ABSTRACT

The majority of countries in the world have laws setting the minimum age of marriage at 18 years old. This is a global legislative trend that intensified greatly in the 1990s. What explains this trend? To answer this question, I conduct quantitative analyses of factors influencing legislation setting the minimum age of marriage at 18. I analyse time-series data for 167 countries from 1965 to 2015 to examine which countries were early adopters of legislation. Drawing on world society theory, I theorise that global level institutionalisation of norms concerning women and children is the key to understand the passing of minimum age of marriage laws. Findings indicate that world cultural scripts and the presence of women legislators are the main impetus behind the fight against child marriage. Countries with a Muslim majority are less likely to pass laws setting the minimum age of marriage at 18.

Introduction

In September 2013, the United Nations Human Rights Council and General Assembly adopted a resolution dedicated to child, early, and forced marriage. This is the first resolution to explicitly and exclusively address the issue. The resolution recognises child, early, and forced marriage as a human rights and development issue and declares that ‘it constitutes a violation, abuse or impairment of human rights, that it prevents individuals from living their lives free from all forms of violence and that it has adverse consequences on the enjoyment of human rights, such as the right to education, the right to the highest attainable standard of health, including sexual and reproductive health’ (UNHRC, Citation2013).

It was not until the 1960s that states started to pass marriage laws setting the minimum age at 18, the presumed age of adulthood. In the 1990s, this has become a global legislative trend. In addition to this trend, child marriage became a focus of concern for many international non-governmental organisations (INGOs) and multilateral organisations. The movement against child marriage received a great deal of global attention particularly after mid-2000s. The years between 2004 and 2010 witnessed the emergence of girls as the new agents and objects of international development. With the launching of the International Day of the Girl in 2012 by the UN, and Malala Yousafzai’s selection at the age of 17 as the Nobel Peace Prize winner in 2014, it would not be an exaggeration to say that adolescent girls have become the most important element of international development. From the very beginning, campaigns on behalf of adolescent girls mentioned child marriage as an impediment to development goals.

As a response to the movement, legislation against child marriage continues to feature on the agenda of governments around the world (for a complete list of countries and years of legislation see Appendix 1). In June 2017, two countries passed laws regarding child marriage: Germany passed a new law that makes the marriage age strictly 18, without exceptions (The Local, Citation2017) while the Dominican Republic voted for a similar law (Plan International, Citation2017). Malawi is another country that raised the minimum age of marriage to 18 recently, in April 2017 (Girls Not Brides, Citation2017a). Despite their differences, these three countries are taking or discussing legislative steps in the same direction, to reduce child marriage.

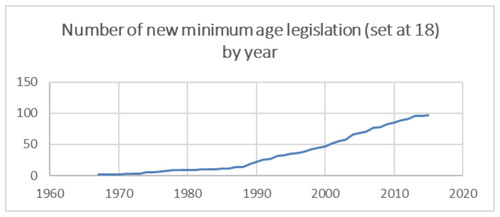

What explains this global legislative shift that started haltingly in the 1960s and 1970s and intensified greatly in the 1990s? (see ) Which countries are faster to adopt minimum age of marriage legislation? These are the major research questions addressed in this paper. I draw upon event history analyses of 167 countries from 1965 to 2015 and examine what factors help explain which countries were early adopters of minimum age of marriage legislation.

Construction of child marriage as a global problem – the role of international organisations

In the international arena, marriage is mentioned for the first-time in 1948 with the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (United Nations, Citation1948). The UDHR defines an ideal marriage with respect to age, presence of full consent, and equality within marriage. In international law the issue of child marriage was first addressed in the 1962 Convention on Consent to Marriage, Minimum Age for Marriage and Registration of Marriages (hereafter: 1962 Convention). The 1962 Convention appeals to all member states to take measures to abolish ‘certain’ customs regarding marriage, to open the way for ‘complete freedom in the choice of a spouse’ and ‘eliminating completely child marriages and the betrothal of young girls before the age of puberty’ (United Nations, Citation1962). The 1965 Recommendation on Consent to Marriage, Minimum Age for Marriage and Registration of Marriages, which was a non-binding recommendation that accompanied the 1962 Convention, specified the minimum age recommendation and declared that the ‘age of marriage should be no less than 15 years unless a competent authority agrees that there are serious reasons to provide otherwise’. Although the 1962 Convention was an important treaty, as it is the first that addresses the issue, it was signed by only 16 countries, most of which expressed reservations (United Nations, Citation1962).

The second crucial international treaty concerning child marriage was the 1979 Convention for the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW). With CEDAW, child marriage started to be defined as a human rights and gender equality problem. CEDAW provides that the ‘betrothal and the marriage of a child shall have no legal effect, and all necessary action, including legislation, shall be taken to specify a minimum age for marriage and to make the registration of marriages in an official registry compulsory’ (United Nations, Citation1979). With CEDAW, for the first time in an international document the minimum age of marriage was recommended to be 18. Moreover, CEDAW urged states to legislate against child marriage by prohibiting it.

International treaties not only suggest ways to prevent child marriage, but they also promote an ideal form of marriage. The UDHR defines an ideal marriage with respect to age (‘men and women of full age’), the presence of ‘full and free consent of the intending spouses’, and presence of equal rights ‘as to marriage, during marriage and at its dissolution’ (UDHR, Article 16). Following the UDHR, the 1962 Marriage Convention reiterates that ‘men and women of full age, without any limitation due to race, nationality or religion, have the right to marry and to found a family’ and ‘free and full consent of the intending spouses’ should be present (United Nations, Citation1962). In addition to the UDHR, the 1962 Convention urges states to commit themselves to ‘take legislative action to specify a minimum age for marriage’. The Convention says that certain customs, laws and practices are inconsistent with the UDHR and states should abolish them by ensuring ‘complete freedom in the choice of a spouse, eliminating completely child marriages and the betrothal of young girls before the age of puberty’. The 1962 Convention signifies the characteristics of the normative marriage: free consent of both parties and maturity. It was a big step toward institutionalising the notion of the freely consenting individual, unconstrained by familial or other demands. Although contested, such notions of marriage are now world-cultural: they ‘present themselves as generally applicable and meaningful throughout the world’ (Boli, Citation2005, p. 385).

A global civil society mobilisation against child marriage began in the early 1990s within the context of the international women’s movement following the 1995 Fourth World Conference on Women (Beijing Platform). Unlike the second wave of civil society mobilisation in the 2000s, this first wave did not explicitly focus on child marriage itself. Rather, it was a part of the international mobilisation of women’s rights and opening up of international organisations such as the UN to women’s rights advocacy in unprecedented ways. Even though, child marriage was not their exclusive agenda, as a result of this high-level international mobilisation, rights of women and girls became an indispensable part of international development and global agenda-setting.

Within the context of 1990s, child marriage was discussed as a human rights issue with respect to its negative outcomes in terms of gender equality, women’s health, decision-making capabilities, risk of domestic violence, and educational opportunities. In addition to being a gender equality issue, the children’s rights approach which defines children as subjects bearing rights and in need of protection is another perspective from which the international community has considered the problem of child marriage. With the global institutionalisation of children’s rights (Boyle, Citation2007) and the emergence of the 1989 United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (hereafter CRC), the issue came to be seen not only about gender but also about children’s rights. In other words, with the CRC a certain definition of childhood is culturally institutionalised and became legitimate in the global realm. This opened a new way to depict child marriage as a problematic practice. Even though the CRC does not have any explicit references to the issue of child marriage, after the second half of 1990s the CRC is frequently referred to in campaigns against child marriage, notably its articles on abolishing sexual abuse and sexual exploitation (United Nations, Citation1989). The CRC is an embodiment of an idealised version of childhood in which marriage does not have a place. After 1990s, the international community emphasised the fact that marriage happens to children and robs them of a normal childhood. The development community frames child marriage as an agency-depriving practice which ‘robs girls of their ability to reach their full potential’ (Mathur, Greene, & Malhotra, Citation2003, p. 4). Not only can girls not resist their families’ decisions since they are not autonomous, but because they get married when they are children, they experience further difficulties in becoming autonomous individuals.

