ABSTRACT

Decades of archives scholarship highlight colonial influences in archival collections as well as archival praxis. This research project explored the extent to which archives workers in the UK feel prepared and equipped to engage professionally with decolonizing archival practices. I conducted an anonymous online survey of workers across the archives sector to gauge their attitudes to different decolonizing practices in archives and their openness to participating in such initiatives. This article discusses and mobilizes my findings to suggest ways to encourage engagement with decolonizing practices across the sector. Participants were asked about their professional background and their initial understanding and feelings about archival decolonization before rating statements reflecting different decolonizing approaches and sharing final comments. Responses reflected a strong degree of openness towards different decolonizing practices, particularly increasing (digital) access and sharing ownership. There was support for change led from within the sector based on collaborative approaches, while there was some resistance to what was considered a politicizing of the issue. I propose ways forward centred on communication, collaboration, and peer support across the sector, particularly in exploring ways to accommodate decolonizing approaches into archival praxis.

Introduction

The influences of colonization extend far beyond the content of records and may be reflected in where archives are held, how they are catalogued and described, how they are made available, and to whom. As J. J. Ghaddar and Michelle Caswell put it in the introduction to their 2019 special issue “‘To go beyond’: Towards a Decolonial Archival Praxis:” ‘dominant notions of archives and the archival profession have been indelibly shaped by western imperial and colonial ventures.’Footnote1 It follows that many proposals for decolonizing archives and archival praxis offer challenges to established archival principles, such as provenance and custody, and practices, such as cataloguing based on defined record creators, owners and hierarchies. While these issues have received increasing and productive scholarly attention, it remains difficult to assess levels of awareness of, interest in and support for implementing decolonizing approaches within the archives profession. The research presented in this article explores this question.

The research was undertaken for my dissertation project as part of the MA Archives and Records Management at University College London (UCL) in 2021.Footnote2 Through a survey of workers across the archives sector in the UK it addressed the following research questions:

What are respondents’ attitudes to implementing decolonizing practices in UK archival collections pertaining to colonialism?

How do respondents’ attitudes compare with the stances of the UK government and The National Archives?

What does the data show about respondents’ openness to engaging with decolonizing practices in their own praxis? Does it reveal barriers to participation?

How do respondents perceive the challenges posed by decolonizing initiatives in archives to established archival practice?

How can the survey data be built upon to support wider engagement with decolonizing practices?

The article begins by setting out the examples of decolonizing practices with which my survey engaged and how they relate to the UK national context. I go on to explain the survey method, present my findings and offer quantitative and qualitative analysis of the data. The final section of the article suggests some ways forward in decolonial archival praxis in the UK.

This research is presented in an anti-colonial framework strongly linked to antiracist aims. This is a particularly important connection to make in acknowledging the systemic and ongoing violence of colonialism. Riley Linebaugh and James Lowry make clear that, ‘[t]hough often portrayed as benign in British popular culture, British colonialism is well documented as a racialized and racially violent system of domination.’Footnote3 Caroline Bressey also points to ‘[t]he imagined Whiteness of our [British] national archives’ as ‘one of the most blatant examples of the Whitening of Britishness.’Footnote4 Any engagement with colonial influences in archives in the UK must recognize how such perceptions of history and heritage relate to racism in the present as well as the past.

My project had the explicit aim of increasing engagement with decolonizing practices across the sector. Though limited in scope and focus, the survey produced responses that can provide a basis for outreach in the sector as well as for more extensive and targeted research, and it is with these ends in view that I offer this discussion.

Decolonizing archival practices: examples and applications

Terminology

My survey used the phrase ‘decolonization of archives’ in a broad sense to refer to processes that challenge colonial influences in archival collections and praxis through positive reparative action. However, ‘decolonization’ as a term, and how it is applied, are contested among those who support the principle as well as those who oppose it. Some object to a politicized understanding. Others consider the term misleading as it is not possible to ‘decolonize’ colonial collections in the sense of removing colonial influences from them.Footnote5 It is also rightly pointed out that the word may suggest that colonialism belongs to the past when this is manifestly not the case. Reflecting in 2019 on the state of archival decolonization in the Netherlands, a country that, like the UK, has a long history of colonial exploitation of other parts of the world, Michael Karabinos questioned whether ‘the archival institution of the land of the colonizers’ should ‘wave around’ a word like ‘decolonization’ in reference to its own praxis.Footnote6 In addition, Eve Tuck and K. Wayne Yang in their 2012 article “Decolonization is not a Metaphor” raised concerns about what they describe as ‘the easy adoption of decolonizing discourse’ to ‘[supplant] prior ways of talking about social justice, critical methodologies, or approaches which decenter settler perspectives.’ Writing with reference to the sovereignty of Indigenous peoples in the United States, they state that: ‘When metaphor invades decolonization, it kills the very possibility of decolonization; it recenters whiteness, it resettles theory, it extends innocence to the settler, it entertains a settler future.’Footnote7

The research I present here is intended to explore practical forms of action that can and should be taken by archivists working in the ‘land of the colonizers’ with the intention not to ‘extend innocence’ as Tuck and Yang warn but to find channels for shared responsibility. I embrace Karabinos’s notion of ‘an ongoing attitude that must be held by those dedicated to altering the colonial structures within […] archives.’Footnote8 I readily acknowledge the complications of using ‘decolonization’ in the way my survey did and indeed my phrasing met with challenges from different sides of the debate in survey responses. Within this article, I have therefore given preference to phrases such as ‘decolonizing practices’ to emphasize that I am referring to processes of engagement with existing toxic influences with a view to, as Ghaddar and Caswell put it, ‘[helping] us imagine both a different way of archiving and a different world to be archived.’Footnote9

Scholarship

The case for a reparative role for archives and archivists has been powerfully made by Lae’l Hughes-Watkins and Anna Robinson-Sweet among others.Footnote10 Scholarship around decolonizing archival practices is often characterized by a critical rethinking of existing praxis to disrupt oppressive structures. My survey focused on three practical approaches with which archives workers can engage directly: repatriation, digitization and participatory initiatives.

