Abstract

In the absence of good data on the costs and comparative benefits from investing in health emergency and disaster risk management (EDRM), governments have been reluctant to invest adequately in systems to reduce the risks and consequences of emergencies and disasters. Yet they spend heavily on their response. We describe a set of key functional areas for investment and action in health EDRM, and calculate the costs needed to establish and operate basic health EDRM services in low- and middle-income countries, focusing on management of epidemics and disasters from natural hazards.

We find that health EDRM costs are affordable for most governments. They range from an additional 4.33 USD capital and 4.16 USD annual recurrent costs per capita in low-income countries to 1.35 USD capital to 1.41 USD recurrent costs in upper middle-income countries. These costs pale in comparison to the costs of not acting—the direct and indirect costs of epidemics and other emergencies from natural hazards are more than 20-fold higher.

We also examine options for the institutional arrangements needed to design and implement health EDRM. We discuss the need for creating adaptive institutions, strengthening capacities of countries, communities and health systems for managing risks of emergencies, using “all-of-society” and “all-of-state institutions” approaches, and applying lessons about rules and regulations, behavioral norms, and organizational structures to better implement health EDRM. The economic and social value, and the feasibility of institutional options for implementing health EDRM systems should compel governments to invest in these common goods for health that strengthen national health security.

Introduction

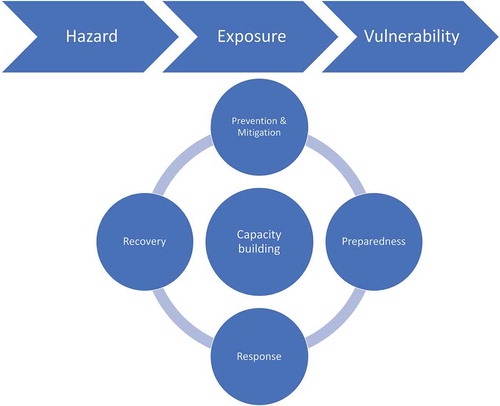

The enormous costs of emergencies and disasters, including epidemics, are in the headlines every day. Each year these devastating events affect millions of people through illness, injury, and death or by loss of home and livelihood. The challenges of emergencies and disasters are expanding for several reasons. The number of hazardous events occurring is increasing because of the changing environment and human activity, resulting in outbreaks of emerging infectious diseases and extreme weather events at different scales. People’s exposure to disasters is rising as settlements and human enterprise put more people in harm’s way. Human vulnerability, including poverty, health, and nutritional status, remain problematic, while inadequate levels of capacity in areas like prevention and preparedness to anticipate and respond to such events further threaten people’s health and wellbeing. These factors combine to create disasters and emergencies that stress communities and social institutions and undermine human economic growth, development, and security.

Governments with limited budgetary resources often fail to fund measures to proactively reduce the risks of disaster. Yet they spend large sums responding to emergencies, particularly high-impact disasters. Governments and citizens absorb huge human and economic costs, whether from epidemics like the West African Ebola outbreak of 2014–2016 or from the cluster of storms that hit the Gulf of Mexico during a few deadly weeks in 2017 (Harvey, Irma, and Maria). As shown in , since 2000, about 200 million people per year are affected by major disasters associated with natural hazards; the direct costs have risen to about $170 billion per year since 2010. From 2012 to 2017, more than 1200 disease outbreaks, including new or re-emerging infectious diseases, were recorded in 168 countries. In 2018, a further 352 infectious disease events, including Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) and Ebola virus disease (EVD), were tracked by WHO.Citation2 Although 2018 was a relatively safe year in terms of natural hazards, major climate-related disasters still directly affected over 58 million people, with an additional 3 million people harmed by geophysical disasters like earthquakes and volcanoes. Like most years, major events occurred in 2018 in every region of the world: deadly flooding in Kerala (India), Somalia, Nigeria, and Japan; massive storms in the United States, the Caribbean, Philippines, and China; wildfires in Australia, California (USA), and Greece; and drought conditions in Kenya, Afghanistan, Central America and Europe.Citation3 While widespread events have major impacts, smaller scale events also frequently affect communities and countries worldwide and in aggregate have significant health, economic, social, and environmental impacts.

TABLE 1. Number of People Directly Affected by Major Disasters Due to Natural Hazards; Average Total Direct Costs per Year: Climate-related and Geophysical Events; 2000–2018

Although concrete actions can be taken to prevent or reduce the hazards, exposures, and vulnerabilities inherent to disasters, governments and international agencies have not adequately invested in strengthening health emergency and disaster risk management systems, including a few key common goods for health (CGH) that address these challenges. The risks of all events, irrespective of scale, require effective management to avoid events, prevent them from becoming emergencies, or to prepare, respond, and recover from them as possible. The consequences of the inability to manage residual risks of emergencies are the widespread short-, medium-, and long-term impacts on human health (e.g. deaths, injuries, illnesses, and exacerbation of non-communicable diseases, mental health conditions, and disabilities) and effects on people’s livelihoods, community development and society at large.

In this paper, we outline what governments can and should do to provide CGH in key areas of health emergency and disaster risk management (EDRM) (see Appendix 1 for a glossary of health EDRM terms).Citation4 We estimate the costs involved in providing for the key health EDRM functions in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) where public resources are especially scarce. Since providing inputs alone is not sufficient to effectively implement health EDRM systems, we also explore the institutional arrangements needed to govern and implement health EDRM functions.

