ABSTRACT

Literature relating to education sessions in special collections has been prevalent in the field since the early 2000s. Following on from the publication of the ACRL-RBMS-SAA Guidelines for Primary Source Literacy published in the USA in 2018, this paper applies the guidelines to survey and interview responses to explore the key skills gained by undergraduates using special collections and the barriers to skills’ acquisition throughout their degree programmes. Contextualizing the results through US and UK literature, this paper argues that special collections literacy can be embedded into interdisciplinary undergraduate curricula which in turn may help special collections advocate for increased resources to broaden their education programmes. It establishes a picture of current special collections education for UK universities including range, methods of delivery and assessment styles.

Introduction

Special collections departments are a world within the world of information studies. Often seen as a microcosm of wider library activity, teams undertake a multitude of tasks across collection management, information organization, leadership, reader services, and outreach and engagement on a regular basis.

Within higher education, a key part of special collections work is encouraging students to use collections held within their institution as part of ongoing studies.Footnote1 Some students are innately keen, with material providing the instant ‘spark’ needed. With other groups however, it can be more challenging to convey the value of using historic material if they are not enthusiastic to engage with physical artefacts.

In January 2018, the Association for College and Research Libraries Rare Books and Manuscript Section and the Society of American Archivists (ACRL-RBMS-SAA) collaborated to produce a series of guidelines for archivists, librarians and other student-supporting staff working with students to develop primary source literacy skills.Footnote2 In librarianship, the concept of information literacy is well-established: the notion that there are a set of lifelong-learning skills learnt by using information.Footnote3 However, no such framework exists for special collections literacy; the guidelines developed by ACRL-RBMS-SAA are the first of their kind. In the UK, the National Archives has a dedicated scheme to develop archival research skills for postgraduates, but there is no equivalent initiative for undergraduate students.Footnote4 This article will primarily use the term ‘special collections literacy’ rather than the US term ‘primary source literacy’: special collections often contain heritage material that extends beyond primary sources, including printed books and contemporary items curated for future researchers.Footnote5

The benefits of using special collections for undergraduates are well documented; many studies cite the importance of special collections in creating a unique experience for students during their degree.Footnote6 However, academic use of special collections for teaching is inconsistent, with many humanities students having little or no contact during their degree despite relevant material being held. Recent studies focus on exploring two topics: the skills developed by students when using archives and undergraduate experiences of using special collections in their studies.Footnote7 In the UK, national benchmarking frameworks for universities — the Research Excellence Framework (REF) and the Teaching Excellence Framework (TEF) — continue to shape university strategy and output in an era of financial uncertainty.Footnote8 To date however, there has been little attempt to investigate specific skills gained by UK undergraduates using special collections.

This article will explore the following research questions: what are the skills undergraduates can gain by using special collections during their degrees and what are the barriers to acquiring these skills?

Special collections literacy: background and context

Between 2000 and 2015, a shift in archival research occurred towards the role of special collections staff in education for students and academics.Footnote9 This reflects pedagogical developments in universities; since the 1990s passive learning methods have been replaced with active styles where students collaborate and participate in classes.Footnote10 In 2021, Tanaka et al. published a significant report into teaching with primary sources, focusing on the needs of instructors.Footnote11 Garcia, Lueck and Yakel recently analyzed literature investigating pedagogical research with primary sources and noted that publications on the topic have existed since 1949 and peaked in volume during 2012.Footnote12 They note that there is a lack of literature relating to effective evaluation methods with primary source teaching; further research must be undertaken in this area.

Using objects helps create a memorable experience that students are likely to recall.Footnote13 The literature frequently discusses case studies of a course interacting with special collections to support project work or explore collections.Footnote14 When combined with innovative pedagogy, special collections staff work with academics to develop unique and innovative courses for students.Footnote15 However, collections must be visible to researchers, students, and the public.Footnote16 Partnership across all staff involved in the educational experience is key for long-term literacy success.Footnote17

The 2008 USA Boyer Report triggered a wealth of literature published on teaching using special collections materials.Footnote18 By analyzing a questionnaire sent to ACRL members, Allison (Citation2005) established a US-wide picture of undergraduate special collections use, particularly educational practices.Footnote19 Brown investigated information literacy in university special collections via questionnaires and interviews, and Clough explored undergraduate special collections use through surveying students.Footnote20 In 2020, Watson and Patrick published an impact study of pedagogical practice using special collections including a document identification form designed to help students navigate using collection items.Footnote21

Special collections undertake various education methods, including inductions, supporting teaching topics, themed assignments and independent research.Footnote22 Inductions usually include an overview of access procedures and an introduction to the department and its collections.Footnote23 However, Duff and Cherry note there has been little research investigating the impact archival induction sessions have on students.Footnote24 The existing literature suggests the traditional ‘show and tell’ type induction is ineffective.Footnote25 The most the single-session induction can achieve is making students aware of the department’s existence and build confidence using material.Footnote26

For many undergraduates, visiting their institution’s special collections is their first ever encounter with an archive.Footnote27 It may be the first time they understand how academics research — especially in humanities disciplines.Footnote28 For undergraduates to learn effectively using primary sources, assignments and sessions must be scaffolded across the term (rather than in one final assessment).Footnote29 Undergraduates must link special collections to individual educational goals to understand their value, which is particularly true in today’s digital environment; students are unused to understanding items’ physical materiality.Footnote30

To use special collections material effectively, students must know how to access the department and make an appointment, locate collections of items using finding aids, handle material safely, and integrate it into research. Because the range of skills students need to understand special collections material is complex, it is better to teach students over several sessions within smaller groups.Footnote31 Matheny notes that it is often more effective to use a small, curated selection of special collections material rather than overwhelm students with a broad range of items.Footnote32

For undergraduates, the academic is responsible for introducing students to the role of archives in their studies.Footnote33 When supporting taught courses, liaison between special collections staff and academics is key, especially if assessment is involved.Footnote34 Inviting researchers to talk about their work in special collections can be a useful way of developing skills and creating a community of interested parties.Footnote35

Information literacy research can inform special collections about student needs, particularly in relation to undergraduate behaviour and information seeking. D’Couto and Rosenhan examined four attitudes students brought with them to research: the need for instant access and immediate gratification, technological proliferation, a desire to figure things out alone, and time pressures.Footnote36 This is supported by Baseby who notes current priorities of academic libraries focus on a self-service, online, 24/7 approach which diverges from how special collections are accessed.Footnote37

Methodology

The data collected for this paper was obtained using three methods: a literature search, an online questionnaire and follow-up interviews with selected respondents. These methods of data collection form a triangulated approach, with each method informing and validating the others.Footnote38 The questionnaire contained a mixture of matrix, multiple choice, closed and open-text questions, helping to give the project a stronger groundwork for understanding the current role special collections departments have in undergraduate education.Footnote39

The questionnaire aimed to investigate the following aspects of undergraduate use of special collections: annual numbers of undergraduates visiting special collections for education sessions; subjects studied by visiting undergraduates; frequency and type of activities undertaken in undergraduate education sessions; frequency and type of assessment methods undertaken in undergraduate education sessions; skills gained by undergraduates using special collections; barriers to undergraduates using special collections.

The survey population was established by researching which UK universities were likely to have an active special collections department.Footnote40 A survey pilot was sent to selected Information Services staff at the University of Kent in February 2019 and revised following feedback before being sent to identified participants via institutional email in March 2019.

Following the questionnaire’s closure, responses were then reviewed to identify follow-up interviews. This review amounted to a purposive, snowball sample. Pickard defines purposive sampling as ‘selecting information-rich cases for study in depth;’ here, this was defined by the response strength to open-text questions about benefits and barriers to undergraduate use of special collections.Footnote41 Semi-structured interviews were undertaken remotely. Interviewees were promised anonymity in responses and interview transcripts were offered to participants to review.

The questionnaire and interviews were analyzed using Nvivo and Excel. The starting themes (nodes) and sub-nodes for coding questions were adapted from the US primary source literacy guidelines in order to see where UK undergraduate special collections experiences matched with US guidance and to establish differences.Footnote42 See Appendix A for details on how the guidelines were adapted.

