Introduction

This Forum article is based on an ethnographic analysis of social media usage by young queer men in Kolkata, India between 2012 and 2018.Footnote1 I conducted digital ethnography during this entire period with extended field work in 2013, 2014 and 2017. Interviews were conducted during the entire period both online and offline. This ethnographically informed research on queer social media offers a new perspective on porn consumption and representation. It also asks how the use of platforms such as Grindr and PlanetRomeo affects the way people interact sexually through self-made pornographic images. Whilst many of these images are impregnated with pornographic representations and stereotypes, it also offers a new site for interrogating issues of porn aesthetics within profile images and the visual dialogue of queer Indian males on digital platforms. By porn aesthetics I refer to the potential value and affective gestures that imbibe these images – one that brings together the hyperreality of sexuality with the authenticity of South Asian identities (markers of class, caste, religion). The context of Kolkata is especially important too, as masculinity has a vexed and complex history in West Bengal where concomitantly Bengali men were often constructed as lacking in power and, hence, as effete and emasculated (Boyce and Dasgupta Citation2021; Sinha Citation1995). This in turn outlines some of the visual practices employed on platforms such as Grindr and PlanetRomeo. Whilst the fixity of masculine identities has destabilized in recent years, there still remains a dominance of heteronormative masculinity, especially in gay porn (Mercer Citation2017).

The profile image

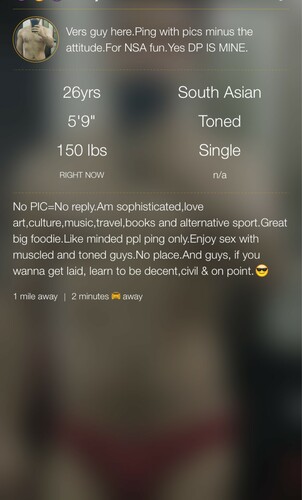

It is a late Saturday afternoon in Kolkata. In the last few weeks there have been a number of ‘gay parties’ being advertised on Facebook groups. These parties, which are organized by both individuals and community groups (Pink Party Kolkata, Kolkata Rainbow Pride Festival Party), are mostly advertised via email, social media, text messages and word of mouth. There is an air of jubilation since the Supreme Court decision to unanimously rule that Section 377 was unconstitutional, thus removing a cloud of uncertainty and fear from the lives of LGBTQ people in India. Within days, a number of marches, talks and parties were organized and publicized on social media. After scrolling through some of these invites for a while I decided to log in to my Grindr account. After a few anonymous tiles I started chatting to Andy. Andy had an interesting profile and was only a few minutes away from me but what particularly caught my eye was the display of his upanayan (sacred) thread against his chiselled body displayed in his underwear. The thread signified his upper caste status in India, which along with his profile information ‘sophisticated’ and ‘love art, culture, music’ also signified his class status ().

Figure 1. Andy’s profile with personal information removed. © Grindr (screengrab captured 1 October 2016).

Andy and I started chatting straight away. We both had a similar background having studied in Christian missionary schools and a few common friends. After a few minutes of flirty chats, we decided to meet up. I told him how intrigued I was by his sacred thread on his profile picture and asked if it was deliberate. Andy was actually quite honest in describing that it was deliberate as it was considered erotic by several people he met on the app who fetishized his caste background (as an upper caste Brahmin with a thread). Even though it remained unsaid, Andy was also signalling his own caste desire in his potential partners. Over the course of that month I met Andy a couple more times. Given our backgrounds – we both went to private Christian missionary schools and had a few acquaintances in common – I became a regular person who he started including in his social life. My own class privilege and caste identity played a role in this acceptance. For Andy I was recognized as ‘one of them’. Albury et al. (Citation2017) have discussed that the convergence of public and private life associated with social media technologies which mediate dating, relationships and sex is also connected to other aspects of our lives and identities.

The Grindr profile is created through an assemblage of written text and visual cues. Mowlabocus (Citation2010, 81) asserts that, ‘If gay male digital culture remediates the body and does so through a pornographic lens, then it also provides the means for watching that body, in multiple ways and with multiple consequences’. The profile picture identifies the user, evidences his desires and implicates his intentions. McGlotten (Citation2013, 127) calls it ‘image labour’, explaining that profile creation is a process laden with affective demands entering one into a ‘market place of desire, of sexual value and existing hierarchies’. Mowlabocus (Citation2021) more recently argues how apps such as Grindr have proliferated a form of ‘sexual racism’ which essentializes race and desire, and on being confronted on their practices argues that this is about ‘desire’ and not ‘discrimination’. We see a similar pattern in the case of Kolkata too, where practices such as class, religion and caste preference are defended as desire and ‘wanting others like me’ (Andy) rather than recognizing the privilege at play.