Repatriation

Ownership, of archives as well as land, is a key demand for decolonization and reparation. Since 2011, the question of archival repatriation has been widely discussed with specific reference to the ‘Migrated Archives’ in the UK, an example of the widespread removal of records by agents of the British government from formerly colonized countries.Footnote11 A position paper adopted unanimously by the Association of Commonwealth Archivists and Records Managers (ACARM) in 2017 resolved that:

archives removed from British dependencies on the eve of their independence form an important part of the archival record of the independent states. Ways should be found to secure their repatriation to those states, or to make copies available free of charge.Footnote12

In the case of the Migrated Archives, this resolution remains unmet, and the former colonizing nation retains custody and control over the records as the UK government continues to resist appeals for repatriation.Footnote13 A section has been made available at The (UK) National Archives in London but, as historian of West Africa Tim Livsey points out, even these

… remain effectively inaccessible to many researchers in the countries from which they were removed [who] can be hampered by limited research budgets, as well as Britain’s arbitrary and harsh visa regime. The racialized politics of the migrated archives’ removal […] therefore still shapes access to these documents decades later, in ways that disadvantage researchers from the Global South.Footnote14

Digitization

Sue McKemmish, Tom Chandler and Shannon Faulkhead make their case for a digital postcustodial approach to Indigenous Australian heritage by noting that

the traditional collecting archive model, which dis-embeds records from their living contexts and preserves them for future access in custodial, institutional settings, [is] a legacy of colonization and the persistence of the knowledge structures of colonialism into the 21st century.Footnote15

Digitization is often raised as a productive way of challenging established notions of archival ownership and custody as digital postcustodial initiatives can increase access and relax the associations of records with particular repositories and owners. In 2002 Jeanette Bastian, discussing migrated archives taken from the US Virgin Islands by colonizing nations Denmark and the United States, called for a ‘further step in the evolution of postcustodial theory [to] expand the recognition of access as a primary responsibility of the custodian.’Footnote16

More recently, however, scholars have noted with concern that digitization may sometimes undermine initiatives for repatriation. Charles Jeurgens and Michael Karabinos point to the Netherlands’ decision to digitize records belonging to Suriname prior to returning them, a process during which the former colonizing nation retained a position of power through its custody of the records.Footnote17 Linebaugh and Lowry state:

… Ghaddar’s assertion that “ … the archives cannot be decolonized so long as the land is colonized” arguably also holds true when reformulated: the land cannot be decolonized so long as the archive is colonized. Among many other abuses that call for redress, we will not have reached a time of true post-coloniality until what was taken has been returned.Footnote18

Participatory initiatives

At present participatory initiatives in institutional archives often centre primarily on the description of archives and records with affected individuals and communities contributing their expertise. It can be possible to take this approach with relatively few challenges to established praxis in terms of, for example, archival custody. However, the direct involvement of affected peoples, nations and communities in decisions made about archives is essential in each of the three approaches addressed here. Both access and representation are crucial for any participatory initiative to succeed.

Challenges to established practices

Archives practitioners may respond in different ways to the approaches described above and the challenges they offer to the principles and practices that have been central to traditions of training in ‘western’ archival practice, established by such foundational texts as Samuel Muller, Johan Feith and Robert Fruin’s Manual for the Arrangement and Description of Archives (1898) and Hilary Jenkinson’s Manual of Archive Administration (1922). While many archives professionals may be ready to embrace change in this as they have been in many other areas that have already helped to make archives more accessible and equitable, the best ways of engaging with decolonizing archival practices may not always be obvious. My survey therefore offered statements based on the different practical methods and approaches outlined above to assess how open participants are to the challenges they entail.

It is important at this stage to note the absence of contemporary scholarship that argues against decolonizing initiatives in archival praxis. It is likely that scholars and practitioners who do not feel invested in the subject may not engage with it professionally; but certainly published scholarship tends to support decolonizing practices. By engaging directly with workers at different levels across the archives sector, this research therefore also seeks to discover why participants may be opposed to decolonizing approaches to archives. This will be valuable both as a step towards redressing a potential gap in knowledge within the sector and to inform ways of engaging the entire profession with decolonial aims and practices that are constructive for all participants.

UK national context

My survey focused on UK national archival collections that pertain directly to colonization by the United Kingdom. This was intended to encourage respondents to give their professional opinion while minimizing personal complications because, firstly, the role and impact of colonialism in these collections is beyond question and, secondly, participants were less likely to feel that their personal workplace praxis was directly under interrogation.

The primary repository for UK national and governmental archival collections is The UK National Archives (TNA). As noted above, it is also known to hold migrated archives to which nations formerly colonized by Britain have laid claim. TNA is a state body that must comply with government decisions. It has committed to pursuing a policy of inclusivity, as reflected for instance in the “Archives for Everyone 2019–2023” plan on its website. On 9 June 2020 TNA reacted to ongoing Black Lives Matter protests by publishing on its website ‘a message about racial equality’ signed by Chief Executive and Keeper Jeff James. It promised that: ‘We will become more aware. We will listen. We will strive to be better so that we can wholly reflect and represent the society we serve.’ Nevertheless, no institutional commitment to decolonizing or reparative archival practices has been made.

My assessment of survey respondents’ attitudes takes into account both the scholarly and professional contexts outlined above and the UK’s national position as combined influences on the professional judgement and decisions of archives workers.

The survey

The data presented in this article was gathered through an online survey open to anyone working in archives in the UK. The digital format allowed for nationwide research that avoided restrictions on travel and personal contact in the coronavirus pandemic. Anonymity permitted respondents to be candid in their opinions on a potentially controversial and emotive subject.

The survey was distributed through sector-specific professional channels such as the Archives-NRA JISCmail and through Twitter, targeting archives organizations such as the Archives and Records Association (ARA) and specific archives and individuals with an interest in archival praxis. The survey itself opened with a consent statement (question 1) followed by filtering questions (questions 2 and 3) to confirm that the respondent worked in the UK archives sector. A set of contextual questions then established the nature of their archives service, the length of their experience and their level of seniority in the sector (questions 4–6).Footnote19 Next, participants were asked about their knowledge and understanding of ‘decolonization of archives,’ how important they felt it was, and whether the UK should engage with it (questions 7–10).

The second section of the survey consisted of 10 statements representing different decolonizing approaches to archival praxis, with responses on a scale of ‘Strongly agree’ to ‘Strongly disagree’ (questions 11–20). These questions worked to indicate the levels of importance respondents attached to decolonizing practices in archives and how open and supportive they felt towards the different approaches presented. The national stance of the UK is reflected in question 11, ‘It is enough to make national collections relating to the colonial past available for physical access in reading rooms in the UK.’ To avoid leading participants, however, it was not mentioned that the statement reflected the national position. Question 14, ‘The government of the UK should set national guidelines for the archives sector’s approach to decolonization,’ encouraged respondents to reflect on national and government involvement in decolonization of archives. The other statements were based on practical and theoretical proposals for decolonizing archival praxis as detailed in the section above. Following these mandatory questions respondents were invited to share any final comments (question 21).

