ABSTRACT

This article draws on Pierre Bourdieu's political sociology for a statistical study of the complex interrelationship between Norwegian citizens’ attention and engagement in the world of politics and broader public debate, and how such public lifestyles align with social structures. Using multiple factor analysis the article provides a broad mapping of citizens’ use of media and culture, participation in civil society and politics, and attitudes to news and politics. It identifies a principal divide by citizens’ attention to and familiarity with the worlds and discourses of social elites and a secondary divide by their forms and areas of engagement. Both divides are structured by class position and, in the case of the second, generational divides. The article argues for the value of class approaches and a broad focus on people's relationship with the worlds of social elites for understanding public engagement.

Introduction

The following study of Norwegian citizens has two aims. The first is to map, in some detail, how citizens’ participation in political and civic life, their varying attention to political and broader public debate, and their use of media content and culture constitute a space of public lifestyles. The study thus also explores homologies between citizens’ attitudes and practices in realms that are more commonly studied separately, by different scholarly fields, in an integrative approach inspired by sociologist Pierre Bourdieu's (Citation1984) comprehensive conceptualisation of politics. The second aim is to study how such public lifestyles, even in one of the most egalitarian countries in the world, are structured by social divides, emphasising the role of social class and generations. At the root of the study lies the ongoing discussions about the changing nature of political involvement and engagement and the normative expectations of citizens.

A basic assumption of liberal democratic theory is that a well-functioning democracy presupposes a citizenry that participates in political processes and follows current affairs (Habermas, Citation1974). However, the majority of citizens in modern societies do not appear to meet such standards. Many Europeans do not even vote in national elections, and few are members of, and even fewer active participants in, political parties (Smith, Citation2020). Interest in political news, especially among young people, is low (Blekesaune, Elvestad, & Aalberg, Citation2010). Many citizens appear increasingly disconnected and alienated from the realm of politics (Bauman, Citation1999; Dassonneville & Hooghe, Citation2018).

In democratic theory, this mismatch between democratic ideals and the realities of people's attention is central to a long-standing debate between competing models. In the forum models of democracy (Elster, Citation1986), which includes Habermas’ model, inclusive processes of deliberation, where people form enlightened opinions by following and actively contributing to societal debates, are necessary for making the right decisions in matters of shared concern. Some have suggested less demanding variants, e.g. the monitorial citizen expected only to loosely monitor the debate and take part when necessary (Schudson, Citation1998). In market models of democracy, associated with Schumpeter (Citation1950), citizens’ involvement is limited to choosing between better-informed representatives, themselves lacking in knowledge, abilities, and political interest. The private citizen is here a ‘deaf spectator in the back row’ who ‘cannot quite manage to stay awake’ and who finds it hard to understand or even care about public affairs, even knowing that they are affected by them. To expect more of them would be unrealistic and even bad for them, like expecting ‘a fat man to try to be a ballet dancer’ (Lippmann, Citation1925, pp. 150, 139).

In sociology, the problem of people's attention and non-attention is a fundamental issue (e.g. Goffman, Citation1974; Mannheim, Citation2013; Zerubavel, Citation1999). Regarding normative models as above, the main issue for many sociologists (and some normative theorists, like Fraser (Citation1992)) with such models is that they ignore the social variation in peoples’ relation to the political. In Western democracies, this relationship is still deeply marked by social inequality (Gaxie et al., Citation2014), an inequality which is also increasing (Piketty, Citation2014; Savage, Citation2021). However, the continuing relevance of social classes for understanding such differences is a contested issue. Some argue that class has become less important for understanding political practices (e.g. Goldthorpe, Citation2001; Pakulski & Waters, Citation1996; Wright, Citation2005). The classic argument (Lipset & Rokkan, Citation1967) is that earlier alignment of class politics and political position-takings, mainly due to changing material conditions and organisation of work in the post-war periods, have become disassociated and that old-style «emancipatory politics» – with the aim of justice, equality, and participation (e.g. women's or workers’ rights) – have been increasingly replaced by new «life politics», concerned with self-actualisation and lifestyle concerns in an age of uncertainty (Giddens, Citation1991). Related arguments involve the rise of new political values – as an increasing privatistic orientation among the labour class (Lockwood, Citation1966), a surge of post-materialistic values (Inglehart, Citation1977), or in a Weberian response, a rise of liberal versus authoritarian values (Heath, Jowell, & Curtice, Citation1985). Scholars following the example of Bourdieu (Citation1984), in contrast, argue for the continuing and even rising importance of social classes in the structuration of people's political practices (e.g. Bennett et al., Citation2009; Flemmen & Haakestad, Citation2018; Savage, Citation2015).

