ABSTRACT

The catchment of the Richmond River in Lismore, Australia, presents a challenge for record collection and preservation. Firstly, material records belonging to the community are periodically destroyed in flooding. The places where these are physically located as historical archives are often situated in the floodplain. Secondly, relevant records are dispersed across multiple government levels and organizations, posing further threats to their preservation and access. This paper seeks to explore those challenges and describe the development of a river repository at Southern Cross University, funded in part through a grant for flood recovery projects. The repository and our research are motivated by the challenges and considerations surrounding the preservation and management of cultural and scientific materials in the current era, characterized by human impact on the environment and climate change and the integration the Anthropocene heralds between the human and non-human world. Digital stewardship encompasses caring for and managing records and data, goals we extend to the Richmond River and its health.

Introduction

The 2022 floods in Northern New South Wales, Australia, demonstrated the vulnerability of local archives and the urgent need for records and information. It has long been recognized that climate change, the increase and extremity of natural disasters and their associated environmental factors pose a significant threat to physical archives. This threat is made more urgent by their value as assets that strengthen a community’s ability to adapt and recover from its impact. Strategies such as off-site storage and digitization have been recommended as adaptation measures to mitigate this risk. Archiving in the Anthropocene, however, requires a much broader perspective that recognizes the interdependence of human and environmental systems and the need for sustainable practices in all aspects of archival management. This paper will focus on the Richmond River Open Access Repository (RROAR) as a developing case study for the rich cultural and scientific records that help us make sense of our relationship to rivers and the environment more broadly.

We understand the imperative of environmental literacy and the role that information and scholarship can play in raising awareness of the relationship between humans and the environment and providing insights that support climate adaptation. As a librarian and historian, our collaboration is directed to practice and scholarship. As Karin Wulf and Amanda Strauss observe, the bifurcation between archivists and librarians on the one side and scholars on the other emerges from distinct professional training and expertise in acquiring, describing, processing and preserving materials and reading and using those materials. Bringing these two perspectives to bear on how we study artefacts and how they came to be produced and preserved provides important context.Footnote1 The processes of establishing a repository by forming a collection and acquiring and describing artefacts are themselves historical; making these assets accessible and using them cannot be separated from the conditions of their production and organization. This paper, therefore, is a collaboration that traverses the boundaries of our disciplines. In the context of a repository about a river, digital stewardship involves not only concern for the preservation of cultural artefacts and scientific data for future generations but also takes a whole-life approach to digital objects ‘from digital asset conception, creation, appraisal, description, and preservation, to accessibility, reuse, and beyond.’Footnote2 Environmental stewardship, the protection, care and responsible use of the environment,Footnote3 has resonance with the goal of preserving records of the river to improve its health and the impacts of flooding. The need to improve the human relationship with the river and acknowledge the impact of human activity in the wake of the floods inspired its creation.

The Anthropocene and climate change: flooding in the Northern Rivers

The Anthropocene is a geological epoch/period that recognizes the profound impact humans have had on the Earth’s systems and processes. Paul Crutzen used the term in 2002 to explain that we had entered a new epoch characterized by the impact of human activity on the Earth’s systems.Footnote4 While there is debate over whether it is an epoch or event, when it began or accelerated, it is widely acknowledged as a major transformative episode in Earth’s history.Footnote5 Human-caused climate change is linked in much of the literature with extreme weather events, including floods.Footnote6 It is important to acknowledge, however, that from the standpoint of the Bundjalung and Githabul peoples of the Northern Rivers, human activity cannot be generalized. The land and waterways of the Richmond Catchment and beyond, are the unceded territories of the peoples of the Bundjalung and Githabul Nations and they continue to speak and care for their country and water. The economic-political system that impacts the waterways and environment neither represents humanity nor the deep history of the region that brings light to alternative ways of living with the river.Footnote7 As Widjabul linguist Roy Gordon explains,

Just like the blood that runs through our veins, to keep us alive and sustain us through our daily lives, so is water important, not just for us as humans but for the environment we live in, the animals that we care for, and for the food that is provided to us. The main source of water for our people was the spring water. The people had a responsibility to care for that water. Water was shared with the animals. Water was shared by everyone. Water didn’t belong to anyone. Everyone was responsible for that water. There was, and there still is, a spirit of the waterhole. Be mindful. No-one can live without water.Footnote8

Lismore is built on a flood plain where two of the main tributaries of the Richmond River, the Wilsons River and Leycester Creek meet. Periodic flooding is part of the life of people in the Richmond River catchment and Widjabul Elder Gilbert Laurie explains the name for the Lismore area is Dundarimbah, which means swampland.Footnote9 This suggests a very different conception of the floodplain than the idea that water would be confined to a river bed. Nevertheless, flooding played a vital role in settler economies, albeit less concerned with regeneration. Flooding along the river stimulated colonization of the region. Settlers used floods to float the logs they were harvesting from the sub-tropical rainforest, and the river system supported fisheries, oyster farming, agriculture and the expansion of trade from those industries through shipping. As the settler colony grew, floods became more of a costly disaster. On the one hand, they are a natural phenomenon in the landscape; on the other, settlement, erosion, water and soil contamination, siltation and groundwater pollution contribute to the devastation. La Niña years increase the chance of rain, and in those years Lismore experienced more major floods in clusters:

Between 1887 and 1893, the town experienced three major floods, ranging between 10.43 and 12.46 metres. Between 1962 and 1965, the town endured three more floods over 10 metres. And in 1967, Lismore flooded five times between March and June, with floods ranging from 5.09 to 10.27 metres.Footnote10

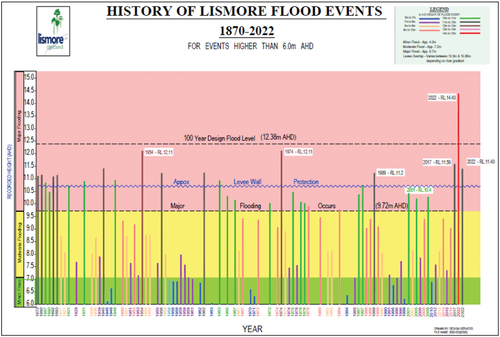

shows the history of Lismore flood events between 1870–2022. Lismore’s 1-in-100-year design level was a benchmark used by the Council to show how flood event levels relate to individual properties. The terminology was confusing, however, and has been replaced with the annual exceedance probability of 1 per cent, 1 per cent in any single year. The chance of experiencing a similar flood is still 1 per cent the following year (not that the height will be exceeded every 100 years as commonly thought).Footnote11 Note the height of the 2022 flood and the levee built in 2005 to protect the Central Business District (CBD). The levee overtops between 10.3 and 10.95 metres. Twenty floods have exceeded that height since 1870, six since the turn of the century.

