David Wilson. New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan, 2018. xiii and 208 pp., illustrations. $99.99 paper (ISBN 978-3-319-88996-2), $99.99 cloth (ISBN 978-3-319-70817-1), $79.00 electronic (ISBN 978-3-319-70818-8).

David Wilson's most recent book examines the conflict surrounding the latest redevelopment frontier in Chicago: the city's South Side. Like Chicago, many cities across the world are experiencing sweeping redevelopment that profoundly changes not only the city's appearance, but also its social fabric. Following on from Smith's gentrification frontier, Wilson refers to this process as a new redevelopment machine: one of tyranny and fear. Wilson's idea is not a completely new one, but it is a very important theme throughout his academic work. He has already undertaken an in-depth analysis of urban redevelopment in cities such as Indianapolis, Cleveland, Cincinnati, and Flint, and has also looked at Chicago before. We thus see a strong regional focus on rustbelt cities, for which he has great affection. He is not a regional geographer whose interest is limited to these places, however. On the contrary, Wilson uses these case studies as exemplars to illustrate a strong theoretical and critical approach in urban geography that contextualizes urban development in global discourses of globalization, neoliberalization, and racialization. He focuses on uneven developments in the city, exemplified by increasing discrepancies between the thriving new downtowns and poverty-ridden marginalized black communities. Wilson contextualizes the latter as citizens living beyond the glittery downtowns and gentrified urban areas, “noncreative” citizens who are neglected in the rationales of urban politicians and developers. One of the major drivers of inequality is racialized urban development, as CitationWilson (2007) laid out most impressively in his book Cities and Race: America's New Black Ghetto. In this important book, Wilson connected the local ghetto to the global trope of urban growth and development and showed how strongly interlinked these two seemingly different narratives are. He delineated the rise of the “glocal ghetto,” relating it to fear and the prison economy, to the salvation stories of heroic mayors, and the effects of incentive-driven federal policies that coalesce with local urban regimes (e.g., faith-based service provision, the No Child Left Behind policy, and workfare). Using these examples, he shows that the growth discourse not only endorses the side effects of uneven urban development (e.g., in the aim to “make creative cities”), but that it contains an inherent social and symbolic denigration of ghetto spaces that is functionalized to enable U.S. cities to be restructured. He thus views urban inequality from a refined racial economy perspective.

By taking this kind of analytical approach to the transformation of U.S. cities under the “onslaught of globalization,” Wilson has emerged as one of the most prolific U.S. urban geographers, working on several editorial boards and committees and assuming leading positions. His latest book adds another angle to his work. He looks at the blues scene in Chicago, thus incorporating a cultural aspect into the discussion. This book marks an important milestone in his academic oeuvre because he uses a profoundly ethnographic approach in his research, spending many evenings in his favorite blues clubs on Chicago's South Side. It was certainly useful that he is a blues fan himself, making music (with the band Painkillers) throughout most of his life, which is perhaps why this book discusses authenticity in such an authentic way. His main thesis is that the remaking of downtown Chicago and the tremendous gentrification wave that is now spilling over into Chicago's South Side are giving new value to the cultural heritage of the African Americans and the black body because they are seen as something that can be capitalized on to “sell” Chicago. As gentrification is changing downtowns throughout the global West into homogeneous urban landscapes, the redevelopment frontier has reached its peak—which in turn decreases its selling value. Developers and entrepreneurs therefore look for “authentic” histories that make the neighborhoods not only expensive, but also “cool” again. Grittiness, a term used by CitationZukin (2011), best describes the nature of more recent neighborhood transformations such as Brooklyn or, in Wilson's case, Chicago. The blues scene on Chicago's South Side is contextualized here in the global fear discourse: “Large crowds of tourists (often from Europe and Australia) arrive in the evenings for a taste of ‘authentic’ raw blackness and expect this music to be served up in bold, bluesy, settings” (p. 26). In the course of gentrification, the traditional blues clubs are affected in two ways: First, the upgrading of the neighborhood brings them new visitors (tourists, businesspeople, etc.) who are able to pay much more for drinks and entrance charges. Second, it trivializes them and makes their music more digestible for a nonblues audience and thus more interchangeable, which in turn minimizes their authenticity. Wilson exploits this ambivalent development to show the complexity of present-day urban redevelopment or—to use his words—of variegated urbanization processes.

Wilson's book thus combines his critical, political views with cultural aspects and urban theory. It not only gives a wonderful insight into Chicago's blues scene; it also familiarizes the reader with the owners of the clubs, the long-term regulars, the musicians, and even the “club outsiders” in long interviews that are nicely woven into the text. The book captures the reader's imagination while providing profound insights into the urban geography of this involuntarily famous neighborhood.

Based on an Author Meets Critics panel convened at the American Association of Geographers (AAG) Annual Meeting in Washington, DC, in April 2019, four experts from specific fields of human geography were asked to critically review the book. Audrey Kobayashi centers her commentary around an empathetic immersion in the culture of blues music and acknowledges Wilson's profound understanding of blues culture. Elvin Wyly reflects on the contribution that the book makes to an already extensive body of literature and debate on gentrification. Does Wilson's approach shed new light on an ongoing debate? Carolina Sternberg worked with David Wilson for several years at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign as his PhD student. Now an associate professor at DePaul University in Chicago, she focuses on the local specificity of the case study and the space-building relationality that it discusses. Finally, Andrew E. G. Jonas, who has conducted extensive research on cities across the world, adds a comparative perspective in his review. What can we learn from this book for other cities, including those outside the United States? The final section of the review forum provides David Wilson with the opportunity to respond to these remarks.

