ABSTRACT

This article explores the affective connotations and emotive implications of archiving in extraordinary times. It examines how ‘rapid response collecting,’ the practice of documenting crises, upheavals, and tragedies during their unfolding or in their immediate aftermath, is felt through an affect-centric examination of COVID-19 collecting in the UK archives sector. An anonymous, online survey of archivists involved in documenting the pandemic was conducted — the first empirical study of archives workers’ experiences of rapid response collecting — to assess emotional reactions and perceptions of wellbeing whilst undertaking rapid response collecting initiatives. Emergent themes surfaced by analysing the qualitative and quantitative data related to the idiosyncrasy of emotive potentiality, the influence of support and training in mitigating adverse psychological effects, and the current lack of fully embedded trauma-informed approaches in rapid response collecting efforts. Whilst acknowledging the particularities of COVID-19 collecting and the small scale of the study, this research indicates that educators, scholars, and professional bodies need to do more to prepare practitioners for the role emotions can play in rapid response collecting. It ultimately contends that a trauma-informed approach is essential if we are to protect the psychological safety of all in future rapid response collecting endeavours.

Introduction

When UK archives rushed into action in 2020 to ensure that experiences of life in the pandemic would be preserved for posterity, they were at least partially attuned to the deluge of emotions accompanying the ‘new normal.’ In their call-outs for material, they asked for records that described the public’s ‘hopes and fears,’Footnote1 their means of ‘coping with changes to daily life,’Footnote2 and the ways they were ‘making sense’ of these ‘unprecedented times.’Footnote3 In doing so, they were acknowledging heightened states of feeling. Moreover, however, they were imbuing the records, and the act of collecting itself, with affective signification.

Although perhaps unintentional, this attribution was pivotal: we cannot fully understand COVID-19 collecting without recognizing its emotive dimensions. Based on the results of a survey of archive professionals engaged with COVID-19 collecting, and building upon Anna Sexton’s notion of ‘traumatic potentiality,’Footnote4 this research indicates that, as a form of ‘rapid response collecting,’ COVID-19 collecting held the potential to trigger adverse and beneficial psychological responses. Whilst recent scholarship has indicated the existence of emotive potentiality in all archival work, this research shines new light on both the heightened role affect played in COVID-19 collecting, and the largely undiscussed presence of emotions in rapid response collecting more broadly.

Archival discourse on rapid response collecting, affect, ethics of care, and trauma-informed approaches

The development of archival discourse relating to rapid response collecting (hereafter abbreviated to ‘RRC’), the increasing acknowledgement of a relation between affect and archives, and the more recent turn towards trauma-informed approaches in archival literature, are traced here to contextualize the results of the survey on COVID-19 collecting.

Scholarship on RRC from its origins to 2019

RRC can be defined as the active collection of items and experiences in the immediate aftermath of (or, in the case of COVID-19 collecting, during) ‘moments of turmoil, transition and tragedy.’Footnote5 The practice arguably has its origins, as Kerrie M. Davies writes, in the 1960s and 1970s, when the American historian and curator Edith Mayo began collecting ephemera from that era’s ‘civil rights and second wave feminism movements.’Footnote6 However, it was not until the turn of the millennium and the emergence of two seminal RRC initiatives — the September 11 Digital Archive (2002), created after the 9/11 terrorist attacks, and the Hurricane Digital Memory Bank (2005), established in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina — that it gained a noticeable presence in the literature.

As the first serious introduction to the approach, the scholarship of the early 2000s discussed the physical, curatorial, and financial practicalities of RRC. Digital archiving was a particular focus: Tom Scheinfeldt, for instance, noted how digital RRC complicates appraisal, metadata, and donor relations because donors have increased autonomy to decide what to submit and how their records are described.Footnote7 Similar arguments relating to RRC’s ‘populist’ ethos, such as the contention that RRC archives can better represent ‘public’ memory because ‘official’ narratives are secondary to the voices of the populace,Footnote8 were considerably extended in the next decade. As many RRC initiatives in the 2010s were conducted during or immediately after social justice demonstrations (such as the 2017 Women’s March), this period’s literature contained the first acknowledgement of RRC’s often explicitly activist dimensions, recognizing the typically community-driven RRC of protests endeavours to produce collections that will both hold authorities accountable and inspire ‘future social activism.’Footnote9

Although much of this literature stressed (digital) RRC’s ‘participatory’ and ‘democratising’ nature,Footnote10 praise for RRC began to receive qualification during this period. Particularly notable was Documenting the Now’s 2018 white paper report highlighting the privacy and consent-related complexities of social media curation during justice movements,Footnote11 and Ana Milošević’s contention, in the context of the RRC of spontaneous memorials, that mourners may not want ‘their intimate thoughts … stored in an archive.’Footnote12 These novel ethical concerns culminated in the first tentative challenges to the notion of RRC as a professional ‘duty.’ In 2019, for example, the Society of American Archivists posited that there may be more suitable ways archives can ‘offer support in the aftermath of a tragedy.’Footnote13

Discourse on RRC from 2020 onwards

It was in 2020, however, when RRC was adopted on a global scale to document the pandemic and the Black Lives Matter protests that the practice truly entered the archival mainstream. Given that it was many archivists’ first foray into RRC, there was inevitably a return to practicalities in the literature on archiving Covid-19.Footnote14 Yet, broader tensions and questions were more attentively discussed, from RRC’s supposed capability to ensure a more diverse historical recordFootnote15 to our ‘duty’ to archive a momentous event for posterity. Although the latter was still a prominent argument,Footnote16 it was significantly undermined by an unprecedented degree of attention to RRC’s ethical implications: questions concerning documenting ‘both sides’ by archiving mis-/disinformation and the appropriateness of allocating resources and energy away from the frontline during a crisis are especially apparent.Footnote17

Archives, affect, ethics of care, and trauma

As part of the humanities’ ‘affective turn,’ scholars began to explore the connection between archives, affect, and emotions. By positioning records as ‘repositories of feelings,’ Ann Cvetkovich both advanced earlier contentions that defining records in purely evidentiary terms obscures intimate histories, and indicated the psychological power of records.Footnote18 Sara Ahmed enriched this affective reinterpretation by framing archives through the notion of contact: if our emotions ‘are shaped by, and even take the shape of, contact with others,’ and an archive is ‘an effect of multiple forms of contact,’ archives are more than settings for research, they are sites of emotive possibilities.Footnote19

Despite such groundbreaking work, it was arguably not until Marika Cifor’s seminal 2016 articleFootnote20 that affect gained serious academic purchase in archival science. In her article, Cifor defines affect as ‘a force that creates a relation between a body and the world.’Footnote21 ‘Affect,’ she contends, is what binds us to people and things and, as such, it ‘encompasses’ but also ‘reaches beyond feelings and emotions.’Footnote22 In line with this, we use affect in this article as the all-encompassing broader term, placing emotions as arising from affect. We do not specifically differentiate between emotions and feelings and have chosen emotion as our preferred term for representing the sensations we feel from affect. However, some scholarship makes a distinction between these two terms, with emotions referring to sensations in our bodies and feelings referring to how we interpret these sensations and give meaning to them.Footnote23

Since 2016, Cifor, Michelle Caswell, Anne J. Gilliland, and Jamie A. LeeFootnote24 (among others) have made considerable strides in elucidating the ability of records (and their absence) to affect the psyche.Footnote25 Recognizing the capacity of archives to hurt or, conversely, empower, has led these scholars to reframe professional expectations, advocating for archivists to become caregivers by adopting radical empathy and a feminist ethics of care.Footnote26 Notably, Caswell and Cifor describe how an approach to archiving infused with such an ‘ethics of care’ is a fundamentally relational approach, in which archivists act as caregivers in a ‘web of mutual affective responsibility’ with users, subjects, creators, and communities.Footnote27 Complementary scholarship that similarly foregrounds relational approaches has recently been extended to acknowledging the psychological impacts of archiving on archivists themselves. This is exemplified by Jennifer Douglas et al.’s pioneering research on how archiving can be grief work,Footnote28 and Cheryl Regehr et al.’s pivotal 2022 and 2023 studies that revealed ‘a wide range of emotional responses arising from archival work.’Footnote29

