ABSTRACT

‘Post-truth politics’, particularly as manifested in ‘fake news’ spread by countermedia, is claimed to be endemic to contemporary populism. I argue that the relationship between knowledge and populism needs a more nuanced analysis. Many have noted that populism valorises ‘common sense’ over expertise. But another populist strategy is counterknowledge, proposing politically charged alternative knowledge authorities in the stead of established ones. I analyse countermedia in Finland, where they have played a part in the rise of right-wing populism, using a combination of computational and interpretive methods. In my data, right-wing populists advocate counterknowledge; they profess belief in truth achievable by inquiry, not by mainstream experts but alternative ones. This is a different knowledge orientation from the valorisation of ‘common sense’, and there is reason to believe it is somewhat specific to contemporary right-wing anti-immigration populism. Populism’s epistemologies are multifaceted but often absolutist, as is populism’s relationship to power and democracy.

Introduction

Dramatic populist upheavals are now familiar in most Western democracies. A peculiar point of interest in these developments internationally has been so-called ‘post-truth’ politics, which allegedly takes an ambivalent relationship to the truth and bases itself on feelings and identity rather than fact (for example, Economist, September 10, Citation2016; Guardian, November 15, Citation2016). ‘Alternative news sites’ or ‘countermedia’ such as Breitbart in the US and Fdesouche in France have contributed to the popularity of politically charged ‘fake news’.

Finland has been no exception; in fact, it is a forerunner. During the 2010s, Finland has seen a right-wing populist uprising in parliamentary politics (Arter, Citation2010), online activism (Pyrhönen, Citation2015), and street gangs such as the Soldiers of Odin. Online activism has played a significant role. The anti-immigration scene was quickly consolidated after the 2008 founding of Hommaforum.org,Footnote1 an online forum for self-proclaimed ‘critics of immigration’. This led many activists to join the right-wing populist Finns Party and contribute to the enormous 2011 success of the party (Ylä-Anttila & Ylä-Anttila, Citation2015). Encouraged by the ‘migrant crisis’ from 2015 on, several ‘countermedia’ websitesFootnote2 sprang up, spreading politically charged news, sometimes of questionable truth value. They have accused immigrants of serious crimes, mainstream journalists of covering them up, and politicians of facilitating a destructive assault on Finnish society by immigrants. They combine facts with fiction and rumours, sometimes intentionally blurring the lines or spreading outright lies, most often cherry-picking, colouring, and framing information to promote a radical anti-immigrant agenda. Despite the mainstream media quickly calling them out as ‘fake news’, these websites became immensely popular, while street violence against immigrants intensified simultaneously and the government asylum policy was tightened.

Thus, in Finland and elsewhere, it is more relevant than ever to study the linkage between populism and the production and communication of knowledge. Populism claims to represent ‘the people’ against a ‘corrupt elite’ (Aslanidis, Citation2016; Berezin, Citation2009; Canovan, Citation1999; Hawkins, Citation2010; Jansen, Citation2011; Kazin, Citation1998; Laclau, Citation2007; Moffitt, Citation2016; Ostiguy, Citation2009; Taggart, Citation2000). However, most studies of this connection have focused on populism’s tendency to valorise experiential folk wisdom and ‘common sense’ while criticising expertise (Cramer, Citation2016, pp. 123–130; Hawkins, Citation2010, p. 7; Hofstadter, Citation1962, Citation1964/2008; Oliver & Rahn, Citation2016; Saurette & Gunster, Citation2011; Wodak, Citation2015b, p. 22).Footnote3 Is populism categorically anti-intellectual, and does it always prefer common-sense knowledge, based on everyday experiences, to expert arguments? This article shows, both theoretically and empirically, that counterknowledge, allegedly supported by alternative inquiry, is another salient strategy of questioning mainstream policies in a populist style, at least in my case of contemporary right-wing populism. An analysis of knowledge claims in Finnish anti-immigrant online publics, by computational and interpretive methods, reveals a multi-faceted view: while often subscribing to fringe populist views, many anti-immigration activists nevertheless claim to hold knowledge, truth, and evidence in high esteem, even professing strictly positivist views, and strongly opposing ambivalent or relativist truth orientations. These communities, consisting mainly not of career politicians but ordinary people using the tools of populism (Ylä-Anttila, Citation2017), often employ ‘scientistic’ language and engage in popularisation of scientific knowledge and rhetoric. They mostly do not oppose expertise on the grounds of ‘folk wisdom’ or experiential knowledge, as we might assume if applying the literature on populism and knowledge to them (Cramer, Citation2016, pp. 123–130; Hawkins, Citation2010, p. 7; Hofstadter, Citation1962, Citation1964/2008; Oliver & Rahn, Citation2016; Saurette & Gunster, Citation2011). Instead, they advocate a particular kind of objectivist counter-expertise. For them, it is the ‘multiculturalist elite’ who are ‘post-truth’.

This article contributes to the study of populism and provides a more nuanced analysis of ‘post-truth politics’. There are reasons to believe that counterknowledge is a primary strategy of contemporary anti-immigration radical right-wing populism. In contrast, the valorisation of experiential ‘common sense’ in favour of expertise is more typical of rural populism, on which the ‘epistemological populism’ literature is largely based (Hofstadter, Citation1962; Kazin, Citation1998). In this sense, this article also contributes to the ongoing discussion on the relationship between populism and the radical right (see Stavrakakis, Katsambekis, Nikisianis, Kioupkiolis, & Siomos, Citation2017), by noting a possible divergence in the epistemological argumentation of these interconnected but distinct political modes.Footnote4

Epistemological populism and counterknowledge

A political epistemology that valorises ‘the knowledge of “the common people”, which they possess by virtue of their proximity to everyday life’, has been termed epistemological populism by Saurette and Gunster (Citation2011, p. 199). Such a tendency to eschew experts in favour of ‘folk wisdom’ is a well-known tool of populism (Cramer, Citation2016, pp. 123–130; Hawkins, Citation2010, p. 7; Hofstadter, Citation1962, Citation1964/2008; Oliver & Rahn, Citation2016; Wodak, Citation2015b, p. 22), while something similar has been identified in recent public debates in Europe over Brexit, and the presidency of Donald Trump in the US. It is now often claimed that ‘the common people’ have had ‘enough of experts telling them what to do’, and that it is the ‘common people’ who have access to practical knowledge via their everyday experiences, from which the experts have become estranged. But this is an overly simplistic view of contesting epistemic authority (Harambam & Aupers, Citation2014) in contemporary populist politics.

While epistemological populism eschews expertise altogether and seeks knowledge in the ‘hearts’ or experiences of the ‘common people’, I propose the concept of counterknowledge to mean contestations of epistemic authority by advocating alternative knowledge authorities. These two concepts, epistemological populism and counterknowledge, can be used for a more nuanced analysis of ‘post-truth politics’. In the case at hand, I ask whether Finnish online anti-immigrant activists and countermedia employ epistemological populism, counterknowledge, or both. How do they use them, what does this tell us about the link between populism and knowledge, and ‘post-truth politics’ more broadly?

Gosa (Citation2011, p. 5) has usefully defined counterknowledge – in a very different scene, black American hip-hop culture – as ‘an alternative knowledge system … challenging white dominated knowledge industries such as the academia or the mainstream press’. In Gosa’s case, artists and hip-hop fans try to explain experienced racial inequality in a political sphere that claims to adhere to racial equality by constructing ‘alternative knowledge’ about elite dominance. It is claimed, for instance, that successful black rappers (such as Jay-Z, Nas, and Kanye West) are puppets of the Illuminati – that a Masonic plot of white supremacists has hijacked hip-hop to manipulate blacks and keep them subjugated, and blacks should ‘wake-up and reclaim hip hop as a tool of black empowerment’ (Gosa, Citation2011, p. 9) and ‘question the information they regularly receive from school and the mainstream media’ (Gosa, Citation2011, p. 12). The creation and dissemination of counterknowledge have political aims. This may seem like a leap from Nordic nationalists, but Gosa notes that very similar epistemological argumentation can be used by right-wing counterknowledge:

In this respect, my case of hip hop conspiracy theory is analogous to the Barack Obama conspiracy theories forwarded by the conservative Tea Party and the ‘Birther Movement.’ Since the 2008 election of Obama as the first black president of the United States, these groups have used Internet media to spread the rumor that Obama is a Kenyan-born Muslim, a socialist, and that he attended terrorist training schools in Indonesia during his childhood … these conspiracy theories are used by some whites to voice racial anxiety and concern over the shifting racial demographics of the country (Gosa, Citation2011, p. 15).