Questions 8 and 21 were open questions with free-text responses, inviting participants to express their opinions and understanding in their own words and allowing them to elaborate on their responses to the multiple-choice questions. Question 8, ‘Please describe briefly what “decolonization of archives” means to you,’ was mandatory but with the option of entering ‘I don’t know.’ Question 21 was optional.

As participants were self-selecting, the survey was bound to attract respondents who were interested in the subject and probably already held an opinion on it. Floyd J. Fowler notes that non-respondents in survey research are likely to be people who are not interested, refuse to answer, are not reached, or do not have time.Footnote20 Each of these factors is likely to contribute a bias to the responses received. The survey was designed to mitigate some of these issues. It was kept short at a maximum of 20 minutes. The combination of primarily closed multiple-choice questions with two open questions ensured that responding did not become tedious but participants still had the opportunity to explain their responses. Explanations of the concepts raised were provided within the survey to ensure that respondents understood the subjects on which they were asked to comment. This was intended to engage respondents with fewer preconceived ideas in order to provide insight into how people who may be less informed about or interested in the question may be approached and engaged.

No demographic data about respondents was collected. This was intended to avoid alienating respondents reluctant to provide personal data for a survey on their professional attitudes. It has meant, however, that responses do not give an indication of the extent to which, for example, the lived experience of archives workers of colour connects to their professional experience unless the respondent disclosed this in their freetext comments. Such information would have been useful for a profession where diverse identities are underrepresented and where awareness of structural racism can be lacking.Footnote21

This research is also unavoidably affected by my own bias in favour of positive reparative action to counteract the impact of colonialism in archives. My investment in this question prompted this attempt to discover where my colleagues stand and what decolonizing approaches have the most support and are deemed most feasible across the sector. To obtain candid and wide-ranging responses, I sought to distance the survey questions from my own views with statements reflecting different positions; the responses show, however, that my bias was still evident to respondents and the survey was challenged on this basis.

Findings

The survey yielded 59 completed responses. This section provides an overview of the results per question followed by an overall analysis.

Background: questions 4–6

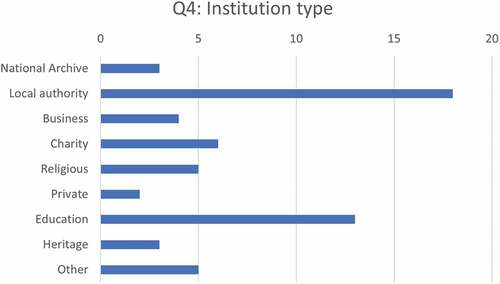

Responses to question 4, ‘Which category best describes the institution you work in?’ showed that respondents worked in a wide range of different archives (see ). The majority (18) worked in local authority archives and the second largest group (13) worked in education sector archives. Smaller numbers selected national archive (3), business archive (4), charity archive (6), archive of a religious organization (5), private archive (2) and heritage sector archive (3). The 5 respondents who selected ‘Other’ responded ‘livery company (charity, corporate, educational organisation),’ ‘Performing arts and medical archives,’ ‘Health,’ ‘for an artist,’ and ‘Specialist repository — personal (mainly political) papers, mainly 20th century. In a University setting but open to all.’Footnote22 Except the 3 who selected ‘national archive,’ then, respondents were less likely to be working directly with the kinds of UK national archival collections under discussion in the survey, but freetext responses showed that most still related their answers to their own workplaces and praxis.

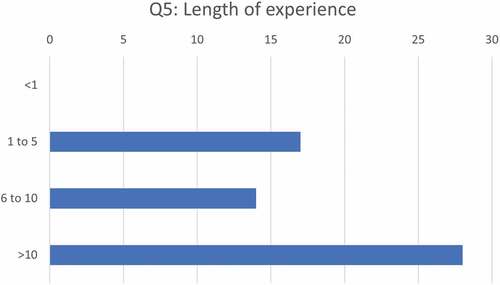

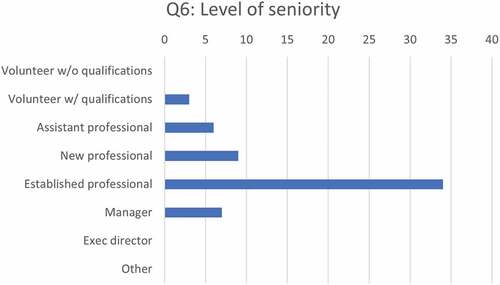

Responses to question 5, ‘How long have you worked in the archives sector?’ indicated that none of the respondents had worked in the sector for less than one year (see ). Seventeen had between one and five years of experience, 14 between six and 10 years, and 28 over 10 years. In response to question 6, ‘Which category best describes your level of seniority in your workplace?’ (see ), the vast majority (34) described themselves as established archives professionals. There were three volunteers with archives experience and/or qualifications, six assistant professionals, nine new professionals and seven archives managers. No executive directors participated in the survey.

Responses thus gave the perspectives of a range of different archives workers, though established and longer-serving professionals constituted a clear majority. These respondents were likely to be very familiar with established archival practices and could give useful insights into where they felt these could and should be challenged and adapted. The lack of responses from executive directors is likely to mean fewer insights into how decolonizing practices are considered to impact on matters of resource allocation and archives management, however.

Familiarity with archival decolonization: questions 7, 9 and 10

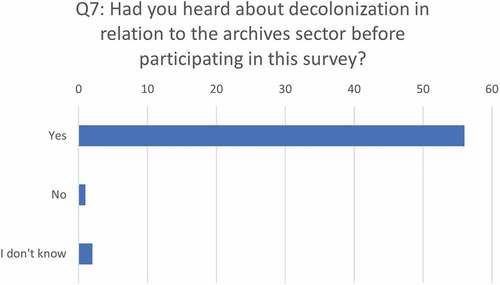

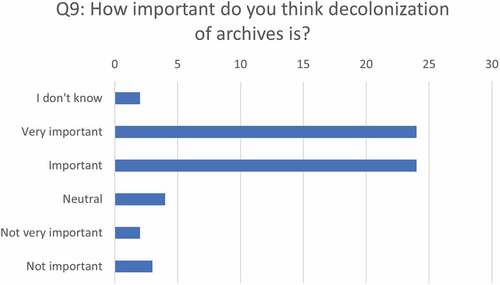

Responses to question 7, ‘Had you heard about decolonization in relation to the archives sector before participating in this survey?’ revealed that the vast majority of respondents had previously encountered the concept (see ). Just one respondent answered ‘No,’ while two selected ‘I don’t know.’ In response to question 9, ‘How important do you think decolonization of archives is?,’ a large majority selected ‘Very important’ (24) or ‘Important’ (24) (see ).

