ABSTRACT

Cultural institutions have long employed a range of copying technologies to safeguard and improve access to archival materials. This paper moves discussion beyond debates about institutional copying focused on a specific technology and raises questions about the trustworthiness of copies of archival photographs. This study uses differences between a source photograph and four copies to show that copying practices shape how copies of archival photographs can be used. It is situated within the Australian legal context of native title to sharpen the interrogation of the trustworthiness of copies; and, to demonstrate one implication of how copying shapes the evidential value of photographs. It considers how a witness may respond if asked to testify that one or all of these copies are trustworthy or to outline their shortcomings as evidence. It explains that while standards for microfilm copying documents valued creating trustworthy copies, the transition to digital copying was a missed opportunity to re-establish those standards for creating digital surrogates of photographs. While questions raised have yet to be tested in legal native title procedures, this paper argues that the promise of photographs for native title outcomes will come to rest with the trustworthiness of institutionally created copies.

Even within the profession, photographs are still largely misunderstood in archival theory and mismanaged in archival practice. The challenges posed by content-driven descriptive practices, born-digital images, digitization, and online access continue to thwart a basic theoretical rethinking of photographs as archives as well as in archives.Footnote1

Practice of copying

Cultural institutions have long employed a range of copying technologies to safeguard and improve access to archival materials. Pre-digital copying technologies have regularly been discussed in the context of international co-operation and democratizing access to remote archival resources through the distribution of copies on microfilm.Footnote2 The introduction of digital technologies in the 1990s stimulated more critical debate about the benefits and shortcomings of new technologies, in particular for copying archival photographs. However, there has been a remarkable absence of discussion as to whether digital or photographic surrogates created by cultural institutions are in and of themselves authentic and trustworthy copies of their source photograph.

Early debates about the digitization process challenged its perceived neutrality and raised questions about the impact of digital copying on the material form and sources of meaning of photography, as well as the nature of the digital surrogate.Footnote3 In terms of the use value of digitization, discussion has shifted towards ways these mass image banks intersect with community needs for historical recognition, cultural ownership and healing, often in highly charged political or cultural contexts.Footnote4 In these contexts, digitized archival photographs have been used in, for example, mass activism, community building, and by First Nations and other displaced communities for the assertion of identity and connection to place.Footnote5

There are tempers to the promise of universal digital access, particularly in contexts of conflict and legacies of colonialism. These include the impact of institutional practices such as the power to privilege and marginalize, notions of access to colonial archives and ethics of care in relation to sensitive materials.Footnote6 Ethical issues concerning access to digital image banks are expressed in some international professional codesFootnote7 and discussed in relation to legal, cultural, political and affective contexts and the impact that the very mass of these digital image banks has on particular ways of seeing.Footnote8 Yet questions remain as to the trustworthiness of the digital copy itself and its relationship to the source photograph.

This paper moves discussion beyond the broader debates about copying photographs that have focused on a specific technology. Here, we raise questions about the trustworthiness of institutionally created copies of archival photographs. We draw out differences between multiple copies of a single photograph created over time by selected Australian institutions using two common copying technologies – photographic and digital. These differences then become a conduit through which to question whether copying practices per se of the last 40 years independent of the copying technology employed, have preserved the evidentiary values of photographs. In doing so, we reflect on whether it is the technology of copying or the ways those in institutions think about the format being copied – in this case photographs – that shapes the practices of copying.

We situate this discussion within the legal context of native title in Australia for two reasons: firstly, to sharpen the interrogation of the trustworthiness of copies of archival photographs created by cultural institutions; and secondly, to demonstrate one implication of how copying shapes the evidential value of photographs. We note parallels between legal and recordkeeping notions of evidence and acknowledge studies of the relationship between these two frameworks utilizing the concept of ‘warrant.’Footnote9 However, we enter the legal context with some caveats. We heed Meehan’s warning as to ‘the inherent dangers in using legal rules of evidence as an archival resource without being mindful of the nuances, particularities, and potential implications of the attendant concepts.’Footnote10 In addition, we note it was never the intention of the Australian and international recordkeeping standards to bring recordkeeping and legal frameworks together. This was due in part to international differences in the ’warrant’ and because of the desire to keep distinct the making and keeping of records as evidence of normal business activity, and the gathering and making of evidence acceptable in legal proceedings.Footnote11

Photographs in Native Title

There is a long history of photographs being used as evidence in the Anglo-American legal tradition.Footnote12 As we have argued elsewhere, there is common agreement across archival and photograph theory, forensic science and legal precedent ‘that photographs gain their evidentiary value from understanding what they are of in relation to their context of creation and the reasons they were originally created’Footnote13 Since the introduction of digital technologies, police and forensic science have been in the forefront of developing best practice to ensure that digital evidence can be relied upon by the courts.Footnote14

Photographs in themselves have considerable potential to be used as evidence in pursuit of social justice. In Australia, native title claims addressed by the Federal Court are where legal processes are conducted to establish recognition of pre-existing Indigenous rights and interests according to traditional laws and customs. While cultural change is generally recognized, Indigenous rights in land and waters must, according to the legislation, derive from a continuity of customary law. When building evidence to establish a claim to native title, photographs are most commonly used as illustration of people, places and objects in situ in expert reports that are then tendered in both mediation and if needed litigation proceedings. However, given the vast number of historical photographs of Indigenous people held in cultural institutions and private collections, it is perhaps surprising how seldom photographs reproduced as illustrations in expert reports have been noted in judgments for providing information of any specific significance to native title cases, or on how few occasions individual images or collections of photographs have, in themselves, been tendered as evidence.Footnote15

Photographs can potentially play an important role when tendered as evidence in the native title context. To ignore this source of photographic material would be, in our view, inconsistent with the high-quality research required as Australia seeks to address an important aspect of the legacies of colonialism. In a rare discussion on this topic, Aird, Sassoon and Trigger explain that when photographs are carefully researched and thoroughly contextualized, they are able to ‘present instructive data in what is a politically charged environment, and where there may be quite fragile Indigenous community memories of forebears and traditional country.’Footnote16 Photographs can prompt personal and cultural questions that may be answered by looking at images in relation to the oral and written record, and they may provide evidence of one or more forebears whose existence reaches back beyond claimants’ memories. Photographs can at times enable claimants and researchers to produce narratives about individuals’ possible relationships with ‘country.’ In the context of Indigenous Australia, the concept of ‘country’ encompasses the physical and spiritual characteristics of land and its species. In this paper, we wish to extend the discussion about the evidentiary value of photographs in native title claims to focus, not on the information value of the content of photographs, but on the trustworthiness of copies of photographs created by cultural institutions that may be tendered as evidence. In situating this case study in the legal context of native title, we draw on one real-world example to show how institutional practices for copying historical photographs by cultural institutions shape the value of photographs as evidence. We do this, mindful of the limited ways that photographs have been used in native title claims to date, as we believe there remains the future potential for these copying practices to be tested against the laws of evidence.

