Abstract

Safeguarding the continued existence of humanity requires building societies that cause minimal disruptions of the essential planetary systems that support life. While major successes have been achieved in improving health in recent decades, threats from the environment may undermine these gains, particularly among vulnerable populations and communities. In this article, we review the rationale for governments to invest in environmental Common Goods for Health (CGH) and identify functions that qualify as such, including interventions to improve air quality, develop sustainable food systems, preserve biodiversity, reduce greenhouse gas emissions, and encourage carbon sinks. Exploratory empirical analyses reveal that public spending on environmental goods does not crowd out public spending on health. Additionally, we find that improved governance is associated with better performance in environmental health outcomes, while the degrees of people’s participation in the political system together with voice and accountability are positively associated with performance in ambient air quality and biodiversity/habitat. We provide a list of functions that should be prioritized by governments across different sectors, and present preliminary costing of environmental CGH. As shown by the costing estimates presented here, these actions need not be especially expensive. Indeed, they are potentially cost-saving. The paper concludes with case examples of national governments that have successfully prioritized and financed environmental CGH. Because societal preferences may vary across time, government leaders seeking to protect the health of future generations must look beyond electoral cycles to enact policies that protect the environment and finance environmental CGH.

Introduction

“If we pollute the air, water, and soil that keep us alive and well, and destroy the biodiversity that allows natural systems to function, no amount of money will save us.”—David Suzuki

Human beings have always been exposed to contaminated water (e.g., from human and animal feces), to air pollution (e.g., from heating and cooking indoors), and to the elements (e.g., storms, floods and droughts). These and many other exposures persist today, and are the causes of much of the burden of disease that results from environmental factors. More recently, socioeconomic development models, consumption habits, and our reliance on goods and services unsustainably extracted from the environment have brought us to the present situation, in which the ability of the Earth to sustain human life into future generations is in question.Citation1 Ocean acidification, climate change, land degradation, water access, fish stocks, and biodiversity loss are all inextricably linked with the unsustainable habits of human consumption, posing serious risks to health and challenging global health gains made thus far. In coming decades, population growth and increasing urbanization will further amplify both humanity’s impact on the environment and the resulting health effects.Citation2 While there have been major health successes in recent decades, for example in reducing the burden of infectious diseases and child mortality, threats to the environment may undermine these gains, particularly among vulnerable populations and communities.Citation3,Citation4

To safeguard our continued survival, human beings need to build societies that function within the planetary boundaries and minimally disrupt essential systems that support life. In the context of environmental degradation, protecting human health in current and future generations depends to a large extent on activities outside of the health sector. Sectors that compete for public financing—such as education, national security and defense, infrastructure development, agriculture and forestry, mining and natural resources, and parks and wildlife—all include interventions that could qualify for public financing because they generate Common Goods for Health (CGH).

This article contributes to building the case for public financing of environmental CGH (as defined in ) by defining the CGH concept as including both environmental health and the protection of ecosystem services.Citation8 Furthermore, inaction on environmental protection can lead to escalating health costs, further endangering the sustainability of health financing. It is therefore critical that financing for environmental CGH is accompanied by strong national and supranational action to prevent escalating health costs and contribute to a future where the environment can continue to sustain life on Earth.

TABLE 1. Key Terms

We begin this article by briefly reviewing the rationale for why governments should invest in environmental CGH and identifying those functions. We then conduct an exploratory empirical analysis to provide an argument for government intervention in environmental CGH given potential impacts on public health expenditure and considering the importance of governments in environmental performance. We then specify functions that should be prioritized by governments, with illustrative costing to show the costs associated with these environmental CGH. Finally, we conclude with case examples of how national governments have successfully prioritized and financed these goods. We do not address specific mechanisms for financing environmental CGH, as these are included in other articles in this special issue that discuss global CGH and country-level financing mechanisms.Citation9,Citation10

Why Should Governments Invest In Environmental CGH?

In this section, we briefly review how environmental threats have significant impacts on human life and note that markets fail to provide environmental protections for health. We therefore argue that investing in environmental CGH is compatible with global goals on health and intergenerational equity, requiring collective action beyond national governments.

Environmental Threats Have Direct Impacts on Health

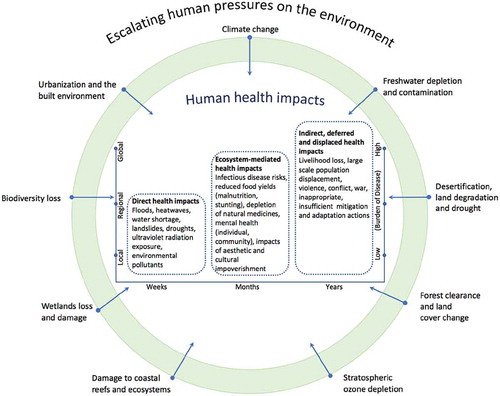

In recent years, the term “planetary health” (as defined in ) has been introduced as shorthand for the concept of the interconnectedness of planetary functioning and the health of humans and Earth’s other inhabitants. Literature on planetary health indicates that environmental degradation has and will continue to have long-term and substantial health effects.Citation11 In 2005, the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment found that these health effects are mediated by a number of causal pathways including changes in climate, extreme weather events, water scarcity and drought, ecosystem destruction, changes in the spread of microorganisms, and pollution of air and water.Citation12,Citation13 The major channels by which escalating human pressure on the environment impact health are summarized in .