Mosca and della Porta (Citation2009) also note the creation and communication of counterknowledge as one way social movements mobilise, by creating epistemic communities to counter those of the establishment, and construct new identities. Thus, counterknowledge can be defined as alternative knowledge which challenges establishment knowledge, replacing knowledge authorities with new ones, thus providing an opportunity for political mobilisation. What makes both ‘epistemological populism’ and counterknowledge particularly usable for populist mobilisation is the fact that populism typically challenges the elite in terms of political power, while epistemological populism and counterknowledge challenge knowledge elites. These strategies both complement a populist programme.

Knowledge in a social context

Recent research in social psychology highlights the potential impact of such political strategies challenging mainstream knowledge, by showing that (alternative) knowledge authorities can easily overshadow any actual evidence in a social and political context. Firstly, people are uncomfortable with gaps in causal narratives and tend to fill them with almost anything (Lewandowsky, Ecker, Seifert, Schwarz, & Cook, Citation2012; Lewandowsky, Oberauer, & Gignac, Citation2013), emphasising the cognitive importance of narratives. Moreover, we tend to believe knowledge claims that confirm our socially held world-views, rather than assessments of truth value (Bessi et al., Citation2015; Kahan, Citation2010; Kahan, Braman, Cohen, Gastil, & Slovic, Citation2010; Kahan, Jenkins-Smith, & Braman, Citation2011; Lewandowsky, Ecker, et al., Citation2012; Lewandowsky, Oberauer, & Gignac, Citation2013). Even corrections of clearly false information are rarely accepted if they are dissonant with peer group beliefs (Nyhan & Reifler, Citation2010). If the results of a belief lead to political implications that run counter to what you and your peer group believe is ‘right’, those beliefs tend to be rejected even in the face of hard evidence (Lewandowsky, Ecker, et al., Citation2012; Lewandowsky, Oberauer, & Gignac, Citation2013). Moreover, knowledge that is relevant for politics is often social knowledge, which is ‘justified by contextually, historically, and culturally variable (epistemic) criteria of reliability’, which ‘implies that a community may use, presuppose and define knowledge as “true belief” what members of another community or period may deem to be “mere” or “false” belief, ideology, prejudice or superstition’ (van Dijk, Citation2014, p. 21).

Sociology, on the other hand, has long since noted both the cultural bases of cognition (Brekhus, Citation2015) and the proliferation and deterioration of knowledge authorities in modern public spheres, which is a discursive opportunity for counterknowledge production, since most of our knowledge is acquired from others via discourse (van Dijk, Citation2014, p. 68, p. 141). Because we cannot live our lives based on self-researched evidence-based knowledge, we must rely on epistemic authorities (Baurmann, Citation2007; Giddens, Citation1991, p. 22; Levy, Citation2007). Even though ‘the knowledge incorporated in modern forms of expertise is in principle available to everyone’ (Giddens, Citation1991, p. 30), not all have ‘the available resources, time and energy to capture it’ in all cases (Giddens, Citation1991, p. 30). If this is the case, ‘how do you choose which expert to believe?’ (Knight, Citation2000, p. 24). Belief in ‘alternative knowledge’ is not mere irrationality, but something that results from the realities of modernity, particularly ‘ontological insecurity’ (Aupers, Citation2012, p. 22). But to switch from believing traditional knowledge authorities to counterknowledge authorities is merely ‘a transfer of faith’ (Giddens, Citation1991, p. 23). And through the deterioration of established knowledge authorities (Aupers, Citation2012), questioning established knowledge in one field tends to reinforce a tendency to believe counterknowledge in other fields as well:

The more seriously conspiracies are taken, the less trust can be placed in the centres of authority. If conspiracy is everywhere – embedded in the churches, universities, government, banks, the mass media – then no knowledge promulgated by such institutions can be trusted (Barkun, Citation1994, p. 249).

The sociological understanding of alternative knowledge advocated here is in clear distinction from Thompson’s popular definition of counterknowledge as misinformation – knowledge that ‘purports to be knowledge’ but ‘can be shown to be untrue’ (Thompson, Citation2008, p. 2). Most alternative knowledge does not counter knowledge that is in fact (easily) falsifiable, at least by the layperson, nor is counterknowledge necessarily wrong; conspiracies have been known to exist (Bale, Citation2007; Keeley, Citation1999). Taken together, these insights suggest that ‘fact-checking’ has limited utility in public debates. Instead of truth value alone, the social origins, meanings, and implications of knowledge claims are crucial. In this work, I do not seek to confirm or falsify knowledge claims, but to study their political use.

The sociology of conspiracy theory

Conspiracism, or conspiracy theory, is by far the most commonly identified form of counterknowledge in connection with populism. It is a type of counterknowledge particularly suited for populist framing, because it posits that the common people are misled in secrecy by an elite – making conspiracism explicitly political in a populist fashion. The connection was most famously made in 1964 by Hofstadter, who defines the ‘paranoid style’ as ‘a way of seeing the world and of expressing oneself’, in which ‘the feeling of persecution is central, and it is indeed systematised in grandiose theories of conspiracy’, while ‘the spokesman of the paranoid style’ feels ‘righteousness’ and a ‘moral indignation’ (Hofstadter, Citation1964/2008, p. 4). It is a Manichean outlook in that the world consists of good and evil, in perpetual combat – and as such, is very similar to the political outlook of populism (Oliver & Wood, Citation2014).

Understanding conspiracism sociologically, Fenster defines it as ‘the conviction that a secret, omnipotent individual or group covertly controls the political and social order or some part thereof’ (Citation2008, p. 1). It carries a promise of redemption, much like populism (Canovan, Citation1999): ‘anyone with enough fortitude and intelligence can find and properly interpret the evidence that the conspiracy makes available’ (Fenster, Citation2008, p. 8). Conspiracy theories are, indeed, a particular view of democracy: ‘embedded within many conspiracy theories and their understanding of power […] is a longing for a better, more transparent and representative elected government’ (Fenster, Citation2008, p. 12). For Fenster, conspiracy theory is ‘an interpretive framework’ (Citation2008, p. 95) more specifically ‘a complex political and cultural rhetoric and means of seeing the world’ (Citation2008, p. 36). Conspiracism provides ontological security by explaining the unexplained (Nefes, Citation2013), constructs a narrative attempting to ‘restore a sense of agency, causality and responsibility’ (Knight, Citation2000, p. 21), or as Thompson (Citation2008, p. 146) puts it:

it is comforting to believe that a psychic can put you in touch with your loved ones, or that eating broccoli will prevent you getting cancer; it is oddly reassuring to know that apparently random acts of evil are being coordinated by a satanic conspiracy. The practitioners of counterknowledge teach us that the universe is not arbitrary, that things happen for a reason.

Besides conspiracy theory being a ‘populist theory of power’ (Fenster, Citation2008, p. 89), I would add that it is also a populist theory of knowledge. It proceeds from the assumption that ‘the truth is out there’ – that is, secret knowledge exists, withheld by the establishment, but attainable, assuming sufficient dedication. The elite holds not just secret power, but secret knowledge – which should be challenged, claims the conspiracist. In fact, the conspiracist raises herself to the position of an alternative knowledge authority, a true expert instead of ‘false experts leading us astray’. As such, conspiracism is a type of counterknowledge par excellence. To the extent that it longs for truth and liberation, its objectives are laudable, even though its methodology is often defective (also, see Dixon, Citation2012).

Conspiracy theories tend to be supported by those cynical about politics in general (Miller, Saunders, & Farhart, Citation2015; Swami, Chamorro-Premuzic, & Furnham, Citation2010) – particularly minorities and the underprivileged (Stempel, Hargrove, & Stempel, Citation2007). This supports these theories’ role as counterknowledge salient for populist mobilisation: they are not mere rumours believed by irrational people, but alternative explanations which challenge the mainstream, providing political fuel. They often reverse the power-relations between the in-group and the out-group. Sapountzis and Condor (Citation2013) show that Greeks who voice nationalistic sentiments against the Republic of Macedonia used conspiratorial arguments to present Macedonians as benefiting from an unjust secret international power game, claiming that they are in fact the oppressors and the Greeks the oppressed – when the mainstream understanding is the reverse (see also Koronaiou, Lagos, Sakellariou, Kymionis, & Chiotaki-Poulou, Citation2015). A similar dynamic is reflected in fears of Islamisation and ‘feminisation’ in my analysis.

All in all, ‘alternative’ orientations to knowledge seem to be integral strategies in populist politics. However, they may take many forms, not only ‘epistemological populism’, that is, valorisation of experience-based ‘common sense’ (Cramer, Citation2016, pp. 123–130; Hawkins, Citation2010, p. 7; Hofstadter, Citation1962, Citation1964/2008; Oliver & Rahn, Citation2016; Saurette & Gunster, Citation2011). Another, less studied form is counterknowledge, in which alternative knowledge and authorities are proposed – sometimes in the form of conspiracy theory.