Photographs as evidence

Photographs are considered ‘documents’ for evidentiary purposes and are subject to the rules of evidence. For a photograph to be admitted as evidence, a witness needs to testify as to its trustworthiness which in archival terms relates in particular to its reliability, authenticity and integrity.Footnote17 A reliable record is one created and maintained (including copying) following proper procedures even if reliability does not ensure accuracy.Footnote18 It also needs appropriate metadata to support its reliability and useability as a trustworthy record.Footnote19 An authentic record is one that can be proven to be what it claims to be, and that has not been altered or corrupted in essential respects.Footnote20 A record that has integrity is complete and unaltered.Footnote21 A witness may have first-hand knowledge of the taking of the photograph and/or its subject, be able to speak to its relevance to the matter to hand, and can explain its authenticity based on knowledge of its provenance and chain of custody.

Uniform laws of evidence in relation to submitting copies to the court make it easier for copies (either digital or hard copy) to be admissible in court. However, if a party to the case questions a copy of a photograph tendered as evidence, a witness must be able to testify that the copy in and of itself is a trustworthy, authentic and unaltered representation of the original record. This means a witness may need to testify that they have seen the original and the copy or that the recordkeeping system documents the evidentiary values of the photograph and the relationship between the source and copy. To support their verbal testimony, a witness may need to draw on recordkeeping systems to show technical specifications, policies and procedures that guide copying, the accompanying metadata documenting the process, the source photograph and its surrogate. Then, a witness should be able to demonstrate that the copy is a trustworthy representation of the original photograph and that it is protected from unauthorized tampering or loss.Footnote22

Case study

The photographic record

In this case study, we raise questions about the trustworthiness of copies of photographs by drawing out the differences between multiple copies of the same historical photograph created by four cultural institutions and its source photograph. We accept that, in theory, a photograph is in itself a copy of a thing, act or event, and so its authenticity precedes the keeping of the record, and therefore we should also be concerned with its capture. We also accept that even an authentic image is not conclusive as to ‘the truth’ of the information it conveys given that many so-called historical photographs have been staged in some way.Footnote23

The source photograph in this case is a private record – it is a vintage photographic print made soon after the photographer created the negative. It is fixed to a page in a personal photograph album and accompanied by a handwritten caption. There is no evidence in human memory or documentation of the circumstances that surrounded the capture of the photograph itself, or the existence of the camera original, which in this case was a negative. In this case, the print in the album is the earliest extant generation of ‘the record,’ and this may be only one of many potential prints that may have been created for a range of purposes from that single negative.

The trustworthiness of this source photographic record is based on knowing that this photograph in an album is reliable and authentic. Confidence that this record is trustworthy is important to enable a reading of its content alongside understanding the context of the relationships between the photographer, the Indigenous people and the land on which they are photographed.

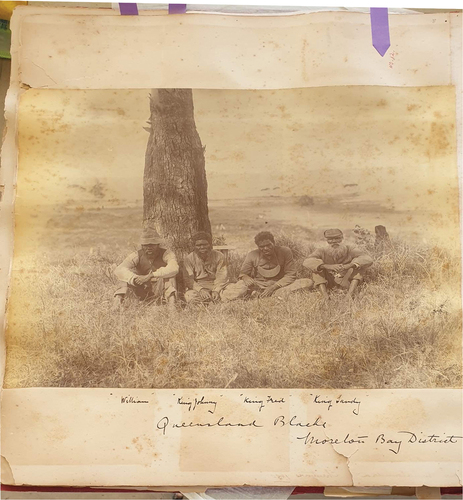

The photograph depicts four named senior Indigenous men seated together on the ground at Deception Bay, just to the north of Brisbane, dated from around 1896.Footnote24 The photograph is one of a number the photographer made when photographically recording life on properties owned by his family, and when working with these and other men to document their knowledge of traditional practices and Indigenous vegetable foods.Footnote25 These photographs taken for personal use and with the collaboration of those depicted, contrast markedly in style with colonial photographs taken for commercial purposes.Footnote26 This content of the photograph, its accompanying handwritten caption and its place in the album are together potentially significant as evidence for native title claims over this region for a number of reasons. When this page is seen in the context of the overall style and contents of the album, a viewer can build a picture of the close and trusting relationship between the photographer and Indigenous people that helps explain the relaxed style of this photograph. When the photograph and caption are viewed together, they identify and place these men in a location at a given time that potentially provides information as to the traditional country of the named men shown, and prompts thinking as to the relationships between them.

In addition to depicting a connection between now deceased people and their place and country, this captioned photograph is also relevant to contemporary living claimants articulating and/or discovering forebears who held customary rights to country. However, our research has shown that knowledge among native title claimants of connections between these four men and their known forebears is at best imprecise and subject to contested debate. So, while photographs are often used to support memories in other forms, this photograph and caption introduce some native title claimants to previously unknown ancestors and therefore ‘highlights the possibility of an awkward moment, when the colonial archive may be more authoritative than claimants’ oral memory.’Footnote27

Photographer

The photographer is Thomas Lane Bancroft, a Queensland-based medical doctor and naturalist with an inclination towards scientific research.Footnote28 Situated in the middle of three generations of a medical family, T.L. Bancroft stands out not only for his contributions to science but also for his significant photographic legacy. Bancroft was sufficiently conversant with chemistry to process his own negatives and prints. His surviving photographs dating from 1884 document his family, homes, industries with which he was associated and Indigenous people in the regions where he lived. In addition to creating individual prints, Bancroft compiled several photograph albums. Over 35 of his photographs of Indigenous people taken between October 1884 and c.1897 were printed several times and are dispersed internationally.Footnote29

The photograph

This sepia print is pasted into a single page of a photograph album compiled by Bancroft (). The print measures 11.5 × 9 5/16 inches and has a caption in his hand on the album page below the image on three lines.

Figure 1. Page of Bancroft Album (print is sepia). “William” “King Johnny” “King Fred” “King Sandy” “Queensland Blacks – Moreton Bay District”.

By naming the men in the photograph the caption provides information relevant to establishing possible forebears or apical ancestors of living Aboriginal people in the southeast Queensland region. Just where in the region the men held traditional rights in country requires further documentary and ethnographic research. Living claimants’ connections to one or more of the figures in the photograph is a matter for native title research involving genealogical studies of both documentary and oral histories.