However, the relationship between archives and trauma is still largely peripheral in archival theory and praxis. The principal focus of the limited (but now steadily growing) trauma-centric scholarship has been records’ traumatic potentiality.Footnote30 The associated risk of vicarious trauma among archivists has been identified as a serious threat since Douglas, Katie Sloan, and Jennifer Vanderfluit’s 2019 survey of Canadian archivists revealed that 72 per cent of respondents had worked with records they deem traumatic.Footnote31 However, it was the results of Nicola Laurent’s and Wright 2023 international survey into archives and trauma that indicated the global prevalence of both ‘traumatic or distressing reaction[s]’ and archivists’ insufficient training for, and support in dealing with, emotional labour.Footnote32

0Such evidence has begun to prompt discussions surrounding the necessity of adopting trauma-informed practice in the sector. Although the most attentive trauma-informed training is offered by the Australian Society of Archivists,Footnote33 in the UK, the Archives and Records Association has published three ‘Emotional Support Guides’ for archivists working with potentially sensitive materials,Footnote34 recognizing that ‘secondary trauma is always a possibility for any member of staff.’Footnote35 Yet, traumatic considerations have only recently become more explicitly acknowledged in archival literature and education,Footnote36 as evidenced by the fact that only 8 per cent of respondents to Laurent and Wright’s survey reported that they were taught about trauma-related topics during their studies.Footnote37 This indicates that archivists who are established in the field have been inadequately prepared through their initial education/training for the role emotions can play in their professional lives.

Emotions and RRC: a problematisation

By viewing the practice specifically through an affective lens, James B. Gardner and Sarah M. Henry’s 2002 article on the RRC of the September 11 attacks was a crucial intervention in scholarly narratives of RRC.Footnote38 In the following decade, Kevin Smith, Carrie Jo Coaplen, and Gary Perry advanced affective considerations by contending that contributing to RRC projects can assist recovery from trauma, both through cathartic release and by helping to rebuild a sense of community.Footnote39 Pam Schwartz et al. combined these arguments with their own affective experiences of undertaking RRC of the 2016 mass shooting at the Orlando-based gay nightclub Pulse,Footnote40 and Stephanie Gibson and Shannon Blaymires foregrounded affect by arguing that RRC could become ‘vulture collecting’ if it unintentionally commodifies grief.Footnote41 However, even in this scholarship, emotions are typically only one topic among many, and explicit references to affect theory are almost absent, with Vera Mackie, Sharon Crozier-De Rosa, and Gina Watts’s writings on applying affect and radical empathy to the RRC of the Women’s March being virtually the only exceptions.Footnote42

Affective considerations featured slightly more prominently in the literature on COVID-19 collecting. As is the case with other scholarship on RRC, it is possible to trace threads though this literature relating to the fundamentally emotive meanings of the records for donors,Footnote43 and about the collecting’s ability to both provide a source of collective solidarityFootnote44 and evoke empathy.Footnote45 Yet, what is significant in the literature on COVID-19 collecting is the more prominent highlighting of the risk of adverse affective implications arising from this instantiation of RRC. Ferrin Evans and Eira Tansey, for instance, stressed how the combination of archivists’ ‘affective porosity’Footnote46 (as people connected to various actors’ pain) and the insufficient regard for emotions in the sector makes archiving during such affectively charged periods as pandemics potentially psychologically injurious.Footnote47 Numerous scholars and professional bodies raised concerns that RRC could cause more harm than good for donors/participants too. Oral histories were a particular point of anxiety in this regard because the sector’s widespread unfamiliarity with trauma-informed interviewing increased the risk of inadvertently causing distress or PTSD,Footnote48 especially as participants in COVID-19 oral histories had ‘not had the chance to reflect upon and integrate’ the traumas that they were ‘actively experiencing.’Footnote49

Despite the significance of this new vigour, affective considerations overwhelmingly continue to be sidelined in the literature on RRC. As the results of our survey will indicate though, it is only by combining existing discourses with emotion-centric interpretations that we can fully understand what it means to archive in extraordinary times.

Methodology

This research was conducted in fulfilment of the first author’s dissertation for the MA in Archives & Records Management at University College London (supervised by the second author). The research questions underpinning the dissertation were:

What factors influenced archivists’ affective engagement with COVID-19 collections?

To what extent did archives plan to mitigate the possible affective risks of COVID-19 collecting for staff, donors/participants, and future users?

How much of a role did affect play in COVID-19 collecting?

Would a trauma-informed approach be beneficial in future RRC projects?

To address these questions, an anonymous online survey was created for archives professionals who partook in COVID-19 collecting in 2020–2021, or had at any time worked with a COVID-19 collection (for example through cataloguing). COVID-19 collecting initiatives were defined in the survey as call-outs for physical and/or digital materials related to the pandemic. This included projects consisting solely of oral histories but excluded web archiving and wholly extra-institutional endeavours, due to the former’s comparative rarity and the less central position of the archivist in the latter.

The survey included both open- and closed-ended questions, the former enabling archivists to share their experiences in their own words and the latter ensuring that the survey would not be too overwhelming to complete (a concern given the focus on emotions). It comprised sixteen questions split into three sections. The first section focused on the archive’s reasoning for undertaking COVID-19 collecting and its (alongside the respondent’s) familiarity with RRC; the second related to the respondent’s affective engagement with COVID-19 materials and their workplace’s approach to (and their own views on) managing the potentially heightened emotions involved in RRC, and the last section concerned the principal challenges and benefits of undertaking COVID-19 collecting. Key terms such as RRC and ‘trauma-informed approaches’ were defined to reduce the likelihood of misunderstanding or misinterpretation hampering the survey results’ validity.

Voluntary response sampling, where participants self-select by choosing to partake in the research, and snowball sampling, whereby the researcher makes ‘initial contact with key informants who, in turn, point to information-rich cases,’Footnote50 were employed to disseminate the survey. The Archives-NRA listserv was the principal distribution outlet given its density of archives professionals and regular use, however the survey was also circulated on the Contemporary Collecting listserv, the Trauma-Informed Archives Community of Practice Discord channel, and Twitter. These methods yielded 32 responses.

The principal ethical concerns of this research related to its emphases on the potentially sensitive topics of COVID-19 and emotions. Therefore, alongside protecting respondents’ anonymity and making assent to an informed consent statement mandatory for the survey to be submitted, additional consideration was given to mitigating the risk of psychological distress. This entailed heavily emphasizing on the first page of the survey the sensitive foci of the research, as well as splitting the survey into multiple pages to enable further advisories to be added in subsequent sections. Respondents were also given the freedom to leave any questions unanswered and exit the survey at any point. However, consequential harm was also accounted for by embedding links to mental health resources within the survey.Footnote51

The first author conducted the analysis of the survey data. This was itself an emotional process, hence additional support from the first supervisor and regular breaks when conducting data analysis were important built-in safeguards. The open-ended questions in the survey were coded inductively and analyzed utilizing Anselm Strauss’s constant comparative analysis method.

Theoretical framework

Aligned with feminist epistemologies that value emotions, this research is particularly rooted in Alison Jaggar’s positioning of emotions as ‘helpful and even necessary rather than inimical to the construction of knowledge.’Footnote52 In contrast to positivist assertions that emotions hinder research by producing unreliable results, Jaggar contends that centring emotions can aid ‘critical research’ by enabling ‘us to perceive the world differently from its portrayal in conventional descriptions,’ thereby facilitating the destabilization of hegemonic paradigms.Footnote53 Similarly, our centring of affect is a deliberate undertaking to unlock novel understandings of the typically unspoken, personal meanings of RRC.

