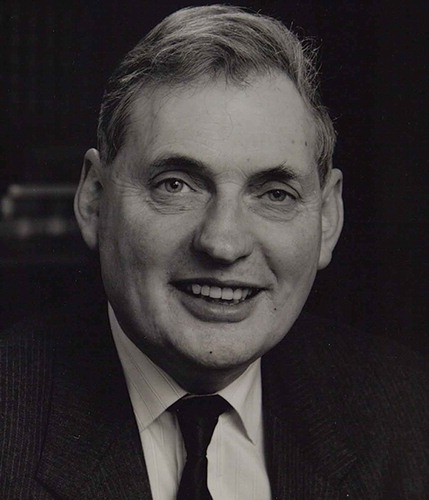

Dr Athol Murray, former Keeper of the Records of Scotland, died on 24 August 2018 in Edinburgh after a short illness. His contribution to the world of Scottish archives and historical scholarship is unlikely to be repeated. His dedication to promoting Scottish records and archives spanned a period of 65 years, helping contribute to a wider understanding and increased public use of archives. Athol’s numerous publications furthered the cause of Scottish academic research and his work promoted improvements in archival practice both in Scotland and abroad.Footnote1

Athol Laverick Murray was born on 8 November 1930 at Tynemouth, Northumberland. The son of George Murray, a bank manager, and Margery Laverick, he attended Lancaster Royal Grammar School. While still there he was invited to write a history of the school published in 1952.Footnote2 This early research experience required examination of the school’s historical records and, to his surprise, Athol discovered an aptitude for reading old handwriting and interpreting thirteenth-century Latin.

Athol obtained degrees in History and Law from the Universities of Cambridge (BA 1952, MA 1957) and Edinburgh (LLB 1957, PhD 1961). He graduated from Cambridge earlier than most, aged 21, and considered a career in the university sector or the civil service. However, he was considered too young for both at a time when graduate entry to the civil service fast stream was 22. Instead he chose to write another history, for Sebright School, Wolverley in Worcestershire,Footnote3 a wealthy establishment which then owned a large chunk of Bethnal Green.

In November 1953 Athol was appointed an Assistant Keeper in the Scottish Record Office (SRO) now National Records of Scotland (NRS) in Edinburgh. He later admitted that at the time he knew little about either the SRO or the city, his only previous visit to Edinburgh being when he attended the Glasgow Empire Exhibition as a child in 1938. Athol was interviewed by Sir James Fergusson, Keeper of the Records of Scotland, who asked whether he had read the Keeper’s annual report. It was a trick question as at that time the annual report was not published. Also on the panel was the eminent Scottish historian Professor J. D. Mackie of Glasgow University who asked about his army service. Athol had to confess that he had been excused on health grounds, but a further question about which regiment he might have served with elicited the reply ‘My father’s old regiment, The Northumberland Fusiliers.’ The answer was well-received and he was appointed, though Athol thought that his name and being a published author may also have helped.

On his appointment Athol was the youngest permanent Assistant Keeper by seven years. He later commented that he was paid the princely sum of £1 a day before tax, while in contrast Sir James Fergusson’s salary was £1,750 a year. But work in Register House had other advantages, not least because it was where Athol met his future wife, Irene Joyce Cairns. Joyce started work as a temporary Assistant Keeper on the same day and the couple were married at St Giles’ High Kirk in Edinburgh on 11 October 1958.

Athol witnessed dramatic change in the numbers and types of researcher who visited the SRO and used the records there. He recalled that when he first started staff would always outnumber readers. In the 1950s, there would be six Assistant Keepers, an executive officer, a clerical officer and two paper keepers (archive attendants) working in The Historical Search Room. Readers were mainly regular clients with perhaps only two or three new readers attending a week.

The big change came in 1965 when readership figures shot up. They had started to build following active engagement with the universities under Dr John Imrie, then Curator of Historical Records, later Keeper of the Records of Scotland. Also genealogy had become more popular. In 1961 statistics for The Historical Search Room show that there were 344 readers (2,242 attendances). But by 1967 the figure had nearly doubled to 625 readers (3,823 attendances) though the study of family history (68) remained well below that of geographical studies and local history (132).Footnote4

When Athol started, catalogues were not on public view. Only the printed indexes and published books on records were made available, so readers relied on the expertise and knowledge of the archivists. Along with his colleague, Grant Simpson, Athol was instrumental in developing a new thematic alpha-numeric cataloguing schema for the SRO’s growing collections. Still in use today, this allowed researchers to use and interpret the catalogues much more easily for themselves. In later years the schema made it easier for a new generation of archivists to convert the catalogues into an electronic form.