Accordingly, one of the reasons child marriage should be eliminated is that it is an impediment to an ideal childhood through which an ideal individual is created. In that sense, child marriage interrupts the ideal life course of the individual. Hence, the construction of child marriage as a global problem is closely related to global cultural conceptions of the individual, an idealised version of childhood, and growing awareness of the need for gender equality. Individual rights (i.e. human rights), children’s rights, and women’s rights are pervasive global scripts with policy outcomes. This does not mean that there is no contestation over those but overall these are issues of low-contestation and high convergence.

The exclusive advocacy of INGOs for minimum age of marriage legislation started in the second half of 1990s. Following the advocacy efforts, scholars also started to examine the issue of child marriage with respect to its harmful effects. A great majority of studies have been conducted by public health researchers and child marriage is used mainly as an independent variable. These studies examine the effect of child marriage on fertility (Raj, Saggurti, Balaiah, & Silverman, Citation2009), women’s reproductive health (Kamal & Hassan, Citation2015), infant health (Raj, Citation2010), mental health (Le Strat, Dubertret, & Le Foll, Citation2011), HIV rates (Bruce, Citation2005; Raj & Boehmer, Citation2013), educational attainment (Nguyen & Wodon, Citation2012; Raj, McDougal, Silverman, & Rusch, Citation2014), rates of violence against women (Speizer & Pearson, Citation2011), and economic development (Parsons et al., Citation2015). In all these studies, findings indicate negative effects of child marriage in different spheres of society.

The first concentrated international advocacy effort was put forward by the Forum on Marriage and the Rights of Women and Girls. The Forum was established in 1998 and is a network of UK-based NGOs, Human Rights Watch, Oxfam, UNICEF, and the ILO. It was effective in bringing the issue to the attention of the UN. In return, for the first time, UNICEF published a report on law and marriage around the world and supported local NGOs working on the issue.

The second wave of mobilisation by INGOs that pushes the legislation forward came in the second half of 2000s with the foundation of Girls not Brides in 2008. Girls not Brides is a civil society partnership that consists of 1300 organisations in 100 countries. Following the foundation of Girls not Brides, INGOs pushed the UN for understanding the current status of marriage legislation globally. As a result, in 2013, the OHCHR sent out a questionnaire to NGOs, states, and consultants around the world to collect information on the law as well as its implementations. Many local NGOs as well as INGOs sent out reports summarising the current state of affairs in their geographical area and came up with an action plan. Starting from the second half of the 2000s, these action plans came to be discussed under the leadership of Girls not Brides and strengthened the global character of the movement. Civil society partnerships such as the Girls not Brides have been effective in creating awareness to the status of minimum age of marriage laws and through its leadership NGOs all over the world share their experiences with each other on what works to push the governments for marriage age legislation. As such, INGOs are effective in bringing the issue to the attention of key international organisations such as the UN.

Global influences on minimum age of marriage legislation

Studies focusing on legislation against child marriage or minimum age of marriage laws examine the interplay between international norms and domestic politics. For instance, Toyo (Citation2006) discusses this issue with respect to the Nigerian Child Rights Act (CRA) of 2003. The CRA set the minimum age at 18 but the Nigerian Constitution does not establish a minimum age of marriage. Toyo argues that critics framed the CRA as emanating ‘not from national but from the international arena’ and it was an ‘invasion of what is basically a private sphere’ (1302). Both Moschetti (Citation2005) and Desai and Andrist (Citation2010) argue that age of marriage laws is an important arena of collision between colonial ideology and nationalist Indian ideology. Other scholars focus on the effect of minimum age of marriage laws on actual child marriage rates. Cammack, Young, and Heaton (Citation1996) found that marriage age laws have had no effect on the actual rates of child marriage in Indonesia. Momeni (Citation1972) reached similar conclusions in his study focusing on Iran. More recently Lee-Rife, Malhotra, Warner, and Glinski (Citation2012) also found that the Indonesian Marriage Act of 1974 did not lead to significant changes in the trends of child marriage. One of the most comprehensive descriptive studies of child marriage legislation is that by the World Health Organisation (WHO) and the Inter-Parliamentary Union in 2015. This study reviewed current legislation against child marriage in 37 Asia-Pacific Countries and concluded that child marriage rates remained high even in the presence of strong legislative measures against it (Scolaro et al., Citation2015).

None of the sources mentioned above examined the legislation against child marriage in a global level or asked how and why the legal minimum age of marriage is increasing globally. These questions entail a macro-level comparative approach both theoretically and methodologically.

I rely mainly on world society theory to generate explanatory hypotheses on passing marriage age legislation. For world society theory (hereafter WST), states passing laws in accordance with pervasive global scripts are not coincidental. WST assumes that worldwide cultural and associational processes are the main mechanisms that constitute actors and action (Boli & Thomas, Citation1999). In this model, world culture refers to the:

culture of world society, comprising norms and knowledge shared across state boundaries, rooted in nineteenth century Western culture but since globalised, promoted by nongovernmental organisations as well as for-profit corporations, intimately tied to the rationalisation of institutions, enacted on particular occasions that generate global awareness, carried by the infrastructure of world society, spurred by market forces, riven by tension and contradiction, and expressed in the multiple ways particular groups relate to universal ideas. (Lechner & Boli, Citation2005, p. 6)

WST assumes the structural dominance of a rationalised, global institutional and cultural order in which all other units, such as nation-states, organisations and individuals, are embedded. In terms of the decision-making processes of nation states, it highlights the world-cultural principles upon which the world cultural order is founded. Nation-states around the world have similar structures and implement similar models of development, health or education because they conform to ‘dominant, legitimated or taken-for-granted views’ resulting from world culture (Schofer, Hironaka, Frank, & Longhofer, Citation2012). WST scholars count ‘rationalisation, universalism, belief in progress and individualism’ as crucial cultural assumptions of the world polity (ibid). These cultural principles are institutionalised as normative rules in the world polity. For WST, actors do not act so much as enact these cultural models.

Unlike the rational-actor assumptions of the majority of sociological theories of globalisation, WST emphasises culture and norms as constitutive of action. For WST, states or individuals do not always make decisions on the basis of what is rational or what is functional; rather, they conform to dominant frames of reference. One of the most important reasons for this conformity is the concern to be seen as being legitimate in the eyes of others. This applies to actors at various levels and includes individuals as well as nation-states. Employing a WST perspective, I see the trend of increasing the minimum age of marriage as a reflection of the principles of the global cultural order. With its emphasis on conformity in global policy-making as a result of being exposed to certain global norms, the WST perspective is useful for understanding the global pattern of raising the legal marriage age.

It is not a coincidence that the first time the international community moved toward institutionalisation of the ideal marriage came after World War II. Although the international community was certainly operative earlier in the form of international organisations, both IGOs and INGOs, it was not until after the war that they were globally institutionalised. A centralised global governance structure emerged in the form of the United Nations, to which existing global civil society organisations attached themselves (Boli & Thomas, Citation1999). These organisations, especially INGOs, are the ‘structural backbone’ of world culture through which world cultural ideas, principles and norms are debated and expanded. Even though world cultural ideas about what an ideal marriage is and why other forms may be particularly problematic for women started to spread well before the 1950s, especially within some feminist circles (Moschetti, Citation2005), those ideas did not find fertile ground in which to grow, but eventually they proliferated and were translated into rationalised prescriptions for the conditions of the ideal marriage and arguments about the negative causes and consequences of non-ideal forms. With the increasing institutionalisation of the individual at the level of world society, marriages not based on freely given consent by competent adults became problematic and illegitimate. It was not only international civil society that developed a definite position against child marriage: constituted by similar cultural principles, nation-states also started to enact laws against child marriage in this period.