FIGURE 1. Harmful Effects of Environmental Change and Ecosystem Impairment on Human Health

Source: Adapted from Refs. Citation14 and Citation15

Among the forces depicted in , indirect and long-term health impacts that could cause the highest global burden of disease are of great concern. Different ecosystem impairments cannot be examined in isolation because inaction on one front can have repercussions on another.Citation16,Citation17 This is particularly true for climate change, the impacts of which depend on a range of factors that make some regions of the world more vulnerable than others.Citation18 However, action on those are beyond the scope of this paper, which is focused on currently-financed responses to direct ecosystem-mediated health impacts.

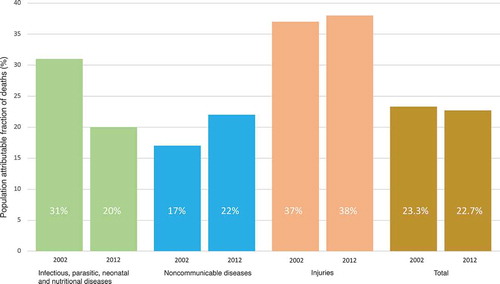

While these impacts are difficult to observe due to time lag and multiple causality, increasing evidence is emerging on their overall consequences, particularly regarding non-communicable diseases (NCDs). The importance of NCDs as causes of morbidity and mortality has grown over time ().Citation19 A recent World Health Organization (WHO) report calculated that 23% (95% C.I.: 13-34%) of deaths and 22% (95% C.I.: 13-32%) of Disability Adjusted Life Years (DALYs) globally are attributable to modifiable environmental risk factors. Two-thirds (8.2 million) of all deaths attributable to preventable environmental factors were directly caused by NCDs, predominantly by stroke and ischemic heart disease directly linked to the combustion of fossil fuels, and more generally to production and consumption patterns.

FIGURE 2. Burden of Disease from Environmental Risks by Disease Category, 2002 and 2012

Source: Reproduced from Ref. Citation5

While discussions about the impact of environmental factors on human health often focus on diseases that are directly associated with specific environmental risks, the association between the environment and health goes beyond these direct relationships. In fact, it has been argued that calculations of environmental burden of disease, including for DALYs and economic costs associated with chemical exposure, have vastly underestimated the costs associated with preventable environmental risks.Citation20 In this series, Gaudin and colleagues find that few interventions for health that are recommended on the basis of cost-effectiveness are related to environmental risk.Citation7 Yet, when looking at environmental CGH beyond direct and immediate health risks, one needs to account for dimensions, such as the effects of inaction on the health of future generations (intergenerational equity).

Markets Fail to Provide Sufficient Environmental Protection for Health

The economic rationale for public financing of CGH, as presented elsewhere in this special issue, limits the realm of CGH to interventions that have the characteristics of public goods (non-rival and non-excludable) or that generate large benefits to society that are not accounted for adequately by the private sector (externalities).Citation7 Examples abound of environmental protection activities that qualify under the market failure argument for CGH, including interventions aimed at improving the quality of the air, developing sustainable food systems, preserving biodiversity, reducing greenhouse gas emissions, and encouraging carbon sinks. As a result, governments, either at the national or global levels, must intervene to finance environmental CGH in addition to other CGH.Citation21

Exploratory Empirical Analysis

Although protecting the environment clearly has significant impacts on health outcomes, the case for public financing of environmental CGH can only be made if: a) public funding for these environmental services does not crowd out other funding for health in budget allocations; and, b) governments have a significant role to play in environmental preservation. The case can be further strengthened if spending on environmental protections reduces pressure on existing health expenditures.

These considerations have to date received little or no attention in the empirical literature. Current empirical evidence linking environmental protection and health expenditure is limited. A recent study on ambient air quality in China indicated that PM2.5 emissions have both significant negative effects on life expectancy and increase expenditures on health in the short- and medium-terms. Reducing PM2.5 concentrations to WHO’s safe standard could have saved China 42 billion USD in healthcare spending—this amounted to nearly 7% of China’s total health expenditure in 2015.Citation22 Thus far, however, this study is unique; more empirical evidence is badly needed on various dimensions of environmental performance. For example, no empirical evidence exists on whether increasing public funding for environmental protection reduces public resources for the health sector. Finally, the empirical literature does not provide indications of the extent to which governance and government policy matter in determining environmental performance at the country level.

In this section, we discuss the empirical models we have developed to examine these questions. Links between health expenditures and both environmental performance and environmental expenditure are explored below in the first series of empirical models (EM-A). The link between environmental performance and governments is explored in a second series of empirical models (EM-B).

