ABSTRACT

COVID-19 has shocked all countries’ economic and health systems. The combined direct health impact and the current macro-fiscal picture present real and present risks to health financing that facilitate progress toward universal health coverage (UHC). This paper lays out the health financing mechanisms through which the UHC objectives of service coverage and financial protection may be impacted. Macroeconomic, fiscal capacity, and poverty indicators and trends are analyzed in conjunction with health financing indicators to present spending scenarios. The analysis shows that falling or reduced economic growth, combined with rising poverty, is likely to lead to a fall in service use and coverage, while any observed reductions in out-of-pocket spending have to be analyzed carefully to make sure they reflect improved financial protection and not just decreased utilization of services. Potential decreases in out-of-pocket spending will likely be drive by households’ financial constraints that lead to less service use. In this way, it is critical to measure and monitor both the service coverage and financial protection indicators of UHC to have a complete picture of downstream effects. The analysis of historical data, including available evidence since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, lay the foundation for health financing-related policy options that can effectively safeguard UHC progress particularly for the poor and most vulnerable. These targeted policy options are based on documented evidence of effective country responses to previous crises as well as the overall evidence base around health financing for UHC.

Introduction

COVID-19 is exposing cracks in all sectors—from education to labor markets to health—among others. Some of these fault lines are novel and unexpected, while others were foreseen or exacerbated by the combination of the pandemic and the economic crisis that it triggered.Citation1 The health sector is experiencing hardships from all sides. The combined pressures of managing COVID-19, maintaining other essential health services, safeguarding the health and wellbeing of the health workforce, financing and distributing COVID-19 vaccination, and adjusting to a new fiscal reality in the face of economic constraints all require adjustments to how health is financed and delivered.Citation2,Citation3 These financing-related shifts extend beyond pure revenue concerns, and relate to a combination of short-term reallocation to purchase services across the system and long-term reorientation to avert future crises.

As countries emerge from the initial crisis phase of the pandemic to consider structural adjustments, reforms will need to be guided by strong evidence and a clear objective orientation focused on protecting and promoting health for all people. While COVID-19 may have shifted or rearranged certain priorities, the overarching objectives embedded within Universal Health Coverage (UHC) to ensure all people and communities are able to get the services they need, of good quality, without fear of financial hardship are all the more relevant.Citation4 In the immediate term, many of these services relate to COVID-19 testing, treatment, vaccination and prevention. They also involve getting back online essential services that have been disrupted and managing related consequences. These actions are all the more pressing for the increasing numbers of poor and vulnerable people who are suffering the most both in terms of health and economic impacts.Citation5

Policies oriented toward UHC are intrinsically important, but they also directly contribute to other societal goals by: (i) contributing to the economy through health sector improvements and employment (Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 8: decent work and economic growth); (ii) protecting against poverty through improved financial protection (SDG 1: end poverty in all its forms); (iii) contributing to reduced inequalities within and between countries (SDG 10: reduce inequality within and among countries); (iv) increasing overall productivity of current and next generations by fostering improved accumulation of human capital, and (v) bolstering savings and investments as people live longer lives. Therefore, we must go beyond simply stating that UHC is important, to consider the implications of the crisis that COVID-19 has triggered on the future trajectory of UHC progress.

This paper contributes to this process by analyzing the impact of COVID-19 on financing for UHC as a way to identify policies that can safeguard progress and protect health for all populations in the years and decades to come. It focuses on dynamics that will impact country-level decision-makers, rather than on global-level discussions and mechanisms. A coherent and well-aligned health financing system is a critical enabler for UHC.Citation6,Citation7 To analyze the dynamic relationship between financing and UHC, we review and update the evidence around UHC-related trends as well as factors that influence financing for UHC in the context of COVID-19. These factors include broader supply side issues related to macro-fiscal and budget allocation issues, as well as demand side factors stemming from individual health needs and service access. Data trends are analyzed to project future health financing dynamics. From a health financing perspective, the analysis focuses on those factors that will affect health spending and the related impact on UHC. It does not provide a deep-dive analysis into the consequences of COVID-19 on specific health financing functions, including issues of benefit design or strategic purchasing. This evidence base then serves as the foundation for proposed policy responses that focus on equity and redistributive policies needed to both safeguard and continue progress toward UHC now and into the future.

Reexamining the Commitment to UHC

There has been no shortage of calls for the importance of UHC in the context of COVID-19.Citation3,Citation8–10 These calls stem in part from experiences from those countries that have been able to better manage the pandemic’s impact on the health of its populations.Citation11–13 They also reflect the recognized relationships between communicable and non-communicable diseases, as well as environmental risk factors, which have been laid bare through COVID. Addressing these overlapping risks requires a systemic and universal approach that does not set up disease-by-disease or intervention-by-intervention silos, but rather establishes strong health systems aligned to the complete set of health needs of individuals and societies, including for prevention and management of risk-factors.Citation14,Citation15

COVID-19 has exposed deep fault lines in how the commitment to UHCCitation16 has been operationalized. While the fundamentals around policies that can contribute to UHC remain all the more relevant, the breakdown in systems to ensure service coverage and provide financial protection shows two critical priorities for action. These factors specifically consider the underlying systems needed to protect and promote health in the face of the current and future pandemics. This entails population- and individual-level interventions that ensure access to all health services, including those related to COVID-19.Citation17

First is the need for sufficient investment in Common Goods for Health.Citation18 These population-based activities and capacities are prerequisites for societies and health systems to be prepared for and to respond to crises and emerging threats. As demonstrated by the impact of COVID-19, these Common Goods for Health often suffer from under provision or are not provided at all due to fundamental market failures because they are either public goods or have large social externalities.Citation19 As a result, there is a limited private demand and a general collective action failure that requires government intervention to correct.Citation20 These functions, which are essential for the COVID-19 response, are also fundamental to both UHC and health security objectives, include institutional capacity for disease control and public health, information and surveillance, laboratory capacity, risk communication, regulation, fiscal instruments that promote health, and population services such as water and sanitation and environmental health. These capacities have been recognized as part of UHC through the inclusion of the International Health Regulations capacity index in the service coverage index measure of UHCCitation21; however, they have not been fully operationalized as evidenced by the impact the pandemic has had on countries and communities.

