ABSTRACT

Beyond its variable organizational structures, the nation-state is an idea or model – a now-global institution. Since the late nineteenth century, and at an accelerated rate after World War II, the core ideological model of the state has expanded to incorporate authority over, and responsibility for, more aspects of society. We track the worldwide impact of this process by describing and analyzing the rise of eleven relevant cabinet ministries across 190 countries, from 1870 to 2000. We find that early in the period, state penetration occurred in areas seen as central to the collective good – education, welfare, health, statistics, and labor. After the war, areas involving the status of the individual and the rationalization of nature and society were added in global formulations. New ministries focused on women, children, and family life, along with ministries of higher education and the environment. We show that these changes occur globally, rather than mainly as the result of the internal characteristics of countries. The expanded state, beyond its power, reflects structuration under the influence of global models: as the nation-state model expands in associations and discourse at the world level, organizational structuration develops at the national level.

Introduction

‘According to the system of natural liberty, the sovereign has only three duties to attend to … first, the duty of protecting the society from the violence and invasion of other independent societies; secondly, the duty of protecting, so far as possible, every member of the society from the injustice or oppression of every other member of it, or the duty of establishing an exact administration of justice; and thirdly, the duty of erecting and maintaining certain public works and certain public institutions, which it can never be for the interest of any individual, or small number of individuals, to erect and maintain … ’

Adam Smith, The Wealth of Nations (1776), Book IV, Chapter IX

This paper explores the emergence and institutionalization of the ‘social state’ as a global institutional model that developed from the nineteenth century onward. In contrast to realist theories of state expansion, which attribute the development of state structures to local and resource-based factors, we regard the socially interpenetrated state as a world institution in an imagined world society. At a global level, this model of the social state shifts from emphasizing collective/state interests in managing social spheres of the nation-state and toward protecting the status and rights of individual persons in increasingly rationalized conceptions of society. This institutional model of the nation-state, as interpenetrated with individual social life, has spread worldwide in globalized discourse, especially since the second world war, and legitimates a range of organizational structures at the national level.

To describe the emergence and expansion of the social state as a global institutional model, we present longitudinal and cross-national data on the development of ministerial-level state responsibilities from 1870 to 2000, across 190 countries. We examine the adoption of a range of government ministries that focus on eleven areas: children, education, environment, family affairs, health, higher education, human rights, information (census), labor, welfare, and women. As our data show, the overall adoption of these socially oriented government ministries turns out to be surprisingly independent of national levels of development across a broad sample of countries. Instead, the overall process reflects the influence of a globalizing cultural model that depicts the state as responsible for a rationalized society increasingly seen made up of individual persons.

Conceptualizing the social state as an expanding global and cultural idea, over and above the state’s role as a center of power and functionality, helps to explain many dramatic changes of the contemporary period: for example, the expansion of education and organizational structures, sweeping social movements for the rights of more and more people, and foci on scientized environmental and social realities. Our argument builds on existing accounts that focus on the global structuration and diffusion of a few specific ministries over time (e.g. Jang, Citation2000 on science, Ramirez & Ventresca, Citation1992 on education, Frank et al., Citation2000 on the environment); in broadening the scope of government ministries discussed here, our intended theoretical and empirical contribution captures the rise of the social state as a more general and overarching global institutional model. By contrast, most existing research on the rise of the social state has been dominated by ‘realist’ accounts of state expansion, which commonly emphasize the role of idiosyncratic institutional configurations within a handful of countries (see Skocpol & Amenta, Citation1986; Steinmetz, Citation1993; or Orloff, Citation2005 for examples). These visions of nation-states as locally powerful social structures do not help to explain more worldwide and universalistic movements for human empowerment, structuration, and social control.

Background

The nation-state system has come to encompass the world, which is almost entirely organized in entities with claimed and recognized monopoly control over territories and populations (Wimmer & Feinstein, Citation2010). Areas not structured this way are seen as problematic and potentially conflictful (Meyer, Citation1980).

How this occurred is the focus of much social theory.Footnote1 Functionalist and development theories (classically Parsons; critically Wallerstein) emphasize expanded interdependencies as requiring and producing coordination and control: these may be local or supra-local. Power and conflict theories (centrally, Tilly; historically Weber) emphasize expanded resource bases as providing opportunities for exploitive competition: again, the resources may be local or extra-local. The spread of the nation-state can thus be seen as a product of internal or external progress, and/or internally or externally imposed extraction (e.g. Tilly, Citation1985).

These theoretical approaches have limitations. First, functionalist theories have difficulties explaining the substantial disjunctions between claims and what states do in practice. The world is filled with states that can easily be seen as failures (Bromley & Powell, Citation2012; Krasner, Citation1999; March & Olsen, Citation1998). Power and conflict theories face similar explanatory problems: if states are centers of concentrated power, why can’t they put their claims into place? If their claims are reflections of manipulated false consciousness, why do the powers bother, and why do the powerless subscribe? Second, a striking feature of the state system is the formal isomorphism of state structures across societies that vary wildly in their culture and development (for a review, see Meyer et al., Citation1997a). If state structures reflect local functional problems and power structures, why do they look so similar across the world, and expand in worldwide patterns?

The nation-state as a cultural institution

In response to these explanatory problems, cultural and institutional theories of the state emerged to emphasize two important themes. First, the nation-state is importantly a cultural idea, over and above its role as a power center or societal manager (Nettl, Citation1968). Second, over historical time this cultural idea is increasingly organized at the global level (Jackson & Rosberg, Citation1982; Meyer et al., Citation1997a): originally, through Christendom (Butterfield, Citation1949; Bull & Watson, Citation1984), and after the Second World War, the globe. Taken together, these themes suggest expansive global models of what a state is and does. Such models diffuse organizationally – from global institutions (e.g. UNESO) or exemplars in the world stratification system. They also diffuse discursively through professional and other ideologies, such as theories of development or human rights.Footnote2

Accepting these premises calls for an investigation of the cultural and religious sources of the state, the state system, and their expansion. In a classic study, Strayer (Citation1970) discusses the medieval origins of the European state, with the king as a sacral figure and the people as congregants: religious ideas supported both the imagery of a functioning system, and a system in which political power is legitimated as a transcendental authority. Both functionalist theory and conflict models are thus reinforced, as ideology, by religious authority (Mann, Citation1986). This image of cultural authority as a defining feature of the state, over and above its instrumental capacities, appears continuously in accounts of the expansion of the state. For example, Toulmin (Citation1990) argues that the secularization of the Enlightenment produced an expanded vision of the state under the religious-like authority of science. Scott’s (Citation1998) discussion of ‘seeing like a state,’ as well as Evans and colleagues’ (Citation1985) discussion of state autonomy, furthermore, also emphasize cultural perceptions of the state as a bounded purposive actor. This literature often notes the hubris involved, and the unrealistic character of the putatively realist state.