Data and Methods

The exploratory empirical evidence presented below is based on country-level data from 178 countries with yearly observations (yet, unbalanced) between 2000 and 2017. The database was created by merging data from several internationally-recognized sources, including Yale University, WHO, World Bank, the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), UNESCO, the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME), and the Center for Systemic Peace.Citation23–Citation31 Detailed information about data sources, construction of variables, estimation methods, validity tests, summary statistics, and additional results for sensitivity analysis are presented in Appendix 1 (see supplemental material). The statistical methods used in estimating the model (panel data random-effects combined with instrumental variables methods) ensure results are not biased by either heterogeneity and/or endogeneity issues that typically plague these types of models—this was checked using various statistical tests reported in Appendix 1 (see supplemental material).Citation32,Citation33

Empirical Models A: Financing Environmental CGH is Compatible with Financial Sustainability of the Health System

In EM-A, we explore the linkages between health expenditures and environmental expenditures and performance. We begin with two propositions: (a) public spending on environmental protection does not crowd out public health spending despite limited government budgets; and, (b) good performance on ecosystem vitality is associated with lower public health expenditure. Regarding the first proposition, “crowding out” is considered in terms of budget funds. Given a limited budget, it is possible that increasing funding to the environmental sector would decrease funding to the health sector.

We test whether government spending on the environment and performance on ecosystem services are related to public health expenditure, controlling for the effects of income, total government expenditure, private share in health spending, population over 65, size, region, and time. Performance on ecosystem vitality is measured using the composite ecosystem vitality indicator in the 2018 Environmental Performance Index (EPI).Citation23 The index includes measures of biodiversity and habitat, energy and climate change, fisheries and forest (when applicable), and soil and water quality (for details, please see Table A1.1 in supplemental material and Ref.Citation23) Results of this test are presented in (additional summary statistics are reported in Appendix 1, Table A1.7 in supplemental material).

TABLE 2. Environmental Protection and Health Expenditure Relationships

Within the small sample of 22 OECD countries for which comparable data on environmental expenditure are available, there is no evidence that public spending on environmental protection crowds out spending on health (models A1 and A1-IV). We do find that ecosystem vitality is associated with lower public health expenditure in OECD countries, although this relationship becomes statistically insignificant (p-value = 0.11) when considering a larger set of countries spanning all income levels and regions. We also test whether the relationship between environmental expenditure and ecosystem vitality differs by regions or income groups but find no significant differences.

Empirical Models B: Governments Play a Significant Role in Environmental Performance

In EM-B, our analysis seeks to identify common features of countries that perform well on environmental health and protection. The environmental performance variables used are all constructed with underlying variables that link to policy (such as protected areas, greenhouse gas emissions, etc.) so that the analysis may be extrapolated to identify government actions that may facilitate public action on environmental CGH. However, the different indicators related to governance and politics are highly correlated with each other; this makes it difficult to identify aspects of governments that are more or less associated with environmental performance (correlation coefficients are provided in Appendix 1, Table A1.2 in supplemental material). Using factor analysis (reported in Appendix 1, Tables A1.3 and A1.4 in supplemental material), we reduce the number of variables to three dimensions: governance (which captures most variation in “rule of law,” “government effectiveness,” “regulatory quality” and “control of corruption”), politics (captures “voice and accountability” and the Polity score) and political stability. The estimated effect of these government variables is calculated net of other variables in the model including countries’ income levels (instrumented using adult literacy rates, see Appendix 1 in supplemental material for more detail), population characteristics, regional effects and time trends.Footnote[a] All independent variables are based on EPI data.Footnote[b] The ENVH variable captures all EPI indicators based on environmental health outcomes (measured in terms of avoided mortality and morbidity linked to environmental outcomes).Citation29 Indicators on forests and marine areas protection produced no significant associations with explanatory variables, whether or not we included additional variables such as forest rents (this may be due to the significantly smaller sample size, since countries are filtered out if they are either landlocked or if forest cover is too limited). All other dimensions of EPI revealed some significant relationships with variables of interest; results are reported in (with summary statistics in Appendix 1, Tables A1.8–9 in supplemental material).

TABLE 3. Country-Level Determinants of Policy-Related Environmental Performance

The regressions reveal some significant relationships that could be explored in future research. In particular, and with the caveat that such summary measures cannot adequately describe all relevant dimensions of governance and the political system, we find that the governance dimension dominates the relationship for performance in environmental health outcomes (ENVH). The political variable—incorporating the degree of people’s participation in the political system, voice and accountability—is positively associated with performance in ambient air quality (AIR) and biodiversity and habitat (BDH). Tests of joint significance reveal that, in all models except B5 (APE), the three government/politics-related variables are significant determinants of performance; the same is true for governance and politics together. The time trend is not significant except for health outcomes (ENVH). We note some significant differences across regions (constant term) in Ecosystem Vitality models (3–5), but none emerged in the environmental health models (not reported).

This analysis suggests that societal dimensions beyond economics are important determinants of environmental performance. In fact, while we do find that income (GDP) has a positive effect in some regressions, pre-test analyses revealed that neither macroeconomic variables (including investment/GDP, export/GDP and labor force participation), nor poverty and inequality measures nor rents from oil and coal had any significant impact on regression results. Although data limitations may explain some of these null results (particularly on poverty/inequality and resource rents), the analysis produced significant results for governance and participation given the same limitations. This indicates that governments have a significant role in improving the environment in areas that are critical to health outcomes, particularly biodiversity protection and ambient air quality.