Results

One hundred and twenty-three university special collections departments were invited to take part in the questionnaire: 98 from England, 15 from Scotland, eight from Wales, and two from Northern Ireland. Sixty-one responses were received: 49 from England, seven from Scotland, and five from Wales. The response rates totalled 44%, 40%, and 63% giving an overall response rate of 50%. Following the questionnaire’s closure, five participants were contacted to schedule follow-up interviews.

Questionnaire

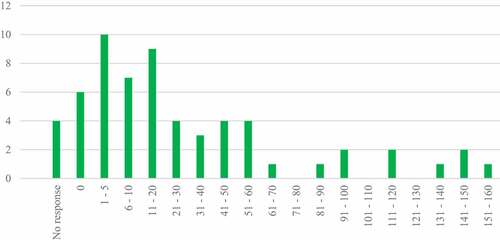

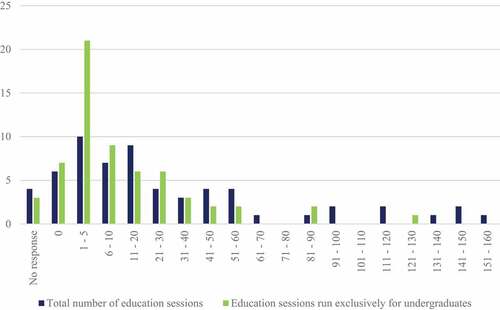

Participants were given the option to record education sessions information for either the 2018 calendar year or the 2017–2018 academic year. Responses varied greatly; some participants did not respond, some recorded zero visits and some answered both categories. Where both categories were answered, a mean was calculated. The mean rate of no response to this question was 35%. The range of total annual group visits held in special collections spanned from zero to 166, with the most common (modal value) being between one and five. The median number of education sessions offered was 22.

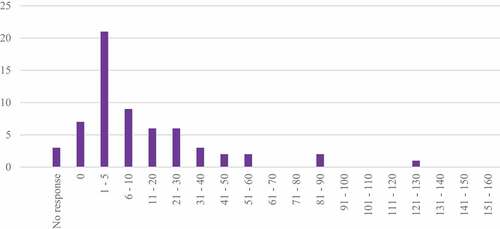

Participants were asked to record the number of sessions held in special collections over the past year run exclusively for undergraduates. The lowest number recorded was zero, the highest 129. The median number of education sessions run for undergraduates was 13 per year. Whilst the overall number of education sessions for undergraduates tended to be less than the total number of sessions run by special collections, the total range of education classes spanned from zero to 161-170.

The single most common subject studied by undergraduates attending special collections sessions was English (65), followed by History (34), and Art History (20). A significant amount of questionnaire respondents selected ‘other’ for subjects studied, suggesting the questionnaire did not comprehensively cover university courses. Analysis confirms that undergraduates studying Arts and Humanities disciplines account for most visits to special collections.

When examining methods of education sessions for undergraduates in special collections, respondents could choose as many options on the questionnaire as applicable. Subject-specific introductions were the most common method of education sessions (41), followed by course-specific introductions and one-to-one research advice (38 each). The least popular method of special collections undergraduate education was hosting pop-up sessions elsewhere (11). Other methods of undergraduate education in special collections included sessions specifically working with rare books (3), module and object-specific sessions (3) and sessions undertaken as part of wider library inductions (2).

Participants were asked to rank activities undertaken in special collections as part of undergraduate education sessions, whereby 1 = never happens (occurs 0% of the time), 3 = sometimes happens (occurs 50% of the time), and 5 = always happens (occurs 100% of the time). The most common activities undertaken in undergraduate sessions were explaining special collections’ role and purpose, identifying and examining material, and explaining rules and regulations. The least common activities undertaken were transcribing special collections material and exploring the role of staff in curation.

The most common assessment method of special collections undergraduate sessions was holding an informal discussion in the session itself followed by gaining feedback from participants afterwards. Responses highlighted how special collections view the assessment process: three participants noted that while students were subsequently assessed on using special collections material, special collections staff were not informed of results. Two participants referenced using statistics of reading room users following visits to informally assess impact.

Experience was the most discussed benefit to undergraduates using special collections (79% of participants). Twenty-six participants highlighted how special collections visits contribute to an enhanced learning experience for undergraduates, giving an opportunity to explore materials and resources they would not otherwise encounter.

For many, the chance to give undergraduates physical contact with the past contributed uniquely to students’ university time:

Handling and examining real historical objects underpins the theoretical and makes it more real for them, they start relating it to clothes they’ve seen their grandparents wear in photographs. (R18)

Creative engagement with special collections by undergraduates was also a frequently discussed topic. Twenty-nine participants referenced either the enjoyment or inspiration emerging from undergraduate visits; the ‘wow factor’ (R27, R53) helped undergraduates use special collections for ‘creative inspiration’ (R12, R37).

Other positive factors that special collections could contribute to undergraduate student experience included confidence – either self or with peers (11), improved grades (7), and additional dissertation resources (5). Sixty-nine per cent of survey respondents noted how important it was to introduce undergraduates to special collections, either to make them aware of institutional resources for forthcoming assignments (51%) or to develop confidence in using and approaching special collections in future (48%). R31 discussed how introducing undergraduates to special collections is a key part of ‘smoothing out the cliff-edge’ between undergraduate and postgraduate study. Interestingly, five participants believed that a key part of undergraduate introduction helps students to feel more at ease with approaching special collections staff – either for research help in the future, or for staff to be aware of ‘what their interests are so we can respond as a service’ (R28).

The third most common survey response related to comprehension skills undergraduates gained by visiting special collections. Forty-one participants believed that visiting special collections gives undergraduates better skills in communicating about primary sources, which in turn increases critical thinking abilities:

A better understanding of how ‘history’ is made – i.e. interpretation, sampling and repackaging of primary sources and therefore fresh eyes in which to look at secondary sources and historiography. (R31)

An average of 30 mentions were made in survey responses about the skills undergraduates gained in handling material and technical comprehension of historic items. Participants noted how visiting special collections gave undergraduates enhanced understanding of their subject (41%).

Three nodes — evaluation, incorporation, and identifying primary sources — were discussed equally by 51% of survey respondents. Participants believed being able to distinguish primary from secondary sources is crucial (58%) and a transferable skill (R26). Participants also noted how identifying primary sources allowed undergraduates opportunities to generate original research from special collections material (R6). Once primary sources were identified, students visiting special collections then gain the ability to incorporate knowledge into academic work (52%). Thirty-eight per cent believed students are more able to synthesize sources for argument.

The four sub-nodes of evaluation (assessing usefulness, context of primary sources, materiality, and primary source analysis) were discussed equally (between 27 and 31 times) by 51% of participants. Critical thinking skills gave undergraduates a deeper insight into the societal role of historic material (R59). Evaluating primary sources also includes the ability to understand historical material’s physicality, such as provenance, bindings and size (27 participants).

By using special collections, undergraduates gained the ability to find and access primary sources (discussed by 48%). Undergraduate special collections visits gave students greater knowledge of local collections (30%), increased confidence in using local archive catalogues (26%), and enhanced understanding of the differences between library and special collections material. Visiting special collections ensured undergraduates are more aware of historical records’ subjectivity (35%).

Thirty-five per cent of participants of participants thought visiting special collections improved undergraduate employability, either creatively or by gaining awareness of professional research practice and careers within the heritage sector (28% and 18% respectively). Introducing undergraduates to special collections also gave students ‘broader horizons’ (R61) when considering postgraduate study (13%). The least discussed key nodes were the institutional benefits of undergraduates visiting special collections, with 10% discussing how a visit gives students a greater appreciation of their university.

The starting themes for coding responses about barriers to undergraduates using special collections were based around the literature findings. Awareness barriers were the biggest issue for undergraduates, discussed by 73% of participants. Respondents believed students failed to understand what role special collections have within the academic library and in relation to their studies. Part of this issue stemmed from the fact that many students were not perceived to understand what an archive is, making it harder to promote initially (R6, R29). Students’ lack of special collections awareness related to failure to market the department appropriately (32%).