Data

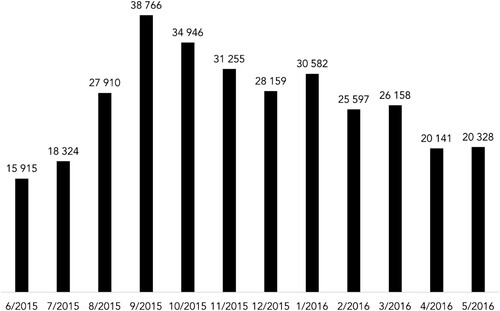

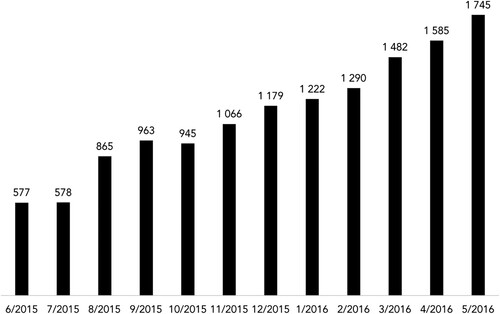

As empirical material, I look at an anti-immigration countermedium founded in 2014 (MV-lehti, ‘WTF Media’), widely considered by the mainstream media as a ‘fake news’ site and the most popular countermedia (YLE, Citation2016), and the most influential anti-immigration online forum (Hommaforum; see note 1), both popular in the Finnish online public sphere (see ). While the WTF dataset contains fewer posts because of the nature of the medium (only administrators can post), since it gets more views per post, the societal relevance of the two datasets is roughly comparable. Nevertheless, Hommaforum is not only larger as a dataset but also much more diverse by nature.

Table 1. Data.

The data collection timespan for both was a full year during the most intense debates over immigration, ignited by the refugee crisis, from June 2015 to May 2016. As can be seen in , the crisis was clearly visible as a peak in Hommaforum posts, whereas WTF has gradually increased its activity, posting three times as often in May 2016 as it did in June 2015 (see ).

Analysis

Topic modelling (Blei, Citation2012; Evans, Citation2014; Meeks & Weingart, Citation2012; Mohr & Bogdanov, Citation2013) is a data-mining method associated with computational social science and the ‘big data’ movement (Bail, Citation2014; Lazer et al., Citation2009). In brief, it recognises repeating patterns of word usage in text. When used by humanities scholars, topic models are used to assess which ‘topics’ (themes) texts are ‘about’. But when word usage patterns are taken to be traces of social activity (Babones, Citation2016), and especially when we know the data contains texts about a particular theme, sociologists may interpret them as frames or other cultural constructs (DiMaggio, Nag, & Blei, Citation2013; Levy & Franklin, Citation2013; Ylä-Anttila, Eranti, & Kukkonen, Citation2017). The potential advantages of topic modelling are the ability to analyse larger datasets than would be practical manually; the exploratory, inductive, ‘grounded’ discovery of unexpected patterns; reproducibility; and the ability to quantify qualitative observations, such as the prevalence of a discussion.

I use MALLET’s (Machine Learning for Language Toolkit, McCallum, Citation2002) implementation of the most common topic modelling algorithm, LDA (Latent Dirichlet Allocation, Blei, Ng, & Jordan, Citation2003), an unsupervised machine learning method, which means that the researcher offers no input as to how the data should be classified.

LDA […] assumes that there are a set of topics in a collection (the number is specified in advance) […] Terms that are prominent within a topic are those that tend to occur in documents together more frequently than one would expect by chance […] each document exhibits those topics with different proportions (DiMaggio et al., Citation2013, pp. 577–578).

In even more simplistic terms, the researcher gives MALLET a dataset of documents and the number of topics she wishes to find, which returns that number of word clusters consisting of words which often occur in the same document. While interpreting conversations based solely on word frequency may seem crude, the word clusters are surprisingly meaningful, as I will show. In this paper, I consider them to represent frames: particular ways, practices and habits of interpreting issues (Entman, Citation1993; Nisbet, Citation2009; Ylä-Anttila et al., Citation2017). Frames identify relevant themes and present interpretations of them, and as such, the same themes are often discussed in my data using different frames. There is clearly much thematic overlap in the frames labelled understanding, truth and beliefs below, but their framing differs.

Both datasets were included in the same model to look for frames that may or may not be used in both (WTF and Hommaforum). I use a 200-topic model. Nearly all the 200-word clusters were distinct, recognisable frames in the data, which indicates good model fit – but most were about themes not directly relevant to the study at hand (for example, economic policy, football, motorcycles). After a qualitative examination based on the literature discussed above, I discarded 186 frames, and selected and named 14 (see ). Details on the modelling, selection, and interpretation of data can be found in the methodological appendix. Next, I qualitatively analyse the selected Hommaforum threads (11 threads, 1442 messages out of 318,081 total) and WTF posts (81 posts out of 13,497 total). In this research design, the topic model is used to select material for qualitative interpretation in a way that is more reproducible and less subjective than qualitative selection would be. The sample quotes were selected to be as representative as possible of the described frame, but only cover a fraction of the material used for the analysis. Of course, my analysis does not cover all arguments in these fora, particularly in the case of Hommaforum, which is a diverse community of people rather than a medium with a single voice. Still, it should present a general picture of the most commonly used knowledge arguments.

Table 2. Selected frames in three named themes, their names as interpreted by the author, their top words translated from Finnish to English by the author, and their frequencies.

Epistemological populism

The model did not find frames the researcher could identify from the outset as dealing with experiential knowledge or ‘common sense’. This is a first sign that they may not be very prevalent in the data. However, it did find four frames dealing with knowledge more broadly; the valorisation of ‘folk wisdom’ suggested by the ‘epistemological populism’ literature plays a significant role in the discussions, it should be found here. First, identified by words such as ‘truth’, ‘opinion’, and ‘fact’, the obviously epistemological frame of truth (#73, see ) is salient both on WTF and Hommaforum. On WTF, the mainstream media are branded liars, as WTF identifies as a ‘truth medium’ (4 November 2015) instead of ‘fake news’ (as the mainstream media claims) because it has no journalistic limitations on what can be published, thus avoiding bias. To uphold truth, it is claimed, freedom of speech must be absolute:

There is no partial censorship, it either exists or doesn’t … Freedom of speech is democracy’s most important foundation, without it democracy doesn’t exist … They don’t want to silence WTF Media because it’s lying, they want to silence us because we tell the truth they don’t want to hear (WTF Media, 4 May 2016).Footnote5

At the outset, it is evident that the framing of truth, here, looks similar to the populist framing of power and democracy: all limitations by liberal-democratic institutions and mainstream media – checks and balances that are in place to protect minorities – should be lifted to uphold true freedom and democracy. More specifically, the absolutism on truth, particularly on Hommaforum, takes the form of an explicit empiricist–positivist philosophy of science and an ‘engineer mentality’, in that truths about society are assumed to be accessible by scientific methods. These truths could be adopted for governance, but the multiculturalist–relativist hegemony and the corrupt research community prevent such work. This is exemplified in several quotes below. A rationalist attitude could cut through the ‘lies’ of multiculturalists, who are accused of basing their arguments on feelings and moral relativism instead of empirical data.

When statistics are published that the ‘musulmaniacs’ rape 17 times more than native Finns, they argue you shouldn’t publish statistics because someone might be offended (Hommaforum user, 30 December 2015).

Rational, evidence-based thought is our weapon against opinions based on feelings (WTF Media, 22 April 2016).

Perhaps not incidentally, several nicknames on Hommaforum, as well as self-reported professions, hint at a high percentage of engineers and other technical professionals, and more than 80% of users are male (Hommaforum Statistics, Citation2016). Gambetta and Hertog (Citation2016) have recently noticed that engineers are disproportionally represented among not only right-wing extremists but Islamist terrorists, and explain this with a mindset that seeks order and hierarchy, often found among engineers.Footnote6 Perhaps not incidentally, such personality traits are more common in men than women (Gambetta & Hertog, Citation2016, pp. 141–146). In my data, blame for ‘distorted’, ‘subjective’ and ‘biased’ views on truth is typically imputed to post-positivist social science, which is linked with the false belief – it is argued – that reality can be studied through texts. ‘Real’ knowledge could be found by ‘real’ science, which many contributors claim to represent and/or advocate, not common sense and certainly not the humanities. Interestingly, in this respect, the activists studied here diverge strongly from the conspiracy theorists studied by Harambam and Aupers (Citation2014), who were fiercely critical of science precisely because of its claimed material reductionism. In fact, many Hommaforum writers engage in specifically the kind of ‘boundary work’ that Harambam and Aupers identified and that their informants criticised, protecting the perceived ‘purity’ of science from non-scientific (non-measurable) claims.

Apparently, the reporter believes there is no reality outside texts and words; that words, like spells, change reality to what he wants (Hommaforum user, 8 February 2016).

