Abstract

“Global functions” of health cooperation refer to those activities that go beyond the boundaries of individual nations to address transnational issues. This paper begins by presenting a taxonomy of global functions and laying out the key value propositions of investing in such functions. Next, it examines the current funding flows to global functions and the estimated price tag, which is large. Given that existing financing mechanisms have not closed the gap, it then proposes a suite of options for directing additional funding to global functions and discusses the governance of this additional funding. These options are organized into resource mobilization mechanisms, pooling approaches, and strategic purchasing of global functions. Given its legitimacy, convening power, and role in setting global norms and standards, the World Health Organization (WHO) is uniquely placed among global health organizations to provide the overarching governance of global functions. Therefore, the paper includes an assessment of WHO’s financial situation. Finally, the paper concludes with reflections on the future of aid for health and its role in supporting global functions. The concluding section also summarizes a set of key priorities in financing global functions for health.

Introduction: The Price Tag for Critical Global Functions

On December 3, 2013, The Lancet Commission on Investing in Health (CIH) concluded its report, Global Health 2035: A World Converging within a GenerationCitation1 with a “wake-up call” to the international community. The CIH stated: “The global health system as it is presently configured is not directing its financing to functions that need strengthening if we are to achieve dramatic health gains by 2035.”Citation1 The functions or activities that needed strengthening, argued the CIH, are “global functions,” or activities that address transnational issues that go beyond the boundaries of individual nations. The CIH classified these global functions into three types:

Provision of global public goods. Examples include knowledge generation and sharing and research and development (R&D) of new tools to tackle neglected diseases.

Management of negative regional and global cross-border externalities. Examples include outbreak preparedness, tackling antimicrobial resistance (AMR), management of air pollution, and curbing the global marketing of unhealthy substances.

Fostering of global health leadership and stewardship. Examples include convening for negotiation and global cross-sectoral advocacy.

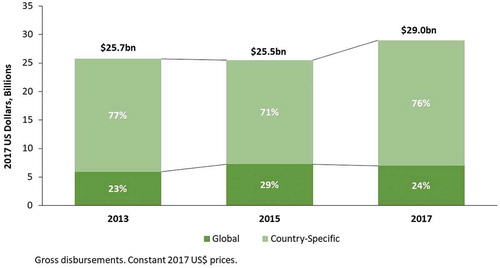

FIGURE 1. Donor Funding for Global Vs. Country-specific Functions, Years 2013, 2015, and 2017.

Source: Ref. Citation3. © 2019 The Authors. All Rights Reserved.

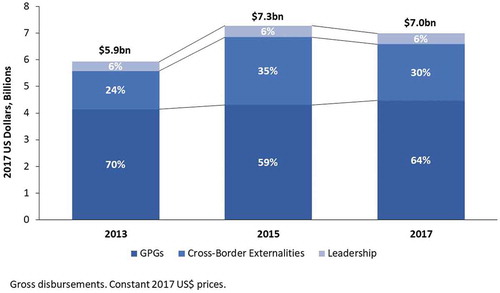

FIGURE 2. Donor Funding for Global Functions by Global Function Category, Years 2013, 2015, and 2017.

Source: Ref. Citation3. © 2019 The Authors. All Rights Reserved.

At least in theory, such global functions can and should be collectively funded as common goods for health (CGH), mostly by public sources complemented by private and philanthropic sources by and for all countries (whether high-, middle-, or low-income). In practice, a large share of funding for such functions has come from official development assistance (ODA) for health.Citation2 (Flows of ODA to global functions in recent years are the focus of a related paper in this special issue.Citation3) Our paper focuses on the role of ODA in supporting global functions. The CIH made a key distinction between development assistance for health (DAH) that supports global functions, bringing transnational (regional or global) benefits, and DAH that is given to an individual country to support disease control activities (e.g., reducing maternal mortality) in that country alone. An example of the latter type of activity—so-called “country-specific functions”—is funding given to a country with constrained national capacity to support a national maternal or child health program. This paper focuses on global functions. shows how the term global functions relates to the term CGH, which is being used across this series.

TABLE 1. How the Term “Common Goods for Health” Relates to the Term “Global Functions”

Thirteen days after the publication of Global Health 2035, an 18-month-old boy in Meliandou, Guinea, developed fever, black stools, and vomiting, and died two days later. He was later identified as the index case in West Africa’s 2014–2016 Ebola outbreak.Citation4 Compared to previous Ebola outbreaks, the West Africa outbreak spread more rapidly and widely and killed many more people. There are many reasons why it took so long to control the epidemic, including weak public health infrastructure, a high degree of cross-border movement of infected people, and high-risk funeral and burial practices in West Africa.Citation5 Under-funding of global functions made it especially hard to control the epidemic. Due to the large financing gap for product development for neglected diseases and emerging infections, no disease-specific control tools were available—there was no Ebola vaccine, therapeutic, or rapid diagnostic test. The existence of such tools could have helped to contain the epidemic. Regional surveillance and preparedness systems performed poorly. And the report of the Ebola interim assessment panel, a panel of experts convened by WHO, identified weaknesses in WHO’s leadership of the Ebola response and concluded that “WHO must re-establish its pre-eminence as the guardian of global public health.”Citation6

Why have global functions been under-funded? And why did the CIH make the case that more donor financing should be directed to global functions? Both markets and governments have natural incentives to under-invest in global collective functions. Markets under-invest because there is no clear demand. Governments under-invest due to the so-called “free-rider problem,” a type of market failure in which those who benefit from public goods do not pay for them. Yet, the health and economic risks and benefits of these functions are transnational, warranting co-financing by the global community. When it comes to global public goods (GPGs, one of the three types of global functions), the economist William Nordhaus notes: “If problems arise for global public goods, such as global warming or nuclear proliferation, there is no market or government mechanism that contains both political means and appropriate incentives to implement an efficient outcome.”Citation7

This paper examines the global functions of the international health enterprise in five further sections. Section 2 presents a taxonomy of global functions. Section 3 summarizes some of the key value propositions of investing in global functions (because the value of investing in CGH is discussed in detail elsewhere in this series, our summary is brief and focuses on global CGH). Next, in Section 4, the paper examines recent funding flows to global functions and the large estimated price tag. Given that existing financing mechanisms have not closed the gap, Section 5 proposes a suite of options for directing additional funding to global functions and discusses the overall governance of such funding. These options are organized by the three main functions of health financing: resource mobilization mechanisms, pooling approaches, and strategic purchasing of global functions. In-depth analyses of the political feasibility of the various options laid out in Section 5 are outside the scope of this paper. We also do not estimate their chances of success or the amount of funding that each mechanism could raise. Since WHO is uniquely placed among global health organizations to provide the overarching governance of global functions, through its legitimacy, convening power, and role in setting global norms and standards, Section 5 includes an assessment of WHO’s financial situation. Finally, in Section 6, our paper concludes with reflections on the future of aid for health and its role in supporting global functions. This concluding section also summarizes a set of key priorities in the financing of global functions for health.

