ABSTRACT

Catholic bourgeois contestations against ‘le gender’, and against ‘bourgeois-bohemians’, characterised ‘La Manif Pour Tous’ and ‘Les Veilleurs’, French social movements which mobilised intensely in 2013 against legalisation of same-sex marriage. Drawing from primary field observations of movement events, and from interviews, I argue that moral epistemics – knowledge politics oriented around moral issues – were central to the movements. Additionally, these moral epistemics were structured by the class positioning of conservative bourgeois Catholics. I trace how contestations against ‘le gender’ were framed as critiques of how moral knowledge is produced and irresponsibly disseminated by rival bourgeois actors, and how conservative activists contrasted themselves as educated and thoughtful subjects whose ideas emerged autonomously and outside the Church hierarchy. Studies of conservatism should thus not only analyse the theological content of religiously-grounded conservative movements, but should also examine how conservatives criticise the circuits of knowledge-production and dissemination of relationally antagonistic groups.

La Manif Pour Tous burst onto the French political scene in late 2012, a French conservative movement that, throughout the spring of 2013, staged street protests against the legalisation of same-sex marriage.Footnote1 The movement initially surprised many by its size and organisational capacities, and even puzzled some in the movement’s mobilisation against gender theory (). Yet with the benefit of several years of hindsight, observers now see that La Manif Pour Tous (LMPT) marked a new era in the political organisation of Catholic conservatism in France (Béraud & Portier, Citation2015). It was also one of the best-organised movements in a European, and now global, wave of ‘anti-gender’ activism, a conservative backlash against legislating sexual and gender equality, and against researching and teaching about sexual and gender diversity (see Stambolis-Ruhstorfer & Tricou, Citation2017).

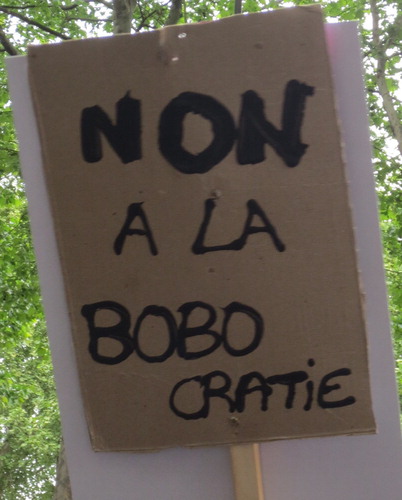

Notably, however, some in LMPT also contested the role of the secular bourgeoisie in France. For example, in spring 2013, during a national march in Paris, I observed a middle-aged white male protestor holding a hand-scrawled placard declaring, ‘Non à la Bobocratie’, protesting against rule by bobos, or ‘bourgeois-bohemians’ (). American writer David Brooks coined the portmanteau ‘bobo’ in his book, Bobos in Paradise (Citation2000). This was a social group which, he argued, combined the ‘bourgeois world of capitalism’, with ‘bohemian counterculture’, and thus the emergence of bourgeois-bohemians, or bobos. Although branded by an American author, the concept has since circulated extensively in French popular discourse. Taking the anti-bobo protest sign seriously, and also taking seriously mobilisation against a social-science theory, here I add to the mounting body of research on ‘anti-gender’ movements, and to research on the growing groundswell of anti-university politics, by focusing on the class and knowledge politics of conservative bourgeois activists within LMPT.

LMPT events displayed few religious justifications for their activism. This is not unusual within a global trend in the secularisation of religious-movement-affiliated tactics (Paternotte & Kuhar, Citation2017). Some argue that it was also a strategy for LMPT to legitimate itself in the public sphere (for example Stambolis-Ruhstorfer & Tricou, Citation2017). I do not deny these factors, yet I wish to emphasise a different aspect of LMPT. Drawing on scholars’ observations that anti-genderism can mean different things to different socio-political groups (Mayer & Sauer, Citation2017), and on field observations and interviews with LMPT members and others in a related student movement, Les Veilleurs (LV), I argue that Catholic conservatives framed their activism through the interrelationship between class and what I call ‘moral epistemic’ politics.

Although French Catholicism is sociologically and ideologically diverse (Raison du Cleuziou, Citation2014), core LMPT and LV leadership were comprised of highly educated Catholics, many of whom were at least upper middle-class, and some of whom were from the grande bourgeoisie, a merger of the wealthy bourgeoisie with families of aristocratic lineage (Della Sudda, Citation2017; Durand, Citation2017). The movements also contained more extreme clusters, especially represented in LMPT by devout Catholic activist Béatrice Bourges, who eventually became associated with a radical underground organisation called Le Printemps Français, ‘The French Spring’. Some figures from the radical right-wing National Front party (now renamed the Rassemblement National) such as Marion Maréchal Le Pen, who is Marine Le Pen’s niece and is more socially conservative than her aunt, supported the movement. However, she was not invited to be an official representative of the party’s coalitional leadership.Footnote2

During its peak period of activism, relative moderates within the movement struggled to make LMPT a multi-confessional conservative organisation. It tried to incorporate Jews and Muslims, while also displaying religious diversity during its street protests (see ). This diversity, however, was an illusion. Its core was animated by economically comfortable and university-educated Catholics whose activism has long been channelled through Catholic pro-family organisations (Béraud & Portier, Citation2015). When other religious and socio-economic groups joined collective LMPT events, their claims could be distinct from those of the conservative bourgeoisie (Massei, Citation2017). For example, Muslim participants in a large LMPT march in Paris in spring 2013 were not contesting ‘gender theory’, but rather were carrying a banner declaring: ‘We want jobs, not gay marriage!’.

Figure 3. ‘We want jobs, not gay marriage!’ Protest sign by ‘Muslims for Childhood’, at a Manif Pour Tous march. Photo: the author.

This analysis draws from primary field observations, supplemented by interviews with movement members and founders. I observed three of the major national LMPT marches in Paris in March, April, and May of 2013; four small Paris rallies in spring 2013; and eight smaller formal and informal events of its offshoot student movement, Les Veilleurs. I was offered a rare glimpse into the movement’s conservative bourgeois leadership during a window of openness to a foreign researcher.Footnote3 My first direct contact with movement members was through meeting LMPT activists when they staged a protest against an academic conference on ‘Going Beyond Marriage’ in Paris in April 2013. Although the French conservative bourgeoisie is a social group which cherishes discretion and is notoriously difficult for researchers to access (Pinçon & Pinçon-Charlot, Citation2005), this encounter opened doors for me with LMPT and LV Catholic conservatives, and through snowball sampling I was able to interview fifteen LMPT and LV leaders and activists. The analysis focuses on mostly highly educated, mostly upper-middle-class, but also sometimes aristocratic, conservatives who identified with the more centrist positions of LMPT and LV. All but one interviewee self-identified as Catholic, and two came from families of immigrant origin.