David Wilson's book demonstrates, among many other things, that it's always about more than the music; yet, it's also always about the music. Wilson comes through as both an astute critic of contemporary neoliberal cities and a lover of blues. Taking a cue from the latter point, the book has inspired me to talk in this short piece about the blues. First, to situate the conversation, during the mid-1960s, as a teenager, I was completely hooked on “white” blues—the Rolling Stones, Jeff Beck, Eric Clapton, Jimmy Page, Johnny Winter, John Mayall, Paul Butterfield, and Janis Joplin, along with Jimi Hendrix and Taj Mahal, who were in the vanguard of the new generation of black blues artists. I loved the blues of the Woodstock era but, at age eighteen, did not understand, much less appreciate, where the music or the musicians had come from. I had only a vague notion of the significance of the birth of the blues in the Mississippi Delta, its diffusion to various parts of the United States and the world (especially the United Kingdom), and its appropriation by both white artists and white audiences. I had not heard of Big Mama Thornton, who wrote Janis Joplin's hit “Ball and Chain”; or Otis Blackwell, who wrote many of the songs made popular by early rock-and-roll artists such as Elvis Presley and Jerry Lee Lewis. The blues had been reracialized as white.

Wilson chronicles one of the most significant and enduring migrations of the blues, from the Delta to Chicago. Among the contributions of this book is the captivating manner in which he connects the actual bodies—owners, musicians, patrons—of the blues clubs that became an enduring social, cultural, economic, and political feature of Chicago's South Side to the complex neoliberal machine that threatens, cajoles, controls, and manipulates the capital, property, and bodies that comprise the blues landscape, as spatial tyranny on a large scale.

I turn to Buddy Guy, widely viewed as the last of the “original” South Side blues artists, and a long-standing owner of a Chicago blues club. In a recent interview published in The New Yorker by the editor (CitationRemnick 2019), Buddy Guy expressed his heartbreak at the number of blues legends who have died. He mentioned Otis Rush, Koko Taylor, Etta James, James Cotton, Bobby Bland, and especially B. B. King, at whose funeral he said he suddenly “felt all alone in the world.” He also lamented that his greatest uncertainty is whether blues will outlast him as “anything other than a source of curatorial interest.” He told the story of his last moment with Muddy Waters, who, dying of cancer in 1983, called Buddy to his bedside and said, “Don't let them goddam blues die on me, okay?”

In his autobiography, CitationGuy (2012) recounted his life as the son of a sharecropper in Lettsworth, Louisiana, in the Mississippi Delta—birthplace of the blues among slaves in the cotton fields—to the South Side, where he traveled in 1957 determined to make it in music. There he came under the mentorship of the great Muddy Waters, who had come to Chicago in 1943, and where many claim he invented Chicago Blues.

In 1981, the Rolling Stones were on a huge tour in the United States. They played three nights in Chicago, and on 22 November, they stopped into Buddy Guy's club, the Checkerboard Lounge, where Muddy Waters was the guest of the evening—as he often was. They came together on stage, and were later joined by Buddy and by Lefty Gizz. Buddy wrote that he made no profit that night because the place was so crowded they could not serve drinks, but the Rolling Stones added to their street cred from that famous appearance.

Of course, the huge irony of this situation has not been lost on many. The Stones made millions on that tour alone, and much has been written about the white appropriation of the blues as middle-class music that has thrived in places such as London, England. Nor has the irony been missed that people like myself were first introduced to the blues by the likes of the Rolling Stones. More than one critic has compared this cultural appropriation to modern-day minstrelsy (see CitationHamilton 2016).

Buddy himself had first toured the United Kingdom in 1965, and recounted how young musicians Jeff Beck, Jimmy Page, and Eric Clapton all flocked backstage. Rod Stewart asked if he could carry Buddy's guitar. Eric Clapton later said that he felt guilty about whitening the blues. Buddy Guy's relations with the white blues musicians have been mixed. He had cause to be bitter. In the 1970s he was booed off the stage at a German blues festival because he didn't look right. Blues historian Elijah Wald said in an interview with David Remnick, “I feel like Buddy Guy is somebody who, due to American racism, never quite reached his potential. He could have been a major figure, but he was pigeon holed as a museum piece, even in 1965…. Nobody from Warner Bros was coming to Buddy and saying ‘Here's a million dollars, what can you do?’” (CitationRemnick 2019). Buddy himself said in an interview for Living Blues magazine in the 1970s, “All you have to do is be white and just play a guitar—you don't have to have the soul—you gets farther than the black man” (CitationRemnick 2019).

In 2019 Buddy Guy released an album that won the Grammy Award for best traditional blues. The entire album is devoted to his commitment to keeping the blues alive. The first song is a kind of prayer to grant him “Just a few more years” so he can get the job done. The album also features guest appearances by Keith Richards, Jeff Beck, and Mick Jagger. These songs are a tribute to and a blessing on the UK blues players, a musical statement that the blues are alive and well. What are we to make of this blessing, though, with its many ironies, ethical twists and turns, and neoliberal commercial ties?

In another set of ironies, Buddy Guy's daughter, Shawna, a hip-hop singer who also works at Buddy's current bar—located somewhat away from the South Side and aptly named Legends—explained the tension with her father over the fact that hip-hop has now transcended the blues as African-American music, born not of the cotton fields, but of the urban ghetto (and of course hip-hop is also a paradox that ranges from political street protest to the heights of commercialism): “We worry about him, but he's happy to keep his promise to Muddy Waters and B. B. King. That's why he won't stop touring” (CitationRemnick 2019).