Environmental barriers were frequently discussed (55%). These barriers fell into two categories: physical, such as location and layout of the department, and practice, relating to how students must interact with special collections. These categories each received an average of 22% of comments, and again overlapped. Physical barriers also related to where undergraduate special collections sessions are taught, with several respondents noting the lack of space available for sessions or the impact on other special collections service areas. Undergraduates appear deterred by special collections because of technical skills required to use primary sources, discussed by 10%:

Language and palaeography/orthography - so many sources are non-English and even if in English are very difficult to interpret for students. (R31)

Another major barrier within the undergraduate special collections student experience was time pressure (29% of participants). Time issues were discussed alongside other barriers, particularly comparative convenience of online resources.

Working with academics emerged as a key theme, discussed by 48% of participants. The challenge to undergraduates was the difficulty special collections staff perceived in embedding resources into curricula (43%). There was widespread agreement among respondents about how embedding primary sources into curricula positively impacts students and likely helps to alleviate many barriers discussed.

Online barriers to undergraduate access were also common, with 38% of respondents discussing them. Barriers related to digital resources (19%) and discovery interfaces used to find special collections material (29%). Participants noted there was a big difference in single search box interfaces and metadata needed to surface special collections effectively. Respondents acknowledged specific skills are needed to locate special collections resources online that differ from finding library materials.

Institutional barriers were mentioned by 29% of participants. The most common institutional barrier was resources, particularly staffing (15%). Insufficient staffing impacts the ability of special collections universally: working on long-term impact projects including ‘subpar web pages and online catalogue design’ (R35), opening hours of services, or running education sessions at all.

Follow-up semi-structured interviews

All interviewees discussed special collections held and noted how some collections were more heavily used by undergraduates. One participant remarked on how their collection development policy attempts to reflect academic interests:

Our current collecting strengths are [list]. And they are our existing collection strengths, but they are also our priority collecting areas … we do try to align what we collect with the University’s research strengths. (P2)

There was strong acknowledgement from interviewees that undergraduate use of special collections significantly depends on academic research interests:

What we have does not necessarily match up with what the university’s trying to teach. (P4)

Interviewees noted the lack of dialogue between academic recruitment and professional services:

One of the things that is tricky is that generally academics are appointed already with a research interest, and quite often that … is based around using collections … in other institutions. (P1)

All interviewees discussed the informal nature of arranging special collections sessions for undergraduates. Sessions were largely organized when academics contacted the department, or through special collections staff developing internal connections. From the five interviewees, only one mentioned a formal process of arranging special collections sessions — academics interested in bringing students into special collections filled in an online form, which was allocated to staff.

The role of special collections staff in undergraduate sessions also varied greatly depending on the subject being taught, frequency of sessions, and liaison with academics. A variety of factors determined special collections staff roles in sessions:

It all depends on … how much dialogue we have with the module leader. And that can be nothing, or it can be a proper team effort where we work together with them. (P2)

All participants noted that undergraduate groups in special collections were built into teaching modules requiring compulsory attendance rather than drop-in sessions. Despite most undergraduate sessions being mandatory for students, one participant raised (lack of) attendance as an ongoing issue for special collections staff and academics. Three interviewees discussed the importance of academics attending sessions alongside students:

You do need to have something to try and link it in, and that’s not– with the best will in the world, our job; it has to be the academic who knows … the theoretical underpinnings that makes this relevant and makes this an example of X Y and Z. (P1)

Academics’ attendance of sessions highlights a secondary implicit issue that particularly arose during the interviews — the role of special collections staff in curricula:Footnote43

If there are assignments set, I’m not marking the assignments. So I’m not really seeing the level of intellectual engagement with the objects and how that differs. (P1)

The stage at which undergraduates visited special collections varied. Two interviewees said they saw undergraduates at every stage of their studies; one noted it tended to be students in the latter stages of their degree. All participants thought undergraduate special collections use was hugely beneficial to student experience. Two interviewees discussed how using historic material reaffirms undergraduates’ decision to study at that institution (P3, P4). Four participants mentioned how undergraduate special collections sessions prepared students for future research and increased their confidence — especially in humanities disciplines:

It gives them an opportunity to start constructing their own versions of history using the evidence that’s there, rather than relying on other people’s. So it’s kind of that point where they become the historian rather than a student of history. (P2)

Examining special collections material helped students think independently, and the neutrality of special collections spaces was seen as a huge benefit, allowing students to make interdisciplinary connections in ways that taught modules can lack. Other participants believed that undergraduate special collections sessions inspired awareness of archives that students carried beyond academia:

We want the best people coming into our profession and we’ve got them … sitting on our doorstep as students. (P3)

The major barrier to undergraduates using special collections discussed in interviews mirrored the questionnaire respondents: lack of awareness and comprehension. Interviewees believed the difficulty of finding out what material is held in special collections largely relates to challenges of using online resources (finding aids and websites).

Another barrier to undergraduate use of special collections given by four interviewees related to physical challenges around accessing the department. Many participants regarded this as an institutional barrier but the frequency of discussion places it as a wider issue. Two interviewees discussed special collections’ remoteness within the library; many undergraduates did not encounter the department during everyday use of the building and thus believed it to be an exclusive area. Four participants reflected on how the rules and regulations of special collections, being different from the rest of the library, made students feel uneasy about accessing material:

The [special collections] space is so controlled and you can’t explore it without a direct interaction with someone. (P2)

General awareness of special collections by undergraduates was a barrier for interviewees, with ‘the old favourite … of communication’ discussed frequently (P3). Awareness was viewed as problematic within the library and wider institution, as both contributed to students not realizing special collections are part of resources at their disposal (P4). The changing nature of undergraduate education led to many participants discussing time pressures on students, which in turn left little time for undergraduates to explore resources that didn’t directly impact on assignments (P5). However, interviewees considered how active learning methodology offered to undergraduates via special collections is due to a new generation of emerging academics keen to use contemporary pedagogy, which may in turn positively impact how students engage with material.

When discussing local barriers to undergraduates using special collections, interviewees identified institutional resources as a major concern. Two participants discussed a lack of time or space negatively impacting on the amount of special collections sessions they could offer undergraduates:

I think we’ve sometimes had up to 20 students at a time in, but say you’ve got … 150 students, sometimes you’re talking about offering, you know, 7 or 8 slots. It’s just not really viable. (P1)

We are finding it very difficult to offer the sessions that we want to in the space that we have – in fact, it’s impossible. (P2)

However, institutional resources also impacted relationships between professional services staff and academics. Wider pressures in universities were noted to directly affect early-career staff:

If you go to [academics] and try and sell [special collections sessions] to them they might be interested, they might be keen, they might be enthusiastic; they probably still won’t do anything about it because they’re maybe in the middle of a grant application … they’re writing up their monograph from their PhD … they’re even busier than we are – and we are really busy! (P1)

Interviewees believed that undergraduates’ expectations for all material to be available online contributed to access barriers for special collections. However, online access was also discussed by participants as a solution to many of the barriers encountered by students accessing special collections. Three participants referred to digital projects they were currently working on — in collaboration either with academic departments or within professional services. Three participants discussed the increasing role of work placements in undergraduate experiences, allowing students to understand more about special collections whilst developing valuable employability skills.

Discussion

Special collections support of undergraduates

As can be seen in above the numeric range of special collections education sessions offered varied significantly. The median number of sessions for all students (22) was slightly higher than the median number of sessions for undergraduates (13), evidencing strong support for undergraduate teaching in special collections. However, the range of responses for both questions spanned from zero to 166. This may be due to how institutions record visit data and how they count repeated sessions for the same course (for example, due to limited space in teaching rooms). The reasons for this wide range merit further investigation beyond the scope of this article and evidence a need for the profession to centrally collate engagement data.Footnote44 Arts and Humanities subjects continued to comprise most undergraduate visits to special collections, with 247/313 (79%) of students attending sessions being from these disciplines according to questionnaire respondents. This finding supports literature evidence that there is a gap between special collections involvement in Humanities education and special collections’ role in science and social science disciplines.Footnote45 Lack of engagement may be more complex than special collections simply having more relevant Arts collections; preferences of academics and students affect special collections use across all disciplines. In some cases, special collections may have relevant material but curriculum and collection development is hampered by lack of staff time to adequately research these collections.