I employ an interpretive political-sociological approach, which focuses on how these actors interpreted their activism, and against whom they saw themselves as acting (see Chabal & Daloz, Citation2006). In order to do so, I first clarify how contestations against le gender were a form of moral epistemics, and then how mobilising around moral epistemics was also a form of class politics for French conservatives. In doing so, I frame actors’ positions within a Bourdieusian field analysis, bringing to light how moral-epistemic interventions are the product of battles between competing factions of the bourgeoisie.

Mieke Verloo argues that anti-gender discourse needs to be understood as a form of epistemic politics (Citation2018). For Verloo, ‘episteme’ refers to a ‘system’, which includes media, religion, and science, all of which define reality. Her analysis of anti-gender politics is insightful in framing anti-genderism as an epistemic battle. At the same time, I add more specificity to her broad notion of ‘episteme’ and show how institutions and actors within an epistemic system are positioned relative to one another, and how they vie for authority within epistemic fields.

In contrast, American political theorist Michael J. Sandel (Citation1996) analyses epistemic models from the perspective of individual choices. He argues that moral judgements do not emerge sui generis, but are formed through preferred sources of moral knowledge. Individual moral positions in relation to stem cell research, for example, do not only assert a position for or against stem cell research, but draw on different authorities, such as university-based scientific authorities, versus religious authorities – in other words, from different epistemic authorities – to make moral claims. While Sandel suggests that moral positions are an individual choice between sources of moral knowledge, he does not trace how contestations unfold between clashing epistemic authorities, and the kinds of arguments social actors deploy to claim the supremacy of one epistemic authority over another.

Studying French Catholic conservatives with high levels of education presents an opportunity to analyse how social groups adjudicate between vying moral-epistemic authorities, not simply as individual moral choices, nor within broad epistemic systems. Employing Pierre Bourdieu’s analysis of class contestations among sub-factions of the bourgeoisie, I argue that educated Catholics’ sociological positioning places them in the crosshairs of two structures of moral epistemics. Their own prestige, education, and often high-status professions are conferred by the authority of the secular university, whereas their moral views in relation to family, marriage, and sexuality are structured by the Catholic Church.

Highly educated Catholics therefore struggle for recognition in a field of bourgeois distinction where they cannot convert their moral knowledge into cultural capital in the secular field of distinction. They struggle for distinction against the putative empty morality of financial elites who are often the wealthier members of the bourgeoisie, and against the putative moral paucity of secular cultural elites whose secular knowledge hierarchy they perceive as a form of moral epistemics rivaling their own, especially on issues to do with human nature, family, sexuality, and gender relations.

Anti-gender activism on the part of bourgeois conservatives thus gathered in two processes at once. First, contestations against le gender were a battle over moral epistemics, especially over who can define the meanings of gender, sexuality, human development, and the family. They criticised the concept of gender as a rival moral episteme by questioning how knowledge is produced and disseminated by secular intellectuals and activists. And, secondly, these contestations expressed resentment against a rival faction of the bourgeoisie with whom conservative bourgeois actors share a close social space, and whom they viewed as competitors in the field of distinction.

Here I first contextualise the social, economic, and epistemic positioning of bourgeois Catholics in France in order to pinpoint how conservative moral epistemics and French class politics inter-relate. Then, drawing on field observations and interviews, I identify the strategies deployed by LMPT, and a related student movement, Les Veilleurs, in delegitimising university-based production of knowledge and in the circulation of the concept of le gender, and its proponents.

While the inter-relationship between class and moral epistemics examined here is specific to my observations of LMPT and LV, and to the informants I interviewed, I suggest that this analysis holds implications for broadly viewing conservatism as moral epistemics around which conservative governments and social movements are increasingly mobilising. Current epistemic conflicts, such as opposition to gender theory, certainly reflect mounting resistance to gender and sexual equality. Yet, they arguably also reflect increasing opposition to university-based production of knowledge in the experimental, medical, and social sciences.

Situating the French Catholic bourgeoisie: Moral epistemics and bourgeois distinction

Contextualising French political Catholicism

Sociologists of French Catholicism note that while only some 4.5 percent of French Catholics regularly attend Sunday mass, even within this numerical minority, Catholics in France remain diverse (Raison du Cleuziou, Citation2014). One contemporary cleavage identified by Phillipe Portier is between Catholicisme d’identité and Catholicisme d’ouverture (Citation2012). These roughly translate to ‘identitarian’ Catholicism versus ‘bridging’ Catholicism. Identitarian Catholics insist on the value of tradition. They have also adapted the discursive formulations of minority identity politics in order to stake out their place in French politics (Carnac, Citation2017). At the other pole are the ‘bridging’ Catholics inspired by the transformations wrought by the modernisation of the Church since the 1960s, especially since Vatican II and its articulation of a social justice vision for Catholic engagement in everyday life (Portier, Citation2012; Dumons, Citation2017).

Identitarian Catholics, and pro-family activists, were central in forming LMPT and LV (Della Sudda, Citation2017), and began mobilising when the concept of ‘gender’ was introduced into national life sciences school curricula by a centre-right government in 2010 (Béraud & Portier, Citation2015). Catholic pro-family groups, long active in French politics (Rétif, Citation2017), had been at the core of Catholic activism against the legalisation of civil unions for gay couples in the late 1990s. Following legalisation of PACS (civil unions, including for same-sex couples), the Church leadership articulated critiques of gender and gender studies, some fifteen years prior to the Socialist government’s announcement in 2012 that they intended to pass legislation recognising same-sex marriage (Carnac, Citation2014; Béraud & Portier, Citation2015).

However, it is significant that French Catholic conservatism is also correlated with middle-class, upper-middle-class, and even elite class membership (Lamont, Citation1992; Pinçon & Pinçon-Charlot, Citation2007; Della Sudda, Citation2017). With the decline in economic capital of the French conservative aristocracy, and their strategic compensatory move towards diversifying their capital into moral capital (De Saint-Martin, Citation2000; Fradois, Citation2017), it is no surprise that LMPT offered an opportunity for bourgeois, and even aristocratic, conservatives to assert their distinct forms of moral capital. If class had not mattered to members of LMPT, their contestations would have been free of resentments expressed against other fractions of the bourgeoisie, and LMPT and LV would have represented a wider range of Catholics, for example more from immigrant groups. It is therefore imperative to understand LMPT and LV conservatives not only as carriers of religious beliefs, but also as class actors.

The label ‘religious right’ highlights the religious underpinnings of anti-LGBTQ rights movements, especially in Canada and the United States (Fetner, Citation2008; Heath, Citation2012; Warner, Citation2010). Scholarship on anti-LGBTQ activism in Europe also uncovers the religious roots of anti-LGBTQ rights activism (Smith, Citation1994; Kubica, Citation2009; Ayoub, Citation2014), and multi-religious global alliances forging what Clifford Bob has labelled ‘the global right wing’ (Citation2012). Many analyses of LMPT likewise tend to emphasise the Catholic theological roots of the movement. I do not question the religious origin of anti-LGBTQ rights politics. However, in order to explain why specific religious groups take up particular discursive and activist repertoires, we need to incorporate other sociological factors motivating activism. I therefore treat religious conservatives as more than purely religious actors acting out of theological conviction.