The problem of citizens’ attention cannot, however, be reduced to the realm of politics proper. If we follow Couldry, Livingstone, and Markham (Citation2007) and think of the problem as one of understanding – inspired by Habermas (Citation1989) writings on the public sphere – peoples’ public connection, how people engage with matters of common concern which are, or at least should be, addressed, it is evident that much of peoples engagement is mediated (Couldry et al., Citation2007), and the rise of new and hybrid media and its effects on political participation is still not very well understood (Schudson & Beckerman, Citation2020). Also, much of people's engagement takes place outside the political system, e.g. through participation in civil society (Putnam, Citation2000) and the use of culture, not least popular culture (Street, Inthorn, & Scott, Citation2015). The related problem is that the very ideas of what is political and what constitutes the public and the common good are not socially neutral classifications but are, in the words of Nancy Frasier (Citation1992, p. 73), ‘tainted by effects of dominance and subordination’. They are concepts that need, in the terminology of the ethnomethodologists, to be bracketed and explored in relation to the different worlds and interests of concrete social groups and specific national contexts. Here we find particularly informative Bourdieu's (Citation1984, Citation2001) sociology of the relationship between classes and lifestyles and his insistence on politics as not just the dealings of the state and politicians, but any attempt to mobilise public support for particular views of the social world.

Thinking politics without thinking politically

A central concern for Bourdieu was the production and reproduction of Weber's (Citation2014, p. 90) distinction between political active and political passive elements – the latter as a necessary precondition for the former. The propensity to participate in politics must, according to Bourdieu, be sought in general social conditions beyond the realm of «politics proper». First, via social inheritance, in a habitus more or less favourably disposed to such matters by early socialisation. Second, via inheritance and social trajectory (e.g. education and working life), the accumulation of favourable forms of capital and lifestyles, including social capital (e.g. personal connections to the political field), cultural capital (symbolic resources for relevant thought, expression, and action) and economic capital (e.g. the use of free time on politically related activities), habits for news consumption, etc. (Bourdieu, Citation1984).

When it comes to the political system, different classes have demonstrably very different relations to it due to their particular combination of habitus, capital, and lifestyles. Summing up and expanding on Bourdieu's work, Daniel Gaxie (Citation2014) outlines eight dimensions as particularly important and variable by social class: Their (1) investment (e.g. varying participation in political parties and reading of political news), (2) tacit definitions of what lies inside and outside politics (working classes often having a more narrow view, e.g. excluding local affairs), (3) expectations, preferences and orientations (e.g. lower classes typically having fewer, vaguer and more ill-defined considerations when arguing for their preferences), (4) attitudes towards voting (e.g. as a duty versus to express a preference), (5) scepticism of political actors, (6) feelings of competence (a «sense of place» experienced as a right to speak in political matters), (7) cognitive competence (closely related to cultural capital, including e.g. mastering abstract political ideologies and having knowledge of the current stakes and balances of the political field), (8) modes of production of opinions (e.g repeating leaders views, using purely moral criteria, recurse to personal experiences or, in educated groups, using specific political judgements).

While many indicators of these aspects are used in the following analysis, we are, as noted, not only interested in citizens’ politicisation (Gaxie, Citation2014) but also in how this is related to their broader mobilisation and attention inspired by Bourdieu's concern to ‘think politics without thinking politically’ (Citation1988, p. 2): Rather than accepting pre-constructed social categorisations of what constitutes as political or not, the sociologist should overcome the ‘sacred border between culture and politics, pure thought and the triviality of the agora’ (Bourdieu, Citation1988, p. 3). Struggles between political elites were, for Bourdieu, only one case of political struggles, which he saw as more fundamental, as ‘a cognitive struggle (practical and theoretical) for the power to impose the legitimate vision of the social world, or more precisely, for the recognition, accumulated in the form of a symbolic notoriety and respectability, which gives the authority to impose the legitimate knowledge and of the sense of the social world, its present meaning and the direction in which it is going and should go’ (Bourdieu, Citation2000, p. 185). In this way, Bourdieu's lens pulls back from the field of politics to focus on the overarching field of power and the struggles between competing elites (Bourdieu, Citation1996).

Suppose we understand ‘politicisation’ as concerning people's attention and orientation towards the political field. In that case, it is then just a particular (if crucial) case of a more general phenomenon, namely peoples’ attention to, familiarity, and participation with social fields – and especially (as is evident in the case of politics) their elite fractions. We could, e.g. similarly talk of ‘culturalization’ for people's relationship to the cultural field, pointing to structural homologies (Bourdieu, Citation1984), parallel phenomena of classed variation in cultural alienation and investment, scepticism towards cultural agents, different modes of production of opinions on culture and feelings of cultural competence, etc. And so on for people's relationship to any other major field (‘bureaucratisation’, ‘economisation’, ‘academisation’, etc.), which, when coalescing favourably may even form a general cultural (or informationalFootnote1) capital of the field of power – what we might term elite capital.

When we, in this way, broaden our analysis from citizens’ orientation and attention from politics proper to activities in other major social fields, our object of study acquires thematic similarities with central problematics in the work of Habermas (Citation1989) on citizens’ engagement in public debate. While agreeing with the potential fruitfulness of dialogue between these two traditions (Benson, Citation2009; Calhoun, Citation2010; Crossley, Citation2004), the following analysis is firmly rooted in the Bourdieuan tradition and uses the concept of the public heuristically, i.e. as an explorative concept. The research aim is, first, to map the main divisions in people's public lifestyles in Norway, especially their varying attention and relation to the activities and discourses of powerful agents, and second, the role of social differences, in particular class differences, for structuring such public lifestyles. In other words, we are interested in the structural relationship between public classes and social classes. In this way, the analysis empirically addresses both central concerns in deliberative democratic theory, not least the systematic distortion of political communication (Habermas, Citation1970), as well as critical perspectives on such theories, namely the social conditions and variations of reason and universality which deliberative ideals presuppose (Bourdieu, Citation2000).