Frame #110, labelled ‘understanding’ and marked by the words ‘to understand’, ‘cause’, ‘thought’, and ‘reality’, discusses understanding of reality in terms of social construction and cognitive bias. These were claimed to make anti-racists unable to see the negative effects of immigration. Many take the position that leftists and cultural liberals are blinded by their cultural relativism, which makes them unable to understand ‘the objective truth’. The frame connects understanding with mass media, their reliability, and freedom of speech: if the media are biased and freedom of speech limited, how can an accurate view of reality be formed? Hommaforum contributors and WTF Media accuse multiculturalists of a dishonest and flawed understanding of reality.

Attitudes towards refugees are an excellent example of how cognitive bias affects people. The tendency to skate over all negative consequences is a bias, in which one thinks one’s own impression is based in reason (Hommaforum user, 19 November 2015).

This claim of a biased understanding of reality is strictly limited to the political opposition, who are allegedly blinded by their ideology – inhabiting a false consciousness (van Dijk, Citation2014, p. 141). Harambam and Aupers (Citation2017) have studied conspiracy theorists, who deflected accusations of conspiratorial thinking by claiming that others are the real conspiracy theorists, and only see evidence of conspiracies everywhere they look, whereas they themselves are in fact capable critical thinkers. Here, similarly, discussants are overly confident in their own rationality and conversely dismissive of the rationality of the political opposition. The argument is based on social psychological studies of cognitive bias, but not extended to cover the possible cognitive bias of the immigration critics themselves. In such messages, the contributors are building and strengthening their own epistemic community, one which has particular criteria of validity for knowledge, which are considered superior to others (van Dijk, Citation2014, pp. 21, 144, 147–152).

The repression of [the multiculturalists’] own ideological rotten evilness is often caused by cognitive dissonance so deep they can’t fight it any other way than to stigmatise others as ‘evil’ and dismiss their opinions (WTF Media, 16 February 2016).

The frame of beliefs (#151) is surprisingly focused on gender, even though this was not apparent from the top words. Women (and particularly gender studies) are blamed for non-positivist and non-rational world-views resulting in detrimental policy (immigration). Many Hommaforum messages claim that women are irrational in their beliefs and make detrimental immigration and multiculturalism possible by relying on feelings and ‘common sense’ instead of reason. Hommaforum users particularly brand feminism, gender and ethnicity studies as incoherent madness because of their claimed lack of empiricist–rationalist logic.

In 2016 we are seeing in all its brutality what happens when the woman gives up her natural role as homemaker and mother, and starts channeling her caring instincts and weak prognostic abilities towards primitive Arab men (Hommaforum user, 8 March 2016).

Many posts in frame #163 (research) represent a kind of citizen science, where writers frame politics through research and research through politics, while at the same time denouncing academic research that has political aims. Contributors argue that proper research could provide arguments in favour of their own political views, such as showing that Muslims and Somalis are prone to commit rape and avoid paid work, but immigration researchers are corrupt and misled by their ideology.

Fem … I mean gender studies’ favourite argument is that outsiders cannot have the expertise to comment on the quality of their research. Only those patting the backs of gender studies scholars do. There are scientific disciplines in which that actually applies (as well as specialities of engineering; I don’t think there are more than a hundred people in the world who understand the specialty I myself work in), but many ‘humanities’ have, after being politicised, become totally indefensible (Hommaforum user, 18 February 2016).

[In a discussion about a social-psychological study on how immigrant identities are ‘negotiated’ within societal structures] Is a Somali rapist somehow ‘negotiating’ with society? … That’s just abstract poetry, how can you get a PhD in that (Hommaforum user, 19 February 2016).

Predictably, in frame #186, academia is framed as a corrupt insiders’ club and academics portrayed as a group of good-for-nothing layabouts (see also Cramer, Citation2016).

The claims of ideologically and politically biased researchers are wrong and have been proven as such, which discredits their distorted and deceitful studies (Hommaforum user, 17 February 2016).

Universities produce such ‘top-class experts’ as sociologists of celebration (this guy was presented as an expert on TV), researchers on light pollution (one of whom I personally know), scholars of the migration of ants and others you’d expect to find only in comic books (Hommaforum user, 4 February 2016).

While the quotation above echoes a general distrust of academic expertise, I did not find examples of valorisation of common sense or personal experience in either Hommaforum or WTF Media. While this does not mean they do not exist at all, what can be said is that they are not very common. On the contrary, WTF articles and Hommaforum posts voiced heavy reliance on evidence in knowledge claims, but often not the same evidence as used in the mainstream media, or at least not the same interpretations of it.

Counterknowledge

I will now move on to discussions that were tentatively identified as likely locations for counterknowledge production. The climate change frame (#7) consists largely (but by no means solely) of denialism and takes place mostly on Hommaforum, on which there is a 120-page debate on this subject. Both denialists and ‘alarmists’ reference a myriad of facts and measurements to support their arguments, and the discussion is largely technical in nature. In contrast, the WTF posts on climate change are unanimously denialist and reflect a more overtly political stance, even moral condemnation of climate change mitigation, rather than the more technical framing on Hommaforum.

Surface stations ‘observe’ more warming than in the troposphere, several times more in fact. According to radio sensors, for almost 60 years the troposphere didn’t warm at all even though CO2 levels increased. Thus, the anthropogenic global warming theory remains a theory (Hommaforum user, 31 May 2016).

The climate hoax is a crime against humanity (WTF Media, 1 November 2015).

The medicine frame (#108) mostly comprises WTF posts on alternative medicine, such as the supposedly cancer-curing effects of baking soda and how ‘Big Pharma’ attempts to suppress this information. Interestingly, many Hommaforum contributors have strong views on alternative medicine and condemn it as ‘quackery’ and ‘pseudoscience’ – consistent with the dominant empiricist–positivist epistemological stance on the forum. WTF’s infatuation with alternative medicine is also used by Hommaforum users as evidence of the site’s unreliability.

Even the most aggressive cancerous tumours have been eradicated with the help of baking soda (WTF Media, 30 July 2015).

We’re not talking about a serious news site here. Cancer is a kind of fungus cured by baking soda, yeah right (Hommaforum, 8 November 2015).

A distinct frame (#133) encompasses quantification: framing various policy areas in terms of numbers and statistics. Most often this relates to immigrant crime, especially rape statistics, and the over-representation of immigrants in them. The mainstream media and authorities are accused of covering up this issue, and WTF and other countermedia praised for reporting them truthfully. It is true that the mainstream media utilises safeguards against stigmatising minorities, for example, not mentioning the immigrant status of criminals unless it is deemed pertinent to the case. Justified or not, these are portrayed as ‘sugar-coating’ and/or ‘cover-ups’ by the radical populist right, who claim such practices distort the public’s view of immigrant criminality. Indeed, the dominant epistemology on Hommaforum claims that statistics can be taken as accurate descriptors of reality ‘as is’. This highlights how counterknowledge is not necessarily ‘lies’ or ‘fake’, but an alternative framing of known facts, claimed to be the only true one. The usage of quantitative measurements on Hommaforum is not often used to hide overtly racist expressions, as is sometimes the case in politics, when extreme positions are framed in technical language to make them more acceptable. Instead, overtly racist positions are seemingly justified by statistics:

In 2014 there were 713 suspected rapes in Finland, and since they estimate in the US that 65% of sexual assaults are not reported, the total number would be 1177 using the same percentage. There are more niggers in the US than we have thus far, so that percentage can be considered indicative at best (Hommaforum user, 30 June 2015).

In a similar vein, frame #162 concerns whether Africans have lower intelligence scores than Northern Europeans and Americans, whether this is the cause of African poverty and migration, and whether this should affect immigration policy. Engaging in citizen science to produce counterknowledge, these contributors spend considerable time in lengthy debates over this issue, citing studies left and right. Hommaforum is far from unanimous on this: many are highly critical of claims that Europeans have higher IQ’s or that IQ matters. However, those who believe that IQ is relevant claim it is an objective basis for racism – another example of a technical-rational frame.

Intelligence testing is a fully neutral and objective yardstick for filtering those who attempt to enter the country. We can’t read their thoughts, but we can measure their brain capacity. And it only takes ten minutes (Hommaforum user, 9 January 2016).

One contributor, particularly critical of the general tone of the thread, is quoted below at length because of his/her remarkably accurate take on so-called ‘discussion board science’, making the issue of overblown scientism apparent:

The book IQ and the Wealth of Nations is a typical inspiration for ‘discussion board science’. It has been claimed again that pro-immigration people have been scientifically proven wrong and the integrity of their research is compromised by their ‘unscientific liberalism’ … Where has this ‘proof’ been found? That’s right, on discussion boards … The hallmarks of ‘discussion board science’ include a general scientism: a compulsion for ‘scientific proof’ and the emphasis on how ‘science’ has ‘proven’ this and that, even though such an attitude is wholly alien to actual scientific research. Misunderstandings on the possibilities and limits of science, reducing complex moral issues to ‘scientific’ yes/no experiments … and a refusal to believe how difficult and often futile it is to apply scientific findings to societal questions (Hommaforum user, 18 February 2016).