Much of the literature on the nation-state as a global institution is fascinated with the resilience and robustness of the institution. For example, Jackson and Rosberg (Citation1982) invoke the nation-state model to account for the puzzling survival of very weak states ridden with conflicts. Similarly, Meyer (Citation1980) and Meyer et al. (Citation1997a) discuss the state as a global legitimating model and review a line of work that identifies how global institutional frameworks structure state activities in a variety of domains. And Hironaka (Citation2009, Citation2017) calls attention to how the institutionalized nation-state system contributed to widespread civil wars during the postwar period, as well as to the way that states’ concerns about identity claims shape their (often) demonic and supra-rational approaches to war. Such work, acknowledging the embeddedness of the nation-state model in global, society, also points to the interpenetration of this state model with social life.

The state’s social responsibilities and its global expansion

With the Enlightenment and the ‘invention of society’ (Moscovici, Citation1993), the state expanded far beyond its religious, military, and dynastic postures, and came into closer reciprocal relations with real and imagined society. Over the long nineteenth century, states increasingly structured population counts, educational arrangements, basic welfare activities, matters of health and disease, and after the rise of industrial capitalism and its conflicts, labor relations (Mann, Citation1993). These various issues were principally seen as in the collective national and/or state interest: each state was seen in relation to a nation of citizen subjects or participants, and it derived its competitive capacities from these constitutive entities. Thus, throughout this earlier period, education, health care, welfare, and (later) labor conditions were framed less as matters of individual rights; instead, they were seen as efforts to build a strong nation, aid collective prosperity, and expand military power. As part of this process, states produced bureaucratic cabinet ministries and greater regulation for each of these spheres (Steinmetz, Citation1993): for example, education was mainly compulsory, as were matters of public health.

Yet, as citizen rights and responsibilities expanded (Marshall, Citation1950), the dominance of state-centered collective goods lost some legitimacy in the second half of the twentieth century. Indeed, statist and corporatist models of state and society were seen as generating two destructive global wars, human rights disasters, and economic breakdown (Judt 2005), and liberal individualism was celebrated. As a result, after 1945 the charisma of the state as an autonomous and corporate entity rooted in history and tradition weakened, and models of the state emphasized the centrality of rights-bearing individuals. Such rights were asserted on more and more dimensions: age, gender, familial status, and minority or indigenous or ethnic status (Elliott, Citation2007). State responsibilities thus came to include the support and protection of the status of individual persons in society. In parallel, rationalized models of society and its relationship to nature took precedence over older notions of society as a corporate structure embedded in tradition and religion – and state responsibilities for rationalized management and science also expanded (e.g. Drori et al., Citation2003; Meyer et al., Citation1987).

Scholarship on state-society linkages thus suggests long-term changes that reframed such relations: from older notions of framing state-society linkages by collective national or state good to the newer postwar liberal and then neoliberal conceptions of rationalized society made up of individual persons (see Ruggie, Citation1982, Citation1998). At the global level, an institutional model emerges that depicts the state as increasingly responsible for an expanding range of social issues. And this became a notion of a world order substituting for the disastrous statist alternatives. At the national level, this universalized and global vision legitimates (and to some extent requires) the creation of a range of government ministries that manage and structure the issues of individual persons and the wider environment, while it also produces organizational similarities across countries that differ widely in their levels of economic and political development (cf. Grew, Citation1984). The statelessness of world society is a key feature that shapes the patterns observed in the world (Meyer et al. 1997): in particular, the adoption of government ministries in a stateless world society can be contrasted with what one might expect in a world shaped by a world state. In such a world, a top-down bureaucracy would generate differentiated sub-units that develop at the world-level, instead of each nation-state creating its own organizational structures in response to globalizing norms and discourse.

In what follows, we track this historic process, focusing on its impact on state structuration that embodies sweeping global changes by showing the rise of societal cabinet ministries over the period since 1870. The cultural umbrella of a stateless world society creates an organizational agenda for states sheltering under it. After describing our data sources, we provide descriptive evidence and event history analytic models of the temporal changes. We then discuss the macro-level institutional processes that contributed to these developments.

Tracing the social state: Empirical evidence

To track the historical expansion of the state’s social responsibilities, we focus on the formation of governmental ministries that attend to several social domains. We suppose that these events – namely the creation of a ministry for a particular social issue – indicates the state’s increased responsibility for, and commitment to that domain.

Social State Dataset. We coded data on the formation year of government ministries responsible for eleven issues, all related to social welfare and services, broadly defined. The source of our data is The Statesman’s Yearbook, which lists political and administrative information for political entities worldwide. In reviewing each of the Statesman’s Yearbook volumes since 1875, we coded the first event of ministry formation for each issue and each country or territory by marking the year and ministry name. Importantly, we analyzed only those eleven ministries whose title included the key term, or an obvious synonym. A country was coded as having a ministry if a topic was in its title, even if other topics were also included.Footnote3

While the empirical focus on ministerial structuration reflects both state formation and policymaking, we regard this as a ‘high bar’ for the state’s responsibility over, and commitment to, a social issue. Much of a state’s social commitments can be reflected in other forms, such as in its dedication of funds in the national budget to support non-governmental work, or in the creation of governmental yet non-ministerial authorities. However, beyond national tendencies to advance social causes through other state-guided channels, and over and above periodic fluctuations in ministerial composition (e.g. Ryu et al., Citation2020), the founding of governmental ministries is likely to indicate an especially strong expression of state responsibility for a given social issue.

Among the factors that shape the global expansion of the state’s social responsibilities is also, of course, the structuration of the nation-state itself. This requires us to make choices regarding the countries to include in the analyses: while ministry founding data were compiled for 295 countries and territories, which at some point since 1875 were reported in the Statesman’s Yearbook as distinct political entities with governmental structures, we restrict our analyses to the 192 countries that are currently active members of the United Nations.

National and world-level variables. To explore some of the factors that shape the worldwide founding of governmental ministries, we rely on data that account for both national- and world-level processes. For descriptive statistics on the following variables, see Appendices and .

