ABSTRACT

The Lioness vibrator is a so-called ‘smart vibrator’, as the vibrator is equipped with biosensors that measure the contractions of the pelvic floor muscles and the intensity of the clitoral motor. The vibrator is sold with the explicit goal for users to learn more about their sexual pleasure. In this article, I will argue that the assumed neutral perspective of knowledge production through datafication can be understood as a phallocentric perspective on sexual pleasure. In the Lioness, this logic can be seen in the way its design privileges quantitative knowledge over qualitative knowledge and logos over pathos while centring penetration and clitoral stimulation. Furthermore, the focus of the Lioness on improving your orgasm turns sexual pleasure into a phallocentric goal-oriented activity. I will show how well-meaning companies using a feminist predicate are unintentionally still privileging phallocentric ways of thinking about sexual pleasure over alterative ways of thinking.

Introduction

Pleasure with a Purpose. Our mission is to empower people to learn more about their own bodies and to break longstanding taboos around sexual pleasure. (‘About | Lioness’ Citationn.d.-a)

Furthermore, the Lioness wants to fill a perceived gap in knowledge about sexual pleasure on a larger scale by providing the option for people to share their data with the Lioness ‘Sex Research Platform’ (Lioness Citationn.d.-c). This Sex Research Platform is part of the Lioness company, and its goal is to learn about the sexual function of ‘anyone with a vagina’ (Lioness Citationn.d.-c). Users of the Lioness vibrator can share their data with the Lioness company, who in turn share the anonymized data with researchers interested in researching female sexuality (Lioness Citationn.d.-c; Mulkerrins Citation2021).Footnote1 Currently, Lioness is working with the non-profit organization Center for Genital Health and Education to research the validity of the Lioness as a research tool (Lioness Citationn.d.-d).

The founders of Lioness, Liz Klinger and Anna Lee, started their company with a crowdfunding campaign on the platform Indiegogo in 2016. Here they promoted the vibrator as a new technology ‘designed by women, for women’, to improve their pleasure (Klinger Citation2016). In 2021, Lioness launched a new version of the vibrator, the ‘Lioness 2.0’ (Lioness Citationn.d.-e). This vibrator ‘provides AI-assisted guidance, based on years of working with Lioness customers […] and incorporating the latest machine-learning developments’ (‘Lioness Launches AI Sex Toy’ Citationn.d.). What this new AI feature means, according to the website, is that the user can see in the app while using the vibrator what ‘likely moments of high arousal and orgasm’ are (Lioness Citationn.d.-e). The analysis in this article will, however, be based on the first version of the vibrator.

The opening quote of this article shows that the mission of Lioness is to empower people to learn about their own pleasure. Until March 2019, however, their mission statement explicitly said to ‘empower women to learn more about their own bodies and to break longstanding taboos around female sexuality’ (‘About | Lioness’ Citationn.d.-b; emphasis added).Footnote2 Sometime between March 2019 and May 2019, the decision was made to use more inclusive language by not addressing ‘women’ but ‘people’.Footnote3 Although this choice of words is more inclusive since people who do not identify themselves as women but do have a vagina are now addressed in the mission statement, there are still some questions that can be asked about the workings of the technology and the knowledge that can be generated with the Lioness vibrator.Footnote4 In this article, I will argue that the feminist claims and inclusive language are not necessarily reflected in the operation, functionality, and epistemic assumptions concerning sexual pleasure of the Lioness vibrator.

In this article, I will first discuss French feminist theory on female sexuality and knowledge production. Here I will discuss Luce Irigaray’s critique of the Freudian theory of sexual development. Irigaray discusses how Freud conceptualizes female sexuality in terms of the man. This leads to an epistemology in which female sexuality can not be anything of itself but is always the absence of the masculine. Referring to the French feminist philosopher Hélène Cixous, I will explain how this way of thinking and generating knowledge can be understood as a ‘phallocentric’ logic. Phallocentric logic can be understood as a way of reasoning and a way of producing knowledge that privileges that which is culturally associated with men and masculinity over that which is culturally associated with women and femininity. Second, to explore the logic underlying the Lioness vibrator regarding sexual pleasure and how sexual pleasure can be known, I will use methodological concepts from critical data studies and postphenomenology. In my analysis, I will understand the pleasure data that are visualized in the Lioness app as constructed and inherently partial (Kitchin Citation2014; Drucker Citation2011). I will draw attention to the constructedness and situatedness of the data and the knowledge that can be generated in relation to the Lioness vibrator. Third, I will analyze a specific relation to the Lioness vibrator and the data visualizations in the Lioness app. Here, I will show how a phallocentric logic underlies the experience of sexual pleasure and the way in which sexual pleasure can be known in relation to the Lioness vibrator.