Identifying Environmental CGH For Public Financing

Examples of Priority CGH Intervention that Support Eco-system Services

In this section, we mention some of the numerous functions generating increasing interest and an expanding evidence base regarding their importance to human health. Environmental CGH must be specified in ways that allow national and global governments to effectively prioritize and finance them.

presents our list of interventions that qualify as priority environmental CGH and have a demonstrated significant impact on human health. This table was compiled using the CGH definition laid out by Yazbeck and Soucat,Citation8 with extensive consultation with WHO’s Public Health, Environmental and Social Determinants of Health expert team and CGH technical expert group. It represents current government concerns, and corresponds mostly (although not exclusively) to the exposure labeled “urbanization and the built environment” and to health impacts labeled “direct,” as shown in . It also corresponds to a lesser extent to “ecosystem mediated” health impacts. In addition to identifying notable environmental CGH based on the CGH categories used throughout this series, the table also specifies potential responsible institutions and sectors.Citation7 This additional classification is particularly relevant here, given the need for multisectoral action to finance and provide environmental CGH. The list is only illustrative—it requires adaptation to different contexts, as specific priorities vary by country depending on the state of the environment and the responsible institutions depend on country-specific institutional structures.

TABLE 4. Environmental CGH

Environmental CGH Costing Exercise

To give a sense of their scale and scope, we also conducted a preliminary analysis of the global resource costs for three types of environmental CGH: (a) water quality testing; (b) climate change mitigation and adaptation in health facilities; and, (c) clean cooking subsidies to combat household air pollution. These were selected to represent three separate areas where health and the environment intersect, namely water pollution, climate change, and air pollution. Further, these three examples represent initiatives in which the health sector could be a leader in financing and implementation. Finally, each analysis used existing costing estimates and/or global guidance to create country-level models—these can applied to any country with publicly available data. The resulting costs are grouped into low-income countries (LIC), lower-middle-income countries (LMIC), and upper-middle-income countries (UMIC).

The results of the costing analysis are presented in . The costs cited represent what it would take to have these environmental CGH in place, without considering incremental steps necessary for real-life implementation (see Technical Appendix 2 in supplemental material for methods and detailed analysis).

TABLE 5. Costs for Obtaining Environmental CGH in 67 Low- and Middle-Income Countries

The first environmental CGH costed is water quality monitoring. Information on water quality is a crucial precursor for understanding how the quality of drinking water is affected by climate change, pollution, and other factors. This information is required to mobilize efforts towards combating climate change and managing and protecting water sources. Thus, conducting microbial water quality monitoring and generating information is an essential environmental CGH.

Our projected cost of water quality monitoring is based on what it costs to consistently test water sources in urban and rural areas in accordance with global guidelines (for more details, see Technical Appendix 2A in see supplemental material).Citation36,Citation37 The resulting cost is relatively minimal, at just over 0.03 USD per capita per year. This estimate, however, only calculates the costs of monitoring water quality where drinkable water is already available. Due to lower access to safe water in LIC, the costs are slightly lower in LIC as compared to MIC. Making drinking water safe is a different initiative at a different scale; if those investments were costed, the estimates above would likely be higher, particularly among LIC.Citation38

The second CGH costed is the “greening” of public sector health facilities to help mitigate the effects of climate change. For example, the UK made an explicit attempt to mitigate the effects of its National Health System (NHS) on climate change. The Sustainable Development Unit of the NHS carried out a comprehensive analysis on which factors within the British health system had the largest impact on carbon emissions; they further estimated the impact and relative cost-effectiveness of several possible interventions.Citation39 Some interventions were found to be particularly effective in mitigating the health sector’s impact on climate change; others interventions both reduced carbon emissions and resulted in cost savings for the health system within a few years. Similarly, the SMART hospital initiativeFootnote[c] in the Caribbean region sought to make health facilities both more resilient to natural disasters and more climate-friendly. It identified effective interventions for reducing facilities’ carbon footprints, including using renewable energy sources, implementing energy saving interventions (such as changing to LED lights and installing movement-based sensors for light switches), and installing water saving mechanisms (including rain catchment systems and leak-minimizing plumbing).Citation40

To compute the cost estimate for mitigating the environmental impact of health facilities presented in , we modelled applying a series of standard green interventions stemming from the initiatives mentioned in a subset of health facilities in LMICs (see Appendix 2B in see supplemental material for further detail on this analysis). The scale of this environmental CGH is significantly larger than the others because it requires making adjustments to the health infrastructure. However, greener facilities use less electricity, have lower carbon footprints, contribute to mitigating climate change, and consume less water. Thus, while the costs of implementation include financing for capital improvements and start-up costs, these interventions significantly reduce recurring and operating costs of health facilities over time. While we have not modelled the long-term effects, we suspect that these could ultimately prove to be cost-saving interventions.