Development. At the national level, conventional arguments about modernization assume that a country’s level of socioeconomic development produces complex societies which require or enable more state expansion (e.g. Flora & Alber, Citation1981). Prior studies that reach back to the early twentieth century often measure a country’s level of economic development using variables like electric power production, iron and steel production, or urbanization (e.g. Boli-Bennett & Meyer, Citation1978; Schofer & Meyer, Citation2005). We include a variable that captures the electric power production in kilowatt hours per capita in a given year (logged), using data from the Cross-National Time-Series Data Archive from 1870 to 2000 (Banks & Wilson, Citation2021).Footnote4

Democracy. At the national level, state expansion is also commonly thought to reflect social demand, and states with stronger domestic democratic processes may face greater pressures to extend their jurisdictions to a wider array of social responsibilities (Haggard & Kaufman, Citation2008). We measure a country’s level of democracy using an index from the Varieties of Democracy dataset that captures the extent to which electoral democracy is achieved in a country in a given year, from 1870 to 2000 (Coppedge et al., Citation2020, p. 42). The index is a composite of other variables collected in the dataset, including measures that identify freedom of association, the existence of free/fair elections, freedom of expression, the extent to which political officials are elected, and the share of the population with the legal right to vote. This variable ranges from 0 to 1, where a 0 indicates no electoral democracy in the country and a 1 indicates that electoral democracy is fully achieved.

Population. At the national level, states with larger populations may expand their administrative structures in order to functionally manage a growing number of people within their borders. We include a variable that captures the population of a country in a given year (logged, to reduce skewness), drawing on data from the Cross-National Time-Series Data Archive from 1870 to 2000 (Banks & Wilson, Citation2021).

Size of cabinet. States that adopt socially oriented ministries may also merely be more bureaucratically differentiated in general, before they adopt a given social ministry, and regardless of the specific issues that cabinet roles in the government focus on. To control for this possibility, we include a variable that captures the number of ministers of cabinet rank in a country’s state in a given year, using data from the Cross-National Time-Series Data Archive from 1870 to 2000 (Banks & Wilson, Citation2021).

Period of independence. Organizational theories of imprinting emphasize that countries are often shaped by the conditions of their founding environments (Stinchcombe, Citation1965). For example, countries that became independent during the postwar period may be more likely to adopt each type of ministry in a shorter period of time after becoming at risk of doing so, given that their institutions are shaped by more dominant conceptions of the social individual in world society. We include a categorical variable in each of our models that tests three periods of independence: prior to 1870, 1871-1945, and post-1945.

Global institutionalization. Our core focus is on the changing character of world society in which these nation-states are embedded. Thus, for each type of ministry we study, we created a global index that captures the institutionalization of the social state model in the world institutional environment over time. Each measure is a composite variable that adds the standardized z-scores for three world-level variables at a given point in time: (1) the number of international non-governmental organizations (recorded by the Union of International Associations: UIA), (2) the number of years since the first country in the world adopted the given ministry, and (3) the cumulative number of countries that had adopted the given ministry by a given year. Appendix includes the Cronbach’s alpha scores for the global indices constructed for each type of ministry (the scores are high, ranging from 0.8–0.98).Footnote5

Methods. For each type of ministry described above, we estimate a series of event history models to capture the associations between the aforementioned national- and world-level factors and the year a country adopts a given type of socially oriented ministry (Allison, Citation2014).Footnote6 Event history analysis is a standard methodological approach for evaluating the factors that shape a duration outcome like the adoption of government ministries; following standard practices, the analyses below estimate constant-rate models, which assume that the baseline hazard rate is constant when independent variables are incorporated into the models (Box-Steffensmeier & Jones, Citation2004). The dependent variable in each of our models is the year a country adopts a particular ministry, and the coefficients in our analyses capture the influence of our national- and world-level variables on the hazard rate of ministry adoption.

We include countries in our analyses when they become independent; for a handful of countries that adopt a given ministry before they become independent, we identify the country’s year of independence as its year of adoption for that ministry. In these analyses, once a country has adopted a ministry, the country exits the risk set; social ministries may shift their titles or category schemes, but countries very rarely eliminate an entire ministry. The time span for each of the ministries analyzed starts in the year ministry m is first adopted anywhere in the world, which reflects our assumption that countries become ‘at risk’ of adopting ministry m during this time period. For example, the United Kingdom is the first independent country in our dataset to adopt a ministry of welfare, in 1870; the time period of our analyses for this dependent variable therefore begins in 1870, when countries are assumed to become ‘at risk’ of adopting a ministry of welfare. All independent and control variables are also lagged by one year, to ensure that the underlying social processes measured in our independent and control variables precedes the outcome.

Findings: The global structuration of the social state

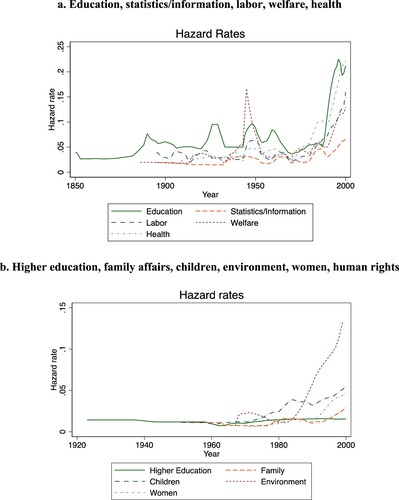

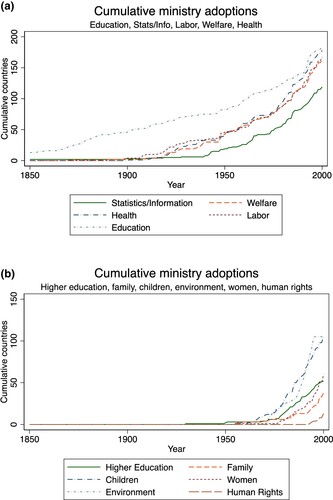

traces historical changes and reports the growing proportions of extant countries with socially oriented ministries over the time period. It also reports data for older and newer countries separately, to show that newer countries differ little from older ones: world time turns out to be a crucial factor, rather than national age. demonstrates that socially oriented ministries grow dramatically over time, especially in the very recent periods of global liberal and neoliberal dominance. They are founded in a rough global sequence: Education, Welfare, Labor, Statistics/Information, and Health begin their careers earlier, while Higher education, Family affairs, Children, Environment, Women, and Human rights develop very recently. The same trends characterize both older countries and the newer ones formed during the period. Correspondingly, a and b shows the same information graphically: the fraction of countries increased steadily over time for all ministries covered, and more dramatically in recent postwar periods. In analyses shown in Appendix , hazard rates of adoption of all the ministries analyzed climb dramatically in the most recent decades.

Figure 1. Cumulative adoption of socially oriented ministries. (a) Education, Stats/Info, Labor, Welfare, Health. Note: Over this time period, the number of countries in the world also expands. To account for this, also captures similar trends for each ministry type, measured as the proportion of countries that have adopted each ministry at specific time points. (b) Higher education, Family affairs, Children, Environment, Women, Human rights.