The second is the need to place equity at the center of the UHC agenda through redistributive efforts that ensure access and coverage for the poor and vulnerable. Again, COVID-19 has exposed the systemic inequities in the access to health care, with the poor, marginalized and minorities suffering disproportional losses.Citation22 This equity-sensitive approach to UHC is critical given improvements in average levels of attainment can mask growing inequalities. As shown by Wagstaff et al.,Citation23 the average inequality across select health-related Millennium Development Indicators fell between 1990 and 2011. However, relative inequality of child malnutrition and mortality actually increased in half of all countries. More specifically, in 28% of countries, service coverage inequalities rose and the coverage among the poorest 40% of the population decreased in 24% of countries.Citation23,Citation24 While the universality component of UHC is inclusive of the poor and marginalized, equity can suffer on the path to UHC without deliberate pro-poor policies. This is of particular relevance as poverty increases as a result of economic crisis; targeted and exceptional attention is needed for the most vulnerable in society. Addressing inequities requires government action in the form of policy reforms; however, more broadly there is a need to engage with underlying societal values and structures that have implications for the solidarity needed to move toward UHC.

Accountability of the commitments made to UHC requires joint monitoring of financial protection indicators together with service coverage metrics. This monitoring is even more necessary following the COVID-19 crisis as financial barriers and income contraction contribute to forgone care for essential health services.Citation25 Just as the service coverage index has been expanded to include IHR capacities, additional indicators, including those related to equity, malnutrition and Common Goods for Health, can be added to establish a more complete metric of access to health.

Financing for UHC

From a revenue perspective, the centrality of public financing in the form of compulsory (i.e. some form of taxation) pre-paid, pooled resources remains all the more important for UHC in the time of COVID-19.Citation26,Citation27 We know this relationship is nuanced; whereby, whether and to what extent this increase in public spending on health crowd-out out-of-pocket spending in real per capita terms depends on the design of health financing policy to effectively protect households.Citation28,Citation29 This entails going beyond revenue issues and examining the pooling, purchasing, benefit design, and public financial management channels through which those revenues actually reach the point of services and people.

For example, China’s massive expansion of public spending on health since 2000 (nearly 16,000% in real per capita terms)Citation30 enabled universal affiliation to explicit coverage schemes. While this reform led to a proportional increase of public relative to out-of-pocket spending on health, real per capita out-of-pocket spending still increased by 300%. The continued reliance on out-of-pocket sources in China’s scheme was largely due to the fee-for-service payment model combined with uncapped co-payments from users.Citation31,Citation32 During the same period, Thailand also increased public spending on health (by about 300% in real per capita terms)Citation30 to attain universal affiliation to explicit coverage schemes. In contract to China, the main scheme in Thailand used payment methods that eliminated incentives for supplier-induced demand, as well as co-payments at the point of delivery. As a result, the level of real per capita out-of-pocket spending did not increase, and there is strong evidence that Thailand successfully reduced the impoverishing effect of health spending while improving service coverage.Citation33,Citation34 These examples stress that how public health spending is channeled can be just as important to making progress toward UHC as the absolute levels of spending.

Similar to overall health financing for UHC, COVID-19’s impact on financing for UHC will take place through a number of channels. These channels include the macro-fiscal implications of economic contraction on the one side, as well as the opposing pressures to increase spending related to the COVID-19 response (including vaccination) and provide social and financial protection to the growing number of unemployed and poor. Only by unpacking and analyzing these channels, can targeted policy responses be developed to mitigate and safeguard UHC-related indicators and outcomes.

Macro-fiscal Impact

COVID-19 is resulting in a global contraction of GDP in almost all countries. COVID-19 has already had a high human cost, and, with public health systems struggling to cope, these costs will continue to grow.Citation35 The policies put in place by governments to slow the transmission of COVID-19 and rollout COVID-19 vaccination have led, in many countries, to massive demand and supply shocks. This has resulted in significant trade disruptions, drops in commodity prices, and the tightening of financial conditions in many countries. These effects have already caused large increases in unemployment and underemployment rates and will continue to threaten the survival of many firms worldwide.Citation36

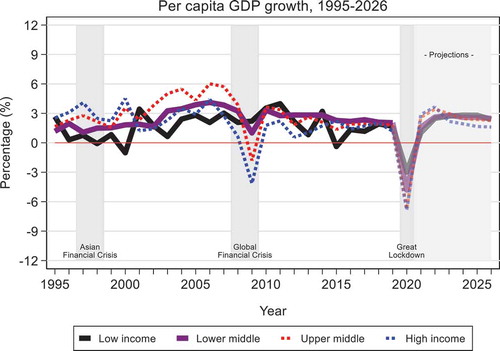

The full extent of the economic shock remains unclear, and even as countries begin to look toward the future, the impact on the global economy, poverty and inequality, is dire.Citation37 As of March 2021, the International Monetary Fund estimates cumulative per capita income losses between 2020 and 2022 as compared to pre-pandemic projections equivalent to 20% of 2019 per capita GDP in emerging and developing economies (excluding China) and 11% in advanced economies ().Citation35 Sharp declines in capital and remittance flows in low- and middle-income countries have occurred, and the latest projections indicate that declining consumption, investment, and trade are resulting in a global contraction. Globally, economies are expected to contract on average by −3.3% in per capita terms in 2020.Citation35,Citation38

While growth is expected to return in 2021, the 2020 setback and slower trajectory means that both poverty and inequality will increase dramatically, taking years to get back up to pre-COVID-19 levels. The ongoing crisis is expected to push between 119 and 124 million into extreme poverty (i.e., below 1.90 USD per capita/day) in 2020 alone, with an addition 24 million to 39 million more people in 2021.Citation39 Historically, extreme poverty was declining at the global level at a pace of −1% to −0.5% per year more recently, but as a result of COVID-19, the global extreme poverty rate is projected to increase from 8.2% in 2019 to somewhere between 9.1% and 9.4% in 2020, representing the first increase in global extreme poverty since 1998, effectively erasing progress made since 2017. Poverty forecasts presented in the October 2020 Poverty and Shared Prosperity Report suggest that the effects of the current crisis will almost certainly be felt in most countries through 2030.Citation37 The number of people living under the international poverty lines for lower and upper middle-income countries—$3.20/day and 5.50 USD/day in 2011 PPP, respectively—is also projected to increase significantly, signaling that social and economic impacts will be widely felt. Approximately 60% of the projected new poor will be in South Asia, and more than a third in Sub-Saharan Africa.Citation39 There is no question that this increase in poverty rates will impact utilization of services, while also exposing more people to catastrophic health expenditure.