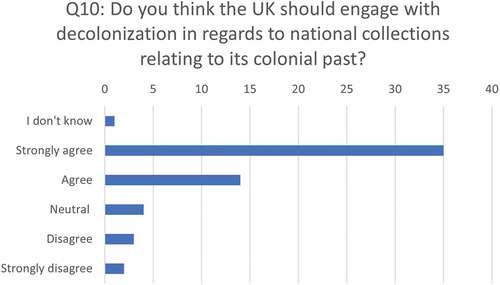

When asked specifically in question 10 ‘Do you think the UK should engage with decolonization in regards to national collections relating to its colonial past?’ the majority of respondents expressed agreement (see ). Thirty-five strongly agreed and 14 agreed.

Respondents, then, were already aware and broadly in favour of archival decolonization, though there were some who disagreed and a small number who felt unsure or remained neutral. This was expected as a questionnaire on this topic was likely to attract respondents who supported the principle as well as some who felt strongly against it. The respondents who felt unsure make an interesting group as a gauge for how engagement may be increased. Question 8 allowed respondents to explain more about what they knew and felt about the concept.

Understanding of ‘decolonization of archives’: question 8

Responses to question 8, ‘Please describe briefly what “decolonization of archives” means to you,’ fell into the following four categories:

The respondent’s level of pre-existing knowledge and understanding

The respondent’s opinion for or against

The respondent’s reflections on archival praxis in the context of decolonization

The respondent’s wider social commentary prompted by the survey theme and questions.

Several responses touched on more than one of these categories: for instance, many respondents related their reflections on archival praxis to social commentary, in which their own views and opinions were often also evident.

A. The respondent’s level of pre-existing knowledge and understanding

In this category I have included both responses of ‘I don’t know,’ which was entered by three respondents, and longer comments reflecting how respondents perceive their own understanding. two respondents gave a longer answer signalling that they were unsure. Five others indicated that they were uncertain about how decolonization could and should be put into practice. One of these stated that it seemed to range ‘from simple recognition of past actions to complete reorganisation of how everything is done.’ Some respondents referred to their own understanding of the term in ways that may also be seen as signalling their own opinions and priorities. For instance, one respondent wrote: ‘To me it means the process of recognising and acknowledging the colonial and Imperial context in which much of the archival record of modern (post medieval) Western society was created.’

B. The respondent’s opinion for or against

Although the respondents’ viewpoints on the overall question of archival decolonization were often evident from their answers, relatively few gave an explicit opinion for or against. A few used loaded terms to describe their understanding of the concept. One respondent answered, ‘Virtue signalling, I am afraid.’ Another wrote: ‘It’s about removing the “white narrative control” from the archives, but I think it’s a fairly pointless exercise in white countries.’ Others gave their views on how archival decolonization should be approached. One respondent, as part of a longer answer, stated: ‘One key area of work must be in regard to the vocabulary in our descriptions.’ Another gave their opinion in an answer that also touched on each of the other categories in this subsection:

As I understand it, it means examining current practices and theory to highlight the traces left by colonialism. In the UK I think we are hesitant to discuss this history in relation to the present day, so active discussions are vital. Archives can uphold the power systems that create and run them so there is even greater need to find ways of dismantling the impact of those structures within the archive, especially when thinking about the current unrepresentative white majority in the workforce.

C. The respondent’s reflections on archival praxis

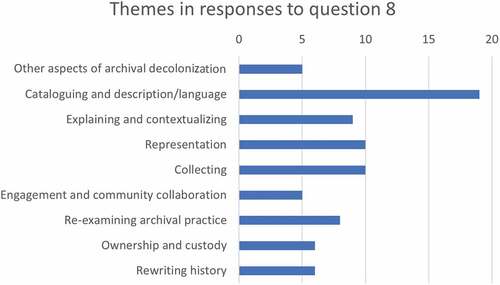

The overwhelming majority of the responses to this question referred in practical terms to archival praxis and how it should be adapted to incorporate decolonizing practices. This subsection therefore considers how often different concepts were raised (see ), as well as highlighting quotations from individual responses. Many responses indicated some level of openness to changes in archival praxis but some remained neutral and some were opposed to the changes they felt would be required. Several also raised points relating to social justice more broadly which, though they fell outside the remit of this survey, are important to consider as part of a wider context of colonial legacies. One respondent referred to the content of records, pointing out that decolonization occurred ‘mainly in the context of records relating to race and colonialism but my team also broadens the use of the term to include gender, LGBTQ+, etc.’ Several respondents also addressed aspects of the archives sector itself, with the more representative recruitment of staff and volunteers particularly being mentioned in five responses.

shows that by far the most common point across the answers related to cataloguing and description and particularly to language used (19 responses). There was also a strong emphasis on explaining and contextualizing colonial archives (nine responses). There were frequent references to recognizing and representing different perspectives or ‘voices’ in collections (10 responses). Approaches to collecting, both with regard to reviewing existing collections and how they were acquired and to the building of new collections, were raised in 10 responses. Participatory practices and the importance of engaging and working with affected communities came up in five responses. The question of access was raised six times.

Eight respondents explicitly stated their readiness to re-examine existing archival practices and some included strong criticisms of current praxis. The respondent already quoted above with reference to broadening the use of the term ‘decolonization’ wrote: ‘Roughly, unpicking (or beginning to unpick) decades of thought processes, use of language and archival procedures which we as a profession have viewed as neutral, but are now coming to see as anything but.’ The respondent quoted under B with reference to the importance of vocabulary in archival descriptions also wrote that decolonization required ‘Questioning our own expertise, and the lingering colonial attitudes that have permitted us to classify and catalogue anything from anywhere in the world as if ours is the only valid schema.’ six respondents also questioned assumptions of ownership and custody.

Another question that arose repeatedly, being noted in six responses with mixed attitudes, was concern about the ‘removal’ of material — potentially indicating both catalogue references and records themselves — and ‘rewriting history.’ One described archival decolonization as ‘An exercise in removing or highlighting to remove, any material that may have been gifted to the archive from a source, that in today’s climate of WOKE, is deemed unsuitable for public display and/or access.’ Another, as part of a longer answer, indicated that there was ‘No need to rewrite history but to enhance captions/ catalogue to clearly state colonial connections.’

Many respondents, then, were aware of a range of decolonizing approaches to archives and most expressed themselves prepared to engage with at least some of them, although some also expressed uncertainty and even concern about changes to existing working methods.