This article can be placed at the intersection of research on vibrators and sex toys and academic debates regarding the ‘quantified self’ (Lupton Citation2016). The term ‘quantified self’ refers to the phenomenon where people use self-tracking technologies with biosensors to quantify various aspects of their lives with the explicit goal of learning about and improving the self (Lupton Citation2016, 3–4). Research regarding this phenomenon has focused on the history of self-tracking (Crawford, Lingel, and Karppi Citation2015), the way in which people give meaning to self-tracking practices (Sharon and Zandbergen Citation2017), neoliberal implications of quantifying the self (Ajana Citation2017; Moore and Robinson Citation2016), and functionalities and affordances of self-tracking technologies (Bower and Sturman Citation2015; Rapp et al. Citation2015). Furthermore, Deborah Lupton (Citation2015) discusses mobile apps that have been designed for the self-quantification of sexual and reproductive activities in ‘Quantified Sex: A Critical Analysis and Reproductive Self-Tracking Using Apps’. In her research, she finds that the apps ‘support and reinforce highly reductive and normative ideas about what “good sex” and “good performance” is’ (Citation2015, 447). Apps designed specifically for men focus on sexuality as a performance. In these apps, ‘achievements’ such as the number of sexual partners, how often the sex takes place, thrusts, and the duration of intercourse are quantified and can be compared with others (Citation2015, 447). By contrast, apps designed for women emphasize the medicalization and risk of sexuality. These apps focus mainly on mapping fertility, periods, and reproduction (Citation2015, 447). Since the Lioness vibrator and app seem to break with the gendered dichotomy noticed by Lupton, their analysis can be a much-needed contribution to ongoing debates surrounding quantified sex and sexual pleasure.

In addition, this article will contribute to the field of research on sex toys and specifically vibrators. Research to date on vibrators has focused primarily on quantitative research on vibrators and vibrator use (Herbenick et al. Citation2010, Citation2015; Döring and Pöschl Citation2018), the (early) history of the vibrator (Maines Citation1999; King Citation2011; Lieberman Citation2016; Lieberman and Schatzberg Citation2018), the way in which people give meaning to vibrators (Fahs and Swank Citation2013; Lieberman Citation2017; Waskul and Anklan Citation2020), and research on vibrators that starts from a design perspective (Bardzell and Bardzell Citation2011; Eaglin and Bardzell Citation2011; Wilner and Huff Citation2017). This research will contribute by making an original combination of concepts from postphenomenology, critical data studies, and French feminist theory to explore experiences of sexual pleasure and the epistemic assumptions concerning sexual pleasure of the Lioness vibrator.

Phallocentric logic to sexuality

In this section, I will address how, according to feminists like Irigaray and Cixous, the epistemic assumptions concerning sexual pleasure in Western science are the result of knowledge being generated from a masculine position. First, I will discuss how Irigaray demonstrates these masculine assumptions by discussing and criticizing Sigmund Freud’s theory of sexuality (Freud Citation1932). Then, I will develop this criticism through Cixous’ concept of phallocentrism. Finally, I will briefly outline how I will use Irigaray’s criticism of Freud and Cixousian phallocentrism in my analysis of the Lioness vibrator.

In her influential work This Sex Which is Not One, Irigaray explains how Freud theorized that the penis and the clitoris are the same in the younger years of children and that this ‘single identical genital apparatus – the male organ – is fundamental in order to account for the infantile sexual organisation of both sexes’ (Citation1985, 35). When children get older, this ‘identical genital apparatus’ develops into the – active – ‘valued genital organ’ in boys, while in girls, the valued genital organ is not further developed; it is castrated and becomes the – passive – clitoris (Freud Citation1932, 125). As Irigaray summarizes Freud’s view:

the difference between the sexes ultimately cuts back through early childhood, dividing up functions and sexual roles, maleness combines the factors of subject, activity, and possession of the penis; femaleness takes over those of object and passivity and the castrated genital organ. (Irigaray Citation1985, 36)

Relatedly, as boys get older, they will develop castration anxiety, which refers to the fear of losing their valued organ. The girl, who thought she was blessed with having a penis since the genital apparatus was the same in the early years, finds out that it has been taken away from her. The further development of her sexuality, according to Freud, will be characterized by jealousy because her own clitoris is unworthy in comparison to the boy’s sex organ and by penis envy (Freud Citation1932, 125–126; Irigaray Citation1985, 38–39). She will, according to Freud, always yearn for the penis and the attributes associated with the ‘far superior equipment’, namely subjectivity and activity (Freud Citation1932, 126). This longing and jealousy manifest itself in the desire for her father, then the desire for a partner, then the desire for a son, and when she realizes she will never really have the mighty phallus, her subconscious continues to desire it, for example, by wanting to pursue an ‘intellectual profession’ (Citation1932, 125). Irigaray explains that – reasoned from this perspective – she will thus always be lacking. She will always be longing for completeness, to become ‘whole’ as a man. This theorization of Freud about the sexual development of two sexes is the starting point for Irigaray to show how female sexuality cannot be anything of itself since it is understood from a male perspective and in terms of what the woman does not have. The relevance of Irigaray’s explanation and critique of the constitution of sexuality lies in its possibilities for understanding the conceptualization of Western sexuality in general and in the Lioness technology in particular.

Cixous calls this way of thinking, reasoning, and producing knowledge a masculine or phallocentric logic (Bray Citation2004, 7). As a culturally dominant structure in Western philosophy and language, phallocentrism refers to a way of reasoning and thinking that systematically prefers that which is culturally associated with masculinity over that which is culturally associated with femininity. In The Newly Born Woman (1975 French original: La Jeune Née), Cixous explores a few of those differentiations and the way in which the masculine is privileged:

Where is she?

Activity/passivity

Sun/Moon

Culture/Nature

Day/Night

Father/Mother

Head/Heart

Intelligible/Palpable

Logos/Pathos.