Figure 1. Lismore flood events 1870–2022 Lismore City Council (Citation2023) https://www.lismore.nsw.gov.au/Community/Emergencies-disasters/Flood-information#section-2.

In February 2022, the flood peaked at 14.4 metres, two metres higher than the record set in 1954 of 12.27 metres. One month later, a second flood hit at 11.4 metres. The last major flood (one-in-a-hundred-year) was five years earlier, peaking at 11.9 metres. The frequency and intensity of extreme weather events like flooding have been attributed to human-induced climate change, and climate scientists have described the 2022 floods as ‘One of the most extreme disasters in colonial Australian history.’Footnote12 Anthropogenic influence is not the cause of flooding in Lismore but is recognized as contributing to its severity. As Senior Hydrologist with Australia’s science agency CSIRO, Dr Francis Chiew explains

Our climate and streamflow are highly variable, with many different drivers of this variability including the El Niño and La Niña cycle. The effects of climate change will be superimposed on this natural variability. We can attribute the contribution of climate change on some extreme events with confidence, including the role in heat extremes on land and in the ocean … We know that under a warmer climate, flood risk in general is likely to increase.Footnote13

Understanding the impact of global climate change at a regional level may make it more relevant to everyday experience and encourage change and political action.Footnote14 The imperative here is to explore archiving in the Anthropocene, how to (re)conceptualize history, which grew out of a humanistic tradition, and consider the records and archives we need to preserve and understand in the context of environmental change. Focusing on a region impacted by global climate change highlights the threats to heritage and how it might be a resource for dealing with accelerating climate change. The roots of ecological change can be traced to complex interconnecting ecological, political, economic and social issues. This offers the potential for archives to have a transformative and productive role, as Almeida and Hoyer remind us, without ‘overgeneralising’ socio-political drivers and human consequences.Footnote15 They introduce the ‘living archive,’ redefining the archive in relationship to lived community practice: a participatory, place-based framework to confront a new ecological reality.Footnote16

A particular case for historical records

In their call for historians to engage with climate change adaptation, Adamson, Hannaford and Rohland argue for particularizing adaptation – ‘this is the development of long-term empirical studies that uncover societal relations to climate in a particular place — including climate’s cultural dimensions.’Footnote17 Vulnerable communities experience flooding or bushfires but not global climate changes; moreover, their experience is shaped by individual and local circumstances and the past. As the Working Group to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change also explain, adaptation is place- and context-specific, with no single approach for reducing risks appropriate across all settings.Footnote18 Institutional documents have been found to be productive for reconstructing a chronology of climate disasters, studying the effects of these disasters and assessing the efficacy of adaptive strategies and policies on the local community.Footnote19 By focusing on the Richmond River, we hope to understand better the relationship between the physical environment and local social conditions, how their interaction is inscribed in the archives, and the continued presence and value of Indigenous Knowledge.

The Richmond River Historical Society is a volunteer-managed and staffed local history organization and repository for historical records located in the CBD in Lismore. Although named for the Richmond River, the Historical Society manages records related to the region rather than specifically focusing on the river itself. The research archives, however, include an extensive collection related to flooding. Records from local newspapers, family files, personal diaries, and photographs record the history and experience of flooding. Their archives include subject files on the 1870, 1880s, 1930s, 1940s, 1950s, 1960s, 1972, 1974, 1975 and 1996 floods, as well as records of flood mitigation and control, flood rescue, the Lismore Levee and the Tuckean Swamp drainage. Historical records of the district and River are primarily available on-site, mainly in paper and analogue formats.

Flood waters reached 30 centimetres below the ceiling on the ground floor of the Historical Society Lismore Museum and research room in 2022, but it was the mould that colonized the space once the waters had receded that prompted the removal and relocation of materials to shipping containers, where they still sit two years later. Increased temperatures, precipitation and humidity are known to impact collections and archives, which temperature-controlled facilities in better resourced repositories would address. Climate change is expected to accelerate the impact of these natural processes, and extreme events, like major flooding, will have new impacts.Footnote20 Intense rainfall events and flooding, such as Lismore experienced in 2022, have the potential to destroy collections and damage the historic buildings that house them. The lessons of the flood exposing the limitations of local infrastructure to preserve local archives can be applied more broadly. Extreme weather events disproportionately impact regional Australia compared to its cities.

The Richmond River has been the subject of numerous studies, however, no central repository exists for records, reports, surveys and historical material related to the Richmond River and its catchment. Some significant work may have already disappeared (for example, earlier flood inquiries, the complete documents for the Lismore Levee Environmental Impact Statement, and a range of important other ‘grey’ literature). The catchment covers five different local government areas. Relevant policies, agencies, roles and responsibilities are divided between Commonwealth, Local and State governments, and the majority of the central and southern areas of the catchment are in private ownership, while the northern part of the catchment has a large area of crown land and national parks. Typically, these organizations do not collaborate or share their resources. This has led to data and research gaps, duplication of research and inquiries, different conclusions, and divergent recommendations. Indigenous Land Use Agreements and Native Title are also recognized in some parts of the Catchment. Management of the river and its catchment is complicated by conflicting social, economic and environmental pressures.