Promoted to Deputy Keeper in 1984, Athol became Keeper of the Records of Scotland in 1985, holding the post until he retired on 31 December 1990 after 37 years of service. Following retirement, in 1991 Athol was commissioned by the Jersey Heritage Trust to report on the Island’s archives.Footnote5 His report led to the States of Jersey setting up the Jersey Archives. In 1997 he led a team to report on the Hong Kong government archives just before handover to China.

A priority of Athol’s time as Keeper of the Records of Scotland was to secure proper archive accommodation for the SRO’s rapidly expanding collections. During the 1960s the SRO had changed from being a passive recipient of records to an active participant in their management, review and disposal. The organization faced a massive increase in its records intake, particularly from government departments and the courts. Athol helped to introduce schemes for the review of records of the Scottish Office, Court of Session (Scotland’s supreme civil court) and sheriff courts, which reduced accessions to more manageable levels by disposing of records that were of no permanent historical or evidential value.

As General Register House filled up, temporary buildings were frequently used, something common to many archives of that era. The conversion of the former St George’s Church on Charlotte Square temporarily answered the pressing need for proper accommodation and storage. Work to convert the church began in 1968 and it was officially opened as West Register House (WRH) on 2 April 1971.

Athol worked in WRH for many years. He recalled that once the building was occupied and open to the public ‘Disnaeland’ syndrome set in – ‘this disnae work and that disnae work.’ Minor roof leaks were a constant problem and though the record stores were climate-controlled the search room was not. With large sealed windows and looking onto an open exhibition area, conditions there were so unpleasant that an air-cooling system had to be installed in 1973.

It was soon found that WRH was not big enough as it filled up faster than originally anticipated and was not adaptable to the changing needs of a modern archive. Work started on planning for an interim record store, as a new-build on the site of the old Sasine Office premises next to General Register House. But by the time all government departments had left, proposals for a new archive building had fallen victim to public expenditure cuts.

With that background, Athol used his period as Keeper to ensure that storage of the nation’s public records was secured for many years to come. Before he retired, he obtained government funding to construct a purpose-built archive building on the outskirts of Edinburgh, Thomas Thomson House, and saw it open under his successor Patrick Cadell in 1994.

Underpinning Athol’s work as Keeper was an unrivalled knowledge of the records in his care. Set beside each other, the records he was responsible for would stretch from Edinburgh to Glasgow, yet it seemed to colleagues that he had opened almost every box and assimilated their contents. He worked on the papers of several Scottish landed families that read like a Who’s Who of Scottish landed estates – Agnew of Lochnaw (GD154), Borthwick of Borthwick (GD350), Drummond Castle (Earl of Perth) (GD160), to name but a few.

But his particular research interest was the records of the government of pre-Union Scotland. A difficulty for all scholars of early Scottish history is the variable nature of the surviving source material. Archivists and researchers know that record series tend to be incomplete, inconsistently compiled and nothing can be understood quickly. Athol’s strength as a scholar lay in his masterly grasp of arcane procedure, particularly that of the Scottish Exchequer, which presented particular challenges. When he started work on that vast collection in 1957 much of it was still unsorted and the contents unknown. His initial work on the Exchequer records resulted in his PhD thesis (1961). Over 60 years later, while working as a volunteer, he was still engaged in bringing order to remaining pockets of the material, earning the gratitude of many of his successor archivists.

In his final years in the SRO, Athol turned his attention to the records of the Lords of Council and Session, the predecessor of the present Court of Session. For over a century researchers had to use the records as prepared for binding under the direction of Thomas Thomson, Deputy Clerk Register from 1806 to 1841. Athol saw that Thomson had re-bound the volumes according to how he had (wrongly) assumed cases were dealt with. Athol’s explanatory notes remain a key resource for researchers, both on this and the Exchequer records.