In analysing educated members of LMPT and LV, I argue that bourgeois class positioning also motivated their political engagement, especially in how struggles over moral epistemics define conservative bourgeois positioning in France. To this end, I turn to Pierre Bourdieu’s account of class-formation and reproduction as, firstly, a general model highlighting the relational nature of class self-identification; and secondly, as a still-relevant descriptor of French bourgeois intraclass struggles.

The conservative bourgeoisie, the search for distinction, and moral epistemics

Pierre Bourdieu’s general model of class stratification identifies social class as more than an objective economic position. Social class, in his framework, incorporates ‘cultural capital’, and is furthermore relational and, to a certain degree, subjective, in that social groups constantly identify who are the other groups against which they distinguish themselves. Through Bourdieu’s framework, the sociologist can identify the relationality of a given class by paying attention to the groups against which members of a class see themselves in an antagonistic relationship. Groups occupying a close social space often engage in the fiercest of competition such as, for example, among sub-factions of the bourgeoisie.

The national specificity of Bourdieu’s analysis lies in how the French system of higher education plays a crucial role as a site of bourgeois reproduction and classificatory struggles (Bourdieu & Passeron, Citation1964, Citation1970). The French state supports a centralised national education system of accreditation which forms elites, but also divides between cultural and financial elites (Bourdieu, Citation1996). Bourdieu emphasised that cultural elites are, nonetheless, the dominated fraction within the generally dominant bourgeoisie. Boundaries between bourgeois factions are marked by either emphasising economic capital or emphasising cultural capital. Importantly, however, Bourdieu’s concept of cultural capital describes the world of secular educated highbrow bourgeois elites whose non-financial cultural capital enables them, in certain domains, to appear more dominant than economic elites, and who employ symbolic violence as a weapon in their arsenal (Bourdieu, Citation1992).

The Catholic bourgeoisie were outside Bourdieu’s class model, but Bourdieu’s own model can be modified in order to situate them. One vector of distinction for the Catholic bourgeoisie has been to differentiate themselves from the flashy new rich (see Lamont, Citation1992; Fradois, Citation2017). They have sought to re-moralise the centre-right political party, Les Républicains, against the moral vacuity of finance capital and the conspicuous consumption symbolised by former centre-right president Nicolas Sarkozy in the early 2000s. This resulted in formation of Sens commun in December 2013, a ‘values-based’ conservative bloc nested within the centre-right party (Raison du Cleuziou, Citation2018; Portier, Citation2018).

Another vector of distinction is against the ‘vulgar’ petty-bourgeois and working-class radical right. And as was apparent in the LMPT and LV movements of 2013, yet a third vector of distinction is against the secular cultural bourgeoisie. The latter compete with Catholic conservatives not only in the content of their ideas, but, perhaps more importantly, in their perceived capacity to disseminate and receive recognition for ideas which conservatives claim demoralise the republic. Educated Catholic conservatives care a great deal about ideas, their moral valency, who produces them, in which institutions, by which authorities, and whose ideas are more valued by other elites and society at large. As my observations of LMPT and LV members show, conservative bourgeois Catholics in France resent feeling that they are the dominated faction within the bourgeoisie in the realm of epistemic production and dissemination.

The class positioning of bourgeois Catholic conservatives is therefore complex. On the one hand, members of the Catholic bourgeoisie take seriously the place of the university and of intellectuals in the public sphere. They pursue higher education, and accrue degrees and certificates. These are essential for the maintenance of their class status. The historic merger of aristocratic families into the grande bourgeoisie, those at the top of the bourgeois hierarchy, entailed not only strategies of inter-marriage with new capitalist families, but also the adoption of rational-legal markers of status reproduction by ensuring that their children attend the right schools and earn advanced degrees from prestigious institutions of higher education (Pinçon & Pinçon-Charlot, Citation2007). On the other hand, observant bourgeois Catholics are also immersed in the world of the Church hierarchy as another source of authoritative knowledge-production and dissemination. This second structure of knowledge-production accompanies them throughout their entire lives so long as they are practising Catholics.

In the current structure of competition for distinction in France, however, educated Catholics cannot convert their Church-based moral knowledge into recognised cultural capital. Moral knowledge sourced in the Church is not a fungible asset on the secular market of distinction. In turn, they resent it when secular university-produced ideas spill into the sphere of moral epistemics, which they believe should remain the domain of the Catholic Church.

The university, and the voice and role of the secular intellectual, therefore matter a great deal to educated Catholics as sources of authority, but simultaneously and paradoxically, also as competing sources of capital which thwart their capacity to convert religious knowledge into cultural capital. Class antagonism over whose knowledge counts more, especially whose moral knowledge, shapes the activism of educated French conservatives. Mobilisation against le gender was a battle in trying to raise the value of Catholic moral epistemics in the market of distinction, where secular knowledge is, at one level, taken seriously, and on another, contested as a competing epistemic structure.

Conservatives as class actor

In the spring of 2013, on the eve of legalisation of same-sex marriage by the French National Assembly, a day-long conference entitled ‘Beyond Marriage’ took place in Paris at the École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales (EHESS), a prestigious postgraduate school of social sciences. Public intellectuals associated with Queer theory and gender studies, such as Éric Fassin, Didier Eribon, and Daniel Borrillo presented their reflections to a packed auditorium. An EHESS audience would have normally been supportive of same-sex marriage. However, the atmosphere was surprisingly tense, for amongst the audience were several LMPT activists who were asking provocative questions at the end of each panel. One activist recorded some of the proceedings on his mobile phone, provoking a sense of unease among conference participants. The activists’ questions, in turn, were met with hissing by audience members, and audience members would occasionally shout, ‘Fascists!’ in their direction.

Although the conference posters had billed the event as open to the public, LMPT activists were treated as trespassers. Bourgeois conservatives had infiltrated into the geographic and symbolic heart of French left-intellectual life. Rather than respecting collegial norms of exchange, but also hidden structures of authority typically played out in a university lecture hall, their questions during the Q&A periods were brazen and aggressive. I approached the men during a break, and it was there that I met Alexandre, a white man in his thirties. We met again almost two weeks later at a café in a smart neighbourhood near his home in central Paris. He was dressed in a conservative business suit, and after our meeting was planning to head to his job in a prestigious engineering firm in La Défense business district. Alexandre came armed to our meeting with materials he had gathered on LMPT and on the changes the government had made to the school curriculum. Then, suddenly, he described to me his frustration with intellectuals:

I don’t like the arrogance of intellectuals. They constantly refer to me and other activists as fascists, extremists, homophobic. The media too emphasises that, and it’s a caricature of who we are. We’re not violent. If at all, we’re more open to gays than the gay movement itself. I was educated at a school of commerce. But still, I understand these things.Footnote4

Several institutions of higher education in France are classified as Grandes Écoles, the most elite and competitive ‘great schools’, some of which Pierre Bourdieu identified as producing the ‘cultural nobility’, and others producing economic and administrative elites (Bourdieu, Citation1996). Although Alexandre was a graduate of one of these elite schools of commerce, his criticism was pointedly against secular cultural elites. He and his fellow LMPT activists had tried to challenge the world of university-based knowledge and secular intellectuals on their home turf. He narrated his own LMPT activism in antagonistic terms against the dominance of secular intellectuals.