The research is therefore necessarily subjectivist, both conceptually and methodologically. It is also, specifically, interpretivist in nature: by centring emotions, the aim is to access ‘the complex world of lived experience from the point of view of those who live it,’Footnote54 adopting the ontological position of relativism by positing that ‘there is no single, tangible reality … only the complex, multiple realities of the individual.’Footnote55

Survey responses

Institutional type and level of experience in RRC

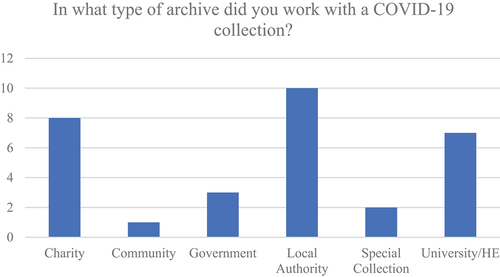

Respondents were asked to indicate their institution type as a means of contextualizing the survey results (see ). Three archive types predominated: local authority, charity, and university/higher education archives together constituted 80.64 per cent (n = 25) of responses, meaning government, special collection, and community archives comprised less than 20 per cent (n = 6). Indeed, there was only a single response from a community archive, which, whilst somewhat unexpected, was a likely finding due (at least in part) to the dissemination channels utilized for the survey.

Respondents next explained why their archive undertook COVID-19 collecting. Posterity was the primary reason, however 37.5 per cent (n = 12) asserted that it was undertaken to fulfil professional obligations. The traditional assertion of RRC as a ‘duty’ was voiced by two of these respondents, with one quoting the International Council on Archives’ statement that ‘the duty to document does not cease in a crisis.’Footnote56 More common though were comments stating that COVID-19 collecting aligned with the institution’s normal collecting remit, with two respondents even noting that RRC is ‘regularly’ undertaken as an ‘established practice.’

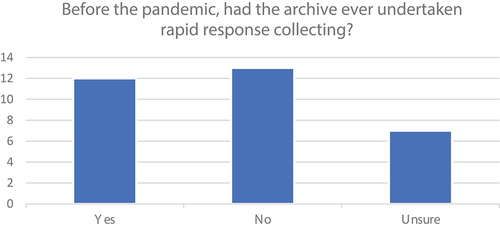

This indication that RRC is not completely far removed from standard practice was further demonstrated by responses to a question asking whether the archive had undertaken RRC prior to COVID-19 collecting: the number of ‘no’ responses (n = 13) only marginally eclipsed the ‘yes’ responses (n = 12) (see ).

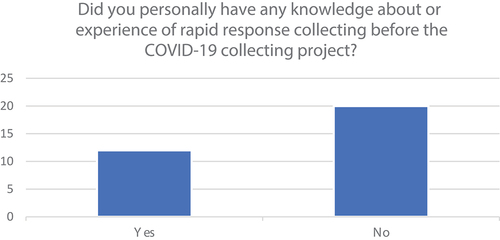

Yet, when respondents were asked whether they themselves had prior experience of or knowledge about RRC, we see that institutional familiarity did not equate to personal familiarity, with 62.5 per cent (n = 20) selecting ‘no’ and 37.5 per cent (n = 12) selecting ‘yes’ (see ).

Furthermore, open-ended answers relating to the ‘yes’ responses revealed that many of the respondents who claimed familiarity with RRC could only do so tenuously. Although 61.5 per cent (n = 8) of these respondents did reference direct RRC experience, 23 per cent (n = 3) of these respondents cited only knowledge, and others made inconclusive statements such as ‘I’d seen it happen.’

Emotional responses and mitigations

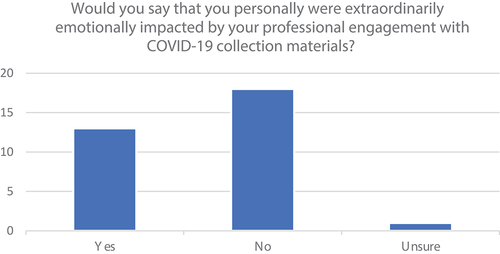

Respondents were asked whether they were extraordinarily emotionally affected by their engagement with COVID-19 collection materials. Whilst the majority 56.25 per cent (n = 18) answered ‘no,’ the fact that ‘yes’ responses constituted 40.63 per cent (n = 14) of the answers (see ) is significant in indicating the possible affective implications of the practice.

As Regehr et al. contend, many factors can influence ‘an individual’s susceptibility or resilience to distress when exposed to [potentially] traumatic stimuli in the workplace:’ the experience — the content itself and the form, length, and personal meaning of the interaction; the individual — any prior traumatic experiences, coping mechanisms, and support structure(s); and the workplace — ‘workload, organizational climate, social support and supervision.’Footnote57 Respondents were given the opportunity to expand upon their answers and coding here demonstrated that each of these factors shaped respondents’ emotive reactions.

Primarily, unusually intense negative emotions were attributed to ‘not having an “off” from Covid’ – ‘collecting, reading, processing and reflecting upon narratives whilst at the same time living through the pandemic was tough for everyone’ – and more strongly resonating with the records, with one respondent stating that ‘I had not really collected anything related to a theme that affected myself, particularly not at the same time while I was feeling the effects.’ This heightened intertwining of the personal and the professional is evident in the second most prevalent influence too: adverse lived experiences of and/or perspectives on the pandemic. The majority of these responses concerned lived experience, with a respondent noting, for example, that losing a parent to COVID-19 made the project ‘more emotional’ for them, however, one response related to emotional distress caused by their personal perspective that the pandemic had been politically mishandled.

12.5 per cent (n = 4) of respondents reported simultaneously positive and negative emotional experiences. For instance, one wrote that ‘it was very hard to hear when others had had much better experiences than me,’ but also noted both that their co-workers’ ‘similar experiences’ made it ‘easy enough to offload and decompress,’ and that there was ‘something therapeutic about doing these interviews.’ For two others, this multifaceted affective engagement related to them being, in Cifor’s words, witnesses to ‘the pain of others’Footnote58: the ‘more intense’ relationships with donors were ‘good and bad,’ and reading records elicited ‘empathetic feelings’ of both ‘solidarity’ and ‘frustration.’

Furthermore, other respondents noted mitigating factors. For some, mitigation was provided by the collecting’s ability to elicit a sense of purpose, encapsulated in the comment that ‘sometimes it was a solace knowing that what we were doing was important.’ It was peer and institutional support, however, that was identified as the most significant factor in mitigating harmful impacts. For instance, one respondent asserted that ‘the contemporary collecting group was really helpful in […] feeling less isolated in this type of work,’ and others wrote of measures such as ‘regular wellbeing check-ins’ and being allowed to limit ‘contact with material that was explicitly traumatic’ to minimize the risk of ‘vicarious trauma.’ The converse was true too: a respondent commented that relying on less frequent, virtual-only discussions with colleagues contributed to stronger adverse emotions, because it is co-workers’ support that ‘normally diffuses the cumulative impact of other sensitive material in our archive.’

No respondent explicitly identified familiarity with RRC as a mitigating factor. Yet, it is notable that the single greatest reason for minimal emotive reactions was the nature of the material. Respondents’ awareness of which records affect them — ‘[w]e received no material about death or dying which would have upset me’ – and assertions of being ‘used to’ interacting with sensitive material — ‘the archive collects a good deal of sensitive records […] and I am well used to these’ – suggests that these respondents believed that the regularity of exposure to emotionally evocative material (in conjunction with other factors) reduces records’ affective potentiality.

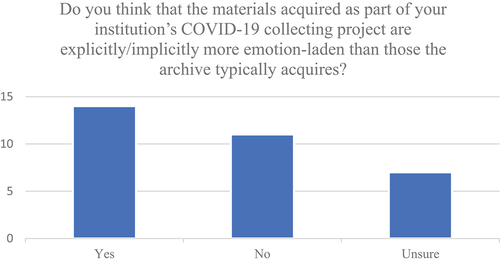

Respondents were asked whether they thought that the records in COVID-19 collections are more emotion-laden than their archives’ ‘typical’ acquisitions, with mostly affirmative responses: 43.75 per cent (n = 14) selected ‘yes,’ whereas 34.37 per cent (n = 11) answered ‘no’ and 21.87 per cent (n = 7) selected ‘unsure’ (see ).