That this photograph is pasted into a photograph album adds another layer of context and meaning that needs to be documented and preserved. As objects, the value in photograph albums is more than the sum of the individual photographs they contain, and their meaning comes from beyond the content of an individual photograph. Photograph albums are complex, multi-media assemblages that are ‘an amalgam of physical object, cultural artefact, historical record, individual images and visual narrative.’Footnote30 Much can be learned from their material form including card quality, bindings and mounts: those things that fix the images into a particular space and narrative order, and hold the album together.Footnote31

The album is itself unremarkable. It has a red cover, printed decorated endpapers and quality card and bindings. With neither embossed cover title nor inscription to explain the album, its contents alone reflect Bancroft’s mixed narrative intentions in the original order and associated captions. The album combines over 100 photographs of his family’s activities, the lives of Indigenous people and scientific observations including ticks, wasps and cattle diseases. The captions fix Bancroft’s view of each photograph, and these are the only surviving contemporary documentation of his intentions for reading, and the value he saw in, each photograph.Footnote32 The album remains in an unbroken chain of custody with his descendants where its social, cultural, scientific and historical significance sits between family memory and community and cultural heritage.

In our extensive research, we have only traced this one vintage print of this scene. It is most likely that Bancroft created this print himself from a negative that he also created. As the negative has not been found, it is not possible to see how the photographic print represents his intentions when transforming the negative using a range of darkroom techniques including dodging and burning, cropping, and enlarging.

The copies

Four institutions in Queensland have borrowed and copied parts of Bancroft’s collections of photographs including this particular photograph. This is a common practice that makes material held in private hands publicly available. They are discussed in chronological order of creation, dating from 1979 and span photographic and digital copying.

Queensland Museum

Queensland Museum (QM) has two acquisition records for this image. In 1979, the QM photographer Allan Easton created a strip of small 35 mm copy negatives and a registration card for that negative with the number LJ786 (). Beyond this registration card, QM holds no further correspondence surrounding this loan, nor is there documentation to show the size or source of the print or the existence of an associated caption.Footnote33 The information on the negative registration card is an exact transcription of the caption on the album page, and while its origin is not acknowledged, it suggests the QM had access to the source album. However, from the negative numbers, it is clear that at the time, the QM copied only the single photograph and not the whole album.

Figure 2. Strip of 35 mm negatives created in 1979. These multiple exposures show that this is the only image copied from the album, and how copying has cropped the image on the album page. Courtesy Queensland Museum LJ786.

In 2000, the widow of well-known Queensland collector Stan Colliver donated a copy print produced by the QM back to them.Footnote34 This was registered in 2002 and information in its detailed accession record gives the size of the copy print as 129 × 70 mm and the annotation on its reverse as ‘Bancroft Red Album Page 8 C A 32,’ the caption transcribed as it appeared on the album page, and the QM negative number L.J. 786. This annotation suggests that whoever originally created this print had access to the captioned vintage print in the red album.

The history of the Colliver copy print is unknown. However, this copy print has the same unusual dimensions (129×70 mm) and aspect ratio, and shows similar scratches as an image reproduced in a small local history publication, whose author Stan Tutt, was a friend of Colliver.Footnote35 This suggests that Colliver may have borrowed the album from the Bancroft family for the QM to copy this particular photograph for Tutt’s use, and this print was subsequently donated to the QM in 2000. However, there is no correspondence relating to this donation other than the accession record, and QM has been unable to confirm if C A 32 refers to an internal correspondence file.Footnote36 Of equal concern is that this Colliver donation remains a phantom now known only on the accession register as QM has been unable to find this modern copy print with its rich annotations on its reverse.Footnote37

State Library of Queensland

The State Library of Queensland (SLQ) has copied material loaned from various branches of the Bancroft family on at least seven occasions over several decades. According to accession sheets, these materials were reorganized and renumbered in 2005 into two fonds.Footnote38 The copy negative of this photograph created from a loan in 1999 is documented in Bancroft 7703, and the public access copy print is now held in album box 14567 (). Information handwritten in biro on the back of the public copy print includes the caption, the old accession number 99-2-2 and a negative number 180188 in pencil. The source of caption information on the reverse of the print is not cited, but its precise content and layout suggest it was likely transcribed from the original album page.

Figure 3. 6×7 cm copy negative, created in 1999. This negative shows the edges of the photograph and the top of the letters in the caption below the photograph. This indicates a caption exists but has not been photographically copied. Loaned by the Bancroft family, Courtesy State Library of Queensland 180188.

The 6 × 7 cm copy negative of this photograph has no scale in the image area and shows all edges of the print but not the edges of the album page. Of particular significance is that the tops of a few letters of a handwritten caption below the print are visible, and this suggests that the negative was copied directly from the album page. However, when the copy print was created for public access, the handwritten caption and the edges of the print were cropped out.

Queensland Institute for Medical Research Berghofer

The Bancroft family has a long connection to the Queensland Institute of Medical Research Berghofer (QIMR). However, it is not an obvious place to search for historical photographs of Indigenous people, nor is it a place that we would expect to adhere to the rigid collection management standards of an ideal archival world. The artist Judy Watson alerted the authors to this collection of Bancroft photographs when undertaking an artistic residency at the QIMR where her brief was to represent the Indigenous presence on the site.Footnote39

QIMR holds a collection of medium format copy negatives and copy prints derived from them. The photographer who created the negatives is thought to have been a now deceased University of Queensland medical photographer. There is no information about the source of the photograph that was copied, nor any record of the date, purpose and history of copying. However, information on the spine of the file containing the negatives suggests that prints held at SLQ were the source. The copy negative has been cropped more than the negative held at SLQ and shows no evidence of the handwritten caption on the album page (). The print on file has been cropped even more and has on its reverse ‘untitled.’

Moreton Bay Regional Council Local History Collection

The Moreton Bay Regional Council Local History Collection (MBLHC) holds two copies of the image which are both available online. One, copied directly from the Bancroft family album, was held in the Caboolture Library photograph collection and transferred to the MBLHC when several regional local government areas were amalgamated in 2008.Footnote40 Its custodial history is documented in the catalogue and the photograph is captioned ‘Aboriginal people of Moreton Bay’ with the names of the four men supplied. This image is available online but there is no evidence that the hard copy print remains in the MBLHC.

The other, a first-generation digital scan, was created directly from the original red album in 2007Footnote41 (). It was amongst a number of photographs copied by MBLHC for use in a local history publicationFootnote42 and on local heritage trail markers. The scan contains higher quality detail than any other copy and shows physical deterioration in the vintage print not seen in earlier copy negatives. This scan shows neither the edges of the print, the album page, nor the caption underneath.

Figure 5. Digital scan, 2008. This digital scan shows how copying has cropped the image on the album page. It also shows the gradual deterioration of the source photograph. Loaned by the Bancroft family, Courtesy MBLHC Bancroft family collection MBPS-0006-229.

Each copy has its own catalogue record. While the description of the image is consistent in each catalogue record, the records show no information about the size of original print nor its source in an album. Neither did the MBLHC document if the whole album was copied or if the original order was retained in the numbering system.Footnote43

Five documents

In theory, each copy negative and print derived from a single first generation negative, is a different document because each copy negative, print or scan was created at a different time, by a different photographer and for a different purpose.Footnote44 In this case, with four copy negatives and a digital scan copied from the same source, the relationships are, in theory, more complex. On the one hand, each copy negative/scan in an institution is a document that has its own provenance and history; on the other, each copy negative/scan also remains forever anchored to its source image – the original photograph in the album. In this sense, there are ‘multiple original’ copy negatives/scans that should be anchored to the single source print in the album, while each copy negative/scan carries with it its own provenance and history of having been copied.