His recognized expertise, knowledge, and understanding of Scottish charters and the Scottish chancery in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries meant that Athol was invited to give oral or written testimony in a number of cases establishing correct title. They included the viscountcy of Oxfuird (1977), the earldom of Selkirk (1996) and the barony of Dairsie (1996). He worked on forgeries penned at Glenluce Abbey in 1560, which included a genuine seal attached to a forged charter and the altered text of another sealed document.Footnote6 More recently Athol worked on a Court of Session court case of 1549 relating to the forgery of an instrument of sasine which helped establish the chiefship of The Clan Buchanan (2018).Footnote7

Athol collaborated on many projects to the benefit of the research community. He was a mainstay of an important project to produce a list of post-holders in the dioceses of the medieval Scottish church, an electronic edition of which was completed and prepared for online publication just before his death.Footnote8

Athol also appreciated the slightly quirky. He showed this in a short essay about official payments made for nearly a century from 1715 to maintain a resident cat in the Exchequer Office to prevent the records being eaten by rats and mice.Footnote9 Both this and his extensive list of academic publications remain essential reading for historians and students of medieval and early modern Scottish history.

Beyond his work for the SRO, Athol’s interests ranged widely. He was a Fellow of the Royal Historical Society (David Anderson Berry Prize 1971), a Fellow and former vice-president of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, and a founder member and former chairman of the annual Conference of Scottish Medievalists which first met in 1958. He missed only one Conference and at its 2018 meeting entertained members to memories of its early years. He was also a member of the Scottish Records Association and secretary (1957–1977) of the Scottish Record Society.

He was a stalwart of Society of Archivist conferences, frequently enjoying the après conference activities as much as the papers themselves. At one event he treated colleagues to a full rendition of the folk song ‘Blaydon Races,’ beloved of all Newcastle United FC supporters, some 20 verses of it.

Athol was a great raconteur of stories. Younger colleagues, some of whom were not even born when he retired as Keeper, were greatly taken by his reminiscences, dry wit, and pithy observations. One of his favourite stories concerned a former curator, J Maitland Thomson (1847–1923) who had died long before Athol came to the SRO. Recounting an office tale, he described him as ‘a wee man’ who visited the Historical Search Room with his dog. He kept the dog on a leash and when he went to the storage cupboards there to look at records, sometimes he would climb a ladder, forgetting that the dog was still attached and ‘drag the poor beast up after him.’

In November 2017, in recognition of his outstanding achievements and contribution to the world of archives and scholarship, NRS named a new meeting space ‘The Athol Murray Suite’ at WRH in his honour. It was a fitting tribute for an archivist-scholar who had dedicated his life to records and made a key contribution to furthering our understanding of early Scottish administrative history.

When asked if he had any advice for people about to embark on a career in archives, without hesitation Athol replied that it is worth it, and though there will be moments of intense boredom he was reminded of a quote by Sir James Fergusson: ‘You learn something new every day.’ By way of affirmation, Athol was still volunteering in NRS just weeks before his death, working tirelessly on his beloved Exchequer records. Athol recognized that as recruitment has widened, it can no longer be a prerequisite for archivists to have a knowledge of Latin as it had been in his day. But he was concerned that many archivists who deal with older records could no longer read the documents and struggled to interpret them. He expressed regret that the specialist traditional skills of archivists were being devalued.

A keen bowler and member of Wardie Bowling Club in Edinburgh, Athol was also a great fan of Italian opera and would attend performances regularly with his family at The Edinburgh Festival Theatre. He was a great railway enthusiast and could add extensive personal knowledge of the contents of the pre-nationalized railway collections in NRS to his archive portfolio. A lifelong reader of The Guardian, he would have been mildly amused that his obituary had appeared in The Times.Footnote10

He is survived by his daughter Helen, his son Ewan and his grand-daughter Sofia.

Notes

1. Much of this obituary is based on an interview with Bruno Longmore and Hugh Hagan, published in ‘Broadsheet’, Newsletter of the Scottish Council on Archives, Issue 28 (2013), as In Conversation with Dr Athol Murray.

2. Lancaster Royal Grammar School, A History (Cambridge 1952).

3. Sebright School, Wolverley, A History (1953).

4. Annual report by the Keeper of the Records of Scotland, (1961 & 1967).

5. An Archive Service for Jersey (1992).

6. Wigtownshire Charters, Scottish History Society (1960), nos. 66–68.

7. See confirmation of chiefship of The Buchanan https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-scotland-45518505.

8. Fasti Ecclesiae Scoticanae Medii Aevi Ad Annum 1638, Scottish Record Society (2002). Athol Murray was one of two main editors when SRS published the second printed edition. SRS intend to re-publish it in an electronic form and Athol was again one of two main contributors.

9. The Exchequer Cat, 1715 to 1842, Scottish Archives, The Journal of the Scottish Records Association, Volume 12 (2006).

10. Obituaries for Dr Athol Murray were published in The Scotsman, 20 September 2018 and The Times, 3 November 2018.