We focus on the CGH to address risks and consequences of human epidemics and events due to natural hazards (see Appendix 2 for the WHO classification of hazards). CGH, as defined by Yazbeck and Soucat in this series, are a set of population-based functions or interventions that require collective financing and are characterized by: (i) market failures, because they are public goods or generate large health externalities; and, (ii) strong potential to contribute to improvement in human life.Citation5 There are other hazards, exposures, vulnerabilities, and capacities that involve the health sector and common goods requiring state action; although they are not addressed in this paper, governments should consider including them in their overall risk management strategies and national budgets. For example, addressing antimicrobial resistance is a CGH that involves animal and human infections, livestock, food, pharmaceuticals, and healthcare systems, but is a topic that requires its own range of interventions that go beyond health EDRM systems; it is partly addressed in another paper in this series on global CGH by Yamey and colleagues.Citation6 Technological events (e.g. industrial hazards, air pollution events, infrastructure disruptions) should be part of an emergency and disaster risk management system that protects human health, but are not costed in this paper due to lack of available data and the heterogeneity of necessary approaches beyond health EDRM systems. Many of the factors that affect hazards and exposures related to those disasters associated with natural hazards also involve CGH and interventions beyond health EDRM systems, notably regulatory approaches for managing pollution (of air, water, and land), which are discussed in a separate paper in this series by Lo and colleagues.Citation7 Societal human-induced disasters (e.g. armed conflict, acts of violence, chemical, biological, radiological, nuclear, and explosive weapons, and financial crises) generate critical threats to human health that rely on health EDRM systems but also require measures well beyond health EDRM described in this paper. They are also addressed outside the 2005 International Health Regulations (IHR) and the Sendai Framework.Citation8,Citation9

For health EDRM, CGH interventions need to go beyond emergency response to address the full cycle of emergency management, including prevention, preparedness, response, and recovery. Interventions should also address the main components of risk, including hazards, exposures, vulnerability, and capacity (see ). Natural hazard-related events, including hydrological (e.g. floods), meteorological (e.g. storms and heatwaves), or climatological (e.g. droughts and wildfires) hazards, may be exacerbated by human activities that, in combination with exposure and vulnerabilities, increase the frequency and severity of events. Measures to prevent and mitigate these hazards, reduce exposures and vulnerabilities, and increase capacities should all be included among CGH interventions. In contrast, the hazard component of geophysical disasters (e.g. earthquakes and volcanoes) generally do not have origins related to human activity or are not known to be preventable—with the exceptions of hydraulic fracturing (“fracking”) and industrial wastewater disposal, which can cause seismic activity.Citation10

Health EDRM Functions are Common Goods for Health

Markets and civil society cannot be relied on to supply most health EDRM measures. Thus nearly all national governments have recognized their primary responsibility to finance and manage health EDRM functions through adoption of the IHR (2005) and the Sendai Framework. These two global agreements form the basis for epidemic preparedness and response and EDRM systems and articulate national governments’ responsibilities and commitments towards them.Citation8,Citation9 The IHR (2005) is a legally binding international agreement that outlines national governments’ responsibilities in the area of prevention and control of the spread of diseases internationally. The Sendai Framework specifies how governments should deliver and finance core functions of multisectoral EDRM, and details an approach to engage “all-of-society” and “all-of-state institutions” in these efforts. It aims towards a “substantial reduction of disaster risk and losses in lives, livelihoods and health.”Citation9 The IHR (2005) and the Sendai Framework present new opportunities and challenges for governments committed to providing the governance and institutional arrangements to support these approaches.

Many health EDRM functions depend on government interventions within and beyond the health sector. They often require fundamentally collaborative approaches that cross local and national boundaries and jurisdictions just as the hazards and their consequences do. Many EDRM interventions need to be organized around the nature of a hazard (e.g. floods, air pollution, or the spread of diseases that cross borders) or its consequences (e.g. voluntary movement of people or displacement). Thus government leadership to address emergencies—through policies, institutions, funding, and delivery of services—is necessary.

Commercial markets can play some important roles in epidemic preparedness, such as in the production of new vaccines, drugs, or products used to combat epidemics, but they fail to produce the full set of goods and services for health EDRM. Most LMICs do not have functional insurance markets, and while disaster insurance may provide for some recovery costs, particularly in high-income countries and for wealthier households and businesses, most of the costs of disaster are not insured even in high-income countries.Citation11 Further, markets can actually contribute in negative ways, particularly when they are poorly regulated. For example, private economic activities can degrade the physical environment, disrupt ecosystems, and contribute to global climate change, putting people in harm’s way in hazard-prone areas. Poor standards for housing and infrastructure increase the probability and severity of epidemics and the consequences of climate-related disasters.

Civil society frequently plays important roles in raising policy issues, identifying solutions, and being a partner in preventing, preparing, responding to, and recovering from disasters. Government activities can also contribute to the risks and their responses. However, government policy and regulatory intervention are especially critical to prevent or reduce the risks from environmental disruption. Government interventions are needed to provide the legal, institutional, and financial support, and to perform health EDRM functions, which only governments can provide.

Key Functions of Health EDRM as CGHs

Among the various components and functions described in the WHO Health EDRM Framework,Citation4 six reinforcing functions (shown in ) cut across all sectors and should be considered as CGHs: policy and coordination, taxes and subsidies, regulation and legislation, information collection, analysis and research, communications, and persuasion, and population services.Citation4,Citation12 The table also identifies key elements of those functions that should be implemented by the health sector; these include integrated disease surveillance and response (IDSR) to address biological events (epidemics) and other components of EDRM where the health sector plays specific roles, such as a public health emergency operations center (EOC).Footnotea We also include in our list of CGH other interventions directly linked to health EDRM that take place at health care facilities, including information and logistics systems needed for disease surveillance and response (e.g., reporting on IDSR target conditions and support for specimen collection and transport during epidemics), infection control at health facilities, and any supplies and equipment needed to support special treatment or isolation units and address surge capacity during responses and recovery.