Rivers do not observe the boundaries of Local Government Areas nor the states and territories that each have their own versions of a public records act that provides standards for record management and public access. Numerous data sets on rivers, creeks, streams, and catchments exist in Australia, but they are not well integrated. In addition, the organizational structure of governing bodies and their names change, which can also hinder access and research. Multiple agencies and stakeholders with diverse funding sources impede catchment management and produce multifarious reports and data. The Richmond River Estuary Coastal Management Program Scoping Study in 2023 cites ineffective governance and administration as a factor in making the task of improving the health of the Richmond River estuary so substantial and complex.Footnote21 The need for a whole-of-catchment approach to governance is continually raised to improve the health of the catchment and its waterways. The risk assessment also identifies damage to cultural heritage and sites caused by extreme weather events as a high threat, including floods and bushfires and acknowledges that there is limited understanding of the Richmond River’s cultural value and stories. The importance of protecting cultural heritage and engaging with the community are critical factors in the effort to coordinate a whole-of-catchment approach that includes Bundjalung and Githabul custodians. As Thom, Hudson and Dean-Jones explain,

Planning and implementation of management strategies in estuaries must not just recognise the dynamic nature of estuaries, but how changes in social and economic conditions interact with the diversity of driving forces from within catchments and the sea to maintain and improve environmental conditions.Footnote22

The Richmond River has been influenced by human activity for thousands of years, but particularly since European settlement, dating from the 1840s. Changes in land use, governance, flood mitigation and drainage activities have all impacted the health of the river, which is one of the most degraded river systems in New South Wales,Footnote23 highlighting the importance of understanding social and economic forces. The Richmond River Valley Flood Mitigation Committee reports to the New South Wales Government show an understanding of the state of the catchment as early as the 1950s and the relationship of land use to flooding:

Probably floods have always occurred in the Richmond River Valley. It is apparent, however, that the original state of stability that existed, with the vegetation providing an effective protection to the soil against erosion and also slowing down runoff sufficiently to permit maximum percolation into the soil, has been seriously upset … It has been shown that many landholders adopt land use measures that are conducive to excess runoff and erosion. In doing this, however, they are merely continuing practices that have been widely adopted since the early days of land settlement.Footnote24

Education was advocated to improve land use practices, but as the report demonstrates, change is constrained by social, economic and cultural factors related to history. Access to the numerous flood plain and flood management studies, reports and assessments, however, as well as the experiences of people documented through historical records, is impeded by administration and governance and lack of recognition of the importance of history and value of the humanities to climate change research. National programmes in the United States have acknowledged the importance of estuary health to the economy and environment through collaborations between local, state and federal bodies, which extend their governance approach beyond water quality to economic, recreational and aesthetic values.Footnote25 We understand that social change shapes environmental conditions which inform social change. Therefore, social and ecological records are as important to future planning as governance models.

Given the long history of flooding in the catchment, historical records cannot be limited to the documents available through state institutions. Archives both manifest and reinforce the privileging of the written record, undermining the value of oral histories and representing only a partial account of change over time.Footnote26 As Bundjalung man Oliver Costello reminds us in his submission to the 2022 Flood Inquiry:

Water Stories can teach us about Country … These stories can teach people lessons about our relationship to Country and how our practices can improve our wellbeing or result in suffering if we are not following the Lores of Country. We need old and new stories about learning from Country and restoring our Country through healing and regenerating the lands and waterways.Footnote27

Bundjalung and Githabul knowledge holders have communicated vast changes in the landscape and river system over the last 200 years and ways to care for it. Local knowledge offers cultural and practical information about approaches to land and water management.

Local knowledge and perspectives were also highly valued by the community surveyed about their experience of the 2022 floods and provided necessary information about potential risk and preparedness.Footnote28 Community safety and recovery are strengthened by an understanding of the lived experience of people subject to flooding. Sharing oral histories and experiences increases community awareness and provides vital local knowledge.Footnote29 Extreme climate events though can exacerbate pre-existing economic, social and environmental vulnerabilities. Research from the 2017 flood showed that 82 per cent of people affected were living in the lowest socio-economic neighbourhoods.Footnote30 The processes for applying for financial support relied on access to information and paperwork that was often unavailable, destroyed in the flood. The most vulnerable people lost their historical records, precious possessions and personal history.

I was there and it was hard, but you couldn’t be everywhere at once; there were 14 people throwing your stuff out windows onto the ground … Between the day of the flood … now I’m going to cry – between the day of the flood [and the day things were removed] you just kept going. But that day, I must admit I lost it. Watching your kids’ photos and everything you owned crushed up by an excavator and chucked in a truck, that was pretty heart breaking. It’s the memories, it’s the sentimental stuff – it’s not the fridges or the lounge or things like that. It’s those things [NSW055].Footnote31

Historical records play a role in individual preparedness, but they can also be resources to facilitate community recovery and knowledge of flooding. The case for preserving these records is the subject of the next section, situating archives in places and ways that are accessible for both individuals and communities, as well as improving the health of the river system.

Archival practice and climate change

Archives can play a crucial role in the context of the Anthropocene in preserving records that document the impact of human activities on the environment. Environmental data is vital for understanding the long-term effects of human activities to inform environmental policies and conservation efforts to preserve endangered species and ecosystems. Understanding the impact of environmental change on people also provides insight and inspiration for cultural change. This includes recording Indigenous knowledge, cultural practices, like Indigenous land management, and the impact of environmental change on communities. Moving beyond the idea of the archive as an institution, archiving as a practice could support climate adaptation and sustain more-than-human worlds.Footnote32 Eira Tansey has argued for ‘A Green New Deal for Archives:’

As the world moves toward a future that looks increasingly uncertain, frightening, and chaotic because of the impacts of climate change, preservation of the historical record is essential both for continuity of cultural memory and civil society, and for documentation of the ongoing permanent alteration of natural and human environments.Footnote33

The three foundational priorities Tansey outlines include increasing permanent staffing, creating a nationwide plan for collection continuity and emergency response and developing climate change documentation projects organized by watersheds, aligning with the motivation for the repository, framed by the Richmond River catchment. The need for professionally created, managed and preserved records to ensure continuity of operations following a disaster has also been raised by Gordon-Clark.Footnote34 Blue Shield Australia is part of a network committed to protecting cultural heritage that provides valuable resources and education around disaster risk reduction. Still, existing local resources are limited, and the professional expertise needed for preservation and conservation is also lacking. Bearing in mind that archives on and about the Richmond River face the immediate and long-term risk of flooding, inadequate staffing and facilities, what role could archival practice play in climate adaptation?

