ABSTRACT

This article focuses on three Dar es Salaam-based book clubs, all founded by women post-2016 – Taswira Book Club, Umoja Book Club and Leaders Read Book Club – and examines how they are positioned through their relationships with booksellers, digital technology and each other. Building on the work of Stephanie Bosch-Santana and drawing on original interview material, it argues for these book clubs as paravirtual networks through which vibrant reading communities are being constructed in Tanzania. Documenting the variety of ways in which digital technology supports and sustains these new literary communities, even while physical meetings continue to be important, this article is concerned with how these book clubs are able to open up new forms of social space and female-led communal participation around books. While booksellers in Tanzania are working closely with these book clubs, this study reveals a disconnect between these book clubs and Tanzania-based publishers. The conclusion proposes that new modes of literary activism can be opened up by publishers and book clubs working more closely together.

In January 2020, Book Mart — a Dar es Salaam-based online bookshop — shared their ‘9 Best Tips to Read More Books in 2020’ (Book Mart Citation2020a). These recommendations moved from where to read and how to build this into your daily routine, to what to read and how to find affordable books. Strikingly, two of the nine suggestions emphasized the benefits of communal reading with tip six suggesting ‘Read with a buddy’ and tip three recommending ‘Join a book club’ — advocating the benefits of discussing books with other people and describing this as ‘liberating’ and something that can ‘expand your mind and perspective’ (Book Mart Citation2020a). The bookshop’s blog post then continued:

When you join a book club, not only will you have fellow readers hold you accountable to read more, you will also be part of a community that makes reading books a priority. If you do not know any book clubs around you, try Leaders Read Book Club on Twitter and Leaders Read Book Club on Instagram, Dar Book Club, Taswira Book Club, Umoja Book Club, Kamureen Book Club, The Ship Book Club. These are all based in Dar es Salaam, with an option of being a virtual member if you are outside Dar es Salaam. (Book Mart Citation2020a)

This article focuses on three of these book clubs — Taswira Book Club, Umoja Book Club and Leaders Read Book Club — and explores their relationship to the book industry in Tanzania. These book clubs form particularly significant relational case studies in part because they were all founded by women, but also because of the ways they have each built and sustained growing communities of readers through a range of different approaches and emphases. Each of these book clubs aims to meet physically every month, while also having an online presence that shapes their activities and defines their relationships with readers, writers and booksellers in Tanzania and beyond. It is worth noting that our primary concern here is not with studying the kinds of discussions that take place within these reading groups — although it is notable Umoja focuses on discussing non-fiction that might broadly be categorized as ‘business motivation’ and ‘self-improvement’ books, Taswira focuses on African fiction, and Leaders Read moves across both ‘business motivation’ and ‘self-improvement’ non-fiction choices and African fiction. Instead, we are interested in thinking about how these book clubs operate structurally — their motivations, their practices for building communities of readers across physical and digital spaces, and the impact of this on models of book buying and publishing in Tanzania. In order to stage these conversations, we begin by briefly situating this study in relation to existing scholarly work on reading and reception in Africa, the book industry in Tanzania, and the possibilities opened up by digital technology for African publishers. Through this, the article is then able to explore key critical questions: How do these female-led book clubs build reading communities? How does digital technology enable this? In what ways do these book clubs forge relationships between readers and booksellers in contemporary Tanzania? Why have these book clubs built closer relationships to Tanzanian bookshops than to Tanzania’s formal and informal publishing sectors? What is the significance and value of these book clubs as spaces constructed by women within Tanzania’s male-dominated publishing industry? How do questions of gender, social class and language impact on reading, book buying and publishing in Tanzania? In what ways do these book clubs reinforce neo-liberal structures that are a legacy of colonial violence and perpetuate inequalities in the global publishing industry? In what ways — if at all — do these book clubs open up opportunities for new modes of literary activism and Africa-based publishers?

Africa-based Readers, the Tanzanian Book Industry and Digital Possibilities

As James Procter and Bethan Benwell note in their study Reading Across Worlds, the last 30 years have seen an ‘unprecedented rise of book groups’ to the extent that transnational publishing conglomerates, literary festivals and major UK and US book chains now explicitly create content and outreach targeted towards book groups as a significant audience within the global literary marketplace (Procter and Benwell Citation2005, 1, 147-8). Procter and Benwell’s own study, which examines how groups of readers in different locations — from Lagos to New Delhi to Glasgow — engage with particular postcolonial literary texts, is significant in reorienting postcolonial literary studies away from amorphous discussions of a deterritorialized reader and emphasizing the need for research which engages with specific reading acts and their ‘precise location within specific social, institutional, discursive and geographical settings’ (3). This resonates with the pioneering work of Stephanie Newell and Karin Barber which has brought into view the ways in which Africa-based reading communities have engaged with and responded to texts in resistant and creative ways, producing new reading practices and conceptions of cultural value (Newell Citation2000, Citation2002, Barber Citation2006). Similarly, focused on Tanzania specifically, the work of Uta Reuster-Jahn has been important in foregrounding the significant role that readers play in shaping the production of Swahili popular fiction through their dialogic interactions with serials published in newspapers and magazines, and more recently across digital platforms (Reuster-Jahn Citation2008, Citation2017). And yet, as Ruth Bush highlights in her recent article ‘African Readers as World Readers’ for the Edinburgh History of Reading, this work documenting ‘intellectual and creative activity taking place on the African continent’ remains disconnected from discussions of world literature and the global literary marketplace (Bush Citation2020, 304). As Bush argues, for the most part discussions of African books and readers taking place in academia, the media and between those invested in the African book industry (from governments, to NGOs and bodies such as UNESCO, to transnational and local publishers) are not informed by empirical engagement with Africa-based reading communities and practices (304-6). With this in view, our approach here very deliberately emphasises not only these Dar es Salaam-based book clubs engaging with, accessing and validating particular books and genres, but the implications of this for the book industry in Tanzania.

Abdullah Saiwaad, owner of Dar Es Salaam-based publishing house Readit Books, has highlighted the detrimental impact that fluctuating government policy has had on the publishing industry and book sector in Tanzania (Saiwaad Citation2017). The 1991 Textbook Procurement Policy opened up the involvement of privately-owned publishers in the educational book market and created a robust market for textbooks and a reliable revenue stream for publishers and booksellers. However, in 2013, government policy changed and the Tanzania Institute of Education (TIE) was designated the only producer of core textbooks, with privately-owned publishers allowed to develop just subsidiary textbooks which would then need to be evaluated and approved by TIE (Saiwaad Citation2017, Rotich, Kogos, and Geuza Citation2017). This move to a state-owned educational book market has resulted in a significant loss of income and market for commercial and independent publishing and bookselling in Tanzania.Footnote1 In response to the radically shifted contours of the publishing marketplace and a reduced capacity to finance their work, publishers have necessarily needed to think more seriously and creatively about the trade book market in Tanzania (which has traditionally been small) and about venturing into new publishing genres and formats. This article suggests that the rise of visible communities of readers through book clubs presents a significant — although not straightforward — opportunity with this in view.