TABLE 2. Description of Common Goods for Health (CGH) in Health Emergency Disaster Risk Management (EDRM)

Although we focus on the costs to national governments to provide the core health EDRM functions for which the health sector has primary responsibility, we recognize that additional investments are needed in other EDRM components, particularly related to all-hazards emergency preparedness and response and post-disaster recovery efforts. We also acknowledge that regional or global efforts are needed to fully address those hazards and exposures that span national boundaries, including epidemic diseases, mobile populations, climate-related disasters that affect large ecological zones, and emergencies for which the underlying causes are created by cumulative action across countries (e.g. air pollution-related causes).

Economic Evaluation of Health EDRM Systems

Few formal economic evaluations of health EDRM systems, and more specifically disease surveillance systems, have been conducted. The existing evaluations are limited in their scope of health outcomes examined, often do not account for the potential for large epidemics and face other technical limitations of economic assessments of surveillance systems.Citation13 In the field of disaster risk management, there is a body of cost-benefit analysis and other economic evaluations, but it focuses on individual interventions and specific hazards (e.g. flooding), rather than on a full EDRM system or addressing multiple hazards. Interventions that have had economic evaluations include structural changes to buildings and property, building codes and land use changes to reduce exposure to disasters, and behavioral interventions related to preparedness and warning systems. These are all more limited in scope than an EDRM system, and as such represent an underestimate of the benefits of such systems.Citation14–Citation16

Many methodological difficulties exist with cost-benefit analyses of EDRM focused on large-scale events. In particular, since the risk of large-scale events is characterized by low-probability and high-impact events, the results are dependent on estimates of risk and its variability. Nonetheless, cost-benefit studies typically show positive returns for risk reduction measures for specific scenarios; the average benefits are often found to be in the realm of four times the costs of avoided losses and with benefits as high as 100 times the cost.Citation14,Citation16,Citation17 In one comprehensive review of cost-benefit assessments of disaster risks, the benefits were greater for the more-frequent flood risks than for the less-common earthquake risk, but this was based on about 40 studies mostly related to flood risk prevention.Citation17

Institutional Arrangements to Foster Health EDRM

In addition to financing for the core inputs for health EDRM, effective governance and management are also needed, and these require appropriate institutional arrangements. In examining the institutional arrangements for health EDRM, it is useful to look beyond the structural aspects of a single organization to consider institutions as, per North’s definition, the sets of formal rules and informal conventions (“rules of the game”) that structure and constrain behaviors and enable choice and action.Citation18 We consider organizations to be “actors” with their own objectives, structures, and capabilities, and which operate under the broader institutional framework of society, in addition to creating their own rules, informal conventions, and enforcement mechanisms.Citation19–Citation21 The overall management of disasters can be regarded as a social-ecological system.Citation21 These complex EDRM systems: involve natural, economic, and social resources; are characterized by high levels of uncertainty; are susceptible to social, economic, biological, and ecologic risks, including periodic shocks; and, involve multiple actors with overlapping mandates and jurisdictions (polycentrism). In this paper, therefore, we examine three interacting institutional elements—rules, regulations, laws; behavioral norms; and, organizational structures—in the context of EDRM social-ecological systems.

Methodology

The economic analysis portion of this paper assesses the costs involved in establishing health EDRM functions in countries where they are currently lacking. Building on costing work conducted to project a price tag for the health-related Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), we included 67 LMICs in our sample.Citation22 We identify key functions of a health EDRM system with a granular level of detail to be able to estimate the resources needed to implement such systems; this represents a global benchmark never before attempted. Once these functions are specified, we determine the costs involved in establishing the key health EDRM functions in LMICs.Footnoteb We limit the scope to those functions that fulfil the conditions of CGH, including a demonstrated impact on human health with respect to managing the risks and consequences of emergencies and disasters and having direct involvement of the health sector in their financing. This analysis focuses on prevention, detection, and preparedness for emergencies, not recovery or response. More and greater detail on the methodologies employed are provided in Appendix 3.

Costs of Investments

All costs included in the analysis can be attributed to prevention, preparedness, or detection of emergencies. The costs of IHR implementation and other core capacities for health EDRM were derived from the WHO SDGs price-tag.Citation22 Costs for laboratory systems, emergency operation centers, community-based and facility-based surveillance systems, mobile emergency operation centers, and facility-level infection prevention and control were either made by adjusting from models used in the WHO SDG price-tag or by modeling based on country-level estimates. The health worker costs in the models include workers primarily assigned to disease surveillance and response functions, but not clinical care providers at health facilities. Community health workers who spend a significant share of their time on EDRM functions, particularly community engagement and event-based surveillance, are included.

We did not cover components that are essential to EDRM but fall under the responsibility of other sectors, such as road infrastructure (transport sector) or animal health (agriculture and wildlife sectors, among others).Footnotec We also recognize that the specific institutional arrangements for health EDRM in each country may result in additional costs, such as those related to regulatory enforcement or research needed to justify specific regulations.

The costs of disaster response are determined by the scale and intensity of an event and its probability of occurring, which is an exercise that goes beyond the scope of this paper. Similarly, we did not include the costs of clinical treatment, managing mass casualty events, insurance or re-insurance, or rebuilding infrastructure and systems after a disaster.