Table 1. Percentage of countries with particular social ministries, by year.

Importantly, as expressed in the division between a and b, we see a differentiation between the ‘classical’ cluster of social issue ministries (Education, Labor, Welfare, Health), which were not only founded earlier and are currently at a high share of countries, and the newer social issue ministries (Higher education, Family affairs, Children, Environment, Women, and Human rights), which emerged in the post- World War II era. These patterns shape the worldwide diffusion and the expansion of the scope of the state’s social responsibilities; we describe their historical trajectories in more detail below.

In and , we turn to analyses of the factors that predict ministry adoption, using a consistent set of constant-rate event history analyses of the initial adoption of each ministry by country. The results of these analyses demonstrate that the adoption of all the social ministries consistently follows global patterns. Our global indices show substantial and consistently significant effects; these independent variables reflect the institutionalization of particular ministerial functions through the whole system. Ministries become fashionable in global ideologies and models, and as they do, the rate of national adoption increases.

Table 2a. Constant-rate event history analyses of ministry adoption.

Table 2b. Constant-rate event history analyses of ministry adoption.

Contrary to realist theories, furthermore, a country’s electric power production shows weak and inconsistent effects across the board; when this variable does have a significant effect on the hazard rate of ministry adoption, the coefficients are in the opposite direction of what theories would expect (i.e. negative, instead of positive). Democratization and a country’s cabinet size are sometimes positively and significantly associated with the hazard rate of ministry adoption for the ministries in our analyses. Interestingly, being a country that gained independence post-1945 is positively and significantly associated with the hazard rate of adoption for earlier ministries like labor, welfare, health, and statistics/information. Given that the first adoption of these ministries in the world occurred early in the twentieth century, it is unsurprising that the newest countries take less time to adopt them after entering the risk set. These countries are founded in a time period where these types of social ministries were increasingly institutionalized, in global institutional models of the state, as part of a state’s organizational structure; in this context, newly independent countries would take it for granted that incorporating these structures into the state is a core component of legitimate nation-state identity.Footnote7

Overall, these patterns – across subject-specific ministries, across countries, and over time – illustrate the global institutionalization of the social state. The overall process also illustrates the historic transformation of the social state, and the factors that relate to the founding of ministries over time.Footnote8 The following sections describe the eras of transformation of the social state, by periodizing its expansion and detailing the patterns specific to each historic era and the socially oriented ministries whose foundings mark it. We identify two clusters of ministries, and thus two periods, for the ‘socialization’ of the state model: from the late nineteenth century to mid-twentieth century, and from the mid-twentieth century until the year 2000. As we describe below, these two periods trace two aspects of the social state: initially characterized by secularization and organization around the collective good, and subsequently dominated by a more globalized story of the empowered individual in a rationalized society.

The focus on the management of ‘society'

Until the nineteenth century, the Western European state was primarily concerned with its internal and external power and finances, and states were thus relatively weakly linked to society. Instead, social matters tended to be managed by the church, which mainly handled education, medicine, charity, familial relations, as well as the recording of births, deaths, and population. But as the ideals of the Enlightenment influenced modern states to become increasingly focused on society as an object of management and control, religious systems lost authority, and the state itself began to become more attentive to social matters. This was especially visible in countries like post-revolutionary France and the United States, but the same process occurred everywhere (e.g. Poggi, Citation1978: Ch. 6).

With the overall declining authority of religious systems, social issues that were previously organized by the church were pulled into the state. For example, states began to keep records – and the institution of the census diffused worldwide (Ventresca, Citation1995). Matters of crime and punishment were regularized and intensively legalized: these processes increasingly affected the lives of individuals, but individuals were seen as entities that comprised an abstract body politic; the issues were less about managing their private good or ill. As part of this process, ministries of information or statistics developed to track demographic changes and movements, starting in 1899 in the US (see and Model 1 in ).

The formalization of a cabinet-level, state-led sphere that organizes censuses, statistics, and information was also reinforced by emergence of this societal issue as (a) a global concern, and (b) a basis for international and transnational activity. Among such global hubs for action is, for example, the International Statistical Institute (ISI), which was formally founded in 1885 after a series of international statistical congresses organized by leading statisticians (International Statistical Institute, Citation2021). Importantly, from its founding statutes and through its persistent resistance to being absorbed into the League of Nations or United Nations agencies, the ISI set as its goal to influence governmental statistical agencies; it did so by facilitating the international standardization of statistical definitions and data collection. The cultural framework of the world polity constituted the background for the worldwide transformation of state operations, here regarding societal information.

Ministries of education also appeared in the nineteenth century (Ramirez & Ventresca, Citation1992). Education was a main way in which the state reached down to directly affect the individual, and it was seen as directly functioning for the public good. While initially intertwined with state church, as in the first instance in our data in Norway in 1814, education increasingly became the engine for secularizing an older system in which the religious salvation of the people was a state responsibility, with education replacing sin with ignorance; its purpose was to render the population loyal and competent citizens (Weber, Citation1976). The penetration of society by the schooled state was thus originally a matter of social control – as a public good more than as a matter of citizen empowerment (Maynes, Citation1985). Only later in the twentieth century did it become a right of every human, to be supported by all other humans (Baker, Citation2014). Ministries of education diffused through a process shaped by norms that began globalizing in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century with a series of international conferences; this eventually crystallized with the formation of an International Bureau of Education in 1925. The rate of formation of ministries of education increased dramatically over time, reflecting the importance of authoritative global models.

As the state continued to expand its social responsibilities toward the collective good, ministries of health, labor, and welfare were established. The health of the population – which was seen as vital to the strength of the state – went through a process of expansion similar to education (Rosen, Citation1958). a show the corresponding rise of ministries of health around the world; as also shows, the founding of ministries of health is a product of global forces, likely aided by medical developments (Offit, Citation2021). And just as with education, health drifted from being a collective good to gradually becoming a human right of individuals. This shift was increasingly certified over time, from the human rights declarations around the foundation of the United Nations to the increasingly intense international formulations later in time (e.g. through the expanded World Health Organization from 1948; see Inoue & Drori, Citation2006).