The third environmental CGH we costed is subsidizing “clean cooking,” in order to mitigate indoor air pollution. Household air pollution is as significant a factor in worsening human health as outdoor and ambient air pollution.Citation41 The key driver of household air pollution in most LMICs is the use of inefficient technologies and fuels for cooking food.Citation42 Indeed, the global Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) identify clean cooking as a clear priority for the world. SDG target indicator 7.1.2. makes increasing primary reliance on clean fuels and technologies at the household level a priority. Many countries already subsidize clean cookstoves and fuel. To compute our estimates in , we model the cost of shifting populations currently using polluting fuels in LMICs to one of two cleaner-cooking technologies: advanced combustion/gasifier biomass stoves and Liquefied Petroleum Gas (LPG)-based stoves (for more detail see Appendix 2C in see supplemental material). Several governments have implemented schemes to provide subsidies to households for adopting clean cooking; one example is the Pradhan Mantri Ujjwala Yojana scheme in India.Citation43 However, affordability issues constrain such initiatives given the relatively high costs of the cleaner cookstoves and the high number of eligible households. These initiatives resort to either focusing only on the poorest households or only on the initial capital cost of the cookstove itself.

Our model represents significant change towards reducing household air pollution by providing all eligible households with one of two types of cleaner cookstoves. However, this creates a substantial cost. Coordination between the health and energy sectors could help to reduce this burden. These efforts could also link with existing initiatives that target vulnerable households, such as cash transfers. As with many investments in disease prevention, subsidizing clean cookstoves would not generate a direct financial return. However, investing in this environmental CGH now would yield a lower burden of NCDs and reduced costs to the health system for treating them in the future.

Further work is urgently needed to understand the costs and budget implications of investing in a more comprehensive set of environmental CGH. This initial exercise covers only a small subset of the range of environmental CGHs that exist, but it provides an idea of the possible scale of these costs. Furthermore, as seen in , environmental CGH cut across many sectors, so coordination among government agencies and ministries will be necessary to ensure financing and provision of these functions.

Successful Environmental CGH Interventions at the National Level

Building the case for prioritizing environmental CGH is one step. Another key component of promoting environmental CGH is addressing implementation dynamics to ensure that actions are actually financed and undertaken. In this section, we present notable examples of successful action on environmental CGH in the world’s two most populous countries, namely China and its investment in air quality, and India’s intervention on water and sanitation. Both national and international pressures were applied to get these two governments to prioritize investment and provision of environmental CGH. Collective action in the form of public demand put pressure on political leaders to mobilize investments and prioritize environmental CGH. As described below, China and India were able to garner government support to different categories of intervention. In China, the government decided to subsidize environmental protection efforts, while in India, mandatory revenue sources proved instrumental in mobilizing both public and private resources.

Air Quality Improvement in China

China faces massive environmental health challenges. Until recently, environmental regulation was weak due to lack of coordination across sectors and difficulties in pacing institutional development to keep up with rapid economic growth.Citation44 However, increasing PM2.5 pollution has generated population concerns about health risks. In a 2016 survey on perceived health risks from air pollution in the cities of Shanghai, Wuhan, and Nanchang, 46% of participants were anxious about exposure to polluted air.Citation45 In recent years, urban citizens in China have been speaking out more—often via social media—on issues they believe affect their health and wellbeing. Specifically, middle-class citizens express complaints and disseminate petitions to organize against industrial projects in their communities. These, along with international pressure, have helped spur action by the Chinese government to decisively address air pollution.Citation44,Citation46

In 2013, the country introduced its strongest environmental protection policy to date, the Action Plan on Prevention and Control of Air Pollution, which targets reductions in PM2.5.Citation47 The Ministry of Environmental Protection pledged 2 million USD annually to the China Trust Fund to aid in implementing these regulations, promote green economies, and strengthen governance in Africa and Asia.Citation48 More recently, in October 2017 President Xi Jinping announced the creation of the Ministry of Ecology and Environment (MEE) to try to overcome challenges associated with the multisectoral nature of environmental health services. The MEE has consolidated staff and functions from various ministries into a single agency for primary management, coordination, and planning of national policies to protect the environment and promote ecology.Citation49 Budget funds from central and local governments have increased resources and subsidies to finance environmental protection for key regions, in particular air quality control efforts, and to transfer payments for interventions in key ecological zones.Citation50

Water and Sanitation Services in India

In 2014 India’s Prime Minister Narendra Modi launched an ambitious national program to address alarming statistics from the 2011 National Census showing high rates of open defecation in the country. Open defecation has various harmful effects, polluting the environment and undermining health, leading to the spread of disease and other social problems. The program, called the Swachh Bharat Mission (SBM), aimed to eliminate open defecation by 2019. SBM projected an unprecedented total cost: 24 billion USD overall for the initiative. Funding for SBM was planned to come from the Government, the private sector, and civil society over the five years, with 1.3 USD billion allocated from the 2016 Union Budget of India.Citation51 Media tactics, including engaging national celebrities and heavily publicizing news on the suicides of two girls who were gang-raped while relieving themselves outside, were used to harness national engagement and investment.Citation52,Citation53