The IHR (2005) and the WHO Health Emergency and Disaster Risk Management Framework provide the basis for our determination of components of health EDRM systems that fall under the responsibility of the health sector.Citation8,Citation9 We used existing costing models and global guidance to identify benchmark levels for each component, broken down to identify quantities and prices to allow for cost estimates. Where previous costing analyses existed, they are included in the assessments of baseline levels for each country and were updated where possible. Where new modelling was required, assumptions on baseline levels were made according to the income level of each country. The difference between the baseline levels of country capacities and the benchmarks for each component then became the quantities for which each component’s costs were estimated.

The resulting analysis is a synthesis of existing models and publications on the costs of emergency prevention and preparedness. Many of our estimates build on the analysis of the price-tag for the health SDGs,Citation22 but we also add new components and data sources and go into greater detail than was covered in earlier work. We acknowledge that there are also other activities related to managing global risks and consequences of emergencies that should happen within individual countries but whose endpoints are goods of a supranational nature.Citation4 Examples include research and development for infectious hazards management, pandemic influenza, and global health security. The focus of this paper, however, remains provision of a health EDRM system for the benefit of the population within each country.

Our analysis includes the costs of activities described in the last column in . We present the total costs to set up and operate functional health EDRM systems (beyond regular health care services) in 67 countries for one year. We accounted for the EDRM systems that already exist within the included countries, and only present the additional resources required for each country to have a fully-functional EDRM system.

In estimating the additional costs, each component includes a series of inputs with specific prices that were multiplied by the quantities needed to reach our preset targets. For this study, only market-traded inputs—such as costs of employing additional human resources, purchasing equipment or medical supplies, and building infrastructure—are included. For goods whose prices vary across countries, we used the local prices from WHO’s CHOICE database.Citation23 All capital costs are accounted for in the cost projections from a financial perspective and considering the total cost of their creation (regardless of payer or financing model, and, in the cases of work like construction, the costs that in reality may span over many years). The costs presented here are therefore the sum of the financial costs of implementing interventions in a single year. All costs are expressed in 2014 United States dollars (USD). Projected investments are presented as total and per capita estimates, representing the amounts needed to be spent in countries to create and operate health EDRM systems, and assume that current spending and system capacities do not decrease.

Institutional Options

The second aspect of this paper is a discussion of optimal institutional arrangements for health EDRM. We conducted a narrative literature review to identify how countries have organized health EDRM activities, the types of formal rules, behavioral norms, and organizational structures they used, and particularly what has been learned from comprehensive approaches involving all-of-society and all-of-state institutions. As few LMICs have developed full health EDRM systems, they have not been rigorously evaluated in the peer-reviewed literature. Therefore, we did not attempt a systematic review to identify representative results.

Further, we expect that health EDRM designs and effectiveness are dependent on the specific contexts. We focused our review on case studies of health EDRM in the published and grey literature, as well as published reviews that examine governance and management arrangements for disaster risk management and the social-ecological systems that characterize them. General principles and lessons learned were identified about how to use all-of-society and all-of-state institutions approaches to address the full spectrum of health EDRM activities, along with insights about how formal rules, informal behavioral norms, and organizational structures can be used to improve governance and implementation.

Results

Costs of Health EDRM

presents the results of the costing analysis. It shows the sum of costs for additional basic capital items and one year of recurrent costs for 67 countries, grouped according to income level, weighted by population, and calculated on a per capita basis. The total additional cost of capital expenditures is calculated at $12.3 billion. (In reality, these capital costs would likely be spread out over several years.) The projected additional recurrent costs for all countries was $13.8 billion per year. Low-income countries have a higher projected per capita cost ($4.33 capital and $4.16 recurrent), while lower costs were estimated for upper middle-income countries ($3.00 capital and $1.41 recurrent costs).

TABLE 3. Additional Costs to Finance Health Emergency and Disaster Risk Management Common Goods for Health, by Country Income Level, USD 2014

The additional costs of financing health EDRM are further broken down in two ways: first by each of the six CGH functions and then by country groups, as shown in . Among the CGH functions, the most expensive are Population Services ($14.5 billion), followed by Communications and Persuasion ($4.24 billion) and Information Collection, Analysis, and Research ($3.88 billion). In each category, the additional costs are greater for low-income countries than for upper-middle-income countries.

TABLE 4. Additional Costs to Finance Health EDRM, by Common Goods for Health, 2014 USD

Institutional Considerations for Health EDRM

Health EDRM Organizational Approaches

There are many ways that governments can organize themselves to fulfill the six key CGH functions for delivering health EDRM (listed in ). In most cases, the health sector is primarily responsible for leading risk management of epidemic-related hazards. The health sector also often plays a key role with respect to other risks, and a leading role in areas where it has functional capabilities and mandates (e.g. disease- and healthcare-related issues). Other Ministries (e.g. Civil Affairs) or cross-Ministry organizations (e.g. national disaster management agencies) tend to focus on leading multisectoral emergency and disaster risk planning and management.

Often an emergency, whether an epidemic or some other disaster, prompts re-organization within the government to better manage health EDRM. For example, Liberia established a National Public Health Institute after the 2014–2016 Ebola virus disease epidemic. Likewise, the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention (China CDC) was established in 2002 in the wake of the avian influenza epidemic in recognition of the need to respond to the population’s changing epidemiology. The China CDC was based on the models of both the Shanghai (China) Municipal CDC (established in 1998) and the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US CDC) (established in 1946). Shortly after its founding, the China CDC was called on to respond to a SARS epidemic and further developed its organization during that response. In several Pacific Island nations, all-hazards disaster risk management organizations have been similarly established in response to major disasters.