Andy described Grindr as ‘interactive porn’. He did not necessarily log in there to hook up. He used his profile image as a thirst trap to chat to other users, join in sexual conversation and for quickly ‘getting off’. As he said:

Why pay for onlyfans when I can have an erotic chat session with someone, exchange pictures and get the ‘real thing’ online?

Race (Citation2018, 1328) argues that pornography is no longer just the ‘production of sexual arousal through representation practices’. Rather, interpersonal exchanges such as sexual chatting activities – for example, the exchange of intimate pictures (privately or publicly as thirst traps which encourage interaction) or videos – characterize the kind of ‘interactive porn’ that Andy refers to. These forms of self-pornography have become an essential part of the sexual grammar that govern how users I have spoken to in my research consume porn and participate in sexual activities online.

Pic exchange

In addition to the textual component of chatting, private sharing of pictures is another way through which my respondents participate in intimate encounters. ‘Pic exchange’ remains a process laden with affective demands which Campbell and Carlson (Citation2002, 591) call ‘exchanging privacy for participation’. Picture sharing can take place at various points of an encounter. This could take place at the very beginning where a connection is being established and when users do not want to initiate conversation with someone without at least some kind of a face or body picture. It was not uncommon to see profiles with ‘no pic no dic’ (sic) during my research. Other times, exchange of intimate or ‘fun’ could happen much earlier even before any other conversation. Whilst scholars such as Jones (Citation2005) and Tziallas (Citation2015) argue that in online interactions information emerges incrementally sometimes with a form of strategic ambiguity, this has not always been the case with my research informants. Neel, for example, described how he often began a conversation by sending a couple of pictures including erotic ones and asking for reciprocity even before any other conversation:

I send a few of my pictures and ask for ‘Ur Pics’. There is no point in even having a conversation if I am not sexually interested is there?

What if they want to have a conversation and not send you pictures right away.

depending on what I am looking for at that time I might chat but I would usually just block them and move on. You’re on grindr not shaadi.com

McGlotten (Citation2013) argues that the erotic representations and exchange of pictures is part of the visual market of gift economy. The smartphone screen acts as an affective device bringing sexual gratification as Andy and I chatted about the city’s gay scene interspersed with flirtatious erotic innuendos and exchange of pictures. The act of ‘pic exchange’, Jones (Citation2005) argues, is based on subtle choreography and reciprocity and one of the many ways through which gay men organize their sexual lives. The act of pic exchange whilst offering ‘the wordless suggestion of intercourse’ (Paasonen, Jarrett, and Light Citation2019, 77) also signals different forms of sexual intimacy. As Andy reminded me:

I don’t have ‘place’ most of the time. Ever since my parents retired I don’t really have the house to myself anymore so I have to plan my meetings quite carefully. There is a lot of time investment in this. Through exchanging ‘fun pics’ I want to get to know the other person, see if we sexually turn each other on. It is the first step towards what will happen next.

Receiving a ‘dickpic’ through a pic exchange is more erotic than finding it online, as another user SweetLuv, who I met on PlanetRomeo, explained to me:

If I have shared dickpics with someone it means he is quite near. It is ‘more real’ than sourcing it from pornhub or xvideos which doesnt really have that many desis anyway.

I am often on my 3G which isn’t that great most of the time in my neighbourhood. Often it is difficult to quickly stream a video especially if I am on my own. Time is precious. Exchanging pictures and having a sexy chat session is much faster. (SweetLuv, 23 May 2016)

I don’t want to come out too needy with long messages. We have already sent the pictures. We have seen our nude bodies. Sometimes it can feel awkward so I move to footprints like ‘great body’ ‘sex now’ or ‘hot cock’. I have had some great ‘hot sessions’ just through exchanging nudes and footprints! I am always doing this on Grindr and Planetromeo when I am bored.

Berlant (Citation2004) argues that intimacy is about being able to communicate with the sparest of signs and gestures. Robby’s use of footprints seems to fall within the same territory. He is cautious about not wanting to come on too strongly, and so he uses subtle methods such as leaving a footprint to make his presence felt and his intentions known. Jean Burgess (Citation2006) uses the term ‘vernacular creativity’ to talk about these everyday creative practices on new media where users such as Neel, SweetLuv, Roby and Andy situate their textual and visual strategies to engage in a form of eroticization. This, according to Burgess, reduces cultural distance and creates an affective form of erotic intimacy.