Wilson's book certainly does not share the same implied optimism that the blues have transcended race, and thereby racialization and racism. Guy's optimism still butts against the cynicism of the neoliberal fear machine and the tyranny of capital. Therefore, Wilson prompts me to ask questions to which only irony and contradiction can be responses:

| 1. | If the blues have in any part transcended race as a musical genre as it moves from the Delta to Chicago to London and beyond, perhaps thoroughly appropriated by the middle class everywhere, whitened and commercialized, does there remain a place of allyship where, even if it is not only about the music, it is still about the music? | ||||

| 2. | What is the significance of the hip-hop transcendence? As Guy himself said, “Blues is the root; the rest is the fruit.” Yet he laments that hip-hop seems to be falling farther and farther from the tree. Will the South Side Chicago blues survive as hip-hop? | ||||

“It's true blue here, the best alternative Chicago can offer … it's the real thing, pure, straight-ahead blues in an authentic South-Side setting … you can't get better than this” (p. 143). So says a middle-aged Australian “blues wannabe” speaking to David Wilson in Beebe's, a club on the South Side of CitationDrake and Cayton's (1945) Black Metropolis from last century, now part of this century's complex global frontier of race, capital, and culture. In Chicago's Redevelopment Machine & Blues Clubs, Wilson mobilizes urban political economy and critical race theory to analyze the intricate zones between stigmatized blackness and poverty and a new redevelopment frontier positioning the South Side as a “race authentic” resource for the city's globalizing aspirations. African-American culture, authentic blues music, and “exotic” traditions are showcased as objects of fascination, embedded in a unique but globally recognized sense of place. This new redevelopment frontier is the site for the sharpest contradictions between local labor-market pain and mobile, transnationally mediated consumer fantasies. This is also where we find the most dramatic innovations in growth machine rhetoric and strategy.

Among the many valuable contributions of this beautiful book is a genuinely new perspective on gentrification. For decades now, the literature has been distracted by unproductive dichotomies—supply–demand, economics–culture—interwoven with a flawed geographical conceptualization portraying gentrification solely as a localized, neighborhood-scale process. Even the best research on the interplay between global and local processes eventually privileges narratives of local, street-level imprints that etch specific boundaries, borders, and limits—as something we can see in one neighborhood and not another. The sole exception—CitationSmith's (1982) diagnosis of the leading edges of uneven capitalist development in a diverse yet decisively global strategy of neoliberal urbanization—has been challenged as a neocolonial imposition of Global North theory on the distinctive cultures of urbanism in the Global South and East. Unfortunately, the obsession with the local scale and the well-intentioned Southern and Eastern critique have obscured a deeper essence: Gentrification is a multidimensional, pervasive, and widely diffused symptom of intensified human competition in all domains of life, in a global geopolitics where inherited colonial hegemonies confront diversifying postcolonial ascendance. This is clear from the very beginning of scholarly discourse on gentrification.

Glass coined the term in 1964 in an analysis of the center of a global empire shaped by increasing competition for jobs and homes as the colonial subjects of the planetary Commonwealth arrived to claim their citizenship rights—only to encounter vicious discrimination and the industrialized racism of the colonial, metropolitan mind. Glass used the word gentrification to lampoon a particularly ironic expression of this locational competition in a few neighborhoods in London, but it is clear from everything she wrote in these years that her real target was the “liberation” of market forces amidst the intergenerational inheritances of colonial power, inequality, and thought. Glass clearly saw the dangers of neoliberal thought in those years when Friedrich Hayek was building the ideological infrastructure of world-consuming militarized market theologies of Ronald Reagan, Deng Xiaoping, Augusto Pinochet, and Margaret Thatcher.

Hayek revived nineteenth-century associationist psychology and hijacked a distorted strain of Darwinism to build a philosophy of human ignorance in the face of a transcendent, omniscient phenomenon—the free market as collective species intelligence, as the unsurpassed information processing device produced by millions of years of evolutionary competition; hence Glass's rage at the neo-Malthusian principles embedded in English urban planning in the 1930s, consolidated in Thatcher's no-society, no-alternative implementation of Hayek's doctrines of optimized selfishness in the 1980s. The U.S. counterpart to Hayek's European social Darwinism was the genocidal Turner thesis and the biopolitical economy of the Chicago School of Sociology—portraying a human ecology of incessant competition and a cognitive Darwinism epistemology that has morphed into neuroscience-infused behavioral economics and varied rationalizations of cybernetic, “crowd-based capitalism.”

This brief history of the urbanization of neoliberal consciousness helps situate Wilson's brilliant analysis of a Chicago machine that has literally evolved in a half-century of industrial creative destruction, as the city has transitioned from a dominant production center of northern industrial racial capitalism to a more peripheral node in the competitive transnational urban systems of a polycentric mode of multicultural cognitive-cultural capitalist prosumption. Wilson's eloquent analysis of the changing racial, historical, and cultural rhetoric of Chicago's redevelopment machine is one borehole sample for the stratigraphy of generations of colonial-capitalist violence underneath the edgy retail and entertainment gentrification districts of a planetary system of diverse, adaptive, and expensive forms of intensifying human competition in and for urban life.

Wilson documents how the machine is fueled by distorted yet powerful forms of remembrance, as agile, flexible new constructions of long-familiar racialized fear alternate with discourses of authenticity. The South Side is the landscape of racialized danger, the tangle of underclass pathologies, and the globally spectacular public housing failures that discredited the Western welfare state. Yet it is also the morphology of cultural landscape of the Great Migration. Half of the net flow of arrivals to Chicago in the 1940s came from Mississippi—including, among the multitudes of the truly creative classes, Muddy Waters, born in Rolling Fork, raised in Clarksdale, played in Memphis, then arrived in 1943 to what had become the second-largest black city in the world (surpassed only by Harlem). Today's machine operatives position South Side blues clubs as the instruments of a “therapeutic” renaissance, salvaging an authentic black cultural infrastructure in a “symphony of diversity” as historic preservation is engineered for a community that is said to have “lost touch with its own history.” Wilson analyzes the contradictory spatial imaginary of “cherished Black cultural histories” inside clubs that are surrounded by a South Side repeatedly stigmatized as a terrain of cultural chaos. Installing historic “Blues Trail” markers tracing cultural-creative histories from Mississippi to Chicago, machine entrepreneurs deepen neighborhood segregation while subtly adjusting its boundaries to facilitate speculative investments at the edge. This is the new frontier of flexible accumulation, just-in-time essentialism—of semiotically commodified human diversity marketed in complex, transnational fields of cinematic representation and manufactured quasi-intellectual nostalgia of the sort that made The Wire so wildly popular among British postgraduates.

