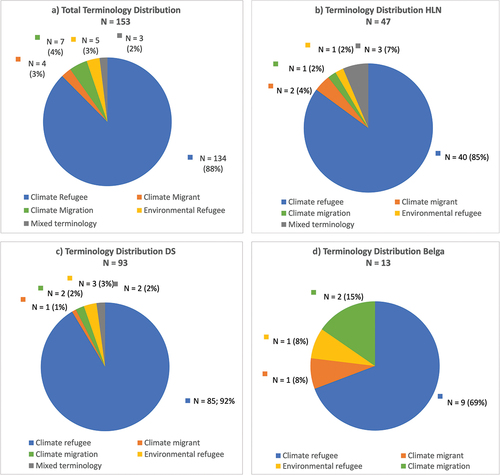

represents the overall distribution of the terminology (part A) and the terminology distribution in each media source (part B – D). It is apparent that media prefers to refer to CCIM in terms of ‘refugees’ instead of ‘migrants’ or ‘migration’. ‘Climate refugee(s)’ [CR] appears in 134 articles. In contrast, only 4 articles use ‘climate migrants’ [CM], 7 use the term ‘climate migration’, 5 articles adopt ‘environmental refugees’ and 3 articles mix different terms; this could indicate that no real thought is given to the difference between migrant and refugee. Belga doesn’t mix terminology. Relatively, DS uses ‘CR’ the most (92%) compared to HLN (85%) and Belga (69%). The usage of the other terminology is quite similar between the different sources. Overall, there is no difference in terminology used between the different newspapers; they use CR [klimaatvluchteling], CM [klimaatmigrant] and ER [milieuvluchteling] to the same extent. The higher percentage of CR for DS is likely due to the bigger sample. The terms ‘omgevingsmigrant’ [EM], ‘omgevingsvluchteling’ [ER] and ‘milieumigrant’ [EM] were never used in any of the three sources, while ‘milieuvluchteling’ [ER] appeared in a total number of 5 articles. This is not in line with the growing trend in academic research to preferably refer to ‘environmental migration’ instead of ‘CCIM’ in order to prevent debates on the origins of specific weather events and phenomena (McLeman and Gemenne Citation2018). Yet, due to translations and the nature of Dutch, it is not possible to make concluding remarks. There were overall no differences found in articles that used ER compared to articles using CR; in both cases they were mentioned within climate change topics, politics and estimates of CCIM. An in-depth comparison between articles that used CM and CR is not possible, since the small sample of articles adopting migrant terminology. The refugee labelling can also be used to underpin the apocalyptic framing of CCIM, as it emphasises the danger that people face in their country of origin.

Figure 3. Overall distribution of the terminology (part A) and the terminology distribution in each media source (part B – D).

CCIM terminology appears within different contexts that can be understood and situated within broader societal matters (see ). All media sources adopt discourses closely linked to the contexts of climate (change), migration and CCIM itself. First, CCIM is often the main theme of newspaper articles: media publishes studies on estimates of CR (‘Climate change could push 216 million people to migrate by 2050’ (Belga, 13/09/2021)) and reports about the refugee status of CR (‘Climate refugee’ from Kiribati refused asylum in New Zealand” (Belga, 26/11/2013)). To continue, CCIM, when not the main subject of an article, is often mentioned in the broader context of climate change. Similar to Merkley and Stecula (Citation2019), dangers and risks are usually at the centre of these pieces; by adding CCIM in the list of adverse climate change effects, CCIM is implicitly depicted as an undesirable prospect. This framing often pops up after climate events or new IPCC reports, the COPs in Copenhagen (2009), Paris (2015) and Glasgow (2021) in particular sparked the debate on CR further:

In less than two weeks, a new climate summit for which expectations are high will start in Glasgow. This report once again highlights the disproportionate vulnerability of the African continent to climate change. Floods, landslides and droughts are already leading to greater food insecurity, more poverty and more climate refugees [klimaatvluchtelingen]. (Belga, 19/10/2021)

Last, refugee framings were quite prominent. For example, the context of the Syria Refugee Crisis in 2014–2015, provoked a debate about other types of refugees like CR:

The problem, however, is that we have no instruments for receiving war refugees, only an asylum procedure intended for persecuted individuals. We already know that in a few years’ time a new wave will come our way, the climate refugees [klimaatvluchtelingen]. (DS, 12/12/2015)

Here, the future scenario of CR is put in parallel with the then present big influx of war refugees; it will also be a ‘wave’ nobody is prepared for.