Given our focus on ODA, our primary audience is governments acting through bilateral and multilateral funders of health. We believe our paper will also be of interest to all actors who could potentially fund global CGH. Other papers in this series provide an in-depth analysis of the case for investing in CGH (“Common Goods for Health: Economics Rationale and Tools for Prioritization”Citation8) and an analysis of the politics of motivating actors to invest in CGH (“When do Governments Support Common Goods for Health?”Citation9), and so we do not cover these important topics in depth here.

A Taxonomy of Global Functions

shows the taxonomy of global functions proposed by the CIH, organized in the three major categories and with a detailed list of examples of each. Schäferhoff and colleagues have shown the practical value of this taxonomy by using it to determine the relative breakdown of international financing into global versus country-specific functions.Citation10 While all kinds of R&D that lead to freely and openly available knowledge can be considered a GPG, in this paper we mostly focus on a sub-set of such R&D: product development for neglected diseases. We do so because of “the limited purchasing power of both governments and patients in the countries where such diseases predominate; unlike for other diseases, there is no positive spillover from drug development targeted at more affluent markets.”Citation11

TABLE 2. Taxonomy of Global Functions

An important concept that arises from the definition and taxonomy of global functions relates to the geography of where financing can be channeled and spent in support of such functions. While the benefits of supporting global functions are transnational, the investments can be made at three main levels:

The global (supranational) level. Financial support for global functions can be channeled to supranational entities or institutions. Examples include funding for (i) global vaccine stockpiles, such as the global stockpile of oral cholera vaccines established by WHOCitation12; (ii) global mechanisms to develop medical products (e.g., medicines, vaccines, and diagnostics) to control neglected diseases and emerging infections, such as the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations (CEPI), which in turn funds development of new vaccines to prevent and contain outbreaksCitation13; (iii) pandemic emergency response, such as the World Bank’s Pandemic Emergency Finance Facility (the PEF)Citation14; (iv) reducing cross-border transmission of drug-resistant tuberculosis (TB) and other pathogens, pollution, harmful substances, and counterfeit health products, such as through strengthening WHO and other global supranational efforts that work to reduce such transmission (e.g., the Global Health Security Agenda); (v) developing global norms and standards for safety and quality of care; and (vi) generating a clearinghouse of global knowledge and a subsequent global surveillance function.

The regional level. As mentioned, global functions have transnational benefits that may extend regionally or globally. Examples of financial support for global functions channeled into regional entities supporting low-income countries (LICs) and middle-income countries (MICs) that produce transnational regional benefits include funding for: (i) the Coalition for African Research and Innovation, a regional research and development platformCitation15; (ii) the Africa Centres for Disease Control and Prevention, which supports all countries in the Africa region to “improve surveillance, emergency response, and prevention of infectious diseasesCitation16; and (iii) the many regional malaria elimination initiatives that have been established in southern Africa, the Arabian Peninsula, Asia Pacific, Eastern Europe, and Latin America.Citation17

The country level. Country financing is an important way to support global functions. Examples include financial support from both domestic and donor funding, spent within individual LICs or MICs, to: (i) tackle drug-resistant TB; (ii) eliminate malaria; or (iii) conduct pandemic preparedness activities that are outside the realm of “usual” health system strengthening (HSS) activities in countries that are at risk (e.g., preparedness activities such as stockpiling protective gear or surveillance of wildlife reservoirs). In these situations, funding spent at the country level has benefits that extend beyond the nation’s boundaries. Funding spent in high-income countries could also support global functions; an example is US government funding to support vaccine research for neglected diseases and emerging infections (e.g., Ebola vaccine development) conducted at the US National Institutes of Health.

Global functions: The value proposition

By definition, investments in global functions produce benefits that transcend individual countries. Beyond this value proposition, there are at least five additional arguments for directing global collective financing to areas where both markets and governments have natural incentives to underinvest, namely in global functions.

1. The high cost of inaction

Taking inadequate action to support global functions—such as under-funding pandemic preparedness or AMR—could be associated with major economic losses. These losses are described elsewhere in this series such as in Yazbeck and Soucat’s article.Citation18 Two examples are the expected annual losses from pandemic risk (projected to be approximately 500 billion USD, or 0.6% of global income per yearCitation19) and the estimated annual GDP loss in 40 years that will accrue if current rates of AMR persist, approximately 454 billion USD per year.Citation20

2. The impressive health and economic returns to investing in certain global functions

The returns to investing in selected global functions are impressive, some of the largest in all of global development. Two examples are:

Product development. The returns to investing in the polio vaccine have been extraordinary. The vaccine was developed through a 26 million USD investment by the March of Dimes; in the US alone, since routine vaccination was introduced over 160,000 polio deaths and approximately 1.1 million cases of paralytic polio have been prevented. Treatment cost savings have generated a net benefit of around 180 billion USD.Citation21 The successful development of new breakthrough technologies, such as highly effective vaccines for HIV, TB, or malaria or complex new chemical entities for TB, is likely to be associated with similarly large returns on investment. Using a “full income” approach, which includes valuation of the changes in mortality risk, Hecht and colleagues explored the benefits of a preventive HIV vaccine under a range of scenarios about the evolution over time of an epidemic and control measures against it. Assuming a vaccine of 50% efficacy becomes available by 2030 and continued extremely high development expenditures of around 900 million USD per year, the value of benefits would exceed costs, in some cases substantially, under any scenario.Citation22

Market shaping. In Alma Ata at 40: Reflections from the Lancet Commission on Investing in Health, the CIH defined market shaping as “LICs, MICs, donors, and procurers using their purchasing power, financing, influence, and access to technical expertise to address the root causes of market shortcomings and influence markets for improved health outcomes.”Citation23 Such market shaping, a “classic” GPG, has been critical in expanding access to vaccines in LICs and MICs. For example, in 2001, one manufacturer was supplying the pentavalent DTP-HBV-Hib vaccine at Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance (Gavi) price of 3.50 USD per dose. Through market shaping efforts led by Gavi, by 2017 there were five suppliers and the lowest price offered was 0.68USD per dose.Citation23

3. Investments in global functions may benefit LICs and MICs more than direct funding of services

Over the long run, financing of global functions might be more beneficial to LICs and MICs than direct funding of services. One benefit of funding for GPGs and the management of negative externalities is that it is less likely to be fungible than direct support to countries. Studies have shown that finance ministries tend to respond to country-specific health ODA by reducing their own domestic public financing of health.Citation24 The concern about this phenomenon—called aid fungibility or substitution—is that ODA for health may not end up being additional to domestic health sector resources. Multiple studies have confirmed that health ODA is fungible,Citation25,Citation26 although a debate remains about the extent and consequences of this substitution.Citation27 One study by Lu and colleagues found that for every dollar that LICs and MICs receive in health ODA, they remove on average and over the short term 0.44 USD of their own domestic health spending.Citation28 Support for global functions, by being less fungible, may be a more efficient way for donor support to benefit poor individuals. Re-programming of within-country DAH can achieve the dual purposes of achieving transnational benefits and reducing or eliminating fungibility.