The challenges faced by the Tanzanian book industry are not limited to state intervention in book production itself. Government-sanctioned NGO-involvement in educational book production has also worked against building sustainable interventions that invest in the indigenous publishing industry (Saiwaad Citation2017) while fluctuating policies on the language of instruction in schools have resulted in ‘language and literacy issues’ that ‘compound problems’ faced across trade and educational publishing caused by ‘the separate issues of poverty and a lack of purchasing power’ (Bgoya and Jay Citation2013, 28-30). In fact, the problems and trade barriers facing African publishers diagnosed from the existing literature by Emma Shercliff, very much resonate with the Tanzanian context, including:

a lack of […] distribution networks, problems of piracy and copyright theft, the price of paper and lack of its local production, a lack of professional training opportunities and limited book buying public, fuelled in part by education systems in which most schoolchildren’s experience of books is negative, […] high taxation on paper and printing facilities. (Shercliff Citation2016, 10-11)

As Nathalie Carré has argued in relation to Eric Shigongo and Global Publishers, the huge success of these popular fiction publishing initiatives indicates a ‘real market for reading’ while also revealing the importance of digital technologies ‘in capturing this’ (Carré Citation2016, 60). Similarly, Lutz Diegner’s study of the smartphone app Uwaridi, launched by a collective of leading Swahili novelists, emphasizes the significance of this innovation for strengthening the publishing industry in Tanzania — particularly if in the future the platform is able to bring together the ‘riwayapendwa’ (popular novels) it already hosts with ‘riwaya-dhati’ (‘serious novels’) (Diegner Citation2018, 43, 47).Footnote2 While Swahili popular fiction has flourished in the informal publishing sector, Swahili literary fiction has remained an area of strength for Tanzania’s formal publishing sector (Saiwaad Citation2017). Footnote3 There are certainly signs though that traditional publishers are also beginning to recognize the potential of a broader market for both Swahili fiction and digital content. For example, in 2018 leading publisher Mkuki Na Nyota republished high quality editions of the late Elvis Musiba’s spy and detective novels, which had circulated widely in pulp fiction editions from the 1970s, as part of a commitment to revive and preserve Tanzania’s literary heritage (Mkuki na Nyota Citation2018). Mkuki na Nyota’s founder Walter Bgoya has also been vocal both about the importance of Africa-based publishers producing books in African languages, and the role of digital technology in enabling this (Bgoya Citation2001, Citation2015, Bgoya and Jay Citation2013). One of the questions this article then wrestles with is the relationship between language and the book industry in Tanzania, and the implications of the decision by these three book clubs to operate and read predominantly in English.

Through this article we argue that the possibilities these female-led book clubs open up for growing markets and innovation within the book industry lie in the participatory ways that they utilize digital technology and social media. Zahrah Nesbitt-Ahmed has documented the expanding possibilities opened up by the ‘digital revolution’ for publishing ‘by Africans for Africans’, making African literature more visible and accessible, and ‘creating a reading culture that embraces a staggeringly wide variety of texts and genres for readers to choose from, such as romance, science fiction and fantasy’ (Nesbitt-Ahmed Citation2017, 378, 382, 386). Significantly, Nesbitt-Ahmed foregrounds the opportunities online platforms and mobile devices offer for building new communities of Africa-based readers — linking this to what Bibi Bakare-Yusuf has described as digital publishing’s potential to create ‘social space’ (384). In a keynote speech ‘Technology and the Future of the Book’ delivered in 2011, founder of leading Nigerian publisher Cassava Republic Press argued that in the ages of digital and social media we should think of books as ‘a site for certain form[s] of sociality and congregation’ and for ‘communal participation’ (Bakare-Yusuf Citation2011). Building on this, our study pays particular attention to the book club as a site of ‘communal participation’ and to the work of Leaders Read, Umoja and Taswira in constructing ‘social space’ through WhatsApp, Twitter and Instagram.

Mapping Dar es Salaam’s Paravirtual Book Club Network

While book clubs have been operating in schools in Tanzania to support teaching and learning for many years (Mulokozi and Mung'ong'o Citation1993), the establishment of public book clubs outside of the educational space is a new phenomenon.Footnote4 The Dar Book Club, which focuses primarily on non-fiction ‘self-improvement’ books, was founded in 2014 by Gonzaga Rugambwa and was perhaps the first Dar es Salaam-based reading group to be set up with both regular monthly meetings and a vibrant online network (Rugambwa Citation2020). Although Dar Book Club remains very active, its emphasis since 2017 has shifted towards sharing broader reading goals via a Telegram chat group and empowering members to set up their own smaller local meetings (Rugambwa Citation2020).

TaswiraFootnote5 Book Club was founded in January 2016 by a group of three women — Joan Kimirei, Asha Abdallah and Sauda Simba — with a passion for reading who wanted to create a shared forum for discussing books, and was established in partnership with Soma Book Café (Soma Book Café Citation2016a). The book club focuses on African fiction and meets every last Thursday evening of the month (apart from in December) for 2 to 3 hours (Kitunga Citation2020b). Taswira Book Club has become one of the most regular forums at Soma Book Café — a readership promotion and literary hub set up in 2008 as part of E&D Readership and Development Agency's quest ‘to mobilise public interest and agency in promoting a culture of reading beyond curriculum requirements’ (Soma Citation2018, 3). Demere Kitunga, the organisation's founder, is also the co-founder of ‘sister’ publishing house E&D Vision Publishing, and describes both literary initiatives as founded on feminist principles ‘visible in the books we produce, services we provide, and how we organize space and relationships’ (Kitunga Citation2020a). As we explore in more detail through this article, since 2017 Taswira has used WhatsApp as its principle form of communication and members use this digital space to collaboratively select the books they want to read together. Taswira’s book choices are then necessarily filtered through questions around access and availability, as Soma Book Café works to source the selected texts to sell to members through their bookshop; while there is no membership fee to join the book club, the cost of the selected books (which are usually published outside of Tanzania) can be a barrier to wider participation. Taswira’s book club choices are predominantly African fiction and non-fiction in English, although books published by Tanzanian publishers are well-represented and at least once a year the monthly selection is a book in Swahili. Membership of the book club is ‘fluid’ with the WhatsApp group made up of around fifty members, and physical meetings usually attended each month by a shifting group of around ten and up to thirty (Kitunga Citation2020b, Mwakiwone Citation2020, Sabuni Citation2020).

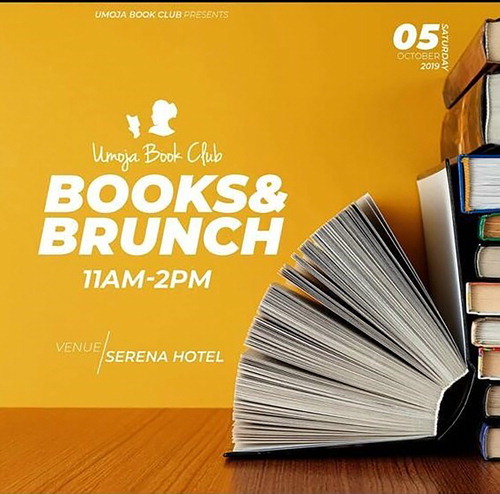

Umoja Book Club was founded in April 2018 by lawyer Dorin Rugaiganisa, and describes itself as a ‘Dar es Salaam-based women’s book club focused on connecting like-minded women and empowering a nation through reading’ (Umoja Book Club Citation2020). Talking about her motivations for setting up this group, the founder emphasized this as a multi-faceted initiative concerned with the benefits reading can bring to individuals, with fostering a ‘creative network of women’, and with building a stronger reading culture in Tanzania (Rugaiganisa Citation2019, Citation2020). The book club began as an informal group of around ten friends, and within a year had grown to a membership of over fifty like-minded professional women in their late twenties or early thirties (Rugaiganisa Citation2020). Umoja Book Club meet once a month at a high-end restaurant or hotel, with their regular Saturday lunchtime ‘Books and Brunch’ or ‘Booked for Lunch’ meetings indicative of this (see ). Members pay an annual membership subscription, and both members and non-members pay to participate in the monthly events; as Rugaiganisa commented in interview, this means members necessarily need to have four to six years of work experience in order to manage this financial commitment (Rugaiganisa Citation2020).

At the start of each year Umoja Book Club circulate a list of their monthly book selections to members, with all these titles stocked by Elite Bookstore (Rugaiganisa Citation2020). Reading choices focus on non-fiction written in English from Todd Henry’s Die Empty: Unleash Your Best Work Every Day to Dale Carnegie’s How to Win Friends and Influence People to Ritha Tarimo’s The Color of Life; through this a particular emphasis is placed on reading as enabling ‘a more purposeful life’ and initiating reflective discussion around both social and professional issues (Rugaiganisa Citation2019, Citation2020). At each event the book club host a Tanzanian professional as a guest speaker (male or female), with influential politicians and entrepreneurs including Togolani Mavura, Faraja Nyalandu and January Makamba all having attended to share their thoughts on the book under discussion that month (Rugaiganisa Citation2020). Umoja is the Swahili word for ‘unity’ and the Book Club places particular emphasis on a coming together as a network of women to support each other and create a space for self-care and professional or intellectual development outside of the constraints of family life. As this article will explore in more detail, social media (and Instagram in particular) play an important role in building this network as female-curated aspirational space that advocates for education and literacy (Rugaiganisa Citation2020).