Let us assume that the red album that remains in the hands of the photographer’s descendants is authentic and unaltered. In the absence of evidence to the contrary, it is also likely that the print in the red album was the source of all of the copy negatives and the digital scan. Even in the absence of documentation as to the source of these copies, users are likely to assume the photographic and digital copies made by cultural institutions are trustworthy and unaltered representations of the source photograph and that they will meet their proposed use. However, users may be less inclined to trust a digital surrogate as we assume that it is much easier to alter a digital record after the fact.Footnote45

While there may be in-principle trust in institutional copying practices, when several copies of this photograph are viewed together, remarkable variations in the presentation of the image content are visible. As show, each copy has been altered as the image area has been cropped in different ways.

Each negative, and print examined here differs in its content and aspect ratio;

None of the negatives includes a scale, shows the whole album page, or includes the caption in full;

In one (), the negative indicates a caption below the print on the album page;

Three copy prints produced from the copy negatives show that in printing, information, including evidence of a caption, was cropped out from the negative;

The one first generation digital scan from the original photograph did not include the album page, the edges of the photograph, or the caption;

The most detailed accession record is for a copy print that cannot be located.

Trustworthiness: quality of copies

Let us return hypothetically to native title legal proceedings, whether court supervised mediation or litigation, and consider how an expert or lay witness may respond were they asked to testify that one or all of these copies () are trustworthy or to outline their shortcomings as evidence. There are a number of principles and elements that need to be addressed in relation to the differences between these copies, and responses may draw on the copies themselves as well as the recordkeeping system that documents them.

Authenticity

An authentic copy is one that can be proven to be what it claims to be.Footnote46 In relation to provenance, our research has shown the likely source of each copy is the vintage print in the red album held by descendants of Bancroft. However, a researcher is likely to rely on information provided by institutions to establish the authenticity – in this case the provenance of a copy of a photograph in an album. In this case, only two institutions have documented the family as the source of the loan of material. Only one institution documented that the source was a photograph album that contained the photograph. No institution documented the original source in full: the original order of the album, physical details of the album page including weight of card, size of the print or the caption. While some institutions copied only the single photograph, no institution documented whether the whole of the album was copied, reasons why only a part or parts of the album were copied, or if the original order of the album was retained in the numbering systems.

Reliability

A reliable record is one whose contents can be trusted to be a full and accurate representation.Footnote47 During the period when these photographic copies were created, there were accepted standards for copying documents using microfilm to ensure that copies of documents were trustworthy, reliable and authentic. This included elements such as edge-to-edge copying, scales and an audit trail of the copying process. While documentation in three institutions shows the date of copying, procedures to explain the copying processes for photographs in each institution do not survive to explain why each copy is different.

Integrity

A record that has integrity is one that is complete and unaltered.Footnote48 Cropping of an image fundamentally alters its content and the relationship between the source photograph and its copy negative or digital surrogate. No institution copied the photograph in context on the album page with its full caption, and each copy negative shows the image is different in shape and size and has cropped out background information that is important to identify the location in the photograph. Only one institution acknowledged a handwritten caption in its acquisition documentation. Even when the catalogues of two institutions, and the back of one print contain information transcribed from the caption, the source of the information is unidentified.

Useability

A record first needs to be located by using a recordkeeping system and then connected to the transaction that produced it.Footnote49 In this case, one item could not be located physically within the institution. In publicly accessible metadata, two institutions identified the creator of the photograph, one institution added subject headings relating to Indigenous people or places that are adequate to retrieve the image, while none entered accession or negative numbers to enable retrieval of the item. Only one institution has placed the digital image online.

Recordkeeping system

To be a trustworthy copy of a record, and to have value as evidence, a recordkeeping system needs to document the link between the data content, and the context of creation and use of the records.Footnote50 For a copy of this photograph to be trustworthy, the recordkeeping system needs to anchor each copy to its source image alongside an audit trail of being copied. In this case, the recordkeeping system should also document the source photograph within its context (the red album), and its provenance and original order, and the caption of the photograph. Of the four institutions that have copied the same photograph, institutional recordkeeping systems show that no institution has documented fully either the processes and audit trail behind the copying processes, or the copy of the photograph itself and its connection to the source. Nor do these systems acknowledge the existence of a caption or the source of information about the contents of the photograph.

In this case, we have been able to supplement the institutional recordkeeping systems with another significant recordkeeping system — the corporate memory bank of retired and occasionally current staff. These ‘informal recordkeeping systems’ have helped fill gaps for this research, identified handwriting and explained historic copying and acquisition practices. On occasions, former staff described the documentation that was once created, even if it has not been found, or perhaps exists but for whatever reason has not been released. These recollections have turned out to be remarkably accurate. However, oral information is fragile and only lasts for the lifetime of its carrier, and as is often the case, the nuances in corporate knowledge do not necessarily make the permanent record. This is particularly important as, in response to our requests for detailed information, current staff of a couple of institutions reported that they do not trust the institutional documentation as they can see that it is incomplete, inaccurate or misleading.

Trustworthiness: multiple original copies

When a researcher provides an expert opinion or a witness testifies as to the trustworthiness of the copy, they can also draw on the visual information within the copy photograph. In this example, there are notable differences in the content and aspect ratio between the copy negatives and scan, and between each copy and the source photograph. These physical variations in cropping the caption and photograph during copying have altered the content of each copy. Given these differences between copies, the question remains whether an expert or lay witness could testify that any one or all of these multiple original copies are a trustworthy – reliable or authentic – copy of the vintage print in the source album. The answer is, it depends on what one is looking for and how one is viewing the copy.

When one of the copy negatives/scans or copy prints is viewed in isolation from other copies, an expert or lay witness is unable to testify as to the trustworthiness of any copy as they have no visual points of comparison with other copies to see if it has been altered. Also, speaking to a single copy negative/scan or copy print would be unlikely to suggest the trustworthiness of a single copy when it is viewed in isolation from the audit trail of the copying process and its source.

When several of the copies held in institutions are seen together, then differences emerge between them that are not visible when viewing one item alone. These differences show that on each occasion the source photograph has been copied and subsequently printed, the image has been altered in several ways. Some of these differences are easy to see in – for example that each negative/scan has a different aspect ratio to others and to the vintage print, and that landscape information that can be used to identify the precise location of the photograph has been cropped. Other alterations become apparent on closer inspection including comparing the copy negatives to show how the visual (image content), material form (edge of photographs) and textual information (caption) has been cropped.

