It’s good news that Mike Davis has written a new book about Los Angeles! He is joined by Jon Wiener; both have been scholar-activists since the early days of Students for a Democratic Society (SDS). The book is a history of popular political movements and upheavals in the City of Los Angeles during the 1960s. It is 800 pages of gritty, street-level movement history, providing an invaluable and unforgettable record of an exciting, violent, triumphant, and disappointing decade. Do not be put off by its length. I read this book straight through (although not in a single sitting).

Mike Davis is well known among urbanists for his indispensable political history of Los Angeles, entitled City of Quartz (Davis Citation1990), and his follow-up, Ecology of Fear (Davis Citation1998). During the mid-1960s, he was regional organizer for SDS, a draft-card burner, and a member of the Southern California Communist Party, among other things. Later he was an academic, a prolific writer, and MacArthur “genius” fellow. Jon Wiener is best known for his twenty-five-year campaign to win the release of the FBI files on John Lennon. He organized the Princeton SDS in opposition to the war in Vietnam, and arrived in Los Angeles in 1969. There he interviewed Mike Davis, who he remembers as “intense, eloquent, and a little intimidating” (p. 644). Wiener is a longtime contributing editor to The Nation magazine, and host of its weekly podcast.

Set the Night on Fire consists of thirty-six chapters, plus a short introduction and epilogue. It is not an edited volume, nor a compilation of previously published works. With a couple of exceptions, Davis and Wiener have written fresh essays, guiding the reader through a tumultuous decade of grassroots activism in one of the most important cities in the United States. The tone of their inquiry is established in the introductory chapter that is a small masterpiece of perspective and concision. Month by month, the authors track the emergence of dramatic new agendas for social change emanating from such sources as black students in the South, gay protests on the Sunset Strip, and progressive campus organizations at Berkeley, Michigan, and many state colleges.

At its heart, the book constructs a cartography of 1960s activism in L.A. The thirty-five chapters are divided, roughly chronologically, into eight overlapping topical sections that together render a historical and geographical mapping of a time and a place. The narratives identify key actors and organizations, the issues motivating them, the battles fought, and outcomes that ensued. The major events of each period are buttressed by a wealth of detail on related movements, adding breadth and depth to the principal narrative.

Their coverage might be summarized as follows.

New times confront the old order: encompassing civil rights, Black Muslims, the repeal of Fair Housing, and backlash from the Los Angeles Police Department (LAPD).

Cultural irritants: or the rise of countercultural voices, radio and free press, ban the bomb protests, and resistance by women and gays.

Rebellion: Watts; the rise of Black Power, the Black Panthers, and now-customary counterattacks by the FBI and LAPD; the revolution falters.

War in Vietnam, resistance at home: local, national and global opposition to the war; end-the-draft activism; the emergence of sanctuary movements.

Next-generation uprisings: frustrated youth of many colors take to the streets; Whites against curfew on Sunset Strip; Brown high schoolers demanding education reforms; and a Black Students Union, built by “the children of Malcolm X.”

Internecine warfare: Black movement factions engage in tit-for-tat murders, torture, and terror; the distracted movement is destroyed by the FBI and LAPD; the persecution of Angela Davis.

La vida latina, Chicanismo: the Chicano movement comes of age, but stumbles because of factional disputes; LAPD and County sheriff respond with practiced brutality; Ruben Salazar, a journalist, is assassinated; the Brown Berets disband.

End-of-decade resurgences: Women’s liberation, women’s bodies, Asian Nation, and Wattstax (the Black Woodstock starring Isaac Hayes, LAPD not permitted).