Using DAH to control drug-resistant TB (DR-TB) is an example of a global function of low fungibility with transnational benefits. An important consequence (and objective) of strengthening the quality of country-level TB programs is to prevent the emergence of DR-TB. As DR-TB, like other forms of AMR, plausibly spreads across borders, the benefits of country-financed control accrue to other countries. This can result in reasonable incentives at the national level to underspend. Thus using external funds to finance a globally reasonable level of national effort is relatively non-fungible, as it is unlikely to displace local funds that would not in any case have been spent. Another example with substantial practical importance is national spending on surveillance for zoonotic diseases such as pandemic influenza. By increasing the time that global and national authorities have to respond to the outbreak, early action can strongly attenuate the course of an epidemic. Here again, since many—perhaps even most—of the benefits of improved surveillance accrue to other countries, individual nations consistently, and reasonably, underspend. External support is therefore unlikely to displace domestic finance but instead adds to it, and therefore helps ensure that effective surveillance programs are in fact financed.

In contrast, support for strengthening capacity for clinical services (through financing a nursing school, say) or for the clinical services themselves has benefits that accrue almost entirely within a country. These investments are worth financing, but it makes sense for the national governments to pay for them except when countries are exceptionally poor. International finance for these investments is thus likely to be highly fungible, freeing up money to the Ministry of Finance for other purposes. The effect here can be substantial, as discussed above.

This rationale for using international finance to support control of negative cross-border externalities can hold for MICs as well as LICs.

4. Investments in global functions can help address the “middle-income dilemma”

Investments in global functions are a critically important strategy for addressing the so-called “middle-income dilemma” in global health. The dilemma refers to the fact that approximately 70% of the world’s poor people now live in MICs rather than LICs.Citation29 This segment of the population faces very high rates of poverty and avertable mortality—yet many of the MICs where they reside have reached or will soon reach a per capita income level that excludes them from receiving health ODA.Citation30 Increasing funding for global functions such as R&D for neglected diseases, knowledge generation and sharing, market shaping, and management of cross-border externalities could bring substantial benefits to the poor in MICs. For example, almost half of all cases of MDR-TB, a “disease associated with the poorest of the world,”Citation31 are in three MICs: China, India, and the Russian Federation. Disease-affected communities in these countries would “substantially benefit from collective purchasing of commodities, market shaping to reduce drug prices, and increased international efforts to control multidrug-resistant tuberculosis.”Citation10

One particular concern currently facing MICs is relatively low childhood vaccination coverage rates for new vaccines. This situation is partly explained by high vaccines prices for MICs that are too wealthy to qualify for support from Gavi. Gavi has estimated that by 2030, “almost 70% of the world’s under-immunized children will be living in countries ineligible for Gavi’s vaccination programs, such as Nigeria, India, and the Philippines.”Citation32 Global functions—especially market shaping and pooled procurement—will be critical in making pneumococcal conjugate, rotavirus, and human papillomavirus vaccines, among others, more affordable to MICs.

5. Graduation of MICs from health ODA provides an opportunity for aid reallocation

In the next few years, over a dozen MICs are predicted to transition out of eligibility for ODA for health, particularly from multilateral concessional assistance such as Gavi and the World Bank’s International Development Association, which supports the world’s poorest countries.Citation33 The Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) estimates that by 2030, only 14 developing countries will be eligible for concessional programs of the multilateral development banks.Citation34 Annual health ODA has been stagnant, at approximately 21 billion USD/year since 2013 (excluding private flows, other than funding from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation). Assuming this level remains static, these upcoming transitions provide an opportunity to re-allocate health ODA to global functions.

How Much is the World Spending on Global Functions?

The economic losses associated with inaction on global functions are substantial. It is instructive to compare these losses with the levels of spending on global functions. In a study commissioned by the WHO for this series on financing global CGH, Schäferhoff and colleagues used the taxonomy shown in to analyze ODA for health in 2013, 2015, and 2017 (the latest year for which data are available).Citation3 They found that the proportion of total ODA directed at global functions was only 23% in 2013, rising to 29% in 2015, and then falling again to 24% in 2017 (). In absolute terms, this means that international funding for global functions increased between 2013 and 2015 by 1.35 billion USD, bringing funding for global functions to a total of 7.3 billion USD in 2015, and then fell by 300 million USD to 7.0 billion USD in 2017. The increase in international financing for global functions in 2015 was mostly driven by the international response to the 2014–2016 West Africa Ebola epidemic ().

The Price Tag for Global Functions

Given the enormous potential losses associated with inaction mentioned above, the total spending of 7 billion USD per year in 2017 on global functions is likely to be insufficient, especially given some of the threats associated with environmental degradation. What is a reasonable estimate for how much the global health community should be spending on global functions?

In its recent Alma Ata at 40 paper, the CIH developed an initial estimate that an additional 9.5 billion USD is needed annually. This estimate was made with many admitted data gaps, suggesting a highly conservative estimate.Citation23 Further, the estimate excluded financing needs for malaria eradication, which were estimated by the Lancet Commission on Malaria Eradication to be an additional 2 billion USD annually.Citation35 The components of the 9.5 billion USD estimate are:

Product development for neglected diseases. The CIH estimates that an additional 3 billion USD per year is needed for neglected diseases, which should focus particularly on the development of complex new chemical entities (NCEs) for TB and highly effective vaccines for HIV, TB, and malaria. This estimate is informed by a recent study by Young and colleaguesCitation36 that examined the current pipeline of candidate products for neglected diseases using a financial modeling tool, the Portfolio-to-Impact (P2I) tool.Citation37 The study estimated the costs to move these candidates through the pipeline, the likely launches by 2030, and the needed products likely to still be “missing” by 2030 (, ).

Pandemic preparedness. The Commission on a Global Health Risk Framework, chaired by Peter Sands, the current executive director of the Global Fund, estimated that an additional 3.4 billion USD per year is needed to support preparedness for emerging infectious disease outbreaks, including to upgrade health systems.Citation38 The CIH argued that this figure could be “a serious underestimate if pandemic preparedness were to require a substantial amount of new and dispersed investments in vaccine manufacturing capacity.”Citation23

Polio eradication. The continuing activities of the Global Polio Eradication Initiative are estimated to cost approximately 1 billion USD annually.Citation39

Funding the WHO’s core activities (further explained later in this article). WHO estimates that it needs at least an additional 1.2 billion USD over the next five years (i.e., an additional 240 million USD annually) to fund its 13th general program of work (2019–2023).Citation40,Citation41

Pooled procurement for non-communicable diseases. The CIH estimates that an additional 1.2 billion USD is needed annually for “a pooled procurement mechanism for [non-communicable diseases] to expand the model tested by PAHO [the Pan American Health Organization] to other regions.”Citation23

Population, policy, and implementation research (PPIR). Finally, the CIH estimates that an additional 600 million USD is needed for PPIR and other knowledge generation and distribution activities.Citation23

BOX 1. Estimating the Finance Gap for Product Development for Neglected Diseases

TABLE 3. Important or Game Changing Products Proposed by the Commission on Investing in Health that Could Help Achieve a Grand Convergence in Global Health by 2035. Source: CitationRef. 1.