Free text responses to this question revealed that the collecting remit of the COVID-19 project was a crucial determining factor. For ‘yes’ respondents who feel that their COVID-19 collections are more emotion-laden than ‘standard’ acquisitions, the records collected are unusually ‘personal,’ ‘emotionally sensitive,’ and concerned with ‘contemporary trauma;’ for ‘no’ respondents, the records are either comparatively ‘distressing,’ ‘traumatic,’ and ‘sensitive,’ or are simply not deemed emotion-laden because they document, for instance, ‘daily lives and street scenes’ and thus are ‘not so much about trauma.’ Yet the idiosyncrasy of these opinions is clear: whereas one respondent dismissed emotive potentiality because they only collected ‘unworn new’ facemasks, another considered their archive’s COVID-19 collection to be more emotion-laden specifically because ‘face coverings became a symbolic item of dress that was hotly contested.’

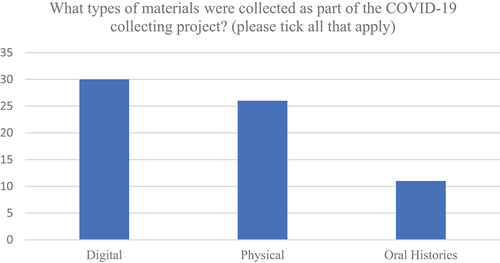

Whilst recognizing the emotive potentiality of seemingly mundane items was not universal, throughout the survey, respondents do signal care towards the ‘overtly’ traumatic. This is implicitly demonstrated by the responses to a question which asked what types of materials were collected during the COVID-19 project (see ): only 34.37 per cent (n = 11) of archives conducted oral histories, in comparison to 93.75 per cent (n = 30) acquiring digital records and 81.25 per cent (n = 26) acquiring physical items. As respondents commented elsewhere that their archive excluded oral histories ‘because of the traumatic effects of the pandemic’ and that ‘[w]e would not collect personal testimony as the event happened because of the mental health risks,’ it is probable that the risk of harming the wellbeing of participants with possible ‘physical, financial, and psychological vulnerabilities’Footnote59 contributed to relatively few archives undertaking oral histories.

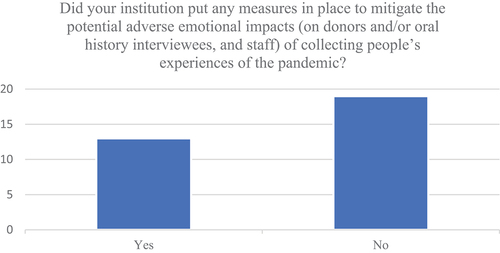

Responses to a question that asked whether the archive implemented any measures to mitigate COVID-19 collecting’s potential adverse emotional impacts on donors/participants and/or staff bolster this supposition that attention to emotions largely only concerned the obviously traumatic: 59.38 per cent (n = 19) of archives did not put any safeguards in place (see ).

Free text responses to this question revealed that where safeguarding of staff was deemed to be taking place, it principally revolved around emotionally equipping and supporting them. Support measures were both part of normal practice — ‘we offer staff free and confidential counselling’ – and specially tailored to the situation, with, for instance, ‘a weekly online “drop in session”’ for ‘personal and practical’ issues and one archive seeking out guidance about ‘staff safeguarding’ from institutions that had previously ‘worked with traumatic material.’ Whilst only one respondent mentioned training in trauma-informed practice, two archives offered mental health first aid training, and two others provided oral history training to help interviewers ‘cope with emotional responses,’ recognizing that staff as well as participants might, as Jennifer Cramer wrote, ‘be vulnerable, especially if they have their own unresolved suffering.’Footnote60 Others indicated that their workplace also accounted for the strain of the pandemic by instituting a more flexible working environment. This included allowing staff to ‘opt out of working with material at any time,’ making deadlines secondary to wellbeing, and designating ‘time for non-Covid activities.’

This focus on training and workplace support positively aligns with them being the first (74 per cent) and third (46 per cent) most popular choices of support mechanisms among participants in Laurent and Wright’s survey.Footnote61 Yet, the fact that only 28.12 per cent (n = 9) of respondents indicated that their institution proactively protected staff’s wellbeing reflects the pervasive lack of consideration for possible negative psychological experiences during archival work.

Only 28.12 per cent (n = 9) of respondents indicated that their archives had mitigations in place for donors/participants too. Of these, 9.37 per cent (n = 3) demonstrated an empathetic ‘commitment to people rather than to records’Footnote62 by letting affective concerns guide the collecting remit. For instance, one respondent indicated that their institution did not pursue oral histories because ‘there was not the capacity to ensure [the] safeguarding [of] participants,’ and another was not ‘too pro-active in identifying and approaching specific people or groups because it was such a difficult time.’ Similarly, one archive ‘slowed collecting slightly to avoid burdening donors,’ and even small measures such as providing ‘signposts to support services’ represented an ethics of care. However, 71.87 per cent (n = 23) of respondents indicated that their service implemented no mitigations, and one respondent in fact commented that their mitigations ‘probably contributed to the project being less successful than we had hoped.’ This echoes the persisting notion of a trade-off between centring wellbeing and ‘success,’ an extension of the traditional idea that archivists’ ‘duty’ to the historic record should be prioritized above all else.

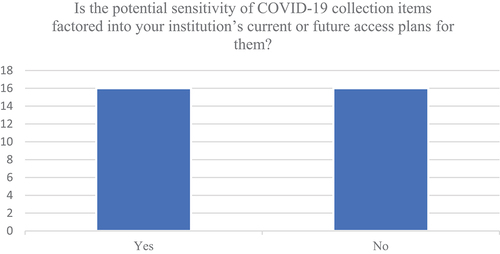

Respondents were asked whether the potential sensitivity of COVID-19 collections has been or will be factored into the archive’s current or future access plans. ‘Yes’ and ‘no’ answers to this were tied, with both options being selected by 50 per cent (n = 16) of respondents (see ).

The free text responses to this question further support the notion that respondents’ concern was largely only towards the ‘explicitly’ traumatic: just as 9.37 per cent (n = 3) of ‘no’ respondents deemed mitigations unnecessary because items’ content is not ‘of an explicit enough nature,’ many ‘yes’ respondents only mentioned ‘overtly distressing material’ as receiving special attention in their access plans. Certainly, the content warnings, ‘verbal warnings to researchers,’ and ‘staggered public access to the material’ that respondents detailed will be beneficial, and it should be noted that the primary reason behind the ‘no’ responses was that the plans for the collections are still too preliminary. Furthermore, one respondent described how their personal support for trigger warnings was stifled by their institution ‘not engaging in this way.’ Nevertheless, this does not alter the fact that 50 per cent of respondents indicated that their workplaces did not, or potentially will not, factor emotional safeguards into their access arrangements for these collections.

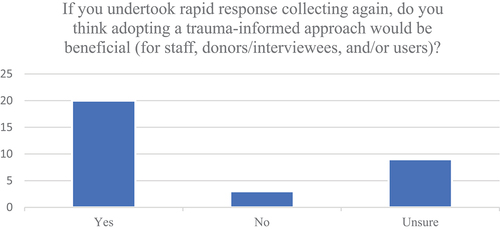

Respondents were asked if they thought adopting a trauma-informed approach would be beneficial in future RRC initiatives. This yielded significantly more positive results, with 62.50 per cent (n = 20) of respondents selecting ‘yes,’ 28.13 per cent (n = 9) selecting ‘unsure,’ and only 9.37 per cent (n = 3) selecting ‘no’ (). This positive embrace may be indicative of a difference between institutional policy and personal perspectives, with respondents’ hindsight coming to the fore in relation to the handling of the emotive impacts inherent in COVID-19 collecting.

Those supportive of a trauma-informed approach in future RRC positioned it as valuable for all; in using such language as ‘crucial,’ ‘the only appropriate way to proceed,’ and ‘the obvious(ly decent and humane) thing to do,’ multiple respondents demonstrated that they believe the approach to be essential. Two respondents commented that they would have benefitted from knowing about the approach before undertaking COVID-19 collecting. Whilst one wrote that ‘[I] would have found this info[rmation] useful for our covid collecting project if known about in 2020,’ the other framed this in terms of emotive potentiality, stating that:

I hadn’t thought about the likelihood of the meanings of the objects […] changing from something relatively positive, i.e., a health intervention at a time of crisis, to something that personally became very negative […] it demonstrated how people can have wide-ranging reactions to seemingly innocuous objects.