The national context

Political engagement can only be understood in context (Gaxie, Citation2014), and Norway offer several specific traits. Like other Scandinavian countries, it is culturally relatively homogenous, with high standards of living and small social cleavages. A social democratic welfare state, it has traditionally aimed to be comprehensive (regarding the social needs it aims to satisfy), institutionalised via social rights that give all citizens a right to a decent standard of living, solidaristic and universal, intended for the whole of the population. This emphasis on cross-class solidarity and strong étatism contrast with liberal and traditional welfare states (Esping-Andersen, Citation1990). Norway has party pluralism and a system favouring consensus politics by a representative distribution of power (Heidar, Berntzen, & Bakke, Citation2013). The Scandinavian countries score among the highest on most indicators in the Democracy Index (EIU, Citation2019), including electoral process and pluralism, political participation and political culture, and also political trust (Putnam, Citation2000), with political elites being relatively open to social mobility (Hjellbrekke et al., Citation2007). The Scandinavian media systems, rooted in a similar welfare logic, have high newspaper circulation, a historically strong party press which has shifted towards neutrality, large structural press subsidies and a vital public service broadcaster (Hallin & Mancini, Citation2004), and high access and use of digital media (Hölig & Hasebrink, Citation2018). While there are signs of weakening of egalitarian and universal aspects of the Scandinavian models (Greve, Citation2017; Syvertsen, Moe, Enli, & Mjøs, Citation2014), the preconditions for equal public participation, it seems, are present here more than almost anywhere in the world. Norway, for such reasons, offers an interesting least-likely case of how political and other forms of public engagement are structured by social inequalities. If marked class structuration is observable here, as we will argue it is, it should be expected to be an integral feature of citizens’ public engagement and attention almost everywhere.

Data and method

The data comes from the MECIN survey (Kantar, Citation2017), supervised by the author, using a nationally representative web panel of Norwegian citizens over 15 years of age (N = 2064).Footnote2 The sample appears similarly representative to general national surveys, with a typical bias towards older people and the educated middle classes. The latter reminds us that participating in political surveys is a specific form of political engagement, presupposing specific dispositions and competence (Bourdieu, Citation1984), putting social limitations on statistical studies of such phenomena.

Whereas citizens’ relation to the political in qualitative sociological investigations is regularly conceptualised and investigated as a complex interplay of many aspects of people's lives (e.g. Gaxie, Citation2014; Harrits, Citation2013), statistical analysis of such phenomena, in contrast, typically focus on a small sample of the most recognisable political variables (e.g. voting, or attitudes to issues debated by national politicians). While especially true for methods aiming to isolate effects on single variables (e.g. regression), such data are also challenging for factor analytic techniques, which aim to reveal fundamental oppositions in complex relationships between variables. Following the model of Bourdieu's (Citation1984) investigation of homologies between classes and lifestyles, multiple correspondence analysis (MCA) has proved an invaluable tool for class analysis. Here, one set of indicators constructs the space of active variables (e.g. class relations), and other sets are projected onto this space as passive variables (e.g. lifestyles) or vice versa. However, a challenge with this method is that the active variables need to be relatively homogenous to avoid distorting the space (Le Roux & Rouanet, Citation2010). For our analysis of citizens’ complex public practices and orientations, multiple factor analysis (MFA) appears as an attractive methodical alternative. A still little-used technique in sociology (for two exceptions, see Robette & Roueff, Citation2019 and Noûs, Robette, & Roueff, Citation2021), it extends the logic of MCA to a situation where variables have a clear group structure, and it similarly involves the extraction of principal axes, canonical correlation techniques and Procrustes analysis. MFA proceeds in two steps. First, pseudoseparate analyses of the I × J table for each group are done using weighted correspondence analysis, and the eigenvalues of the axes are computed. Second, a global analysis is done on the top extracted axes following a logic close to a PCA, the highest axial inertia of each axis being normalised to 1 by dividing the weight of the columns in the set to the largest eigenvalue, offering a balanced analysis of the groups. The result provides the classical results of Geometric Data Analysis, including eigenvalues, contributions and individuals’ coordinates, while adding valuable measures on the homology between the subspaces, including the correlation between the principal axes and group RV coefficients (Husson, Josse, & Le, Citation2008; Pagès, Citation2014).

Indicators

The MFA analysis of Norwegian citizens includes 277 indicators for attention and engagement across fourteen variable groups (), four being supplementary, meaning that they did not influence the model's construction but provided additional richness. The variables range from specific types of media use, mediated attention to public issues and fields, various forms of engagement in political and civil life, social position, and attitudes (number of variables in parenthesis).Footnote3

Table 1. The variable groups for the MFA. Absolute contributions to global axis 1-4.