D. The respondent’s wider social commentary

Many responses were inflected by social commentary in some form, which ranged from generalized observations to specific social problems and could be personal to the respondent or presented as more abstract. The more generalized and abstract approach is visible in the following examples. One respondent described archival decolonization as ‘Acknowledging and working to redress the ways in which the power dynamics of colonialism are reflected and perpetuated in archives.’ Another answered:

Advocates of “decolonisation” argue that the legacy of Western colonisation and colonial rule remains both pervasive and pernicious […] the argument is made that archives ought to be reinterpreted and collecting policies altered in order to redress this balance.

This response may be read as both demonstrating the respondent’s understanding but also distancing it from their own views.

Often, however, respondents’ social commentary appeared as a more direct reflection of their own viewpoint. The respondent already cited under C referred to ‘today’s climate of WOKE.’ Another described archival decolonization as ‘Completely restructuring archival processes and procedures with diversity and inclusivity in mind in order to commit to antiracism and anti-white supremacy which is pervasive in our colonialist culture.’

Reactions to statements: questions 11–20

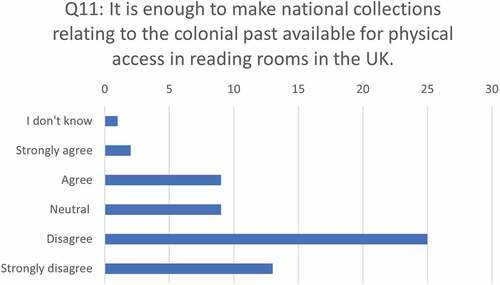

As noted above, Question 11, ‘It is enough to make national collections relating to the colonial past available for physical access in reading rooms in the UK,’ was designed to reflect the UK government’s stance. The results indicate, however, that respondents did not always agree with the national position (see ): in fact the majority of respondents disagreed (25) or strongly disagreed (13).

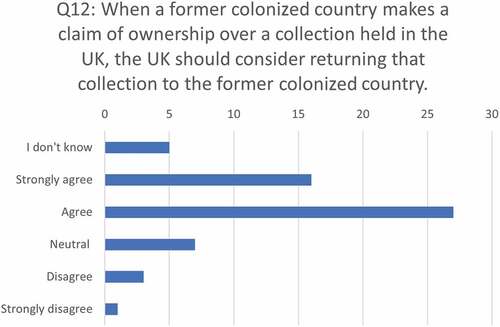

Responses to question 12, ‘When a former colonized country makes a claim of ownership over a collection held in the UK, the UK should consider returning that collection to the former colonized country,’ seemed to reflect a general openness towards repatriation: 16 respondents strongly agreed and 27 agreed (see ).

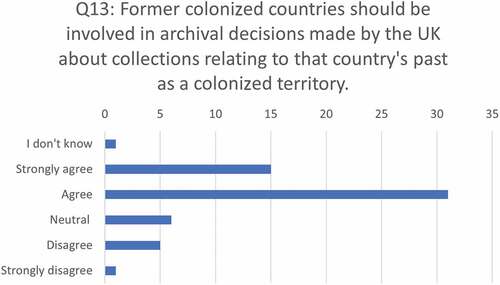

Question 13, ‘Former colonized countries should be involved in archival decisions made by the UK about collections relating to that country’s past as a colonized territory,’ received an overall positive response, with 15 respondents in strong agreement and 31 in agreement (see ).

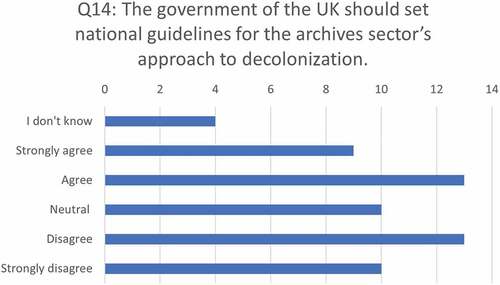

Question 14 stated: ‘The government of the UK should set national guidelines for the archives sector’s approach to decolonization.’ This statement received very mixed responses (see ). Some of these were clarified in respondents’ final comments and these responses will be more fully discussed below in the section addressing question 21. Nine respondents strongly agreed, 13 agreed, 10 were neutral, 13 disagreed, 10 strongly disagreed, and 4 selected ‘I don’t know.’

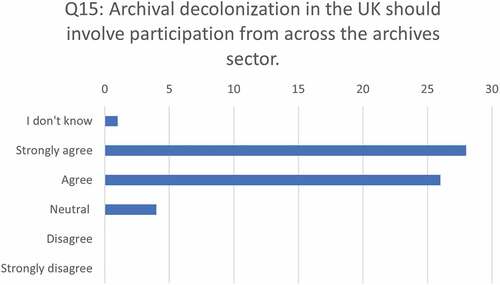

Respondents agreed with question 15: ‘Archival decolonization in the UK should involve participation from across the archives sector.’ Twenty-eight were in strong agreement and twenty-six in agreement; there was no disagreement at all (see ).

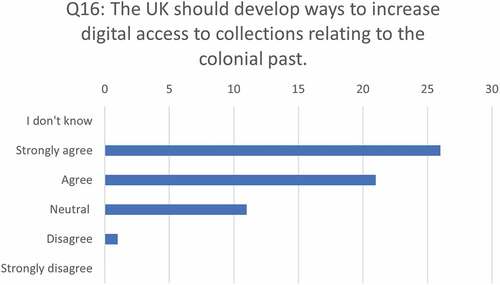

Question 16, ‘The UK should develop ways to increase digital access to collections relating to the colonial past,’ received significant support (see ). 26 respondents strongly agreed and 21 agreed; again there was no disagreement. It is probable that this was the least controversial option as it poses the least overt challenge to the principle of custody.

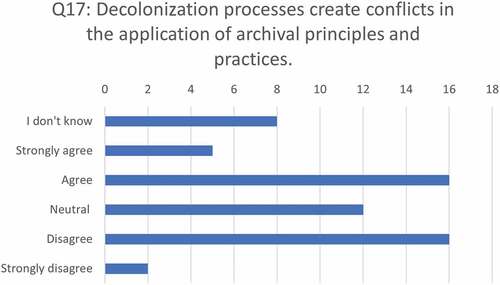

Question 17, ‘Decolonization processes create conflicts in the application of archival principles and practices,’ received a wide distribution of responses (see ). Five respondents strongly agreed, 16 agreed, 12 were neutral, 16 disagreed, two strongly disagreed, and eight selected ‘I don’t know.’