21.87% (n = 7) of respondents offered contingent support for trauma-informed practice in RRC, contending that ‘it would depend’ on ‘the event,’ ‘objects,’ and ‘context.’ One respondent, for example, commented that whilst they would consider it if they undertook RRC in an overtly tragic context, the RRC of ‘things like the King’s coronation […] would not require a trauma informed response.’ Another respondent even contended that their archive had been too proactive in mitigating the possible adverse affective consequences of COVID-19 collecting, stating that ‘we were imposing our own worries that people would feel trauma on a situation where that turned out to really not be the case,’ but concluding that ‘this won’t always be the case,’ thus similarly positing a contingent argument.

Interestingly, this respondent discounted their own emotional experiences: although they recognized that staff had ‘the most negative experiences of all,’ the fact that donors/participants did not ‘feel trauma’ informed their opinion that implementing a trauma-informed approach ‘depends on the context.’ Indeed, one respondent explicitly opposed the idea of vicarious trauma among archivists, writing that ‘[w]e’re paid to do this stuff. Sometimes it will be upsetting. That is the job.’ Another respondent expanded upon the idea that ‘professionalism’ and meaningful empathy towards users, donors/participants, and subjects are dichotomous, positing that ‘emotional support and counselling […] need to be undertaken by professionally qualified healthcare staff.’ Whilst archivists cannot be therapists, this exclusion of broader ‘emotional support’ from our professional remit is reflective of the continuing sectoral friction with the notion that archivists should be caregivers for people as well as records.

Main benefits and challenges of RRC

Responses to a question on the greatest challenge of COVID-19 collecting revealed that pandemic-centric practicalities were the principal difficulty. These primarily concerned the effect of lockdown on communication — ‘all communication was done via email which was difficult at times’ – accepting physical deposits, and reaching donors, both logistically and because some respondents felt ‘like people have moved on or do not have the time to dedicate towards collating their records.’ Others emphasized the issue of time pressure, reporting that capturing the ‘now’ entailed working in ‘double quick time’ and that they felt forced to take ‘a knee-jerk approach’ due to the ‘national panic around collecting.’

Alongside needing to act rapidly, RRC’s inherent nature was also highlighted as an issue in its revolving around a highly charged event: respondents noted the increased number of ‘stressed’ ‘interactions with people’ and how it was ‘overwhelming’ to live ‘through the same challenges that we were collecting.’ Whilst not completely attributable to RRC, the comments referencing the impact on respondents’ mental health of not receiving ‘appropriate’ or ‘meaningful’ support from their ‘line manager[s] and employer[s]’ indicate the risks of conducting RRC without adequate workplace support structures. One respondent extended this affective lens to records’ donors and subjects: ‘those collecting need to be representative of those collected’ otherwise they cannot achieve ‘empathy and real understanding’ with donors and subjects, therefore ‘[r]eal work needs to be done internally in institutions before they embark on this work.’

Responses to the reverse question, asking about the greatest benefit of COVID-19 collecting, revealed that the pandemic’s inclusion in the archival record and the collections’ perceived ability to act as resources for the future were deemed its most worthwhile facets. The collecting’s importance to ‘hold power to account,’ enhance archivists’ skillsets and archives’ profiles, and provide emotional benefits were also surfaced. Respondents’ comments on emotional benefits not only referenced the ‘sense of satisfaction’ donors had in knowing ‘their responses/testimony had joined a collection for permanent preservation,’ and the potential for future users to utilize the collections to ‘process’ and ‘grieve,’ but also described archivists’ own sense of purpose. One respondent, for instance, cited ‘the feeling that we were doing something worthwhile.’

Discussion

What factors influenced archivists’ affective engagement with covid-19 collections?

Individuals’ lived experiences of the pandemic was the most significant factor underlying negative affective experiences of engaging in COVID-19 collecting. There was a belief amongst some respondents that being ‘used to’ engaging with sensitive material has a mitigating effect, enabling archivists to recognize records as particularly emotion-laden but not be affected themselves. However, research by Sloan et al. indicates that archivists have a tendency to downplay their emotional responses to records, often due to misplaced feelings of guilt.Footnote63 Workplace-related factors, namely support, training, and general consideration for wellbeing were also raised as potentially having an important offsetting effect. Conversely, a lack of workplace attention to emotions exacerbated psychological stress, although in some cases this dearth of support was due to lockdown itself. Positive emotions, whilst comparatively rare, revolved largely around a sense of purpose, a feeling of emotional release, and empathizing with donors/participants.

To what extent did archives plan to mitigate the possible affective risks of covid-19 collecting for staff, donors/participants, and future users?

Although the majority of respondents asserted the importance of trauma-informed practice in future RRC, during COVID-19 collecting, there were inconsistent levels of safeguarding in place. A handful of archives centred emotive implications, and multiple institutions implemented some form of protective measures. However, less than 30 per cent (n = 9) of respondents indicated that their workplace tried to mitigate the potential affective risks facing donors/participants and staff, and 50 per cent (n = 16) noted that their workplace had not or will not put measures in place to limit possible adverse reactions among users. Notably, some respondents personally supported/support maximizing psychological safety but were/are prohibited from doing so by their institutions.

How much of a role did affect play in covid-19 collecting?

Affect featured to a greater degree than the scholarship on COVID-19 collecting and RRC more broadly indicated that it would. Certainly, emotions were not everything — comments relating to the broader practicalities of archiving during a pandemic were pervasive throughout and, as aforementioned, many archivists neither reported potent affective impacts nor deemed safeguarding measures necessary. Yet, with over 40 per cent (n = 13) experiencing stronger emotions during COVID-19 collecting than during ‘typical’ archival work, and the majority reporting that the records are more emotion-laden than their archives’ ‘standard’ acquisitions, one could argue that affect constituted a significant part of the process.

Towards trauma-informed RRC

These findings indicate that emotions need to be a greater consideration in future RRC if we are to protect the wellbeing of all. It is true that COVID-19 was unique in the pervasiveness of its reach and its additional pressures (such as the negative effect of lockdown on workplace support structures). Yet, if RRC always involves archiving during or immediately after a highly charged event, and it was the nature of the event and the immediacy of the collecting that principally made COVID-19 collecting affectively impactful, then RRC is seemingly intrinsically imbued with emotive power.

The affective possibilities of RRC do not only apply to archivists. We need to consider donors/participants’ unprocessed trauma and the emotive signification their records have for them. As RRC records can, in explicit content and implicit meaning, be especially emotionally charged, users too can be affectively impacted. For all three groups, such affective impacts may be positive: catharsis, community bonding, and the feeling of doing something worthwhile are not uncommon in RRC. However, the heightened potential for trauma in RRC should lead us to prioritize the psychological health of everyone involved. A trauma-informed approach is therefore essential.

Following trauma-informed practice’s five core principles of ‘safety, trust and transparency, choice, collaboration, and empowerment’Footnote64 will entail many significant shifts in RRC. It will firstly involve archives considering the possible emotional burden of the event itself prior to undertaking RRC. As collaboration means working with, rather than for, someone,Footnote65 archivists need to work with the implicated community to decide the appropriateness of the collecting, otherwise trust could be lost if RRC appears to commodify grief. Before undertaking RRC, archives also need to consider whether they have the resources and know-how to engage donors/participants in a safe, supportive way. The principle of choice, which requires being ‘driven by people’s preferences and expertise about what is most appropriate for them,’Footnote66 necessitates allowing archivists to decide whether to involve themselves in RRC. Archivists who do partake in RRC should, for their safety and ability to retain trust in their institutions, receive both the necessary training and support to complete the project. This includes being allocated time to engage in non-RRC work and, crucially, being granted adequate recovery time through extended breaks when the labour feels significantly emotionally charged. Archivists need to feel empowered to bring ‘their lived experiences, positionalities, and perspectives’ to the project,Footnote67 and they should empower donors/participants and users too by allowing them the space to express their emotions in an appropriately supportive environment.