According to WST, in a world where a global state that would enforce world cultural norms and models does not exist, INGOs play a highly significant role. Indeed, world-cultural models are embodied in and sustained by INGOs. In addition to INGOs, global interstate agreements also embody world cultural principles. Thus if a country is subject to many global agreements and heavily involved with INGOs, it would be considered relatively highly integrated into the world polity. As a country is more integrated into the world polity, it will enact more world-cultural principles that are typically institutionalised in international non-governmental organisations and IGOs. In the case of child/forced marriage, the global trend is toward increasing the marriage age, due to global cultural norms of individualism and sacralisation of women and children. Following this, I hypothesise that the world-polity embeddedness of a country is predictive of its legislation regarding the minimum marriage age requirement.

Hypothesis 1: The greater the embeddedness in the world polity, the higher the likelihood of passing legislation setting the minimum age of marriage at 18.

In addition to the influence of INGOs in general, membership in women’s INGOs that work on the issue of child/forced marriage is particularly important. Where local norms are shifting more to emphasise the negative effects of child marriage, involvement with women’s INGOs will be higher. Following this, I hypothesise that women’s INGOs’ efforts are central for the state’s legislative reforms against child/forced marriage.

Hypothesis 2: The greater the involvement with women’s INGOs, the higher the likelihood of passing legislation setting the minimum age of marriage at 18.

Finally, the ratification of certain international human rights instruments is an important factor contributing to legislative changes. Human rights instruments such as conventions and resolutions have norm-setting power and should be predictive of legislative reforms. International human rights instruments are important because ratifying them indicates adhesion to global legitimations of the individual and individual rights. For the issue of child marriage, treaties and conventions on women and children are particularly important. I hypothesise that if a country ratifies more treaties on children and women then it is more likely to have stricter marriage age laws.

Hypothesis 3: The more relevant conventions ratified, the higher the likelihood of passing legislation setting the minimum age of marriage at 18.

Advocating women’s rights and child marriage – the role of women politicians

The relationship between women’s presence in the parliament and the representation of women’s interests is widely explored by political scientists. Anne Phillips’ book, The Politics of Presence (Citation1995), suggests that women’s interests can best be represented by women politicians. The main assumption behind this is that women share similar life experiences and can anticipate each other’s needs best. She claims that women’s and men’s experiences are different in the labor market, education, exposure to violence, and child-rearing responsibilities, among others, so only women politicians can and will address women’s issues. Other scholars reached similar conclusions. To name a few, Kittilson (Citation2008) found that between 1970 and 2000, in 19 democracies, women’s presence in parliament increases the adoption of maternity and child care leave policies. Swers (Citation1998) study on congressional voting in the United States yields similar results particularly with respect to abortion and women’s health policies. Other case studies and comparative studies on representation of women’s interests by women reach similar results (Celis, 2006; Schwindt-Bayer & Mishler, Citation2005; Thomas, Citation1991) with a few exceptions (Burnet, Citation2008; Devlin & Elgie, Citation2008).

The laws against child marriage can arguably be seen as laws promoting gender equality and therefore strengthening women’s interests. There are many cases where female parliamentarians either initiated the public debates about child marriage or strongly supported the case of non-state actors about it. Following this and the literature on the effects of female parliamentarians, I hypothesise as follows:

Hypothesis 4: The greater the representation of women in the legislature, the more likely the state will pass legislation setting the minimum age of marriage at 18.

Data and methods

Dependent variable

This variable indicates whether or not a country has legislation setting the minimum age of marriage at 18 in a given year. Given the problems with an ordinal version of the variable,Footnote1 I created a dummy variable with just two values. The variable is coded 1 if a country has a law that sets the marriage age at 18, with or without exceptions, and 0 if the marriage age is below 18 (for either or both sexes) or a minimum age of marriage is absent. Thus I combine ‘strictly 18’ and ‘18 with exceptions’ into one category and all other cases into another. Although, ‘18 with exceptions’ is not the global standard, it is still a move toward it. The second category, on the other hand, clearly violates the international standard. Since I seek to explain the global trend toward increasing the marriage age to the international standard of 18 years old, this categorisation is appropriate.Footnote2 Kim, Longhofer, Boyle, and Nyseth (Citation2013) coded marriage age laws for non-OECD countries until the year 2011. As an addition to their data, I coded the OECD countries and extended the data set to 2015. To code the years after 2011, I predominantly used Girls not Brides’ webpage in which information on any development on child marriage (including legislative changes) can be found, country by country (Girls not Brides, Citation2017b). In most cases, the country profiles provide information on the latest legislative changes. In some cases, I used the links to relevant reports provided in country profiles. For 37 Asia-Pacific countries, I used the 2016 report, ‘Child, Early and Forced Marriage Legislation in 37 Asia-Pacific countries’ by the Inter-Parliamentary Union (IPU) and World Health Organisation (WHO) (WHO, Citation2016). For African countries, I used The African Child Policy Forum’s report on marriage age laws in Africa (ACPF, Citation2013). I also used the World Law Guide (Lexadin) and World Policy Center data (World Policy Center, Citation2017). If contradictory information emerged, I consulted CRC and CEDAW country reports.Footnote3

For OECD countries, I used the CRC and CEDAW country reports, the Council of Europe Family Policy Database, and a report by the Policy Department (Citizens’ Rights and Constitutional Affairs) to the European Parliament (Psaila et al., 2016).

Independent variables

summarises the sources of data for independent variables and controls. Below I discuss the operationalisation for each.

Table 1. Measurements and sources of independent and control variables.

Embeddedness in the world polity

Following WST scholars, I use INGO memberships to measure the degree of embeddedness or integration into the world polity. While far from ideal, this measure of the breadth of INGO memberships (the number of INGOs to which residents of each country belong) has become the standard measure for this concept. The INGO data comes from the Yearbook of International Organisations (2005 and 2013). The data for 1968–2005 are from Mathias (Citation2013), for 2005–2012 from Amahazion (Citation2016). I extrapolated the data for 2012–2015. The variable is logged to reduce skewness.

Involvement with women’s INGOs

In addition to general INGO memberships, this variable considers INGOs specifically working on women’s issues. It follows the same logic: INGOs working on women’s issues carry global norms regarding women and more involvement with these organisations increases adoption of these norms. I measure involvement with women’s INGOs by the number of INGOs about and for women to which each country’s residents belong. The data is derived from a random sample of 25 organisations, stratified by founding date, covering the period 1965–2005 (Frank & Mceneaney, Citation1999). I extrapolated the data to extend coverage to 2015.

Ratification of international treaties

According to world society theory, international human rights instruments represent world cultural principles and their ratification strengthens the legitimacy of those principles. Here I focus on the ratification of treaties dealing with children and women. Three international treaties are particularly important: the Marriage Convention (1962), The Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (1979), and the Convention on the Rights of the Child (1989). I add two protocols to the original conventions as they are related to child marriage. The first is the ‘Optional Protocol to the Convention on the Rights of the Child on the sale of children, child prostitution and child pornography’ (2000). The second protocol is the Optional Protocol to CEDAW (1999), which facilitates enforcement of the original convention by opening the way to individual complaints about rights violations and specifying procedures for investigating such complaints.

I coded this data to indicate the total number of these treaties and protocols ratified by each country in a given year from 1965 to 2015. The data is available from the UN Treaties website (UN Treaties, Citation2017). In addition to the total number of relevant ratifications, I created separate variables for the 1962 Marriage Convention, the CRC and CEDAW to examine their individual effects on the likelihood and rapidness of passing legislation setting the minimum marriage age at 18.