Financing and Governing Global Functions

In the previous section, we argued that at least an additional 9.5 billion USD is needed annually to support global CGH, noting that this is a conservative estimate (it rises to 11.5 billion USD annually if the costs of malaria eradication are added).Citation35 How can this amount be financed? What global-level revenue mechanisms can be established? What kinds of governance arrangements would support resource pooling and strategic purchasing of GPGs? This section briefly addresses these questions, by examining some existing financing approaches to global functions and proposing new approaches. We have organized these approaches into the three broad categories of health financing functionsCitation42:

Resource mobilization mechanisms including global taxes, new stand-alone mechanisms, and reallocation of ODA

Pooling approaches, including multilateral agencies, pooled R&D funds, and coordination platforms

Strategic purchasing of GPGs.

Mobilizing Revenue at the Global Level

Global Taxation

The levying of taxes aims either to raise revenue to fund government or to alter prices in order to affect demand. In an increasingly globalized world, calls for mechanisms of global taxation are a direct response to the need for global action and funding of GPGs. Examples abound, such as a tax on currency trading that could dampen dangerous instability in the foreign exchange markets.Citation43 Recently a bipartisan group of 45 prominent US economists, including 27 Nobel Prize recipients and a former Federal Reserve Chairman, joined by several hundred others, called for a global carbon tax to incentivize the reduction of carbon emissions.Citation44 A strong case for such a tax exists as, absent market interventions, fossil fuels are likely to continue to be burned for many years.Citation45 Taxation of airline tickets is an-already existing example of multi-country taxation aiming at raising revenue. The international solidarity levy on airline tickets brings together the revenue of 15 countries to fund communicable diseases programs, mostly for HIV.Citation46 A new French “eco-tax” on all flights out of French airports starting in 2020 is expected to raise approximately 200 million USD annually to fund “green” transportation options.Citation47 For several years, the European countries’ tax administrations have also been exploring how to tax the financial sector across countries, for example by introducing bank levies and national financial transaction taxes. More recently, they have proposed a tax on jet fuel.Citation48,Citation49 These examples all point to growing political interest in, and support for, using global or cross-country taxation as a lever for mobilizing funds for public goods.

As a general principle, public goods require compulsory collective financing (see previous articles in this series by Gaudin and colleaguesCitation8 and Sparkes and colleagues.Citation50) Just as voluntary insurance cannot lead to universal health coverage, voluntary contributions are not well-fitted to financing GPGs. Yet voluntary funding represents the bulk of funding for the UN, which is the closest we have to a global government.

One could argue that global goods call for global government. As we live in an increasingly globalized world and have to collectively tackle “big” problems—such as the future of the human species—some global stream of compulsory financing increasingly appears necessary. GPGs for health should be financed by contributions from all governments regardless of income level—ideally through a global compulsory mechanism such as levying a global tax.

Voluntary Earmarked Resource Mobilization Mechanisms

In recent years, a number of stand-alone voluntary financing mechanisms have been launched to raise funding for specific global functions. Gavi, for example, has played a critical role in market shaping. In 2017, CEPI, a Norwegian public-private partnership, was launched at the World Economic Forum to raise money to develop new vaccines for emerging infections with epidemic potential.Citation51 CEPI mobilized 540 million USD at its launch from the governments of Germany, Japan, and Norway, plus the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and the Wellcome Trust.Citation52 Since then, additional contributions have come from multiple sources, including Australia, Belgium, Canada, the European Commission, Japan, Germany, and the UK.Citation53 CEPI has shown the value of targeted advocacy for a single function, such as product development, and this type of approach could be replicated for other under-funded global functions. The year 2017 also saw the launch of the PEF, which aims to provide countries with rapid surge financing to respond to outbreaks from specific viruses with pandemic potential.Citation54 The PEF’s cash window, funded by donors, has distributed funding to affected countries. However, its insurance window—funded through the sale of pandemic bonds—has come under criticism for the narrow criteria that must be met for a country to receive funds, which could benefit investors more than affected countries.Citation55

Two other examples of stand-alone resource mobilization mechanisms for global functions include the Global Health Innovative Technology Fund, which had mobilized 345 million USD for neglected disease product development by 2018, and the Combating Antibiotic Resistant Bacteria Biopharmaceutical Accelerator, which mobilized 500 million USD for the period 2016–2021 to advance early stages of product development to tackle AMR.Citation56

However, the proliferation of such single-function finance mechanisms creates a risk: they could end up creating a fragmented funding environment in which different initiatives compete for attention and funds from the same donors. Such competition is currently threatening the multiple replenishments facing multilateral health financiers. An overarching, coordinated approach to governance would still be needed—for example, for priority setting and to determine which functions have the greatest needs (see the section below: The role of the WHO as an overarching governance mechanism).

Reallocation of ODA

In the coming years, several MICs will transition out of receiving ODA for health, providing important opportunities to “reallocate ODA to areas where governments have natural incentives to underinvest,”Citation23 namely, to global functions. In addition to reallocating country-specific ODA to global functions, another approach to increasing funding for global functions would be reprogramming of existing in-country DAH—for example, from training workshops or project management towards pandemic preparedness—within existing budget envelopes. This would involve gradually changing the types of activities that donors support (rather than which countries are being supported) to create a global revenue stream for global goods. The creation of such a global revenue stream will not, of course, happen automatically. It would require a combination of political will, leadership, public engagement, and other factors, as part of a concerted global “movement” that would have parallels with the climate change movement.

Pooling Approaches

Pooled R&D Funds

For many global functions, such as product development for neglected diseases, existing mechanisms to overcome market failures—such as product development public-private partnerships—have, say Røttingen and Chamas, “only treated the symptoms exhibited by the system failures and not the root causes.”Citation57 The authors, who chaired the WHO Consultative Expert Working Group on Research and Development: Financing and Coordination, proposed a more radical and “transformative” approach in which all nations would contribute to a pooled fund according to their ability to pay, a global structure akin to social insurance at the national level.

R&D investments to develop products for diseases of poverty, Røttingen and Chamas argued, should be “treated like the global public goods they are such that all countries—rich and poor, developed and developing alike—contribute according to the size of their economy.” They recommended that all countries should allocate “at least 0.01% of GDP to this global public good, which would result in a doubling of current investments.” While this proposal for a pooled R&D fund has not yet gained political traction, advocates for increased funding for GPGs continue to promote the principle that all countries should make contributions. The two essential features for such a mechanism to be truly global would be compulsoriness and allowing for cross-subsidization of the poorest contributors.