Figure 1. Total number of special collections education sessions offered in 2018/2019 for all students.

Figure 2. Total number of special collections education sessions offered in 2018/2019 for undergraduate students.

Figure 3. Total number of special collections education sessions offered in 2018/2019 for undergraduate students vs all students.

Interestingly, the literature does not fully address this collections development gap, focusing instead on successful special collections subject collaborations.Footnote46 These interviews were able to evidence the value of working with subject schools and departments to enhance the relevance of special collections material. Other methods of broadening the subject reach of special collections include hiring student interns to research underused collections and mapping special collections material to current teaching.

The literature review, questionnaires, and interviews all highlight how undergraduate education sessions in special collections support individual course or subject learning rather than show and tell methods of engagement. Interviewees discussed how all undergraduate sessions are organized to support specific courses rather than promoting collections generally. However, only 32% of questionnaire respondents offered multiple sessions to academics over a single module, which contrasts with the literature’s assessment that a single session is not enough to teach undergraduates about special collections.Footnote47 It is likely that barriers to student use of special collections impact staff ability to offer multiple sessions over a semester in conjunction with other educational commitments. What this then creates, as discussed by Zhou, is that a single session must be incredibly well structured in order to give students a clear understanding of ‘archival intelligence’ and build their confidence enough to return.Footnote48

Pedagogy is therefore key in structuring undergraduate special collections sessions effectively; this is evidenced by the large volume of US research exploring special collections literacy. Special collections literacy may help academics and special collections staff in designing classes to meet both course goals and practical skill building and provide ground to establish discipline-wide skills which currently do not possess a unified framework for undergraduate progression.Footnote49 The ACRL-RBMS-SAA guidelines do not specify levels or expectations of special collections literacy at any learning stage, but it is clear from the interviews that staff are already adapting educational activities to student stages.

What is less clear from the literature, interviews, and questionnaire responses is how undergraduate special collections sessions are assessed. The meaning of the term assessment in relation to special collections teaching is unclear amongst UK university special collections staff; the most common method of reviewing undergraduate sessions, according to questionnaire responses, was to gather informal feedback in class via group discussions at the end of the session or by asking staff and students for thoughts about the class afterwards. The literature proposes that using a pre-test/post-test method before and after a special collections class may be the most effective way of evaluating impact, but this has yet to be carried out in a UK context.Footnote50

The literature, questionnaire responses, and interviews all agree that it is hugely beneficial for undergraduates to engage with special collections. Benefits for students beyond developing skills include using material for creative inspiration and having physical contact with the past, which is increasingly novel in our digital age.Footnote51

The desire for academics to create memorable learning experiences for their students may be due in part to the impact of university success metrics such as the TEF, introduced in 2017.Footnote52 It could additionally reflect an increasingly diverse student body with varied learning styles and needs.Footnote53 Since the COVID-19 pandemic, special collections have begun to offer virtual and hybrid teaching sessions, which the literature is beginning to evaluate.Footnote54

More recently, there has been increased work in the UK around actively developing special collections academic partnerships.Footnote55 This reflects changes in libraries around increasing departmental collaboration; special collections must capitalize on this to ensure academic librarians are confident in promoting special collections and education to the wider university.Footnote56 Interviewees discussed the role institutional and departmental strategy has in focusing university resources to support special collections teaching.

Special collections skills developed by undergraduate students

For interviewees and questionnaire respondents, the greatest benefit undergraduates using special collections can gain is awareness the department exists and the role it can have in their education. This was discussed by 50% of survey participants and all interviewees, who believed making undergraduates aware of university resources at an early stage has a direct impact on academic progress. It was also seen as crucial to build awareness in undergraduates before they decide on research topics.

Interestingly, existing literature does not explicitly discuss raising awareness of special collections using the same language as this paper: there are examples of effective outreach to undergraduates and positive feedback from students following special collections education but little about the impact promoting special collections can have.Footnote57 The impact of awareness is absent from the ACRL-RBMS-SAA primary source guidelines, although discussed as part of Yakel and Torres’ archival intelligence concept.Footnote58

By using special collections, undergraduates gain increased understanding in many areas; this is evidenced in the literature, questionnaire responses, and interviews. Sixty-seven per cent of survey participants believed special collections help undergraduates comprehend what primary sources are and how they differ from secondary sources. Four out of five interviewees expanded upon this, discussing the role such comprehension has on their education and subject area. This contrasts with the theory developed by Duff, Monks-Leeson and Galey, who posit that contextual subject knowledge is key to understanding special collections material; for undergraduates, engaging with special collections can increase understanding of how their own subject is constructed.Footnote59 Giving students assignments based on special collections can also mirror graduate- and faculty-level research, modelling academic work.Footnote60 Once students have attended a special collections session, they begin to understand the terminology, processes and procedures that initially seem intimidating. This was supported by 48% of questionnaire participants and all interviewees.

Many skills gained by undergraduates through using special collections are seen by questionnaire respondents and interviewees to be transferable to both other study areas and in post-university life. The literature highlights how skills such as information evaluation, critical thinking, and independent research are vital attributes in modern society.Footnote61 Interviewees expanded upon this, discussing how it is therefore important that special collections have effective methods of communicating their impact. The recent Research Libraries UK report Evidencing the Impact and Value of Special Collections discusses multiple ways that special collections can demonstrate and communicate their impact both within universities and their wider communities.Footnote62 However, the report does not discuss evidencing teaching value in depth; special collections should use this report to build their own case studies around undergraduate education.

Another aspect of employability, only recently discussed in the literature but highlighted by interviewees and questionnaire respondents, is the benefit that undergraduate work placements and internships bring to both special collections and students.Footnote63 Three out of five interviewees mentioned the increasing demand for undergraduate internships in their department. Internships, as discussed by participants, tend to be either built into a course or funded employment for a fixed period. This is perhaps caused by increasing graduate employer demand for vocational skills to be incorporated into Humanities degrees.Footnote64

Barriers to undergraduates using special collections

For questionnaire respondents, undergraduates’ lack of awareness of special collections — their existence and their role in education — is the biggest barrier students face, discussed by 73% of participants. As noted by Clough, the literature does not widely examine this barrier, instead noting how undergraduates primarily face confidence and terminology issues which deter them from using special collections.Footnote65 However, issues stemming from lack of awareness affect all other barriers discussed.

There is a distinct lack of discussion amongst the literature, questionnaire respondents and interviewees about the role university marketing teams have in promoting special collections — perhaps because public discussion of internal liaison can be a sensitive issue. Potter explores how libraries can best market their facilities within universities, and notes that there should be a focus on promoting services and their benefits rather than products.Footnote66 Although special collections by their unique and distinctive nature tend to highlight collection stories over effect of use, this study suggests that undergraduates need to be able to make direct connections between information services and the benefits they have on their degrees.

Confidence issues are seen as a major barrier to undergraduate special collections use by the literature, questionnaire respondents, and interviewees. Forty-five per cent of survey participants believed that undergraduates lacked certainty about special collections; this issue is related to environmental barriers, such as physical location of the service in the library and departmental rules and regulations, and access barriers such as limited opening hours and the need to make advance appointments.

Some of this fear is linked to the traditional purpose of special collections in preserving material; many departments have been built separately from the rest of the library for both conservation purposes and to impress upon potential donors the institutional impact their contribution will have.Footnote67 Because these building barriers cannot easily be alleviated, it therefore falls to special collections staff to help students overcome these fears and access collections.Footnote68 It is interesting that only 18% of questionnaire respondents said they offered a pop-up special collections service in campus areas beyond the library, which would help alleviate some of the environmental barriers impacting student confidence when using special collections. This could be due to the strong feeling amongst interviewees and questionnaire participants that undergraduates value physical contact with historical material, which cannot easily be replicated in other areas.