When the copy negative is seen alongside publicly accessible prints produced from the copy negatives, it can be seen that the image area has been further cropped, thus showing that the copy print is visually different from the copy negative and from the source print.

What if the shortcomings of any single copy of this photograph and its associated documentation are too great for a researcher or witness to testify as to its trustworthiness? In this case, the commentator could, with time and effort, corroborate all discoverable copies and the fragmentary records about each to build a composite audit trail and copying history of each. Professional archival expertise would assist where relevant and available. When they are viewed together and in relation to the information about them, it becomes clear that the image content of these copies has been altered and institutional records and recordkeeping systems contain incomplete information about the relationship between the copy and its source. However, if a witness can discuss the differences in the copies and the fragmentary information about them, they could suggest the likely existence of a common source photograph. This then means it is more likely that the legal process could apprehend the trustworthiness of the copies themselves and the information that together they reveal.

What are the implications for Native Title?

At present, photographs are generally valued in native title claims for their information content, and the trustworthiness of photographic copies has yet to be tested in court. However, as this remains a live possibility in future, expert researchers and claimant witnesses may well encounter the question of the trustworthiness of one or more copies of original images. The lesson for anthropologists, archaeologists and historians who are engaged to provide professional research services to native title parties is that archival literacy is important. Greater knowledge of the copying practices in cultural institutions will assist investigations of the significance of historical photographs for establishing the identities of Indigenous people present in claim locations in earlier times. Ideally, it ought not be just a single copy of a relevant photograph that undergoes interrogation, in cases where inquiries can reveal data also derived from an original image.

Photographs can be of considerable significance in native title claims to provide compelling evidence of people and connections to place back beyond the oral memories of living claimants. The photograph we have discussed contains a caption that adds important information about earlier generations of Aboriginal people living in a particular region. The photograph ought to prompt genealogical study seeking to clarify descendants of the men in the photograph as well as the relationships among those portrayed at such an early stage of colonial settlement in the southeast corner of Queensland. Information about the photographer and the context in which the original image was produced can potentially enrich the possibilities of findings about who have become known in native title claims as the ‘right people’ for the country who have inherited traditional rights in ‘country.’

Institutional copying

This case study is based on a single example and remains hypothetical, yet it raises significant questions about the trustworthiness of institutional copies of archival photographs and institutional cultures as reflected in copying practices for archival photographs. If what institutions do to source materials in their custody is shaped by and reflects how those in institutions think about the materials, then institutional copying practices suggest a culture that supports different ways of thinking about the various archival forms of material in their care. Here, we have drawn on the differences between multiple copies of a single source to show that institutional copying practices shape how they can be used and this directly affects their trustworthiness as evidence.

Copying any form of material is always an act of re-presentation. The case material suggests that aspects of institutional copying practices have been remarkably persistent over the decades, across different technologies and types of cultural institutions. These have persisted despite institutions adopting longstanding international standards and guidelines that were developed to ensure a reliable framework for creating authentic copies of documents and an audit trail for legal purposes.Footnote51 Technical and documentation requirements to create trustworthy copies of documents or photographs share common principles, albeit with nuances that apply for the specifics of each format.

This study also suggests that institutional copying culture has resisted learning from the promise of trustworthiness that underpinned copying standards for microfilm that could have long been equally applied to copying photographs.Footnote52 This resistance exposes practices that value creating trustworthy copies of documents while not applying the same standards to creating copies of photographs. The shift in copying technology from photographic to digital was a moment where the promise of trustworthiness could have been embedded in standards for copying archival photographs. Instead, as the current plethora of frameworks that guide best practices for the management of digitization projects attest, that opportunity to embed that promise in digitization standards has, for now, been lost. The current frameworks for digitization projects are format neutral, focus on the technical processes of digitization and are dispersed across such functions as workflows, technical aspects of image capture, metadata standards and digital preservation.Footnote53 In the absence of a principle of creating trustworthy copies, and with their focus on the technical processes of digitization, these frameworks continue to codify copying practices that place a value on image content without considering the nuances of how copying practices change meanings of the materials.

Do institutions currently create trustworthy copies? In this case study, as more generally, the copying practices of institutions are shaped by guidelines that do not codify copying practices to ensure their authenticity and integrity. The overall goal of the US FADGI guidelines for digitizing cultural heritage materials is to create ‘faithful’ reproductions for preservation and access purposes.Footnote54 The National Archives of Australia Preservation Digitisation Standards are informed by guiding principles to ensure the digital copy is an ‘effective long-term surrogate for paper and analogue originals’ including to ‘capture a complete and accurate archival record of analogue collection items.’Footnote55 Neither of these documents draws on definitions in recordkeeping standards to inspire trust in the copies, nor do they identify the value of photographs beyond their image content.

What if the goal of a guideline was to capture and manage authentic and trustworthy digital copies? This would require a change in the understanding of a photograph from being seen as an image to being understood as a document, and shift the purpose of digitizing activities from documenting the illustrative values of photographs to preserving their evidential values.Footnote56 This new guideline could then describe how to preserve the evidential values of photographs and their copies and explain why it is important to do so. It could draw on recordkeeping standards and photographic, material culture and archival theory to describe the components of photographs or other visual formats that comprise the evidentiary values, amend the technical standard to outline how to copy and document these, and address how to preserve the relationships between the source and its copy.

While recordkeeping and legal standards of evidence are different in detail, one common goal in preserving records as evidence or for evidentiary purposes relates to the trustworthiness of the record or its copy. This case study is based on a source photograph with potential value to native title claims in order to sharpen questions about the trustworthiness of copies of archival photographs produced by cultural institutions. While these questions have yet to be tested in legal native title procedures, it is our view that the promise of photographs for native title outcomes will come to rest with the trustworthiness of institutionally created copies. Critiques of copying photographs began in earnest with the change in copying technology from photographic to digital. However, this case study suggests that it is not the copying technology that limits the creation of trustworthy copies of archival photographs. Rather, it is the way that those in institutions think about photographs that limits our capacity to determine whether copies of photographs are trustworthy. The Australian native title context provides one indicative setting in which institutional practices can become directly implicated in the kind of data that addresses histories of connections to country on the part of Indigenous groups and individuals.

Acknowledgments

An earlier version of this paper was presented as part of a panel session “From illustration to evidence. Photographs in native title” with Michael Aird, Joanna Sassoon and David Trigger, Australian Society of Archivists, Brisbane, Australia [virtual conference] September 2021. A number of people have assisted with or discussed ideas in this paper including Karen Anderson, Gavan Bannerman, The Bancroft family, Heather Brown, Chris Hurley, Michael Piggott, Michael Quinnell, Barbara Reed, Catherine Robinson and Joan Schwartz.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Joanna Sassoon

Joanna Sassoon is an historian and archivist. She has published widely across photographic, environmental, Indigenous and oral history. Her current research interests bring together archival theory, Australian photography and cultural institutional practice. Her first and award-winning book is Agents of Empire: How E.L. Mitchell’s Photographs Shaped Australia (2017). Her work includes teaching and research roles at Curtin University and the University of Queensland.