Leaders Read Book Club was founded in September 2018 by creative entrepreneur Rehema Bashir, just a few months after she founded online bookstore Book Mart. Again the book club began as an informal group of around twenty female friends, which has now grown to a WhatsApp group of nearly two hundred members extending across gender lines and beyond Dar es Salaam to other parts of Tanzania, and to Kenya, Uganda and Malawi (Bashir Citation2020). The book club’s name ‘Leaders Read’ reflects an emphasis on reading for self-development, with the club’s registration form setting out its mission to ‘educate and encourage’ and through this enable Tanzanians to attain ‘lifelong learning, improved life chances and the ability to participate in society’ (Leaders Read Book Club Citation2020).

Again WhatsApp is used as the group’s principle form of communication and organisation. Members share their reading suggestions on WhatsApp and in 2019 out of these suggestions Bashir collated two reading lists: one of twelve non-fiction titles and one of twelve African fiction titles — all in English (Bashir Citation2020). Over the next year, fourteen of these titles became ‘group reads’ including Paul Kalanithi’s When Breath Becomes Air, Lola Shoneyin’s The Secret Lives of Baba Segi’s Wives and George Orwell’s Animal Farm. In 2020 Leaders Read decided to organize things slightly differently and formed sub-groups on WhatsApp run by volunteers. These sub-groups established their own reading lists around particular areas of interest with active sub-groups currently including business books, African literature, popular fiction and parenting books (Bashir Citation2020). Although Leaders Read brings together a larger community of readers across geography through digital technology, monthly physical meetings are hosted in Dar es Salaam and attended by a fluid group of around ten (Bashir Citation2019).

Through this article we are concerned to examine the extent to which these book clubs open up new markets for books in Tanzania, reflecting on what Murray has described as the ‘complex interrelationship of “community” and “commodity” in the contemporary book industries’ (Murray Citation2018, 77). Given this, Leaders Read offer a particularly rich case study, interacting with a number of bookshops, while making its close relationship with Book Mart consistently evident through social media. Notably, Leaders Read attract a younger demographic than Umoja or Taswira, including many recent graduates and also students. This is facilitated and encouraged by the lack of a membership fee — although the club’s registration form does explicitly ask if members are willing to contribute financially to the club’s activities and how much (alongside questions around expectations and current reading habits) (Leaders Read Book Club Citation2020). As a result of this, many book club members aren’t in a financial position to buy the books being read each month and so the group also has a culture of sharing PDF versions to enable wider access and discussion.

Stephanie Bosch-Santana has written powerfully about Malawi-based Story Club — an organisation founded by Shadreck Chikoti that hosts writing workshops and public literary events —as a literary community that is ‘facilitated by virtual networks, but is not reducible to them’ (Bosch-Santana Citation2019, 393). Building on the work of Stephanie Newell,Footnote6 Bosch-Santana conceptualizes an idea of ‘paravirtual networks’ to describe networks that are ‘mediated in significant ways but that operate “alongside and beyond” (Newell Citation2001, 350) the virtual sphere’ (Bosch-Santana Citation2019, 386). As we move into examining more closely how Leaders Read, Umoja and Taswira each use digital technology to construct ‘social space’, the idea of ‘paravirtual networks’ offers a rich frame to draw attention to these book clubs as ‘enabled by’ but ‘ultimately exceed[ing]’ virtual space (386). Through this frame we are able to draw attention to the ways in which global digital connectivity enables locally-based reading communities. For the most part, we show the digital exchanges of these Tanzanian book clubs across WhatsApp, Twitter and Instagram remaining more locally or regionally focused when compared with the international exchanges Bosch-Santana highlights Story Club being able to materialize in the Malawian literary space (395).

The book industry in Tanzania is heavily male-dominated both in terms of ownership and authorship. We are therefore also interested in bringing a gendered lens to the idea of ‘paravirtual networks’, foregrounding the significance of these book clubs as spaces established and curated by women. Notably female figures at the centre of each of these book clubs have studied outside of TanzaniaFootnote7, signalling the nuanced ways these Dar es Salaam-based book clubs are ‘entangled within wider transnational networks of production and consumption’ (Procter and Benwell Citation2005, 1). Across this article we explore how these spaces of communal participation, constructed out of a ‘gendered experience of travel’ (Spencer Citation2016), open up ‘creative forms of self-making’ through which ‘different constituencies craft gendered versions of themselves’ (Spencer, Ligaga, Musila Citation2018, 4), in turn opening up new possibilities for more equitable (publishing) futures.

Equally, we suggest that the idea of ‘paravirtual networks’ offers a useful frame to conceptualize the ways in which these reading groups access the books they read across print and digital formats. Tanzania currently has an internet penetration rate via mobile phones of around 45% (Tanzania Communications Regulatory Authority Citation2020), and Africa-based publishers have highlighted the opportunities presented by providing content to mobile devices (Bakare-Yusuf Citation2011). However, challenges of infrastructure and access remainFootnote8, and publishers and scholars have stressed that print remains a vital medium for book distribution in Africa for the foreseeable future (Bakare-Yusuf Citation2011, Zell Citation2013, Bgoya and Jay Citation2013, Wallis Citation2016). In what follows we show global digital space working to facilitate access to books for these book clubs, even as they each work to reinforce the value of Dar es Salaam-based bookshops and the medium of print.

Reading Communities and Digital Technology

While structurally these book clubs are constructed around a physical meeting in Dar es Salaam each month, digital technology enables Taswira, Umoja and Leaders Read to encourage and sustain ‘communal participation’ (Bakare-Yusuf Citation2011) in ways that are both inward-facing (for example though a shared WhatsApp group) and outward-facing (for example through Twitter, Facebook and Instagram).

Taswira Book Club

Taswira Book Club’s most significant engagement with digital technology is inward-facing, with a WhatsApp group as the ‘social space’ through which they organize activities. Across February and March 2020 for example, group discussion focused primarily on voting for the titles the book club would read across the year — with Nuruddin Farah’s Hiding in Plain Sight, Aminatta Forna’s The Memory of Love and Uwem Akpan’s Say You’re One of Them proving particularly popular choices. Soma Book Café staff play an active role in the WhatsApp group, sending regular reminders about the book choice each month and details of how to purchase this. They also use this WhatsApp group to make sure Taswira members are aware of other Soma activities, such as their regular Book Bazaar events. However, while Soma plays a significant role in sourcing book club titles and encouraging members to buy these books via WhatsApp, there is a very open acknowledgement that not all members will be able to buy the selected book each month; consequently, ahead of each meeting, members who haven’t been able to source their own copy reach out and other members lend them copies in order to ensure a wider and more inclusive discussion.

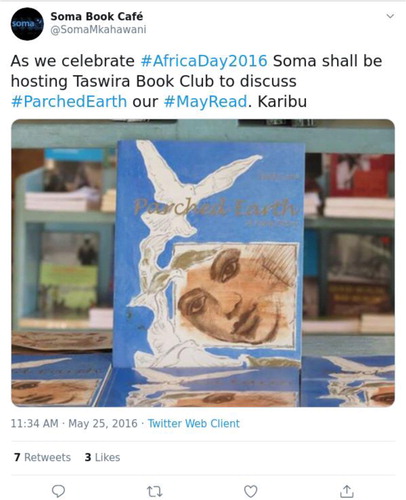

Taswira are the only one of these three book clubs without its own dedicated social media accounts; however, Soma Book Café have consistently worked to draw attention to and recruit new members for Taswira through their social media platforms. For example, on 25 May 2016 Soma Book Café posted on Twitter (see ) drawing attention to Taswira’s discussion of “MayRead” Parched Earth by Elieshi LemaFootnote9 which was taking place that evening. This had been preceded by a longer post on Facebook on 5 May, highlighting this event as ‘part of our quest to promote readership’ and the author herself ‘among the members of the club’, as well as sharing details of the cost of the book (13,000 TSH) and directions to Soma to purchase it (Soma Book Café Citation2016b).