With both education and health, state involvement reflected notions of the collective good more than the rights and welfare of individuals in society. But through the long nineteenth century, concerns with the management of society reached further. Two dimensions became of increasing interest. First, with urbanization and industrialization in the global core, matters of the welfare of people moved from kinship concerns, and public institutions became more and more central (see ); in the process, pension systems and formalized welfare arrangements arose (Orloff, Citation1993). These were matters of the collective good as much as they were of individual rights, which became central later: social order was at issue. Second, with industrialization in the core, the ‘social question’ became urgent – the potential for class conflict to disrupt society and the state. With long-term democratization as a trend and/or a threat (Marshall, Citation1950), the management of the urban labor force that was increasingly organized became a concern: especially as it was expressed through rising socialist movements around the world (e.g. Silver, Citation2003). This advanced the founding of labor ministries (). Likewise, the founding of the International Labor Organization (ILO) in 1919 was a direct global response to such rising social concerns, providing a global frame that legitimized national action (van Daele, Citation2005). In response to these changes, ministries of welfare and labor appeared, not only in global industrial centers, but as reflections of the emerging form of the new and proper state.

By the middle of the twentieth century, these patterns of founding of societal cabinet ministries meant that a large share of then-independent states added these societal concerns to the scope of the state’s responsibilities. With that, a secular and socially oriented model of the state emerged and diffused worldwide, carried forward by global forces. By the end of this period, the state acquired more authority over, and responsibility for, information, education, health, welfare and labor.

The state under the rationalized liberal order

In all the cases discussed above, early state expansion tended to intensify in the postwar period: the public order of the polity and economy came under regularization (and representation). But the more globalized liberal world of the postwar era generated much broader arenas of interpenetration of society and state in an expanded model. Two broad changes were shaped by globalizing norms: expanded individualism and the rationalization of society and nature.

Expanded individualism under global norms. The aftermath of World War II, with the defeat of fascism, the marginalization of communism, and the dominance of the liberal United States, produced a global cultural emphasis on the rights of the individual in liberal polities, markets, and societies (Elliott, Citation2007). This involved, as our data show, an increased emphasis on health, education, welfare, and labor, now seen as both public responsibilities and individual rights. Indeed, instead of having a public economy and a distinct private sector of family and community life, every aspect of society could come under public scrutiny, and every aspect of the public order could be subject to the rights of former private life. With the end of communism around 1990, this focus on the expanded and empowered individual led to a further intensification of rights and a penetration of the formerly private space of social, familial, and sexual space. And beyond family life, the happiness of individuals – in solo, apart from any more collective structure – came to be a public focus (Kislev, Citation2018). In any event, new ministries appeared, concerned with the rights of children, women, families, and people of ‘different’ sexualities. And former ministries were realigned to carry the new emphases on individuals: for example, former ministries regulating the status of minorities now expanded as guarding individual rights.

Thus, the post-World War II period is marked by the founding of ministries of family affairs, children, environment, women, human rights, and this shift intensified in the global neoliberal period following the 1980s. These new ministries appeared in old and developed polities, but also in the newest and least developed ones. The founding of ministries for family affairs () started with Germany in 1955, followed by Norway in 1956. The structuration of family-related ministries builds on the 1947 founding of the World Family Organization, which calls for the respect of the rights, responsibilities, and capacities of the family (World Family Organization, Citation2021), as well as on the densifying network of international organizations and associations of family-related professions: from family law, through family business, to family medicine and therapy. The founding of ministries for children’s affairs (), starting with New Zealand in 1955 and followed by Germany in 1958, builds on the likewise densifying network of international action on children’s care, health, and later also rights (e.g. Schaub et al., Citation2017). The founding of ministries of women’s affairs (), starting with New Zealand in 1955 and followed in the mid-1970s by Iran, Papua New Guinea, Ivory Coast, and Bangladesh, was carried forward by the global promotion of women’s integration into the public sphere (Berkovitch, Citation1999). And the founding of ministries of human rights (see b), started with Mali in 1993 and reached 19 such ministries worldwide by 2002; while absent from the associational models in due to insufficient data, this process is surely associated with the intensifying organization of human rights agenda and growing state commitment to global models of human rights protection.Footnote9

| 2. | The rationalization of society and nature under global norms. The expanded individual of postwar liberalism could also engage in purposive and perhaps rational action. This reflected the reconstruction of society and its natural context on a more rationalized and scientized basis: market-like arrangements must be constructed in economy, polity (democracy), social life (e.g. free choice of association and marriage) and culture (language and religion). | ||||

With the rise of what subsequently was labeled ‘knowledge society’, we see the founding of not only ministries of science (Jang, Citation2000), but also ministries of higher education managing schooled institutions. Famously, the university expands worldwide as a locus of expanded information and social control (Frank & Meyer, Citation2020). The cabinets of national states expand to include regulation and incorporation of higher education as a value: the founding of ministries for higher education starts in Ecuador in 1930 and is followed in 1950 and 1951 by Hungary and Poland. depicts these patterns, confirming yet again that these effects occur in new and less developed societies as well as old and rich ones. Interestingly, the founding of ministries of statistics/information, which started far earlier but diffused slowly (Ventresca, Citation1995), also surged during this period.

The foundings of ministries of the environment (), starting in 1971 with the United Kingdom, are driven by the intensity of international concern about the natural environment and national action towards its utilization and then preservation (Meyer et al., Citation1997b; Frank et al., Citation2000). We find a growing number of ministries over the second half of the twentieth century, a negative association of such founding patterns with resource and developmental status, and strong and consistent associations with world society. For each of these social domains, we can observe the associated international organizations and their action worldwide: this obviously affects national-level structuration.

Concluding comments: The global socialization of the state

Our analysis covers the worldwide process of structuration of ministries across eleven social spheres since the late nineteenth century, showing the expansion of the social responsibilities of the state. Sovereign states have always exercised and/or claimed power over individual subjects or citizens, but the extent to which they became involved in social life and in what fields the state was to intervene have progressively expanded. Furthermore, the periodization of the global process of ministry founding reveals not only the expansion of the socially oriented state but also its transition from the corporatist or statist form of state-society relations, which subsequently linger in the form of the welfare state, into the state that sets the individual’s life-course as a collective concern.