All-of-State Institutions & All-of-Society Approaches

The need to work across sectors becomes obvious upon considering how epidemics and other disasters involve and affect many aspects of society beyond the health sector, including finance, industry, commerce, security, emergency services, and environment. Considering the plethora of government agencies and jurisdictions these sectors involve, this coordination is notoriously difficult to do. Cross-government work includes coordination, division of responsibilities, and integration of activities along numerous dimensions, including:

Functional divisions (government policy and oversight, public health, health care, commerce, and financing and insuring against loss and for recovery);

Organizational units (police services, fire services, ambulance services, and hospitals);

Hierarchical divisions (national, state, and local); and,

Geographies (jurisdictions and regions).Citation24

Although no “one-size-fits-all” organizational model exists that is suitable for all countries, there are important general considerations for how to manage all-of-society and all-of-state institutions approaches to health EDRM. An all-of-society approach necessitates the involvement of all levels of government, as well as businesses, communities, and civil society. The approach builds on the principle of shared responsibility in societies to attend to and be inclusive of all people, including the poor and vulnerable segments of society. For health systems, an all-of-society approach requires addressing the risks and needs of all people, engaging them in designing and conducting health EDRM from prevention and preparedness through response and recovery.

Particular attention is needed to ensure gender-responsiveness in health EDRM as well as to reduce barriers to participation and access for women, elderly people, children, people with disabilities, poor people, and other segments of populations that tend to be most at risk and vulnerable before, during, and after emergencies and disasters.Citation25 For example, numerous studies have demonstrated that women are more exposed to climate-related disasters and are more vulnerable to their effects, in part because of discriminatory norms that limit women’s access to decision-making processes and resources made available for disaster preparedness and response.Citation25–Citation27

Community engagement has frequently been one of the most critical and most neglected dimensions of public health; meaningful engagement of at-risk communities and people in emergency prevention, preparedness, surveillance and response will be done differently in different countries. In the 2014–2016 West Africa Ebola epidemic, a lack of community engagement in epidemic preparedness and during the early phases of the epidemic fueled distrust, violence, and ultimately the spread of the disease.Citation28 Effective community engagement then became critical to ending the epidemic, demonstrating the pivotal importance of fostering trust in public institutions and facilitating the role of communities in outbreak response. That situation also highlighted the need to better understand and enhance community engagement in pre-epidemic, crisis, and recovery phases.Citation29,Citation30

Designing Adaptive Institutions

Adaptive institutions use formal rules, informal behavioral norms, and flexible organizational structures and management strategies. They are integrated with broader processes and are widely considered to be best suited for managing complex social-ecological systems.Citation21,Citation31,Citation32 Adaptive institutions enable organizations to adjust to encourage individuals to act in ways that maintain or move towards a desirable state. They facilitate participatory, inclusive and collaborative action and are accountable, transparent, flexible, risk-tolerant, self-assessing, and evolving.Citation21

Key factors that contribute to adaptive institutions include: working through multiple stakeholders and networks of relationships; depending on management approaches that encourage learning and deliberation; ensuring accountability and enforcement of rules; developing and using social capital (particularly to link complementary community-based institutional arrangements with government); and, supporting capable leaders at all levels of the system to mobilize resources towards common purposes. Adaptive institutions move away from viewing themselves as “static, rule-based, formal and fixed organizations with clear boundaries,” instead aiming to be “more dynamic, adaptive and flexible for coping with future climatic conditions.”Citation33 Whatever the organizational structure of health EDRM, fostering adaptive institutions and management practices will be essential to making health EDRM work well.

Specific principles and practices for the governance and management of health EDRM have been established in accordance with the IHR (2005) and Sendai Framework.Citation8,Citation9 These include the following approaches, which underpin the WHO Health EDRM Framework: a risk-based approach to identify levels and causes of risk and how to mitigate them; a comprehensive scope incorporating prevention, preparedness, response, and recovery; including all hazards rather than fragmenting separate approaches for individual hazards; promoting multisectoral and multidisciplinary collaboration; having an inclusive people- and community-centered orientation; using the whole health system; and, being guided by ethical principles.Citation33,Citation34 A review of multiple case studies of EDRM reveals a number of specific examples of enforceable rules, behavioral norm changes, and organizational structures that have been effective in different settings, as outlined in .Citation35

TABLE 5. Examples of Institutional Approaches Shown to Be Effective in Emergency and Disaster Risk Management

Discussion

This analysis shows that governments have considerable scope to establish an essential set of capabilities to deliver on CGH to prevent and mitigate against epidemics, disasters, and other emergencies. Our analysis indicates that health EDRM structures are affordable to establish at a cost of $12.3 billion across all LMICs, and an average of $2.48 per capita for annual operations. The main components of health systems are the key cost drivers, as the health workforce, infrastructure, laboratory systems, medicines, and medical supplies necessary for health EDRM are more generally required to address routine health needs of the population.

Low-income countries are expected to have the highest additional per capita costs ($4.33 capital and $4.16 recurrent costs), reflecting the greater gap between their current situations and fully functional health EDRM systems. Our expectation is that the calculated level of funding required is well within the anticipated fiscal space for health in virtually all LMICs. We recognize that there are other competing priorities in the health sector of each country that are often prioritized; however, in our opinion, these health EDRM CGH have a truly compelling rationale for public financing.Citation12

We also demonstrated that governments are best placed to fulfill health EDRM functions that are CGH. As detailed in , the six CGH functions in health EDRM require the kind of legislative and policy frameworks that only governments can implement. Driving and supplying investments in the people, infrastructure, and systems needed to operationalize functional health EDRM systems is the purview of governments, which are responsible for preventing and mitigating emergencies affecting their people’s health.