These economic dynamics will have a cascade effect on already strained fiscal envelopes. Government revenues have already fallen as a consequence of the pandemic because of declining economic activity, and they may take longer to bounce back once economic recovery begins.Citation39 As fiscal space was already limited in many countries entering this crisis, there is a danger that policy responses to the crisis will either be insufficient or will worsen the macroeconomic framework in the medium term.

Globally, general government revenues represent about 30.6% of GDP on average, and tax revenues account for 18.1% of GDP. The contraction in economic activity and in trade resulting from the COVID-19 crisis brought government revenues down by 0.7 percentage points to 29.9% of GDP on average. The resulting decline in government revenues will be steeper for lower and upper middle-income countries (−1.2 and −1.4 percentage points, respectively). During an economic contraction, declining revenues in percentage of GDP translate into even steeper declines of revenues in per capita terms ().Citation40

Table 1. Projected impact on general government and tax revenues as share of GDP, 2017–2020

Despite declining general government revenues, government expenditures have risen as a share of GDP across most countries in 2020 in order to fund the health sector response, but also to protect people, jobs, and businesses during the recession, leading to a massive increase in deficits mostly financed by increased borrowing and quantitative easing monetary policies. In 2020, emerging market and developing economies are projected to have taken on additional 9 percentage points of debt in GDP terms, adding to already historically high levels coming into the crisis (176% of GDP in 2019 in these countries).Citation39 Part of this increase in government spending has been to finance the immediate response to the pandemic as well as to increase spending on social protection programs and to finance other government efforts designed to stimulate the economy in order to mitigate the adverse economic effects of the lockdown ().Citation38 However, we know that this pressure will not subside, with additional spending demands associated with COVID-19 vaccination.

Table 2. Projected impact on general government expenditures as share of GDP, 2017–2020

As with other crises, the interplay between declining economic activity and countercyclical fiscal and monetary policies will eventually determine levels of government spending across countries. Higher government spending as share of GDP could still imply a lower level of per capita government spending if the numerator does not rise enough to offset the decline in the denominator, or if debt relief measures are not implemented.Citation41

Health Spending Impact

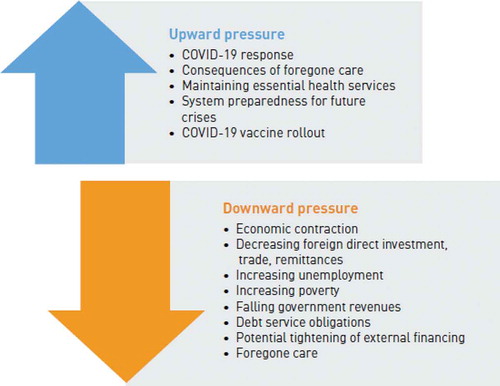

Overall macro-fiscal dynamics will have a clear impact on the level and composition of health spending. Added to this are the consequences of demand for health services as a result of the pandemic. underscores the various dynamics, which can be opposing in nature, that will ultimately determine health spending in the short- to medium-term.

In the past, public spending on health has tended to be procyclical across countries. If public spending on health responds to the current economic shock the same way it has in previous years, per capita public spending on health will slow down compared to pre-pandemic trends after an initial emergency spending response to COVID-19. The possible decline will be a result of the economic contractions that are projected to occur across most countries, even after controlling for changes in the government spending share of GDP and accounting for debt servicing’s share of government spending.Citation5,Citation42

Even if governments protect health’s share of the budget by keeping it the same as pre-crisis levels, government health spending per capita rises in 2020 and then falls in 2021 and again in 2022 for all country groups, mirroring the fall in general government expenditure per capita. Per capita spending is not expected to reach 2020 levels until 2024 in LICs and not until 2025 in all other income categories (these ‘health-protected’ scenarios are summarized in ).

Table 3. Status quo-based and health-protected projected scenarios for per capita public spending on health, 2009–2021

Low- and middle-income countries are highly dependent on household out-of-pocket financing for health.Citation43 Despite being an inefficient and inequitable way to finance health, and inimical for making equitable progress toward UHC, these out-of-pocket resources can and do represent a significant share of overall resources for health in many countries and are required for service use. Given the nature and magnitude of the income contraction expected due to the pandemic, levels of out-of-pocket spending will likely go down. Analysis of out-of-pocket spending on health in Europe during the 2009 financial crisis shows this trend, with those countries hit hardest by the crisis experiencing the largest reductions in out-of-pocket spending.Citation42 In the COVID-19 context, on the one hand, this effect will likely be aggravated by fear- and lockdown-related declining utilization trends which are being observed across many countries. On the other hand, increasing rates of self-medication and higher co-payments may have the opposite effect: leading to higher out-of-pocket spending. Declining out-of-pocket, declining consumption, and declining utilization will likely cause commonly used financial protection metrics—e.g., out-of-pocket shares of income/consumption—to improve, even though these improvements will be deceptive as they would be caused by forgone care rather than improvements in effective coverage. We also know that this forgone care is likely to hit the poor by much harder than other portions of society; exacerbating preexisting inequities in effective coverage.Citation44 These potential decreases may have implications for public expenditure on health as a means to compensate the lost revenues for private providers.Citation40