[ … ]

Man

Woman

Always the same metaphor: we follow it, it carries us, beneath all its figures, wherever discourse is organised. If we read or speak, the same thread or double braid is leading us throughout literature, philosophy, criticism, centuries of representation and reflection. (Cixous and Clement Citation1986, 63)

As a result of phallocentric logic, simply reversing dichotomies does not resolve the inherent epistemic inequality implied in much of Western culture and science (Cixous and Clement Citation1986). I see the theory of sexual development and a phallocentric way of thinking reflected in the way that the Liberation Movement sought to liberate female sexuality from the myths of passivity and dependency. In Straight Sex: Rethinking the Politics of Pleasure, Lynne Segal (Citation1994) discusses how the Liberation Movement of the late 1960s and early 1970s wanted to tackle women’s repression by questioning the myths of passivity and dependency surrounding female sexuality. The way in which this happened was by asserting the similarity between male and female desire in a ‘no-nonsense, neutral, and scientific’ way (Citation1994, 36):

Now, after the toing and froing of the last 50 years, we can safely say that there is no biological difference between the sexuality of the human female and the human male. The clitoris and the penis respectively are the ‘seat’ of genital release, the orgasm. This release can be brought about by masturbation with or without mechanical stimulators [ … ]. (Segal Citation1994, 36)

Radical alterative pleasure

When Cixous addresses a ‘masculine’ or ‘feminine’ way of thinking, she does not mean anything that is tied to biologically sexed bodies. Cixous is accused by some of essentialism since she uses the same words, namely masculine and feminine ways of thinking and masculine and feminine writing.Footnote5 However, Cixous explicitly warns against falling back, ‘to lapse smugly or blindly into an essentialist ideological interpretation’ (Cixous and Clement Citation1986, 81). Bray explains that we need to understand this usage of the same words as strategic essentialism. Since sexual difference is an ‘infinitely complex matter’, in order to argue against the injustices committed against women (or other Others), it is, according to Cixous, necessary to limit this complexity (Bray Citation2004, 48–49). Or as Cixous states, ‘As women we are at the obligatory mercy of simplification. In order to defend women we are obliged to speak in the feminist terms of “man” and “woman”’ (Bray Citation2004, 49). Cixous, therefore, uses the words of masculine and feminine logic in order to question precisely those terms that are all too commonly used, the opposition of masculinity and femininity (Bray Citation2004, 49). In order to question the limits of phallocentrism and the restriction of meaning, Cixous thinks through sexual difference to ‘rewrite’ those terms and their meanings. When Cixous talks about a feminine way of thinking, of writing, then she means by this a way of thinking in differentiation without hierarchy, without privileging one over the other, and by that keeping the other alive and different.

This leads me to Irigaray’s question of why the feminine sex cannot be discussed or understood in reference to itself: ‘[a]ll Freud’s statements describing feminine sexuality overlook the fact that the female sex might possibly have its own “specificity”’ (Irigaray Citation1985, 69). Here, she does not talk about feminine sexuality as being bound to an ‘essentialist biological female body’. This would fall back into the thinking of oppositions, and that is exactly what has to be questioned. I think it is not the intention of Irigaray and Cixous to ‘capture’ or ‘bound’ sexual pleasure to or as something. This also applies to Irigaray when she discusses sexuality and the body:

Her sexuality, always at least double, even further: it is plural. [ … ] Indeed, woman’s pleasure does not have to choose between clitoral activity and vaginal passivity for example. They each contribute, irreplaceably, to woman’s pleasure. Among other caresses [ … ] woman has sex organs more or less everywhere. She finds pleasure almost anywhere. Even if we refrain from invoking the hystericization of her entire body, the geography of her pleasure is far more diversified, more multiple in its differences, more complex, more subtle, than is commonly imagined – in an imaginary rather too narrowly focused on sameness. (Irigaray Citation1985, 28)

Understanding data and affordances

Data and data visualizations are often presented as a reflection, as something neutral and as something objective, generated from a neutral position (Drucker Citation2011; Kitchin Citation2014; Iliadis and Russo Citation2016; D’Ignazio and Klein Citation2020). Feminist philosopher Donna Haraway calls this the ‘god trick of seeing everything from nowhere’ (Citation1988, 581). Catherine D’Ignazio and Lauren Klein discuss this god trick as the most significant feature of data visualizations:

It’s a ‘trick’ because it makes the viewer believe that they can see everything, all at once, from an imaginary and impossible standpoint [and] it’s [sic] a trick because what appears to be everything, and what appears to be neutral, always what she terms a partial perspective. And in most cases of seemingly neutral visualisations, this perspective is the one of the dominant default group. (D’Ignazio and Klein Citation2020, 76; original emphases)

Data, like knowledge, are generated from a particular point of view. It is this situatedness and non-neutrality of data that I will explore in the epistemic workings of the Lioness.

The etymology of the word ‘data’ can be traced to the Latin dare, meaning ‘to give’ (Kitchin Citation2014, 2). The plural form of datum can therefore be understood as ‘something given’ (Citation2014, 4). The meaning of the word ‘data’ contributes to the idea that data are natural representations of pre-existing phenomena (Drucker Citation2011). The word capta is derived from the Latin capere, meaning to take (Kitchin Citation2014, 2). Understanding information as ‘taken’ communicates how creating information is an active gesture. Understanding data as capta then draws attention to ‘the situated, partial, and constitutive character of knowledge production, the recognition that knowledge is constructed, taken, not simply given as a natural representation of pre-existing fact’ (Drucker Citation2011; original emphasis). However, I will not explicitly call the data and the visualization capta. It is the underlying meaning that data are actively created from a certain point of view, according to a certain logic, that I will use in my analysis. Understanding data as capta draws attention to the constructedness of the data visualizations in the Lioness app and the embedded interpretations and assumptions about sexual pleasure.