For questionnaire respondents and interviewees, undergraduates were seen to have increasing pressures on their time which negatively impacted on their ability to invest in resources that may not appear directly related to their degree. This again supports the need for more effective marketing of special collections but also explains why so many students use online resources: they are more convenient to access compared to special collections material. Here it is worth exploring literature examining information behaviour: the four characteristics of undergraduate research activity outlined by D’Couto and Rosenhan can be directly applied to a perceived lack of engagement with special collections.Footnote69

Because academics are vital to link undergraduates with special collections resources, it is crucial to consider why lecturers may not use local special collections. As noted by P3, early-career academics are now using resources in very similar ways to today’s undergraduates, so many of these barriers also apply to university staff. The research published by Tanaka et al. offers clear insights into why this may be and suggests strategies for special collections departments to consider in future, including more targeted approaches to working with faculty and considering the impact of ‘disciplinary traditions’ with primary source use.Footnote70 This research is something the author will take forward in her own practice, leading special collections teaching at University College London’s new East campus which has a clear interdisciplinary focus.Footnote71

Digital resources have a huge role in undergraduate education and this in turn impacts student use of special collections, as discussed by 38% of questionnaire respondents. Special collections materials are often surfaced using different discovery interfaces than other library material, which instantly makes it harder for students to find. Four out of five interviewees discussed the need to improve online content and three out of five were actively working on projects to increase digital visibility. Tanaka et al. suggest multiple ways to approach these concerns (which may have arisen after the interviews for this paper were undertaken): aligning digitization priorities with instructors’ teaching needs is one solution.Footnote72 Similarly, special collections staff could curate themed sets of digitized resources from their own collections to help tutors find relevant material more quickly.Footnote73 These suggestions are supported by Grafe, who notes that digital primary sources play an increasingly important part of special collections education since the pandemic, and it is the job of special collections professionals to find innovative ways to engage with digital content and pedagogy.Footnote74

Online digital interface issues are once again impacted by undergraduate confidence in approaching special collections staff; navigating archival hierarchies often requires face-to-face training, which many students are reluctant to undertake.Footnote75 Solutions to this include creating guides outlining initial search strategies and creating videos.Footnote76

The results clearly show that there is an urgent need to embed special collections teaching at a departmental level rather than relying on individual tutors. As noted by P1, changes in universities have a direct impact on special collections teaching; there is less job stability in academia than in previous generations, and as many special collections sessions are supported by early-career lecturers this means that time spent on cultivating special collections course inclusion may not have a long-term curricular impact. The literature does not fully address this issue. Cullingford discusses involving departmental administrative staff in arranging special collections sessions, which possibly alludes to the problem.Footnote77

A final barrier discussed by the literature, questionnaire respondents, and interviewees is the limited staffing of special collections. Many questionnaire participants noted that they were the only member of staff responsible for collections, and interviewees noted that this lack of resourcing affects their ability to work on longer term engagement projects (P3, P5). Interviewees also discussed the lack of physical space in the department for extra staff or additional teaching sessions, which has long been noted in the literature but is becoming increasingly important as student numbers rise and demand for special collections education sessions increase.Footnote78

The literature frequently references the time-intensive nature of special collections education sessions, which involve liaison with academics, pedagogical session design, administrative work, and selecting and retrieving material before the session itself.Footnote79 Special collections literacy frameworks may help support academic network building and session design.Footnote80 Interviewees also discussed the role of digital resources in alleviating limited special collections staff resources; by digitizing material it may be possible to design online courses and support academics can use independently, which special collections staff can use in a larger space elsewhere on campus.

Conclusion

This project’s findings and subsequent discussion successfully met the objectives of the study, by establishing a picture of current UK special collections education for undergraduates and examining the skills and barriers faced by students accessing material. For undergraduates, special collections education sessions are vital to raise awareness of institutional resources and to break down physical and intellectual access barriers to departments, which are frequently exacerbated by the convenience and accessibility of digital resources. A gap in the findings relating to promotion of special collections in universities was identified, and a need for extensive departmental embedding of special collections was highlighted to resolve long-term issues of informal academic networking and pressured special collections resources. Solutions to barriers were suggested, with improved digital resources and the role of undergraduate work placements being the most common.

The questionnaire and interview responses both suffer from a lack of consistent terminology within both the special collections and university world; this is particularly notable in the varied range of responses to numbers of special collections visits in the questionnaire. Another implicit problem, highlighted by the findings, is a lack of UK benchmarking for special collections: again, the range of responses to special collections group numbers in calendar years demonstrates a lack of consistency that could be used to evidence impact.

This paper has established a clear picture of special collections education activity for UK university undergraduates. The questionnaire responses and interviews highlight the breadth of sessions being undertaken and the clear benefits for students, educators and special collections staff. It has highlighted the challenges faced by students including lack of awareness, difficulties in staffing sessions and inconsistent terminology in the field. However, the research also posited many solutions to these challenges including more strategic digitization of resources, working across library and museum studies to share solutions and experiences, and the growing importance of interdisciplinary collaboration to highlight special collections literacy.

This paper has highlighted several areas for future research, including the impact of special collections marketing within universities, embedding special collections into academic departmental curricula, information behaviour of undergraduates in relation to special collections digital resources, the value of special collections work placements, and the relationship between special collections and their university library. It would also be useful to repeat this study again including academics and students in the methodology. The differences between Oxbridge and other universities should be explored and subsequent findings incorporated into UK research. The North American focus of much of the literature demonstrates that the UK needs to invest more time in exploring the educational impact of special collections; subsequent projects could focus on a variety of aspects including differences in information literacy and special collections literacy, the impact of undergraduate skills development, engagement with social science and science disciplines, and evaluating special collections literacy with students over a sustained period. The passion special collections enact in staff, academics and students is clear from this research; future projects will do well to create standards and pedagogy across institutions and disciplines.

Acknowledgments

This research was undertaken by the author in partial fulfilment of the University of Aberystwyth’s requirements for the MA in Information and Library Studies, 2019. The research was supported by and pilot-tested by colleagues at the University of Kent in 2019. The author is profoundly grateful for support from both institutions, in particular Julie Mathias and Karen Brayshaw.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Joanna Baines

Joanna Baines is the Academic Liaison Librarian / Archivist for University College London (UCL) Special Collections. She is responsible for delivering the Special Collections academic teaching programme at UCL’s new East campus in Stratford, London, due to open in September 2022. Prior to joining UCL in February 2022, Joanna worked for Special Collections & Archives at the University of Kent, Canterbury for six years leading their education programme. She has an extensive background in Special Collections user engagement, frontline service delivery and collections management.

Notes

2. ACRL-RBMS-SAA Joint Task Force on the Development of Guidelines for Primary Source Literacy, 2018.

3. See the Journal of Information Literacy and CILIP’s extensive guidelines on Information Literacy (https://archive.cilip.org.uk/research/topics/information-literacy).

4. The (UK) National Archives, “Postgraduate Archival Skills Training.”

5. RLUK, “Unique and Distinctive Collections,” 6.

6. Mitchell, Seiden, and Taraba, Past or Portal?

7. Yakel and Torres, “AI”; Mitchell, Seiden, and Taraba, Past or Portal?

8. RLUK, “Unique and Distinctive Collections,” 15; and Pinfield, Cox and Rutter, 21.

9. Vassilakaki and Moniarou-Papaconstantinou, “Beyond Preservation,” 114–6.

10. Malkmus, “Pulling on the White Gloves Is Really Sort of Magic,” 126–7; Houlihan, “Children’s Studies;” Baer, “Librarians’ Development as Teachers,” 43.