Female empowerment

I measure female empowerment by the proportion of seats held by women in national parliaments. The literature shows that the presence of females in politics is a telling indicator of the strength of women’s rights in a country (Phillips, Citation1995; Wängnerud, Citation2009). Data for this measure is available from the Interuniversity Consortium for Political and Social Research for 1965–2015 (ICPRS), Women in Parliament, 1945–2003: Cross-National Dataset (Paxton et al., Citation2008).

Controls

GDP per capita

GDP per capita is considered important for child marriage legislation because higher rates of child marriage are correlated with higher rates of poverty, as marrying girls off may be the only viable option for poor families (Nguyen and Wodon, Citation2015). Thus less wealthy countries may be less willing to pass legislation against child marriage. Conversely, lowering child marriage rates is now considered a way to facilitate economic development. Thus, less wealthy countries may be more willing to pass minimum-18 age of marriage legislation to increase their economic growth. For this indicator, I use World Development Indicators data (2017) measured as current US dollars. The variable is logged to reduce skewness.

Religion

Religion is a major element that shapes cultural systems, and it often plays an influential role, directly or indirectly, in policy making. Religious bodies often regulate familial, marital, and nuptial relations, and religion is a major factor underlying attitudes about gender relations. Depending on the dominant religious practices or beliefs, religion can thus be strongly predictive of a society’s gender ideology, and its view of marriage and the family. Accordingly, it is reasonable to consider religion as a potential factor in policies concerning child marriage. Using the Teorell et al data set (2011), I code countries as Catholic, Protestant, or Muslim. The coding applies if more than 50% of the population is a member of one of the three religions. The data set does not specify a religious identity if no one religion accounts for more than 50% of the population. I supplemented this data with information from national bureaus of statistics and the CIA Fact Book (2012) to code the remaining cases as ‘Other Christian’ or ‘Other Religion.’

State capacity

Child/forced marriages are mostly unregistered, in part because child marriage is illegal but also because many states do not have effective bureaucratic structures to register them. In the absence of effective bureaucratic functionality, states cannot keep track of births and marriages. If a state lacks information about the prevalence of child/forced marriage in its territory, then it is unlikely that it will identify child marriage as a problem and develop effective legislation against it. On the basis of this assumption, I control for state capacity. Following Boyle et al. (Citation2016), I include government spending as a proportion of GDP as an indicator of the capacity of the government.

Analysis

To analyse when countries adopt minimum age of marriage legislation, I employ survival analysis, also known as event-history analysis. Survival analysis is a statistical technique that is used when the dependent variable is the occurrence of an event or ‘likelihood of occurrence of an event’ (Allison, Citation1984). In this study, the event in question is the enactment of a law setting the marriage age at 18, with or without exceptions. Survival analysis captures a crucial aspect of longitudinal data that linear regression cannot analyse: the factors that lead to early or late adoption of the event. The event in question usually refers to a qualitative change that occurs at a specific point in time (Allison, Citation1984, p. 9). Survival analysis allows for descriptive and parametric analysis of data. The former describes the overall rate an event, in this case the legislation setting the minimum age of marriage at 18. The latter, allows for hypothesis testing about the variables that have an impact on the event. Events may occur just one time or they may recur. In my study, since marriage age legislation only pass once (it does not go back to its earlier version once it is passed). I use a discrete-time-method (ibid 16), Cox Proportional Hazards Model, to determine the impact of independent variables on the hazard rate of passing the legislation over time (Cox, Citation1972).

In survival analysis, the risk-set consists of all countries that have not passed laws setting the minimum age of marriage at 18 after the year 1965. Countries that had already passed such laws are excluded from the analysis as their ‘risk’ of passing the law is always 0 (no country that with a minimum-18 law has ever reverted to a younger marriage age law).

The survival analysis examines 135 countries for the period 1965–2015. It excludes countries that had passed minimum-18 marriage age legislation prior to 1965 as they were not ‘at-risk’ of passing such legislation thereafter. I could not begin the analysis before 1965 due to lack of data for many variables; thus I do not account for the 19 earliest adopters of what would eventually become the global norm. However, my period covers most of the legislation; the survival models analyse 85 failure events (where ‘failure’ means passing the legislation) between 1965 and 2015.

Except for the early legislators, each country’s ‘risk’ of passing the legislation starts the year the country enters the data set. For most of the countries this year is 1965, but some enter later at the time of independence. I use the Cox Proportional Hazards model, which predicts the effects of independent variables on the passage of legislation over time.Footnote4 The dependent variable in the survival analysis is the legislation’s timing, or the rate of event occurrence (Allison, Citation2010, p. 413). The analysis tells us which variables affect how early a country passed the legislation (or failed to do so). The hazard rate (the rate of event occurrence) is then the probability that a country would pass the minimum age of marriage legislation at time t. The year when the marriage legislation passed is coded 1, while the years before and after are coded 0. No country that has passed minimum-18 legislation has ever reverted to a law setting a minimum age below 18 (with or without exceptions). Thus, my dataset is organised as a ‘single-failure-per-subject’ situation; once the legislation has been passed, a country is no longer in the risk-set.

Findings

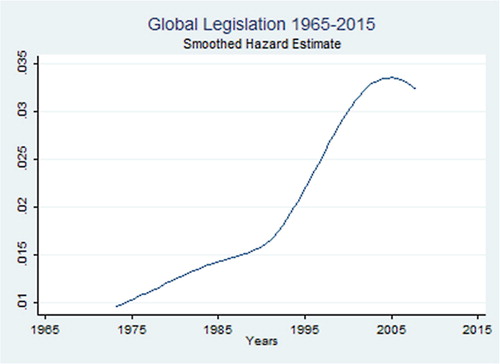

shows that the hazard rate increased steadily over time and started to decrease toward the end (the early 2000s), by which time most of the countries had passed minimum-18 legislation. As of 1965, only 19 countries had passed minimum age of marriage laws that set the age at 18; by 2015, 110 countries had passed such legislation. Between 1975 and 1985, there were only a few countries that passed legislation. However, after 1990 the number of new legislative acts started to increase significantly.Footnote5 This supports my hypothesis that states started to pass legislation only after child marriage was institutionalised as a global issue with conventions, particularly the CRC in 1989.

Figure 2. Smoothed Hazard Estimate: Minimum age of 18 legislation (135 Countries that had passed minimum age legislation after 1965).

presents the Cox regression results. Models 1–5 include world society variables while the last two models test for the female representation hypothesis along with controls. I also test for different conventions (Marriage Convention, the CEDAW, the CRC) in different models and in those models the cumulative treat ratification variable is excluded. Similarly, I also tested for membership in women INGOs in some models in which the general INGO variable is excluded as these are highly correlated.

Table 2. Survival analysis models: Estimates of coefficients impacting global legislation (1965–2015).

My first hypothesis suggested that embeddedness in the world polity would result in a higher likelihood of passing the minimum age 18 legislation. Embeddedness, measured as membership in INGOs, does not seem to be an important factor in predicting adoption of legislation. Similarly, membership in women INGOs hypothesis is not supported. From world society perspective this is surprising as previous research found strong embeddedness as a strong predictive factor of policy adoption in issues such as abolishment of death penalty (Matthias, Citation2013), organ trafficking (Amahazion, Citation2016), rape laws (Frank, Citation2000) among others. As an exception to other world society research, Brehm and Boyle’s (Citation2018) study on adoption of policies banning corporal punishment in schools and homes also reported lack of association between embeddedness and policy adoption. They suggest that INGO networks may have lost importance as different global civil society networks are formed. This line of explanation also works for my case. The advocacy against child marriage is not limited to INGOs, but include a wide array of actors.