One recent proposal put forward by the Center for Global Development suggests using pooled financing to incentivize the development of urgently-needed new TB technologies. The proposed pooled fund for new TB products, called the “Market-Driven, Value-Based Advance Commitment” (MVAC), would be financed by MICs, especially those that have a high burden of TB.Citation58 In the MVAC, MICs would make pooled commitments to purchase new TB technologies, providing guarantees of a market to pharmaceutical companies for newly developed products.

Coordination Platforms

New coordination platforms for overarching governance of global CGH are gaining momentum as vehicles for both mobilizing new resources and targeting financing to the highest priority needs. To date, these platforms have been small, operating with little funding and few staff. For global health R&D, examples include the WHO Global Health Observatory on R&D, which aims to identify overarching R&D priorities, and the new Global Antimicrobial Resistance Research and Development Hub, which aims to “further improve the coordination of international efforts and initiatives to tackle AMR while further increasing investments into R&D for AMR.”Citation59

A new policy analysis entitled “Improving resource mobilization for global health R&D: a role for coordination platforms?” argues that while these small-scale efforts are promising, “there is still no overarching, inclusive platform that systematically collects all the required information to properly coordinate global health R&D investments and activities.”Citation56 Such an overarching platform, the authors said, should play four key functions: (i) building consensus on R&D priorities; (ii) facilitating information sharing about past and future investments (including providing information on what is currently in the pipeline, costs to move candidates through the pipeline, and likely resulting launches); (iii) building in accountability mechanisms to track R&D spending against investment targets; and (iv) curating a portfolio of prioritized projects alongside mechanisms to link funders to these projects. WHO would be the institution best suited to carry out these and other normative global functions, but faces a funding shortfall for such activities. The CIH argued that this shortfall is undermining WHO’s “capacity to supply global public goods and other global functions, including the management of negative externalities” and that “a top priority for international collective action for health is to ensure that WHO and other UN agencies have access to funding that enables them to fully realize their unique role.”Citation23

Multilateral Agencies

One way the global community already pools funding is through multilateral agencies whose clear regional or global mandates make them well placed to help address the price tag for global functions. A recent policy analysis that examined the role of intensified multilateral cooperation on GPGs for health argued that “in the current climate of growing worldwide nationalism and populism, the multilateral institutions now find themselves well positioned to become a countervailing force in taking international collective action and supporting GPGs for health.”Citation60

The analysis notes that all the major multilateral health funders have signaled that they intend to step up their activities in support of global functions. For example, GPGs for health is one of three strategic shifts in the WHO’s latest Global Programme of Work,Citation61 while the World Bank’s shareholders recently designated 100 million USD in income or profit from lending to support GPGs.Citation62

The analysis was based in part on key informant interviews with senior leadership at Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance, the Global Fund, the World Bank, and WHO. It identified a shared window of opportunity across the four agencies to increase their support for three global functions: (i) improved production and sharing of health data; (ii) improved development of and access to health technologies; and (iii) pandemic preparedness.

The new Global Action Plan for Healthy Lives and Wellbeing for All, which is supported by twelve of the largest multilateral health funders, also calls for intensified multilateral cooperation in achieving SDG3.Citation63 The Plan’s three pillars are to align activities, accelerate progress, and improve accountability for results, and global functions are at its heart. For example, the Plan calls for its twelve funders to step up their support for global health “R&D, innovation, and access” and “disease outbreak response.”

Strategic Purchasing for Global Public Goods

Several global health agencies have progressively developed a “strategic purchasing” function through the development of prioritization models to allocate their funding. GAVI, for example, allocates approximately 20% of its funding to support global functions, including pooled procurement and market shaping.Citation1 The Global Fund’s 2017–2022 strategy includes 194 million USD for “Strategic Initiatives,” a designation that refers to investments that cannot be delivered through country grants. These include malaria elimination and pilot studies of malaria vaccine introduction.Citation64 IDA also funds regional public goods, such as the East Africa Public Health Laboratory Network.Citation65

The Role of WHO as an Overarching Governance Mechanism

Above we laid out a number of different approaches to develop a sustainable financing architecture for global functions. Each of these options holds promise, but the most critical step would be a radical shift in how WHO itself is financed. As discussed below, a paradox is at the heart of the governance of global functions: while WHO is the best-placed body to drive forward the “global functions agenda,” it has become increasingly starved of the collective resources it needs to fulfill this role. WHO’s director general, Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, has described the challenges created by this paradox: “If we continue to operate under the same funding restrictions, we will produce the same results. No organization can succeed when its budget and priorities are not aligned.”Citation66

The director of the Harvard Global Health Institute, Ashish Jha, further argues: “While it is true that there are now hundreds of organizations engaged in global health, there is none with the legitimacy of the WHO.”Citation67 The six core functions of WHO () reflect its position as the overarching global health governance body, akin to a global ministry of health or government.

BOX 2. The WHO’s Six Core Functions as Described in Its Thirteenth General Programme of Work 2019–2023Citation56

GPGs for health are a foundation of WHO’s 2019–2023 General Programme of Work.Citation61 In particular, WHO aims to strengthen the production of three categories of GPGs for health: (i) constitutional normative products (regulations and conventions, approved by the World Health Assembly (WHA) or an equivalent body, such as the Codex Alimentarius Commission); (ii) scientific and technical normative products (e.g., treatment guidelines); and (iii) health trend assessments (e.g., on the global burden of disease or supporting national health accounts). The 2019–2023 work program calls for a scaled-up effort on one particular key GPG for health, knowledge generation and sharing.

Yet the way in which WHO is financed impedes its ability to fully support its global functions. WHO’s Program Budgets are approved for two-year periods—the current 2018–2019 budget was approved at the May 2017 WHA, and the 2020–2021 budget was proposed at the May 2019 WHA. The budget is financed through a combination of “assessed contributions,” or regular budget funds, which are the dues that countries pay to be members of the WHO (scaled by population and income), and “voluntary contributions,” which are extra-budgetary funds provided by a relatively small number of donors. Over the last two decades, while WHO’s overall budget has risen, the distribution between these two types of contributions has undergone a dramatic change. Voluntary contributions made up 40% of the 1994–1995 budget, but they have increased steadily. In the 2018–2019 budget voluntary contributions comprised almost 80% of all funding (76% in 2017 and 77% in 2018).Citation68

Voluntary donor contributions are heavily earmarked—that is, the donors specify what activities the funds should go to (e.g., to polio eradication or maternal health programing). Thus the funds do not fully align with WHO’s core functions or program budget. , which summarizes the WHO’s financing over the last three biennia, shows the magnitude of this earmarking. For example, in 2018–2019, earmarked voluntary contributions (called “voluntary contributions specified”) comprised approximately 4 billion USD, compared with around 1.4 billion USD in flexible funds. Of these flexible funds, only about 119 million USD was in the form of “core voluntary contributions” (non-earmarked voluntary contributions that can be used flexibly). The CIH argues that, as a result of earmarking by donors, WHO is “struggling to fund its core functions, undermining its capacity to supply global public goods and other global functions, including the management of negative externalities.”Citation23

TABLE 4. WHO’s Sources of Financing (US Dollars). *derived from Charges against Voluntary Contributions. **approved for Current and past Bienna

A recent analysis by Clift and Røttingen found that several countries—including France, Italy, Spain, and many MICs—are not currently contributing their “fair share” (based on gross national income, GNI) to support WHO.Citation69 Ensuring sustainable and flexible funding for WHO would be the most robust way to ensure that the organization can carry out a critical set of global functions. One way to ensure such funding would be through a compulsory global taxation mechanism.