“Climate refugees” in the Global North and South

An important matter to take in mind is who is framed as CR within Flemish written press. Low-lying islands in the Pacific Ocean such as Kiribati and Tuvalu (McNamara and Gibson Citation2009) are used as textbook examples of CCIM due to sea level rise. This contrasts to broader studies on environmental migration and how environmental changes affect people’s lives and livelihoods. Hurricane Katrina for example, occurred in the Global North (GN); its long-term effects were especially felt through its disproportionate impact on people’s lives, reinforcing existing social inequalities (McLeman, Schade, and Faist Citation2016). This tension is visible in Belga and DS that refer to the ‘victims’ of hurricane Katrina in 2005 as the ‘first Western’ climate refugees based on statements of Lester Brown (see McLeman, Schade, and Faist Citation2016). ‘Katrina created the first Western climate refugees [klimaatvluchtelingen]. A quarter of a million inhabitants never returned to the city, mainly blacks’ (DS, 21/03/2009). People involved are often portrayed as CR and victims, regardless of their own preferences; although Gemenne (Citation2010) found that the affected people often preferred to be called ‘survivors’ or ‘evacuees’.

Inhabitants of low-lying islands of the Pacific, like Kiribati, based in the GS, get the label of ‘first climate refugees’ too, yet in a context of refugee status and legal recognition. ‘A Kiribati resident has applied for asylum in New Zealand because his Pacific Island group is threatened by rising sea levels. If successful, 37-year-old Ioane Teitiota will become the world’s first climate refugee [klimaatvluchteling]’ (Belga, 19/10/2013). The naming of the inhabitants of the islands of the Pacific as first refugees doesn’t contradict the label of the victims of Katrina, as they are the first ‘Western’ refugees. This sets the GN apart from the GS, a quite prominent tendency in media discourses on CCIM. Yet, academic research demonstrates that Pacific Islanders also resist the category of CR (McNamara and Gibson Citation2009). This vision is not reflected in the media; low-lying islanders are mostly framed as passive victims waiting for the moment to leave. Countries that would receive these islanders (Australia, New Zealand and European countries) are resisting: ‘In a worst-case scenario, residents would have to relocate, but neither Australia nor New Zealand is eager to receive thousands of climate refugees [klimaatvluchtelingen]’ (DS, 31/12/2010). De Cock et al. (Citation2018) demonstrated that during the Syria Refugee Crisis, “other actors – mostly politicians – are quoted and paraphrased much more frequently than the actual protagonists’’ (p.320); this is also the case in media discourses on CCIM. Politicians, experts, activists are cited or have a voice in the media, while people labelled as CR, don’t get the chance to resist their label.

Especially the Pacific Islands, South-East Asia and Africa are framed as (possible) CR. Apart from the victims of hurricane Katrina, it is noticeable that people from the GN, in contrast to the GS, are rarely framed as CR. This can lead to the further racialisation of refugees (Baldwin Citation2022; Hiraide Citation2023). Yet there has been a remarkable change in the framing of the GN; from 2015 on, the possibilities of the GN in becoming CR too is used as a warning and an apocalyptic future scenario: ‘Because one day we will be climate refugees [klimaatvluchtelingen] ourselves’ (DS, 20/02/2021). Yet, the GN is mostly framed as ‘only’ at risk: ‘A rise in sea levels, more and more intense heat waves, more floods and, on the other hand, more periods of drought and storms. These are the consequences that Europe will feel from climate change’ (Belga, 25/01/2017). The framing of ‘us’ as CR is especially used in opinion pieces and interviews. In other cases, some Belgian individuals identify themselves as CR as they leave Belgium for climate-related reasons but don’t define themselves as such.