In addition, this understanding of data makes it possible to understand how the data are constructed in the relation between the vibrator and the body. An analysis of the Lioness in this way brings to the foreground that the experience that is quantified comes into being in relation to the vibrator. In other words, a specific experience of sexual pleasure comes into being in relation to the material measuring instrument, the vibrator in this case, that mediates its existence. This stems from a postphenomenological understanding of technologies, namely that technological artefacts are not delineated stable things; rather, technological artefacts are multistable (Verbeek Citation2005, 138).

Multistability refers to the idea that all technological artefacts are relative to a context, ‘there are not objects-in-themselves’ (Ihde Citation1996, 32). Technologies can become stable in concrete contexts of use or analysis, and ‘this identity is determined not only by the technology in question but also by the way in which it becomes interpreted’ (Ihde Citation2009, 117). Thus, in order to analyze the workings of the Lioness vibrator, I will assign a stability of a relation to the vibrator.

The specific stability of the Lioness vibrator can be determined based on its technological possibilities understood in terms of ‘affordances’. The concept of affordances was initially coined by the ecologist James Gibson (Citation1986) to refer to the action possibilities in an environment in relation to the animals that live there. Here, affordances are understood to be both relational and functional; affordances frame while not determine the possibilities for action in relation to an object (Hutchby Citation2001, 444). It is the physical properties of a technological artefact that frame while not determine a use in relation to a body. It is on the basis of these affordances that I will determine a stability of the technology.

Understanding the data as capta and using the concept of affordances to determine a stability with the physical vibrator will allow me to analyze in which specific way sexual pleasure comes into being in relation to the Lioness vibrator. Furthermore, this determination of a stability will allow me to analyze what assumptions and interpretations about sexual pleasure are made in the data visualizations in the Lioness app. In combination with the concept of phallocentrism, I will explore the logic that underlies the way in which sexual pleasure can be known in relation to the Lioness vibrator.

Understanding relations to the Lioness vibrator through data visualizations

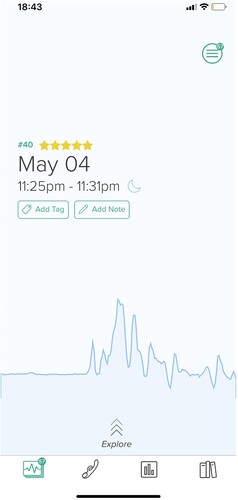

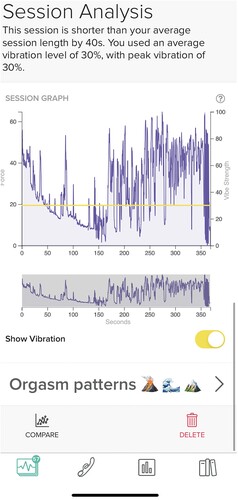

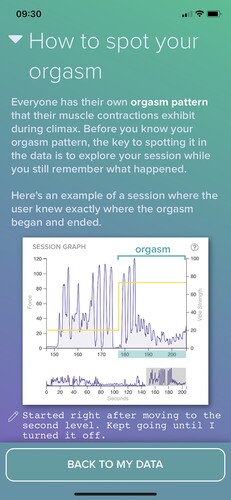

When using the Lioness vibrator, it gathers ‘pleasure data’, which are visualized in the Lioness app. The data visualizations in the Lioness app are presented as a reflection of the user’s arousal and orgasm.Footnote6 Each ‘session’ can be rated, and tags and notes can be added as additional information to the pleasure data (see ). Each individual session is visualized in two different ways: ‘Session Playback’ () and ‘Session Analysis’ (). The first data visualization, which is called the ‘Session Playback’, shows a ‘dynamic circle’ that represents the force of the pelvic floor movement over time. The second visualization, called the ‘Session Analysis’, shows a line graph of the data of the force of the pelvic floor movement over time. In this second visualization, the option is given to show the force of the clitoral stimulator during the session (see the yellow line in ). The force of the clitoral stimulator can be adjusted during use by the user by means of a button on the handle of the vibrator.

For the biosensors to work, and thus to ‘learn’ about your pleasure, the vibrator needs to be vaginally inserted, and the vibrator has to be turned on to start the clitoral stimulator. There are other types of relations that can be formed with the Lioness vibrator, such as anal penetration or no penetration at all. However, in order for the user to ‘learn’ from the data visualizations as intended by the designers, the vibrator has to be vaginally inserted and turned on. The data that are supposed to represent pleasure and the body are thus generated through penetration and clitoral stimulation. The experience that is measured and visualized in the Lioness app is not something before the relation to the vibrator takes place. It is not an a-priori experience of sexual pleasure that can be measured by the biosensors. Rather, together with the measuring instrument, the vibrator, a specific experience and understanding of sexual pleasure comes into being through penetration and clitoral stimulation. This experience of sexual pleasure can be said to follow a phallocentric logic since it follows a reductive understanding of sexual pleasure, where penetration and the stimulation of the clitoris are valued over other experiences of the body. However, this does not necessarily do justice to the plurality or alterity of sexual pleasure that can be experienced.Footnote7 In the words of Irigaray: ‘Her sexuality, always at least double, goes even further: it is plural’ (Citation1985, 28). This ‘plurality of pleasure’ goes beyond just the clitoris and the vagina: ‘woman has sex organs everywhere. She finds pleasure almost anywhere. [ … ] pleasure is far more diversified, more multiple in its differences, more complex, more subtle’ (Citation1985, 28). Sexual pleasure can go much further than ‘the imaginary that is too focused on sameness’. This preference for stimulation of just the clitoris follows a phallocentric logic in Cixousian terms since a hierarchy is made in this specific experience of pleasure where stimulation of the clitoris and penetration is valued over other experiences of the body.