Variable groups 1–6 concerns mediated engagement, ranging from media platforms and formats (e.g. newspapers, radio, literature), specific channels and publications, types of content (e.g. specific tv programmes and news genres) and following concrete debates in the news. One group asks about social media uses, aiming to separate more private uses (e.g. personal status updates) from more public-oriented forms (e.g. sharing and commenting on news stories).

Groups 7–12 include membership in civil and political organisations, use of cultural institutions and political activism (e.g. demonstrations). The tenth includes questions ranging from following TV debates and discussing the election with friends to participating in parties’ campaigns. Groups 11–12 measure peoples’ attitudes to journalism and politics, including trust, feelings of engagement, competence and efficacy (e.g. feeling news or politics as hard to understand, knowing what political parties stand for), and of the felt relevance for their own lives.

The second last group place the respondent in the Norwegian social space following the theoretical and empirical model of Bourdieu (Citation1984), using common indicators of capital (including education, workplace, income, wealth, and parents’ resources). Like methodically similar analyses of class relations in Norway (e.g. Jarness, Flemmen, & Rosenlund, Citation2019; Rosenlund, Citation2000), this subspace broadly reproduces the main dimensions in Bourdieu's classic analysis, with a first axis for overall capital volume and a second for capital composition, dividing cultural and economic class fractions.Footnote4 Instead of a grouping of specific classes, the following analysis uses individuals’ relative differences in capital volume, and economic, cultural and social capital to suggest their class positions. Social capital (Bourdieu, Citation1986), the final variable group, is measured by affirmations of personal friendships with representatives from thirty-three occupations.

The space of public lifestyles

Each of the fourteen variable groups has its internal divides (the principal axes of each subspace). Reported interest in newspaper genres e.g. divides citizens first according to their interest in debate and international and national news (particularly political news), and second by their interest in culture and lifestyle genres. Similar divides are found in the remaining thirteen groups. Correlations between the first principal axes of the fourteen groups reveal many familiar correspondences () and interesting parallels across different social domains. Those expressing alienation from politics e.g. also more often agree that news are difficult or stressful to them, have lower interest in political news, lower activity in the national elections and less use of cultural institutions. A dominant pattern is that positive attitudes, attention and engagement towards the public, cultural and political realm tend to congregate and correlate with social resources (capital), a crucial link that will be explored in more detail in the succeeding sections.

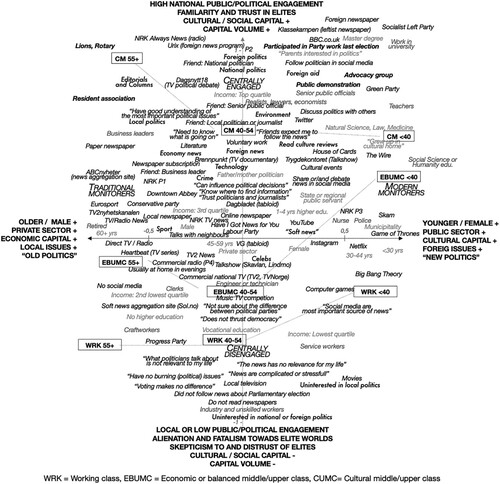

The eigenvalues suggest four statistically significant axes when constructing the global space (using all active variable groups).Footnote5 The first axis separates citizens by their general level of public attention and engagement, especially regarding political practices and the use of news. The most contributing variable groups are interest in news stories, activity in the General Election, preferred news genres, attitudes to politics, participation in various forms of activism, attitudes to news and membership in organisations. The second axis separates traditional and emerging forms of public engagement, especially emphasising differences in media platforms used, but also varying participation in activism, membership in organisations and interest in various news genres. The third and fourth axes bring out nuances between specific groups but do not contribute much to the overall picture.Footnote6 For this reason, the discussion will focus on the first two global axes, where a selection of the best characterising categories is shown in . The most notable categories for each axis are listed in and .Footnote7 More details on the statistical construction and variables are provided in the online appendix.

Table 2. Notable categories for the first axis of the MFA.

Table 3. Notable categories for the second axis of the MFA.

First dimension: Engagement and attention toward elite publics

The first division between citizens follows their degree of politicisation. Some – the closer they are placed towards the top of this space – feel that political debates and events are interesting, important, and natural (even irresistible) to pay attention to (or even participate in), have more trust in politicians and the political system, and are more often members of political organisations and interest groups. They also are more likely to enjoy discussing and sharing their political views with others, either face-to-face or via social media. They are more often personal friends with people in power (e.g. people working in a high public office, business leaders, journalists and politicians). Those placing lower in this space, in contrast, experience politics often as lacking relevance to their lives, as difficult to understand, and feel their votes are unlikely to make any difference. They appear little interested in debates involving national politicians and feel significant obstacles to their participation, including being uncertain about finding the information they need. They have low confidence in their ability to change things via political channels, express less trust in the political system, and feel lacking in political literacy (e.g. finding it often hard to understand the differences between the political parties). While describing a general feeling of alienation from the world of politics, the axis primarily positions people by their relation to the national (and international) world of politics. The differences are less pronounced for local politics and issues, resonating with findings that lower classes typically are more oriented towards their local community (Savage, Citation2015).