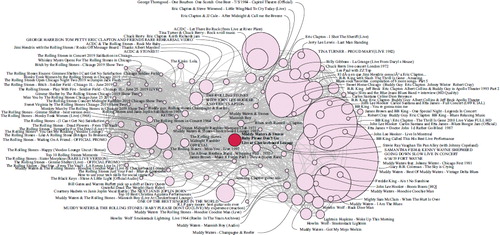

Wilson develops a remarkable form of ethnographic political economy to help us understand this strange new world of encounters, fears, and desires in a time–space constellation of blues, bodies, and buildings. In one configuration of scale, blues wannabes and voyeurs arrive to South Side clubs through distinct yet coconstitutive processes. Those at a distance with economic capital are delivered by globe-spanning airline networks into O'Hare in their pursuit of authentic cultural capital. That's how our middle-aged Australian who found straight-ahead blues in an authentic South Side setting got to Beebe's; one wonders if he knows that, twenty years ago, Sir Peter Hall observed that white America paid attention to Muddy Waters only after the Rolling Stones stole one of his songs for their name (). For those who come from nearby—those dispossessed from economic capital but whose collective cultural capital fuels the blues machine—the clubs provide a short escape and recovery from the daily traumas of a polarized labor market.

At another configuration of scale, we see new relations between the materialist circulation of real estate capital in the urban built environment and the idealist planetary circuits of memetic, cognitive capital. Here is the true brilliance of Wilson's contribution: He's synthesized Harvey's political economy of neoliberal urbanism with McFarlane's assemblage urbanism, Roy's postcolonial analysis of ethnoracial property dispossessions and resistant emplacement, and the forensic examination of imagineered media capital of the Los Angeles School theorists. In a recent essay, CitationRoy (2016) asked, “Who's Afraid of Postcolonial Theory?” Certainly not the operatives of Chicago's adaptive, innovative machine: Wilson's analysis reveals the sophisticated racial fabrications of diversity, authenticity, and danger; the multiscalar, fast-policy manufacturing of globetrotting elites; and the deployment of emergency redevelopment temporality crafted for the local public's emotional terrain.

Wilson's gripping, immersive analysis of blues wannabes engaging in fluid, flexible identity projects of self-definition—as some of them travel around the world to erase their whiteness or their cosmopolitan, diverse ethnicities in pursuit of the binary of blackness as authenticity—maps the neural-planetary spatial fix circuitry of cognitive capitalism, as intersectional neoliberal market innovation coevolves with ascendant post- and neocolonial rivals in an urban world of incessantly intensifying human competition. In the “cybercultural” era diagnosed by the Chinese/American/Black Power philosopher Boggs (CitationBoggs and Boggs 1966) at exactly the same time Glass was studying gentrification, the market-cap trillions of the culture industries reflect and reinforce the rising global capitalization of real estate (now more than $60 trillion). Wilson takes us through the doors of the South Side clubs, and opens the portals revealing the leading edges of multidimensional evolution of communications, culture, and capital in a dynamic planetary urban system.

David Wilson's wonderful new book builds up from, and extends much of his earlier work, thinking urban redevelopment processes in U.S. rustbelt cities through a racial economy lens and a relational framework, while also proposing new forms of examining articulations of resistance and opposition to urban redevelopment machines. In particular, this book makes a significant contribution to understanding the informal and performative forms of political mobilization that seem to help build new moralities, new identities, and a sense of self-determination.

There is much to be said and celebrated about Wilson's new work, but let me first discuss two salient points that I consider to be major contributions to the field of urban studies and to social theory more broadly, and later offer some thoughts about what makes Chicago different or specific in the context of this book. First and most immediately, Wilson reminds us about the dynamic nature of Chicago's redevelopment machine. For example, in the process of normalizing neoliberal ideology and globalization imperatives, Chicago's urban redevelopment machine becomes something distant from its mainstream characterization as a monolithic and relentless formation. Throughout the text, Wilson illustrates the machine's significant ambivalence despite its obtrusive perception as decisive and powerful force that encompasses all. Through a constant negotiation and human mediation, Wilson reminds us, this machine has to work through the following elements: first, the multi-interpretable nature of material and symbolic spaces; second, the multiscalar and simultaneous interconnection of spaces. Ultimately, these spaces would be assembled, communicated via symbols, and refunctionalized to contribute to the go-global Chicago project. Third, there are stark and sustained contradictions of two prevalent urban built environments (that the machine cannot make sense of): On the one hand, swaths of gentrified blocks expose upscale restaurants, retail stores, and luxurious condominium buildings; together they communicate a vibrant restructuring process that only benefits privileged white identities and the city. On the other hand, these urban settings communicate a clear and sustained racial project that has crystalized layers and layers of urban intervention, systemic oppression, and overt segregation. Finally, there is the series of articulations of resistance in the South Side of Chicago, in particular, in the blues clubs' arena, demonstrated by patrons, musicians, and clients.

My second point refers to the importance of space-building relationality as a key component to understanding how neoliberal governance operates on the ground. In CitationWilson's (2007) earlier book Cities and Race: America's New Black Ghetto, he chronicled the relational constitution of a morally failing inner-city/black ghetto and the glittery vibrant downtown. Now, post-2000, the South Side redevelopment needs to be understood as a tangible expression of both localized and multiscalar drives in efforts to contribute to “go-global” Chicago. In Wilson's words, “In a profound relationality, then, designs to remake the social fabric of a blues clubs in Bronzeville bear the logic of machine actors seeking to re-structure the entirety of Chicago. Producing a strategic convergence of edginess, exoticism, and stable black ways on one micro-spot serves multiple goals” (p. 64). It follows that, through this space-building relational arch, blues clubs can be “now discussed and recast by machine operatives as historic, culturally salvageable, mechanisms to engineer sane and civic black persons, and ripe for inclusion in the drive to further Chicago's ‘go-global’ remaking efforts” (p. 162).