Another explanation for the missing INGO effect may be the somewhat diffident language of INGOs, particularly international women’s organisations about child marriage. Although starting from the late 1990s, international women’s organisations became more vocal about child marriage, in the period before the CEDAW and CRC it was almost a taboo subject. Moschetti (Citation2005) discusses the history of the international feminist movement’s involvement with child marriage. She mainly discusses the interwar period, when a small number of British and Indian feminists problematised child marriage as a form of sexual slavery and a form of control of female body. Moschetti argues that those feminists were marginalised; the majority of feminists did not take up the issue. The post-1950s period was also not supportive of those concerned about child marriage. Only after child marriage is conceptualised as a children’s issue as opposed to women’s issue and after its connection with HIV/AIDS and economic development is established, more INGOs took the issue as a part of their advocacy campaigns. This suggests that the INGO effect on the legislation against child marriage is a relatively novel phenomenon, mainly starting from late 1990s on.Footnote6

A final explanation of the lack of INGO effect is that after late 1990s child marriage became such a compelling issue that everyone decided to jump on the bandwagon except countries with a Muslim majority as I discuss below. In other words, since the legislation trend was so pervasive, INGO membership became an insignificant factor to differentiate legislators and non-legislators.

Unlike the embeddedness, another variable that suggests the relevance of global factors in explaining the policy adoption, namely the treaty ratification is significant across all models. This confirms hypothesis 3. What this suggests is that more treaty ratifications lead to earlier passage of age-18 marriage legislation. I also checked for the relevance of different treaties in two models (Model 2 and Model 6). I estimated the analysis for the CRC, CEDAW, and Marriage Convention but exclude the optional protocols to the CRC and the CEDAW because they came so late in the period. Both of these models demonstrated the particularly strong effect of the CRC in predicting the policy adoption. This is in line with my theorising above, as child marriage is conceptualised as an issue concerning children in the global level, states are more willing to pass legislation against it. Returning to the basic smoothed hazard estimate in , the inflection point at the time of the CRC was like a starting gun for legislation. After a warm-up period in previous decades, during which a small proportion of countries passed age-18 laws, the race was suddenly on, and countries ever more eagerly joined in the race to conform to the emergent global norm.

It is worth noting that the establishment of CEDAW does not appear to have much significance compared to the CRC; no inflection point is apparent in Figure 6 in the late 1970s. This shows that the issue of marriage age is defined as a children’s rights issue rather than a women’s issue. The international community conceptualises the issue within the confines of children’s rights, which is reflected in the preferred terminology: starting in the late 1990s, the term ‘child marriage’ came to the fore while ‘early marriage’ and ‘forced marriage’ faded into the background. Footnote7

Hypothesis 4 suggests that female presence in the parliament leads to earlier adoption of minimum age-18 legislation. This hypothesis is consistently supported across models. This is in line with existing research which suggests that proportion of women in parliaments is correlated with positive policy outcomes for women and children. In the case of child marriage, the effect of women may be working in different ways. They may be the ones that initiate change about child marriage or they may be responding to demands for change from civil society groups. It is also possible women parliamentarians that are proactive about child marriage are part of a global network that prioritises the issue. One can think of recent examples such as Zimbabwe’s Jessie Majome, a female parliamentarian, whose efforts ended up the abolition of child marriage by the Constitutional Court of Zimbabwe in 2016. Majome is a member of Parliamentarians for Global Action (PGA), an international network of parliamentarians working on human rights, international justice, equality, and security issues (PGA, Citation2018). PGA actively works to mobilise parliamentarians around the world against child marriage. In 2014, they launched the ‘PGA’s Parliamentary Campaign to End Child Marriage’ and in 2015 presented a declaration in the UN General Assembly which was signed by 729 parliamentarians in 77 countries. By 2017, PGA member legislators contributed to reforms about child marriage in several countries including Ghana, Costa Rica, Dominican Republic, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, and Trinidad & Tobago (PGA, Citation2018).

Parliamentarians also built regional networks through which laws about child marriage are discussed.Footnote8 In 2016, The Southern African Development Community Parliamentary Forum adopted the Model Law on Eradicating Child Marriage while Asian Forum on Parliamentarians on Population and Development brought together parliamentarians of 13 South Asian countries to discuss laws and policies about child marriage in March 2016. In both events, a great majority of participants were women.

The mobilisation around PGA is illustrative of how national legislative reforms are mobilised by international networks. Therefore, consistent positive effect of female presence in the parliament in policy adoption can also be interpreted in relation to global factors. Global norms empower organisations working on women’s and children’s issues, women become more influential in national political processes, and anti-child marriage policies are thereby promoted. The opposite can also be true: a global standard about child marriage did not become fully codified until after regional networks of women parliament started to push for it.

Two control variables, religion and state capacity are significant in explaining child marriage legislation. For religion, Muslim countries are less likely to have passed legislation, and the effect is often but not always significant. This finding is particularly interesting when considered in the context of the rise of political Islam in the second half of 1990s (Roy Citation2006; Tibi Citation2014). Political Islam posits itself as a cultural alternative to the dominant global culture. In that sense, globally institutionalised notions of childhood, marriage or women’s empowerment are either rejected or included selectively. Recent challenges against setting the marriage age at 18 in countries with Muslim majorities are examples of the relationship between political Islam and child marriage. Debates over lowering the marriage age in Egypt in 2012 (Khayri, Citation2012); the shift from strict marriage age laws to looser laws in Bangladesh (Guha, Citation2017), and Turkish government’s efforts to legitimise child marriage in case of rape (Agerholm, Citation2016) are some instances of the contested position of child marriage laws in Islamic contexts. As such, the issue of child marriage becomes a part of the cultural war fought through women bodies.

Finally, the state capacity variable reaches significance in five out of seven models with positive effects. This is suggestive of the fact that relative size and capacity of the government matters in passing the legislation relatively quick. This is probably because as the state capacity increases, it extends its reach to more spheres of life, such as that of marriage and becomes more regulative in capacity. States with greater capacity may be inclined to think that they can actually reduce the practice – though we have to keep in mind that passing legislation is largely a symbolic normative act whose effects are likely to appear only in the long run.

Overall, my findings suggest that establishment of global norms, in the form of conventions and treaties, is key in understanding the diffusion of legislation against child marriage. However, they are not enough by themselves. World cultural norms need strategic actors operating through national legislatures and across national boundaries to become effective. Countries have passed these laws because the global system, i.e. the world polity, has come to define child marriage as a problem and charged states with acting to reduce this problem by setting the marriage age at 18. But for these laws to be passed, women legislatures and their regional networks played a significant role. Finally, my findings suggest that contesting global notions of marriage became a symbolic act for some Muslim majority countries.

Conclusion

The main puzzle this paper seeks to address is the global spread of laws setting the minimum age of marriage at 18. What prompted countries to pass such legislation? The findings from the survival analysis point out that involvement with the larger world and existence of women legislators and their networks matter. Involvement with counter-scripts, in this case possibly through political Islam, have a negative effect. Exposure to global norms is particularly important as the initial force in passing minimum age of marriage laws globally. Once norms about childhood started to become institutionalised, largely a CRC effect, regardless of their local characteristics, countries started to pass such laws. Countries do not set the marriage age in relation to local customs or culture but embrace the global norm. Moreover, once countries pass the minimum age legislation, they do not revert back to the earlier versions or lower the marriage age. At this point, it is an empirical question to what extent this is reflective of the actual marriage age patterns or to what extent such laws are actually implemented. Regardless, although they may be symbolic, global norms are important in taking legislative steps about child marriage.

However, global norms by themselves were not enough to push for legislation. The relevance of women parliamentarians for the adoption of the minimum age of marriage legislation suggests that norm travel with the help of strategic actors such as regional networks of female parliamentarians. It may be true that women parliamentarians are more likely to respond to the international treaties concerning women and children and push for the legislation in accordance with the international norms. It may also be true that presence of networks of women parliamentarians helps the global standard to be fully codified.