Michael Aird

Michael Aird is the Director, Anthropology Museum, School of Social Science, University of Queensland and ARC Research Fellow. He has worked in the area of Aboriginal arts and cultural heritage since 1985, maintaining an interest in documenting aspects of urban Aboriginal history and culture. He has curated over 30 exhibitions and has been involved in numerous projects in areas relating to historical photographs and representations of Aboriginal people. In 1996 he established Keeaira Press, an independent publishing house, producing over 35 books.

David Trigger

David Trigger is Emeritus Professor of Anthropology at the University of Queensland and Adjunct Professor at the University of Western Australia. He is the principal partner in David S Trigger & Associates consulting anthropologists. His research interests encompass the different meanings attributed to land and nature across diverse sectors of society. In Australian Aboriginal studies, Professor Trigger has carried out more than 35 years of anthropological study on Indigenous systems of land tenure, including applied research on resource development negotiations and native title. Professor Trigger is the author of Whitefella Comin’: Aboriginal Responses to Colonialism in Northern Australia (1992) and a wide range of scholarly articles.

Notes

1. Schwartz, “Working Objects,” 517.

2. Powell, “Origins of the Australian Joint Copying Project;” Simon, “1956–2006: Fifty Years;” Boylan, “The Cooperative Africana Microform Project;” and Cunningham and Maidment, “The Pacific Manuscripts Bureau.”

3. Sassoon, “Photographic Meaning;” Sandweiss, “Image and Artifact;” and Conway, “Digital Transformations.”

4. Payne, “Culture, Memory and Community;” Odumosu, “The Crying Child;” and Pasternak, “Photographic Digital Heritage in Cultural Conflicts.”

5. Christen, “Opening Archives: Respectful Repatriation;” Thorner and Dallwitz, “Storytelling Photographs, Animating Anangu;” and Pasternak, “Photographic Digital Heritage in Cultural Conflicts.”

6. Caswell and Cifor, “From Human Rights;” Cook and Schwartz, “Archives, Records, and Power;” Dalgleish, “The Thorniest Area;” Odumosu, “The Crying Child;” Punzalan and Caswell, “Critical Directions;” and Schwartz and Cook, “Archives, Records, and Power.”

7. Manžuch, “Ethical Issues;” and Conway, “Preservation in the Age of Google.”

8. Agostinho, “Archival Encounters.”

9. Duff, “Harnessing the Power of Warrant;” Brothman, “Afterglow;” and Cox and Duff, “Warrant and the Definitions of Electronic Records.”

10. Meehan, “Towards an Archival Concept of Evidence,” 133.

11. Barbara Reed, Recordkeeping consultant, pers. comm. to authors 22 October 2021.

12. Carter, “Ocular Proof.”

13. Aird et al., “From Illustration to Evidence,” 3.

14. Australia New Zealand Policing Advisory Agency (2013) Australia and New Zealand Guidelines.

15. Federal Court judgments relating to native title that mention photographs, albeit briefly, include Risk v Northern Territory of Australia 2006 FCA 404 [37, 590, 774]; Harrington-Smith on behalf of the Wongatha people (no. 9) v State of Western Australia 2007 FCA 31 [1822, 1825, 1833]; De Rose v State of South Australia 2002 FCA 1342 [370]; Sandy on behalf of the Yugara People v State of Queensland (No 2) 2015 FCA 15 [272, 274]).

16. Aird et al., “From Illustration to Evidence,” 19.

17. International Organization for Standardization, 15489–1: S5.2.2.

18. Ibid., S5.2.2.

19. Ibid., S5.2.3; S5.2.2.2; S5.2.2.4.

20. Ibid., S5.2.2.1.

21. Ibid., S5.2.2.3; and MacNeil, “Picking Our Text.”

22. State Records New South Wales, Legal Admissibility of Digital Records.

23. For overviews of debates around representation and truth value from different disciplinary perspectives see for example Ray, “Social Theory, Photography;” Schwartz, “Working Objects;” and Edwards, Anthropology and Photography.

24. This photograph is in the public domain. Michael Aird, an author of this article, has family connections to one of the men in the photograph, and has spent over 35 years researching historical photographs that survive in cultural institutions and within Indigenous families. Aird’s research is widely known and valued across Indigenous communities of southeast Queensland.

25. Bancroft, “Note on Bungwall (Blechnum serrulatum, Rich).”

26. See for example Donaldson and Donaldson, eds., Seeing the First Australians.

27. Aird et al, “From Illustration to Evidence,” 19.

28. Marks, “Bancroft, Thomas Lane.”

29. For example Photographs of Billy Keogh. Pitt Rivers Museum, Oxford 1998.270.6.1; 1998.270.6.2; and Nicholls collection (c.1860–1979). Bristol Archives British Empire and Commonwealth collection. 2002/169.

30. Schwartz, “Photography, Travel, Archives,” 963.

31. Edwards and Hart, eds., Photographs, Objects, Histories.; Driver, “Material Memories of Travel;” and Schwartz, “Photography, Travel, Archives.”

32. Bann, ed., Art and the Early Photograph Album; and Edwards and Hart, eds., Photographs, Objects, Histories.

33. Donna Millar, DAMS Administrator QM Network, pers. comm. to the authors 16 and 18 August, 2021.

34. Harrison,“Colliver, Frederick Stanley (Stan).”

35. Tutt, From Spear & Musket, 26.

36. Julia Waters, Records Manager QM, conversation with the authors 16 June 2021.

37. Geraldine Mate, Principal Curator Cultures and History Programme, QM, pers. comm. to the authors 20 April, 2021; and Karen Kindt, Collection Manager Anthropology, QM, pers. comm. to the authors 9 May, 2019.

38. ”Bancroft Family Copy Prints 1894–1933,” State Library of Queensland 6097; and “Bancroft Photograph Albums 1908–1932,” State Library of Queensland 7703.

39. QIMR Berghofer, A Celebration of Art and Science.

40. ”Aboriginal People of Moreton Bay,” Moreton Bay Local History Collection. MBLHC CLPC-P1614.

41. ”Aboriginal People of the Moreton Bay District,” Moreton Bay Local History Collection. MBLHC MBPS-0006-229; and Kelly Ashford, MBLHC pers. comm. to authors 11 January 2022.

42. Blake and Osborne, Deception Bay.

43. Kelly Ashford, MBLHC pers. comm. to authors 5 March 2020.

44. Schwartz, ‘’We Make Our Tools,” 46.

45. Millar, A Matter of Facts, 29.

46. International Organization for Standardization, 15489–1: S5.2.2.1.

47. Ibid., S5.2.2.2.

48. Ibid., S5.2.2.3.

49. Ibid., S5.2.2.4.

50. Bearman, “Documenting Documentation;” Bearman, “Record-Keeping Systems;” and International Organization for Standardization, 15489–1: S5.2.3.