Coverage Impact

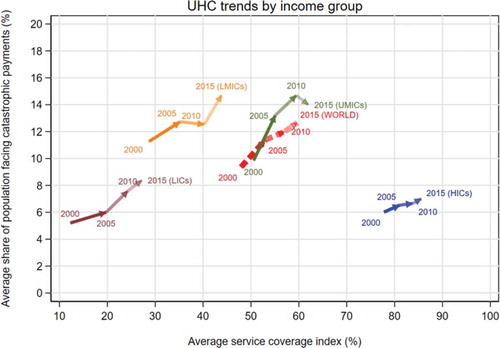

Progress toward UHC pre-COVID-19 has been notable, yet uneven in recent years. As part of the SDG monitoring framework, two indicators are used to measure UHC: service coverage and financial protection (for more details see 2019 Global Monitoring Report).Citation45 As highlighted in ,Citation45 between 2000 and 2015, service coverage was on an increasing trajectory, while financial protection worsened on average. The improvement in service coverage has been particularly marked for low-income countries, and the deterioration of financial protection steeper for middle-income countries. This financial protection trend can be attributed to the finding that as countries moved from lower to upper middle income, demand for services increased but the degree of financial support coming from prepaid, pooled resources remained broadly the same. It is only when countries moved from upper middle to high-income category that both service coverage and financial protection improved. These broad patterns are averages for the countries concerned; there is variation around the trend.

Service Use

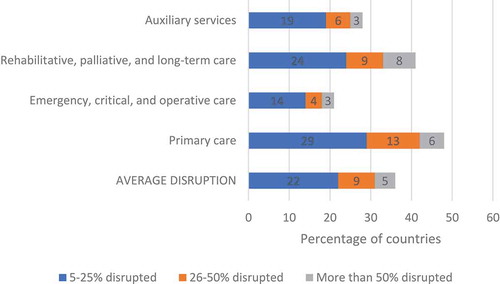

The large demand for COVID-19-related services that materialized in 2020, as well as the rollout of COVID-19 vaccination, has been counter-balanced by a reduction in the use of many other essential health services.Citation25,Citation46 This raises serious concerns from a UHC perspective, as one of its objectives is utilization of health services relative to need. WHO’s surveys to track the disruption to essential services in the context of COVID-19 have shown that between May and July 2020, 90% of the 105 sampled countries, representing all income levels and regions, reported disruptions in non-COVID-19 essential services, with this number increasing to 94% of 135 countries between January and March 2021.Citation25,Citation46 As shown in , there has been a prolonged disruption to all types of health services, although to varying degrees. The largest persistent disruptions are in primary care and rehabilitative, palliative and long-term care, with 48% and 41% of countries reporting some form of disruption, respectively. Added to this is the direct impact of COVID-19 on the health workforce, which contributes to additional supply constraints.Citation47 These supply shifts were matched with demand changes that led patients to forgo care, including due to a perceived lack of physical and financial access. The rates of forgone care and unmet need for health services were negatively correlated with income level, in that the poor had higher rates of unmet need.Citation48

Figure 4. Average percentage of disruptions across integrated service delivery channels, January–March 2021 (n = 112 countries)

While there has been some progress in getting services back online after the initial declines in 2020, disruptions persist. These disruptions impact service use and access across a range of conditions as well. As demonstrated by a December 2020 survey of service use in Kenya, with service disruption reported across almost all essential health services as compared to the 2019. Specifically, declines were reported care for sick children (49%), outpatient department with undifferentiated symptoms (46%), antenatal care (40%), and postnatal care (38%).Citation49 Interestingly, the only service that reported increase utilization was mental health care (23%), a trend that is likely to emerge given the nature of the pandemic response.Citation50,Citation51

From these statistics, it is clear that COVID-19 does not only have implications for health spending but also on how, and even whether, people access care. These have immediate consequences for governments seeking to get services back online for their populations, rollout COVID-19 vaccination, while also looking toward UHC-related objectives and ideals. The inherent resource constraints presented by the combined economic crisis and the spending pressures associated with COVID-19 vaccination means that prioritization and targeting will be necessary to make sure progress toward UHC is not derailed.

Financial Protection

As highlighted in , pre-COVID-19 trends were showing progress across all regions and income groups on service coverage, but not on financial protection. While low-income countries and high-income countries have similar degrees of financial protection, they differ substantially in terms of population coverage of essential health services. Low levels of financial hardship in low-income countries are a consequence of higher forgone care, not a sign of better financial protection.Citation48 Following the same argument, the projected decrease in out-of-pocket payment on the backdrop of the COVID-19 induced income contraction will reflect an increase in delayed and forgone care more than an improvement in financial protection.Citation43 As seen in previous crises, in those countries where health insurance coverage is tied to employment, uninsured rates will increase.Citation5,Citation52

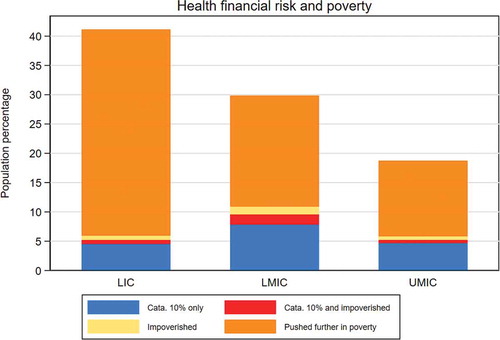

The poor face sizable financial hardships and are often pushed further below the poverty line as a result of having to pay for services out-of-pocket.Citation48 While the share of the world population pushed into extreme poverty as a result of health expenditures decreased between 2000 and 2015, the relative share of the impoverished population due to out-of-pocket among the global poor increased from about 7% in 2000 to 12% in 2015 (). Moreover, an important part of the population facing financial risk due to out-of-pocket are the poor who need to pay for health services and who are therefore pushed further below the poverty line because of health out-of-pocket. As discussed, given the poverty impact of COVID-19 and the related economic crisis, these trends will only be exacerbated in the coming years. below shows the relative importance of the different population categories facing financial hardship.

