ABSTRACT

Adjective ordering preferences have been addressed by theoretical and empirical studies. Some accounts propose that the distance of an adjective from the head noun depends on its semantic/conceptual features such as subjectivity. Subjectivity has been observed to reliably predict adjective ordering cross-linguistically, albeit with variation in strength. We propose that cross-linguistic variation might stem from lexical factors, which might operate differently in pre- and post-nominal languages. Frequency, for example, may affect ordering linearly with frequent words appearing earlier in the string, rather than based on distance from the noun. Our study aimed at examining this hypothesis, using a binary forced-choice task contrasting two adjective orders in a post-nominal language (i.e. Hebrew). Our results suggest that subjectivity is indeed a strong predictor for ordering preferences, but its effect interacts with lexical factors. Our findings highlight the importance of studying a diversity of languages, where linguistic phenomena might manifest differently.

Introduction

Ordering of adjectives in noun phrases modified by multiple adjectives has been widely studied (Cinque, Citation1994; Dixon, Citation1982; Martin, Citation1969; Scontras et al., Citation2017, Citation2020; Scott, Citation2002; Sproat & Shih, Citation1991; Svenonius, Citation2008), showing robust adjective ordering preferences (AOP), within and between languages (Sproat & Shih, Citation1991). For example, colour adjectives are preferred closer to the noun than size adjectives. Furthermore, it has been argued that AOP in post-nominal languages, where adjectives linearly follow the head noun, mirror the ones in pre-nominal languages, where adjectives precede the noun (Cinque, Citation1994; Sproat & Shih, Citation1991).

According to some accounts, AOP are constrained by the semantic/conceptual features of adjectives, such as absoluteness, availability, inherentness or subjectivity (Hetzron, Citation1978; Martin, Citation1969; Schriefers & Pechmann, Citation1988; Scontras et al., Citation2017; Stavrou, Citation1999; Whorf, Citation1945). These accounts pose that the more absolute/inherent/objective an adjective is, the closer it should be to the noun. For example, colour adjectives are more absolute/inherent/objective than size adjectives, and therefore should be closer to the noun.

The definitions of these conceptual constructs may be intuitive, but some are hard to operationalise (e.g. Martin, Citation1969). In the current study, we used the conceptual factor of subjectivity, defined as the degree to which interpretation is dependent on perspective (Langacker, Citation1990). This factor is evaluated by the faultless disagreement task (Barker, Citation2013; Kennedy, Citation2013; Kölbel, Citation2004; MacFarlane, Citation2014; See Scontras et al., Citation2017, for a robust correlation with explicit subjectivity rating). In this task, participants see dialogues in which two speakers disagree regarding an object’s feature. Participants are asked to assess the likelihood of both speakers being correct, despite being in complete disagreement. This likelihood is proportionate to subjectivity because the more subjective a feature is, the more likely it is to be experienced differently by different people. Using this task, previous empirical research has found subjectivity to be a highly reliable predictor of AOP cross-linguistically (Scontras et al., Citation2020), with some variation in the strength of this connection.

Trainin and Shetreet (Citation2021) observed variation in AOP, with weaker preferences in Hebrew (a post-nominal language) compared with English (a pre-nominal language). Furthermore, we found that in some semantic-class pairings, the ordering preferences in Hebrew did not mirror those of English, unlike theoretical hypotheses (Shlonsky, Citation2004). Note that empirical evidence suggests that subjectivity reliably predicts the AOP in Hebrew similarly to English (Scontras et al., Citation2020). We therefore assumed that other factors interacted with this conceptual factor, focusing on lexical factors. Our previous study used size, colour, and pattern adjectives, where pattern adjectives were preferred farthest from the noun by Hebrew speakers. Interestingly, these adjectives were less frequent and longer relatively to the size and colour ones.