Understanding local risks and raising awareness of what to do in a disaster has been the primary function of disaster archives. Supporting recovery and community resilience is another function archival collections perform. The Japan Disaster Archive, established in the wake of the Great East Japan Earthquake in 2011, had an educational role in contributing to knowledge about particular localities and heightening risk awareness.Footnote35 Disaster archives include personal testimony that can create empathy and promote resilience through individual stories and responses. The Iwate Nippo Newspaper worked with Hidenori Watanave Laboratory in Tokyo to create a digital archive of those who lost their lives in the earthquake. The names of each victim of the disaster are recorded in the Wasurenai ‘We Shall Never Forget’ project. Their attempts to evacuate are visually represented to try and prevent future loss of life and give victims a voice in the Tendenko-Mirai-E series (A Future Where You Look Out For Yourself). The Indian Ocean Tsunami Archives were similarly established to record the events of the 2004 December tsunami, the disaster response and rehabilitation and reconstruction. The archives are located in countries impacted by the tsunami, Indonesia, India, Malaysia, Sri Lanka and Thailand, and were added to UNESCO’s Memory of the World register in 2017. Memories of the disaster and photographic images are published, as well as the recovery. The Indian Ocean Tsunami Archives are intended as a ‘collective memory’ of the disaster, which created a spirit of ‘unity, solidarity, and humanity among the nations in the world [representing] fortitude, strength, and fighting spirit of people and nations.’Footnote36 In this sense, the archives are intended to build resilience as well as preserve memory. Findings from a study of the Japan Disaster Archive suggest that archives can contribute to disaster education and provide an important learning experience about disaster effected areas, risks and recovery.Footnote37 These international examples place archives within the affected communities to support rebuilding, recovery and resilience in situ.

It is clear from the survey of community experiences of the 2022 floods that different communities have different adaptive capacities because of pre-existing and varied physical, social and economic contexts. Risks are also compounded by a lack of information or experience.Footnote38 Disasters can exacerbate existing vulnerabilities, and the impact of the floods followed the lines of disadvantage in the region, rendering most vulnerable those least able to protect and preserve their possessions, stories and memories, adding weight to the value of records, recovery and restitution, in the context of climate justice. As Thom, Hudson and Dean-Jones explain, ‘[r]isks are increased in communities which do not have existing capacity to predict, communicate, work together, make decisions and respond.’Footnote39 Storytelling is a powerful tool for building connections, disaster preparedness and harnessing local knowledge.Footnote40

The disaster in the Northern Rivers marked a tipping point in community consciousness around the changing climate and the reliability of public institutions with large-scale climate refugees and unprecedented damage to property and industry, all generating significant levels of trauma across all demographics in flood-impacted communities. Some residents had already been impacted by the 2019/20 bushfires, and the February 2022 flood was followed by another major flood one month later while people were still cleaning up. More than half of the respondents in the community survey felt that climate change had contributed ‘a great deal’ or ‘a lot’ to the level of flooding they experienced and that this would accelerate in the future.Footnote41 Addressing the issue of climate change and adaptation has implications for policy and local planning but also reinforces the need to understand human impact on the environment. Ultimately, addressing climate change will reduce disaster risk, but knowledge is a crucial driver in achieving change and building resilience. What do historical records contribute to our understanding of the floodplain, the impact of land use and infrastructure on the river?

Richmond River open access repository

The collective impact of European settlement on the Richmond River contributed to the scale of the disaster in 2022. In the wake of the flood, Richmond Riverkeeper was formed to advocate for the river and give it a voice in the flood enquiry that followed. The submission explained the human impact of settlement on the health of the river.

Dramatic changes in land use have occurred across this catchment over the past 250 years since European settlement, with the historic clearing of the catchment, drainage, and unsustainable land management practices leading to high levels of soil erosion, turbidity, the exacerbation of acid sulphate soils and blackwater events leading to fish kills (ABER, 2007; Hydrosphere Consulting, Citation2011a). Concentrated urban development around the catchments towns and centres, has led to an increase in hard surfaces, increased storm runoff, industrialisation of the floodplain providing numerous sources of pollution even in dry times (ABER 2007; Hydrosphere Consulting, Citation2011a). As a result, the Richmond Catchment is known to be one of the most highly ecologically stressed catchments in NSW with extremely poor ecosystem health (Ryder et al., 2015).Footnote42

Flood mitigation works and wetland drainage contributed to the intensity, timing and location of floods. Recommendations from the submission included the need for riparian restoration, bush regeneration and the restoration of floodplain wetland ecosystems to mitigate against future flooding rather than engineering solutions like dams and raising the levee constructed to protect the business district, which would not protect the region against the more frequent and more severe flooding expected as a result of climate change.Footnote43

Community archives are often created in response to the absence of accessible records in public institutions and to manage, store and preserve records of historical, scientific or cultural value that are not required to be kept through legislation or focused on public office. The repository is inclusive of those records, but centred on a physical location, in which multiple perspectives, different and inequitable experiences and voices, alliances and divisions require a more diverse and multidisciplinary approach than offered by state institutions. The river itself, with its soils, sediments, flow, ecology, and habitats, has been shaped over millions of years and is itself an archive, read in very different ways over time, reflecting different perspectives and relationships. Belinda Battley has described the importance of place in community recordkeeping processes, and we are similarly motivated by its significance.Footnote44 Bringing together records situated in state libraries and archives hundreds of miles away for access to the people who live in the Northern Rivers and creating oral histories to bring new perspectives to the community became a collaborative effort. A partnership between Southern Cross University (SCU) and Richmond Riverkeeper emerged from the need to address the poor state of the catchment and to site records and archives within the community most affected by climate change flooding events. The community itself has a long history of environmental activism and community-led action. In the massive flood event, it was the effort of volunteers that came to be known as the ‘tinny army,’ which rescued hundreds of people and saved countless lives. One of the authors is a founding member of Richmond Riverkeeper and the repository and our research is also driven by the state of the catchment and community access to information to support addressing that. Since the devastating floods of 1954, the river system has been the subject of numerous investigations and floodplain management strategies, often duplicated. Oral histories and historical documents provide earlier records. The connection between these and river health and riparian zones, river use and its value to people and flood recovery has been obstructed by the dispersal and loss of vital information and records. In the aftermath of the 2022 floods, Southern Cross University provided seed funding to create an online open-access repository for records related to the river through a small internal grants scheme focused on recovery and resilience. The purpose of the Richmond River Open Access Repository (RROAR) is to create a set of digital resources that can be used to:

Enrich knowledge, understanding and experience of the history of the Richmond River and its catchment

Facilitate research that will be responsive to data gaps and bridge divergent positions based on more restricted or constrained data collections

Promote research published on the Richmond River

Provide access to documents that can assist decision-making about the Richmond River

Be accessible to a diverse range of stakeholders

Advance efforts to improve river health. Footnote45

The geographic location of the catchment defines the repository’s scope with a focus on scientific, cultural, and historical records, including information about land use activities that impact water quality and water management, water storage and use, restoration and rehabilitation, and the relationship between people and the river in creation stories, agricultural use, urban development and leisure activities. The collection will include audio and video recordings, artistic works, reports, research papers, maps and media focusing on the river and its tributaries and catchment, produced up to the present time. As a regional university embedded within its community, SCU has a mission closely tied to the location and the needs and aspirations of the local community and, as such, is uniquely positioned to take on the role of archival and record-keeping for the river. Stewardship extends to the acknowledgement of the environmental impact of information and communication technologies and the need for sustainable practices in building a repository that does not negatively impact the health of the river catchment. As the campus library derives its electricity entirely from solar panels installed on the building’s roof, activities related to the creation, digitization and maintenance of the RROAR are powered by sustainable and renewable energy. Items of enduring value to the community not already accessible online are prioritized for long-term preservation.

Regional archives are both threatened by the escalation of climate events, and they help us understand them. The scope of the RROAR has been defined as a digital archive in which the relationship to materials is one of mutually responsive caregiving through the digitization of records, rather than a formal legal transfer of custody of the physical objects.Footnote46 Rather, a post-custodial approach is taken, returning physical items to maintain connectivity with the community, respecting their recordkeeping practices rather than removing them from the places of their creation or use.Footnote47 A decolonizing approach, as Evans et al. maintain, includes addressing questions of how archives can be maintained within communities and under community control.Footnote48 Following the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Protocols for Libraries, Archives and Information Services, the Repository will only accept items by or about Bundjalung and Githabul people in consultation with the community, and communities may exercise a Right of Reply to enhance, correct, update, critique or withdraw items in the collection.Footnote49

The repository includes digital representations of physical items and born-digital items in written and audio-visual formats. The RROAR comes under the auspices of the university’s Library as an emerging collection of significance for the university’s community and regional engagement strategic priorities, with ongoing staff resourcing absorbed into the Library’s operations. Governance of the repository was established through introducing and implementing the Library Archives Procedure, and donation and digitization agreement forms were developed, reviewed and approved by the University’s Legal office.

Establishing the RROAR began by contracting an archivist consultant to provide training and a project implementation plan for SCU’s Library staff. As Library staff were already expert in metadata description, collection policies, cultural heritage issues and copyright, training focused on digitization standards for capture and preservation, and donation processes. Members of the Richmond River Historical Society, Rous Council and the Richmond-Tweed Regional Library, who each have significant written archives about the catchment, were invited to attend a session with the archivist consultant who facilitated a conversation about opportunities to build the repository in partnership with community stakeholders. Consultation with colleagues in Gnibi College of Indigenous Australian Peoples and Bundjalung cultural advisors about the development of the repository, protocols and collections helped inform the procedures. As a community resource, the repository needs to evolve and function for creators and users, identities that are not mutually exclusive in a regional community that has been shaped by the river itself.

Metadata standards were adopted to meet the Australian Government Recordkeeping Metadata StandardsFootnote50 at the collection and item level. The process of populating the online repository with accessible historical and scientific research data commenced in mid-2023, starting with items already held within SCU’s Library collections, created or used by researchers of the catchment. The first items added included existing digitized copies of doctoral theses, journal articles and government reports. The first items to be approved for digitization included a wetlands inventory of the Richmond River catchment, a book of essays and art exhibition catalogues of works inspired by the river and flooding events.

Building the repository is expected to continue slowly and consistently and with an element of serendipity. It requires an ongoing commitment from University and community members to seek, evaluate, digitize and curate historical and contemporary data to help researchers, government agencies, historians, local organizations and individuals understand how to manage the catchment and restore its health. Community members and organizations have been invited to contribute items to the repository which can be digitized for preservation and access, including historical and contemporary reports, research papers, maps, video and audio recordings and other media focusing on the river, its tributaries and catchment, produced up to the present time. As relevant items are identified in the University’s collections, staff proactively seek out the authors, creators or copyright holders to request digitization permissions.

Ongoing community liaison will be required to attract donations to the repository beyond the items already physically located at the University and to ensure their relevance. Appraisal is a shared process, working with riverkeepers, researchers, and community organizations actively engaged with the river to identify materials and determine whether they have permanent value, building mutual knowledge and experience. The initiative and the scope of the repository were community-driven so we could avoid an existing institutional appraisal process we had to conform to, which had been an obstacle leading to the development of documentation strategies.Footnote51 An oral history project has been initiated to record the values and experiences people hold about the river which can be shared. As it matures, the RROAR will become an important resource to strengthen climate adaptation, facilitating improved access to floodplain management studies, government reports, maps, oral histories and historical narratives, consolidating sources about the health of the river and riparian zones, river use, its value to people, and flood recovery in one central repository. Working together, SCU staff, Richmond Riverkeeper and other community partners are building a repository of digital information accessible for research, disaster planning, land and water use and recovery in the community affected by water-related climate change.