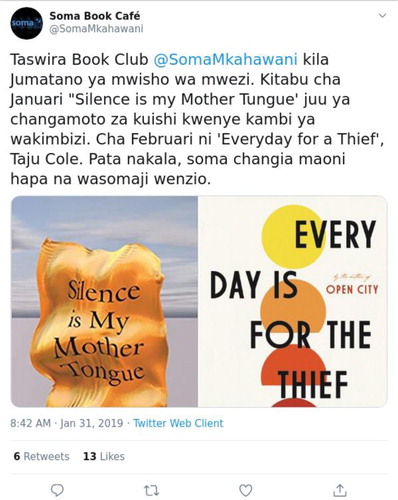

Soma Book Café currently have over 2000 followers on both Facebook and Instagram, and 6500 on Twitter.Footnote10 This is reflective of Twitter as the platform they have placed most consistent emphasis on over the life of Taswira, with Soma Book Café regularly tweeting about Taswira’s monthly meetings, stressing this as an ‘open book club’ and encouraging their followers to join these conversations. offers an apt example — a tweet in Swahili highlighting the monthly reads for January and February 2019 and encouraging followers to get a copy, read and share their views with other readers. Over the past year Soma Book Café have started placing increasing emphasis on sharing books and events on Instagram, including posting photos from Taswira’s discussions of Lubacha Deus’s If She Were Alive in February (see ) and Benjamin Mkapa’s My Life My Purpose in March 2020 — both published by Mkuki na Nyota.

While Soma Book Café has regularly posted across their social media platforms about Taswira since 2016, this hasn’t been done consistently each month and photos from their meetings are only shared perhaps two or three times a year. However, Soma Book Café are increasingly likely to post about Taswira when they are reading a book published by a Tanzanian publisher such as Mkuki Na Nyota, or sister company E&D Vision who published Lema’s Parched Earth.

Umoja Book Club

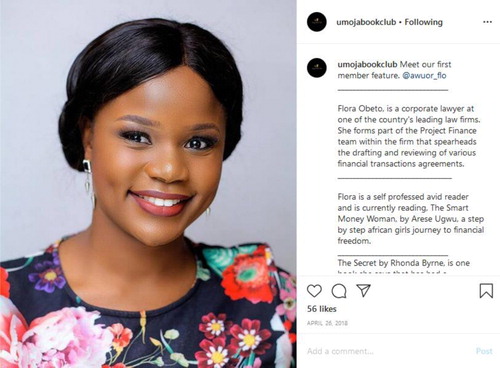

While Umoja Book Club also keeps in touch with members through WhatsApp, its most significant engagement with digital technology is very much outward-facing. Umoja have a carefully curated social media presence across Facebook, Twitter and Instagram. The book club have a smaller number of followers on Facebook (300) and Twitter (450), placing most emphasis on their larger community of over 3000 Instagram followersFootnote11. Umoja use Instagram Stories to showcase their monthly reads (with the hashtag #BOTM), their guest speakers and #UmojaDiaspora members living outside of Tanzania. They have an ongoing ‘member feature’ which has run since April 2018 (see ), sharing photos and profiles of Umoja Book Club members; profiles begins with short professional biographies before moving into sharing what they are currently reading and a book that has had an impact on their lives. While these reading recommendations often have a ‘self-development’ emphasis, through these profiles Umoja display an eclectic and wide-ranging list of reading reference points from Paul Coehlo’s The Alchemist to Ben Okri’s Mental Fight to Ben Carson’s Think Big.

Each month Umoja create a specially designed e-flyer to advertise their monthly meeting (of which is an example). After each meeting, across all three social media platforms, they post ten to fifteen photos of the book club event. These professional-quality shots range from individual and group portraits mid-discussion to staged group photos (see ). In an interview with Ritha Tarimo, Umoja member Anabahati Mlay reflected on the monthly book club meetings both in terms of their professional and personal benefits but also as ‘me-time’ and ‘fun’, providing an opportunity for members to dress up and socialize (Mlay Citation2019). For Umoja then, the polished and performative documenting of these social and stylish book events through social media very deliberately works towards creating a culture of reading as something aspirational and gendered. By making ‘strategic use of digital connections’ (Bosch-Santana Citation2019, 386), Umoja are able to ‘show the world’ (Rugaiganisa Citation2020) a group of affluent and confident Tanzanian professional women who are choosing to spend their leisure time meeting to enjoy books — through this fostering and amplifying the reach of these ‘face-to-face interactions’ (Bosch-Santana Citation2019, 386).

At the top of Umoja’s Facebook page is a statement ‘Advocating for Education and Literacy for all in Tanzania’ which stresses this as a network of like-minded women ‘who understand not only the importance of reading and extracting knowledge for self-development but [are] passionate about paying it forward and creating meaningful impact’ (Umoja Book Club Citation2019). This is reflected in their recent ‘Twende Zetu Maktaba!’Footnote12 initiative, where Umoja partnered with the National Library and sponsored membership for 100 school children. Again this work is visibly documented through their social media accounts, with short videos showing the group’s visit to the National Library in Umoja Book Club branded t-shirts, their reflections on what reading means to them and their interactions with young people. In our interview Dorin Rugaiganisa emphasized Umoja’s commitment to expanding and continuing this advocacy work through research into the barriers to children and young people reading in Tanzania and setting up new projects that respond to this (Rugaiganisa Citation2020).

Leaders Read Book Club

While sharing this commitment to expanding education and reading in Tanzania, Leaders Read’s most significant engagement with digital technology is, like Taswira’s, inward-facing. However, the multiple Leaders Read WhatsApp groups move beyond functioning as ‘social space’ surrounding the organisation of physical book club meetings, instead working as a ‘social space’ for the discussion of books on their own terms. In a reflective piece written at the end of the first year of running Leaders Read, Bashir commented that she’d managed to read a total of 20 books in 2018 with several of these ‘recommendations and challenges from my book club’ (Bashir Citation2018). Members often post quotations and share what they are reading via WhatsApp — even when this isn’t related to any collective book list. So for Leaders Read, these WhatsApp groups offer a digital space to support and motivate members to read. In addition, members regularly use the WhatsApp groups to request and share PDF copies of books.

While Leaders Read do have a presence on social media, they do not post regularly and consequently have just over 150 followers on Twitter and nearly 300 on Instagram.Footnote13 Usually meetings are not advertised on social media, although at the end of January 2019 the book club posted an e-flyer on Instagram for their February meeting to discuss George Orwell’s Animal Farm at Inspire Centre. A couple of times over the last two years Leaders Read have shared photos from their meetings via Twitter and Instagram, but again this is not something done consistently. Perhaps signalling a move to place more emphasis on building their community of readers online, in December 2019 they created a series of Instagram Stories to showcase their new sub-groups. Each sub-group had a jewel-named Instagram Story (with Emerald for African Literature and Sapphire for Business Books), and through these the book club shared links to join the relevant WhatsApp chat. It is striking though that for the most part Leaders Read’s Twitter feed is used to repost tweets from Book Mart. This will be explored further and provides a natural connection to the next section of this article which examines the variety of ways book clubs are being built in close dialogue with booksellers, including both established physical bookshops and new online bookselling platforms.

Book Club and Bookselling Exchanges

All three of these book clubs have very deliberately worked to make visible their links to booksellers and to bring booksellers into the ‘social space’ of the book club through digital technology. Rotich has argued that the success of the publishing sector largely depends on the range and variety of effective retail outlets through which books reach the readers — with booksellers acting as a vital bridge between the publisher and the reader (Rotich Citation2000). Here we draw attention to book clubs interacting with and forging relationships with booksellers in Tanzania, and consider the implications of this for the book industry more broadly.

As we’ve shown, Soma Book Café plays an integral role in the organisation of Taswira, as well as being the bookshop that sources and stocks the books that the club choose to read. Very often Soma Book Café will prompt Taswira members via WhatsApp to make their reading choices and suggest books to consider. Through this Taswira is able to benefit from Soma’s wider work as a reading agency and its relationships with literary organizations in the region. For example, early in 2020 Kitunga was travelling to Zimbabwe and suggested that Taswira consider Weaver Press’s list of African fiction and non-fiction titles for either their monthly reads or as personal purchases — which she could source while she was in the country. When Soma Book Café post on social media to draw attention to new titles in stock, they quite often use the hashtag #bookclub or highlight titles as recommended reads for book clubs — signalling that these groups of readers do constitute a recognized and valued market for booksellers in Dar es Salaam. However, as Programme Assistant Invioleta Mwakiwone explained in interview, Taswira itself constitutes a relatively small, although reliable, market for Soma Book Café: only four members consistently buy the monthly read and usually a maximum of seven (Mwakiwone Citation2020). To some extent this acts as a vicious circle for the book club: Soma Book Café can only ever stock a few copies of each monthly book to avoid being left with unsold copies; acquiring only a few copies often means a lower discount from distributors or publishers and higher prices for customers; the high prices continue to reinforce fewer members being able to afford to buy the books. So, for example, the Weaver Press books Kitunga brought back from Zimbabwe such as Chris Mlalazi’s Running with Mother and Valerie Tagwira’s The Uncertainty of Hope were priced at 37,000 TSH (over 15 USD).