Table 4. Impoverishment due to out-of-pocket and extreme poverty (at $1.90)

Policy Responses Focusing on Equity and Redistribution

As laid out in the previous section, all countries are facing immediate and longer-term challenges with respect to health financing arrangements that can support continued progress toward UHC as a means to protect and promote the health and well-being of all people. Crisis sheds a critical light on system failures, and with that light comes the opportunity for systemic reforms. In this way, coping with the revenue and expenditure shocks that COVID-19 presents for the health sector requires adjustments beyond the preexisting health financing policies and strategies. The principles that guide health financing in the pre-COVID-19 era, as well as the lessons from previous health and financial crises, remain relevant.Citation26,Citation42 However, targeted policy intervention will be needed to address the specificities that are presented by COVID-19 and to reorient systems to support and protect the most vulnerable of society well into the future.

This section discusses mitigation and reform measures that the health sector can engage in to ensure financing for UHC is not derailed in the coming years. These interventions are organized first by those that involve engagement beyond the health sector, and second by those changes that can be made within the purview of health authorities.

Beyond the Health Sector

COVID-19 has exacerbated needs and inequities between those in higher-risk groups and the rest of society, which places even greater burdens on health financing systems to cope. This section lays out the specific policy implications of COVID-19 for health financing for UHC that can help to prioritize and buffer against shocks. These responses can also help to reorient health systems to ensure Common Goods for Health are prioritized, and the equity dimension of UHC comes to the forefront of policies to protect the most vulnerable of society.

The clear macro-fiscal impact of COVID-19 means that health authorities will need to work hand-in-hand with finance authorities to support general revenue allocation efforts and to ensure priority for health within the overall budgets. Even as countries emerge from the immediate crisis and GDP begins to rebound,Citation35 government revenues are expected to lag in terms of their response. The pressure to allocate available funds for the COVID-19 vaccination response is also enormous, as both a health and economic policy response. Therefore, as this transition process happens, finance authorities will be pursuing various options to protect overall government spending, including that for health; however, it will also be important to monitor potential displacement effects on other aspects of health financing.

As a way to protect health, as well as increase overall government revenues, the health sector can help to promote fiscal instruments by emphasizing the potential role that health taxes (e.g. tobacco, alcohol and sugary-sweetened beverage taxes) can play. Revenues from these taxes can be relatively marginal in relation to other sources,Citation53 however they have intrinsic value by promoting healthy behavior and potentially reducing the future rate of growth on health spending through health effects.Citation19 The health sector can contribute to additional fiscal measures with analysis and dialog around lowering fuel subsidies or introducing carbon taxation given the links between the environment and health.Citation54,Citation55

There is a role for the health sector to engage in budget prioritization discussions in relation to the immediate needs presented by COVID-19, but also in discussions around possible debt relief and other economic assistance measures. This includes health investment role in fiscal stimulus packages. Health spending should not be viewed purely as social spending, but rather as a means to improve productivity and economic activity.Citation56 This engagement will be particularly important given the reliance on emergency spending measures, particularly related to the COVID-19 vaccination rollout, which may not be incorporated into many annual budgets to date. Debt relief measures can also consider health, as demonstrated by the Heavily Indebted Poor Countries debt relief initiative in the 1990s, where social sector spending, including for health and education, were prioritized as part of the relief provisions.Citation57 Importantly, these provisions took into account both the level and efficiency of public spending for health as a means to improve access to quality health services. Macro-fiscal constraints will necessitate reexamining spending priorities across public sectors, including defunding particularly ineffective programs. The health sector can also be part of discussions around conditional cash transfers for low-income households. These transfers have been shown to alleviate poverty, while also reducing financial barriers to seeking care and improving human capital.Citation58

All of these measures require careful monitoring to ensure that allocations and spending priorities are ultimately implemented. Disaggregated monitoring is needed to ensure targeting measures, both in relation to income- and health-related risks, are put into place. This requires investments in information systems that can track expenditures, as well as the services and beneficiaries that they are linked to.

Within the Health Sector

As shown in previous crises, health financing policy will need to focus on ensuring affordable access to health services for poor and vulnerable populations, while also putting into place critical systems to manage COVID-19 and prepare for future shocks.Citation5,Citation56 These targeted efforts were already needed as part of policies to progress toward UHC; however, they are all the more critical given increased poverty and unemployment.

First, as Wagstaff (2010) and Yazbeck et al. (2020) stress, the link between contribution through employment-based taxation and entitlement to coverage should be softened, if not eliminated in many countries. The current economic crisis has triggered large-scale unemployment, which only exacerbates the problems with linking entitlement to employment.Citation52,Citation59 As unemployment increases, the revenues from employment-based contributions will decrease just as needs are expanding due to economic and health vulnerabilities. Linking entitlement to employment has important equity implications that can leave the informal sector and lower-income groups without effective access to services. Previous crises have triggered reforms to increase the role of general revenue relative to employment-based contributions as a means to expand coverage, especially for the poor, which can help soften the contribution-entitlement linkage.Citation42 Countries across Eastern Europe, Indonesia, Turkey and Thailand all expanded coverage for previously uncovered populations in the wake of deep financial crisis.Citation60 Shifting labor market dynamics, increasing informality, and the changing nature of work due to digital technologies had already hastened the need for this health financing policy shift.Citation56,Citation61 There is a need to ensure continuity of coverage and related health care as workers move in and out of formal employment.Citation62–64 Impoverishment and unemployment will make it difficult to administratively and financially manage schemes that do not do so, given the scale of changes in economic status that are ongoing as a result of the pandemic. This policy shift requires greater reliance on general tax revenues, increased prioritization for health within the government budget, and political commitment to UHC.