Disaster risk reduction includes understanding risk, including the environment, and enhancing the social and cultural resilience of people, communities, countries and their assets.Footnote52 The numerous inquiries and reports following floods and water quality monitoring programmes are valuable resources in understanding the human-more-than-human relationship and climate adaptation. Still, these are neither easily accessed nor their recommendations fully implemented.Footnote53 However, studying and examining historic adaptations to flooding can help inform contemporary responses to building resilient and sustainable communities, as has been done in the coastal and river areas of Majuli Island in India, where people have been living with and adapting to changing water levels and annual flooding events for centuries.Footnote54 The guiding principles of the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015–2030 include cultural assets and heritage and the goal ‘to protect or support the protection of cultural and collecting institutions and other sites of historical, cultural heritage and religious interest.’Footnote55 Establishing the Richmond River Open Access Repository supports Principle 4 of the Sendai Framework to build back better in recovery, rehabilitation and reconstruction by making historical and scientific information about the catchment accessible to the community most affected by flood and climate change events. While cultural heritage is often absent from climate change discussions, Neal suggests that preserving heritage is necessary to build resilience, maintain community identity and strengthen social safety nets.Footnote56 The RROAR represents an opportunity to co-develop a scalable and sustainable archive with the community most affected by climate change, sharing the research and knowledge of past flooding events to help prevent, mitigate and recover from future disasters.

Conclusion

Increasing attention to stewardship in policies and initiatives has arisen from the importance of improving human relationships and interaction with the environment and the urgency of responding to climate change. The unique role of Bundjalung and Githabul peoples as stewards of the environment, sustainably managing and caring for Country, highlights that this concept, while evolving out of the environmental community, is not new, and there is much to learn from sharing knowledges. Insights about flooding and the factors that underpin the degradation of the Richmond River provide pathways to improve its health and strategies for climate adaptation. This necessitates attention to the historical, cultural and scientific records across multiple agencies and platforms and making these accessible into the future. If stewardship is about caring for something that is valued, this can be extended to the curation of archives and records about the Richmond River to promote understanding. While the global scale of climate change and the inevitability of extreme weather events might suggest change is remote, access to the records of the river provides information and insights that might guide a more sustainable relationship into the future.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Adele Wessell

Adele Wessell is an Associate Professor of History at Southern Cross University and founding member of Richmond Riverkeeper, an organization that grew out of the 2022 floods to give the rivers of the catchment a community voice and address its health. Adele lives in Lismore, New South Wales, a town built on a floodplain on the lands of the Widjabul Wia-bal people of the Bundjalung Nation. She is Merewether Fellow 2024, State Library of NSW, writing a history of the Richmond River.

Clare Thorpe

Clare Thorpe is the Director, Library Services at Southern Cross University, where she is committed to empowering communities to thrive by connecting them to people and information. Clare is based at the University’s Gold Coast campus on the saltwater country of the Yugambeh people.

Notes

1. Wulf, “Critical Archives,” para 7.

2. McCurry, “Digital Stewardship,” para 2.

3. Bennett, “Environmental Stewardship.”

4. Zalasiewicz, “Living in the Anthropocene,” 4.

5. Gibbard, “Anthropocene as an Event.”

6. Osaka, “Weather in the Anthropocene.”

7. See Salih, “Displacing the Anthropocene.”

8. Rous County Council, “Info Sheet 01,” 1.

9. Marciniak, “Curious North Coast.”

10. Cook, “Why can Floods,” para 16–18.

11. Lismore City Council, Flood Planning.

12. King, “Most Extreme Disasters.”

13. CSIRO, “Flood Risks,” para 1–2.

14. Osaka, “Weather in the Anthropocene.”

15. Almeida, “The Living Archive,” 10.

16. Ibid., 3.

17. Adamson, “Re-thinking the Present,” 195.

18. Cited in Ibid., 199.

19. Ray, “Assessing the Impacts.”

20. Climate Change and Cultural Heritage Working Group International, Future of our Pasts, 16.

21. Hydrosphere Consulting, Estuary Coastal Management Program, 3.

22. Thom, “Estuary Contexts and Governance,” 1.

23. New South Wales Department of Planning and Environment, “Health of Our Estuaries.”

24. Richmond River Valley Flood Mitigation Committee, Report Richmond River Valley.

25. Thom, ”Estuary Contexts and Governance,” 2.

26. Wareham, “From Explorers to Evangelists,” 187–207; and Drake, “Diversity’s Discontents,” 270–279.

27. Costello, “Buubaan butherun (Flood Stories),” 160.

28. Taylor, Community Experiences, 38–39.

29. Gerster, “Disaster Digital Archives.”

30. Rolfe, “Social Vulnerability,” 645.

31. Taylor, Community Experiences, 3.

32. Roberto Bernardes de Souza Júnior, “More-Than-Human”

33. Tansey, Green New Deal, 1.

34. Gordon-Clark, “Paradise Lost?” 52.

35. Gerster, “Disaster Digital Archives.”

36. UNESCO, Nomination Form, 2.

37. Gerster, “Disaster Digital Archives.”

38. Taylor, Community Experiences, 4–5.

39. Thom, “Estuary Contexts and Governance,” 12.

40. Sundin, “Rethinking Communication.”

41. Taylor, Community Experiences, p. 33.

42. Richmond Riverkeeper, Flood Inquiry Submission 1061, 1.

43. Vanclay, “Time to Come Clean,” para 9.

44. Battley, “Archives as Places, Places as Archives,” 1–26.

45. Southern Cross University. “RROAR Scope.”

46. Caswell, “Affective Bonds,” 25.

47. Battley, “Authenticity in Places,” 69.

48. Evans et al., “Indigenous archiving and wellbeing,” 138.

49. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Library, Information and Resource Network, “ATSILIRN Protocols;” Southern Cross University, “Library Archives Procedure;” Indigenous Archives Collective, “Position Statement.”

50. National Archives of Australia, Recordkeeping Metadata Standard.

51. Samuels, “Who Controls the Past,” 120.

52. United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction, The Sendai Framework, 18.

53. Cf Hydrosphere Consulting, Coastal Zone Management Plan; Ecos Environmental Consulting, Wilsons River Catchment Management.