However, the relationship between Taswira and Soma Book Café extends beyond functional questions of book buying and hosting monthly meetings. Soma Book Café are invested in building Taswira as a community of readers, with Kitunga talking in interview about the importance to this wider mission of working to ‘reduce the gap between print and audio or digital books’ and encouraging members to access books in whatever format they prefer. Similarly, Taswira members are invested in supporting the work of Soma Book Café, with members’ book-buying habits motivated by a sense of responsibility to their reciprocal relationship: as Jasper SabuniFootnote14, a longstanding member, commented in interview:

We buy books from Soma because we feel responsible to maintain the club as its potential customers who make the bookshop run smoothly. If we do not buy and the bookshop fails to run, we shall also be unable to meet. So, we are a family (Sabuni Citation2020).

Umoja have chosen to partner with Elite Bookstore — a relatively newly-established chain of bookstores in Tanzania with a strong network of partner bookshops across East Africa. Elite focus on the educational market and are a sister company to publisher APE Network, as well as stocking a good range of popular fiction and business motivation titles. As co-owner Hermes Salla reflected in interview, while Elite has no formal organisational links with Umoja, they have established a mutually-supportive partnership based on a shared commitment to both reading culture and Tanzania-based entrepreneurship (Salla Citation2020). Elite not only makes sure the bookstore stocks the titles Umoja are reading, they also actively work to suggest titles Umoja might be interested in selecting as their ‘Book of the Month’ (Salla Citation2020). Through this relationship, one of Elite’s senior staff has now become an Umoja Book Club member — strengthening links still further (Salla Citation2020). Umoja members receive a 10% discount on any purchases they make at Elite and promote this through their social media platforms (see ). The discount then works as both a way of bringing members to the bookstore as well as raising Elite’s visibility.

However, as Salla explained, there are risks to the bookstore associated with this partnership; on several occasions Elite has ordered books on the basis of members’ requests and then not all copies have been purchased — leaving the bookstore with unsold stock (Salla Citation2020). Very often members choose to read PDF copies for free rather than purchase their own print editions, with perhaps only 30 or 40% investing in physical copies (Bgoya Citation2020, Salla Citation2020). However, like Kitunga, Salla was keen to emphasize that Elite’s relationship with Umoja extends beyond seeing this book club solely in terms of potential book sales, instead wanting to support and be part of this initiative that is working to make books and reading more visible and valued in the city (Salla Citation2020).

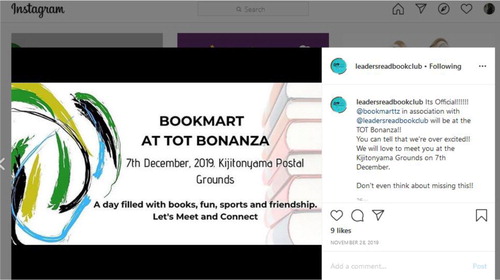

As we have highlighted, Leaders Read’s close relationship with Book Mart — as two literary initiatives started by Bashir — is made highly visible through social media. Bashir started online bookstore Book Mart as a ‘platform to access affordable books in the shortest time possible’ (Bashir Citation2019). Book Mart doesn’t have its own website but instead draws attention to its stock through Twitter and Instagram then takes orders through WhatsApp from which books are delivered direct to customers. Consequently, Book Mart is very active on social media with nearly 3000 Twitter followers and 5500 Instagram followers.Footnote15 Book Mart also actively works to build a reading community through Leaders Read, with one of their Instagram Stories (see ) encouraging people to join this space ‘where we inspire each other to read’ and highlighting that members receive a 5% discount at Book Mart. Similarly, Leaders Read often have a public presence at Book Mart events, for example a shared stand at the Tanzanians on Twitter (ToT) Bonanza (see ).

Bashir is very clear that while there are productive links between the two, Leaders Read members are not obligated to engage with Book Mart in any way, commenting:

I am a member of the club and a bookseller as well, however, these two operate independently. The club is user generated so the decision on what to read and where to get the books is based on the readers. I do not condition what they read or stop them from sharing PDFs of the same books I am selling. (Bashir Citation2020)

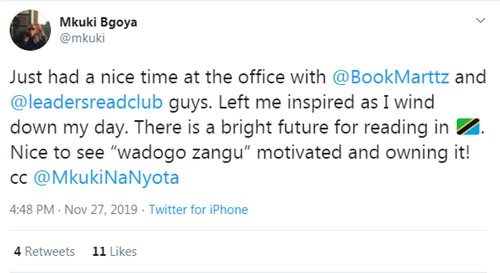

It is striking that even with a culture of sharing free PDFs of books through the WhatsApp group, Leaders Read are a community of book-buyers and actively invested in building relationships not just with Book Mart but also with other bookshops in Dar es Salaam. On 9 January 2019 on Instagram, Leaders Read announced their commitment to ‘reading books by African writers, set in Africa’ across the year and that they had partnered with Soma Book Café to source their booklist. On 27 November 2019 Mkuki Bgoya, co-director of TPH Bookshop, one of the oldest bookshops in Tanzania and sister company to Mkuki na Nyota, tweeted about a recent meeting with Book Mart and Leaders Read (see ) that left him inspired about the younger generation’s commitment to building a reading culture in Tanzania.

So, in different ways, all three book clubs actively work to build relationships with booksellers and through digital exchanges, make visible and draw readers into Dar es Salaam-based bookshops. There is a clear sense that these are relationships that are mutually valued, and move beyond the transactional. Booksellers are conscious that members will often need to source books as cheaply as possible or even for free, and that ultimately offering multiple ways to access books works to build communities of readers. While TPH Bookshop don’t have formal links with any particular book club, in interview Bgoya talked about the positive impact these groups have had in terms of bringing new customers into bookstores (Bgoya Citation2020). More than this though, he highlighted the value of book clubs and booksellers sharing books and information across digital and virtual spaces; for bookshops and publishers the presence of these book clubs on social media provides valuable insights into what books are being read and how they are being accessed within Tanzania (Bgoya Citation2020). The final section of this article now moves to consider the relationship between these book clubs and Tanzania-based publishers.

Linking Publishing and Reading Communities

While there are strong links and often shared ownership between booksellers and publishers in Tanzania, and book clubs have invested in connecting with booksellers in a variety of creative ways, much less evident are connections between book clubs and publishers. Carré has written powerfully about the ‘ongoing legacies of former colonial monopolies’ as continuing to work against Africa-based publishers (Carré Citation2016, 56). Local publishers operate in direct competition with ‘larger and better resourced Northern publishers’ who have the capacity to make their books more visible through global digital exchanges while simultaneously making them available at lower prices within Tanzania (Carré Citation2016, 57). These dynamics have direct repercussions on the book choices of these three book clubs, where we see the books that are most accessible to and valued by readers not being those produced by Tanzanian publishers. The business motivation and self-improvement titles that Umoja and Leaders Read focus on are published exclusively by ‘Northern publishers’; within this, it is striking that the 2019 monthly choices for both these book clubs included a proportionally high number of books authored by white menFootnote16, with indicative titles including Daniel Akst’s We Have Met the Enemy: Self Control in an Age of Excess, James Clear’s Atomic Habits: Tiny Changes, Remarkable Results and Simon Sinek’s Leaders Eat Last: Why Some Teams Pull Together and Others Don’t.