Whereas Alexandre was a member of the elite conservative bourgeoisie, some activists experienced their participation in LMPT and LV as an opportunity for upward mobility, enabling contact with exclusive social classes of which they were not members. One such interviewee was Marie, a twenty-seven-year-old legal assistant who self-identified as Catholic and an LV activist, and is from an Iraqi immigrant family of Chaldean Christians, an ancient Eastern Church with an Aramaic liturgy and rites distinct from those of the Roman Catholic Church. She lived in a banlieue north of Paris, and spoke with an accent which placed her in a lower class positioning relative to other LV participants. She first discovered LMPT and LV by watching news reports of protest events in early spring 2013, and described how she decided to attend an LV event when she came across an online article claiming that LMPT had ‘taken all the homophobes out of the closet’.Footnote5 She was angered that the press was calling people ‘like her’ homophobic, and then decided to join the Paris-based movement.

When asked if other members of her community were also active in the movement, she responded, ‘I think I’m the only one from my community to be involved in Paris. We’re concentrated in a northern banlieue of Paris, so it’s not very practical to go into the Paris city centre in the evening.’ Marie was aware of the class distinction between her and the LV activists she had met, and expressed admiration for them:

LV comes from a certain elite. They hold high positions, or they are engineers, doctors. That’s why they have more access to culture. These kind of people, when they’re young they discuss politics at the family dinner. Me, I come from a banlieue. I’m a girl [laughter], I was taught just to cook, and that’s all. We didn’t discuss political debates. The little bit of culture I have I acquired from school. The big moment in French history which inspires me is the French Revolution, the Age of Enlightenment. For me Les Veilleurs reminds me of the spirit of the Enlightenment.

Joseph,Footnote6 an early LMPT activist with an openly gay son, self-identified as being a Jew of North African origin, and saw himself as a leftist atheist. He is married to a Catholic woman, and admired Catholics for their commitment to universal values. He believed that ‘Jews can be great when they’re not navel-gazing, such as Jesus Christ and Freud. But Catholics are the keepers of good values other portions of society have forgotten.’Footnote7 He explained that he had reached out to the early movement founders in late 2012. He first sent messages to them through Facebook, since otherwise the Catholic founders were not individuals with whom he had had contact before.

He had heard that Frigide Barjot, a comedian and minor celebrity who has written about ‘coming out’ as Catholic (see Barjot, Citation2011), was organising a counter-movement to the proposed law in late 2012. Barjot is a deliberately bawdy personality whose stage name parodies that of French film actress Brigitte Bardot, and which roughly translates to ‘Frigid Bananas’.Footnote8 Notwithstanding her media persona, Frigide Barjot – whose real name is Virginie Merle, and who has since dropped this stage name – is in fact an educated high-bourgeois Catholic woman from Lyon, a city with a strong Catholic bourgeois tradition (Béraud & Portier, Citation2015). Joseph claimed that within hours of contacting her on Facebook, she called him. He believed that Barjot was eager to incorporate someone like him who could represent the religious and socio-political diversity she was seeking for the movement.

When I interviewed him in the spring of 2013 in his home, the movement was no longer at its peak effervescence. He wistfully showed me videos of his speeches at LMPT events small and large. The movement had taught him to be a public speaker, and he had travelled the country delivering his message to growing crowds. As in the case of Marie’s description of her experience with LV, he described how he enjoyed being part of LMPT because it had given him a chance to be part of something bigger, and also because it had given him a chance to meet people, such as Catholics of aristocratic origin, with whom he had never had a chance to socialise before. Despite coming from a radically different social background, he had become good friends with a Catholic woman from an old French family who was an LMPT founder, and with whom he enjoyed ‘having a good laugh’.

Conservative claims to reflection and epistemic autonomy

Staging collective reflection

Young Les Veilleurs activists emphasised the moral epistemics behind their movement, and movement events were staged as public displays of reflection. Clara, a twenty-five-year-old literature student at the Catholic University in Paris, was active in LV during the spring and summer of 2013. Her brother had been a founding a member. She too had immersed herself in the movement in Paris, and also in helping guide LV events throughout France. Although she was a student at the Catholic University in Paris, she claimed that she did not speak openly at the university about her involvement in the movement, since not everyone supported it.Footnote9

The movement had, in her words, emerged ‘spontaneously’. Participants would request permits from the city to have sit-ins during the evening, often until past midnight. Once night would fall, young women and men would quietly sit and read literature, poetry, and recite speeches. These texts crossed old political divides. At one vigil I observed, participants recited passages by Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Émile Zola, Mahatma Gandhi, and even Max Weber and Antonio Gramsci, as sources of inspiration.Footnote10 Clara emphasised that the events were designed for reflection:

We ask ourselves: Where are we from, and where are going, where do we want to go? We need to reflect more and more. We return to reading. We’re now in an information ‘overdose’ because of social media, and we don’t take the time to reflect anymore. So in Les Veilleurs we read texts, and it shapes us. It’s a kind of education.

Yet Clovis, a student in a Parisian faculty of public law, which he underscored was a prestigious one, claimed that the movement was Catholic in spirit:

There are Christian values behind the movement. We are influenced by this aspect of community, of sharing, which is emphasised a lot in [priests’] homilies. I think we’re educating others about our relationship to one another. Also, in Catholicism, prayer is a time for silence and for reflection […] For the youth in our movement who aren’t Catholic, it’s incredible to consider that in a world where our minds are always elsewhere and with our mobile phones always on, we say, ‘Stop! Reflect on what you were before, on what you are now, and what you will do in the future for your society, for your neighbours.’ We’re always in conversation.Footnote11

Claiming moderation, complexity, and epistemic autonomy

LMPT and LV informants and protest signs insisted that they were ‘thoughtful’, non-ideological, and apolitical. In so doing, they emphasised that their position on same-sex-marriage came from a life of reflection. They claimed that their activism was rooted in autonomous knowledge-formation, and this knowledge had not been transmitted to them hierarchically from above. Whereas Catholics are presumed to be subject to Church hierarchy in knowledge-production (Sapiro, Citation2009), secular actors claim epistemological autonomy in contrast to religious epistemic heteronomy. LMPT actors, however, turned the tables on their secular adversaries, and insisted that their own ideas derived from autonomous thought and reflection.