The differences do, however, not only concern the political system. The alienation to politics is, e.g. found in a homological form in people's views of the media, opposing trust and distrust, and in their experience of news as easy or difficult to understand, enjoyable or stressful. In the world of culture, a similar logic separates the use versus non-use of cultural institutions (e.g. museums, concerts), interest in reading cultural reviews in newspapers, what kind of TV series and literature one enjoys, and so forth. Generally following cultural hierarchies, those at the top exhibit signs of both traditional and emergent forms of cultural capital (Prieur & Savage, Citation2013). Examples of the latter are their outgoing cultural lifestyles and their preference for distinctive and complex forms of popular culture, e.g. TV series like House of Cards or The Wire. That these two TV series focus on much-debated political and social issues is a reminder both of the importance of expressive culture for providing information, upholding and energising people's interest in politics and debate (Nærland, Hovden, & Moe, Citation2020) and that this role of culture is likely stronger among the more privileged. Like for politics, the use of culture for such groups focuses on the most elite forms, discourses and agents. Similar arguments can be made for other fields, e.g. interest in the news concerning activities in the economic and bureaucratic field.

More than just a ‘political’ axis, then, the main opposition between citizens appears to concern varying attention, familiarity and engagement towards the agents, arenas and discourses of social elites, or elite publics, extending Nancy Fraser (Citation1992) «strong publics» – a concept she reserves for major political and bureaucratic bodies – to a broader sample of social elites, acknowledging their power to impose their classifications on the social world (Bourdieu, Citation1984).

Second dimension: forms and sectors of engagement

Citizens’ varying engagement towards these elite worlds (in particular, the world of politicians) and their discourse is modified by a series of other divisions (the horizontal in ), of which the most striking is age. While biological age obviously matters for public engagement, e.g. by the exclusion from working life of the youngest and oldest and health-related challenges for the latter, the divide appears mainly as one between generations in the sense of Mannheim (Citation1992). It separates generations united by many similar experiences and conditions (if varying by their social location), which are incorporated into their habitus and give rise to similar practices and orientations, e.g. seen in younger people's more intensive and wide-ranging use of social and digital media.

The differences, however, run deeper, opposing traditional and emerging forms of engagement, and bring to mind well-known arguments about the growth of urban lifestyles (e.g. younger generations’ higher use of outgoing forms of culture, like sports and cultural events) and a transition from materialist to postmaterialist values (Beck, Citation1992; Flanagan, Citation1982; Inglehart, Citation1977), and from «Old politics» to «New politics» (Hildebrandt & Dalton, Citation1978). The younger is e.g. more often oriented towards issue-oriented and sporadic forms of engagement (e.g. membership in advocacy organisations and taking part in demonstrations). They are also more likely to engage with environmental and international rather than local issues. However, as we shall see, such activities are more probable among higher than lower educated in all age groups, and age differences tend to decrease by educational level.

There is another crucial element to this axis, as it also divides citizens by their orientation towards different sectors of society. Those closer to the «older» pole are e.g. more often oriented towards the local community, private sector and industry, and those close to the «younger» pole towards the public and cultural sector (which also oppose males and females). This difference emerges in various practices, e.g. their place of work and subject of their studies, in their cultural participation, and in their interest in various types of news.

Generations, engagement and class

While many outward aspects of peoples’ public lifestyles (e.g. platforms used, forms and objects of engagement) differ much by generation, it is notable that the fundamental divides we observed along the first axis take strikingly similar forms inside each generation when the analysis is repeated on age subsamples (). Paying attention to public debate in the news or otherwise, debating these issues with others, feeling one can change things, and engaging in acts to change them, are in each generation systematically linked to having higher than average volumes of capital, and higher cultural, economic and social capital.Footnote8 In this perspective, many of the generational differences which often receive much scholarly attention (e.g. the use of social platforms to access news stories) appear as somewhat superficial phenomena; they usually concern the means rather than ends. And even in this regard, the differences between generations are less striking when we take class into consideration. ‘Old’ practices, like reading a national newspaper, watching PBS television or engaging in traditional party work, are more common among the privileged in both the younger and older cohorts, and the same goes for ‘young’ practices like the use of online news sites and partaking in various forms of issue activism (e.g. attending demonstrations). There are some interesting differences between the age groups, e.g. in how feeling that the news is too complex or voting is not worthwhile appears less socially divisive among the young. The overall impression, however, is that citizens of all generations are divided very similarly in their fundamental engagement and orientation to the political world (here used in a broad sense) and that this division is structured similarly and significantly by their capital, i.e. their different positions in the social world, in all age groups.

Table 4. Notable categories for the first global axis for three age subsamples.