As described by Yazbeck and Soucat,Citation5 the costs of epidemics and other disasters are increasing and dwarf the costs of health EDRM. This includes about $170 billion per year in direct costs to respond to large disasters due to natural hazards (), and the social costs of large-scale disasters are typically greater than the direct costs.Citation36 Furthermore, numerous small scale disasters occur annually that in aggregate are similarly costly. The costs of global pandemics and other epidemics are also massive. The National Academies of Medicine estimated that pandemic diseases cause annual losses averaging $60 billion per year, with a potential to reach $120 billion per year when including economic and social costs.Citation37 More recently, Fan and colleagues estimated that influenza pandemics alone could cost the global economy approximately 0.6% of GDP per year, with greater effects in LMICs.Citation38 In comparison to $26.1 billion in annual recurrent costs for health EDRM, the annual costs of disasters are approximately 20-fold larger, totaling more than $500 billion (including direct economic and indirect social costs of large disasters from natural hazards, the costs of smaller disasters, and the direct and indirect costs of epidemics). Furthermore, the value in terms of preventing additional social costs may ultimately be even greater than the monetary savings, as health EDRM serves to preserve and build community capabilities, strengthen public institutions, and build trust among communities, government, and business.

Unanswered Questions

There remain many important gaps in the data, knowledge, and experiences related to ensuring that the CGH described here are fully-funded and well-implemented. Simply allocating funds towards health EDRM will not suffice—to ensure that funds are used effectively, both research and adaptive institutions are needed to design and implement EDRM. An initial set of research themes for health EDRM has been proposed that involves multi-stakeholder and interdisciplinary approaches to help define the field and build evidence that contributes to policies and standards for comprehensive health EDRM.Citation39 Generating concrete information about the economic and social benefits obtained through health EDRM will rely on getting access to more complete and reliable data on the economic and social costs of intervention. It will also require new analytical models that can account for the uncertainties of risk, alternative implementation strategies, and the multiple health and social outcomes produced by health EDRM systems. More specifically, prospective and quasi-experimental evaluations of comprehensive health EDRM interventions are needed, as presently these are missing from the literature.

Studying these issues requires enhancing and disseminating disaster vulnerability assessment instruments that allow physical, systemic, social, economic, and institutional vulnerabilities to be assessed together in an integrated manner. In this paper we focused on CGH in the health sector, but this should be expanded to address related issues, such as zoonotic diseases that affect both animals and humans. The “One Health” approach requires the integration of public health, animal health, and ecosystems.Citation40

Another challenging issue is developing integrated approaches to all-hazards health EDRM. This will require building capacity within the scientific community to undertake multi-disciplinary approaches. This is particularly needed to better understand the complex linkages among different types of hazards, vulnerabilities, capacities, and impacts, as well as the interventions that can prevent their causes (e.g. reducing climate change and air pollution), and assessments of efforts to mitigate against multiple hazards rather than single types of disasters. More experience and research on adaptive management, institutions, and governance is needed to learn how different institutional arrangements lead to effective implementation of interventions that involve multiple components, organizations, and disciplines. WHO has been supporting approximately 100 countries to conduct after-action reviews, simulation exercises, and Joint External Evaluations of IHR Core Capacities. These peer-to-peer review exercises help governments to systematically identify issues and build capacity to implement the IHR (2005).Citation41 These activities provide a platform for further evaluation and learning about IHR capacities and broader health EDRM institutional arrangements and their adaptations.

A wide range of innovative interventions in EDRM also need to be tested, such as providing safe havens or decentralizing distribution of disaster response materials. These and other unconventional approaches can help to reduce risks and build resilience among those communities that cannot be removed or relocated from risk areas (e.g., where they are vulnerable to earthquakes or cyclones). Although effects can vary depending on the type of disaster, the population affected, and the economic sectors interrupted, poorer countries and poorer households within countries are most adversely affected by disasters and are less able to recover from them.Citation42,Citation43 Another priority must be developing a range of financing instruments to provide different types and levels of funding for people and communities affected by emergencies and disasters.

Limitations

This study was limited by the availability of costing models of health EDRM functions and thus used purely normative costing. Another problem was the limited availability of reliable cost data on spending on health EDRM, particularly since so few countries have fully functional health EDRM systems. The data used in this study were comprised of expenditure reports (used to identify prices and quantities of internationally-traded goods) and known country-specific cost data on the infrastructure, labor, supplies, and operational costs needed for fulfilling the health EDRM functions.

Another possible limitation arises from the narrative literature review of institutional arrangements, which may have been prone to bias. The purpose of the review was to provide a broad perspective on early lessons from experiences rather than to represent their effectiveness. As national health EDRM systems become better established and take on greater multi-hazard responsibilities, especially related to disasters from natural causes, more in-depth evaluations of governance, management arrangements, and particularly how they learn and adapt will be as instructive as formal evaluations of effectiveness.

There is also a serious shortage of economic analysis of health EDRM capacities and measures, including the more specific integrated disease surveillance and response components. Risk-based economic analyses of comprehensive health EDRM interventions are needed, especially those that include direct and indirect economic costs, as well as social costs. While it is not known how much health EDRM actions would avert the costs of epidemics and other hazardous events, the costs of the feasible CGHs are clearly comparatively meager, representing as they do a fraction of the conservative estimates of the costs of epidemics and other disasters due to natural causes.

Conclusion

This paper presents a clear case for governments to invest in CGH in health EDRM. The annual costs of not developing health EDRM in LMICs—namely, the costs of epidemics and disasters due to natural hazards—are at least 20-fold greater than the cost of the necessary additional expenditures on health EDRM. We have described the key functional areas for investment and action in health EDRM, offering clear steps that are affordable for governments, as well as areas where development agencies and others’ financial and technical support could be effective. The costs for providing key basic health EDRM capabilities range from $0.62 to $20.90 per capita annual recurrent costs among 67 LMICs. Compared to the related economic and social costs of not intervening in health EDRM, the demonstrated economic and social value should compel governments to invest in these common goods for health.