Belga, DS and HLN, to a lesser extent, report studies on estimates of CCIM. The estimates range from 100 million to a billion by 2050 and are sometimes the main topic of articles, sometimes just a number. Sources of these estimates are rarely named, which makes it impossible for the reader to know where this number comes from: ‘Not only could this lead to 100 million climate refugees [klimaatvluchtelingen] in the region, but food prices will also rise sharply’ (DS, 09/10/2021). When the sources are mentioned, they vary from international level sources like the IOM, ‘Global climate change could trigger a refugee influx of 200 million by 2050, warns a report by the International Organisation for Migration presented yesterday’ (HLN, 11/06/2009), to civil society actors like Greenpeace. Moreover, academic studies find their way to the media, ‘Global warming could well result in 200 million climate refugees [klimaatvluchtelingen] in thirty years’ time. […] Greenpeace bases this on the study of a professor at the University of Hamburg’ (Belga, 19/06/2007). As pointed out by the literature, there are several problems with estimates of CR (Gemenne Citation2011). First, definitions of CR remain vague or are absent in media coverage. This is nonetheless important since more encompassing definitions also entail larger estimates. In a few exceptions, more information is included: ‘In total, 23.5 million new climate refugees [klimaatvluchtelingen] were counted last year. According to Oxfam, this figure may be an underestimate: people fleeing weather phenomena such as drought and rising sea levels were not counted’ (Belga, 02/11/2017).

Further, not a single article elaborates on the methodology behind these numbers. ‘Guesstimates’ of CR often receive criticism to be extremely high and alarmist (Kolmannskog Citation2008) so these numbers can be used for strategic goals. This criticism is applicable in this discourse analysis too, since it is not clear why certain studies have been chosen as a source of information. The IOM is a well-known international institution, ‘a professor at the University of Hamburg’ (Belga, 19/06/2007) as quoted above, remains vague; it is plausible that these sources get selected because of the alarmist numbers.

The interests behind “climate refugees”

CCIM is often used strategically by different stakeholders for diverse interests; the literature often distinguishes the interests of climate and environmental protection alongside security (Bettini Citation2013). First, CCIM has become an extra argument for why we should combat climate change: besides floodings and rising temperatures, CR will have to flee their homes. CR are implemented in the ‘climate change frame’ or ‘IPCC frame’ (Shehata and Hopmann Citation2012), as shown in the following quote:

They are asking an Australian federal court to order Canberra to ‘reduce greenhouse gas emissions to a level that avoids the Torres Strait islanders becoming climate refugees’ [klimaatvluchtelingen]. (Belga, 27/10/2021).

Further, the securitisation discourse which frames migration as the cause and consequence of conflict, is also prominent and is reflected through civil society (organisations), national governments, international institutions. This discourse could also be seen as a highlighting of the risks linked to climate change (Merkley and Stecula Citation2019).

Climate change could lead to conflicts over energy supplies, political radicalisation and a flood of ‘climate refugees’ [klimaatvluchtelingen] in the coming years. EU summit leader Javier Solana wants to prepare Europe for this with a new document on climate change and international security. (HLN, 11/03/2008)

To continue, CCIM have become an argument in underpinning the need for development aid:

Why is no similar cost-benefit analysis made for the Flemish Climate Plan? The costs are known. The benefits: control of the drought risk and agricultural damage, reduction of the additional flood risk, improved air quality, fewer traffic jams and a smaller chance of mass climate migration [klimaatmigratie]. (DS, 21/02/2020)

In a similar way, stakeholders use the framing of CCIM in the GS to strengthen the notion of ‘climate justice’, which addresses the unequal distribution of responsibilities and burdens of climate change (Bettini, Nash, and Gioli Citation2017); the GN is responsible for environmental degradation yet the GS has to bear the consequences, they even have to flee their homes (Gemenne Citation2015). This makes CCIM relevant for the GN within the UN-notion of ‘common but differentiated responsibilities’ (UNFCCC Citation1992): ‘Hundreds of millions of people will suffer the disastrous consequences of climate change. Unfortunately, the burden and suffering are linked to income: the poorest people are hit the hardest.’ (DS, 05/04/2019). Even more, CR have become instrumental in demanding rights for all refugees within a more general ‘justice’ perspective:

I would like to ask the politicians here, who only want to solve problems for which they are to blame, what they will say when the climate refugees arrive in Maximilian Park,Footnote5 because their villages are flooded, their fields are destroyed, their crops are ruined by yet another heat wave. (DS, 15/09/2015)

The distinguished interests all depict a doom scenario; the world will become uninhabitable due to climate change; conflict and extreme poverty will be omnipresent. The media warns of this, because ‘if no action is taken on the climate, we will have climate refugees as well as war refugees’ (Belga, 23/11/2015). This apocalyptic framing is strengthened by the estimates of ‘millions of CR’. In other articles, there is a clear undertone of anxiety and concern:

There is therefore every reason to be very concerned […] This is the world in which the children being born today will grow old. A world of uncertainty, chaos, conflict and climate refugees (DS, 08/02/2014).