In the interim, a politically feasible approach that could help generate additional funding to support WHO to fulfil its role in supplying global CGH is mobilization of additional un-earmarked voluntary contributions (from country governments and other funders). For example, Clift and Røttingen estimate that if upper MICs and high-income countries could be persuaded to give voluntary contributions more in line with their GNI, an additional 280–470 million USD annually could be mobilized. The authors suggest that countries are more likely to be motivated to raise their contributions if they were directed towards one of WHO’s six core functions (e.g., setting norms and standards, and promoting and monitoring their implementation). Rather than negotiating with individual donors, say Clift and Røttingen, “a collective approach to funding programs, which can also use peer pressure, seems more likely to be successful.”Citation69

Conclusions and Reflections on the Future of Global Functions

We have made the case that global functions—GPGs, management of negative externalities, and fostering leadership and stewardship—are critical in achieving multiple global health goals. The global community has under-invested in these global functions, particularly in relation to the likely economic losses associated with under-investment. Such investments, we have shown, can be made at the global, regional, or country level. There is a strong case for investing in global functions: the health and economic returns are impressive, these investments may be less fungible than direct country support, and they are an important way to address the “middle-income dilemma.”

Over the long term, we believe some form of taxation would be the most robust solution to the global under-investment in global functions. A universal carbon tax, for example, would curb the use of fossil fuels and thus the associated consequences on health. Regional or global taxes on financial transactions or airlines tickets are increasingly a reality and have the potential to significantly increase funding for GPGs. A global political movement would be needed to build support for such taxes.

In a more immediate time frame, a recent policy analysis showed that several opportunities for greater pooling and strategic purchasing exist.Citation60 In addition, over the next few years, over a dozen MICs will transition away from receiving direct country support from multilateral agencies (such as Gavi and IDA).Citation30 Their transitions provide an opportunity to reallocate health ODA to global functions. Lawrence Summers, former US Treasury Secretary, in a keynote address at the World Innovation Summit for Health on “the future of aid for health,” suggested that, assuming the total annual level of ODA for health remains stagnant, by 2030 approximately 50% of such ODA should be directed at global functions.Citation70 This suggestion aligns with the recent CIH estimate that at least an additional 9.5 billion USD is needed annually for global functions.Citation23 shows the CIH’s ranking of priority investments.

TABLE 5. The Highest Priority Global Functions Requiring Investment, as Ranked by the CIH

Country-specific aid will, of course, still be needed for many decades—especially for the countries with greatest needs, including fragile and post-conflict nations. And reallocation will need to be carefully managed given the vulnerabilities facing the cohort of countries that are nearing graduation from country-specific ODA.Citation30 However, greater investments in global functions are likely to reap major rewards for the health of the world’s poor.Citation23

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Jamison DT, Summers LH, Alleyne G, Arrow KJ, Berkley S, Binagwaho A, Bustreo F, Evans D, Feachem RG, Frenk J, et al. Global health 2035: a world converging within a generation. Lancet. 2013;382:1898–955. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62105-4.

- Birdsall N, Diofasi A. Global public goods for development: how much and what for. Washington (DC): Center for Global Development; 2015 May 18 [accessed 2019 Aug 2]. https://www.cgdev.org/publication/global-public-goods-development-how-much-and-what.

- Schäferhoff M, Chodavadia P, Martinez S, Kennedy McDade K, Fewer S, Silva S, Jamison DT, Yamey G. International funding for global common goods for health: an analysis using the creditor reporting system and G-FINDER databases. Health Syst Ref. 2019;5(4):350-365.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2014–2016 Ebola outbreak in West Africa. Atlanta (GA): Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2019 Mar 8. [accessed 2019 Aug 2]. https://www.cdc.gov/vhf/ebola/history/2014-2016-outbreak/index.html.

- World Health Organization. Factors that contributed to undetected spread of the Ebola virus and impeded rapid containment. Geneva (Switzerland): World Health Organization; 2015 Jan [accessed 2019 Aug 2]. https://www.who.int/csr/disease/ebola/one-year-report/factors/en/.

- World Health Organization Ebola Interim Assessment Panel. Report of the Ebola interim assessment panel. Geneva (Switzerland): World Health Organization; 2015 July [accessed 2019 Aug 2]. http://www.who.int/csr/resources/publications/ebola/ebola-panel-report/en/.

- Nordhaus WD. Paul Samuelson and global public goods; 2005 May 5 [accessed 2019 Aug 2]. http://www.econ.yale.edu/~nordhaus/homepage/homepage/PASandGPG.pdf.

- Gaudin S, Smith P, Soucat A, Yazbeck AS. Common goods for health: economic rationale and tools for prioritization. Health Syst Reform. 2019;5(4): 280-292.

- Bump JB, Krishnamurthy Reddiar S, Soucat A. When do governments support common goods for health? Four cases on surveillance, traffic congestion, road safety, and air pollution. Health Syst Reform. 2019;5(4): 293-306.

- Schäferhoff M, Fewer S, Kraus J, Richter E, Summers LH, Sundewall J, Yamey G, Jamison DT. How much donor financing for health is channeled to global versus country-specific aid functions? Lancet. 2015;386:2436–41. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(15)61161-8.

- World Health Organization, World Intellectual Property Organization, World Trade Organization. Chapter 3—Medical technologies: the innovation dimension. In: WHO, WIPO, WTO, editors. Promoting access to medical technologies and innovation: intersections between public health, intellectual property and trade. Geneva (Switzerland): WHO, WIPO, WTO; 2012. p. 100–141. [accessed 2019 Aug 2]. https://www.wto.org/english/tratop_e/trips_e/trilatweb_e/ch3c_trilat_web_13_e.htm.

- Yen C, Hyde TB, Costa AJ, Fernandez K, Tam JS, Hugonnet S, Huvos AM, Duclos P, Dietz VJ, Burkholder BT. The development of global vaccine stockpiles. Lancet Inf Dis. 2015;15:340–47. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(14)70999-5.

- Wong G, Qiu X. Funding vaccines for emerging infectious diseases. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2018;14:1760–62. doi:10.1080/21645515.2017.1412024.

- World Bank. Pandemic emergency financing facility. Washington (DC): World Bank; 2019 May 7. [accessed 2019 Aug 2]. http://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/pandemics/brief/pandemic-emergency-financing-facility.