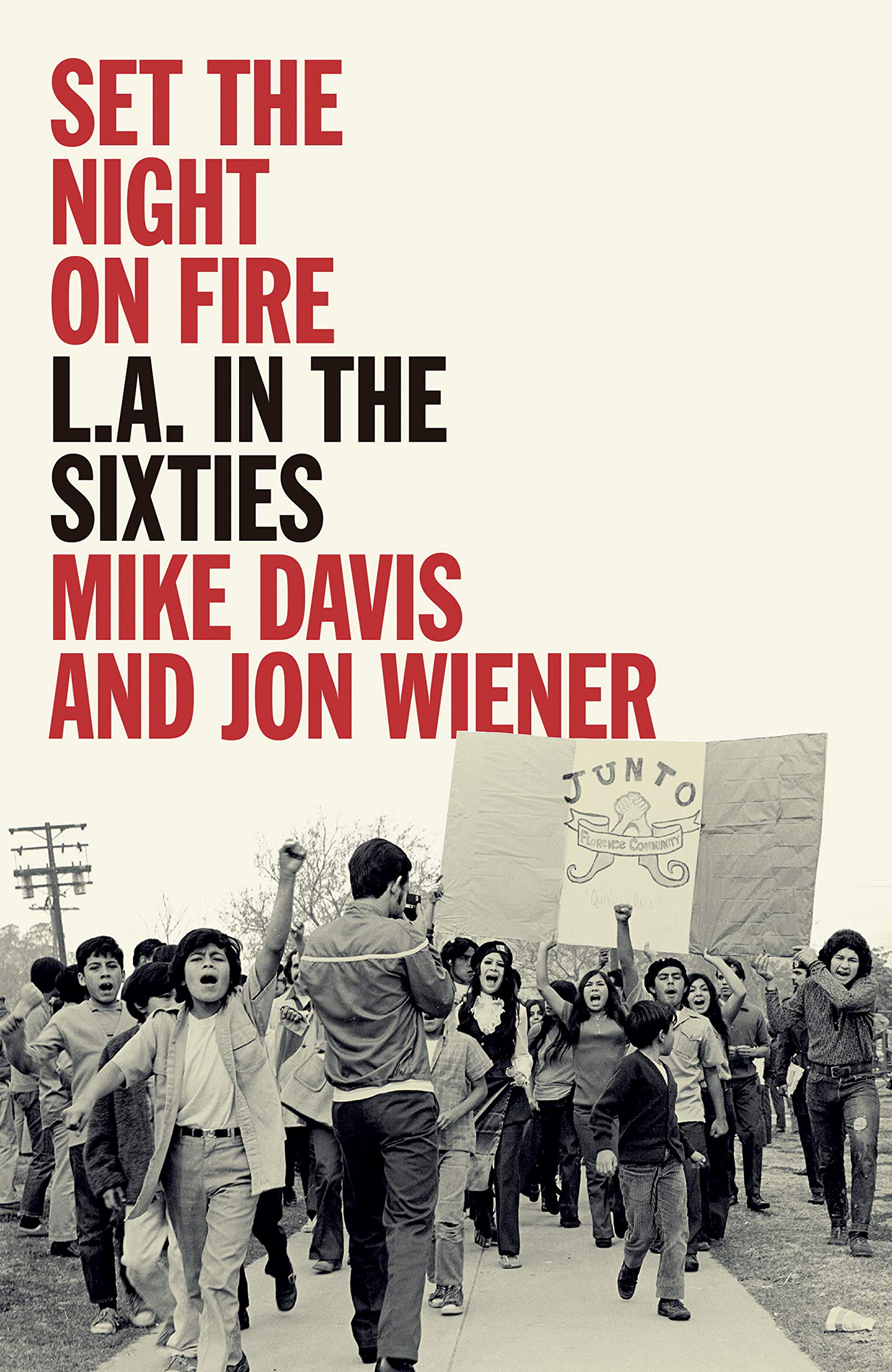

Most essays in this book are no more than fifteen pages in length. The writing style is straightforward, unadorned, accessible, and mercifully jargon-free. Each essay opens fast, punching hard and often, before clearing out for the next story. The chapters have the flavor of oral histories, because whenever possible the authors use firsthand accounts, words and voices, and reports from people directly involved. This lends an intensity and authenticity that propels the text. The book is graced by four insets of contemporaneous photographs (and two maps), putting faces on personalities and places. The entire enterprise is impeccably sourced in 100 pages of endnotes and a thirty-eight-page index. (My only complaint in this regard is that the alphabet soup of organizational acronyms is so extensive that a list of organization titles would help. I am familiar with much of this history, but a list of principal actors and their affiliations would also benefit non-Angelenos.)