Frame #166 lets us see how Hommaforum talks about WTF Media.Footnote7 The reception is mixed, with some condemning WTF’s ‘obvious’ neo-Nazism and apparent political connections with Russia, using these connections to frame it as unreliable. Many praise WTF for ‘saying what others won’t’; even though much of the information might be bogus, some of it is correct and not available elsewhere. The participants emphasise that the same scepticism should be felt against mainstream media and countermedia, and that smart media consumers can assess information themselves, without gatekeepers, like a rational homo economicus on a marketplace of ideas. The ideal rational individual (who, at least implicitly, is male) can make decisions himself and does not need the ‘nannying’ of media gatekeepers and watchdogs (who are often portrayed as women, see Hellman & Katainen, Citation2015). Posts exhibit an absolutist view on freedom of speech: even if they condemn WTF’s overtly anti-Semitic and conspiracist content, they are prepared to fight for its right to publish it. This is reminiscent of the populist framing of power: full and absolute liberty would result from ‘true’ rule of the people, which could be realised if only the corrupt authorities be removed.

Conspiracy

When discussing power and its locations (#11), both Hommaforum users and WTF posts often use a conspiracist logic; however, some Homma users are also critical of conspiracism. The elite, which is claimed to hold true power in society behind the scenes, comprises of – among others – socialists, who have since the fall of the Soviet Union teamed up with capitalists, and formed ‘the Euroviet Union’ (Eurostoliitto, a term possibly coined by Timo Soini, the long-term chairman of the right-wing populist Finns Party, see Soini, 26 April Citation2010; WTF Media, 10 April 2016). They ‘control the mass media’ (WTF Media, 22 February 2015), thus controlling society through the production of ‘consensus reality’ (WTF Media, 31 May 2016). They have enabled supposedly destructive mass immigration through their ‘elite plan’ (Hommaforum user, 29 March 2016).

A hierarchic organisation can achieve great power and spread the agenda of a small top elite efficiently … it is imperative that this organisation is secret since the common people cannot know who pulls the strings … the primary channel of furthering this agenda is organisations such as the Bilderberg group, the Trilateral commission and CFR (Council of Foreign Relations). Another channel is local freemason lodges (WTF Media, 4 January 2016).

A gender framing also figures prominently in connection with the power frame, as the ‘softness’ and permissiveness of society, manifested in multiculturalism and immigration, is claimed to result from a ‘feminisation’ of society advanced by the inclusion of women in politics. Women in some posts are said to be those holding power as ‘feminism has gone too far’:

Politics, the judicial system, the bureaucracy, the media, the hostility and belittlement of our own men by our women. This is all because of feminism gone too far. Muslim mass immigration is only the symptom, feminism is the disease (Hommaforum user, 1 June 2016).

More often, however, women are portrayed as ‘useful idiots’ who make the social liberal agenda possible because of their essential biologically determined caring and compassion; they are being duped by the elite because they cannot participate rationally in politics:

In the multiculturalist siege, women are mostly so-called useful idiots rather than the ones to blame because multiculturalism is mostly advanced by cynical old men with their own selfish interests and for that the softness of women is an apt tool. Women buy the media sob stories about dead kids in the Mediterranean (Hommaforum user, 4 May 2016).

The WTF posts in frame #37 on Jews represent classic anti-Semitic conspiracy theory – Jews are in control of much of society, the Holocaust did not happen, and so on:

Jews have throughout history been connected to organised crime – usury, human trafficking, narcotics and corruption (WTF Media, 25 November 2015).

However, Hommaforum posts mentioning Jews are much more varied: only some posit anti-Semitic attitudes, whereas many frame their views with sympathy for the historical plight of the Jewish people and are especially supportive of modern-day Israel. Some Hommaforum users also were quick to condemn any theories about Jewish global dominance as conspiracist and thus unreliable, as in the following example:

Here’s a new interesting documentary worth watching on Jews [Posts link to anti-semitic documentary film on Youtube] (Hommaforum user, 18 June 2015).

The merits of the maker of that ‘documentary’ include conspiracy movies on chemtrails and fluoride. I bet that’s real high-quality investigative journalism (Hommaforum user in reply to previous, 19 June 2015).

‘Media’, ‘journalist’, ‘story’, and the names of several Finnish mainstream media outlets mark frame #128. The media is largely discussed from a conspiracist perspective on both Hommaforum and WTF Media: it is claimed to be on the leftists’ side, publishing lies about nationalists and censoring the truth about immigrants under the false ideology of ‘political correctness’:

‘Mainstream media’ has for good reason become an unsavoury concept in the eyes of the citizens. It works in the interest of the political and economic elite by systematically lying to the public about political projects dear to its heart, such as forced multiculturalism and the European Union (WTF Media, 5 March 2016).

Finally, frame #183 is about the Eurabia thesis: the conspiracy theory that European elites are secretly plotting to Islamise Europe through mass immigration, by weakening European culture and the European gene pool. According to the posts and articles here, the EU was founded by a conspiracy-leading freemason Austrian Jew who wanted to destroy European peoples by mixing Asian and ‘Negroid’ blood into the European bloodline. For at least a century now, a secret society of Marxists, anarchists, Jews and Freemasons (who some claim are led by George Soros) have been advancing their plot to destabilise and ultimately destroy European societies to create a New World Order, and multiculturalism is just a tool in this project. Again, a gender frame is surprisingly apparent: women are being used by the elites, because they are easily controllable and led by their emotions. A narrative emerges from these posts, both on WTF and Hommaforum, of a secret cabal trying to create a new pan-European race that would be more easily controlled than ‘pure’ Europeans. This is also why immigrants ‘do not get deported or even convicted of rape’ according to WTF Media (21 March 2016). African and Middle Eastern immigrants raping European women is allegedly part of the plan to make the European gene pool more easily controllable by introducing less intelligent genetics. This is an all-encompassing conspiracy theory par excellence:

The New World Order championed by the American billionaire David Rockefeller and the Bilderberg Group, the combination of capitalism and authoritarianism, is coming […] The Muslim conquest of Europe is a prologue for the destruction of Europeans (WTF Media 21 March 2016).

Discussion

I have studied the framing of knowledge, counterknowledge, and conspiracism in a large set of anti-immigration online discussions and ‘alternative news’ in the Finnish public sphere – one which has seen an unprecedented right-wing populist uprising in the 2010s.

The discussions on conspiracy reveal the ‘usual suspects’: Jews, Freemasons, Communists, the Bilderberg Society, bankers, multiculturalists, the media, the political left, and other elites, in various combinations depending on the writer, plotting in secret to take over the world while taking advantage of ‘useful idiots’ such as women in the process. While some of these claims are outlandish, it is not very useful to dismiss conspiracist framing as madness, considering its widespread popularity in contemporary society. Instead, it should be understood as an absolutist orientation to power and democracy, one which divides the world into good and evil – just like populism – and an absolutist epistemological frame; one which claims most people are ignorant, and true knowledge hides behind the smoke and mirrors. Such interpretations of power currently carry immense weight politically. However, eagerness for ‘proof’ of the conspiracy’s existence leads to glossing over any conflicting information, and an assumption that every clue is connected to the greater conspiracy, an attitude tuned to find proof of nefarious agency.

The clear-cut difference between right and wrong, those who are ‘in the know’ vs. the ‘sheeple’ (Harambam & Aupers, Citation2014, p. 474) helps to explain why the discussions analysed here so often espoused an empiricist–positivist philosophy: conspiracy theory is an absolutist frame of knowledge just as populism is of power. Rather than embracing an ambivalent or relativist stance towards truth, as suggested by the ‘post-truth’ thesis, or a stance based on first-hand life experiences as more valuable than expertise (Saurette & Gunster, Citation2011), the right-wing populists studied here instead generally endorse radical scientism. Their strong beliefs about using (statistical) science to arrive at truths about society, and to use these truths to manage societies ‘objectively’ and ‘rationally’, is their way of building an opposition between themselves – supposedly not only morally but epistemically right – and the ‘misguided’ elite, in a populist fashion. This is crystallised in a final example from the data discussing Jussi Halla-aho, a right-wing populist blogger and leading anti-immigration politician: ‘He uses only unambiguous facts and draws conclusions directly from them. […] Doing so always results in a text that is indisputable’ (Hommaforum user, 25 March 2016). In this thinking, multiculturalists do not just have the wrong opinions, they are delusional about reality.