By doing so, these discourses continuously underline the recurrence of colonial and racialised discourses in these political and media discourses (see also Baldwin Citation2013; Citation2017a; Citation2022).

These doom scenarios are most explicitly reflected in opinion pieces and interviews, although environmental studies by institutions and civil society reflects the same tone. Furthermore, it becomes evident that CR found their way to the cultural sector too. Belga and DS speak about the rise of ‘climate fiction’ as a new literature genre:

A (relatively) new literary genre is making its presence felt at the Buchmesse, the Frankfurt book fair. The genre is called “climate-fiction”, abbreviated to “cli-fi”, and its theme, or if you like its main motif, is global warming. (Belga, 12/10/2018).

DS, HLN and Belga: what’s the difference?

Based on the differences between ‘popular’ and ‘quality’ press, media coverage on CR by DS is expected to be longer, more factual, straightforward and less sensationalist than HLN. The popular press is expected to report more stories of direct concern and local news (Sparks Citation1988). A common conception is that popular newspapers pay more attention to migration, yet research has demonstrated that HLN reported less on immigration topics than DS (Walgrave and De Swert Citation2004).

Both DS and HLN presented doom scenarios on a regular basis and made a prognosis of a chaotic future: ‘+6° All life on earth has been destroyed’ (HLN, 21/10/2011). The scientific basis of these projections is most of the time missing. Besides, HLN does report more on local matters like the following: ‘The inhabitants of Hingene (Bornem)Footnote6 have given their crib an original decoration this year (…): “To open up the theme more widely, we hung pictures of World War I refugees and climate refugees in the nativity scene”’ (HLN, 16/12/2015).

Although HLN did report on hurricane Katrina, it never refers to CCIM. Further, HLN, in contrast to Belga and DS, doesn’t report on the status of CR but only mentions it briefly in two articles. This is evidence for the less in-depth approach to CCIM when comparing popular and quality press. Last, Belga reports significantly more estimates of CR; 8 articles are purely on the estimates while this is the case with only 2 and 1 article of DS and HLN respectively. Since Belga publishes no interviews and opinion pieces, we can conclude that Belga is a more purely informative source, yet it is important to notice that the apocalyptic framing is also present here.

Discussion

How CCIM is framed in popular media matters for action undertaken for solidarity with migrants, for climate adaptation and political action (Bettini Citation2013). Based on our analysis, four main conclusions can be drawn. First, over time, CCIM terminology has become increasingly more widespread and used in different contexts. Despite similar portrayals of CCIM across newspapers, relatively more references were made to CCIM in DS, compared to HLN. A high number of newspaper articles using the term ‘climate refugee’, which does not conform to the scientific evidence, nor policy guidelines (e.g. of the IOM), nor does it capture critical and more philosophical reflections on the relationship between human movement and the natural environment (Baldwin Citation2022). Due to translation issues and the activism of many NGOs, the term ‘environmental refugee’ was only used in seven articles between 1999 and 2009; CR as a term has taken the upper hand.

Second, CCIM is mostly mentioned as a consequence of climate change, neglecting common migration dynamics when confronted with environmental changes (Gemenne Citation2010; McLeman and Gemenne Citation2018). Many of these articles assume that migrants are coming to Flanders/Belgium, without considering the migration possibilities and obstacles and immobility preferences (McLeman and Gemenne Citation2018). This way, CCIM becomes merely a tool to mobilise people for climate action, justifying migration policies (or the lack thereof) and climate policies. In contrast to the portrayal of CCIM as a call for climate action and/or securitization, especially in DS, references were made to specific events, such as Hurricane Katrina, that gave rise to migration (e.g. McLeman et al. Citation2006; Gemenne Citation2010).