Second, due to economic constraints there will be a need to protect or prioritize certain services for certain populations within the health sector. For example, as Argentina emerged from deep financial crisis in 2001, Plan Nacer (which later became Programa Sumar) was established to expand and ensure coverage to maternal and infant services regardless of insurance or employment status, while providing performance-based incentives at both the provincial and provider levels.Citation65,Citation66 This program laid the groundwork to expand coverage for other services for those without formal insurance. Ensuring that the increasing number of people living below the poverty line are able to obtain the health services they need is critical, both as an immediate response to COVID-19 but also to safeguard progress toward UHC. During the 2009 financial crisis in Europe, concrete policy responses to prioritize and protect specific groups that were at higher risk of unmet need and financial hardship included moving toward general tax revenue funding for the health sector and away from employment-based contributions, lowering contribution rates for pensioners and the unemployed, abolishing tax subsidies that favored the rich, expanding entitlements to protect the poor, and lowering user charges on select services.Citation42 As with these previous crises, appropriate targeting is required, along with the capacity to monitor who is benefitting from the targeting. Additionally, it is critical to ensure that government funds are flexibly allocated to facilities to compensate for any changes in revenues, or else there is a concern that service availability will decrease in the face of decreased user fee revenue.

Third, this prioritization process should also consider a rebalancing toward prioritized investments in common goods for health that serve as the foundation for both health security and UHC-related objectives. As demonstrated by COVID-19, core public health policies, capacities, and systems were not in place to effectively prevent or respond in many countries. This will require a whole-of-government approach that coordinates actions between the health and other sectors and is at the center of the “Building Back Better” agenda in the wake of COVID-19.Citation8,Citation67–69 In most cases, common goods for health are relatively affordable, and therefore can be financed through incremental public financing.Citation70 However, external assistance will need to play an important role in low-income, fragile settings to buttress domestic financing efforts.Citation71

Finally, improving value for money and efficiency is even more pressing in the face of economic and health crisis, as well as the incredible pressure that COVID-19 vaccination will place on systems.Citation40 Inefficiencies abound in health and seizing the opportunity to be more efficient during the crisis can have long-lasting benefits.Citation72 The sources of these inefficiencies are well established,Citation72 and some countries have already taken efficiency-enhancing steps during the crisis, including increasing the use of telemedicine and the digital economy. Reducing fragmentation of fund flows, parallel administrative arrangements and duplicative functions across the entire sector are important reform areas, particularly as vaccination is expanded.Citation73 Realizing some of the longer-term efficiency goals will require targeted investments. For example, procuring and delivering the COVID-19 vaccine requires bolstering and strengthening vaccine supply chains globally, along with the services and health workforce to ultimately deliver the vaccine to individuals. This, along with overall efforts to improve preparedness and response capacities, should be embedded within overall health and public systems without creating additional fragmentation across the system. Implementing these policies will require adjustments to public financial management arrangements in many countries that enable flexibility while maintaining strong accountability mechanisms.Citation74 Intergovernmental fiscal transfer arrangements can also enable the rapid deployment of resources.

Conclusions

As Wagstaff noted in 2013, the UHC movement is fundamentally about ensuring everyone is able to get the care they need without facing financial hardship.Citation75 The emphasis on equity, financial protection, and quality was not new in 2013, nor is it new in 2021. However, the combined economic and health shocks are novel and are touching every country and person in the world to some extent. Given the dual nature of this crisis, the impact on health spending and coverage indicators is undeniable. However, as has been the case with UHC-related indicators historically,Citation76 the impact of these shocks is not unidirectional. This paper has sought to take a step back to consider the financing channels through which these shocks will impact UHC. Facing these challenges head on will not happen without deliberate and targeted policy interventions. Without these actions, there is a real and present danger that financial protection will continue to erode, unmet need will increase, and equity in service use and ultimately health outcomes will degrade. Otherwise said, COVID-19 requires countries to put in place mechanisms and policies that will control damage to UHC objectives while working to stay on course toward progress. This will involve prioritizing the poor, vulnerable and marginalized of societies to ensure there is equitable access to health services. COVID-19 has not changed this fact, but it has deepened it, brought out particular weaknesses, and hastened the need for action. As these policies are put in place, as Wagstaff and Neelsen (2020) stress,Citation76 both service coverage and financial protection will have to be analyzed carefully to ensure the dual objectives are on track.

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

References

- International Labour Organization. COVID-19 crisis and the informal economy. Geneva, Switzerland: International Labour Organization; 2020 May.

- World Health Organization Health Financing Team. Priorities for the Health Financing Response to COVID-19. P4H Social Protection Network. [accessed 2020 Nov 7] https://p4h.world/en/who-priorities-health-financing-response-covid19.

- Soucat A, Colombo F, Zhao F Beyond COVID-19 (coronavirus): what will be the new normal for health systems and universal health coverage? World Bank. [accessed 2020 Nov 7]. Investing in Health. https://blogs.worldbank.org/health/beyond-covid-19-coronavirus-what-will-be-new-normal-health-systems-and-universal-health.

- World Health Organization. The world health report - health systems financing: the path to universal coverage. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2010.

- Gottret P, Gupta V, Sparkes S, Tandon A, Moran V, Berman P. Protecting pro-poor health services during financial crises: lessons from experience. In: Chernichovsky D, Hanson K, editors. Innovations in health system finance in developing and transitional economies. Vol. 21. Bingley, United Kingdom: Emerald Group Publishing Limited; 2009. p. 1–13.

- Kutzin J, Witter S, Jowett M, Bayarsaikhan D. Developing a national health financing strategy: a reference guide. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2017.

- Kutzin J. A descriptive framework for country-level analysis of health care financing arrangements. Health Policy (New York). 2001;56(3):171–204. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S0168-8510(00)00149-4.

- United Nations. COVID-19 and universal health coverage. New York (NY): United Nations; 2020.

- Kruk ME, Ataguba JE, Akweongo P. The universal health coverage ambition faces a critical test. Lancet. 2020;396(10258):1130–31. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31795-5.

- UHC2030 Core Team. Living with COVID-19: time to get our act together on health emergencies and UHC. Geneva, Switzerland: UHC2030; 2020 [accessed 2020 Nov 7]. https://www.uhc2030.org/fileadmin/uploads/uhc2030/Documents/Key_Issues/Health_emergencies_and_UHC/UHC2030_discussion_paper_on_health_emergencies_and_UHC_-_May_2020.pdf.