Furthermore, discussants connect this rationality, the ability to arrive at truths via empirical observations and logical reasoning, with the male gender. The realm of conspiracy theory is male-dominated (Ward & Voas, Citation2011) and conspiracists self-identify as critical thinkers (Harambam & Aupers, Citation2017). Indeed, conceptions of gendered rationality seem to play a large role in communities which centre around claims of critically engaging widely accepted truths. This is most acutely visible in the recent politicisation of the ‘manosphere’ (Lilly, Citation2016), a movement of online anti-feminism, which often self-identifies around a conspiracist metaphor of ‘the red pill’ (which the protagonist of the sci-fi film The Matrix has to take in order to ‘wake up’ to the real world rather than living in false consciousness). In fact, the overlap between the ‘manosphere’ and the male-dominated anti-immigration ‘alt-right’ is likely significant and merits further study.

To reiterate, whereas populists have often been identified as critical of intellectuals and technocrats (Cramer, Citation2016, pp. 123–130; Hawkins, Citation2010, p. 7; Hofstadter, Citation1962, Citation1964/2008; Oliver & Rahn, Citation2016; Saurette & Gunster, Citation2011; Wodak, Citation2015b, p. 22), the right-wing populists studied here rather advocate a type of counterknowledge – a kind of ‘objectivist’ technocracy based on alternative knowledge authorities. This understanding should help us make more nuanced analyses of so-called post-truth politics and populist epistemologies: alternative knowledge strategies can indeed function as populist tools, not only as simple anti-intellectualism but a multitude of critical strategies including a defence of positivism and empiricism. In its absolutism, this kind of counterknowledge fits well with the populist Manichean frame of politics: opponents are deemed to be wrong not only in terms of morals, or knowledge, but in their view of what constitutes knowledge in the first place, that is, their epistemological premises about the world. What counterknowledge does not fit so well with is populism’s focus on ‘the common people’, from which populism's often-identified anti-intellectualism stems.

Indeed, future research on knowledge and populism should assess whether various populist movements tend to use different knowledge constructions. It seems plausible that the strong emphasis on counter-expertise found in this article is a feature of the particular media studied: an anti-immigration discussion board and a countermedia news site, which strategically focus on opposing dominant discourses on multiculturalism, and are produced by activists with aptitude and skill in information technology and communications. Such an activist profile is fairly typical of contemporary radical right-wing populist movements, which often employ online communications in their strategies. On the other hand, the roots of populism are in anti-modernisation rural movements (see Kazin, Citation1998), for which it is quite plausible to assume that valorisation of ‘folk wisdom’ is more typical (Cramer, Citation2016, pp. 123–130; Hawkins, Citation2010, p. 7; Hofstadter, Citation1962, Citation1964/2008), and of which there are still strong echoes in contemporary populist movements including Trumpism and the Finns Party (Oliver & Rahn, Citation2016; Ylä-Anttila, Citation2017). Many contemporary right-wing populist movements are amalgams of populism and nativism. Their views and strategies regarding knowledge are affected by their specific combination of these repertoires. As such, studying populist knowledge-production provides a promising avenue to further understanding populism in general. Populists are not just ‘post-truth’; different populisms seem to have different truth orientations. The particular correlations between types of populism and types of truth orientations are a matter for future empirical work.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. ‘Homma’ (lit. ‘thing’ or ‘job’) comes from the somewhat obscure idiom ‘homma nousuun’, literally translated as ‘[let’s put this] thing onto an upward path/trajectory’, meaning roughly ‘a toast to the advancement of our cause’. This is an ironic reference to historical Finnish neo-Nazi leader Väinö Kuisma using this expression in the documentary film Sieg Heil Suomi (1994), in which Finnish neo-Nazis are presented in a rather unflattering light; as such the name of the forum is likely a piece of self-deprecating humour rather than a positive self-identification with Nazism.

2. The most popular of these is MV-lehti (‘WTF Media’), a right-wing populist countermedium founded by Ilja Janitskin, who is a suspect in multiple crimes and in police custody at the time of writing (October 2017). Others include Magneettimedia (‘Magnet Media’), a neo-Nazi news site originally started by businessman Juha Kärkkäinen; and a myriad of anti-immigration blogs. These often share content with each other.

3. My view of populism is to understand it as a cultural repertoire, a set of political tools (Lamont & Thévenot, Citation2000; Swidler, Citation1986) which pit a valorised ‘people’ against a corrupt ‘elite’, rather than as an overarching and coherent value-system such as an ideology (Aslanidis, Citation2016; Brubaker, Citation2017; Jansen, Citation2011; Moffitt, Citation2016; Ylä-Anttila, Citation2017). As for argumentation, I understand it through the pragmatist sociological perspective of Boltanski and Thévenot’s (Citation1999, Citation2006) justification theory as a communicative activity based on moral habitual practices which are not only discursive, but embodied and material. Despite the many differences, there is a significant compatibility between Boltanski and Thévenot and argumentation theory, particularly the concept of endoxa (van Eemeren, Citation2010, p. 111) and Wodak’s (Citation2015a) framework of topoi, but this discussion will have to take place elsewhere.

4. Material quoted in this article includes strong racist and sexist language.

5. All translations from Finnish by the author. WTF often re-publishes other sites’ posts verbatim, and does not always make this clear. I assume content nevertheless reflects WTF Media’s positions, and apologise if I have misattributed quotations.

6. See also van der Waal and de Koster (Citation2016) in this journal, who claim that education tends to decrease conservatism because of dereification.

7. In turn, WTF does not hold a very favourable view of Hommaforum. On 30 April 2015, they posted that Homma has been ‘killed’ by their ‘hypocrisy’ and ‘liberalism’ after Homma moderators had censored some of WTF writers’ messages, thus not adhering to full and absolute freedom of speech. On 6 April 2016, WTF labeled Hommaforum founder Matias Turkkila ‘a mole’ and an enemy of the anti-immigration movement because of his recent marriage with Finnish Broadcasting Company journalist Sanna Ukkola, who had earlier been critical of the movement.

References

- Arter, D. (2010). The breakthrough of another West European populist radical right party? The case of the true Finns. Government and Opposition, 45(4), 484–504. doi: 10.1111/j.1477-7053.2010.01321.x

- Aslanidis, P. (2016). Is populism an ideology? A refutation and a new perspective. Political Studies, 64(1), 88–104. doi: 10.1111/1467-9248.12224

- Aupers, S. (2012). ‘Trust no one’: Modernization, paranoia and conspiracy culture. European Journal of Communication, 27(1), 22–34. doi: 10.1177/0267323111433566

- Babones, S. (2016). Interpretive quantitative methods for the social sciences. Sociology, 50(3), 453–469. doi: 10.1177/0038038515583637

- Bail, C. A. (2014). The cultural environment: Measuring culture with big data. Theory and Society, 43(3), 465–482. doi: 10.1007/s11186-014-9216-5

- Bale, J. M. (2007). Political paranoia v. political realism: On distinguishing between bogus conspiracy theories and genuine conspiratorial politics. Patterns of Prejudice, 41(1), 45–60. doi: 10.1080/00313220601118751

- Barkun, M. (1994). Religion and the racist right: The origins of the Christian identity movement. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press.

- Baurmann, M. (2007). Rational fundamentalism? An explanatory model of fundamentalist beliefs. Episteme; Rivista Critica Di Storia Delle Scienze Mediche E Biologiche, 4(2), 150–166.

- Beautiful Soup. (2017). Retrieved from https://www.crummy.com/software/BeautifulSoup/

- Berezin, M. (2009). Illiberal politics in neoliberal times: Culture, security and populism in the New Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Bessi, A., Coletto, M., Davidescu, G. A., Scala, A., Caldarelli, G., & Quattrociocchi, W. (2015). Science vs conspiracy: Collective narratives in the Age of misinformation. PLoS ONE, 10(2). doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0118093

- Blei, D. M. (2012). Topic modeling and digital humanities. Journal of Digital Humanities, 2(1), 8–11.

- Blei, D. M., Ng, A. Y., & Jordan, M. I. (2003). Latent Dirichlet allocation. Journal of Machine Learning Research, 3, 993–1022.

- Boltanski, L., & Thévenot, L. (1999). The sociology of critical capacity. European Journal of Social Theory, 2(3), 359–377. doi: 10.1177/136843199002003010

- Boltanski, L., & Thévenot, L. (2006). On justification: Economies of worth. Translated by Catherine Porter, originally published in French as De la justification : les économies de la grandeur, 1991. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Brekhus, W. H. (2015). Culture and cognition: Patterns in the social construction of reality. Cambridge: Polity.

- Brubaker, R. (2017). Why populism? Theory & Society, 46(5), 357–385. doi: 10.1007/s11186-017-9301-7

- Canovan, M. (1999). Trust the people! Populism and the two faces of democracy. Political Studies, 47(1), 2–16. doi: 10.1111/1467-9248.00184

- Chang, J., Boyd-Graber, J., Gerrish, S., Chong, W., & Blei, D. M. (2009). Reading tea leaves: How humans interpret topic models. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 22, 288–296.