The consistent support for the relevance of the ratification of treaties, particularly that of the CRC, when read with the inconsistent support for embeddedness in the world society measured by INGO involvement is suggestive of the direct effect of the CRC on states that is not necessarily mediated by INGOs. This maybe because preferences of INGOs for stronger laws and implementation are in conflict with rather symbolic moves of the states. They may be using other means of advocacy and communication with international organisations and treaty monitoring bodies such as shadow reporting.Footnote9 However, it may also be the case that other actors are more important in pushing the states for legislation. As discussed in the previous section, there is some anecdotal evidence for the relevance of parliamentary networks particularly in African and Latin American countries to explain passing minimum age 18 laws. It may also be true that states are willing to ratify treaties concerning children and pass legislation due to children’s rights being relatively less controversial. That is to say, issues concerning children have a special moral status and it is easy to present them as above and beyond political divides. Therefore, it is easy for states to pass legislation for the good of children without risking any domestic political turmoil. In other words, passing such legislation awards states with international legitimacy without the risk of creating conflicts domestically.

The lack of INGO effect together with the significance of women legislators have implications for understanding diffusion processes as theorised by WST scholarship. As mentioned earlier, WST scholarship theorises INGO networks as primary carriers of global norms. The case of minimum age of marriage shows that local actors such as women politicians can also be carriers of such norms. One implication of this finding for WST is that carriers of culture may be different for different issue areas. INGOs are not equally effective in all areas. The sweeping INGO argument may work for more public issues like education, trade while it does not hold true for rather private issues such as marriage, divorce, corporal punishment (ref) and alike. Cole and Perrier’s (Citation2019) study also find that INGOs are more effective in domains that are highly institutionalised. In this study, I do not unpack why women parliamentarians are more effective in passing for legislation of minimum age of marriage. This is an area of exploration for further research.

Finally, the negative effect of Muslim majority, is suggestive of a counter script about ideal marriage, childhood, and gender roles based on Islamic principles. This may be particularly true in contexts where political Islam is strong and is seeking to present an alternative to the global script. In these contexts, the legitimacy is not sought with reference to global cultural conceptions of gender equality or ideal childhood but with respect to ‘local’ practices. However, whether this is the case is an empirical question which would require in-depth qualitative analysis of different cases which is beyond the scope of this paper. One direction for future researchers then is understanding more about how world cultural models interact with local norms, that is, how local actors are shaped by and, in turn, shape global norms and models. Some recent scholarship in the world society tradition delves into this issue, by relying on social surveys or qualitative methods such as in-depth interviews that explore how world cultural scripts interact with local attitudes and beliefs (Boyle et al Citation2002, Hadler Citation2016, Qadir Citation2016).

The negative effect on Islam on minimum age of marriage legislation is not surprising when considered in the context of previous WST scholarship. Many WST studies find a negative Islam effect. Islam is negatively correlated with the incidence of divorce (Wang and Schofer Citation2018), abolition of death penalty (Mathias Citation2013), labour force participation and parliamentary representation of women (Russell Citation2015), women’s social rights (Yoo 2012). Some WST studies on the domain of gender and sexuality do not focus on Islam exclusively even when religion is a part of the theorising (Frank Citation1999, Kim et al Citation2013). My findings suggest that a closer look into how Islamic countries engage with global norms is needed particularly in the areas of gender and sexuality. With the current backlash against feminism globally and politicisation of gender rights, this is more relevant than ever (Cupać and Ebetürk Citation2020). Future WST research should unpack the Islam effect. Does the negative Islam effect tell us a cultural story? Is the negative effect limited to contexts where Islam is a political project? Do different versions of Islam have different effects? Is it possible to claim that Islamic countries are centres from which a different script diffuses from? These are some of the questions that WST scholarship can explore for a novel understanding of diffusion and contestation patterns.

Another relevant question this study has not examined is whether passing age-18 marriage laws actually changes child marriage rates. This is a question addressed in some other works influenced by the world society perspective (Boyle Citation2005, Boyle and Kim Citation2009, Kim and Boyle Citation2012, Kim et al. Citation2013, Longhofer & Schofer Citation2010). Among these studies, some provide support for the effect of global norms on actual implementation of laws while others find no such relationship. For instance, Kim et al. (Citation2013) found that in countries where marriage age laws adhere strictly to global norms, the rates of adolescent fertility are lower. However, Boyle’s (Citation2002) work on female genital mutilation (FGM) concluded that, although global norms are effective in the emergence of new norms about the practice, they may not actually decrease the rates of FGM. Following this body of work, it is important to account for the issue of ‘when laws matter’ in decreasing the actual rates of child marriage.

Acknowledgment

I would like to thank the editor and anonymous reviewers as well as John Boli and Jelena Cupać for their constructive feedback.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 I also coded the dependent variable as an ordinal variable, from no laws to strict laws. (1 = strictly 18, 2 = 18 with exceptions, 3 = not set/below 18). The first category sets the age at 18 without exceptions. However, this ordinal variable turned out to be a non-viable option for two reasons: only 19 countries (of 167) have a strict law setting the minimum age at 18, and most of these laws were passed since the late 1990s. This created a dependent variable with only 5% of the observations in the category, which led to uninterpretable results skewed heavily toward the latter part of the analysis period.

2 It is important to note that in many cases the minimum age of marriage laws allow for exceptions such as parental consent, court approval, pregnancy or recognition of religious/customary law. When all exceptions are taken into consideration, 18 as the minimum age of marriage is far from being the norm. However, when countries pass laws that reform the marriage age, it is always the case they set it up to 18, albeit with exceptions. This indicates some approval of the global norm. In 47 countries, where the minimum age of marriage is currently below 18 (see Appendix), whenever there is a push for raising the minimum age of marriage by legislators and advocates, the goal has always been to raise it to 18, not an earlier age.

3 In some cases, such as the USA, because of the lack of a federal level legislation, the marriage age is coded as below 18. Longitudinal comparative data does not exist for federal level laws. The decision to code such cases in the category of ‘below 18/no law’ is the most consistent option within such data limitations. Further research should be conducted to account for the mismatch for federal and state level legislations of child marriage.

4 One of the assumptions of the Cox model is event occurrence at different times or non-existence of ties (Borucka, Citation2014; Matthias, 2013). As legislation events involve many ties – more than one country passes legislation in a single year – this assumption is violated. I corrected for this problem by using the Efron method in the Cox regressions (Matthias, 2013; Efron, Citation1977).

5 I tested the Cox model’s proportional hazard assumption by using the Schoenfeld residuals test (Matthias, 2013; Schoenfeld, Citation1982). All of the models pass the ‘phtest’ indicating that proportional hazards assumption is met in each of them.

6 To test this, I estimated the models for the period after 2000 only. Those models provide some support for the effect of INGOs particularly after late 1990s hypothesis. I rerun all models that has either INGO or WINGO variable, which adds up to six models. In three of these six models, either INGO or WINGO variable is significant and positive. The effect of CRC and female parliamentarians ceases to exist in these models. I do not include those models for brevity. The tables are available upon request.

7 To check whether framing child marriage as a children’s rights issue is predictive of passing legislation against it, I tested other variables which would indicate empowerment of children. I added female secondary school enrollment rates as a control variable however this variable did not reach significance in any of the models. The absence of such effect may suggest two things: passing the minimum age of marriage legislation is simply a relatively costless act by the states compared to investing in girls’ education or enrollment rates is not good measure of children’s empowerment. However, it is the only measure that is available for the period and on a global scale.

8 It would be ideal to include an independent variable testing the role of women legislators’ regional networks. However, there is no systematic data on regional networks for the period and states covered by this study.