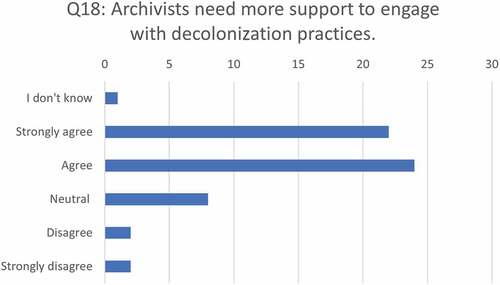

Overall, there was a tendency to agree with question 18, ‘Archivists need more support to engage with decolonisation practices’ (see ). Twenty-two respondents strongly agreed and 24 agreed. Several developed this point in their final comments, and this is considered in the analysis of responses to question 21.

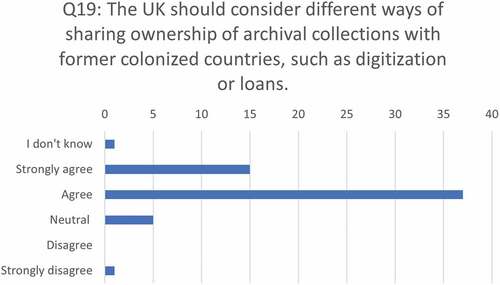

Question 19, ‘The UK should consider different ways of sharing ownership of archival collections with former colonized countries, such as digitization or loans,’ again met with overall approval (see ). Fifteen respondents strongly agreed and 37 agreed.

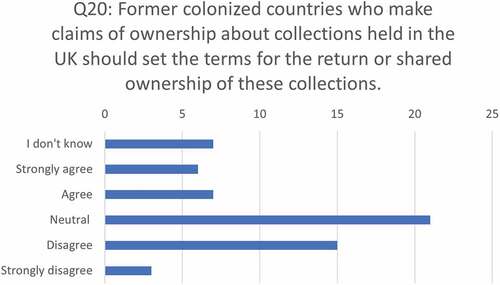

Question 20, ‘Former colonized countries who make claims of ownership about collections held in the UK should set the terms for the return or shared ownership of these collections,’ was the final and most radical statement and received mixed responses (see ). The largest group of respondents (21) remained neutral; the next largest group (15) disagreed.

These results suggest that the majority of respondents were open to changing their praxis to engage with different decolonizing initiatives. Respondents were particularly positive about increasing access or sharing ownership, especially where this included digital options. There was also an element of uncertainty about certain statements and strong objections to some, however. Overall there was an indication that more support would be welcome.

Final comments: question 21

Question 21 invited any final comments. Because it was optional, fewer respondents (32) answered. Responses to question 21 are categorized as follows:

(E) The respondent’s evaluation of the survey

(F) Clarification of the respondent’s own responses to earlier questions

(G) The respondent’s wider social commentary prompted by the survey theme and questions

(H) The respondent’s suggestions for how the archives sector should proceed.

E. The respondent’s evaluation of the survey

Eight respondents commented on the content of the survey, making justifiable criticisms that I have tried to address in this article. One noted that this complex issue could not be covered in a simple survey. Another stated that ‘Unfortunately some the questions in this survey are heavily loaded.’ The remainder related to terminology. One pointed to the survey’s use of ‘the term “uk” where the constituent nations of the uk have very different histories of colonialism which necessitate different approaches.’ Two commented on what they saw as the survey’s elision of decolonization with repatriation of archives, and two questioned the efficacy of ‘decolonization’ as a term. One of these suggested that ‘really archives cannot be decolonised. They will always exist in the context of their creation.’ The other stated that ‘“D. of A.” may have legitimate claims […] but with itspolitical annotations I would avoid the phrase itself.’

F. Clarification of the respondent’s own responses

The two key themes in respondents’ clarifications of their own responses related to a lack of support within the sector, firstly in funding and resources, and secondly from the government more generally. Three mentioned that their answers were inflected by their awareness that smaller repositories lacked the resources to participate in decolonization. Four noted that they had chosen options disagreeing with government involvement because they felt the present UK government should not lead on decolonizing strategies. One respondent reflected on how the survey had influenced their own understanding, indicating that: ‘Making records relating to formerly colonised countries available to access in those countries is an aspect of decolonisation which I had not previously thought much about, but I do agree that that in particular should be a priority.’

G. The respondent’s wider social commentary

The social commentary that this question elicited added to the criticism of the present UK government already noted under F. Altogether six respondents included criticism of the government’s stance towards confronting the UK’s colonial past. Two others pointed to the lack of diversity and issues with representation in archives. One of these focused on archival collections and the other on problems in the archives sector itself.

H. The respondent’s suggestions for how the archives sector should proceed

The overwhelming majority of respondents suggested ways forward for decolonizing archival praxis. The most common theme for respondents related to resources to enable archives of different sizes to engage with decolonizing approaches. One suggested that ‘A small national fund for creation of finding aids may be all that is required.’ Two pointed to the difficulties smaller organizations might face without additional support. Another stated that ‘The UK government should help to fund this process but should not dictate policy from the centre.’ Three indicated that national guidelines would be welcome but should be produced by the archives sector rather than the government.

Repatriation was raised by four respondents. Of these, one stated: ‘I understand that it can be complicated to verify claims of ownership, but it should not be used as an excuse to avoid repatriation.’ Another explained: ‘I don’t think every collection should be returned but I do believe that there has to be a process to challenge the rights over a collection and it needs to be open and accessible to all,’ before going on to note that this work is time-consuming and expensive. The third stated: ‘Your “decolonisation” is repatriation. Provenance is key; records should not be repatriated but we should explain their context.’ This respondent also pointed out that this was hindered by resource constraints. The fourth respondent raised the question of repatriation as conflicting with archival custody. They wrote: ‘These questions suggest that decolonisation of the archives actually means handing them over to a different repository which believes it has a claim. […] my priority is the safety of my archive and then making it available to those who need it.’

The question of ‘rewriting history’ was raised again by three respondents. One expressed concern about a ‘hiding’ of national history. They argued:

UK history is exactly that, UK history. We should apologise, hide or be embarrassed to allow access to whatever collections we have as […] a country. Many European countries have pasts they would never repeat. We need to educate, explain and give understanding to the context and reasoning in which the collections were created.Footnote23

A different approach was reflected in the answer of another respondent who wrote that, through decolonization, ‘we are not re-writing history, but instead are acknowledging that previous structures exist(ed)’ so that ‘we can attempt to move forward, together.’ Another expressed concern that, because ‘Hierarchical arrangement is often so important, undoing the colonial hierarchy could hide the impact of colonialism?’