Significant here is the decision of each of these book clubs to read books predominantly or exclusively in English. When founders and members were asked about the reasons for this, a variety of interconnected issues emerged. When selecting new African fiction titles to read, Taswira focus on recent critically acclaimed or prize-winning books (Kitunga Citation2020b). Kitunga commented that in comparison to English there are an inadequate number of well-written, well-produced and critically acclaimed new works of fiction being produced in Swahili (Kitunga Citation2020b). Taswira also have a small number of non-Tanzanian expatriate members who regularly attend meetings and there was also a sense that keeping a focus on literary books in English works to retain this audience (Sabuni Citation2020). Yet it is also clear that the reading communities these book clubs convene are productively extended by members being able to access PDF copies for free. Copies of books published by Northern publishers in English are fairly easily accessible through pirated PDFs or low-cost ebook editions (Bgoya Citation2020, Sabuni Citation2020, Salla Citation2020). This is not the case with books in Swahili which are usually only available in higher priced print editions and where members are more conscious of the implications of copyright infringement (Sabuni Citation2020). The book buying patterns of these book clubs highlights the importance of investment in publishing in African languages for building a self-sufficient and independent publishing industry in Tanzania (Carré Citation2016, 57, Bgoya and Jay Citation2013, 31) — while raising questions around to what extent it might be possible to harness these reading communities to work towards this.

There are certainly ways in which, through their choice of books, we might position these book clubs as working to reinforce neo-liberal structures that are a legacy of colonial violence and perpetuating inequalities in the global publishing industry. As publisher Walter Bgoya has argued:

English is the language of this globalisation and English serves fundamentally the interests of those for whom it is both an export commodity and a language of conquest and domination. (Bgoya Citation2001, 286)

And yet, Simone Murray’s nuanced modelling of the ‘various gradations and interpenetrations of notions of “community” and “commodity”’ within the book industry can be useful here in allowing for the blurred boundaries of book communities and markets (Murray Citation2018, 77). Murray highlights any clear distinction between commercial imperatives and community-building as reductive, and at risk of losing sight of the ‘social bonds, emotional reciprocity, the possibility of human altruism’ constructed by communities of readers (Murray Citation2018, 62). So while we might locate these book clubs through their book buying practices as embedded within the value structures of global capitalism, their approach to accessing and sharing books, as we have shown, is permeated by strong social bonds and ideas of reciprocity. The reciprocal commitment of these book clubs and their partner bookshops to communal ownership, and working together to make books more visible and valued in Tanzania, might be equally be located in relation to the value structures of Ujamaa — the communitarian form of African socialism on which independent Tanzania was founded. Equally, while we might locate the choice of these book clubs to read predominantly in English in relation to legacies of British colonialism, we simultaneously need to keep in sight intersections with contemporary manifestations of social class and lifestyle; so, the decision to read books in English also locates these book clubs as engaged in a project of elite Afropolitan self-making, concerned with an African aesthetics of ‘mobility’ and ‘being in the world’ (Mbembe, Citation2020). Resonating with Bush’s conceptualization of Africa-based ‘world readers’, we want to suggest that these book clubs both speak to the historical impact of ‘literacy’ and ‘development’ discourse on the continent while also ‘recuperating’ reading and ‘disentangling’ this from ‘any reductive, instrumental application’ (Bush Citation2020, 304-6). It is with these layered dynamics in view that we argue that these book clubs open up new creative possibilities for Tanzania-based publishers to build sustainable trade book markets and reduce reliance on educational markets. Benwell and Procter’s study of reading groups emphasizes that while there is ‘no simple correlation between place and interpretation’ that ‘location continues to matter’ (50). As a female-curated Dar es Salaam-based participatory spaces, how might the dynamics of these book clubs model the future for more equitable modes of social change and publishing in East Africa?

Umoja are very conscious that as young African women, they are ‘not the target audience’ for their book club choices. It is as a result of this that for each monthly meeting such care is put in to invite the right African guest speaker who can respond to and emplace (Bosch-Santana Citation2018) the book under discussion (Rugaiganisa Citation2020). In conversation with Ritha Tarimo, members reflected that while the book club has often gravitated towards more accessible and visible books produced in the global North, Tanzanian or African books can speak more directly to their own experiences (Mlay Citation2019, Ngowi Citation2019, Rugaiganisa Citation2019). Vivian Ngowi, in particular, makes a passionate case for the need for Umoja to challenge itself and commit to spending more time researching African books — in order to work against the unequal systems that make these texts less immediately accessible (Ngowi Citation2019). A June 2020 Instagram post advertising the first ‘Umoja Book Club Giveaway’ of Mehreen Mushtak’s Spectrum of Happiness, as part of a commitment to celebrate ‘young and vibrant Tanzanian authors’, suggests the book club is beginning to move in this direction (see ). Spectrum of Happiness is a motivational book, supporting readers on their journey to finding happiness, self-published by Mushtak via Amazon Kindle Direct Publishing. While ‘business motivation’ and ‘self-development’ are not genres the Tanzanian publishing industry has invested in significantly to date, our research suggests that this is as an area of publishing that could be expanded and find a receptive market.

In his assessment of Tanzania’s book industry, Saiwaad argues that publishers ‘need to develop better working relations with other actors in the book chain’ (Saiwaad Citation2017). While his concern here is with the need for publishers to have richer dialogue with authors and booksellers, here we argue for what publishers could gain from a closer engagement with communities of readers. We are of course conscious that even though these book clubs convene audiences across different demographics, collectively this still constitutes only a relatively small audience of elite and/or university-educated book buyers. However, we want to suggest that the ways in which these book clubs are accessing and engaging with books remains something that publishers can learn from. As Bwesigye bwa Mwesigire vitally highlights in his keynote ‘What is Literary Activism?’ (published as part of this Special Issue), ‘it would be a big error to conceptualize our work as attempts to build our own versions of the Western Publishing Industrial Complex’ and there is a need for Africa-based literary producers to improvise and conceptualize different imaginative environments for African literary production. Given this, we are interested in the connections that can be built between research documenting African readers engaged in processes that recraft reading and writing practices (building on the work of Stephanie Newell, Karin Barber and Uta Reuster-Jahn), and the work of Africa-based publishers. Here we draw attention to the variety of creative ways that book club members are reading and interacting with books through digital platforms. With print production and import costs often prohibitive for small print runs,Footnote17 perhaps then there is a particular opportunity for publishers to embrace digital publishing and produce low-cost eBook editions of Swahili fiction and Tanzanian-authored self-improvement books? In addition, with 126 documented languages spoken across Tanzania (Languages of Tanzania Project Citation2009), digital innovations of this kind might also in turn open up possibilities for publishing beyond English and Kiswahili, with particular opportunities for investment in widely spoken languages like Sukuma and Nyakyusa and an emphasis on linguistic diversity as generative of literary and publishing cultures in Tanzania. With this in view, we advocate for more infrastructural investment in digital publishing in Tanzania, as well as research that supports the development of new publishing models and practices, in order to ensure this work can be done in ways that protect copyright and work against piracy.

On 26 September 2019, sharing one of the videos coming out of their Twende Zetu Maktaba project, Umoja posted on Instagram:

The only goal of an education is to become well-read. Educate yourself so that you can challenge preconceived notions. One of the best ways to do that is to read the most you can and be sincerely interested.

Perhaps most significantly, we want to suggest that the feminist and activist agenda of these book clubs is defined through the ways in which they instantiate the potential for books to become sites of ‘social space’ and ‘communal participation’ — resonating with the possibilities that Bakare-Yusuf identifies for digital publishing in Africa (Bakare-Yusuf Citation2011). The ‘Western Publishing Industrial Complex’ can be characterised through models of expansion and competition that set institutions, individuals and locations against each other. In contrast, these book clubs work collaboratively and generatively not only with bookshops but also with each other in ways that resonate not only with the idea of Ujamaa but also with the approach of pan-African literary networks of publishers including Kwani Trust, Chimurenga and Cassava Republic Press or the dynamics of the AMLA Network (even as these organizations necessarily remain embedded within their own intersectional structures of power). An example of this is the Valentine’s Book Bash held at Dar es Salaam’s Inspire Café on 22 February 2019. Here book lovers were invited to come together to swap books, eat and drink, play games, and even dress up as their favourite book character (Valentine Book Bash Citation2019). The event actively promoted that ‘6 Book Clubs in Dar will be present at the event in case you want to register for membership’ and the event’s registration form specifically asked ‘Which Book Club are you in?’ giving the options of Taswira, Umoja and Leaders Read alongside The Ship, Kamureen and Dar Book Club (Valentine Book Bash Citation2019). Similarly, at the end of her interview with Ritha Tarimo, Dorin Rugaiganisa encourages the audience not only to join Umoja but to set up their own book clubs (Rugaiganisa Citation2019). These book clubs have a consciousness of being greater than the sum of their parts and see themselves as part of a shared and generative book club movement located in Tanzania. This generative approach is again in evidence through Soma Book Café, Umoja and Leaders Read (in dialogue with Book Mart) all using digital technology in creative ways to build communal participation in books. Alongside an emphasis on reading as a tool for self-development and a sense of social purpose behind building a reading culture, this ‘social space’ can be characterised as foregrounding books as a source of pleasure, entertainment, social change and social connection. Book clubs become aspirational spaces in which the value of book-buying and the printed book is continually reinforced through strong relationships with booksellers and bookshops. Digital technology is concurrently used to enable these book clubs to work as inclusive spaces that lend and swap physical books, and circulate digital editions for free. Publishers in Tanzania could benefit from learning from and connecting to the ways in which this female-curated paravirtual network of book clubs has built a language, and forms of sociality and congregation, around books — located across digital and physical spaces.