A third finding is that journalists, policy makers and scientists often use ‘guesstimates’ and ‘millions of climate refugees’. Migration is portrayed in an apocalyptic way, presented as a threat and catastrophe (Giuliani Citation2021, Randall, Citation2017; Roosvall, Tegelberg, and Enghel Citation2020; Sakellari Citation2021, Citation2022). By stressing the need to secure oneself from migrant invasions and ‘high numbers of refugees/migrants’, the analysed media articles reinforce prevailing ideas on securitization processes (Bettini Citation2013), the deservingness of the exploitation of natural resources as well the expelling of greenhouse gases which further shape future policies and imaginations (Giuliani Citation2021), xenophobic attitudes and thoughts (Bettini Citation2013) and migration decision-making (Van Praag and Cheung Citation2024). Discourses that frame global warming as something that is about to happen in the ‘near’ future ignore the impacts felt today.

Finally, people confronted with climate change are often framed as passive victims, reducing their voices as they are never, nor their opinions, included in the articles (Dreher and Voyer Citation2015; Farbotko Citation2005). Hence, no attention is given to alternative options to migration (Farbotko Citation2005), immobilities and other types of mobilities (Boas et al. Citation2022) or more critical reflections on the relationship between human movement and the environment (cf. ‘anthropocene mobilities’, Baldwin, Fröhlich, and Rothe Citation2019). This is partially due to the prophetic/apocalyptic nature of these news articles, suggesting that for now, no CCIM are present. Hence, these discourses assume and hint at an entirely ‘new categorisation’ of potential migrants as CCIM. Doing so, these discourses downplay the interaction of environmental factors with other drivers of migration, such as economic, political and family ones, and reinforce discourses on the ‘deservingness’ of migrants (e.g. De Coninck Citation2020). These discourses further reinforce the existing racial power relations across the globe and don’t challenge existing international political debates nor practices (Baldwin Citation2022).

Future studies could include an analysis of visual representations. Additionally, given the descriptive nature of Dutch language, using multiple words to describe phenomena; it is possible that articles don’t explicitly use ‘climate refugee’, but talk about ‘people that have to flee their homes because of climate change’. Further research could include more geographic terms to delve deeper into these phenomena. Media policies could learn from our study by including more voices in media discourses (e.g. De Cock et al. Citation2018; Farbotko Citation2005; Gemenne Citation2010). This could result in a more nuanced understanding of migration and representation of (environmental) migrants. These debates furthermore need to reflect on prevailing racialised power relations across the globe, the portrayal of migrants as the ‘racialized Other’ (Baldwin Citation2017, Citation2022) and environmental citizenship (Baldwin Citation2013). Additionally, we didn’t find ways in which the Flemish press reported about scholarly debates (e.g. Durand-Delacre et al. Citation2020, Citation2021), which requires a more in-depth analysis of more alternative sources and opinion pieces. Finally, the popular usage of ‘climate refugee’ in the Flemish press could work counterproductive, biassing the scientific knowledge on environmental mobility by a lay audience and giving rise to securitization debates (Bettini Citation2013). Given the alarmist nature of most of these depictions, it could further depoliticise this topic (Bettini Citation2013; Giuliani Citation2021; Methmann Citation2014) or paralyse all mobilisation to support environmental migrants.

Conclusion

We conducted a critical discourse analysis in which we reflected on recurring themes based on written news media articles in two Flemish newspapers, DS and HLN, and the Belgian news agency Belga, using GoPress. All three cases depict CCIM as something inopportune that should be always avoided. Nevertheless, CCIM is questioned in only two pieces in DS; reflecting on the definition and estimates of CCIM, and financial resources needed to migrate. All three sources use apocalyptic framing and use securitisation and environmental discourses. Yet, DS reports significantly the most on the issue of CCIM, Belga publishes the most studies on estimates of CCIM and HLN pays more attention to local initiatives. The findings of this paper highlight the increasing use of the term ‘climate refugee’ over other terms, combined with ‘guesstimates’ and depicting these migrations as extremely numerous. This further neglects the underlying migration dynamics in which climate and environmental changes interfere. In doing so, people are often considered as ‘vulnerable’ and ‘passive actors’, ignoring their agency.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Isaura Bonneux

Isaura Bonneux (Master) is a PhD student at the University of Antwerp. Her research interests are energy economics, social perspectives on the environment and urban studies. https://orcid.org/0009-0009-8597-267X

Lore Van Praag

Lore Van Praag (Master, PhD Ghent University) is Assistant Professor at the Erasmus University of Rotterdam. Her research interests are social and ethnic inequalities, transnationalism, migration, environmental change, and diversity. https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2861-7523

Notes

2. The Global North refers to the regions of Europe, North America and Australia. The Global South refers to Latin-America, Africa, Asia and Oceania.