11. Tanaka et al., “Teaching with Primary Sources.”

12. Garcia, Lueck and Yakel, “The Pedagogical Promise of Primary Sources,” 95.

13. Appleton, Grandal Montero and Jones, ”Creative Approaches,” 163; Cullingford, The Special Collections Handbook, 199.

14. Mitchell, Seiden and Taraba, Past or Portal?; Webb, ”The Virtuous Circle.”

15. Houlihan, “Children’s Studies.”

16. RLUK, “Unique and Distinctive Collections,” 15.

17. Bury, “Learning from Faculty Voices.”

18. Mitchell, Seiden and Taraba, Past or Portal?; Weiner, Morris and Mykytiuk, ”Archival Literacy Competencies,” 398; Thiemer, 2015.

19. Alison, Research Methods in Information, 2005.

20. Brown, Information Literacy; Clough, Undergraduate Use of University Archives.

21. Watson and Pattrick, “Teaching Archive Skills.”

22. Appleton, Grandal Montero and Jones, ”Creative Approaches to Information Literacy,” 153.

23. Weiner, Morris and Mykytiuk, ”Archival Literacy Competencies,” 157.

24. Duff and Cherry, ”Archival Orientation,” 508.

25. Krause, “It Makes History Alive for Them,” 407; Mazella and Grob, ”Collaborations between Faculty,” 472; Cullingford, The Special Collections Handbook, 199.

26. Duff and Cherry, ”Archival Orientation,” 521.

27. Samuelson and Coker, ”Mind the Gap,” 59.

28. Mazella and Grob, ”Collaborations between Faculty,” 474; Weiner, Morris and Mykytiuk, ”Archival Literacy Competencies,” 410.

29. Hauck and Robertson, ”Of Primary Importance,” 225–6.

30. Daniels and Yakel, ”Uncovering Impact,” 419; Carini, ”Information Literacy,” 193.

31. Bahde, ”The History Labs,” 182; Cobley, “Why Objects Matter,” 87.

32. Matheny, “No Mere Culinary Curiosities.”

33. Zhou, “Student Archival Research Activity,” 478.

34. Malkmus, ”Pulling on the White Gloves,” 128.

35. Flynn and Birrell, “Fostering Graduate Student Research.”

36. D’Couto and Rosenhan, “How Students Research,” 565.

37. Baseby, “Researching Researchers,” 192.

38. Aurini, Heath and Howells, The How to of Qualitative Research, 64.

39. Pickard, “Research Methods in Information,” 210–23.

40. The Complete University Guide, “UK University Profiles.”

41. Pickard, “Research Methods in Information,” 64.

42. ACRL-RBMS-SAA Joint Task Force, “Guidelines for Primary Source Literacy.”

43. Rockenbach, “Archives, Undergraduates, and Inquiry-Based Learning,” 298.

44. See SCONUL, “SCONUL Statistics Reports” for details of annual university library return data reported. The Archives & Records Association, “Resources” publishes results of its annual visitor survey and CIPFA, “Archives” also offers visitor survey services for archive collections. Many thanks to Beth Astridge for sharing this information.

45. Brown, Losoff and Hollis, Information Literacy, 202.

46. Clough, “Undergraduate Use of University Archives,” 69.

47. See note 24 above, 521.

48. Zhou, “Student Archival Research Activity;” Yakel and Torres, ”AI,” 51.

49. See note 23 above, 155.

50. Krause, “It Makes History Alive,” 513; Kumar, Research Methodology, 136–7.

51. Appleton, Grandal Montero, and Jones, “Creative Approaches to Information Literacy,” 163.

52. Pinfield, Cox and Rutter, “Mapping the Future of Academic Libraries,” 21.

53. Torre, “Why Should Not They Benefit,” 40.

54. Kamposiori, “Virtual Reading Rooms.” University College London, “Teaching Resources” highlights resources available for teaching in hybrid environments. RBM: A Journal of Manuscripts, Rare Books and Cultural Heritage Vol 22. No. 1 (2021) contains many articles directly exploring the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on special collections departments.

55. The (UK) National Archives, “A Guide to Collaboration.”

56. Malkmus, “Pulling on the White Gloves,” 414; Pinfield, Cox and Rutter, “Mapping the Future of Academic Libraries,” 20; Vassilakaki and Moniarou-Papaconstantinou, “Beyond Preservation,” 121.

57. Hammerman et al., “College Students, Cookies and Collections;” Zhou, “Student Archival Research Activity.”

58. ACRL-RBMS-SAA Joint Task Force, “Guidelines for Primary Source Literacy;” Yakel and Torres, “AI”.

59. Duff, Monks-Leeson and Galey, “Contexts Built and Found.”

60. See note 32 above.

61. Robyns, “The Archivist as Educator,” 363; McCoy, “The Manuscript as Question,” 60; Carini, “Information Literacy,” 194.

62. Kamposiori and Crossley, “Evidencing the Impact and Value of Special Collections.”

63. Kopp and Murphy, “Mentored Learning in Special Collections.”

64. Howard, “Looking to the Future,” 74; Mays, “Using ACRL’s Framework,” 354–5.

65. Clough, “Undergraduate Use of University Archives,” 69.

66. Potter, “The Library Marketing Toolkit,” 2–3.

67. Torre, “Why Should Not They Benefit,” 37.

68. Johnson, “Introducing Undergraduate Students to Archives,” 97.

69. D’Couto and Rosenhan, “How Students Research.”

70. Tanaka et al., “Teaching with Primary Sources,“ 49.

71. University College London, “UCL East Schools and Faculties.”

72. See note 70 above, 48.

73. Ibid, 49.

74. Grafe, “Treating the Digital Disease.”

75. See note 37 above, 192.

76. Ibid.

77. Cullingford, The Special Collections Handbook, 199.

78. Allison, “Connecting Undergraduates with Primary Sources,” 50; University College London, “UCL Annual Review.”

79. Alvarez, “Introducing Rare Books,” 95; Tomberlin and Turi, “Supporting Student Work,” 307; Bahde, The History Labs, 176–7; Cullingford, The Special Collections Handbook, 199.

80. Bury, “Learning from Faculty Voices,” Carini, “Information Literacy.”

Bibliography

- ACRL-RBMS-SAA Joint Task Force on the Development of Guidelines for Primary Source Literacy. Guidelines for Primary Source Literacy. 2018. Available at: https://www2.archivists.org/sites/all/files/Guidelines%20for%20Primary%20Souce%20Literacy%20-%20FinalVersion%20-%20Summer2017_0.pdf. (Accessed: 26 April 2022.)

- Allison, A. E. “Connecting Undergraduates with Primary Sources: A Study of Undergraduate Instruction in Archives, Manuscripts, and Special Collections.” Master’s thesis, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, USA, 2005. Available at: https://cdr.lib.unc.edu/record?id=uuid:cc3864a9-10e4-467e-8b56-8171e400ab7b. (Accessed 01 April 2019).

- Alvarez, Pablo. “Introducing Rare Books into the Undergraduate Curriculum.” RBM: A Journal of Rare Books, Manuscripts, and Cultural Heritage 7, no. 2 (2006): 94–104. doi:10.5860/rbm.7.2.263.

- Appleton, Leo, Gustavo Grandal Montero, and Abigail Jones. “Creative Approaches to Information Literacy for Creative Arts Students.” Communications in Information Literacy 11, no. 1 (2017): 147-167. doi:10.15760/comminfolit.2017.11.1.39.

- Archives & Records Association. “Resources: Sector Surveys & Reports.” Available at:https://www.archives.org.uk/resources. Accessed: 07 July 2022.

- Aurini, Janice, Melanie Heath, and Stephanie Howells. The How to of Qualitative Research. Los Angeles: SAGE, 2016.

- Baer, Andrea. “Librarians’ Development as Teachers.” Journal of Information Literacy, 15, no. 1 (2021): 26-53. doi:10.11645/15.1.2846.

- Bahde, Anne. “The History Labs: Integrating Primary Source Literacy Skills into a History Survey Course.” Journal of Archival Organization 11, no. 3–4 (2013): 175–204. doi:10.1080/15332748.2013.951254.