A 0.5% service tax was levied on commodities, such as insurance, hotels, and restaurants. Corporate Social Responsibility contributions, whereby all companies with a certain net worth must dedicate 2% of their profits to SBM, have also contributed greatly to funding the initiative.Citation51 Other funding has come from municipal bonds, the Ministry of Finance budget, and the World Bank. The mandatory nature of many of these funding sources has been important to securing financing for SBM. Due to the decentralized government in India, implementation and spending have been uneven across states, which is an issue that needs continued attention and investment as SBM moves forward.Citation54

Conclusion

Progress on environmental protection and its impact on health requires sound governance and leadership. This article provides data to support countries seeking a rationale for taking action to protect the environment. Preserving the environment has its own intrinsic value, and also represents a good investment in the health and well-being of human beings. The empirical analysis presented in this paper highlights the strong link between environmental performance and political/governance factors, showing that there is a clear role for government action. As shown by the costing estimates presented here, these actions need not be especially expensive. Indeed, they are potentially cost-saving.

Government action to preserve environmental CGH can be integrated into broader social and economic policies. To create lasting change to sustain future generations necessitates challenging the political calculations that often result in leaders focusing their work on programs with short-term impacts. While societal preferences may vary across time, government leaders must be willing to implement policies that protect the environment and finance environmental CGH now in order to protect the health of future generations.

The complexity of environmental action means that policy makers and practitioners concerned about the environment must engage with a wide array of political, legal, and financial systems to successfully catalyze change. Scientists develop new and more affordable technologies to adapt to and mitigate climate change, economists estimate the costs of these solutions, and social scientists study their impact on the most vulnerable. These experts’ contributions, however, cannot create either immediate or long-term change without support from political leadership at all levels. In addition, as the number of climate migrants increases, and the unequal distribution of resources (particularly access to technologies in LICs) persists, additional analysis is urgently needed on the political economy of acting on climate change.Citation55

Finally, public financing and coordination (across ministries, levels of government, and the public and private sectors) at national and supranational levels are critical components of moving from just speaking about the importance of environmental protection to actually taking meaningful action.Citation10 While many of the environmental CGH listed in are not typically provided or financed through the health sector, the health sector still has important roles, including providing the evidence base, monitoring progress, and connecting with other sectors. Together with other sectors, the health sector has significant space to directly take actions and implement interventions that promote planetary health.

Disclosure Of Potential Conflicts Of Interest

SL, SG, CC, AE, and OH have received consulting fees from WHO. SL is a Consulting Editor at The Lancet. All authors declare no other competing interests.

Supplemental Material Appendix 1

Download MS Word (66.3 KB)Supplemental Material Appendix 2

Download MS Word (31.6 KB)ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors wish to thank Susan Sparkes and the WHO Health Governance and Financing team for their support and guidance in preparing this paper and the technical expert group. We also gratefully acknowledge the input of the following individuals who gave time and effort to this process: WHO HQ staff members Diarmid Campbell-Lendrum, Fiona Gore, Richard Johnston, Bruce Gordon, Jennifer de France, Natalie Roebbel, Kate Medlicott, Margaret Montgomery, Marina Takane, Emilie Van Deventer, Carolyn Vickers, Frank Pega, and Heather Adair-Rohani. Additionally, we would like to thank our four reviewers on this paper who provided invaluable feedback.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed on the publisher’s website. All appendices mentioned in the text are available in the supplemental data.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

[a] Variables capturing the country’s economic interests, either in the service of the environment or against it, were included in pre-test analyses. However, they were excluded from the results on the basis that they did not yield significant results, did not affect results on other variables, and did not improve model fit.

[b] Two dimensions of ecosystem vitality in EPI—the water resources index, measured using wastewater treatment connections, and the agriculture index, based on sustainable nitrogen management—are excluded because they are derived from data that are constant over time (see ref.Citation19) Thus we could not take advantage of the panel data structure to account for country-specific heterogeneity. In addition, they are less directly related to government policy than the other dimensions.

[c] Funded by DFID and implemented by PAHO.

References

- Whitmee S, Haines A, Beyrer C, Boltz F, Capon AG, de Souza Dias BF, Ezeh A, Frumkin H, Gong P, Head P, et al. Safeguarding human health in the Anthropocene epoch: report of the Rockefeller Foundation-Lancet commission on planetary health. Lancet. 2015 Nov 13;386(10007):1973–2028. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60901-1.

- Capon A. Harnessing urbanisation for human wellbeing and planetary health. Lancet Planet Health. 2017;1:e6–e7. PMID 29851592. doi:10.1016/S2542-5196(17)30005-0.

- Watts N, Adger WN, Agnolucci P, Blackstock J, Byass P, Cai W, Chaytor S, Colbourn T, Collins M, Cooper A, et al. Health and climate change: policy responses to protect public health. Lancet. 2015 Nov 7;386(10006):1861–914. PMID: 26111439. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60854-6.

- The Lancet Planetary Health. A sixth mass extinction: why planetary health matters [editorial]. Lancet Planet Health. 2017 Aug;15:e163. doi:10.1016/S2542-5196(17)30083-9.