Our goal in this paper was to draw on data that cover a global sample of countries across a wide range of ministries to emphasize the development of the social state as an abstract and global institutional model. In our analyses, we see that the foundings of these eleven types of ministries are little associated with resources and developmental conditions (electric power production and democracy) on an overall basis; instead these processes are strongly and consistently related with the construction of an institutional model in world society. Whereas earlier literature on broad social transformations of this scale tends to imagine a more linear societal progress, with emphasis on economic change and industrialization, we call attention to the dramatic macro-cultural shifts captured by Ruggie’s (Citation1982, p. 1998) typology. Therefore, while various analytic periodizations point to similar inflections points and acknowledge the transformative importance of the nineteenth century and World War II, our focus is on these points as pivotal in the constitution of an imagined global cultural model of the state’s role in society. Confirming the abstract and general nature of this model regarding state-society relations, we see similar patterns of founding and of association across all eleven social spheres over time.Footnote10

The post-Enlightenment pattern depicted in state ministries shows a continuing expansion of both states and public society – and their increasing merger over the whole period. This involves the recognition of increasing aspects of society as having public value, and increasing aspects of the state as having private value. As one indicator, for example, more and more parts of society come to be counted, monetarized, and included in the Gross Domestic Product, now constructed for every country worldwide (Schofer et al., Citation2021). As another indicator, the recognition of the unique value of variations among individual and across differentiated society might produce the formation an expansion of ministries of diversity in the future, replacing the older and narrower paternalistic state responsibility for minorities and other marginalized individuals. For example, in January 2018, the UK government announced the founding of the world’s first Ministry of Loneliness (United Kingdom Government, Citation2018). The new Minister charged with charting the scope of this new governmental domain cited alarming trends of personal isolation and related despair, also evident in other countries, and pointed to the breakdown of family life, intergenerational gaps, migration, and mediated communication as causes of the loneliness crisis. In February 2021, Japan followed with the founding of a similar cabinet ministry, specifically targeting the need to alleviate loneliness among the elderly, women, and the underemployed (Kawaguchi, Citation2021). The global COVID-19 pandemic, which required quarantine and social distancing regulations worldwide, highlighted these concerns regarding isolation and loneliness, spurring international organizations – mainly the World Health Organization (WHO) – to add loneliness to their policy initiatives for securing or promoting public and mental health (World Health Organization, Citation2021). Together, these examples signal yet another previously private matter that is redefined as coming under the responsibility and jurisdiction of the state, as a global concern activated through the world polity.

By some accounts, the world we have depicted is declining in preference for post-liberal populisms and authoritarianisms (e.g. Furuta et al., Citation2023). Models of world society, in more recent periods, have increasingly stressed a variety of particularisms – geopolitical, nationalist, regionalist, localist, religious – more than ‘globalization.’ If these shifts continue, it is interesting to speculate whether the linkage between state and society will change – and perhaps even decline. For example, state responsibilities might shift toward more traditional forms of social control and collective construction rather than universalistic constructions of individual empowerment and the rationalization of nature and society. In this scenario, cabinets might continue to expand, but with reduced and more marginal authority, and the standing and importance of their ministries might decline.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 For reviews, see Thomas & Meyer (Citation1984) or Spruyt (Citation2002).

2 Lines of thought emphasizing simple isomorphic domination are naïve: for example, the dominant United States, certainly no leader in state organizational development, has been discursively influential but not copied much as an organized state.

3 For example, we included ministries of education in the analysis because the term ‘education’ was consistently included in the title of the ministry and ministries of ‘labor’ and ‘children’ even if the terms were ‘employment’ or ‘youth’, respectively. We excluded ministries of ‘minorities’ and ‘religion’ from the analysis because the associated terms varied greatly in meaning from country to country, depending on historical circumstances. By the year 2000, only 9 percent of countries have a ministry of minorities (first adoption occurred in 1899), and 29 percent of countries have a ministry of religion (first adoption occurred in 1870). Minorities ministries were typically about managing intergroup relations (rather than the individual), and religious ministries were similarly about collective management (e.g., of state churches).

4 In supplementary analyses, we drew on data from Banks and Wilson (Citation2021) and the Maddison Project (Bolt & van Zanden, Citation2020) to test three alternative measures of a country’s level of economic development: (1) Urbanization, measured as the percentage of a country’s total population that lived in an urban area in a given year, (2) Iron and steel production per capita in a given year (logged), and (3) A historical measure of GDP per capita (logged). Urbanization and iron/steel production are only slightly correlated with electric power production per capita (r = 0.34 for iron and steel production, and r = 0.19 for urbanization), while the Maddison Project’s measure of GDP per capita is highly correlated with electric power production (r = 0.58). The results of our analytic models for all of these alternative measures are nearly identical to those we present below (i.e., the coefficients for each of these indicators of economic development are typically non-significant, and the other coefficients are virtually unchanged in direction and significance). We opted to use electric power production in our models because its coverage was highest for the number of countries and time period of our analyses.

5 Each of these variables that comprises our index captures the same underlying concept of the global institutionalization of an abstract model of the social state, which is reflected in our inter-reliability scores. For example, the number of international non-governmental organizations in the world is a commonly used measure of the structuration of world-level norms and institutional models (Boli & Thomas, Citation1999), while the cumulative number of adopters in the world at a given time point reflects the strength of normative pressures in the global institutional environment for countries to adopt a ministry (e.g., Ramirez et al., Citation1997). The number of years since the first country in the world adopted a given ministry reflects the growth and consolidation of the social state model in world society, particularly in the absence of alternative world-level institutional models (Meyer et al., Citation1997a). When we tested each variable for each type of ministry in a series of separate analyses (not shown), the results are very similar to those reported below.

6 Models are not estimated for education ministries in order to avoid left-censoring issues, a common problem that biases results in event history analysis: countries become ‘at risk’ of adopting education ministries starting from the 1810s, while data on our national-level covariates are only available starting from the 1870s. We also do not estimate event history models for human rights ministry adoptions, because there are too few events that occur during the time span of our analyses.

7 It is worth noting here that our results from identify the overall rate of ministry adoption at different points in time, while the dependent variables in and identify a duration outcome (time-to-event for a country to adopt a ministry, once it becomes at risk).

8 In additional analyses, we assessed several variables to test the robustness of our models and other possible arguments. First, we tested whether a country’s colonial history or region influenced the adoption of each type of ministry, given that we might expect the diffusion process to be structure at sub-global levels. We did not find any significant effects of these variables in the models we estimated, nor did they change the results any of the other variables in our models. Second, we tested whether the effects of country-specific economic or political processes on ministry adoption are time-dependent (cf. Tolbert & Zucker, Citation1983), by conducting a split-sample analysis of our models between ‘early’ and ‘late’ periods. We did not consistently find that the coefficients for our variables that reflect economic and political processes were significant in earlier time periods. As our argument emphasizes, the globalizing model of the nation-state creates institutional conditions that enable these ministries to be adopted, rather than identifying which specific countries they will be adopted in first; given the emphasis on cultural conditions (rather than power or hegemony) in our argument, it is not surprising that this variable is insignificant, nor that the US is a relatively late adopter for each of these ministries in our data. Finally, we examined whether a country’s embeddedness in world society, measured as its memberships in international non-governmental organizations (logged), influenced the adoption of each social ministry. While this variable was often positively and significantly associated with the hazard rate of ministry adoption for the eleven ministries in our analyses, the results were not always consistent. We found similar results when we examined whether a country’s membership in international governmental organizations (logged) shaped the hazard rate of adoption for each ministry (drawing on data from Pevehouse et al., Citation2020). Both variables are highly correlated with our global indices (r = 0.6 or higher for both INGO’s and IGO’s, more than half the time), which created issues of multicollinearity in our analyses.