9 I would like to thank the anonymous reviewer for this helpful suggestion.

References

- ACPF. (2013). Harmonization of laws in Africa. http://www.africanchildforum.org/clr/Harmonisation%20of%20Laws%20in%20Africa/other-documents-harmonisation_7_en.pdf.

- Agerholm, H. (2016). MPs in Turkey support bill allowing child rapists to go free if they marry their victim. Independent, November 18.

- Allison, P. D. (2010). Survival analysis. In G. R. Hancock, & R. O. Mueller (Eds.), The reviewer’s guide to quantitative methods in the social sciences (pp. 413–425). New York: Routledge.

- Allison, P. (1984). Event history analysis. Regression for longitudinal event data.

- Amahazion, F. (2016). Human rights and world culture: The diffusion of legislation against the organ trade. Sociological Spectrum, 36(3), 158–182. doi:10.1080/02732173.2015.1108887

- Boli, J. (2005). Contemporary developments in world culture. International Journal of Comparative Sociology, 46(5–6), 383–404. doi:10.1177/0020715205058627

- Boli, John. & Thomas, George, M. (Eds.). (1999). Constructing world culture: International nongovernmental organizations since 1875. Stanford, CA: Stanford University

- Borucka, J. (2014). Methods for handling tied events in the Cox proportional hazard model. Studia Oeconomica Posnaniensia, 2(2), 91–106.

- Boyle, E. H. (2007). The rise of the child as an individual in global society. In Sudhir Alladi Venkatesh and Ronald Kassimir (Eds.), Youth, globalization, and the Law (pp. 255–284). Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

- Boyle, E. H., & Kim, M. (2009). International human rights Law, global economic reforms, and child survival and development rights outcomes. Law & Society Review, 43(3), 455–490. doi:10.1111/j.1540-5893.2009.00379.x

- Boyle, E. H., McMorris, B. J., & Gomez, M. (2002). Local conformity to international norms: The case of female genital cutting. International Sociology, 17(1), 5–33. doi:10.1177/0268580902017001001

- Boyle, E. H. (2005). Female genital Cutting: Cultural conflict in the global community. Baltimore, MD: JHU Press.

- Boyle, E. H., Kim, M., & Longhofer, W. (2016). Abortion liberalization in world society, 1960–2009. American Journal of Sociology, 121(3), 882–913. doi:10.1086/682827

- Brehm, H. N., & Boyle, E. H. (2018). The global adoption of national policies protecting children from violent discipline in schools and homes, 1950–2011. Law & Society Review, 52(1), 206–233. doi:10.1111/lasr.12314

- Bruce, J. (2005). Child marriage in the context of the HIV epidemic. http://www.popline.org/node/264310.

- Burnet, J. E. (2008). Gender balance and the meanings of women in governance in post-genocide Rwanda. African Affairs, 107(428), 361–386. doi:10.1093/afraf/adn024

- Cammack, M., Young, L., & Heaton, T. B. (1996). Legislating social change in an Islamic society: Indonesia’s marriage law (SSRN scholarly paper No. ID 2559576). Rochester, NY: Social Science Research Network.

- Celis, K. (2007). Substantive representation of women: The representation of women’s interests and the impact of descriptive representation in the Belgian parliament (1900–1979). Journal of Women, Politics & Policy, 28(2), 85–114. doi:10.1300/J501v28n02_04

- Cole, W. M., & Perrier, G. (2019). Political equality for women and the poor: Assessing the effects and limits of world society, 1975–2010. International Journal of Comparative Sociology, 60(3), 140–172. doi:10.1177/0020715219831422

- Cox, D. R. (1972). Regression models and life-Tables. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society, 34(2), 187–220.

- Cupać, J., & Ebeturk, I. (2020). The Personal is global political: Antifeminist backlash in the United Nations. The British Journal of Politics and International Relations, 22(4), 702–714. doi:10.1177/1369148120948733

- Desai, S., & Andrist, L. (2010). Gender scripts and Age at marriage in India. Demography, 47(3), 667–687. doi:10.1353/dem.0.0118

- Devlin, C., & Elgie, R. (2008). The effect of increased women’s representation in parliament: The case of Rwanda. Parliamentary Affairs, 61(2), 237–254. doi:10.1093/pa/gsn007

- Efron, B. (1977). The efficiency of Cox’s likelihood function for censored data. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 72(359), 557–565. doi:10.1080/01621459.1977.10480613

- Frank, D. J., Hironaka, A., & Schofer, E. (2000). The nation-state and the natural environment over the twentieth century. American Sociological Review, 96–116. doi:10.2307/2657291

- Frank, D. J., & Mceneaney, E. H. (1999). The individualization of society and the liberalization of state policies on same-sex sexual relations, 1984–1995. Social Forces, 77(3), 911–943. doi:10.2307/3005966

- Girls no Brides. (2017a). Malawi: Constitution no longer allows child marriage. Retrieved June 9, 2017, from http://www.girlsnotbrides.org/malawi-constitution-no-longer-allows-child-marriage/.

- Girls not Brides. (2017b). Child marriage around the world. Retrieved June 10, 2017, from http://www.girlsnotbrides.org/where-does-it-happen.

- Guha, S. (2017). The Dangers of the New Child Marriage Law in Bangladesh. Al-Jazeera, March 4

- Hadler, Markus. (2016). Individual action, world society, and environmental change: 1993–2010. European Journal of Cultural and Political Sociology 3(2–3), 341–374.

- Kamal, S. M., & Hassan, C. H. (2015). Child marriage and its association with adverse reproductive outcomes for women in Bangladesh. Asia Pacific Journal of Public Health, 27(2), NP1492–NP1506.

- Khayri, A. (2012). New proposals threaten women’s rigths in Egypt. Al-Monitor, May 19.

- Kim, M., & Boyle, E. H. (2012). Neoliberalism, transnational education norms, and education spending in the developing world, 1983–2004. Law & Social Inquiry, 37(2), 367–394. doi:10.1111/j.1747-4469.2011.01267.x

- Kim, M., Longhofer, W., Boyle, E. H., & Nyseth, B. H. (2013). When do laws matter? National minimum-age-of-marriage laws, child rights, and adolescent fertility, 1989–2007. Law & Society Review, 47(3), 589–619. doi:10.1111/lasr.12033

- Kittilson, M. (2008). Representing women: The adoption of family leave in comparative perspective. The Journal of Politics, 70, 323–334. doi:10.1017/S002238160808033X

- Le Strat, Y., Dubertret, C., & Le Foll, B. (2011). Child marriage in the United States and its association with mental health in women. Pediatrics, Peds–, 2011, 524–530.

- Lechner, F. J., & Boli, J. (2005). World culture: Origins and consequences. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Lee-Rife, S., Malhotra, A., Warner, A., & Glinski, A. M. (2012). What works to prevent child marriage: A review of the evidence. Studies in Family Planning, 287–303. doi:10.1111/j.1728-4465.2012.00327.x

- Lexadin. (2016). World law guide. https://www.lexadin.nl/wlg/legis/nofr/legis.php.

- Longhofer, W., & Schofer, E. (2010). National and global origins of environmental association. American Sociological Review, 75(4), 505–533. doi:10.1177/0003122410374084

- Mathias, M. D. (2013). The sacralization of the individual: Human rights and the abolition of the death penalty 1. American Journal of Sociology, 118(5), 1246–1283. doi:10.1086/669507

- Mathur, S., Greene, M., & Malhotra, A. (2003). Too young to wed: the lives, rights and health of young married girls. http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/summary?doi=10.1.1.677.8700.

- Melchiorre Angela. (2004). At What Age? Right to Education Project. (2nd ed.). Available online at http://www.right-to-education.org/

- Momeni, D. A. (1972). The difficulties of changing the age at marriage in Iran. Journal of Marriage and Family, 34(3), 545–551.