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

[a] We note that the provision of individual healthcare is managed differently across countries and is not considered as a CGH.Citation12 Healthcare provision often involves a combination of government, private for-profit and non-profit organizations, with different mixtures of public and private financing arrangements. Governments will want to ensure that basic clinical preventive and treatment services are provided during an epidemic or natural disaster, whether through public financing or direct provision of health care. However, in this paper we do not include any additional costs of health care delivery during emergency and disaster response and recovery.

[b] No costs for High Income Countries (HICs) are included, although all countries experiencing disasters can identify ways to improve the functioning of their EDRM systems, as demonstrated during the avian flu epidemic in East Asia. However, this analysis identifies needs related to EDRM that should be financed globally, and these are readily financeable by all HICs.

[c] For example, we cost a basic model for a permanent multi-hazard national health EOC, typically set up in Ministries of Health or within national the public health agency to manage health emergencies, with minimum capacity to add field-based EOCs in response to an emergency.Citation44 We do not include more advanced supplies or laboratory infrastructure that countries with more resources could afford, or a multisectoral EOC that would be located in a Ministry outside health.

References

- Centre for Research on the Epidemiology of Disasters (CRED). EM-DAT: the emergency events database. Louvain (Belgium): Université catholique de Louvain (UCL); 2010. [accessed 2019 Mar 15]. www.emdat.be.

- World Health Organization. Disease outbreaks by year. Geneva (Switzerland): World Health Organization; 2019. [accessed 2019 Mar 31]. http://www.who.int/csr/don/archive/year/en/.

- Wallemacq P, House R. Economic losses, poverty & disasters 1998-2017. Centre for Research on the Epidemiology of Disasters (CRED), United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction (INISDR); 2018. [accessed 2019 Jun 14]. https://www.unisdr.org/we/inform/publications/61119.

- World Health Organization. Health emergency and disaster risk management framework. Geneva (Switzerland): World Health Organization; 2019. [accessed 2019 Aug 4]. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/326106/9789241516181-eng.pdf.

- Yazbeck AS, Soucat A. When both markets and governments fail health. Health Syst Ref. 2019;5(4):268–279. doi:10.1080/23288604.2019.1660756.

- Yamey G, Jamison D, Hanssen O, Soucat A. Financing global common goods for health: when the world is a country. Health Syst Ref. 2019;5(4):334–349. doi:10.1080/23288604.2019.1663118.

- Lo S, Corvalan C, Gaudin S, Earle AJ, Hanssen O, Prüss-Ustün A, Neira M, Soucat A. The case for public financing of environmental common goods for health. Health Syst Ref. 2019;5(4):366–381.

- World Health Organization. International health regulations (2005) – second edition. Geneva (Switzerland): World Health Organization; 2008. [accessed 2019 Jun 14]. https://www.who.int/ihr/publications/9789241596664/en/.

- United Nations. Sendai framework for disaster risk reduction 2015-2030. Geneva (Switzerland): UNISDR; 2015. [accessed 2019 Jun 14]. https://www.unisdr.org/we/coordinate/sendai-framework.

- Yoon CE, Huang Y, Ellsworth WL, Beroza GC. Seismicity during the initial stages of the uy-Greenbrier, Arkansas, earthquake sequence. JGR Solid Earth. 2017;122(11):9253–74. doi:10.1002/2017JB014946.

- Munich Re. A stormy year – natural disasters in 2017. Munich (Germany): Munich Re; 2018. [accessed 2019 Jun 14 March 12]. https://www.munichre.com/topics-online/en/climate-change-and-natural-disasters/natural-disasters/topics-geo-2017.html

- Gaudin S, Smith PC, Soucat A, Yazbeck AS. Common goods for health: economic rationale and tools for prioritization. Health Syst & Ref. 2019;5(4):280–292. doi:10.1080/23288604.2019.1656028.

- Herida M, Dervaux B, Desenclos J-C. Economic evaluations of public health surveillance systems: a systematic review. Eur J Public Health. 2016;26(4):674–80. doi:10.1093/eurpub/ckv250.

- Moench M, Mechler R, Stapleton S. Information note no. 3: costs and benefits of disaster risk reduction. Background paper prepared for: UNISDR High Level Dialogue, Global Platform on Disaster Risk Reduction; 2007 June 5-7. Geneva (Switzerland). [accessed 2019 Aug 12]. https://www.unisdr.org/files/1084_InfoNote3HLdialogueCostsandBenefits.pdf.

- Hawley K, Moench M, Sabbag L. Understanding the economics of flood risk reduction: a preliminary analysis. Boulder (CO): Institute for Social and Environmental Transition-International; 2012.

- Mechler R. Reviewing estimates of the economic efficiency of disaster risk management: opportunities and limitations of using risk-based cost–benefit analysis. Nat Hazards. 2016;81:2121–47. doi:10.1007/s11069-016-2170-y.

- Foresight Reducing risks of future disasters: priorities for decision makers. Final project report. London (UK): The Government Office for Science; 2012.

- North DC. Institutions, institutional change and economic performance. New York (NY): Cambridge University Press; 1990.

- Khalil EL. Organizations versus institutions. J Inst Theor Econ. 1995;151:445–66.

- Hodgson G. What are institutions? J Econ Issues. 2006;40(1):1–25. doi:10.1080/00213624.2006.11506879.