Conclusion

Grindr and PlanetRomeo are constructed as a haven for mostly gay men looking for sex and casual hook-ups with the possibility of finding romance. It is where gay men are going when they are bored, horny and in need of some instant gratification. As my research shows, Grindr and PlanetRomeo are being used by many of my respondents in more ways than just as a way to ‘get off’. The images, texts and footprints circulating here, whether created with the intent to be erotic or leading to an offline encounter, are ‘interpellated within the regime of pornography’ (Tziallas Citation2015, 771). There are different interaction norms and, as we can see, they can be racialized, class-ed and cast-ed. On Grindr we face a constant rotation of bodies and faces updated by users setting up information about themselves but also hinting at what ‘they want’, thus allowing one to participate in objectified media images. Face-to-face contact and offline encounter are not necessarily the end goal of the interaction taking place on these platforms. As I have described earlier (Dasgupta Citation2017, Citation2018, Citation2020), being on queer social media platforms such as Grindr and PlanetRomeo is serious emotional labour – the anxiety, intimacy and sexual tension offer various kinds of possibilities and exclusions. Whilst academics have studied these digital queer spaces in India as potential for activism, community formation and intimacy, the opportunity to see the role played by the circulation of erotic images and texts offer a different lens to understanding gay men’s culture and sexual politics in contemporary India.

Acknowledgements

This paper was presented at the Ashoka University Summer of Ishq Webinar on 14 July 2021. The author would like to thank Prof. Madhavi Menon and Sam McBean for their feedback and conversation. The author would also like to thank Darshana Sreedhar Mini and Anirban K. Baishya for their insightful comments on the drafts that preceded this article which helped clarify much of the author’s argument.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Notes

1 This article draws on the author’s earlier chapter ‘Keep It Classy: Grindr, Facebook and Enclaves of Queer Privilege in India’ in The Routledge Companion to Media and Class edited by Erika Polson, Lynn Schofield-Clark, and Radhika Gajjala (Routledge 2020). This article uses a different argument and narratives.

References

- Albury, Kath, Jean Burgess, Ben Light, Kane Race and Rowan Wilken. 2017. ‘Data Cultures of Mobile Dating and Hook-up Apps: Emerging Issues for Critical Social Science Research.’ Big Data and Society 4 (2): 1–11.

- Berlant, Lauren. 2004. Compassion: The Culture and Politics of an Emotion. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Boyce, Paul and Rohit K. Dasgupta. 2021. ‘Joyraj and Debanuj: Queer(y)ing the City.’ Contemporary South Asia 28 (4): 511–523.

- Burgess, Jean. 2006. ‘Hearing Ordinary Voices: Cultural Studies, Vernacular Creativity and Digital Storytelling.’ Continuum: Journal of Media and Cultural Studies 20 (2): 201–214.

- Campbell, John Edward and Matt Carlson. 2002. ‘Panopticon.com: Online Surveillance and the Commodification of Privacy’. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media 46 (4): 586–606.

- Dasgupta, Rohit K. 2017. Digital Queer Cultures in India: Politics, Intimacies and Belonging. London: Routledge.

- Dasgupta, Rohit K. 2018. ‘Digital Outreach and Sexual Health Advocacy: SAATHII as a Response.’ In Queering Digital India: Activisms, Identities and Subjectivities, edited by Rohit K. Dasgupta and Debanuj Dasgupta, 112–131. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

- Dasgupta, Rohit K. 2020. ‘Keep It Classy: Grindr, Facebook and Enclaves of Queer Privilege in India.’ In The Routledge Companion to Media and Class, edited by Erika Polson, Lynn Schofield-Clark and Radhika Gajjala, 90–98. London: Routledge.

- Jones, Rodney H. 2005. ‘‘You Show me Yours, I’ll Show you Mine’: The Negotiation of Shifts from Textual to Visual Modes in Computer-Mediated Interaction among Gay Men.’ Visual Communication 4 (1): 69–92.

- McGlotten, Shaka. 2013. Virtual Intimacies: Media, Affect and Queer Socialities. Albany: SUNY Press.

- Mercer, John. 2017. Gay Pornography: Representations of Sexuality and Masculinity. London: Bloomsbury.

- Miller, Vincent. 2008. ‘New Media, Networking and Phatic Culture.’ Convergence: The International Journal of Research Into New Media Technologies 14 (4): 387–400.

- Mowlabocus, Sharif. 2010. Gaydar Culture: Gay Men, Technology and Embodiment in the Digital Age. London: Routledge.

- Mowlabocus, Sharif. 2021. ‘A Kindr Grindr: Moderating Race(ism) in Technospaces of Desire.’ In Queer Sites in Global Contexts: Technologies, Spaces and Otherness, edited by Regner Ramos and Sharif Mowlabocus, 33–47. New York: Routledge.

- Paasonen, Susanna, Kylie Jarrett and Ben Light. 2019. NSFW: Sex, Humour and Risk in Social Media. Cambridge: MIT Press.

- Race, Kane. 2018. ‘Towards a pragmatics of sexual media/networking devices.’ Sexualities 21 (8): 1325–1330.

- Sinha, Mrinalini. 1995. Colonial Masculinity: The Manly Englishman and the Effeminate Bengali. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

- Tziallas, Evangelos. 2015. ‘Gamified Eroticism: Gay Male “Social Networking” Applications and Self-Pornography.’ Sexuality & Culture 19: 759–775.