In a lengthy interview with Céline in the affluent western outskirts of Paris, she described to me her views about homosexuality, and how she had come to be involved with LMPT.Footnote12 Céline is a married heterosexual mother of six, is a practising Catholic, and is a member of the grande bourgeoisie with aristocratic lineage. She helped create a website with a sophisticated graphic design aesthetic, now pulled offline, and which had been dedicated to video testimonials by openly gay and Catholic individuals (mostly men) who opposed same-sex marriage. Céline explained that she had been reflecting on the sources of homosexuality for over twenty years, after her brother had come out of the closet as gay. Through being psychoanalysed, she had come to realise that homosexuality is the result of the initial fusion baby boys experience with their mother, and due to either unhappiness in the parents’ marriage, or a weak paternal figure, the child fails to move to the next stage of sexual development. Rather than switching towards identifying with the father, the boy remains fused to the mother and becomes homosexual.

Céline had recounted to me a version of the Freudian Oedipal complex, but had not labelled it as such. Moving next to a Lacanian plane – though again she did not cite the origin of her ideas – she argued that alterity is the ideal for sexual development. It is not only the basis of heterosexuality, but is, according to her, ‘the basis of language, the symbolic order, and of civilisation itself’. Céline believed that children who did not make the move towards sexual alterity could not help it, and she therefore felt enormous sympathy for homosexuals whose sexuality is experienced as a kind of suffering. She then tied these psychoanalytic views to the Biblical Genesis story:

God created humans in the form of man and woman, separating woman from man, and also cast them out from the Garden of Eden. Alterity and separation are already there. They’re difficult, but necessary steps towards individual development. But they also create opportunity for great beauty. Heterosexual sex enables a unification that overcomes separation. So does communion. This is a moment of comfort which homosexual sex can’t achieve.

Céline’s ideas did not emerge from LMPT itself. The French Church hierarchy since the mid-1970s transitioned from a direct condemnation of homosexuals to a theological position condemning homosexual acts, while expressing compassion for homosexuals (Carnac, Citation2014). LMPT protestors claimed not to be hateful towards individual gays and lesbians, and rejected the claim that they were homophobes ().

Additionally, intellectual historian Camille Robcis has traced how Claude Lévi-Strauss’s structural anthropology and Jacques Lacan’s psychoanalytic theories entered wider legal and policy milieux in France mid-twentieth-century (Robcis, Citation2013; see also Fassin, Citation1998). Following the Second World War, both Lévi-Strauss and Lacan developed ahistorical and universalist accounts of kinship structures as the foundation of what Robcis terms the ‘structuralist social contract’. Both thinkers treated the rules of kinship and those of (hetero)sexual organisation as the basis of social bonds, and for Lacan they were the basis of psychic development. Robcis shows how aspects of their intellectual corpus were integrated into the ideological outlook of ‘familialist’ actors who influenced family law reforms in the post-war period. Since the 1990s, following the legalisation of homosexual civil unions in France, members of the Catholic leadership in France have articulated arguments against same-sex unions, and same-sex marriage, using secular anthropological and legal arguments (Béraud & Portier, Citation2015).

Interviews with educated conservatives showed that these intellectual legacies shaped activists’ outlook. Emphasis upon the symbolic importance of heterosexual parents as the basis of healthy psychic development, and upon sexual alterity as the structural basis of culture and civilisation, pervaded discussions with conservative LMPT and LV activists. Clara, a student and LV activist, explained for example that although her parents had taken her to protest events against the legalisation of civil unions for homosexuals in the late 1990s, she now accepted it, but wished that civil unions would remain the only option available to same-sex partners since same-sex marriage would ‘transform civilisation’.Footnote13

Like Céline, who emphasised that her position was one thoughtful moderation, Joseph, the Jewish LMPT activist, maintained, ‘We spent a lot of energy pushing back Civitas and movements that were too much to the right.’Footnote14 Auguste, a twenty-four-year old cinema student and LV activist who claimed he hid his views from colleagues in the cinema world, also believed that his view was moderate and thoughtful, but that these positions were deliberately misrepresented by the secular media. He commented that, ‘Whenever they don’t want a topic to be raised, if it’s something that disturbs the system, they say, “It’s from the radical right.” It ends the debate.’Footnote15 LMPT and LV informants thus tried to articulate multifaceted accounts of their opposition to same-sex marriage. They were eager to show that they were not merely parroting Church ideology, and were not radical-right ‘ideologues’, but thoughtful and intelligent individuals with a theoretically complex and temperate worldview.

‘Le gender’ as coerced and irresponsible knowledge

Lobby-talk

Despite wishing to show their moderate stance, lobby-talk permeated the LMPT and LV milieux. Denunciation of the Americanisation, and corruption, of French political life through the rise of ‘lobbies’ is common now in French political discourse. The extreme right has long deployed a classical secret plot narrative, which claims that a small and invisible group is working behind the scenes to take power, and moreover to wield economic control, without revealing who they are, nor their true intentions (Chebel D’Appollonia, Citation1992). LMPT members likewise argued that lobbies are undemocratically corrupting the republic. Furthermore, their lobby-talk could be mobilised to emphasise LMPT’s own thoughtfulness versus the imposition of ideas foisted upon France by the ‘LGBT lobby’, and the new appearance of a ‘gender lobby’.

Céline explained that she had helped create the website dedicated to video testimonials of gay men and women opposing same-sex marriage due to her sense that alternative gay voices had been ‘silenced’ by the ‘LGBT lobby’. Gay citizens who did not support same-sex marriage

[D]on’t have a place to speak, since the platform has been taken by the LGBT lobby, and the gender lobby. The LGBT lobby forces you to adhere to their ideology, especially if you’re part of the Socialist Party.

They don’t allow people to become individuals, but rather push an ideology, an agenda. They don’t search for the truth. [Justice Minister] Taubira is one of those too. Sure, on the right there are the Catholic intégristes [anti-modern traditionalists] who are ideological. But I’m not ideological. The LGBT lobby is ideological. Taubira is ideological.

The last time there was this kind of ambience was [the student protests of] May 1968, which lasted two months. But ours lasted six to seven months […] We were the ones who demanded a debate, not the partisans of the law. It was asymmetric. We were the creative ones.Footnote16

Some, however, did adopt a more classic conspiracy theory narrative, and believed that behind the ‘LGBT lobby’ stood the power and money of a single individual: Pierre Bergé. The long-time partner of haute-couture fashion designer, Yves Saint Laurent, Pierre Bergé had been openly gay for decades, and was a high-profile supporter of gay rights causes in France until he passed away in 2017. In a 2012 quote cited in the centre-right newspaper, Le Figaro, Bergé was reported to have rhetorically asked, ‘Renting out one’s womb for making a baby, or renting out one’s hands to work in a factory, what’s the difference?’ (Mallevoüe, Citation2012). LMPT activists seized on this quote as proof of the excessive commodification and moral vacuity of the ‘LGBT lobby’ in its support of commercial surrogacy for gay parents.