Several of the answers in different ways advocate collaboration, both across the archives sector and beyond it. The issue of access was also raised by three respondents. Two indicated that they felt archival decolonization should not be a priority compared to other issues.

Overall analysis

The survey served its purpose in providing indicative answers to the first four research questions. Respondents were generally open to different decolonizing approaches, even despite a lack of support from the UK government or leadership from TNA. This openness existed across the sector, apparently independently of factors such as the respondent’s length of experience, level of seniority or type of institution. Even among those respondents who felt the matter to be relatively unimportant, there was still support for certain approaches such as increased digital access and sharing ownership. Respondents’ resistance tended to pertain to terminology and what they felt to be unwelcome political inflections or external interference in their profession. There was also some doubt about and opposition to surrendering custody of records through physical repatriation. Important barriers to participation cited centred on lack of funding, resources and training.

It was evident that many respondents envisioned decolonization in a broad sense working at many levels across different aspects of the archives profession with, for instance, lack of diversity in the sector being cited. Respondents were noticeably divided on whether decolonizing practices caused conflicts within archival praxis. This was unexpected but gives great scope to build on different experiences. The results of this small-scale voluntary survey are no more than an indication of some archives workers’ attitudes to decolonizing practices; but the indication they give may nonetheless be read as positive and encouraging.

Suggested ways forward

A key outcome for this research responds to my final research question, ‘How can the survey data be built upon to support wider engagement with decolonising practices?’ The responses to the survey offer plenty of different productive ways in which awareness of and engagement with decolonizing archival practices may be taken forward across the UK archives sector; in this section I suggest some possible approaches.

Outreach and awareness-raising

Especially responses to question 8 demonstrated that archives workers may feel insecure about what decolonizing archival practices entail in practical terms. It is worth noting, too, that my terminology produced some resistance from participants who were not in fact opposed to all aspects of what I classed as ‘archival decolonization’ in the survey. Widespread awareness-raising across the sector would facilitate archives workers’ engaging more confidently with different decolonizing approaches. A variety of user-friendly, topic-focused formats devised by archives workers for their peers, such as blog posts or participatory discussion sessions, could be used to make the theme more accessible with practical suggestions. Potential themes include making collecting policies more representative and inclusive, revising existing catalogues, increasing (digital) access and implementing specific participatory approaches, such as those put forward by Lauren Haberstock or in the special issue Participatory Archives in a World of Ubiquitous Media curated by Natalie Pang, Kai Khiun Liew and Brenda Chan.Footnote24 Varying terminology could attract wider participation without prompting hostility. Professional networks would ideally play a key role in disseminating these projects to those who are less inclined, or have less time, to seek them out independently.

Sector-wide discussion and collaboration

The overall support for sector-wide participation proposed in question 15, combined with the strongly divided response to question 17, regarding conflicts between decolonizing initiatives and archival practices, suggest that discussion and collaboration across the sector would be both productive and welcome. Peer support would allow those who had run successful initiatives to demonstrate how they incorporated them into their praxis. This could occur in a range of settings, from digital discussions to workshops and exchanges between archives. This approach may include leadership and guidance from TNA, but not necessarily or exclusively, to avoid the suggestion that certain approaches are being imposed. Professional organizations such as ARA could facilitate an egalitarian collegial setting.

International communication networks

Responses indicated that the national context did not have a strong influence on archives workers’ attitudes. There was an overall positive response to question 13, about the involvement of formerly colonized countries in archival decisions about collections related to them. International communication could foster an increased understanding of the international situation and allow different countries to learn from one another’s approaches and claims. Lowry’s proposal for ‘radical empathy’ may offer a helpful starting point here.Footnote25 This would build an important parallel bridge to existing cross-border communication in archival scholarship, allowing for practical expertise and experience to be shared. The International Council on Archives (ICA) could be a conduit for this work.

Approaches to shared ownership could be developed in discussion between the different repositories involved in claims for repatriation. Archives workers in colonizing countries who are less informed or more hostile to repatriation and shared ownership may learn and perhaps change their views if they were able to discuss the question with archives workers from formerly colonized countries. Cross-border collaboration can be usefully instituted by individual archives, national archives, professional bodies and collectives such as Archivists Against History Repeating Itself.

Practical support and funding

While respondents were somewhat divided on question 18, whether archivists need more support to engage with decolonization, several respondents used the open questions to raise the issue of practical support and funding in particular as a significant barrier. To help archives workers regard decolonizing practices not as an optional extra but as a key element of their work, support is required to build it into their regular praxis. Alongside centrally available funding for work such as increased digitization and outreach to affected communities, this should include guidance on how to bid for funding for decolonizing initiatives as well as how to write decolonizing work into staff roles and day-to-day workflows. This is a topic on which advocacy bodies can and should lead. It is possible that TNA may be hindered in such work by the official stance of the UK government, but other professional associations can begin by offering their support in this area and making clear to TNA that there is a call for involvement.

Wider changes across the sector

It is important to acknowledge here the range of suggestions made by participants relating to issues beyond this survey’s focus on decolonizing work in national collections. Several proposed to address the lack of diversity in the archives sector itself through changes in recruitment and removing barriers to access. This is an undeniably crucial effort that should take place alongside work to incorporate decolonizing approaches into archival praxis, not least because a more diverse workforce can also increase the representation of the perspectives of affected communities in the sector. Individual archives and professional bodies can begin to take action on this immediately.

Concluding

This MA-level research project was limited in scope by restrictions on time and resources as well as my own expertise. I hope, however, that it can contribute to opening up avenues for further research and action on this important topic. While current media debates around questions of decolonization give the impression that people are taking up inflexible positions often motivated by emotion, the responses to this survey suggest that situating the debate in a professional context and offering practical support may significantly increase engagement with decolonizing practices in the archives sector.

Productive next steps for research would be to investigate and detail the required resources to support the initiatives I propose here. The cost for several of these is likely to be substantial, and a specific inventory will help to determine how costs and needs can be met. Where my research pitched a series of different, generalized decolonizing approaches which were influenced and limited by my own position and biases, a larger project could usefully investigate attitudes to specific approaches and make a detailed study of perceived barriers to participation with a view to identifying how these may be overcome.