5. Park in Brussels where many refugees stay and sleep at night.

6. Small city in Flanders.

References

- Askland, H. H., B. Shannon, R. Chiong, N. Lockart, A. Maguire, J. Rich, and J. Groizard. 2022. “Beyond Migration: A Critical Review of Climate Change Induced Displacement.” Environmental Sociology 8 (3): 267–278. https://doi.org/10.1080/23251042.2022.2042888.

- Baldwin, A. 2013. “Racialisation and the Figure of the Climate-Change Migrant.” Environment & planning A 45 (6): 1474–1490.

- Baldwin, A. 2017. “Resilience and Race, or Climate Change and the Uninsurable Migrant: Towards an Anthroporacial Reading of ‘Race’.” Resilience 5 (2): 129–143. https://doi.org/10.1080/21693293.2016.1241473.

- Baldwin, A. 2022. The Other of Climate Change: Racial Futurism, Migration, Humanism. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield.

- Baldwin, A., C. Fröhlich, and D. Rothe. 2019. “From Climate Migration to Anthropocene Mobilities: Shifting the Debate.” Mobilities 14 (3): 289–297. https://doi.org/10.1080/17450101.2019.1620510.

- Bates, D. C. 2002. “Environmental Refugees? Classifying Human Migrations Caused by Environmental Change.” Population and environment 23 (5): 465–477.

- Bettini, G. 2013. “Climate Barbarians at the Gate? A Critique of Apocalyptic Narratives on ‘Climate refugees’.” Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences 45:63–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2012.09.009.

- Bettini, G., S. L. Nash, and G. Gioli. 2017. “One Step Forward, Two Steps Back? The Fading Contours of (In)justice in Competing Discourses on Climate Migration.” The Geographical Journal 183 (4): 348–358. https://doi.org/10.1111/geoj.12192.

- Boas, I., C. Farbotko, H. Adams, H. Sterly, S. Bush, K. Van der Geest, and M. Hulme 2019. “Climate Migration Myths.” Nature Climate Change 9 (12): 901–903.

- Boas, I., H. Wiegel, C. Farbotko, J. Warner, and M. Sheller. 2022. “Climate Mobilities: Migration, Im/Mobilities and Mobility Regimes in a Changing Climate.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 48 (14): 3365–3379. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2022.2066264.

- Brüggemann, M., and S. Engesser 2017. “Beyond False Balance: How Interpretive Journalism Shapes Media Coverage of Climate Change.” Global Environmental Change 42: 58–67.

- Carrera, J. S. 2023. “Advancing Du Bois’s Legacy Through Emancipatory Environmental Sociology.” Environmental Sociology 9 (4): 349–365.

- CIM. 2022. [Online]. https://www.cim.be/nl.

- De Cock, R., S. Mertens, E. Sundin, L. Lams, V. Mistiaen, W. Joris, and L. d’Haenens. 2018. “Refugees in the News: Comparing Belgian and Swedish Newspaper Coverage of the European Refugee Situation During Summer 2015.” Communications 43 (3): 301–323. https://doi.org/10.1515/commun-2018-0012.

- De Coninck, D. 2020. “Migrant Categorizations and European Public Opinion: Diverging Attitudes Towards Immigrants and Refugees.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 46 (9): 1667–1686. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2019.1694406.

- d’Haenens, L., W. Joris, and F. Heinderyckx. 2019. Images of Immigrants and Refugees in Western Europe. Leuven: Leuven University Press.

- Dreher, T., and M. Voyer. 2015. “Climate Refugees or Migrants? Contesting Media Frames on Climate Justice in the Pacific.” Environmental Communication 9 (1): 58–76. https://doi.org/10.1080/17524032.2014.932818.

- Durand-Delacre, D., G. Bettini, S. L. Nash, H. Sterly, G. Gioli, E. Hut, and M. Hulme. 2021. “Climate Migration Is About People, Not Numbers.” Negotiating Climate Change in Crisis 63–81. https://doi.org/10.17863/CAM.76788.

- Durand-Delacre, D., C. Farbotko, Fröhlich, and I. Boas. 2020. “Climate Migration: What the Research Shows Is Very Different from the Alarmist Headlines.” https://theconversation.com/climate-migration-what-the-research-shows-is-very-different-from-the-alarmist-headlines-146905.