- Koontz TM, Gupta D, Mudliar P, Ranjan P. Adaptive institutions in social-ecological systems governance: a synthesis framework. Environ Sci Policy. 2015;53:139–51. doi:10.1016/j.envsci.2015.01.003.

- Stenberg K, Hanssen O, Edijer -T-T-T, Bertram M, Brindley C, Meshreky S, Rosen JE, Stover J, Verboom P, Sanders R, et al. Financing transformative health systems towards achievement of the health sustainable development goals: a model for projected resource needs in 67 low-income and middle-income countries. Lancet Glob Health. 2017;5:e875–87. doi:10.1016/S2214-109X(17)30263-2.

- WHO-CHOICE. Tables of costs and prices used in WHO-CHOICE Analysis. Geneva (Switzerland): World Health Organization. 2019. [accessed 2019 Jun 14]. https://www.who.int/choice/costs/en/.

- Alexander D. Disaster and emergency planning for preparedness, response, and recovery. Oxford research encyclopedia of natural hazard science. New York (NY): Oxford University Press. 2015. doi: 10.1093/acrefore/9780199389407.013.12.

- Eastin J. Climate change and gender equality in developing states. World Dev. 2018;107:289–305. doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2018.02.021.

- Neumayer E, Plümper E. The gendered nature of natural disasters: the impact of catastrophic events on the gender gap in life expectancy, 1981–2002. Ann Am Assoc Geogr. 2007;97(3):551–66. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8306.2007.00563.x.

- World Health Organization. Gender, climate change and health. Geneva (Switzerland): World Health Organization; 2014.

- Peters DH, Nyenswah T, Engineer CY. Leadership in times of crisis: the example of Ebola virus disease in Liberia. Health Syst Ref. 2016;2:194–207. doi:10.1080/23288604.2016.1222793.

- Wilkinson A, Parker M, Martineau F, Leach M. Engaging ‘Communities’: anthropological insights from the West African Ebola epidemic. Phil Trans R Soc B. 2017;372:20160305. doi:10.1098/rstb.2016.0305.

- Kirsch TD, Moseson H, Massaquoi M, Nyenswah TG, Goodermote R, Rodriguez-Barraquer I, Lessler J, Cumings D, Peters DH. Impact of interventions and the incidence of ebola virus disease in Liberia-implications for future epidemics. Health Policy Plan. 2016:1–10. doi:10.1093/heapol/czw113.

- Fabricius C, Cundill G. Learning in adaptive management: insights from published practice. Ecol Soc. 2014;19(1):29. doi:10.5751/ES-06263-190129.

- Westgate MJ, Likens GE, Lindenmayer DB. Adaptive management of biological systems: a review. Biol Conserv. 2013;158:128–39. doi:10.1016/j.biocon.2012.08.016.

- TERI, IISD. Designing policies in a world of uncertainty, change, and surprise: adaptive policy-making for agriculture and water resources in the face of climate change. Executive summary. Winnipeg (Canada): International Institute for Sustainable Development, New Delhi (India): The Energy and Resources Institute. 2006. [accessed 2019 Jun 14]. https://www.iisd.org/pdf/2006/climate_designing_policies_sum.pdf.

- World Health Organization. Health emergency and disaster risk management framework: policy guidance. Forthcoming. Geneva (Switzerland): World Health Organization; 2019.

- Tompkins EL, Penning-Rowsell E, Parker D, Platt S, Priest S, So E, Spence R. Institutions and disaster outcomes: successes, weaknesses and significant research needs – report prepared for the Government Office of Science, Foresight project ‘Reducing Risks of Future Disasters: Priorities for Decision Makers’. London (UK): Government Office of Science, 2012.

- Deloitte Access Economics. The economic cost of the social impact of natural disasters. Sydney (Australia): Australian Business Roundtable for Disaster Resilience & Safer Communities, 2016.

- National Academy of Medicine. The neglected dimension of global security: a framework to counter infectious disease crises. Washington (DC): The National Academies Press; 2016.

- Fan YY, Jamison DT, Sommer LH. Pandemic risk: how large are the expected losses? Bull World Health Organ. 2018;96:129–34. doi:10.2471/BLT.17.206417.

- Lo STT, Chan EYY, Chan GKW, Murray V, Abrahams J, Ardalan A, Kayano R, Yau JCW. Health Emergency and Disaster Risk Management (Health-EDRM): developing the research field within the Sendai framework paradigm. Int J Disaster Risk Sci. 2017;8:145–49. doi:10.1007/s13753-017-0122-0.

- World Bank. People, pathogens, and our planet. Volume 1: towards a one health approach for controlling zoonotic diseases. Report no. 50833-GLB. Washington (DC): World Bank Group, 2010.

- World Health Organization. Strengthening health security by implementing the International Health Regulations (2005): Joint External Evaluation (JEE) mission reports. Geneva (Switzerland): World Health Organization. 2019. [accessed 2019 Aug 2]. https://www.who.int/ihr/procedures/mission-reports/en/.

- Hallegatte S, Bangalore M, Bonzanigo L, Fay M, Kane T, Narloch U, Rozenberg J, Treguer D, Vogt-Schilb A. Shock waves: managing the impacts of climate change on poverty. Climate change and development. Washington (DC): World Bank. 2016. doi: 10.1596/978-1-4648-0673-5.

- Loayza NV, Olaberría E, Rigolini J, Christiaensen L. Natural disasters and growth: going beyond the averages. World Dev. 2012;40(7):1317–36. doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2012.03.002.

- World Health Organization. Framework for a public health emergency operations centre. Geneva (Switzerland): World Health Organization; 2015.