- Baseby, Francesca. “Researching Researchers: Meeting Changing Researcher Needs in a Special Collections Environment.” New Review of Academic Librarianship, 23, no. 2-3 (2017): 185–194. doi:10.1080/13614533.2017.1322991.

- Brown, Amanda H., Barbara Losoff, and Deborah R. Hollis. “Science Instruction through the Visual Arts in Special Collections.” portal: Libraries and the Academy 14, no. 2 (2014): 197–216. doi:10.1353/pla.2014.0002.

- Brown, Emily. Information Literacy in Special Collections Departments: An Investigation into the Role of Specialised Information Skills Training. Aberystwyth: University of Aberystwyth, 2012.

- Bury, Sophie. “Learning from Faculty Voices on Information Literacy: Opportunities and Challenges for Undergraduate Information Literacy Education.” Reference Services Review 44, no. 3 (2016): 237–252. doi:10.1108/RSR-11-2015-0047

- Carini, Peter. “Information Literacy for Archives and Special Collections: Defining Outcomes.” portal: Libraries and the Academy 16, no. 1 (2016): 191–206. doi:10.1353/pla.2016.0006.

- CIPFA “Archives: Visitors’ Survey.” (2022). Available at: https://www.cipfa.org/services/research/archives. Accessed: 07 July 2022.

- Clough, Louise. Undergraduate Use of University Archives and Special Collections: Motivations, Barriers and Best Practice. Aberystwyth: University of Aberystwyth, 2015.

- Cobley, Joanna. “Why Objects Matter in Higher Education.” College and Research Libraries 83, no. 1 (2022): 75-90. doi:10.5860/crl.83.1.75.

- Complete University Guide. “UK University Profiles.” Accessed April 26, 2022. https://www.thecompleteuniversityguide.co.uk/universities.

- Cullingford, Alison. The Special Collections Handbook. Second ed. London: Facet Publishing, 2016.

- Daniels, Morgan, and Elizabeth Yakel. “Uncovering Impact: The Influence of Archives on Student Learning.” The Journal of Academic Librarianship 39, no. 5 (2013): 414–422. doi:10.1016/j.acalib.2013.03.017.

- D’Couto Michelle, and Serena H. Rosenhan. “How Students Research: Implications for the Library and Faculty.” Journal of Library Administration 55, no. 7 (2015): 562-576.

- Duff, Wendy M., and Joan M. Cherry. “Archival Orientation for Undergraduate Students: An Exploratory Study of Impact.” The American Archivist 71, no. 2 (2008): 499–529. doi:10.17723/aarc.71.2.p6lt385r7556743h.

- Duff, Wendy M., Emily Monks-Leeson, and Alan Galey. “Contexts Built and Found: A Pilot Study on the Process of Archival Meaning-Making.” Archival Science 12, no. 1 (2012): 69–92.

- Flynn, Kara, and Lori Birrell. “Fostering Graduate Student Research: Launching a Speaker Series.” RBM: A Journal of Rare Books, Manuscripts, and Cultural Heritage 22, no. 2 (2021): 71-84. doi:10.5860/rbm.22.2.71.

- Garcia, Patricia, Joseph Lueck, and Elizabeth Yakel. “The Pedagogical Promise of Primary Sources: Research Trends, Persistent Gaps, and New Directions.” The Journal of Academic Librarianship 45, no. 2 March (2019): 94–101. doi:10.1016/j.acalib.2019.01.004.

- Gordon Daines, J., and Cory L. Nimer. “In Search of Primary Source Literacy: Opportunities and Challenges.” RBM: A Journal of Rare Books, Manuscripts, and Cultural Heritage 16, no. 1 (March 1 2015): 19–34. doi:10.5860/rbm.16.1.433.

- Grafe, Melissa. “Treating the Digital Disease: The Role of Digital and Physical Primary Sources in Undergraduate Teaching.” RBM: A Journal of Rare Books, Manuscripts, and Cultural Heritage 22, no. 1 (2021): 25-32.

- Hammerman, Summerfield, Barbara Kern Susan, Rebecca Starkey, and Anne Taylor. “College Students, Cookies and Collections: Using Holiday Study Breaks to Encourage Undergraduate Research in Special Collections.” Collection Building 25, no. 4 October 1 (2006): 145–149.

- Hauck, Janet, and Marc Robinson. “Of Primary Importance: Applying the New Literacy Guidelines.” Reference Services Review 46, no. 2 (2018): 217–241.

- Houlihan, Barry. “Children’s Studies, Archives Literacy, and Cultural Contexts: Designing Teaching for Academic Library Learning.” New Review of Academic Librarianship 25, nos. 2-4 (2019): 315–334.

- Howard, Helen. “Looking to the Future: Developing an Academic Skills Strategy to Ensure Information Literacy Survives in a Changing Higher Education World.” Journal of Information Literacy 6, no. 1 (2012): 72-81.

- Information Literacy Group. “Definitions & Models.” Accessed April 26, 2022. https://infolit.org.uk/definitions-models/.

- International Federation of Library Associations and Institutions. “Beacons of the Information Society: The Alexandria Proclamation on Information Literacy and Lifelong Learning – IFLA.” Accessed April 26, 2022. https://www.ifla.org/publications/beacons-of-the-information-society-the-alexandria-proclamation-on-information-literacy-and-lifelong-learning/.

- Johnson, Greg. “Introducing Undergraduate Students to Archives and Special Collections.” College & Undergraduate Libraries 13, no. 2 (2006): 91-100.

- Kamposiori, C. Virtual Reading Rooms and Virtual Teaching Spaces in Collection Holding Institutions: An RLUK Report on Current and Future Developments. Research Libraries UK, 2022. Available at: https://www.rluk.ac.uk/portfolio-items/virtual-reading-rooms-and-virtual-teaching-spaces-in-collection-holding-institutions/. (Accessed: 06 July 2022)

- Kamposiori, Christina, and Sue Crossley. “Evidencing the Impact and Value of Special Collections.” Research Libraries UK (blog). Accessed April 26, 2022. https://www.rluk.ac.uk/portfolio-items/evidencing-the-impact-and-value-of-special-collections/.

- Kopp, M.G., and J.M. Murphy. “Mentored Learning in Special Collections: Undergraduate Archival and Rare Books Internships.” Journal of Library Innovation 3, no. 2 (2012): 50–62.

- Krause, Magia G. “‘It Makes History Alive for Them’: The Role of Archivists and Special Collections Librarians in Instructing Undergraduates.” The Journal of Academic Librarianship 36, no. 5 (September, 2010): 401–411.

- Kumar, Ranjit. Research Methodology: A Step-by-Step Guide for Beginners. Fourth ed. Los Angeles: Sage, 2014.

- MacDonald, Gus. “What Is Information Literacy?” CILIP: The Library and Information Association. Accessed April 26, 2022. https://www.cilip.org.uk/news/421972/What-is-information-literacy.htm.

- Malkmus, Doris. “‘Old Stuff’ for New Teaching Methods: Outreach to History Faculty Teaching with Primary Sources.” portal: Libraries and the Academy 10, no. 4 (2010): 413–435.

- Malkmus, D. “‘Pulling on the White Gloves Is Really Sort of Magic’: Report on Engaging History Undergraduates with Primary Sources Teaching Research and Learning Skills with Primary Sources: Three Modules.” In Past or Portal? Enhancing Undergraduate Learning through Special Collections and Archives, edited by E. Mitchell, P. Seiden, and S. Taraba, 125–132. Chicago: Association of College and Research Libraries, a division of the American Library Association, 2012.

- Matheny, Kathryn. “No Mere Culinary Curiosities: Using Historical Cookbooks in the Library Classroom.” RBM: A Journal of Rare Books, Manuscripts, and Cultural Heritage 21, no. 2 (2020): 79-97.

- Mays, Dorothy A. “Using ACRL’s Framework to Support the Evolving Needs of Today’s College Students.” College & Undergraduate Libraries 23, no. 4 (October, 2016): 353–362.