Therefore, our assumption here is that frequency and length operate linearly cross-linguistically, rather than as a function of the distance from the noun (Berg, Citation2018). This assumption is also based on the observation that frequent words are accessed more quickly than infrequent words (Bock, Citation1982; Rayner & Duffy, Citation1986), and therefore are likely to appear earlier. If so, in pre-nominal languages, the more frequent, accessible, words should appear earlier in the adjective sequence, which is farther from the noun. The reversed pattern is assumed in post-nominal languages, as the more frequent words appear earlier in the phrase, but here this means closer to the noun. Similarly, shorter words tend to precede longer ones (Wulff, Citation2003). If so, shorter adjectives should appear farther from the noun in pre-nominal languages, but closer to the noun in post-nominal languages.

Previous empirical research indeed suggests that lexical factors, such as frequency and length, play a role in determining AOP (Kotowski, Citation2016; Scontras et al., Citation2017; Trotzke & Wittenberg, Citation2019; Wulff, Citation2003).Footnote1 Yet, to our knowledge, the effect of lexical factors was not empirically tested in post-nominal languages. Moreover, to our knowledge, the statistical interactions between such factors and semantic/conceptual factors have not been investigated so far (although see Leivada and Westergaard (Citation2019) for length manipulation in Greek). This is important because it is not clear whether various factors operate in the same manner.

The current study was designed to quantitatively test the interacting effects of a conceptual factor (subjectivity) and lexical factors (frequency, length) on AOP in a post-nominal language (Hebrew). We hypothesise that subjectivity will be the main determinant of AOP in Hebrew, but that this effect will be smaller in cases where the lexical and conceptual factors are assumed to operate in different directions than when this conflict is absent.

Materials and methods

Participants

Eighty native, self-reported monolingual Hebrew speakers (18-41 years old, M = 26.025; 52.5% females) who reported no cognitive impairments/learning difficulties participated in the study. All gave informed consent. This study was approved by the TAU ethics committee (#0000759).

Materials and procedure

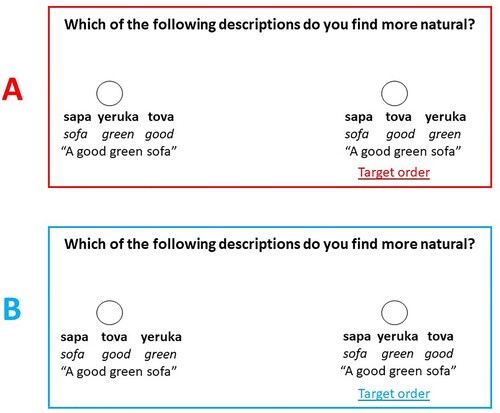

Participants performed a binary forced-choice task. On each trial, they saw pairs of nouns modified by 2 adjectives differing only in their adjective ordering (). Participants were requested to choose the description they found more natural. We did not include visual stimuli to avoid effects of visual salience. We used adjectives from 5 semantic classes (Colour, Opinion, Shape, Size, Texture) in all 10 possible pairings, with several items differing in subjectivity, frequency, and length. Each participant saw 6 trials per pairing (60 trials in total). To avoid low-quality data, we included 6 catch-trials with one ungrammatical description (i.e. the noun preceded the adjectives, which is disallowed in Hebrew). The order of presentation was counterbalanced within each semantic-class pairing across-items and within-items across participants ().

Predictors

Subjectivity, frequency, and length were collected per-item. Per-item subjectivity was measured using a pre-test implementing the faultless disagreement task, in which participants read a dialogue between two characters arguing about one semantic class of a certain object (e.g. Speaker A: “This ball is soft”; Speaker B: “This ball is not soft”). Participants were required to rate, on a visual-analog scale, how possible it was for both speakers to be correct. The higher the rating, the more subjective the description was. To avoid variation that depends on specific noun-adjective pairings, we collected subjectivity ratings per-pairing (and not per-adjectiveFootnote2 as was done by Scontras et al., Citation2017). Frequency (per million) was obtained from the heTenTen14 Hebrew corpus on Sketch-engine (Kilgarriff et al., Citation2014), and length was defined as the number of letters of each adjective.