- African Academy of Sciences. Coalition for African research and innovation (CARI). Nairobi (Kenya): Alliance for Accelerating Excellence of Science in Africa; 2017. [accessed 2019 Aug 2]. https://aesa.ac.ke/cari/coalition-for-african-research-and-innovation/.

- African Union. Africa CDC. Addis Ababa (Ethiopia): African Union; [accessed 2019 Aug 2]. https://au.int/en/africacdc.

- Lover AA, Harvard KE, Lindawson AE, Smith Gueye C, Shretta R, Gosling R, Feachem R. Regional initiatives for malaria elimination: building and maintaining partnerships. PLoS Med. 2017;14:e1002401. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1002230.

- Yazbeck AS, Soucat A. When both markets and governments fail health. Health Syst Reform. 2019;5(4): 268-279.

- Fan VY, Jamison DT, Summers LH. Pandemic risk: how large are the expected losses? Bull World Health Organ. 2018;96:129–34. doi:10.2471/BLT.17.199588.

- Naylor NR, Atun R, Zhu N, Kulasabanathan K, Silva S, Chatterjee A, Knight GM, Robotham JV. Estimating the burden of antimicrobial resistance: a systematic literature review. Antimicrob Resis Infect Control. 2018;7:58. doi:10.1186/s13756-018-0336-y.

- Thompson KM, Tebbens RJ. Retrospective cost-effectiveness analyses for polio vaccination in the United States. Risk Anal. 2006 Dec;26(6):1423–40. doi:10.1111/j.1539-6924.2006.00831.x.

- Hecht R, Jamison DT, Augenstein J, Partridge G, Thorien K. RethinkHIV assessment paper: vaccine research and development. Copenhagen (Denmark): Copenhagen Consensus Center; 2011 [accessed 2019 Aug 2].

- Watkins DA, Yamey G, Schäferhoff M, Adeyi O, Alleyne G, Alwan A, Berkley S, Feachem R, Frenk J, Ghosh G, et al. Alma-Ata at 40 years: reflections from the Lancet commission on investing in health. Lancet. 2018;392:1434–60. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32389-4.

- Xu K, Soucat A, Kutzin J, Brindley C, Dale E, Van de Maele N, Roubal T, Indikadahena C, Toure H, Cherilova V. New perspectives on global health spending for Universal health coverage. Geneva (Switzerland): WHO; 2017 [accessed 2019 Aug 14]. https://www.who.int/health_financing/topics/resource-tracking/new-perspectives/en/.

- Dykstra S, Glassman A, Kenny C, Sandefur J. Regression discontinuity analysis of Gavi’s impact on vaccination rates. J Dev Econ. 2019;140:12–25. doi:10.1016/j.jdeveco.2019.04.005.

- Álvarez MM, Borghi J, Acharya A, Vassall A. Is development assistance for health fungible? Findings from a mixed methods case study in Tanzania. Soc Sci Med. 2016;159:161–69. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2016.05.006.

- Roodman D. The health aid fungibility debate: don’t believe either side. Washington (DC): Center for Global Development; 2012 May 14 [accessed 2019 Aug 2]. https://www.cgdev.org/blog/health-aid-fungibility-debate-dont-believe-either-side.

- Lu C, Schneider MT, Gubbins P, Leach-Kemon K, Jamison D, Murray CJ. Public financing of health in developing countries: a cross-national systematic analysis. Lancet. 2010;375:1375–87. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60233-4.

- Sumner A. The new bottom billion: what if most of the world’s poor live in middle-income countries? Washington (DC): Center for Global Development; 2011.

- Yamey G, Gonzalez D, Bharali I, Flanagan K, Hecht R. Center for policy impact in global health working paper. Durham (NC): Center for Policy Impact; 2018 [accessed 2019 Aug 2]. http://centerforpolicyimpact.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/18/2018/03/Transition-from-foreign-aid_DukeCPIGH-Working-Paper-final.pdf.

- Poverty’s child and MDR-TB: multi-drug resistant tuberculosis. Borgen Mag; 2014 Feb 28. [accessed 2019 Aug 2]. https://www.borgenmagazine.com/povertys-child-mdr-tb-multidrug-resistant-tuberculosis/.

- Berkley S Vaccination lags behind in middle-income countries. Nature; 2019 May 14 [accessed 2019 Aug 2]. https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-019-01494-y.

- Yamey G, Hecht R. Are tough times ahead for countries graduating from foreign aid? Future Dev. 2018 March 8 [accessed 2019 Aug 2]. https://www.brookings.edu/blog/future-development/2018/03/08/are-tough-times-ahead-for-countries-graduating-from-foreign-aid/.

- Sedemund J. An outlook on ODA graduation in the post-2015 era. External Financing for Development, Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development; 2014 Jan [accessed 2019 Aug 20]. https://www.oecd.org/dac/financing-sustainable-development/ODA-graduation.pdf.

- Feachem RGA, Chen I, Akbari O, Bertozzi-Villa A, Bhatt S, Binka F, Boni M, Buckee C, Dieleman J, Dondorp A, et al. Lancet commission on malaria eradication: malaria eradication within a generation: ambitious, achievable and necessary. Lancet. 2019. forthcoming. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(19)31139-0.

- Young R, Bekele T, Gunn A, Chapman N, Chowdhary V, Corrigan K, Dahora L, Martinez S, Permar S, Persson J, et al. Developing new health technologies for neglected diseases: a pipeline portfolio review and cost model. Gates Open Res. 2018;2:23. doi:10.12688/gatesopenres.12817.1.

- Terry RF, Yamey G, Miyazaki-Krause R, Gunn A, Reeder JC. Funding global health product R&D: the portfolio-to-impact model (P2I), a new tool for modelling the impact of different research portfolios. Gates Open Res. 2018;2:24. doi:10.12688/gatesopenres.12816.2.

- Sands P, Mundaca-Shah C, Dzau VJ. The neglected dimension of global security—a framework for countering infectious-disease crises. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:1281–87. doi:10.1056/NEJMsr1600236.

- Global Polio Eradication Initiative. Financial resource requirements: GPEI budget 2018. Geneva (Switzerland): GPEI; 2018 Oct 15. [accessed 2019 Aug 2]. http://polioeradication.org/financing/financial-needs/financial-resource-requirements-frr/gpei-budget-2018/.

- World Health Organization. White paper: financial estimate for the 13th general programme of work (2019–2023). Geneva (Switzerland): World Health Organization; 2018.

- World Health Organization. A healthier humanity: the WHO investment case for 2019–2023. Geneva (Switzerland): World Health Organization; 2018.

- Kutzin J. A descriptive framework for country-level analysis of health care financing arrangements. Health Pol. 2001;6(3):171–204. doi:10.1016/S0168-8510(00)00149-4.

- Global Policy Forum. Global taxes. New York (NY): Global Policy Forum; 2019. [accessed 2019 Aug 2]. https://www.globalpolicy.org/global-taxes.html.