Now, what does the book tell us about Chicago? Is Chicago different or specific? Throughout the book, Wilson constantly emphasizes the place-based and contingent nature of Chicago's redevelopment machine. First, he understands that Chicago's machine attempts to come to terms with a new and locally specific iteration of neoliberal ideology and globalization. In other words, neoliberal redevelopment machines are constructed within new economic and political imperatives but through grounded practices, understandings, and histories. By simultaneously documenting the drive to advance Chicago's “go-global” remaking efforts while, now, sanitizing the presence of the racialized poor and commodifying the South Side (in the author's words, through “race-class phobia speak” and “global destruction speak”), Wilson genuinely illustrates the richness and locally specific nature of Chicago's redevelopment machine. To summarize, the tension between the drive to commodify the South Side including the blues clubs, and the necessary control of black bodies to prevent them from entering housing submarkets, reveal the deep historical and geographical components of Chicago's redevelopment machine.

Second, Wilson offers a discourse analysis of the global fear speak that is also inherently specific to Chicago. Although he reasons that “globalization” and the “global fear speak” is a stretched discourse, one that creates a strong network of characters and spaces intimately linked to “peoples” commonsense understandings of the world, he carefully considers the contingent historical-geographical processes that construct it. In his words, “the present is distinctive, current fears that these actors assemble offer an unprecedented ‘emergency redevelopment time’ which uses new fears with new intensities” (p. 164).

Third, Wilson alerts us that the global fear speak is fluid and constantly changing, always multitextured. More important, to him, this discursive formation is effective and solvent to creating consent among the city's population, primarily because it is elaborately staged by the locally specific actors who adroitly work via the creation of fear to “terror-redevelop” in a historically deprived South Side.

Fourth, the four dominant “spaces of spectacles,” namely, the multicultural aesthetic space, global connection space, creative-class living space, and for-display poverty-reduction space, remind us that they are all produced, imagined, and constituted under a locally situated and deeply rooted conception of race and racialization that do tremendous political work for the machine. These conceptions help build normalcy, confer legitimacy, and justify redevelopment agendas. In addition, these spectacle spaces, closely following CitationMassey (1992), simultaneously frame, organize, and communicate unique spaces that symbolize and celebrate whiteness or white identity, and also remind Chicagoans of “whom these new spaces are to be for” (p. 42). These spaces are as important to constituting identities as is any resource used in discourse.

Finally, Chapter 5's discussion of “leisure as politics” (grounded in Roy's “politics of emplacement”) also strongly speaks to the rich specifics and place-rooted basis of redevelopment governance in Chicago. For example, the discussion of the “politics of leisure” or the leisure as politics is attuned to the present history of racial banishment that Chicago experiences, without for this giving less importance to the aspirations of resolution and possession blues clubs' patrons and clients might have constructed over the years. Few have been as skilled at documenting and ultimately deconstructing such a complex, rich articulation of resistance and opposition. Through fifteen months of ethnographic analysis, Wilson incredibly dissects a type of subterranean and performative form of resistance that ultimately helps resolve the tension between clients', patrons', and musicians' aspirations to remain as such, and the advancement of blues clubs' commodification. In his words, the “intimate practice of constructing domesticity … is less about dominating a venue than producing and commanding space … as an enduring social product” (p. 169).

I would also like to take this opportunity to offer some questions to the author and link them to a broader question that interpellates us as intellectuals. To what extent is the commodification of the blues clubs engaged in a much larger racial project than an advancement of the redevelopment frontier? I raise this question because the work of Chicago's redevelopment machine prompts me to think of a broader process of racial banishment and a successive demonstration of white supremacy. Recently, I read an article in the Chicago Reader about the possibility of Chicago facing, as the author puts it, a “black exodus,” or what others have named “the reverse of the Great Migration” due to Chicago's legacy of segregation and its present pervasive segregation levels.

Along the same lines, following CitationOmi and Winant's (1994) classic work on racial formation in the United States, Chicago could be interpreted as a succession of racial projects, where race continues to float through common thought and institutional practices as frequently unspoken, but it constitutes a powerful distributor of resources and citizenship. In this sense, I wish the book offered more discussion of the white discursive formation that seems to permeate every redevelopment project. In particular, I would be interested in knowing more about the process through which the “dominant spaces of spectacles,” namely the multicultural aesthetic space, global connection space, creative-class living space, and for-display poverty-reduction space, become normalized as white spaces.

Finally, I am also bringing this comment as a way of reflecting on the role we occupy as intellectuals. I am concerned that urban scholars, including myself, are not doing enough to examine redevelopment machines as operating within a wider spectrum of white supremacy as the everyday state of affairs in the societies in which redevelopment operates. I feel that if we don't take these things into consideration, we will be reproducing our own white subject position in our analyses, and in so doing, fail to recognize (let alone contest) the actually existing forms of white supremacy that have been built on a succession of urban planning racist operations.

In this important new monograph, David Wilson turns his critical gaze from studies of classic growth-machine politics in U.S. Midwestern cities, such as Indianapolis, to the dramatic sociospatial transformations under way in “global city” Chicago. A consistent focus of Wilson's research over the years is the critical analysis of discourses of race, redevelopment, and urban growth, exposing inter alia the global trope in growth machine-orchestrated gentrification and redevelopment. This trope is a reference to the discursive use of the threat of the global—notably, capital flight—to discipline the local—in this case, inner-city African-American communities. Racialized discourses, he has argued, prepare the ground for radical transformations of urban space by neoliberal growth elites. In Chicago's Redevelopment Machine & Blues Clubs, Wilson documents how the machine has harnessed the global trope in conjunction with a sanitized language of cultural regeneration to transform Chicago districts, especially the South Side.