9 For example, Koo & Ramirez (Citation2009) show the rapid adoption of human rights commissions and ombudsmen in countries around in the world, particularly from the 1990s, and how diffusion of these structures is shaped by embeddedness in world society. At a global level, the abstract universalism of the notion of human rights locates the individual in a broad moral universe: this leads to court-like arrangements that develop at the state-level (e.g., ombudsmen), rather than cabinet offices. Specific rights to domains like education, welfare, or labor protection are more easily organized and managed through organizations.

10 Future research, could also use similar data to explore the societal effects of these organizational structures on a variety of outcomes (e.g., social inequalities, political structure, educational outcomes, or development). Our argument suggests that the adoption of social ministries has diffuse (rather than tightly coupled) effects, given that it contributes to an institutional environment that diffusely shapes norms, expectations, and attitudes about many societal domains (Hironaka, Citation2014).

References

- Adams, J., Clemens, E., & Orloff, A. (2005). Remaking modernity. Duke University Press.

- Aklin, M., & Urpelainen, J. (2014). The global spread of environmental ministries: Domestic–international interactions. International Studies Quarterly, 58(4), 764–780. https://doi.org/10.1111/isqu.12119

- Allison, P. (2014). Event history analysis: Regression for longitudinal event data (2nd ed.). SAGE Publications.

- Baker, D. (2014). The schooled society: The educational transformation of global culture. Stanford University Press.

- Banks, A., & Wilson, K. (2021). Cross-national time-series data archive. Databanks International. Jerusalem, Israel. Available online at: <https://www.cntsdata.com/>.

- Berkovitch, N. (1999). From motherhood to citizenship: Women's rights and international organizations. Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Boli, J., & Thomas, G. (1999). Constructing world culture: International nongovernmental organizations since 1875. Stanford University Press.

- Boli-Bennett, J., & Meyer, J. (1978). The ideology of childhood and the state: Rules distinguishing children in national constitutions, 1870–1970. American Sociological Review, 43(6), 797–812. https://doi.org/10.2307/2094622

- Bolt, J., & van Zanden, J. L. (2020). “Maddison style estimates of the evolution of the world economy: A new 2020 update.” Maddison Project Database. Available online at: https://www.rug.nl/ggdc/historicaldevelopment/maddison/releases/maddison-project-database-2020.

- Box-Steffensmeier, J., & Jones, B. (2004). Event history modeling. Cambridge University Press.

- Bromley, P., & Powell, W. (2012). From smoke and mirrors to walking the talk: Decoupling in the contemporary world. The Academic of Management Annals, 6(1), 483–530.

- Bull, H., & Watson, A. (1984). The expansion of international society. Oxford University Press.

- Butterfield, H. (1949). Christianity and history. Bell.

- Coppedge, M., et al. (2020). “V-Dem Dataset v10” Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) Project. https://doi.org/10.23696/vdemds20.

- Drori, G., Meyer, J., Ramirez, F., & Schofer, E. (2003). Science in the modern world polity. Stanford University Press.

- Elliott, M. (2007). Human rights and the triumph of the individual in world culture. Cultural Sociology, 1(3), 343–363.

- Evans, P., Skocpol, T., & Rueschemeyer, D. (1985). Bringing the state back in. Cambridge University Press.

- Finnemore, M. (1993). International organizations as teachers of norms: The United Nations educational, scientific, and cultural organization and science policy. International Organization, 47(4), 565–597.

- Flora, P., & Alber, J. (1981). Modernization, democratization, and the development of welfare states in Western Europe. In P. Flora, & A. Heidenheimer (Eds.), The development of welfare states in Europe and America (pp. 37–80). Transaction Publishers.

- Frank, D. J., Hironaka, A., & Schofer, E. (2000). The nation-state and the natural environment over the twentieth century. American Sociological Review, 65(1), 96–116.

- Frank, D. J., & Meyer, J. (2020). The university and the global knowledge society. Princeton University Press.

- Furuta, J., Meyer, J., & Bromley, P. (2023). “Education in a Post-Liberal World Society.” In Mattei, P., X. Dumay, E. Mangez, and J. Behrend (eds) Oxford Handbook on Education and Globalization. Oxford University Press, pp. 96–118.

- Grew, R. (1984). The nineteenth century European state. In C. Bright, & S. Harding (Eds.), Statemaking and social movements (pp. 83–120). University of Michigan Press.

- Haggard, S., & Kaufman, R. (2008). Development, democracy, and welfare states: Latin America, east Asia, and Eastern Europe. Princeton University Press.

- Hironaka, A. (2009). Neverending wars. Harvard University Press.

- Hironaka, A. (2014). Greening the globe: World society and environmental change. Cambridge University Press.

- Hironaka, A. (2017). Tokens of power: Rethinking war. Cambridge University Press.

- Inoue, K., & Drori, G. (2006). The global institutionalization of health as a social concern. International Sociology, 21(2), 199–219.

- International Statistical Institute. (2021). “History of the International Statistical Institute.” Accessed 24 August 2021. https://www.isi-web.org/.

- Jackson, R., & Rosberg, C. (1982). Why Africa’s weak states persist: The empirical and the juridical in statehood. World Politics, 35(1), 1–24.

- Jang, Y. S. (2000). The worldwide founding of ministries of science and technology, 1950–1990. Sociological Perspectives, 43(2), 247–270.

- Kawaguchi, S. (2021). “Japan’s Minister of Loneliness in Global Spotlight as Media Seeks Interviews.” The Mainichi. Accessed 24 August 2021. Available online at: https://mainichi.jp/english/articles/20210514/p2a/00m/0na/051000c.

- Kim, J.-S. (2006). The normative construction of modern state systems: Educational ministries and laws, 1800–2000. In D. Baker, & A. Wiseman (Eds), The impact of comparative education research on institutional theory. Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

- Kislev, E. (2018). Happiness, post-materialist values, and the unmarried. Journal of Happiness Studies, 19(8), 2243–2265.

- Koo, J.-W., & Ramirez, F. (2009). National incorporation of global human rights: Worldwide expansion of national human rights institutions, 1966–2004. Social Forces, 87(3), 1321–1353.

- Krasner, S. (1999). Sovereignty. Princeton University Press.

- Mann, M. (1986). The sources of social power, volume 1. Cambridge University Press.