- Prüss-Ustün A, Wolf J, Corvalán C, Bos R, Neira M. Preventing disease through healthy environments: a global assessment of the burden of disease from environmental risks. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2016.

- Constanza R, d’Arge R, de Groot R, Farber S, grasso M, Hannon B, Limburg K, Naeem S, O’Neill R, Paruelo J, et al. The value of the world’s eco-system services and natural capital. Nature. 1997;387:253–60.

- Gaudin S, Smith P, Soucat A, Yazbeck AS. Common goods for health: economic rationale and tools for prioritization. Health Syst Reform. 2019;5(4):280-292.

- Yazbeck AS, Soucat A. When both markets and governments fail health. Health Syst Reform. 2019;5(4):268-279.

- Sparkes SP, Kutzin J, Earle AJ. Financing common goods for health: a country agenda. Health Syst Reform. 2019;5(4):322-333.

- Yamey G, Jamison D, Hanssen O, Soucat A. Financing common goods for health: when the world is a country. Health Syst Reform. 2019;5(4):334-349.

- Seltenrich N. Down to Earth: the emerging field of planetary health. Environ Health Perspect. 2018 Jul;126(7):072001. PMID 30007903. doi:10.1289/EHP2374.

- Millennium Ecosystem Assessment. Ecosystems and human well-being: synthesis. Washington (DC): Island Press; 2005. [accessed 2019 Mar 21]. https://www.millenniumassessment.org/documents/document.357.aspx.pdf.

- Millenium Ecosystems Reports. [accessed 2019 Mar 21]. https://www.millenniumassessment.org/en/Reports.html.

- Corvalan C, Hales S, McMichael A. Ecosystems and human well-being—health synthesis. Geneva (Switzerland): World Health Organization; 2005

- Butler C, Corvalan C, Koren H. Human health, well-being, and global ecological scenarios. Ecosystems. 2005 Mar;8:153–62. doi:10.1007/s10021-004-0076-0.

- Heft-Neal S, Burney J, Bendavid E, Burke M. Robust relationship between air quality and infant mortality in Africa. Nature. 2018;559:254–58. doi:10.1038/s41586-018-0263-3.

- Vandyck T, Keramidas K, Kitous A, Spadaro JV, Van Dingenen R, Holland M, Saveyn B. Air quality co-benefits for human health and agriculture counterbalance costs to meet Paris Agreement pledges. Nature Commun. 2018;9:4939. doi:10.1038/s41467-018-06885-9.

- Watts N, Amann M, Ayeb-Karlsson S, Belesova K, Bouley T, Boykoff M, Byass P, Cai W, Campbell- Lendrum D, Chambers J, et al. The Lancet countdown on health and climate change: from 25 years of inaction to a global transformation for public health. Lancet. 2018;391(10120):581–630. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32464-9.

- Remoundou K, Koundouri P. Environmental effects on public health: an economic perspective. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2009;6(8):2160–78. doi:10.3390/ijerph6082160.

- Grandjean P, Bellanger M. Calculation of the disease burden associated with environmental chemical exposures: application of toxicological information in health economic estimation. Environ Health. 2017;16:123. doi:10.1186/s12940-017-0340-3.

- OECD. Public goods and externalities: agri-environmental policy measures in selected OECD countries. Paris (France): OECD; 2015. [Accessed 2019 Mar 21]. doi:10.1787/9789264239821-en.

- Barwick PJ, Li S, Rao D, Zahur NB. The morbidity cost of air pollution: evidence from consumer spending in China [NBER Working Paper No. w24688]. Cambridge (MA): National Bureau of Economic Research; Jun 2018.

- Wendling ZA, Emerson JW, Esty DC, Levy MA, de Sherbinin A. Environmental Performance Index. New Haven (CT): Yale Center for Environmental Law & Policy; 2018. [accessed 2019 Apr 15]. https://epi.yale.edu/.

- World Health Organization. Global Health Expenditure Database (GHED). Geneva (Switzerland): World Health Organization; [accessed 2018 Nov 16]. https://apps.who.int/nha/database.

- World Bank. Health Nutrition and Population (HNP) Statistics Database and World Development Indicators (WDI). Washington (DC): The World Bank Group; [Accessed 2018 Nov 16]. https://databank.worldbank.org/data/reports.aspx?source=health-nutrition-and-population-statistics.

- International Monetary Fund. International Financial Statistics (IFS) Database. Washington (DC): IMF. [accessed 2018 Nov 16]. https://www.imf.org/en/Data#global.

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. OECD Statistics. Paris (France): OECD. [accessed 2018 Dec 18]. https://stats.oecd.org/.

- Institute of Health Metrics and Evaluation. Global Burden of Disease database (GBD). Seattle (WA): University of Washington, IHME. [accessed 2019 Apr 4]. http://www.healthdata.org/gbd/data.

- UNESCO Institute for Statistics (UIS). UIS Database. Paris (France): United Nations Educational Scientific and Cultural Organization. [accessed 2019 Mar 30]. http://uis.unesco.org/.