Discussions and conclusions

Following this exploratory, broad mapping of citizens’ engagement and (especially) attention to politics and broader debate in Norway, we have identified a space of public lifestyles with two main divisions. The first is an orientation toward the worlds of social elites (particularly national politics), which contrasts with an orientation towards ordinary and subaltern social worlds, i.e. common peoples, local communities and places of work. This division is closely related to capital volume, with clearly measurable differences in cultural, economic, political and social capital and, thus, people's distance to elite publics, that is, the field of power (Bourdieu, Citation1996). Aside from reminding us that ‘news agendas’ and ‘public issues’ are often primarily the concern of social elites, it also emphasises how the distinction between the public and the private sphere (Habermas, Citation1974) diminishes the closer one gets to the pole of power. As noted by Bourdieu (Citation1984), a central privilege for the privileged is that their interests (in both senses of the word, investments and attention) are bound up with «important’ matters in society – e.g. via their place of work and their friends. In this way, the virtuous interest of the socially privileged in «important» news and debates is not qualitatively different from ordinary people's interest in ‘gossip’ about their local community. To be interested or disinterested in politics is also the difference between making and being subject to politics and connecting with a real, as opposed to an imagined community. By their dispositions, lifestyles and resources – cultural, social, political, economic, and educational – the lives of the privileged appear in this analysis as more closely interwoven with and with a more ‘natural’ (that is, social) interest and attraction to the worlds of elites – including, but not limited to, the world of politicians. The second axis is somewhat different. It sketches a frozen history of the public engagement by contrasting traditional and modern forms and objects of engagement (e.g. use of digital versus traditional media, engagement via political parties versus single-issue activism, etc.), correlated with – but not reducible to – generational cleavages (and also, gender differences). But it also, importantly, divides people by their orientation towards different sectors of the social world, especially regarding their engagement towards the private contra the public and cultural sector, echoing citizens’ capital composition (). The effects of homology can thus be observed at two levels. On the one hand, in the orchestration of resources, practices, and attitudes in separate realms (e.g. feelings of political efficacy and interest in culture) into consistent public lifestyles. On the other hand, in the structural parallels between such lifestyles and the social space, between the topoi of the public world (in the rhetorical meaning of both places and themes) and the social topography of the uneven distribution of capital (i.e. classes). Furthermore, the strong similarities between the generations in this regard, of people brought up under very different conditions (not least technological) for public attention and participation, suggest this is a persistent feature of the Norwegian society.

The analysis thus argues for the continuing relevance of class to make sense of political phenomena. It demonstrates that people's relation to politics and broader debate, also in a relatively egalitarian society like Norway, are structured stably along class lines while also emphasising, as others have done, the need to look at the intersection between class and generational cleavages (Glevarec & Cibois, Citation2020). While many of the differences between citizens found in this study and their relation to social privilege (indicated by educational level) are to be expected, even well-known from earlier studies of political participation, civic engagement and media use in Scandinavia (some of which are mentioned in the earlier parts of this article), the findings stress the importance of understanding citizens political engagement in the context of their broader lifestyles and their social position. This can be seen e.g. by how citizens in similar class positions tend to have similar relationships with other social elites as they have with political elites and by how political and cultural practices appear, especially for the privileged, as two sides of the same coin, not just correlated but integrated into their lifestyles, strengthening and blurring into each other. Finally, it illustrates how normative theories’ varying expectations of citizens appear to have different social classes’ realities and resources as their implied citizens (e.g. for Habermas, the upper middle classes, Schudson the lower middle classes, and Schumpeter the working classes). Any essentialisation of the citizens’ role, interest and capabilities, however, appears, in light of our findings and the Bourdieuan view of politics that inspired them, not only as a sociologically unrealistic fundament for a normative democratic theory, but also as a theoretical act of symbolic violence (Bourdieu, Citation1977) by their disparagement of ordinary people's ordinary engagement in their ordinary worlds versus the extraordinary worlds to which they are effectively outsiders, continuing a tale of working classes as pathological (cf. Skeggs, Citation2004).

Rather than a simple tale about citizens being ‘disengaged’ or ‘engaged’, then, a geographical analogy seems more appropriate, where peoples habitus, social trajectory, and resources place them in the social space, with varying social distance to the milieus involved, forming different familiarity with the elite agents, their culture and the history of the struggles and stakes in necessary social fields, different mastery of the classifications and terminology involved, and varying feelings of engagement, efficacy and alienation, including a «sense of one's place» (Bourdieu, Citation1986, p. 141). The adage that politics is ‘the art of the possible’ is not only true for politicians; it also contains a hard truth about the realities of the social world and its limitations for the political engagement of ordinary citizens.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (639.1 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 In his lectures on Collège de France, Bourdieu (Citation2021, pp. 243–244) presents the concept of informational capital as an invitation to think about how his specific writings on cultural capital addresses more fundamental characteristics and mechanisms (e.g. the importance of embodiment and familiarization).

2 6502 respondents were invited via e-mail. 39% opened it, and of these, 85% responded.

3 All variables were binary coded except social class, where the five variables had 23 categories.

4 For further details of this model, see Hovden & Rosenlund (Citation2021).

5 First six eigenvalues: 3.43 (6.1%), 1.75 (3.1%), 1.54 (2.7%), 1.38 (2.5%), 1.13 (2.0%), 1.0 (1.9%).

6 The third axis opposes the youngest and the oldest citizens, especially in regard to the use of digital media and participation in activities outside the home. The fourth axis contrast middle-aged men and the oldest females on media use, income, education and interest in political and business-related news.