Conclusion

This article argues for book clubs as paravirtual networks through which vibrant reading communities are being built in Tanzania and considers how these reading communities interact with digital technology, book buying and publishing. In this, our research builds on and extends Bosch-Santana’s conception of Africa-based literary initiatives functioning as paravirtual networks: showing the multiple ways in which digital technology enables these reading communities to come together and facilitates access to books, while also drawing attention to these book groups as gendered and not only placing strong emphasis on physically meeting but also on accessing print books. These book clubs to different degrees all use WhatsApp to communicate with each other about their reading plans and motivate each other to read, but also have a visible presence through Twitter, Facebook and Instagram which they use to advertise and performatively document physical meetings. We have highlighted how each book club has explicitly worked to build connections with Dar es Salaam-based booksellers. However, by comparison we note there is a disconnect between the way these book clubs operate and the Tanzanian publishing industry — with monthly reads most often being sourced from non-fiction and fiction titles in English published in the global North (or in the case of Taswira within the region). We acknowledge that there are fewer financial risks to booksellers sourcing and stocking books for book clubs, than to publishers considering producing new titles with this market of general readers in mind. While these book clubs represent communities of readers who will always continue to look outside of Tanzania for some of their reading, we argue that there are opportunities for Tanzania-based book clubs and publishers to build closer relationships. Our conversations show these book clubs as invested in the book industry in Tanzania and keen to place more emphasis on reading Tanzanian-authored books in both Swahili and English if more high quality fiction and non-fiction titles were available — particularly in the genres of ‘self-development’ and ‘business motivation’ (Bashir Citation2020, Kitunga Citation2020b, Ngowi Citation2019, Rugaiganisa Citation2019). While the active book buyers within these reading communities might still represent only a small and elite audience, we suggest that Tanzania-based publishers can learn from what and how they are reading. Perhaps most significantly these book clubs show new forms of female-curated social space and communal participation opening up around books in ways that place value on reading as a tool for self-development, as entertainment, and as a mode of social change. It would be exciting to see the generative and collaborative approach of these book clubs, which significantly increases the visibility and agency of women in the book industry in Tanzania, sparking new more equitable and sustainable publishing models and audiences.

Notes

1 Saiwaad notes that the number of bookshops in Tanzania rose between 1990 and 2004 from around 50 to 350, with this number now having contracted again to closer to 50.

2 Uwaridi works on a model of allowing readers access to short (c. 15 page) extracts of each book for free, which they can continue to read by paying to download or buying from the collective’s physical bookshop (Diegner Citation2018, 37-8).

3 As Doseline Kiguru has highlighted, new literary prizes (in particular the Mabati-Cornell Prize and the Tuzo ya Fasihi ya Ubunifu Award) have been significant in supporting publishing in Swahili over the last decade (Kiguru Citation2019).

4 In particular, while there are many book clubs operating and reading in Swahili in Tanzania, these tend to be linked to educational spaces and operate more locally and informally than the book clubs examined here.

5 The name ‘Taswira’ is a Swahili word which means image. The Club uses this name to symbolise the vision of having a network of readers.

6 In ‘“Paracolonial” Networks: Some Speculations on Local Readerships in Colonial West Africa’, Newell coins the term ‘paracolonial’ to describe the cultural flows visible in the interactions of literary and social clubs in West Africa in the 1920s and 30s that occur ‘alongside and beyond’ British presence in the region (350).

7 Demere Kitunga studied her Masters in Publishing at University of Stirling; Dorin Rugaiganisa studied her Masters in Law at Boston University; Rehema Bashir studied her Bachelor of Education at University of Malawi.

8 Tanzania is currently ranked 77 out of 79 countries in Huawei’s Global Connectivity Index: https://www.huawei.com/minisite/gci/en/country-profile-tz.html

9 Notably Elieshi Lema is the co-owner and Director of E&D Vision Publishing with Demere Kitunga.

10 Accessed 30 March 2021.

11 Accessed 30 March 2021.

12 Let’s Go to the Library

13 Accessed 30 March 2021.

14 Jasper Sabuni was working for Soma Book Café when Taswira Book Club was founded and supported the club’s development.

15 Accessed 30 March 2021.

16 Seven out of eleven of Umoja’s Citation2019 book choices were authored by white men, and five of twelve of Leaders Read’s 2019 non-fiction book choices.

17 Responding to this in 2014 Mkuki na Nyota invested in the Expresso Book Machine to be able to print titles on demand in-house but this has brought its own challenges (Bgoya Citation2015).

18 Work-in-progress research by Diegner shows only 6% of 82 literary novels published between 2000 and 2010 were by women.

Bibliography

- Bakare-Yusuf, Bibi. 2011. “Technology and the Future of the Book.” Information for Change, Lagos, 11 May. Keynote Speech: Technology and the Future of the Book - Welcome to Foresight For Development.

- Barber, Karin, edited by 2006. Africa’s Hidden Histories: Everyday Literacy and Making the Self. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press.

- Bashir, Rehema. 2018. “My love for reading is taking me places I have never been and introducing me to people I never imagined to meet.” Linked In, 31 December. https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/my-love-reading-taking-me-places-i-have-never-been-people-bashir?articleId=6485390578614837248#comments-6485390578614837248&trk=public_profile_article_view.

- Bashir, Rehema. 2019. Personal Interview. Ed. Zamda Geuza. Dar Es Salaam.

- Bashir, Rehema. 2020. Personal Interview. Ed. Zamda Geuza. Dar es Salaam.

- Bgoya, Mkuki. 2020. Personal Interview by Zamda Geuza. Dar es Salaam.

- Bgoya, Walter. 2001. “The Effect of Globalisation in Africa and the Choice of Language in Publishing.” International Review of Education 47 (3/4): 283–292. doi:10.1023/A:1017949726591.

- Bgoya, Walter. 2015. Growing the Knowledge Economy through Research, Writing, Publishing And Reading. Harare: Zimbabwe International Book Fair.

- Bgoya, Walter, and Mary Jay. 2013. “Publishing in Africa from Independence to the Present Day.” Research in African Literatures 44 (2): 17–34. doi:10.2979/reseafrilite.44.2.17.

- Book Mart. 2019. “Book Mart’s Top 30 Books of 2019.” Medium, 27 December. https://bookmart.medium.com/book-marts-top-30-books-of-2019-ad8f52173964

- Book Mart. 2020a. “9 Best Tips to read more books in 2020.” Medium, 20 January. https://medium.com/@BookMart/9-best-tips-to-read-more-books-in-2020-adfec9914b31.

- Book Mart. 2020b. “Book Mart’s Top 30 Books of 2020.” Medium, 23 December. https://bookmart.medium.com/book-marts-top-30-books-of-2020-e4281c8616bf

- Bosch-Santana, Stephanie. 2018. “From Nation to Network: Blog and Facebook Fiction from Southern Africa.” Research in African Literatures 49 (1): 187–208. doi:10.2979/reseafrilite.49.1.11.