Bergé was accused of being a major player behind the ‘LGBT lobby’. Philippe, an openly gay practising Catholic, and an LMPT activist in his fifties living in Paris and working in the arts, saw his own LMPT activism as a chance for people like him to have more of a place in the ‘Christian family’, and to distance themselves from what he described as the excessively sexualised, violent, and materialistic culture of Paris’s Marais district, the city’s ‘gay ghetto’. He believed that ‘Bergé heavily funded Hollande’s [2012 presidential] campaign. Even though same-sex marriage was not really that important to him, he had to follow through with his promise to Bergé and push for it.’Footnote18 Yet when Philippe discussed Socialist Justice Minister Christiane Taubira’s reasons for supporting same-sex marriage, he was perplexed as to why she would have done so, and speculated that she must have experienced ‘something in her family life’ during childhood to lead her to support same-sex marriage.

François, an openly gay winegrower and local mayor in Burgundy, from a family with aristocratic origins, and who had also once lived in the Marais district before moving to Burgundy to live with his male ‘friend’, tied Bergé to ACT UP, an organisation originating in the United States which advocates for people with HIV AIDS, and which founded a French chapter in 1989:

They number just over one hundred members. They have disproportionate power. I don’t like the word ‘lobby’. I won’t resort to ideas about plots, like Jews, or Freemasons. But yes, they have too much power, especially a small group of elites in Paris. And Pierre Bergé is the worst of them. ACT UP declared itself to be the voice of homosexuals, but I never supported them, and they don’t stand for my ideas.

Philippe and François adopted, at times, a right-wing conspiracy narrative, while at the same time they sought to distinguish themselves from those narratives. Believing, on the one hand, that Bergé and ACT UP had hijacked the republic, they argued, on the other hand, that they did not believe in conspiracy theories, and gestured towards a psychoanalytic account of why someone might be supportive of same-sex marriage. In this narrative, LGBTQ activists and supporters are driven by psychic traumas which halt reflection. Either way, these LMPT activists portrayed themselves in contrast as thoughtful, meditative, even personally enlightened individuals.

La théorie du gender: Fast versus slow thinking

In addition to flattening the concept of gender, as if there were uniform consensus regarding its meaning amongst intellectuals and advocates of same-sex marriage, la théorie du gender was described within LMPT and LV circles as a foreign idea forced upon France. By describing the concept as an ‘ideology’ they suggested that gender theory was disseminated through a heteronymous structure of knowledge-production, where the proponents of gender theory were not ‘real’ intellectuals since they expressed ideas that were neither universal, nor autonomously produced (see Sapiro, Citation2009 on types of intellectual interventions). This over-precipitate circulation of knowledge was irresponsible in that a ‘psychiatric’ concept, which supposedly had originated in diagnoses of mental illness, had circulated back into the French school system.

The English word ‘gender’ was pointedly used, directing attention to its putatively foreign provenance (see ). Anti-feminism and anti-Americanism within France have been conjoined for decades, with conservative and left intellectuals claiming at least since the 1970s that ‘American feminism’ is foreign to French norms of gender and sexuality (Ezekiel, Citation1996; Fassin, Citation1999). LMPT and LV activists similarly saw gender as a dogma that had rapidly travelled from American universities into elite French universities and then the highest echelons of power. They articulated a vastly simplified account of the production and circulation of ideas. A university student in his early twenties described la théorie du gender as the idea that ‘A boy can become a girl; and a girl can become a boy. They can just decide in their head […] It came from gender studies in the United States during the 1980s, and now it’s in fashion.’Footnote19

Several French Catholic intellectuals had already criticised gender theory before the emergence of LMPT (Carnac, Citation2014). Tony Anatrella, a Roman Catholic priest and psychoanalyst, edited a book published in 2011 dedicated to the topic. The book opens with a dizzying account of the global circuits which have purportedly forged this ‘new ideology’:

It would take too long to describe the diverse origins of these ideas which first emerged amongst clinicians who treated transsexuals, and American cultural psychoanalysts and linguists who studied language (gender studies) […] It was recycled by Canadian sociologists and reassessed in France by numerous philosophers, before it was rediscovered again in the United States by lesbian movements originating in radical feminism, and then it was adopted by homosexual movements. They made it into a ‘philosophy’ with a scientific appearance for justifying their social claims. Gender theory returned to France transformed (Anatrella Citation2011, p. 5).Footnote20

At first it was a psychiatric idea then used in sociology. People talked about gender identity for transsexuals, because they have a psychological sex which does not match their physiological sex. So then they spoke of ‘gender identity’. But then in sociology, I don’t know when, I think in the 1930s, they started to say there was a ‘feminine gender’ and a ‘masculine gender’. […] And today, with la théorie du gender, there’s a movement called Le Queer, who say: one is not classified as either male or female according to one’s biological sex, but according to one’s sexuality. Homo, hetero – we can mix everything. Male, female, biological sex, transsexuality, they bridge strange categories. And what they want to explain to six-year old children is that, even if you have a penis, you’re not necessarily a boy, you won’t necessarily finish off as a boy. You can choose what you will be. Le gender is actually a psychiatric concept.Footnote21

In the accounts here, the critique of le gender was not only directed towards its putative meaning, but was also criticism of a theory on the loose. Its circulation was viewed as like a virus infecting one discipline to another, from one country to another, and rapidly moving from the psychiatric clinic, across university disciplines, and then to law and public education. The critique thus resided not just in the content of the idea and the homophobic and transphobic implications that homosexuality and transgenderism are, above all, mental illnesses; it also criticised fast versus slow thought. LMPT and LV activists claimed that unlike those supporting le gender, they themselves were moved by ideas that had been tested by time, by slow thinking which was now universal and classic. A protest sign at an LV evening vigil mocked incorporating the concept of gender into the national school curriculum, emphasising instead the value of teaching ‘universal’ knowledge: ‘No to Gender Theory! Grammar and Calculus for All!’Footnote23

These accounts also alleged an authoritarian structure of knowledge-production and circulation, as if the proponents of same-sex marriage and gender theory were thoughtless actors rapidly – and hence unreflectively – following the dictates of a hierarchy from above. This view of gender theory did not recognise, or showed no awareness of, the slow, and sometimes acrimonious, nature of academic debates within and between feminism and Queer theory, the complex relationship between the LGBTQ rights movement and the university, and the similarly complex relationship between social movements, academia, and the law.

By contrast, LMPT and LV conservatives claimed their own ideas to be multi-faceted, to have emerged autonomously from contemplative self-reflection, and to have developed through slow thinking. They discursively distanced themselves from appearing to represent the Church’s will. They also alleged that they had abstained from undemocratically forcing their ideas upon the republic, and were rather engaged in a principled democratic process in which they were often the losers precisely because they acted upon principle and outside any ‘lobby’.