Set the Night on Fire is invaluable as an archive of L.A. movement history in the amazing 1960s. It successfully integrates narratives from many separate and diverse projects and peoples, showing how they sometimes formed alliances, or fought, or otherwise affected one another’s fate. Stylistically, the authors’ calling card is to draw in the reader to witness—vividly—the intense euphoria of successful activism, and the cruelty and cataclysmic betrayals that underlie defeat. They highlight one of the decade’s greatest tragedies: the demise of the Black Power/Black Panther movements, brought about by in-fighting, and concluded by federal and local police assaults. The book also documents the concurrent emergence of many other significant movements. As a comprehensive synthesis of a decade of political action told by insiders with firsthand knowledge, Set the Night on Fire is unlikely ever to be superseded. It will certainly have a long life as an archival source, reference book, history, textbook, and handbook for grassroots organizers. Many will read it not only for inspiration, but also for cautionary practical advice.

Readers, including those who are familiar with Los Angeles, will enjoy tracing the book’s themes across time as the text unfolds from chapter to chapter. Its extended account of discrimination against and persecution of L.A.’s black population is the backbone of the book’s odyssey. This story tracks from early optimism, through belligerent resistance, to defeat and despair. Along the way, we meet Malcolm X, Stokely Carmichael, Eldridge Cleaver, and others; read a daily diary of the pivotal six days of the 1965 Watts Rebellion; observe with frustration as Black Power and Black Panther leaders fail to make common cause; and then stare numbly at the carnage that killed the fractured movement, engineered by the FBI and a newly militarized LAPD.

The rise of women’s movements is a thread I enjoyed pursuing. The narrative begins promisingly in 1961 with the growth of the Women’s Strike for Peace, whose members sought to contain nuclear warfare. The Marxist-inspired Black Power and Black Panther movements were generally unkind to women, however. Females were told to defer to male leadership, and were even required to take their meals only after men had eaten. When forceful female leadership emerged (Angela Davis was one of many), male leaders of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) objected to the uppity “matriarchy.” Not long after the subsequent flare-up, SNCC’s L.A. and national offices withered away.

Shorter threads in the book highlight emergent movements that subsequently promoted great changes. These include gay street protests, underway in L.A. two years before New York City’s fabled Stonewall moment. The L.A. Gay and Lesbian Center was opened in 1971, but women soon struck out independently to advance their cause. The mid-1960s walkouts (known as “blowouts”) by Mexican-American high school students anticipated the rise of the Chicano movement and the end of cozy alliances between conservative Latinos and right-wing L.A. mayors (although it would take another four decades for the city to elect Antonio Villaraigosa, its first Latino mayor).

There are villains aplenty in the Davis and Wiener chronicles. During the 1960s, a devilish version of law and order was practiced by an Alliance of Four: the LAPD, the reliably reactionary Los Angeles Times, the city’s right-wing mayors (especially the notorious Sam Yorty), and the ultraconservative Catholic Church personified by Cardinal McIntyre. The LAPD towered over everyone. They had guns, legal authority, and trigger-happy leaders with a propensity to launch murderous attacks on anyone who stepped over their lines. (Perversely, this seems the right moment for me to mention that the book is not without humor. For instance, when anticurfew demonstrators on Sunset Strip were joined by entertainment industry stars, the authors record the arrival of Sonny and Cher “dressed like high-fashion Inuit in huge fleece parkas.”)

In a brief epilogue, Davis and Wiener consider the legacies of the 1960s, and gesture toward the future. They rightly complain about the damage done by those who misrepresent (and hence devalue) the 1960s as a period of dope-addled hippies, gun-toting black radicals, traitorous peaceniks, and bra-burning feminists with armfuls of flowers. Such caricatures are used by the Right to deflect attention from the kaleidoscope of struggles toward freedom, equality, justice, and democracy that characterize the Davis and Wiener version of the decade.

The thirst for meaningful change will never be quenched, so it is fitting that Davis and Wiener conclude by offering the fruits of their labor to the next generation of activists. From my reading, the book offers two primary lessons about political practice: the enduring importance of resistance, whether revolutionary or the “price-of-freedom-is-eternal-vigilance” variety; and the necessity for solidarity and alliance-building among movements promoting democratic change. Whichever way you look at it, Set the Night on Fire is a monumental achievement.

References

- Davis, M. 1990. City of quartz: Excavating the future in Los Angeles. New York, NY: Verso.

- Davis, M. 1998. Ecology of fear: Los Angeles and the imagination of disaster. New York: Holt.