Analysis

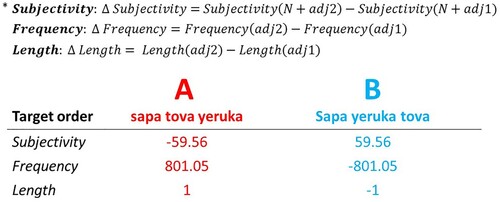

Because AOP in Hebrew are relatively weak, it is not trivial to define the “correct” target response. To allow for model-fitting, we used an arbitrary criterion such that the noun phrase appearing on the right side of the screen was always the target response. Each independent factor was defined as the difference between the measures (delta) of the second adjective and the first adjective of the target response ().

Results

To exclude inattentive participants, we used items in which one description was selected above 80% of the cases. These were classified as “Robust items". We excluded participants who did not select the more frequently-selected description in these items at least 75% of the times. This exclusion criterion led to the exclusion of 14 participants, such that 66 participants were included in the final analysis.Footnote3

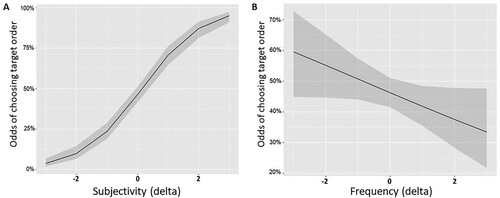

A mixed-effects logistic regression model was fitted, using the “lme4” package (Bates et al., Citation2015) in the R environment (R Core Team, Citation2021) to predict the odds of selecting the target order by subjectivity, frequency, and length (including interactions; ) as fixed effects, and random effects by participants and items. The model summarised below is the maximal model that converged without singularity issues. This model revealed a significant effect of subjectivity (p < 0.001; A), along with a marginally significant effect of frequency (p = 0.082; B).

Figure 3. Odds of choosing the target order (see ) by delta-subjectivity (A) and by delta-frequency (B) (see ). Numbers on the x-axis represent standard deviations from the mean.

Table 1. Estimates of the logistic mixed-effects regression model: Target_response_ selections∼Subjectivity*Frequency* Length + (1 + Subjectivity|Participant) + (1|item).

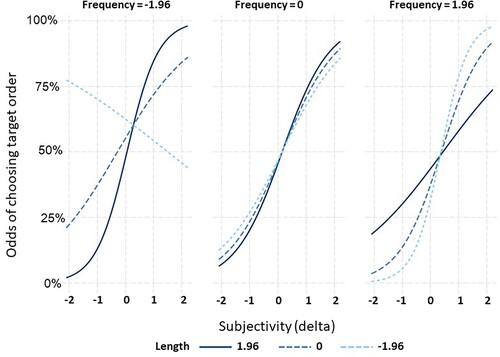

Finally, the model revealed a significant three-way interaction between subjectivity, frequency, and length (p = 0.028; ). Simple slopes analysis using the “interactions" package (Long, Citation2021) revealed that in the most positive delta frequency values (1.96 SD above the mean), given high values of delta length (1.96 SD above the mean), increasing levels of delta subjectivity did not increase the odds of target selection (p = 0.39, ). This was also true when delta frequencies and delta lengths were extremely negative (1.96 SD below the mean; p = 0.44, ). This means that when the second adjective in the sequence was longer and more frequent, or shorter and less frequent, subjectivity did not reliably predict target order selections. In all other cases, subjectivity reliably predicted target order selections, such that higher levels of delta subjectivity increased the odds of selecting the target order, indicating that in most cases, preferred orders are the ones in which the second adjective is more subjective than the first one.

Figure 4. Odds of choosing the target order by delta subjectivity, in varying levels of delta frequency (left, middle, and right panels) and length (different line types). Numbers on the x-axis and in panel headers represent standard deviations from the mean.