Furthermore, it is this specific experience that comes into being in relation to the vibrator that is quantified in a certain way, namely, by means of the pelvic floor movement. The data visualizations in the Lioness app show the pelvic floor movement over time. It is not pleasure itself that is measured and visualized, but rather the physiological response of the body to the measuring instrument, the physiological response to penetration and clitoral stimulation. The pelvic floor movement is thus used as an indicator for sexual pleasure. Using the pelvic floor movement as an indicator for sexual pleasure implies that pleasure is synonymous with the physiological and genital reaction of the body. This idea, that pleasure is synonymous with the genital response and vice versa, is highly problematic and is criticized in gynaecological, sexological, and feminist research.

Firstly, Caroline Darski et al. (Citation2016) show in ‘Association Between the Functionality of Pelvic floor Muscles and Sexual Satisfaction in Young Women’ that the movement of the pelvic floor muscles cannot be associated with ‘female sexual satisfaction’. Another and instrumentally ‘better’ way to investigate the bodily response to pleasure is through vaginal photoplethysmography. This technique examines the amount of blood in the wall of the vagina. Apart from the fact that this would also be an indicator for pleasure and not pleasure itself, this research technique is, according to Kelly Suschinsky, Lalumière, and Chivers (Citation2009), not fully validated and may not measure sexual arousal specifically. Even more so, Sandra Leiblum and Meredith Chivers discuss in ‘Normal and Persistent Genital Arousal in Women: New Perspectives’ that women ‘can experience genital response in the absence of a subjective experience of sexual arousal’ (Leiblum and Chivers Citation2007, 357). This research shows that genital and bodily reaction or movement is not necessarily synonymous with sexual arousal or pleasure and, even more so, that orgasm can take place without experiencing pleasure.

This leads me to the feminist critique on the idea that orgasm as a physiological function is synonymous with pleasure. This, as Emily Nagoski (Citation2015) explains, is a cultural misconception about female sexuality, whereby women's bodies are thought to indicate what they are aroused by or enjoy, even when this contrasts with what they themselves indicate as subjects. For example, in research measuring the genital response of women and claiming that women are turned on by violent sex, even when they say they are not (Citation2015, 204–205). Nagoski calls this non-concordance research; not investigating what women as subjects say about their arousal and pleasure, but investigating the female body as an object. The ‘pleasure is synonymous with the genital response’ idea is a dangerous narrative about women, their bodies and their sexuality, that is also heavily criticized by gynaecological and psychophysiological research.

Another interpretative act is made in regard to how sexual pleasure can be known. In relation to the Lioness, it is assumed that we need to measure and see pleasure in order to understand it. This implies that the experience of pleasure cannot be known as an embodied experience, but it has to be seen in order to be known. This idea, that it is vision that allows us to understand what is real and true, is criticized by Haraway: ‘[ … ] like the god trick, this eye fucks the world to make techno-monsters’ (Citation1988, 581). In other words, people with a vagina are taught that they can know their pleasure and body through disembodiment, through datafication, through seeing, rather than knowing themselves and their pleasure through embodied experience. The knowing of our body and pleasure is subjected – or should I say objected – to the old Cartesian split, trusting our mind over body. Or to speak in Cixousian terms, trusting logos over pathos.

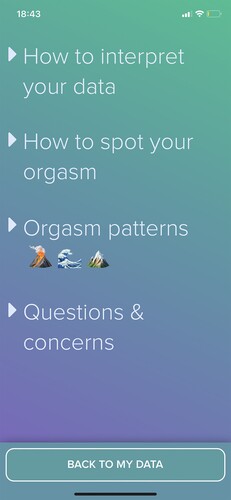

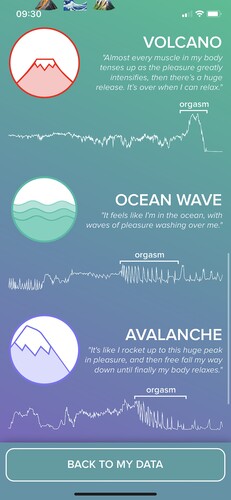

Another interpretative act that is made in the decision of quantifying and visualizing the pelvic floor movement is that the main goal of pleasure is orgasm. The app contains a page where it is explained how the user can read or interpret their data (see , ‘How to interpret your data’). The information on how to understand and interpret the data visualization in the Lioness app is only in relation to how the user can spot their orgasm in the data and the different ‘orgasm patterns’ that may occur. Lioness distinguishes three types of orgasm patterns that the user can look for in their data: a ‘volcano’ pattern, an ‘ocean wave’ pattern, and an ‘avalanche’ pattern (see ). The user can ‘spot’ an orgasm in the data visualization where the frequency of the pelvic floor contraction is higher than during the rest of the session, which can be an indicator for the experience of orgasm (see ). Since this is the only visible change in the data visualization and the only thing a user could discover in their data, this indicates that sexual pleasure would mostly revolve around the experience of orgasm. This turns sexual pleasure into a kind of goal-oriented activity in which the experience of orgasm is valued above other experiences of pleasure. The experience of orgasm is an important part of the experience of sexual pleasure, especially in the context of heterosexual intercourse and the so-called Orgasm Gap. This term refers to a gendered gap in the experience of orgasm, where men experience orgasm more frequently than women in heterosexual intercourse (see, for example, Wade, Kremer, and Brown Citation2005; Mahar, Mintz, and Akers Citation2020). However, my point here is that the focus with the Lioness vibrator does not necessarily lie on experiencing pleasure but on experiencing orgasm, which can be achieved by means of the vibrator.