51. Association for Information and Image Management International, Standard Recommended Practice, 7; Fox ed., Preservation Microfilming; and National Library of Australia, Guidelines for Preservation Microfilming.

52. Association for Information and Image Management International, Standard Recommended Practice, 7.

53. International Organization for Standardization, Information and Documentation — Implementation Guidelines for Digitizing of Records; National Archives of Australia, Preservation Digitisation Standards; and National Library of Australia, Image Capture Standards.

54. Federal Agencies Digital Guidelines Initiative, Technical Guidelines for Digitizing Cultural Heritage Materials.

55. National Archives of Australia, Preservation Digitisation Standards.

56. See for example Australia New Zealand Policing Advisory Agency (2013) Australia and New Zealand Guidelines for Digital Imaging Processes.

Bibliography

- Primary sources

- “Aboriginal people of Moreton Bay”. Moreton Bay Local History Collection, MBLHC CLPC-P1614. Accessed 5 Jan. 2022. https://library.moretonbay.qld.gov.au/cgi-bin/spydus.exe/ENQ/WPAC/ARCENQ?SETLVL=&RNI=933280.

- “Aboriginal people of the Moreton Bay District”. Moreton Bay Local History Collection, MBLHC MBPS-0006-229. Accessed 5 Jan. 2022. https://library.moretonbay.qld.gov.au/cgi-bin/spydus.exe/ENQ/WPAC/ARCENQ?SETLVL=&RNI=1066747.

- Bancroft Family Copy Prints 1894-1933. State Library of Queensland, 6097. Accessed 5 Jan. 2022. http://onesearch.slq.qld.gov.au/permalink/f/fhnkog/slq_alma21148825900002061.

- Bancroft Photograph Albums 1908-1932. State Library of Queensland 7703. Accessed 5 Jan. 2022. http://onesearch.slq.qld.gov.au/permalink/f/fhnkog/slq_alma21148394130002061.

- Nicholls Collection (c.1860–1979). Bristol Archives British Empire and Commonwealth Collection.

- Photographs of Billy Keogh. Pitt Rivers Museum Oxford 1998.270.6.1 and 1998.270.6.2.

- Legal cases

- De Rose v State of South Australia. (2002). FCA 1342. https://www.judgments.fedcourt.gov.au/judgments/Judgments/fca/single/2002/2002fca1342.

- Harrington-Smith on behalf of the Wongatha people (no. 9) v State of Western Australia. FCA 31. 2007. https://www.judgments.fedcourt.gov.au/judgments/Judgments/fca/single/2007/2007fca0031.

- Risk v Northern Territory of Australia. (2006). FCA 404. https://www.judgments.fedcourt.gov.au/judgments/Judgments/fca/single/2006/2006fca0404.

- Sandy on behalf of the Yugara People v State of Queensland (No 2) (2015). FCA 15. https://www.judgments.fedcourt.gov.au/judgments/Judgments/fca/single/2015/2015fca0015.

- Secondary sources

- Agostinho, Daniela. “Archival Encounters: Rethinking Access and Care in Digital Colonial Archives.” Archival Science 19 (2019): 141–165. doi:10.1007/s10502-019-09312-0.

- Aird, Michael. “From Illustration to Evidence. Historical Photographs and Aboriginal Native Title Claims in South-East Queensland, Australia.” Anthropology and Photography 13, no. 1 (2020). https://therai.org.uk/images/stories/photography/AnthandPhotoVol13.pdf.

- Association for Information and Image Management International. Standard Recommended Practice – Production, Inspection and Quality Assurance of First Generation Silver Microforms of Documents. ANSI/AIIM MS23-1998.

- Australia New Zealand Policing Advisory Agency. Australia and New Zealand Guidelines for Digital Imaging Processes. Docklands, Victoria: ANZPAA, 2013. https://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-275320904/view.

- Bancroft, Thomas Lane. “Note on Bungwall (Blechnum serrulatum, Rich.), an Aboriginal Food.” Proceedings of the Linnean Society of New South Wales, 9 (1894): 25–26.

- Bann, Stephen, ed. Art and the Early Photograph Album. Washington DC: National Gallery of Art, 2011.

- Bearman, David A. “Documenting Documentation.” Archivaria 34 (1992): 33–49.

- Bearman, David A. “Record-Keeping Systems.” Archivaria 36 (1993): 16–36.

- Blake, Thom, and Peter Osborne. Deception Bay: The History of a Seaside Community. Caboolture Queensland: Caboolture Shire Council, 2008.

- Boylan, Ray. “The Cooperative Africana Microform Project.” Microform Review 15, no. 3 (1986): 167–171. doi:10.1515/mfir.1986.15.3.167.

- Brothman, Brien. “Afterglow: Concepts of Record and Evidence in Archival Discourse.” Archival Science 2, no. 3 (2002): 243–311. doi:10.1007/BF02435627.

- Carter, Rodney. “Ocular Proof. Photographs as Legal Evidence.” Archivaria 69 (2010): 23–47.

- Caswell, Michelle L., and Marika Cifor. “From Human Rights to Feminist Ethics: Radical Empathy in the Archives.” Archivaria 81 (2016): 23–43. muse.jhu.edu/article/687705.

- Christen, Kimberly. “Opening Archives: Respectful Repatriation.” The American Archivist 74, no. 1 (2011): 185–210. doi:10.17723/aarc.74.1.4233nv6nv6428521.

- Conway, Paul. “Preservation in the Age of Google: Digitization, Digital Preservation, and Dilemmas.” Library Quarterly: Information, Community, Policy 80, no. 1 (2010): 61–79. doi:10.1086/648463.

- Conway, Paul. “Digital Transformations and the Archival Nature of Surrogates.” Archival Science 15 (2015): 51–69. doi:10.1007/s10502-014-9219-z.

- Cook, Terry, and Joan M. Schwartz. “Archives, Records, and Power: From (Postmodern) Theory to (Archival) Performance.” Archival Science 2, no. 3–4 (2002): 171–185. doi:10.1007/BF02435620.

- Cox, Richard J., and Wendy Duff. “Warrant and the Definitions of Electronic Records: Questions Arising from the Pittsburg Project.” Archives and Museum Informatics 11, no. 3–4 (1997): 223–231. doi:10.1023/A:1009008706990.

- Cunningham, Adrian, and Ewan Maidment. “The Pacific Manuscripts Bureau: Preserving and Disseminating Pacific Documentation.” The Contemporary Pacific 8, no. 2 (1996): 444–454.

- Dalgleish, Paul. “The Thorniest Area: Making Collections Accessible Online While Respecting Individual and Community Sensitivities.” Archives and Manuscripts 39, no. 1 (2011): 67–84.