Wilson foregrounds bodies (human subjects) as contingent neoliberal subjects, who are ever more vulnerable to the vicissitudes of capitalist urban development. He persuasively argues that redevelopment is not just about material spaces and institutions, but also embodies words, symbols, and meanings of how people should live, work, and behave in these transformed urban spaces. Wilson skillfully teases out how the discursive frames the material and how, in turn, the material transformation of Chicago districts is embodied, enacted, and articulated through bodily discourses.

The remainder of this commentary highlights two significant contributions of the book. First, I consider how Wilson's analysis deepens and extends existing scholarly knowledge of the changing forms and processes of Chicago urban politics in a “global city” era. Second, I reflect on what the study reveals about the specificities of the U.S. politics of urban space in a comparative perspective.

From “TIF Town” to “B-LT”: The Changing Forms and Processes of Chicago Urban Politics

Since at least the 1990s, the City of Chicago has made extensive use of tax-increment financing (TIF) to raise capital for infrastructure and redevelop industrial and residential districts ripe for gentrification, often at the expense of other districts and services such as local education. On the North Side, investment in street-level infrastructure has transformed aging manufacturing districts into new work-live spaces attractive to gentrifiers. For example, along the Clybourn Corridor, residents and visitors could, until quite recently, enjoy clean and shiny TIF-funded sidewalks and peer into craft steel production facilities where workers cast steel rods and tools. Once hidden behind grim factory walls and barbed wire, production sites and attendant bodies in today's Chicago have become an urban spectacle for consumption in upscaled former working-class industrial districts.

In his book, Wilson links the widespread use of redevelopment to the administration of Mayor Richard M. Daley in the early 2000s. Nonetheless, it is possible to delve deeper into Chicago's landscape of special districts and zoning ordinances to unearth how, over a much longer time period, such policy instruments have carved up city neighborhoods into investment-friendly havens for business and property developers. Indeed, some districts and ordinances challenged the market-driven redevelopment regime. In the 1980s, planners and activists on the North Side rallied around Mayor Harold Washington's plans to hold back gentrification through protected manufacturing districts (PMDs). Their overriding aim was to use PMDs to prevent the exploitation of putative rent gaps by predatory developers and global equity investors eager to rezone manufacturing districts to residential. Although partially successful on the North Side, PMDs never crossed the Loop to the South Side, where no amount of institutional lubrication was sufficient for capital to “see-saw” back into the district. Nonetheless, once the North Side was colonized by gentrifiers, the South Side was soon exposed to the vicissitudes of Chicago's neoliberal racial redevelopment regime in the early 2000s.

Acronymically, one might characterize the recent transformation of Chicago urban politics in terms of a transition from “TIF town” to “blues-led transformation (B-LT).” Wilson's maps and data (e.g., Figure 4.2, p. 97) hint at a spatial correlation between the boundaries of South Side TIF districts and the location of blues clubs. The latter occupy, in effect, a new zone in transition between actual (pre-TIF) and potential (post-TIF) ground rent, and between abandoned industrial and commercial property and revitalized commercial and residential uses. Moreover, if Chicago's TIF-led redevelopment regime is an example of “third-wave” urban competition, Wilson nonetheless intimates that Chicago has entered a fourth wave. Redevelopment machine actors “place themselves on exhibition as proud technicians of space” (p. 56) and engage in a purportedly humane redevelopment, using mechanisms such as rezoning to imagine and create new ways of living for Chicago's poor and disadvantaged. The material ingredients of this redevelopment regime are, to be sure, TIF districts and similar rezoned urban spaces, but it also includes the subtle manipulation of discourses around the motif of healthy bodies, which “centers upon the healing and recovery of people and place as prime motivations for the machine use of historic preservation on the South Side” (p. 77).

Race, Chicago Blues Clubs, and the U.S. Politics of Urban Space

Chicago politics are changing. So, too, are the spaces of U.S. urban politics at large. The struggles of the 1950s and 1960s were, for the most part, an urban politics of collective consumption and segregation fought around race, residence, and place. In comparison, those of the 1970s and 1980s were the politics of production, deindustrialization, and urban shrinkage, which in turn prepared the ground for the global-city politics of the 1990s and 2000s. Across the urban United States today, emerging social and political movements strive to link neighborhood, community, religion, class, and race to struggles around a living wage, wage theft, and austerity. In his rendition of this fraught urban political landscape, Wilson chooses not to treat race and class as a duality but rather as a unity (race-class) in constant tension.

There is another dimension of the U.S. politics of space suggested in Wilson's book: that of an urban politics of circulation. In marshaling the global trope, the Chicago redevelopment machine draws its inspiration from redevelopment practices and policies circulating through other cities. Wilson frames this spatial politics of circulation in terms of the threat of the global as “other,” on the one hand, and the desperate attempt to find a spatial fix, on the other, in the form of the “spaces of hope” offered by poverty-reduction redevelopment. Besides the local and the global, what other spaces and imaginaries might be enrolled in this politics?

It has been noted by CitationRodgers, Barnett, and Cochrane (2014) that both territorial and network relations are intertwined in the urban politics of “here” and “there.” For example, global-city elites often infuse local redevelopment with potent references to national ideals and imaginaries. So when we consume Chicago blues are we also consuming a U.S. idea or ideal? Consider this example. My favorite bar in my university city of Hull in the United Kingdom, sells craft beer manufactured in Chicago's Goose Island. The bar gets its name from the late Philip Larkin (1922–1985), former university librarian and nationally recognized poet. Larkin was a lover of jazz and the blues; yet his problematic views on race echoed the troubled times of the 1950s and 1960s. His extensive collection of vinyl, now housed in a local archive, includes the works of Sidney Bechet, who moved from New Orleans to Chicago in 1917. Larkin himself never went to Chicago, but Chicago came to him through the blues. Now, an unlikely conjuncture of Chicago beer, blues, and redevelopment comes together in a local bar in a gentrifying student district in the working-class port city of Hull. If, like Larkin, we cannot live without the Chicago blues, we can always bring it to us and consume our city around our own particular U.S. imaginary. When you read Chicago's Redevelopment Machine & Blues Clubs, I invite you to reflect on the power of this and other contemporary urban imaginaries.