- Bosch-Santana, Stephanie. 2019. “The Story Club: African literary networks offline.” In Routledge Handbook of African Literature, edited by Moradewun Adejunmobi and Carli Coetzee, chapter 26. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Bush, Ruth. 2020. “African Readers as World Readers: UNESCO, Worldreader©, and the Perception of Reading.” In The Edinburgh History of Reading: Subversive Readers, edited by Jonathan Rose, 289–312. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

- Callaci, Emily. 2017. Street Archives and City Life: Popular Intellectuals in Postcolonial Tanzania. Durham: Duke University Press. doi:10.1215/9780822372325.

- Carré, Nathalie. 2016. “From Local to Global: New Paths for Publishing in Africa.” Wasafari 31 (4): 56–62. doi:10.1080/02690055.2016.1216668.

- Diegner, Lutz. 2018. “Good-Bye, Book—Welcome, App? Some Observations on the Current Dynamics of Publishing Swahili Novels.” Africa Today 64 (4): 30–49. doi:10.2979/africatoday.64.4.03.

- Kiguru, Doseline. 2019. “Language and Prizes: Exploring Literary and Cultural Boundaries.” In Routledge Handbook of African Literature, edited by Moradewun Adejunmobi and Carli Coetzee, 399–412. Abingdon: Routledge. doi:10.4324/9781315229546-27.

- Kitunga, Demere. 2020a. “Individual African Feminists.” accessed 5 June. http://www.africanfeministforum.com/demere-kitunga/.

- Kitunga, Demere. 2020b. Personal Interview. Ed. Zamda Geuza. Dar es Salaam.

- Kitunga, Demere, and Marjorie Mbilinyi. 2009. “Rooting Transformative Feminist Struggles in Tanzania at Grassroots.” Review of African Political Economy 36 (121): 433–41. doi:10.1080/03056240903211158.

- Languages of Tanzania Project (Chuo Kikuu cha Dar es Salaam). 2009. An Atlas and Statistical Information of the Langauges of Tanzania. Dar es Salaam: Chuo KIkuu cha Dar es Salaam.

- Leaders Read Book Club. 2020. “Registration Form.” accessed 10 June. https://docs.google.com/forms/d/e/1FAIpQLSdU2wGo6bFpk9pVarE71N_XdkeNURzSDx99KiPDJv0l1cQ3zw/viewform.

- Mbembe, Achille. 2020. “Afropolitanism.” trans. Laurent Chauvet. Nka: Journal of Contemporary African Art (46): 56–61. doi:10.1215/10757163-8308174.

- Mkuki na Nyota. 2018. “Willy Gamba Reloaded!”, accessed 5 June. http://www.mkukinanyota.com/event/musiba_launch_2017/.

- Mlay, Anabahati. 2019. “Let’s Talk Reading.” In Let’s Talk, edited by Ritha Tarimo. You Tube.

- Mulokozi, M. M., and C. G. Mung’ong’o. 1993. Fasihi, Uandishi na Uchapishaji: Makala ya Semina ya Umoja wa Waandishi wa Vitabu Tanzania. Dar es Salaam: UWAVITA/DUP.

- Murray, Simone. 2018. The Digital Literary Sphere: Reading, Writing, and Selling Books in the Internet Era. Baltimore: John Hopkins Press.

- Mwakiwone, Invioleta. 2020. Personal Interview by Zamda Geuza.

- Nesbitt-Ahmed, Zahrah. 2017. “Reclaiming African literature in the digital age: An exploration of online literary platforms.” Critical African Studies 9 (3): 377–390. doi:10.1080/21681392.2017.1371618.

- Newell, Stephanie. 2000. Ghanaian Popular Fiction: ‘Thrilling Discoveries in Conjugal Life’ & Other Tales. Athens, OH: Ohio University Press.

- Newell, Stephanie. 2001. ““Paracolonial” Networks: Some Speculations on Local Readerships in Colonial West Africa.” Interventions 3 (3): 336–354. doi:10.1080/713769068.

- Newell, Stephanie. 2002. Literary Culture in Colonial Ghana: ‘How to Play the Game of Life. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

- Ngowi, Vivian. 2019. “Let’s Talk Books.” In Let’s Talk, edited by Ritha Tarimo. You Tube.

- Procter, James, and Bethan Benwell. 2005. Reading Across Worlds: Transnational Book Groups and the Reception of Difference. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Reuster-Jahn, Uta. 2008. “Newspaper serials in Tanzania: The Case of Eric James Shigongo (With an Interview).” Swahili Forum 15: 25–50.

- Reuster-Jahn, Uta. 2017. “The growing use of the internet for the publication of Swahili fiction in Tanzania.” In Littératures en langues africaines. Production et diffusion, edited by Ursula Baumgardt, 269–282. Paris: Karthala.

- Rotich, Daniel. 2000. “Publishing and distribution of educational books in Kenya: a study of market liberalisation and book consumption.” PhD dissertation, Moi University, Kenya.

- Rotich, Daniel, Emily Kogos, and Zamda Geuza. 2017. “An Investigation of Textbook Vetting and Evaluation Process in Tanzania.” Publishing Research Quarterly 34 (1): 96–109. doi:10.1007/s12109-017-9559-7.

- Rugaiganisa, Dorin. 2019. “Let’s Talk Reading.” In Let’s Talk, edited by Ritha Tarimo. You Tube.

- Rugaiganisa, Dorin. 2020. Personal Interview by Zamda Geuza. Dar es Salaam.

- Rugambwa, Gonzaga. 2020. Personal Interview by Zamda Geuza. Dar Es Salaam.

- Sabuni, Jasper. 2020. Personal Interview by Zamda Geuza. Dar es Salaam.

- Saiwaad, Abdullah. 2017. “ Interventions in Book Provision: Suffocating Education and the Local Book Industry the Case of Tanzania.” 4th Ibby Africa Regional Conference, Hotel Africana, Kampala., 22-24 August 2017

- Salla, Hermes. 2020. Personal Interview. Ed. Zamda Geuza. Dar es Salaam.

- Shercliff, Emma. 2016. “African publishing in the twenty-first century.” Wasafari 31 (4): 10–12. doi:10.1080/02690055.2016.1216270.

- Soma. 2018. “Organisational Profile.” Dar es Salaam.

- Soma Book Café. 2016a. “Klabu ya Usomaji Vitabu ya “Taswira” Yazidi kupaa.” 12 July. https://www.somabookcafe.com/klabu-ya-usomaji-vitabu-ya-taswira-yazidi-kupaa/.

- Soma Book Café. 2016b. “#MAYREAD.” Facebook, 6 May. https://www.facebook.com/SomaCommunity/posts/mayreadin-our-quest-to-promote-readership-and-in-partnership-with-taswira-book-c/1039879429411966/.

- Spencer, Lynda Gichanda. 2016. “‘Abagyenda bareeba. Those who Travel, See’: Home, Migration and the Maternal Bond in Doreen Baingana’s Tropical Fish.” African Studies 75 (2): 189–201. doi:10.1080/00020184.2016.1182319.

- Spencer, Lynda Gichanda, Dina Ligaga, and Grace A. Musila. 2018. “Gender and Popular Imaginaries in Africa.” Agenda (Durban, South Africa) 32 (3): 3–9. doi:10.1080/10130950.2018.1526467.

- Tanzania Communications Regulatory Authority. 2020. “Quarterly Communications Statistics (January to March 2020).” Dar es Salaam: Tanzania Communications Regulatory Authority.

- Umoja Book Club. 2019. “Advocating for Education and Literacy for all in Tanzania.” Facebook, 24 June. https://www.facebook.com/umojabooklcub/.

- Umoja Book Club. 2020. accessed 5 June. https://twitter.com/Umojabookclub.

- “Valentine Book Bash.” 2019. accessed 5 June. https://docs.google.com/forms/d/e/1FAIpQLSf2FURnmS6krFae2Pl77wju01OnYZ0mWFhdaIRsT5LEm6f93Q/viewform

- Wallis, Kate. 2016. “How Books Matter: Kwani Trust, Farafina, Cassava Republic Press and the Medium of Print” Wasafari (Special Issue: Under Pressure: Print Activism in the 21st Century). doi:10.1080/02690055.2016.1220698.

- Zell, Hans M. 2013. “Print vs Electronic, and the ‘Digital Revolution’ in Africa.” African Book Publishing Record 39 (1): 1–19. doi:10.1515/abpr-2013-0001.