Conclusion

The feminist claims and inclusive language that Lioness uses on their website are not necessarily reflected in the functionality and epistemic assumptions concerning sexual pleasure of the Lioness vibrator. The interpretative acts that are made in the construction of the data visualization follow a phallocentric logic in regard to sexual pleasure. In this article, I have analyzed a specific relation to the Lioness vibrator based on an affordance analysis. First, the way in which the experience of sexual pleasure comes into being in this specific relation can be said to follow a phallocentric logic where penetration and the stimulation of the clitoris are valued over other experiences of the body. Second, interpretative acts are made in regard to how sexual pleasure can be known, where it creates a false and dangerous idea that the genital response is synonymous with sexual pleasure and where ratio is valued over knowing as an embodied process. Third, through the Lioness, pleasure is made into a goal-oriented activity, namely, orgasm.

In this article, I have not addressed the neoliberal implications of quantifying and improving one’s sexual pleasure. The Lioness vibrator can be understood within movements such as the Quantified Self, where more and more people are quantifying more and more aspects of their lives with the goal of improving those various aspects (Lupton Citation2016). For example, Btihaj Ajana discusses the way in which such practices of management and monitoring techniques ‘echo the ethos of neoliberalism’ whereby ‘individuals are increasingly expected to be in charge of their own health and wellbeing’ (Citation2017, 4). It might be interesting to explore in what way sexuality and sexual pleasure are also becoming part of this ‘biopolitics of the self’, where the body comes under increasing scrutinization, management, and improvement. In addition, as I discussed in the Introduction, as a user you get the option to share your data with the Lioness Sex Research Platform. Regardless of the importance of research on pleasure and vaginas, the data appear to be used by the Lioness to develop their own products. It seems that the Lioness 2.0 is improved based on the data of customers. The Lioness 2.0 ‘provides AI-assisted guidance, based on years of working with Lioness customers […] and incorporating the latest machine-learning developments’ (‘Lioness Launches AI Sex Toy’ Citationn.d.). I wonder to what extent we can understand this in terms of free, sexual ‘digital labor’, where the people who bought and use the vibrator are doing free work for the improvement of Lioness products (Fuchs Citation2014).

I wholeheartedly concur with the Lioness mission statement that they want to fill the gap in research on pleasure. What I have shown in this article is that there are ways of thinking about sexual pleasure and producing knowledge that is ingrained in our discourses, technologies, and datafication. Ways of thinking where certain parts of the body are preferred over others, where certain actions are preferred over others, and where certain types of knowledge are preferred over others. In addition, I do not mean to imply that penetration, clitoral stimulation, and orgasm should not play a role in the experience of sexual pleasure. The purpose of this article is a move towards thinking, knowing, and experiencing sexual pleasure – also in relation to technologies – in a radically alterative way.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Notes

1 Their first and latest study is a report on how the COVID-19 pandemic has changed sex lives according to their data sets (see Lioness Citationn.d.-b).

2 I entered previous versions of their webpage through the Wayback Machine. The Way Back Machine is a digital archive of webpages (‘Wayback Machine’ n.d.).

3 In the article ‘A Vibrator Developed After Analyzing over 30,000 Orgasms is like a Fitbit for Sexual Pleasure’ in Business Insider, Klinger talks about ‘womxn-centric pleasure’ (López Citation2020). This term can be understood as a more inclusive term than woman or women.

4 While it is technically and physically possible to use the Lioness vibrator anally, the pleasure data consist of the measurement of the pelvic floor movement over time combined with the clitoral stimulator. This can indicate that this vibrator and the knowledge that can be gained with this vibrator are designed for people with vaginas.

5 For an overview of these critiques, see Bray (Citation2004, 13–42).

6 For this article I am using the app version 1.4.23.

7 The philosophical work of Irigaray on the plurality is corroborated by several studies in sexology (see, for example, Nummenmaa et al. Citation2016; Younis, Fattah, and Maamoun Citation2016; Maister et al. Citation2020).

References

- ‘About | Lioness’. n.d.-a. Accessed March 8, 2021. https://web.archive.org/web/20190522031545/https://lioness.io/pages/about.

- ‘About | Lioness’. n.d.-b. Accessed March 7, 2021. https://web.archive.org/web/20190319211618/https://lioness.io/pages/about.

- Ajana, Btihaj. 2017. ‘Digital Health and the Biopolitics of the Quantified Self.’ Digital Health 3: 1–18.

- Atack, Margaret, and Susan Sellers. 1998. ‘Hélène Cixous Reader.’ The Modern Language Review 93 (1): i–232.

- Bardzell, Jeffrey and Shaowen Bardzell. 2011. ‘Pleasure Is Your Birthright: Digitally Enabled Designer Sex Toys as a Case of Third-Wave HCI.’ Proceedings of the 2011 Annual Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems: 257-66.

- Bower, Matt and Daniel Sturman. 2015. ‘What Are the Educational Affordances of Wearable Technologies?’ Computers & Education 88: 343–353.

- Bray, Abigail. 2004. Hélène Cixous: Writing and Sexual Difference. Hampshire and New York: Macmillan International Higher Education.