- El-Hinnawi, E. 1985. Environmental Refugees. Nairobi. United Nations Environment Programme. https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/121267?v=pdf.

- Farbotko, C. 2005. “Tuvalu and Climate Change: Constructions of Environmental Displacement in the Sydney Morning Herald.” Geografiska Annaler: Series B, Human Geography 87 (4): 279–293. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0435-3684.2005.00199.x.

- Gabrielatos, C., and P. Baker. 2008. “Fleeing, Sneaking, Flooding: A Corpus Analysis of Discursive Constructions of Refugees and Asylum Seekers in the UK Press, 1996-2005.” Journal of English Linguistics 36 (1): 5–38. https://doi.org/10.1177/0075424207311247.

- Gemenne, F. 2010. “What’s in a Name: Social Vulnerabilities and the Refugee Controversy in the Wake of Hurricane Katrina.” Environment, Forced Migration and Social Vulnerability 29:29–40. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-12416-7_3.

- Gemenne, F. 2011. “Why the Numbers don’t Add Up: A Review of Estimates and Predictions of People Displaced by Environmental Changes.” Global Environmental Change 21:S41–S49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2011.09.005.

- Gemenne, F. 2015. “One Good Reason to Speak of ‘Climate refugees’.” Forced Migration Review 49:70–71. https://orbi.uliege.be/bitstream/2268/181286/1/One%20good%20reason%20to%20speak%20of%20‘climate%20refugees’%20-%20FMR%2049.pdf.

- Giuliani, G. 2021. Monsters, Catastrophes and the Anthropocene: A Postcolonial Critique. London: Routledge.

- Hansen, A. 2010. Environment, Media and Communication. London: Routledge.

- Hartmann, B. 2010. “Rethinking Climate Refugees and Climate Conflict: Rhetoric, Reality and the Politics of Policy Discourse.” Journal of International Development 22 (2): 233–246. https://doi.org/10.1002/jid.1676.

- Hendrickx, J., and A. Van Remoortere. 2021. “Assessing News Content Diversity in Flanders: An Empirical Study at DPG Media.” Journalism Studies 22 (16): 2139–2154. https://doi.org/10.1080/1461670X.2021.1987299.

- Hiraide, L. A. 2023. “Climate refugees: A useful concept? Towards an alternative vocabulary of ecological displacement.” Politics 43 (2): 267–282. https://doi.org/10.1177/02633957221077257.

- IOM. 2007. “Discussion Note: Migration and the environment.MC/INF/288.” https://www.iom.int/sites/g/files/tmzbdl486/files/jahia/webdav/shared/shared/mainsite/about_iom/en/council/94/MC_INF_288.pdf.

- IPCC. 2022. “Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability.” In Contribution of Working Group II to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, edited by H.-O. Pörtner, D.C. Roberts, M. Tignor, E.S. Poloczanska, K. Mintenbeck, A. Alegría, M. Craig, S. Langsdorf, S. Löschke, V. Möller, A. Okem and B. Rama, 3056. Cambridge, UK and New York, NY, USA: Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781009325844.

- Jönsson, A. M. 2011. “Framing Environmental Risks in the Baltic Sea: A News Media Analysis.” AMBIO: A Journal of the Human Environment 40 (2): 121–132. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13280-010-0124-2.

- Joris, W., L. d’Haenens, and B. Van Gorp. 2014. “The Euro Crisis in Metaphors and Frames: Focus on the Press in the Low Countries.” European Journal of Communication 29 (5): 608–617. https://doi.org/10.1177/0267323114538852.

- Kolmannskog, V. 2008. Future Floods of Refugees: A Comment on Climate Change, Conflict and Forced Migration. Oslo: Norwegian Refugee Council.

- Loisen, J., and S. Joye. 2016. Communicatie and media. Een inleiding tot communicatiewetenschappelijk onderzoek en theorie. Leuven: Acco.

- McLeman, R., and F. Gemenne. 2018. Routledge Handbook of Environmental Displacement and Migration. London: Routledge.

- McLeman, R., J. Schade, and T. Faist. 2016. Environmental Migration and Social Inequality. New York: Springer International Publishing.