Trauma-informed RRC will too, for the wellbeing of users as well as archivists, involve becoming more attuned to records’ emotive potentiality, realizing that individuals’ lived experiences and opinions can make seemingly innocuous items affectively powerful. Recognizing the idiosyncrasy of emotive potentiality will further bolster the need for archivists to exercise choice in deciding whether or not to undertake RRC and will mean that users should have a choice in how to view the records, with, for example, places they ‘can access records in private.’Footnote68

Whilst respondents demonstrated clear support for a trauma-informed approach (and there is general agreement that the practice has value, exemplified by 97 per cent of Laurent and Wright’s survey respondents affirming its importance in archival education),Footnote69 the practice’s continued placement outside the archival mainstream means RRC becoming wellbeing-centric will be a significant undertaking. Yet, the shift to trauma-informed archiving is crucial if we are to practise RRC that is grounded in the emotional health of all.

Limitations of findings

The primary limitation of these findings relates to the survey’s sample size. Although non-probability sampling is by its nature unrepresentative, the fact that the survey received a relatively small number of responses (with only a singular response from a community archive), further weakens the results’ generalizability. This signifies that the findings offer indications of how COVID-19 collecting was experienced, rather than definitive generalizations.

Additionally, whilst the survey deliberately did not request only one response from each archive due to the subjectivity of opinions and emotional reactions, this means that the answers might give a false impression of reality. For instance, if three of the 12 respondents who selected ‘yes’ to their archive having previously conducted RRC were from the same institution, the picture of greater than expected institutional familiarity with the practice is undermined. Although this scenario is unlikely, this uncertainty nevertheless qualifies the results’ accuracy.

The final limitation is that in disseminating the survey on the Trauma-Informed Archives Community of Practice Discord channel, there is a chance of responses to the question on the validity of a trauma-informed approach to future RRC being biased in favour of the approach. Since, however, this potential bias relates to only one question, its possible effect is minimal.

Conclusions

The place of empathetic engagement as part of an ethics of care, as well as the boundaries and safeguards required around empathetic witnessing, is beginning to be discussed in archival discourse.Footnote70 However, empathy, trauma-informed approaches, and adopting an ethics of care continue to occupy a marginal place in the theory and praxis of RRC. This research has sought to counter this by adopting an affect-centric approach to the analysis of COVID-19 collecting, providing a significant intervention in narratives of RRC by foregrounding the profound potential for emotions to be implicated in the practice.

As one of the first affect-driven examinations of RRC — encompassing the first empirical study of archivists involved in RRC — this research is crucial in its indication that the sector’s inadequate attention to feelings is prohibiting us from conducting RRC in a way that centres psychological safety. It has shown, therefore, that in our implementation of RRC, we should pay more attention to designing empathetically-driven and trauma-informed collecting and access frameworks for the benefit of all: the communities we serve, donors/participants, future users, and each other. Such approaches must take into account the idiosyncrasy of emotive potentiality and the pressures that often accompany extraordinary times.

There is great scope for building upon these findings. Delving deeper into the intensity of and influences on archive workers’ affective experiences during RRC is essential, and should be ascertained through larger-scale national and even (for transnational events) international empirical studies; empirically assessing donors/participants’ emotional engagement with RRC is necessary too. The most suitable, effective methods for educators, professional bodies, and workplaces to emotionally support and prepare staff should also be further explored — the development of RRC training courses that provide instruction in limiting, mitigating, and coping with potential emotive responses should be a core consideration for scholars and practitioners alike. Moreover, the very notion of RRC as a ‘duty’ should receive greater scrutiny, with more attention in the discourse to alternative routes through which archives could provide a ‘rapid response’ during times of tragedy or transition.

Embedding trauma-informed principles in RRC will require no less than a fundamental recalibration of archival priorities. It will entail forgoing the notion of a trade-off between centring psychological safety and being ‘successful’ and dispensing with the idea that the archivist’s Sisyphean task of assembling a ‘complete’ archival record is our primary goal. The pursuit of empathetic and trauma-informed RRC will, ultimately, require reconceptualizing archiving as ‘a caring profession.’Footnote71

Author contribution Statement

This article is based on Kay Bannell’s dissertation submitted in fulfilment of their MA in Archives and Records Management which was supervised by Anna Sexton. Both authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection, analysis and writing of the dissertation from which the article is based, Kay Bannell. Preparation of the first draft of the article manuscript, Anna Sexton. Both authors collaborated on subsequent redrafts including responding to reviewers’ comments and both approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the participants in the survey for their valuable and thoughtful contributions.

The first author would also like to thank Aiden Chan and Emily Hughes for their feedback during the drafting of this article.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Kay Bannell

Kay Bannell is a Retrievals Assistant at the Victoria and Albert Museum. They were awarded their MA in Archives & Records Management from UCL in 2023. Their research interests lie in the emotional dimensions of the archival endeavour and person-centred approaches to recordkeeping.

Anna Sexton

Anna Sexton is the Director for the Centre for Critical Archives & Records Management Studies, and the MA in Archives & Records Management at UCL. Her research interests lie in participatory, creative and trauma-informed approaches to recordkeeping particularly in health and social care contexts.

Notes

1. ”Collecting Covid-19,” Archives Wales.

2. Cambridge University Library, “Covid-19 Collection”

3. Borthwick Institute for Archives, “The York COVID-19 Archive”

4. Sexton, “Working with traumatic records”

5. Hobbins, “Collecting the crisis or the collecting crisis?” 565.

6. Davies, “Crowd Coaxing and Citizen Storytelling,” 4.

7. Scheinfeldt, “Memories: September 11 Digital Archive”

8. Haskins, “Between Archive and Participation,” 414.

9. Kitch, “A living archive of modern protest,” 125.

10. Gledhill, “Collecting Occupy London,” 347; and Smit, Heinrich and Broersma, “Activating the past,” 3119–39.

11. Jules and Summers, “Documenting the Now Ethics White Paper”

12. Milošević, “Historicizing the present,” 57.

13. Society of American Archivists, “Tragedy Response Preparedness Checklist”

14. Tebeau, “A Journal of the Plague Year,” 1–8; and Greenwood, “Archiving COVID-19,” 288–311.

15. Zumthurm and Krebs, “Collecting Middle-Class Memories?” 483–93.

16. Spennemann, “Curating the Contemporary,” 27–42 and Kosciejew, “Remembering COVID-19,” 20.

17. Sexton, “Covid-19 Collecting,” 103–113 and Emmens and McEnroe, “Acquiring infection,” 1–7.

18. Cvetkovich, An Archive of Feelings, 7–8.

19. Ahmed, The Cultural Politics of Emotion, 10, 14.

20. Cifor, “Affecting relations,” 7–31.

21. Ibid., 10.

22. Ibid.

23. Rau, “Dealing with Feeling,” 94–108.

24. See, for example: Lee, “Be/longing in the archival body,” 33–51; Gilliland and Caswell, “Records and their imaginaries,” 53–75 and Caswell and Cifor, “From Human Rights to Feminist Ethics,” 23–43.

25. Gilliland and Caswell, “Records and their imaginaries,” 55.

26. Caswell and Cifor, “From Human Rights to Feminist Ethics,” 24.

27. Ibid.

28. Douglas, Alisauskas, and Mordell, “Treat Them with the Reverence of Archivists,” 84–120; Douglas and Alisauskas, “It Feels Like a Life’s Work,” 6–37; Douglas et al., “These are not just pieces of paper,” 8.

29. Regehr et al., “Emotional responses in archival work,” Regehr et al., “Humans and records are entangled,” 563–83.

30. Sexton, “Working with traumatic records,” and Gilliland and Caswell, “Records and their imaginaries,” 53.

31. Sloan, Vanderfluit, and Douglas, “Not Just My Problem to Handle,” 7.

32. Laurent and Wright, “Report,” 10.

33. ”A Trauma-Informed Approach to Managing Archives,” Australian Society of Archivists; and “Implementing Trauma-Informed Archival Practice,” Australian Society of Archivists.

34. ”Resources,” Archives and Records Association (ARA).

35. ARA, “ARA Support Guide for staff”

36. UCL’s MA in Archives & Records Management is introducing an optional module in Trauma-Informed Approaches to Managing Records, Archives & Cultural Heritage to be taught for the first time in 2024.