- Kaufmann D, Kraay A. Worldwide Governance Indicators (WGI). Washington (DC): The World Bank Group. [Accessed 2018 Nov 13]. https://info.worldbank.org/governance/wgi/#home.

- Center for Systemic Peace. Integrated Network for Societal Conflict Research, Polity IV Dataset. Vienna (VA): Center for Systemic Peace. [accessed 2019 Feb 22]. http://www.systemicpeace.org/polityproject.html.

- Baltagi BH. Econometric analysis of panel data. 5th ed. Chichester(UK): Wiley; 2013.

- Balestra P, Varadharajan-Krishnakumar J. Full information estimations of a system of simultaneous equations with error component structure. Econometric Theory. 1987;3:223–46. doi:10.1017/S0266466600010318.

- Hausman JA. Specification tests in econometrics. Econometrica. 1978;46:1251–71. doi:10.2307/1913827.

- Davidson R, MacKinnon JG. Estimation and inference in cconometrics. New York (NY): Oxford University Press; 1993.

- Baumann E, Montangero A, Sutton S, Erpf K. WASH technology information packages. Copenhagen (Denmark): UNICEF; 2010.

- World Health Organization. Guidelines for drinking-water quality. Geneva (Switzerland): WHO; 2011. p. 303–04.

- Hutton G, Varughese M. The costs of meeting the 2030 sustainable development goal targets on drinking water, sanitation, and hygiene. Washington (DC): The World Bank; 2016.

- Sustainable Development Unit. Securing healthy returns: realising the financial value of sustainable development. United Cambridge (UK): Sustainable Development Unit; 2016.

- Pan American Health Organization, World Health Organization. SMART hospitals toolkit. Washington (DC): PAHO Health Emergencies Department; 2017. [accessed 2019 May 22]. https://www.paho.org/disasters/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=1742%3Asmart-hospitals-toolkit&Itemid=911&lang=en.

- World Health Organization. Burning opportunity: clean household energy for health, sustainable development, and wellbeing of women and children. Geneva (Switzerland): World Health Organization; 2016.

- International Energy Agency. World Energy Outlook 2018. Paris (France): IEA; 2018.

- Dabadge A, Sreenivas A, Josey A. What has the Pradhan Mantri Ujjwala Yojana achieved so far? Econ Polit Wkly. 2018;LIII:69–75.

- Wang A. Explaining environmental information disclosure in China. Ecol Law Q. 2018;44:865.

- Liu X, Zhu H, Hu Y, Feng S, Chu Y, Wu Y, Wang C, Zhang Y, Yuan Z, Lu Y. Public’s health risk awareness on urban air pollution in Chinese megacities: the cases of Shanghai, Wuhan and Nanchang. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2016;13(9):845. doi:10.3390/ijerph13121252.

- van Rooij B. The People vs. Pollution: understanding citizen action against pollution in China. J of Contemp China. 2010;19(63):55–77. doi:10.1080/10670560903335777.

- Clean Air Alliance of China, RAP. State council - Air pollution control action plan: China clean air updates. Beijing: Clean Air Alliance of China; 2013. [Accessed 2019 Jun 18]. http://en.cleanairchina.org/product/6346.html.

- UN Environment. China Trust Fund. [Accessed 2019 Jun 19]. http://www.unenvironment.org/about-un-environment/funding/china-trust-fund.

- Ministry of Ecology and Environment. Mandates. Beijing: Ministry of Ecology and Environment; 2017 Oct. [accessed 2019 Jun 18]. http://english.mee.gov.cn/About_MEE/Mandates/.

- National People’s Congress of the People’s Republic of China. Report on China’s central, local budgets 2017. Beijing: National People’s Congress; 2018 Mar. [Accessed 2019 June 19]. http://www.npc.gov.cn/englishnpc/Special_13_1/2018-03/04/content_2041361.htm.

- PTI. Budget 2016: swachh Bharat Abhiyan gets Rs 9,000 crore. Econ Times. 2016 Feb 29. [accessed 2019 Sep 12]. https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/articleshow/51193662.cms?utm_source=contentofinterest&utm_medium=text&utm_campaign=cppst.

- Balachandran PK. Challenges faced by Modi’s ‘Clean India’ campaign. Daily FT. 2018 Apr 7. [accessed 2019 Jun 18]. http://www.ft.lk/columns/Challenges-faced-by-Modi-s–Clean-India–campaign/4-652904.

- Nair A. Women and girls are dying for lack of toilets; businesses can help. Guardian. 2014 Jun 17. [accessed 2019 Jun 18]. https://www.theguardian.com/sustainable-business/women-girls-india-toilets-sanitation-business.

- Norman G, Renouf R. Financing Swachh Bharat: finding the money for Clean India [Finance Brief 12]. Public Finance for WASH; 2016. [accessed 2019 Jun 20]. https://www.publicfinanceforwash.org/sites/default/files/uploads/Finance%20Brief_12%20-%20Swachh%20Bharat%20-%20finding%20the%20money%20for%20Clean%20India.pdf.

- Tanner T, Allouche P. Towards a new political economy of climate change and development. IDS Bull. 2011;42(3). doi:10.1111/j.1759-5436.2011.00217.x.