- Akerlof G, Aumann R, Deaton A, Diamond P, Engle R, Fama E, Hansen LP, Hart O, Holmström B, Kahneman D, et al. Economists statement on carbon dividends. Bipartisan agreement on how to combat climate change. Wall Street J. 2019 Jan 16. [accessed 2019 Aug 2]. https://www.wsj.com/articles/economists-statement-on-carbon-dividends-11547682910.

- Covert T, Greenstone M, Knittel CR. Will we ever stop using fossil fuels? J Econ Perspect. 2016;30(1):117–38. [accessed 2019 Aug 2]. https://pubs.aeaweb.org/doi/pdf/10.1257/jep.30.1.117.

- Unitaid. Unitaid annual report 2016–2017. Geneva (Switzerland): Unitaid; 2017. [accessed 2019 Aug 2]. https://unitaid.org/unitaid-ar-1617/.

- Associated Press. France to slap new ‘ecotax’ on plane tickets from 2020. U.S. news & world report; 2019 July 9 [accessed 2019 Aug 2]. https://www.usnews.com/news/business/articles/2019-07-09/france-will-implement-an-ecotax-on-plane-tickets-from-2020.

- European Commission. The history of the proposal financial transaction tax. Brussels (Belgium): Commission’s Taxation and Customs Union Directorate General; [accessed 2019 Aug 2]. https://ec.europa.eu/taxation_customs/sites/taxation/files/history-proposal-financial-transaction-tax_en.pdf.

- Leaked EU report boosts case for jet fuel tax. Financial times. 2019 May 12 [accessed 2019 Aug 2]. https://www.ft.com/content/1ce24798-733b-11e9-bbfb-5c68069fbd15.

- Sparkes SP, Kutzin J, Earle AJ. Financing common goods for health: a country agenda. Health Syst Reform. 2019;5(4): 322-333.

- Sabin Vaccine Institute. CEPI: a new approach to epidemic preparedness. Washington (DC): Sabin Vaccine Institute; 2017 June 16. [accessed 2019 Aug 2]. https://www.sabin.org/updates/blog/cepi-new-approach-epidemic-preparedness.

- Global Research Collaboration for Infectious Disease Preparedness (GLoPID-R). Some GLoPID-R members participated in the creation and official launch of the coalition for epidemic preparedness (CEPI) – a new beginning for funding vaccine development. Lyon (France): Fondation Merieux; [accessed 2019 Aug 2]. https://www.glopid-r.org/some-glopid-r-members-participated-in-the-creation-and-the-official-launch-of-the-coalition-for-epidemic-preparedness-innovations-cepi-a-new-beginning-for-funding-vaccine-development/.

- CEPI. UK pledges £10 million to support CEPI. Oslo (Norway): CEPI; 2019 Jan 22. [accessed 2019 Aug 2]. https://cepi.net/news_cepi/uk-pledges-10-million-to-support-cepi/.

- World Bank. World Bank launches first-ever pandemic bonds to support $500 million pandemic emergency financing facility. Washington (DC): World Bank; 2017 June 28. [accessed 2019 Aug 2]. http://treasury.worldbank.org/cmd/htm/World-Bank-Launches-First-Ever-Pandemic-Bondsto-Support-500-Million-Pandemic-Emergenc.html.

- Stein F, Sridhar D. Health as a “global public good”: creating a market for pandemic risk. BMJ. 2017;358:j3397.

- Beyeler N, Fewer S, Yotebieng M, Yamey G. Improving resource mobilisation for global health: a role for coordination platforms? BMJ Glob Health. 2019;4(1):e001209. doi:10.1136/bmjgh-2018-001209.

- Røttingen J-A, Chamas C. A new deal for global health R&D? The recommendations of the consultative expert working group on research and development (CEWG). PLoS Med. 2012;9(5):e1001219. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1001219.

- Silverman R. The world needs better drugs for TB. We have a proposal—and we need your feedback. Washington (DC): Center for Global Development; 2019 Mar 5 [accessed 2019 Aug 2]. https://www.cgdev.org/blog/world-needs-better-drugs-tb-we-have-proposal-and-we-need-your-feedback.

- German Federal Ministry of Education and Research. Global AMR R&D hub. Berlin (Germany): Federal Ministry of Education and Research; [accessed 2019 Aug 2]. https://www.gesundheitsforschung-bmbf.de/en/GlobalAMRHub.php.

- Center for Policy Impact in Global Health. Intensified multilateral cooperation on global public goods for health: three opportunities for collective action. Durham (NC): Center for Policy Impact; 2018 Nov [accessed 2019 Aug 2]. http://centerforpolicyimpact.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/18/2018/11/Multilaterals-and-GPGs_LONG_Final.pdf.

- World Health Organization. Thirteenth general programme of work 2019–2023. Geneva (Switzerland): WHO; 2018 May 16. [accessed 2019 Aug 2]. https://www.who.int/about/what-we-do/thirteenth-general-programme-of-work-2019-2023.

- Birdsall N. On global public goods: it’s not big money but it’s a big breakthrough. Washington (DC): Center for Global Development; 2018 May 2 [accessed 2019 Aug 2]. https://www.cgdev.org/blog/global-public-goods-not-big-money-but-breakthrough.

- World Health Organization. Global action plan for healthy lives and well-being for all. Geneva (Switzerland): WHO; 2019. [accessed 2019 Aug 2]. https://www.who.int/sdg/global-action-plan.

- The Global Fund. Funding model–catalytic investments. Geneva (Switzerland): The Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria; 2019. [accessed 2019 Aug 2]. https://www.theglobalfund.org/en/funding-model/before-applying/catalytic-investments/.

- AFR RI East Africa public health laboratory networking project. World Bank; 2019 [accessed 2019 Aug 23]. http://projects.worldbank.org/P111556/east-africa-public-health-laboratory-networking-project?lang=en&tab=overview.

- World Health Organization. Dialogue with the director-general executive board, 142nd session, agenda item 2. Geneva (Switzerland): WHO; 2018 Jan 22. [accessed 2019 Aug 2]. http://apps.who.int/gb/ebwha/pdf_files/EB142/B142_2-en.pdf.

- Jha AK. A race to restore confidence in the World Health Organization. Health affairs blog. Bethesda (MD): Project HOPE; 2017 April 6 [accessed 2019 Aug 2]. https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hblog20170406.059519/full/.

- World Health Organization. Programme budget 2018–2019. Geneva (Switzerland): WHO; 2017.

- Clift C, Røttingen J-A. New approaches to WHO financing: the key to better health. BMJ. 2018;361:k2218. doi:10.1136/bmj.k2218.

- Summers L. The future of aid for health. Presented at: the World Innovation Summit for Health; 2016 Nov 30; Doha, Qatar. [accessed 2019 Aug 2]. http://larrysummers.com/2016/11/30/the-future-of-aid-for-health/.