37. Laurent and Wright, “Report,” 12.

38. Gardner and Henry, “September 11 and the Mourning After,” 37–52.

39. Smith, “Negotiating Community Literacy Practice,” 117; Coaplen, “Recovering home,” 32–45; Perry, “Documenting disaster after Katrina,” 76–79.

40. Schwartz et al., “Rapid-Response Collecting,” 105–14.

41. Gibson and Blaymires, “First Wave Collecting,” 12.

42. Mackie and Crozier-De Rosa, “Rallying women,” 975–1001; Watts, “Applying radical empathy,” 191–201.

43. Pollen and Lowe, “Picturing Lockdown or Feeling Lockdown?.’

44. Greenwood, ‘Archiving COVID-19,’ 293.

45. Bushey, “Participatory Archives Approach to Fostering Connectivity,” 2379–93.

46. Evans, “Love (and Loss) in the Time of COVID-19,” 22.

47. Tansey, “No one owes their trauma to archivists”

48. Morgan et al., “Interviewing at a distance,”; and Kaplan, “Cultivating Supports while Venturing into Interviewing,” 214–26.

49. Cramer, “First, Do No Harm,” 205.

50. Pickard, Research Methods in Information, 65.

51. Ethics approved at Departmental level in accordance with UCL’s procedures for low-risk Master’s research.

52. Jaggar, “Love and Knowledge,” 153.

53. Ibid., 167.

54. Schwandt, “Constructivist, interpretivist approaches to human inquiry,” 221.

55. Pickard, Research Methods in Information, 12.

56. ‘COVID-19,’ International Council on Archives (ICA). The full quote is ‘the duty to document does not cease in a crisis, it becomes more essential’

57. Regehr et al., “Emotional responses in archival work”

58. Cifor, “Affecting relations,” 9.

59. Cramer, “First, Do No Harm,” 204.

60. Ibid., 206.

61. Laurent and Wright, “Report,” 15.

62. Regehr et al., “Humans and records are entangled,” 576.

63. Sloan, Vanderfluit, and Douglas, “Not Just My Problem to Handle.”

64. Wright and Laurent, “Safety, Collaboration, and Empowerment,” 41.

65. Ibid., 54.

66. Ibid., 53.

67. Ibid., 68.

68. Ibid., 65.

69. Laurent and Wright, “Report,” 16.

70. Caswell and Cifor, “From Human Rights to Feminist Ethics,” 23–43; and Regehr et al., “Humans and records are entangled,” 563–83.

71. Sloan, Vanderfluit, and Douglas, “Not Just My Problem to Handle,” 21.

Bibliography

- Ahmed, Sara. The Cultural Politics of Emotion. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2004.

- Archives, and Records Association. “ARA Support Guide for Staff Working with Potentially Disturbing Material and Records. Support Guide One.” Accessed June 10, 2023a. https://static1.squarespace.com/static/60773266d31a1f2f300e02ef/t/6082cc7ff587f165d92a9258/1619184767375/ARA_Emotional_Support_Guide_1.pdf.

- Archives, and Records Association. “Resources.” Accessed June 10, 2023b. https://www.archives.org.uk/resources.

- Australian Society of Archivists. “Implementing Trauma-Informed Archival Practice.” Accessed June 10, 2023a. https://www.archivists.org.au/learning-publications/workshop-info.

- Australian Society of Archivists. “A Trauma-Informed Approach to Managing Archives.” Accessed June 10, 2023b. https://www.archivists.org.au/events/event/a-trauma-informed-approach-to-managing-archives.

- Borthwick Institute for Archives. “The York COVID-19 Archive.” University of York. Accessed August 10, 2023. https://www.york.ac.uk/borthwick/projects/york-covid-19-archive/.

- Bushey, Jessica. “A Participatory Archives Approach to Fostering Connectivity, Increasing Empathy, and Building Resilience During the COVID-19 Pandemic.” Heritage 6, no. 3 (2023): 2379–2393. doi:10.3390/heritage6030125.

- Cambridge University Library. “Covid-19 Collection.” University of Cambridge. Accessed August 10, 2023. https://www.lib.cam.ac.uk/collections/departments/manuscripts-university-archives/significant-archival-collections/covid-19.

- Caswell, Michelle, and Marika Cifor “From Human Rights to Feminist Ethics: Radical Empathy in Archives.” Archivaria 81 (2016): 23–43.

- Cifor, Marika. “Affecting Relations: Introducing Affect Theory to Archival Discourse.” Archival Science 16, no. 1 (2016): 7–31. doi:10.1007/s10502-015-9261-5.

- Coaplen, Carrie Jo. “Recovering Home: Hurricane Katrina Survivors Rebuild Homes in a Digital Community.” Journal of Arts and Communities 4 (2012): 32–45. doi:10.1386/jaac.4.1-2.32_1.

- Cramer, Jennifer. ““First, Do No Harm”: Tread Carefully Where Oral History, Trauma, and Current Crises Intersect.” The Oral History Review 47, no. 2 (2020): 203–213. doi:10.1080/00940798.2020.1793679.

- Cvetkovich, Ann. An Archive of Feelings: Trauma, Sexuality, and Lesbian Public Cultures. Durham, USA: Duke University Press, 2003.

- Davies, Kerrie M. “Crowd Coaxing and Citizen Storytelling in Archives of Crisis.” Life Writing 20, no. 2 (2023): 351–365. doi:10.1080/14484528.2022.2106611.

- Douglas, Jennifer, and Alexandra Alisauskas. ““It Feels Like a Life’s Work”: Recordkeeping As an Act of Love.” Archivaria 91, no. 91 (2021): 6–37. doi:10.7202/1078464ar.

- Douglas, Jennifer, Alexandra Alisauskas, Elizabeth Bassett, Noah Duranseaud, Ted Lee, and Christina Mantey. “‘These Are Not Just Pieces of paper’: Acknowledging Grief and Other Emotions in Pursuit of Person-Centered Archives.” Archives & Manuscripts 50, no. 1 (2022): 5–29. doi:10.37683/asa.v50.10211.

- Douglas, Jennifer, Alexandra Alisauskas, and Devon Mordell ““Treat Them with the Reverence of Archivists”: Records Work, Grief Work, and Relationship Work in the Archives.” Archivaria 88 (2019): 84–120.

- Emmens, S., and N. McEnroe. “Acquiring Infection: The Challenges of Collecting Epidemics and Pandemics, Past, Present and Future.” Interface Focus 11, no. 6 (2021): 1–7. doi:10.1098/rsfs.2021.0030.

- Evans, Ferrin. “Love (And Loss) in the Time of COVID-19: Translating Trauma into an Archives of Embodied Immediacy.” The American Archivist 85, no. 1 (2022): 15–29. doi:10.17723/2327-9702-85.1.15.

- Gardner, James B., and Sarah M. Henry. “September 11 and the Mourning After: Reflections on Collecting and Interpreting the History of Tragedy.” The Public Historian 24, no. 3 (2002): 37–52. doi:10.1525/tph.2002.24.3.37.

- Gibson, Stephanie, and Shannon Blaymires. “First Wave Collecting – Christchurch Terror Attacks, 15 March 2019.” Curator: The Museum Journal 66, no. 2 (2023): 233–255. doi:10.1111/cura.12541.

- Gilliland, Anne J., and Michelle Caswell. “Records and Their Imaginaries: Imagining the Impossible, Making Possible the Imagined.” Archival Science 16, no. 1 (2016): 53–75. doi:10.1007/s10502-015-9259-z.

- Gledhill, Jim. “Collecting Occupy London: Public Collecting Institutions and Social Protest Movements in the 21st Century.” Social Movement Studies 11 (2012): 342–348. doi:10.1080/14742837.2012.704357.

- Greenwood, Amanda. “Archiving COVID-19: A Historical Literature Review.” The American Archivist 85, no. 1 (2022): 288–311. doi:10.17723/2327-9702-85.1.288.

- Haskins, Ekaterina. “Between Archive and Participation: Public Memory in a Digital Age.” Rhetoric Society Quarterly 37, no. 4 (2007): 401–422. doi:10.1080/02773940601086794.