- Donaldson, Ian, and Tamsin Donaldson, eds. Seeing the First Australians. Sydney: Allen and Unwin, 1985.

- Driver, Felix. “Material Memories of Travel: The Albums of a Victorian Naval Surgeon.” Journal of Historical Geography 69 (2020): 32–54. doi:10.1016/j.jhg.2020.02.006.

- Duff, Wendy M. “Harnessing the Power of Warrant.” The American Archivist 61, no. 1 (1998): 88–105. doi:10.17723/aarc.61.1.j75wk8152n5u7r52.

- Edwards, Elizabeth. Anthropology and Photography 1860-1920. New Haven: Yale University Press. 1992.

- Edwards, Elizabeth, and Janice Hart, eds. Photographs, Objects, Histories. On the Materiality of Images. London: Routledge, 2004.

- Federal Agencies Digital Guidelines Initiative. Technical Guidelines for Digitizing Cultural Heritage Materials. 2022. https://www.digitizationguidelines.gov/guidelines/DRAFT%20Technical%20Guidelines%20for%20Digitizing%20Cultural%20Heritage%20Materials%20-%203rd%20Edition.pdf.

- Fox, Lisa L., ed. Preservation Microfilming a Guide for Librarians and Archivists for the Association of Research Libraries. 2nd edition. Chicago: American Library Association. 1996.

- Harrison, J. “Colliver, Frederick Stanley (Stan) (1908–1991).” In Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography. Australian National University, 2014. https://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/colliver-frederick-stanley-stan-15919/text27120

- International Organization for Standardization. Information and Documentation – Implementation Guidelines for Digitizing of Records. ISO/TR 13020-2010.

- International Organization for Standardization. Information and Documentation. Records Management. Part 1. Concepts and Principles. 2nd ed. ISO15489-1-2017.

- MacNeil, Heather. “Picking Our Text: Archival Description, Authenticity, and the Archivist as Editor.” The American Archivist 68, no. 2 (2005): 264–278. doi:10.17723/aarc.68.2.01u65t6435700337.

- Manžuch, Zinaida. “Ethical Issues in Digitization of Cultural Heritage.” Journal of Contemporary Archival Studies 4, art. 4 (2017). https://elischolar.library.yale.edu/jcas/vol4/iss2/4.

- Marks, Elizabeth N. “Bancroft, Thomas Lane (1860–1933).” In Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography. Australian National University, 1979. https://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/bancroft-thomas-lane-5120

- Meehan, Jennifer. “Towards an Archival Concept of Evidence.” Archivaria 61 (2006): 127–146.

- Millar, Laura A. A Matter of Facts. The Value of Evidence in an Information Age. Chicago: Society of American Archivists, 2019.

- National Archives of Australia. Preservation Digitisation Standards 2021. https://www.naa.gov.au/about-us/our-organisation/accountability-and-reporting/archival-policy-and-planning/preservation-digitisation-standards

- National Library of Australia. Guidelines for Preservation Microfilming in Australia & New Zealand. Canberra: National Library of Australia, 1998.

- National Library of Australia. Image Capture Standards. n.d. Accessed 5 Jan 2022. https://www.nla.gov.au/about-us/corporate-documents/policy-and-planning/standards/digitisation-guidelines/image-capture.

- Odumosu, Temi. “The Crying Child. On Colonial Archives, Digitization and Ethics of Care in Cultural Commons.” Current Anthropology 61, no. S22 (2020): S289–302. doi:10.1086/710062.

- Pasternak, Gil. “Photographic Digital Heritage in Cultural Conflicts: A Critical Introduction.” Photography & Culture 14, no. 3 (2021): 262–268. doi:10.1080/17514517.2021.1953763.

- Payne, Carol. “Culture, Memory and Community Through Photographs: Developing an Inuit-Based Methodology.” Anthropology and Photography 5 (2016). http://www.therai.org.uk/images/stories/photography/AnthandPhotoVol5.pdf.

- Powell, Graeme. “Origins of the Australian Joint Copying Project.” Archives and Manuscripts 4, no. 5 (1971): 9–24.

- Punzalan, Ricardo L., and Michelle Caswell. “Critical Directions for Archival Approaches to Social Justice.” The Library Quarterly 86, no. 1 (2016): 24–42. doi:10.1086/684145.

- QIMR Berghofer. A Celebration of Art and Science. A Celebration of Art and Science 10 April 2013. https://www.qimrberghofer.edu.au/media-releases/a-celebration-of-art-and-science/.

- Ray, Larry. “Social Theory, Photography and the Visual Aesthetic of Cultural Modernity.” Cultural Sociology 14, no. 2 (2020): 139–159. doi:10.1177/1749975520910589.

- Sandweiss, Martha A. “Image and Artifact: The Photograph as Evidence in the Digital Age.” Journal of American History 94, no. 1 (2007): 193–202. doi:10.2307/25094789.

- Sassoon, Joanna. “Photographic Meaning in the Age of Digital Reproduction.” LASIE 29, no. 4 (1998): 5–15.

- Schwartz, Joan M. “’We Make Our Tools and Our Tools Make Us’: Lessons from Photographs for the Practice, Politics, and Poetics of Diplomatics.” Archivaria 40 (1995): 40–74.

- Schwartz, Joan M. “Photography, Travel, Archives.” In SAGE Handbook of Historical Geography, edited by Mona Domosh, Michael Heffernan, and Charles W.J. Withers, 959–987. London: SAGE Publications, 2020a.

- Schwartz, Joan M. “‘Working Objects in Their Own Time’: Photographs in Archives.” In The Handbook of Photography Studies, edited by Gil Pasternak, 513–529. London: Routledge, 2020b.

- Schwartz, Joan M, and Terry Cook. “Archives, Records, and Power: The Making of Modern Memory.” Archival Science 2, no. 1–2 (2002): 1–19. doi:10.1007/BF02435628.

- Simon, James. “1956-2006: Fifty Years of the Foreign Newspaper Microfilm Project.” Focus on Global Resources 26, no. 1 (2006). https://www.crl.edu/focus/article/463.

- State Records New South Wales. Legal Admissibility of Digital Records. June 2019. https://www.records.nsw.gov.au/recordkeeping/legal-admissibility-and-credibility-digital-images.

- Thorner, Sabra, and John Dallwitz. “Storytelling Photographs, Animating Anangu. How Ara Irititja – an Indigenous Digital Archive in Central Australia Facilitates Cultural Reproduction.” In Technology and Digital Initiatives. Innovative Approaches for Museums, edited by Juilee Decker, 53–60. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2015.

- Tutt, Stan. From Spear & Musket 1879-1979, Caboolture Centenary: Stories of the Area Once Controlled by the Caboolture Divisional Board, Shires of Pine Rivers, Caboolture, Kilcoy, Landsborough, Maroochy, Landsborough and City of Redcliffe. Caboolture, Queensland: Caboolture Shire Council, 1979.