Conclusion

Knowledge politics matter immensely to educated conservatives. They intervene into knowledge politics as moral epistemics, disputing bodies of knowledge perceived as rivaling their own moral ideas, and seek to undermine the social actors and institutions producing knowledge they perceive as rival moral epistemics. Conservative interventions in knowledge politics are therefore not only reflections of formal theology. The broader sociological positioning of conservatives in knowledge hierarchies also shapes conservative activism. It is therefore important to pay attention to the reference groups against whom conservatives see themselves in an antagonistic relationship, the epistemic authorities with which they identify, and the overlapping fields they occupy, to comprehend their interventions and strategies in moral epistemics.

As a contrast to French bourgeois conservatives, for example, American evangelism holds a different relationship to the university, class, and epistemic hierarchies. With a membership base characterised by low levels of higher education (Brint & Abrutyn, Citation2010), and with less importance accorded to the university and to any institutionalised epistemic authority, evangelical conservativism is increasingly dismissive of the university and university-produced knowledge in toto (see Gross, Citation2013; Ecklund, Scheitle, Peifer, & Bolger, Citation2017). This is different from criticism of university-produced knowledge waged by French Catholic conservatives, whose sociological positioning makes them dependent on the status distinction conferred by secular institutions of higher education, while they also place their faith in the epistemic authority of the Catholic Church.

As another point of comparison, and with more similarities to French bourgeois conservatives, Hungary’s right-wing government, which includes a faction of educated conservative Christian Democrats, has recently de-registered ‘Gender Studies’ university degree programmes, but is reforming some university programmes into ‘Family Studies’ degrees. Footnote24 These reforms signify an engagement with universities as authorities that matter in the production of moral epistemics, rather than a complete dismissal of their sociological and epistemic signficiance.

This analysis of LMPT and LV conservatives as actors engaged in moral epistemics holds three implications for further studies of conservatism. The first implication is that, as argued throughout this paper, religious movements are comprised of religious actors who are more than simply religious actors. Religious conservatives are complex sociological beings whose religiosity correlates with other factors such as class, education, and geography, all of which affect if, how, and against whom they engage in debates over knowledge, especially debates over moral epistemics.

Secondly, and as a consequence of the previous point, studies of religious conservatism should not only analyse the discursive and theological content of conservative movements, but should also analyse how conservative groups criticise the circuits of knowledge-production among those they view as antagonistic to their own knowledge-production and dissemination. Conservatives, including anti-gender campaigners, are nested within socially-structured knowledge hierarchies which they are increasingly seeking to subvert through national, and sometimes global, movements.

Finally, while the conservative critique of le gender has emerged as part of a growing movement against gender and sexual equality in Europe (see Paternotte & Kuhar, Citation2017), in Russia too (Stoeckl, Citation2016), and globally, it has also developed in tandem with a broader offensive against the authority of university-based knowledge-production around the world. Opposition to gender theory would benefit from being analysed comparatively to opposition to climate change science, evolutionary theory, medical vaccination research, or bioethics and stem-cell research (see also Verloo, Citation2018). Comprehending religious conservatism as a form of moral epistemics, and understanding where conservatives are sociologically positioned within competing knowledge hierarchies, would be helpful for understanding how epistemological controversies are escaping the university, and are becoming politicised by a broader array of actors in Europe and beyond.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

ORCID

Dorit Geva http://orcid.org/0000-0002-5910-3982

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 The ‘Manif Pour Tous’ translates to ‘Demonstration for All’. Its name was meant as a riposte to ‘Marriage for All’, the popular name for the law recognising same-sex marriage.

2 I interviewed Marion Maréchal-Le Pen at her former political headquarters in Carpentras on July 5, 2013, as part of a project on the French National Front and rightwing politics in France (see Geva, Citation2018). She expressed support for LMPT, but expressed no opposition to le gender at the time.

3 While I strongly disagreed with movement members’ opposition to same-sex marriage and ‘le gender’, I remain grateful to my informants, several of whom spent hours in conversation with me. All interviewees from LMPT and LV have been anonymised.

4 Interviewed April 17, 2013. I use pseudonyms to protect the identity of informants cited in this paper. With one exception, all interviews were conducted in French.

5 Interviewed 13 July 2013.

6 Interviewed 3 July 2013.

7 Interviewed 3 July 2013.

8 In the sense of ‘going bananas’, i.e. someone who is crazy or ‘bonkers’.

9 Interviewed 6 July 2013.

10 On 26 May 2013.

11 Interviewed 7 July 2013.

12 Interviewed 13 May 2013. Most interviews and observations took place in wealthy neighbourhoods.

13 Interviewed 25 June 2013.

14 Interviewed 3 July 2013. Civitas is a movement that contests the separation between Church and State.

15 Interviewed 26 July 2013.

16 Interviewed 3 July 2013.

17 Interviewed 24 June 2013.

18 Interviewed 3 July 2013.

19 Interviewed 25 June 2013.

20 Translation mine. ‘Gender studies’ is written in English in the original French text.

21 Interviewed 13 July 2013.

22 Interviewed 3 July 2013.

23 26 May 2013.

References

- Anatrella, T. (2011). Gender: La Controverse. Paris: Pierre Téqui.

- Ayoub, P. M. (2014). With arms wide shut: Threat perception, norm reception, and mobilized resistance to LGBT Rights. Journal of Human Rights, 13(3), 337–362. doi: 10.1080/14754835.2014.919213

- Barjot, F. (2011). Confessions D’une Catho Branchée. Paris: Broché.

- Béraud, C., & Portier, P. (2015). Métamorphoses Catholiques: Acteurs, Enjeux et Mobilisations depuis le Mariage Pour Tous. Paris: Éditions de la Maison des Sciences de l’Homme.

- Bob, C. (2012). The global right wing and the clash of world politics. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Bourdieu, P. (1992). Distinction: A social critique of the judgment of taste. London: Routledge.

- Bourdieu, P. (1996). The state nobility: Elite schools in the field of power. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

- Bourdieu, P., & Passeron, J.-C. (1964). Les héritiers: Les Étudiants et la Culture. Paris: Éditions de Minuit.

- Bourdieu, P., & Passeron, J.-C. (1970). La Reproduction: Élements Pour une Théorie du Système D’enseignement. Paris: Éditions Minuit.

- Brint, S., & Abrutyn, S. (2010). Who’s right about the right? Comparing competing explanations of the link between white evangelicals and conservative politics in the United States. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 49(2), 328–350. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-5906.2010.01513.x

- Brooks, D. (2000). Bobos in paradise: The new upper class and how they got there. New York: Simone and Schuster.

- Carnac, R. (2014). Les autorités catholiques dans le débat français sur la reconnaissance légale des unions homosexuelles (1992-2013). In M. B. de Lavergnée, & M. D. Sudda (Eds.), Genre et Christianisme: Plaidoyers pour une Histoire Croisée (pp. 375–409). Paris: Beauchesne.