54. Daly, “Cultural Heritage,” para 11.

55. United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction, Sendai Framework, 19.

56. Neal, “Cultural Heritage Necessary Component.”

Bibliography

- Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Library, Information and Resource Network Inc. “ATSILIRN Protocols for Libraries, Archives and Information Services.” Accessed November 26, 2023. https://atsilirn.aiatsis.gov.au/protocols.php.

- Adamson, G. C. D., M. J. Hannaford, and E. J. Rohland. “Re-Thinking the Present: The Role of a Historical Focus in Climate Change Adaptation Research.” Global Environmental Change 48 (2018): 195–205. doi:10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2017.12.003.

- Almeida, N., and J. Hoyer. “The Living Archive in the Anthropocene.” Journal of Critical Library and Information Studies 3, no. 1 (2020): 1–38. doi:10.24242/jclis.v3i1.96.

- Battley, B. “Archives As Places, Places As Archives: Doors to Privilege, Places of Connection or Haunted Sarcophagi of Crumbling Skeletons?” Archival Science 19, no. 1 (2019): 1–26. doi:10.1007/s10502-019-093000-4.

- Battley, B. “Authenticity in Places of Belonging: Community Collective Memory As a Complex, Adaptive Recordkeeping System.” Archives and Manuscripts 48, no. 1 (2020): 59–79. doi:10.1080/01576895.2019.1628649.

- Bennett, N. J., T. S. Whitty, E. Finkbeiner, J. Pittman, H. Bassett, S. Gelcich, and E. H. Allison. “Environmental Stewardship: A Conceptual Review and Analytical Framework.” Environmental Management 61, no. 4 (2018): 597–614. doi:10.1007/s00267-017-0993-2.

- Caswell, M. “Affective Bonds: What Community Archives Can Teach Mainstream Institutions.” In Community Archives, Community Spaces: Heritage, Memory and Identityedited by J. A. Bastian and A. Flinn 21–40.Facet: 2018. doi:10.29085/9781783303526.003

- Climate Change and Cultural Heritage Working Group International. The Future of Our Pasts: Engaging Cultural Heritage in Climate Action. Paris: International Council on Monuments and Sites, 2019.

- Cook, M. 2022 “Why Can Floods Like Those in the Northern Rivers Come in Clusters?” The Conversation. Accessed December 12, 2023. https://theconversation.com/why-can-floods-like-those-in-the-northern-rivers-come-in-clusters-180250.

- Costello, O. “Buubaan Butherun (Flood Stories).” In 2022 Flood Inquiry Volume Three: Appendices, edited by M. O’Kane and M. Fuller, 150–172. Sydney: Government of New South Wales, 2022.

- CSIRO. 2022. “Flood Risks Under Climate Change.” Accessed December 2, 2023. https://www.csiro.au/en/news/All/News/2022/March/Flood-risks-under-climate-change.

- Daly, C., J. Downes, and W. Megarry. 2018. “Cultural Heritage Has a Lot to Teach Us About Climate Change.” The Conversation. Accessed December 2, 2023. https://theconversation.com/cultural-heritage-has-a-lot-to-teach-us-about-climate-change-103266.

- Drake, J. M. “Diversity’s Discontents: In Search of an Archive of the Oppressed.” Archives and Manuscripts 47, no. 2 (2019): 270–279. doi:10.1080/01576895.2019.1570470.

- Ecos Environmental Consulting. Wilsons River Catchment Management Plan. Lismore: Rous Water, 2009.

- Evans, J., S. Faulkhead, K. Thorpe, K. Adams, L. Booker, and N. Timbery. “Indigenous Archiving and Wellbeing: Surviving, Thriving, Reconciling.” In Community Archives, Community Spaces: Heritage, Memory and Identityedited by J. A. Bastian and A. Flinn, 129–148. Facet: 2019. doi:10.29085/9781783303526.009

- Gerster, J., S. P. Boret, R. Morimoto, A. Gordon, and A. Shibayama. “The Potential of Disaster Digital Archives in Disaster Education: The Case of the Japan Disasters Digital Archive (JDA) and Its Geo-Location Functions.” International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction 77 (2002). doi:10.1016/j.ijdrr.2022.103085.

- Gibbard, P., M. Walker, A. Bauer, M. Edgeworth, L. Edwards, E. Ellis, S. Finney, et al. “The Anthropocene as an Event, Not an Epoch.” Journal of Quaternary Science 37, no. 3 (2022): 395–399. doi:10.1002/jqs.3416.

- Gordon-Clark, M. “Paradise Lost? Pacific Island Archives Threatened by Climate Change.” Archival Science 12, no. 1 (2012): 51–67. doi:10.1007/s10502-011-9144-3.

- Hydrosphere Consulting. Coastal Zone Management Plan for the Richmond River Estuary. Ballina: Hydrosphere Consulting, 2011.

- Hydrosphere Consulting. Richmond River Estuary Coastal Management Program – Protecting Our Estuary and Its Catchment. Stage 1: Scoping Study. Ballina: Hydrosphere Consulting, 2023.

- Indigenous Archives Collective. “Indigenous Archives Collective Position Statement on the Right of Reply to Indigenous Knowledges and Information Held in Archives.” Accessed January 5, 2024. https://indigenousarchives.net/indigenous-archives-collective-position-statement-on-the-right-of-reply-to-indigenous-knowledges-and-information-held-in-archives.

- King, A., L. Ashcroft, and S. Perkins-Kirkpatrick. 2022. “‘One of the Most Extreme Disasters in Colonial Australian History’: Climate Scientists on the Floods and Our Future Risk.” The Conversation. Accessed January 5, 2024. https://theconversation.com/one-of-the-most-extreme-disasters-in-colonial-australian-history-climate-scientists-on-the-floods-and-our-future-risk-178153.

- Lismore City Council. “History of Lismore Flood Events 1870-2022.” Accessed December 12, 2023. https://www.lismore.nsw.gov.au/Community/Emergencies-disasters/Flood-information#section-2.