- Cixous, Hélène and Catherine Clement. 1986. The Newly Born Woman. Translated by Betsy Wing. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Crawford, Kate, Jessa Lingel and Tero Karppi. 2015. ‘Our Metrics, Ourselves: A Hundred Years of Self-Tracking from the Weight Scale to the Wrist Wearable Device.’ European Journal of Cultural Studies 18 (4–5): 479–496.

- Darski, Caroline, Lia Janaina Ferla Barbosa, Luciana Laureano Paiva and Adriane Vieira. 2016. ‘Association Between the Functionality of Pelvic Floor Muscles and Sexual Satisfaction in Young Women’. Revista Brasileira de Ginecologia e Obstetrícia 38: 164–169.

- D’Ignazio, Catherine and Lauren F. Klein. 2020. Data Feminism. Strong Ideas Series. Cambridge: The MIT Press.

- Döring, Nicola and Sandra Pöschl. 2018. ‘Sex Toys, Sex Dolls, Sex Robots: Our Under-Researched Bed-Fellows.’ Sexologies 27 (3): e51–e55.

- Drucker, Johanna. 2011. ‘Humanities Approaches to Graphical Display.’ Digital Humanities Quarterly 005 (1).

- Eaglin, Anna and Shaowen Bardzell. 2011. ‘Sex Toys and Designing for Sexual Wellness.’ In Proceedings of the 2011 Annual Conference Extended Abstracts on Human Factors in Computing Systems: 1837-42.

- Fahs, Breanne and Eric Swank. 2013. ‘Adventures with the ‘Plastic Man': Sex Toys, Compulsory Heterosexuality, and the Politics of Women’s Sexual Pleasure.’ Sexuality & Culture 17 (4): 666–685.

- Freud, Sigmund. 1932. The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud. Edited by James Strachey. London: The Hogarth Press.

- Fuchs, Christian. 2014. Digital Labour and Karl Marx. New York: Routledge.

- Gibson, James J. 1986. The Ecological Approach to Visual Perception. New York: Psychology Press.

- Gill, Rosalind. 2008. ‘Empowerment/Sexism: Figuring Female Sexual Agency in Contemporary Advertising.’ Feminism & Psychology 18 (1): 35–60.

- Haraway, Donna. 1988. ‘Situated Knowledges: The Science Question in Feminism and the Privilege of Partial Perspective.’ Feminist Studies 14 (3): 575–599.

- Herbenick, Debby, Kathryn J. Barnhart, Karly Beavers and Stephanie Benge. 2015. ‘Vibrators and Other Sex Toys Are Commonly Recommended to Patients, But Does Size Matter? Dimensions of Commonly Sold Products.’ The Journal of Sexual Medicine 12 (3): 641–645.

- Herbenick, Debby, Michael Reece, Stephanie A. Sanders, Brian Dodge, Annahita Ghassemi and J. Dennis Fortenberry. 2010. ‘Women’s Vibrator Use in Sexual Partnerships: Results from a Nationally Representative Survey in the United States.’ Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy 36 (1): 49–65.

- Hutchby, Ian. 2001. ‘Technologies, Texts and Affordances.’ Sociology 35 (2): 441–456.

- Ihde, Don. 1996. Technology and the Lifeworld: From Garden to Earth. The Indiana Series in the Philosophy of Technology. Bloomington.: Indiana University Press.

- Ihde, Don. 2009. Postphenomenology and Technoscience: The Peking University Lectures. Series in the Philosophy of the Social Sciences. Albany: SUNY Press.

- Iliadis, Andrew and Federica Russo. 2016. ‘Critical Data Studies: An Introduction.’ Big Data & Society 3 (2): 1-7.

- Irigaray, Luce. 1985. This Sex Which Is Not One. Translated by Catherine Porter and Carolyn Burke. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

- King, Helen. 2011. ‘Galen and the Widow: Towards a History of Therapeutic Masturbation in Ancient Gynaecology.’ EuGeStA: Journal on Gender Studies in Antiquity 1: 205–235.

- Kitchin, Rob. 2014. The Data Revolution: Big Data, Open Data, Data Infrastructures and Their Consequences. Thousand Oaks: SAGE.

- Klinger, Liz. 2016. ‘Lioness Smart Vibrator: Literally See Your Orgasms.’ Indiegogo. Accessed March 7, 2021. https://www.indiegogo.com/projects/1627925.

- Klinger, Liz. 2020. ‘Join the Lioness Sex Research Platform’. Lioness. Accessed March 7, 2021. https://lioness.io/blogs/front-page-news/lioness-launches-sex-research-platform.

- Leiblum, Sandra R. and Meredith L. Chivers. 2007. ‘Normal and Persistent Genital Arousal in Women: New Perspectives.’ Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy 33 (4): 357–373.

- Lieberman, Hallie. 2016. ‘Selling Sex Toys: Marketing and the Meaning of Vibrators in Early Twentieth-Century America.’ Enterprise & Society 17 (2): 393–433.

- Lieberman, Hallie. 2017. ‘Intimate Transactions: Sex Toys and the Sexual Discourse of Second-Wave Feminism.’ Sexuality & Culture 21 (1): 96–120.

- Lieberman, Hallie and Eric Schatzberg. 2018. ‘A Failure of Academic Quality Control: The Technology of Orgasm.’ Journal of Positive Sexuality 4 (2): 24–47.