- Mazella, D., and J. Grob. “Collaborations between Faculty and Special Collections Librarians in Inquiry-Driven Classes.” Libraries and the Academy 11, no. 1 (2011): 467–487.

- McCoy, Michelle. “The Manuscript as Question: Teaching Primary Sources in the Archives—The China Missions Project.” College and Research Libraries 71, no. 1 (2010): 49-62.

- Mitchell, Eleanor, Peggy Seiden, and Suzy Taraba, eds. Past or Portal? Enhancing Undergraduate Learning through Special Collections and Archives. Chicago: Association of College and Research Libraries, a division of the American Library Association, 2012.

- Museum of English Rural Life, The MERL and Special Collections Review 2020-2021. University of Reading: 2021. Available at: https://collections.reading.ac.uk/special-collections/wp-content/uploads/sites/5/2021/09/The-MERL-and-Special-Collections-Review-2020-21.pdf. (Accessed: 06 July 2022).

- National Archives, The (UK). “The Postgraduate Archival Skills Training” (2018). Accessed April 26, 2022. https://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/ukgwa/20210308233327/https://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/about/our-research-and-academic-collaboration/events-and-training/postgraduate-archival-skills-training/

- National Archives, The (UK) and History UK. A Guide to Collaboration for Archives and Higher Education. 2018 edition. Available at: https://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/documents/archives/2018-edition-archive-and-he-guidance-all-sections-combined-ci-final.pdf. (Accessed: 26 April 2022)

- Pickard, Alison Jane. Research Methods in Information. 2nd ed London: Facet, 2013.

- Pinfield, S., A. Cox, and S. Rutter. Mapping the Future of Academic Libraries: A Report for SCONUL. SCONUL, 2017. Available at: https://www.sconul.ac.uk/sites/default/files/documents/Mapping%20the%20Future%20of%20Academic%20Libraries%20Final%20proof_0.pdf. (Accessed: 26 April 2022).

- Potter, Ned. The Library Marketing Toolkit. London: Facet Publishing, 2012.

- Quagliaroli, Jessica, and Pamela Casey. “Teaching with Drawings: Primary Source Instruction with Architecture Archives.” The American Archivist 84, no. 2 (2021): 374-396.

- Research Libraries UK. Unique and Distinctive Collections: Opportunities for Research Libraries. RLUK UDC, 2014. Available at: https://www.rluk.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/RLUK-UDC-Report.pdf. (Accessed: 26 April 2022).

- Robyns, Marcus. “The Archivist as Educator: Integrating Critical Thinking Skills into Historical Research Methods Instruction.” The American Archivist 64, no. 2 (2001): 363-384.

- Rockenbach, Barbara. “Archives, Undergraduates, and Inquiry-Based Learning: Case Studies from Yale University Library.” The American Archivist 74, no. 1 (2011): 297–311.

- Sammie, Morris, Lawrence J. Mykytiuk, and Sharon A. Weiner. “Archival Literacy for History Students: Identifying Faculty Expectations of Archival Research Skills.” The American Archivist 77, no. 2 (2014): 394–424.

- Samuelson, Todd, and Cait Coker. “Mind the Gap: Integrating Special Collections Teaching.” portal: Libraries and the Academy 14, no. 1 (2013): 51–66.

- SCONUL. “SCONUL Statistics Reports.” Available at: https://www.sconul.ac.uk/page/sconul-statistics-reports (Accessed: 06 July 2022)

- Tanaka, Kurtis, Daniel Abosso, Krystal Appiah, Katie Atkins, Peter Barr, Arantza Barrutia-Wood, Shatha Baydoun, et al. “Teaching with Primary Sources: Looking at the Support Needs of Instructors.” Ithaka S+R, March 23, 2021. doi:10.18665/sr.314912

- Tomberlin, Jason, and Matthew Turi. “Supporting Student Work: Some Thoughts About Special Collections Instruction.” Journal of Library Administration 52, no. 3–4 (April, 2012): 304–312.

- Torre, Meredith E. “Why Should Not They Benefit from Rare Books?: Special Collections and Shaping the Learning Experience in Higher Education.” Library Review 57, no. 1 (2008): 36-41.

- University College London. “Research and Teaching.” Library Services, May 14, 2019. Available at: https://www.ucl.ac.uk/library/collections/special-collections/research-and-teaching (Accessed: 06 July 2022)

- University College London. “Teaching Resources.” 2022. Available at: https://www.ucl.ac.uk/teaching-learning/teaching-resources. ( Accessed: 06 July 2022).

- University College London. “UCL Annual Review: Facts, Figures and Statistics.” 2022. Available at: https://www.ucl.ac.uk/annual-review/facts-figures-and-statistics. (Accessed: 07 July 2022).

- University College London. “UCL East Schools and Faculties.” 2022. Available at: https://www.ucl.ac.uk/ucl-east/schools-and-centres (Accessed: 24 April 2022).

- University College London. “’Word as Art’: Call for Slade Student Art Submissions.” 2021. Available at: https://blogs.ucl.ac.uk/special-collections/2021/04/30/call-for-art-2021/ (Accessed: 06 July 2022).

- University of Edinburgh. “Centre for Research Collections: Research Resources.” 2022. Available at: https://www.ed.ac.uk/information-services/library-museum-gallery/crc/research-resources. (Accessed: 06 July 2022).

- University of Glasgow. “Archives & Special Collections: Support for Teaching.” 2022. Available at: https://www.gla.ac.uk/myglasgow/archivespecialcollections/supportforteaching (Accessed 06 July 2022)

- University of Kent. “Special Collections & Archives: Engaging with our Collections: Education and Research.” 2022. Available at: https://www.kent.ac.uk/library-it/special-collections/visit-us/education. (Accessed: 06 July 2022).

- University of Reading. “Special Collections: Research and Learn: Resources for Students.” 2022. Available at: https://collections.reading.ac.uk/special-collections/research-learn/resources-for-students/. (Accessed: 06 July 2022).

- Vassilakaki, Evgenia, and Valentini Moniarou-Papaconstantinou. “Beyond Preservation: Investigating the Roles of Archivist.” Library Review 66, no. 3 (2017): 110-126.

- Watson, Karen, and Kirsty Pattrick. “Teaching Archive Skills: A Pedagogical Journey with Impact.” Archives and Records 41, no. 2 (2020): 170-186.

- Webb, Derek. “The Virtuous Circle of Student Research: Harnessing a Multicourse Collaborative Research Project to Enhance Archival Collections.” The American Archivist 82, no. 1 (March, 2019): 155–164.

- Weiner, S. A., S. Morris, and L. J. Mykytiuk. “Archival Literacy Competencies for Undergraduate History Majors.” The American Archivist 78, no. 1 (2015): 154–180.

- Yakel Elizabeth, and Deborah A. Torres. “AI: Archival Intelligence and User Expertise.” The American Archivist 66, no. 1 (2003): 51–78.

- Zhou, Xiaomu. “Student Archival Research Activity: An Exploratory Study.” The American Archivist 71, no. 2 (2008): 476–498.

Appendix A:

Questionnaire protocol

Undergraduate use of Special Collections & Archives

1. Project background and consent

This questionnaire is being issued as part of a dissertation project exploring undergraduate use of Special Collections & Archives.

Dear Participant, My name is Joanna Baines and I am currently studying for an MA in Information and Library studies at the University of Aberystwyth. As part of my course, I am undertaking a research project under the supervision of [supervisor name]. This project aims to explore undergraduate use of Special Collections and Archives departments; in particular, I am investigating the skills students can gain through using Special Collections and Archives material and the barriers to acquiring these skills. I am interested in the views of individuals (rather than institutions or departments) working with students in Special Collections & Archives, primarily in outreach and education roles. There may be multiple people in your institution that fit this criteria and if this is the case, everyone is very welcome to fill in this survey. I would be very grateful if you would take the time to complete my questionnaire. It will take approximately 10 minutes to complete. There are no right or wrong answers. There are three questions requiring statistics about group visits to your department, so it may be helpful to have these numbers to hand. If you choose to take part in this research please read the statements below:______