- McLeman, R., and B. Smit 2006. “Migration As an Adaptation to Climate Change.” Climatic Change 76 (1): 31–53.

- McNamara, K. E., and C. Gibson. 2009. “‘We Do Not Want to Leave Our land’: Pacific Ambassadors at the United Nations Resist the Category of ‘Climate refugees’.” Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences 40 (3): 475–483. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2009.03.006.

- Merkley, E., and D. Stecula. 2019. “Framing Climate Change: Economics, Ideology, and Uncertainty in American News Media Content from 1988 to 2014.” Frontiers in Communication 4 (6): 1–15. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcomm.2019.00006.

- Methmann, C. 2014. “Visualizing Climate-Refugees: Race, Vulnerability, and Resilience in Global Liberal Politics.” International Political Sociology 8 (4): 416–435. https://doi.org/10.1111/ips.12071.

- Myers, N. 1997. “Environmental Refugees.” Population and Environment 19 (2): 167–182. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1024623431924.

- Obokata, R., L. Veronis, and R. McLeman. 2014. “Empirical Research on International Environmental Migration: A Systematic Review.” Population and Environment 36 (1): 111–135. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11111-014-0210-7.

- Randall. 2017. “Chapter 15: Engaging the media on climate-linked migration.” In Research Handbook on Climate Change, Migration and the Law, edited by B. Mayer and F. Crepeau. by. Cheltenham: Elgar. https://doi.org/10.4337/9781785366598.00021.

- Roosvall, A., M. Tegelberg, and F. Enghel. 2020. “Media and Climate Migration: Transnational and Local Reporting on Vulnerable Island Communities.” In Media, Journalism and Disaster Communities, pp. 83–98. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Roxburgh, N., D. Guan, K. J. Shin, W. Rand, S. Managi, R. Lovelace, and J. Meng. 2019. “Characterising Climate Change Discourse on Social Media During Extreme Weather Events.” Global Environmental Change 54:50–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2018.11.004.

- Sakellari, M. 2021. “Climate Change and Migration in the UK News Media: How the Story Is Told.” International Communication Gazette 83 (1): 63–80. https://doi.org/10.1177/1748048519883518.

- Sakellari, M. 2022. “Media Coverage of Climate Change Induced Migration: Implications for Meaningful Media Discourse.” Global Media and Communication 18 (1): 67–89. https://doi.org/10.1177/17427665211064974.

- Shehata, A., and D. N. Hopmann. 2012. “Framing Climate Change: A Study of US and Swedish Press Coverage of Global Warming.” Journalism Studies 13 (2): 175–192. https://doi.org/10.1080/1461670X.2011.646396.

- Smets, K., J. Mazzocchetti, L. Gerstmans, and L. Mostmans. 2019. “Beyond Victimhood: Reflecting on Migrant-Victim Representations with Afghan, Iraqi, and Syrian Asylum Seekers and Refugees in Belgium.” Images of Immigrants and Refugees in Western Europe, edited by Leen d’Haenens, Willem Joris and François Heinderyckx, 177–198. Cornell: Cornell University Press.

- Sparks, C. 1988. “The Popular Press and Political Democracy.” Media, Culture and Society 10 (2): 209–223. https://doi.org/10.1177/016344388010002006.

- UNFCCC. 1992. United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change UN. Bonn: Rio De Janeiro.

- Van Praag, L., and S. L. Cheung. 2024. “Navigating tomorrow’s Horizons: Exploring the Interplay of Environmental Factors in Mobility Decision-Making Among Migrants in the Lowlands.” Environmental Sociology 10 (3): 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/23251042.2024.2330772.

- Van Praag, L., and C. Timmerman. 2019. “Environmental Migration and Displacement: A New Theoretical Framework for the Study of Migration Aspirations in Response to Environmental Changes.” Environmental Sociology 5 (4): 352–361. https://doi.org/10.1080/23251042.2019.1613030.

- Walgrave, S., and K. De Swert. 2004. “The Making of the (Issues of The) Vlaams Blok.” Political Communication 21 (4): 479–500. https://doi.org/10.1080/10584600490522743.

- Zetter, R., and J. Morrissey. 2014. “The Environment-Mobility Nexus: Reconceptualizing the Links Between Environmental Stress,(im) Mobility, and Power.” The Oxford Handbook of Refugee and Forced Migration Studies, 342–354. Oxford: Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199652433.001.0001.