Coda

Wilson's fascinating journey into the Chicago blues scene convincingly demonstrates that the contemporary politics of urban redevelopment often defy a simplistic neoliberal urbanism oe global-city reading. Instead, Chicago's urban landscape contains a rich palimpsest of urban political movements and countermovements, which today include opposition to TIF-led redevelopment. Putative struggles occurring around B-LT feed into, and occasionally conjoin with, city-wide social justice and living-wage campaigns. As such, Chicago's transformation remains a deeply contested political project, which demands the kind of carefully crafted analysis powerfully exemplified by Wilson's highly readable monograph.

I am indebted to my five interlocutors—Ulrike Gerhard, Andrew E. G. Jonas, Audrey Kobayashi, Carolina Sternberg, and Elvin Wyly—for their substantive and constructive ideas. I continue to be inspired by their insights as I engage each of them in this and other forums. Each, in this panel about my book, provides important insights on an undertaking that strives for not always easily discernable synthesis and interconnection. There is much richness and diversity in points taken up. Narrowing the focus, my brief response addresses a central theme that they collectively discuss, how to best understand current redevelopment governances in the Global West. In this context, three points repeatedly emerge: a need to be sensitive to whiteness, the need to consider a vast historical horizon, and the need to unearth the contingencies and complexities of urban imaginaries. In this response, I riff on the importance of these points and how we need to further probe them.

Whiteness

Whiteness, the commentators identify, needs more substantive focus as a powerful discursive formation to understand current city redevelopment's assault on these blues spaces and blocks. Whiteness, they recognize, dimly threads through this formation's planning, struggles for legitimacy, and practices that meld racist rationales with accepted institutional actions. At its core, especially to Carolina Sternberg, a powerfully banal privileging enables one race-class group to seize and manage space, populations, and institutions. Whiteness, Sternberg and others suggest, is an unstable and changing complex of meanings—constantly being transformed by political conflict—that embeds in the institutional policies and practices of redevelopment. It, constituted out of a melange of myths and bounded understandings, is a sutured-together and polished political ethos that delineates and differentially situates people as genetic beings, cultural creatures, moral subjects, sociospatial actors, behavioral persons, and kinds of citizens. Through this mobilizing, a raced-classed redevelopment creates and works through a distinctive script of city contributors and salvationists, city victims, city villains, and countercivic subjects.

Yet in this context, I assert, whiteness in current redevelopment practices needs to be seen as distinctive in a particular way: It is a fundamentally fragile and delicate enterprise. This notion runs contrary to much analysis of such governances that are identified as outgrowths of stark, austere, neoliberal sensibilities in current times. These governances, I suggest, currently engage populations and spaces—discordant, resource-starved, poor racialized populations and communities—that are unlike any other that they have navigated in their decades-long drive to restructure. It is a new day, a new time, a new milieu of action that we must recognize.

In these new accosted milieus, the anger and angst are thick and robust: Many know and still feel the history of federally subsidized, ravaging housing abandonment, afflicting welfare-to-work interventions, rough-and-tumble policing programs, negligent city tax policies, and afflicting No Child Left Behind initiatives. In this context, governances are tasked to simultaneously humanize and demonize these areas; this is no small order. The neoliberalized redevelopment is dicey: Capital's seizure and takeover of land and buildings requires a demonizing of residents, but also a humanizing of them to cultivate perceptions of safety and authentic black culture for white middle-class resettlement. Much is messy and muddled, even as whiteness is the ticket chosen to move this bizarre and macabre balancing act forward. Whiteness, CitationRoediger (1999) noted, is one of the modern era's powerful, enduring structural forces that often easily escapes detection and can potentially accomplish such goals. At this moment, whiteness becomes a desperate—and tenuous—resource that redevelopment governances rely on in this highly vulnerable quest to restructure.

Historical Horizon

A sensitivity to a vast historical horizon, the commentators note, would deepen and nuance studies of this current city redevelopment. I agree, and believe they suggest that time does not passively lie out there for human occupation (rejecting Plato) or temporalize itself (rejecting Heidegger). Instead, redevelopment governances strategically temporalize time. The commentator call (particularly by Elvin Wyly and Andrew E. G. Jonas), I believe, is to recognize the specificities of the moment and doing to the construct time what urban geographers now widely do to the concept space: posit it as a constituting ingredient of social relations, urban spaces, and the world. The specificities of the moment are that redevelopment governances battle to transform a new terrain that offers immense unpredictability. This bloc today scavenges for any resources—rhetorical, financial, or political—that could assist them. Perhaps not surprisingly, they rediscover and reanimate the calculus of time, widely understood as a passive dimension in everyday life but always being converted to a knowledge constituting input.

Now, I suggest, this conversion has gained vigor and pronounced race-class political content. A battle is unfolding, over what these blues spaces will become, and the weaponizing of time becomes similar to manufacturing discursive space, securing financial resources, and drawing on political power to achieve desired redevelopment. It follows that a deeper recognition must be made: Time in this current redevelopment mode needs to be seen as a capitalist-modernist object of knowledge and usage seamlessly put in the service of politicized knowledge creation. It is invented and deployed to move modernist redevelopment projects along in quintessentially modernist clothing (sold as an autonomous, inert, deadened, and apart-from-the social and political sphere). Hived out of a contradictory world, the notion of time helps maintain and drive this world.