- Carnac, R. (2017). Un Rapprochement Entre ‘Catholiques d’Identité’ et ‘Musulmans d’Identité’? In B. Dumons & F. Gugelot (Eds.), Catholicisme et Identité: Regards Croisés sur le Catholicisme Français Contemporain (pp. 287–302). Paris: Éditions Karthala.

- Chabal, P., & Daloz, J.-P. (2006). Culture troubles: Politics and the interpretation of meaning. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

- Chebel D’Appollonia, A. (1992). L’extrême-Droite en France: De Maurras à Le Pen. Brussels: Complexe.

- De Saint-Martin, M. (2000). Vers une Sociologie des Aristocrates Déclassés. Cahiers d’histoire, 45(4), 785–801.

- Della Sudda, M. (2017). Les Vigiles Debout. In B. Dumons & F. Gugelot (Eds.), Catholicisme et Identité: Regards Croisés sur le Catholicisme Français Contemporain (pp. 251–266). Paris: Éditions Karthala.

- Dumons, B. (2017). ‘Catholicisme de l’identité’: Une Recharge du Catholicisme Intransigent? In B. Dumons, & F. Gugelot (Eds.), Catholicisme et Identité: Regards Croisés sur le Catholicisme Français Contemporain (pp. 11–16). Paris: Éditions Karthala.

- Durand, M. (2017). Une mobilisation ‘contre-nature’? Le cas d’homosexuels opposés au mariage pour tous en France. Genre, Sexualité & Société. [Online], 18(Autumn). doi :10.4000/gss.4069.

- Ecklund, E. H., Scheitle, C. P., Peifer, J., & Bolger, D. (2017). Examining links between religion, evolution views, and climate change skepticism. Environment and Behavior, 49(9), 985–1006. doi: 10.1177/0013916516674246

- Ezekiel, J. (1996). Anti-féminisme et Anti-Américanisme: Un Mariage Politiquement Réussi. Nouvelles Questions Féministes, 17(1), 59–76.

- Fassin, É. (1998). L’illusion Anthropologique: Homosexualité et Filiation. Temoin, 12, 43–56.

- Fassin, É. (1999). The purloined gender: American feminism in a French mirror. French Historical Studies, 22(1), 113–138. doi: 10.2307/286704

- Fetner, T. (2008). How the religious right shaped lesbian and gay activism. Social Movements, Protest and Contention. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Fradois, G. (2017). De la Cure des Âmes à L’évangélisation des Corps. Le CLER Amour et Famille: Classes Dominantes et Morale Sexuelle. Genre, Sexualité & Société. [Online], 18(Autumn), DOI: 10.4000/gss.4062.

- Geva, D. (2018). Daughter, mother, captain: Marine Le Pen, gender, and populism in the French national front. Social Politics: International Studies in Gender, State, & Society. Published online December 24.

- Gross, N. (2013). Why are professors liberal and why do conservatives care? Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Heath, M. (2012). One marriage under god: The campaign to promote marriage in America. New York: New York University Press.

- Kubica, G. (2009). A rainbow flag against the Krakow dragon: Polish responses to the gay and lesbian movement. In L. Kürti, & P. Skalnik (Eds.), Postsocialist Europe: Anthropological perspectives from home (pp. 119–149). New York: Berghahn Books.

- Lamont, M. (1992). Money, morals, and manners. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

- Mallevoüe, D. d. (2012). Mariage Gay: Les Partisans Perdent Le Match de La Rue. Le Figaro, December 16. http://nouveau.europresse.com/Link/ENSLYONT_1/news·20121217·LF·202x20x23712152045.

- Massei, S. (2017). S’engager contre l’enseignement de la « théorie du genre ». Trajectoires sociales et carrières militantes dans les mouvements anti-ABCD de l’égalité. Genre, sexualité & société. [Online] 18(Autumn). doi: 10.4000/gss.4095

- Mayer, S., & Sauer, B. (2017). ‘Gender ideology’ in Austria: Coalitions around an empty signifier. In R. Kuhar & D. Paternotte (Eds.), Anti-gender campaigns in Europe (pp. 23–40). London: Rowman & Littlefield.

- Paternotte, D., & Kuhar, R. (2017). ‘Gender ideology’ in movement: Introduction. In R. Kuhar & D. Paternotte (Eds.), Anti-gender campaigns in Europe (pp. 1–22). London: Rowman & Littlefield.

- Pinçon, M., & Pinçon-Charlot, M. (2005). Voyage en Grande Bourgeoisie. Paris: Presses Universitaires de France.

- Pinçon, M., & Pinçon-Charlot, M. (2007). Sociologie de la Bourgeoisie. Paris: La Découverte.

- Portier, P. (2012). Pluralité et Unité dans le Catholicisme Français. In C. Béraud, F. Gugelot, I. Saint-Martin, & P. Portier (Eds.), Catholicisme en Tensions (pp. 19–36). Paris: Éditions de l’EHESS.

- Portier, P. (2018). Sens Commun: Un Combat Conservateur entre Deux Fronts. Le Débat, 199(2), 105–114. doi: 10.3917/deba.199.0105

- Raison du Cleuziou, Y. (2014). Qui sont les Cathos Aujourd’hui? Paris: Desclée de Brouwer.

- Raison du Cleuziou, Y. (2018). Sens commun: Un combat conservateur entre deux fronts. Le Débat, 199(2), 105–114. doi: 10.3917/deba.199.0105

- Rétif, S. (2017). Défendre la famille et Représenter les Familles: L’engagement au Sein des Associations Familiales Catholiques. In B. Dumons & F. Gugelot (Eds.), Catholicisme et Identité: Regards Croisés sur le Catholicisme Français Contemporain (pp. 155–170). Paris: Éditions Karthala.

- Robcis, C. (2013). The law of kinship: Anthropology, psychoanalysis, and the family in twentieth-century France. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

- Sandel, M. J. (1996). Democracy’s discontent: American in search of a public philosophy. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Sapiro, G. (2009). Modèles D’intervention Politique des Intellectuels: Le Cas Français. Actes de la Recherche en Sciences Sociales, 176-177(1), 8–31. doi: 10.3917/arss.176.0008

- Smith, A. M. (1994). New right discourse on race and sexuality: Britain, 1968–1990. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Stambolis-Ruhstorfer, M., & Tricou, J. (2017). Resisting ‘gender theory’ in France: A fulcrum for religion action in a secular society. In R. Kuhar, & D. Paternotte (Eds.), Anti-gender campaigns in Europe (pp. 79–98). London and New York: Rowman & Littlefield.

- Stoeckl, K. (2016). Transnational learning in anti-gender mobilization in Europe. Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the Social Science History Association, Chicago, IL, November 2016.

- Verloo, M. (2018). Gender knowledge, and opposition to the feminist project: Extreme-right populist parties in the Netherlands. Politics and Governance, 6(3), 20–30. doi: 10.17645/pag.v6i3.1456

- Warner, T. (2010). Losing control: Canada’s social conservatives in the age of Rights. Toronto: Between the Lines.