- Hobbins, Peter. “Collecting the Crisis or the Collecting Crisis? A Survey of COVID-19 Archives.” History Australia 17, no. 3 (2020): 565–567. doi:10.1080/14490854.2020.1796510.

- International Council on Archives. “COVID-19: The Duty to Document Does Not Cease in a Crisis, it Becomes More Essential.” Accessed August 10, 2023. https://www.ica.org/en/covid-19-the-duty-to-document-does-not-cease-in-a-crisis-it-becomes-more-essential.

- Jaggar, Alison M. “Love and Knowledge: Emotion in Feminist Epistemology.” Inquiry 32, no. 2 (1989): 151–176. doi:10.1080/00201748908602185.

- Jules, Bergis, and Ed Summers. “Documenting the Now Ethics White Paper.” Medium, July 19, 2018. https://news.docnow.io/documenting-the-now-ethics-white-paper-43477929ea3e.

- Kaplan, Anna F. “Cultivating Supports While Venturing into Interviewing During COVID-19.” The Oral History Review 47, no. 2 (2020): 214–226. doi:10.1080/00940798.2020.1791724.

- Kitch, Carolyn. ““A Living Archive of Modern protest”: Memory-Making in the Women’s March.” Popular Communication 16, no. 2 (2018): 119–127. doi:10.1080/15405702.2017.1388383.

- Kosciejew, Marc. “Remembering COVID-19; Or, a Duty to Document the Coronavirus Pandemic.” IFLA Journal 48, no. 1 (2022): 20–32. doi:10.1177/03400352211023786.

- Laurent, Nicola, and Kirsten Wright. “Safety, Collaboration, and Empowerment. Trauma-Informed Archival Practice.” Archivaria 91, no. 91 (2023): 38–73. doi:10.7202/1078465ar.

- Laurent, Nicola, and Kirsten Wright “Report: Understanding the International Landscape of Trauma and Archives.” February (2023): 1–25. https://www.ica.org/sites/default/files/trauma_and_archives_survey_initial_report_eng.pdf.

- Lee, Jamie A. “Be/Longing in the Archival Body: Eros and the “Endearing” Value of Material Lives.” Archival Science 16, no. 1 (2016): 33–51. doi:10.1007/s10502-016-9264-x.

- Mackie, Vera, and Sharon Crozier-De Rosa “Rallying Women: Activism, Archives, and Affect.” Women’s History Review 31, no. 6 (2022): 975–1001. doi:10.1080/09612025.2022.2090711.

- Milošević, Ana. “Historicizing the Present: Brussels Attacks and Heritagization of Spontaneous Memorials.” International Journal of Heritage Studies 24, no. 1 (2018): 53–65. doi:10.1080/13527258.2017.1362574.

- Morgan, Charlie, Rob Perks, Mary Stewart, and Camille Johnston. “Interviewing at a Distance.” Oral History Society. Accessed June 10, 2023. https://www.ohs.org.uk/covid-19-remote-recording/.

- Perry, Gary K. “Documenting Disaster After Katrina: Using Online Tools to Rebuild Community.” Contexts 11, no. 2 (2012): 76–79. doi:10.1177/1536504212446470.

- Pickard, Alison Jane. Research Methods in Information. 2nd ed. London: Facet Publishing, 2013.

- Pollen, Annebella, and Paul Lowe. “Picturing Lockdown or Feeling Lockdown?” Historic England. September 17, 2021. https://historicengland.org.uk/whats-new/research/back-issues/picturing-lockdown-or-feeling-lockdown/.

- Rau, Asta. “Dealing with Feeling: Emotion, Affect, and the Qualitative Research Encounter.” Qualitative Sociology Review 16, no. 1 (2020): 94–108. doi:10.18778/1733-8077.16.1.07.

- Regehr, Cheryl, Wendy Duff, Jessica Ho, Christa Sato, and Henria Aton “Emotional Responses in Archival Work.” Archival Science 23, no. 4 (2023): 545–568. doi:10.1007/s10502-023-09419-5.

- Regehr, Cheryl, Wendy Duff, Christa Sato, and Henria Aton ““Humans and Records Are entangled”: Empathic Engagement and Emotional Response in Archivists.” Archival Science 22, no. 4 (2022): 563–583. doi:10.1007/s10502-022-09392-5.

- Scheinfeldt, Tom. “Memories: September 11 Digital Archive.” History News Network. Accessed June 9, 2023. http://hnn.us/articles/959.html.

- Schwandt, Thomas A. “Constructivist, Interpretivist Approaches to Human Inquiry.” In The Landscape of Qualitative Research: Theories and Issues, edited by Norman K. Denzin and Yvonna S. Lincoln, 221–259. Thousand Oaks, USA: SAGE Publications, 1998.

- Schwartz, Pam, Whitney Broadaway, Emilie S. Arnold, Adam M. Ware, and Jessica Domingo. “Rapid-Response Collecting After the Pulse Nightclub Massacre.” The Public Historian 40, no. 1 (2018): 105–114. doi:10.1525/tph.2018.40.1.105.

- Sexton, Anna. “Working with Traumatic Records: How Should We Train, Prepare and Support Recordkeepers?” Paper Presented at Archival Education and Research Institute, July 8–12, 2019. https://discovery.ucl.ac.uk/id/eprint/10093038/, Liverpool.

- Sexton, Anna. “Covid-19 Collecting: Is Ethics at the Table?” The Public Historian 43, no. 2 (2021): 103–113. doi:10.1525/tph.2021.43.2.103.

- Sloan, Katie, Jennifer Vanderfluit, and Jennifer Douglas “Not ‘Just My Problem to Handle’: Emerging Themes on Secondary Trauma and Archivists.” Journal of Contemporary Archival Studies 6, no. 20 (2019): 1–24.

- Smith, Kevin G. “Negotiating Community Literacy Practice: Public Memory Work and the Boston Marathon Bombing Digital Archive.” Computers and Composition 40 (2016): 115–130. doi:10.1016/j.compcom.2016.03.003.

- Smit, Rik, Ansgard Heinrich, and Marcel Broersma. “Activating the Past in the Ferguson Protests: Memory Work, Digital Activism and the Politics of Platforms.” New Media & Society 20, no. 9 (2018): 3119–3139. doi:10.1177/1461444817741849.

- Society of American Archivists. ““Tragedy Response Preparedness Checklist.” Google Docs.” Last modified July 9, 2019. https://docs.google.com/document/d/1kBwop3TOJZ-nlkRj_Lgul985v2YY20Vf8szG4H0FQVw/edit.

- Spennemann, Dirk. “Curating the Contemporary: A Case for National and Local COVID-19 Collections.” Curator: The Museum Journal 65, no. 1 (2022): 27–42. doi:10.1111/cura.12451.

- Tansey, Eira. “No One Owes Their Trauma to Archivists, Or, the Commodification of Contemporaneous Collecting.” June 5, 2020. https://eiratansey.com/2020/06/05/no-one-owes-their-trauma-to-archivists-or-the-commodification-of-contemporaneous-collecting/?fbclid=IwAR3vEQOqANWV-syWrW-Bix0EvE6UjKCAnj9_HO-k6uomh6ynpU5FSDTDlSc.

- Tebeau, Mark. “A Journal of the Plague Year: Rapid-Response Archiving Meets the Pandemic.” Collections: A Journal for Museum and Archives Professionals 17, no. 3 (2021): 199–206. doi:10.1177/1550190620986550.

- Wales, Archives. “Collecting Covid-19: Recording the Impact in Wales.” Accessed August 10, 2023. https://archives.wales/collecting-covid-19/.

- Watts, Gina. “Applying Radical Empathy to Women’s March Documentation Efforts: A Reflection Exercise.” Archives and Manuscripts 45, no. 3 (2017): 191–201. doi:10.1080/01576895.2017.1373361.

- Zumthurm, Tizian, and Stefan Krebs. “Collecting Middle-Class Memories? The Pandemic, Technology, and Crowdsourced Archives.” Technology and Culture 63, no. 2 (2022): 483–493. doi:10.1353/tech.2022.0059.