- Cramer, K. J. (2016). The politics of resentment: Rural consciousness and the rise of Scott Walker. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

- DiMaggio, P., Nag, M., & Blei, D. M. (2013). Exploiting affinities between topic modeling and the sociological perspective on culture: Application to newspaper coverage of U.S. Government Arts Funding. Poetics, 41(6), 570–606.

- Dixon, D. (2012). Analysis tool or research methodology: Is there an epistemology for patterns? In D. M. Berry (Ed.), Understanding digital humanities (pp. 191–209). Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- The Economist. (2016, September 10). Yes, I’d lie to you. The post-truth world. Retrieved from http://www.economist.com/news/briefing/21706498-dishonesty-politics-nothing-new-manner-which-some-politicians-now-lie-and

- Entman, R. M. (1993). Framing: Toward clarification of a fractured paradigm. Journal of Communication, 43(4), 51–58. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-2466.1993.tb01304.x

- Evans, M. S. (2014). A computational approach to qualitative analysis in large textual datasets. PLoS ONE, 9(2), 1–10. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0087908

- Fenster, M. (2008). Conspiracy theories: Secrecy and power in American culture. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Gambetta, D., & Hertog, S. (2016). Engineers of Jihad: The curious connection between violent extremism and education. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Giddens, A. (1991). Modernity and self-identity: Self and society in the late modern Age. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Goffman, E. (1984). Frame analysis. New York: Harper & Row.

- Gosa, T. L. (2011). Counterknowledge, racial paranoia, and the cultic milieu: Decoding hip hop conspiracy theory. Poetics, 39(3), 187–204. doi: 10.1016/j.poetic.2011.03.003

- The Guardian. (2016, November 15). ‘Post-truth’ named word of the year by Oxford Dictionaries. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/books/2016/nov/15/post-truth-named-word-of-the-year-by-oxford-dictionaries

- Harambam, J., & Aupers, S. (2014). Contesting epistemic authority: Conspiracy theories on the boundaries of science. Public Understanding of Science, 24(4), 466–480. doi: 10.1177/0963662514559891

- Harambam, J., & Aupers, S. (2017). ‘I Am Not a conspiracy theorist’: Relational identifications in the Dutch conspiracy milieu. Cultural Sociology, 11(1), 113–129. doi: 10.1177/1749975516661959

- Hawkins, K. (2010). Venezuela’s chavismo and populism in comparative perspective. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Hellman, M., & Katainen, A. (2015). The autonomous Finnish man against the nanny state in the age of online outrage: The state and the citizen in the ‘Whiskygate’ alcohol policy debate. Sosiologia, 52(4), 334–349.

- Hofstadter, R. (1962). Anti-intellectualism in American life. New York: Vintage Books.

- Hofstadter, R. (1964/2008). The paranoid style in American politics. 1st Vint. New York: Vintage Books.

- Hommaforum Statistics. (2016). Retrieved from http://hommaforum.org/index.php?action=stats

- Jansen, R. S. (2011). Populist mobilization: A new theoretical approach to populism. Sociological Theory, 29(2), 75–96. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9558.2011.01388.x

- Kahan, D. M. (2010). Fixing the communications failure. Nature, 463(7279), 296–297. doi: 10.1038/463296a

- Kahan, D. M., Braman, D., Cohen, G. L., Gastil, J., & Slovic, P. (2010). Who fears the HPV vaccine, who doesn’t, and why? An experimental study of the mechanisms of cultural cognition. Law and Human Behavior, 34(6), 501–516. doi: 10.1007/s10979-009-9201-0

- Kahan, D. M., Jenkins-Smith, H., & Braman, D. (2011). Cultural cognition of scientific consensus. Journal of Risk Research, 14(2), 147–174. doi: 10.1080/13669877.2010.511246

- Kaleva. (2015, March 28). Vihasivusto tienaa isoja tuloja tunnettujen suomalaisyritysten mainoksilla. Retrieved from http://www.kaleva.fi/uutiset/kotimaa/vihasivusto-tienaa-isoja-tuloja-tunnettujen-suomalaisyritysten-mainoksilla/693237/

- Kazin, M. (1998). The populist persuasion: An American history. New York: Cornell University Press.

- Keeley, B. L. (1999). Of conspiracy theories. The Journal of Philosophy, 96(3), 109–126. doi: 10.2307/2564659

- Knight, P. (2000). ILOVEYOU: Viruses, paranoia, and the environment of risk. The Sociological Review, 48(S2), 17–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-954X.2000.tb03518.x

- Koronaiou, A., Lagos, E., Sakellariou, A., Kymionis, S., & Chiotaki-Poulou, I. (2015). Golden dawn, austerity and young people: The rise of fascist extremism among young people in contemporary Greek society. The Sociological Review, 63(S2), 231–249. doi: 10.1111/1467-954X.12270

- Laclau, E. (2007). On populist reason. London: Verso.

- Lamont, M., & Thévenot, L. (Eds.). (2000). Rethinking comparative cultural sociology: Repertoires of evaluation in France and the United States. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Lazer, D., Pentland, A., Adamic, L., Aral, S., Barabási, A.-L., Brewer, D., … Van Alstyne, M. (2009). Computational social science. Science, 323(2), 721–723. doi: 10.1126/science.1167742

- Levy, K. E. C., & Franklin, M. (2013). Driving regulation: Using topic models to examine political contention in the U.S. Trucking Industry. Social Science Computer Review, 32(2), 182–194. doi: 10.1177/0894439313506847

- Levy, N. (2007). Radically socialized knowledge and conspiracy theories. Episteme; Rivista Critica Di Storia Delle Scienze Mediche E Biologiche, 4(2), 181–192. doi: 10.1353/epi.2007.0022

- Lewandowsky, S., Ecker, U. K. H., Seifert, C. M., Schwarz, N., & Cook, J. (2012). Misinformation and its correction: Continued influence and successful debiasing. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 13(3), 106–131. doi: 10.1177/1529100612451018

- Lewandowsky, S., Oberauer, K., & Gignac, G. (2013). NASA faked the moon landing – therefore (climate) science is a hoax: An anatomy of the motivated rejection of science. Psychological Science. Advance online publication. doi:10.1177/0956797612457686

- Lilly, M. (2016). ‘The world is not a safe place for men’: The representational politics of the manosphere (master’s thesis). University of Ottawa.

- McCallum, A. K. (2002). MALLET: A machine learning for language toolkit. Retrieved from http://mallet.cs.umass.edu/

- Meeks, E., & Weingart, S. B. (2012). The digital humanities contribution to topic modeling. Journal of Digital Humanities, 2(1), 2–6. doi: 10.1613/jair.301

- Miller, J. M., Saunders, K. L., & Farhart, C. E. (2015). Conspiracy endorsement as motivated reasoning: The moderating roles of political knowledge and trust. American Journal of Political Science, 60(4), 1–21. doi: 10.1111/ajps.12234

- Moffitt, B. (2016). The global rise of populism: Performance, political style, and representation. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

- Mohr, J. W., & Bogdanov, P. (2013). Introduction-topic models: What they are and why they matter. Poetics, 41(6), 545–569. doi: 10.1016/j.poetic.2013.10.001

- Mosca, L., & della Porta, D. (2009). Unconventional politics online. Internet and the global justice movement. In D. della Porta (Ed.), Democracy in social movements (pp. 194–216). Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Nefes, T. S. (2013). Political parties’ perceptions and uses of anti-semitic conspiracy theories in Turkey. Sociological Review, 61(2), 247–264. doi: 10.1111/1467-954X.12016

- Nisbet, M. C. (2009). Communicating climate change: Why frames matter for public engagement. Environment: Science and Policy for Sustainable Development, 51(2), 12–23.

- Nyhan, B., & Reifler, J. (2010). When corrections fail: The persistence of political misperceptions. Political Behavior, 32(2), 303–330. doi: 10.1007/s11109-010-9112-2

- Oliver, J. E., & Rahn, W. M. (2016). Rise of the Trumpenvolk: Populism in the 2016 election. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 667(1), 189–206. doi: 10.1177/0002716216662639

- Oliver, J. E., & Wood, T. J. (2014). Conspiracy theories and the paranoid style(s) of mass opinion. American Journal of Political Science, 58(4), 952–966. doi: 10.1111/ajps.12084

- Ostiguy, P. (2009). The high and the low in politics: A two-dimensional political space for comparative analysis and electoral studies (Kellogg Institute Working Paper No. 360).

- Pyrhönen, N. (2015). The true colors of Finnish welfare nationalism: Consolidation of neo-populist advocacy as a resonant collective identity through mobilization of exclusionary narratives of blue-and-white solidarity. Helsinki: University of Helsinki.