There is a long way to go with each of these projects, and it remains important that small efforts such as those I suggest here are not viewed as ways of extending innocence to the colonizing country or as substitutes for fuller action. Ghaddar’s point that archives cannot be decolonized while colonialism exists also stands. This research gives a hopeful indication, however, of many archives workers’ willingness to act positively to take more responsibility for this issue within the archives sector.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Flore Janssen

Flore Janssen is Assistant Professor of Comparative Literature at Utrecht University in the Netherlands. She holds a PhD in English and Humanities from Birkbeck, University of London (2018). Her academic research has a strong archival focus and she has worked both in universities and in the archives sector, as Digital Humanities Project Officer at the Salvation Army International Heritage Centre in London. She was awarded her MA in Archives and Records Management from University College London in 2021.

Notes

1. I wish gratefully to acknowledge the generous help and suggestions I received for this research from Anna Sexton, James Lowry, Charles Jeurgens, Karen Macfarlane, Marie-Louise Rouget, Cameron Lyons and my former colleagues at the Salvation Army International Heritage Centre.

2. Ghaddar and Caswell, ‘To go beyond,’ 77–78.

3. Linebaugh and Lowry, “The Archival Colour Line,” 285.

4. Bressey, “Invisible Presence,” 61.

5. Karabinos, “Decolonisation in Dutch Archives,” 130–131.

6. Karabinos, “Decolonisation in Dutch Archives,” 130.

7. Tuck and Yang, “Decolonization is not a Metaphor,” 2, 3.

8. Karabinos, “Decolonisation in Dutch Archives,” 130.

9. Ghaddar and Caswell, ‘To go beyond,’ 72.

10. Hughes-Watkins, “Moving Toward a Reparative Archive;” Robinson-Sweet, “Truth and Reconciliation.”

11. Banton, “Destroy? ‘Migrate’? Conceal?”

12. “The ‘Migrated Archives,’”1.

13. Banton, “Displaced Archives.”

14. Livsey, “Open Secrets,” 111–112.

15. McKemmish, Chandler and Faulkhead, “Imagine,” 283.

16. Bastian, “Taking Custody, Giving Access,” 80, 93.

17. Jeurgens and Karabinos, “Paradoxes of Curating Colonial Memory.”

18. Linebaugh and Lowry, “The Archival Colour Line,” 296.

19. The questions chosen draw on examples from Macfarlane, “How Do UK Archivists.”

20. Fowler, Survey Research Methods, chapter 4 (unpaginated).

21. See for example Macfarlane, “How Do UK Archivists” 274–275.

22. Quotations from survey responses retain the original spelling, punctuation and grammar.

23. I read this statement as missing the word ‘not’ in ‘We should apologise’. I assume the respondent meant to write: ‘We should not apologise …’

24. See for instance Haberstock, “Participatory Description” and Pang, Kai and Chan, Participatory Archives.

25. Lowry, “Radical Empathy.”

Bibliography

- Banton, Mandy. “Destroy? “Migrate”? Conceal? British Strategies for the Disposal of Sensitive Records of Colonial Administrations at Independence.” The Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History 40, no. 2 (2012): 321–335. doi:10.1080/03086534.2012.697622.

- Banton, Mandy. “Displaced Archives in the National Archives of the United Kingdom.” In Displaced Archives, edited by James Lowry, 41–59. London: Routledge, 2017.

- Bastian, Jeanette. “Taking Custody, Giving Access: A Postcustodial Role for A New Century.” Archivaria 53 (2002): 77–93.

- Bressey, Caroline. “Invisible Presence: The Whitening of the Black Community in the Historical Imagination of British Archives.” Archivaria 61 (2006): 47–61.

- Fowler, Floyd J. Survey Research Methods. 4th ed. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications, 2009.

- Ghaddar, J. J., and Michelle Caswell. “‘To Go Beyond’: Towards a Decolonial Archival Praxis.” Archival Science 19, no. 2 (2019): 71–85. doi:10.1007/s10502-019-09311-1.

- Haberstock, Lauren. “Participatory Description: Decolonizing Descriptive Methodologies in Archives.” Archival Science 20, no. 2 (2020): 125–138. doi:10.1007/s10502-019-09328-6.

- Hughes-Watkins, Lae’l. “Moving toward A Reparative Archive: A Roadmap for A Holistic Approach to Disrupting Homogenous Histories in Academic Repositories and Creating Inclusive Spaces for Marginalized Voices.” Journal of Contemporary Archival Studies 5 (2018): 1–17.

- Jeurgens, Charles, and Michael Karabinos. “Paradoxes of Curating Colonial Memory.” Archival Science 20, no. 3 (2020): 199–220. doi:10.1007/s10502-020-09334-z.

- Karabinos, Michael. “Decolonisation in Dutch Archives: Defining and Debating.” BMGN – Low Countries Historical Review 134, no. 2 (2019): 129–141. doi:10.18352/bmgn-lchr.10687.

- Linebaugh, Riley, and James Lowry. “The Archival Colour Line: Race, Records and Post-colonial Custody.” Archives and Records 42, no. 3 (2021): 284–303. doi:10.1080/23257962.2021.1940898.

- Livsey, Tim. “Open Secrets: The British ‘Migrated Archives,’ Colonial History and Postcolonial History.” History Workshop Journal 93, no. 1 (2022): 95–116. doi:10.1093/hwj/dbac002.

- Lowry, James. “Radical Empathy, the Imaginary and Affect in (Post)colonial Records: How to Break Out of International Stalemates on Displaced Archives.” Archival Science 19, no. 2 (2019): 185–203. doi:10.1007/s10502-019-09305-z.

- Macfarlane, Karen. “How Do UK Archivists Perceive ‘White Supremacy’ in the UK Archives Sector?” Archives and Records 42, no. 3 (2021): 266–283. doi:10.1080/23257962.2021.1995708.

- McKemmish, Sue, Tom Chandler, and Shannon Faulkhead. “Imagine: A Living Archive of People and Place ‘Somewhere beyond Custody.’” Archival Science 19, no. 3 (2019): 281–301. doi:10.1007/s10502-019-09320-0.

- The ‘Migrated Archives’. Position paper adopted at the ACARM Annual General Meeting, Mexico City, November 25, 2017.

- Pang, Natalie, Kai Khiun Liew, and Brenda Chan,seds. “Participatory Archives in a World of Ubiquitous Media.” Special Issue of Archives and Manuscripts 42, 1 (2014): 1–4.

- Robinson-Sweet, Anna. “Truth and Reconciliation: Archivists as Reparations Activists.” The American Archivist 81, no. 1 (2018): 23–37. doi:10.17723/0360-9081-81.1.23.

- Tuck, Eve, and K. Wayne Yang. “Decolonization Is Not a Metaphor.” Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society 1, no. 1 (2012): 1–40.