7 For the modalities used to measure the importance of capital in and , the model of the social space was partitationed in three layers for peoples relative positions in this space, first by capital volume (high, middle or low) and capital composition (economic, balanced or cultural fraction). For details, see Hovden and Rosenlund (Citation2021). Social capital was measured by ISEII (lowest, middle or highest third). The questions on peoples' parents asked them to rate, on a five point Likert scale, if they “Grew up in a home … ” 1) “ … with many books, music, art and other cultural interests” and 2) “ … where politics and public issues was often discussed”.

8 The fact that political and public engagement are linked to the same, broad sample of capitals in each generation also appears as an argument for that such engagement is fundamentally rooted in one's position in the social world rather than in an unique “civic” or “public” form of capital, with its own markets and dynamics, that govern engagement.

References

- Bauman, Z. (1999). In search of politics. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

- Beck, U. (1992). Risk society. London: Sage.

- Bennett, T., Savage, M., Silva, E. B., Warde, A., Gayo-Cal, M., & Wright, D. (2009). Culture, class, distinction. London: Routledge.

- Benson, R. (2009). Shaping the public sphere: Habermas and beyond. The American Sociologist, 40(3), 175–197. doi:10.1007/s12108-009-9071-4

- Blekesaune, A., Elvestad, E., & Aalberg, T. (2010). Tuning out the world of news and current affairs–An empirical study of Europe's disconnected citizens. European Sociological Review, 28(1), 110–126. doi:10.1093/esr/jcq051

- Bourdieu, P. (1977). Outline of a theory of practice. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Bourdieu, P. (1984). Distinction: A social critique of the judgement of taste. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

- Bourdieu, P. (1986). The forms of capital. In J. G. Richardson (Ed.), Handbook for theory and research for the sociology of education (pp. 241–258). New York: Greenwood Press.

- Bourdieu, P. (1988). Penser la politique. Actes de la Recherche en Sciences Sociales, 71(1), 2–4.

- Bourdieu, P. (1996). The state nobility. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Bourdieu, P. (2000). Pascalian meditations. Oxford: Polity Press.

- Bourdieu, P. (2001). Das politische feld. Zur kritik der politischen vernuft. Konstanz: UVK.

- Bourdieu, P. (2021). Forms of capital: Lectures at the collège de France, 1983-1984. London: Polity.

- Calhoun, C. (2010). The public sphere in the field of power. Social Science History, 34(3), 301–335. doi:10.1215/01455532-2010-003

- Couldry, N., Livingstone, S. M., & Markham, T. (2007). Media consumption and public engagement: Beyond the presumption of attention. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Crossley, N. (2004). On systematically distorted communication: Bourdieu and the socio-analysis of publics. The Sociological Review, 52(1_suppl), 88–112.

- Dassonneville, R., & Hooghe, M. (2018). Indifference and alienation: Diverging dimensions of electoral dealignment in Europe. Acta Politica, 53(1), 1–23.

- Elster, J. (1986). The market and the forum: Three varieties of political theory. In J. Elster, & A. Hylland (Eds.), Foundations of social choice theory (pp. 104–132). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Esping-Andersen, G. (1990). The three worlds of welfare capitalism. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- EIU (2019). Me too? Political participation, protest and democracy. London: The Economist Intelligence Unit.

- Flanagan, S. C. (1982). Changing values in advanced industrial societies. Comparative Political Studies, 14, 403–444.

- Flemmen, M. P., & Haakestad, H. (2018). Class and politics in twenty-first century Norway: A homology of positions and position-taking. European Societies, 20(3), 401–423.

- Fraser, N. (1992). Rethinking the public sphere: A contribution to the Critique of actually existing democracy. In C. Calhon (Ed.), Habermas and the public sphere (pp. 109–142). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Gaxie, D. (2014). Dispositions, Contexts, and Political Equality. Paper presented at the Deliberative and Participatory Democracy: Theory and Practice, Palo Alto.

- Gaxie, D., Hubé, N., Bigo, D., Blanchard, P., Della Porta, D., Erkkilä, T., … Michel, H. (2014). A political sociology of transnational Europe. Colchester: ECPR Press.

- Giddens, A. (1991). Modernity and self-identity: Self and society in the late modern age. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

- Glevarec, H., & Cibois, P. (2020). Structure and historicity of cultural tastes. Uses of multiple correspondence analysis and Sociological Theory on Age: The case of Music and movies. Cultural Sociology, 15(2), 271–291.

- Goffman, E. (1974). Frame analysis: An essay on the organisation of experience. Boston, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Goldthorpe, J. H. (2001). Class and politics in advanced industrial societies. In T. Clark & S. Lipset (Eds.), The breakdown of class politics: A debate on post-industrial stratification, (pp. 105–120). Baltimore, MD: John Hopkins University Press.

- Greve, B. (2017). Reflecting on Nordic welfare states: Continuity or social change? In P. Kennett & N. Lendvai-Bainton(Eds.), Handbook of European social policy (pp. 248–262). Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Habermas, J. (1970). On systematically distorted communication. Inquiry, 13(3), 205–218.

- Habermas, J. (1974). The public sphere: An encyclopedia article. New German Critique, 1(3), 49–55.