- Sapountzis, A., & Condor, S. (2013). Conspiracy accounts as intergroup theories: Challenging dominant understandings of social power and political legitimacy. Political Psychology, 34(5), 731–752. doi: 10.1111/pops.12015

- Saurette, P., & Gunster, S. (2011). Ears wide shut: Epistemological populism, argutainment and Canadian conservative talk radio. Canadian Journal of Political Science, 44(1), 195–218. doi: 10.1017/S0008423910001095

- Schöch, C. (2016). Topic modeling with MALLET: Hyperparameter optimization. The Dragonfly’s Gaze blog. Retrieved from http://dragonfly.hypotheses.org/1051

- Silfverberg, M., Ruokolainen, T., Lindén, K., & Kurimo, M. (2015). Finnpos: An open-source morphological tagging and lemmatization toolkit for Finnish. Language Resources and Evaluation, 50(4), 863–878. doi: 10.1007/s10579-015-9326-3

- Soini, T. (2010, April 26). Eurostoliitto ja Neuvostoliitto. Ploki. Retrieved from http://timosoini.fi/2010/04/eurostoliitto-ja-neuvostoliitto/

- Stavrakakis, Y., Katsambekis, G., Nikisianis, N., Kioupkiolis, A., & Siomos, T. (2017). Extreme right-wing populism in Europe: Revisiting a reified association. Critical Discourse Studies, 14(4), 420–439. doi: 10.1080/17405904.2017.1309325

- Stempel, C., Hargrove, T., & Stempel, G. H., III. (2007). Media use, social structure, and belief in 9/11 conspiracy theories. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly, 84(2), 353–372. doi: 10.1177/107769900708400210

- Swami, V., Chamorro-Premuzic, T., & Furnham, A. (2010). Unanswered questions: A preliminary investigation of personality and individual difference predictors of 9/11 conspiracist beliefs. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 24, 749–761. doi: 10.1002/acp.1583

- Swidler, A. (1986). Culture in action: Symbols and strategies. American Sociological Review, 51(2), 273–286. doi: 10.2307/2095521

- Taggart, P. (2000). Populism. Buckingham: Open University Press.

- Thompson, D. (2008). Counterknowledge. How we surrendered to conspiracy theories, quack medicine, bogus science and fake history. London: Atlantic Books.

- van der Waal, J., & de Koster, W. (2016). Why do the less educated oppose trade openness? A test of three explanations in the Netherlands. European Journal of Cultural and Political Sociology, 2(3–4), 313–344. doi: 10.1080/23254823.2016.1153428

- van Dijk, T. A. (2014). Discourse and knowledge. A sociocognitive approach. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- van Eemeren, F. H. (2010). Strategic maneuvering in argumentative discourse: Extending the pragma-dialectical theory of argumentation. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

- Ward, C., & Voas, D. (2011). The emergence of conspirituality. Journal of Contemporary Religion, 26(1), 103–121. doi: 10.1080/13537903.2011.539846

- Wodak, R. (2015a). Argumentation, political. In G. Mazzoleni (Ed.), The international encyclopedia of political communication (1st ed., pp. 1–9). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

- Wodak, R. (2015b). The politics of fear. What right-wing populist discourses mean. London: SAGE.

- Ylä-Anttila, T. [Tuukka]. (2017). The populist toolkit. Finnish populism in action 2007–2016. Helsinki: University of Helsinki. Publications of the Faculty of Social Sciences 59/2017.

- Ylä-Anttila, T. [Tuukka]., Eranti, V., & Kukkonen, A. (2017). Topic modeling as a method for frame analysis: Data mining the global climate debate. Manuscript submitted for publication.

- Ylä-Anttila, T. [Tuomas]., & Ylä-Anttila, T. [Tuukka]. (2015). Exploiting the discursive opportunity of the euro crisis: The rise of the Finns party. In H. Kriesi & T. S. Pappas (Eds.), European populism in the shadow of the great recession (pp. 57–72). Colchester: ECPR Press.

- YLE. (2016, September 16). Valheenpaljastaja: Varoituslista valemedioista – älä luota näihin sivustoihin. Retrieved from https://yle.fi/aihe/artikkeli/2016/09/16/valheenpaljastaja-varoituslista-valemedioista-ala-luota-naihin-sivustoihin

Methodological appendix

This methodological appendix clarifies some details about the process of creating and interpreting the topic model.

Firstly, the data for any computational text analysis must be pre-processed into a machine-readable format. That entails scraping the relevant text (in this case, from web pages) and tokenisation, in that all punctuation and special characters must be removed so that the data only contain one word per line (a token). Also, stop-words must be removed: function words such as articles and prepositions which are not meaningful on their own. Finally, in the case of a highly inflected language such as Finnish (words are modified with suffixes to express grammatical categories), the tokens must be lemmatised, returned to their dictionary forms, so that words such as luen, luet, lukee (‘I read, you read, she reads’) are recognised by the computer as instances of the word lukea (to read). I scraped and tokenised the dataset using the Beautiful Soup library in Python (Beautiful Soup, Citation2017), removed a custom list of stop-words for Finnish (available at https://populistknowledge.wordpress.com/), and lemmatised the data using the FinnPos toolkit (Silfverberg, Ruokolainen, Lindén, & Kurimo, Citation2015).

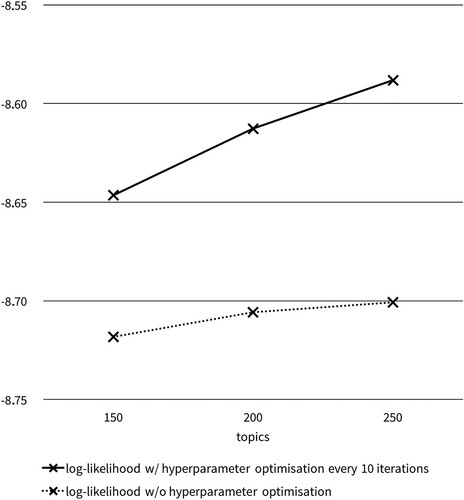

How should the number of topics be chosen? There are two main approaches: a quantitative and a qualitative one (see Chang, Boyd-Graber, Gerrish, Chong, & Blei, Citation2009). Since my study is of a mixed-methods bent, I used both quantitative and qualitative methods in choosing the topic count as well. Firstly, MALLET can calculate a measure of model fit: how likely would the actual data be, given the model we created? This measure is shown in for models of 150, 200, and 250 topics, each with 256 iterations of the model.

Also shown are models with two different MALLET settings regarding hyperparameter optimisation. In brief, hyperparameters affect the distribution of topic probabilities, since optimising them between iterations of the model lets some topics ‘weigh’ more (as is natural in text collections, some word clusters being more prevalent than others). This generally improves model fit by enabling the model to include marginal topics, not just those associated with the most-used words, but can also go too far. High variance in topic probabilities creates models that comprise mostly of these relatively rare topics, missing more general trends (Schöch, Citation2016).

This leads us to the importance of qualitative work, the quantitative measure of model fit being meaningless if the model does not help in interpreting the data. As shows, in these data, topic counts of 150, 200, and 250 give an increasing log-likelihood number for model fit (measuring how likely it is that the model would generate the data), but increasing the topic count also means diminishing returns from topic modelling, as the researcher must interpret a larger number of word clusters. Hyperparameter optimisation also clearly gives a better model fit here, letting the topics reflect both more and less prevalent discussions in the data.

Since I am interested in potentially marginal discussions as well, I selected the model incorporating hyperparameter optimisation. Qualitatively, looking at the word lists, this created a larger number of relevant topics for my research design, whereas without hyperparameter optimisation, the topics were too general. The model-fit likelihood measure was also better quantitatively. As for topic count, I qualitatively compared the top words of the 200- and 250-topic models and noted that the same topics of interest were present in both models. Thus, despite the 250-topic model having better model-fit likelihood, I selected the 200-topic model to make the qualitative work somewhat less laborious (with hyperparameter optimisation, centre marker on the solid top line in ).

After running the model, the qualitative interpretation starts with the selection of relevant topics. We have previously documented a suggested procedure for this (Ylä-Anttila et al., Citation2017). In a nutshell, I first use the lists of top words per topic (in this case, the top 20 words) to identify a preliminary label for the topic. If one cannot be distinguished based on the top 20 words, the topic is discarded as not coherent enough. If one can be distinguished but seems irrelevant to the research question, the topic is discarded as irrelevant. In this first phase, 17 of 200 topics were selected and the rest discarded – overwhelmingly because of irrelevance, not because of lack of coherence. Almost all 200 topics clearly represented a distinct frame, indicating good model fit. Word lists in Finnish for all 200 topics are available online at https://populistknowledge.wordpress.com/.