- Kwon S. COVID-19: lessons from South Korea. Health Systems Global; 2020 [accessed 2020 Nov 7]. https://healthsystemsglobal.org/news/covid-19-lessons-from-south-korea/.

- Gharib M Universal health care supports Thailand’s coronavirus strategy. Asia: National Public Radio; 2020. Washington (DC): National Public Radio.

- Armocida B, Formenti B, Palestra F, Ussai S, Missoni E. COVID-19: universal health coverage now more than ever. J Glob Health. 2020;10(1). doi:https://doi.org/10.7189/jogh.10.010350.

- Lal A, Erondu NA, Heymann DL, Gitahi G, Yates R. Fragmented health systems in COVID-19: rectifying the misalignment between global health security and universal health coverage. Lancet. 2020;397(10268).

- Kutzin J, Sparkes SP. Health systems strengthening, universal health coverage, health security and resilience. Bull World Health Organ. 2015;94(2).

- United Nations General Assembly. Resolution adopted by the general assembly on 10 October 2019: political declaration of the high-level meeting on universal health coverage. A/RES/74/2. New York (NY): United Nations; 2019.

- Kutzin J, Sparkes S, Soucat A, et al. Priorities for the health financing response to COVID-19. 2021: P4H. 2020.

- World Health Organization. Financing common goods for health. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2021.

- Yazbeck AS, Soucat A. When both markets and governments fail health. Health Syst Reform. 2019;5(4):268–79. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/23288604.2019.1660756.

- Soucat A. Financing common goods for health: fundamental for health, the foundation for UHC. Health Syst Reform. 2019;5(4):263–67. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/23288604.2019.1671125.

- World Health Organization. Primary health care on the road to universal health coverage: 2019 monitoring report. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2019.

- Shadmi E, Chen Y, Dourado I, Faran-Perach I, Furler J, Hangoma P, Hanvoravongchai P, Obando C, Petrosyan V, Rao KD, et al. Health equity and COVID-19: global perspectives. Int J Equity Health. 2020;19(1):1–16. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-020-01218-z.

- Wagstaff A, Bredenkamp C, Buisman LR. Progress on global health goals: are the poor being left behind? World Bank Res Obs. 2014;29(2):137–62. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/wbro/lku008.

- Gwatkin DR. Trends in health inequalities in developing countries. Lancet Global Health. 2017;5(4):e371–e372. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(17)30080-3.

- World Health Organization. Pulse survey on continuity of essential health services during the COVID-19 pandemic: interim report, 27 August 2020. World Health Organization; 2020.

- Kutzin J. Anything goes on the path to universal health coverage? No. Bull World Health Organ. 2012;90(11):867–68. doi:https://doi.org/10.2471/BLT.12.113654.

- Barroy H, Vaughan K, Tapsoba Y, Dale E, Van de Maele N. Towards universal health coverage: thinking public. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2017.

- World Health Organization. Global spending on health: a world in transition. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2019.

- Xu K, Soucat A, Kutzin J, Brindley C, Vande Maele N, Touré H, Garcia MA, Li D, Barroy H, Flores G, et al. Public spending on health: a closer look at global trends. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2018.

- World Health Organization. Global health expenditure database. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2020.

- Fang H, Eggleston K, Hanson K, Wu M. Enhancing financial protection under China’s social health insurance to achieve universal health coverage. BMJ. 2019;365:l2378. doi:https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.l2378.

- Xu J, Jian W, Zhu K, Kwon S, Fang H. Reforming public hospital financing in China: progress and challenges. BMJ. 2019;365:l4015. doi:https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.l4015.

- Tangcharoensathien V, Pitayarangsarit S, Patcharanarumol W, Prakongsai P, Sumalee H, Tosanguan J, Mills A. Promoting universal financial protection: how the Thai universal coverage scheme was designed to ensure equity. Health Res Policy Syst. 2013;11:25. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/1478-4505-11-25.

- Tangcharoensathien V, Patcharanarumol W, Kulthanmanusorn A, Saengruang N, Kosiyaporn H. The political economy of UHC reform in Thailand: lessons for low- and middle-income countries. Health Syst Reform. 2019;5(3):195–208. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/23288604.2019.1630595.

- International Monetary Fund. World economic outlook: managing divergent recoveries. Washington (DC): International Monetary Fund; 2021 March.

- Loayza NV, Pennings S. Macroeconomic policy in the time of COVID-19: a primer for developing countries. World Bank; 2020.

- World Bank. Poverty and shared prosperity 2020: reversal of fortunes. Washington (DC): World Bank Group; 2020 October.

- International Monetary Fund. World economic outlook: a long and difficult ascent. Washington (DC): International Monetary Fund; 2020 Oct.

- World Bank. World economic prospects. Washington (DC): World Bank; 2021 January.

- Kurowski C, Evans D, Tandon A, Eozenou PH, Schmidt M, Irwin A, Salcedo Cain J, Pambudi ES, Postolovska I. From double shock to double recovery–implications and options for health financing in the time of COVID-19. Washington (DC): World Bank; 2021.

- International Monetary Fund. G-20 Surveillance Note: COVID-19—Impact and Policy Considerations. Washington, DC: G-20 Finance Ministers and Central Bank Governors’ Meetings; 15 April 2020.

- Thomson S, Figueras J, Evetovits T, Jowett M, Mladovsky P, Maresso A, Cylus J, Karanikolos M, Kluge H. Economic crisis, health systems and health in Europe. New York (NY): World Health Organization; 2015.

- World Health Organization. Global health expenditure report 2020: weathering the storm. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2020.

- Wagstaff A. Poverty and health sector inequalities. Bull World Health Organ. 2002;80:97–105.

- World Health Organization and World Bank. Tracking universal health coverage: first global monitoring report. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2015.

- World Health Organization. Second round of the national pulse survey on continuity of essential health services during the COVID-19 pandemic: January-March 2021. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2021.