- Lioness. n.d.-a. ‘✨ How Lioness Smart Vibrator Works ✨ | Literally *see* Your Own Orgasm’. Lioness. Accessed August 31, 2021a. https://lioness.io/pages/how-it-works

- Lioness. n.d.-b. ‘How Has the COVID-19 Pandemic Changed Our Sex Lives?’ Lioness. Accessed August 30, 2021b. https://lioness.io/blogs/sex-guides/how-has-the-covid-pandemic-changed-our-sex-lives

- Lioness. n.d.-c. ‘Lioness Sex Research Platform.’ Lioness. Accessed August 23, 2021. https://lioness.io/pages/lioness-research-platform

- Lioness. n.d.-d. ‘Pelvic Floor Muscles, Orgasm, And Device Validation.’ Lioness. Accessed August 23, 2021. https://lioness.io/pages/upcoming-studies-general

- Lioness. n.d.-e. ‘The Lioness Vibrator 2.0.’ Lioness. Accessed January 18, 2022. https://lioness.io/products/the-lioness-vibrator

- ‘Lioness Launches AI Sex Toy, Finalist for Award at CES.’ n.d. CES 2021: Lioness. Accessed March 8, 2021. http://ces.vporoom.com/Lioness/Lioness-Launches-AI-Sex-Toy-Finalist-for-Award-at-CES.

- López, Canela. 2020. ‘A Vibrator Developed after Analysing over 30,000 Orgasms Is like a Fitbit for Sexual Pleasure.’ Insider. Accessed March 8, 2021. https://www.businessinsider.nl/vibrator-finalist-for-tech-award-sex-toy-2020-1/?international = true&r = US.

- Lupton, Deborah. 2015. ‘Quantified Sex: A Critical Analysis of Sexual and Reproductive Self-Tracking Using Apps.’ Culture, Health & Sexuality 17 (4): 440–453.

- Lupton, Deborah. 2016. The Quantified Self: A Sociology of Self-tracking. Malden: Polity Press.

- Mahar, Elizabeth A., Laurie B. Mintz and Brianna M. Akers. 2020. ‘Orgasm Equality: Scientific Findings and Societal Implications.’ Current Sexual Health Reports 12 (1): 24–32.

- Maines, Rachel P. 1999. The Technology of Orgasm: ‘hysteria,’ the Vibrator, and Women’s Sexual Satisfaction. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Maister, Lara, Aikaterini Fotopoulou, Oliver Turnbull and Manos Tsakiris. 2020. ‘The Erogenous Mirror: Intersubjective and Multisensory Maps of Sexual Arousal in Men and Women.’ Archives of Sexual Behavior 49 (8): 2919–2933.

- Moore, Phoebe and Andrew Robinson. 2016. ‘The Quantified Self: What Counts in the Neoliberal Workplace.’ New Media & Society 18 (11): 2774–2792.

- Mulkerrins, Jane. 2021. ‘Will a ‘Smart’ Vibrator Revolutionise Female Pleasure?’ The Times. Accessed August 30, 2021. https://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/will-a-smart-vibrator-revolutionise-female-pleasure-ttmff9792.

- Nagoski, Emily. 2015. Come as You Are: The Surprising New Science That Will Transform Your Sex Life. New York: Simon and Schuster.

- Nummenmaa, Lauri, Juulia T. Suvilehto, Enrico Glerean, Pekka Santtila and Jari K. Hietanen. 2016. ‘Topography of Human Erogenous Zones.’ Archives of Sexual Behavior 45 (5): 1207–1216.

- Rapp, Amon, Federica Cena, Judy Kay, Bob Kummerfeld, Frank Hopfgartner, Till Plumbaum and Jakob Eg Larsen. 2015. ‘New Frontiers of Quantified Self: Finding New Ways for Engaging Users in Collecting and Using Personal Data.’ Adjunct Proceedings of the 2015 ACM International Joint Conference on Pervasive and Ubiquitous Computing and Proceedings of the 2015 ACM International Symposium on Wearable Computers: 969–72.

- Rome, Alexandra S. and Aliette Lambert. 2020. ‘(Wo)Men on Top? Postfeminist Contradictions in Young Women’s Sexual Narratives.’ Marketing Theory 20 (4): 1–25.

- Segal, Lynne, ed. 1994. Straight Sex: Rethinking the Politics of Pleasure. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Sharon, Tamar and Dorien Zandbergen. 2017. ‘From Data Fetishism to Quantifying Selves: Self-Tracking Practices and the Other Values of Data.’ New Media & Society 19 (11): 1695–1709.

- Suschinsky, Kelly D., Martin L. Lalumière and Meredith L. Chivers. 2009. ‘Sex Differences in Patterns of Genital Sexual Arousal: Measurement Artifacts or True Phenomena?’ Archives of Sexual Behavior 38 (4): 559–573.

- Verbeek, Peter-Paul. 2005. What Things Do: Philosophical Reflections on Technology, Agency, and Design. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press.

- Wade, Lisa D., Emily C. Kremer and Jessica Brown. 2005. ‘The Incidental Orgasm: The Presence of Clitoral Knowledge and the Absence of Orgasm for Women.’ Women & Health 42 (1): 117–138.

- Waskul, Dennis and Michelle Anklan. 2020. ‘ “Best Invention, Second to the Dishwasher”: Vibrators and Sexual Pleasure.’ Sexualities 23 (5-6): 849–875.

- Wilner, Sarah J. S. and Aimee Dinnin Huff. 2017. ‘Objects of Desire: The Role of Product Design in Revising Contested Cultural Meanings.’ Journal of Marketing Management 33 (3–4): 244–271.

- Younis, Ihab, Menhaabdel Fattah and Marwa Maamoun. 2016. ‘Female Hot Spots: Extragenital Erogenous Zones.’ Human Andrology 6 (1): 20–26.