Additionally, to relate our results with previous studies, we conducted a separate analysis similar to Scontras et al. (Citation2017), which was the first to empirically manipulate Subjectivity as a predictor of AOP. In this analysis, the proportions of selections of each adjective-pairing, rather than individual pairs, were predicted by the same factors. This analysis yielded similar results. Because this analysis is based on fewer data and we consider it to be less sensitive, it is reported in the supplementary materials.

Discussion

This study examined the role that subjectivity, frequency, and length play in determining AOP in Hebrew. Like other studies testing pre-nominal languages, our results from a post-nominal language clearly demonstrate that subjectivity is the most reliable determinant of AOP (for a theoretical discussion on the importance of subjectivity in AOP, see Scontras et al., Citation2019). In all but the extreme differences in frequency and length between the adjectives, subjectivity reliably predicted target order choices. This shows that subjective adjectives are preferred farther from the noun. These results are in line with previous cross-linguistic empirical studies (Scontras et al., Citation2020).

Frequency seems to contribute to AOP, as seen in its marginal effect, along with the significant interaction in the main analysis which also supports this trend (discussed below), and the analysis reported in the supplementary materials, where the frequency effect was significant. In line with our assumption, more frequent adjectives tended to be preferred in the first adjective position, which is the closest to the noun in Hebrew. This trend goes in the opposite direction than in pre-nominal languages, where more frequent adjectives appeared in the first position which is farther from the noun (Scontras et al., Citation2017; Wulff, Citation2003). This offers a possible explanation for the difference in the strength of preferences cross-linguistically, as shown in Trainin and Shetreet (Citation2021). In pre-nominal languages, the effects of subjectivity and frequency correspond, because “far” with respect to the noun (for subjectivity) coincides with “early” in the adjectival linear sequence (for frequency), and using either factor will result in the same order. In post-nominal languages, like Hebrew, subjectivity and frequency contrast. Thus, speakers of post-nominal languages could sometimes adhere to the frequency constraint, rather than to the dominant conceptual ones, resulting in variation in adjective order. We urge the reader to interpret this hypothesis carefully, because this effect was only marginally significant in the main analysis (although significant in the supplementary analysis).

The significant three-way interaction between subjectivity, frequency, and length suggests that subjectivity accounts for AOP in the vast majority of cases. However, when adjectives are at the extremes of the frequency and length distributions, exceptions occur.Footnote4 This interaction could also explain the differences between Hebrew and English shown in Trainin and Shetreet (Citation2021). There, pattern adjectives were preferred farthest from the noun in Hebrew. These adjectives were always longer and much less frequent than the colour and size adjectives, both in English and in Hebrew. That is, this case may belong to the exceptional cases at the extremes of the distribution where subjectivity “fails" in predicting the order. If so, speakers may have to resort to the lexical constraint. As explained above, Hebrew and English speakers’ preferences are expected to vary because of the differences in linearity. That is, speakers would prefer the infrequent words in the last position, which means farther from the noun in Hebrew, but closer to the noun in English.

Overall, our study has three major implications. First, our findings reinforce the importance of subjectivity in determining adjective order preferences, in line with previous empirical findings (Scontras et al., Citation2017, Citation2020). Second, these findings seem to suggest that although the effects of the lexical factors we examined play second fiddleto subjectivity in determining adjective ordering, they should be factored in, together with the interactions between them. Finally, our findings stress the importance of fine-grained cross-linguistic research. Although subjectivity plays a role in many languages (Scontras et al., Citation2020), other factors contribute differently to cross-linguistic variation. Moreover, because subjectivity varies within each semantic class, our results can begin to explain why universals based on semantic-class hierarchy sometimes fail (Leivada & Westergaard, Citation2019).