- Habermas, J. (1989). The structural transformation of the public sphere. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Hallin, D. C., & Mancini, P. (2004). Comparing media systems. Three models of media and politics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Harrits, G. S. (2013). Class, culture and politics: On the relevance of a bourdieusian concept of class in political sociology. The Sociological Review, 61(1), 172–202. doi:10.1111/1467-954x.12009

- Heath, A. A. F., Jowell, R. M., & Curtice, J. K. (1985). How britain votes. Oxford: Pergamon.

- Heidar, K., Berntzen, E., & Bakke, E. (2013). Politikk i Europa. Oslo: Universitetsforlaget.

- Hildebrandt, K., & Dalton, R. J. (1978). The New politics: Political change or sunshine politics? In M. Kaase, & K. von Beyme (Eds.), German political studies: Elections and parties (pp. 69–96). London: Sage.

- Hjellbrekke, J., Korsnes, O., Roux, B. L., Rouanet, H., Lebaron, F., & Rosenlund, L. (2007). The Norwegian field of power anno 2000. European Societies, 9(2), 245–273.

- Hovden, J. F., & Rosenlund, L. (2021). Class and everyday media use. The case of Norway. Nordicom Review, 42, 129–149.

- Hölig, S., & Hasebrink, U. (2018). Reuters institute digital news report 2019. Ergebnisse für Deutschland. Arbeitspapiere des HBI, 47.

- Husson, F., Josse, J., & Le, S. (2008). Factominer: An R package for multivariate analysis. Journal of Statistical Software, 25(1), 1–18.

- Inglehart, R. (1977). The silent revolution: Changing values and political styles among the western publics. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Jarness, V., Flemmen, M. P., & Rosenlund, L. (2019). From class politics to classed politics. Sociology, 53(5), 879–899.

- Kantar. (2017). Media use culture & public connection survey. Retrieved from Oslo.

- Le Roux, B., & Rouanet, H. (2010). Multiple correspondence analysis. London: Sage.

- Lippmann, W. (1925). The phantom public. New York: Transaction Publishers.

- Lipset, S. M., & Rokkan, S. (1967). Party systems and voter alignments: Cross-national perspectives (Vol. 7). New York: Free Press.

- Lockwood, D. (1966). Sources of variation in working-class images of society. The Sociological Review, 14(3), 249–267.

- Mannheim, K. (1992). The problems of generations. In C. Jenks (Ed.), The Sociology of childhood (pp. 273–285). London: Brookfield.

- Mannheim, K. (2013). Ideology and utopia. London: Routledge.

- Nærland, T. U., Hovden, J. F., & Moe, H. (2020). Enabling cultural policies? Culture, capabilities, and citizenship. International Journal of Communication, 14, 4055–4074.

- Noûs, C., Robette, N., & Roueff, O. (2021). The multidimensional structure of taste. A cultural legitimacy based on interactions between education, Age, and gender. Biens Symboliques/Symbolic Goods. Revue de Sciences Sociales sur les Arts, la Culture et les Idées, 8. doi:10.4000/bssg.625

- Pagès, J. (2014). Multiple factor analysis by example using R. London: CRC Press.

- Pakulski, J., & Waters, M. (1996). The death of class. London: Sage.

- Piketty, T. (2014). Capital in the 21st century. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Prieur, A., & Savage, M. (2013). Emerging forms of cultural capital. European Societies, 15(2), 246–267. doi:10.1080/14616696.2012.748930

- Putnam, R. D. (2000). Bowling alone: The collapse and revival of American community. New York: Simon & Schuster.

- Robette, N., & Roueff, O. (2019). Cultural domains and class structure: Assessing homologies and cultural legitimacy. In J. Blasius, F. Lebaron, B. Le Roux & A. Schmitz (Eds.), Empirical investigations of social space (pp. 115–134). New York: Springer.

- Rosenlund, L. (2000). Social structures and change. Stavanger: Stavanger University College.

- Savage, M. (2015). Social class in the 21st century. London: Pelican Books.

- Savage, M. (2021). The return of inequality. London: Harvard University Press.

- Schudson, M. (1998). The good citizen: A history of American civic life. New York: Free Press.

- Schudson, M., & Beckerman, G. (2020). “Old” media, “New” media, hybrid media, and the changing character of political participation. In T. Janoski et al. (Ed.), The new handbook of political sociology (pp. 269–289). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Schumpeter, J. (1950). Capitalism, socialism and democracy. New York: Harper and Row.

- Skeggs, B. (2004). Class, self, culture. London: Routledge.

- Smith, A. F. (2020). Political party membership in new democracies. Electoral rules in central and east Europe. Cham: Springer International Publishing.

- Street, J., Inthorn, S., & Scott, M. (2015). From entertainment to citizenship: Politics and popular culture. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

- Syvertsen, T., Moe, H., Enli, G., & Mjøs, O. J. (2014). The media welfare state: Nordic media in the digital Era. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

- Weber, M. (2014). Politics as a vocation. In H. H. Gerth, & C. W. Mills (Eds.), From Max weber: Essays in sociology (pp. 77–128). London: Routledge.

- Wright, E. O. (2005). Approaches to class analysis. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Zerubavel, E. (1999). Social mindscapes: An invitation to cognitive sociology. London: Harvard University Press.