- Mann, M. (1993). The sources of social power, volume 2: The rise of classes and nation-states, 1760–1914. Cambridge University Press.

- March, J., & Olsen, J. (1998). The institutional dynamics of international political orders. International Organization, 52(4), 943–969.

- Marshall, T. (1950). Citizenship and social class. Pluto Press.

- Maynes, M. J. (1985). Schooling in Western Europe: A social history. SUNY Press.

- Meyer, J., Boli, J., & Thomas, G. (1987). Ontology and rationalization in the western cultural account. In G. Thomas, J. Meyer, F. Ramirez, & J. Boli (Eds), Institutional structure: Constituting state, society, and the individual. Sage.

- Meyer, J. W. (1980). The world polity and the authority of the nation-state. In Bergesen (Ed.), Studies of the modern world-system (pp. 109–137). Academic Press.

- Meyer, J. W., Boli, J., Thomas, G. M., & Ramirez, F. O. (1997a). World society and the nation-state. American Journal of Sociology, 103(1), 144–181.

- Meyer, J. W., Frank, D. J., Hironaka, A., Schofer, E., & Tuma, N. B. (1997b). The structuring of a world environmental regime, 1870–1990. International Organization, 51(4), 623–651.

- Moscovici, S. (1993). The invention of society: Psychological explanations for social phenomena. Polity Press.

- Nettl, J. (1968). The state as a conceptual variable. World Politics, 20(4), 559–592.

- Offit, P. (2021). You bet your life. Basic Books.

- Orloff, A. (1993). The politics of pensions: A comparative analysis of Britain, Canada, and the United States, 1880s–1940. University of Wisconsin Press.

- Orloff, A. (2005). Social provision and regulation: Theories of states, social policies, and modernity. In J. Adams, E. Clemens, & A. Orloff (Eds), Remaking modernity (pp. 190–224). Duke University Press.

- Palgrave McMillan. (1870–2000). The statesman’s yearbook (various editions). Palgrave Mcmillan.

- Pevehouse, J., Nordstrom, T., McManus, R., & Jamison, A. (2020). Tracking organizations in the world: The correlates of War IGO version 3.0 datasets. Journal of Peace Research, 57(3), 492–503.

- Poggi, G. (1978). The development of the modern state. Stanford University Press.

- Ramirez, F., Soysal, Y., & Shanahan, S. (1997). The changing logic of political citizenship: Cross-national acquisition of women’s suffrage rights, 1890–1990. American Sociological Review, 62(5), 735–745.

- Ramirez, F., & Ventresca, M. (1992). Building the institution of mass schooling: Isomorphism in the modern world. In B. Fuller, & R. Rubinson (Eds), The political construction of education (pp. 47–59). Praeger.

- Rosen, G. (1958). A history of public health. MD Publications.

- Ruggie, J. (1982). International regimes, transactions, and change: Embedded liberalism in the post-war economic order. International Organization, 36(2), 379–415.

- Ruggie, J. (1998). Globalization and the embedded liberalism compromise: The end of an era? In W. Streeck (Ed.), Internationale Wirtschaft, Nationale Demokratie. Campus Verlag.

- Ryu, L., Jae Moon, M., & Yang, J. (2020). The politics of government reorganizations: Evidence from 30 OECD countries, 1980–2014. Governance, 33(4), 935–951.

- Schaub, M., Henck, A., & Baker, D. (2017). The globalized ‘whole child’: Cultural understandings of children and childhood in multilateral Aid development policy, 1940–2010. Comparative Education Review, 61(2), 298–326.

- Schofer, E., & Meyer, J. (2005). The worldwide expansion of higher education in the twentieth century. American Sociological Review, 70(6), 898–920.

- Schofer, E., Ramirez, F., & Meyer, J. W. (2021). The societal consequences of higher education. Sociology of Education, 94(1), 1–19.

- Scott, J. (1998). Seeing like a state. Yale University Press.

- Silver, B. (2003). Forces of labor: Workers’ movements and globalization since 1870. Cambridge University Press.

- Skocpol, T., & Amenta, E. (1986). States and social policies. Annual Review of Sociology, 12, 131–157.

- Spruyt, H. (2002). The origin, development, and possible decline of the modern nation-state. Annual Review of Political Science, 5, 127–149.

- Steinmetz, G. (1993). Regulating the social. Princeton University Press.

- Stinchcombe, A. (1965). Social structure and organizations. In J. March (Ed.), Handbook of organizations (pp. 142–193). Rand McNally.

- Strayer, J. (1970). On the medieval origins of the state. Princeton University Press.

- Thomas, G., & Meyer, J. (1984). The expansion of the state. Annual Review of Sociology, 10(1), 461–482.

- Tilly, C. (1985). War making and state making as organized crime. In P. Evans, T. Skocpol, & D. Rueschemeyer (Eds), Bringing the state back in (pp. 169–191). Cambridge University Press.

- Tolbert, P., & Zucker, L. (1983). Institutional sources of change in the formal structure of organizations: The diffusion of civil service reform, 1880–1935. Administrative Science Quarterly, 28(1), 22–39.

- Toulmin, S. (1990). Cosmopolis: The hidden agenda of modernity. Chicago University Press.

- Union of International Associations (UIA). (Various years). Yearbook of international organizations. UIA and K.G. Saur Verlag.

- United Kingdom Government. (2018). “PM Launches Government’s First Loneliness Strategy.” Crown copyright. Accessed 24 August 2021. Available online at: <https://www.gov.uk/government/news/pm-launches-governments-first-loneliness-strategy>.

- van Daele, J. (2005). Engineering social peace: Networks, ideas, and the founding of the international labour organization. International Review of Social History, 50(3), 435–466.

- Ventresca, M. (1995). When states count: Institutional and political dynamics in modern census establishment, 1800–1993. Stanford University Dissertation.

- Weber, E. (1976). Peasants into frenchmen. Stanford University Press.

- Weber, M. (1978). Economy and society. University of California Press.

- Wimmer, A., & Feinstein, Y. (2010). The rise of the nation-state around the world, 1816–2001. American Sociological Review, 75(5), 764–790.

- World Family Organization. (2021). “History of the World Family Organization.” Accessed 24 August 2021. Available online at: <http://worldfamilyorganization.com/>.

- World Health Organization. (2021). “Social isolation and loneliness among older people.” Advocacy brief. Available online at: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240030749+.

Appendix A1

Hazard rate, adoption of socially oriented ministries

Appendix A2. Pearson’s correlation coefficients of ministry adoption, year 2000 (n = 189).

Appendix A3. Descriptive statistics of independent and control variables (all years pooled).

Appendix A4. Cronbach's alpha scores for global indices (all years pooled).