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (198.9 KB)Acknowledgments

The authors would also like to thank Gregory Scontras for his insightful and helpful comments.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 We would like to refer the reader to a debate in the literature on phrase-planning (e.g., Fenk-Oczlon, Citation1989; Ferreira, Citation1996; Pickering & Ferreira, Citation2008) concerning which factors influence the linear order of production, including semantic, structural and lexical factors.

2 For example, “sapaN yerukaAdj” had a subjectivity rating of 34.17, and “magevetN yerukaAdj” had a subjectivity rating of 22.63. The average subjectivity rating for the adjective “yeruka” was 27.12.

3 To verify that our exclusion procedure did indeed improve the model’s fit, we compared between the model’s fit on the data from all participants and the model’s fit on the excluded data. Because these datasets differ in length, we compared between the models’ Akaike Information Criteria (Akaike, Citation1974), and showed that the model’s fit with the excluded data was significantly better.

4 Also see Scontras et al. (Citation2017) where there were some cases in which subjectivity failed to predict naturalness ratings. Interestingly, these words were longer than most of the others. Therefore, it is possible that this interaction is also relevant for pre-nominal languages.

References

- Akaike, H. (1974). A new look at the statistical model identification. IEEE Transactions on Automatic Control, 19(6), 716–723. https://doi.org/10.1109/TAC.1974.1100705

- Barker, C. (2013). Negotiating taste. Inquiry, 56(2-3), 240–257. https://doi.org/10.1080/0020174X.2013.784482

- Bates, D., Mächler, M., Bolker, B., & Walker, S. (2015). Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. Journal of Statistical Software, 67(1), 1–48. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v067.i01

- Berg, T. (2018). Frequency and serial order. Linguistics, 56(6), 1303–1351. https://doi.org/10.1515/ling-2018-0023

- Bock, J. K. (1982). Toward a cognitive psychology of syntax: Information processing contributions to sentence formulation. Psychological Review, 89(1), 1. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.89.1.1

- Cinque, G. (1994). On the Evidence for Partial N-movement in the Romance DP. In G. Cinque, J. Koster, J. Y. Pollock, L. Rizzi, & R. Zanuttini (Eds.), Paths towards universal grammar (pp. 85–110). Georgetown University Press.

- Dixon, R. M. (1982). Where have all the adjectives gone? and other essays in semantics and syntax, 107. de Gruyter.

- Fenk-Oczlon, G. (1989). Word frequency and word order in freezes. Ling, 27(3), 517–556. https://doi.org/10.1515/ling.1989.27.3.517

- Ferreira, V. S. (1996). Is It Better to Give Than to Donate? Syntactic Flexibility in Language Production. Journal of Memory and Language, 35(5), 724–755. https://doi.org/10.1006/jmla.1996.0038

- Hetzron, R. (1978). On the relative order of adjectives. In H. Seiler (Ed.), Language universals. Papers from the conference held at Gummersbach/Cologne, Germany, October 3-8, 1976 (pp. 165–184). Narr.

- Kennedy, C. (2013). Two sources of subjectivity: Qualitative assessment and dimensional uncertainty. Inquiry, 56(2-3), 258–277. https://doi.org/10.1080/0020174X.2013.784483

- Kilgarriff, A., Baisa, V., Bušta, J., Jakubíček, M., Kovář, V., Michelfeit, J., Rychlý, P., & Suchomel, V. (2014). The sketch engine: Ten years on. Lexicography, 1(1), 7–36. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40607-014-0009-9

- Kölbel, M. (2004). III*—Faultless Disagreement. Proceedings of the Aristotelian Society, 104(1), 53–73. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0066-7373.2004.00081.x

- Kotowski, S. (2016). Adjectival modification and order restrictions. In The influence of temporariness on prenominal word order. Berlin, Boston: De Gruyter.