- Nagesh S, Chakraborty S. Saving the frontline health workforce amidst the COVID-19 crisis: challenges and recommendations. J Glob Health. 2020;10(1). doi:https://doi.org/10.7189/jogh.10.010345.

- Thomson S, Cylus J, Evetovits T. Can people afford to pay for health care? New evidence on financial protection in Europe. Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe; 2019.

- Kenya Ministry of Health. Readiness for COVID-19 response and continuity of essential health services in health facilities and communities. Nairobi: Kenya Ministry of Health; 2021 February.

- Holland KM, Jones C, Vivolo-Kantor AM, Idaikkadar N, Zwald M, Hoots B, Yard E, D’Inverno A, Swedo E, Chen MS, et al. Trends in US emergency department visits for mental health, overdose, and violence outcomes before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Psychiatry. 2021;78(4):372–79. doi:https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2020.4402.

- Amsalem D, Dixon LB, Neria Y. The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak and mental health: current risks and recommended actions. JAMA Psychiatry. 2021;78(1):9–10. doi:https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2020.1730.

- Yazbeck AS, Savedoff WD, Hsiao WC, Kutzin J, Soucat A, Tandon A, Wagstaff A, Chi-Man Yip W. The case against labor-tax-financed social health insurance for low-and low-middle-income countries: a summary of recent research into labor-tax financing of social health insurance in low-and low-middle-income countries. Health Aff. 2020;39(5):892–97. doi:https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2019.00874.

- World Health Organization. Earmarked tobacco taxes: lessons learnt from nine countries. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2016.

- Fuchs A, Marquez PV, Dutta S, Gonzalez Icaza F. Is tobacco taxation regressive? Evidence on public health, domestic resource mobilization, and equity improvements. Washington (DC): World Bank; 2019.

- Tandon A, Roubal T, McDonald L, Cowley P, Palu T, de Oliveira Cruz V, Eozenou P, Cain J, Teo HS, Schmidt M. Economic Impact of COVID-19: implications for health financing in asia and pacific. Washington (DC): World Bank Group; 2020.

- World Bank Group. High-performance health financing for universal health coverage: driving sustainable, inclusive growth in the 21st century. Washington (DC): World Bank; 2019.

- Gupta S, Clements B, Guin-Siu MT, Leruth L. Debt relief and public health spending in heavily indebted poor countries. Bull World Health Organ. 2002;80:151–57.

- Fernald LCH, Gertler PJ, Neufeld LM. Role of cash in conditional cash transfer programmes for child health, growth, and development: an analysis of Mexico’s Oportunidades. Lancet. 2008;371(9615):828–37. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60382-7.

- Wagstaff A. Social health insurance reexamined. Health Econ. 2010;19(5):503–17. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/hec.1492.

- Reich MR, Harris J, Ikegami N, Maeda A, Cashin C, Araujo EC, Takemi K, Evans TG. Moving towards universal health coverage: lessons from 11 country studies. Lancet. 2016;387(10020):811–16. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60002-2.

- Djankov S, Saliola F. Changing nature of work: a world bank group flagship report. Washington (DC): World Bank; 2019.

- Vijayasingham L, Govender V, Witter S, Remme M. Employment based health financing does not support gender equity in universal health coverage. BMJ. 2020;371(m3384).

- Antón A, Trillo FH, Levy S. The end of informality in México?: fiscal reform for universal social insurance. Vol. 1300. Washington (DC): Inter-American Development Bank; 2012.

- Doubova SV, Borja-Aburto VH, Guerra-y-guerra G, Salgado-de-snyder VN, González-Block MÁ. Loss of job-related right to healthcare is associated with reduced quality and clinical outcomes of diabetic patients in Mexico. Int J Qual Health Care. 2018;30(4):283–90. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/intqhc/mzy012.

- Sabignoso M, Zanazzi L, Sparkes S, Mathauer I, Organization WH. Strengthening the purchasing function on through results-based financing in a federal setting: lessons from Argentina’s programa sumar. 2020.

- Celhay PA, Gertler PJ, Giovagnoli P, Vermeersch C. Long-run effects of temporary incentives on medical care productivity. Am Econ J Appl Econ. 2019;11:92–127.

- Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development. Building back better: a sustainable, resilient recovery after COVID-19 OECD policy responses to coronavirus (COVID-19). Vol. 2020. Paris: Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development; 2020.

- Sparkes SP, Kutzin J, Earle AJ. Financing common goods for health: a country agenda. Health Syst Reform. 2019;5:322–33. null-null. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/23288604.2019.1659126.

- Secretary - General of the United Nations. Indicators and a monitoring framework for the sustainable development goals. New York: United Nations; 2015.

- Gaudin S, Smith PC, Soucat A, Yazbeck AS. Common goods for health: economic rationale and tools for prioritization. Health Sys Reform. 2019;5(4):280–92. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/23288604.2019.1656028.

- Jowett M, Dale E, Griekspoor A, Kabaniha G, Mataria A, Bertone M, Witter. Health financing policy and implementation in fragile and conflict-affected settings. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2020.

- Yip W, Hafez R. Reforms for improving the efficiency of health systems: lessons from 10 country cases. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2015.

- Sparkes S, Duran A, Kutzin J. A system-wide approach to analysing efficiency across health programs. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2017.

- Rahim F, Allen R, Barroy H, Gores L, Kutzin J. COVID-19 funds in response to the pandemic. Washington (DC): International Monetary Fund; 2020 [accessed 2021 Jun 3]. https://blog-pfm.imf.org/pfmblog/2020/08/-covid-19-funds-in-response-to-the-pandemic-.html

- Wagstaff A. Universal health coverage: old wine in a new bottle? If so, is that so bad? In: World bank blogs. Vol. 2021. Washington (DC): World Bank; 2013.

- Wagstaff A, Neelsen S. A comprehensive assessment of universal health coverage in 111 countries: a retrospective observational study. Lancet Global Health. 2020;8(1):e39–e49. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(19)30463-2.