- Moschetti, C. O. (2005). Conjugal wrongs don’t make rights: International feminist activism, child marriage and sexual relativism. https://minerva-access.unimelb.edu.au/handle/11343/39560.

- Nguyen, M. C., & Wodon, Q. (2015). Global and regional trends in child marriage. The Review of Faith & International Affairs, 13(3), 6–11. doi:10.1080/15570274.2015.1075756

- Nguyen, M. C., & Wodon, Q. (2012). Child marriage and education: A major challenge. Study Conducted with Funding from the Trust Fund for Environmentally and Socially Sustainable Development (TFESSD) at the World Bank.

- Parsons, J., Edmeades, J., Kes, A., Petroni, S., Sexton, M., & Wodon, Q. (2015). Economic impacts of child marriage: A review of the literature. The Review of Faith & International Affairs, 13(3), 12–22. doi:10.1080/15570274.2015.1075757

- Paxton, Pamela, Jennifer Green, and Melanie Hughes. (2008). Women in parliament, 1945–2003: Cross national dataset. ICPSR24340-v1. Ann Arbor, MI: Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research [distributor], 2008-12-22.

- PGA. (2018). http://www.pgaction.org/campaigns/cefm.html.

- Phillips, A. (1995). The politics of presence. Oxford: Oxford University Press. http://books.google.com/books?hl=en&lr=&id=KFuw2VZMlW0C&oi=fnd&pg=PP11&dq=politics+of+presence&ots=H8_ZOzJCyH&sig=BBlzLQaUp5wOT0pOuqVEr2CabH4.

- Plan International. (2017). Dominican Republic takes steps to ban child marriage. (n.d.). Retrieved June 7, 2017, from https://plan-international.org/dominican-republic-bans-child-marriage.

- Psaila, E., Vanessa, L., Marilena, V., Sara, F., Virginia, D. P., & Gomez, A. (2016). Forced Marriage from a Gender Perspective – Think Tank. Retrieved June 10, 2017, from http://www.europarl.europa.eu/thinktank/en/document.html?reference=IPOL_STU(2016)556926.

- Qadir, A. (2016). Introduction: Through an iron cage, darkly. European Journal of Cultural and Political Sociology, 3(2–3), 141–151. doi:10.1080/23254823.2016.1207877

- Raj, A. (2010). When the mother is a child: The impact of child marriage on the health and human rights of girls. Archives of Disease in Childhood, 95(11), 931–935.

- Raj, A., & Boehmer, U. (2013). Girl child marriage and its association with national rates of HIV, maternal health, and infant mortality across 97 countries. Violence Against Women, 19(4), 536–551. doi:10.1177/1077801213487747

- Raj, A., McDougal, L., Silverman, J. G., & Rusch, M. L. (2014). Cross-sectional time series analysis of associations between education and girl child marriage in Bangladesh, India, Nepal and Pakistan, 1991-2011. PloS One, 9(9), 1–9. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0106210

- Raj, A., Saggurti, N., Balaiah, D., & Silverman, J. G. (2009). Prevalence of child marriage and its effect on fertility and fertility-control outcomes of young women in India: A cross-sectional, observational study. The Lancet, 373(9678), 1883–1889. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60246-4

- Roy, O. (2006). Globalized Islam: The search for a new Ummah. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Russell, R. J. (2015). Constructing global womanhood: Women’s international non-governmental organizations, women’s ministries, and women’s empowerment [PhD Thesis]. UC Irvine.

- Schoenfeld, D. (1982). Partial residuals for the proportional hazards regression model. Biometrika, 69(1), 239–241. doi:10.1093/biomet/69.1.239

- Schofer, E., Hironaka, A., Frank, D. J., & Longhofer, W. (2012). Sociological institutionalism and world society. In Amenta, E., Nash, K., and Scott, A. The Wiley-Blackwell Companion to Political Sociology (pp. 57–68). Chichester: Blackwell Publishing.

- Schwindt-Bayer, L. A., & Mishler, W. (2005). An integrated model of women’s representation. The Journal of Politics, 67(2), 407–428. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2508.2005.00323.x

- Scolaro, E., Blagojevic, A., Filion, B., Chandra-Mouli, V., Say, L., Svanemyr, J., & Temmerman, M. (2015). Child marriage legislation in the Asia-Pacific region. The Review of Faith & International Affairs, 13(3), 23–31. doi:10.1080/15570274.2015.1075759

- Speizer, I. S., & Pearson, E. (2011). Association between early marriage and intimate partner violence in India: A focus on youth from Bihar and Rajasthan. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 26(10), 1963–1981. doi:10.1177/0886260510372947

- Swers, M. L. (1998). Are women more likely to vote for women’s issue bills than their male colleagues? Legislative Studies Q, 23, 435–448. doi:10.2307/440362

- Teorell, Jan, Nicholas Charron, Stefan Dahlberg, Sören Holmberg, Bo Rothstein, Petrus Sundin & Richard Svensson. (2013) The quality of government basic dataset made from the quality of government dataset. University of Gothenburg: The Quality of Government Institute: http://www.qog.pol.gu.se

- The Local. (2017). German parliament passes law ending child marriage. Retrieved June 7, 2017, from https://www.thelocal.de/20170602/german-parliament-passes-law-ending-child-marriage.

- Thomas, S. (1991). The impact of women on state legislative policies. The Journal of Politics, 53(4), 958–976. doi:10.2307/2131862

- Tibi, B. (2014). Political Islam, world politics and Europe: From Jihadist to institutional Islamism. New York: Routledge.

- Toyo, N. (2006). Revisiting equality as a right: The minimum age of marriage clause in the Nigerian child rights Act, 2003. Third World Quarterly, 27(7), 1299–1312. doi:10.1080/01436590600933677

- UN Treaties. (2017). United Nations Treaty Collection. Retrieved June 10, 2017, from https://treaties.un.org/.

- UNHRC. (2013). Strengthening efforts to prevent and eliminate child, early and forced marriage. https://documents-dds-ny.un.org/doc/UNDOC/LTD/G13/175/05/PDF/G1317505.pdf?OpenElement.

- United Nations. (1962). Convention on Consent to Marriage, Minimum Age for Marriage and Registration of Marriages.

- United Nations. (1948). Universal Declaration of Human Rights. http://www.un.org/en/universal-declaration-human-rights/.

- United Nations. (1979). Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women. Retrieved June 7, 2017, from http://www.un.org/womenwatch/daw/cedaw/cedaw.htm.

- United Nations. (1989). Convention on the Rights of the Child. (1989). Retrieved June 7, 2017, from http://www.ohchr.org/EN/ProfessionalInterest/Pages/CRC.aspx.

- Wang, C.-T. L., & Schofer, E. (2018). Coming Out of the Penumbras: World culture and Cross-national Variation in divorce rates. Social Forces, 97(2), 675–704. doi:10.1093/sf/soy070

- Wängnerud, L. (2009). Women in parliaments: Descriptive and substantive representation. Annual Review of Political Science, 12(1), 51–69. doi:10.1146/annurev.polisci.11.053106.123839

- WHO. (2016). Child, early and forced marriage legislation in 37 Asia-Pacific countries. https://beta.ipu.org/resources/publications/reports/2016-07/child-early-and-forced-marriage-legislation-in-37-asia-pacific-countries.

- World Policy Center. (2017). Marriage. Retrieved June 10, 2017, from https://www.worldpolicycenter.org/topics/marriage/policies.

- Yoo, E. (2011). International human rights regime, neoliberalism, and women’s social rights, 1984–2004. International Journal of Comparative Sociology, 52(6), 503–528. doi:10.1177/0020715211434850

Appendix

Year minimum age set at 18 (if changed after 1965).

Countries in which the marriage age was 18 (with or without exceptions) by the year 1965.

Countries in which the marriage age is below 18 for either or both sexes, or no marriage age was established by 2015.