More depth about my point is in order. Moving beyond the recognition of relationalness and dialectics, time in these studies needs to be seen as an idea—temporality—whose putting into play fabricates the newest redevelopment ideals and practices. Its usage is immense and varied. Thus, time in this newest phase of redevelopment, an elaborate temporality, discursively locates residentially displaced populations in histories of degenerate cultures, discerning creatives in pasts of serene, middle-class communities, planners in historic dens of technocratic learning, and privatization as a logical unfolding in time evolution. Through this powerful constructive resource, inventions of people and spaces are provided meaning and become “temporalized” into submission. Time ultimately animates the discursive content of elements in cities—people, places, processes—that relentlessly constitutes scripts of best redevelopment practices. A deployed temporality, deeply implicated in seeking to manage knowledge and policy production, differentiates objects in the world and provides a concept for understanding that differentiation.

Urban Imaginaries

A sensitivity to complex and variegated urban imaginaries, the commentators identify, is essential if we are to nuance understandings of this current city redevelopment. Through imaginaries, they note, redevelopment actors (from its leading advocates to its central resisters) calibrate ways to see the present, make this a reality, and plan the city's future. Opposition in any form from embraced and peddled visions needs to be killed off. In this context, Andrew E. G. Jonas, Audrey Kobayashi, and Elvin Wyly infer, urbanists now work through the insight that controlling and managing imaginaries is the new fertile terrain for city redevelopment politics. This managing can do immense political work for redevelopment governances in ways that formal rule making and regulating cannot. Discourses, the fundamental facilitating instrument, are constituted as attempts to dominate fields of discursivity even as social orders are tenuous, precarious, set in shifting terrains of meaning, and open to multiple negotiations. The tyrannizing power of discursive formations, it follows, can never be complete and total.

Yet I suggest that we need to see this imaginary making in a way that runs contrary to much of the literature: as an always unfinished, turbulent human accomplishment. Building on my first point, this idea speaks to the immense and difficult work of serving up realities authored by current redevelopment governances. This serving up, simply put, is never simple and pat. Engaging neighborhoods and populations already decimated by assaulting bulldozers, high-rise constructions, land clearance schemes, and blatant neglect requires acutely improvisational creations in the discursive. Plunging headlong into the arena of adroit reality making, governances bear only superficial similarities to recent interpretations of them as stumbling, creativity-bereft beasts. Thus, they borrow from and depart from the recent past to assemble flamboyant, dialogic narratives of ever-changing characters, mutable processes, and fluctuating renditions of the city. In this context, these governances today construct multiple conceptions of blackness, Latinoness, and immigrants (often contradicting other conceptions) to fit the need at the moment, shuffling back and forth in their invoking of meanings to make restructuring projects work.

This point is important: I suggest that once this fragility in reality making is known, an amazing outcome can follow: Cracks and crevices in the operations of governances can be more clearly seen. Seemingly sturdy, zombie-like blocs become exposed for what they are: struggling, toiling entities that flail away for what they so desperately desire, public legitimacy and public confidence. The self-anointed and celebrated “end of history” city salvationist suddenly becomes exposed for what it is: a tumultuously organized, ever blinkering assemblage of institutions. Power blocs, seemingly sturdy and impenetrable neoliberal tigers, are brought back to earth and made objects for fruitful confrontation. Struggle and resistance now have targets to bring down redevelopment regimes, zeroing in on what CitationBakhtin (1981, 57) would call “highly heterogeneous parodic-travestying forms.”

Conclusion

I reiterate my book's position that Chicago's and possibly many Western redevelopment machines today are amazingly sophisticated in strategies, imaginings, and actions. My interlocutors in this book review forum agree with me, suggesting the need to nuance key principles that will enable the unearthing of deeper understandings. Such neoliberalized blocs might be tired and aging and prone to rebirth failed practices under numbingly familiar rhetoric, but often there is more here than meets the eye. As these actors navigate ever-changing political and economic currents in contentious, deeply punished, and polarized new redevelopment zones, we need to look more subtly and deeply at how they operate. Improvisational assemblages, mixing and matching, among other things, new temporalities, imaginings of villains and victims, plays to fear and hope, invokings of whiteness, and deployments of nostalgia and race-class ferocity, are the day's order. Through it all, provocation, control, and management are everywhere, as redevelopment actors elevate human insecurity and promises of redress to central organizing principles.

At the same time, though, here is a point we should not forget: This sophistication is frequently matched by the deft politics of resistance (as the book shows). Here people play and act out unanticipated kinds of politics in informal and formal settings to subvert meaning systems, value orientations, and established ways to see. Creating space outside neoliberal protocols and managerial surveillance, the signs are unmistakable: The future of redevelopment in all of these cities remains truly open and up for grabs.

References

- Bakhtin, M. 1981. The dialogic imagination. Austin, TX: University of Texas.

- Boggs, G., and J. Boggs. 1966. The city is the Black man's land. Monthly Review, April: 35–46.

- Drake, S., and H. Cayton. 1945. Black metropolis: A study of Negro life in a northern city. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

- Guy, B. 2012. When I left home: My story. Boston, MA: De Capo Press.

- Hamilton, J. 2016. Just around midnight: Rock and roll and the racial imagination. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Massey, D. 1992. Politics and spacetime. New Left Review 196: 65–84.

- Omi, M., and H. Winant. 1994. Racial formation in the United States: From the 1960s to the 1990s. 2nd ed. London and New York, NY: Routledge.

- Remnick, D. 2019. Buddy Guy is keeping the blues alive. The New Yorker. March. Accessed March 4, 2020. https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2019/03/11/buddy-guy-is-keeping-the-blues-alive

- Rodgers, S., C. Barnett, and A. Cochrane. 2014. Where is urban politics? International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 38: 1551–60.

- Roediger, D.R. 1999. The wages of whiteness: Race and the making of the American working class. New York, NY: Verso.

- Roy, A. 2016. Who's afraid of postcolonial theory? International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 40 (1): 200–09.

- Smith, N. 1982. Gentrification and uneven development. Economic Geography 58 (2): 139–55.

- Wilson, D. 2007. Cities and race: America's new black ghetto. London and New York, NY: Routledge.

- Zukin, S. 2011. Naked city: Death and life of authentic urban places. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.