- Marciniak, C. 2017. “Curious North Coast: Why Was Lismore Built on a Floodplain?” ABC News, Accessed January 5, 2024. https://www.abc.net.au/news/2017-12-13/curious-nc-lismore-built-on-a-floodplain/9252362.

- McCurry, J. 2014. “Digital Stewardship: The One with All the Definitions.” Folger Shakespeare Library Blog. Accessed December 5, 2023. https://www.folger.edu/blogs/collation/digital-stewardship-the-one-with-all-the-definitions/.

- National Archives of Australia. The Australian Government Recordkeeping Metadata Standard (AgrkMS) Version 2.2. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia, 2015.

- Neal, A. 2020. “Cultural Heritage Is a Necessary Component of Climate Solutions.” Environmental and Energy Study Institute. Accessed December 5, 2023. https://www.eesi.org/articles/view/cultural-heritage-is-a-necessary-component-of-climate-solutions.

- New South Wales Department of Planning and Environment, 2023. “Health of Our Estuaries: Richmond River.” Accessed November 30, 2023. https://www.environment.nsw.gov.au/topics/water/estuaries/estuaries-of-nsw/richmond-river.

- Osaka, S., and R. Bellamy. “Weather in the Anthropocene: Extreme Event Attribution and a Modelled Nature-Culture Divide.” Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 45, no. 4 (2020): 705–951. doi:10.1111/tran.12390.

- Ray, R., and A. Bhattacharya. “Assessing the Impacts of Climate Variability – a Study of Institutional Archival Data Spanning 1700-1947 (British Colonial Period) Pertaining to Semi-Arid Tracts of Peninsular India.” Paper Presented at the EGU General Assembly 2020, Online, May (2020). doi:10.5194/egusphere-egu2020-5350.

- Richmond Riverkeeper. 2022. NSW Flood Inquiry Submission 1061. New South Wales Government, Department of Premier and Cabinet, Accessed December 12, 2023. https://www.dpc.nsw.gov.au/assets/flood-inquiry-submissions/1061-Richmond-Riverkeeper-Association-20220520.pdf.

- Richmond River Valley Flood Mitigation Committee. Report of the Richmond River Valley Flood Mitigation Committee. New South Wales Department of Public Works, 1958.

- Roberto Bernardes de Souza Júnior, C. “More-Than-Human Cultural Geographies Towards Co-Dwelling on Earth.” Mercator (Fortaleza) 20, no. 1 (2021): 1–10.

- Rolfe, M. I., S. W. Pit, J. W. McKenzie, J. Longman, V. Matthews, R. Bailie, and G. G. Morgan. “Social Vulnerability in a High-Risk Flood-Affected Rural Region of NSW, Australia.” Natural Hazards 101, no. 3 (2020): 631–650. doi:10.1007/s11069-020-03887-z.

- Rous County Council. 2004. “Info Sheet 01 Rocky Creek Water Walks.” Accessed December 1, 2023. https://rous.nsw.gov.au/file.asp?g=RES-IYR-11-85-66.

- Salih, R., and O. Corry. “Displacing the Anthropocene: Colonisation, Extinction and the Unruliness of Nature in Palestine.” EPE: Nature and Space 51, no. 1 (2022): 381–400. doi:10.1177/2514848620982834.

- Samuels, H. W. “Who Controls the Past.” The American Archivist 49, no. 2 (1986): 109–124. doi:10.17723/aarc.49.2.t76m2130txw40746.

- Southern Cross University. “Library Archives Procedure.” 2023a. Accessed January 5, 2024. https://policies.scu.edu.au/document/view-current.php?id=450

- Southern Cross University. “RROAR Scope.” 2023b. Accessed January 5, 2024. https://www.scu.edu.au/library/about-us/special-collections/richmond-river-open-access-repository-rroar/rroar-scope/.

- Sundin, A., K. Andersson, and R. Watt. “Rethinking Communication: Integrating Storytelling for Increased Stakeholder Engagement in Environmental Evidence Synthesis.” Environmental Evidence 7, no. 6 (2018). doi:10.1186/s13750-018-0116-4.

- Tansey, E. A Green New Deal for Archives. Alexandria: Council on Library and Information Resources, 2023.

- Taylor, M., F. Miller, K. Johnston, A. Lane, B. Ryan, R. King, H. Narwal, M. Miller, D. Dabas, and H. Simon. Community Experiences of the January-July 2022 Floods in New South Wales and Queensland Final Report: Policy-Relevant Themes. Melbourne: Natural Hazards Research Australia, 2023.

- Thom, B., J. Hudson, and P. Dean-Jones. “Estuary Contexts and Governance Models in the New Climate Era, New South Wales, Australia.” Frontiers in Environmental Science 11 (2023). doi:10.3389/fenvs.2023.1127839.

- UNESCO, Nomination Form International Memory of the World Register, Indian Ocean Tsunami Archives, 2016. Accessed April 5, 2024. https://media.unesco.org/sites/default/files/webform/mow001/indonesiasrilanka_tsunami_en.pdf.

- United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction. The Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015-2030. Geneva: United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction, 2015.

- Vanclay, J. “It’s Time to Come Clean on Lismore’s Future. People and Businesses Have to Relocate Away from the Floodplains.” The Conversation (2022). Accessed December 4, 2023. https://theconversation.com/its-time-to-come-clean-on-lismores-future-people-and-businesses-have-to-relocate-away-from-the-floodplains-184636.

- Wareham, E. “From Explorers to Evangelists: Archivists, Recordkeeping, and Remembering in the Pacific Islands.” Archival Science 2, no. 3–4 (2002): 187–207. doi:10.1007/BF02435621.

- Wulf, K., and A. Strauss “Critical Archives.” The Scholarly Kitchen (2023). Accessed October 15, 2023. https://scholarlykitchen.sspnet.org/2023/08/24/critical-archives/.

- Zalasiewicz, J., M. Williams, A. Smith, T. L. Barry, A. L. Coe, P. R. Bown, P. Brenchley, et al. “Are We Now Living in the Anthropocene?” GSA Today: A Publication of the Geological Society of America 18, no. 2 (2008): 4–8. doi:10.1130/GSAT01802A.1.