- Langacker, R. W. (1990). Subjectification. Cognitive Linguistics, 1(1), 5–38. https://doi.org/10.1515/cogl.1990.1.1.5

- Leivada, E., & Westergaard, M. (2019). Universal linguistic hierarchies are not innately wired. Evidence from multiple adjectives . PeerJ, 7, e7438. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.7438

- Long, J. A. (2021). interactions: Comprehensive, User-Friendly Toolkit for Probing Interactions (1.1.5). https://CRAN.Rproject.org/package=interactions

- MacFarlane, J. (2014). Assessment sensitivity. Clarendon.

- Martin, J. E. (1969). Semantic determinants of preferred adjective order. Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behavior, 8(6), 697–704. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-5371(69)80032-0

- Pickering, M. J., & Ferreira, V. S. (2008). Structural priming: a critical review. Psychological bulletin, 134(3), 427.

- Rayner, K., & Duffy, S. A. (1986). Lexical complexity and fixation times in reading: Effects of word frequency, verb complexity, and lexical ambiguity. Memory & Cognition, 14(3), 191–201. https://doi.org/10.3758/BF03197692

- R Core Team. (2021). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing. https://www.R-project.org/.

- Schriefers, H., & Pechmann, T. (1988). Incremental production of noun-phrases by human speakers. In M. Zock, & G. Sabah (Eds.), Advances in natural language generation (pp. 172–179). Pinter.

- Scontras, G., Degen, J., & Goodman, N. D. (2017). Subjectivity predicts adjective ordering preferences. Open Mind, 1(1), 53–66. https://doi.org/10.1162/OPMI_a_00005

- Scontras, G., Degen, J., & Goodman, N. D. (2019). On the grammatical source of adjective ordering preferences. Semantics and Pragmatics, 12(7), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.3765/sp.12.7

- Scontras, G., Kachakeche, Z., Nguyen, A., Rosales, C., Samonte, S., Shetreet, E., Shi, Y., Tourtouri, E. N., & Trainin, N. (2020). Cross-linguistic evidence for subjectivity-based adjective ordering preferences. Talk presented at the Theoretical and experimental approaches to modification conference (TExMod2020)., Tübingen, Ger.

- Scott, G. J. (2002). Stacked adjectival modification and the structure of nominal phrases. Functional structure in DP and IP: The cartography of syntactic structures, 1, 91-120.

- Shlonsky, U. (2004). The form of Semitic noun phrases. Lingua, 114(12), 1465–1526. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lingua.2003.09.019

- Sproat, R., & Shih, C. (1991). The cross-linguistic distribution of adjective ordering restrictions. In C. Georgopoulos, & R. Ishihara (Eds.), Interdisciplinary approaches to language: Essays in honor of S. Y. Kuroda (pp. 565–593). Springer.

- Stavrou, M. (1999). The position and serialization of APs in the DP. In A. Alexiadou, G. Horrocks, & M. Stavrou (Eds.), Studies in Greek syntax (pp. 201–226). Kluwer Academic Publishers.

- Svenonius, P. (2008). The position of adjectives and other phrasal modifiers in the decomposition of DP. In L. McNally, & C. Kennedy (Eds.), Adjectives and adverbs: Syntax, semantics (and discourse) (pp. 16–42). Oxford University Press.

- Trainin, N., & Shetreet, E. (2021). It’s a dotted blue big star: On adjective ordering in a post-nominal language. Language, Cognition and Neuroscience, 36(3), 320–341. https://doi.org/10.1080/23273798.2020.1839664

- Trotzke, A., & Wittenberg, E. (2019). Long-standing issues in adjective order and corpus evidence for a multifactorial approach. Linguistics, 57(2), 273–282. https://doi.org/10.1515/ling-2019-0001

- Whorf, B. L. (1945). Grammatical categories. Language, 21(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.2307/410199

- Wulff, S. (2003). A multifactorial corpus analysis of adjective order in English. International Journal of Corpus Linguistics, 8(2), 245–282. https://doi.org/10.1075/ijcl.8.2.04wul